Abstract

Background

Identifying the association between body mass index (BMI) or weight change and cancer prognosis is essential for the development of effective cancer treatments. We aimed to assess the strength and validity of the evidence of the association between BMI or weight change and cancer prognosis by a systematic evaluation and meta-analysis of relevant cohort studies.

Methods

We systematically searched the PubMed, Web of Science, EconLit, Embase, Food Sciences and Technology Abstracts, PsycINFO, and Cochrane databases for literature published up to July 2023. Inclusion criteria were cohort studies with BMI or weight change as an exposure factor, cancer as a diagnostic outcome, and data type as an unadjusted hazard ratio (HR) or headcount ratio. Random- or fixed-effects models were used to calculate the pooled HR along with the 95% confidence interval (CI).

Results

Seventy-three cohort studies were included in the meta-analysis. Compared with normal weight, overweight or obesity was a risk factor for overall survival (OS) in patients with breast cancer (HR 1.37, 95% CI 1.22-1.53; P < 0.0001), while obesity was a protective factor for OS in patients with gastrointestinal tumors (HR 0.67, 95% CI 0.56-0.80; P < 0.0001) and lung cancer (HR 0.67, 95% CI 0.48-0.92; P = 0.01) compared with patients without obesity. Compared with normal weight, underweight was a risk factor for OS in patients with breast cancer (HR 1.15, 95% CI 0.98-1.35; P = 0.08), gastrointestinal tumors (HR 1.54, 95% CI 1.32-1.80; P < 0.0001), and lung cancer (HR 1.28, 95% CI 1.22-1.35; P < 0.0001). Compared with nonweight change, weight loss was a risk factor for OS in patients with gastrointestinal cancer.

Conclusions

Based on the results of the meta-analysis, we concluded that BMI, weight change, and tumor prognosis were significantly correlated. These findings may provide a more reliable argument for the development of more effective oncology treatment protocols.

Key words: cancer, body mass index (BMI), obesity, weight change, survival, meta-analysis

Highlights

-

•

This meta-analysis examined how BMI and weight change affect the prognosis of patients with cancer.

-

•

The relationship between obesity and cancer OS varied by cancer type.

-

•

Our findings suggested that compared with normal weight, underweight was a risk factor for OS in almost all specific cancers.

-

•

In terms of weight change, we found that any degree of weight loss was a risk factor for OS in patients with cancer.

Introduction

Cancer is a complex disease.1,2 In recent years, the global incidence and mortality rates of cancers have been increasing.3 Cancer is a serious threat to human life and social development. Many recent studies discuss the risk factors for tumor development, such as aging,4 dietary habits,5,6 lifestyle,5 smoking,7 alcohol consumption,8 and environmental physical factors.9 In addition, studies have found that obesity or underweight is associated with cancer survival.10, 11, 12 A key link between obesity and tumors is increased chronic inflammation and changes in the immune cell population.13

However, according to some recent meta-analyses on body mass index (BMI) and tumor prognosis, a possible relationship between BMI or weight change and tumor prognosis can be found. For example, a study by Li et al.14 found that patients with colorectal cancer (CRC) with higher BMI appeared to have a lower mortality rate than patients with normal weight with CRC. By contrast, Jaspan et al.15 found that obesity and underweight were associated with increased specificity and overall mortality in patients with CRC. However, Parkin et al.16 concluded that there was insufficient evidence of a strong association between obesity and survival in patients with CRC. In addition, Gupta et al.17 and Wang et al.18 concluded that patients with lung cancer with higher BMI had longer survival than those with lower BMI and significantly lower lung cancer-related mortality than participants with normal BMI, while Shukla et al.19 concluded that there was no significant difference in overall survival (OS) or progression-free survival between the obese and nonobese groups. Similarly, in tumors such as breast cancer, endometrial cancer, and gastric cancer, some studies have shown that overweight and obesity are risk factors for patient prognosis, whereas other studies,20, 21, 22 note that overweight and obesity have no relationship with tumor prognosis.23, 24, 25 Therefore the relationship between BMI and tumor prognosis remains highly controversial.

In addition, weight change is an important prognostic factor for patients with tumors. Recently, weight loss was determined to be a poor prognostic factor for a variety of tumors. For example, weight loss was an independent risk factor for poor prognosis in colon cancer.26 Weight loss before chemotherapy for advanced lung cancer was a prognostic factor affecting the OS of patients with advanced lung cancer.27 Weight gain also has an impact on tumor recurrence and OS. Studies have shown that the rate of cancer recurrence and metastasis in patients with breast cancer was strongly associated with weight gain, with patients with overweight or obesity having a higher rate of recurrence and metastasis than those of normal weight, increasing with BMI.28 The all-cause mortality rate was higher in patients with increased BMI after breast cancer diagnosis than in those who maintained their weight. In particular, weight gain of ≥10% had a more pronounced effect on all-cause mortality in patients with breast cancer.29,30

In cohort studies, the investigators personally observe and collect exposure data from study participants before the outcome occurs. As a result, these data are considered reliable and recall bias is relatively low. In addition, the etiological hypothesis can be better tested because the etiology occurs before the onset of the disease, and the recall bias is relatively low. It is also possible to directly calculate the various measurements. This gives cohort studies a strong ability to confirm etiological links.

Therefore we pooled relevant cohort studies for meta-analysis; comprehensively retrieved and extracted available data; classified different tumor patients into underweight, normal weight, overweight, and obese groups according to BMI values; and analyzed them according to different tumor types. In addition, weight change was categorized into weight loss, nonweight change, and weight gain for discussion. We hope that a more comprehensive analysis and discussion will lead to more reliable conclusions.

Materials and methods

Data sources and search

The PubMed, Web of Science, EconLit, Embase, Food Sciences and Technology Abstracts, PsycINFO, and Cochrane databases were searched for literature published by July 2023. The keywords searched were survival, outcome, prognosis, cancer, carcinoma, weight, overweight, and obesity.

Study selection

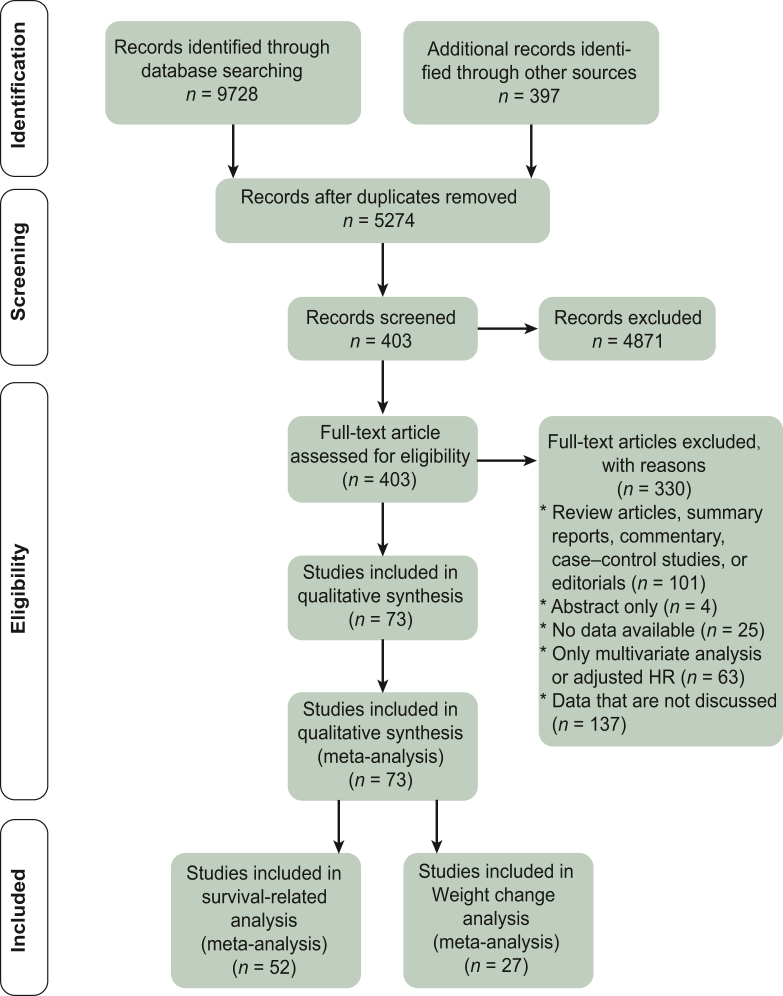

Team members checked all retrieved studies for eligibility. Studies were included in this meta-analysis if they met the following criteria: (i) cohort study, (ii) cancer in the included population, (iii) outcome of death, (iv) BMI or weight change included in the exposure factor, and (v) reported unadjusted or available hazard ratio (HR) value for the univariate analysis (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flowchart of study selection.

Abbreviation: HR, hazard ratio.

Studies were excluded mainly because (i) full text was not available, (ii) data were not available, or (iii) data with BMI-related analyses could not be extracted.

Data extraction

The team members extracted study characteristics from the literature, including tumor type, baseline population characteristics and numbers, BMI and weight change classification criteria, overall data related to prognosis, and subgroup data. Early stage or advanced stage of tumor was defined according to the corresponding literature. For BMI-related data, studies with only progression-free survival, disease-free survival, relapse-free survival, cancer-specific survival, disease-specific survival, survival time, and number of deaths were excluded. Studies with HR data for OS were retained. In addition, some studies with multiple data points were included. Studies were included if both premenopausal and postmenopausal treatment prognosis and HR data were discussed. If prediagnostic and postdiagnostic HR data were available, we used the prediagnostic HR data for the analysis. For weight change-related data, studies with HR data for OS and mortality data with events and total numbers in the exposed and non-exposed groups as initial data were retained.

Exposure definition

BMI was calculated using the formula weight (kg)/height2 (m2). The common classifications were based on the World Health Organization (WHO) categories: underweight (BMI <18.5 kg/m2), normal weight (18.5 kg/m2 ≤ BMI ≤24.9 kg/m2), overweight (25.0 kg/m2 ≤ BMI ≤29.9 kg/m2), and obese (BMI ≥30 kg/m2). According to the WHO definition of Asia-specific values, patients were classified into four BMI categories: underweight (BMI <18.5 kg/m2), normal weight (18.5 kg/m2 ≤ BMI ≤22.9 kg/m2), overweight (23.0 kg/m2 ≤ BMI ≤24.9 kg/m2), and obese (BMI ≥25 kg/m2).31 We divided BMI intervals according to those defined in the original literature. If the study used only one cut-off value to classify the BMI range, we defined the BMI range below this cut-off value as ‘nonobese’ and the BMI range above this cut-off value as ‘obese’. Where studies defined a normal weight BMI range, we defined those above this range as ‘overweight’ and those below as ‘underweight’. For the classification of weight change, we grouped the included studies according to their data on weight gain and weight loss and classified them as any degree of weight gain (where the exposed group experienced weight gain as defined in the included literature), weight gain >5%, any degree of weight loss (where the exposed group experienced weight loss as defined in the included literature), weight loss >5%, and weight loss >10%. Weight invariance was defined as weight gain or loss not greater than the threshold set by each subgroup.

Risk-of-bias assessment

The quality of the included studies was assessed by the Newcastle‒Ottawa Scale (NOS).32 As a validated tool for assessing the quality of nonrandomized trials, the NOS has a maximum score of 9 for each cohort study: 4 for cohort selection (exposure cohort is representative, non-exposure cohort is from the same population as the exposure cohort, exposure factors are determined in a rigorous manner, and the study population is free of the disease occurring in the study), 2 for comparability, and 3 for outcome (outcome measures are independent and reliable, follow-up is sufficiently long, complete follow-up). The quality of the literature was assessed and scored by a team of three. The disputed indicator scores were decided by discussion in a three-person panel. If there was disagreement, a fourth author was allowed to step in for discussion to arrive at the final result. A score of ≤4 was considered a low-quality study, and a score of ≥7 was considered a high-quality study. The final results were visualized using R (R Foundation, Vienna, Austria). In addition, the specific scores were represented through the baseline table in the Supplementary Table S1, available at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esmoop.2024.102241.

Statistical analysis

For BMI-related data, HR values for OS were used for meta-analysis. The study was divided into three groups: obese versus nonobese, underweight versus normal weight, and overweight versus normal weight. For weight change-related data, HR data for OS and mortality data with the event and total numbers in the exposed and non-exposed groups as initial data were used for meta-analysis. The two initial data types were divided into two separate groups: weight gain versus nonweight change and weight loss versus nonweight change.

The results of the meta-analysis were obtained using RevMan software, version 5.3 (Cochrane, London, UK), retaining both the fixed-effects model and the random-effects model, and mapped using R software, version 4.1.3, where the R packages used for the mapping were grid (version 4.2.2), forestploter (version 0.2.3), pheatmap (version 1.0.12), and meta (version 6.0.0). Dichotomous variables were expressed using HR data, and point estimates and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were given for each effect value. Z tests were used to test the combined statistics at P = 0.05. Two-sided P values <0.05 were considered statistically significant. The Q test and I2 index were used to assess between-study heterogeneity. We considered I2 values <50% to indicate low heterogeneity and used a fixed-effects model for meta-analysis. I2 values >50% indicated high heterogeneity, and after excluding the effects of other clinical heterogeneities, a random-effects model was used for meta-analysis. We then used sensitivity analysis to further analyze heterogeneity. The results of the data analysis are presented in the form of a forest plot.

Sensitivity analysis

Sensitivity analysis in meta-analysis involves modifying conditions to assess the stability of conclusions. Stable results enhance credibility, while significant variations require caution in interpretation and drawing conclusions.33 In this study, sensitivity analysis was carried out by excluding each study individually.

Analysis of publication bias

Reporting bias refers to the fact that the dissemination of scientific research is influenced by the nature and direction of its results. There are seven categories of reporting bias.34 Publication bias is the most popular and the most studied category. It refers to the bias caused by the nature and direction of the research resulting in the publication or nonpublication of research results. In this study, a funnel plot was used to identify the presence of publication bias.

Results

Study selection

We obtained a total of 9728 records in the search. After removing duplicates and downloading the full text, we obtained 5274 records. After reading the full text and applying the exclusion criteria, 4871 documents were excluded, for a total of 403 studies. After reading the titles and abstracts, 101 case–control studies, meta-analysis studies, and reviews were removed, leaving 302 documents. Studies for which the full text was unavailable and could not be downloaded (n = 4), for which valid primary data could not be extracted (n = 25), and for which only multifactor analysis was available or HR was adjusted (n = 63) were excluded. A total of 210 papers with univariate analysis and no HR adjustment were retained. Excluding data that were not discussed, a total of 73 papers were included in the final meta-analysis. Papers with HR data for OS were retained for BMI-related data (n = 52).24,35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47, 48, 49, 50, 51, 52, 53, 54, 55, 56, 57, 58, 59, 60, 61, 62, 63, 64, 65, 66, 67, 68, 69, 70, 71, 72, 73, 74, 75, 76, 77, 78, 79, 80, 81, 82, 83, 84, 85 For weight change-related data, both HR data for OS and mortality data with events and total number of people in the exposed and non-exposed groups as initial data were retained (n = 27).24,26,41,48,51,76,86, 87, 88, 89, 90, 91, 92, 93, 94, 95, 96, 97, 98, 99, 100, 101, 102, 103, 104, 105, 106

Characteristics of the included studies

Supplementary Table S1, available at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esmoop.2024.102241, describes the characteristics of the studies included in this meta-analysis. We included a total of 73 cohort studies that were published between 2007 and 2022, with 52 cohort studies for the analysis of BMI in relation to cancer prognosis and 27 cohort studies for the analysis of weight change in relation to cancer prognosis. Supplementary Table S2, available at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esmoop.2024.102241, describes the specific data of the studies we included.

The cohorts included in the studies involved ∼220 000 participants, of which the minimum cohort size at baseline was 44 and the maximum cohort included a total of 54 631 participants. The age distribution of the enrolled participants ranged from 18 to 99 years. Cancers present at enrollment included common cancers such as breast cancer, CRC, gastric cancer, endometrial cancer, and ovarian cancer, with a median or mean follow-up time of >30 months in most cases. The cut-off values used to define nonobese, obese, underweight, normal weight, overweight, weight loss, nonweight change, and weight gain for each study and where the study appears in the figure are also described.

We used the NOS to score the studies included in the meta-analysis and the results are shown in Supplementary Figure S1, available at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esmoop.2024.102241. We found a total of 29 studies with a score of 9, 29 with a score of 8, 15 with a score of 7, 6 with a score of 6, 2 with a score of 5, and 1 with a score of 4. The quality of the literature was generally high, with 64 high-quality studies and only 1 low-quality study.

Qualitative symmetry was observed in the funnel plots shown in Supplementary Figure S2, available at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esmoop.2024.102241, which indicated no significant publication bias. To examine the effect of individual studies on the overall combined effect size, we excluded each included study individually and then reran the meta-analysis on the remaining studies. We found that the point estimates of the combined effect sizes fell within the 95% CI for the overall combined effect size when excluding any one study, suggesting that the combined effect size of the remaining studies had little effect on the overall combined effect size, indicating stable study results.

Meta-analyses

Prognostic correlation analysis

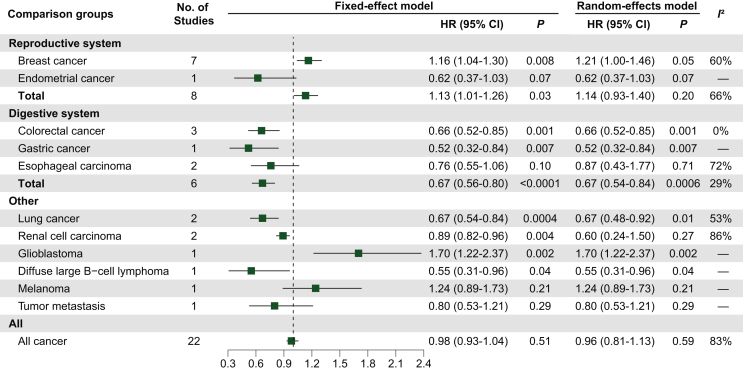

The results of the obese versus nonobese analysis are shown in Figure 2. In this analysis, we included 22 studies,24,37,42, 43, 44,46,47,50,53,55,56,59,66,67,71,72,74,77,80,81,84 with a total I2 of 83% and an HR of 0.96 (95% CI 0.81-1.13; P = 0.59). Eight studies were included in the analysis of reproductive system cancers, including breast cancer (n = 7) and endometrial cancer (n = 1), and the results were not statistically significant. However, breast cancer studies alone had a statistically significant difference (I2 = 60%; HR 1.21, 95% CI 1.00-1.46; P = 0.05). Six studies were included in the digestive system cancer analysis, including CRC (n = 3), esophageal carcinoma (n = 2). and gastric cancer (n = 1), and the results were statistically significant (I2 = 29%; HR 0.67, 95% CI 0.56-0.80; P < 0.0001). Eight studies were analyzed for other tumors, including lung cancer (n = 2), renal cell carcinoma (n = 2), glioblastoma (n = 1), diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (n = 1), melanoma (n = 1), and tumor metastasis (n = 1).

Figure 2.

Effect of obesity versus nonobesity on tumor prognosis in tumor type subgroups, using HR for OS as raw data.

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio.

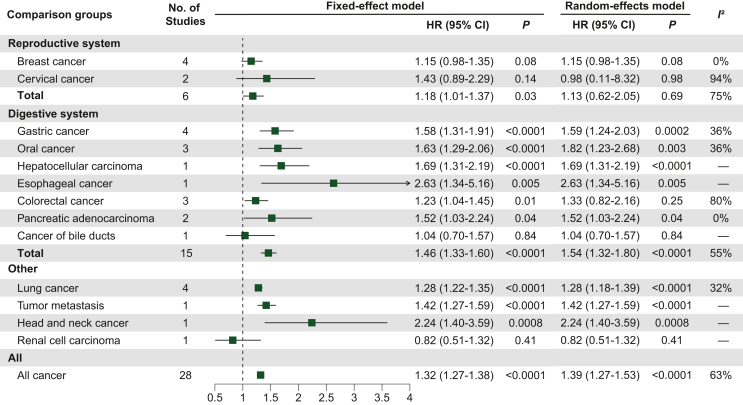

The underweight versus normal weight analysis results are shown in Figure 3. We included 28 studies with a total I2 of 63% and an HR of 1.39 (95% CI 1.27-1.53; P < 0.0001), and the results were statistically significant.35,36,38, 39, 40, 41,45,48,49,51,52,57,60, 61, 62, 63, 64, 65,69,70,73,75,76,78,79,81,82,85 Six studies were analyzed for reproductive system cancers, including breast cancer (n = 4) and cervical cancer (n = 2), and the results were not statistically significant. Breast cancer studies alone had a near significant result (I2 = 0%, HR 1.15, 95% CI 0.98-1.35; P = 0.08). Fifteen studies were included in the analysis of cancers of the digestive system, including gastric cancer (n = 4), oral cancer (n = 3), CRC (n = 3), pancreatic adenocarcinoma (PAAD; n = 2), hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC; n = 1), esophageal carcinoma (n = 1), and cancer of the bile ducts (n = 1), and the results were statistically significant (I2 = 55%, HR 1.54, 95% CI 1.32-1.80; P < 0.0001). Seven studies were analyzed for other cancers, including lung cancer (n = 4), tumor metastasis (n = 1), head and neck cancer (n = 1), and renal cell carcinoma (n = 1). Among these, lung cancer studies had statistically significant results (I2 = 32%; HR 1.28, 95% CI 1.22-1.35; P < 0.0001).

Figure 3.

Effect of underweight versus normal weight on tumor prognosis in tumor type subgroups, using HR for OS as raw data.

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio.

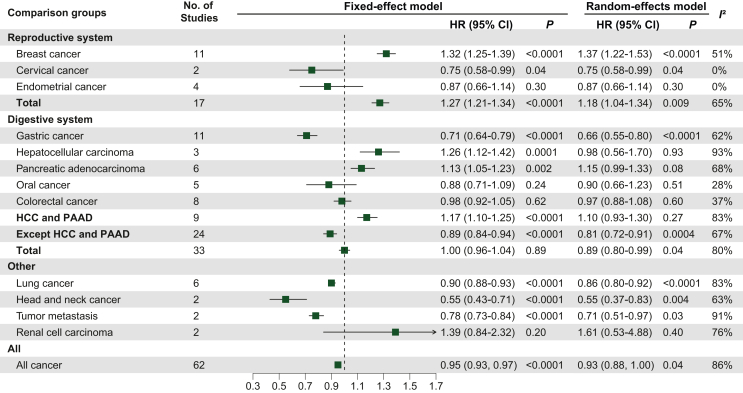

Overweight versus normal analysis results are shown in Figure 4. We included a total of 62 studies with a total I2 of 86% and an HR of 0.93 (95% CI 0.88-1.00; P = 0.04), and the results were statistically significant.35,36,39, 40, 41,45,49,51,54,57,58,60, 61, 62, 63, 64, 65,68, 69, 70,73,75,78,81, 82, 83,85 Seventeen studies analyzed cancers of the reproductive system, including breast cancer (n = 11), endometrial cancer (n = 4) and cervical cancer (n = 2), and the results were statistically significant (I2 = 65%; HR 1.18, 95% CI 1.04-1.34; P = 0.009). Of these, the results were statistically significant for breast cancer (I2 = 51%; HR 1.37, 95% CI 1.22-1.53; P < 0.0001). A total of 33 studies were included in the analysis of cancers of the digestive system, including gastric cancer (n = 11), CRC (n = 8), PAAD (n = 6), oral cancer (n = 5), and HCC (n = 3), and the results were statistically significant (I2 = 80%; HR 0.89, 95% CI 0.80-0.99; P = 0.04). Of note, when HCC and PAAD were excluded, the results for the other digestive system-related cancers were more statistically significant (I2 = 67%; HR 0.81, 95% CI 0.72-0.91; P = 0.0004). Twelve studies were analyzed for other cancers, including lung cancer (n = 6), head and neck cancer (n = 2), tumor metastasis (n = 2), and renal cell carcinoma (n = 2). Among these, the results for lung cancer were statistically significant (I2 = 83%; HR 0.86, 95% CI 0.80-0.92; P< 0.0001).

Figure 4.

Effect of overweight versus normal weight on tumor prognosis in tumor type subgroups, using HR for OS as raw data.

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; HR, hazard ratio; PAAD, pancreatic adenocarcinoma.

Weight change correlation analysis

The results of the weight change analysis with the number of events and total people as the initial data are shown in Supplementary Figure S3, available at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esmoop.2024.102241. Seven studies were included in the analysis of weight gain versus nonweight change, with a total I2 of 65% and an HR of 1.00 (95% CI 0.89-1.12; P = 0.99), and the results were not statistically significant.86,96,97,100, 101, 102, 103 For the weight loss versus nonweight change analysis, a total of 7 studies were included with a total I2 of 88% and an HR of 1.38 (95% CI 1.12-1.71; P = 0.003), with statistically significant differences in results.86,96,97,100, 101, 102, 103 When grouped according to different weight change thresholds, the analysis for weight loss >5% versus weight loss <5% had a statistically significant difference (I2 = 96%; HR 1.68, 95% CI 1.08-2.61; P = 0.02). When grouped by different cancer types, the results were statistically significant for breast cancer (I2 = 92%; HR 1.88, 95% CI 1.18-3.00; P = 0.008) and reproductive system cancers (I2 = 89%; HR 1.47, 95% CI 1.12-1.92; P = 0.005).

The results of the analysis using the HR data for OS as the initial data are shown in Supplementary Figure S4, available at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esmoop.2024.102241. Among these, two studies were included in the analysis of weight gain versus nonweight change,24,41 with a total I2 of 89% and an HR of 3.53 (95% CI 0.46-27.13; P = 0.23). Twenty studies were included in the analysis of weight loss versus nonweight loss,24,26,41,48,51,76,87, 88, 89, 90, 91, 92, 93, 94, 95,98,99,104, 105, 106 with a total I2 of 88% and an HR of 1.66 (95% CI 1.33-2.07; P < 0.0001), and the results were statistically significant. With different weight change threshold groupings, analyses of weight loss >10% versus weight loss <10% had an I2 of 75% and an HR of 2.10 (95% CI 1.37-3.21; P = 0.0006), and the results were statistically significant. With different cancer type groupings, the results were statistically significant for gastric cancer (I2 = 0%; HR 1.55, 95% CI 1.31-1.84; P < 0.0001) and digestive system cancer (I2 = 48%; HR 1.44, 95% CI 1.33-1.56; P < 0.0001).

Prognostic correlation analysis associated with tumor stage

We finally selected three papers each that specifically examined early-staged37,42,66 or advanced-staged43,44,73 tumors. We carried out a meta-analysis of the relationship between obesity and tumor OS for early-stage overall cancers and advanced-stage overall cancers independently. The HR after combining the random effects model showed that compared with nonobesity, obesity was a risk factor for patients with early-stage cancer (HR 1.33, 95% CI 1.07-1.64; P = 0.009) but a protective factor for patients with advanced-stage cancer (HR 0.9, 95% CI 0.83-0.97; P = 0.005). Furthermore, the difference between these two subgroups was statistically significant (P = 0.007; Supplementary Figure S5, available at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esmoop.2024.102241).

Discussion

This meta-analysis focused on the relationship of both BMI and weight change with the prognosis of patients with cancer. Our findings suggest that compared with normal weight, underweight is a significant risk factor for a patient’s OS for all kinds of cancers included in the analysis and is also a risk factor for OS in almost all specific cancers (e.g. breast cancers, gastric cancers, and lung cancers). The relationship between obesity and cancer OS varies by cancer type. In terms of weight change, we found that any degree of weight loss was a risk factor for OS in patients with cancer; weight gain was not significantly associated with OS.

In reproductive cancers, we focused on the relationship between BMI and OS in patients with breast cancer. According to the meta-analysis, obesity was a risk factor for OS in patients with breast cancer compared with those who are nonobese; overweight was a risk factor for OS in patients with breast cancer compared with patients with normal weight. Meanwhile, underweight was a potential risk factor for OS in patients with breast cancer compared with normal weight. Based on the findings of the available studies, we found that the relationship between prediagnostic and postdiagnostic weight change and the prognosis of patients with breast cancer may be different. Studies showing the relationship between weight gain before diagnosis and breast cancer prognosis are unclear.107 However, several studies have shown that weight gain after diagnosis is associated with higher breast cancer-specific mortality than no change in weight, which may be related to the fact that high BMI and high body weight increase the levels of inflammatory markers that can damage the body.108, 109, 110, 111 Jackson et al.109 found that weight loss was associated with a higher risk of death in patients with breast cancer than no change in weight, which may be related to alterations in the tumor microenvironment.112 Notably, the intention to lose weight was not assessed in these studies, and unintentional weight loss may be the result of advancing cancer progression.107

In digestive system cancers, we found that compared with nonobesity, overweight and obesity may have different effects on OS in different digestive system cancer types. According to the meta-analysis, obesity was a protective factor for OS in patients with digestive system cancers compared with nonobesity; overweight was a protective factor for OS in patients with digestive system cancers compared with normal weight, but it should be noted that overweight was a risk factor for OS in patients with HCC and PAAD compared with normal weight. The results of the meta-analysis of digestive system tumors were more significant when HCC and PAAD were removed. At the same time, underweight was a risk factor for OS in patients with digestive tumors compared with normal weight. A study has shown that obesity contributes to metabolic syndrome and subsequent chronic liver disease, which increases the risk of developing HCC and cirrhosis.113 Furthermore, patients with obesity with HCC are at a higher risk of postoperative complications, including hepatic decompensation, biliary leakage, and wound infection, which may result in increased mortality after HCC (adjusted HR 1.95, 95% CI 1.46-2.46).113 Majumder et al.114 observed increased mortality associated with pancreatic cancer in patients with overweight (adjusted HR 1.06, 95% CI 1.02-1.11) and patients with obesity (adjusted HR 1.31, 95% CI 1.20-1.42) compared with patients with normal weight. Han et al.115 found that high BMI was a risk factor for OS (HR 1.22, 95% CI 1.01-1.43) in patients with pancreatic cancer compared with low BMI. The mechanisms associated with underweight on the prognosis of digestive system cancers are unclear.107

In lung cancer, underweight, overweight, and obesity were all associated with OS in patients. According to a meta-analysis, obesity was a protective factor for OS in patients with lung cancer compared with nonobesity, and overweight was a protective factor for OS in patients with lung cancer compared with normal weight. In addition, underweight was a potential risk factor for OS in patients with breast cancer compared with normal weight. In a study of patients with lung cancer treated with certain chemotherapeutic agents,116 there was evidence of a survival advantage for patients with higher BMI. In addition, one study observed an interaction between the use of metformin and the effect of BMI on OS, with a greater benefit of metformin use observed in patients as BMI increased.117 Furthermore, a study on patients with non-small-cell lung cancer receiving sodium butyrate monotherapy as second-line treatment found that BMI was significantly associated with OS, with higher BMI being associated with longer survival than lower BMI.118 BMI <18.5 kg/m2 was independently associated with tolerance to radiotherapy (concurrent chemoradiotherapy; OR 0.36), and intolerance to concurrent chemoradiotherapy was independently associated with poorer survival.119 However, because smoking is an important risk factor for lung cancer and smokers tend to have a lower BMI, this may confound the association between BMI and cancer survival.

Our analysis revealed that compared with no change in weight, any degree of weight loss and weight loss >10% (HR 2.07, 95% CI 1.73-3.21; P = 0.0006) were risk factors for OS of all kinds of cancers included in the analysis. When grouped according to different tumor types, weight loss compared with no change in weight increased the risk of shorter OS in patients with gastric cancer, breast cancer, reproductive cancers, and gastrointestinal tract tumors. A study has shown that weight loss is a common manifestation of malnutrition in patients with cancer.120 Cancer cells may exacerbate muscle loss in patients with tumors, which leads to weight loss.120 For example, patients with advanced gastric cancer lose muscle mass over the course of treatment, which may lead to increased chemotherapy toxicity and impaired physical function and quality of life, resulting in shorter OS for patients (HR 1.58, 95% CI 1.37-1.83).88 However, findings related to the impact of weight loss compared with no change in weight on survival outcomes in patients with breast cancer have been inconsistent: the study by Kroenke et al.121 showed an increased risk of breast cancer-specific mortality in patients with weight loss (HR 7.98, 95% CI 3.51-19.0), while the study by Bradshaw et al.122 found no significant association between weight loss and breast cancer-specific mortality (HR 0.81, 95% CI 0.57-1.15). This inconsistency in findings may be related to the varying willingness to lose weight among patients with breast cancer in the cohort. More observational studies have shown that intentional weight loss is associated with improved breast cancer outcomes,123 whereas there are no uniform findings on the effect of unintentional weight loss on breast cancer outcomes; however, most relevant studies have been unable to avoid the fact that all weight loss in the cohort of patients with breast cancer was unintentional.

There are some limitations to this article. First, the cut-off values for the articles’ BMI and weight change classifications were not unified, which may lead to conclusions that are not rigorous. As the articles were not uniform in their critical values for the classification of BMI and weight change, this may have led to conclusions that are somewhat biased. We combined the intervals of underweight, normal weight, overweight, and obese as defined in each article and analyzed them together. For example, in the overweight versus normal analysis, the BMI range from 25 to 30 kg/m2 and BMI ≥30 kg/m2 were both defined as overweight, while BMI ranges from 18.5 to 23.0 kg/m2 and from 18.5 to 25.0 kg/m2 were both defined as normal weight. In the analysis examining the association of weight change with OS outcomes in different cancers, cohort data for different cancers were combined in the subgroups with weight loss >5% and weight loss >10%. In addition, data on the prognostic risk of different levels of weight loss compared with no change in weight were also included in the subgroups for prognosis of gastric cancer, breast cancer, reproductive system cancer, and gastrointestinal tract cancer.

Second, the article is based on BMI as an exposure factor, which is a proxy for obesity but not a direct measure of obesity. Visceral adiposity is a more active metabolic activity between adipose tissue compartments that may affect cancer survival.107 We searched and read the relevant literature and found that the conclusions of this literature were similar to the conclusions of our study. For example, Carmichael124 concluded that a high waist-to-hip ratio was directly associated with breast cancer mortality in postmenopausal women, which is consistent with the result of our study that ‘being overweight or obese is a risk factor for poorer survival in breast cancer compared with normal weight’. By contrast, another study concluded that the difference in survival of patients with cancer was not significant when BMI and waist-to-hip ratio were used as indicators of obesity.125 However, the study by Hanyuda et al.126 found that the percentage of body fat was quite positively correlated with CRC mortality, which is inconsistent with the finding that ‘overweight is a good protective factor for survival in CRC’ in our study. This suggests that there may be differences in the effects of different obesity indicators on CRC progression, and further exploratory studies are needed in the future. In addition, indicators such as muscle-fat ratio, fat-free BMI, and visceral adiposity have not been systematically discussed now in terms of their significance in tumor survival. Whether these metrics are consistent in pointing to survival in the same tumor and the differences in predicting survival significance within different tumors need to be further explored in the future.

Third, existing studies have confirmed that intentional weight loss is a protective factor for prognosis in patients with breast cancer.127 However, studies of general population samples have shown that unintentional weight loss is associated with increased prognostic risk, while intentional weight loss has no effect on OS.128 This analysis avoided the inclusion of cohort studies related to intentional weight loss, opting instead for studies in which weight change data were obtained by self-report or third-party institutional measurement. However, there was no clear way to determine whether the data obtained were from intentional or unintentional weight loss. All of these factors may lead to greater heterogeneity in the meta-analysis.

In conclusion, we believe that in certain tumors, BMI and weight change are significantly correlated with tumor prognosis. Compared with normal weight, overweight or obesity is a risk factor for OS in breast cancer, while in gastrointestinal tumors (including gastric, esophageal, and CRCs) as well as lung cancer, obesity is a protective factor for OS compared with nonobesity. Compared with normal weight, underweight is a risk factor for OS in patients with breast cancer, gastrointestinal tumors, and lung cancer. Compared with no weight change, weight loss is a risk factor for OS in patients with gastric and gastrointestinal cancers.

Acknowledgements

None.

Funding

None declared.

Disclosure

The authors have declared no conflicts of interest.

Contributor Information

A. Lin, Email: smulinanqi0206@i.smu.edu.cn.

Q. Cheng, Email: chengquan@csu.edu.cn.

J. Zhang, Email: zhangjian@i.smu.edu.cn.

P. Luo, Email: luopeng@smu.edu.cn.

Supplementary data

References

- 1.GBD 2015 Risk Factors Collaborators Global, regional, and national comparative risk assessment of 79 behavioural, environmental and occupational, and metabolic risks or clusters of risks, 1990-2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet. 2016;388(10053):1659–1724. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31679-8. [published correction appears in Lancet. 2017 Jan 7;389(10064):e1] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vordenberg S.E., Thompson A.N., Vereecke A., et al. Primary care provider perceptions of an integrated community pharmacy hypertension management program. J Am Pharm Assoc (2003) 2021;61(3):e107–e113. doi: 10.1016/j.japh.2020.11.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sung H., Ferlay J., Siegel R.L., et al. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71(3):209–249. doi: 10.3322/caac.21660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tam-McDevitt J. Polypharmacy, aging, and cancer. Oncology (Williston Park, NY) 2008;22(9):1052–1060. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Grosso G., Bella F., Godos J., et al. Possible role of diet in cancer: systematic review and multiple meta-analyses of dietary patterns, lifestyle factors, and cancer risk. Nutr Rev. 2017;75(6):405–419. doi: 10.1093/nutrit/nux012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Crowe F.L., Appleby P.N., Travis R.C., Key T.J. Risk of hospitalization or death from ischemic heart disease among British vegetarians and nonvegetarians: results from the EPIC-Oxford cohort study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2013;97(3):597–603. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.112.044073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Leon M.E., Peruga A., McNeill A., et al. European code against cancer, 4th edition: tobacco and cancer. Cancer Epidemiol. 2015;39(suppl 1):S20–S33. doi: 10.1016/j.canep.2015.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rumgay H., Shield K., Charvat H., et al. Global burden of cancer in 2020 attributable to alcohol consumption: a population-based study. Lancet Oncol. 2021;22(8):1071–1080. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(21)00279-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lewandowska A.M., Rudzki M., Rudzki S., Lewandowski T., Laskowska B. Environmental risk factors for cancer - review paper. Ann Agric Environ Med. 2019;26(1):1–7. doi: 10.26444/aaem/94299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Haslam D.W., James W.P.T. Obesity. Lancet. 2005;366(9492):1197–1209. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67483-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Calle E.E., Kaaks R. Overweight, obesity and cancer: epidemiological evidence and proposed mechanisms. Nat Rev Cancer. 2004;4(8):579–591. doi: 10.1038/nrc1408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Calle E.E., Rodriguez C., Walker-Thurmond K., Thun M.J. Overweight, obesity, and mortality from cancer in a prospectively studied cohort of U.S. adults. N Engl J Med. 2003;348(17):1625–1638. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa021423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rathmell J.C. Obesity, immunity, and cancer. N Engl J Med. 2021;384(12):1160–1162. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcibr2035081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li Y., Li C., Wu G., et al. The obesity paradox in patients with colorectal cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Nutr Rev. 2022;80(7):1755–1768. doi: 10.1093/nutrit/nuac005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jaspan V., Lin K., Popov V. The impact of anthropometric parameters on colorectal cancer prognosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2021;159 doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2021.103232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Parkin E., O’Reilly D.A., Sherlock D.J., Manoharan P., Renehan A.G. Excess adiposity and survival in patients with colorectal cancer: a systematic review. Obes Rev. 2014;15(5):434–451. doi: 10.1111/obr.12140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gupta A., Majumder K., Arora N., et al. Premorbid body mass index and mortality in patients with lung cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lung Cancer. 2016;102:49–59. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2016.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang J., Xu H., Zhou S., et al. Body mass index and mortality in lung cancer patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2018;72(1):4–17. doi: 10.1038/ejcn.2017.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shukla S., Babcock Z., Pizzi L., Brunetti L. Impact of body mass index on survival and serious adverse events in advanced non-small cell lung cancer treated with bevacizumab: a meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Curr Med Res Opin. 2021;37(5):811–817. doi: 10.1080/03007995.2021.1900091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chan D.S.M., Vieira A.R., Aune D., et al. Body mass index and survival in women with breast cancer—systematic literature review and meta-analysis of 82 follow-up studies. Ann Oncol. 2014;25(10):1901–1914. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdu042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kokts-Porietis R.L., Elmrayed S., Brenner D.R., Friedenreich C.M. Obesity and mortality among endometrial cancer survivors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes Rev. 2021;22(12) doi: 10.1111/obr.13337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sánchez Y., Vaca-Paniagua F., Herrera L., et al. Nutritional indexes as predictors of survival and their genomic implications in gastric cancer patients. Nutr Cancer. 2021;73(8):1429–1439. doi: 10.1080/01635581.2020.1797833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Escala-Garcia M., Morra A., Canisius S., et al. Breast cancer risk factors and their effects on survival: a Mendelian randomisation study. BMC Med. 2020;18:327. doi: 10.1186/s12916-020-01797-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Matsuo K., Moeini A., Cahoon S.S., et al. Weight change pattern and survival outcome of women with endometrial cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2016;23(9):2988–2997. doi: 10.1245/s10434-016-5237-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhao L.L., Huang H., Wang Y., et al. Lifestyle factors and long-term survival of gastric cancer patients: a large bidirectional cohort study from China. World J Gastroenterol. 2020;26(14):1613–1627. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v26.i14.1613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kuo Y.H., Shi C.S., Huang C.Y., Huang Y.C., Chin C.C. Prognostic significance of unintentional body weight loss in colon cancer patients. Mol Clin Oncol. 2018;8(4):533–538. doi: 10.3892/mco.2018.1582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Franceschini J.P., Jamnik S., Santoro I.L. Role that anorexia and weight loss play in patients with stage IV lung cancer. J Bras Pneumol. 2020;46(4) doi: 10.36416/1806-3756/e20190420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Majed B., Moreau T., Senouci K., Salmon R.J., Fourquet A., Asselain B. Is obesity an independent prognosis factor in woman breast cancer? Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2008;111(2):329–342. doi: 10.1007/s10549-007-9785-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Befort C.A., Klemp J.R., Austin H.L., et al. Outcomes of a weight loss intervention among rural breast cancer survivors. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2012;132(2):631–639. doi: 10.1007/s10549-011-1922-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Playdon M.C., Bracken M.B., Sanft T.B., Ligibel J.A., Harrigan M., Irwin M.L. Weight gain after breast cancer diagnosis and all-cause mortality: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2015;107(12):djv275. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djv275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.WHO Expert Consultation Appropriate body-mass index for Asian populations and its implications for policy and intervention strategies. Lancet. 2004;363(9403):157–163. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)15268-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ottawa Hospital Research Institute. https://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp Available at.

- 33.Chapter 10: Analysing data and undertaking meta-analyses. https://training.cochrane.org/handbook/current/chapter-10 Available at.

- 34.Chapter 7: Considering bias and conflicts of interest among the included studies. https://training.cochrane.org/handbook/current/chapter-07 Available at.

- 35.Schvartsman G., Gutierrez-Barrera A.M., Song J., Ueno N.T., Peterson S.K., Arun B. Association between weight gain during adjuvant chemotherapy for early-stage breast cancer and survival outcomes. Cancer Med. 2017;6(11):2515–2522. doi: 10.1002/cam4.1207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lee S., Lee D.H., Lee J.H., et al. Association of body mass index with survival in Asian patients with colorectal cancer. Cancer Res Treat. 2022;54(3):860–872. doi: 10.4143/crt.2021.656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tong Y., Zhu S., Chen W., Chen X., Shen K. Association of obesity and luminal subtypes in prognosis and adjuvant endocrine treatment effectiveness prediction in Chinese breast cancer patients. Front Oncol. 2022;12 doi: 10.3389/fonc.2022.862224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Adnan Y., Ali S.M.A., Awan M.S., et al. Body mass index and diabetes mellitus may predict poorer overall survival of oral squamous cell carcinoma patients: a retrospective cohort from a tertiary-care centre of a resource-limited country. Clin Med Insights Oncol. 2022;16 doi: 10.1177/11795549221084832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gama R.R., Song Y., Zhang Q., et al. Body mass index and prognosis in patients with head and neck cancer. Head Neck. 2017;39(6):1226–1233. doi: 10.1002/hed.24760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kim E.Y., Jun K.H., Kim S.Y., Chin H.M. Body mass index and skeletal muscle index are useful prognostic factors for overall survival after gastrectomy for gastric cancer: retrospective cohort study. Medicine (Baltimore) 2020;99(47) doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000023363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kang J., Lee S.H., Son J.H., et al. Body mass index and weight change during initial period of chemotherapy affect survival outcome in advanced biliary tract cancer patients. PLoS One. 2018;13(4) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0195118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wang X., Hui T.L., Wang M.Q., Liu H., Li R.Y., Song Z.C. Body mass index at diagnosis as a prognostic factor for early-stage invasive breast cancer after surgical resection. Oncol Res Treat. 2019;42(4):195–201. doi: 10.1159/000496548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Santoni M., Massari F., Bracarda S., et al. Body mass index in patients treated with cabozantinib for advanced renal cell carcinoma: a new prognostic factor? Diagnostics (Basel) 2021;11(1):138. doi: 10.3390/diagnostics11010138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Esposito A., Marra A., Bagnardi V., et al. Body mass index, adiposity and tumour infiltrating lymphocytes as prognostic biomarkers in patients treated with immunotherapy: a multi-parametric analysis. Eur J Cancer. 2021;145:197–209. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2020.12.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kuo Y.H., Lee K.F., Chin C.C., Huang W.S., Yeh C.H., Wang J.Y. Does body mass index impact the number of LNs harvested and influence long-term survival rate in patients with stage III colon cancer? Int J Colorectal Dis. 2012;27(12):1625–1635. doi: 10.1007/s00384-012-1496-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cho W.K., Choi D.H., Park W., et al. Effect of body mass index on survival in breast cancer patients according to subtype, metabolic syndrome, and treatment. Clin Breast Cancer. 2018;18(5):e1141–e1147. doi: 10.1016/j.clbc.2018.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ladoire S., Dalban C., Roché H., et al. Effect of obesity on disease-free and overall survival in node-positive breast cancer patients in a large French population: a pooled analysis of two randomised trials. Eur J Cancer. 2014;50(3):506–516. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2013.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yu X.L., Yang J., Chen T., et al. Excessive pretreatment weight loss is a risk factor for the survival outcome of esophageal carcinoma patients undergoing radical surgery and postoperative adjuvant chemotherapy. Can J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;2018 doi: 10.1155/2018/6075207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Clark L.H., Jackson A.L., Soo A.E., Orrey D.C., Gehrig P.A., Kim K.H. Extremes in body mass index affect overall survival in women with cervical cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2016;141(3):497–500. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2016.03.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Juszczyk K., Kang S., Putnis S., et al. High body mass index is associated with an increased overall survival in rectal cancer. J Gastrointest Oncol. 2020;11(4):626–632. doi: 10.21037/jgo-20-48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Meyerhardt J.A., Niedzwiecki D., Hollis D., et al. Impact of body mass index and weight change after treatment on cancer recurrence and survival in patients with stage III colon cancer: findings from Cancer and Leukemia Group B 89803. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(25):4109–4115. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.15.6687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Okura T., Fujii M., Shiode J., et al. Impact of body mass index on survival of pancreatic cancer patients in Japan. Acta Med Okayama. 2018;72(2):129–135. doi: 10.18926/AMO/55853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Cha J.Y., Park J.S., Hong Y.K., Jeun S.S., Ahn S. Impact of body mass index on survival outcome in patients with newly diagnosed glioblastoma: a retrospective single-center study. Integr Cancer Ther. 2021;20 doi: 10.1177/1534735421991233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Shang L., Hattori M., Fleming G., et al. Impact of post-diagnosis weight change on survival outcomes in Black and White breast cancer patients. Breast Cancer Res. 2021;23(1):18. doi: 10.1186/s13058-021-01397-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Weiss L., Melchardt T., Habringer S., et al. Increased body mass index is associated with improved overall survival in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Ann Oncol. 2014;25(1):171–176. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdt481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wisse A., Tryggvadottir H., Simonsson M., et al. Increasing preoperative body size in breast cancer patients between 2002 and 2016: implications for prognosis. Cancer Causes Control. 2018;29(7):643–656. doi: 10.1007/s10552-018-1042-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Park B., Jeong B.C., Seo S.I., Jeon S.S., Choi H.Y., Lee H.M. Influence of body mass index, smoking, and blood pressure on survival of patients with surgically-treated, low stage renal cell carcinoma: a 14-year retrospective cohort study. J Korean Med Sci. 2013;28(2):227–236. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2013.28.2.227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Dandona M., Linehan D., Hawkins W., Strasberg S., Gao F., Wang-Gillam A. Influence of obesity and other risk factors on survival outcomes in patients undergoing pancreaticoduodenectomy for pancreatic cancer. Pancreas. 2011;40(6):931–937. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0b013e318215a9b1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Shah M.S., Fogelman D.R., Raghav K.P.S., et al. Joint prognostic effect of obesity and chronic systemic inflammation in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. Cancer. 2015;121(17):2968–2975. doi: 10.1002/cncr.29440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ma S., Liu H., Ma F.H., et al. Low body mass index is an independent predictor of poor long-term prognosis among patients with resectable gastric cancer. World J Gastrointest Oncol. 2021;13(3):161–173. doi: 10.4251/wjgo.v13.i3.161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Yu J.J., Shen F., Chen T.H., et al. Multicentre study of the prognostic impact of preoperative bodyweight on long-term prognosis of hepatocellular carcinoma. Br J Surg. 2019;106(3):276–285. doi: 10.1002/bjs.10981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zhao T.C., Liang S.Y., Ju W.T., et al. Normal BMI predicts the survival benefits of inductive docetaxel, cisplatin, and 5-fluorouracil in patients with locally advanced oral squamous cell carcinoma. Clin Nutr. 2020;39(9):2751–2758. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2019.11.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Bao X., Liu F., Lin J., et al. Nutritional assessment and prognosis of oral cancer patients: a large-scale prospective study. BMC Cancer. 2020;20(1):146. doi: 10.1186/s12885-020-6604-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.McWilliams R.R., Matsumoto M.E., Burch P.A., et al. Obesity adversely affects survival in pancreatic cancer patients. Cancer. 2010;116(21):5054–5062. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Sinicrope F.A., Foster N.R., Sargent D.J., O’Connell M.J., Rankin C. Obesity is an independent prognostic variable in colon cancer survivors. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16(6):1884–1893. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-2636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Deckers E.A., Kruijff S., Bastiaannet E., van Ginkel R.J., Hoekstra-Weebers J.E.H.M., Hoekstra H.J. Obesity is not associated with disease-free interval, melanoma-specific survival, or overall survival in patients with clinical stage IB-II melanoma after SLNB. J Surg Oncol. 2021;124(4):655–664. doi: 10.1002/jso.26555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Arce-Salinas C., Aguilar-Ponce J.L., Villarreal-Garza C., et al. Overweight and obesity as poor prognostic factors in locally advanced breast cancer patients. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2014;146(1):183–188. doi: 10.1007/s10549-014-2977-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Chaves G.V., de Almeida Simao T., Pinto L.F.R., Moreira M.A.M., Bergmann A., Chaves C.B.P. Overweight and obesity do not determine worst prognosis in endometrioid endometrial carcinoma. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2019;300(6):1671–1677. doi: 10.1007/s00404-019-05281-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Tsang N.M., Pai P.C., Chuang C.C., et al. Overweight and obesity predict better overall survival rates in cancer patients with distant metastases. Cancer Med. 2016;5(4):665–675. doi: 10.1002/cam4.634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Morel H., Raynard B., d’Arlhac M., et al. Prediagnosis weight loss, a stronger factor than BMI, to predict survival in patients with lung cancer. Lung Cancer. 2018;126:55–63. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2018.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Rabinel P., Vergé R., Cazaux M., et al. Predictive factors and prognosis of microscopic residual disease in non-small-cell lung cancer surgery. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2022;62(4) doi: 10.1093/ejcts/ezac037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Lee C.H., Lin C., Wang C.Y., et al. Premorbid BMI as a prognostic factor in small-cell lung cancer-a single institute experience. Oncotarget. 2018;9(37):24642–24652. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.24935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Cortellini A., Ricciuti B., Vaz V.R., et al. Prognostic effect of body mass index in patients with advanced NSCLC treated with chemoimmunotherapy combinations. J Immunother Cancer. 2022;10(2) doi: 10.1136/jitc-2021-004374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Lee C.S., Won D.D., Oh S.N., et al. Prognostic role of pre-sarcopenia and body composition with long-term outcomes in obstructive colorectal cancer: a retrospective cohort study. World J Surg Oncol. 2020;18(1):230. doi: 10.1186/s12957-020-02006-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Park Y.S., Park D.J., Lee Y., et al. Prognostic roles of perioperative body mass index and weight loss in the long-term survival of gastric cancer patients. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2018;27(8):955–962. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-18-0122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Nakagawa T., Toyazaki T., Chiba N., Ueda Y., Gotoh M. Prognostic value of body mass index and change in body weight in postoperative outcomes of lung cancer surgery. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2016;23(4):560–566. doi: 10.1093/icvts/ivw175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Cheng Y., Wang N., Wang K., et al. Prognostic value of body mass index for patients undergoing esophagectomy for esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2013;43(2):146–153. doi: 10.1093/jjco/hys212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Jeon Y.W., Kang S.H., Park M.H., Lim W., Cho S.H., Suh Y.J. Relationship between body mass index and the expression of hormone receptors or human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 with respect to breast cancer survival. BMC Cancer. 2015;15:865. doi: 10.1186/s12885-015-1879-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Yb C. Relationship of body mass index with prognosis in breast cancer patients treated with adjuvant radiotherapy and chemotherapy. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2014;15(10):4233–4238. doi: 10.7314/apjcp.2014.15.10.4233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Eroglu C., Orhan O., Karaca H., et al. The effect of being overweight on survival in patients with gastric cancer undergoing adjuvant chemoradiotherapy. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) 2013;22(1):133–140. doi: 10.1111/ecc.12010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.de Azambuja E., McCaskill-Stevens W., Francis P., et al. The effect of body mass index on overall and disease-free survival in node-positive breast cancer patients treated with docetaxel and doxorubicin-containing adjuvant chemotherapy: the experience of the BIG 02-98 trial. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2010;119(1):145–153. doi: 10.1007/s10549-009-0512-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Kizer N.T., Thaker P.H., Gao F., et al. The effects of body mass index on complications and survival outcomes in patients with cervical carcinoma undergoing curative chemoradiation therapy. Cancer. 2011;117(5):948–956. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Kim C.H., Park S.M., Kim J.J. The impact of preoperative low body mass index on postoperative complications and long-term survival outcomes in gastric cancer Patients. J Gastric Cancer. 2018;18(3):274–286. doi: 10.5230/jgc.2018.18.e30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Hayashi Y., Correa A.M., Hofstetter W.L., et al. The influence of high body mass index on the prognosis of patients with esophageal cancer after surgery as primary therapy. Cancer. 2010;116(24):5619–5627. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Alifano M., Daffré E., Iannelli A., et al. The reality of lung cancer paradox: the impact of body mass index on long-term survival of resected lung cancer. A French nationwide analysis from the Epithor database. Cancers (Basel) 2021;13(18):4574. doi: 10.3390/cancers13184574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Bao P.P., Cai H., Peng P., et al. Body mass index and weight change in relation to triple-negative breast cancer survival. Cancer Causes Control. 2016;27(2):229–236. doi: 10.1007/s10552-015-0700-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Langius J.A.E., Bakker S., Rietveld D.H.F., et al. Critical weight loss is a major prognostic indicator for disease-specific survival in patients with head and neck cancer receiving radiotherapy. Br J Cancer. 2013;109(5):1093–1099. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2013.458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Mansoor W., Roeland E.J., Chaudhry A., et al. Early weight loss as a prognostic factor in patients with advanced gastric cancer: analyses from REGARD, RAINBOW, and RAINFALL phase III studies. Oncologist. 2021;26(9):e1538–e1547. doi: 10.1002/onco.13836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Liu L., Erickson N.T., Ricard I., et al. Early weight loss is an independent risk factor for shorter survival and increased side effects in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer undergoing first-line treatment within the randomized phase III trial FIRE-3 (AIO KRK-0306) Int J Cancer. 2022;150(1):112–123. doi: 10.1002/ijc.33775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Brookman-May S., Kendel F., Hoschke B., et al. Impact of body mass index and weight loss on cancer-specific and overall survival in patients with surgically resected renal cell carcinoma. Scand J Urol Nephrol. 2011;45(1):5–14. doi: 10.3109/00365599.2010.515610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Mizukami T., Hamaji K., Onuki R., et al. Impact of body weight loss on survival in patients with advanced gastric cancer receiving second-line treatment. Nutr Cancer. 2022;74(2):539–545. doi: 10.1080/01635581.2021.1902542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Ghadjar P., Hayoz S., Zimmermann F., et al. Impact of weight loss on survival after chemoradiation for locally advanced head and neck cancer: secondary results of a randomized phase III trial (SAKK 10/94) Radiat Oncol. 2015;10:21. doi: 10.1186/s13014-014-0319-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Carnie L., Abraham M., McNamara M.G., Hubner R.A., Valle J.W., Lamarca A. Impact on prognosis of early weight loss during palliative chemotherapy in patients diagnosed with advanced pancreatic cancer. Pancreatology. 2020;20(8):1682–1688. doi: 10.1016/j.pan.2020.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Nikniaz Z., Somi M.H., Naghashi S. Malnutrition and weight loss as prognostic factors in the survival of patients with gastric cancer. Nutr Cancer. 2022;74(9):3140–3145. doi: 10.1080/01635581.2022.2059089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Han H.R., Hermann G.M., Ma S.J., et al. Matched pair analysis to evaluate weight loss during radiation therapy for head and neck cancer as a prognostic factor for survival. Ann Transl Med. 2021;9(10):914. doi: 10.21037/atm-20-4969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Chen X., Lu W., Zheng W., et al. Obesity and weight change in relation to breast cancer survival. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2010;122(3):823–833. doi: 10.1007/s10549-009-0708-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Laake I., Larsen I.K., Selmer R., Thune I., Veierød M.B. Pre-diagnostic body mass index and weight change in relation to colorectal cancer survival among incident cases from a population-based cohort study. BMC Cancer. 2016;16:402. doi: 10.1186/s12885-016-2445-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Zhang H., Yang Y., Shang Q., et al. Predictive value of preoperative weight loss on survival of elderly patients undergoing surgery for esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Transl Cancer Res. 2019;8(8):2752–2758. doi: 10.21037/tcr.2019.10.29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Watte G., Nunes CH. de A., Sidney-Filho L.A., et al. Proportional weight loss in six months as a risk factor for mortality in stage IV non-small cell lung cancer. J Bras Pneumol. 2018;44(6):505–509. doi: 10.1590/S1806-37562018000000023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Chamberlain C., Romundstad P., Vatten L., Gunnell D., Martin R.M. The association of weight gain during adulthood with prostate cancer incidence and survival: a population-based cohort. Int J Cancer. 2011;129(5):1199–1206. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Caan B.J., Kwan M.L., Shu X.O., et al. Weight change and survival after breast cancer in the after breast cancer pooling project. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2012;21(8):1260–1271. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-12-0306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Hess L.M., Barakat R., Tian C., Ozols R.F., Alberts D.S. Weight change during chemotherapy as a potential prognostic factor for stage III epithelial ovarian carcinoma: a Gynecologic Oncology Group study. Gynecol Oncol. 2007;107(2):260–265. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2007.06.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Dickerman B.A., Ahearn T.U., Giovannucci E., et al. Weight change, obesity and risk of prostate cancer progression among men with clinically localized prostate cancer. Int J Cancer. 2017;141(5):933–944. doi: 10.1002/ijc.30803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Ock C.Y., Oh D.Y., Lee J., et al. Weight loss at the first month of palliative chemotherapy predicts survival outcomes in patients with advanced gastric cancer. Gastric Cancer. 2016;19(2):597–606. doi: 10.1007/s10120-015-0481-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Sahin C., Omar M., Tunca H., et al. Weight loss at the time of diagnosis is not associated with prognosis in patients with advanced-stage non-small cell lung cancer. J BUON. 2015;20(6):1576–1584. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Kim S.I., Kim H.S., Kim T.H., et al. Impact of underweight after treatment on prognosis of advanced-stage ovarian cancer. J Immunol Res. 2014;2014 doi: 10.1155/2014/349546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Rock C.L., Thomson C.A., Sullivan K.R., et al. American Cancer Society nutrition and physical activity guideline for cancer survivors. CA Cancer J Clin. 2022;72(3):230–262. doi: 10.3322/caac.21719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Cho H.J., Song S., Kim Z., et al. Associations of body mass index and weight change with circulating levels of high-sensitivity C-reactive protein, proinflammatory cytokines, and adiponectin among breast cancer survivors. Asia Pac J Clin Oncol. 2023;19(1):113–125. doi: 10.1111/ajco.13779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Jackson S.E., Heinrich M., Beeken R.J., Wardle J. Weight loss and mortality in overweight and obese cancer survivors: a systematic review. PLoS One. 2017;12(1) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0169173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Nechuta S., Chen W.Y., Cai H., et al. A pooled analysis of post-diagnosis lifestyle factors in association with late estrogen-receptor-positive breast cancer prognosis. Int J Cancer. 2016;138(9):2088–2097. doi: 10.1002/ijc.29940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Parekh N., Chandran U., Bandera E.V. Obesity in cancer survival. Annu Rev Nutr. 2012;32:311–342. doi: 10.1146/annurev-nutr-071811-150713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Takada K., Kashiwagi S., Asano Y., et al. Clinical verification of body mass index and tumor immune response in patients with breast cancer receiving preoperative chemotherapy. BMC Cancer. 2021;21(1):1129. doi: 10.1186/s12885-021-08857-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Gupta A., Das A., Majumder K., et al. Obesity is independently associated with increased risk of hepatocellular cancer-related mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Clin Oncol. 2018;41(9):874–881. doi: 10.1097/COC.0000000000000388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Majumder K., Gupta A., Arora N., Singh P.P., Singh S. Premorbid obesity and mortality in patients with pancreatic cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;14(3):355–368. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2015.09.036. e; quiz e32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Han J., Zhou Y., Zheng Y., et al. Positive effect of higher adult body mass index on overall survival of digestive system cancers except pancreatic cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Biomed Res Int. 2017;2017 doi: 10.1155/2017/1049602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Greenlee H., Unger J.M., LeBlanc M., Ramsey S., Hershman D.L. Association between body mass index and cancer survival in a pooled analysis of 22 clinical trials. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2017;26(1):21–29. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-15-1336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Elkin P.L., Mullin S., Tetewsky S., et al. Identification of patient characteristics associated with survival benefit from metformin treatment in patients with stage I non-small cell lung cancer. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2022;164(5):1318–1326.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2022.02.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Imai H., Naito E., Yamaguchi O., et al. Pretreatment body mass index predicts survival among patients administered nivolumab monotherapy for pretreated non-small cell lung cancer. Thorac Cancer. 2022;13(10):1479–1489. doi: 10.1111/1759-7714.14417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.MJJ Voorn, Aerts L.P.A., Bootsma G.P., et al. Associations of pretreatment physical status parameters with tolerance of concurrent chemoradiation and survival in patients with non-small cell lung cancer. Lung. 2021;199(2):223–234. doi: 10.1007/s00408-021-00427-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Ryan A.M., Prado C.M., Sullivan E.S., Power D.G., Daly L.E. Effects of weight loss and sarcopenia on response to chemotherapy, quality of life, and survival. Nutrition. 2019;67-68 doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2019.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Kroenke C.H., Chen W.Y., Rosner B., Holmes M.D. Weight, weight gain, and survival after breast cancer diagnosis. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(7):1370–1378. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.01.079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Bradshaw P.T., Ibrahim J.G., Stevens J., et al. Postdiagnosis change in bodyweight and survival after breast cancer diagnosis. Epidemiology. 2012;23(2):320–327. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e31824596a1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Picon-Ruiz M., Morata-Tarifa C., Valle-Goffin J.J., Friedman E.R., Slingerland J.M. Obesity and adverse breast cancer risk and outcome: mechanistic insights and strategies for intervention. CA Cancer J Clin. 2017;67(5):378–397. doi: 10.3322/caac.21405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Carmichael A.R. Obesity and prognosis of breast cancer. Obes Rev. 2006;7(4):333–340. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2006.00261.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Protani M., Coory M., Martin J.H. Effect of obesity on survival of women with breast cancer: systematic review and meta-analysis. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2010;123(3):627–635. doi: 10.1007/s10549-010-0990-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Hanyuda A., Lee D.H., Ogino S., Wu K., Giovannucci E.L. Long-term status of predicted body fat percentage, body mass index and other anthropometric factors with risk of colorectal carcinoma: two large prospective cohort studies in the US. Int J Cancer. 2020;146(9):2383–2393. doi: 10.1002/ijc.32553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Wang S., Yang T., Qiang W., Zhao Z., Shen A., Zhang F. Benefits of weight loss programs for breast cancer survivors: a systematic reviews and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Support Care Cancer. 2022;30(5):3745–3760. doi: 10.1007/s00520-021-06739-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Harrington M., Gibson S., Cottrell R.C. A review and meta-analysis of the effect of weight loss on all-cause mortality risk. Nutr Res Rev. 2009;22(1):93–108. doi: 10.1017/S0954422409990035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.