Abstract

A proportion of acute ischemic stroke (AIS) patients suffer from early neurological deterioration (END) within 24 hours following intravenous thrombolysis (IVT), which greatly increases the risk of poor prognosis of these patients. Therefore, we aimed to explore the predictors of early neurological deterioration of ischemic origin (ENDi) in AIS patients after IVT and develop a nomogram prediction model. This study collected 244 AIS patients with post-thrombolysis ENDi as the derivation cohort and 155 patients as the validation cohort. To establish a nomogram prediction model, risk factors were identified by multivariate logistic regression analysis. The results showed that neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio (NLR) (OR 2.616, 95% CI 1.640–4.175, P < 0.001), mean platelet volume (MPV) (OR 3.334, 95% CI 1.351–8.299, P = 0.009), body mass index (BMI) (OR 1.979, 95% CI 1.285–3.048, P = 0.002) and atrial fibrillation (AF) (OR 8.012, 95% CI 1.341–47.873, P = 0.023) were significantly associated with ENDi. The area under the curve of the prediction model constructed from the above four factors was 0.981 (95% CI 0.961–1.000) and the calibration curve was close to the ideal diagonal line. Therefore, this nomogram prediction model exhibited good discrimination and calibration power and might be a reliable and easy-to-use tool to predict post-thrombolysis ENDi in AIS patients.

Keywords: Acute ischemic stroke, early neurological deterioration, intravenous thrombolysis, nomogram, prediction model

Introduction

Ischemic stroke, as the predominant subtype of stroke, has become the first cause of death in China.1 –3 At present, intravenous thrombolysis (IVT) is a preferred and effective treatment to restore blood flow recommended by the guidelines for patients with acute ischemic stroke (AIS). 4 Theoretically, functional outcomes of AIS patients tend to improve after IVT, but a part of patients still could not distinctively recover or even deteriorates, which is known as early neurological deterioration (END).5,6

Owing to the huge heterogeneity of definition criteria of END in previous studies, reported incidence of END also varied from 5% to 40%. 7 When END was defined as an increase in the National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) scores ≥4 within the first 24 hours after IVT, the reported incidence rates of END after IVT were 8.1–28.1%. 8 There are some straightforward causes may lead to END, such as symptomatic intracranial hemorrhage, malignant edema, early recurrent ischemic stroke, and poststroke seizure.9,10 In addition, a sizeable proportion of END cases are categorized as progressive stroke due to unclear causes.9,10 Previous study found that the incidence of END caused by symptomatic intracranial hemorrhage was 21.4%, early neurological deterioration of ischemic origin (ENDi) was more common than that of hemorrhagic origin. 11 The mechanisms of post-thrombolysis END are not completely clear. Both hemodynamic and bio-metabolic abnormalities can cause END.12,13

The clinical progress within the first 24 hours after IVT is difficult to be predicted. 6 Once END occurs, the disability rate and mortality rate of patients will significantly increase.14,15 Therefore, it is of great clinical significance to explore the markers to timely predict the occurrence of END in AIS patients after IVT. Reviews of the literature reveal that several factors such as hyperglycemia, baseline NIHSS and proximal arterial occlusion can predict END.8,16 But the predictive value of these factors remains unclear. Thus, this study aimed to explore the predictors of ENDi in AIS patients after IVT, develop and externally validate a nomogram prediction model designed to assist clinicians assess the risk of ENDi in AIS patients, thereby enabling early intervention.

Material and methods

Study population

This retrospective study recruited consecutive patients who were diagnosed with AIS and underwent IVT at the First Affiliated Hospital of Jinzhou Medical University from January 2018 to December 2020 as the derivation cohort, and collected 100 AIS patients who did not undergo IVT during the same period for comparison. In addition, this study recruited consecutive AIS patients who received IVT at the same hospital from January 2021 to January 2023 as the validation cohort. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the First Affiliated Hospital of Jinzhou Medical University and was conducted in accordance with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments. A waiver of informed consents from patients was approved due to the retrospective nature of this study.

The inclusion criteria for patients receiving IVT were as follows: (1) age ≥18 years; (2) diagnosed with AIS; (3) received IVT with alteplase. Patients who met any of the following exclusion criteria were excluded from the study: (1) hospitalization time ≤24 hours; (2) symptom onset noticed upon waking (wake-up stroke); (3) intracranial hemorrhage detected on cranial computerized tomography (CT) after IVT; (4) combined with other medical diseases including serious cardiac failure, renal failure, hepatic failure, systemic inflammatory disease, active infection, brain tumor; (5) received endovascular therapy following IVT; (6) incomplete data.

The inclusion criteria for patients who did not receive IVT included the following: (1) age ≥18 years; (2) diagnosed with AIS; (3) did not receive reperfusion therapy. Patients who met any of the following exclusion criteria were excluded from the study: (1) hospitalization time ≤24 hours; (2) intracranial hemorrhage detected on CT; (3) combined with other medical diseases including serious cardiac failure, renal failure, hepatic failure, systemic inflammatory disease, active infection, brain tumor; (4) incomplete data.

Treatment principles for all patients strictly followed the guidelines for the early management of patients with AIS from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association.17,18

Data collection

The following data of all patients were collected retrospectively: age, gender, height, weight, vascular risk factors [hypertension, diabetes mellitus (DM), atrial fibrillation (AF), hyperhomocysteinemia], history of smoking and drinking, laboratory tests [i.e., fasting blood glucose (FBG), neutrophil count, lymphocyte count, red blood cell count, mean corpuscular hemoglobin concentration (MCHC), platelet count, mean platelet volume (MPV), triglyceride (TG), total cholesterol (TC), low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C), high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C)]. Venous blood samples were collected at admission before IVT. The body mass index (BMI) was calculated as the weight (kilograms) divided by the height (meters) squared. The NIHSS scores at admission and 24 hours after IVT and modified Rankin Scale (mRS) scores at 3 months after onset were assessed by two experienced neurologists.

Definition of ENDi

ENDi was defined as an increase in NIHSS score ≥4 within the first 24 hours after IVT without parenchymal hemorrhage on follow-up imaging or another identified cause. 19

Statistical analysis

Statistical data analysis was performed with the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) software version 26.0 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) and R software version 4.2.3. Quantitative data were described as mean ± standard deviation or median (interquartile range, IQR). The Kolmogorov-Smirnov (K-S) test was used to assess the normality of data distributions. Differences between the two groups were compared by using Student’s t-test or Mann-Whitney U test. Qualitative data was described as frequency and percentage, and Chi-squared test or Fisher’s exact test were performed to detect differences between the two groups.

To establish the nomogram, variables with a P-value of <0.20 in univariate analysis were subsequently entered into a multivariable logistic regression analysis using the backward stepwise method. A two-tailed P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Internal cross-validation of this model was based on 1,000 bootstrap replicates. The model’s discriminatory ability was assessed using the receiver-operating characteristic (ROC) curve, area under the ROC curve (AUC) and concordance index (C-index). The calibration curve, Hosmer‑Lemeshow test and Brier score were used to evaluate the conformity of the model. Decision curve analysis (DCA) was used to assess the net benefit of the model for patients.

Results

Baseline characteristics

Derivation cohort

From January 2018 to December 2020, a total of 244 patients were finally included in the derivation cohort, the enrollment flow was depicted in Supplemental figure 1. Baseline characteristics of the subjects were presented in Table 1. The mean age was 60.16 ± 11.56 years and 181 subjects (74.2%) were male. The most common vascular risk factor of subjects in this cohort was DM (43.9%), followed by hypertension (42.2%). The median NIHSS score of subjects was 6 (IQR 5–8) at baseline and 6 (IQR 3–10) at 24 hours after IVT. There were 62 (25.4%) subjects experienced ENDi and these subjects were assigned to ENDi group while the other 182 (74.6%) subjects were assigned to non-ENDi group (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics and comparison between the derivation cohort and validation cohort.

| Derivation cohort(n = 244) | Validation cohort(n = 182) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 60.16 (11.56) | 62.02 (7.62) | 0.054 |

| Gender (men), n (%) | 181 (74.2) | 104 (67.1) | 0.127 |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 103 (42.2) | 80 (51.6) | 0.066 |

| DM, n (%) | 107 (43.9) | 82 (52.9) | 0.078 |

| AF, n (%) | 28 (11.5) | 17 (11.0) | 0.876 |

| Smoking, n (%) | 80 (32.8) | 53 (34.2) | 0.771 |

| Drinking, n (%) | 117 (48.0) | 64 (41.3) | 0.193 |

| Hyperhomocysteinemia, n (%) | 97 (39.8) | 67 (43.2) | 0.492 |

| Baseline NIHSS | 6 (5–8) | 6 (4–10) | 0.420 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 21.22 (20.25–22.77) | 21.30 (19.33–23.78) | 0.556 |

| Fasting blood glucose, mmol/L | 6.03 (5.25–7.46) | 6.60 (4.90–9.80) | 0.089 |

| Red blood cell count, /L | 4.48 (4.07–4.85) | 4.43 (4.12–4.85) | 0.860 |

| MCHC, g/L | 332.30 (325.73–338.30) | 320.30 (311.30–333.70) | <0.001 |

| Platelet count, /L | 214.15 (179.08–256.78) | 196.50 (169.30–243.80) | 0.034 |

| MPV, fl | 8.85 (8.20–9.81) | 8.63 (8.06–9.50) | 0.036 |

| Neutrophil count, /L | 5.63 (4.07–7.30) | 5.33 (3.78–7.02) | 0.204 |

| Lymphocyte count, /L | 1.21 (0.89–1.61) | 1.23 (0.87–1.65) | 0.687 |

| NLR | 4.61 (3.16–6.30) | 3.90 (2.81–6.46) | 0.133 |

| PLR | 174.72 (134.71–262.84) | 161.70 (122.63–231.08) | 0.058 |

| TC, mmol/L | 4.55 (3.86–5.38) | 4.80 (4.09–5.37) | 0.263 |

| TG, mmol/L | 1.26 (0.79–2.02) | 1.30 (0.78–2.08) | 0.703 |

| LDL-C, mmol/L | 2.78 (2.28–3.52) | 2.61 (2.14–3.20) | 0.011 |

| HDL-C, mmol/L | 1.05 (0.86–1.30) | 0.98 (0.82–1.17) | 0.037 |

DM: diabetes mellitus; AF: atrial fibrillation; NIHSS: National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale; BMI: body mass index; MCHC: mean corpuscular hemoglobin concentration; MPV: mean platelet volume; NLR: neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio; PLR: platelet to lymphocyte ratio; TG: triglyceride; TC: total cholesterol; LDL-C: low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; HDL-C: high-density lipoprotein cholesterol.

Validation cohort

A total of 155 patients were included in the validation cohort, the enrollment flow was depicted in Supplemental figure 1. The mean age was 64.70 ± 9.19 years and 90 subjects (58.1%) were male. The most common vascular risk factor of subjects in this cohort was hypertension (54.8%). The median NIHSS score of subjects was 6 (IQR 4–10) at baseline and 5 (IQR 2–10) at 24 hours after IVT. There were 26 (16.8%) subjects experienced ENDi (Table 1).

Comparison between patients undergoing IVT and those who did not undergo IVT

This study included 100 AIS patients who did not receive IVT during the same period for comparison. The mean age was 64.54 ± 18.89 years and 55 subjects (55.0%) were male. The median NIHSS score of subjects were both 5 (IQR 3–8) at baseline and at 24 hours after IVT. There were 14 (14.0%) subjects experienced ENDi. The baseline characteristics and comparison between patients with ENDi and without ENDi of the subjects who did not undergo IVT were presented in Supplemental table 1. In the patients with ENDi, there was no significant difference in baseline characteristics between patients undergoing IVT and those who did not undergo IVT (P > 0.05) (Supplemental table 2).

Comparison between the derivation cohort and validation cohort

There were statistically significant differences between the two cohorts regarding the levels of MCHC (332.30 [IQR 325.73–338.30] vs. 320.30 [IQR 311.30–333.70] g/L, P < 0.001), platelet count (214.15 [IQR 179.08–256.78] vs. 196.50 [IQR 169.30–243.80]× /L, P = 0.034), MPV (8.85 [IQR 8.20–9.81] vs. 8.63 [IQR 8.06–9.50] fl, P = 0.036), LDL-C (2.78 [IQR 2.28–3.52] vs. 2.61 [IQR 2.14–3.20] mmol/L, P = 0.011) and HDL-C (1.05 [IQR 0.86–1.30] vs. 0.98 [IQR 0.82–1.17] mmol/L, P = 0.037). The most general baseline characteristics and vascular risk factors were not statistically significantly different (P > 0.05) (Table 1).

Independent risk factors for ENDi

Univariable analysis

The median NIHSS score at 24 hours after IVT of the subjects in ENDi group was 13 (IQR 10–16), which was significantly higher than that in non-ENDi group (5, IQR 2–8). Subjects with ENDi were older than those without ENDi (63.82 ± 11.45 vs. 58.91 ± 11.36 years, P = 0.004). The proportion of hyperhomocysteinemia (53.2% vs. 35.2%, P = 0.012) was remarkably higher in ENDi group than that in non-ENDi group, whereas the proportions of DM (32.3% vs. 47.8%, P = 0.033) and drinking (30.6% vs. 53.8%, P = 0.002) were lower. Compared to subjects without ENDi, subjects with ENDi had higher levels of BMI (24.77 [IQR 22.29–26.35] vs. 20.72 [IQR 20.17–21.80] kg/m2, P < 0.001), FBG (6.90 [IQR 5.45–9.14] vs. 5.82 [IQR 5.23–7.12] mmol/L, P = 0.012), MPV (10.10 [IQR 9.33–10.83] vs. 8.63 [IQR 8.12–9.22] fl, P < 0.001), neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio (NLR) (11.51 [IQR 7.91–13.63] vs. 3.91 [IQR 2.88–5.09], P < 0.001), platelet to lymphocyte ratio (PLR) (279.46 [IQR 219.34–321.84] vs. 156.86 [IQR 124.07–208.51], P < 0.001) and lower levels of lymphocyte counts (0.85 [IQR 0.59–1.11] vs. 1.35 [IQR 1.05–1.69] /L, P < 0.001), MCHC (329.40 ± 8.19 vs. 333.17 ± 9.83 g/L, P = 0.007). No significant differences were observed between the two groups with regard to other characteristics (P > 0.05) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Characteristics and comparison between the ENDi group and non-ENDi group in derivation cohort.

| Total(n = 244) | ENDi group(n = 62) | Non-ENDi group(n = 182) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 60.16 (11.56) | 63.82 (11.45) | 58.91 (11.36) | 0.004 |

| Gender (men), n (%) | 181 (74.20) | 43 (69.40) | 138 (75.80) | 0.315 |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 103 (42.20) | 30 (48.40) | 73 (40.10) | 0.254 |

| DM, n (%) | 107 (43.90) | 20 (32.30) | 87 (47.80) | 0.033 |

| AF, n (%) | 28 (11.50) | 11 (17.70) | 17 (9.30) | 0.073 |

| Smoking, n (%) | 80 (32.80) | 25 (40.30) | 55 (30.20) | 0.143 |

| Drinking, n (%) | 117 (48.00) | 19 (30.60) | 98 (53.80) | 0.002 |

| Hyperhomocysteinemia, n (%) | 97 (39.80) | 33 (53.20) | 64 (35.20) | 0.012 |

| Baseline NIHSS | 6 (5–8) | 6 (4–9) | 6 (5–8) | 0.746 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 21.22 (20.25–22.77) | 24.77 (22.29–26.35) | 20.72 (20.17–21.80) | <0.001 |

| Fasting blood glucose, mmol/L | 6.03 (5.25–7.46) | 6.90 (5.45–9.14) | 5.82 (5.23–7.12) | 0.012 |

| Red blood cell count /L | 4.48 (4.07–4.85) | 4.52 (3.84–4.88) | 4.47 (4.11–4.84) | 0.716 |

| MCHC, g/L | 332.21 (9.56) | 329.40 (8.19) | 333.17 (9.83) | 0.007 |

| Platelet count, /L | 214.15 (179.08–256.78) | 219.55 (179.78–265.65) | 212.95 (179.00–252.90) | 0.613 |

| MPV, fl | 8.85 (8.20–9.81) | 10.10 (9.33–10.83) | 8.63 (8.12–9.22) | <0.001 |

| Neutrophil count, /L | 5.63 (4.07–7.30) | 8.74 (6.78–10.52) | 4.99 (3.79–6.48) | <0.001 |

| Lymphocyte count, /L | 1.21 (0.89–1.61) | 0.85 (0.59–1.11) | 1.35 (1.05–1.69) | <0.001 |

| NLR | 4.61 (3.16–6.30) | 11.51 (7.91–13.63) | 3.91 (2.88–5.09) | <0.001 |

| PLR | 174.72 (134.71–262.84) | 279.46 (219.34–321.84) | 156.86 (124.07–208.51) | <0.001 |

| TC, mmol/L | 4.61 (1.19) | 4.66 (0.96) | 4.59 (1.26) | 0.687 |

| TG, mmol/L | 1.26 (0.79–2.02) | 1.29 (0.77–2.13) | 1.25 (0.79–1.97) | 0.889 |

| LDL-C, mmol/L | 2.78 (2.28–3.52) | 2.84 (2.15–3.43) | 2.76 (2.30–3.56) | 0.862 |

| HDL-C, mmol/L | 1.05 (0.86–1.30) | 1.05 (0.84–1.33) | 1.04 (0.87–1.29) | 0.857 |

ENDi: early neurological deterioration of ischemic origin; DM: diabetes mellitus; AF: atrial fibrillation; NIHSS: National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale; BMI: body mass index; MCHC: mean corpuscular hemoglobin concentration; MPV: mean platelet volume; NLR: neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio; PLR: platelet to lymphocyte ratio; TG: triglyceride; TC: total cholesterol; LDL-C: low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; HDL-C: high-density lipoprotein cholesterol.

Multivariable analysis

After screening, age, AF, DM, drinking, smoking, hyperhomocysteinemia, BMI, FBG, NLR, PLR, MPV, MCHC were included in the multivariate logistic regression analysis. The results of the multivariable logistic regression analysis showed that NLR (OR 2.616, 95% CI 1.640–4.175, P < 0.001), MPV (OR 3.334, 95% CI 1.351–8.299, P = 0.009), BMI (OR 1.979, 95% CI 1.285–3.048, P = 0.002) and AF (OR 8.012, 95% CI 1.341–47.873, P = 0.023) were independently associated with ENDi in AIS patients in the derivation cohort (Table 3).

Table 3.

Multivariate logistic regression analysis on the association between influencing factors and ENDi.

| OR | 95%CI | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| NLR | 2.616 | 1.640–4.175 | <0.001 |

| MPV | 3.334 | 1.351–8.299 | 0.009 |

| BMI | 1.979 | 1.285–3.048 | 0.002 |

| AF | 8.012 | 1.341–47.873 | 0.023 |

ENDi: early neurological deterioration of ischemic origin; NLR: neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio; MPV: mean platelet volume; BMI: body mass index; AF: atrial fibrillation.

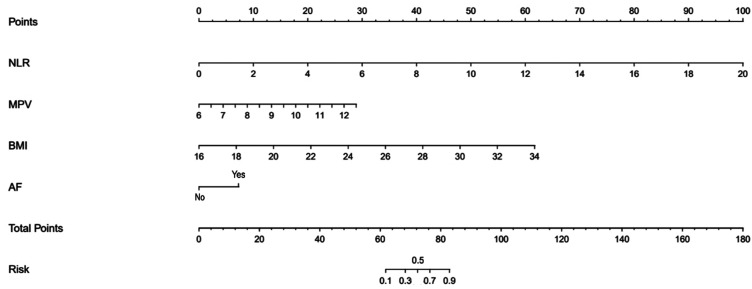

Construction of the nomogram

The nomogram was constructed based on the four factors mentioned above (Figure 1). The nomogram predicted ENDi of AIS patients by first identifying the position of each variable for each corresponding point on the nomogram axes. Second, add the scores for all variables to get the total score. The total score then estimated the ENDi risk of each patient. For example, the following results were obtained: NLR = 4.5, MPV = 10.5 fl, BMI = 22 kg/m2, with history of AF. Then, the corresponding risk for ENDi was 50%.

Figure 1.

Nomogram for the prediction of ENDi in the AIS patients treated with IVT.

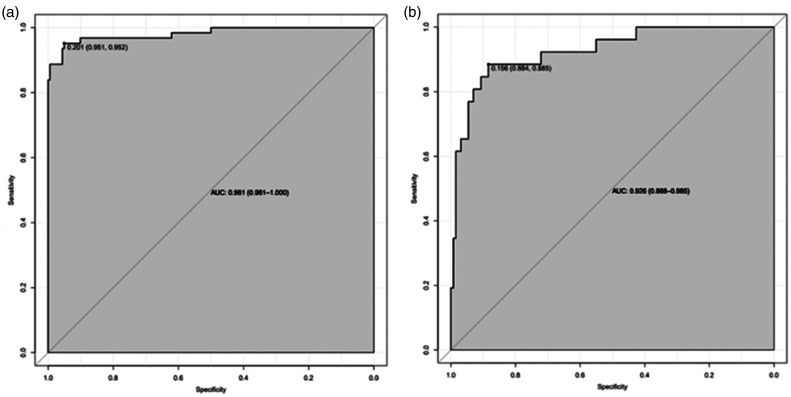

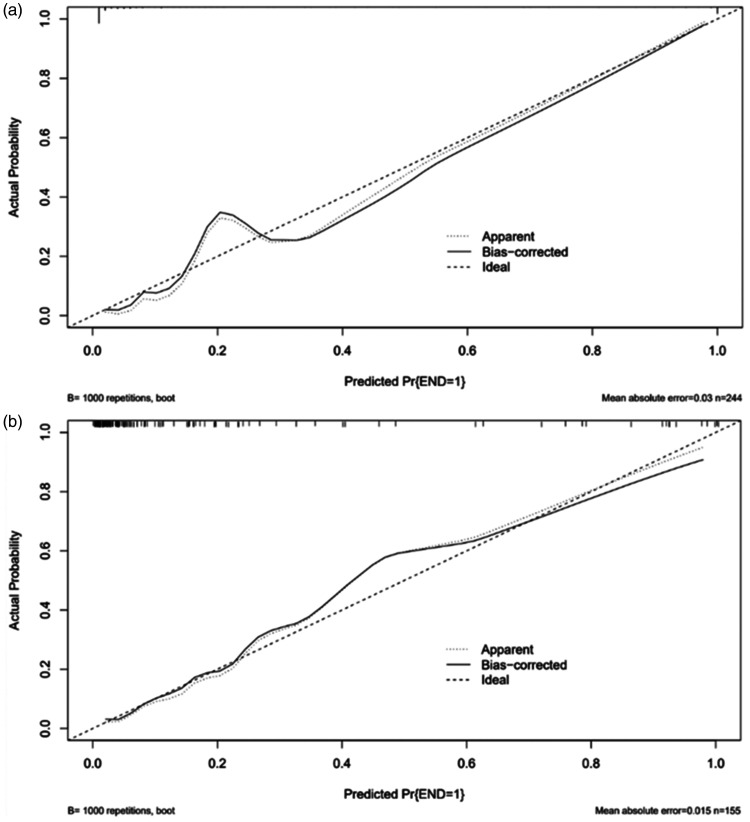

Predictive accuracy of the nomogram

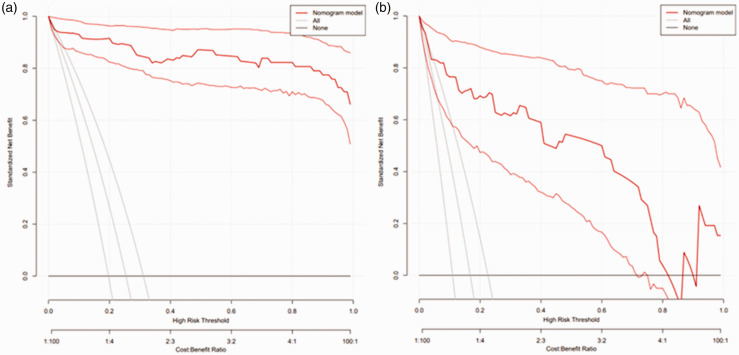

In the derivation cohort, the AUC was 0.981 (95% CI 0.961–1.000) (Figure 2(a)), and the calibration curve was close to the ideal diagonal line (Figure 3(a)). The Hosmer-Lemeshow test result was not statistically significant (χ2 = 9.7889, P = 0.2802) and the Brier score was 0.024, which indicated the good conformity of the model. Furthermore, DCA showed a significantly greater net benefit of the nomogram (Figure 4(a)). The internal cross-validation based on 1,000 bootstrap replicates showed a similar C-index (0.9815, 95% CI [0.9809–0.9821]).

Figure 2.

ROC curves. (a) Derivation cohort and (b) Validation cohort.

Figure 3.

Calibration curves of the nomogram model. (a) Derivation cohort and (b) Validation cohort.

Figure 4.

Decision curve analysis of the nomogram model. (a) Derivation cohort and (b) Validation cohort.

External validation of the model was performed on 155 patients who admitted to the same hospital at another time period. The AUC was 0.926 (95% CI 0.868–0.985) (Figure 2(b)), reflecting good accuracy of the nomogram. Meanwhile, the nomogram had good consistency. The calibration curve of the validation group was also close to the ideal diagonal line (Figure 3(b)). Results of the Hosmer-Lemeshow test (χ2 = 3.8481, P = 0.8706) and the Brier score (0.063) indicated a good fit for this model. Moreover, DCA also showed a significant net benefit of the nomogram in the validation cohort (Figure 4(b)).

Prognosis at three months after onset

The prognosis of the patients at 3 months after onset was evaluated by the mRS and the poor prognosis was defined as mRS scores > 2. In the derivation cohort, there were 63 (34.6%) patients had poor prognosis in the non-ENDi group and 42 (67.7%) patients in the ENDi group, the proportion of patients with poor prognosis was remarkably higher in ENDi group than that in non-ENDi group (P < 0.001).

In order to explore whether the above four factors were also associated with the poor prognosis of patients at 3 months after onset, logistic regression analysis was conducted. The results showed that NLR (OR 1.121, 95% CI 1.046–1.201, P = 0.001), MPV (OR 1.645, 95% CI 1.286–2.104, P < 0.001) and BMI (OR 1.342, 95% CI 1.186–1.519, P < 0.001) were associated with poor prognosis while AF (OR 0.708, 95% CI 0.312–1.604, P = 0.407) was not.

Discussion

The occurrence of END after IVT is still a serious problem that endangers the quality of life and prognosis of patients. In order to identify and prevent the occurrence of END as early as possible, it is important and urgent to explore predictors of END. 20 After statistical layers of screening, we found that NLR, MPV, BMI and AF were independent risk factors and predictors of ENDi in AIS patients after IVT. The nomogram prediction model was based on the above four factors and showed great discrimination and conformity for the prediction of ENDi in this population. In addition, we observed that patients with ENDi had a worse prognosis, and NLR, MPV and BMI were also associated with poor prognosis at 3 months after AIS.

Inflammatory response is a crucial pathological process after cerebral ischemia or reperfusion injury. 21 Neutrophils are important mediators of acute ischemic brain injury, produce pro-inflammatory cytokines and induce the expression of matrix metalloproteinase-9 (MMP-9), then result in blood-brain barrier destruction and further brain damage.22,23 In contrast, lymphocytes are thought to play a protective role in the inflammatory response of ischemic injury. 24 Relative lymphopenia reflects cortisol induced stress response and activation of the sympathetic excitation, which can increase the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines and aggravate ischemic injury. 25 Previous evidence has shown that NLR can be used as an effective predictor of END in patients with AIS, which was consistent with our findings.26 –28

Platelets play a significant role in atherosclerotic thrombosis, secrete and express many key mediators of coagulation, inflammation and atherosclerosis.29,30 MPV is an important marker of platelet production rate, activation and function, because larger platelets show higher enzymatic and metabolic activity than smaller ones. 31 Oji et al. demonstrated that high MPV values might be a predictive biomarker for END in patients with branch atheromatous disease. 32 Platelet activation is a pivotal link in the pathophysiology of thrombosis and inflammation. 33 Platelet activation leads to the release of adhesion molecules, chemokines, coagulation protein and pro-adhesion molecules, promoting cell adhesion, coagulation and proteolysis, ultimately accelerating atherosclerotic plaque formation.34,35 Thus, larger platelets can release more mediators, accelerating the formation and rupture of atherosclerotic plaque. Moreover, high MPV levels represent the rise of immature platelets or reticulocyte, suggesting that platelet renewal is accelerated. 36 Activated platelets produce plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 (PAI-1), platelet-rich emboli can reduce the reactivity of thrombus to alteplase. 37 The relationship between MPV and END after IVT still needs to be explored by more research.

In our study, we found BMI was an independent risk factor of ENDi with high specificity in predicting ENDi in AIS patients undergoing IVT. Its mechanism may be related to the following factors: (1) Obesity leads to chronic inflammation of adipose tissue, adipocytes secrete more inflammatory factors, then leading to endothelial dysfunction and atherosclerosis.38,39 (2) Obese patients may be prone to have more complications such as venous thromboembolism. 40 (3) The clot-dissolving effect of alteplase may be hindered by PAI-1 which seems to be overexpressed in adipose tissue. 41 (4) The insufficient dose of thrombolysis drugs caused by overweight leads to a low recanalization rate after IVT. 42

Obesity is a well-established risk factor for stroke, and BMI has been proved to be significantly associated with the risk for AIS. 43 However, the evidence of the relationship between BMI and outcome in AIS patients remains equivocal. A previous study showed that higher BMI after stroke is associated with a higher mortality risk. 44 On the contrary, Dicpinigaitis et al. demonstrated obese patients with AIS had a lower risk of in-hospital mortality, which suggested a protective effect of obesity against mortality. 45 Rozen et al. discovered a reverse J-shaped correlation between BMI and in-hospital mortality in patients with stroke, the mild and moderately obese patients (BMI 31–39 kg/m2) presented the lowest in-hospital mortality. 46 And some studies indicated that BMI was not related to early neurological improvement on NIHSS at 24 hours or functional outcome at discharge and 3 months in stroke patients treated with IVT.47,48 Although our study implicated that higher BMI was associated with ENDi, further well-designed studies are warranted to validate the relationship between BMI and END.

In our research population, we also found that patients with AF were more likely to suffer post-thrombolysis ENDi. This finding was consistent with previous literature result. 49 AF is a common cause of cardioembolism. AF can form a cardioembolic thrombus, which is more likely to obstruct large intracranial blood vessels and cause massive cerebral infarction. 50 In addition, due to the onset of cardioembolism is urgent, it is impossible for the collateral circulation to be sufficiently established. 51

In addition, we observed that there were significant differences in age and DM between the two groups, however, these two factors were not statistically significantly associated with ENDi in multivariate logistic regression analysis. A meta-analysis has demonstrated that age and DM were significantly associated with END after reperfusion therapy. 52 The reason for this discrepancy may be related to the smaller sample size in our study.

We constructed a nomogram prediction model of ENDi after IVT in AIS patients based on the NLR, MPV, BMI and AF. After the internal and external validation, we confirmed that the nomogram model had good discriminative efficacy and calibration. What’s more, the AUC or C-index of this model is greater than that of several previous models, which means that the predictive performance of this model is better than them.49,53 –55

This study has several limitations. First, this study is a retrospective study, selection bias could not be avoided. Second, it is a single center study, therefore, the sample size is limited. Third, further research should collect blood samples at multiple time points, which may have different results. What’s more, this predictive model needs to be further validated in patients from different regions and races. In future studies, more comprehensive data should be collected to explore the predictors of END after IVT.

Conclusions

In this study, we demonstrated that NLR, MPV, BMI and AF were independent risk factors and predictors of ENDi. The nomogram prediction model based on these four factors exhibited good discrimination and calibration power. It might be a reliable and easy-to-use tool to predict post-thrombolysis ENDi in AIS patients.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-1-jcb-10.1177_0271678X231200117 for Prediction of early neurological deterioration in acute ischemic stroke patients treated with intravenous thrombolysis by Tian Tian, Lanjing Wang, Jiali Xu, Yujie Jia, Kun Xue, Shuangfeng Huang, Tong Shen, Yumin Luo, Sijie Li and Lianqiu Min in Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow & Metabolism

Footnotes

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This study was supported by the National Key R&D Program of China (No. 2022YFC2408800) and National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 82171301, 81971114, 82274401).

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Authors’ contributions: TT conceived of the study idea, collected and analyzed the data. LW drafted the manuscript. JY, KX, SH and TS participated in the data collection. JX, SL, and LM helped to modify the manuscript. YL, SL, and LM participated in the coordination of the study. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

ORCID iD: Jiali Xu https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3651-4383

Supplementary material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- 1.Liu L, Villavicencio F, Yeung D, et al. National, regional, and global causes of mortality in 5–19-year-olds from 2000 to 2019: a systematic analysis. Lancet Glob Health 2022; 10: e337–e347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shim R, Wong CH. Ischemia, immunosuppression and infection – tackling the predicaments of post-stroke complications. Int J Mol Sci 2016; 17: 64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Eren F, Yilmaz SE. Neuroprotective approach in acute ischemic stroke: a systematic review of clinical and experimental studies. Brain Circ 2022; 8: 172–179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Powers WJ, Rabinstein AA, Ackerson T, et al. Guidelines for the early management of patients with acute ischemic stroke: 2019 update to the 2018 guidelines for the early management of acute ischemic stroke: a guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke 2019; 50: e344–e418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Siegler JE, Boehme AK, Kumar AD, et al. What change in the national institutes of health stroke scale should define neurologic deterioration in acute ischemic stroke? J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis 2013; 22: 675–682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Saver JL, Altman H. Relationship between neurologic deficit severity and final functional outcome shifts and strengthens during first hours after onset. Stroke 2012; 43: 1537–1541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mao S, Hu Y, Zheng X, et al. Correlation analysis of neutrophil/albumin ratio and leukocyte count/albumin ratio with ischemic stroke severity. Cardiol Cardiovasc Med 2023; 7: 32–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Seners P, Turc G, Oppenheim C, et al. Incidence, causes and predictors of neurological deterioration occurring within 24 h following acute ischaemic stroke: a systematic review with pathophysiological implications. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2015; 86: 87–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang YB, Su YY, He YB, et al. Early neurological deterioration after recanalization treatment in patients with acute ischemic stroke: a retrospective study. Chin Med J (Engl) 2018; 131: 137–143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tisserand M, Seners P, Turc G, et al. Mechanisms of unexplained neurological deterioration after intravenous thrombolysis. Stroke 2014; 45: 3527–3534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mitsias PD. Early neurological deterioration after intravenous thrombolysis: Still no end in sight in the quest for understanding END. Stroke 2020; 51: 2615–2617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ma J, Li M, Zhang M, et al. Protection of multiple ischemic organs by controlled reperfusion. Brain Circ 2021; 7: 241–246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang X, Jia X, Chen L, et al. Study on the predictive value of thromboelastography in early neurological deterioration in patients with primary acute cerebral infarction. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 2022; 2022: 4521003–4521007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 14.Lee H, Yun HJ, Ding Y. Timing is everything: Exercise therapy and remote ischemic conditioning for acute ischemic stroke patients. Brain Circ 2021; 7: 178–186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Geng HH, Wang Q, Li B, et al. Early neurological deterioration during the acute phase as a predictor of long-term outcome after first-ever ischemic stroke. Medicine (Baltimore) 2017; 96: e9068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liu H, Liu K, Zhang K, et al. Early neurological deterioration in patients with acute ischemic stroke: a prospective multicenter cohort study. Ther Adv Neurol Disord 2023; 16: 17562864221147743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Powers W, Rabinstein A, Ackerson T, et al. 2018 Guidelines for the early management of patients with acute ischemic stroke: a guideline for healthcare professionals from the American heart association/American stroke association. Stroke 2018; 49: e46–e110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jauch E, Saver J, Adams H, Council on Clinical Cardiology et al. Guidelines for the early management of patients with acute ischemic stroke: a guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke 2013; 44: 870–947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Seners P, Ben Hassen W, Lapergue B, et al. Prediction of early neurological deterioration in individuals with minor stroke and large vessel occlusion intended for intravenous thrombolysis alone. JAMA Neurol 2021; 78: 321–328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liu M, Liu X, Zhou M, et al. Impact of CircRNAs on ischemic stroke. Aging Dis 2022; 13: 329–339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim JY, Park J, Chang JY, et al. Inflammation after ischemic stroke: the role of leukocytes and glial cells. Exp Neurobiol 2016; 25: 241–251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jin P, Li X, Chen J, et al. Platelet-to-neutrophil ratio is a prognostic marker for 90-days outcome in acute ischemic stroke. J Clin Neurosci 2019; 63: 110–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Huang L, Chen Y, Liu R, et al. P-Glycoprotein aggravates blood brain barrier dysfunction in experimental ischemic stroke by inhibiting endothelial autophagy. Aging Dis 2022; 13: 1546–1561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gusdon AM, Gialdini G, Kone G, et al. Neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio and perihematomal edema growth in intracerebral hemorrhage. Stroke 2017; 48: 2589–2592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yuan CX, Zhang YN, Chen XY, et al. Association between malnutrition risk and hemorrhagic transformation in patients with acute ischemic stroke. Front Nutr 2022; 9: 993407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gong P, Xie Y, Jiang T, et al. Neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio predicts post-thrombolysis early neurological deterioration in acute ischemic stroke patients. Brain Behav 2019; 9: e01426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang C, Zhang Q, Ji M, et al. Prognostic value of the neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio in acute ischemic stroke patients treated with intravenous thrombolysis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Neurol 2021; 21: 191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang L, Song Q, Wang C, et al. Neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio predicts poor outcomes after acute ischemic stroke: a cohort study and systematic review. J Neurol Sci 2019; 406: 116445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Choi DH, Kang SH, Song H. Mean platelet volume: a potential biomarker of the risk and prognosis of heart disease. Korean J Intern Med 2016; 31: 1009–1017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hu Y, Zheng Y, Wang T, et al. VEGF, a key factor for blood brain barrier injury after cerebral ischemic stroke. Aging Dis 2022; 13: 647–654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gasparyan AY, Ayvazyan L, Mikhailidis DP, et al. Mean platelet volume: a link between thrombosis and inflammation? Curr Pharm Des 2011; 17: 47–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Oji S, Tomohisa D, Hara W, et al. Mean platelet volume is associated with early neurological deterioration in patients with branch atheromatous disease: Involvement of platelet activation. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis 2018; 27: 1624–1631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liu L, Xiao S, Wang Y, et al. Water-soluble tomato concentrate modulates shear-induced platelet aggregation and blood flow in vitro and in vivo. Front Nutr 2022; 9: 961301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kwon HW, Kim SD, Rhee MH, et al. Pharmacological actions of 5-hydroxyindolin-2 on modulation of platelet functions and thrombus formation via thromboxane A(2) inhibition and cAMP production. Int J Mol Sci 2022; 23: 14545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Puteri MU, Azmi NU, Kato M, et al. PCSK9 promotes cardiovascular diseases: Recent evidence about its association with platelet Activation-Induced myocardial infarction. Life (Basel) 2022; 12: 190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Choi JW, Lee KO, Jang YJ, et al. High mean platelet volume is associated with cerebral white matter hyperintensities in Non-Stroke individuals. Yonsei Med J 2023; 64: 35–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Di Meglio L, Desilles JP, Ollivier V, et al. Acute ischemic stroke thrombi have an outer shell that impairs fibrinolysis. Neurology 2019; 93: e1686–e1698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Webb AJS, Lawson A, Mazzucco S, et al. Body mass index and arterial stiffness are associated with greater beat-to-beat blood pressure variability after transient ischemic attack or minor stroke. Stroke 2021; 52: 1330–1338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Li Z, Yang W, Yang Y, et al. The astragaloside IV derivative LS-102 ameliorates obesity-related nephropathy. Drug Des Devel Ther 2022; 16: 647–664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhao Y, Guo M, Li D, et al. Pharmacokinetics and dosing regimens of direct oral anticoagulants in morbidly obese patients: an updated literature review. Clin Appl Thromb Hemost 2023; 29: 10760296231153638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Oesch L, Tatlisumak T, Arnold M, et al. Obesity paradox in stroke – myth or reality? A systematic review. PLoS One 2017; 12: e0171334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sarikaya H, Elmas F, Arnold M, et al. Impact of obesity on stroke outcome after intravenous thrombolysis. Stroke 2011; 42: 2330–2332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Strazzullo P, D'Elia L, Cairella G, et al. Excess body weight and incidence of stroke: meta-analysis of prospective studies with 2 million participants. Stroke 2010; 41: e418-426–e426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Towfighi A, Ovbiagele B. The impact of body mass index on mortality after stroke. Stroke 2009; 40: 2704–2708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dicpinigaitis AJ, Palumbo KE, Gandhi CD, et al. Association of elevated body mass index with functional outcome and mortality following acute ischemic stroke: the obesity paradox revisited. Cerebrovasc Dis 2022; 51: 565–569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rozen G, Elbaz-Greener G, Margolis G, et al. The obesity paradox in real-world nation-wide cohort of patients admitted for a stroke in the U.S. J Clin Med 2022; 11: 1678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gensicke H, Wicht A, Bill O, et al. Impact of body mass index on outcome in stroke patients treated with intravenous thrombolysis. Eur j Neurol 2016; 23: 1705–1712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zambrano Espinoza MD, Lail NS, Vaughn CB, et al. Does body mass index impact the outcome of stroke patients who received intravenous thrombolysis? Cerebrovasc Dis 2021; 50: 141–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gong P, Zhang X, Gong Y, et al. A novel nomogram to predict early neurological deterioration in patients with acute ischaemic stroke. Eur j Neurol 2020; 27: 1996–2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jiao J, Liu S, Cui C, et al. Endovascular thrombectomy for acute ischemic stroke in elderly patients with atrial fibrillation. BMC Neurol 2022; 22: 100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wang L, Liu L, Zhao Y, et al. Analysis of factors associated with hemorrhagic transformation in acute cerebellar infarction. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis 2022; 31: 106538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Shi HX, Li C, Zhang YQ, et al. Predictors of early neurological deterioration occurring within 24 h in acute ischemic stroke following reperfusion therapy: a systematic review and Meta-Analysis. J Integr Neurosci 2023; 22: 52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wang M, Liu Y. Construction of a prediction model for risk of early neurological deterioration following intravenous thrombolysis in patients with acute ischemic stroke. Technol Health Care 2023; null: null. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Jin M, Peng Q, Wang Y. Post-thrombolysis early neurological deterioration occurs with or without hemorrhagic transformation in acute cerebral infarction: risk factors, prediction model and prognosis. Heliyon 2023; 9: e15620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Xie X, Xiao J, Wang Y, et al. Predictive model of early neurological deterioration in patients with acute ischemic stroke: a retrospective cohort study. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis 2021; 30: 105459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-1-jcb-10.1177_0271678X231200117 for Prediction of early neurological deterioration in acute ischemic stroke patients treated with intravenous thrombolysis by Tian Tian, Lanjing Wang, Jiali Xu, Yujie Jia, Kun Xue, Shuangfeng Huang, Tong Shen, Yumin Luo, Sijie Li and Lianqiu Min in Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow & Metabolism