Highlights

-

•

Classification and structural characterization challenges of RS are discussed.

-

•

Theory and variants of flow field-flow fractionation (FlFFF) are introduced.

-

•

The controllable factors affecting FlFFF analysis of RS are discussed.

-

•

Applications of FlFFF in the structural characterization of RS are reviewed.

Keywords: Resistant starch, Flow field-flow fractionation, Characterization

Abstract

The unique properties of resistant starch (RS) have made it applicable in the formulation of a broad range of functional foods. The physicochemical properties of RS play a crucial role in its applications. Recently, flow field-flow fractionation (FlFFF) has attracted increasing interest in the separation and characterization of different categories of RS. In this review, an overview of the theory behind FlFFF is introduced, and the controllable factors, including FlFFF channel design, sample separation conditions, and the choice of detector, are discussed in detail. Furthermore, the applications of FlFFF for the separation and characterization of RS at both the granule and molecule levels are critically reviewed. The aim of this review is to equip readers with a fundamental understanding of the theoretical principle of FlFFF and to highlight the potential for expanding the application of RS through the valuable insights gained from FlFFF coupled with multidetector analysis.

1. Introduction

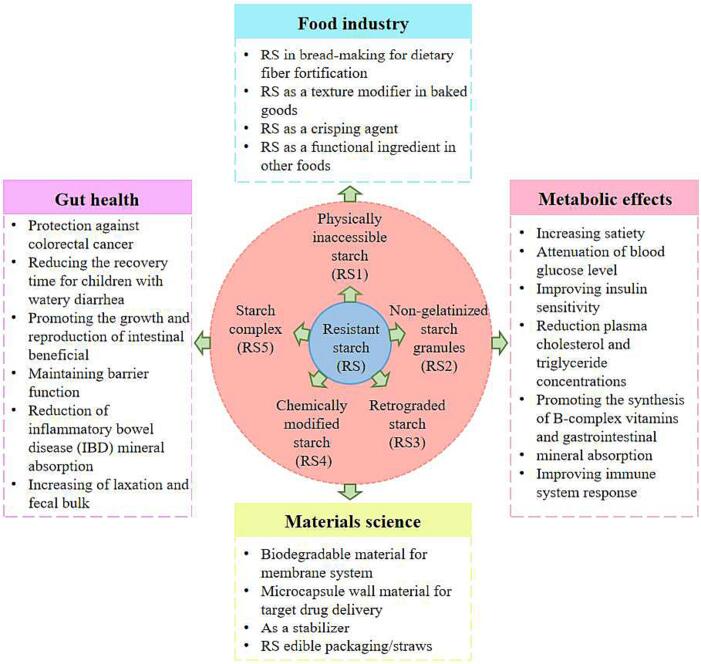

Resistant starch (RS) is defined by the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) in accordance with the recommendations of Englyst and EURESTA (European Food-Linked Agro-Industrial Research-Concerted Action on Resistant Starch) as the starches and their degradation products that remain unabsorbed in the small intestine of healthy individuals (Asp, 1992). RS is categorized into five distinct groups (RS1-RS5) based on its morphology and physicochemical properties (Table 1) (Brown, 1996, Englyst et al., 1992, Evans, 2016). RS exhibits dietary fiber functional properties, including prevention of gastrointestinal and cardiovascular diseases, improvement of immunity, and enhancement of mineral absorption. RS has been applied in the food industry, medical care, material science, and other fields (Fig. 1) (Hernandez-Hernandez et al., 2023, Liang et al., 2023, Tekin and Dincer, 2023, Thongsomboon et al., 2023, Wang et al., 2023, Wen et al., 2023).

Table 1.

Classification of resistant starch and structural characteristics of resistance to enzymatic digestion.

| Classification of RS | Structure affecting digestion | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Physically inaccessible starch (RS1) | Starch granules encased by a thick cell wall and matrix | (Brown, 1996) |

| Non-gelatinized starch granules (RS2) | Semicrystalline properties of starch granules, susceptibility of the granules to gelatinization | (Gallant, Bouchet, Buléon, & Pérez, 1992) |

| Retrograded starch (RS3) | The more orderly internal structure of the rearranged starch with stable hydrogen bonds | (Englyst, Kingman, & Cummings, 1992) |

| Chemically modified starch (RS4) | High hydrophobicity, increased intergranular connections density, crosslinks, and steric hindrance | (Dong & Vasanthan, 2020) |

| Starch complex (RS5) | Helical molecular structure formed by amylose and long branched chains of amylopectin bound with different substances | (Panyoo & Emmambux, 2017) |

Fig. 1.

Classification and application of RS.

Starch consists of homogeneous glucan components: amylose (AM), mainly linear chains with a molecular weight (Mw) of approximately 105–106, and amylopectin (AP), branched chains with Mw of approximately 107–109 (Lu et al., 2020, Tester et al., 2004). Several factors affect RS content in starch, including AM content, plant genotypes and mutations, the physical form of grains and seeds, the size of starch granules and molecules, and food processing techniques (Lopez-Silva et al., 2020, Ma et al., 2018, Yee et al., 2021). Among these factors, the characteristics of starch granules (such as AM/AP ratio, crystal structure, and gelatinization) play a vital role in evaluating the digestive properties and functional mechanisms of RS (Ding et al., 2019, Gong et al., 2019). French (1984) investigated the crystal structure of starch granules by the X-ray diffraction (XRD) technique. Three possible crystalline structures of starch granules were identified by XRD: type A, type B, and type C. Type A starch contains a digestible additional spiral in the center of its hexagonal array (Imberty, Chanzy, Pérez, Buléon, & Tran, 1987), while type B starch has water occupying the central hexagonal array, making it difficult to digest (Brown, 1996). Type C starch is considered the combination of type A and type B crystallization and has resistance to enzymatic hydrolysis. Another significant factor affecting the resistance of natural starch granules to enzymatic hydrolysis is the sensitivity to gelatinization. Gelatinization can lead to the breakdown and dissolution of the compact crystal structure of starch granules, making them more susceptible to digestion by enzymes. Although the AOAC (Association of Official Analytical Communities) method is commonly used for determining RS content, it cannot provide structural insights into RS. Recently, Guo et al. (2022) developed a novel approach for the structural characterization and quantitative analysis of RS by offline coupling of asymmetrical flow field-flow fractionation (AF4) and liquid chromatography (LC). The results showed that the digestibility of starch is closely related to its crystal structure. The AM molecules in type C starch play a crucial role in the anti-digestion process. The results demonstrated that AF4 × LC is a powerful method for informative structural detection and quantitative analysis of RS over its entire Mw distribution.

Size exclusion chromatography (SEC), fluorophore-assisted carbohydrate electrophoresis (FACE), and high performance anion exchange chromatography (HPAEC) are commonly used to characterize starch (Gilbert, Witt, & Hasjim, 2013). HPAEC coupled with a pulsed amperometric detector (PAD) can provide information on the chain length distribution (CLD) of starch (Li, Li, & Gilbert, 2019). Longer CLDs are associated with a more ordered physical structure, especially in retrograded starches (RS3), which contributes to higher resistance to enzymatic digestion (Zhu & Liu, 2020). SEC, a size-based separation method, can be used to separate AM and AP molecules. Furthermore, SEC coupled with multiangle light scattering (MALS) is commonly used to determine the Mw and radius of gyration (Rg) distributions of the starch components (Bello-Perez, Agama-Acevedo, Lopez-Silva, & Alvarez-Ramirez, 2019). However, obtaining an accurate detection of AP molecules can be challenging due to column adsorption and shear degradation of AP molecules (Cave, Seabrook, Gidley, & Gilbert, 2009). Flow field-flow fractionation (FlFFF) is a valuable technique for separating starch with ultrahigh Mw due to its rapid and gentle separation mechanism (Giddings, 1966). Notably, FlFFF lacks a stationary phase and packing material in the channel, which minimizes shear degradation risks, especially for AP molecules (González-Espinosa, Sabagh, Moldenhauer, Clarke, & Goycoolea, 2019). FlFFF coupled with online MALS and differential refractive index (dRI) detectors can provide the entire size distribution and molecular conformation information about RS (Zhang, Shen, Song, Chen, Zhang, & Dou, 2021). Wahlund et al. (2011) studied a wide range of starches from different plant sources by AF4-MALS-dRI. The results showed that the relative quantity, Mw, Rg, and hydrodynamic diameter (dh) of starch molecules from different plant sources and varieties varied greatly. AF4-MALS-dRI has been proven to be a valuable tool for characterizing RS.

In a previous review, the dissolution, structure, and functions of starch characterized by AF4-MALS-dRI were summarized (Guo, Li, An, Shen, & Dou, 2019). Compared to SEC, FlFFF analysis of starches involves a greater number of controllable factors. To our knowledge, there is a notable absence of comprehensive reviews on the separation and characterization of RS by using FlFFF. In this review, the theory of FlFFF and the controllable factors affecting the sample separation of FlFFF are introduced in detail. The applications of FlFFF in the separation and characterization of RS are critically reviewed.

2. Flow field-flow fractionation (FlFFF)

FlFFF, an important sub-technique of field-flow fractionation, was proposed by Giddings in 1976. FlFFF has the widest separation range and the best compatibility with various carrier liquids, supporting extensive applications to multi-sized analytes from diverse sources (Wu et al., 2023). In this review, the theory and operation modes and the variant of FlFFF are reviewed.

2.1. Principle of flow field-flow fractionation (FlFFF)

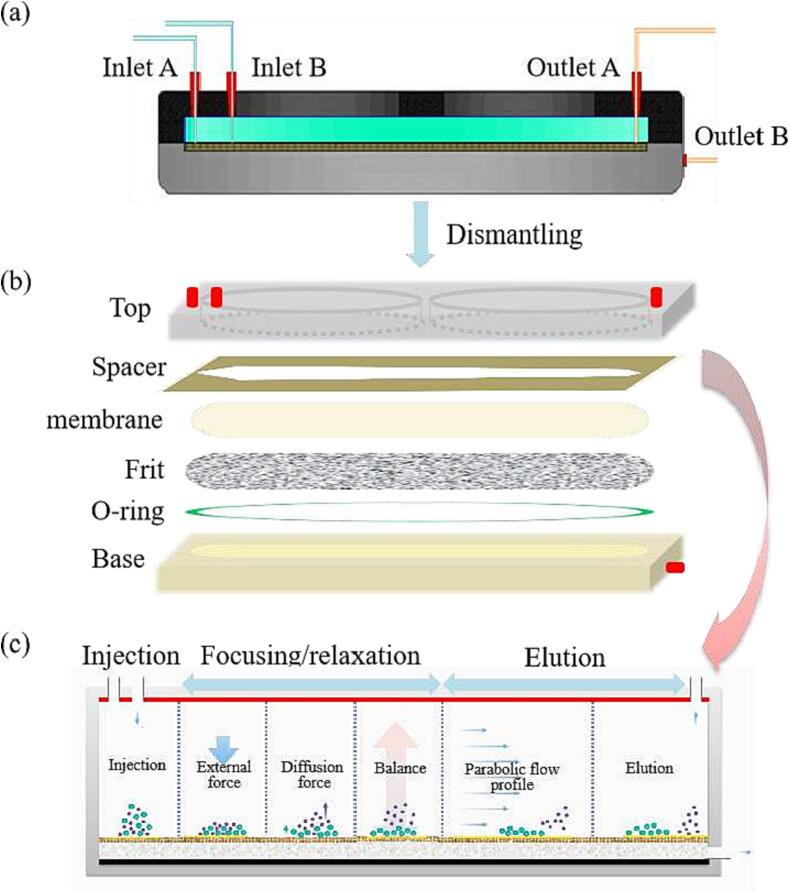

In FlFFF, a ribbon-like separation channel (as shown in Fig. 2(a)) is usually assembled by sandwiching a thin spacer between two blocks (top and base in Fig. 2(b)). The shape of the spacer determines the shape of the FlFFF separation channel. In the FlFFF channel, the fluid can be approximated as a Poiseuille flow between two infinite planes, and the flow phase velocity distribution within the separation channel can be approximated as a parabolic flow profile (Fig. 2(c)). From the edge of the channel to its center, the flow velocity of the fluid gradually increases and reaches a maximum at the centerline. An applied external force, called cross-flow, is introduced in the direction perpendicular to the separation channel, which persists throughout the separation process. When the sample is injected into the separation channel, the sample particles accumulate on its bottom wall (acting as an accumulation wall) under the combined action of the applied external force and its own diffusion force. When the applied external force is balanced with the diffusion force of the particles, the samples can be separated in the channel. FlFFF maintains the integrity of the structure and properties of the sample, and the collected fractions can be further analyzed online or offline using other characterization methods (e.g., ultraviolet (UV), fluorescence, dRI, MALS, etc.).

Fig. 2.

Schematic diagram of the channel (a and b) and separation process (c) of FlFFF.

2.2. Variants of flow field-flow fractionation (FlFFF)

Several variants of FlFFF have been developed, each with different characteristics as summarized in Table 2. Symmetrical FlFFF (SF4) channel has a permeable top wall, and the flow conditions are set at low flow rates with identical inlet and outlet flow velocities. However, SF4 presented certain challenges, including prolonged injection time, peak broadening, and low resolution (Giddings, Yang, & Myers, 1977). It was improved by AF4 (Wahlund & Giddings, 1987, Wahlund et al., 1986). In AF4, the top wall of the channel is impermeable, and the bottom wall is permeable, allowing the cross-flow to pass through the channel. Subsequently, the trapezoidal asymmetrical parallel plate channel (TrAF4) was developed (Litzen, 1993, Litzen and Wahlund, 1991). AF4 is suitable for the characterization of synthetic and natural polymers, including proteins and polysaccharides. In addition to soluble polymers, AF4 can separate colloidal particles in the range of approximately 1 nm to 1 µm in diameter (in the normal mode) (Podzimek, 2012).

Table 2.

Characteristics of FlFFF variants.

| FlFFF variant | Characteristic | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Symmetrical FlFFF (SF4) | Low flow conditions, stop-flow relaxation period | (Giddings, Yang, & Myers, 1977) |

| Asymmetrical FlFFF (AF4) | Most used, high resolution | (Wahlund & Giddings, 1987) |

| Hollow fiber FlFFF (HF5) | Low sample loading, high sensitivity due to lower dilution, short analysis time, potentially disposable | (Joensson & Carlshaf, 1989) |

| Frit inlet FlFFF | On-the-fly sample relaxation so no stop-flow or focusing flow step, generally lower separation resolution than AF4, good for samples prone to undesirable interactions with the membrane accumulation wall | (Fuentes et al., 2019, Fuentes et al., 2019a, Fuentes et al., 2019b) |

| Frit outlet FlFFF | Enhancement in detector signal intensity due to lower dilution | (Clark, & Zika, 2001) |

Hollow fiber FlFFF (HF5) was developed with some advantages such as low sample loading, high sensitivity, short analysis time, and potential disposability (Joensson & Carlshaf, 1989). However, it is worth noting that low sample loading and disposability also represent disadvantages for this method. To solve the overloading effect observed with HF5, the tandem HF5 approach was developed to enhance the detection of low abundance components (Zattoni, Rambaldi, Casolari, Roda, & Reschiglian, 2011). Commercially manufactured AF4 instruments equipped with frit inlet and frit outlet channel came into existence in the 1990s. The key advantage of the frit inlet FlFFF channel is the elimination of the focusing step, enabling a higher injection mass compared to a conventional channel, thereby mitigating the risk of sample overloading (Fuentes et al., 2019, Fuentes et al., 2019a, Fuentes et al., 2019b). The frit outlet FlFFF channel enhances mass detection sensitivity (Clark & Zika, 2001).

2.3. Elution modes of flow field-flow fractionation (FlFFF)

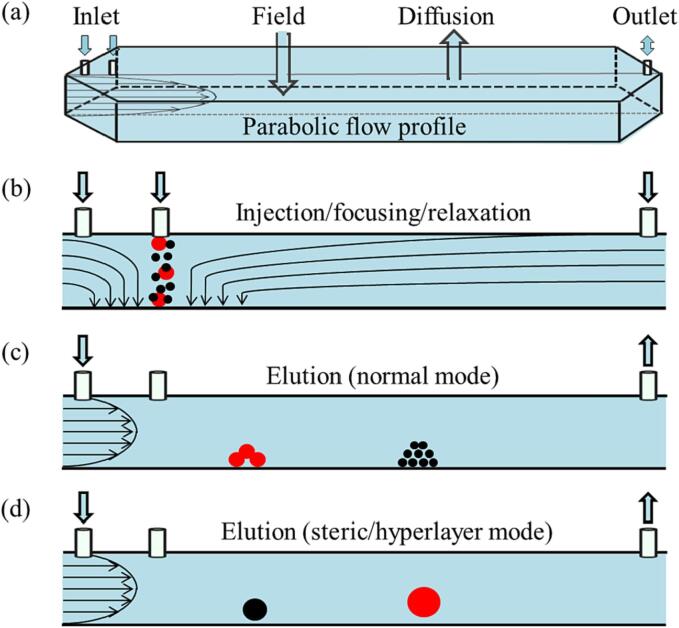

The sample separation in FlFFF occurs within a ribbon-like channel. According to the elution order of the samples, elution modes of FlFFF are categorized into normal mode and steric/hyperlayer mode (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Main separation modes of FlFFF.

2.3.1. Normal mode

The field force (FF) employed in FlFFF makes the sample components spread uniformly to the accumulation wall, which is expressed as Eq. (1) (Giddings, Ratanathanawongs, & Moon, 1991):

| (1) |

where η is the viscosity of the carrier liquid, dh is the hydrodynamic diameter of the particle, Vc is the cross-flow rate, w is the channel thickness, and V0 is the void volume. Eq. (1) shows that FF is proportional to Vc. At the same time, the sample components diffuse away from the accumulation wall under the action of Brownian motion and finally form an equilibrium layer between the two opposing transport processes. For the sample with dh smaller than 1 μm, separation occurs in the normal mode, and retention time (tr) is inversely proportional to the diffusion coefficient D and proportional to dh (Ratanathanawongs Williams & Lee, 2006). The carrier liquid enters the channel from the inlet and forms a parabolic profile inside the channel, with the highest velocity at the center of the channel (Fig. 3). As a result, the smaller particles are eluted earlier than larger ones, which is the so-called normal mode, as shown in Fig. 3(c).

2.3.2. Steric/hyperlayer mode

As the sample diameter increases, the elution mode shifts from the normal mode to the steric/hyperlayer mode with an opposite elution order (Kim, Yang, & Moon, 2018). When the particle size is larger than 1 μm, the diffusion force of the particle can be ignored. In this case, the particles are driven downward by the FF to (or close to) the accumulation wall, where the centers of the large particles are in a faster stratosphere and then are eluted first (Fig. 3(d)) (Giddings, 1993, Myers and Giddings, 1982). When the force of hydrodynamic lift (FHL) is sufficient to counteract the FF, a particle-focusing layer is formed at a distance from the accumulation wall (Mélin et al., 2012). FHL is caused by inertia and other factors of liquid carriers (Reschiglian et al., 2000). There is the “steric transition” phenomenon when the sample elution mode changes from the normal mode to the steric/hyperlayer mode (Dou et al., 2013, Kim et al., 2018). When the sample’s size range spans the steric transition region (i.e., the particle size range overlaps between the normal mode and steric/hyperlayer mode), it can lead to simultaneous elution of particles with different sizes. This makes it challenging to determine the accurate size distribution of the sample components (Dou et al., 2015, Perez-Rea et al., 2017, Zielke et al., 2018). The particles with large size are generally formed during starch retrogradation process. Therefore, when FlFFF is employed for the separation of RS3, great care is needed, as steric phenomenon may occur (Zhang et al., 2019).

2.4. Resolution and retention ratio in flow field-flow fractionation (FlFFF)

Resolution (Rs) is one term for evaluating the separation efficiency between two analyte components. During the separation process of two components, two distinct types of dispersion need to be considered: selective dispersion (Δtr) and random dispersion (Schimpf, Myers, & Giddings, 1987). Δtr is beneficial to the separation of two components, whereas random dispersion is not. Δtr is quantified by the selectivity (S), which reflects the difference in retention volume (or tr) with Mw or particle diameter. Random dispersion is quantified by plate height (H). Therefore, the resolution depends on both H and S, and can be expressed as Eq. (2):

| (2) |

where Δz is the gap between the centers of gravity of neighboring zones and σ is the standard deviation of the zones. The subscripts on σ refer to components 1 and 2, and refers to an average value for two zones. Consequently, Δz reflects selective dispersion, while σ indicates the extent to which the gap is filled by cross-contamination due to random dispersion. It is well known that the Mw of AM and AP molecules has an overlap (Dou et al., 2014, Zhang et al., 2019). Thus, a baseline separation for starch samples by FlFFF is still a challenge.

The retention ratio (R) is defined as the ratio of the times associated with the void time and retention time, and it is expressed as Eq. (3):

| (3) |

where γ is a dimensionless parameter that depends on the field strength, migration velocity, and particle size (Kim, Yang, & Moon, 2018). α is the ratio of particle radius (a) to w, λ is the ratio of the mean layer thickness (l) to w, which can be expressed as (Wahlund & Giddings, 1987):

| (4) |

where k is the Boltzmann constant and T is the absolute temperature. When λ is very small, Eq. (3) can be reduced to Eq. (5):

| (5) |

In the Eq. (5), the first term of the equation is proportional to the particle size, while the second term is inversely proportional to the particle size. As a result, R decreases with increasing dh and reaches the minimum value (Ri). The diameter corresponding to Ri is called the “steric transition point” (di). di and Ri are expressed as Eqs. (6), (7), respectively:

| (6) |

and

| (7) |

For highly retained components in FlFFF (l≪w or λ → 0), Eq. (5) can be approximated to yield a so-called “simplified” retention equation (Eq. (8) for the normal mode and Eq. (9) for the steric/hyperlayer mode):

| (8) |

| (9) |

In the normal mode, R is inversely proportional to the particle size, while in the steric/hyperlayer mode, R is proportional to the particle size. The value of γ is related to the information of the elution mode (steric or hyperlayer mode) (Moon & Giddings, 1992). When the sample size ranges in the steric transition region, the elution mode can be adjusted by changing the elution parameters. For FlFFF analysis of polydisperse samples (such as RS), it is crucial to optimize the elution conditions to avoid steric transition.

3. Factors affecting sample separation of flow field-flow fractionation

Despite the excellent separation performance of FlFFF, the retention and accumulation of samples on the surface of the accumulation wall can result in low sample recovery, which may limit the potential applications of this technology. Additionally, the retention capacity of ultrafiltration membranes imposes constraints on the minimum sample size in FlFFF. Therefore, prior to conducting sample separation using FlFFF, a series of parameters need to be optimized to attain ideal separation conditions for the given sample. The primary factors that influence sample separation and characterization in FlFFF include the composition of the separation channel, the conditions used for sample separation, and the sensitivity of the detectors.

3.1. Performance of the FlFFF channel

The channel profile in FlFFF is usually designed with diverse dimensions and shapes (Kang & Moon, 2004). The channel dimensions are described by w, the breadth (b), and the length (L). The w is controlled by the thickness of the spacer. The actual thickness of the FlFFF channel is typically 50 µm smaller than the spacer thickness due to the compression of the semipermeable membrane. In comparison to a rectangular channel, the trapezoidal channel design serves to partially compensate for the reduction in axial flow velocity, resulting from the loss of cross-flow through the membrane. This, in turn, mitigates peak dilution and enhances detector responsiveness. At a consistent cross-flow rate, the actual field force is contingent on the area of the semipermeable wall, comprising the channel length L, the channel breadths b0 (inlet breadth of trapezoidal FlFFF channel), and bL (outlet breadth of the trapezoidal FlFFF channel), and the areas of tapered ends. Shorter and/or narrower channels are employed to achieve higher field force, which reduces solvent consumption and enhances sample separation efficiency. The lower size limit is determined by the molecular weight cut off (MWCO) of the membrane, while the upper size limit is assessed by a threshold of 20 % of the FlFFF channel thickness.

Ultrafiltration membranes made of regenerated cellulose (RC), polyether sulfone (PES), and cellulose triacetate (CT) with MWCO of 0.3–100 kDa are commonly employed as accumulation walls in FlFFF. Since smaller monosaccharides and oligosaccharides can pass through the ultrafiltration membrane, oligosaccharides with sizes comparable to the MWCO may be blocked in the pores of the ultrafiltration membrane, and large starch molecules can interact with the membrane through chemical (adsorption) or physical (rough surface) interactions, which may result in lower sample recovery and potential membrane contamination. To mitigate these issues, the selection of an appropriate ultrafiltration membrane type and MWCO is crucial to minimize the interactions between the sample and the surface of the membrane, which can ensure a higher sample recovery. In practical applications, when dealing with charged samples, it is essential to choose a suitable carrier liquid to eliminate the interaction between the samples and the ultrafiltration membrane (González-Espinosa, Sabagh, Moldenhauer, Clarke, & Goycoolea, 2019).

3.2. Sample separation conditions

Mudalige et al. (2015) reported that sample modification can alter sample retention within FlFFF. In addition to altering the nature of the sample, optimizing the separation conditions of FlFFF (e.g., external forces, the nature of the carrier liquid, injection mass, and focusing time) can enhance sample recovery.

3.2.1. External force

During the FlFFF separation process, the choice of external force is critical, as a lower external force can lead to decreased Rs, while a higher external force may increase the risk of sample aggregation and interaction with the surface of the membrane. Optimizing the external force is essential to achieve good sample resolution. For heterogeneous samples with a wide size distribution, it is recommended to employ gradient external force to shorten the analysis time. In the FlFFF elution process, the external force action can be categorized into three main modes: constant mode, linear attenuation mode, and exponential attenuation mode. Among them, the combination of exponentially attenuated external force with other external force modes is frequently employed for the separation of starch samples (Ma, Buschmann, & Winnik, 2010).

3.2.2. Selection of carrier liquid

Ideally, the carrier liquid should be compatible with properties of the sample (such as pH and ionic strength) to inhibit the instability of the sample molecules (such as degradation, aggregation, and adsorption) during FlFFF separation (Kammer, Legros, Hofmann, Larsen, & Loeschner, 2011). Generally, it is recommended to use electrolyte solutions with ionic strength and pH conditions similar to those of the sample. Additionally, in some cases, surfactants are needed to maximize sample recovery, and a bactericide (e.g., sodium azide) can be added to prevent bacterial growth. For starch samples from different plant sources, a carrier liquid composed of diluted electrolytes (such as 1–50 mM NaNO3) is recommended (Nilsson, 2013).When separating polysaccharides (such as chitosan complex and dextran), deionized water is sometimes chosen as the carrier liquid (Faucard et al., 2018, Fraunhofer et al., 2018). To separate the mixture of starches and other biomacromolecules, buffer solutions such as acetate buffer, phosphate buffer, and sodium citrate buffer are commonly used as carrier liquids. Ideally, on the premise of ensuring the stability of the sample, a carrier liquid with a pH value that maximizes repulsion between the sample and the surface of the accumulation wall and an appropriate ionic strength to prevent starch aggregation and/or adsorption should be selected.

3.2.3. Injection mass

FlFFF can provide precise sample characterization with relatively small sample amounts, typically approximately 10 μg or less, depending on the sensitivity of the detection method (Caldwell, Brimhall, Gao, & Giddings, 1988). It is important to be aware of the phenomenon of “sample overloading.” Sample overloading results in an excessively high concentration of sample components in the concentration region of the accumulation wall. Sample overloading involves multiple concentration-dependent phenomena, which can lead to an unstable retention ratio (increase or decrease) and asymmetrical peak (tail or front). During the elution process, the interaction between samples or between the sample and the surface of the accumulation wall increases, which results in sample aggregation and/or adsorption (Benincasa and Giddings, 1992, Schimpf et al., 2000). AP with an ultrahigh Mw is particularly susceptible to sample overloading due to chain entanglement and viscosity effects. Arfvidsson and Wahlund (2003) found that a large injection volume with a low sample concentration is superior to using a small injection volume with a high sample concentration. Therefore, the key to avoid sample overloading is to reduce the maximum sample concentration, which can be achieved by decreasing the injected sample mass.

3.2.4. Focusing time

Regarding the focusing time, during the FlFFF injection and focusing process, it is essential to extend the focusing time to enrich the sample. This ensures that the sample concentration surpasses the detection limit of the detector and minimizes peak broadening. If the focusing time is too short, the sample equilibrium layer distribution is wide, and some sample components may elute within the void peak. On the other hand, an excessively long focusing time can increase the interaction between samples and between samples and the surface of the membrane, potentially leading to sample aggregation and excessive retention (Wahlund, 2013). Therefore, selecting an appropriate focusing time is also a crucial factor in the separation and characterization of RS using FlFFF.

3.3. Sensitivity of the detectors

The sensitivity and detection limit of the detector play a crucial role in the accuracy of characterizing samples by FlFFF. AF4 coupled with a mass detector (typically MALS) and a concentration detector (usually dRI) is primarily used for the separation and characterization of starch molecules in the normal mode. AP molecules with higher Mw and viscosity tend to be closer to the accumulation wall during AF4 separation and are prone to absorb on the surface of the accumulation wall. To achieve optimal separation for AP molecules, it is essential to operate at a lower concentration (Chiaramonte, Rhazi, Aussenac, & White, 2012). The intensity of the MALS signal is influenced by both the concentration and the size of the sample components. According to Rayleigh's approximation, the intensity of light scattering by a particle is proportional to the sixth power of the particle’s diameter (I ∝ d6), making it more challenging to detect scattered light from smaller particles. Consequently, when a mixture of particles with different sizes is present in the suspension, the data tend to be skewed toward larger particle sizes (Doyle and Wang, 2019, Guisbiers et al., 2016). However, MALS signal detection is particularly challenging for AM molecules with a lower tr due to their smaller size (Yoo, Choi, Zielke, Nilsson, & Lee, 2017). The sample recovery is determined from the ratio of the mass eluted from the separation channel (integration of the dRI signal) to the injected mass (based on the starch content). However, at a lower injection mass, the dRI detector may exhibit a low signal-to-noise ratio, making it difficult to accurately determine sample recovery and Mw. In such cases, averaging multiple injections can be a reliable method to enhance the accuracy of starch characterization (Leeman, Islam, & Haseltine, 2007). This approach can improve the accuracy of quantitative analysis of AM but may not provide detailed Mw and conformational information about AP. Thus, the subsequent improvements of FlFFF technique (such as modified membranes, coupled with precision detection methods) are necessary to address the characterization challenges of AP molecules.

4. Application of FlFFF for the structural characterization of RS

The characterization of starch at both the granule and molecule levels by direct measurement of physicochemical parameters in association with MALS and dRI is a key feature of the FlFFF technique. The information about the RS obtained from FlFFF is outlined in Table 3.

Table 3.

The information about RS obtained from FlFFF.

| Source of RS | Type of RS | Type of FlFFF | FlFFF operation condition |

Detection | The information gained by FlFFF | Reference | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Carrier liquid | Membrane | Cross-flow rate | Injection mass | ||||||

| Rice, lotus | RS1 | AF4 | 3 mM NaN3, 0.35 mM SDS |

RC | 1.2 → 0.05 mL/min Half-time t1/2 = 3 min |

100 μg | UV, MALS, dRI | Mw, Rg | (Song et al., 2021) |

| Mung bean, yam, banana | RS2 | AF4 | 5 mM NaNO3 | RC | 1.2 → 0.05 mL/min t1/2 = 3 min |

10 μg | MALS, dRI, LC | Mw, Rg, content of RS | (Guo, Zhang, Sun, Ye, Shen, & Dou, 2022) |

| Potato | RS2 | AF4 | 3 mM NaN3, 5 mM NaNO3 | RC | 1.2 → 0.05 mL/min t1/2 = 3 min |

25 μg | MALS, dRI | Mw, Rg, ρapp, Rg/Rh | (Zhang, Shen, Song, Chen, Zhang, & Dou, 2021) |

| Maize, wheat, rice potato, tapioca, pea | RS2 | AF4 | – | RC | 1.0 → 0 mL/min t1/2 = 4 min |

40 μg | MALS, dRI | Mw, Rg, Rh | (Wahlund, Leeman, & Santacruz, 2011) |

| Potato, maize, wheat | RS2 | AF4 | 3 mM NaN3 | – | – | – | MALS, QELS, dRI | Mw, Rg, Rh | (Rolland-Sabaté, Guilois, Jaillais, & Colonna, 2011) |

| Potato, maize | RS3 | AF4 | 3 mM NaN3, 50 mM NaNO3 | RC | 1.4 → 0.05 mL/min t1/2 = 2 min |

100 μg | MALS, dRI | Mw, Rg, ρapp, Rg/Rh | (Zhang et al., 2019) |

| Wheat | RS3 | AF4 | – | RC | 2.0 → 0.12 mL/min t1/2 = 4 min |

1.25–15 μg | MALS, dRI | Mw, Rg, ρapp, Rg/Rh | (Fuentes, Castañeda, Rengel, Peñarrieta, & Nilsson, 2019) |

| Maize | RS4 | AF4 | 3 mM NaN3, 50 mM NaNO3 | RC | 0.2 mL/min | 100 μg | MALS, dRI | Mw | (Lee et al., 2010) |

| – | RS4 | AF4 | 3 mM NaN3, 1 M NaCl | RC | 1.0 or 2.0 mL/min | 40–300 μg | MALS, dRI | Mw, Rg, Rg/Rh | (Wittgren, Wahlund, Andersson, & Arfvidsson, 2002) |

| Barley | RS4 | EAF4 | 10 mM PBS | RC | 2.0 → 0.25 mL/min t1/2 = 3 min |

60 μg | MALS, dRI | Mw, Zeta potential | (Fuentes, Choi, Wahlgren, & Nilsson, 2023) |

4.1. Physically inaccessible starch (RS1)

Song et al. (2021) utilized AF4-MALS-dRI to separate and characterize starch granules and starch molecules extracted from various plant sources. The AF4 results were validated by a combination of optical microscopy (OM), scanning electron microscopy (SEM), and dynamic light scattering (DLS) techniques. The size distributions of starch granules determined by AF4 were in reasonable agreement with those obtained from OM. However, OM measurement is time-consuming. The results suggested that AF4 is an appropriate method for determining the sizes of starch granules. Meanwhile, the relationships between the size of starch at nano- to microscale and its functional properties (i.e., digestibility, retrogradation, and thermal properties) were studied by Pearson correlation analysis. The results showed that the sizes of starch granules and starch molecules from different plant sources were related to their digestibility.

4.2. Non-gelatinized starch granules (RS2)

Rolland-Sabaté et al. (2011) utilized AF4 coupled with MALS, quasi-elastic light scattering (QELS), and dRI (AF4-MALS-QELS-dRI) to analyze the structure of varying AM/AP ratios and natural starches from different plant sources. The results showed that AF4 could effectively separate AP molecules and obtain more structural information about branched macromolecules. Zhang et al. (2021) explored the capability of AF4-MALS-dRI for monitoring structural and conformational changes in potato starch during enzymatic hydrolysis. The results revealed that the gelatinization process induced a loose and random coil conformation in potato AM molecules, accelerating enzymatic hydrolysis of potato starch. Guo et al. (2022) conducted structural characterization and quantification of RS extracted from various plant sources (i.e., mung bean, yam, and banana) by offline coupling AF4-MALS-dRI with LC. The results demonstrated that the combination of AF4-MALS-dRI and LC is an effective method for rapid, quantitative, and comprehensive structural information detection of RS over the entire Mw distribution.

4.3. Retrograded starch (RS3)

Starch retrogradation is an inevitable transformation during processing and storage, and often accompanies with structural and conformational changes, especially under low-temperature or cooling conditions. Zhang et al. (2019) studied the influence of the plant source, AM/AP ratio, storage conditions (temperature and time), and salt on starch retrogradation by using AF4-MALS-dRI. The results revealed that nitrate ions retarded starch retrogradation behavior by inhibiting the formation of hydrogen bonds between AM molecules. Moreover, the results highlighted the significant role played by small AM aggregates in starch retrogradation and maize AP degradation, offering valuable insights into the mechanism of starch retrogradation. Fuentes et al. (2019a) analyzed the molecular properties (such as Mw, Rg, and apparent density (ρapp)) of wheat starch in three different types of bread by AF4-MALS-dRI. The results showed that the higher the water content of the bread was, the higher the Rg, Mw, ρapp, and content of RS. The content of AM in bread may be related to ρapp, suggesting that the content of RS might be related to the difference in structural and conformational properties of starch. Furthermore, the results also indicated that characterizing non-solvent precipitated starch led to insights into how changes in molecular properties may be associated with the presence of RS (Fuentes et al., 2019b).

4.4. Chemically modified starch (RS4)

RS4 can impact its original structure and lead to changes in Mw via chemical alterations. Several methods, including acid hydrolysis, crosslinking, acetylation/esterification, dual modification, and oxidation, have been employed for the chemical modification of starch (Haq et al., 2019). Lee et al. (2010) investigated the effect of carboxymethylation on the Mw and size distribution of corn starch using AF4-MALS-dRI. The results demonstrated that carboxymethylation of starch resulted in a reduction in Mw due to molecular degradation by the alkaline treatment. The results suggested that AF4-MALS-dRI is a useful tool for monitoring the changes in Mw and the size of starch during derivatization. Additionally, Wittgren et al. (2002) explored the Mw of four commercial hydroxypropyl and hydroxyethyl-modified starches using AF4-MALS-dRI. The results highlighted the ability of AF4-MALS-dRI to provide a rapid size characterization of modified starches. Recently, Fuentes et al. (2023) investigated the capability of electrical asymmetrical flow field-flow fractionation (EAF4) for determining the charge properties over the Mw distribution of barley starch modified with octenyl succinic anhydride (OSA). The results revealed that EAF4 facilitated the estimation of the zeta potential and net charge of OSA-starch. Furthermore, the results suggested that OSA substituents were not evenly distributed at or near the “surface” of the starch, potentially affecting the adsorption behavior and functionality of OSA-starch in emulsions.

4.5. Starch complex (RS5)

RS5 is a starch complex formed by the combination of long branched chains of AM and AP with different nutrients, which prevents digestive enzymes from binding and hydrolyzing starch by forming a helical molecular structure. Several studies have reported that RS5 is formed when AM or AP is processed with fatty acids or fatty alcohols (Panyoo & Emmambux, 2017). Magnusson and Nilsson (2011) studied the interaction between hydrophobically modified starch, with octenyl succinic anhydride (OSA), and α-β-livetin, which is the water-soluble fraction of egg yolk. Although, AF4-UV-MALS-dRI has been proven to be a useful tool for studying the complex of polysaccharides and proteins (Chen et al., 2022), few studies have reported on the application of FlFFF for RS5.

5. Summary and outlook

In summary, FlFFF is a useful tool for the separation of RS that can aid in optimizing the production process of starch and elucidating the factors that contribute to their resistance to enzymatic digestion. Coupling FlFFF with multidetector (such as MALS and dRI detectors) can serve as a powerful tool to comprehensively understand the structure and conformation of RS. The FlFFF channel with a frit outlet could enhance the signal intensity of AP molecules due to lower dilution and achieve structural characterization even at low RS concentrations. Although, AF4-UV-MALS-dRI has shown its capability for the separation and characterization of RS and would open a new avenue for studying RS5, more exploration is needed regarding the structure of RS and its resistance to enzymatic digestion.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Mu Wang: Writing – original draft, Conceptualization. Wenhui Zhang: Writing – original draft, Conceptualization. Liu Yang: Visualization. Yueqiu Li: Data curation. Hailiang Zheng: Writing – review & editing, Project administration. Haiyang Dou: Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Funding acquisition.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the support provided by the Natural Science Foundation of Hebei Province (H2020201295, 202360102030020), the Hebei Province Key Research Projects (22372505D), the Interdisciplinary Research Program of Natural Science of Hebei University (DXK202115), and the Program of Innovation Ability Enhancement of Baoding (2211N012).

Contributor Information

Hailiang Zheng, Email: adam0311@hbu.edu.cn.

Haiyang Dou, Email: douhaiyang-1984@163.com.

Data availability

Data will be made available on request.

References

- Arfvidsson C., Wahlund K.G. Mass overloading in the flow field-flow fractionation channel studied by the behaviour of the ultra-large wheat protein glutenin. Journal of Chromatography A. 2003;1011(1–2):99–109. doi: 10.1016/S0021-9673(03)01145-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asp N.G. Resistant starch. Proceedings for the 2nd plenary meeting of EURESTA: European FLAIR Concerted Action No. 11 on physiological implications of the consumption of resistant starch in man. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 1992;38:S1–S148. doi: 10.1021/ac00176a004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bello-Perez L.A., Agama-Acevedo E., Lopez-Silva M., Alvarez-Ramirez J. Molecular characterization of corn starches by HPSEC-MALS-RI: A comparison with AF4-MALS-RI system. Food Hydrocolloids. 2019;96:373–376. doi: 10.1016/j.foodhyd.2019.04.067. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Benincasa M.A., Giddings J.C. Separation and molecular weight distribution of anionic and cationic water-soluble polymers by flow field-flow fractionation. Analytical Chemistry. 1992;64(7):790–798. doi: 10.1021/ac00031a016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brown I. Complex carbohydrates and resistant starch. Nutrition Reviews. 1996;54(11):S115–S119. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.1996.tb03830.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caldwell K.D., Brimhall S.L., Gao Y., Giddings J.C. Sample overloading effects in polymer characterization by field-flow fractionation. Journal of Applied Polymer Science. 1988;36(3):703–719. doi: 10.1002/app.1988.070360319. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cave R.A., Seabrook S.A., Gidley M.J., Gilbert R.G. Characterization of starch by size-exclusion chromatography: The limitations imposed by shear scission. Biomacromolecules. 2009;10(8):2245–2253. doi: 10.1021/bm900426n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X., Tian Y., Zhang J., Li Y., Zhang W., Zhang J., Dou H. Study on effects of preparation method on the structure and antioxidant activity of protein-Tremella fuciformis polysaccharide complexes by asymmetrical flow field-flow fractionation. Food Chemistry. 2022;384 doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2022.132619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiaramonte E., Rhazi L., Aussenac T., White D.R. Amylose and amylopectin in starch by asymmetric flow field-flow fractionation with multi-angle light scattering and refractive index detection (AF4–MALS–RI) Journal of Cereal Science. 2012;56(2):457–463. doi: 10.1016/j.jcs.2012.04.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Clark C.D., Zika R.G. Frit inlet/frit outlet flow field-flow fractionation: Methodology for colored dissolved organic material in natural waters. Analytica Chimica Acta. 2001;443:171–181. doi: 10.1016/S0003-2670(01)01202-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ding Y., Luo F., Lin Q. Insights into the relations between the molecular structures and digestion properties of retrograded starch after ultrasonic treatment. Food Chemistry. 2019;294:248–259. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2019.05.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong H., Vasanthan T. Amylase resistance of corn, faba bean, and field pea starches as influenced by three different phosphorylation (cross-linking) techniques. Food Hydrocolloids. 2020;101:105506. doi: 10.1016/j.foodhyd.2019.105506. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dou H., Jung E.C., Lee S. Factors affecting measurement of channel thickness in asymmetrical flow field-flow fractionation. Journal of Chromatography A. 2015;1393:115–121. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2015.03.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dou H., Lee Y.J., Jung E.C., Lee B.C., Lee S. Study on steric transition in asymmetrical flow field-flow fractionation and application to characterization of high-energy material. Journal of Chromatography A. 2013;1304:211–219. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2013.06.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dou H., Zhou B., Jang H.D., Lee S. Study on antidiabetic activity of wheat and barley starch using asymmetrical flow field-flow fractionation coupled with multiangle light scattering. Journal of Chromatography A. 2014;1340:115–120. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2014.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doyle L., Wang M. Overview of extracellular vesicles, their origin, composition, purpose, and methods for exosome isolation and analysis. Cells. 2019;8(7) doi: 10.3390/cells8070727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Englyst H.N., Kingman S.M., Cummings J.H. Classification and measurement of nutritionally important starch fractions. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 1992;46(Suppl. 2):S33–S50. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01649-06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans A. Resistant starch and health. Encyclopedia of Food Grains (Second Edition) 2016:230–235. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-394437-5.00097-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Faucard P., Grimaud F., Lourdin D., Maigret J.E., Moulis C., Remaud-Siméon M., Rolland-Sabaté A. Macromolecular structure and film properties of enzymatically-engineered high molar mass dextrans. Carbohydrate Polymers. 2018;181:337–344. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2017.10.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraunhofer M.E., Jakob F., Vogel R.F. Influence of different sugars and initial pH on β-glucan formation by lactobacillus brevis TMW 1.2112. Current Microbiology. 2018;75(7):794–802. doi: 10.1007/s00284-018-1450-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- French D. Second Edition. Chemistry and Technology; Starch: 1984. Organization of starch granules; pp. 183–247. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-746270-7.50013-6. [Google Scholar]

- Fuentes C., Castañeda R., Rengel F., Peñarrieta J.M., Nilsson L. Characterization of molecular properties of wheat starch from three different types of breads using asymmetric flow field-flow fractionation (AF4) Food Chemistry. 2019;298 doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2019.125090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuentes C., Choi J., Wahlgren M., Nilsson L. Charge and zeta-potential distribution in starch modified with octenyl succinic anhydride (OSA) determined using electrical asymmetrical flow field-flow fractionation (EAF4) Colloids and Surfaces A: Physicochemical and Engineering Aspects. 2023;657 doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfa.2022.130570. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fuentes C., Choi J., Zielke C., Peñarrieta J.M., Lee S., Nilsson L. Comparison between conventional and frit-inlet channels in separation of biopolymers by asymmetric flow field-flow fractionation. Analyst. 2019;144(15):4559–4568. doi: 10.1039/c9an00466a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuentes C., Saari H., Choi J., Lee S., Sjoo M., Wahlgren M., Nilsson L. Characterization of non-solvent precipitated starch using asymmetrical flow field-flow fractionation coupled with multiple detectors. Carbohydrate Polymers. 2019;206:21–28. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2018.10.100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallant D.J., Bouchet B., Buléon A., Pérez S. Physical characteristics of starch granules and susceptibility to enzymatic degradation. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 1992;46(Suppl 2):S3–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giddings J.C. Retention (steric) inversion in field-flow fractionation: Practical implications in particle size, density and shape analysis. Analyst. 1993;118(12):1487–1494. doi: 10.1039/an9931801487. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Giddings J.C. A new separation concept based on a coupling of concentration and flow nonuniformities. Separation science. 1966;1(1):123–125. doi: 10.1080/01496396608049439. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Giddings J.C., Ratanathanawongs S.K., Moon M.H. Field-flow fractionation: A versatile technology for particle characterization in the size range 10–3 to 102 micrometers. KONA Powder and Particle Journal. 1991;9:200–217. doi: 10.14356/kona.1991025. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Giddings J.C., Yang F.J., Myers M.N. Flow field flow fractionation as a methodology for protein separation and characterization. Analytical Biochemistry. 1977;81(2):395–407. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(77)90710-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert R.G., Witt T., Hasjim J. What is being learned about starch properties from multiple-level characterization. Cereal Chemistry. 2013;90(4):312–325. doi: 10.1094/CCHEM-11-12-0141-FI. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gong B., Cheng L.L., Gilbert R.G., Li C. Distribution of short to medium amylose chains are major controllers of in vitro digestion of retrograded rice starch. Food Hydrocolloids. 2019;96:634–643. doi: 10.1016/j.foodhyd.2019.06.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- González-Espinosa Y., Sabagh B., Moldenhauer E., Clarke P., Goycoolea F.M. Characterisation of chitosan molecular weight distribution by multi-detection asymmetric flow-field flow fractionation (AF4) and SEC. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules. 2019;136:911–919. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2019.06.122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guisbiers G., Wang Q., Khachatryan E., Mimun L., Mendoza-Cruz R., Larese-Casanova P., Nash K. Inhibition of E. coli and S. aureus with selenium nanoparticles synthesized by pulsed laser ablation in deionized water. International Journal of Nanomedicine. 2016;11:3731–3736. doi: 10.2147/ijn.s106289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo P., Li Y., An J., Shen S., Dou H. Study on structure-function of starch by asymmetrical flow field-flow fractionation coupled with multiple detectors: A review. Carbohydrate Polymers. 2019;226 doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2019.115330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo Y., Zhang W., Sun Y., Ye H., Shen S., Dou H. Asymmetrical flow field-flow fractionation combined with liquid chromatography enables rapid, quantitative, and structurally informative detection of resistant starch. Microchemical Journal. 2022;181 doi: 10.1016/j.microc.2022.107787. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Haq F., Yu H., Wang L., Teng L., Haroon M., Khan R.U., Nazir A. Advances in chemical modifications of starches and their applications. Carbohydrate Research. 2019;476:12–35. doi: 10.1016/j.carres.2019.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez-Hernandez O., Julio-Gonzalez L.C., Doyagüez E.G., Gutiérrez T.J. Potentially health-promoting spaghetti-type pastas based on doubly modified corn starch: starch oxidation via wet chemistry followed by organocatalytic butyrylation using reactive extrusion. Polymers. 2023;15(7):1704. doi: 10.3390/polym15071704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imberty A., Chanzy H., Pérez S., Buléon A., Tran V. Three-dimensional structure analysis of the crystalline moiety of A-starch. Food Hydrocolloids. 1987;1(5):455–459. doi: 10.1016/S0268-005X(87)80040-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Joensson J.A., Carlshaf A. Flow field flow fractionation in hollow cylindrical fibers. Analytical Chemistry. 1989;61(1):11–18. doi: 10.1021/ac00176a004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kammer F., Legros S., Hofmann T., Larsen E.H., Loeschner K. Separation and characterization of nanoparticles in complex food and environmental samples by field-flow fractionation. TRAC Trends in Analytical Chemistry. 2011;30(3):425–436. doi: 10.1016/j.trac.2010.11.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kang D., Moon M.H. Miniaturization of frit inlet asymmetrical flow field-flow fractionation. Analytical Chemistry. 2004;76(13):3851–3855. doi: 10.1021/ac0496704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim Y.B., Yang J.S., Moon M.H. Investigation of steric transition with field programming in frit inlet asymmetrical flow field-flow fractionation. Journal of Chromatography A. 2018;1576:131–136. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2018.09.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S., Kim S.T., Pant B.R., Kwen H.D., Song H.H., Lee S.K., Nehete S.V. Carboxymethylation of corn starch and characterization using asymmetrical flow field-flow fractionation coupled with multiangle light scattering. Journal of Chromatography A. 2010;1217(27):4623–4628. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2010.04.082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leeman M., Islam M.T., Haseltine W.G. Asymmetrical flow field-flow fractionation coupled with multi-angle light scattering and refractive index detections for characterization of ultra-high molar mass poly(acrylamide) flocculants. Journal of Chromatography A. 2007;1172(2):194–203. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2007.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li C., Li H., Gilbert R.G. Characterizing starch molecular structure of rice. Rice Grain Quality. 2019;1892:169–185. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-8914-0_10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang T., Xie X., Wu L., Li L., Yang L., Jiang T., Wu Q. Metabolism of resistant starch RS3 administered in combination with Lactiplantibacillus plantarum strain 84–3 by human gut microbiota in simulated fermentation experiments in vitro and in a rat model. Food Chemistry. 2023;411 doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2023.135412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Litzen A. Separation speed, retention, and dispersion in asymmetrical flow field-flow fractionation as functions of channel dimensions and flow rates. Analytical Chemistry. 1993;65(4):461–470. doi: 10.1021/ac00052a025. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Litzen A., Wahlund K.G. Zone broadening and dilution in rectangular and trapezoidal asymmetrical flow field-flow fractionation channels. Analytical Chemistry. 1991;63(10):1001–1007. doi: 10.1021/ac00010a013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Silva M., Bello-Perez L.A., Castillo-Rodriguez V.M., Agama-Acevedo E., Alvarez-Ramirez J. In vitro digestibility characteristics of octenyl succinic acid (OSA) modified starch with different amylose content. Food Chemistry. 2020;304 doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2019.125434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu K., Zhu J., Bao X., Liu H., Yu L., Chen L. Effect of starch microstructure on microwave-assisted esterification. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules. 2020;164:2550–2557. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2020.08.099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma P.L., Buschmann M.D., Winnik F.M. One-step analysis of DNA/chitosan complexes by field-flow fractionation reveals particle size and free chitosan content. Biomacromolecules. 2010;11(3):549–554. doi: 10.1021/bm901345q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma Z., Yin X., Hu X., Li X., Liu L., Boye J.I. Structural characterization of resistant starch isolated from Laird lentils (Lens culinaris) seeds subjected to different processing treatments. Food Chemistry. 2018;263:163–170. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2018.04.122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magnusson, E., & Nilsson, L. (2011). Interactions between hydrophobically modified starch and egg yolk proteins in solution and emulsions. Food Hydrocolloids, 25(4), 764-772. https://doi.org /10.1016/j.foodhyd.2010.09.006.

- Mélin C., Perraud A., Akil H., Jauberteau M.O., Cardot P., Mathonnet M., Battu S. Cancer stem cell ssorting from colorectal cancer cell lines by sedimentation field flow fractionation. Analytical Chemistry. 2012;84(3):1549–1556. doi: 10.1021/ac202797z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moon M.H., Giddings J.C. Extension of sedimentation/steric field-flow fractionation into the submicrometer range: Size analysis of 0.2-15-μm metal particles. Analytical Chemistry. 1992;64(23):3029–3037. doi: 10.1021/ac00047a027. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mudalige T.K., Qu H., Sánchez-Pomales G., Sisco P.N., Linder S.W. Simple functionalization strategies for enhancing nanoparticle separation and recovery with asymmetric flow field flow fractionation. Analytical Chemistry. 2015;87(3):1764–1772. doi: 10.1021/ac503683n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myers M.N., Giddings J.C. Properties of the transition from normal to steric field-flow fractionation. Analytical Chemistry. 1982;54(13):2284–2289. doi: 10.1021/ac00250a032. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nilsson L. Separation and characterization of food macromolecules using field-flow;fractionation: A review. Food Hydrocolloids. 2013;30(1):1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.foodhyd.2012.04.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Panyoo A.E., Emmambux M.N. Amylose-lipid complex production and potential health benefits: A mini-review. Starch - Stärke. 2017;69(7–8) doi: 10.1002/star.201600203. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Perez-Rea D., Zielke C., Nilsson L. Co-elution effects can influence molar mass determination of large macromolecules with asymmetric flow field-flow fractionation coupled to multiangle light scattering. Journal of Chromatography A. 2017;1506:138–141. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2017.05.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Podzimek S. Asymmetric flow field flow fractionation. Encyclopedia of Analytical Chemistry. 2012;1–19 doi: 10.1002/9780470027318.a9289. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ratanathanawongs Williams S.K., Lee D. Field-flow fractionation of proteins, polysaccharides, synthetic polymers, and supramolecular assemblies. Journal of Separation Science. 2006;29(12):1720–1732. doi: 10.1002/jssc.200600151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reschiglian P., Melucci D., Zattoni A., Malló L., Hansen M., Kummerow A., Miller M. Working without accumulation membrane in flow field-flow fractionation. Analytical Chemistry. 2000;72(24):5945–5954. doi: 10.1021/ac000608q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rolland-Sabaté A., Guilois S., Jaillais B., Colonna P. Molecular size and mass distributions of native starches using complementary separation methods: Asymmetrical flow field flow fractionation (A4F) and hydrodynamic and size exclusion chromatography (HDC-SEC) Analytical and Bioanalytical Chemistry. 2011;399(4):1493–1505. doi: 10.1007/s00216-010-4208-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schimpf M.E., Caldwell K., Giddings J.C. Wiley-Interscience; New York: 2000. Field flow fractionation handbook. [Google Scholar]

- Schimpf M.E., Myers M.N., Giddings J.C. Measurement of polydispersity of ultra-narrow polymer fractions by thermal field-flow fractionation. Journal of Applied Polymer Science. 1987;33(1):117–135. doi: 10.1002/app.1987.070330111. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Song T., Zhang W., Chen X., Zhang A., Guo S., Shen S., Dou H. Insights into the correlations between the size of starch at nano- to microscale and its functional properties based on asymmetrical flow field-flow fractionation. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules. 2021;193:500–509. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2021.10.090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tekin T., Dincer E. Effect of resistant starch types as a prebiotic. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology. 2023;107(2–3):491–515. doi: 10.1007/s00253-022-12325-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tester R.F., Karkalas J., Qi X. Starch—composition, fine structure and architecture. Journal of Cereal Science. 2004;39(2):151–165. doi: 10.1016/j.jcs.2003.12.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Thongsomboon W., Srihanam P., Baimark Y. Preparation of flexible poly(l-lactide)-b-poly(ethylene glycol)-b-poly(l-lactide)/talcum/thermoplastic starch ternary composites for use as heat-resistant and single-use bioplastics. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules. 2023;230 doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2023.123172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wahlund K.G. Flow field-flow fractionation: Critical overview. Journal of Chromatography A. 2013;1287:97–112. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2013.02.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wahlund K.G., Giddings J.C. Properties of an asymmetrical flow field-flow fractionation channel having one permeable wall. Analytical Chemistry. 1987;59(9):1332–1339. doi: 10.1021/ac00136a016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wahlund K.G., Leeman M., Santacruz S. Size separations of starch of different botanical origin studied by asymmetrical-flow field-flow fractionation and multiangle light scattering. Analytical and Bioanalytical Chemistry. 2011;399(4):1455–1465. doi: 10.1007/s00216-010-4438-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wahlund K.G., Winegarner H.S., Caldwell K.D., Giddings J.C. Improved flow field-flow fractionation system applied to water-soluble polymers: Programming, outlet stream splitting, and flow optimization. Analytical Chemistry. 1986;58(3):573–578. doi: 10.1021/ac00294a018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang S., Zuo Z., Wang Q., Zhou A., Wang G., Xu G., Zou J. Replacing starch with resistant starch (Laminaria japonica) improves water quality, nitrogen and phosphorus budget and microbial community in hybrid snakehead (Channa maculata ♀ × Channa argus ♂) Water Environment Research. 2023;95(2) doi: 10.1002/wer.10836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wen J.J., Li M.Z., Nie S.P. Dietary supplementation with resistant starch contributes to intestinal health. Current Opinion in Clinical Nutrition and Metabolic Care. 2023;26(4):334–340. doi: 10.1097/mco.0000000000000939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wittgren B., Wahlund K.G., Andersson M., Arfvidsson C. Polysaccharide characterization by flow field-flow fractionation-multiangle light scattering: Initial studies of modified starches. International Journal of Polymer Analysis and Characterization. 2002;7(1–2):19–40. doi: 10.1080/10236660214599. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Z., Zhao W., Yin Y., Wei Y., Liu Y., Zhu N., Liu J. Separation and characterization of biomacromolecules, bionanoparticles, and biomicroparticles using flow field-flow fractionation: Current applications and prospects. TrAC Trends in Analytical Chemistry. 2023;164 doi: 10.1016/j.trac.2023.117114. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yee J., Roman L., Pico J., Aguirre-Cruz A., Bello-Perez L.A., Bertoft E., Martinez M.M. The molecular structure of starch from different Musa genotypes: Higher branching density of amylose chains seems to promote enzyme-resistant structures. Food Hydrocolloids. 2021;112 doi: 10.1016/j.foodhyd.2020.106351. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yoo Y., Choi J., Zielke C., Nilsson L., Lee S. Fluorescence-labelling for analysis of protein in starch using asymmetrical flow field-flow fractionation (AF4) Analytical Science and Technology. 2017;30(1):1–9. doi: 10.5806/ast.2017.30.1.1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zattoni A., Rambaldi D.C., Casolari S., Roda B., Reschiglian P. Tandem hollow-fiber flow field-flow fractionation. Journal of Chromatography A. 2011;1218(27):4132–4137. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2011.02.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang W., Shen S., Song T., Chen X., Zhang A., Dou H. Insights into the structure and conformation of potato resistant starch (type 2) using asymmetrical flow field-flow fractionation coupled with multiple detectors. Food Chemistry. 2021;349 doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2021.129168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang W., Wang J., Guo P., Dai S., Zhang X., Meng M., Dou H. Study on the retrogradation behavior of starch by asymmetrical flow field-flow fractionation coupled with multiple detectors. Food Chemistry. 2019;277:674–681. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2018.11.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu F., Liu P. Starch gelatinization, retrogradation, and enzyme susceptibility of retrograded starch: Effect of amylopectin internal molecular structure. Food Chemistry. 2020;316 doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2019.126036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zielke C., Fuentes C., Piculell L., Nilsson L. Co-elution phenomena in polymer mixtures studied by asymmetric flow field-flow fractionation. Journal of Chromatography A. 2018;1532:251–256. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2017.12.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.