Abstract

Stimuli-responsive nano-assemblies from amphiphilic macromolecules could undergo controlled structural transformations and generate diverse macroscopic phenomenon under stimuli. Due to the controllable responsiveness, they have been applied for broad material and biomedical applications, such as biologics delivery, sensing, imaging, and catalysis. Understanding the mechanisms of the assembly-disassembly processes and structural determinants behind the responsive properties is fundamentally important for designing the next generation of nano-assemblies with programmable responsiveness. In this review, we focus on structural determinants of assemblies from amphiphilic macromolecules and their macromolecular level alterations under stimuli, such as the disruption of hydrophilic-lipophilic balance (HLB), depolymerization, decrosslinking, and changes of molecular packing in assemblies, which eventually lead to a series of macroscopic phenomenon for practical purposes. Applications of stimuli-responsive nano-assemblies in delivery, sensing and imaging were also summarized based on their structural features. We expect this review could provide readers an overview of the structural considerations in the design and applications of nanoassemblies and incentivize more explorations in stimuli-responsive soft matters.

Keywords: Stimuli-responsive, Amphiphilic macromolecules, Structural determinants, Nanoassemblies, Self-assembly, Disassembly, Biomedical applications

Graphical Abstract

1. Introduction

Biological processes generally rely on the adaptive response to biomolecules and environmental stimuli to initiate structural and functional alterations. With myriad of covalent transformations and non-covalent interactions occurring concurrently and in sequence, nature also uses compartmentalization to organize these events and accommodate incompatibilities [1,2]. Mimicking nature by packing functional molecules into compartments to protect the payloads from leakage and damage, while performing on-demand activation in response to changes in the surrounding environment, has been a design target. Artificial macromolecules have been applied for self-organization into nanostructures, taking advantage of their propensity for compartmentalization and controlling the adaptive structural transformations and activity of payloads in response to surrounding stimuli [3,4]. These self-organized nanostructures, a.k.a., nano-assemblies, have drawn significant attention due to their broad materials and biomedical applications.

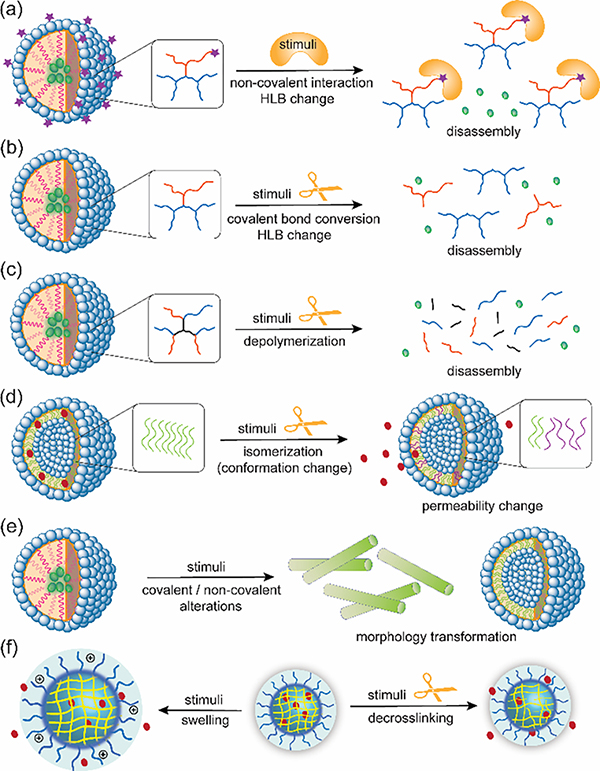

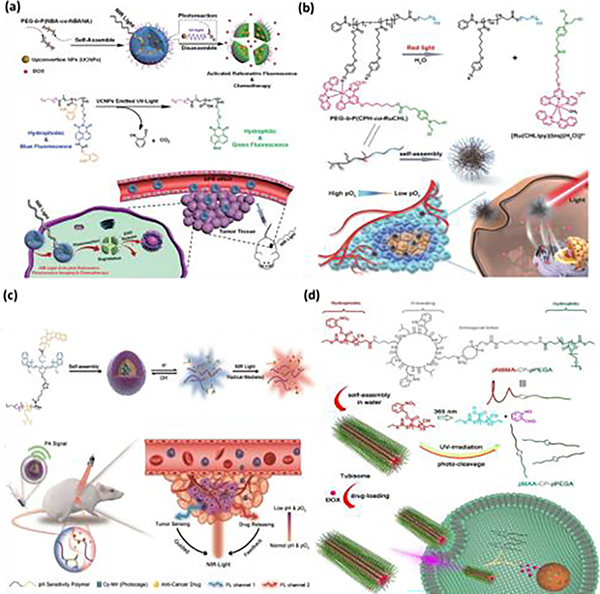

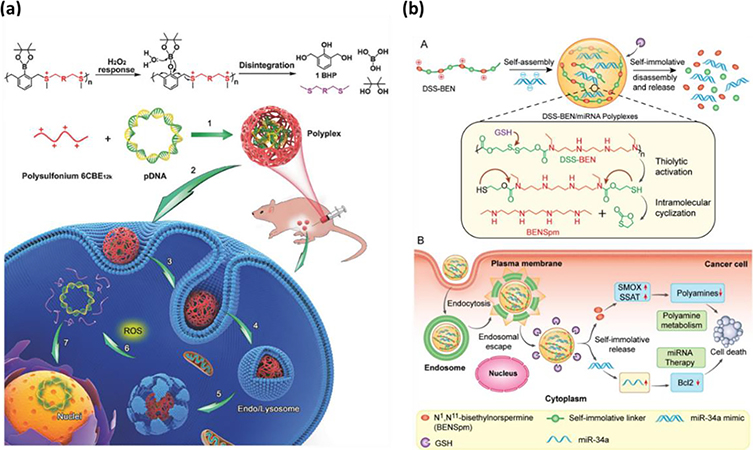

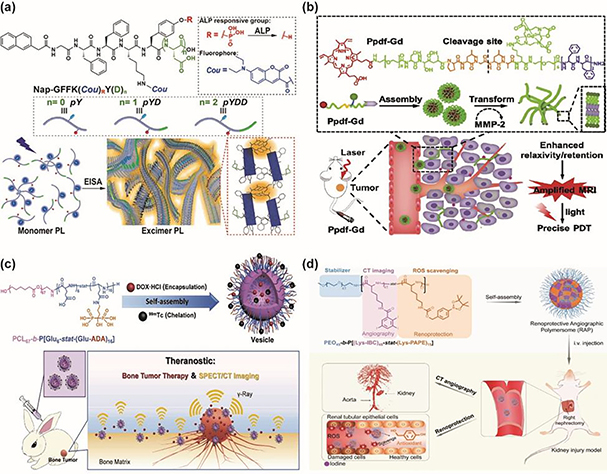

Over the past few decades, there has been extensive research on amphiphilic macromolecules with built-in triggers to control assembly/disassembly behaviors upon exposure to a specific stimulus for delivery, catalysis, agriculture, and sensing/imaging applications [5–11]. Tailoring macromolecules that respond to chemical, physical, and biological stimuli enable structural alterations to activate on-demand functions in nano-assemblies. Molecular design for this purpose often involves stimulus-induced changes at the molecular level, including disruption of hydrophilic-lipophilic balance (HLB), depolymerization, decrosslinking, changes in molecular conformation/configuration, and packing (Fig. 1). These changes subsequently impact factors such as solubility, morphology, size, permeability, and colloidal stability of the assemblies. A wide range of chemistries such as functional group transformations, configurational changes, and self-immolative chain reactions have been developed to this end. Strategic installation of these triggerable moieties into macromolecules to maximize the targeted changes enables the translation of the molecular scale structural transformations to nanoscale assemblies in response to surrounding stimuli and external triggers.

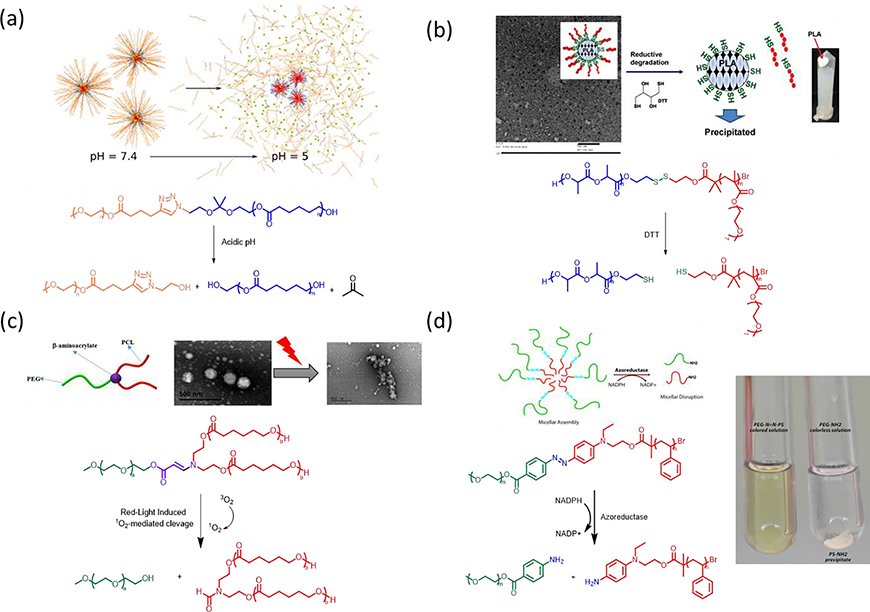

Fig. 1.

Different strategies for stimuli-triggered alterations in nano-assemblies: (a) Disassembly via HLB change by the disruption of non-covalent interactions, (b) disassembly via HLB change by the disruption of covalent bond, (c) disassembly via depolymerization, (d) permeability change via conformation/configuration alterations, (e) stimuli-triggered morphology transformation, (f) stimuli-triggered swelling or decrosslinking of crosslinked nano-assemblies.

Over the course of this review, we will focus on the recent advances in responsive amphiphilic macromolecular nano-assemblies from the perspective of structural determinants in polymers that dictate their assembling/disassembling behaviors. An analysis on structure-property relationships of amphiphilic molecules, classification of stimuli, assembly fidelity in the presence and absence of various stimuli, and areas in which these materials find applications are anticipated to give reader a comprehensive overview of this field and ignite new ideas for designing the next generation “smart” materials using amphiphilic macromolecules. Organizationally, we aim to first categorize the types of stimuli (i.e., chemical, physical, and biomacromolecular stimuli), triggerable moieties, and their responsive behavior. Considering many reviews on this topic [12–20], we herein specifically focus on the structural determinants in nano-assemblies and aim to helping readers to gain a better understanding on trigger-induced processes. We then focus on tactics adopted in nanostructure transformation and provide viewpoints of how structural determinants at molecular level are associated with nano- and macroscopic phenomena. A comprehensive analysis of molecular structure, stimuli-triggered assembly alterations and macroscopic responses will be integrated in the following section. Finally, recent applications in stimuli-responsive nano-assemblies are summarized based on the structural transformation-guided strategies. We believe that the discussion on structural determinants behind alterations at molecular, macromolecular, and nanoscopic levels will help widen the horizon and incentivize advances in macromolecular soft matters.

2. Commonly used stimuli for responsive disassembly

A wide variety of stimuli-responsiveness have been exploited to trigger structural alterations of nano-assemblies, which can be classified into chemical, physical, and biological stimuli on a basis of triggering sources. Extracorporeal physical stimuli such as temperature, light, and mechanical force can induce covalent and non-covalent structural alterations with spatiotemporal precision. Nano-assemblies at the site of interest that receive a specific physical excitement at a certain magnitude cause changes in structural integrity. Macromolecules that are sensitive to chemicals such as reactive oxygen species (ROS), reducing agents, glucose, and pH offer the opportunity for response to specific microenvironments encountered in nature. Finally, nano-assemblies can be programmed to respond to contact with specific biomacromolecules through covalent modifications due to enzymatic reactions or non-covalent alterations such as binding events with proteins. In this section, we give a brief introduction to each of the stimuli and the general opportunities that present to design responsive soft matter.

2.1. Physical stimuli: temperature, light and mechanical force

Temperature

The oft-used response in temperature-responsive macromolecules involves abrupt phase change in aqueous media. These changes are akin to sol-to-gel transition or vice versa at the molecule’s cloud point temperature (Tcp). This transition point is also known as the lower critical solution temperature (LCST) or the upper critical solution temperature (UCST), depending on the direction of phase transition [21]. Macromolecules with LCST character are soluble in aqueous solution below the Tcp, often due to the hydrogen bonds formed between thermoresponsive moieties and water molecules. Upon heating, the hydrogen bonds weaken, causing an increase in the molecular hydrophobicity, which leads to chain collapse and increased turbidity [22,23]. For macromolecules that exhibit an UCST behavior, stronger intra- and inter-chain interactions due to hydrogen bonds or electrostatic interactions result in poor aqueous solubility at lower temperatures. Hence, solubility increases upon heating because of hydration of thermoresponsive moieties by the surrounding water molecules that dissipates the intra- and inter-chain interactions [24]. The tunable Tcp range of polymers can be adjusted by various factors such as monomer structure, chain length, composition, and morphology of polymers, as well as the solvent, polymer concentration, counter ions, salt type and concentration, and additives. The molecular considerations necessary for the design of thermoresponsive nano-assemblies have been extensively discussed and summarized in our previous review [25]. Additional information regarding the design and applications of thermoresponsive materials has also been discussed by other research groups [26,27].

Light

Controlling a chemical process at the site of interest and the appropriate timing offers a tremendous opportunity for precise activation. Light is a versatile trigger with controllable parameters of irradiation time, site, wavelength, and intensity, allowing for structural transition of macromolecular nano-assemblies with spatiotemporal precision. Macromolecules with hydrophobic, photocleavable pendants could undergo hydrophobic-to-hydrophilic transition upon light irradiation [28]. Common photocleavable aryl (methyl)ester groups such as pyrene [29], o-nitrobenzyl [30], coumarin [31], and perylene [32], linked to the polymer backbone provides nano-assemblies with hydrophobicity and structural integrity. Upon bond breakage of the photochromic moieties during photochemical reactions, the resulting hydrophilic (meth)acrylic acids can lead to structural disintegration (Table 1). Photocleavable groups can be repeatedly inserted into the main chain or placed at the head group of self-immolative hydrophobic core-forming blocks [33,34]. In response to light triggers, cascade degradation of self-immolative blocks or simultaneous chain shattering degradation of hydrophobic main chains lead to the disruption of assemblies [35–37]. One major challenge of photo-responsive systems is the limited penetration ability of the light used to trigger the desired responses. In recent years, great advances have been achieved with upconversion materials and photocleavable molecules in response to deep red or near-infrared (NIR) light of phototherapeutic window (650–900 nm) to expand the horizon of feasibility [38–40]. Despite the availability of various light sources, the limited penetration depth of light within a range of millimeters still poses a significant challenge for a wide variety of applications [41].

Table 1.

Photoactive moieties and corresponding behaviors.

| Photochemistry | Responsive moiety | Absorption range | Responsive behavior |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bond cleavage | Pyrenylmethyl ester [29,52] | 300–500 nm |

|

| o-Nitrobenzyl ester [53] | 350–500 nm |

|

|

| Coumarinyl ester [31] | 350–450 nm |

|

|

| Perylene-3-ylmethyl ester [54] | 350-550 nm |

|

|

| Ruthenium complex [55] | 350–500 nm |

|

|

| Boron-dipyrromethene [56] | < 693 nm |

|

|

| Heptamethine cyanine [57,58] | 690–780 nm |

|

|

| Isomerization | Azobenzene [59,60] | (trans to cis) 320–350 nm; (cis to trans) 400–450 nm |

|

| Spiropyran [61] | (SP to MC) 300–400 nm; (MC to SP) 450–650 nm |

|

|

| Bis-dithienylethene [62,63] | (cis to trans) 280–360 nm; (trans to cis) 450–720 nm |

|

|

| Dimerization | Coumarin [64,65] | (unimers to dimer) >310 nm; (dimer to unimers) <260 nm |

|

| Anthracene [51,66] | (unimers to dimer) >350 nm; (dimer to unimers) <300 nm |

|

|

| Styrylpyrene [49,67] | (unimers to dimer) 400–560 nm; (dimer to unimers) ≤360 nm |

|

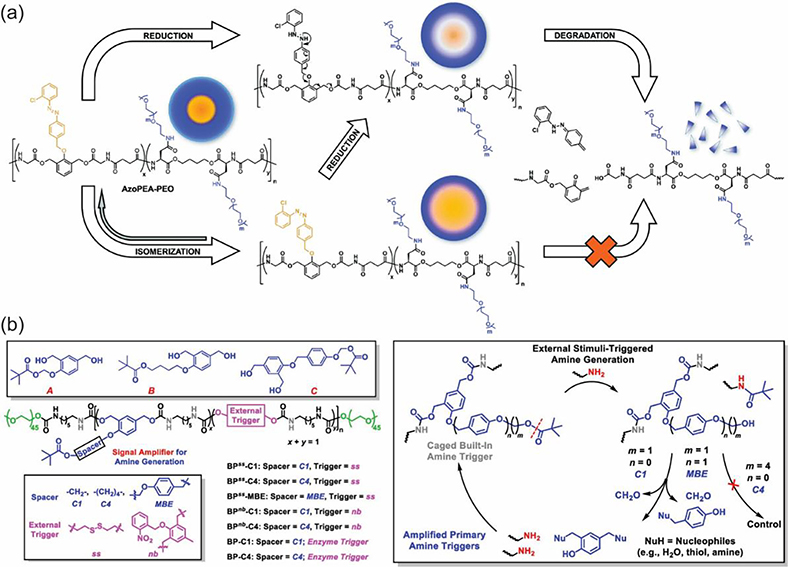

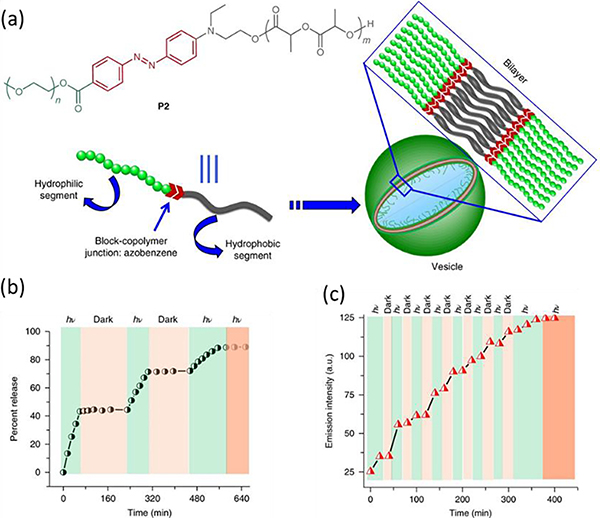

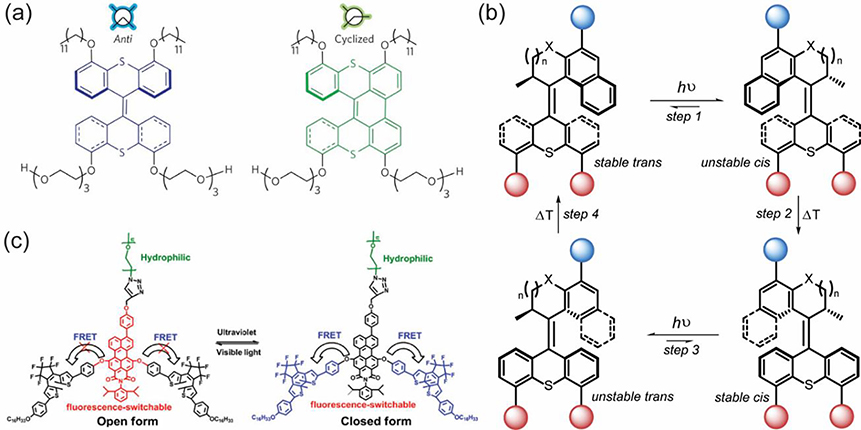

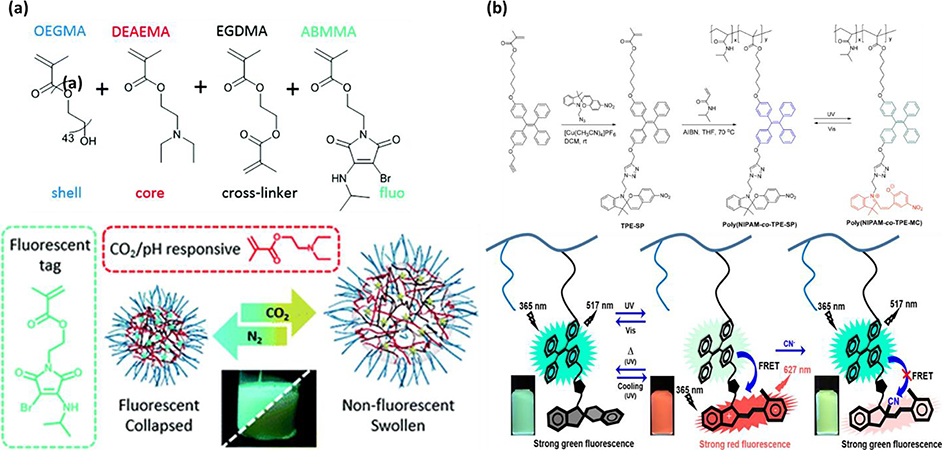

Photoisomerization is a reversible process that changes the hydrophilicity or molecular packing through bond scissoring or rotation, allowing for recurring transitions between structural construction and disruption. While the reversible nature of photoisomerization is useful for controlling structural transitions, the photoinduced reversibility might not be fully achieved due to the photochromic fatigue after several irradiation cycles. For example, trans-cis photoisomerization of phenyl rings on either side of nitrogen-nitrogen double bond provides azobenzene-containing nano-assemblies with the momentum for light-induced disruption [42]. The azobenzene in the apolar trans form (dipole moment ~ 0 D) converted to the polar cis form (dipole moment ~ 4.4 D) upon light irradiation gives rise to the increasing polarity of macromolecules,[43] leading to the disruption of nano-assembles [43]. Moreover, tight stacking of azobenzene in the trans orientation was found to help solidify structural integration while cis form upon light triggering causes distortion of molecular packing and leads to leaky structure. However, the complete disruption of nano-assemblies containing azobenzene is barely achievable due to the photochromic fatigue.

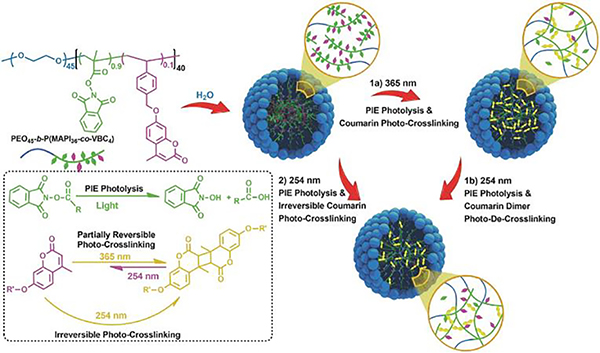

Reversible crosslinking and decrosslinking in response to light provides macromolecular assemblies with a switch to tune the structural integrity on demand. Photoisomerization from hydrophobic, ring-closed spiropyrans (SP) to charged, ring-opened merocyanines (MC) can reversibly trigger hydrophilic-lipophilic imbalance to control the rupture and formation of nanoassemblies [44,45]. Colloidal instability is one of the challenges to be solved for the design of stimuli-responsive systems. Photo-crosslinking can enhance the resilience of nano-assemblies to extreme dilution, while photo-decrosslinking can facilitate the release of entrapped guest molecules. For example, the heavily used coumarin moieties can undergo [2 + 2] photocycloaddition upon light irradiation at λ > 310 nm and photo-cleavage of cyclobutane bridges upon light irradiation at λ < 260 nm [46]. The pendant coumarins provide macromolecules with hydrophobicity for assembly formation and further solidify the structure stability via photodimerization. Enhanced core density upon photodimerization has been utilized to stabilize the encapsulated hydrophobic molecules while enhanced payloads release upon photo-decrosslinking [46–48]. However, similar to photoisomerization, coumarins have been found to undergo photodamage after multiple cycles, resulting in incomplete crosslinking and decrosslinking. The incomplete nature of these processes can also be attributed to the photostationary states of the chromophores at different wavelengths. In contrast to the reversible photo-crosslinking of coumarins, which occurs in the UV region, styrylpyrene [49] and anthracene [50,51] were developed for reversible assembly and disassembly upon light irradiation at visible wavelength λ > 380 nm) Table 1).

Mechanical force

Mechanical force is an effective method for achieving spatiotemporal precision in a triggering event without harming peripheral healthy tissues to the triggering sites. The use of ultrasound in medical applications is intriguing due to its non-invasiveness, absence of ionizing irradiation, and ability to penetrate into deep tissues. Ultrasounds are mechanical waves propagating in a medium through changes in pressure, at frequencies higher than 20 kHz. Frequency and intensity are important parameters in ultrasound, where frequency modulates the depth of tissue penetration and cavitation, and intensity controls the energy transmitted to the site of interests [68]. In general, ultrasound can trigger the transformation of macromolecular assemblies via mechanical and thermal effects. High intensity focused ultrasound (HIFU) at frequency ranging from 600 kHz to 7 MHz generates high hyperthermia (> 43 °C) at the focal point while inertial cavitation induced by low-frequency ultrasound at 20 to 90 kHz cause shear force and free radical formation [69]. HIFU has been used to boost the hydrolysis of 2-tetrahydropyranyl methacrylate (THPMA) copolymer that resides at hydrophobic core of micelles to cause the HLB change and enhance the LCST sensitivity from 25 °C to 42 °C, resulting in the disassembly of macromolecules and payload release [70]. Ultrasound-induced cavitation can transiently enhance permeability of curcumin-loaded particles and recover structural integrity within short time post-irradiation, resulting in spatiotemporal drug release and repetitively triggered drug release on demand [71]. Indirect disintegration of macromolecular assembly in response to ultrasound can be achieved by sonodynamic property under ultrasonic cavitation. Sonosensitizer hypocrellin-loaded poly(ethyleneglycol)-poly(propylenesulfide) micelles underwent disassembly upon ultrasonic irradiation. Hypocrellin molecules generated reactive oxygen species (ROS) that oxidized hydrophobic sulfide to hydrophilic sulfone, giving rise to HLB change and the disassembly of particles [72].

2.2. Chemical stimuli: pH, ROS, redox and diols (glucose)

pH

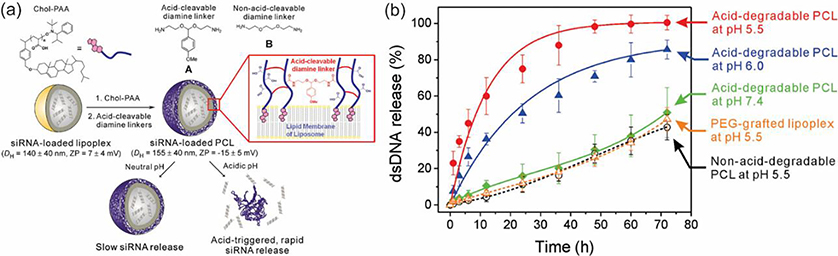

pH-responsive moieties have been incorporated in nano-assemblies for triggerable structural transformation via several strategies, including HLB change, depolymerization and decrosslinking. The building blocks of the macromolecules are designed to sense changes in pH values via charge shifting or acid-induced bond cleavage. Charge shifting by pH changes could generally lead to alterations in hydrophilicity of polymers, resulting in either disassembly or the swelling/shrinking of particles. Acid-induced bond cleavage on the other hand causes the breakage of acid-labile bonds in macromolecular nano-assemblies, compromising the driving forces of particle formation, such as hydrophobic interactions and chain-chain crosslinking to cause the disassociation of nano-assemblies. When pH-responsive moieties are employed as repeating units on polymer backbones, pH-induced cleavages could cause depolymerization and disintegration of assemblies. Overall, pH-responsive groups are the most widely studied functionalities in macromolecular assemblies, independently or synergistically with other responsive groups to achieve controllable responsiveness. We direct readers to several reviews that summarized comprehensive strategies to design pH-responsive polymeric nano-assembly for diverse applications [73–75].

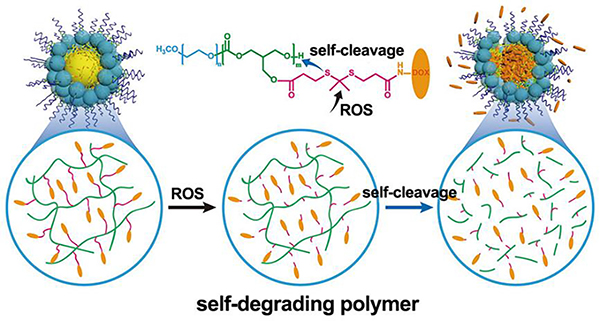

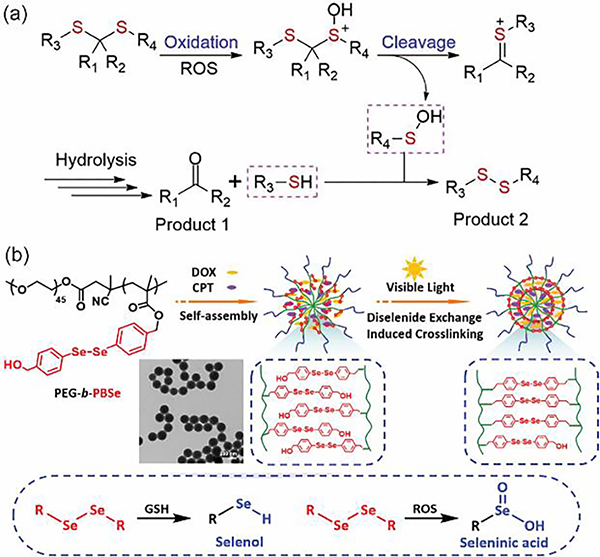

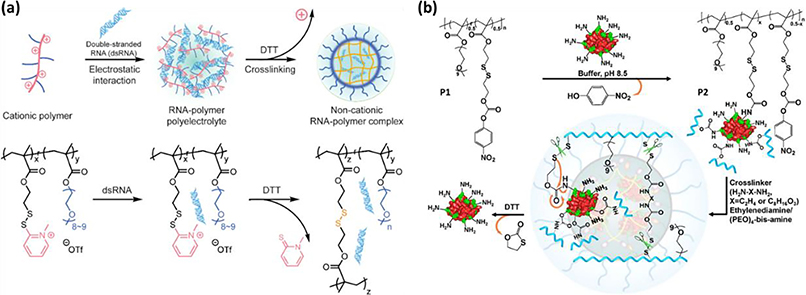

Redox

Macromolecular assembly/disassembly transitions in response to redox stimuli (i.e., reductive, and oxidative stimuli) are dictated by the structural determinants with triggered bond breakage and changes in HLB. ROS and reducing agents (e.g., glutathione, GSH) are the two major categories of stimuli in the development of redox-responsive macromolecules, though gas molecules such as reactive nitrogen and sulfur species involved in physiological and pathological pathways are emerging areas for biological applications. For comprehensive discussion on reactive oxygen, nitrogen, and sulfur species responsive macromolecules, we direct the readers to an excellent review focusing on responsive macromolecules and their molecular assemblies for biomedical applications [76]. ROS including radical species of superoxide anion radical (O2•−) and hydroxyl radical (HO•), and non-radical species of hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), singlet oxygen (1O2) and hypochlorous acid (HOCl) are found overexpressed in signal transduction or stress response of inflammation, oxidative stress, and aging [77–80]. ROS-responsive moieties such chalcogen ether including thioether, selenoether and telluroether, thioketal, and arylboronic ester are widely leveraged in the design of macromolecules with triggered disassembly behavior [81,82]. The oxidation of chalcogen ethers built in hydrophobic chains increases the hydrophilicity of amphiphilic macromolecules, altering the HLB to trigger the disruption of nano-assemblies. For example, hydrophobic thioether that can be oxidized into sulfoxide and sulfone with higher water solubility are heavily incorporated into amphiphilic macromolecules for the control of assembly/disassembly transition since an early example of the use of oxidative conversions to destabilize nano-assemblies in 2004 (Table 2) [83]. Thioketal in response to a broad spectrum of ROS including H2O2, HOCl, HO• and O2•− can be degraded into acetone and thiols [84,85]. Incorporation of ROS-responsive thioketal into macromolecules endows nano-assembly with a switch for triggered bond breakage and structural disruption. Arylboronic ester is another commonly used ROS-responsive functional group due to its high selectivity and sensitivity [86]. The oxidation reaction of arylboronic ester with H2O2 results in the formation of boronic acid and phenol species that can further trigger polymer fragmentation via electronic cascade processes-induced bond cleavages, triggering the disruption of macromolecular nano-assemblies.

Table 2.

Redox-responsive moieties and corresponding behaviors in response to stimuli.

| Responsive moiety | Stimulus | Responsive behavior |

|---|---|---|

| Chalcogen ether | ROS |

|

| Thioketal | ROS |

|

| Arylboronic ester | ROS |

|

| Diselenide | ROS and GSH |

|

| Disulfide | GSH |

|

| Dithiomaleimide | GSH |

|

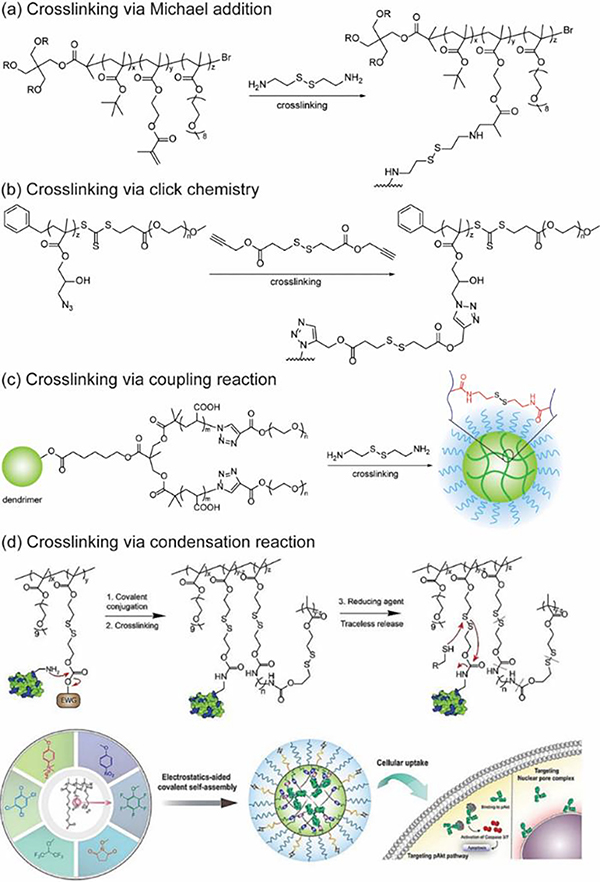

GSH, a tripeptide of glutamate, cysteine, and glycine, is the most abundant and endogenous small thiol molecule that acts as an antioxidant and regulates cellular redox homeostasis [87,88]. The dramatic difference of GSH concentration between intracellular environment (1–10 mM) and extracellular compartment (1–10 μM) provide reduction-responsive polymeric nanoassemblies with a hallmark for triggering structural transformation [89–91]. As a well-studied GSH-responsive functionality, disulfide has been installed at various position of macromolecules (backbones vs. sidechains) which can provide nano-assemblies with distinct disintegration properties upon treatment with GSH [92]. For example, incorporation of multiple disulfide bonds into the main chain of hydrophobic block can cause chain shattering and induce the degradation of nano-assemblies. Single disulfide bond built at the junction point of hydrophobic and hydrophilic blocks, in the core-forming crosslinkers, or in between hydrophobic block can lead to hydrophilic-lipophilic imbalance, inducing the destabilization of nano-assemblies. Recently, poly disulfides) have gained considerable attention due to the triggering degradation of disulfide bonds installed in the main chain of macromolecules [93,94]. Disulfide-containing polymers are typically elaborated via chemical oxidation, photo-polymerization, thermal polymerization, thiolate-initiated ring-opening polymerization, or cryo-polymerization and their applications in responsive assemblies have been discussed in Section 4 and 5. Similar to disulfides, dithiomaleimide (DTM) has been widely used in bioconjugation, responsive polymer materials, drug delivery, and imaging probes given the sensitive responsiveness to GSH [95–100]. The decoration of DTM at the joint of amphiphilic polymers provides nano-assemblies with GSH-responsive cleavage of DTM linker, inducing destabilization and particle disruption [101–105]. Taking advantage of elevated expression level of GSH and ROS in cancer and inflammatory disease, redox-responsive polymer materials have been generally leveraged in the development of nanomedicines and imaging techniques. We direct the readers to the recent report on nanomedicines via redox approach [106]. Furthermore, redox-responsive moieties along with self-immolative chemistry have been widely introduced into the nano-assemblies of prodrug and polyprodrug amphiphiles [13].

Diols (glucose)

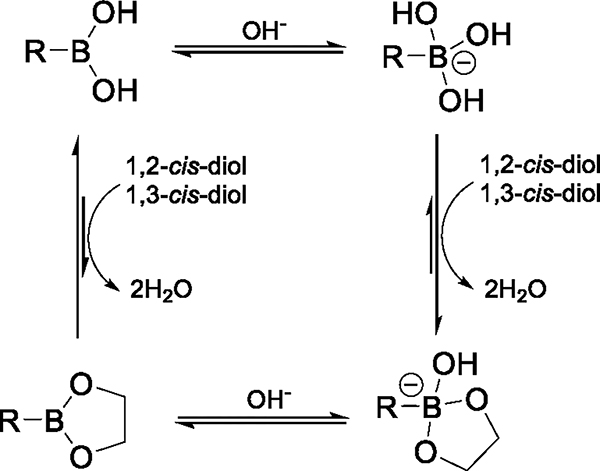

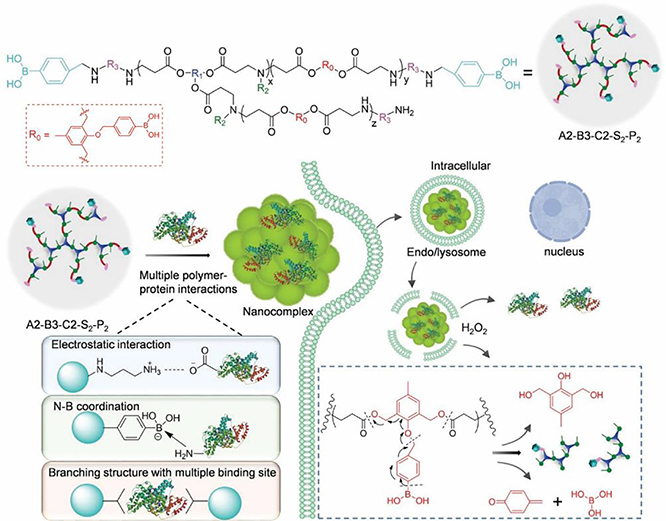

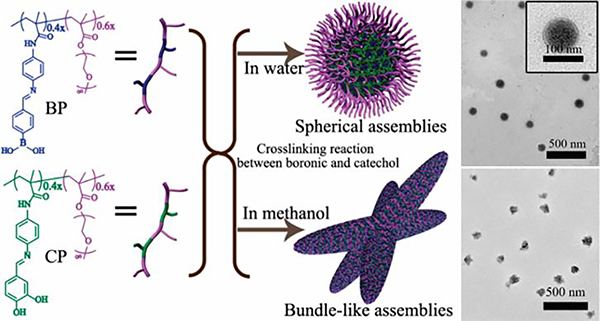

Diol-responsive macromolecules have been widely used in biomedical applications due to the abundant polysaccharides in biosystems. In particular, boronic acid-containing macromolecules show a wide variety of applications, including self-healing hydrogels, drug delivery, biologics delivery, sensor, and boron neutron capture therapy, given the versatile features of boronic acid, such as dynamic covalent bonds, responsive to ROS, pH and molecules containing diol (i.e., sugar, adenosine triphosphate (ATP), and ribose), and cancer-targeting capability [20,86]. Here, we focus on the boronic acid-containing macromolecules in response to molecules containing diol and their chemistry behind the determinants of structural alteration. Boronic acid mainly acts as a Lewis acid due to the vacant p-orbital on the boron center, which allows the formation of reversible boronate ester with 1,2-cis-diols or 1,3-cis-diols. In the neutral form, boronic acid exists as a trigonal planar sp2-hybridized boron, sharing a bond with either an alkyl or an aryl group, and along with two hydroxyl groups, giving rise to six valence electrons on boron center (Fig. 2, top left). In aqueous solution, boronic acids exist in equilibrium between the neutral, hydrophobic form of boronic acid and the hydrophilic, tetrahedral hydroxyboronate anion after complexation with a hydroxide ion (Fig.2, top right). Hence, boronate esterification is favorable at pH values higher than pKa. With manipulation of substituents on boronic acid, the pKa of boronic acids is tunable from 4.0 to 10.5. The binding interaction between boronic acid and diol is highly affected by the substituents on both molecules and pH value of surrounding environment, in which dynamic covalent interaction provides polymeric materials with modulable and predictable response to biological molecules for biomedical application, including glucose-responsive insulin delivery and sensors of monitoring blood glucose level. Detailed utilities of boronic acid/ester-based molecular determinants in stimuli-responsive assemblies are introduced in Section 4 and 5.

Fig. 2.

Esterification equilibrium between boronic acids and diols.

Apart from the above-mentioned stimuli, some gases have also been used as stimuli to trigger assembly alterations. For example, CO2 [107] and SO2 [108] could be used as stimuli to trigger the cleavage of acid-labile bonds and charge shifting of some pH-responsive groups, as the two gases could dissolve in water to form carbonic acid and sulfurous acid respectively, generating an acidic environment and leading to specific alterations. Gases like H2S could act as reducing agents to reduce azide to amines and trigger the corresponding transformation of assemblies [109]. Other gases such as formaldehyde [110] and CO were also utilized as stimuli to initiate fluorescence or polymer degradation [111], but their study in responsive assemblies is still rare. As most of the gases could eventually function as the above-mentioned stimuli (acid, redox or ROS), specific examples would be introduced together with other chemical-based stimuli instead of in an independent section.

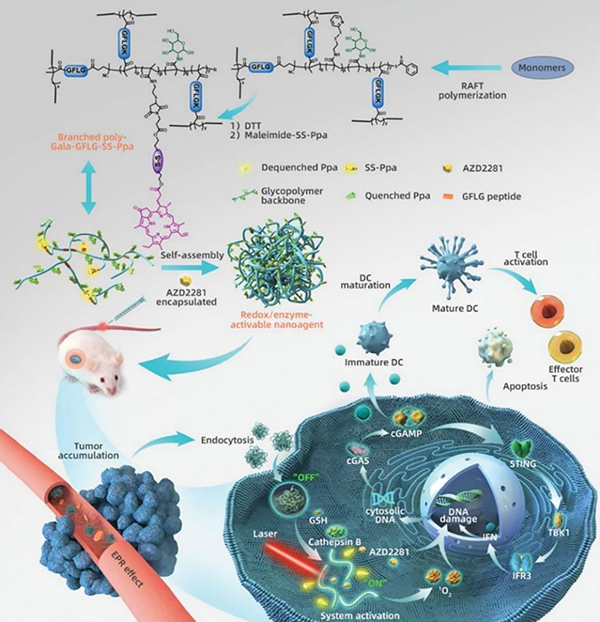

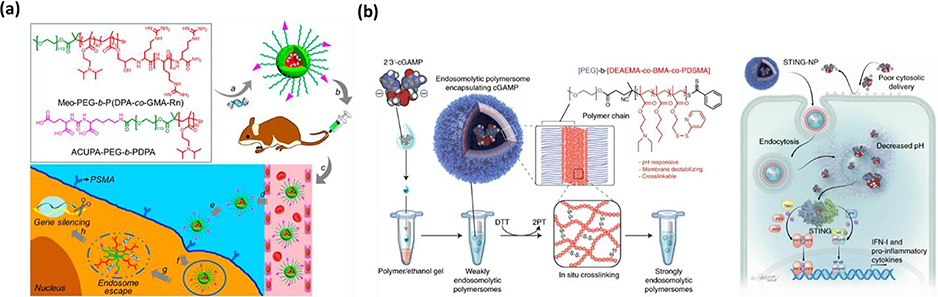

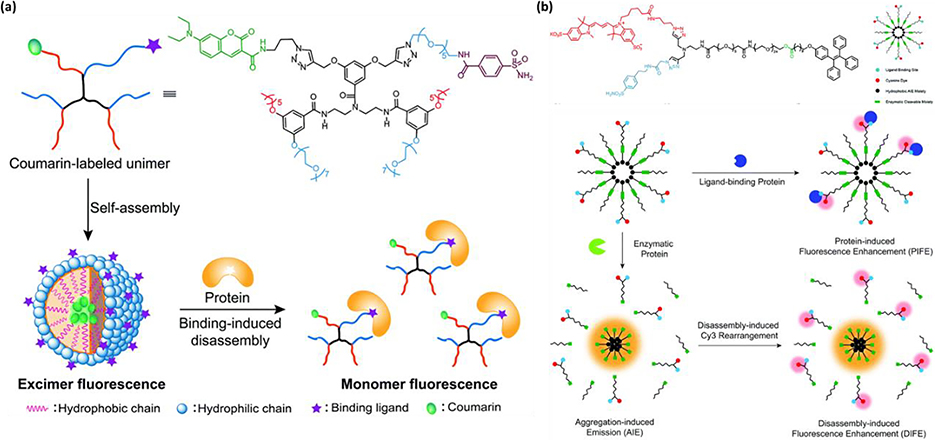

2.3. Biomacromolecules: proteins

Structural alterations associated with protein can be generally categorized into enzymatic bond breakage and binding-induced imbalance between unimer and aggregate of macromolecules [76,112–115]. Through enzymatic cleavage, the hydrophobic-to-hydrophilic transition or vice versa can trigger the changes in HLB to initiate the formation or disruption of macromolecular nano-assembly [116–120], to drive particle morphology change [121–123] or to modulate the complexity of nanoparticles [124–128]. Enzyme-initiated depolymerization of polymer segments is also utilized to trigger particle disassembly. Upon enzymatic digestion, deprotecting group can undergo cascade self-immolation via elimination or cyclization, resulting in depolymerization and particle shattering [129,130]. In addition to enzymatic bond cleavage, noncovalent binding of protein (specifically and non-specifically) to nano-assemblies can perturbate HLB and compromise structural integrity [131,132]. For example, polyelectrolyte nano-assemblies have been found to interact with complementarily charged protein, causing structural disruption. Specific recognition between proteins and ligands decorated on nanoassemblies can undergo binding-induced disassembly on demand.

3. Stimuli-triggered interruption of HLB

As the self-assembled structures from amphiphilic molecules rely on the latter’s HLB, stimulus-induced perturbation of this balance is a convenient approach to trigger nano-structural transformations [4]. Side chain or main chain functionalities in the polymer can be triggered to be cleaved or transformed to alter HLB that induces nano-structural destabilization. Similarly, the disassembling behavior can be triggered by attaching biomacromolecules via specific recognition on macromolecular nano-assemblies due to the interruption of HLB.

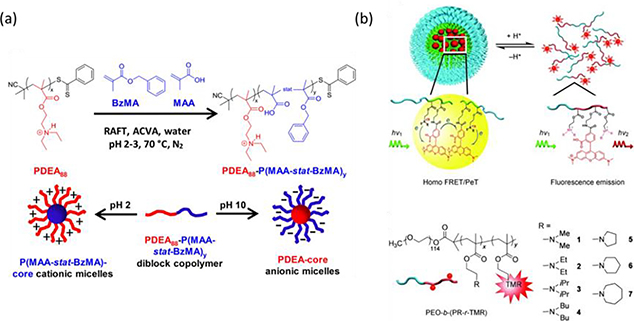

3.1. Interruption of HLB without polymer fragmentation

Amphiphilic moieties that are key to the assembly process can be used to trigger changes in hydrophobicity, leading to structural disintegration or morphological transition [73,74,133]. A vast body of literature has been dedicated to investigating how stimuli-responsive polymers undergo changes in hydrophobicity in response to triggers and their implications for interrupting HLB and inducing structural transformations. Here, we focus on describing how polymers respond to different types of stimuli along with a few examples that induce HLB change. pH variations have generated a wide variety of nano-assemblies that can undergo structural transformation due to charge shifting. The hydrophobic-to-hydrophilic transition or vice versa could be attributed to charge shifting of neutral polymers (e.g., amines) that change from hydrophobic to positively-charged/hydrophilic with the decrease in pH, or anionic polymers (e.g., carboxylates) that convert from negatively-charged/hydrophilic to neutral/hydrophobic as pH decreases. For example, amphiphilic block copolymers containing two segments that show oppositely charge-shifting behavior are known to exhibit a schizophrenic character that form a stable micelle at high pH, while converting into reverse micelle as pH decreases [134]. The diblock copolymer, poly(4-vinyl benzoic acid60-block-2-(diethylamino)ethyl methacrylate66) P(VBA60-b-DEA66), can reversibly form stable micelles and reverse micelles by simply switching pH. Here, the stable anionic micelles, with the size of 66 nm, have deprotonated PVBA (pKa = 7.1) anionic shells and hydrophobic PDEA core (pKa = 7.3) at pH 9.2, while the formation of positively-charged reverse micelles, with the size of 36 nm, comprising cationic shells of protonated PDEA and PVBA core was observed at pH 2 [135]. The schizophrenic character of block copolymer was further validated by dual-color self-reporting pH-responsive poly(2-(diethylamino)ethyl methacrylate-block-poly(methacrylic acid-statistical-benzyl methacrylate) (PDEA-P(MAA-stat-BzMA) (Fig. 3a) [134]. A pink copolymer dispersion from rhodamine B methacrylate (RhBMA) incorporated in between PDEA shells was observed at pH 2, whereas fluorescence of fluorescein O-methacrylate (FMA) along with MAA and BzMA core was quenched possibly due to aggregation-indued quenching. At pH 10, FMA was activated at the shells of P(MAA-stat-BzMA) while fluorescence of RhBMA was dormant at the PDEA core. In addition to schizophrenic character, pH-responsive charge shifting was leveraged to develop ultrasensitive, reversible nanoprobes with assembling/disassembling behavior owing to supramolecular cooperativity [136,137]. Reversible assembling/disassembling behaviors between amphiphilic macromolecules in response to pH changes gives rise to cooperative protonation/deprotonation. The all-or-nothing two-state between free polymers, or unimers, and micelles can lead to ultrasensitive pH nanoprobes comprising fluorophores with small Stoke shifts (< 40 nm) along with protonatable block (Fig. 3b) [138]. Tertiary amines with various hydrophobic substituents as ionizable block of PEG block copolymer are used to tune the transition pH values. The degree of substituent hydrophobicity dramatically affects the protonation of micelles with different pKa. Sharp pH response of multicolor nanoprobes can be achieved by introducing various types of fluorophores that showed quenching based on homo F rster resonance energy transfer (FRET) in constrained hydrophobic core. Moreover, mixing the same polymers containing fluorescence quenchers with fluorophore-labeled polymers during the micellization can expand the nanoprobes with broad selection of fluorescence emission, which was previously limited by the use of fluorophores with only homo FRET [139]. Micellization confines the fluorophores and quenchers in the core, leading to dormant fluorescence. Due to ultrasensitive cooperative disassembly, facile all-to-nothing transition of micelles enables to dissociate the quenchers and turn on the fluorescence. Similar pH-induced assembly or aggregation was also adopted in aggregation-induced emission (AIE) nanoprobes [140]. Crosslinking nanoparticles with pH-responsive diethylamino or carboxylic groups were used to tune the on/off state of AIE fluorescence in response to changes in pH values. pH-responsive charge shifting polymers have shown a wide variety of structural transformations dictated by changes in charged property and hydrophobicity. We note that pH-responsive polymers have made significant progress in controlling assembling/disassembling behaviors of nano-assemblies. We direct readers to reviews with a plethora of examples in this context [73,74,133].

Fig. 3.

(a) The copolymerization of methacrylic acid and benzyl methacrylate by RAFT aqueous emulsion polymerization (top panel), and the schizophrenic micellization behavior of PDEA88-P(MAA-stat-BzMA)y diblock copolymers in acidic and basic aqueous solution (bottom panel) [134], Copyright 2017. Adapted with permission from the American Chemical Society. (b) Mechanisms of homo Förster resonance energy transfer and photoinduced electron transfer behind tunable, ultrasensitive pH-responsive nanoparticles, where the neutralized PR segments that could self-assemble into the micelle cores at pH > pKa led to quenching of fluorophores while formation of unimers at pH < pKa lighted on fluorescence (top panel). Structures of the PEO-b-(PR-r-TMR) copolymers (PEO = poly(ethylene oxide), PR = ionizable block, TMR = tetramethyl rhodamine, and R = dialkyl and cyclic substituents) (bottom panel) [138], Copyright 2011. Adapted with permission from John Wiley & Sons Inc.

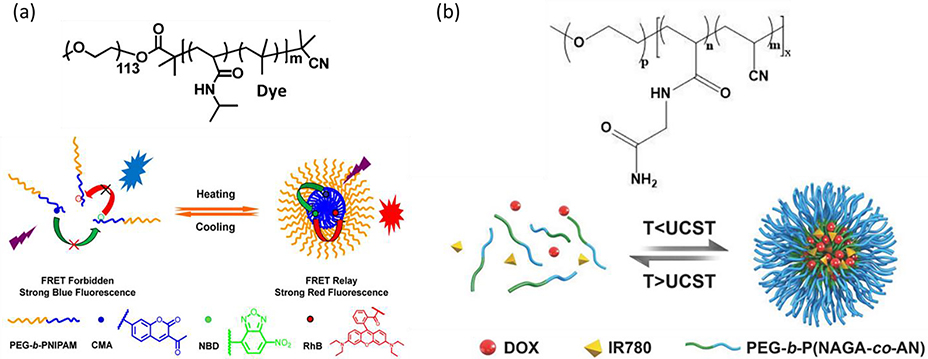

Since the thermal phase transition of infamous poly(N-isopropylacrylamide) (PNIPAM) was reported in 1967 [141], temperature-responsive materials have been heavily investigated as biomedical and smart materials [26,142,143]. Given the LCST around body temperature (32 °C) in water [144], PNIPAM has been widely explored for biomedical applications. For example, block copolymers of poly(ethylene glycol)-block-poly(N-isopropylacrylamide) (PEG-b-PNIPAM) individually labeled with dyes were developed for temperature imaging of live cells by ratiometric fluorescence (Fig. 4a) [145]. The cascade FRET behaviors between dyes were modulated through the transition between unimers and micelles upon heating and cooling, in which the distance between dyes can be manipulated by the degree of aggregation of PNIPAM at various temperatures. To probe the thermal dynamics in cells, a nanothermometer composed of poly(N-isopropylacrylamide-co-tetrabutylphosphoniumstyrenesulfonate) [P(NIPAM-co-TPSS)] decorated with AIE molecules, 3-ethyl-2-[4-(1,2,2-triphenylvinyl)styryl]benzothiazol-3-ium iodide (TPEBT), on TPSS [146]. At the temperature below LCST of PNIPAM, P(NIPAM-co-TPSS) can self-assemble into micelles with the size of 140 nm, comprising PNIPAM shells and PTPSS core. In this aggregation state, TPEBT exhibits strong fluorescence within the PTPSS core. Upon heating in the range of 25–45 °C, a linear correlation between fluorescence and temperature within 32–40 °C was observed. During the heating process, the hydrogen bonds between the amide groups of PNIPAM and water molecules weakened, leading to dehydration of the alkyl group and aggregation of PNIPAM chains. As a result of the interaction between PNIPAM and PTPSS, PTPSS was forced out at the particle shell, forming reverse micelles [147]. TPEBT molecules were gradually revealed at the surface and deactivated the fluorescence emission due to energy dissipation. For a LCST system, heat-triggered hydrogen bond breaking between water and hydrophilic moieties could ultimately lead to the collapse of hydrophilic chains and disturb the intrinsic HLB, triggering the corresponding alterations in assembly level and ultimately macroscopic transformations.

Fig. 4.

(a) General structure of dye-conjugated PEG-b-PNIPAM (top panel) and fluorescence transition from polymeric ratiometric fluorescent thermometers upon heating and cooling (bottom panel) [145], Copyright 2015. Adapted with permission from the American Chemical Society. (b) Structure of PEG-b-P(NAGA-co-AN) (top panel), and UCST-type structural transformation that induced payload release (bottom panel) [154], Copyright 2018. Adapted with permission from John Wiley & Sons Inc.

While polymers with lower critical solution temperature (LCST) thermal behavior have been heavily investigated, those exhibiting upper critical solution temperature (UCST) property can also be used for nanomedicine [148]. While the low mobility of UCST polymers secure the payload stability at the temperature below UCST, the increased solubility of polymers upon heating could enable complete payload release [149]. Poly(N-acryloylglycinamide) was reported to show UCST with the transition temperature of 22–23 °C and a broad hysteresis upon cooling, but the effect of salt concentrations on cloud point limited the application [150,151]. Though poly(acrylamide-co-acrylonitrile) [P(AAm-co-AN)] showed tunable cloud point by varying the content of AN, the cloud point of P(AAm-co-AN) that increases with increasing concentration would also compromise the applicability [152]. Poly(N-acryloylglycinamide-co-acrylonitrile) [P(NAGA-co-AN)] showed the independence of polymer concentration and salt concentration on cloud point with narrow hysteresis while maintaining the tunability of cloud point [153]. The UCST polymer PEG-b-P(NAGA-co-AN) with cloud point of 44 °C was developed to ferry chemo-drug, doxorubicin (DOX), along with photothermal effect for spatiotemporal drug-resistant cancer treatment (Fig. 4b) [154]. PEG-b-P(NAGA-co-AN) can self-assemble into micelle with a size of 110 nm at room temperature while showing a drastic decrease in size of 7.2 nm upon heating over cloud point. The drastic changes in size upon heating enabled the delivery system to show burst drug release upon photothermal administration. However, compared to polymeric nanoparticles with LCST, nanoparticles that can dissipate at temperature above UCST remain underappreciated for biomedical applications due to the scarcity of polymers with suitable responsive temperature and biocompatibility. We have described prominent thermo-responsive polymers with LCST or UCST and provided examples of their transition between hydrophobic and hydrophilic states in response to temperature changes. For readers interested in delving further into this field, we recommend recently published in-depth reviews on the design and applications of these materials [26,27].

Oxidation-responsive polymers that exhibit triggered disintegration due to HLB change have also been explored in the past few years. Previous studies have focused on amphiphilic polymers that contain hydrophobic thioethers capable of being oxidized into sulfoxides and sulfones. Upon oxidation, these polymers increase in hydrophilicity, causing an interruption in HLB that leads to morphological transformation or disassembly. For example, oxidation-responsive block copolymer poly(ethylene glycol)-block-poly(2-(methylthio)ethyl glycidyl ether) (mPEG-b-PMTEGE) and random copolymer mPEG-r-PMTEGE were synthesized via anionic ring opening polymerization with molecular weights ranging from 5,600 to 12,000 g·mol−1 [155]. The amphiphilic copolymers with various copolymer compositions at different molecular weight can self-assemble into micelles with the size ranging 9.3 – 13.7 nm while unimers with the size from 2.3 – 2.6 nm were observed upon treatment with H2O2. Hydrophobic thioether upon treatment with diluted H2O2 were oxidized to sulfoxide after a few minutes and showed full conversion in 2.5 h at 310 K but 6 h in 296 K, increasing the dipole moment and solubility in aqueous solution. Hierarchical structure of poly(oligo(ethylene glycol) methyl ether methacrylate)-block-poly(2-(methylthio)ethyl methacrylate) (POEGMA-b-PMTEMA) nanoassemblies containing photocatalyst, tetraphenylporphine zinc, were obtained via polymerization-induced self-assembly process [156]. Upon light irradiation at 560 nm, the photosensitization of molecular oxygen by tetraphenylporphine into singlet oxygen oxidized the hydrophobic thioether to sulfoxide, rapidly leading to structural destruction. We note the growing interest in developing polymers that can sense oxidative stress and induce structural alterations by undergoing amphiphilic-to-hydrophilic transition for biomedical applications. We direct readers to recent reviews that offer in-depth discussions on the design rationale behind materials capable of responding to ROS in biomedical applications [157,158].

In addition to chemical stimuli, the interaction with biomolecules can perturb HLB and structural integrity of nano-assemblies. Noncovalent binding of protein to nano-assemblies was found to interrupts HLB and disassemble the polyelectrolyte assemblies via electrostatic interaction, leading to payload release for protein sensing [159,160]. The strategy was further applied to amphiphilic dendrimer assemblies that showed specific binding-induced disassembly [161,162]. The biotin ligand decorated on dendron periphery that was recognized by extravidin triggered hydrophilic-lipophilic imbalance, resulting in protein-induced disassembly and release of hydrophobic guests. The location of biotin was found to greatly influence the binding event as well as disassembly efficiency. The ligand placed at the focal point showed less accessibility to extravidin due to steric hindrance while ligand decorated on dendron periphery showed higher accessibility and efficient protein-induced disassembly. Similar strategy was exploited in the disease relevant binding pair of benzenesulfonamide and bovine carbonic anhydrase II (bCA-II) [163]. Biodegradable amphiphilic random polypeptide nano-assemblies with decoration of benzenesulfonamide at the surface underwent specific ligand-protein recognition in the presence of bCA-II, triggering the changes in size from 200 nm to 5 nm within 30 h. The protein-induced disassembly of amphiphilic dendrimer assemblies was exploited a protein concentration-dependent process as determined by ratiometric signal changes in fluorescence of monomer and excimer, where the coumarin moiety incorporated in hydrophobic core emitted excimer fluorescence while the monomer fluorescence was restored upon micellar disassembly [164]. Programmed disassembly in response to two-input AND logic gate was developed to endow selective and spatiotemporal control [165]. Masking the sulfonamide by photocage N-(o-nitrobenzyl) was able to inhibit the binding event between bCA and benzenesulfonamide at the surface of amphiphilic dendrimer nano-assemblies. Upon light treatment, benzenesulfonamide regained the binding affinity to bCA, initiating protein-induced disassembly. Compared to other stimuli-responsive systems, the binding interactions between ligands and proteins are generally very specific and binding affinities could be tuned via the structural modulation of ligands. Considering that the abnormally expressed proteins are important biomarkers for many diseases, this strategy is of great promise to be used for diagnosis and receptor-directed drug delivery.

3.2. Interruption of HLB via polymer fragmentation

3.2.1. Cleavage at hydrophobic-hydrophilic junction

Macromolecular nano-assemblies, composed of a hydrophilic block linked with a hydrophobic block by a trigger-degradable junction, can disintegrate upon stimulation. The bond breakage of a responsive linker could result in the cleavage of hydrophilic and hydrophobic polymer segments, further disrupting the HLB and generally leading to particle disruption in the form of precipitation. Herein, we discuss a few studies in which amphiphilic polymers with built-in responsive junctions that can sense physical, chemical, or biological triggers undergo an interruption in HLB and structural disintegration. Photocleavable group such as o-nitrobenzyl [166] and boron dipyrromethene [167,168] at the junction of hydrophilic and hydrophobic blocks have been developed for on-demand structural disintegration. The acid-labile ketal at the block junction of poly(ethylene oxide monomethyl ether) (MPEO)-b-poly ε-caprolactone) (PCL) that forms micellar nanoparticles showed accelerated hydrolysis of ketal groups at pH 5 compared to pH 7.4. Shedding of PEG chains increased the hydrophobicity, leading to disassembly and aggregation to facilitate the release of encapsulated paclitaxel (Fig. 5a) [169]. Similarly, shell-sheddable PCL and poly(oligo(ethylene glycol) monomethyl ether methacrylate) block copolymer with built-in disulfide bond at the block junction (PCL-SS-POEOMA) was developed by a combination of ring-opening polymerization and atom transfer radical polymerization (Fig. 5b) [170]. Shedding hydrophilic POEOMA corona of core-shell micelle with size of 30 nm, in response to reduction, in the presence of dithiothreitol (DTT), giving rise to the loss of colloidal stability and precipitation of PLA core. AB2 miktoarm block copolymers, poly(ethylene glycol)-b-poly(caprolactone)2 (PEG-b-PCL2), with built-in singlet oxygen (1O2)-labile β-aminoacrylate moiety at the junction were developed for photodynamically triggered drug release (Fig. 5c) [171]. Hydrophobic photosensitizer chlorin e6 (Ce6) encapsulated inside the hydrophobic PLA core can generate singlet oxygen (1O2) under light irradiation, which can induce the cleavage of β-aminoacrylate linkage. This bond cleavage led to the detachment of hydrophilic PEG, ultimately resulting in the dissociation of micellar structure. The cleavable joint of hydrophilic and hydrophobic block in response to enzyme can also initiate disruption of micellar nano-assembly. For example, the azobenzene linkage established at the junction of poly(ethylene glycol)-b-poly(styrene) (PEG-N=N-PS) amphiphilic copolymer has been shown cleavable in the presence of enzyme azoreductase along with coenzyme NADPH (Fig. 5d) [116]. The cleavage of azobenzene at the joint of hydrophilic poly(ethylene glycol) and hydrophobic poly(styrene) gives rise to micellar disruption and precipitation of PS segments. Moreover, responsive moieties built in between hydrophobic chains upon triggering can effectively shorten the hydrophobic chain length and disturb the HLB at which the macromolecules form stable nano-assemblies, leading to particle disassembly. For example, the cleavage of lipophilic units in response to esterase led to the disturbance of HLB amphiphilic dendrimer nano-assemblies, rendering the dendrimers hydrophilic and inducing the particle disassembly [118]. The accessibility of enzymes to cleavable moiety was found to affect the enzymatic response and disassembly kinetics [172,173]. The degree of polymerization and HLB of amphiphilic oligomers can alter the unimer–aggregate equilibrium to tune the accessibility of enzyme to responsive moieties, resulting in tunable disassembling kinetics and controlled payload release [120]. These responsive amphiphilic copolymers are widely applied in the nano-formulation of hydrophobic drugs for drug delivery. The cleavage of hydrophilic and hydrophobic polymer segments in response to breakage of triggerable junctions can result in particle disruption and the release of encapsulated drugs. Nonetheless, the structural disintegration of nano-assemblies in the form of precipitation of hydrophobic segments likely traps a portion of drugs in precipitates, hampering the drug release. Therefore, a thorough assessment of the drug release profile of nanoparticles falling within this category would be imperative to tailor their suitability in real-world applications.

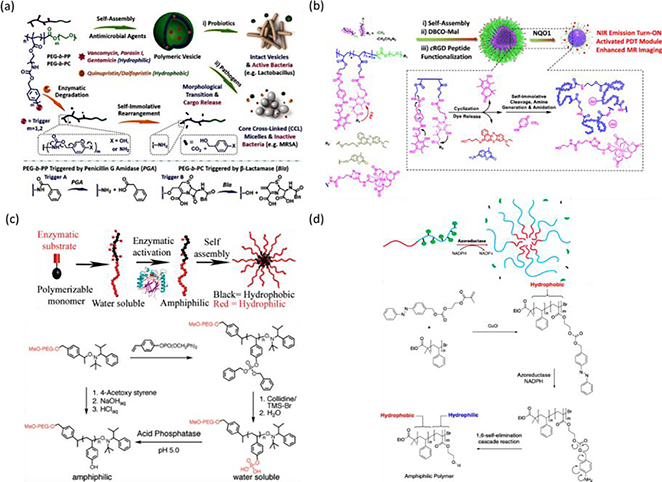

Fig. 5.

Cleavage at hydrophobic and hydrophilic junction led to the disruption of nanoparticles in a form of precipitation. (a) Chemical structure of the acid-labile block copolymer MPEO44-b-PCL17 (top panel) and the schematic illustration of assembly/disassembly transition of nanoparticles at pH ~5.0 (bottom panel) [169], Copyright 2021. Adapted with permission from the authors. (b) Illustration of particle disruption of PCL-SS-POEOMA micelles in response to DTT (top panel) and chemical structure of the reduction-responsive block copolymer PCL-SS-POEOMA (bottom panel) [170], Copyright 2015. Adapted with permission from the American Chemical Society. (c) Schematic illustration of amphiphilic miktoarm PEG-b-PCL2 copolymer with a junction of 1O2-Labile β-aminoacrylate (top panel), and their self-assembly and particle disruption 1O2-mediated dissociation upon red-laser (bottom panel) [171], Copyright 2018. Adapted with permission from the American Chemical Society. (d) Schematic representation (top panel) and a digital picture (right panel) of the micellar assembly from PEG-N=N-PS block copolymer and triggered disruption into PEG and PS homopolymers by the enzyme azoreductase in the presence of NADPH. Chemical structure of the acid-labile block copolymer PEG-N=N-PS (bottom panel) [116], Copyright 2018. Adapted with permission from the American Chemical Society.

3.2.2. Cleavage of sidechains

In addition to the bond breakage at the junction of the hydrophobic and hydrophilic block, the interruption of HLB through the cleavage of sidechains on macromolecules has been extensively studied for responsive structural alterations. In this section, we focus on previous studies that investigated the particle disruption of amphiphilic polymers due to cleavage of hydrophobic pendants upon exposure to physical, chemical, or biological stimuli, leading to structural transformation. The cleavage of bonds between the polymer backbone and hydrophobic pendants can cause the polymer backbone to become hydrophilic, resulting in the disruption of HLB and subsequent changes in the nano-assemblies. For instance, the photo-solvolysis of 1-pyrenylmethyl esters under UV irradiation, leaves carboxylic acids on the substrate [174]. Amphiphilic copolymers consisting of hydrophobic, photocleavable groups rapidly became a mainstream fashion to construct nano-assembly with triggerable degradation [28,175,176]. The bond cleavage of hydrophobic, photocleavable groups, such as pyrene [29], o-nitrobenzyl [30], coumarin [46] and perylene [32] at ultraviolet region, and [Ru(tpy)(biq)(H2O)]2+ tpy = 2,2′:6′,2″-terpyridine and biq = 2,2′-biquinoline) [177,178] at visible wavelength, on amphiphilic polymers induces the transformation from hydrophobicity to hydrophilicity, leading to HLB and the disruption of nano-assembly. Photoresponsive therapeutic delivery based on photocleavage has been significantly developed for precision medicine due to its spatiotemporal precision [33,34]. The use of light in delivery systems enables particles to release payloads at the site of interest on demand and reduces off-target effects [33,34,179–182]. While photoactivation provides high precision in therapeutic delivery, the development of photo-controlled therapeutics is still hampered by issues such as phototoxicity, shallow depth of light penetration, and uncertain timing of the triggering event. Recently, the development of two-photon triggering system [31,183] and photo-upconversion mechanism [184–187] assuage the concerns above mentioned, but further exploration in this field is still necessary for practical applications.

In comparison with photoactivation, ultrasound offers similar spatiotemporal precision but a controlled depth of penetration and the availability of image-guided triggering systems. The availability of advanced medical instruments and systemic administration has made it possible to introduce ultrasound-triggered systems in clinical practice [68,69]. Amphiphilic copolymers composed of water-soluble poly(ethylene oxide) (PEO) block and hydrophobic poly(2-(2-methoxyethoxy)ethyl methacrylate) (PMEO2MA) scrambled with poly(2-tetrahydropyranyl methacrylate) (PTHPMA) was developed, which could self-assemble into micelles with core of PMEO2MA and PTHPMA and PEO corona in water at temperatures above its LCST [70]. HIFU irradiation induced the hydrolysis of THPMA and left hydrophilic methacrylic acid on the polymer backbones, resulting elevated LCST of existing micelles that led to the disruption of particle and payload release (Nile red) at the same temperature. Recently, we introduced PTHPMA into fluoropolymer hydrogels for enhanced 19F MRI imaging [188], which would be potentially a theragnostic delivery system via MRI-guided focused ultrasound. Remarkably, the mechanochemistry area has burst over the past decade [189,190], which brings various new chemistries with distinct responsive properties. Considering the spatiotemporal precision and noninvasiveness of ultrasound as a stimulus, we believe more and more mechanical force-responsive moieties would be introduced into amphiphilic macromolecules and assemblies in the coming decades and bring opportunities in more applications.

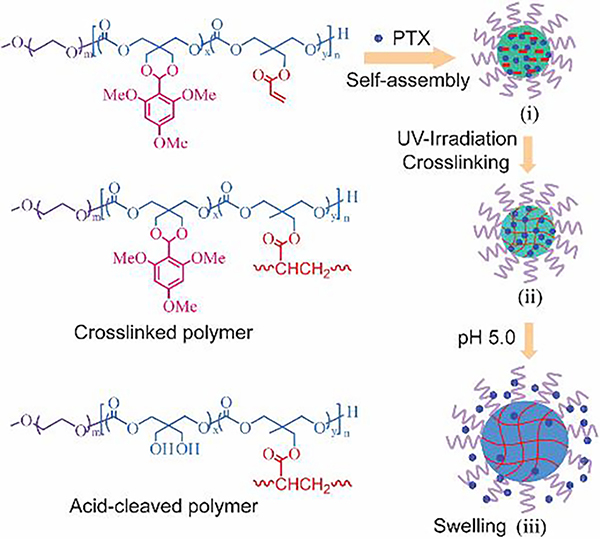

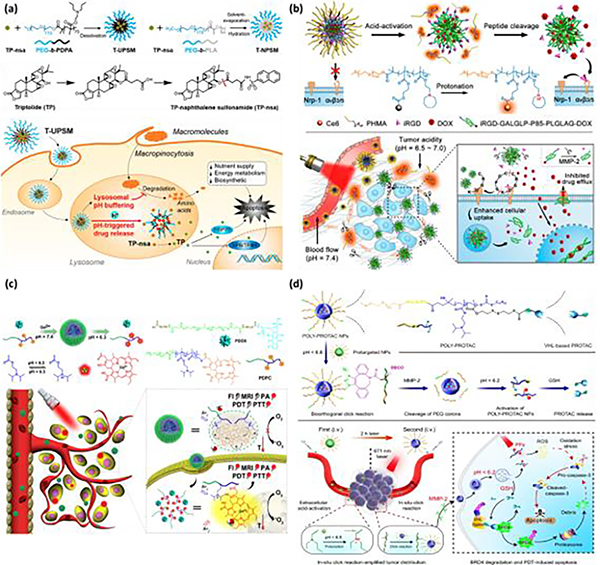

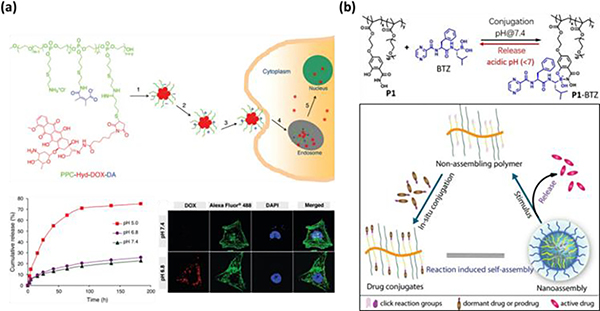

Amphiphilic copolymers with acid-labile bonds linking hydrophobic side chains have gained significant attention due to their stable colloidal properties under physiological conditions and their ability to undergo hydrolysis at low pH. These copolymers are especially useful in environments with lower pH levels, such as the tumor microenvironment (pH 7.2–6.8), endosomes (pH 6.8–6.0), and lysosomes (pH < 5) [191–193]. The distinctive lower pH environment provides a niche for pH-responsive polymer materials to serve as delivery systems for cancer treatment. At lower pH, hydrophobic pH-labile groups, which may include drugs or chemical functional groups, undergo hydrolysis, leading to a hydrophilic-lipophilic imbalance and eventual disruption. A majority of acid-labile linkers, such as hydrazone, imine, acetal/ketal, ortho ester, maleic acid amide (MAA), and β-thiopropionate functional groups have been developed and utilized in pH-responsive delivery systems [73,194]. For example, corecrosslinked polymeric micelles (CCPMs) formed by micellization of acid-triggered native active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) in methoxy poly(ethylene glycol)-b-poly[N-(2-hydroxypropyl) methacrylamide-lactate]) (mPEG-b-pHPMAmLacn) followed by covalently crosslinking via free radical polymerization. Acid-labile trityl-based linkers is vulnerable at pH 5.0 or 6.5 but relatively stable at pH 7.4 [195,196]. With variation of substituents on acid-labile trityl linkers, model API compounds such as DMXAA-amine, DOX, and gemcitabine conjugated on CCPMs showed the tunability of trityl degradation as well as drug release in different pH milieu.

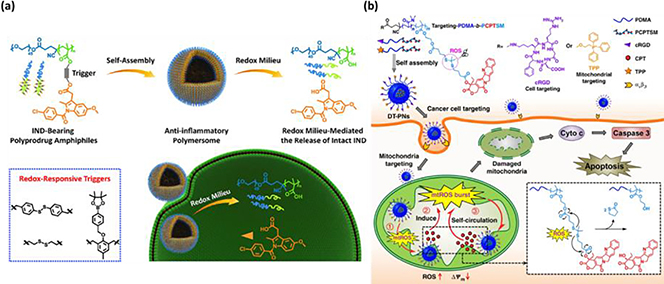

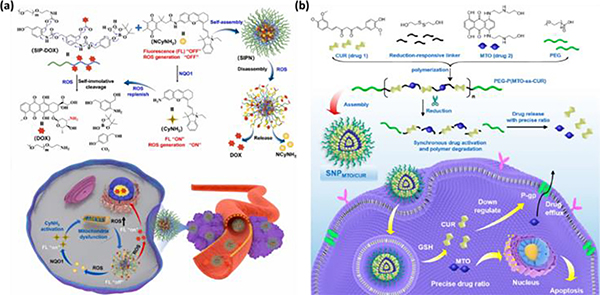

Reactive oxygen species, including hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), superoxide (O2•−), hydroxyl radical •OH), peroxynitrite ONOO−), and hypochlorite OCl−), are known to induce oxidative stress and can be used as triggers for oxidation-responsive or ROS-responsive materials [86,197]. For example, boronic acids/esters such as phenylboronic acid (PBA) are sensitive to ROS. Amphiphilic copolymer bearing hydrophobic PBA pendants from post-polymerization modification of methoxy poly(ethylene glycol)-b-poly[(N-2-hydroxyethyl)-aspartamide] (mPEG113-b-PHEA21) was used to encapsulate chemo-drugs, such as DOX, camptothecin (CPT), epirubicin, and irinotecan via nanoprecipitation and donor–acceptor coordination, self-assembling into drug-loaded micelles [198]. With treatment of hydrogen peroxide, arylboronic ester of PBA was oxidized and cut from polymer side chain after rearrangement to recover hydrophilic nature of mPEG113-b-PHEA21. Apart from boronic ester as a ROS-induced cleavable bond, thioketal bond is susceptible to ROS, forming free thiol alone with acetone as a byproduct [85,199,200]. Amphiphilic block copolymer composed of hydrophilic poly(N,N-dimethylacrylamide) (PDMA) and hydrophobic polyprodrug of ROS-cleavable thioketal-linked CPTs (PDMA-b-PCPTSM) self-assembled into intact micelles with size of 55 nm for responsive cancer treatment [201]. In response to high level of oxidative stress, cleavage of thioketal linkers liberated CPT molecules and restored hydrophilic poly(2-hydroxyethyl methacrylate) after self-immolative cyclization, inducing the particle deconstruction. With a similar strategy, reduction-responsive PEG-b-PCPTM polyprodrug amphiphiles with various repeating units of PCPTM self-assemble into four types of hierarchical nanostructures, including spheres, flower-like large compound vesicles, smooth disks, and staggered lamellae [202]. In response to the highly cytosolic GSH concentration (10 mM), disulfide bonds between the polymer backbone and CPT can be reduced to free thiols, which further undergo cyclization to release CPT in a traceless fashion. In particular, PEG-b-PCPTM nano-assemblies showed shape-modulated drug release kinetics, cellular internalization pathways, degradation rate, and therapeutic efficacy. Cleavage of sidechains of amphiphilic macromolecules in response to enzymes can result in the compromising of HLB and disruption of nano-assemblies. Polymersomes are composed of a hydrophilic poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG) block and a hydrophobic block containing enzyme-cleavable self-immolative side linkages and enzyme-cleavable end-caps. Upon treatment with penicillin G amidase and β-lactamase, recovery of the capping amine or hydroxyl group can undergo cascade self-immolation to initiate particle disruption and morphology transformation, leading to subsequent drug release (Fig. 6a) [203]. Similar strategy was also applied to NAD(P)H: quinone oxidoreductase isozyme 1 (NQO1)-responsive micelles for enhanced magnetic resonance (MR) imaging and fluorescence-guided photodynamic therapy (Fig. 6b) [204].

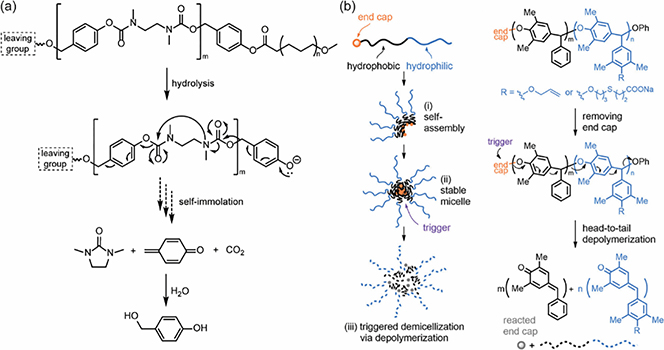

Fig. 6.

(a) Enzyme-responsive polymeric vesicles for bacterial strain-selective delivery of antibiotics and structural transformation in response to enzyme (top panel). Illustration of bond cleavage of built-in triggers in response to penicillin G amidase, and β-lactamase (bottom panel) [203], Copyright 2016. Adapted with permission from John Wiley & Sons Inc. (b) Self-assembly of amphiphilic BCPs containing quinone trimethyl lock-capped self-immolative side linkages and triggered particle transformation under exposure to NQO1 [204], Copyright 2020. Adapted with permission from the American Chemical Society. (c) The illustration of enzyme-induced self-assembly from hydrophilic block copolymer (top panel) and synthetic approach for the preparation of amphiphilic diblock copolymers (bottom panel) [117], Copyright 2009. Adapted with permission from the American Chemical Society. (d) Schematic illustration of enzyme-induced self-assembly from hydrophobic block copolymers (top panel). Synthesis of hydrophobic precursor of block copolymer, and hydrophobic-to-amphiphilic transition behind the enzyme-induced particle formation (bottom panel) [205], Copyright 2014. Adapted with permission from the American Chemical Society.

Enzyme-responsiveness has been applied not only to induce structural disintegration but also to trigger assembly. Hydrophilic block copolymers composed of a monomethyl ether 5 kDa PEG and 4-vinylphenyl phosphate can respond to acid phosphatase to cleave phosphate moieties and convert into amphiphilic copolymers, triggering self-assembly to form colloidal nanostructures in situ (Fig. 6c) [117]. In a similar fashion, enzyme treatment induced self-assembly behavior to form hydrophobicity-driven micelles with a hydrophobic block copolymer of styrene and hydroxyl methacrylate caged with a hydrophobic, enzyme-sensitive azobenzene (Fig. 6d) [205]. Upon the exposure to azoreductase in the presence of coenzyme NADPH, enzymatic cleavage of the azobenzene linkage triggers a spontaneous elimination reaction to form a hydrophilic hydroxyethyl methacrylate, resulting in amphiphilic block copolymers and subsequent self-assemblies. The breakage of covalent bond in response to triggers has shown the interference of HLB to manipulate the transformation of nanostructures.

4. Stimuli-triggered depolymerization

Nano-assemblies generally form via a variety of covalent and noncovalent interactions, which work synergistically to retain their fidelity. The interactions typically originated from different moieties on polymer chains in multivalent manner; thus, polymer integrity is crucial for maintaining the stability of assemblies. Stimuli-triggered macromolecular fragmentation could break the multivalent interactions, leading to nanostructure disassembly. Therefore, depolymerization is an important strategy to trigger assembly alterations, which could be in cascade (chain unzipping) or parallel (chain scission) manners, depending on the chemistry exploited in molecular design. Stimuli-triggered stepwise or simultaneous cleavage of chemical bonds on macromolecular backbones typically leads to particle disassembly and corresponding macroscopic transformations, which would be summarized in this section.

4.1. Stimuli-triggered chain unzipping

Cascade degradation method has long been studied for stimuli-triggered molecular amplification, with potential applications in sensing, imaging, and drug delivery. Some commonly used cascade degradation chemistry includes bond breakage by electronic cascade over an aromatic structure or cyclization-induced cleavages. Among these chemistries, (aza)quinone methide precursor [206], first proposed as self-immolative connector to design prodrugs [207], have grown to be one of the most widely used degradable moieties for bioconjugation [208], design of chemical probes [209], dendrimers [210], and polymers [37,211] to realize cascade and controllable fragment release from molecular skeletons [212]. As different functional groups can be incorporated into the structures, cascade degradations can be triggered using a variety of stimuli [213].

Recently, this chemistry has been employed for the design of amphiphilic macromolecules to fabricate nano-assemblies, utilizing the stimuli-triggerable fragmentation feature for the design of responsive nanostructures, expanding the responsiveness from single molecules to nanostructures and eventually generating macroscopic phenomenon [210,216]. In 2009, an amphiphilic PEG-polycarbamate block copolymer was synthesized, which underwent degradation via an alternating electronic cascade 1,6-elimination and cyclization mechanism (Fig. 7a) [214]. The polymer could form assemblies and encapsulate Nile red as the cargo which was released after a cascade polymer degradation. Despite that the initiation of cascade degradation relies on the spontaneous hydrolysis of an ester linkage between PEG and polycarbamate blocks, it brought a new strategy for the design of stimuli-responsive amphiphilic polymers with (aza)quinone methide precursors. Since then, various stimuli-responsive groups have been functionalized as the caps of polymers for substrate sensing/imaging, triggerable cargo release and other applications. For example, DOTA-Gd and fluorine-rich sidechainstethered amphiphilic polymers were functionalized with acid-sensitive imine and ROS-responsive boronic acid and were fabricated to micellar nanoparticles [216]. Stimuli-triggered polymer fragmentation and particle disassembly at tumor region led to the release of highly reactive (aza)quinone methide-based intermediates which can be trapped by intracellular thiol-relevant substrates and turn on the theragnostic signals for imaging. The utilization of these quinone methide intermediates brings a new sight for the bio-applications of these polymers as the intermediates are generally considered to be toxic and bio-incompatible. Similar strategies have also been reported for quinone methide-based linkers for protein modifications and drug discovery [217,218]. However, due to the triggerable degradation requirements, quinone methide-based polymers are generally synthesized via polycondensations or additions to afford rigid and hydrophobic backbones with limited number of repeating units. To achieve amphiphilicity, the hydrophilic moieties could be installed either as separate blocks or as sidechains on repeating units. If they were modified as sidechains, monomers would possess at least three functional groups (two for polymerization and one as the hydrophilic moiety), which may need tedious synthetic processes.

Fig. 7.

(a) Self-Immolation of polymers via an alternating alternating electronic cascade 1,6-elimination and cyclization mechanism [214]. (b) Poly(benzylether)-based self-immolative polymer for the design of stimuli-responsive assemblies [215], Copyright 2022. Adapted with permission from the American Chemical Society.

Apart from polycarbonates or polycarbamates, substituted poly(benzylether) were recently designed which could depolymerize via similar degradation mechanisms [211,212]. These amphiphilic polymers can be synthesized by tethering hydrophilic moieties on these polymer chains. The formed micellar nano-assemblies could degrade via a head-to-tail depolymerization and release the encapsulated hydrophobic guest molecules (Fig. 7b) [208]. It should be noted that for degradable poly(benzylether) mentioned above, the leaving group is a phenolic moiety which is quite different from the generally used carbonates and carbamates. Actually, although most quinone methide-based polymers shared similar depolymerization mechanisms, the degradation kinetics could be significantly affected by polymer structures and the accessibility of stimuli in different assemblies. In 2020, our group reported the assembly of alkaline phosphatase (ALP) responsive self-immolative polymers by complexing with charged polyelectrolyte or via an oil-in-water emulsion methodology to form spherical nanoparticles (Fig. 8a) [130]. Interestingly, the two types of particles exhibited very distinct disassembly kinetics, likely due to the different accessibility of ALP to the phosphate caps of polymers. In another study, we found that carboxylate functionalized p-amino-cinnamyl alcohol fabricated self-immolative polymers could undergo both stimuli-triggered chain unzipping and nucleophile-induced chain scission [222]. Depolymerization can be programmed exclusively via either of the two pathways with distinct kinetics by a judicial selection of functional groups and triggers. These fundamental studies motivated us to utilize this chemistry to design stimuli-triggerable soft matters. We formulated vesicle-like morphology nanoparticles by complexing carboxylic acid functionalized polymers with positive charged poly(diallyl)-dimethylammonium chloride, which can encapsulate enzyme in the hydrophilic core [223]. After particle destruction via photoinduced chain unzipping, the encapsulated enzyme was released and catalyzed the construction of hydrogel via the crosslinking of tyrosine-based substrates. Previous studies have demonstrated that the degradation kinetics could be affected by leaving groups and their substitution position (ortho or para), responsive moieties and stimuli, microenvironment (solvent, pH, etc.), aggregation state and accessibility of triggers [212].

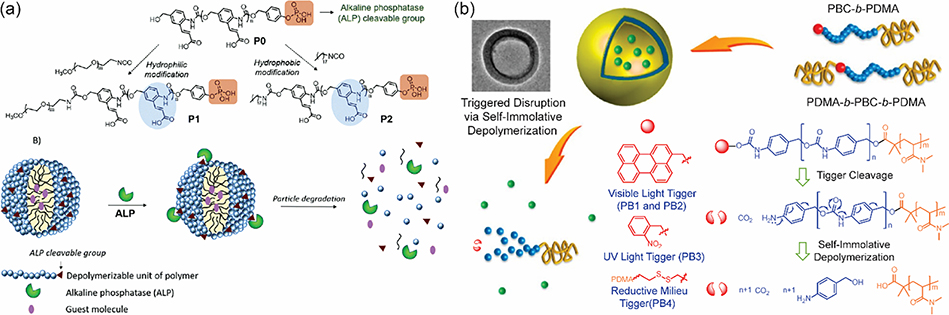

Fig. 8.

(a) ALP-responsive self-immolative nano-assemblies [130], Copyright 2020. Adapted with permission from the Royal Society of Chemistry. (b) Self-Immolative Polymersomes from poly(benzylcabomate)-PDMA block copolymers [54], Copyright 2014. Adapted with permission from the American Chemical Society.

Precise control of stimuli-triggered responsiveness is highly demanded in the applications of smart soft materials. To achieve the controllability, dual or multiple triggers have been installed into polymer skeletons via (aza)quinone methide-based degradation mechanisms for programmable responsiveness. For instance, [224]programmable microcapsules were prepared using self-immolative polymers functionalized with different triggerable moieties [225]. An exposure to specific stimulus can trigger the rupture of microcapsules and release of core contents. Sophisticated block copolymers were later designed by incorporating self-immolative polymer blocks with a hydrophilic poly(N,N-dimethylacrylamide) (PDMA) block (Fig. 8b) [54]. These amphiphilic polymers self-assembled into polymersomes with different sizes from 205 nm to 580 nm, depending on polymer topologies and architectures. The assemblies were applied for the co-encapsulation of both hydrophobic and hydrophilic drugs which were efficiently released after treatment with a reductive milieu trigger, glutathione. These polymersomes can be functionalized with various responsive moieties and used for the design of AND, OR and XOR logic gate-type reaction system on the basis of different stimuli. This system provides an excellent example for the control of enzymatic reactions using amphiphilic nano-assemblies by the precise modulation of multiple stimuli. However, the introduction of multiple responsive moieties could obviously bring complexity for polymer synthesis and particle formulations. Additionally, although not investigated, the generated quinone methide intermediates may be trapped by the nucleophiles on enzymes in the system and diminish the enzymatic activity.

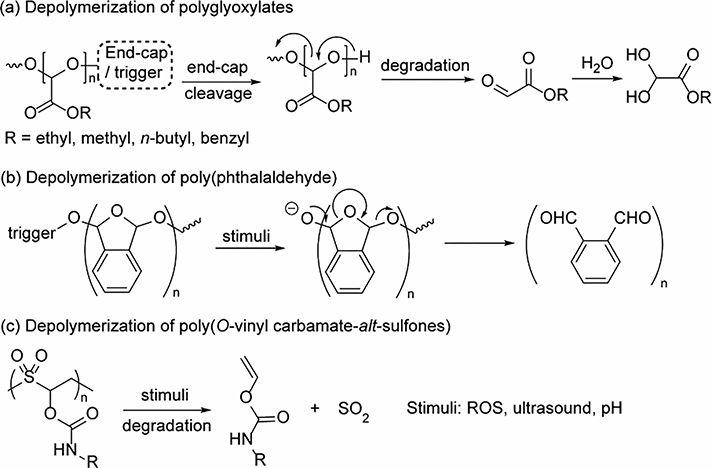

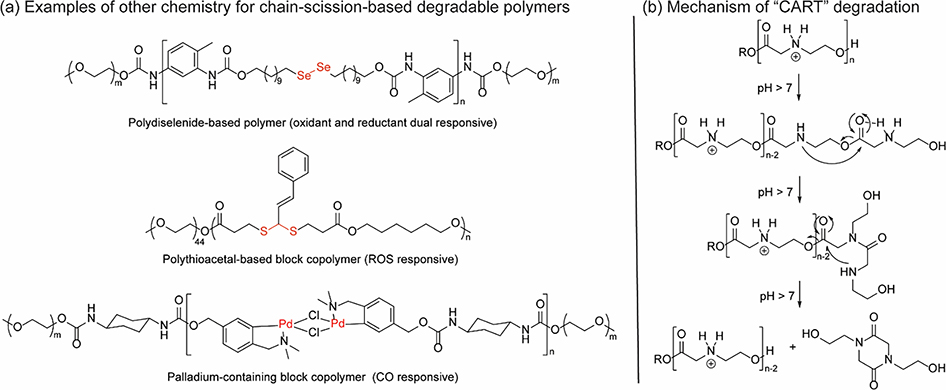

Over the past decades, many other chemistries have been developed as alternative moieties for the design of unzippable polymers. Recently, stimuli-responsive functional groups have been installed into polyglyoxylates, a type of self-immolative polymers which depolymerize in an end-to-end manner to corresponding glyoxylates, and ultimately to alcohols and glyoxylic acid hydrate (Fig. 9a) [226]. The responsive moieties can be functionalized on either side of the linear polymers symmetrically or non-symmetrically, generating homo- and copolymers on the basis of different synthetic strategies [229–231]. Notably, polyglyoxylates can be further modified via an amidation reaction to polyglyoxylamides which exhibited very different physical and chemical properties, including degradative properties [232]. Amphiphilic polyglyoxylates and polyglyoxylamides have been used to prepare nanoparticles and their responsiveness can be tuned by manipulating polymer structures or simply blending two different polymers [229,233]. Poly(phthalaldehyde) (PPA) is another type of well-studied self-immolative polymers [234,235]. Since 2010, stimuli-responsive end caps have been introduced to these polymers, opening up new avenues for the design of triggerable self-immolative PPAs (Fig. 9b) [227]. After exposure to specific stimuli, the PPAs could decompose rapidly to corresponding phthalaldehyde and lead to macroscopic changes. Over the past years, different synthetic methods have been employed for the design of PPA-involved random [236] and block copolymers [237,238]. PEG-tethered amphiphilic PPAs has been formulated to polymeric capsules and encapsulate fluorescein isothiocyanate labeled dextran [239]. The capsules disassembled after fluoride-triggered depolymerization and released the encapsulated guest molecules with tunable kinetics depending on the polymer length and thickness of shell wall. Recently, poly(o-vinyl carbamate-alt-sulfones) were used to formulate nanoparticles with 185 nm size for the encapsulation of guest molecules (Fig. 9c) [228]. These particles are sensitive to pH and ROS, which exhibit different degradation and guest release kinetics under different stimuli. The emergence of new chemistry for amphiphilic macromolecules has brought alternative strategies for the design of stimuli-responsive soft maters with distinct responsive properties. However, the generation of aldehyde intermediates, limited polymer stability and complexity in polymer functionalization are still not satisfactory for many applications, especially in biological areas. Thus, it would be important to explore more synthetic chemistries and degradation mechanisms for responsive macromolecules.

Fig. 9.

Depolymerization of (a) polyglyoxylates [226], (b) poly(phthalaldehyde) [227], and (c) poly(O-vinyl carbamate-alt-sulfones) [228].

4.2. Stimuli-triggered chain scission

Apart from chain unzipping, another depolymerization strategy is stimuli-triggered chain scission. Other than a head-to-tail type degradation in chain unzipping, chain scission happens parallelly for multiple bonds on polymer backbones, independent of each other. This strategy relies on the activation of multiple responsive groups, thus is concentration dependent. Some widely used chemistry includes polydisulfides, poly(aza)quinone methide precursors, and stimuli-triggered cyclable moieties. These amphiphilic polymers have been applied to formulate nanoparticles for diverse applications. Similar to chain unzipping, stimuli-triggered chain scission also leads to polymer fragmentation and ultimately the disruption of nanoparticles.

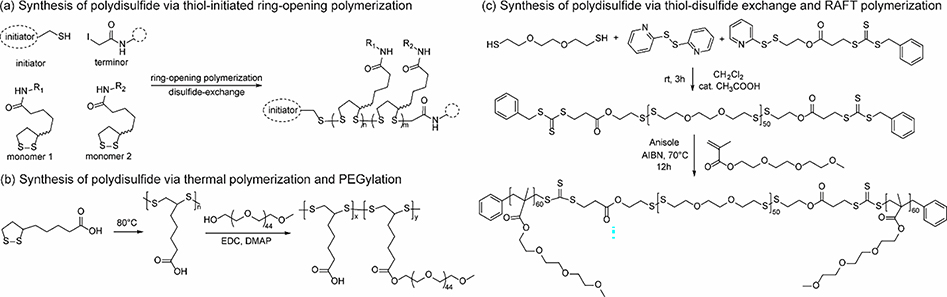

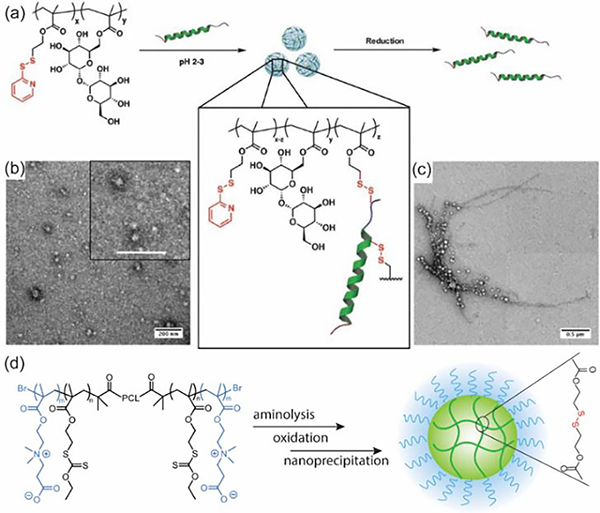

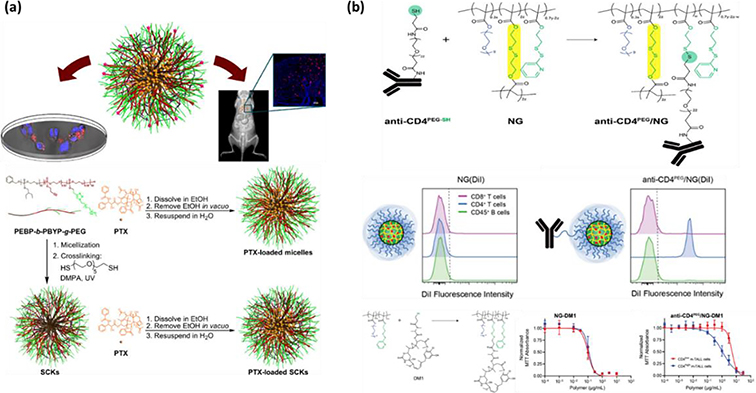

Polydisulfides are polymers with disulfide repeating units on their backbones, which are dynamic and cleavable in response to various stimuli, such as redox, light, and mechanical force [240,241]. Several strategies have been developed for the synthesis of polydisulfides, including ring-opening polymerization of cyclic disulfides, oxidative polymerization of dithiols, thiol-disulfide exchange, and poly-conjugation of monomers with disulfide moieties (disulfides unchanged) [93,240–244]. Recently, substrate-modified cell-penetrating polydisulfides (CPDs) were synthesized via ring-opening disulfide exchange polymerizations (Fig. 10a) [245]. Synthesized polydisulfides were found to penetrate cell membranes rapidly either via endocytosis or direct translocation avoiding endosomal entrapment, depending on polymer structures. Depolymerization could happen within 1 min after reaching cytosol due to the presence of high concentration of GSH. The authors proposed that the direct translocation of polymers across cell membranes was attributed to a combination effect of counterion-mediated and thiol-mediated translocation mechanisms. This study opens a new sight for intracellular delivery of drugs and biomacromolecules, as endosome escape is always a challenging issue in this area [246,247]. Apart from thiol-initiated disulfide-exchange polymerization, polydisulfides can also be afforded by thermal polymerization (Fig. 10b) [248]. The PEGylated amphiphilic polymers self-assembled in water and encapsulated anticancer drug DOX, forming 48 ± 8 nm size spherical nanoparticles. Owing to the disulfide-based backbones and carboxylic acid residues on sidechains, these particles exhibited pH and redox responsive behaviors due to stimuli-triggered charge conversion and polymer fragmentation. Although this work provides a simple method for the synthesis of polydisulfides, the precise control of molecular weight and distribution is challenging.

Fig. 10.

Synthesis of polydisulfide-based random and block copolymers via (a) thiol-initiated ring-opening polymerization [245], (b) thermal polymerization [248], and (c) thiol-disulfide exchange and RAFT polymerization [249].

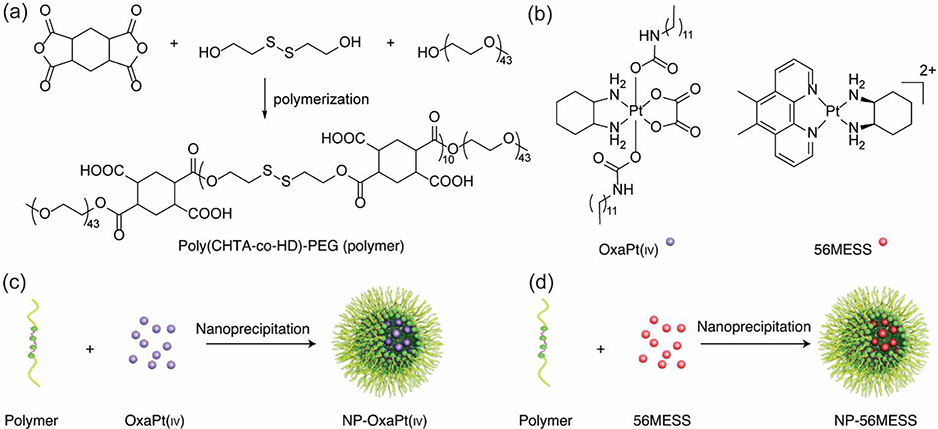

Apart from random copolymers, disulfide-containing block copolymers were also designed for the fabrication of stimuli-responsive nano-assemblies. These polymers could be afforded via different synthetic strategies, including RAFT polymerization (Fig. 10c) [249,250], atom transfer radical polymerization [92,251], and polycondensation. For instance, amphiphilic triblock copolymer poly(1,2,4,5-cyclohexanetetracarboxylic dianhydride-co-hydroxyethyl disulfide)-polyethylene glycol (poly (CHTA-co-HD)-PEG) was recently synthesized via the polycondensation reaction of dianhydride, diol and polyethylene glycol (Fig. 11a) [252]. The polymer was used to formulate spherical nanoparticles by nanoprecipitation, which possessed disulfide linkages and negatively charged carboxylic acid functional groups. These particles could be used to encapsulate a hydrophobic anticancer drug oxaliplatin via hydrophobic interactions and a cationic DNA intercalator 56MESS via electrostatic interactions (Fig. 11b, c & d), which can be released in a reductive tumor environment. Similar investigations have also been performed recently by many other groups, elucidating the great potential of polydisulfides in delivery and their advantages over other materials [253–255]. The well-developed synthetic methods, structure diversity and their responsive degradation toward biological stimuli has made polydisulfide-based amphiphilic macromolecules especially appealing in the design of smart drug delivery systems.

Fig. 11.

(a) Synthesis of poly (CHTA-co-HD)-PEG. (b) Structures of OxaPt(IV) and 56MESS. (c) Formation of NP-OxaPt(IV), and (d) NP-56MESS via nanoprecipitation [252], Copyright 2021. Adapted with permission from the Nature Publishing Group.