Abstract

Background:

Substance use (SU) contributes to poor outcomes among persons living with HIV. Women living with HIV (WWH) in the United States are disproportionately affected in the South, and examining SU patterns, treatment, and HIV outcomes in this population is integral to addressing HIV and SU disparities.

Methods:

WWH and comparable women without HIV (WWOH) who enrolled 2013–2015 in the Women's Interagency HIV Study Southern sites (Atlanta, Birmingham/Jackson, Chapel Hill, and Miami) and reported SU (self-reported nonmedical use of drugs) in the past year were included. SU and treatment were described annually from enrollment to the end of follow-up. HIV outcomes were compared by SU treatment engagement.

Results:

At enrollment, among 840 women (608 WWH, 232 WWOH), 18% (n = 155) reported SU in the past year (16% WWH, 24% WWOH); 25% (n = 38) of whom reported SU treatment. Over time, 30%, 21%, and 18% reported SU treatment at 1, 2, and 3 years, respectively, which did not significantly differ by HIV status. Retention in HIV care did not differ by SU treatment. Viral suppression was significantly higher in women who reported SU treatment only at enrollment (P = 0.03).

Conclusions:

We identified a substantial gap in SU treatment engagement, with only a quarter reporting treatment utilization, which persisted over time. SU treatment engagement was associated with viral suppression at enrollment but not at other time points or with retention in HIV care. These findings can identify gaps and guide future strategies for integrating HIV and SU care for WWH.

Key Words: HIV, substance use, care continuum, women's health, public health, epidemiology

INTRODUCTION

The HIV and substance use (SU) epidemics are deeply intertwined in the United States; it is well-established that people with HIV who engage in SU experience barriers to care, leading to lower retention, poor viral suppression, and other gaps along the HIV care continuum.1–4 SU contributes to HIV acquisition through injection drug use and particularly among cisgender women, through sexual routes due to challenges, such as impaired ability to negotiate with partners.3,5 The epicenter of the HIV epidemic is in the South, which faces the highest burden of HIV compared with other regions of the country.6 Similarly, higher rates of substance use disorder (SUD) and gaps in capacity for SUD treatment have been identified in the Southeast United States.7–9 Women comprise 20% of the 40,000 annual new diagnoses in the United States and are disproportionately affected in the South.10,11 Therefore, implementing strategies to improve gaps in the continuum and treatment access for both HIV and SU for women in the South is crucial to end the syndemic.

Evidence-based interventions for SUD12,13 have been shown to facilitate antiretroviral therapy (ART) initiation, uptake, and possibly viral suppression.14–16 However, the implementation gaps in these interventions among women living with HIV (WWH), particularly in the South, are unknown, due in part to underrepresentation of women in HIV research and limited sex disaggregated data. A SU care continuum, in conjunction with the HIV care continuum, would be useful to identify critical gaps in care from prevention to recovery and implement solutions to address such gaps.17,18 Unfortunately, data to populate such a tool are lacking for WWH.

We describe SU treatment utilization and HIV care outcomes over time among WWH and comparable women without HIV (WWOH) across the Southern United States. Through characterizing SU, SU treatment, and HIV outcomes over time in this understudied population, we seek to provide a foundation for an integrated SU and HIV care continuum to guide future care strategies.

METHODS

Study Population

The Women's Interagency HIV Study (WIHS) is a large, prospective cohort study of WWH and demographically similar cisgender WWOH across 10 US sites.19 Four sites (Atlanta, Birmingham/Jackson, Chapel Hill, and Miami) in the South were added between October 2013 and March 2015 given the growing epidemic in this region. Additional details on eligibility criteria and recruitment methods have been published previously.19 To provide contemporary data on SU, we included women enrolled in the WIHS Southern sites from 2013 to 2015 and followed over time in this analysis. Participants who transferred from non-Southern sites were excluded. Participants had study visits every 6 months with standardized interviews, physical examinations, and biospecimen collection.19 All WIHS participants provided written informed consent for study participation. The WIHS protocol20 was approved by each site's Institutional Review Board.

Measures

SU was defined as self-reported nonmedical use of drugs in the past year, including crack/cocaine, methamphetamines, and nonprescription opioids such as heroin; the use of tobacco, alcohol, or marijuana alone was not included in this definition, consistent with prior literature.21–23 SU frequency by drug type in the past 6 months was classified based on self-report (none, monthly, weekly, daily). SU treatment was defined as self-reported use of medications for opioid use disorder (obtained through prescription or self-treatment by the individual) or attendance at drug treatment programs in the past year. Drug treatment programs included inpatient and outpatient detoxification programs, halfway houses, buprenorphine/methadone maintenance programs, justice system-based programs, and Narcotics Anonymous. Polysubstance use was defined as use of more than 1 category of drugs (crack/cocaine, opioids, and methamphetamine). Depressive symptoms were defined as a Center for Epidemiologic Studies-Depression score ≥ 16.24 Retention in HIV care was defined as a self-reported attendance of an HIV care visit within the past 6 months, and viral suppression was defined as a study viral load <200 copies/mL.19

Analysis

Demographic, clinical, and sociobehavioral characteristics were summarized for women who reported SU in the past year at enrollment. Within this population, SU and SU treatment were determined at enrollment, 1, 2, and 3 years; overall and stratified by HIV serostatus; and compared using χ2, Fisher exact test, or Wilcoxon signed-rank test, where appropriate. Although standardized definitions for retention in SU care do not exist, year-long intervals were chosen as these periods of time were more appropriate for conceptualizing clinically relevant SU treatment engagement over time.25,26 Study visits closest to the specified year were included. Regarding HIV care outcomes, HIV care visits and viral loads in the past 6 months were determined at enrollment and subsequent time points, which were stratified by SU treatment status and compared using χ2 and Fisher exact tests, where appropriate. Missing viral load and interview data were infrequent (≤5% of the data) and were excluded from analysis.

RESULTS

Demographic Characteristics

Regarding overall Southern site cohort characteristics, of 840 women (608 WWH, 232 WWOH), 51% (n = 432) reported SU in their lifetime (49% WWH, 57% WWOH) and 18% (n = 155) reported SU in the past year (16% WWH, 24% WWOH).

Among these 155 women reporting SU in the past year who were included in subsequent analysis, the median age was 47 years, 78% identified as non-Hispanic Black, 85% reported previous incarceration, 82% reported current cigarette use, and 46% endorsed >7 drinks/week (Table 1). Regarding mental health, 53% reported depressive symptoms and 40% attended a mental health visit in the past 6 months. Overall, 86% attended a health care provider visit, and among WWH, 88% attended an HIV care visit and 62% were virally suppressed in the past 6 months.

TABLE 1.

Demographic, Sociobehavioral, and Clinical Characteristics at Enrollment Among WIHS Participants Enrolled in Southern US Sites From 2013 to 2015 Who Reported SU in the Past Year Stratified by HIV Status (n = 155)

| Overall N = 155 |

Women with HIV N = 100 (64.5%) |

Women without HIV N = 55 (35.5%) |

P * | |

| Age, yr, median (Q1, Q3) | 47 (38, 51) | 47 (40, 51) | 46 (37, 52) | 0.7297† |

| Race, n (%) | ||||

| Non-Hispanic Black | 121 (78.1) | 76 (76.0) | 45 (81.8) | 0.4023 |

| Else§ | 34 (21.9) | 24 (24.0) | 10 (18.2) | |

| Health insurance║, n (%) | ||||

| No | 56 (36.1) | 20 (20.0) | 36 (65.5) | <0.0001 |

| Yes | 99 (63.9) | 80 (80.0) | 19 (34.6) | |

| Employment, n (%) | ||||

| No | 132 (85.2) | 88 (88.0) | 44 (80.0) | 0.1801 |

| Yes | 23 (14.8) | 12 (12.0) | 11 (20.0) | |

| Income, n (%) | ||||

| ≤$24,000 | 129 (87.8) | 84 (87.5) | 45 (88.2) | 0.8970 |

| >$24,000 | 18 (12.2) | 12 (12.5) | 6 (11.8) | |

| Education, n (%) | ||||

| ≤High school degree | 110 (71.0) | 70 (70.0) | 40 (72.7) | 0.7204 |

| >High school degree | 45 (29.0) | 30 (30.0) | 15 (27.3) | |

| Alcohol use¶, n (%) | ||||

| Abstain | 36 (23.2) | 26 (26.0) | 10 (18.2) | 0.2553 |

| 0–7 drinks/wk | 48 (31.0) | 33 (33.0) | 15 (27.3) | |

| >7 drinks/wk# | 71 (45.8) | 41 (41.0) | 30 (54.6) | |

| Cigarette smoking, n (%) | ||||

| Never | 20 (12.9) | 15 (15.0) | 5 (9.1) | 0.1883 |

| Current | 127 (81.9) | 78 (78.0) | 49 (89.1) | |

| Former | 8 (5.2) | 7 (7.0) | 1 (1.8) | |

| Depressive symptoms**, n (%) | ||||

| No | 72 (46.8) | 46 (46.5) | 26 (47.3) | 0.9233 |

| Yes | 82 (53.3) | 53 (53.5) | 29 (52.7) | |

| Ever incarcerated, n (%) | ||||

| No | 24 (15.5) | 15 (15.0) | 9 (16.4) | 0.8223 |

| Yes | 131 (84.5) | 85 (85.0) | 46 (83.6) | |

| Healthcare visit in past 6 mo, n (%) | ||||

| No | 22 (14.2) | 5 (5.0) | 17 (30.9) | <0.0001 |

| Yes | 133 (85.8) | 95 (95.0) | 38 (69.1) | |

| Mental health visit in past 6 mo, n (%) | ||||

| No | 93 (60.0) | 51 (51.0) | 42 (76.4) | 0.0020 |

| Yes | 62 (40.0) | 49 (49.0) | 13 (23.6) | |

| HIV care visit in past 6 mo¶,††, n (%) | ||||

| No | 11 (12.1) | 11 (12.1) | NA | NA |

| Yes | 80 (87.9) | 80 (87.9) | ||

| HIV RNA <200 c/mL††, n (%) | ||||

| No | 36 (37.9) | 36 (37.9) | NA | NA |

| Yes | 59 (62.1) | 59 (62.1) | ||

| cART use††, n (%) | ||||

| No | 27 (27.0) | 27 (27.0) | NA | NA |

| Yes | 73 (73.0) | 73 (73.0) | ||

| Marijuana, n (%) | ||||

| No | 65 (41.9) | 41 (41.0) | 24 (43.6) | 0.7503 |

| Yes | 90 (58.1) | 59 (59.0) | 31 (56.4) | |

| Crack/cocaine, n (%) | ||||

| No | 17 (11.0) | 7 (7.0) | 10 (18.2) | 0.0330 |

| Yes | 138 (89.0) | 93 (93.0) | 45 (81.8) | |

| Opioids, n (%) | ||||

| No | 145 (93.6) | 91 (91.0) | 54 (98.2) | 0.0984‡ |

| Yes | 10 (6.5) | 9 (9.0) | 1 (1.8) | |

| Intravenous drugs, n (%) | ||||

| No | 149 (96.1) | 96 (96.0) | 53 (96.4) | >0.9999‡ |

| Yes | 6 (3.9) | 4 (4.0) | 2 (3.6) | |

| Methamphetamine, n (%) | ||||

| No | 153 (98.7) | 99 (99.0) | 54 (98.2) | >0.9999‡ |

| Yes | 2 (1.3) | 1 (1.0) | 1 (1.8) | |

| Polysubstance use‡‡, n (%) | ||||

| No | 145 (93.6) | 91 (91.0) | 54 (98.2) | 0.0984 |

| Yes | 10 (6.4) | 9 (9.0) | 1 (1.8) | |

| Substance use treatment, n (%) | ||||

| No | 117 (75.5) | 72 (72.0) | 45 (81.8) | 0.1740 |

| Yes | 38 (24.5) | 28 (28.0) | 10 (18.2) | |

| Substance use frequency§§, n (%) | ||||

| Crack/cocaine | ||||

| None | 18 (11.6) | 8 (8.0) | 10 (18.2) | 0.1734 |

| Monthly | 61 (39.4) | 42 (42.0) | 19 (34.6) | |

| Weekly | 49 (31.6) | 30 (30.0) | 16 (34.6) | |

| Daily | 27 (17.4) | 20 (20.0) | 7 (12.7) | |

| Opioids | ||||

| None | 146 (94.2) | 92 (92.0) | 54 (98.2) | 0.5903‡ |

| Monthly | 1 (0.7) | 4 (4.0) | 1 (1.8) | |

| Weekly | 3 (1.9) | 3 (3.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Daily | 5 (3.2) | 1 (1.0) | 0 (0.0) |

Column percents may not total 100 due to rounding. Bold entries are variables with values (p < 0.05).

P value from χ2 unless otherwise noted.

Wilcoxon test.

Fisher exact test.

Else refers to all races/ethnicities except non-Hispanic Black: non-Hispanic White n = 22, Hispanic n = 7, Native American/Alaskan n = 4, and other = 1.

Health insurance includes public, private, and Ryan White benefits.

Collected at the first follow-up visit after enrollment.

Heavy drinking defined as consuming more than 7 drinks per week.

Defined as Center for Epidemiologic Studies-Depression score ≥ 16.

Among women living with HIV only.

Polysubstance was defined as >1 drug from 3: crack/cocaine, opioids, and methamphetamine only.

Self-reported frequency of use in the past 6 months.

cART, combination antiretroviral therapy; NA, not applicable.

SU Characteristics

On SU, 89% reported crack/cocaine, 6% reported opioids, 1% reported methamphetamine, and 6% reported polysubstance use. Regarding SU frequency, 39% (n = 61) reported crack/cocaine monthly, 32% (n = 49) weekly, and 17% (n = 27) daily and <1% (n = 1) reported opioids monthly, 2% (n = 3) weekly, and 3% (n = 5) daily. Over time, 80% (n = 118), 56% (n = 79), and 53% (n = 73) of women still reported SU at 1, 2, and 3 years after enrollment. By HIV status, 79% (n = 74), 53% (n = 48), and 55% (n = 48) WWH reported SU at 1, 2, and 3 years, respectively, and 82% (n = 44), 62% (n = 31), and 50% (n = 25) WWOH reported SU at these time points.

SU Treatment

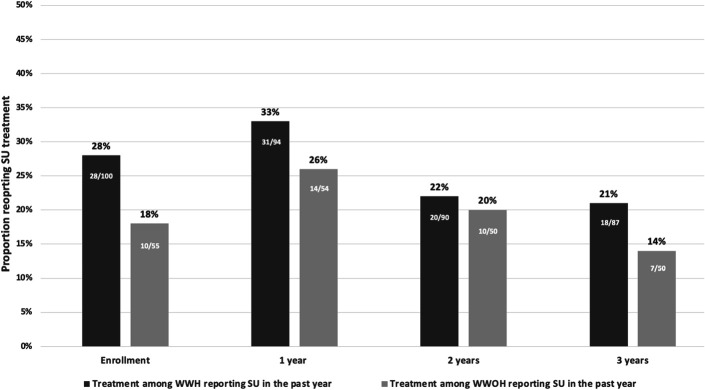

On treatment use, 25% (n = 38) at enrollment reported SU treatment in the past year (28% WWH, 18% WWOH, P = 0.17), including 26% (n = 36) and 40% (n = 4) of women who reported crack/cocaine and opioids, respectively. Of those engaged in polysubstance use, 40% (n = 4) reported treatment utilization. Overall, 30% (n = 45), 21% (n = 30), and 18% (n = 25) reported SU treatment at 1, 2, and 3 years; 38% (n = 57) reported SU treatment during at least 1 follow-up time point. While fewer WWOH reported SU treatment than WWH at enrollment, SU treatment engagement did not significantly differ by HIV serostatus at any time point (Fig. 1). Among WWH, 41% (n = 39) reported SU treatment during at least 1 follow-up time point vs. 33% (n = 18) WWOH (P = 0.38).

FIGURE 1.

SU treatment among WWH and comparable WWOH who reported SU in the past year at enrollment in the Southern US WIHS sites at enrollment, 1, 2, and 3 years (2013–2018).

HIV Care Outcomes

Among WWH, 88% (n = 80), 87% (n = 79), 91% (n = 81), and 83% (n = 72) reported an HIV care visit in the past 6 months at enrollment, 1, 2, and 3 years, respectively. Retention in HIV care did not significantly differ by SU treatment engagement at any time point (P = 0.74, P > 0.99, P = 0.36, and P = 0.73, respectively). At enrollment, 62% (n = 59) were virally suppressed, 80% (n = 20) among those reporting SU treatment, and 56% (n = 39) among those not reporting treatment (P = 0.032). Over time, 71% (n = 65), 81% (n = 70), and 72% (n = 60) were virally suppressed at 1, 2, and 3 years without significant differences by SU treatment engagement (P = 0.56, P > 0.99, P = 0.37, respectively).

DISCUSSION

This is the first description of SU, SU treatment, and corresponding HIV outcomes over time among women in the South. Our findings illustrate that while lifetime and past year SU were high in this observational cohort, only 1 in 4 women reported SU treatment engagement. Reflective of the HIV epidemic among women in the South, women reported primarily cocaine use, for which treatment is more variable and less standardized, unlike for opioid use disorder.23,27 National studies of WWH, WWOH, and reproductive age women report 9%–42% past year SU treatment.23,28 Adding to this literature, our analysis revealed low SU treatment over time for WWH and WWOH, demonstrating a critical gap in understanding treatment uptake and continuation. Furthermore, this gap was observed despite 86% of the study population reporting health care utilization in the past 6 months, suggesting that integrated solutions in various health care settings are needed to improve these potential access points for SU treatment. Given the high rate of prior justice system involvement in the study population, integrated care considering re-entry into the community should also be considered.

Although the care continuum framework has shaped HIV prevention and care, it has only recently emerged in the SU treatment literature.17,29–32 By characterizing SU, SU treatment, and HIV outcomes over time, our analysis illustrates data that can be used to populate a SU care continuum for individuals with HIV, variations of which have been proposed,17,18,33 to identify points for intervention and/or promotion of integrated HIV and SU care models. For example, we found that while SU treatment increased in the first year in this population, WWH and WWOH experienced substantial drop off in SU and SU treatment between 1 and 2 years while maintaining HIV outcomes. This may be a critical time point to add support for continued SU treatment engagement for those who may benefit in the context of HIV and other primary care services. Alternatively, given a drop off in both SU and SU treatment, it could represent the successful treatment of SUD in a subset of women by this time point. These 2 different implications reflect limited understanding of the optimal benchmarks for a SU care continuum, unlike in HIV care. For example, the optimal time for retention in SU treatment is not well-defined as evident by the range of timelines applied to analyze retention.25,34,35 Our analysis supports the need to better understand such drop offs through future qualitative work and larger epidemiologic studies for robust data on SU and treatment patterns to develop an evidence base which can address these gaps and inform appropriate benchmarks. Future studies must investigate how achievement of benchmarks in the SU and HIV care continuums overlap and differ to guide integrated care strategies in HIV, sexual health, and primary care settings.

Limitations of this analysis include that the study population may not be nationally representative, but as this is the largest cohort study of WWH and WWOH in the United States, our findings focus on the region that is the center of the US HIV epidemic. While we were not able to explore the role of pregnancy in this analysis, this is a critical area of service integration for reproductive age WWH and must be prioritized in future implementation and research. SU and treatment utilization were self-reported in questionnaires, which may yield desirability bias and potential misclassification. Although we were not able to assess the drivers of SU discontinuation and reasons for treatment disengagement, our study creates the foundation for qualitative work and multistate analyses to further quantify the cyclical nature of SU and treatment and define future benchmarks for successful treatment. This analysis also does not capture the formal diagnosis of SUD and was not able to characterize outcomes by degree of SU. However, by using SU in the past year as a proxy for SUD, this study offers novel data regarding SU, SU treatment, and HIV care patterns over time in a population for whom integrated services is essential to ending the syndemic.

Our results emphasize a crucial need to systematically explore opportunities to integrate SU treatment with other health care services and across diverse settings, such as community health clinics and the justice system, for this important and historically neglected population. Such work is critical for policy development and program implementation to bridge the gaps in SU and HIV care for women in the South. Such informed and integrated implementation focused on high-priority populations will bring us closer to ending the SU and HIV epidemics.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Data in this manuscript were collected by the Women's Interagency HIV Study (WIHS), now the Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study/WIHS Combined Cohort Study (MWCCS). The authors gratefully acknowledge the contributions of the study participants and dedication of the staff at the MWCCS sites. The authors thank the WIHS site co-investigators for serving as site liaisons for data collaboration. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

A.R. was supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the NIH (UL1TR002378 and TL1TR002382).

Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections, Virtual, February 2022.

The authors have no funding or conflicts of interest to disclose.

MWCCS (Principal Investigators): Atlanta Clinical Research Site (CRS) (Ighovwerha Ofotokun, Anandi Sheth, and Gina Wingood), U01-HL146241; Baltimore CRS (Todd Brown and Joseph Margolick), U01-HL146201; Bronx CRS (Kathryn Anastos, David Hanna, and Anjali Sharma), U01-HL146204; Brooklyn CRS (Deborah Gustafson and Tracey Wilson), U01-HL146202; Data Analysis and Coordination Center (Gypsyamber D'Souza, Stephen Gange and Elizabeth Topper), U01-HL146193; Chicago-Cook County CRS (Mardge Cohen and Audrey French), U01-HL146245; Chicago-Northwestern CRS (Steven Wolinsky), U01-HL146240; Northern California CRS (Bradley Aouizerat, Jennifer Price, and Phyllis Tien), U01-HL146242; Los Angeles CRS (Roger Detels and Matthew Mimiaga), U01-HL146333; Metropolitan Washington CRS (Seble Kassaye and Daniel Merenstein), U01-HL146205; Miami CRS (Maria Alcaide, Margaret Fischl, and Deborah Jones), U01-HL146203; Pittsburgh CRS (Jeremy Martinson and Charles Rinaldo), U01-HL146208; UAB-MS CRS (Mirjam-Colette Kempf, Jodie Dionne-Odom, and Deborah Konkle-Parker), U01-HL146192; University of North Carolina (UNC) CRS (Adaora Adimora and Michelle Floris-Moore), U01-HL146194. The MWCCS is funded primarily by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, with additional co-funding from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, National Institute on Aging, National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, National Institute of Mental Health, National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA), National Institute of Nursing Research, National Cancer Institute, National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities, and in coordination and alignment with the research priorities of the NIH, Office of AIDS Research. MWCCS data collection is also supported by UL1-TR000004 (University of California, San Francisco Clinical and Translational Science Award), UL1-TR003098 (Johns Hopkins University Institute for Clinical and Translational Research), UL1-TR001881 (University of California, Los Angeles Clinical and Translational Science Institute), P30-AI-050409 (Atlanta Center for AIDS Research [CFAR]), P30-AI-073961 (Miami CFAR), P30-AI-050410 (UNC CFAR), P30-AI-027767 (UAB CFAR), and P30-MH-116867 (Miami Center for HIV and Research in Mental Health). A.R. was supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the NIH (UL1TR002378 and TL1TR002382).

Contributor Information

Ayako W. Fujita, Email: wendy.fujita@emory.edu.

C. Christina Mehta, Email: christina.mehta@emory.edu.

Tracey E. Wilson, Email: tracey.wilson@downstate.edu.

Steve Shoptaw, Email: sshoptaw@mednet.ucla.edu.

Adam Carrico, Email: acarrico@fiu.edu.

Adaora A. Adimora, Email: catalina_ramirez@med.unc.edu.

Ellen F. Eaton, Email: eeaton@uabmc.edu.

Deborah L. Jones, Email: d.jones3@med.miami.edu.

Aruna Chandran, Email: achandr3@jhu.edu.

Anandi N. Sheth, Email: ansheth@emory.edu.

REFERENCES

- 1.Chavis NS, Klein PW, Cohen SM, et al. The health resources and services administration (HRSA) ryan white HIV/AIDS program's response to the opioid epidemic. J Infect Dis. 2020;222(suppl 5):S477–S485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jarlais DCD, Arasteh K, McKnight C, et al. Providing ART to HIV seropositive persons who use drugs: progress in New York city, prospects for “ending the epidemic”. AIDS Behav. 2016;20:353–362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Azim T, Bontell I, Strathdee SA. Women, drugs and HIV. Int J Drug Pol. 2015;26(suppl 1):S16–S21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cook JA, Burke-Miller JK, Steigman PJ, et al. Prevalence, comorbidity, and correlates of psychiatric and substance use disorders and associations with HIV risk behaviors in a multisite cohort of women living with HIV. AIDS Behav. 2018;22:3141–3154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Darlington CK, Lipsky RK, Teitelman AM, et al. HIV risk perception, pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) awareness, and PrEP initiation intention among women who use drugs. J Subst Use Addict Treat. 2023;152:209119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fauci AS, Redfield RR, Sigounas G, et al. Ending the HIV epidemic: a plan for the United States. JAMA. 2019;321:844–845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Abraham AJ, Andrews CM, Yingling ME, et al. Geographic disparities in availability of opioid use disorder treatment for medicaid enrollees. Health Serv Res. 2018;53:389–404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hand DJ, Short VL, Abatemarco DJ. Substance use, treatment, and demographic characteristics of pregnant women entering treatment for opioid use disorder differ by United States census region. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2017;76:58–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Short VL, Hand DJ, MacAfee L, et al. Trends and disparities in receipt of pharmacotherapy among pregnant women in publically funded treatment programs for opioid use disorder in the United States. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2018;89:67–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.CDC Issue Brief: HIV in the Southern United States. 2019. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/policies/cdc-hiv-in-the-south-issue-brief.pdf. Accessed January 31, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 11.HIV Among Women. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC); https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/group/gender/women/cdc-hiv-women.pdf (2021, Accessed June 1, 2023). [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hadland SE, Yule AM, Levy SJ, et al. Evidence-based treatment of young adults with substance use disorders. Pediatrics. 2021;147(suppl 2):S204–s214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stockings E, Hall WD, Lynskey M, et al. Prevention, early intervention, harm reduction, and treatment of substance use in young people. Lancet Psychiatry. 2016;3:280–296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Warner LA, Wei W, McSpiritt E, et al. Ante- and postpartum substance abuse treatment and antiretroviral therapy among HIV-infected women on Medicaid. J Am Med Womens Assoc (1972). 2003;58:143–153. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stein MD, Rich JD, Maksad J, et al. Adherence to antiretroviral therapy among HIV-infected methadone patients: effect of ongoing illicit drug use. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2000;26:195–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gonzalez A, Barinas J, O'Cleirigh C. Substance use: impact on adherence and HIV medical treatment. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2011;8:223–234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Eaton EF. “Rapid start” treatment to end the (other) epidemic: walking the tightrope without a net. Clin Infect Dis. 2021;72:479–481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Korthuis PT, Edelman EJ. Substance use and the HIV care continuum: important advances. Addict Sci Clin Pract. 2018;13:13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Adimora AA, Ramirez C, Benning L, et al. Cohort profile: the women's interagency HIV study (WIHS). Int J Epidemiol. 2018;47:393–394i. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bacon MC, von Wyl V, Alden C, et al. The Women's Interagency HIV Study: an observational cohort brings clinical sciences to the bench. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 2005;12:1013–1019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Montgomery L, Bagot K, Brown JL, et al. The association between marijuana use and HIV continuum of care outcomes: a systematic review. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2019;16:17–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sinha S, McCaul ME, Hutton HE, et al. Marijuana use and HIV treatment outcomes among PWH receiving care at an urban HIV clinic. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2017;82:102–106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fujita AW, Ramakrishnan A, Mehta CC, et al. Substance use treatment utilization among women with and without human immunodeficiency virus. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2023;10:ofac684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Radloff LS. The CES-D scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psychol Meas. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fine DR, Lewis E, Weinstock K, et al. Office-based addiction treatment retention and mortality among people experiencing homelessness. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4:e210477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Radfar N, Radfar SR, Mohammadi F, et al. Retention rate in methadone maintenance treatment and factors associated among referred patients from the compulsory residential centers compared to voluntary patients. Front Psychiatry. 2023;14:1139307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Penberthy JK, Ait-Daoud N, Vaughan M, et al. Review of treatment for cocaine dependence. Curr Drug Abuse Rev. 2010;3:49–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Martin CE, Scialli A, Terplan M. Unmet substance use disorder treatment need among reproductive age women. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2020;206:107679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Socías ME, Volkow N, Wood E. Adopting the 'cascade of care' framework: an opportunity to close the implementation gap in addiction care? Addiction. 2016;111:2079–2081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stanojlović M, Davidson L. Targeting the barriers in the substance use disorder continuum of care with peer recovery support. Subst Abuse. 2021;15:1178221820976988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Williams AR, Nunes EV, Bisaga A, et al. Developing an opioid use disorder treatment cascade: a review of quality measures. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2018;91:57–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Perlman DC, Jordan AE. Considerations for the development of a substance-related care and prevention continuum model. Front Public Health. 2017;5:180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Eaton EF, Tamhane A, Turner W, et al. Safer in care: a pandemic-tested model of integrated HIV/OUD care. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2022;231:109241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bakouni H, McAnulty C, Tatar O, et al. Associations of methadone and buprenorphine-naloxone doses with unregulated opioid use, treatment retention, and adverse events in prescription-type opioid use disorders: exploratory analyses of the OPTIMA study. Am J Addict. 2023;32:469–478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tierney HR, Takimoto SW, Azari S, et al. Predictors of linkage to an opioid treatment program and methadone treatment retention following hospital discharge in a safety-net setting. Subst Use Misuse. 2023;58:1172–1176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]