Abstract

COVID-19 elicited a rapid emergence of new mutual aid networks in the US, but the practices of these networks are understudied. Using qualitative methods, we explored the empirical ethics guiding US-based mutual aid networks’ activities, and assessed the alignment between principles and practices as networks mobilized to meet community needs during 2020–21. We conducted in-depth interviews with 15 mutual aid group organizers and supplemented these with secondary source materials on mutual aid activities and participant observation of mutual aid organizing efforts. We analyzed participants’ practices in relation to key mutual aid principles as defined in the literature: 1) solidarity not charity; 2) non-hierarchical organizational structures; 3) equity in decision-making; and 4) political engagement. Our data also yielded a fifth principle, “mutuality,” essential to networks’ approaches but distinct from anarchist conceptions of mutualism. While mutual aid networks were heavily invested in these ethical principles, they struggled to achieve them in practice. These findings underscore the importance of mutual aid praxis as an intersection between ethical principles and practices, and the challenges that contemporary, and often new, mutual aid networks responding to COVID-19 face in developing praxis during a period of prolonged crisis. We develop a theory-of-change model that illuminates both the opportunities and the potential pitfalls of mutual aid work in the context of structural inequities, and shows how communities can achieve justice-oriented mutual aid praxis in current and future crises.

Keywords: mutual aid, COVID-19, solidarity, liberation, praxis, applied ethics, community organizing

1. INTRODUCTION

The COVID-19 pandemic exposed the inadequacies and inequities of frayed US formal social safety nets, as government and non-profits failed to fully meet basic needs for food, shelter, sanitation, safety, and health care—especially for marginalized populations. In response, mutual aid networks quickly formed or expanded to take on the responsibility of caring for their own members, responding to job losses, housing instability, food insecurity, and unmet medical needs in the absence of government support. These mutual aid networks established themselves through a variety of online platforms and mobilized grassroots efforts to support the basic needs of neighbors, friends, and fellow community members. Mutual aid organizations boomed around the world, including in India, Mexico, China, the United Kingdom, and the United States (Cornish and Gent 2020; Jun and Lance 2020; Littman et al. 2022; Mak and Fancourt 2020; Montesi 2020; O’Dweyer 2020; Parvez 2020; Béhague and Ortega 2021; Tolentino 2020; de Loggans 2021; Natural Hazards Center 2020).

The rapid uptake and expansion of mutual aid activities in communities during the early period of the COVID-19 pandemic in the US presented an opportunity to observe how mutual aid praxis was adapting and evolving during this crisis. While considerable scholarly attention has been attuned to the principles and political theories that undergird mutual aid, less research, particularly in the US, has focused on how mutual aid groups attempt to achieve these principles in practice (Bell 2021; Ferrari 2022; Kropotkin 1902; Littman et al. 2022; Mould et al. 2022; Spade 2020; Town Hall Hub 2020). Consequently, this study uses a framework of mutual aid praxis to examine the relations and frictions between mutual aid principles and practices. We draw on the concept of praxis from Freire (1972), who described it as a cyclical process of translating theories or principles into action and reflecting on those actions and theories to refine them toward justice. Our use of praxis as a way of analyzing mutual aid efforts emerges from the expertise and perspectives of mutual aid organizers themselves, who often invoke the term (and its theoretical underpinnings) as central to their efforts.

Mutual aid is not a new phenomenon: indeed, the term “mutual aid” was used by Peter Kropotkin in 1902 to describe “mutually-beneficial cooperation and reciprocity.” Subsequent research has contributed considerable evidence to support his idea that mutual aid is inherent to the human experience (Springer 2020; Brand and Wissen 2018; Kropotkin 1902). Scholars have more recently refuted claims by evolutionary biologists and anthropologists that human beings are wired for aggression, violence, and self-interest (Graeber and Wengrow 2021; Fuentes 2020; Rifkin 2009). Instead, they insist attachment, affection, and companionship are basic motivators, because humans want to belong, cooperate, and navigate life’s challenges together to create new community-oriented solutions. Thus, despite its newfound popularity, mutual aid has been an essential component of human existence and has been a named phenomenon in many cultures for far more than a hundred years.

Mutual aid also has roots in anarchist political theory (Kinna 1995; Proudhon 1989; Shantz 2001). Kropotkin himself was an anarchist, and a number of anarchist thinkers have developed the concepts of mutual aid and mutualism as a means of illustrating how anarchist politics can be put into practice (Kinna 1995; Kropotkin 1902). Proudhon (1989) was central to the development of an anarchist vision of mutual aid, and envisioned mutualism as a centerpiece of a “radically decentralized and pluralistic social order” where individuals and small groups, by forming collectives, possess capital and share credit (Ostergaard 1991, 400). Mutual aid within anarchist traditions is primarily aimed at creating opportunities for overturning government intrusion and achieving mutual liberation: Sakolsky (2012) notes that mutual aid is “concerned with providing the cooperative means for vaulting” what he calls the “wall of domination” (1).

More broadly, mutual aid has been a central component of political left-wing movements and efforts for survival, especially among BIPOC (Black, Indigenous, People of Color) communities, people with disabilities, the LGBTQ+ community, and migrants (Bahn, Cohen, and Meulen Rodgers 2020; Jun and Lance 2020; Loadenthal 2020; Nelson 2013). Political movements incorporating mutual aid have included the Black Panther Party, Fraternal and African American Mutual Aid Societies, Sociedades Mutualistas, the Young Lords Party, and United Farmworkers (Adereth 2020; Emmad and Peña 2020; Hinojosa 2020; Nelson 2013; Pycior 2020; Schupak 2020; Sherman 2020; Spade 2020; National Humanities Center 2007; Foundation Beyond Belief 2020; Wesley 1933; Orange County Congregation Community Organization [OCCCO] 2020). Mutual aid has been a phenomenon in previous pandemics and natural disasters, including the bubonic plague, the 1918 flu, and the HIV/AIDS pandemic; mutual aid organizers during COVID-19 built on the wisdom gained from these earlier efforts (Adereth 2020; Bonilla 2020; Foundation Beyond Belief 2020; García-López 2018; Garriga-López 2019; Lifelong 2020; Lisi 2020; Preston and Firth 2020; Rodríguez, Trainor, and Quarantelli 2006; Solnit 2010; Zaki 2020; Feuer 2012).

In the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic, new mutual aid networks emerged quickly to respond to community needs alongside older and more established movements, such as Mutual Aid Disaster Relief and disability justice mutual aid networks (Dunson 2022; Piepzna-Samarasinha 2018). But many networks were new, particularly in the US, catalyzed by government inaction, as well as the encouragement of high-profile activists and political figures. In mid-March 2020, Congresswoman Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez hosted a call with long-time mutual aid organizer and expert Mariame Kaba to educate the public about mutual aid approaches. Following the call, a Mutual Aid toolkit was widely shared online (#WeGotOurBlock 2020). Similarly, the US Town Hall Project began spreading the word about mutual aid networks and collating information on where they were emerging across the US (Town Hall Hub 2020). Activist experts on mutual aid, such as Dean Spade and Mariame Kaba, hosted numerous public conversations and education sessions. Later that year, Spade’s (2020) handbook Mutual Aid: Building Solidarity During This Crisis (and the Next) was published to wide acclaim. As Rhiannon Firth (2020) observed several months into the pandemic, “in the contemporary risk-addled and disaster-prone Zeitgeist, mutual aid groups are popping up at an innumerable rate” (67).

Spade, a Seattle-based trans educator, activist, and lawyer, has helped translate theories of mutual aid to a broad public audience. As he explains,

more and more ordinary people are feeling called to respond in their communities, creating bold and innovative ways to share resources and support vulnerable neighbors. This survival work, when done in conjunction with social movements demanding transformative change, is called mutual aid. (Spade 2020, 11)

Spade characterizes mutual aid as problem-solving or survival strategies rooted in collective action, including mobilizing people, expanding solidarity, and building movements. He specifically rejects the idea of “waiting for saviors,” instead promoting the principle of “solidarity not charity” by building collective political consciousness alongside providing community support (Spade 2020, 17–21). Others have (Chatzidakis et al. 2020) critiqued “the adoption of reactionary … models of ‘care’ by populist leaders such as Trump, Johnson, and Bolsonaro.” Indigenous writer Regan de Loggans (2021) differentiates mutual aid from these models by identifying it as explicitly anti-capitalist and rooted in BIPOC community organizing. “Capitalists cannot practise mutual aid,” de Loggans (2021) writes; “they can practise temporary reallocation (i.e., philanthropy) which is not the same as an anti-capitalist commitment to community thrivance.” These principles, such authors argue, must remain core to the conceptualization of mutual aid efforts across the United States and the world.

These are lofty—and radical—aims, but they are central to the conceptualization and history of mutual aid, and provide discrete praxis goals for organizers. As mutual aid has rapidly grown in popularity, “so too [have] the definitional boundaries of the term,” Mould et al. (2022, 3) note. Similarly, Firth (2020) observes of COVID-19 mutual aid networks,0

while some of these mutual aid groups arose from pre-existing anarchist networks, others arose from non-anarchist leftist movements or from institutionalised civil society … Some, but not all, use the term “mutual aid,” and not all who use this term are anarchist, and some are unaware that the concept originates in anarchist thought. (73)

In some cases, conceptual confusion has led to outright appropriation by charities and governments. Mould et al. (2022) propose that mutual aid now exists on a spectrum from charitable, to contributory, to ultimately radical practices—and that achieving more radical and mutualistic practices requires reconceptualizing what it means to be vulnerable in a time of near perpetual crisis.

Given the rapid uptake of mutual aid among people new to such efforts, this project sought to explore how mutual aid organizers and networks responding to COVID-19 conceptualized and put into practice the political and ethical principles of mutual aid. Drawing on in-depth interviews with mutual aid group organizers, we sought to understand the opportunities and challenges they faced in interpreting, enacting, and aspiring to these principles. Against the backdrop of the profoundly inequitable effects of the pandemic—often even within small geographic areas—we observed how groups and organizers engaged in mutual aid praxis in their efforts to address inequities and promote justice. This study does not purport to evaluate the effectiveness of mutual aid as an alternative to government-run systems of support, nor to develop or refine an overarching theory of mutual aid, but rather to examine the unfolding practice and underlying principles of mutual aid in response to COVID-19 to better understand the applied ethics of those practices in an ongoing public health crisis.

2. METHODS

We conducted in-depth interviews with mutual aid network participants about their networks’ formation, efforts, principles, and organizational experiences to understand how new networks (initiated during COVID-19) practiced mutual aid. To complement these data, we also collected secondary data on mutual aid networks across the US, and engaged in participant observation of mutual aid trainings, events, and gatherings. We sought to understand to what extent these networks endorsed key principles of mutual aid, how they mobilized these in practice, and the opportunities and challenges they faced in doing so.

We utilized snowball sampling via personal networks, social media, search engines, and the Town Hall Project’s Mutual Aid Hub Map to identify network participants for direct recruitment (Town Hall Hub 2020). We provided prospective study participants with an information sheet about the study. Our first nine participant networks over-represented white and coastal organizers, prompting us to selectively recruit participants from additional mutual aid networks in non-coastal regions with greater racial diversity to create a more representative sample. Our final sample included 15 participants, all 18 years or older, and all active participants in a mutual aid network founded between March 2020 and March 2021.

To develop the proposed framework and methods for this study, we conducted ten informal preliminary conversations with mutual aid organizers between March and August of 2020. In July 2020, we gained Institutional Review Board approval at the University of Washington for working with human subjects, and subsequently completed 15 semi-structured interviews with organizers across 12 geographically diverse networks, ending in March 2021. We conducted 45–60-minute interviews via Zoom. Participants chose whether interviews would be recorded (n = 14 agreed to recorded interviews), and how their data would be shared (n = 11 anonymously, n = 4 publicly). Participants who opted to be anonymous (n = 11) were given pseudonyms to ensure anonymity during the transcription and analysis process. For the purposes of consistency in this manuscript, all participant names remain anonymous. In addition, we identify mutual aid networks only by state (rather than city) to obscure identity.

We transcribed all interviews and then conducted an inductive thematic qualitative analysis using the software Dedoose. Initial analysis identified thematic codes related to organizational structures, challenges of work, types of activities, and mutual aid principles. Throughout the analysis we drafted analytic memos to keep track of how thematic areas changed and refined over the course of the interviews. We analyzed how well participants’ perspectives aligned with mutual aid principles based on previous conversations with mutual aid organizers as well as theory from Spade’s (2020) popular book on the subject. These inquiries yielded four main ethics that characterize mutual aid: 1) solidarity, not charity; 2) non-hierarchical organizational structure; 3) equity in decision-making; and 4) engagement in political action and education. These ethical principles were found to be prominent in the data; however, inductive analysis also led us to add the concept of “mutuality” to the existing principles, as this concept emerged as a central concern in conversations with participants. We use this term as distinct from anarchist theories of “mutualism,” and describe the reasons for this difference below. Notably, while Spade’s (2020) work briefly discusses mutuality as a leadership and collaboration skill, it does not identify mutuality as a key principle, nor does it speak to issues of mutuality in terms of exchange dynamics as mutual aid organizers predominantly discussed the concept.

To supplement qualitative findings, we developed categorical measures of organizational characteristics for further analysis. These variables included networks’ racial make-up, location, incorporation status, engagement in direct action and political education, and characteristics of the mutual aid network organizers. We used Excel to compute descriptive statistics for these variables.

Our team of researchers comprised white cis women not personally deeply involved in mutual aid networks. Because this limited our perspectives and contributed to potential power hierarchies with participants, we routinely engaged with mutual aid organizers and participants throughout the research process to shape the study, engage in dialogue about it, and receive feedback. We invited study participants to review this manuscript before submitting it for publication, and incorporated feedback into the manuscript.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Participants

We interviewed 15 participants representing 12 mutual aid networks from Alaska, Arkansas, California, Illinois, Maryland, New York, Texas, Washington, and Washington, D.C. Ten networks were in urban areas; two were in rural areas. As shown in Table 1, two organizers self-identified as BIPOC, and the remaining 13 organizers self-identified as white or white-passing. Thirteen of the mutual aid network organizers were women, two were men. Three of 12 (25%) networks represented in the interviews were led primarily by BIPOC individuals, while the remaining were primarily led by people who were white or white-passing.

TABLE 1.

CHARACTERISTICS OF 15 SUBJECTS INTERVIEWED FOR MUTUAL AID STUDY AND THEIR ASSOCIATED NETWORKS, 2020–21

| Characteristics of Mutual Aid Network Organizers (n = 15) | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Black, Indigenous, People of Color (BIPOC) | 2 (13.33) |

| Previous or current employment at a non-profit | 6 (40.00) |

| Characteristics of Mutual Aid Networks (n = 12) | |

| Self-described non-hierarchical organizational structure | 13 (86.67) |

| Plans/attempts to include historically marginalized populations in the decision-making process of the network | 4 (26.67) |

| Primary Racial Make-Up of Mutual Aid Network Organizing Body | |

| BIPOC | 3 (25.00) |

| Location of Mutual Aid Network | |

| Rural | 2 (16.67) |

| Mutual Aid Networks’ Incorporation Status | |

| Affiliated with 501(c)(3) | 3 (25.00) |

| Incorporated as 501(c)(4) | 1 (8.33) |

| The Degree to Which the Network Engages in Politics, Including Direct Action and Political Education | |

| Direct action | 8 (66.67) |

| Political education | 8 (66.67) |

3.2. Mutual Aid Networks’ Efforts

During COVID-19, mutual aid network participants reported providing groceries, personal protective equipment, emotional support, financial support, and creatively meeting other needs on request to a wide variety of community members. Networks coordinated the provision or receipt of aid via email (or other electronic message services), online forms, or through phone numbers or hotlines. Most mutual aid networks used a listserv or weekly/monthly newsletter, social media presence, and/or a website to deliver information and share requests for goods, services, or money. At times they also used their online presence to spread political education and opportunities for political action.

Digital tools were necessary, but not sufficient, to mutual aid networks’ work. In-person connection and organizing was often seen as essential, though disrupted by the pandemic. Online tools helped make work more organized and efficient, but much work still relied on human infrastructure and in-person distribution of resources. Organizers were also aware that reliance on digital tools raised questions of equity in access. While it allowed those with disabilities or health problems—as well as those who were geographically dispersed, such as networks in the Bay Area—to connect easily, organizers were aware that technologies could also be barriers for others. Some networks transitioned how they connected with people by holding weekly check-ins with network participants on the phone, using paper flyers and phone calls to reach out to participants, and hosting in-person “Community Days” (outside while wearing masks and physically distanced, for those who felt comfortable joining in). However, networks’ continued reliance on digital tools that required significant digital literacies for core components of their work reflected the professional class of many organizers. It also threatened to replicate the norms of non-profit and corporate management practices, and raised ethical issues of privacy and data ownership that organizers worried how to resolve.

As shown in Table 1, three networks were affiliated with 501(c)(3) organizations and one network was incorporated as a non-profit. Two-thirds of the networks studied engaged in direct action and/or political education with their members. These alignments and activities are discussed further below. As our focus was on how networks aim toward equity and justice in their work, we display our reporting of results in alignment with five key components of mutual aid practices and principles identified above: 1) solidarity, not charity; 2) mutuality; 3) non-hierarchical organizational structure; 4) equity in decision-making; and 5) engagement in political action and education.

3.3. Solidarity, not Charity

Like Spade (2020), our study’s mutual aid organizers all centered solidarity-building as an essential component of mutual aid work and described it primarily in opposition to charity practices. As a white woman network organizer in San Francisco explained, the work is

not from the perspective of giving charity, or from the perspective of the haves helping the have-nots, but rather building relationships with the community so that we are all caring about each other, regardless of what the need is.

Nearly all participants agreed with this concept and noted that a key difference between mutual aid and charity is that mutual aid requires building solidarity within networks and the community. However, language such as “building relationships with the community” reveals how mutual aid organizers (perhaps unconsciously) viewed themselves as separate from communities with which they were trying to build solidarity.

Those who described the difference between charity and mutual aid noted that the “intention” behind providing support matters most. As a white woman organizer from Maryland noted,

The first is that, you know, really breaking down those barriers between, like, a donor and a receiver … It’s not charitable giving. It’s just everyone taking care of each other and building community. I think charity really creates division. And mutual aid is all about removing that division and creating community.

A white male organizer from Arkansas said that moving away from charitable practices required departing from the capitalistic mindsets that undergird them. “We see mutual aid as this parallel economy to the current capitalist economy rather than just as a fix or a, you know, just to try to patch what doesn’t work with capitalism.” He explained that in practice this often looked like a lot of educational work and engagement for “unlearning internalized capitalism.” For example:

in our groups we’ll have people come on and be, like, “I hate that I have to ask,” and it’s like, “no, don’t, don’t say that” … “we’re all here to help one another and, don’t be ashamed.” Like, “it’s okay, you know your current need [isn’t] any sort of sign of your value or your worth.” So, we always emphasize that. And so, when people come in to post … in our group that they need something usually one of us will jump in and say, “you know, I hate that our current economic system has put you in this position.”

This organizer went furthest in describing how his network differentiated their work from charity compared with others we interviewed. Many others struggled to further articulate how they and their networks created practices that ensured mutual aid was distinct from charity, even as they recognized this as a central tenant of mutual aid.

Organizers were aware of the importance of adhering to physical distancing guidance to prevent the spread of COVID-19, but found social separation created a challenge in connecting and building relationships, a key first step to building solidarity. A white woman network organizer in Washington State explained that she had to drop off supplies, knock on the door, and walk away so “no one is exposed to SARS-CoV-2.” She would exchange “hello’s” and “how are you’s,” but “that’s about it,” and noted that social distancing guidelines, particularly during the early months of the pandemic, “[limited] the ability to build relationships.”

While organizers were not explicit in naming the practice, it seemed clear that none of the mutual aid organizations we spoke with were using screening tools to determine the “deservingness” or eligibility of individuals to participate in the network. By contrast, in typical charity programs, paid staff are employed to ensure those on the receiving end of aid are sufficiently in need (deserving), and often impose further criteria that reinforces capitalist conceptions of deservingness, such as requiring recipients to show evidence of “hard work” or “productivity” (INCITE! 2017).

3.4. “Mutuality” of Mutual Aid

Many interviewees emphasized the importance of mutuality as a key principle of mutual aid. Organizers defined this as the idea that everyone has something to give as well as needs to be met, and emphasized a mutuality of giving as core to solidarity-building work. Organizers worried that persistent patterns of one group giving to another could create hierarchical social dynamics that would replicate other forms of charity and undermine efforts at building solidarity. In practice, however, organizers acknowledged one-way aid patterns were a persistent phenomenon among their mutual aid groups, and difficult to escape, particularly given the socio-economic gaps between those who had more capacity to give and those making requests in local networks.

Many network organizers decried what they saw as a “division within mutual aid … between people who provide things … and people who receive things,” because it is “of course against the entire point.” A white woman organizer in Texas articulated the damage this divide creates, saying

it can be very disempowering to just, um, be the recipient of aid all the time, and it sends the message … you know, it essentially sends the message, “I’m needy, I’m on the receiving end, I don’t have anything to give, I’m the unlucky one,” and I think that’s dangerous and powerfully toxic to everyone.

Some network organizers pointed to wealth inequities as inhibiting the possibilities for mutuality. A white woman organizer in Alaska noted, “we’ve found that the people that are asking [for support], they just don’t have the capacity to feel like they can give anything.” Network organizers reported they actively discussed these challenges within their networks, and some reported they changed their organizational structures to elicit more mutuality.

Three network organizers said the first step they took to encourage a truly mutual exchange within network participants was to reframe what it means to give and receive beyond material goods. For example, two organizers said they encouraged participants to consider the value of exchanging knowledge of how to navigate federal or state resources or providing social support and advice. Participants provided three examples of ways in which they restructured their network to encourage true mutuality and exchange:

Within each interaction of “giving,” the individual was asked if there is any support they would like to “receive” and vice versa;

Each person who signs up to participate in the network online was asked to fill out both what they can give and the support they need. Then, network organizers matched people based upon “needs” and “gives”;

Network participants were encouraged to provide skill-shares or teachins. Network organizers said skill-sharing included graphic design, bike care, art therapy, protection/self-defense during protests, and de-escalation training.

Organizers noted skills-sharing acts of giving still required resources of time and space that may have been particularly limited for low-income and frontline worker populations who were facing care burdens. It is notable that these alternatives were still premised on a politics of equal exchange, rather than a politics rooted in equity, where people’s needs are met without expectations of reciprocity. While some organizers said they aimed for greater practices of equity and anti-capitalist work, they were a minority (and primarily from BIPOC- and women-led organizations).

Concerns with mutuality as described by organizers contrasted with anarchist theories of mutualism, which more directly aim to subvert capitalist and government structures. For the most part, they did not recognize, or articulate, mutualism as connected to anarchist thought. Most applied a “big tent” approach to organizing:

some of us believe in anarchy and you know are against the government at all. Some of us are socialists, um the thing about mutual aid is that it’s not hierarchical and so there’s no one telling us what to believe. We believe in different things just like we believe in different religions, but we all believe in doing this work.

Only two organizers self-identified as anarchist or articulated anarchist political goals as an outcome of mutual aid. While others articulated the need to be self-organized, decentralized, and mutually accountable to each other, their work was often described as a necessary adaptation to late capitalist economic and social systems, rather than a means of overturning these systems and radically replacing them.

3.5. Non-Hierarchical Organizational Structures

Organizational structures frame how power and responsibility are organized within a group. Within US business culture, employees are usually organized hierarchically, while mutual aid and other left-leaning politically oriented groups are typically more “flat” or egalitarian in their structures (Spade 2020). Ideally, flat organizational structures decentralize power; therefore, oppression is less ingrained in the structure of the organization. We asked mutual aid groups about both their formal power arrangements (through organization charts and incorporation, for example) and their informal relationships.

A large majority of organizers (n = 13, 87%) described their network as non-hierarchical, where roles are task-oriented with no formal leadership titles. One Black woman network organizer in Illinois described her organization’s structure as spokes on a wheel and referred to their network organizers as “spokespeople.” She explained, “we have an outreach spokesperson … [a] mental health spokesperson … and a general spokesperson who runs the meetings.”

Many network organizers said their hierarchical structure was “as flat as possible,” but elsewhere in the interview described people within their organization as network leaders in practice if not in name. A white woman network organizer in Maryland explained, “I would say ‘Ida’ is really like the leader, even though it’s non-hierarchical.” Network founders were most likely to be identified as leaders, and some founders acknowledged that tension: as one participant from Arkansas put it,

my role is a white cis heterosexual man. I’m typically the one who’s doing the dominating and leading and so I’m trying to encourage leadership among other people. But I don’t think people are used to that. And so, getting in the vibe of shared leadership, I think, has been a big challenge.

One major organizational issue facing mutual aid networks is the choice of becoming incorporated or becoming officially recognized by the US government. Most organizers opposed becoming incorporated for two reasons: first, they viewed mutual aid as inherently non-governmental and believed working with the government to any degree went against their core values; second, not being incorporated distinguished networks from charities, emphasizing the grassroots nature of their identities. However, in practice, mutual aid groups struggled with unlearning and interrupting non-profit model dynamics. In fact, 40% of network organizers we interviewed were currently employed or previously employed by non-profit organizations. This was evident in participants’ language, peppered with terms like “donor,” “fundraising,” and “volunteer.”

Incorporation can provide a useful financial and legal infrastructure for mutual aid networks, so many groups wrestled with the incorporation decision. Twenty-five percent (n = 3) of the networks in this study were directly affiliated with a non-profit for purposes of financial reporting accountability. Most organizers whose networks were fiscally sponsored by a non-profit organization explained they valued the legal protections, as they were receiving and distributing tens of thousands of dollars. One network decided to become incorporated (as a 501(c)(4)), but our interviewee, a white male organizer from Arkansas, looked back on this decision with regret because, after learning, reading, and reflecting more about mutual aid, he came to believe being incorporated (even as an advocacy non-profit) went “against the philosophy of mutual aid.”

3.6. Equity in Decision-Making

Another key principle that organizers identified in their work was equity in decision-making processes. Organizers used this to differentiate their work from charitable and non-profit organizations, which were described as places where decisions are typically made by financially comfortable and otherwise privileged people who may not be directly experiencing the inequities they are addressing (Ojeda and Wall 2021; INCITE! 2017). By contrast, mutual aid was recognized as organizing itself around equity while working toward mutual liberation.

While network organizers often focused on how to center people experiencing intersecting inequities within their own network decision-making processes, they also conceded that decisions were primarily made by core network organizers. Only 27% of participants in the networks reported plans or attempts to include historically excluded populations in decision-making processes. One reflected that decision-making was “kind of in a closed box which none of us are honestly comfortable with” (white/white-passing woman, Maryland). When asked about equity concerns, organizers most often focused on racial equity in representation. Despite this attention, less than 10% of networks with primarily white/white-passing organizers said they were making efforts to include historically marginalized populations in the decision-making process. Organizers in primarily white/white-passing networks noted the racial make-up of the network did not sit well with them. A white woman participant from California commented,

I would like the group to be led by someone other than me. I would like the decision-makers to be people of color and non-cis gendered. It is important for non-white people to be leading organizations like this. That said, I’m not going to ask anybody to do free work.

By contrast, within the two organizations primarily led by BIPOC, both planned or attempted to include historically marginalized populations in the decision-making process. One Black woman organizer from DC explained:

Our org does really well by letting Black women lead. To be very honest, I feel like Black women speak up and come up with ideas and want to make changes … it’s obviously important because we know that unfortunately Black women are severely marginalized in a lot of areas, so we don’t want that power to be unbalanced … the power should be with the community that it resembles.

Organizers in primarily white-led networks acknowledged that there had been instances where they harmed fellow BIPOC organizers with their internalized white supremacy. For example, a participant from Texas said she

made a member of our team feel like her identity was not being seen … by emphasizing how much growth I wanted us to do in engaging people of color, specifically the Black community and the Hispanic community … I managed to invalidate the diversity that was [already] there.

Participants highlighted incidents like these as reasons for BIPOC members leaving networks.

Networks also struggled with language and technological inequities. About half of the participants noted they reached out only to people who spoke English and Spanish, despite additional languages spoken in their area, while the other half reached out only to people who spoke English. For all networks, decision-making during meetings took place entirely in English. One participant explained, “we’ve had so many conversations about, ‘how do we host a town hall in multiple languages without it being a complete disaster?’” (white/white-passing woman, Maryland). Additionally, uneven access to technological resources exacerbated inequities at a time when networks were particularly reliant on remote connections for their work. Participants expressed concerns about differential access to technology as a barrier for those reaching out for support, but not necessarily for those in decision-making roles.

In our interviews, organizers envisioned, but had not yet implemented, strategies for more equitable decision-making. One network suggested using bi/multilingual facilitators to get input from all participants in the organization within each interaction. Other networks discussed wanting to decentralize decision-making from “organizers” to all people who interacted with their organizations through town halls, newsletters, and outreach events. Another organization suggested its group hold meetings in multiple languages, not just during outreach days or on helplines, but in all gatherings.

3.7. Political Action and Education

Political action and education were identified as key principles of mutual aid, as these efforts provide an opportunity to reflect on and change the conditions that create inequities and to work toward mutual liberation. Eight of fifteen participants (67%) said their networks engaged in political action and education, and networks had varying views on the degree to which mutual aid should be political. The majority of interviewees noted mutual aid at its core is inherently political. One network organizer described “[baking] our [political] analysis into everything that we do” (white/white-passing woman, Washington). Two mutual aid networks, however, noted they were apolitical.

Another network reported that, as members learned more about the tenets of mutual aid, their network shifted from being apolitical to overtly political. Located in conservative Arkansas, this organization nonetheless chose to camouflage its politics to avoid pushing people away. The (white male) organizer said they don’t want to be perceived as “a bunch of communists,” so they “ease” people into conversations and educate people about concepts from anarchism and socialism without the “scary labels.” Other organizers explained that most of their network participants could be classified as anarchists, socialists, or communists. However, one organizer noted,

I think, I never asked people their parties, but I think we could have had, you know, some Republicans as leaders and some of the places that we were doing this work, we definitely (also) had more conservative people. (white/white-passing woman, New York)

Networks that engaged in political education tended to share written materials on root causes of inequities, the principles of mutual aid, mutual aid movements throughout history, current events, and/or instances of mutual aid. Some mutual aid networks held book clubs on abolition and justice and had regular discussions about mutual aid, anti-capitalism, and anti-racism. When asked about their approach and why political engagement is important, a participant described the goal of her mutual aid work was to provide more tools and knowledge for people “to empower themselves” (Black woman, Illinois).

Mutual aid networks shared opportunities for political action through newsletters, weekly emails, and social media. This boosted attendance at Black Lives Matter protests, rent strikes, and pickets at elected officials’ homes and offices. It also resulted in mutual aid network participants joining larger political movements to which they may not have otherwise been exposed. A California network engaged in the 2020 general election process by holding events to discuss ballot measures and hand-delivering ballots. Networks in this sample also prioritized the problem of housing injustice. Several networks directly intervened in evictions and encampment sweeps, provided legal support for wrongfully evicted residents, and supported legislation developed by tenant’s rights unions to expand renters’ rights.

4. DISCUSSION

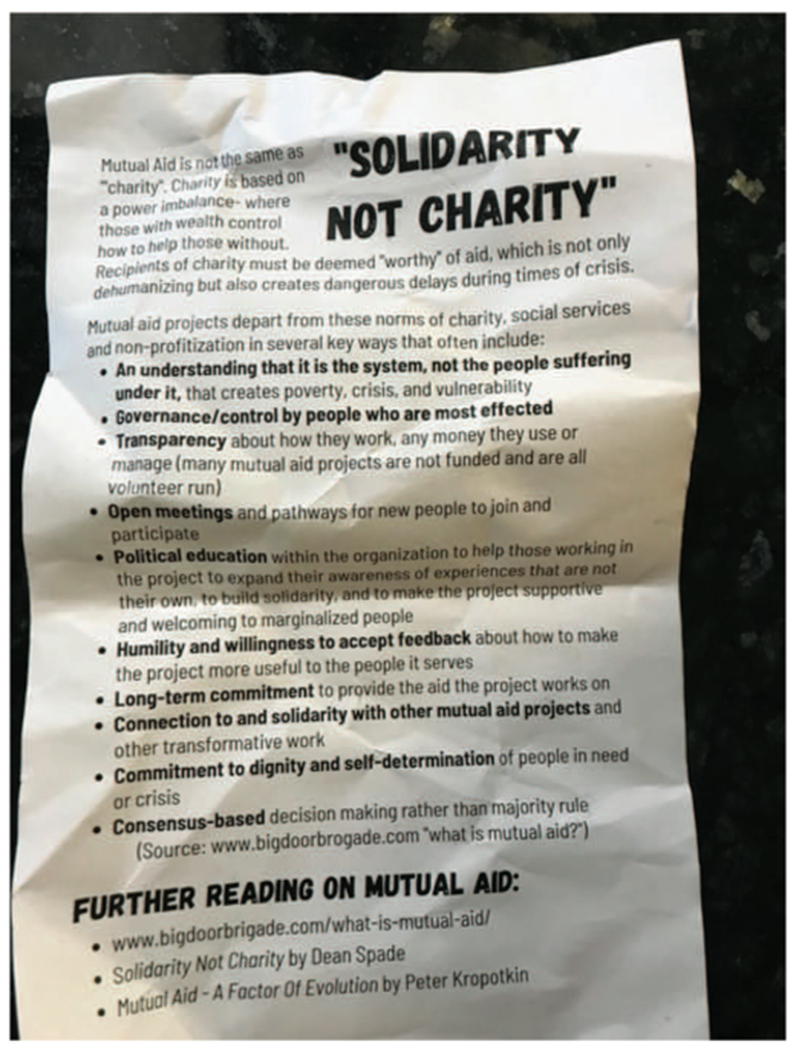

Mutual aid organizers in the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic mobilized their communities to support one another in settings where government or charitable services were insufficient or were offered in a way that undermined the agency and dignity of aid recipients. The organizers we spoke with were fully cognizant of the principles underpinning collective action, and worked to ensure broad support for these values, contrasting them with harmful features of charitable giving. However, mobilizing these principles in practice proved complex and challenging, particularly in the context of pernicious and worsening inequities during the pandemic. Mutual aid groups might benefit from more collective work to align principles with practices in an ongoing manner through critical mutual aid praxis, especially as their work continues in the context of a prolonged pandemic and ongoing retrenchment of social support in the US. Within the literature, and among organizers, there is strong cohesion and agreement regarding core principles of mutual aid: solidarity not charity, decentralized organizational structures, equity in decision-making, and political action and education (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Telephone Pole Flyer in Seattle, Circa 2020. Photo by Amy Hagopian.

However, our research shows that mutual aid groups and organizers struggled to develop mutual aid practices that always aligned with these values, in large part because of structural constraints they faced in their work. For example, the phrase “solidarity not charity” was commonly invoked to describe mutual aid efforts (Spade 2020). Within our sample, while many respondents described the importance of solidarity as an intention, most struggled to describe how they were implementing it. While mutual aid networks aimed to differentiate their work from that of non-profits and charities, many were not able to explain how the core functions of their efforts were substantively different from those involved in charity. As the intention of mutual aid is to divest from the non-profit industrial complex to meet the real needs of people and work toward mutual liberation, this is concerning.

This project uncovers a critical new dimension of mutual aid praxis—mutuality—that is a particular point of friction for many groups. Although the concept of mutualism is central to anarchist approaches to mutual aid, organizers described a different set of concerns related to reciprocity that have not been adequately described or unpacked in the existing literature. As Mould (2021) has recently argued, mutualism—“a radical connectivity with each other as mutuals” (35)—is a key ethic of a post-capitalist or anti-capitalist society, and it is certainly a cornerstone of mutual aid praxis. Only a small minority of participants made connections between their mutual aid work and explicitly anarchist goals; while many spoke about working toward political change, such efforts often took a backseat to more pragmatic challenges of distributing resources to meet immediate needs. It’s not surprising that in this context mutuality takes precedent over mutualism.

In discussing mutuality, participants in this study pointed to something more specific about how resources of all kinds are shared and exchanged, and in direct opposition to the giver–receiver dynamics of traditional charity. The absence of consensus about how mutuality should be realized in practice was a frequent struggle for organizers in our study, who recognized its importance but had difficulties defining or operationalizing it. While some groups emphasized reciprocity, many struggled to identify how reciprocity (of both material and non-material resources) could be enacted and encouraged, especially given the extraordinary inequities in resources of all types exacerbated by the pandemic. Some emerging literature on mutual aid describes practices of “aid-giving,” “charity,” “contributions,” and “volunteerism” as common; however, organizers in this study were very clear that mutual aid should not be defined through these largely unidirectional activities (Mould et al. 2022; Wakefield, Bowe, and Kellezi 2022). Defining, operationalizing, and strategizing what mutuality can look like in the context of steep social and economic inequities, systematic marginalization, and prolonged crisis is a key hurdle for mutual aid.

Similarly, given that the pandemic coincided with the eruption of protests against police violence aimed at BIPOC communities, mutual aid organizations we spoke with were acutely conscious of injustices in the decision-making processes for community care (Morris 2000; Sullivan and Tifft 2008; brown and Cyril 2020). However, more than 90% of the organizations led by white organizers in our sample did not report creating mechanisms to intentionally include historically marginalized populations in their decision-making processes. Mutual aid groups appeared to struggle with some of the same challenges of racially equitable leadership that are seen in the non-profit sector (Kastelle 2013). Marginalized people face significant barriers to leadership, including time, resources, and capacity to take on leadership positions. Many of these barriers were exacerbated by a pandemic that disproportionately harmed already marginalized communities. Historical or contemporary exclusions create momentum, and white organizers reported a reluctance to invite BIPOC organizers to spend the time required to take on leadership responsibilities.

Mutual aid networks in this study also struggled to put principles into practice in their organizational structures and activities. Research shows decentralized organizational structures are adept at responding to crises (Hughes et al. 2021). Additionally, mutual aid theorists claim mutual aid networks provide advantages over other kinds of crisis-response actors by “[abstaining] from power dynamics, hierarchical structures and gatekeeping” (Parker 2020). While the networks we studied claimed to be organized in flat structures, many also identified social hierarchies that seeped into their work. Networks that actively worked to interrupt these dynamics reported they were successful in doing so, but the majority of organizers acknowledged leadership hierarchies.

Many of the organizers within our sample were not affiliated with governmental organizations and some even said they would not work with governments, noting that institutional abandonment was why networks were needed (Cutuli 2021). As many mutual aid scholars note, mutual aid does not need to be legitimized by a government to be valuable, and in fact, Spade highlights the government’s historic and current role in interrupting, coopting, and harming grassroots movements (Spade 2020; INCITE! 2017; Spence 2021). Grassroots mutual aid organizations can be useful in mobilizing quickly to advance policy change because of their local knowledge, informal nature, and adaptability, especially compared to government or large bureaucratic organizations (Carstensen, Mudhar, and Munksgaard 2021; Chevee 2022). Therefore, mutual aid networks have the potential to be powerful agents of change, specifically by combining community support with political mobilization. Unfortunately, nearly half the groups in this study were not engaging in political action or education because they were afraid of losing members, shied away from difficult conversations, or were overburdened and struggling to stay afloat, which sidelined political work. Since mutual aid often achieves its broader goals through political action, networks responding to short-term COVID-19 needs may have missed crucial opportunities to engage in upstream political mobilization (Spade 2020).

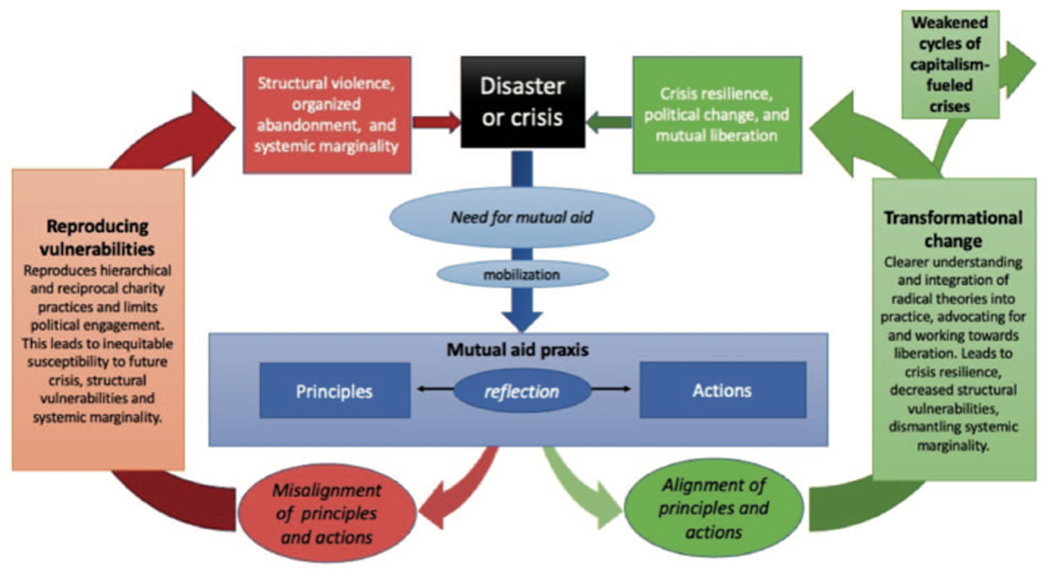

To address these challenges, and based on data gathered from participants, we developed a theory-of-change model for mutual aid organizing during a crisis like the pandemic. A theory of change articulates “the central processes or drivers by which change comes about for individuals, groups or communities” (Funnel and Rogers 2011, xix). In this case, our model shows how focusing on aligning practices with principles in mutual aid work leads to a mutual aid praxis that allows for mutual liberation and transformation. To our knowledge, this is the first theory of change published that focuses on mutual aid networks.

Our theory of change acknowledges the precipitating role of a disaster or crisis—combined with governmental and economic failures that produce structural violence, organized abandonment, and systematic marginality—in prompting grassroots networks to mobilize collective care through mutual aid. Drawing on the work of Paolo Freire (1972) as well as insights gained from discussions with mutual aid organizers, we identify mutual aid praxis as an interchange between principles and actions, and continual reflection on both. Based on the results of this study, a common challenge in contemporary mutual aid praxis is achieving alignment between principles and actions. When principles and actions are misaligned, there is a danger for hierarchical, apolitical, and reciprocal charity practices to reproduce vulnerabilities and inequitable susceptibility to future crises. As this model shows, such a process can contribute to further harms among marginalized communities from future crises, as well as more need for mutual aid intervention, potentially leading to burnout among networks, particularly during prolonged crises like COVID-19. Conversely, if the principles and actions of mutual aid are aligned with one another through constant reflection and praxis, there is a strong possibility for more transformational change, contributing to liberation and dismantling of capitalist power arrangements. In the face of nearly inevitable future crises, such transformational change creates the possibilities for crisis resilience and adaptation, as well as political advocacy to decrease the likelihood, severity, and threat of such crises. Ultimately, such transformative change dampens the acute needs to which mutual aid networks must respond, and equips them with greater resources to further pursue structural and political change.

Understanding and identifying the degree to which mutual aid principles and actions are aligned within a mutual aid network is a key first step to transformational change and liberation. Organizers were typically aware of the ideological origins of mutual aid principles and were conscious of the philosophy of Dean Spade (2020) and like-minded theorists, though less aware of mutual aid’s roots in anarchist theory. They were self-conscious about the importance of fidelity to key mutual aid principles, but struggled to implement them in practice, particularly under the economic and social constraints imposed by the pandemic. We encourage activists and scholars to engage mutual aid networks in creative strategies for better aligning principles and practices. Manuals like Spade’s (2020) provide some practical advice on how to overcome dilemmas commonly faced by networks. To generate creative solutions aimed at more transformational change, mutual aid organizers may want to intentionally schedule critical, open-ended reflection in the tradition of Freire (1972).

The prolonged acuity of the pandemic, combined with the naïve engagement of mutual aid participants new to this work, challenged the capacity of organizers to engage in political reflection and action. But without attention to these broader goals, mutual aid loses its ability to enact long-term change and achieve its mission. Participants’ preoccupation with mutuality instead of broader goals of mutualism indicates ways that attending to immediate (and often overwhelming) needs may limit networks’ capacity for political work, and also demonstrates the struggles networks faced in challenging capitalist frameworks of charity, reciprocity, and deservingness. It may also be reflective of sometimes depoliticized ways that mutual aid was introduced to Americans at the beginning of the pandemic. For example, a popular guide to mutual aid put out by the mutual aid crowdfunding platform Ioby explained, “Remember that mutual aid is mutual. So don’t forget to ask yourself—what kind of support would I like?” (Lumbantobing 2020, emphasis in original). Such explanations, particularly in the absence of explicit discussions about the political goals of mutual aid, reinforce what we have described above as a cycle of reproduced vulnerabilities. Indeed, as Rhiannon Firth (2020) cautions,

we have seen a growing trend for the state to rely on spontaneous community responses to compensate for its growing incapacity and indifference … state-centred discourse tends to treat people cooperating for mutual aid as a convenient source of energy to marshal temporarily for community relief action, in the interests of returning to the more ‘normal’ state of competitive individualism and the functioning circulation of capital. (64)

4.1. Limitations

Given the challenges of studying a rapidly unfolding social phenomenon during a pandemic, this study does have several limitations. First, there is limited diversity in the sample of participants in terms of race and gender, despite targeted snowball sampling methods and extensive time spent reaching out to diverse networks. This may in part reflect the positionality of the researchers, as well as negative perceptions of white-led research among historically marginalized communities. Therefore, our results may not reflect the full range of experiences or expertise of US mutual aid networks or participants. Time and the limitations of largely online research may have constrained opportunities to build trust. We also do not have good data on the demographic make-up of mutual aid networks to use as a sampling frame; it is possible ours is a representative sample, and other observers of COVID-19 mutual aid have noted its heavily white demographics (O’Dweyer 2020). In addition, our subject interview sample size is small, with only 15 participants. Further research would expand and deepen our understanding of mutual aid practices during the pandemic.

5. CONCLUSION

Mutual aid in its idealized form is an effort to avoid exacerbating the inequities of disaster, but also to lay the groundwork to create new political and social orders where crises are less likely and less harmful. This study shows that mutual aid networks during the early part of the US COVID-19 pandemic were striving to implement transformative, non-hierarchical, and mutual systems of support, but struggling to align the principles of mutual aid with their everyday practices. Participants reported a central, previously under-observed, and challenging finding—struggling to operationalize and practice the concept of mutuality while paying limited, if any, attention to the anarchist principles of mutualism central to mutual aid’s theoretical and political underpinnings. Given the rapid mobilization of new mutual aid groups as the pandemic emerged, and the additional constraints these networks faced during a highly inequitable crisis and inept government response, it is not surprising groups faced these dilemmas. Our findings point to the central importance of mutual aid praxis—and, in particular, the alignment between principles and actions—as a key dimension of mutual aid networks’ ability to achieve transformational and sustainable change, particularly in the context of acute crises. Our research highlights the need for more creative strategizing among organizers, scholars, and advocates to identify how to operationalize and implement principles like mutualism, especially as inequities and vulnerabilities continue to be exacerbated by crisis.

In addition to engaging in ongoing practices of self-reflection and accountability, newly initiated networks could pursue other opportunities to support their growth in aligning mutual aid principles and practices. For example, peer networks could work to connect and share successes, struggles, and solutions to expand their capacities and resilience. Better record keeping of, and research on, mutual aid experiences during COVID-19 would also expand networks’ knowledge. Researchers and advocates can also facilitate learning from mutual aid strategies that pre-date the COVID-19 era, including by conducting literature reviews and oral histories, and providing connections between new and old networks. Additionally, networks that existed prior to the pandemic can learn from newly initiated networks that survived and organized during a radical shift in attitudes toward police power and the Black Lives Matter movement, in the wake of the police murder of George Floyd in Minneapolis, and the compounding struggles of a pandemic intensified by the necropolitical policies of former President Trump (Vansynghel 2020). These acute struggles have further highlighted the urgency of addressing racial, economic, and health equity within mutual aid networks. Recording and archiving the lived legacy of these networks’ experiences amplifies the lessons to inform current and future mutual aid efforts. This research has been carried out in that spirit, with the intention of contributing to the realization of mutual liberation rather than simply documenting or critiquing networks’ efforts.

Figure 2.

Theory of change for mutual aid during COVID-19, showing how alignment between principles and actions in mutual aid praxis can fuel transformational change, and how misalignment reproduces vulnerabilities

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are particularly grateful to the mutual aid organizers who offered their time, expertise, and insights throughout this research process. Our work on this manuscript benefited greatly from excellent feedback from two anonymous reviewers, as well as attendees of the 2021 APHA Spirit of 1848 conference session, and the University of Washington’s Community Oriented Public Health Practice MPH students from the 2021 cohort.

REFERENCES

- Adereth Maya. 2020. “The United States Has a Long History of Mutual Aid Organizing.” Jacobin, June 14. https://jacobin.com/2020/06/mutual-aid-united-states-unions. [Google Scholar]

- Bahn Kate, Cohen Jennifer, and Rodgers Yana Meulen. 2020. “A Feminist Perspective on COVID-19 and the Value of Care Work Globally.” Gender, Work & Organization 27 (5): 695–99. 10.1111/gwao.12459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell Finn McLafferty. 2021. “Amplified Injustices and Mutual Aid in the COVID-19 Pandemic.” Qualitative Social Work 20 (1–2): 410–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonilla Yarimar. 2020. “The Coloniality of Disaster: Race, Empire, and the Temporal Logics of Emergency in Puerto Rico, USA.” Political Geography 78: 102181. 10.1016/j.polgeo.2020.102181. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brand Ulrich, and Wissen Markus. 2018. The Limits to Capitalist Nature: Theorizing and Overcoming the Imperial Mode of Living. London: Rowman & Littlefield International Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- brown adrienne maree, and Malkia Cyril. 2020. We Will Not Cancel Us: And Other Dreams of Transformative Justice. Chico, CA: AK Press. [Google Scholar]

- Béhague Dominique, and Ortega Francisco. 2021. “Mutual Aid, Pandemic Politics, and Global Social Medicine in Brazil.” The Lancet 398 (10300): 575–76. 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)01002-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carstensen Nils, Mudhar Mandeep, and Freja Schurmann Munksgaard. 2021. “‘Let Communities Do Their Work’: The Role of Mutual Aid and Self-Help Groups in the COVID-19 Pandemic Response.” Disasters 45: S146–73. 10.1111/disa.12515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chatzidakis Andreas, Hakim Jamie, Littler Jo, Rottenberg Catherine, and Segal Lynne. 2020. “From Carewashing to Radical Care: The Discursive Explosions of Care During COVID-19. Feminist Media Studies 20(6): 889–95. [Google Scholar]

- Chevée Adélie. 2022. “Mutual Aid in North London During the COVID-19 Pandemic.” Social Movement Studies 21 (4): 413–19. 10.1080/14742837.2021.1890574. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cornish Ed, and Gent Peony. 2020. “Covid-19 Mutual Aid UK.” Accessed November 24, 2020. https://covidmutualaid.org/. [Google Scholar]

- Cutuli Allison M. 2021. “Risk, Trust and Emergent Groups: COVID-19 Mutual Aid Networks.” University of Montana: Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, and Professional Papers, https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/11808. [Google Scholar]

- de Loggans Regan. 2021. “The Co-Option of Mutual Aid.” Briarpatch 50 (4):30–3. [Google Scholar]

- Dunson Jimmy. 2022. Building Power While the Lights Are Out: Disasters, Mutual Aid, and Dual Power. Tampa, FL: Rebel Hearts Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Emmad Fatuma, and Peña Devon G.. 2020. “Feeding our Autonomy: Resilience in the Face of the CoVid-19 and Future Pandemics.” Agriculture and Human Values 37 (3): 565–66. 10.1007/s10460-020-10074-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrari E. 2022. “Latency and Crisis: Mutual Aid Activism in the Covid-19 Pandemic.” Qualitative Sociology 45 (3): 413–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feuer Alan. 2012. “Where FEMA Fell Short, Occupy Sandy Was There.” New York Times, November 11. https://www.nytimes.com/2012/11/11/nyregion/where-fema-fell-short-occupy-sandy-was-there.html. [Google Scholar]

- Firth Rhiannon. 2020. “Mutual Aid, Anarchist Preparedness and COVID-19.” In Coronavirus, Class and Mutual Aid in the United Kingdom, edited by John Preston, 57–111. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Foundation Beyond Belief. 2020. “The Radical Past and Present of Mutual Aid.” Go Humanity. https://gohumanity.world/the-radical-past-and-present-of-mutual-aid/ [Google Scholar]

- Freire Paulo. 1972. Pedagogy of the Oppressed. London: Penguin Books. [Google Scholar]

- Fuentes Agustín. 2020. “A (Bio)Anthropological View of the COVID-19 Era Midstream: Beyond the Infection.” Anthropology Now 12 (1): 24–32. 10.1080/19428200.2020.1760635. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Funnell Sue C., and Rogers Patricia J.. 2011. Purposeful Program Theory: Effective Use of Theories of Change and Logic Models. New York: Jossey-Bass. [Google Scholar]

- García-López Gustavo A. 2018. “The Multiple Layers of Environmental Injustice in Contexts of (Un)natural Disasters: The Case of Puerto Rico Post-Hurricane Maria.” Environmental Justice 11 (3): 101–08. 10.1089/env.2017.0045. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Garriga-López Adriana. 2019. “Puerto Rico: The Future in Question.” Shima 13 (2): 174–92. 10.21463/shima.13.2.13. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Graeber David, and Wengrow David. 2021. The Dawn of Everything: A New History of Humanity. London: Allen Lane. [Google Scholar]

- Hinojosa Mwende. 2020. “History of Mutual Aid Coops. ” Sustainable Economies Law Center, August 7. https://www.theselc.org/history_of_mutual_aid_coops. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes Tim, Adams Lizzie, Obijiaku Charlotte, and Smith Graham. 2021. Democracy in a Pandemic: Participation in Response to Crisis. London: University of Westminster Press. [Google Scholar]

- INCITE! 2017. The Revolution Will Not Be Funded: Beyond the Non-Profit Industrial Complex. Durham, NC: Duke University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Jun Nathan, and Lance Mark. 2020. “Anarchist Responses to a Pandemic: The Covid-19 Crisis as a Case Study in Mutual Aid.” Kennedy Institute of Ethics 30 (3): 361–78. [Google Scholar]

- Kastelle Tim. 2013. “Hierarchy is Overrated.” Harvard Business Review Blogs, November 20. https://hbr.org/2013/11/hierarchy-is-overrated. [Google Scholar]

- Kinna Ruth. 1995. “Kropotkin’s Theory of Mutual Aid in Historical Context.” International Review of Social History 40 (2): 259–83. [Google Scholar]

- Kropotkin Petr. 1902. Mutual Aid: A Factor of Evolution. The Anarchist Library.https://theanarchistlibrary.org/library/petr-kropotkin-mutual-aid-a-factor-of-evolution. [Google Scholar]

- Lifelong. 2020. “Forged In Crisis.” Lifelong. Accessed November 24, 2020. https://www.lifelong.org/history. [Google Scholar]

- Lisi Tom. 2020. “Understanding the 1918 Spanish Flu Outbreak Could Help Us Deal with COVID-19.” Pittsburgh Current. Accessed November 24, 2020. https://www.pittsburghcurrent.com/1918-spanish-flu-covid-19/. [Google Scholar]

- Littman Danielle M., Boyett Madi, Bender Kimberly, Annie Zean Dunbar Marisa Santarella, Trish Becker-Hafnor Kate Saavedra, and Milligan Tara. 2022. “Values and Beliefs Underlying Mutual Aid: An Exploration of Collective Care During the COVID-19 Pandemic.” Journal of the Society for Social Work and Research 13 (1): 89–115. 10.1086/716884. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Loadenthal Michael. 2020. “The 2020 Pandemic and Its Effect on Anarchist Activity.” ISPI. May 15. https://www.ispionline.it/en/publication/2020-pandemic-and-its-effect-anarchist-activity-26157. [Google Scholar]

- Lumbantobing Noah. 2020. “What Is Mutual Aid?” Ioby: Crowdfunding for Communities (blog). May 21, 2020. https://blog.ioby.org/what-is-mutual-aid-how-do-you-start-a-mutual-aid-project-in-your-community/. [Google Scholar]

- Mak Hei Wan, and Fancourt Daisy. 2020. “Predictors of Engaging in Voluntary Work During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Analyses of Data front 31,890 Adults in the UK.” MedRxiv. https://library.umsu.ac.ir/uploads/3291.pdf. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montesi Laura. 2020. “‘If I Don’t Take Care of Myself, Who Will?’ Self-Caring Subjects in Oaxaca’s Mutual-Aid Groups.” Anthropology and Medicine 27 (4): 380–94. 10.1080/13648470.2020.1715010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris Ruth. 2000. Stories of Transformative Justice. Toronto: Canadian Scholars Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mould Oh. 2021. Seven Ethics against Capitalism: Towards a Planetary Common. Cambridge: Polity Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mould Oh, Cole J, Badger A, and Brown P. 2022. “Solidarity, Not Charity: Learning the Lessons of the COVID-19 Pandemic to Reconceptualise the Radicality of Mutual Aid.” Transactions: Institute of British Geographers 47 (4): 866–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Humanities Center. 2007. “Mutual Benefit Societies.” In Primary Resources in US History. National Humanities Center. https://nationalhuman-itiescenter.org/pds/maai/community/text5/text5read.htm. [Google Scholar]

- Natural Hazards Center. 2020. “CONVERGE COVID-19 Working Groups for Public Health and Social Sciences Research.” University of Colorado. https://converge.colorado.edu/v1/uploads/images/researchonresearchers_ror-1594485622376.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson Alondra. 2013. Body and Soul: The Black Panther Party and the Fight against Medical Discrimination. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. [Google Scholar]

- O’Dweyer Emma. 2020. “COVID-19 Mutual Aid Groups Have the Potential to Increase Intergroup Solidarity—But Can They Actually Do So?” LSE. June 23. https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/politicsandpolicy/covid19-mutual-aid-solidarity/. [Google Scholar]

- Orange County Congregation Community Organization [OCCCO]. 2020. “Mutual Aid Relief Fund Resources.” Orange County Congregation Community Organization. https://www.occcopico.org/new-page-1. [Google Scholar]

- Ojeda Rosie, and Wall Maeve. 2021. “‘Power Back in the Community’: Going Beyond Performative Generosity in Nonprofits. ” Journal of Philanthropy and Marketing, e1720. 10.1002/nvsm.1720. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ostergaard Geoffrey. 1991. “Prodhoun.” In A Dictionary of Marxist Thought, 2nd ed., edited by Bottomore TB, 451–52. Cambridge, MA: Blackwell Reference. [Google Scholar]

- Parker Daniel. 2020. “Reclaiming Power: Mutual Aid in the United States.” Socialist Forum: Democratic Socialists of America. https://socialistforum.dsausa.org/issues/special-issue-the-covid-crisis/reclaiming-power-mutual-aid-in-the-united-states/. [Google Scholar]

- Parvez Z. Fareen. 2020. “Long Before COVID-19, Muslim Communities in India Built Solidarity Through Mutual Aid.” InDepthNews. July 16. https://wagingnonviolence.org/rs/2020/07/mutual-aid-india-covid19/ [Google Scholar]

- Piepzna-Samarasinha Leah Lakshmi. 2018. Care Work: Dreaming Disability Justice. Vancouver: Arsenal Pulp Press. [Google Scholar]

- Preston John, and Firth Rhiannon. 2020. Coronavirus, Class and Mutual Aid in the United Kingdom. London: Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Proudhon Pierre-Joseph. 2007. General Idea of the Revolution in the Nineteenth Century. New York: Cosimo Books. [Google Scholar]

- Pycior Julie Leininger. 2020. “Sociedades Mutualistas.” Handbook of Texas Online. January 23. https://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/entries/sociedades-mutualistas. [Google Scholar]

- Rifkin Jeremy. 2009. The Empathic Civilization: The Race to Global Consciousness in a World in Crisis. New York: TarcherPerigree. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez Havidán, Trainor Joseph, and Quarantelli Enrico L.. 2006. “Rising to the Challenges of a Catastrophe: The Emergent and Prosocial Behavior following Hurricane Katrina.” Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 604 (1): 82–101. 10.1177/0002716205284677. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sakolsky Ron. 2012. “Mutual Acquiescence or Mutual Aid?” The Anarchist Library, November 18. https://theanarchistlibrary.org/library/ron-sakolsky-mutual-acquiescence-or-mutual-aid. [Google Scholar]

- Schupak Amanda. 2020. “Behind America’s Mutual Aid Boom Lies a Long History of Government Neglect.” HuffPost. July 2. https://www.huffpost.com/entry/america-history-mutual-aid-government-neglect_n_5ef4e189c5b643f5b230f482. [Google Scholar]

- Shantz Jeff. 2001. “Mutualism: Mutualist Anarchism.” The Anarchist Library. https://theanarchistlibrary.org/library/jeff-shantz-mutualism. [Google Scholar]

- Sherman Jocelyn. 2020. “Another Way You Can Help Farm Workers During COVID-19.” United Farm Workers / SEIU. https://act.seiu.org/onlineactions/p_wK-uOOJUie4XMENNFVgg2. [Google Scholar]

- Solnit Rebecca. 2010. A Paradise Built in Hell: The Extraordinary Communities that Arise in Disaster. New York: Penguin Books. [Google Scholar]

- Spade Dean. 2020. Mutual Aid: Building Solidarity in This Crisis (and the Next). New York: Verso Press. [Google Scholar]

- Spence Hunter. 2021. The Perfect Democratic Experiment? Analyzing the Intersection of Mutual Aid Organizing and Experimentalist Governance. https://polisci.uoregon.edu/files/2021/06/Spence_Hunter.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Springer Simon. 2020. “Caring Geographies: The COVID-19 Interregnum and a Return to Mutual Aid.” Dialogues in Human Geography 10 (2): 112–15. 10.1177/2043820620931277. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan Dennis, and Tifft Larry, eds. 2008. Handbook of Restorative Justice: A Global Perspective. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Tolentino Jia. 2020. “What Mutual Aid Can Do During a Pandemic.” The New Yorker. May 11. https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2020/05/18/what-mutual-aid-can-do-during-a-pandemic. [Google Scholar]

- Town Hall Hub. 2020. “Mutual Aid Hub Map.” Mutual Aid Hub. https://www.mutualaidhub.org/. [Google Scholar]

- Vansynghel Margo. 2020. “Seattle Volunteers Look Out for Black Lives Matter Demonstrators.” High Country News. June 11. https://www.hcn.org/articles/social-justice-seattle-volunteers-look-out-for-black-lives-matter-demonstrators. [Google Scholar]

- Wakefield Juliet Ruth Helen, Bowe Mhairi, and Kellezi Blerina. 2022. “Who Helps and Why? A Longitudinal Exploration of Volunteer Role Identity, Between-Group Closeness, and Community Identification as Predictors of Coordinated Helping During the COVID-19 Pandemic.” British Journal of Social Psychology 61 (3): 907–23. 10.llll/bjso.12523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wesley Mitchell. 1933. Recent Social Trends in the United States: Report of the President’s Research Committee on Social Trends. New York: McGraw-Hill. [Google Scholar]

- Zaki Jamil. 2020. “Catastrophe Compassion: Understanding and Extending Prosociality Under Crisis.” Trends in Cognitive Sciences 24 (8): 587–89. 10.1016/j.tics.2020.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- #WeGotOurBlock. 2020. “Toolkit: Mutual Aid 101.” Mutual Aid Disaster Relief. April. https://tinyurl.com/MutualAidToolkit101. [Google Scholar]