Summary

Chronic pain is a severely debilitating condition with enormous socioeconomic costs. Current treatment regimens with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), steroids, or opioids have been largely unsatisfactory with uncertain benefits or severe long-term side effects. This is mainly because chronic pain has a multifactorial aetiology. Although conventional pain medications can alleviate pain by keeping several dysfunctional pathways under control, they can mask other underlying pathological causes, ultimately worsening nerve pathologies and pain outcome. Recent preclinical studies have shown that endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress could be a central hub for triggering multiple molecular cascades involved in the development of chronic pain. Several ER stress inhibitors and unfolded protein response modulators, which have been tested in randomised clinical trials or apprpoved by the US Food and Drug Administration for other chronic diseases, significantly alleviated hyperalgesia in multiple preclinical pain models. Although the role of ER stress in neurodegenerative disorders, metabolic disorders, and cancer has been well established, research on ER stress and chronic pain is still in its infancy. Here, we critically analyse preclinical studies and explore how ER stress can mechanistically act as a central node to drive development and progression of chronic pain. We also discuss therapeutic prospects, benefits, and pitfalls of using ER stress inhibitors and unfolded protein response modulators for managing intractable chronic pain. In the future, targeting ER stress to impact multiple molecular networks might be an attractive therapeutic strategy against chronic pain refractory to steroids, NSAIDs, or opioids. This novel therapeutic strategy could provide solutions for the opioid crisis and public health challenge.

Keywords: animal model, apoptosis, chronic pain, endoplasmic reticulum stress, inflammation, ion channel, mitochondrial dysfunction, unfolded protein response

Chronic pain is a debilitating condition affecting millions of people worldwide. Chronic pain commonly arises from hyperexcitability of sensory neurones induced by chemicals released from nerve damage or associated inflammation.1,2 Thus, current therapies such as opioids, steroids, and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) mainly focus on reducing nociceptive neurotransmission and countering inflammation. Still, these therapies have been largely unsatisfactory with uncertain benefits or severe long-term side effects, including but not limited to gastrointestinal bleeding, addiction, and respiratory depression.1, 2, 3, 4 The major cause for treatment failure, besides tolerance development, is that chronic pain has a multifactorial aetiology. Not only inflammation, but also ion channel dysregulation, aberrant Ca2+ handling, hypersensitisation, mitochondrial dysfunction, apoptosis, compromised axoplasmic transport, autophagy impairment, endothelial abnormalities, etc. can all contribute to chronic pain.1, 2, 3, 4, 5 Thus, although opioids and NSAIDs can alleviate symptoms by keeping several dysfunctional pathways under control, they can mask other underlying pathological causes. These pathways can later become overactive to exacerbate nerve pathologies and make therapies eventually ineffective. Indeed, chronic opioids, steroids, and NSAIDs could prolong pain duration, worsen pain outcome, and even induce chronic pain.6,7

Recent studies have suggested that endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress is a central hub for triggering multiple molecular cascades involved in the development of chronic pain. ER is a cellular factory for the majority of secretory and membrane proteins. Nascent proteins undergo strict quality control assisted by ER-resident chaperones and enzymes to ensure proper folding and conformational maturation.8,9 Proteins that fail to fold correctly are cleared through ER-associated degradation (ERAD) or autophagic degradation.8,9 Despite these ER quality control systems, misfolded/unfolded proteins can end up accumulating in the ER lumen, a condition known as ‘ER stress’.10,11

The role of ER stress in multiple chronic diseases such as neurodegenerative disorders, diabetes mellitus, obesity, and cancer have been extensively studied and well established.12, 13, 14, 15, 16 Several clinical trials are undergoing or have already been completed to test the efficacy of ER stress inhibitors in these diseases. The ER stress inhibitor AMX0035 (Relyvrio), a coformulation of chemical chaperones 4-phenylbutyrate (4-PBA) and tauroursodeoxycholic acid (TUDCA), was recently approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) as a treatment for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis based on promising clinical trial results.17 However, research on the relationship between ER stress and chronic pain is still in its infancy. In this review, we describe emerging evidence from preclinical models that supports functional involvement of ER stress in chronic pain. We explore how ER stress can act as a central node to drive development and progression of chronic pain. In the future, targeting ER stress to impact multiple molecular networks might be an attractive option to manage pain refractory to steroids, NSAIDs, or opioids also discuss therapeutic prospects, benefits, and pitfalls of using ER stress inhibitors for managing intractable chronic pain.

Endoplasmic reticulum stress and the unfolded protein response

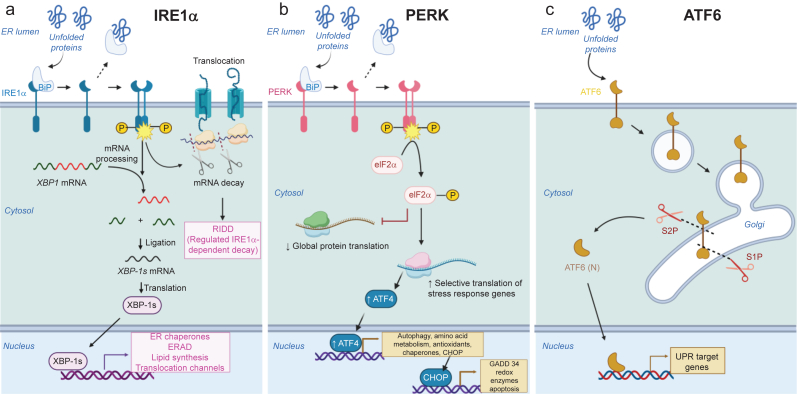

ER stress occurs when protein synthesis increases beyond the folding capacity or protein folding is impaired. To overcome ER stress and ensure healthy proteome, ER mounts the unfolded protein response (UPR).10,11 The UPR allows the ER to relieve the load of misfolded proteins by fine-tuning protein translation and transcriptionally remodelling the proteostasis network. UPR pathways consist of three signalling cascades triggered by ER-resident transmembrane proteins10,11 (Fig. 1): inositol requiring enzyme 1α (IRE1α), double-stranded RNA-activated protein kinase (PKR)-like ER kinase (PERK), and activating transcription factor 6 (ATF6).

Fig 1.

Three branches of the UPR triggered by ER stress. (a) IRE1α pathway. Upon sensing misfolded proteins, cytosolic kinase domains of IRE1α dimerise, leading to their trans-autophosphorylation. Subsequently, cytosolic RNase domains of IRE1α become activated, causing excision of intron from the mRNA encoding the transcription factor, X-box-binding protein 1 (XBP1). The spliced XBP1 (XBP1-s) is then translated into the active form, which upregulates genes important for folding, export, and degradation of misfolded proteins. IRE1α also cleaves several other mRNAs via regulated IRE1-dependent decay (RIDD). RIDD decreases the ER protein load by lowering mRNA abundance. (b) PERK pathway. In response to ER stress, PERK oligomerises and becomes autophosphorylated, which in turn inactivates eukaryotic translation initiation factor 2α (eIF2α) via phosphorylation. This attenuates global mRNA translation, reduces the protein influx to ER, and ultimately alleviates ER stress. eIF2α phosphorylation also selectively upregulates translation of genes important for stress responses mainly via ATF4-dependent translation. (c) ATF6 pathway. Under ER stress, ATF6 pinches off from the ER membrane to form a vesicle and enters Golgi. There, its luminal and transmembrane domains are cleaved by proteases S1P and S2P, respectively. The resulting N-terminal cytosolic fragment (ATF6p50) translocates into nucleus and triggers transcription of UPR target genes involved in folding, secretion, and degradation of misfolded proteins. ATF6, activating transcription factor 6; ER, endoplasmic reticulum; ERAD, endoplasmic reticulum-associated degradation; IRE1α, inositol requiring enzyme 1α; mRNA, messenger RNA; PERK, protein kinase-like endoplasmic reticulum kinase; UPR, unfolded protein response.

IRE1α is a bifunctional kinase/endoribonuclease whose ER luminal domain oligomerises in the ER membrane in response to ER stress10,11 (Fig. 1a). This lateral luminal oligomerisation brings cytosolic kinase domains of IRE1α together, leading to their trans-autophosphorylation, cofactor binding, and conformational changes.10,11 Subsequently, cytosolic RNase domains adjacent to kinase domains become activated, causing excision of 26-nucleotide intron from the mRNA encoding the transcription factor X-box-binding protein 1 (XBP1). The spliced XBP1 (XBP-1s) is then translated into the active form, which upregulates genes important for folding, export, and degradation of misfolded proteins (e.g. chaperones, translocation channels, and ERAD proteins).10,11,18,19 This collectively decreases the ER load of misfolded proteins. RNase of IRE1α cleaves not only XBP1 but also several other mRNAs that contain CUGCAG motifs within a stem-loop structure.10,11,20,21 This so-called regulated IRE1α-dependent decay (RIDD) further decreases the ER protein load by lowering mRNA abundance.21

The second branch of the UPR is mediated by PERK (Fig. 1b). In response to ER stress, PERK, similar to IRE1α, oligomerises and becomes autophosphorylated, which in turn inactivates eukaryotic translation initiation factor 2α (eIF2α) via phosphorylation.10,11,22 In this way, PERK inhibits mRNA translation, reduces the protein influx to ER, and ultimately alleviates ER stress.10,11,22 PERK decreases ER stress not only by downregulating global protein translation, but also by selectively upregulating translation of genes important for stress responses.10,11,23 Typically, mRNAs encoding these stress response genes (e.g. ATF4) have long 5′-UTR with multiple short upstream open reading frames (uORFs) and complicated secondary structures.23,24 As a result, under normal conditions, translation of these genes is low as ribosome initiation predominantly occurs at uORFs and ribosomes are thereby prevented from accessing the coding sequence. However, when eIF2α becomes inactivated via PERK during ER stress, scanning ribosomes can bypass uORF without translation initiation, allowing the main coding sequence to be translated. For these reasons, translation of the transcription factor ATF4 can be selectively enhanced under ER stress, which upregulates several genes (e.g. GADD34, binding immunoglobulin protein ([BiP], and C/EBP homologous protein [CHOP]) involved in amino acid metabolism, autophagy, protein folding, redox homeostasis, apoptosis, etc.10,11,23, 24, 25 This ATF4-mediated integrated stress response can protect cells against ER stress. If ER stress is severe or prolonged, ATF4-dependent upregulation of CHOP, BIM, and PUMA can promote the release of cytochrome c from the mitochondria and activate caspases, which ultimately leads to apoptosis.

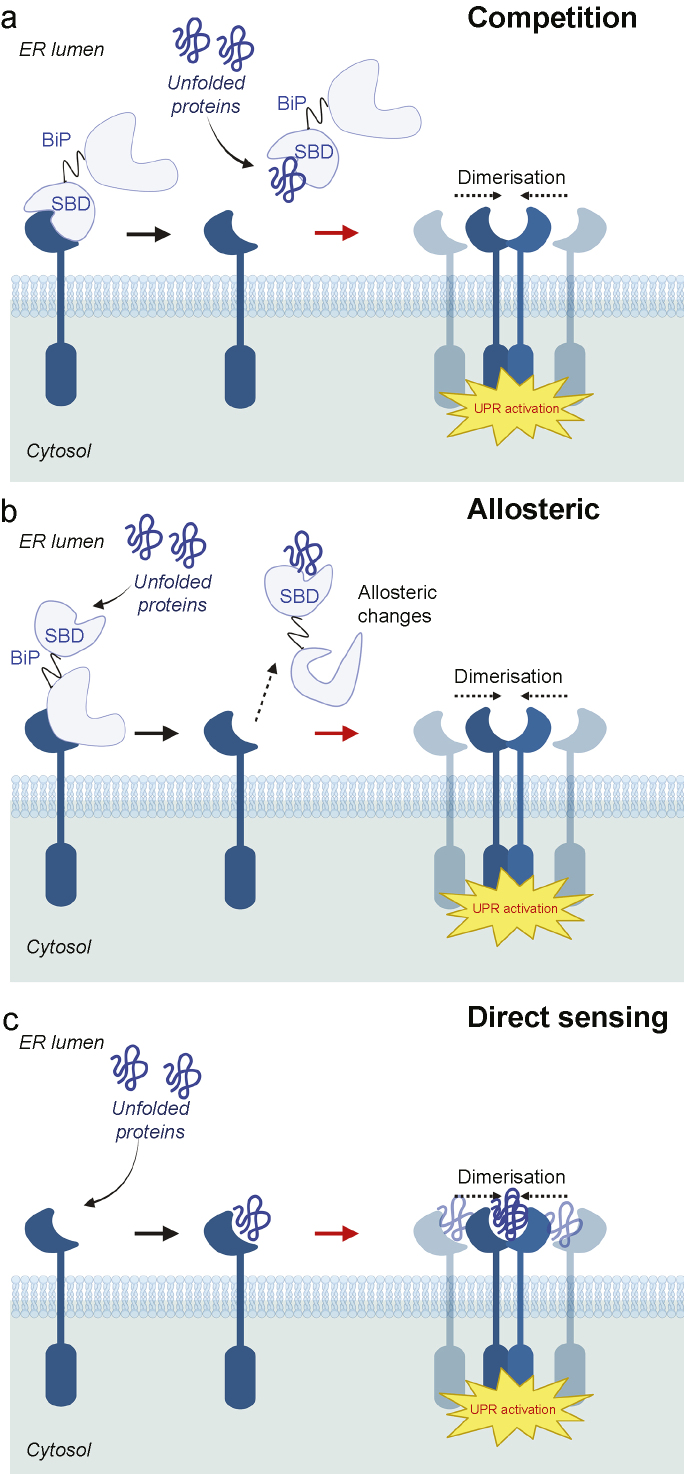

The transcriptional factor ATF6 defines the third branch of UPR10,11 (Fig. 1c). Under normal conditions, ATF6 remains as an inactive ER membrane-bound protein. However, under ER stress, ATF6 pinches off from the ER membrane to form a vesicle and enters Golgi. There, its luminal and transmembrane domains are cleaved by proteases S1P and S2P, respectively. The resulting N-terminal cytosolic fragment (ATF6p50) translocates into nucleus and triggers transcription of UPR target genes involved in folding, secretion, and degradation of misfolded proteins such as BiP, protein disulfide isomerase (PDI), GRP94, ERAD proteins, etc. UPR appears to be activated by both BiP-dependent and BiP-independent recognitions of misfolded proteins10,11,26,27 (Fig. 2).

Fig 2.

Schematic representations of ER stress-sensing mechanisms. (a) Competition model (binding immunoglobulin protein (BiP)-dependent indirect sensing mechanism). Under normal conditions, IRE1α/PERK/ATF6 are maintained in inactive states as their ER luminal domains (LDs) bind to the substrate binding domain (SBD) of BiP. However, under ER stress, unfolded/misfolded proteins bind to the BiP SBD, thereby releasing IRE1α/PERK LDs to dimerise for activation and enabling ATF6 to translocate to Golgi. (b) Allosteric model (BiP-dependent indirect sensing mechanism). Misfolded proteins bind to SBD of BiP whereas IRE1α/PERK/ATF6 LDs bind to the nucleotide binding domain (NBD) of BiP without competition. Binding of misfolded proteins to BiP SBD causes conformational changes, leading to dissociation of LDs of UPR transducers from BiP NBD. (c) BiP independent direct sensing mechanism. LDs of UPR transducers have binding pockets that directly send and bind to misfolded proteins, triggering UPR activation. ATF6, activating transcription factor 6; ER, endoplasmic reticulum; IRE1α, inositol requiring enzyme 1α; PERK, protein kinase-like endoplasmic reticulum kinase; UPR, unfolded protein response.

The role of endoplasmic reticulum stress in chronic pain

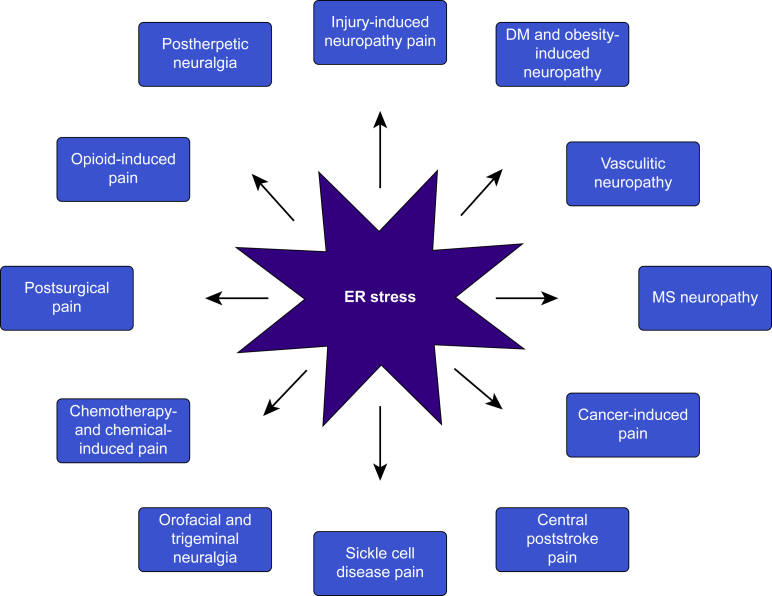

Activation of all three UPR branches of ER stress has been implicated in neurodegenerative disorders,28 diabetes,29 obesity,30 and cancer,31 extensively reviewed in13,16 and summarised in Table 1. Chemical chaperones that directly reduce ER stress such as 4-PBA, TUDCA, and trimethylamine N-oxide (TMAO) have reliably ameliorated neurodegeneration, metabolic disorders, and cancer in multiple animal models. Chronic pain shares many aetiological pathways implicated in these diseases. In this section, we review how ER stress markers and the UPR are altered in animal models for various types of chronic pain such as neuropathic pain, inflammatory pain, cancer pain, postoperative pain, etc. (Fig. 3 and Table 2). We also review how pharmacological and genetic interventions manipulating ER stress and the UPR impact the pain outcome (Table 2, Table 3).

Table 1.

Studies examining the role of ER stress in chronic diseases. 4-PBA, 4-phenylbutyrate; AD, Alzheimer disease; ALS, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis; ATF, activating transcription factor; BiP, binding immunoglobulin protein; BID, twice per day; CHOP, C/EBP homologous protein; eIF, eukaryotic translation initiation factor; ER, endoplasmic reticulum; HFD, high fat diet; HSP, heat shock protein; IRE1α, inositol requiring enzyme 1α; ISRIB, integrated stress response inhibitor; PD, Parkinson disease; PDI, protein disulfide isomerase; PERK, protein kinase-like endoplasmic reticulum kinase; SERCA, sarco/endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase; SOD1, superoxide dismutase 1; T1DM, type 1 diabetes mellitus; T2DM, type 2 diabetes mellitus; TID, three times per day; TMAO, trimethylamine N-oxide; TUDCA, tauroursodeoxycholic acid; XBP1, X-box-binding protein 1; XBP1-s, spliced X-box-binding protein 1.

| Disease | Changes in ER stress markers | Drugs/interventions to reduce ER stress | Outcomes | Clinical trials |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AD | ↑BiP, ↑PDI, ↑chaperones (Hsp72, Hsp73, Grp94), ↑CHOP, ↑p-IRE1α, ↑XBP1-s, ↑p-PERK, ↑p-eIF2α in hippocampus, entorhinal cortex, temporal cortex, and frontal cortex of AD patients and animal models |

|

↓Aβ and p-tau accumulation, ↓brain atrophy, cholinergic neurodegeneration, ↑synaptic plasticity, ↑neuronal protein synthesis, ↑learning, spatial memory in AD rodent models |

|

| PD | ↑BiP, ↑CHOP, ↑PDI, ↑Hsp70, ↑Hsp27, ↑p-PERK, ↑p-eIF2α, ↑p-IRE1α, ↑XBP1-s, ↑ATF4 in dopaminergic neurones of substantia nigra, spinal cord, and brainstem of PD patients and animal models |

|

↓α-synuclein accumulation, ↓dopaminergic neurodegeneration, ↑locomotor function, ↑survival in PD models of Drosophila and rodents |

|

| ALS | ↑BiP, ↑CHOP, ↑PDI, ↑p-PERK, ↑p-eIF2α, ↑p-IRE1α, ↑XBP1-s, ↑ATF6, ↑ATF4, dilated and fragmented ER filled with protein aggregates in spinal cords and motor neurones of ALS patients and ALS mice models |

|

↓SOD1 aggregates, ↓neurodegeneration, ↑neuromuscular junction innervation, ↑neurite outgrowth, ↑locomotor function, ↓disease progression, ↑survival in ALS models of Caenorhabditis elegans, Drosophila, zebrafish, and mice |

|

| Obesity | ↑BiP, ↑CHOP, ↑PDI, ↑p-PERK, ↑p-eIF2α, ↑XBP-1s, ↑ATF6 in liver and adipose tissues of HFD-fed mice, ob/ob mice, and obese human subjects |

|

↓Fat mass, ↓body weight, ↑hepatic and muscle insulin sensitivity, ↓hepatic steatosis and fibrosis in HFD-fed mice and ob/ob mice |

|

| T1DM, T2DM | ↑BiP, ↑CHOP, ↑PDI, ↑Hsp27, ↑Hsp 40, ↑Hsp 70, ↑p-PERK, ↑p-eIF2α, ↑p-IRE1α, ↑XBP1-s, ↑ATF 3,4,6, ↑ER dilation, ↓SERCA in β-cells of T1DM and T2DM mice, rats, and patients |

|

↑Insulin sensitivity in muscle and adipose tissues, ↑insulin secretion, ↑glucose tolerance, ↓β-cell apoptosis, ↓hyperglycaemia, ↓hyperlipidaemia, ↓body weight, ↓cataract, ↓nephropathy, ↓neuropathy, ↓fatty liver disease, ↓muscle atrophy in T1DM and T2DM rodent models | TUDCA: phase II [NCT02218619] (1750 mg pill day−1 × 12 months) |

| Cancer | ↑BiP, ↑p-PERK, ↑p-eIF2α, ↑p-IRE1α, ↑XBP1-s, ↑ATF 6 in haematopoietic tumours and solid tumours in brain, breast, lung, oesophagus, pancreas, liver, colon, prostate, ovaries |

|

↓Tumour burden, ↓formation, growth, angiogenesis, and invasion of tumours, ↑tumour apoptosis, ↑chemosensitivity |

|

Fig 3.

Types of chronic pain that may be driven by ER stress. DM, diabetes mellitus; ER, endoplasmic reticulum; MS, multiple sclerosis.

Table 2.

Studies examining the role of ER stress in chronic pain. 4-PBA, 4-phenylbutyrate; ATF, activating transcription factor; BiP, binding immunoglobulin protein; CCI, chronic constriction injury; CFA, complete Freund's adjuvant; CICR, Ca2+-induced Ca2+-release; CIPN, chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy; CHOP, C/EBP homologous protein; DRG, dorsal root ganglion; eIF, eukaryotic translation initiation factor; ER, endoplasmic reticulum; HSP, Heat Shock Protein; IPA, indole-3-propionic acid; IRE1α, inositol requiring enzyme 1α; LXR, liver X receptor; MS, multiple sclerosis; mRNA, messenger RNA; OIH, opioid-induced hyperalgesia; P2X, purinoreceptor; PDI, protein disulfide isomerase; PERK, protein kinase-like endoplasmic reticulum kinase; RVM, rostral ventromedial medulla; SERCA, sarco/endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase; siRNA, small interfering RNA; SNL, spinal nerve ligation; T1DM, type 1 diabetes mellitus; T2DM, type 2 diabetes mellitus; TMAO, trimethylamine N-oxide; TPAU, 1-trifluoromethoxyphenyl-3-(1-acetylpiperidin-4-yl) urea; TPPU, N-(1-(1-oxopropy)-4-piperidinly)-N'-(trifluoromethoxy)phenyl)-urea; TUDCA, tauroursodeoxycholic acid; TUPS, 1-(1-methanosulfonyl-piperidin-4-yl)-3-(4-trifluoromethoxy-phenyl)-urea; XBP1, X-box-binding protein 1.

| Animal models/patients | Changes in ER stress markers | Drugs/interventions to reduce ER stress | Pain outcomes | Refs |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rat models of nerve injury-induced neuropathic pain (SNL, CCI) | ↑BiP mRNA/protein, ↑PDI protein, ↑PERK/IRE1α/ATF6 activation, ↑p-eIF2α, ↑XBP splicing, ↑ATF4, ↑CHOP mRNA/protein, swollen ER cisternae, ↑ER-phagy, ↓SERCA2b mRNA/protein, ↓ER Ca2+ stores, ↑polyubiquitinated protein aggregates in spinal dorsal horn/DRG neurones, satellite glia, and RVM |

|

↑Print area, ↑duration of stance phase, ↑mechanical pain withdrawal threshold, ↓thermal/cold pain hypersensitivity | 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40 |

| Rat models of T1DM neuropathic pain | ↑BiP mRNA/protein, ↑PERK/IRE1α/ATF6 activation, ↑p-eIF2α, ↑ATF4 mRNA/protein, ↑XBP1 mRNA/protein in sciatic nerves, DRG neurones, paw |

|

↑Mechanical pain withdrawal threshold, ↓thermal/cold pain hypersensitivity | 41, 42, 43, 44 |

| Mice models of T2DM/obesity-induced neuropathic pain | ↑BiP mRNA/protein, ↑GRP94, ↓p-eIF2α, ↑ATF4 mRNA, ↑XBP splicing, ↑CHOP mRNA in DRG neurones |

|

↑Mechanical pain withdrawal threshold, ↓thermal pain hypersensitivity | 45,46 |

| Rat models of vasculitic neuropathy (ischaemia-reperfusion) | ↑PERK/IRE1α/ATF6 activation, ↑p-eIF2α, ↑ATF4, ↑CHOP in sciatic nerves |

|

↑Mechanical pain withdrawal threshold, ↓thermal pain hypersensitivity, ↑grip strength | 47,48 |

| Mice models of MS neuropathy | ↑BiP protein, ↑p-eIF2α, ↑XBP1 splicing, ↑CHOP mRNA, ↑ER CICR in DRG |

|

↑Mechanical pain withdrawal threshold, ↓orofacial pain behaviors | 49 |

| MS patients (post-mortem DRG tissues) | ↑BiP protein, ↑XBP mRNA/protein | 49 | ||

| Rat models of central poststroke pain | ↑BiP mRNA/protein, ↑PERK/IRE1α/ATF6 activation, ↑p-eIF2α, ↑XBP1 splicing, swollen ER cisternae in perithalamic lesions |

|

↑Mechanical pain withdrawal threshold | 50 |

| Mice and rat models of bone cancer pain | ↑BiP protein, ↑PERK/IRE1α/ATF6 activation, ↑p-eIF2α, ↑XBP splicing, ↑CHOP protein, swollen ER cisternae with accumulated vesicles in spinal dorsal horn neurones (mostly GABAergic) and astrocytes |

|

↑Mechanical pain withdrawal threshold, ↓thermal pain hypersensitivity, ↓spontaneous flinches | 51,52 |

| Rat models of CIPN (vincristine, paclitaxel) | ↑BiP mRNA, ↑ATF6 mRNA, ↑PERK mRNA, ↑IRE1α mRNA in the sciatic nerve |

|

↑Mechanical pain withdrawal threshold, ↓thermal/cold pain hypersensitivity | 53, 54, 55 |

| Mice and rat models of chemical-induced inflammatory pain (acetic acid, formalin, CFA) | ↑BiP protein, ↑PERK activation, ↑ATF6 protein in the spinal dorsal horn |

|

↓Writhing behaviours, ↓licking activity |

56, 57, 58 |

| Mice models of postsurgical pain (paw incision) | ↑BiP protein, ↑PERK activation, ↑ATF6 protein in the spinal dorsal horn |

|

↑Balanced paw weight distribution, ↓grimace, ↓guarding | 59 |

| Mice models of OIH | ↑BiP protein, ↑PERK/IRE1α/ATF6 activation, ↑p-eIF2α, ↑XBP1 protein, ↑HSP70 release in spinal dorsal horn and periaqueductal gray neurones |

|

↑Tail flick latency, ↓thermal pain hypersensitivity | 60,61 |

| Mice models of pain in sickle cell disease | ↑XBP splicing, ↑CHOP protein, swollen ER cisternae in spinal neurones and microglia |

|

↑Mechanical pain withdrawal threshold, ↑grip force, ↓thermal/cold pain hypersensitivity | 62 |

| Rat models of orofacial pain and trigeminal neuralgia | ↑BiP protein/mRNA, ↑p-eIF2α, ↑ATF4 mRNA, swollen ER cisternae in trigeminal ganglion |

|

↓Thermal pain hypersensitivity | 40,58 |

| Rat models of postherpetic neuralgia | ↑PERK/IRE1α/ATF6 activation |

|

↑Mechanical pain withdrawal threshold | 63 |

Table 3.

Pain studies with ER stress inducers. ER, endoplasmic reticulum.

| Drugs that increase ER stress | Mode of action | Pain phenotypes examined and outcomes | Refs |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tunicamycin | N-glycosylation inhibitor | ↓Mechanical pain withdrawal threshold, ↑thermal/cold pain hypersensitivity, ↑discomfort, licking, shacking, guarding, swelling | 35,37,41,50 |

| Dimethyl-celecoxib | ER Ca2+-ATPase inhibitor | ↓Mechanical pain withdrawal threshold, ↑discomfort, licking, shacking, guarding, swelling | 41 |

| Thapsigargin | SERCA inhibitor | ↓Mechanical pain withdrawal threshold, ↑thermal pain hypersensitivity | 34,38,52 |

| SR9243 | Liver X receptor antagonist | ↓Mechanical pain withdrawal threshold, ↑thermal pain hypersensitivity | 39 |

| 3-methyladenine | Autophagy/ER-phagy inhibitor | ↓Mechanical pain withdrawal threshold, ↑thermal pain hypersensitivity | 35 |

Neuropathic pain models induced by nerve ligation

Rodent models of spinal nerve ligation (SNL) show increased sensitivity to mechanical, thermal, and cold pain.64 After SNL, rats showed increased ER stress in the ipsilateral lumbar spinal dorsal horn,33, 34, 35, 36 lumbar dorsal root ganglion (DRG),37,38 and rostral ventromedial medulla,35 as demonstrated by upregulation of binding immunoglobulin protein (BiP) and the chaperone PDI. Consistent with these elevated ER stress markers, after SNL, ER lumen of neurones was significantly swollen as a result of accumulations of polyubiquitinated protein aggregates.33,34 To alleviate ER stress, all three UPR branches were activated after SNL. IRE1α phosphorylation increased,34,35 leading to greater splicing and nuclear translocation of XBP1.33,34,37 PERK was also activated,34,35 resulting in greater eIF2α phosphorylation33 and ATF4 upregulation.35 This might relieve ER stress by attenuating protein translation and selectively upregulating stress response genes. Indeed, after SNL, CHOP, one of the ATF4 target genes, was upregulated and localised to the nucleus to enhance transcriptions of redox enzymes.37 Finally, ATF6 was upregulated and activated to be translocated to the nucleus.33, 34, 35 ER stress and UPR activation were primarily present in TRPV1-positive sensory neurones and NF200-positive large myelinated A-fiber neurones.33,37 However, UPR activation was also evident in satellite glial cells in DRG including astrocytes and microglia.33,34,37 Another way to counteract ER stress besides UPR is ER-phagy, a form of macroautophagy that selectively degrades damaged ER. Interestingly, SNL caused autophagic markers and FAM134B, the ER resident receptor that facilitates ER-phagy, to be elevated in the spinal cord.35 All these studies collectively suggest that ER stress is prominent in SNL models of neuropathic pain.

Similar findings were observed in the chronic constriction injury (CCI)-induced neuropathic pain model. For example, IRE1α phosphorylation was increased, leading to greater XBP1 splicing.39 Also, PERK was more in phosphorylated states, leading to greater eIF2α phosphorylation and CHOP upregulation.39 CCI animal models had reduced ER Ca2+ stores, which is essential for the proper enzymatic activity of ER chaperones.38 This is because sarco/endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase (SERCA), which actively pumps Ca2+ from cytoplasm into ER to maintain ER Ca2+ stores, was downregulated under CCI. Deficient ER Ca2+ stores and subsequently compromised protein folding may have contributed to ER stress in CCI animal models.

Several drugs that relieve ER stress have been shown to improve pain outcome in these animal models. 4-PBA, an FDA-approved drug with chemical chaperone activity, can effectively refold misfolded proteins, prevent protein aggregations, and reduce ER stress.65, 66, 67, 68 In the SNL rat model (Sprague–Dawley), 4-PBA attenuated BiP upregulation, ameliorated PERK/IRE1α/ATF6 activation, and improved ER-phagy.35 4-PBA treatment to relieve ER stress significantly toned down mechanical and thermal hyperalgesia.35 TUDCA, a hydrophilic bile acid, is another chemical chaperone that is well known to abate ER stress.69 Intrathecal TUDCA injection not only reversed all the ER stress markers, but also decreased mechanical pain hypersensitivity in the SNL rat model (Wistar).34 Consistent with these findings, genetic and pharmacological augmentation of SERCA2b activity to alleviate ER stress and restore ER morphologies caused relief of mechanical and thermal allodynia in the CCI rat model (Sprague–Dawley).38

Further, multiple drugs that were found to indirectly reduce ER stress and prevent UPR overactivation improved pain phenotypes. For example, liver X receptor (LXR) agonist α-asarone, which was discovered to downregulate CHOP and tone down PERK/IRE1α activation, relieved CCI-induced mechanical allodynia and thermal hyperalgesia in Sprague–Dawley rats.39 However, concomitant treatments with the LXR antagonist SR9243 reversed α-asarone-induced improvements in ER stress markers and abrogated antinociceptive effects.39 Also, commonly used anaesthetic agents with sedative properties such as dexmedetomidine and ketamine downregulated BiP, enhanced ER-phagy, and ameliorated mechanical and thermal hyperalgesia.35,36 In addition, inducing autophagy to enhance ER-phagy alleviated mechanical and thermal hyperalgesia, whereas 3-methyladenine to inhibit autophagy and exacerbate ER-phagy worsened mechanical and thermal hyperalgesia.35

However, drugs that increase ER stress not only exacerbated pain in SNL models, but also triggered pain in healthy rats. Tunicamycin potently induces ER stress by inhibiting N-glycosylation, which plays a vital role in protein folding.70 Intrathecal application of tunicamycin increased BiP expression and induced mechanical/thermal/cold hyperalgesia in healthy Sprague–Dawley rats.37 Tunicamycin injection after SNL further upregulated BiP, enhanced PERK/IRE1α/ATF6 activation even more, and exacerbated mechanical/thermal pain hypersensitivity.35 Thapsigargin is another drug that triggers ER stress by irreversibly inhibiting SERCA and depleting ER Ca2+ stores necessary for activation of chaperones.71 Similar to tunicamycin, thapsigargin upregulated BiP, activated PERK/IRE1α/ATF6 in spinal tissues, and caused spinal dorsal horn and primary DRG neurones to be hyperexcitable, inducing mechanical allodynia in healthy Wistar and Sprague–Dawley rats.34,38

All these studies strongly suggest that ER stress may contribute to the pathogenesis of nerve injury-induced chronic pain. However, whether UPR activation in response to ER stress is beneficial for pain outcome is still unclear. Multiple studies suggest that chronic hyperactivation of UPR branches can lead to neuropathic pain potentially by triggering inflammation and inducing apoptosis of neurones. For example, directly reducing UPR overactivation via intrathecal ATF6 small interfering RNA (siRNA) alleviated mechanical allodynia.33 However, a few studies with salubrinal suggest that certain degree of UPR activation may actually relieve ER stress and is thereby beneficial for alleviating pain. Salubrinal is a selective eIF2α dephosphorylation inhibitor, thus activating the PERK branch of UPR via persistent eIF2α phosphorylation.72 Salubrinal can thereby relieve ER stress by attenuating protein translation and decreasing the load of misfolded proteins.4,73 In the SNL rat model (Sprague–Dawley), salubrinal downregulated CHOP expression in DRG and ameliorated mechanical/thermal/cold hyperalgesia.37 Therefore, sustaining optimal level of UPR activation to lower ER stress without triggering inflammation and apoptosis may be critical for ameliorating neuropathic pain.

Neuropathic pain models induced by metabolic dysfunction and vasculitis

The role of ER stress in diabetic neuropathy has been increasingly appreciated based on studies with type 1 and type 2 diabetes mellitus (T1DM and T2DM) rodent models. Similar to patients with diabetic neuropathy, T1DM rats showed tactile allodynia, thermal/cold hyperalgesia, and prominent loss of intraepidermal nerve fibres.41, 42, 43 ER stress markers were upregulated in not only sciatic nerves, but also hind paws, DRG, and spinal nerves, triggering PERK/IRE1α/ATF6 activation as an adaptive response.41, 42, 43 This caused increased eIF2α phosphorylation, ATF4 synthesis, and XBP1 splicing, leading to greater translation of chaperones, redox enzymes, and autophagy proteins.41, 42, 43

CHOP deletion has been shown to protect cells from ER stress by attenuating protein synthesis and modifying redox conditions of ER.74 CHOP deficiency enabled T1DM mice to restore nerve conduction velocities, partially prevent intraepidermal nerve fibre loss, and experience less severe thermal hyperalgesia.43 Studies with ER stress inhibitors further suggest that ER stress can be a pathological driver of T1DM neuropathy. For example, chemical chaperones such as 4-PBA, TMAO, and indole-3-propionic acid (IPA) reversed neuronal ER stress markers, improved survival, functions, and blood supply of peripheral nerves, and alleviated tactile allodynia and thermal/cold hyperalgesia in T1DM rats.41, 42, 43 Soluble epoxide hydroxylase (sEH) inhibitors such as TPAU, TPPU, and TUPS are another class of drug demonstrated to alleviate ER stress and tone down PERK/IRE1α/ATF6 activation.41,75 In T1DM rats, sEH inhibitors attenuated ER stress in paws and sciatic nerves and greatly reduced tactile allodynia and heat hyperalgesia.41,44,75 However, as sEH inhibitors also modulate inflammation, autophagy, and mitochondrial function, their effects might be multifactorial. Consistent with the data above, inducing ER stress was sufficient to trigger peripheral neuropathy in healthy rats. Intraplantar injections of ER stress inducers such as tunicamycin and dimethyl-celecoxib (SERCA inhibitor)76, 77, 78 dose-dependently triggered pain in the ipsilateral hind paw.41 These drugs also caused rats to become more sensitive to tactile stimuli while less sensitive to heat stimuli, just like T1DM rats.41 Interestingly, concurrent treatments with 4-PBA and TPPU reversed ER stress markers and ameliorated mechanical allodynia/hyperalgesia.41

ER stress also contributes to neuropathy in T2DM. Zucker (fa/fa) rats, a pre-diabetes/T2DM model that frequently develops mechanical/thermal hyperalgesia, manifested ER stress in sciatic nerves, as demonstrated by upregulation of BiP and GRP94.45 Oral administration of TMAO decreased ER stress markers in sciatic nerves, improved nerve conduction velocities, and alleviated mechanical/thermal hyperalgesia.45 Similar to Zucker rats, high-fat diet (HFD)-fed T2DM mice models showed upregulation of CHOP, ATF4, and XBP-1s in sciatic nerves and DRG.45,46 The LXR agonist GW3965 decreased expressions of all these ER stress markers and alleviated HFD-induced tactile allodynia and thermal hyperalgesia.46 This suggests that ER stress contributes to neuropathy induced by HFD. Interestingly, HFD-induced T2DM rodent models, unlike other models of diabetic neuropathy, showed decreased rather than increased eIF2α phosphorylation.45,46 In addition, enhancing eIF2α phosphorylation via salubrinal greatly improved nerve conduction velocities and alleviated mechanical/cold/thermal hyperalgesia.45 This suggests that at least in HFD-induced T2DM neuropathy, the PERK branch failed to be activated and augmenting the PERK pathway reduces ER stress and slow down the nerve damage.

Cautions should be made in interpreting beneficial effects of oral ER stress inhibitors on diabetic neuropathy. Systemic administration of ER stress inhibitors may have alleviated hyperalgesia by simply correcting underlying diabetic rather than treating neuropathy per se. However, a few studies suggest that ER stress in peripheral nerves rather than pancreatic β-cells may play more crucial roles in the development of diabetic neuropathy. For example, systemic treatment with 4-PBA, TMAO, and IPA alleviated neuropathy without ameliorating hyperglycaemia.42,43,45 However, for relatively nonspecific ER stress inhibitors, such as sEH inhibitors, results are mixed,44,75 and it is unclear whether their beneficial effects on hyperalgesia arise solely from inhibiting neuronal ER stress. At least, TPAU, one of the sEH inhibitors, alleviated mechanical/heat hyperalgesia without improving glucose tolerance.44 Directly manipulating chaperones or ER stress in only neurones without impacting systemic glycaemia would be the best way to confirm the role of ER stress in diabetic neuropathy. Recently, one study targeted Nav1.8 channel-expressing sensory neurones in DRG and ganglia, which have been shown to mediate nociceptive behaviours in diabetic neuropathy.79, 80, 81 The LXR agonist decreased ER stress and alleviated HFD-induced neuropathy phenotypes.46 Deletion of LXR in Nav1.8-expressing sensory neurones exacerbated HFD-induced ER stress, mechanical allodynia/hyperalgesia without affecting glucose tolerance,46 suggesting that LXR signalling-dependent modulation of ER stress in sensory neurones can mediate diabetic neuropathy.

Similar to diabetic neuropathy, ER stress appears to contribute to vasculitic peripheral neuropathy (VPN) pathogenesis as well. In VPN animal models, PERK was activated in involved nerves, leading to increased eIF2α phosphorylation and elevated synthesis of ATF4 and CHOP.47,48 IRE1α and ATF6 pathways were also activated.47,48 4-PBA significantly reduced all these ER stress markers and ameliorated mechanical/thermal hyperalgesia in VPN animal models.47

Central neuropathic pain induced by multiple sclerosis and stroke

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a CNS demyelinating disease that can trigger debilitating neuropathic pain.82 A recent study suggests that ER stress may play a role in the development of neuropathic pain in MS. In post-mortem DRG tissues from MS patients, BiP and XBP1 were upregulated mainly in sensory neurones.49 Similarly, an experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis mouse model of MS showed BiP/CHOP upregulation, PERK-eIF2 activation, and enhanced XBP1 splicing in DRG.49 XBP1-s was localised to the nucleus of small-diameter neurones, where nociceptors were prominently located. These small-diameter DRG neurones showed excessive Ca2+-induced Ca2+ efflux from the ER. As ER Ca2+ stores are essential for activating ER chaperones, these aberrant Ca2+ dynamics can cause nociceptive neurones to be not only hyperexcitable, but also susceptible to ER stress. 4-PBA and PERK inhibitor alleviated ER stress and restored cytosolic Ca2+ transients in primary dissociated DRG nociceptive neurones, improving mechanical allodynia/hyperalgesia and orofacial hypersensitivity in MS mice.49 Thus, disruption of ER Ca2+ handling and subsequent ER stress in nociceptive neurones can contribute to neuropathic pain in MS.

Central poststroke pain (CPSP) is another type of central neuropathic pain occurring after a cerebrovascular event. The exact mechanism underlying CPSP is still unclear, but the imbalance between excitatory and inhibitory systems in pain pathways after stroke have been postulated to trigger CPSP.83 ER stress may sensitise CNS neurones by augmenting excitatory neurotransmission and disinhibiting GABAergic neurotransmission. For example, inducing ER stress with tunicamycin and thapsigargin enhanced spontaneous excitatory neurotransmission, which was reversed by the ER stress inhibitor salubrinal.84 In addition, under ischemic conditions, neurones upregulated the ER stress marker CHOP, which prevented heterodimerisation and trafficking of GABA receptors to the cell surface, thus diminishing GABA-mediated inhibitory neurotransmission.85 To examine if ER stress indeed plays a role in CPSP, collagenase was injected into the ventral posterior lateral nucleus (VPL) of the thalamus of Sprague–Dawley rats to induce thalamic haemorrhage/lesions. These rats showed mechanical allodynia with thalamic neurones showing swollen ER lumens and high levels of ER stress markers including BiP.50 PERK/IRE1α/ATF6 were activated, leading to increased eIF2α phosphorylation and greater XBP1 splicing. Interestingly, tunicamycin injection to VPL in healthy rats not only increased ER stress markers, but also induced mechanical allodynia. 4-PBA and TPPU dose-dependently reversed ER stress markers, reduced ER dilation in perithalamic lesion sites, and improved mechanical allodynia/hyperalgesia. Beneficial effects of these ER stress inhibitors were abolished after tunicamycin co-injection. These data suggest that ER stress in thalamic areas was sufficient to induce pain and that inhibiting ER stress was necessary for relieving CPSP.

Models of cancer- and chemotherapy-induced pain

About 75–90% of patients with advanced cancer end up experiencing severe bone pain because of tumour metastasis.86, 87, 88 Recent animal studies suggest that ER stress in bone-innervating dorsal horn nerves may play a crucial role in bone cancer pain.51,52 In C3H/HeN mice and Sprague–Dawley rats with bone cancer pain, lumbar spinal dorsal horn showed reactive astrocytosis, increased ER stress markers, and swollen ER cisternae accumulated with protein aggregates. ER stress markers were prominent in GABAergic interneurones and astrocytes but not in microglia. To combat ER stress, all three UPR branches were activated. Intrathecal administration of 4-PBA and TUDCA was able to downregulate ER stress markers, tone down PERK/IRE1α/ATF6 activation, decrease reactive astrocytosis, and attenuate mechanical allodynia/hyperalgesia. However, intrathecal injection of thapsigargin to further increase ER stress exacerbated bone cancer pain. It appears that PERK activation might be crucial for bone cancer pain as intrathecal injection of GSK2606414, selective PERK-eIF2α pathway inhibitor, alone was sufficient to significantly reduce reactive astrocytosis and alleviate mechanical allodynia/hyperalgesia.

For up to ∼70% of cancer patients, antineoplastic agents can cause severe distal sensorimotor neuropathy known as chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy.89,90 In addition to direct neurotoxic effects, vincristine and paclitaxel induced ER stress in sciatic nerves of Sprague–Dawley rats. BiP was upregulated and PERK/IRE1α/ATF6 pathways were activated.53 Overexpressing the chaperone Hsp27, specifically in sensory neurones, prevented mice from developing mechanical/cold allodynia induced by vincristine and paclitaxel. In addition, even after vincristine and paclitaxel treatment, these transgenic mice were protective against degeneration of intraepidermal afferent C-fibres, demyelination, and apoptosis.54,55 These mice also showed restoration of sensory nerve blood flow, Ca2+ influx, action potentials, conduction velocities, and neurite outgrowth. As a result, these mice showed accelerated recovery of sensory and motor functions. This beneficial effect of Hsp27 overexpression might be attributable to alleviation of ER stress, attenuation of UPR overactivation, and subsequent protection against neurotoxicity.91

Other pain models

Peripheral injections of formalin, complete Freund's adjuvant, or heme causes acute inflammation, makes affected neurones hyperexcitable, and triggers mechanical/thermal/cold hyperalgesia.56, 57, 58,62 After administration of these chemicals, lumbar spinal dorsal horn and trigeminal ganglion showed BiP/CHOP upregulation, PERK/IRE1α/ATF6 activation, and disrupted ER morphologies.56, 57, 58,62 Reversing these ER stress markers via 4-PBA or salubrinal restored neuronal activity and attenuated mechanical/thermal hyperalgesia. These treatments also alleviated pain behaviours in sickle cell disease mice by dampening heme-induced ER stress.62

ER stress also appears to play a role in opioid-induced hyperalgesia (OIH) and postherpetic neuralgia (PHN), as demonstrated by BiP upregulation, IRE1α/PERK/ATF6 activation, and swollen ER cisternae in periaqueductal gray and lumbar spinal cords.40,60,61,63,92,93 4-PBA, TUDCA, Hsp70 overexpression, or P2X7 purine receptor antagonists to reduce ER stress improved mechanical/thermal hyperalgesia in OIH/PHN animal models.60,61,63,92,93 These benefits were reversed by the ER stress inducer tunicamycin. Similarly, toning down UPR with IRE1α and ATF6 inhibitors decreased ER stress markers and alleviated hyperalgesia in OIH models.93 These studies suggest that elevated ER stress and UPR overactivation in central nociceptive neurones may contribute to OIH/PHN.

Mechanisms of endoplasmic reticulum stress and pain processing

Inflammation

Inflammatory mechanisms are increasingly recognised as a key player mediating chronic pain. After nerve injury, cytokines are secreted in order to facilitate neurite regeneration and help axons to reinnervate targets.94 However, prolonged elevations in pro-inflammatory cytokines can sensitise nociceptive neurones by increasing expressions of voltage-gated transient receptor potential (TRP) and sodium channels.95 Indeed, interleukin (IL)-1β, IL-6, and tumour necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) increased the excitability of nociceptive neurones in the spinal cord, DRG, and periphery and enhanced pain perception.96, 97, 98 In addition to these short-term changes known as peripheral sensitisation, cytokines can enhance synaptic plasticity of CNS nociceptive neurones and cause long-lasting changes in the way pain signals are processed—referred to as central sensitisation.99,100

ER stress can induce cytokine productions even in the absence of physical injury or infectious stimuli.101 Mechanistically, nucleotide-binding oligomerisation domain-like receptors are implicated in the ER stress-induced inflammation.102 Reducing ER stress with 4-PBA compromised cytokine productions induced by tunicamycin or infectious stimuli such as LPS.103,104 ER stress-driven cytokine productions appear to arise from UPR activation. Inhibiting endonuclease activity of IRE1α markedly decreased productions of IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α in response to tunicamycin or LPS.103,105,106 However, activation of IRE1α-XBP1 signalling was sufficient to drive sterile inductions of IL-6.106,107 Similarly, pharmacologic/genetic inhibition of PERK and ATF6 impaired ER stress-induced productions of pro-inflammatory cytokines and acute phase reactants such as C-reactive protein (CRP).104,108,109 IRE-1α, PERK, and ATF-6 appear to induce cytokine productions mainly by facilitating the nuclear translocation of nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB).101 Alternatively, UPR elements such as XBP-1, ATF4, and CHOP can directly bind to the promoter of IL-6, IL-23, and TNF-α, driving expressions of these cytokines.106,107,110, 111, 112

The study by Chopra and colleagues59 demonstrated that ER stress and UPR activation are responsible for productions of not only cytokines, but also prostaglandins. They also showed that ER stress-induced prostaglandin synthesis is crucial for the pathogenesis of inflammatory pain. They found that XBP1, upon IRE1α activation, binds to the promoter of cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) and prostaglandin E synthase 1 (PGES-1) genes, enabling robust generations of prostaglandins. Indeed, IRE1α- or XBP1-deficient myeloid cells had marked impairments in producing multiple classes of prostaglandins because of downregulations of COX-2 and PGES-1. Interestingly, mice with leukocytes deficient of IRE1α or XBP1 showed significantly less pain behaviours in response to inflammatory visceral pain and postsurgical pain. Further, IRE1α inhibitors KIRA6 and MKC8866 decreased prostaglandin biosynthesis and ameliorated inflammatory pain. This improved pain outcome appears to arise from decreased inflammatory responses triggered by prostaglandins.

These studies implicate that ER stress can trigger chronic pain by enhancing productions of cytokines and prostaglandins and facilitating neuroinflammation. Analgesic benefits of ER stress inhibitors appear to be linked to their ability to counter neuroinflammation. For example, 4-PBA, PERK inhibitor (GSK2606414), and TPPU not only alleviated hyperalgesia, but also dose-dependently reduced TNF/JNK/NF-κB-mediated neuroinflammation, decreased reactive astrocytosis and microglial activation, and downregulated concentrations of IL-1β, IL-6, and prostaglandins.38,47,50,51,56 SERCA activator, which relieved ER stress and hyperalgesia, similarly decreased reactive astrocytosis. However, inducing ER stress and hyperalgesia via tunicamycin increased TNF/JNK-mediated neuroinflammation and triggered reactive astrocytosis. However, whether the inflammation affected by these ER stress modulators is directly responsible for pain phenotypes needs to be further studied. Once ER stress generates pro-inflammatory signals, these can be rapidly amplified via a positive feedback loop as cytokines and inflammation can in turn cause ER stress.113,114 Further, ER stress is transmissible among various cell types in different tissues by generating bioactive lipids and modifying extracellular environment.115, 116, 117 Thus, the systemic interplay among neurones, astrocytes, microglia, etc. can cell-non-autonomously propagate ER stress-driven neuroinflammation and cause chronic pain.

Ion channel dysregulation, aberrant Ca2+ handling, and synaptic disinhibition

Activities of ion channels on nociceptive neurones determine how pain signals are transmitted and processed.118 Dysregulated expressions of ion channels can make nociceptive fibres hyperexcitable and increasingly secrete substance P and calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP), leading to hyperalgesia and allodynia. Altered ion concentrations can also potentiate the current through ion channels, further contributing to neuronal hyperexcitability and heightened pain perception. Tightly regulating intracellular Ca2+ is particularly important in that high levels of this cation can depolarise nociceptive neurones, cause the release of synaptic vesicles, and trigger pain pathogenesis.119, 120, 121, 122, 123 Ca2+-induced Ca2+-release (CICR) from ER is the process that amplifies Ca2+ signals; it is critical to keep this positive feedback loop in check to prevent neurones from becoming hyperexcitable.124,125 During CICR, Ca2+ influx through voltage-gated Ca2+ channels (VGCCs) triggers the opening of ER ryanodine receptors (RyRs), leading to the Ca2+ efflux from ER. This released Ca2+ then activates nearby VGCCs, resulting in a self-amplifying Ca2+ signalling cascade. ER inositol triphosphate receptors (IP3R), activated by Ca2+ and IP3, can further contribute to the CICR from ER. SERCA terminates this positive feedback loop by actively sequestering Ca2+ from cytosol to ER.

Emerging evidence suggests that ER stress can increase the excitability of nociceptive neurones via aberrant CICR and altered functions of Ca2+-sensitive K+ channels. Animal models of neuropathy showed enhanced CICR from ER and elevated cytosolic Ca2+ transients, causing nociceptive neurones to be hyperexcitable.38,49,55 Reducing ER stress with 4-PBA, PERK inhibitors, or chaperone overexpressions dampened Ca2+ currents in small-diameter pain fibers.38,49,55 However, ER stress inducers tunicamycin and thapsigargin augmented CICR and Ca2+ transients, increased spiking frequency, enhanced spontaneous excitatory transmission, leading to neuronal hyperexcitability and hyperalgesia.37,38,84,126 ER stress appears to enhance CICR via CHOP-induced ER oxidoreductase1α (ERO1α), which activates RyR and IP3R while inactivating SERCA.127, 128, 129 As diminished SERCA activity can in turn trigger ER stress via ER Ca2+ depletion, this positive feedback loop can exponentially augment CICR. In support of this, inhibiting the activity of CHOP, ERO1α, RyR, or IP3R blunted ER stress-induced CICR.128, 129, 130, 131 However, overexpression of ERO1α potentiated tunicamycin-induced CICR. In addition to enhancing CICR, ER stress can make neurones hyperexcitable by altering functions of Ca2+-sensitive BK-type K+ channels. In mice models of MS neuropathy, the conductance–voltage curve for BK channels was shifted to a more positive voltage in IB4-positive nociceptive DRG neurones.49 This alteration in voltage-dependent gating of BK channels caused small-diameter nociceptive neurones to show reduced after-hyperpolarisation and more depolarised resting potentials. Interestingly, reducing ER stress with 4-PBA and PERK inhibitors restored BK channel physiology, prevented neuronal hyperexcitability, and alleviated neuropathy. It appears that PERK activation during ER stress downregulates the auxiliary β4 subunit of BK channels (Kcnmb4), making them dysfunctional.

ER stress can also sensitise spinal dorsal horn neurones by impairing activities of GABAergic interneurones. GABAergic interneurones, by inhibiting excitatory nociceptive neurones, act as a brake on pain signals that are transmitted from the periphery to the CNS.132 This gating mechanism is important for preventing excessive pain signalling and maintaining normal pain sensitivity. In a mouse model of cancer pain, ER stress was observed predominantly in GABAergic interneurones in the spinal dorsal horn.51 Inducing ER stress in spinal dorsal horn neurones robustly suppressed the amplitude and frequency of GABA receptor-mediated inhibitory postsynaptic currents, leading to mechanical hyperalgesia.34 ER stress appears to impair GABA-mediated currents by compromising the synthesis, chemical modification/maturation, and trafficking of GABA receptors.133, 134, 135, 136 However, inducing UPR via ATF6 overexpression promoted membrane insertions of α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid (AMPA) receptors responsible for excitatory transmission.137 Similarly, inducing ER stress with tunicamycin and thapsigargin enhanced glutamate-mediated spontaneous excitatory transmission by four-fold.84 ER stress may thus hypersensitise nociceptive neurones by disturbing the glutamate/GABA balance.

Mitochondrial dysfunction and reactive oxygen species generation

Mitochondrial dysfunction has been strongly implicated in neuropathic pain.138,139 Impaired mitochondrial bioenergetics can induce hyperalgesia by making sensory neurones hyperexcitable.140, 141, 142 Excessive reactive oxygen species (ROS) productions from mitochondrial damage can trigger neuropathic pain by activating TRP channels, upregulating N-methyl-d-aspartate (NMDA) receptors, enhancing plasticity at excitatory synapses, inhibiting GABAergic gating mechanisms, mounting pro-inflammatory responses via NLRP3 inflammasomes, and causing oxidative neuronal damages.143, 144, 145, 146, 147, 148, 149, 150, 151, 152, 153 Further, failure of mitochondria to buffer intracellular Ca2+ can increase excitability of nociceptors, cause neuronal apoptosis, and contribute to neuropathic pain.120

ER stress can cause mitochondrial dysfunction via increased IP3R-mediated transport of Ca2+ into mitochondria.120,154 IP3R of ER is tethered to the voltage-dependent anion channel (VDAC) of mitochondria by the chaperone GRP75.155 ER stress strengthens membranous associations with mitochondria and causes increased Ca2+ transfer from ER to mitochondria via the IP3R-GRP75-VDAC complex.156 Non-canonical functions of PERK/IRE1α/ATF6 help strengthen ER-mitochondrial contacts and facilitate Ca2+ transfer via IP3R activation.120,157, 158, 159 This increased ER-mitochondria Ca2+ coupling can initially improve bioenergetics and provide cells energy sources to counteract against ER stress.156 However, prolonged Ca2+ transfer causes mitochondrial Ca2+ overload, which ultimately impairs mitochondrial bioenergetics and triggers ROS buildup, NLRP3 inflammasome formation, and apoptosis.155,157 Blocking activation of PERK and IRE1α at ER-mitochondrial junctions weakened the Ca2+ coupling and reduced apoptosis.160,161 As mentioned earlier, overactive CICR from ER stress can further elevate cytosolic Ca2+ levels and contribute to mitochondrial Ca2+ overload.

Although the mitochondrion is the primary ROS-inducing organelle, ER stress and PDI/ERO1-mediated oxidative folding can generate large quantities of ROS. In fact, ER lumen contains more ROS than mitochondria and 25% of ROS are generated via PDI/ERO1-mediated disulfide bond formation.162,163 PDI forms disulfide bonds and promotes folding by accepting electrons from free thiols in nascent peptides.163 ERO1 then re-oxidises reduced PDI by transferring electrons from PDI to O2 to form H2O2, which can generate ROS. Thus, under high protein load during ER stress, more proteins would undergo PDI/ERO1-mediated oxidative folding and a greater amount of ROS could be generated. Indeed, pharmacological and genetic ERO1 inhibition dampened ER stress-induced ROS productions, whereas ERO1 overexpression enhanced ROS productions.74,164, 165, 166, 167 4-PBA and TUDCA to reduce the load of misfolded proteins decreased ROS productions.62,168 Antinociceptive benefits of ER stress inhibitors and chaperone overexpressions were associated with decreased ROS productions and restoration of mitochondrial morphologies, function, membrane potentials, and fusion–fission dynamics.42,54,55,62 Collectively, these studies suggest that ER stress can contribute to neuropathic pain by causing mitochondrial dysfunction and excessive ROS productions.

Apoptosis

Apoptosis in response to nerve injury has been implicated in the development of neuropathic pain.5,169 Pharmacologically and genetically inhibiting caspases to block apoptosis prevented the loss of GABAergic interneurones, toned down excitatory neurotransmission, and attenuated neuropathic pain after nerve injury.170, 171, 172 However, intrathecal injection of caspases enhanced excitatory synaptic transmission and induced hyperalgesia.172 ER stress and UPR activation can trigger apoptosis.173 PERK-mediated eIF2α phosphorylation selectively upregulates translation of ATF4, which drives CHOP transcription. CHOP can trigger apoptosis by downregulating anti-apoptotic factors (e.g. Bcl2) while upregulating pro-apoptotic factors such as BIM, BAK, TRAIL receptor, and death receptors 4/5. Prolonged IRE1α signalling also activates apoptosis signal regulating kinase 1, which can trigger apoptosis via JNK-mediated activation of BAK. IRE1α can also form a complex with TNF-associated factor 2 (TRAF2), which interacts with procaspase-12 and promotes its cleavage for activation. Further, aberrant CICR and excessive ROS generation during ER stress can cause apoptosis by enhancing cytosolic Ca2+ transients and causing cytochrome c release, respectively. Animal studies indirectly suggest that ER stress may trigger hyperalgesia by inducing apoptosis. For example, after peripheral nerve injuries, IB4-positive nociceptive neurones activated PERK and upregulated caspase 12, which specifically mediates ER stress-induced apoptosis.174,175 In addition, antinociceptive benefits of 4-PBA, TUDCA, and Hsp27 were associated with decreased apoptosis of neurones and oligodendrocytes, lesser loss of intraepidermal nerve fibres, attenuated demyelination, reduced DNA fragmentation, and downregulation of caspase 3 and 12.52,54,55,176,177 However, ER stress inducers that caused hyperalgesia upregulated caspase 3 and enhanced neuronal apoptosis.52 In order to investigate causal relationships between ER stress-mediated apoptosis and chronic pain, more direct pain studies with concurrent manipulations of ER stress, caspase 12, and other apoptotic mediators are needed.

Concluding remarks: therapeutic implications, limitations, and future studies

Multiple studies have shown that ER stress and subsequent UPR activation can contribute to the pathogenesis of chronic pain. ER stress can make nociceptive neurones hyperexcitable and enhance pain perception via both inflammatory and non-inflammatory mechanisms. ER stress can cause misregulation of multiple molecular cascades, including pro-inflammatory responses, ion channel functions, Ca2+ handling, ROS generation, mitochondrial functions, and apoptosis. The synergistic crosstalk between these disrupted pathways can cause exponential progression of pathologies and induce hyperalgesia. ER stress was evident in peripheral and central neurones under various types of pain. Several ER stress inhibitors and UPR inhibitors improved pain outcome by restoring multiple molecular cascades in parallel. However, inducing ER stress with various pharmacological agents was sufficient to trigger hyperalgesia in wild-type animals.

Most current pain regimens aim to abate inflammation and pain processing. However, NSAIDs or steroids would be effective only if the aetiology of pain is predominantly the overactive pro-inflammatory response. Opioids can effectively weaken pain signals but they can mask underlying causes of hyperactive nociceptive neurotransmission. ER stress appears to be a central hub for multiple molecular cascades involved in the pathogenesis of chronic pain. Reducing ER stress can thus tackle both inflammatory and non-inflammatory causes of pain. In addition, by correcting dysfunction in not just the single pathway, but multiple pathways in parallel, ER stress inhibition can be an attractive therapeutic option for chronic pain resistant to NSAIDs, steroids, or opioids.

Targeting ER stress per se, rather than UPR overactivation, appears to be a better therapeutic strategy against chronic pain. For multiple chronic disorders, including chronic pain, eliminating the source of ER stress via chemical chaperones had the most promising results. Especially, 4-PBA and TUDCA have been consistently shown to improve pain outcome in multiple pain models. However, UPR inhibitors such as PERK/IRE1α inhibitors or ISRIBs (integrated stress response inhibitors) had mixed outcomes. UPR overactivation can lead to hyperalgesia by triggering pro-inflammatory responses, oxidative stress, and apoptosis. Yet, as UPR is activated in order to counteract ER stress, blocking UPR activation too much may completely impair adaptive responses and actually worsen ER stress. For example, UPR activation, in response to ER stress, decreases global protein translation to alleviate the protein folding load. It also increases autophagy to clear up misfolded proteins. However, excessive UPR inhibition can block these adaptive changes and cause the buildup of misfolded proteins, potentially worsening pain pathologies. Indeed, multiple studies have shown that reducing cap-dependent protein translation and enhancing autophagy were critical to improving pain outcome in various models.178, 179, 180, 181, 182, 183, 184 Thus, balancing the optimal level of UPR activation—sustaining enough UPR to clear out misfolded proteins and yet preventing chronic UPR overactivation— appears to be critical.

For all the reasons discussed above, 4-PBA and TUDCA appear to be the most promising therapeutic strategy against chronic pain. Unlike in other chronic diseases, these two drugs have not been tested in humans yet for chronic pain despite numerous preclinical studies supporting the efficacy. It will be exciting to test whether these drugs can alleviate symptoms in patients with chronic pain resistant to traditional treatments such as NSAIDs, steroids, or opioids. Fortunately, for 4-PBA and TUDCA, the barrier to clinical trials is minimal in that the safety of these drugs has already been clinically tested in multiple other disorders. Moreover, these drugs have been FDA-approved for other disorders, so repurposing these drugs for analgesic use may permit the acceleration into phase II trials. Although the pain outcome of UPR inhibitors is somewhat mixed, PERK modulators have been chemically modified and titrated to limit pancreatic toxicity and maintain the optimal degree of UPR inhibition.185 Indeed, ISRIB has been shown to cause neuroprotection without pancreatic toxicity as it does not totally inhibit UPR.186 Additionally, besides side-effects affecting organ functions, addiction potential has not been systematically examined for ER stress modulators. This warrants further exploration towards effective and safe pain treatment.

Authors’ contributions

Wrote the draft and revised the manuscript: all authors

Declaration of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Funding

SS is supported by NIH R35GM128692, R61NS116423, R01 AG 070141, R03 AG067947, R61 NS126029, and NSF EAGER 2334666.

Handling Editor: Nadine Attal

References

- 1.Finnerup N.B., Kuner R., Jensen T.S. Neuropathic pain: from mechanisms to treatment. Physiol Rev. 2021;101:259–301. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00045.2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fornasari D. Pain mechanisms in patients with chronic pain. Clin Drug Investig. 2012;32(Suppl 1):45–52. doi: 10.2165/11630070-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Busse J.W., Wang L., Kamaleldin M., et al. Opioids for chronic noncancer pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2018;320:2448–2460. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.18472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Enthoven W.T., Roelofs P.D., Deyo R.A., van Tulder M.W., Koes B.W. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for chronic low back pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;2:CD012087. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD012087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liao M.F., Lu K.T., Hsu J.L., Lee C.H., Cheng M.Y., Ro L.S. The role of autophagy and apoptosis in neuropathic pain formation. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23:2685. doi: 10.3390/ijms23052685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Parisien M., Lima L.V., Dagostino C., et al. Acute inflammatory response via neutrophil activation protects against the development of chronic pain. Sci Transl Med. 2022;14 doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.abj9954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lee M., Silverman S.M., Hansen H., Patel V.B., Manchikanti L. A comprehensive review of opioid-induced hyperalgesia. Pain Physician. 2011;14:145–161. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Araki K., Nagata K. Protein folding and quality control in the ER. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2011;3:a007526. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a007526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ellgaard L., Helenius A. Quality control in the endoplasmic reticulum. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2003;4:181–191. doi: 10.1038/nrm1052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Walter P., Ron D. The unfolded protein response: from stress pathway to homeostatic regulation. Science. 2011;334:1081–1086. doi: 10.1126/science.1209038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hetz C., Zhang K., Kaufman R.J. Mechanisms, regulation and functions of the unfolded protein response. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2020;21:421–438. doi: 10.1038/s41580-020-0250-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lindholm D., Wootz H., Korhonen L. ER stress and neurodegenerative diseases. Cell Death Differ. 2006;13:385–392. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hetz C., Saxena S. ER stress and the unfolded protein response in neurodegeneration. Nat Rev Neurol. 2017;13:477–491. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2017.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Eizirik D.L., Cardozo A.K., Cnop M. The role for endoplasmic reticulum stress in diabetes mellitus. Endocr Rev. 2008;29:42–61. doi: 10.1210/er.2007-0015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cnop M., Foufelle F., Velloso L.A. Endoplasmic reticulum stress, obesity and diabetes. Trends Mol Med. 2012;18:59–68. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2011.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cubillos-Ruiz J.R., Bettigole S.E., Glimcher L.H. Tumorigenic and immunosuppressive effects of endoplasmic reticulum stress in cancer. Cell. 2017;168:692–706. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Paganoni S., Macklin E.A., Hendrix S., et al. Trial of sodium phenylbutyrate-taurursodiol for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:919–930. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1916945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pilon M., Schekman R., Romisch K. Sec61p mediates export of a misfolded secretory protein from the endoplasmic reticulum to the cytosol for degradation. EMBO J. 1997;16:4540–4548. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.15.4540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hwang J., Qi L. Quality control in the endoplasmic reticulum: crosstalk between ERAD and UPR pathways. Trends Biochem Sci. 2018;43:593–605. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2018.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Oikawa D., Tokuda M., Hosoda A., Iwawaki T. Identification of a consensus element recognized and cleaved by IRE1 alpha. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:6265–6273. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chen Y., Brandizzi F. IRE1: ER stress sensor and cell fate executor. Trends Cell Biol. 2013;23:547–555. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2013.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ron D. Translational control in the endoplasmic reticulum stress response. J Clin Invest. 2002;110:1383–1388. doi: 10.1172/JCI16784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wek R.C. Role of eIF2alpha kinases in translational control and adaptation to cellular stress. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2018;10:a032870. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a032870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vattem K.M., Wek R.C. Reinitiation involving upstream ORFs regulates ATF4 mRNA translation in mammalian cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:11269–11274. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0400541101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rozpedek W., Pytel D., Mucha B., Leszczynska H., Diehl J.A., Majsterek I. The role of the PERK/eIF2alpha/ATF4/CHOP signaling pathway in tumor progression during endoplasmic reticulum stress. Curr Mol Med. 2016;16:533–544. doi: 10.2174/1566524016666160523143937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Adams C.J., Kopp M.C., Larburu N., Nowak P.R., Ali M.M.U. Structure and molecular mechanism of ER stress signaling by the unfolded protein response signal activator IRE1. Front Mol Biosci. 2019;6:11. doi: 10.3389/fmolb.2019.00011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hetz C., Martinon F., Rodriguez D., Glimcher L.H. The unfolded protein response: integrating stress signals through the stress sensor IRE1alpha. Physiol Rev. 2011;91:1219–1243. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00001.2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ulland T.K., Song W.M., Huang S.C., et al. TREM2 maintains microglial metabolic fitness in Alzheimer’s disease. Cell. 2017;170:649–663.e13. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.07.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Oyadomari S., Yun C., Fisher E.A., et al. Cotranslocational degradation protects the stressed endoplasmic reticulum from protein overload. Cell. 2006;126:727–739. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.06.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shan B., Wang X., Wu Y., et al. The metabolic ER stress sensor IRE1alpha suppresses alternative activation of macrophages and impairs energy expenditure in obesity. Nat Immunol. 2017;18:519–529. doi: 10.1038/ni.3709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li W., Yang J., Luo L., et al. Targeting photodynamic and photothermal therapy to the endoplasmic reticulum enhances immunogenic cancer cell death. Nat Commun. 2019;10:3349. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-11269-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dalla Bella E., Bersano E., Antonini G., et al. The unfolded protein response in amyotrophic later sclerosis: results of a phase 2 trial. Brain. 2021;144:2635–2647. doi: 10.1093/brain/awab167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhang E., Yi M.H., Shin N., et al. Endoplasmic reticulum stress impairment in the spinal dorsal horn of a neuropathic pain model. Sci Rep. 2015;5 doi: 10.1038/srep11555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ge Y., Jiao Y., Li P., et al. Coregulation of endoplasmic reticulum stress and oxidative stress in neuropathic pain and disinhibition of the spinal nociceptive circuitry. Pain. 2018;159:894–906. doi: 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000001161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Liu Y., Wang S., Wang Z., et al. Dexmedetomidine alleviated endoplasmic reticulum stress via inducing ER-phagy in the spinal cord of neuropathic pain model. Front Neurosci. 2020;14:90. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2020.00090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Liu Y., Kuai S., Ding M., Wang Z., Zhao L., Zhao P. Dexmedetomidine and ketamine attenuated neuropathic pain related behaviors via STING pathway to induce ER-phagy. Front Synaptic Neurosci. 2022;14 doi: 10.3389/fnsyn.2022.891803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yamaguchi Y., Oh-Hashi K., Matsuoka Y., et al. Endoplasmic reticulum stress in the dorsal root ganglion contributes to the development of pain hypersensitivity after nerve injury. Neuroscience. 2018;394:288–299. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2018.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Li S., Zhao F., Tang Q., et al. Sarco/endoplasmic reticulum Ca(2+) -ATPase (SERCA2b) mediates oxidation-induced endoplasmic reticulum stress to regulate neuropathic pain. Br J Pharmacol. 2022;179:2016–2036. doi: 10.1111/bph.15744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gui Y., Li A., Zhang J., et al. α-Asarone alleviated chronic constriction injury-induced neuropathic pain through inhibition of spinal endoplasmic reticulum stress in an liver X receptor-dependent manner. Anesth Analg. 2018;127:775–783. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000002792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yang Z., Wang C., Zhang X., et al. Stem cells from human exfoliated deciduous teeth attenuate trigeminal neuralgia in rats by inhibiting endoplasmic reticulum stress. Korean J Pain. 2022;35:383–390. doi: 10.3344/kjp.2022.35.4.383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Inceoglu B., Bettaieb A., Trindade da Silva C.A., Lee K.S., Haj F.G., Hammock B.D. Endoplasmic reticulum stress in the peripheral nervous system is a significant driver of neuropathic pain. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112:9082–9097. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1510137112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gundu C., Arruri V.K., Sherkhane B., Khatri D.K., Singh S.B. Indole-3-propionic acid attenuates high glucose induced ER stress response and augments mitochondrial function by modulating PERK-IRE1-ATF4-CHOP signalling in experimental diabetic neuropathy. Arch Physiol Biochem. 2022:1–14. doi: 10.1080/13813455.2021.2024577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lupachyk S., Watcho P., Stavniichuk R., Shevalye H., Obrosova I.G. Endoplasmic reticulum stress plays a key role in the pathogenesis of diabetic peripheral neuropathy. Diabetes. 2013;62:944–952. doi: 10.2337/db12-0716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Inceoglu B., Wagner K.M., Yang J., et al. Acute augmentation of epoxygenated fatty acid levels rapidly reduces pain-related behavior in a rat model of type I diabetes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:11390–11395. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1208708109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lupachyk S., Watcho P., Obrosov A.A., Stavniichuk R., Obrosova I.G. Endoplasmic reticulum stress contributes to pre diabetic peripheral neuropathy. Exp Neurol. 2013;247:342–348. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2012.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gavini C.K., Bookout A.L., Bonomo R., Gautron L., Lee S., Mansuy-Aubert V. Liver X receptors protect dorsal root ganglia from obesity-induced endoplasmic reticulum stress and mechanical allodynia. Cell Rep. 2018;25:271–277.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2018.09.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chen C.H., Shih P.C., Lin H.Y., et al. 4-Phenylbutyric acid protects against vasculitic peripheral neuropathy induced by ischaemia-reperfusion through attenuating endoplasmic reticulum stress. Inflammopharmacology. 2019;27:713–722. doi: 10.1007/s10787-019-00604-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pan P.T., Lin H.Y., Chuang C.W., et al. Resveratrol alleviates nuclear factor-kappaB-mediated neuroinflammation in vasculitic peripheral neuropathy induced by ischaemia-reperfusion via suppressing endoplasmic reticulum stress. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2019;46:770–779. doi: 10.1111/1440-1681.13105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yousuf M.S., Samtleben S., Lamothe S.M., et al. Endoplasmic reticulum stress in the dorsal root ganglia regulates large-conductance potassium channels and contributes to pain in a model of multiple sclerosis. FASEB J. 2020;34:12577–12598. doi: 10.1096/fj.202001163R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Liu T., Li T., Chen X., et al. EETs/sEHi alleviates nociception by blocking the crosslink between endoplasmic reticulum stress and neuroinflammation in a central poststroke pain model. J Neuroinflammation. 2021;18:211. doi: 10.1186/s12974-021-02255-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mao Y., Wang C., Tian X., et al. Endoplasmic reticulum stress contributes to nociception via neuroinflammation in a murine bone cancer pain model. Anesthesiology. 2020;132:357–372. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0000000000003078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.He Q., Wang T., Ni H., et al. Endoplasmic reticulum stress promoting caspase signaling pathway-dependent apoptosis contributes to bone cancer pain in the spinal dorsal horn. Mol Pain. 2019;15 doi: 10.1177/1744806919876150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yardim A., Kandemir F.M., Ozdemir S., et al. Quercetin provides protection against the peripheral nerve damage caused by vincristine in rats by suppressing caspase 3, NF-kappaB, ATF-6 pathways and activating Nrf2, Akt pathways. Neurotoxicology. 2020;81:137–146. doi: 10.1016/j.neuro.2020.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Chine V.B., Au N.P.B., Kumar G., Ma C.H.E. Targeting axon integrity to prevent chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy. Mol Neurobiol. 2019;56:3244–3259. doi: 10.1007/s12035-018-1301-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chine V.B., Au N.P.B., Ma C.H.E. Therapeutic benefits of maintaining mitochondrial integrity and calcium homeostasis by forced expression of Hsp27 in chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy. Neurobiol Dis. 2019;130 doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2019.104492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zhou F., Zhang W., Zhou J., et al. Involvement of endoplasmic reticulum stress in formalin-induced pain is attenuated by 4-phenylbutyric acid. J Pain Res. 2017;10:653–662. doi: 10.2147/JPR.S125805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Takeda M., Tanimoto T., Kadoi J., et al. Enhanced excitability of nociceptive trigeminal ganglion neurons by satellite glial cytokine following peripheral inflammation. Pain. 2007;129:155–166. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2006.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Yang E.S., Bae J.Y., Kim T.H., Kim Y.S., Suk K., Bae Y.C. Involvement of endoplasmic reticulum stress response in orofacial inflammatory pain. Exp Neurobiol. 2014;23:372–380. doi: 10.5607/en.2014.23.4.372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Chopra S., Giovanelli P., Alvarado-Vazquez P.A., et al. IRE1alpha-XBP1 signaling in leukocytes controls prostaglandin biosynthesis and pain. Science. 2019;365:eaau6499. doi: 10.1126/science.aau6499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Celerier E., Laulin J.P., Corcuff J.B., Le Moal M., Simonnet G. Progressive enhancement of delayed hyperalgesia induced by repeated heroin administration: a sensitization process. J Neurosci. 2001;21:4074–4080. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-11-04074.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Okuyama Y., Jin H., Kokubun H., Aoe T. Pharmacological chaperones attenuate the development of opioid tolerance. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21:7536. doi: 10.3390/ijms21207536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lei J., Paul J., Wang Y., et al. Heme causes pain in sickle mice via toll-like receptor 4-mediated reactive oxygen species- and endoplasmic reticulum stress-induced glial activation. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2021;34:279–293. doi: 10.1089/ars.2019.7913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Zhu Y., Zhang S., Wu Y., Wang J. P2X7 receptor antagonist BBG inhibits endoplasmic reticulum stress and pyroptosis to alleviate postherpetic neuralgia. Mol Cell Biochem. 2021;476:3461–3468. doi: 10.1007/s11010-021-04169-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ho Kim S., Mo Chung J. An experimental model for peripheral neuropathy produced by segmental spinal nerve ligation in the rat. Pain. 1992;50:355–363. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(92)90041-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]