Abstract

Purpose of review

Local hemodynamic factors are major determinants of the natural history of individual atherosclerotic plaque progression in coronary arteries. The purpose of this review is to summarize the role of low endothelial shear stress (ESS) in the transition of early, stable plaques to high-risk atherosclerotic lesions.

Recent findings

Low ESS regulates multiple pathways within the atherosclerotic lesion, resulting in intense vascular inflammation, progressive lipid accumulation, and formation and expansion of a necrotic core. Upregulation of matrix degrading proteases promotes thinning of the fibrous cap, severe internal elastic lamina fragmentation and extracellular matrix remodeling. In the setting of plaque-induced changes of the local ESS, coronary regions persistently exposed to very low ESS develop excessive expansive remodeling, which further exacerbates the proinflammatory low ESS stimulus. Recent studies suggest that the effect of recognized cardioprotective medications may be mediated by attenuation of the proinflammatory effect of the low ESS environment in which a plaque develops.

Summary

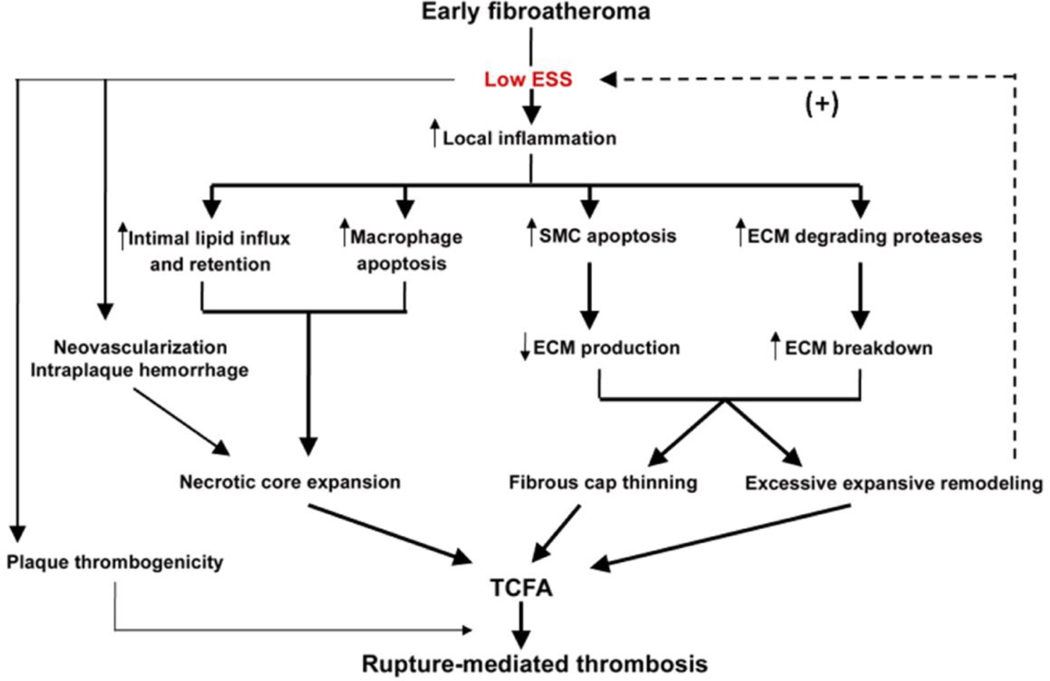

Low ESS determines the severity of vascular inflammation, the status of the extracellular matrix, and the nature of wall remodeling, all of which synergistically promote the transition of stable lesions to thin cap fibroatheromata that may rupture with subsequent formation of an occlusive thrombus and result in an acute coronary syndrome.

Keywords: coronary atherosclerosis, inflammation, extracellular matrix degrading enzymes, remodeling, shear stress

Introduction

Atherosclerosis is a systemic disease with heterogeneous manifestations. Lesions with various morphologies typically coexist in the coronary arteries of affected individuals (Figure 1). Early lesions may remain quiescent for long periods, evolve towards flow-limiting, fibro-calcific plaques that become clinically evident as stable angina, or develop a more inflamed phenotype. Only few among the many inflamed plaques develop a particularly unstable phenotype that renders them prone to rupture and consequently trigger an acute coronary event [2]. Fibrocalcific stable plaques may also evolve from subclinical plaque rupture and subsequent healing and fibrosis [3]. Increasing interest has focused on the mechanisms by which a subpopulation of early lesions transition to vulnerable, rupture-prone plaques. Early in-vivo identification of plaques destined to become vulnerable would be of enormous clinical value, as it would provide the rationale for intensive systemic pharmacologic treatment and possibly selective, prophylactic local interventions to avert future coronary events.

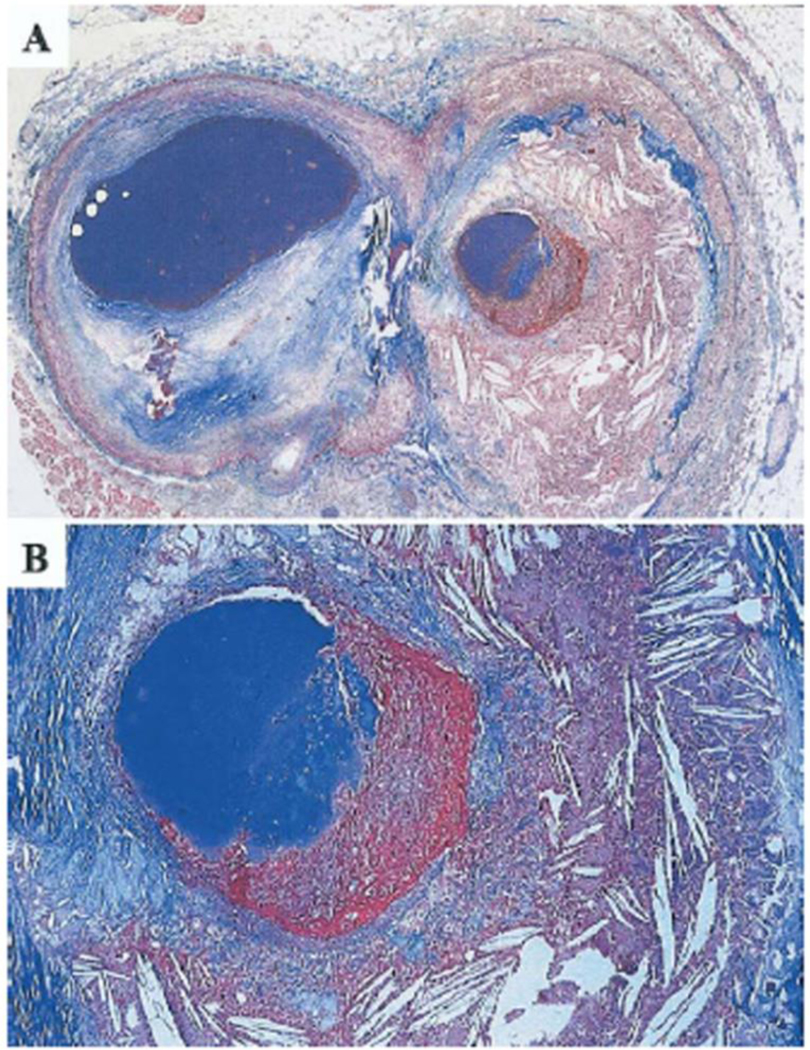

Figure 1. Atherosclerotic plaque heterogeneity within a human coronary artery.

A. Cross section of a human coronary artery just distal to a bifurcation. The atherosclerotic plaque to the left (circumflex branch) is fibrotic and partly calcified, whereas the plaque to the right (marginal branch) is lipid-rich with a non-occluding thrombus superimposed. B. Higher magnification of the plaque-thrombus interface reveals that the fibrous cap over the lipid-rich core is extremely thin, inflamed, and ruptured with a real defect in the cap. Trichrome stain, staining collagen blue and thrombus red. Reprinted from [1], with permission from Elsevier.

Despite the exposure of the entire coronary artery system to identical systemic risk factors, the distribution of atherosclerotic plaques [4], and particularly of high-risk plaques [5*,6*], is highly focal. Local hemodynamic factors related to disturbed flow patterns are responsible for the non-random susceptibility to atherosclerosis. Local flow properties exhibit remarkable heterogeneity over short distances, even in adjacent arterial regions, corresponding to the heterogeneity in the spatial distribution of atherosclerotic plaque [7,8]. Endothelial shear stress (ESS) is the tangential force per unit area exerted on the endothelial surface of the arterial wall by flowing blood. Local low ESS in particular determines proatherogenic endothelial cell (EC) morphologic and functional characteristics that induce local plaque formation [9]. Spatial gradients of ESS in geometrically irregular regions, as well as temporal shear stress gradients, have also been implicated in atherogenesis. Arterial regions of naturally occurring low ESS, such as branch points, bifurcations and inner surfaces of curvatures, are the regions primarily involved in atherogenesis and plaque progression [7,10,11,12]. Accumulating evidence now suggests that low ESS is a critical determinant not only of plaque formation and growth, but also of the transition of a developing plaque to a rupture-prone phenotype [13**].

The purpose of this review is to summarize the mechanisms linking low ESS with the transition of developing plaques to unstable, rupture-prone atheromata.

Morphologic features of unstable plaques

Plaque rupture with superimposed thrombosis is the predominant cause of acute coronary syndromes (ACS) and sudden coronary death, and may contribute to the progression of stable, fibrocalcific plaque. The thin-cap fibroatheroma (TCFA) is the typical precursor lesion of rupture-mediated thrombosis, accounting for about two thirds of ACS. The remaining coronary events are attributed to plaque erosion or calcified nodules [14]. TCFAs are characterized by a thin fibrous cap, measuring <65μm, overlying a large necrotic core. The fibrous cap is intensely inflamed particularly at its shoulders (Fig. 2A-D). TCFAs contain less collagen and fewer vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMC) and are more often located within expansively remodeled arterial segments, compared to lesions with a stable phenotype [14].

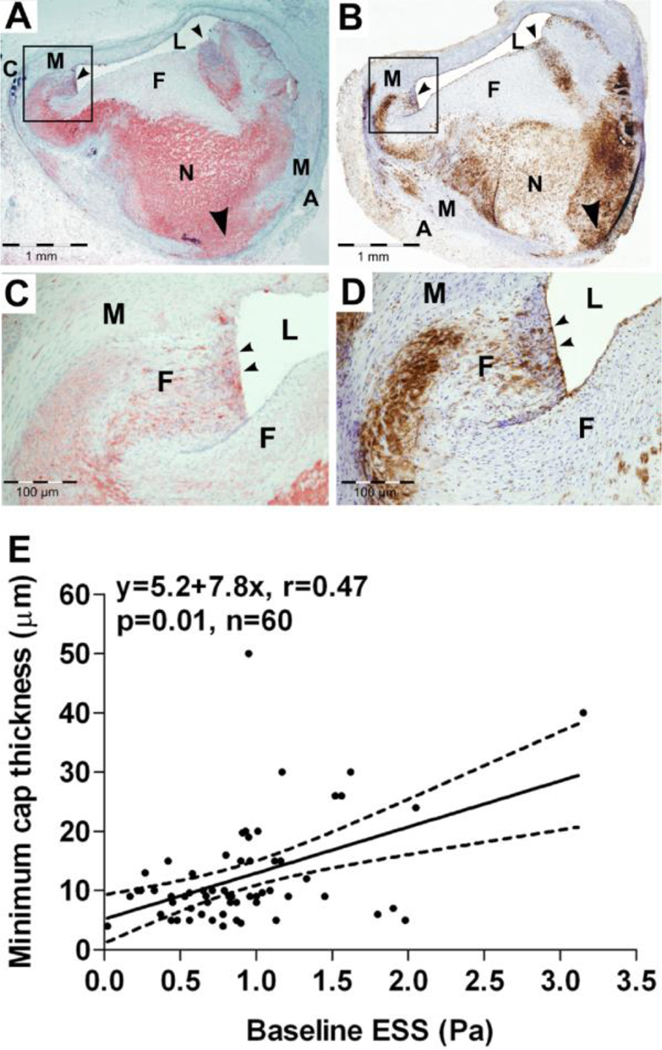

Figure 2. Role of low ESS in fibrous cap attenuation and the formation of thin cap fibroatheromata.

Digital photomicrographs of oil red O-stained (A and C) and CD45-stained (B and D) fibroatheroma from a porcine coronary artery, with a thin fibrous cap inflamed at its shoulders (small black arrowheads). L indicates lumen; M, media; A, adventitia; F, fibrous cap; N, necrotic core; and C, calcification. C and D are magnifications of the black box in A and B, respectively. The necrotic core is extended into the media through the disrupted IEL (A and B; large black arrowheads). L indicated lumen; M, media; A, adventitia; F, fibrous cap; N, necrotic core; C, calcification. E. Association of minimum cap thickness with the magnitude of baseline ESS; dashed lines represent 95% CI for the regression line. The arteries were snap frozen and not pressure fixed immediately after harvesting; the actual lumen dimensions can therefore not be accurately assessed, due to tissue shrinkage at −80oC. Reprinted from [13].

Endothelial shear stress as a determinant of plaque formation and localization

Extensive in-vitro work has elucidated the molecular basis of the flow-dependent, region-specific susceptibility to atherosclerosis. Shear stress is sensed by EC mechanoreceptors [15]. A complex system of mechanotransduction activates signaling pathways that modulate gene expression profiles [16], and ultimately evokes distinct EC phenotypes [17]. The transcription factor Krupell-like factor-2 (KLF2) orchestrates multiple shear-responsive atheroprotective genes under favorable flow conditions [18,19]. Atheroprotective flow also upregulates Nrf2-dependent antioxidant genes [20]. The mitogen-activated protein kinase phosphatase (MKP)-1, a negative regulator of p38 and JNK, is a critical mediator of the anti-inflammatory effects of physiologic values of ESS [21*]. In contrast, low ESS mutes the effect of KLF2 and induces the transcriptional regulator nuclear factor-kappa B (NF-κB), which promotes pro-inflammatory gene and protein expression [22,23**]. Overall, the low ESS-induced EC changes convert biomechanical forces to biochemical responses, enhancing the formation of an early atherosclerotic lesion.

Role of low endothelial shear stress in the destabilization of progressing plaques

The extent of the maladaptive local inflammatory response to the subendothelial accumulation of apolopoprotein B-containing lipoproteins critically influences the subsequent differentiation of an early lesion. In the setting of local low ESS, the predominance of inflammation, cell death and extracellular matrix (ECM) degradation over ECM synthesis and fibroproliferation, largely determines the transition of a subpopulation of early lesions to rupture-prone plaques.

Upregulation of local vascular inflammation

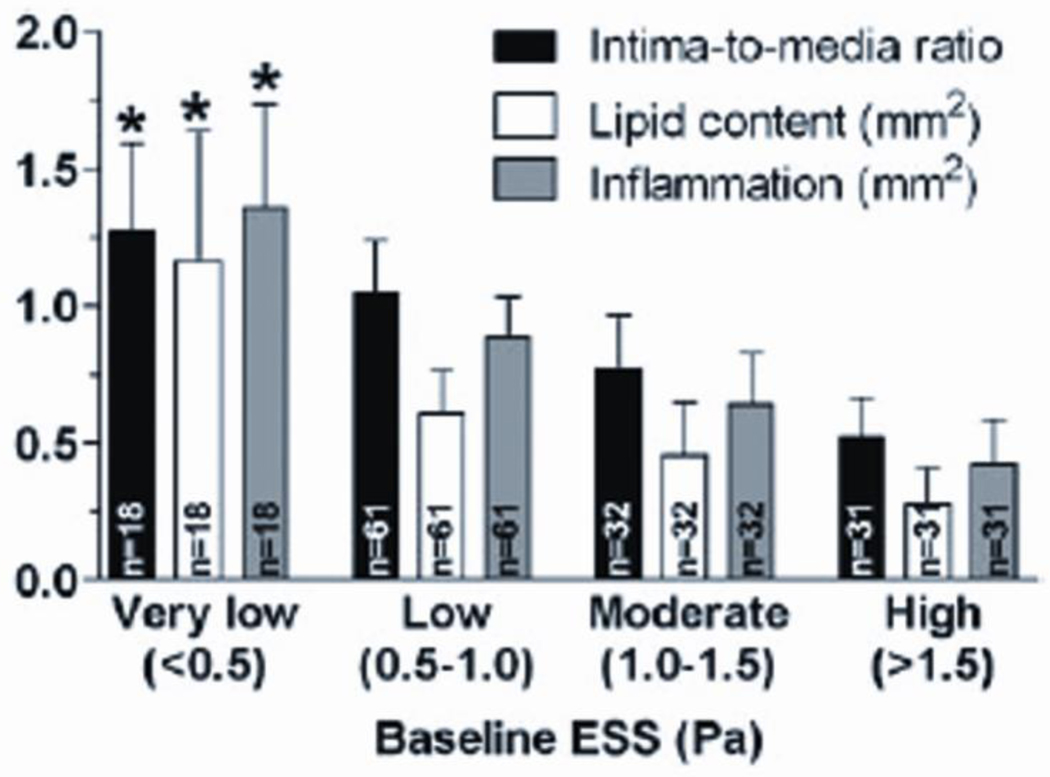

Low ESS exerts a key role in the ongoing recruitment of circulating inflammatory cells into the vessel wall, where they differentiate to potent sources of pro-inflammatory mediators [24]. NF-Κb induces the expression of adhesion molecules (ICAM-1, VCAM-1, E-selectin), chemoattractant chemokines, such as monocyte chemoattractant protein (MCP)-1, and proinflammatory cytokines (TNF-α, IL-1, and IFN-γ) [7,22,25]. Adhesion molecules facilitate the adhesion of circulating leukocytes to the endothelial surface, whereas MCP-1 promotes their transmigration into the intima. In-vivo experimental studies have confirmed that low ESS indeed fosters an inflamed plaque phenotype, consistent with the abundance of in-vitro evidence. In a mouse carotid artery model of induced flow pattern variations, regions exposed to low ESS developed vulnerable lesions, with increased expression of VCAM-1, ICAM-1, interleukin-6 [26] and chemokines, predominantly fraktalkine [27]. Our group recently demonstrated that the extent of inflammatory cell infiltration is related in a dose-dependent manner to the magnitude of the preceding low ESS, utilizing a well-established diabetic hyperlipidemic swine model of atherosclerosis (Figure 3) [13**]. This natural history study clearly indicated that highly inflamed TCFAs exclusively develop in sites of preceding low ESS.

Figure 3. Association of the magnitude of low ESS with the severity of high-risk plaque characteristics.

Association of ESS magnitude at baseline (week 23) with the severity of high-risk plaque characteristics at follow-up (week 30), in a diabetic, hyperlipidemic model of atherosclerosis. *: p<0.05 for each characteristic in very low ESS vs. the respective characteristic in moderate or high ESS; p=0.13 for inflammation in very low ESS vs. low ESS. Reprinted from [13].

Subendothelial lipid retention and expansion of the necrotic core

Necrotic core expansion is a key factor of lesion destabilization [14]. Plaque progression rate is determined by the dose-responsive, synergistic effect of systemic hyperlipidemia and local low ESS [28**]. Low ESS colocalizes with elevated luminal surface LDL cholesterol concentration, thereby locally exposing the endothelium to maximal lipoprotein levels [29*]. Increased permeability of endothelial cells to lipoproteins [30], widening of intercellular junctions [7,31] and the upregulation of LDL receptors [32] potentiate intracellular lipid influx in fibroatheromata developing in a low ESS milieu. Furthermore, low ESS-induced proinflammatory cytokines, oxidative stress, and activation of the Fas ligand promote macrophage apoptosis. When inflammation prevails in the intima, the apoptotic process is not properly coupled with phagocytic clearance (efferocytosis); as a result, accumulating necrotic debris contributes to the expansion of the necrotic core [33**]. Intimal neovascularization is also critical in promoting plaque progression and instability [34*]. Neovessels may serve as conduits for the extravasation of inflammatory cells, and erythrocyte membrane-derived cholesterol and proinflammatory interleukines into the core [35*,36*]. Low ESS may contribute to plaque neovascularization by promoting intimal thickening with resulting local hypoxia, a potent angiogenic stimulus [37], and by upregulating the expression of the angiogenic factor VEGF [26].

Extracellular matrix degradation

The status of the ECM is regulated by the balance between macromolecule synthesis and enzymatic breakdown. Collagenases degrade the major plaque-stabilizing structural protein, i.e. interstitial collagen. Elastases break down elastin fibers, facilitating the migration of macrophages and VSMC and promoting arterial remodeling [38]. Recent work has shown that the activation of JNK, a regulator of flow-responsive inflammatory gene expression, is modulated by ECM remodeling [39*], suggesting a positive feedback pathway by which inflammation-driven matrix remodeling further augments the endothelium-dependent vascular inflammation. In-vitro studies have associated low ESS with the upregulation of matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) [40] and cathepsins [41]. Mohler et al determined time-dependent patterns in the expression of genes implicated in porcine coronary plaque progression, and found that MMP-9 was remarkably upregulated at advanced stages of plaque evolution [42**]. Our group further showed a lesion-specific, ESS-related variability in the expression of ECM catabolizing enzymes. Exposure to very low ESS induced the activity of MMP-2, 9, 12, and cathepsins K, L, and S relative to their endogenous inhibitors, ultimately resulting in the formation of TCFAs [43**]. Minimum cap thickness in these TCFAs was related to the magnitude of baseline ESS (Figure 2E). These in-vivo investigations clearly demonstrated that low ESS-induced ECM degradation promotes matrix remodeling and thinning of the fibrous cap, both critical steps in rendering a plaque rupture-prone.

Heparan sulfate proteoglycans

Recent evidence suggests a role of low ESS in the enzymatic regulation of matrix glycosaminoglycans. Proteoglycans can alter subendothelial lipid deposition and retention. While proteoglycans with predominantly chondroitin and dermatan sulfate chains display increased affinity to atherogenic lipoproteins [44], heparan sulfate proteoglycans are considered anti-atherogenic due to their potential to inhibit LDL binding [45] and monocyte adhesion [46]. Heparanase-mediated removal of heparan sulfate chains from ECM proteins facilitates proteolyic digestion by MMPs [47]. We recently found that heparanase was upregulated in coronary segments that were exposed to low ESS and evolved to TCFAs; notably, heparanase colocalized with inflammatory cells, lipid deposition and MMPs expression (Figure 4) [48**]. Overall, heparanase may be a powerful regulator of plaque progression and may act in concert with MMPs in the degradation of the ECM under low ESS conditions.

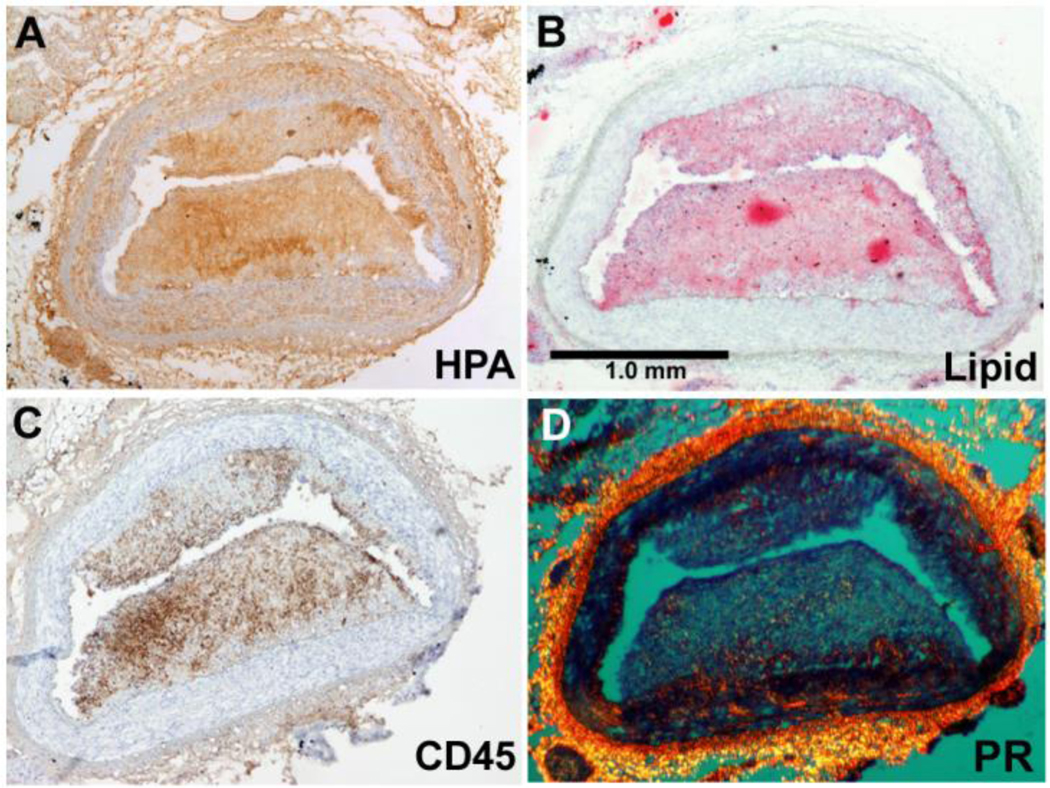

Figure 4. Colocalization of heparanase with lipids and inflammatory cells in a coronary region of low ESS.

Figure from a porcine coronary artery section, showing a thin cap fibroatheroma that developed in a coronary region of preceding low ESS. Note that immunostaining for heparanase (HPA, A) co-localizes with staining oil-red O (lipids, B), and immunostaining with CD45 (inflammatory cells, C). Satining with picrosirius red (PR, D) indicates collagen and reveals the thin fibrous cap overlying the necrotic core.

Smooth muscle cell migration and apoptosis

Inflammatory mediators including IFN-γ, FasL, TNF-α, and reactive oxygen species can activate caspases and elicit mitochondrial dysfunction and apoptosis of VSMCs [49], resulting in a likely decrease in the number of SMCs in TCFAs [14]. Low ESS promotes VSMC migration from the media to the intima through upregulation of the SMC mitogens platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF)-A and -B [50], endothelin-1 [51], and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) [26]. However, low ESS also induces VSMC apoptosis, mediated by the downregulation of protein-Rho-GDP dissociation inhibitor alpha (Rho-GDIa), a modulator of Rho family signal transduction [52*]. The apoptotic death of this major cellular source for the renewal of the fibrous cap’s collagen may represent a further mechanism of plaque destabilization. Furthermore, VSMC exert an anti-apoptotic effect on macrophages and monocytes [53], such that VSMC apoptosis may indirectly facilitate apoptosis of inflammatory cells and thus cause an increase in the size of the necrotic core.

Effect of low ESS on arterial remodeling

The arterial wall dynamically responds to plaque formation. The nature of the wall’s remodeling, regulated by systemic, genetic, and local hemodynamic factors, can range from constrictive to compensatory expansive to excessive expansive [54]. Expansively remodeled coronary plaques are associated with increased inflammation [55] and unstable clinical presentation [56]. Interestingly, Okura at al reported that the remodeling pattern of ACS culprit lesions may be a better predictor of long term (3-year) clinical outcome than the presence of plaque rupture [57**]. A dynamic interplay between the local ESS and the vascular remodeling is a critical determinant of the natural history of an individual lesion [2]. We recently showed that regions culminating in high-risk excessive expansive remodeling had been exposed to very low ESS throughout their natural history, utilizing serial, in-vivo vascular profiling of porcine coronary arteries at five consecutive time points [58**] (Figure 5). In the setting of plaque-induced changes of the local geometry and thereby of local flow waveforms, only a small subpopulation of developing atheromata are located in a persistently low ESS milieu, related to the magnitude of low ESS and, consequently, the magnitude of intense inflammation. The elaboration of matrix-degrading proteases, with subsequent elastolysis in the internal elastic laminae and the media beneath the plaque, are critical in promoting aneurysm-like expansion of the highly inflamed wall, and turning the ostensibly protective function of compensatory remodeling into a detrimental local environment [13**]. Local excessive expansive remodeling contributes to further lowering of the low ESS, thus reinforcing the vicious cycle of the intense pro-inflammatory stimulus and ultimately promoting the evolution of an early atheroma to a TCFA.

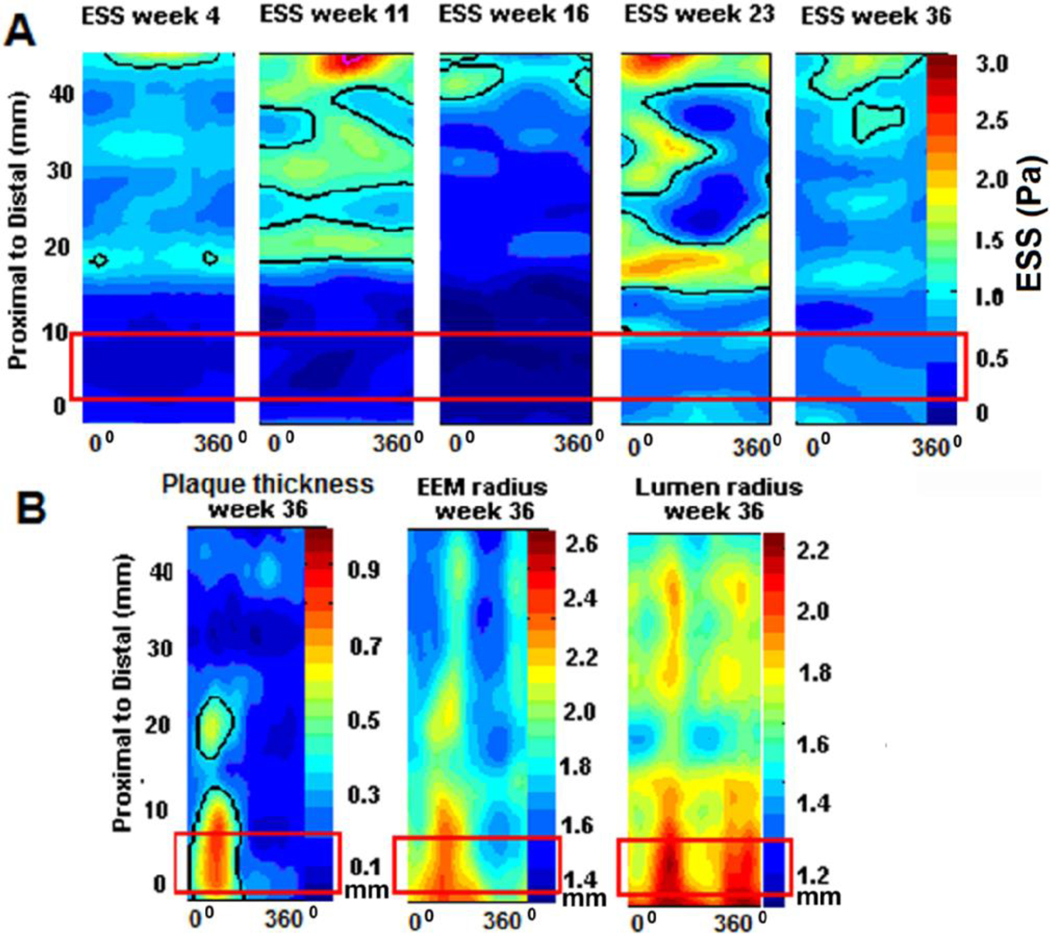

Figure 5. Effect of persistently low ESS in the formation of expansively remodeled atherosclerotic plaque.

Representative example of a serially profiled porcine coronary artery. A. Two-dimensional maps show the ESS distribution along the artery length at five cosecutive time points of in-vivo vascular profiling at weeks 4, 11, 16, 23, and 36 after the induction of diabetes and hyperlipidemia. In each map, the horizontal axis denotes the artery circumference (°) and the vertical axis the artery length (mm). The red rectangle denotes a proximal segment which is peristently exposed to low ESS, throughout its natural history. B. Two-dimensional maps showing the plaque thickness, external elastic lamina radius and lumen radius distribution along the artery length at final week 36; in each map, the horizontal axis denotes the artery circumference (°) and the vertical axis the artery length (mm). Red rectangles include the same proximal segmet, as in figure A. This arterial segment displays maximal plaque thickness, and also significant expansion of the vessel wall, as indicated by the orange-red color in the corresponding maps. Note that even the lumen exhibits maximal expansion, despite the formation of significant plaque, indicating excessive expansive remodeling, i.e. an exagerrated, aneurysm-like form of arterial remodeling that not only preserves normal lumen dimensions, but actually causes lumen increase under the effect of sufficiently low ESS.

Thrombogenicity of the necrotic core

Low ESS augments the thrombogenicity of the necrotic core and thus the extent of thrombosis in the event of acute plaque disruption. Low ESS-induced macrophage accumulation and SMC apoptosis are sources of tissue factor, a potent procoagulant factor [59]. While atheroprotective flow-activated KLF2 induces thrombomodulin and endothelial nitric oxide synthase expression and reduces plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 and tissue factor expression, muting of KLF2 shifts the balance towards a prothrombotic state [60].

Plaque-induced changes of local ESS

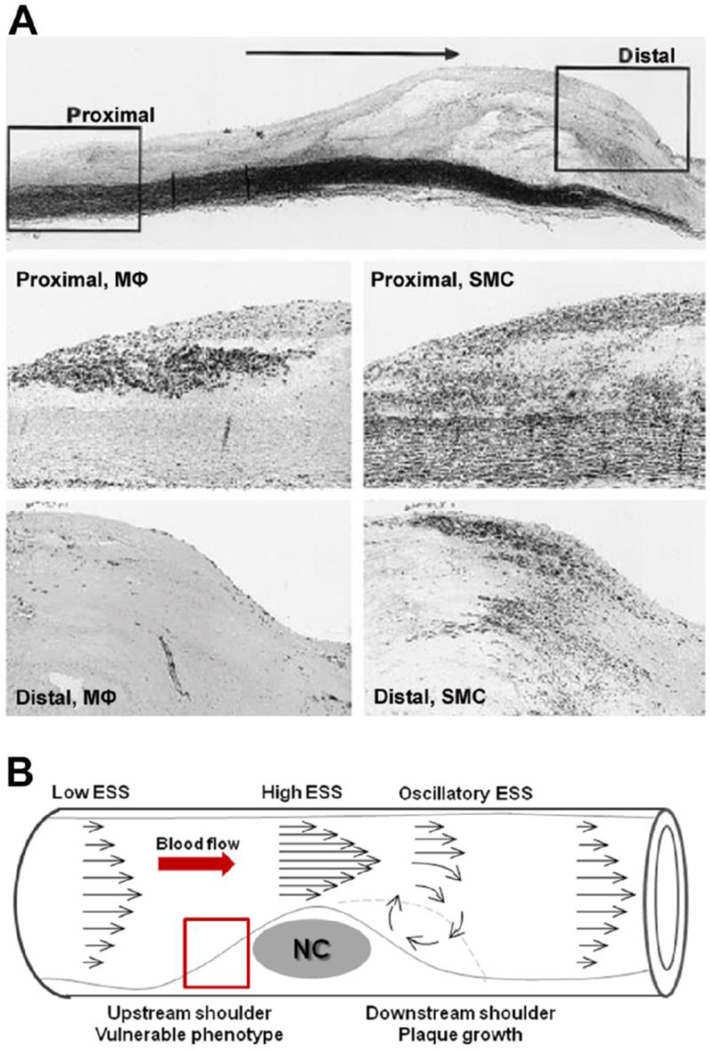

The magnitude, directionality, and spatial distribution of local shear stress all change in response to the changes of local arterial geometry induced by a growing plaque. Thus, a developing plaque itself can modify the local ESS milieu in specific parts of, and adjacent to the lesion. Lumen narrowing due to a stenotic plaque results in increased flow velocity at the throat of the plaque, low ESS in the upstream region, and disturbed flow in the form of directionally oscillatory ESS in the downstream shoulder of the plaque [61]. The composition of an individual plaque displays considerable spatial heterogeneity. The downstream region contains significantly more smooth muscle cells, whereas the upstream portion is more inflamed, containing high number of macrophages [62] and expressing higher gelatinolytic activity [63]. Cheng et al showed in a mouse model that regions exposed to low ESS upstream of a perivascular shear stress modifier exhibited the most profound development of highly inflamed, vulnerable carotid plaques, whereas stable lesions formed in the downstream vortices of lowered/oscillatory ESS [26]. Overall, the plaque-induced changes of local ESS seem to exert a differential effect in distinct portions of a stenotic lesion and critically affect the longitudinal distribution of plaque morphology; a self-perpetuating local environment conducive to further plaque growth is established downstream of the lesion, whereas a vulnerable, rupture-prone phenotype develops in the low ESS upstream shoulder (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Association between longitudinal atherosclerotic plaque morphology and spatial distribution of local ESS.

A. Top: histologic appearance of a human carotid artery plaque stained with Elastic–van Gieson. Horizontal arrow indicates direction of blood flow. Box on the left indicates proximal (upstream) shoulder of plaque; box on the right represents the distal (downstream) shoulder. Middle: boxed area of proximal shoulder stained with anti-CD68 (macrophages; MΦ) and anti–a-actin (smooth muscle cell, SMC). Bottom: boxed area of distal shoulder stained with anti-CD68 (macrophages; MΦ) and anti–a-actin (smooth muscle cell, SMC). Note the abundance of macrophages in the upstream shoulder, and of smooth muscle cells in the downstream shoulder, respectively. Modified from [62]. B. Differential spatial distribution of ESS along a lumen protruding plaque. Arrows pepresent velocity vectors. The upstream shoulder is exposed to low ESS. Local ESS is elevated in the throat, and low / oscillatory in the downstream shoulder of the developing plaque. These local ESS conditions promote the formation of a vulnerable, plaque-prone phenotype, indicated by the red rectangle, upstream of the lesion, and additional growth, indicated by the dashed line, downstream of the plaque. NC: necrotic core.

Plaque rupture represents the most devastating complication of atherosclerotic disease. Frank plaque rupture may be related to low ESS-mediated inflammation and matrix degradation culminating in severe plaque fragility and severe proclivity to rupture from simple daily hemodynamic stresses [64]. It has also been postulated that localized high shear stress may actually trigger fibrous cap rupture [65,66,67]. Because the values of wall shear stress are markedly lower than the values of blood pressure-induced tensile stress in the plaque cap, it is unlikely that high wall shear stress contributes significantly to the direct mechanical failure of the cap. However, high ESS may induce pathobiologic responses within the plaque that also exacerbate plaque fragility, as suggested by the reported association of regions with high ESS with high strain, a presumed surrogate marker of vulnerable plaque composition [68,69]. Further, high ESS may be implicated in local endothelial erosion, increased platelet adhesion, and induction of acute coronary thrombosis [7].

Effect of anti-atherosclerotic medications on the proinflammatory effect of low ESS

The plaque-stabilizing effect of recognized anti-atherosclerotic drugs may, at least in part, be mediated by the attenuation of the proinflammatory low ESS environment of high-risk plaques, indirectly emphasizing the critical role of low ESS in plaque destabilization. We have shown that lifetime administration of valsartan in a diabetic, hyperlipidemic swine model, alone or in combination with simvastatin, attenuated the pro-inflammatory effect of local low ESS. These medications reduced the expression of MMP-9, which is actively involved in the ECM degradation, as well as the MMP/TIMP ratio, thereby shifting the ECM balance towards less degradation, and limiting the severity of expansive remodeling. The beneficial effect of valsartan and simvastatin in reducing the severity of inflammation and stabilizing high-risk plaque characteristics in regions of low ESS was independent of a blood pressure- and lipid-lowering effect [70**]. Statins in particular are potent promoters of the atheroprotective regulator KLF2, and up-regulate several of its downstream transcriptional targets [71]. Statins may thereby exert their well described non-lipid lowering vasculoprotective effects by counterbalancing the proatherogenic effect of low ESS on the KLF2-regulated genes cassette.

Clinical perspectives of the in-vivo assessment of ESS

As discussed above low ESS is a major determinant of vascular pathology and clearly plays a critical role in rendering a subpopulation of developing atheromata prone to rupture. A sophisticated computational model by Ohayon et al recently showed that the proclivity for acute plaque disruption is not determined by fibrous cap thickness alone, but rather by a combination of cap thinning, necrotic core thickness, and expansive arterial remodeling [72**]. These high-risk morphologic features are all exacerbated in plaques that progress in a low ESS setting (Figure 7).

Figure 7. Role of low ESS in the formation of rupture-prone plaque.

Schematic presentation of the mechanisms whereby low local ESS promotes the conversion of an early fibroatheroma to a thin cap fibroatheroma, major precursor lesion of rupture-mediated thrombosis.

Despite major advances in prevention and treatment, the thrombotic complications of atherosclerotic disease remain a major cause of mortality. Residual cardiovascular morbidity is observed despite the aggressive pharmacologic treatment in high-risk patients [73], and despite the addition of coronary interventions to optimal medical therapy [74]. Major cardiac events occur in non-target lesions following successful interventions [75], clearly indicating the inadequacy of currently applied methodologies to predict and adequately target plaques that eventually culminate in acute coronary events. Coronary interventions are currently employed either to treat ACS culprit lesions, or to restore flow in obstructive, flow-limiting plaques, thereby ignoring a large proportion of minimally stenotic TCFAs, potential precursors of ACS. Although several imaging techniques have been proposed to assess morphologic or functional characteristics of rupture-prone plaques before they rupture, no widely accepted diagnostic method to prospectively identify such high-risk plaques is available at present.

Knowledge of local flow patterns and identification of arterial regions with naturally occurring low ESS cannot currently prompt interventions in native anatomy to prevent atherosclerosis or atherosclerotic sequelae. However, in-vivo identification of coronary regions of low ESS and expansive remodeling, utilizing catheterization-based [10], or non-invasive techniques of vascular profiling [76**], may be predictive of future high-risk plaque formation and can be used to risk-stratify individual lesions that have, or are likely to acquire, characteristics of vulnerability [77**]. The early characterization of a coronary region most likely to progress to a rupture-prone phenotype may enable primary prevention at the level of individual atherosclerotic plaque, and thereby provide the rationale for focused systemic or local treatments to avert future coronary events. Established systemic approaches and novel therapeutic targets may be employed to impede or even reverse the progression towards vulnerable plaques and stabilize high-risk plaque characteristics. Furthermore, regional therapy of high-risk plaque in the form of highly selective, prophylactic coronary interventions may be justified to “eradicate” plaques destined to become vulnerable. The association of drug-eluting stents [78**,79**], drug-coated balloon catheters [80**], and more recently of bioabsorbable everolimus-eluting stents [81] with a lower risk of coronary in-stent restenosis or stent thrombosis may render pre-emptive stenting of high-risk plaques plausible. A large-scale clinical natural history study (the PREDICTION trial) is currently underway to investigate whether coronary segments with low ESS and expansive remodeling are the regions that result in rapid progression of atherosclerosis and eventually in plaque rupture. This study may validate the predictive value of vascular profiling for the accurate risk stratification of early coronary plaques, and thereby potentially change the paradigm for management of patients with coronary artery disease.

Conclusions

Low ESS regulates multiple pathways that synergistically induce plaque destabilization. Low ESS upregulates local inflammation, promotes reduced synthesis and increased catabolism of extracellular matrix macromolecules, and elicits excessive expansive wall remodeling, a high-risk remodeling pattern that further exacerbates the adverse low ESS stimulus. Early lesions persistently exposed to low ESS may thereby progress towards highly inflamed TCFAs. The in-vivo measurement of ESS may be used for the early identification of lesions that are likely to acquire a rupture-prone phenotype and trigger coronary thrombosis. Early identification of high-risk plaques before they become vulnerable may set the stage for focused systemic treatments or prophylactic local interventions to avert future coronary events.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Prof. George D. Giannoglou for his encouragement and support.

Funding sources:

This work was supported by grants from Boston Scientific Inc., the Novartis Pharmaceuticals Inc., the George D. Behrakis Research Fellowship, the Onassis Foundation, the Hellenic Harvard Foundation, the Hellenic Atherosclerosis Society, the AG Leventis Foundation, the Propondis Foundation, and the National Institutes of Health R01 GM 49039 (to ERE).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Falk E. Pathogenesis of atherosclerosis. J Am Coll Cardiol 2006;47:C7–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chatzizisis YS, Coskun AU, Jonas M, et al. Role of endothelial shear stress in the natural history of coronary atherosclerosis and vascular remodeling: molecular, cellular and vascular behavior. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;49:2379–2393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Burke AP, Kolodgie FD, Farb A, et al. Healed plaque ruptures and sudden coronary death: evidence that subclinical rupture has a role in plaque progression. Circulation 2001;103:934–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Asakura T, Karino T. Flow patterns and spatial distribution of atherosclerotic lesions in human coronary arteries. Circ Res 1990;66: 1045–1066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Tanaka A, Imanishi T, Kitabata H, et al. Distribution and frequency of thin-capped fibroatheromas and ruptured plaques in the entire culprit coronary artery in patients with acute coronary syndrome as determined by optical coherence tomography. Am J Cardiol 2008;102:975–979 * This clinical, optical coherence tomography study demonstrated in-vivo the proximal distribution of TCFAs.

- 6. Hong MK, Mintz GS, Lee CW, et al. A three-vessel virtual histology intravascular ultrasound analysis of frequency and distribution of thin-cap fibroatheromas in patients with acute coronary syndrome or stable angina pectoris. Am J Cardiol 2008;101:568–572 *This three-vessel human study demonstrated the proximal localization of TCFAs, identified by virtual histology.

- 7.Malek AM, Alper SL, Izumo S. Hemodynamic shear stress and its role in atherosclerosis. JAMA 1999;282:2035–2042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Richter Y, Edelman ER. Cardiology Is Flow. Circulation 2006;113:2679–2682 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gimbrone MA Jr., Topper JN, Nagel T, et al. Endothelial dysfunction, hemodynamic forces, and atherogenesis. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2000;902:230–239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stone PH, Coskun AU, Kinlay S, et al. Effect of endothelial shear stress on the progression of coronary artery disease, vascular remodeling, and in-stent restenosis in humans: in vivo 6-month follow-up study. Circulation 2003;108:438–444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stone PH, Coskun AU, Kinlay S, et al. Regions of low endothelial shear stress are sites where coronary plaque progress and vascular remodeling occurs in humans: an in-vivo serial study. Eur Heart J 2007:28:705–710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Giannoglou GD, Soulis JV, Farmakis TM, et al. Haemodynamic factors and the important role of local low static pressure in coronary wall thickening. Int J Cardiol 2002; 86:27–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Chatzizisis YS, Jonas M, Coskun AU, et al. Prediction of the localization of high risk coronary atherosclerotic plaques on the basis of low endothelial shear stress: an intravascular ultrasound and histopathology natural history study. Circulation 2008;117:993–1002. ** This intravascular ultrasound and histopathology study in porcine coronary arteries showed that the magnitude of low ESS determines the localization and heterogeneity of atherosclerotic lesions, and predicts the development of TCFAs.

- 14.Virmani R, Burke AP, Farb A, Kolodgie FD. Pathology of the vulnerable plaque. J Am Coll Cardiol 2006; 47:C13–C18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lehoux S, Castier Y, Tedgui A. Molecular mechanisms of the vascular responses to haemodynamic forces. J Intern Med 2006;259: 381–392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.García-Cardeña G, Comander JI, Blackman BR, et al. Mechanosensitive endothelial gene expression profiles: scripts for the role of hemodynamics in atherogenesis? Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2001;947:1–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mott RE, Brian P. Helmke BP. Mapping the dynamics of shear stress-induced structural changes in endothelial cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 2007; 293: C1616–C1626 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dekker RJ, Boon RA, Rondaij MG, et al. KLF2 provokes a gene expression pattern that establishes functional quiescent differentiation of the endothelium. Blood 2006; 107:4354–4363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Parmar KM, Larman HB, Dai G, et al. Integration of flow-dependent endothelial phenotypes by Kruppel-like factor 2. J Clin Invest 2006; 116:49–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dai G, Vaughn S, Zhang Y, et al. Biomechanical forces in atherosclerosis-resistant vascular regions regulate endothelial redox balance via phosphoinositol 3-kinase/Akt-dependent activation of Nrf2. Circ Res. 2007;101(7):723–733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Zakkar M, Chaudhury H, Sandvik G, et al. Increased endothelial Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase Phosphatase-1 expression suppresses proinflammatory activation at sites that are resistant to atherosclerosis. Circ Res. 2008;103:726–732. * The in-vitro investigation showed that MAP kinase phosphatase (MKP)-1 is required for the anti-inflammatory effects of atheroprotective shear stress.

- 22.Orr AW, Sanders JM, Bevard M, et al. The subendothelial extracellular matrix modulates NF-kappaB activation by flow: a potential role in atherosclerosis. J Cell Biol 2005;169:191–202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Gareus R, Kotsaki E, Xanthoules S, et al. Endothelial cell-specific NF-kappaB inhibition protects mice from atherosclerosis. Cell Metab 2008;8(5):372–383. ** This experimental study confirmed in-vivo that NF-kappaB regulates proinflammatory gene expression and promotes atherosclerosis.

- 24.Cicha I, Goppely-Struebe M, Yilmaz, et al. Endothelial dysfunction and monocyte recruitment in cells exposed to non-uniform shear stress. Clin Hemorheol Microcirc 2008;39(1–4):113–119 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Matharu NM, McGettrick HM, Salmon M, et al. Inflammatory responses of endothelial cells experiencing reduction in flow after conditioning by shear stress. J Cell Physiol. 2008; 216(3):732–741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cheng C, Tempel D, van Haperen R, et al. Atherosclerotic lesion size and vulnerability are determined by patterns of fluid shear stress. Circulation 2006;113:2744–2753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cheng C, Tempel D, van Haperen R, et al. Shear stress-induced changes in atherosclerotic plaque composition are modulated by chemokines. J Clin Invest 2007; 117(3): 616–626 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Chatzizisis YS, Koskinas K, Jonas M, et al. Differential atherosclerotic vascular response to local endothelial shear stress based on the severity of hyperlipidemia [abstract]. Atherosclerosis Supplement 2009; 10(2). ** This serial, in-vivo intravascular ultrasound investigation in swine coronary arteries showed the synergistic effect of systemic hypercholesterolemia and local low ESS in determining the natural history of individual plaque.

- 29. Soulis JV, Giannoglou GD, Papaioannou V, et al. Low-density lipoprotein concentration in the normal left coronary artery tree. BioMedical Engineering OnLine 2008, 7:26. * This computational study showed that the concentration of low density lipoprotein at the luminal surface is higher in regions of low shear stress.

- 30.Himburg HA, Grzybowski DM, Hazel AL, et al. Spatial comparison between wall shear stress measures and porcine arterial endothelial permeability. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2004;286:H1916–1922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Molecular Chien S. and mechanical bases of focal lipid accumulation in arterial wall. Prog Biophys Mol Biol 2003;83:131–151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liu Y, Chen BP, Lu M, et al. Shear stress activation of SREBP1 in endothelial cells is mediated by integrins. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2002;22:76–81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Seimon T, Tabas I. Mechanisms and consequences of macrophage apoptosis in atherosclerosis. J Lipid Res. 2009;50:S382–S387 ** This comprehensive review summarizes current knowledge on the differential role of apoptotic macrophages in early vs. advanced atherosclerotic lesions, and the underlying mechanisms of macrophage death during atherosclerosis.

- 34. Sluimer JC, Kolodgie FD, Bijnens AP, et al. Thin-walled microvessels in human coronary atherosclerotic plaques show incomplete endothelial junctions relevance of compromised structural integrity for intraplaque microvascular leakage. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;53(17):1517–1527. ** This human histopathology study revealed increased microvessel density and compromised structural integrity of the microvascular endothelium in advanced human atherosclerotic plaques.

- 35. Giannoglou GD, Koskinas KC, Tziakas D, et al. Total cholesterol content of erythrocyte membranes and coronary atherosclerosis. An intravascular ultrasound pilot study. Angiology 2009. June 17 [Epub ahead of print] * This human IVUS study showed for the first time in-vivo that erythrocyte membrane-derived cholesterol is associated with coronary plaque burden.

- 36. Tziakas DN, Chalikias GK, Tentes IK, et al. Interleukin-8 is increased in the membrane of circulating erythrocytes in patients with acute coronary syndrome. Eur Heart J. 2008; 29(22):2713–2722. * This human study showed that interleukin-8 contained in erythrocyte membranes may contribute to coronary plaque instability.

- 37.Kolodgie FD, Narula J, Yuan C, et al. Elimination of neoangiogenesis for plaque stabilization: is there a role for local drug therapy? J Am Coll Cardiol 2007; 49:2093–2101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Libby P. The molecular mechanisms of the thrombotic complications of atherosclerosis. J Intern Med. 2008. May ; 263(5): 517–527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Hahn C, Orr AW, Sanders JM, et al. The subendothelial extracellular matrix modulates JNK activation by flow. Circ Res. 2009;104:995–1003. * This experimental study identified JNK as a matrix-specific, flow-activated inflammatory regulator.

- 40.Sun HW, Li CJ, Chen HQ, et al. Involvement of integrins, MAPK, and NF-kappaB in regulation of the shear stress-induced MMP-9 expression in endothelial cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2007;353:152–158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Platt MO, Ankeny RF, Shi GP, et al. Expression of cathepsin K is regulated by shear stress in cultured endothelial cells and is increased in endothelium in human atherosclerosis. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2007;292:H1479–1486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Mohler ER 3rd, Sarov-Blat L, Shi Y, et al. Site-specific atherogenic gene expression correlates with subsequent variable lesion development in coronary and peripheral vasculature. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2008;28:850–855 ** This in-vivo study investigated swine coronary and peripheral arteries, and associated temporal and spatial variations of gene expression with variable plaque development and progression.

- 43. Chatzizisis YS, Baker A, Beigel R, et al. Low endothelial shear stress upregulates extracellular matrix degrading enzymes and promotes the formation of thin cap fibroatheromas in the coronary arteries [abstract]. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2008;28:e44 ** This in-vivo IVUS and histopathology investigation of porcine coronary arteries revealed the low shear stress-mediated upregulation of matrix degrading enzymes as a critical step in the formation of thin cap fibroatheromata.

- 44.Wight TN, Merrilees MJ. Proteoglycans in atherosclerosis and restenosis: key roles for versican. Circ Res. 2004; 94: 1158–1167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pillarisetti S, Paka L, Obunike JC, et al. Subendothelial retention of lipoprotein (a). Evidence that reduced heparan sulfate promotes lipoprotein binding to subendothelial matrix. J Clin Invest. 1997; 100: 867–874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sivaram P, Obunike JC, Goldberg IJ. Lysolecithin-induced alteration of subendothelial heparan sulfate proteoglycans increases monocyte binding to matrix. J Biol Chem. 1995; 270: 29760–29765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Munesue S, Yoshitomi Y, Kusano Y, et al. A novel function of syndecan-2, suppression of matrix metalloproteinase-2 activation, which causes suppression of metastasis. J Biol Chem. 2007; 282: 28164–28174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Baker AB, Chatzizisis YS, Beigel R, et al. Heparanase expression in the development of thin cap fibroatheromas (TCFAs): Effects of plaque stage, endothelial shear stress, and pharmacologic interventions [abstract]. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2008;28:e48 ** This in-vivo experimental study of swine coronary arteries showed that low shear stress upregulates heparanase and modifies the economy of extracellular matrix and the natural history of individual plaques.

- 49.Geng YJ, Libby P. Progression of atheroma: a struggle between death and procreation. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2002;22;1370–1380 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Palumbo R, Gaetano C, Antonini A, et al. Different effects of high and low shear stress on platelet-derived growth factor isoform release by endothelial cells: consequences for smooth muscle cell migration. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2002;22:405–411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ziegler T, Bouzourene K, Harrison VJ, et al. Influence of oscillatory and unidirectional flow environments on the expression of endothelin and nitric oxide synthase in cultured endothelial cells. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 1998;18:686–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Qi YX, Qu MJ, Long DK, et al. Rho-GDP dissociation inhibitor alpha downregulated by low shear stress promotes vascular smooth muscle cell migration and apoptosis: a proteomic analysis. Cardiovasc Resc 2008;80(1):114–122. ** This ex-vivo experimental study showed that low shear stress induces smooth muscle cell migration and apoptosis by downregulating Rho-GDIa.

- 53.Cai Q, Lanting L, Natarajan R. Interaction of monocytes with vascular smooth muscle cells regulates monocyte survival and differentiation through distinct pathways. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2004;24: 2263–2270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Feldman CL, Coskun AU, Yeghiazarians Y, et al. Remodeling characteristics of minimally diseased coronary arteries are consistent along the length of the artery. Am J Cardiol 2006;97:13–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Varnava AM, Mills PG, Davies MJ. Relationship between coronary artery remodeling and plaque vulnerability. Circulation 2002;105: 939–943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Nakamura M, Nishikawa H, Mukai S, et al. , Impact of coronary artery remodeling on clinical presentation of coronary artery disease: an intravascular ultrasound study. J Am Coll Cardiol 2001; 37:63–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Okura H, Kobayashi Y, Sumitsuji S, et al. Effect of culprit-lesion remodeling versus plaque rupture on three-year outcome in patients with acute coronary syndrome. Am J Cardiol. 2009;103(6):791–795. ** This human IVUS study in patients with acute coronary syndromes showed that culprit lesion positive remodeling was a stronger predictor of long-term clinical outcome than plaque rupture.

- 58. Koskinas K, Chatzizisis YS, Coskun AU, et al. High-risk coronary plaques develop in regions of persistently low endothelial shear stress: A long-term, serial natural history IVUS study. Atherosclerosis Suppl 2009; 10(2). ** This in-vivo, natural history IVUS study on swine coronary arteries showed that regions of persistently low shear stress develop high-risk excessive expansive remodeling.

- 59.Tedgui A, Mallat Z. Apoptosis as a determinant of atherothrombosis. Thromb Haemost 2001;86:420–426. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lin Z, Kumar A, SenBanerjee S, et al. Kruppel-like factor 2 (KLF2) regulates endothelial thrombotic function. Circ Res. 2005. Mar 18;96(5):e48–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Davies PF. Hemodynamic shear stress and the endothelium in cardiovascular pathophysiology. Nat Clin Pract Cardiovasc Med. 2009;6(1):16–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Dirksen MT, van der Wal AC, van den Berg FM, et al. Distribution of inflammatory cells in atherosclerotic plaques relates to the direction of flow. Circulation. 1998;98(19):2000–2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Segers D, Helderman F, Cheng C, et al. Gelatinolytic activity in atherosclerotic plaques is highly localized and is associated with both macrophages and smooth muscle cells in vivo.Circulation. 2007;115(5):609–616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Muller JE, Tofler GH, Stone PH. Circadian variation and triggers of onset of acute cardiovascular disease. Circulation. 1989;79(4):733–43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Fukumoto Y, Hiro T, Fujii T, et al. Localized elevation of shear stress is related to coronary plaque rupture: a 3-dimensional intravascular ultrasound study with in-vivo color mapping of shear stress distribution. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;51(6):645–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Gijsen FJ, Wentzel JJ, Thury A, et al. Strain distribution over plaques in human coronary arteries relates to shear stress. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2008;295(4):H1608–H1614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Groen HC, Gijsen FJ, van der Lugt A, et al. Plaque rupture in the carotid artery is localized at the high shear stress region: a case report. Stroke. 2007;38(8):2379–2381 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Slager CJ, Wentzel JJ, Gijsen FJ, et al. The role of shear stress in the generation of rupture-prone vulnerable plaques. Nat Clin Pract Cardiovasc Med. 2005;2(8):401–407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Schaar JA, Regar E, Mastik F, et al. Incidence of high-strain patterns in human coronary arteries: assessment with three-dimensional intravascular palpography and correlation with clinical presentation. Circulation. 2004;109(22):2716–2719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Chatzizisis YS, Jonas M, Beigel R, et al. Attenuation of inflammation and expansive remodeling by valsartan alone or in combination with simvastatin in high-risk coronary atherosclerotic plaques. Atherosclerosis. 2009;203(2):387–394. ** In this in-vivo experimental study valsartan, alone or combined with simvastatin, attenuated the proinflammatory effect of low shear stress and reduced high-risk plaque characteristics.

- 71.Parmar KM, Nambudiri V, Dai G, et al. Statins exert endothelial atheroprotective effects via the KLF2 transcription factor. J Biol Chem. 2005. Jul 22;280(29):26714–26719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Ohayon J, Finet G, Gharib AM, et al. Necrotic core thickness and positive arterial remodeling index: emergent biomechanical factors for evaluating the risk of plaque rupture. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2008; 295(2):H717–727. ** This computational study showed that the risk of acute plaque disruption is determined by the combination of fibrous cap thickness, necrotic core thickness, and arterial remodeling.

- 73.Cannon CP, Braunwald E, McCabe CH, et al. Intensive versus moderate lipid lowering with statins after acute coronary syndromes. N Engl J Med 2004;350:1495–1504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Boden WE, O’Rourke RA, Teo KK, et al. Optimal medical therapy with or without PCI for stable coronary disease. N Engl J Med 2007;356:1503–1516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Cutlip DE, Chhabra AG, Baim DS, et al. Beyond restenosis: five-year clinical outcomes from second-generation coronary stent trials. Circulation 2004; 110:1226–1230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Rybicki FJ, Melchionna S, Mitsouras D, et al. Prediction of coronary artery plaque progression and potential rupture from 320-detector row prospectively ECG-gated single heart beat CT angiography: Lattice Boltzmann evaluation of endothelial shear stress. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2009. Jan 15. [Epub ahead of print] ** This human study employed computed tomography angiography for the non-invasive measurement of coronary endothelial shear stress.

- 77. Koskinas K, Coskun AU, Chatzizisis YS, et al. Identification of extremely high-risk plaques on the basis of low endothelial shear stress: implications for risk stratification [Abstract]. Atherosclerosis Suppl 2009; 10(2). **This natural history IVUS study proposed the in-vivo assessment of low ESS and arterial remodeling for the risk stratification of coronary atherosclerotic plaques.

- 78. Stone GW, Lansky AJ, Pocock SJ, et al. Paclitaxel-eluting stents versus bare-metal stents in acute myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med 2009;360:1946–59. ** This human study showed that implantation of paclitaxel-eluted stents was associated with reduced in-stent restenosis compared to bare-metal stents in patients with acute myocardial infarction.

- 79. Malenka DJ, Kaplan AV, Lucas FL, et al. Outcomes following coronary stenting in the era of bare-metal vs the era of drug-eluting stents. JAMA 2008;299(24):2868–2876 ** This observational study showed that the use of drug-eluting stents was associated with a decline in the need for repeat revascularization, compared to bare-metal stents.

- 80. Unverdorben M, Vallbracht C, Cremers B, et al. Paclitaxel-coated balloon catheter versus paclitaxel-coated stent for the treatment of coronary in-stent restenosis. Circulation 2009;119;2986–2994. ** This clinical study demonstrated a comparable efficacy and tolerabilityof paclitaxel-coated balloon catheter and paclitaxel-eluting stent for the inhibition of coronary in-stent restenosis.

- 81.Serruys PW, Ormiston JA, Onuma Y, et al. A bioabsorbable everolimus-eluting coronary stent system (ABSORB): 2-year outcomes and results from multiple imaging methods. Lancet. 2009;373(9667):897–910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]