Abstract

Background

American Indians face significant barriers to diagnosis and management of cardiovascular disease. We sought to develop a real‐world implementation model for improving access to echocardiography within the Indian Health Service, the American Indian Structural Heart Disease Partnership.

Methods and Results

The American Indian Structural Heart Disease Partnership was implemented and evaluated via a 4‐step process of characterizing the system where it would be instituted, building point‐of‐care echocardiography capacity, deploying active case finding for structural heart disease, and evaluating the approach from the perspective of the clinician and patient. Data were collected and analyzed using a parallel convergent mixed methods approach. Twelve health care providers successfully completed training in point‐of‐care echocardiography. While there was perceived usefulness of echocardiography, providers found it difficult to integrate screening point‐of‐care echocardiography into their workday given competing demands. By the end of 12 months, 6 providers continued to actively utilize point‐of‐care echocardiography. Patients who participated in the study felt it was an acceptable and effective approach. They also identified access to transportation as a notable challenge to accessing echocardiograms. Over the 12‐month period, a total of 639 patients were screened, of which 36 (5.6%) had a new clinically significant abnormal finding.

Conclusions

The American Indian Structural Heart Disease Partnership model exhibited several promising strategies to improve access to screening echocardiography for American Indian populations. However, competing priorities for Indian Health Service providers' time limited the amount of integration of screening echocardiography into outpatient practice. Future endeavors should explore community‐based solutions to develop a more sustainable model with greater impact on case detection, disease management, and improved outcomes.

Keywords: American Indian, echocardiography, health care access, heart disease

Subject Categories: Disparities, Health Services, Digital Health

Nonstandard Abbreviations and Acronyms

- IHS

Indian Health Service

- IN‐STEP

American Indian Structural Heart Disease Partnership

- POC

point‐of‐care

- SHD

structural heart disease

Clinical Perspective.

What Is New?

Indian Health Service providers unfamiliar with echocardiography can be successfully trained to obtain point‐of‐care screening echocardiograms with sufficient image quality, improving timely access to echocardiographic services for American Indians.

Almost 6% of American Indians screened had a new clinically significant abnormal finding.

Point‐of‐care screening echocardiograms integrated into clinical practice was an acceptable approach for patients receiving screening echocardiograms.

What Are the Clinical Implications?

Proven strategies in low‐ and middle‐income countries, such as task shifting, can be utilized within the United States to improve access to echocardiography for American Indians living in remote settings.

Further study is needed to determine the impact of screening echocardiography in disease detection and management.

While the approach of integrating point‐of‐care echocardiography into the clinical setting of the Indian Health Service was acceptable, the impact was limited by competing demands on providers; future endeavors should explore community‐based solutions to establish sustainable solutions.

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is a leading contributor to mortality for American Indians, with rates of coronary heart disease twice that of the general US population. 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 American Indians develop CVD at an earlier age, with mortality rates 30% higher for those age 25 to 44 years compared with their non‐Hispanic White counterparts. 3 While coronary heart disease and stroke have been well studied in American Indian populations, limited information is available on other CVD such as structural heart disease (SHD) including heart failure and valvular disease.

American Indian populations face significant economic and social adversity, whose roots can be traced back to racism and unjust treatment during colonial times. 1 , 5 Currently, this manifests as significant barriers to healthy living and health care access, including geographic isolation with limited transportation, inadequate housing, phone access, and health services, high rates of poverty, lower rates of educational attainment, and cultural and language barriers to care. 1 , 6 Specific to CVD, this manifests as barriers to diagnosis and management, with patients often required to travel significant distances for echocardiograms and specialty cardiology care. For 1 American Indian tribe in Eastern Arizona, patients travel 3 to 4 hours for cardiac evaluation, contributing to late diagnosis and suboptimal care.

Given this, we sought to develop a real‐world implementation model for improving access to echocardiography within the Indian Health Service (IHS). Utilizing strategies proven effective within low‐ and middle‐income countries, 7 , 8 , 9 the American Indian Structural Heart Disease Partnership (IN‐STEP) aimed to integrate point‐of‐care (POC) echocardiography into primary care clinics to improve access to echocardiography, facilitate CVD diagnosis and management, and ultimately improve outcomes.

Methods

This study was approved by the Cincinnati Children's Hospital and Medical Center and Phoenix Area Indian Health Service Institutional Review Boards and the participating Tribal Council. All study participants provided written consent and/or assent (children ages 8 years and older) for participation in the study and all study procedures were in line with institutional policies and guidelines. First author S.L. had full access to all study data and takes responsibility for its integrity and data analysis. The unidentifiable data supporting the findings of this study may be available upon request to the corresponding author.

Our overall study design was a parallel convergent mixed methods approach to data collection and analysis. Deployment and evaluation of the IN‐STEP model was conducted in 4 steps, including Step 1: characterize the system where IN‐STEP would be deployed, Step 2: build POC echocardiography capacity, Step 3: deploy active case finding for structural heart disease, and Step 4: evaluation of the approach from the perspective of the clinician and patient (Figure 1). The various assessment tools utilized during each step are outlined in Table 1. 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 Additional details can be found in Data S1 and Figure S1.

Figure 1. American Indian Structural Heart Disease Partnership (IN‐STEP).

The 4‐step method used to deploy and evaluate IN‐STEP within the Indian Health Service (IHS) hospital. Echo indicates echocardiography; and POC, point‐of‐care.

Table 1.

Assessment Tools Utilized For Each Step of IN‐STEP

| Organizational Readiness for Implementing Change | Modified Technology Acceptance model | Health Care Access Survey | Semistructured Interviews | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Step 1: Characterization of the system where IN‐STEP would be deployed | ||||

| Acronym | ORIC Survey 10 | Modified TAM 11 , 12 | N/A | N/A |

| Brief description | 12 Likert scale (5‐point) items measuring readiness for change at the collective level within the domains of change commitment (5 questions) and change efficacy (7 items) | 8 Likert scale (7‐point) items designed to explain and predict system use along the domains of perceived usefulness (4 questions) and perceived ease of use (4 questions) | De novo survey on health care access and acceptability of echocardiography | Informed by the modified TAM to explore perceptions of usefulness and ease of using POC echo, patient and community‐level responsiveness to using echo for screening |

| Interpretation | Higher score indicates increased readiness | Higher score indicates greater likelihood of use | N/A | N/A |

| Target | Wide range of IHS employees including administrators, providers, nurses, pharmacists, and health techs (goal n=35) | IHS providers who participated in POC echo training (goal n=10) | General community members (goal n=50) | Sampled providers, administrators, and patients (goal n=40) |

| Administration | E‐mail distribution to employees of the participating IHS unit | In‐person during 2‐day intensive training | In‐person, time of study enrollment and POC echo | In‐person |

| Step 2: Build POC echo capacity | ||||

| American College of Emergency Physicians Quality Assessment 13 | Rapid Competency Assessment | Echocardiography Training Evaluation | Small Group Feedback | |

| Acronym | ACEP grade | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Brief description | 5Level grading scale used for quality assessment of image quality | Binary assessment of 8 skills related to performing echo with acquiring quality images | De novo short survey composed of 4 Likert‐scale questions and 2‐open‐ended questions to assess feedback on training | Small group discussion with 5–6 IHS providers and facilitated by research staff to elicit feedback on echo training process |

| Interpretation | Higher score indicates improved image quality | Skills/images assessed as competent or not competent | N/A | N/A |

| Target | IHS providers who participated in POC echo training (goal n=10) | IHS providers who participated in POC echo training (goal n=10) | IHS providers who participated in POC echo training (goal n=10) | IHS providers who participated in POC echo training (goal n=10) |

| Administration | In‐person at end of 2‐day intensive training | In‐person at end of 2‐day intensive training | In‐person at end of 2‐day intensive training | In‐person at end of 2‐day intensive training |

| Step 3: Deploy active case finding | ||||

| Total number of Screening Studies | Normal vs Abnormal Scans | IHS Provider Interpretation vs Expert Interpretation | SemistructuredIinterviews (for details, see above) | |

| Step 4: Evaluate the approach | ||||

| Patient Echo Acceptability Survey | Provider Integration Survey | Semistructured Interviews | ||

| Acronym | N/A | N/A | ||

| Brief description | De novo survey of 9 Likert‐scale questions (6 points) and 3 open‐ended questions to assess patient acceptance of echo screening | De novo short 3‐question survey (2 Likert‐scale questions | See above for details | |

| Interpretation | Higher score indicated increased acceptance | |||

| Target | Patients receiving a POC screening echo (n=50) | |||

| Administration | In‐person, time of study enrollment following POC echo | 6 Months following echo integration into clinical practice | ||

ACEP indicates American College of Emergency Physicians; echo, echocardiography; IHS, Indian Health Service; IN‐STEP, American Indian Structural Heart Disease Partnership; N/A, not applicable; ORIC, Organizational Readiness for Implementing Change; POC, point‐of‐care; and TAM, Technology Acceptability Model.

Quantitative data were collected and managed using REDCap electronic data capture tools 14 , 15 hosted at Cincinnati Children's Hospital and Medical Center (grant UL1TR001425). Qualitative data were collected via semistructured key informant interviews. Interviews occurred between October and November, 2022 and were conducted at the Indian Health Service Hospital serving the study population. We used a modified Technology Acceptance Model to inform the development of interview guides that explored perceptions of the usefulness and ease of using POC echocardiography as well as patient‐ and community‐level responsiveness to using echocardiography for screening. A list of stakeholders for POC echocardiography integration was generated by a project team member who is a member of the Tribe (L.B.) and is familiar with the local tribal community. We also solicited input from staff at the regional IHS Hospital. We purposively sampled 3 categories of respondents (providers, administrators, and patients) from this sample frame. All interviews were conducted in English and ranged from 30 to 60 minutes. Structured postinterview debriefs were completed within 48 hours of all interviews with at least 2 members of the study team. All interviews were audio recorded and transcribed verbatim.

Statistical Analysis

Quantitative Data

Descriptive statistics were used to enumerate the distribution of key variables, such as study participant demographics. Survey results were described using means with SDs or frequencies with the percent of total.

Qualitative Analysis

We used thematic analysis to understand the data. 16 An initial codebook was developed from key constructs in the Technology Acceptance Model and early concepts identified during debriefing. Two coders (S.L. and K.D.) then deductively coded 2 transcripts using these predefined codes, and inductively coded emergent ideas not captured by the predefined codebook. New concepts identified during this initial coding were discussed and harmonized and a final codebook was created. K.D. and S.D. used a consensus coding process to complete coding of the remaining interviews. We used web‐based Atlas.ti for data management and to facilitate analysis.

Results

Step 1: Characterize the System

System Considerations

The Organizational Readiness for Implementing Change survey was completed by 25 of 41 recipients (61%) including administrators (n=4), physicians (n=9), advanced practice providers (n=5), nurses (n=4), and pharmacists (n=3). The overall mean score was 51.8 (SD 6.5) out of a possible 60, with a component score for change efficacy of 29.8 (SD 4.2) out of 35 and change commitment of 22.0 (SD 2.7) out of 25, suggesting that participants embarked on the IN‐STEP program with a sense of readiness for change. Mean scores were similar across role and primary work location (Table 2).

Table 2.

ORIC Survey Responses by Role and Location (N=25)

| Variable | N (%) | ORIC score, mean (SD) |

|---|---|---|

| Clinical role | ||

| Physician | 9 (36%) | 52.1 (6.8) |

| Advanced practice provider (NP or PA) | 5 (20%) | 50.8 (6.2) |

| Nurse | 4 (16%) | 55.5 (6.2) |

| Pharmacist | 3 (12%) | 50.0 (7.3) |

| Administrator | 4 (16%) | 52.0 (4.6) |

| Primary work location | ||

| Outpatient | 20 (80%) | 52.6 (6.7) |

| Emergency department | 5 (20%) | 48.8 (4.7) |

NP indicates nurse practitioner; ORIC, Organizational Readiness for Implementing Change; and PA, physician assistant.

During interviews, staff at the IHS hospital also shared a desire to be on the cutting edge of care and repeatedly expressed a sense of exceptionality of their organization within the IHS system. This emerged as a strong intrinsic motivator to providers, suggesting that positioning echocardiography for screening as part of that standard is likely to facilitate uptake. “It sounded interesting, first and foremost. And I felt that it would be a benefit to the facility. I thought that it had the potential to have good utility for our patient population. And I'm very much in favor of nontraditional expansions to one's practice, so I was excited to jump on” (04, provider).

Provider Considerations

All 12 participants consented for echocardiography training completed a modified Technology Acceptability Model survey. The mean score of perceived usefulness was 21.4 (SD 3.2) out of 28 and for perceived ease of use was 18.3 (SD 4.3) out of 28, suggesting that providers recognized the utility of POC echocardiography but also anticipated associated effort in integrating POC echocardiography into their practice (Table 3). These attitudes were reflected in the interviews, where providers acknowledged the potential of echocardiography but also the hurdles that would need to be overcome to effectively incorporate POC echocardiography. Providers identified establishing the benefit of POC echocardiography screening to patients as an indispensable initial step for its use in routine care. Benefits described included not only the effectiveness of POC echocardiography for identifying undiagnosed conditions, but also for reducing time and transportation burdens on patients. “I think getting providers to do it is [going to] come down to first being able for them to recognize that it's justified, it's a need and there's a definite benefit for their patients” (05, administrator).

Table 3.

Modified Technology Acceptability Model Responses by Question

| Construct | Question | Score mean (SD) |

|---|---|---|

| Perceived usefulness | Using POC echo improves my performance in my job | 5.42 (0.95) |

| Using POC echo in my job increases my productivity | 4.58 (1.11) | |

| Using POC echo enhances my effectiveness in my job | 5.42 (0.86) | |

| I find POC echo to be useful in my job | 6.0 (1.0) | |

| Overall score | 21.42 (3.22) | |

| Perceived ease of use | My interaction with POC echo is clear and understandable | 5.58 (1.11) |

| Interacting with POC echo does not require a lot of my mental effort | 3.75 (1.74) | |

| I find POC echo to be easy to use | 4.58 (1.49) | |

| I find it easy to get POC echo to do what I want it to do | 4.41 (1.26) | |

| Overall score | 18.33 (4.25) |

Echo indicates echocardiogram; and POC, point‐of‐care.

Despite consistent acknowledgement of its importance, respondents expressed that effectively convincing providers of POC of the usefulness of echocardiography would require patience. For cadres of providers who see echocardiography as beyond the scope of their current mandate, echocardiography must be perceived as useful enough to be formally added to their competencies and negotiated responsibilities, a higher bar than just belief in screening effectiveness. More broadly, respondents felt that IN‐STEP could have a general reluctance to try new things. “I think it'll take a while to get there. And partly because we don't know, I don't know yet if doing routine echoes makes a clinical difference. My intuition is it would, but I think the providers will have to believe it does” (02, administrator). Similarly, “I think there's a human ingrained resistance to change. In general, people are resistant to change” (05, provider).

Respondents offered several suggestions for how to engage and increase buy‐in. Champions were suggested as an approach that had been used successfully in the past, where a person who is a colleague becomes the local expert on routine echocardiography and shows by lived example how it is beneficial to their patients. While having relevant, traditional quantitative measures, such as diagnoses rates, was hypothesized to be beneficial, providers also called out the power of patient stories and the persuasiveness of experience as a determinant of perceived usefulness. “All it'll take is one 17‐year‐old that they did the echo on and they found hypertrophic cardiomyopathy and they're like, Oh my gosh, this is so good, I better do it on everybody, you know… We like to think we're statistically scientifically driven, but we're also strongly driven by the story of the individual” (02, administrator).

Patient Considerations

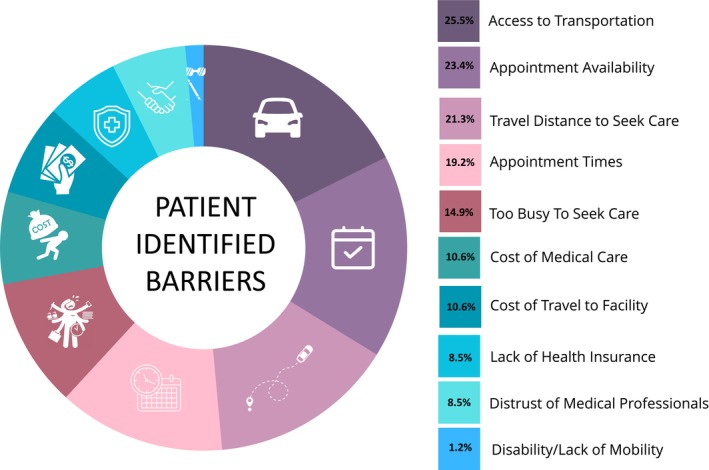

A total of 47 participants (goal n=50) completed a Health Care Access Survey; 23 of them (48.9%) were female, their average age was 44.1 years, 14 (29.8%) had less than a high school education, and 8 (17.0%) were unemployed. The majority owned a vehicle (29, 61.7%) and had an annual household income ≤$50 000 (36, 76.6%; 22 of these having an annual household income ≤$25 000). When asked about 10 potential barriers to seeking medical care, 16 (34.0%) identified no barriers, 13 (27.7%) identified 1 barrier, 7 (14.9%) identified 2 barriers, 7 (14.9%) identified 3 barriers, and 4 (8.5%) identified ≥4 barriers. The most common barriers reported were access to transportation (25%), long waits for appointments (23%), and distance to travel to seek care (21%). A full list of barriers is provided in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Barriers to receiving health care.

Patient barriers to receiving health care as reported from the Health Care Access Survey (n=47). The survey asked about 10 potential barriers, and positive response rates are reported next to each potential barrier.

Throughout the interviews, patients and providers also referenced transportation as the most notable challenge patients faced while trying to access cardiac echocardiography in the current system. While provider perceptions of this challenge generally focused on the length of time patients spent navigating the referral process, the sense of frustration emerging from the patient interviewee centered on the unpredictability and disorganization of the transportation options. The main consequences of each aspect were missed appointments and delays in receiving a diagnosis. “The transportation, they're not reliable. I missed two of my appointments this past summer because the first time they didn't have a driver. The second time they said, I don't know, I would like to find out, but I just let it go. They said that my appointment was canceled, and here I had to call down and tell them that my ride never came” (06, patient).

In addition to travel to appointments, there are multiple steps involved in patients getting echocardiograms, including completing referral paperwork, appointment scheduling at outside facilities (availability and connecting patients with schedulers), and getting results returned. Providers described a process that takes months for patients to go from indication to result, which can be clinically significant. “It was and remains extremely difficult to get an echocardiogram at another facility in a timely fashion. Unless that patient is already an inpatient and getting [an echo] as part of an inpatient workup, but as an outpatient, the delay could be months in plural before we get the study results” (01, provider). Providers expressed optimism that increasing the use of echocardiography at IHS would alleviate these concerns and provide a more convenient experience for patients.

Step 2: Build POC Echocardiography Capacity

A total of 12 health care providers working within internal medicine or family medicine to provide primary care services participated in the POC echocardiography training (6 physicians, 3 medical assistants, 2 nurse practitioners, and 1 clinical pharmacist). Of these, 6 (50.0%) were female, 2 (16.7%) had <1 year experience in their role, and 4 (33.3%) had >10 years' experience in their role. Only 1 provider had some prior experience with echocardiography (received training during residency and used in the emergency department), and 7 had some prior experience performing ultrasound (mostly used it for establishing intravenous access and performing paracentesis).

After the training, 6 of 12 providers (50%) passed every component of the rapid competency assessment. For the remaining 6, the 2 most common areas of incompetency were completing the examination in the allotted time (4 took longer than the allotted 15 minutes) and acquiring images that were of diagnostic quality (4 of 6 did not get high‐quality images in 1 of 2 standardized patients). Only 1 provider failed these areas of evaluation for both standardized patients.

The EchoNous Kosmos devices were well received. Providers felt the devices were user friendly (“only two days and feel comfortable using the device”) and enjoyed receiving immediate feedback. Group reflection on the training suggested that, overall, it was well organized and useful. Identified areas for improvement included more hands‐on time, earlier presentation of the scanning protocol, provider‐specific training (rather than training a mixture of roles together), a desire for more supplemental materials including visual reference sheets, copies of the lecture slides, and additional imaging clips to supplement the Global Ultrasound Institute modules, and more diversity in standardized patient selection. One comment reflects the overall tenor from the trainees: “I have been nervous for years to begin echo +/‐ ultrasound training, but this training totally overcame my fears.”

Step 3: Deploy Active Case Finding for SHD

Screening echocardiograms were conducted in 639 patients over 12 months of the IN‐STEP program. Of these, 91 were abnormal, and 36 (5.6%) had a new clinically significant abnormal finding.

There was good agreement between provider interpretation and expert interpretation. Overall, trainee‐to‐expert interpretation had ≥80% agreement for left and right ventricular size and function, and mitral and aortic valve structure. This agreement was less for valve stenosis (mitral stenosis 76%, aortic stenosis 69%) and regurgitation (mitral regurgitation 67%, and aortic regurgitation 63%), but these pathologies were less frequently observed.

When discussing their experience of scanning, providers raised concerns over their own ability to master and interpret echocardiography studies. “I think the thing I am most anxious about, I guess for the lack of a better word, is getting, or in terms of my interpretation is missing something small, missing something that is sort of on the border between normal and abnormal” (04, provider) and “I do believe that the technology has been easier to use as I have used it more often. But that still doesn't mean, by any means that I have the ability to get beautiful, technically adequate views on every patient that I see, even though I continued to use the echo machines” (01, provider).

Step 4: Evaluate the Approach

Patient Considerations

A total of 50 patients completed an echocardiography acceptability survey; 26 (52.0%) of the patients were female with an average age of 43.8 years. Mean score across domains was 5.4 (SD 0.2), with scores >5 (out of 6) for 8 of 9 questions (Table 4).

Table 4.

Patient Responses to 6‐Point Likert Questions on Echocardiography Acceptability Survey

| Question | Mean score (SD) |

|---|---|

| Acceptable screening tool for structural heart disease | 5.4 (1.4) |

| Echo should be effective in identifying structural heart disease | 5.4 (1.4) |

| The risk of structural heart disease is severe enough to justify an echocardiogram | 5.2 (1.5) |

| I would be willing to have an echocardiogram for my child | 4.9 (1.7) |

| The echocardiogram did not have bad side effects for me | 5.6 (1.3) |

| I liked the echocardiogram | 5.6 (1.2) |

| The echo was a good way to screen for structural heart disease | 5.7 (1.1) |

| Overall the echocardiogram helped me | 5.6 (1.1) |

When asked about what they liked most about the process of getting an echocardiogram, patients cited having their heart checked and the knowledge that came from that (21, 42.0%: “knowing my heart is strong”). Patients also referenced the ability to visualize their heart (6, 12.0%: “never seen my heart pumping in my life and it was cool to see it”), ease of the process (11, 22.0%: “it came to me, was easy to do”), staff performing the echocardiogram (4, 8.0%: “friendly staff”), lack of discomfort (4, 8.0%; “it was calming; it didn't hurt”), and being informed about the process (1, 2.0%: “being informed about the process and explaining to me about the procedure”). With regard to what they liked least about the process, the most common response was nothing (26, 52.0%), followed by the need for exposure (5, 10.0%), and aspects inherent to an echocardiogram (trying to find a good view: 1, 2.0%; pressure: 3, 6.0%; cold gel: 7, 14.0%; moving to another room: 1, 2.0%). Reasons cited that people may choose not to have an echocardiogram performed included time commitment (5, 10.0%), fear and not wanting to discover any cardiac abnormalities (11, 22.0%: “most don't like knowing their future and wouldn't want to know something wrong with their heart”), need for getting undressed (5, 10.0%), not understanding indication (3, 6.0%: “probably not understand what it's for”), and novelty (2, 4.0%: “it's too new to them”). At least 1 provider pointed to general distrust of research in the community as a cause of lack of engagement. “People had to believe that what you're doing was to their advantage and that it wasn't experimental in the classic sense of a clinical trial” (02, administrator).

Provider Considerations

Eight providers (8/12, 75%) completed the provider integration survey (4 physicians, 3 medical assistants, 1 nurse practitioner). Overall themes were that 6 of 8 found it very or somewhat difficult to integrate echocardiography into the workday, and 7 of 8 found echocardiography either very or slightly disruptive to workflow. Regarding reasons for not performing an echocardiogram during clinic, all referenced competing demands and trying to remain on schedule for appointments (“overbooked clinic with 100% show rate and 20‐minute slots”).

One theme that emerged during the interviews was that IN‐STEP operating as a research project added perceived cultural and logistic obstacles to its implementation. Echocardiograms took longer than they might have otherwise because patients needed to be consented into the study. These requirements fed into the cascading effect of adding time to primary care visits. Respondents felt that staff might be more reticent to engage in a study given that the IHS hospital is not a research institution and thus study participation is not a requirement of the provider role.

The value of POC echocardiography for screening with respect to streamlining provider workload surfaced as a core perceived determinant of adoption. Providers and administrators alike pointed to onsite echocardiography's potential to remove the bureaucratic burdens on providers associated with managing the referral process. However, there was a learning curve associated with integrating use of echocardiography screening into routine primary care. One of the main integration strategies tested in IN‐STEP added substantial time to already compressed patient visits. This created a tension between the need for repetition to improve provider efficiency capturing POC echocardiogram images and the high time burden experienced by early adopters. “It's a difficult situation because the more echoes a provider does, the more comfortable and expeditious they will be with performing the echocardiogram. However, that initial process might result in so much frustration from patients and the provider that they end up not doing that” (01, provider). The absence of a system for integrating POC echocardiography for screening into provider workflows curtailed their uptake. Participants felt that building the time for echocardiography into primary care visit scheduling would facilitate routine use by providers and reduce the countervailing pressures of going over allotted appointment times during primary care.

Approximately 1 year from completion of the training activities, 6 providers continued to actively obtain screening echocardiograms. One provider has completed the Point‐of‐Care Ultrasound Certification Academy Fundamentals and Clinical Cardiac certificates, with 5 additional providers enrolled for future completion.

Interviews

For the interviews, we contacted 13 stakeholders across all stakeholder categories, and conducted 6 interviews (46%), including 2 patients, 3 providers, and 2 IHS administrators. All providers and administrators were male, were employed at the local IHS hospital, and 2 had taken part in in‐service echocardiography training as part of the IN‐STEP project. Providers had conducted an average of 12.5 echocardiograms at the time of the interview. Both patients were members of the Tribe; 1 was female and 1 was male, and both received an echocardiogram for screening as part of the IN‐STEP program.

Discussion

The IN‐STEP model demonstrated that utilizing proven strategies used in low‐ and middle‐income countries such as task shifting 7 , 17 , 18 can be successfully translated to settings within the United States to help improve access to echocardiography for American Indian populations in remote settings. The approach to training was overall well received, though several areas for improvement were identified by participants including increasing diversity of standardized patients, further time for hands‐on practice, and additional presentation of pathology images/clips. Various approaches to training nonexpert users have been previously examined with mixed results of final skills assessment. 18 , 19 , 20 , 21 As part of their approach to integrating screening echocardiography into primary care, Nascimento et al 18 integrated 4 previously trained nonphysicians with 2 years of echocardiography expertise into the primary care centers to optimize screening efforts. While successful, this approach would require significant financial and personnel investment to scale in the United States. Alternate future considerations to augment training include follow‐up skills refreshers, group review of images, and focused lectures on echocardiography techniques and interpretation to enhance learning and promote provider engagement, leveraging videoconferencing to facilitate remote learning sessions. While recommendations and competency certifications have been more formally established for those using POC echocardiography to aid clinical care within acute‐care settings, this is not as clearly established for those utilizing POC echocardiography outside the critical setting and for screening purposes (a consideration as the use of POC echo continues to expand, particularly in more remote and low‐access areas). Continued innovations within artificial intelligence hold significant promise in improving not only image acquisition but also image interpretation. 22 Augmenting the training process and potential artificial intelligence–assisted image interpretation may help not only nonexpert skills acquisition, but also long‐term participant retention (only 50% of those trained went on to pursue certification 1 year after initial training).

Incorporation of POC echocardiography into the primary care clinic was acceptable to patients, who reported it was a good experience and felt the approach was an effective way to screen for SHD. Patients referenced the convenience and ease of the process, a notable benefit in a community where transportation and travel distance were 2 of the most commonly reported barriers to seeking medical care. IN‐STEP also demonstrated an important diagnostic gap, finding that nearly 1 in 17 American Indians, screened as part of this study, were living with undiagnosed SHD. If this rate was applied to the estimated 18 000 American Indian study population, this would translate to an additional 1000 American Indians living with undiagnosed SHD; if extrapolated to rural IHS sites nationally, our findings suggest that number is over 100 000.

While the approach used in this study was acceptable, large patient volumes and competing priorities for providers within the IHS limited the true integration of screening echocardiography into practice. Creating a dedicated echocardiography clinic helped to address this limitation, but this model may not be feasible in other settings, nor sustainable in the long run. Future considerations for the IN‐STEP model should explore community‐based solutions to identify more sustainable approaches. For example, Community Health Representative Programs are largely IHS‐funded, tribally governed outreach programs designed to address unmet health needs in the community. 23 , 24 These programs could offer an innovative and transformative approach to SHD detection and management that may be more widely accepted by the community and offer a more sustainable model for the IN‐STEP program to improve SHD outcomes.

Limitations

While feedback provided by patients was overall favorable, there was minimal data captured from participants who declined participation; therefore, these perspectives on the IN‐STEP approach are not captured. Another limitation is that our study was performed at a single facility. Given significant variability among IHS sites across the country, our findings are not generalizable to other IHS sites.

Conclusions

The IN‐STEP model exhibited several promising strategies to improve access to screening echocardiography for American Indian populations. Incorporating lessons learned to expand the training curriculum and root the model within a community‐based program that partners with the IHS should be explored as a more sustainable model to have a greater impact on not only case detection but also disease management and improved outcomes.

Sources of Funding

This work was supported by Place Outcomes Research Award 315148, Edward LifeSciences, and Every Heartbeat Matters 314911.

Disclosures

None.

Supporting information

Data S1.

Figure S1.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge and thank the providers and sonographers who donated their time and effort to help with echocardiography training and screening efforts.

This manuscript was sent to Francoise A. Marvel, MD, Guest Editor, for review by expert referees, editorial decision, and final disposition.

Supplemental Material is available at https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/suppl/10.1161/JAHA.123.031231

For Sources of Funding and Disclosures, see page 10.

References

- 1. Disparities. Indian Health Service . US Department of Health and Human Services. Updated October 2019. https://www.ihs.gov/newsroom/factsheets/disparities/ Accessed February 21, 2023.

- 2. Boyd AD, Fyfe‐Johnson AL, Noonan C, Muller C, Buchwald D. Communication with American Indians and Alaska Natives about cardiovascular disease. Prev Chronic Dis. 2020;17:E160. doi: 10.5888/pcd17.200189 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Breathett K, Sims M, Gross M, Jackson EA, Jones EJ, Navas‐Acien A, Taylor H, Thomas KL, Howard BV. Cardiovascular health in American Indians and Alaska Natives: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2020;141:e948–e959. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000773 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Howard BV, Lee ET, Cowan LD, Devereux RB, Galloway JM, Go OT, Howard WJ, Rhoades ER, Robbins DC, Sievers ML, et al. Rising tide of cardiovascular disease in American Indians. The Strong Heart Study. Circulation. 1999;99:2389–2395. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.99.18.2389 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kruse G, Lopez‐Carmen VA, Jensen A, Hardie L, Sequist TD. The Indian Health Service and American Indian/Alaska Native health outcomes. Annu Rev Public Health. 2022;43:559–576. doi: 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-052620-103633 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Galloway JM. Cardiovascular health among American Indians and Alaska Natives: successes, challenges, and potentials. Am J Prev Med. 2005;29:11–17. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2005.07.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Scheel A, Ssinabulya I, Aliku T, Bradley‐Hewitt T, Clauss A, Clauss S, Crawford L, DeWyer A, Donofrio MT, Jacobs M, et al. Community study to uncover the full spectrum of rheumatic heart disease in Uganda. Heart. 2019;105:60–66. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2018-313171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Peck D, Rwebembera J, Nakagaayi D, Minja NW, Ollberding NJ, Pulle J, Klein J, Adams D, Martin R, Koepsell K, et al. The use of artificial intelligence guidance for rheumatic heart disease screening by novices. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2023;36:724–732. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2023.03.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. de Araújo JS, Regis CT, Gomes RG, Mourato FA, Mattos SD. Impact of telemedicine in the screening for congenital heart disease in a center from Northeast Brazil. J Trop Pediatr. 2016;62:471–476. doi: 10.1093/tropej/fmw033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Shea CM, Jacobs SR, Esserman DA, Bruce K, Weiner BJ. Organizational readiness for implementing change: a psychometric assessment of a new measure. Implement Sci. 2014;9:7. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-9-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Davis FD. Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and user acceptance of information technology. MIS Q. 1989;13:319–340. doi: 10.2307/249008 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Venkatesh V, Bala H. Technology acceptance model 3 and a research agenda on interventions. Decis Sci. 2008;39:273–315. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-5915.2008.00192.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13. DeMasi S, Taylor LA, Weltler A, Wiggins JC, Wayman J, Wang C, Evans DP, Balderston JR. Novel quality assessment methodology in focused cardiac ultrasound. Acad Emerg Med. 2022;29:1261–1263. doi: 10.1111/acem.14562 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Harris PA, Taylor R, Minor BL, Elliott V, Fernandez M, O'Neal L, McLeod L, Delacqua G, Delacqua F, Kirby J, et al. The REDCap consortium: building an international community of software platform partners. J Biomed Inform. 2019;95:103208. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2019.103208 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—a metadata‐driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42:377–381. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3:77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ubels J, Sable C, Beaton AZ, Nunes MCP, Oliveira KKB, Rabelo LC, Teixeira IM, Ruiz GZL, Rabelo LMM, Tompsett AR, et al. Cost‐effectiveness of rheumatic heart disease echocardiographic screening in Brazil: data from the PROVAR+ study: cost‐effectiveness of RHD screening in Brazil. Glob Heart. 2020;15:18. doi: 10.5334/gh.529 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Nascimento BR, Beaton AZ, Nunes MCP, Tompsett AR, Oliveira KKB, Diamantino AC, Barbosa MM, Lourenço TV, Teixeira IM, Ruiz GZL, et al. Integration of echocardiographic screening by non‐physicians with remote reading in primary care. Heart. 2019;105:283–290. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2018-313593 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Waweru‐Siika W, Barasa A, Wachira B, Nekyon D, Karau B, Juma F, Wanjiku G, Otieno H, Bloomfield GS, Sloth E. Building focused cardiac ultrasound capacity in a lower middle‐income country: a single centre study to assess training impact. Afr J Emerg Med. 2020;10:136–143. doi: 10.1016/j.afjem.2020.04.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. DeWyer A, Scheel A, Otim IO, Longenecker CT, Okello E, Ssinabulya I, Morris S, Okwir M, Oyang W, Joyce E, et al. Improving the accuracy of heart failure diagnosis in low‐resource settings through task sharing and decentralization. Glob Health Action. 2019;12:1684070. doi: 10.1080/16549716.2019.1684070 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Beaton A, Nascimento BR, Diamantino AC, Pereira GT, Lopes EL, Miri CO, Bruno KK, Chequer G, Ferreira CG, Lafeta LC, et al. Efficacy of a standardized computer‐based training curriculum to teach echocardiographic identification of rheumatic heart disease to nonexpert users. Am J Cardiol. 2016;117:1783–1789. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2016.03.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Nascimento BR, Sable C, Nunes MCP, Diamantino AC, Oliveira KKB, Oliveira CM, Meira ZMA, Castilho SRT, Santos JPA, Rabelo LMM, et al. Comparison between different strategies of rheumatic heart disease echocardiographic screening in Brazil: data from the PROVAR (Rheumatic Valve Disease Screening Program) study. J Am Heart Assoc. 2018;7:e008039. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.117.008039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Gyekye‐Kusi A. Community health representative program: basic online training evaluation report. 2015:13. Available at: https://www.ihs.gov/sites/dper/themes/responsive2017/display_objects/documents/evaluation/CHR‐Program‐Online‐Training‐Evaluation.pdf Accessed February 21, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Sabo S, O'Meara L, Russell K, Hemstreet C, Nashio JT, Bender B, Hamilton J, Begay MG. Community health representative workforce: meeting the moment in American Indian health equity. Front Public Health. 2021;9:667926. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2021.667926 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data S1.

Figure S1.