Abstract

One of the severe complications of the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection is myocarditis. However, the characteristics of fulminant myocarditis with SARS-CoV-2 infection are still unclear. We systematically reviewed the previously reported cases of fulminant myocarditis associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection from January 2020 to December 2022, identifying 108 cases. Of those, 67 were male and 41 female. The average age was 34.8 years; 30 patients (27.8%) were ≤20 years old, whereas 10 (9.3%) were ≥60. Major comorbidities included hypertension, obesity, diabetes mellitus, asthma, heart disease, gynecologic disease, hyperlipidemia, and connective tissue disorders. Regarding left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) at admission, 93% of the patients with fulminant myocarditis were classified as having heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (LVEF ≤ 40%). Most of the cases were administered catecholamines (97.8%), and mechanical circulatory support (MCS) was required in 67 cases (62.0%). The type of MCS was extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (n = 56, 83.6%), percutaneous ventricular assist device (Impella®) (n = 19, 28.4%), intra-aortic balloon pumping (n = 12, 12.9%), or right ventricular assist device (n = 2, 3.0%); combination of these devices occurred in 20 cases (29.9%). The average duration of MCS was 7.7 ± 3.8 days. Of the 76 surviving patients whose cardiac function was available for follow-up, 65 (85.5%) recovered normally. The overall mortality rate was 22.4%, and the recovery rate was 77.6% (alive: 83 patients, dead: 24 patients; outcome not described: 1 patient).

1. Background

The severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection or coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has been a global public health issue leading to significant morbidity and mortality worldwide [1, 2]. SARS-CoV-2 infection predominately results in an acute respiratory illness; however, sometimes cardiovascular complications arise, such as heart failure, pericardial effusion, and, rarely, myocarditis [3]. SARS-CoV-2 infection-related myocarditis has been reported since the beginning of the viral outbreak; fulminant myocarditis is a rare, yet life-threatening, variant with significant mortality, and often demands the emergent initiation of mechanical circulatory support (MCS) [3, 4]. Additionally, balancing infection protection and its treatment is challenging. Fulminant myocarditis due to SARS-CoV-2 infection is very rare and its characteristics still unclear. In this systematic literature review, we aimed to describe all cases of myocarditis associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection reported globally.

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design

We systematically reviewed the literature for reports of fulminant myocarditis associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection. This literature review was conducted in concordance with the guidelines provided by the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) statement [5]. Registration of a review protocol was deemed unnecessary, as we used data presented in published literature for this study.

2.2. Eligibility and Exclusion Criteria

The included publications were full-length manuscripts retrieved with our search that contained data on one or more patients who acutely presented with myocarditis and recent SARS-CoV-2 infection, which was definitively diagnosed by any tests. Myocarditis was diagnosed by one or more of the following characteristics: clinically suspected myocarditis [6], elevated troponin levels and abnormal electrocardiograms, and impaired cardiac function on echocardiography and findings consistent with myocarditis on cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR) imaging (including myocardial edema or late gadolinium enhancement) or on endomyocardial biopsy (EMB) [7]. Moreover, fulminant myocarditis was defined as myocarditis with the new onset of heart failure with cardiogenic shock requiring ionotropic drugs or MCS, or histologically proven myocarditis with sudden death for which autopsy was available. Publications were first screened and excluded if they were written in languages other than English without an English interpretation. After the first screening, publications were excluded if any of the following conditions were met: not a case report or a human report; not a case of SARS-CoV-2 infection-related myocarditis; not a case of related myocarditis (for example, cases of acute coronary syndrome or pericarditis); not a case of fulminant myocarditis, using the definition provided above.

2.3. Search Strategy

We searched PubMed for all articles on myocarditis with SARS-CoV-2 infection published from January 1, 2020, to December 31, 2022, using the following keywords: (((((2019 novel coronavirus) OR (COVID-19)) OR (SARS-CoV-2)) OR (2019 ncov infection)) OR (2019 novel coronavirus)) AND (((cardiogenic shock) AND (myocarditis)) OR (fulminant myocarditis) OR (((extracorporeal membrane oxygenation) OR (Intra-aortic balloon pumping) OR (Impella)) AND (myocarditis))).

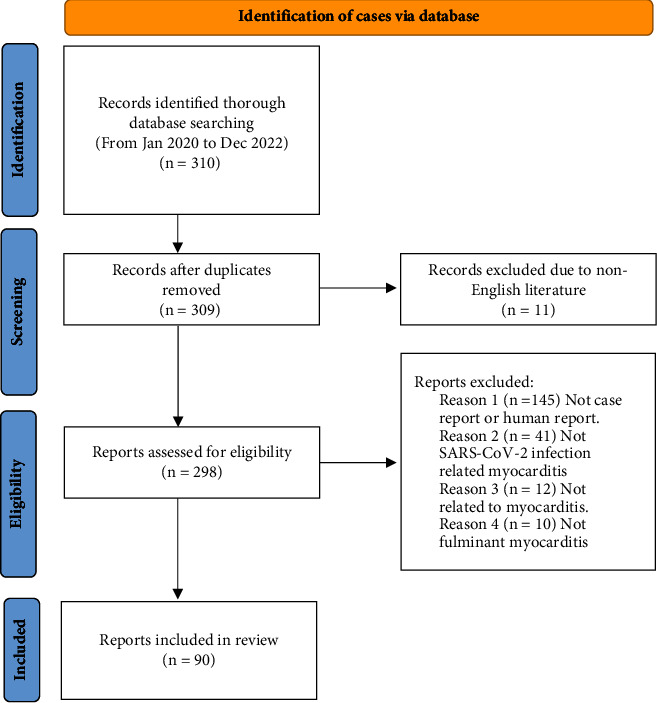

All articles retrieved from the systematic search were exported to EndNote Reference Manager (Version X9; Clarivate Analytics, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA). All the identified publications were further screened for the inclusion and exclusion criteria by reading the full-text publications. The articles were assessed by two assessors (RO and TI) independently; if the two assessors' decision differed, a third assessor (HK) provided the final decision for inclusion. The PRISMA flowchart summarizes the results of our literature search (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The PRISMA flowchart.

2.4. Data Extraction Process

The included publications were analyzed for the authors' names, publication year, and patient-related data, namely, demographics, comorbidities, history of vaccination, clinical presentation, findings on echocardiography, arrhythmia, CMR data, biopsy findings, treatments, and outcomes.

3. Results

We identified a total of 108 patients from 90 studies relevant to fulminant myocarditis with SARS-CoV-2 infection (Tables 1 and 2) [8–97] of which 67 were male (62%) and 41 female (38%). The mean age of the patients was 34.8 ± 18.1 (range 0–72) years; thirty patients (27.8%) were ≤20-years old, whereas 10 (9.3%) were ≥60. Almost half the patients (n = 48) were previously healthy, and within the ones that presented major comorbidities, those included hypertension (n = 12), obesity (n = 11), diabetes mellitus (n = 8), asthma (n = 4), heart disease (n = 4), gynecologic disease (n = 4), hyperlipidemia (n = 3), and connective tissue disorders (n = 3); patient's characteristics were not described in detail in 21 cases. Only 4 patients received previous vaccination; among the 19 cases with available vaccination history, 2 patients received the first dose, 1 received two doses, and 1 received three doses. However, the vaccination history was not documented in most cases, as the vaccine itself was initially unavailable in several countries. No patients had received more than three doses of the vaccine. Excluding the 10 patients whose symptoms were not reported, fever (n = 51, 52.0%) was the most common symptom at initial presentation, followed by dyspnea or shortness of breath (n = 45, 45.9%), diarrhea (n = 20, 20.4%), chest pain (n = 20, 20.4%), cough (n = 19, 19.4%), vomiting (n = 17, 17.3%), and abdominal pain (n = 13, 13.3%). Vague symptoms such as asthenia (n = 9, 9.2%), fatigue (n = 9, 9.2%), weakness (n = 5, 5.1%), lethargy (n = 5, 5.1%), and loss of appetite (n = 3, 3.1%) were unusual. The median time from symptom onset to myocarditis diagnosis was 6 days (Interquartile range 3–9 days).

Table 1.

Literature review of cases with fulminant myocarditis with SARS-CoV-2 infection.

| Case | Author | Year (reference) | Age (years) | Sex | Comorbidities | Dose of vaccination | Initial symptoms | Time (symptoms to diagnosis of myocarditis) | Pneumonia | LVEF (%) | PE | LVWT | Arrhythmia | CMR | Biopsy findings | Catecholamine | Antiviral treatment | Immunomodulatory therapy | MCS | Duration of MCS use (days) | Cardiac recovery | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Noone et al. | 2022 [8] | 38 | F | None | 0 | Cold-like symptoms and relapsing syncope | 5 | No | <20 | Yes | Yes | None | — | — | Yes | — | — | VA-ECMO Impella CP |

8 | Fully | Alive |

| 2 | Hoang et al. | 2022 [9] | 42 | F | ND | 3 | Chest pain, dyspnea, lethargy, and fever | 8 | No | 25 | No | No | VF | — | — | No | No | No | VA-ECMO | 7 | Fully | Alive |

| 3 | De Smet et al. | 2022 [10] | 25 | M | None | 2 | Fever, abdominal pain, vomiting, and diarrhea | 6 | No | Moderately decreased LVEF | Yes | No | None | Moderately dilated left ventricle with moderately reduced systolic function, increased myocardial extracellular volume by T1-mapping, no focal myocardial LGE | — | Yes | No | Corticosteroid IVIG |

No | — | Fully | Alive |

| 4 | Usui et al. | 2022 [11] | 44 | F | None | 0 | Chest pain | 5 | No | 10 | Yes | Yes | None | Diffuse oedematous wall thickening with high signal intensity in T2-weighted images, LGE in the basal to the apical inferolateral mid-myocardial wall | — | Yes | Remdesivir | Corticosteroid baricitinib | VA-ECMO Impella CP |

10 | Fully | Alive |

| 5 | Ardiana and Aditya | 2022 [12] | 40 | M | None | ND | Chest pain | 3 | No | ND | Yes | Yes | CAVB | — | — | Yes | No | — | IABP | 6 | Fully | Alive |

| 6 | Ya'Qoub et al. | 2022 [13] | 30 | M | ND | ND | Heart failure symptoms | ND | ND | 10 | ND | ND | VF | — | — | ND | — | — | VA-ECMO | — | ND | ND |

| 7 | Ajello et al. | 2022 [14] | 49 | M | None | ND | Fever and dyspnea | 4 | No | 10 | No | ND | ND | Diffuse increase of native T2 and native T1, no LGE | Lymphomonocytic inflammatory infiltrates with cardiomyocytes necrosis | Yes | No | No | Impella CP/5.0/RP | 10 | Fully | Alive |

| 8 | Asakura et al. | 2022 [15] | 49 | M | None | ND | Chest pain | 6 | No | <20 | No | Yes | None | Mild LGE on the epicardial side of the inferior wall of the heart base, mild high signal on T2-weighted MRI of the same area, mild high signal on T1-weighted MRI, mild fibrosis, and edema-like changes | Mild myocyte hypertrophy, some subendocardial fibrosis, and scattered cluster of differentiation 3 (CD3)-positive T cells | Yes | No | Methylprednisolone | Impella 5.0 | 10 | Fully | Alive |

| 9 | Nakatani et al. | 2022 [16] | 49 | M | None | 1 | Sore throat, chill, and fever | 4 | Yes | <20 | ND | Yes | None | — | Mild lymphocytic infiltration and moderate to severe perivascular fibrosis with wall thickening of intramural arterioles | Yes | No | Methylprednisolone, IVIG | ECMO | 5 | — | Dead |

| 10 | Callegari et al. | 2022 [17] | 15 | M | None | ND | Reduced appetite, gastroenteritis, mild dyspnoea, and dizziness | 13 | No | 20 | Yes | No | VT | No myocardial oedema or myocardial contrast enhancement | The histological results were not consistent with an acute/chronic lymphocytic, eosinophilic, or giant-cell myocarditis, or dilated cardiomyopathy | Yes | No | No | No | — | Fully | Alive |

| 11 | Phan et al. | 2022 [18] | 9 | M | None | ND | Fever, cough, and sore throat | 4 | No | 18 | ND | ND | None | — | — | Yes | No | Dexamethasone | VA-ECMO | 10 | Fully | Alive |

| 12 | Carrasco-Molina et al. | 2022 [19] | 36 | M | ND | ND | Dyspnea and chest pain | 7 | No | 30 | No | No | None | Myocardial inflammation | Lymphocytic inflammatory infiltrate (35 CD3+/mm2 lymphocytes), without myocyte necrosis or fibrosis | Yes | No | Methylprednisolone | No | — | Fully | Alive |

| 13 | Kohli et al. | 2022 [20] | 15 | F | None | ND | Headache, vomiting, and fatigue | 1 | No | 20 (LVSF) | No | No | AF | — | — | Yes | — | Methylprednisolone, IVIG, and anakinra | No | — | LVSF 34% | Alive |

| 14 | Bhardwaj et al. | 2022 [21] | 22 | M | ND | 0 | ND | ND | ND | 25 | ND | ND | PEA | — | — | ND | Remdesivir | Steroid | VA-ECMO | 5 | Fully | Alive |

| 15 | Bhardwaj et al. | 2022 [21] | 53 | F | ND | 0 | ND | ND | ND | 5 | ND | ND | None | — | — | ND | Remdesivir | Steroid | VA-ECMO | 9 | LVEF 45% | Alive |

| 16 | Bhardwaj et al. | 2022 [21] | 28 | F | ND | 0 | ND | ND | ND | 36 | ND | ND | PEA | — | — | ND | Remdesivir | Steroid, IVIG, and tocilizumab | VA-ECMO | 5 | Fully | Dead |

| 17 | Bhardwaj et al. | 2022 [21] | 27 | F | ND | 0 | ND | ND | ND | 22 | ND | ND | None | — | — | ND | Remdesivir | Steroid and IVIG | VA-ECMO | 10 | Fully | Alive |

| 18 | Bhardwaj et al. | 2022 [21] | 46 | M | ND | 0 | ND | ND | ND | 8 | ND | ND | None | — | — | ND | Remdesivir | Steroid and IVIG | VA-ECMO | 6 | LVEF 30% | Dead |

| 19 | Bhardwaj et al. | 2022 [21] | 68 | M | ND | 0 | ND | ND | ND | 20 | ND | ND | None | — | — | ND | No | Steroid | VA-ECMO | 2 | ND | Alive |

| 20 | Bhardwaj et al. | 2022 [21] | 26 | F | ND | 1 | ND | ND | ND | 10 | ND | ND | PEA | — | — | ND | No | Steroid | VA-ECMO | 9 | Fully | Alive |

| 21 | Bhardwaj et al. | 2022 [21] | 66 | M | ND | 0 | ND | ND | ND | 10 | ND | ND | VT, VF | — | — | ND | No | Steroid | VA-ECMO | 8 | Fully | Alive |

| 22 | Bhardwaj et al. | 2022 [21] | 24 | M | ND | 0 | ND | ND | ND | 15 | ND | ND | VF | — | — | ND | No | Steroid | VA-ECMO | 7 | Fully | Alive |

| 23 | Mejia et al. | 2022 [22] | 17 | F | ND | ND | ND | — | No | ND | ND | Yes | None | — | — | ND | No | No | VA-ECMO | 10 | ND | Alive |

| 24 | Rajpal et al. | 2022 [23] | 60 | F | Asthma | ND | Fatigue, shortness of breath, and palpitations | 9 | No | <15 | Yes | Yes | VT | Diffuse hyperintensity on T2 mapping | Scattered perivascular and interstitial inflammatory cells consisting of CD3-positive T-lymphocytes, CD20 positive B-lymphocytes, and histiocytes, along with interstitial and myocyte injury | Yes | No | Methylprednisolone | VA-ECMO | 10 | Fully | Alive |

| 25 | Buitrago et al. | 2022 [24] | 12 | F | None | ND | Headache, neck pain, nausea, diarrhea, and lethargy | 2 | No | Reduced | No | No | PVC/VT | — | Severe myocarditis without signs of viral infection with severe and diffuse accumulation of CD3 positive T cells | Yes | No | Methylprednisone | VA-ECMO | 7 | Stable | Alive |

| 26 | Thomson et al. | 2022 [25] | 39 | F | Ovarian disease | 0 | Diarrhoea, vomiting, and abdominal pain | 3 | No | Near ventricular standstill | Yes | Yes | PEA | — | Mild interstitial infiltrate consisting mostly of CD68+ macrophages along with a lesser number of CD3+ T cells | Yes | No | Methylprednisolone, IVIG, and tocilizumab | VA-ECMO | 9 | — | Dead |

| 27 | Rodriguez Guerra et al. | 2022 [26] | 56 | M | HT and DM | ND | Syncope | <7 | No | ND | ND | ND | Long QT | — | — | Yes | No | No | No | 1 | — | Dead |

| 28 | Verma et al. | 2022 [27] | 48 | F | ND | ND | Shortness of breath and chest pressure | 5 | No | 15 | Yes | Yes | None | — | Cardiomyocyte damage with prominent macrophage infiltrates. The presence of SARS-CoV-2 in cardiomyocyte is confirmed by RNA scope detecting SARS-CoV-2 spike S antisense strain | Yes | Remdesivir | Methylprednisolone and tocilizumab | VA-ECMO Impella CP |

13 | Fully | Alive |

| 29 | Edwards et al. | 2022 [28] | 10 months | M | Trisomy 18p, monosomy of 8p, and a small conoventricular ventricular septal defect | ND | Upper respiratory symptoms and fever | 4 | No | Severely diminished | Yes | Yes | None | T2 weighted imaging demonstrated significantly increased myocardial to skeletal muscle signal intensity | — | Yes | Remdesivir | Dexamethasone and IVIG | VA-ECMO | 8 | Fully | Alive |

| 30 | Aldeghaither et al. | 2022 [29] | 39 | F | None | ND | Fever, dyspnea, chest pain, and diarrhea | 28 | No | 10–15 | Yes | No | None | — | Eosinophilic infiltrate of the myocardium | Yes | No | Methylprednisolone | VA-ECMO Impella CP RVAD |

9 | LVEF of 30–35% | Alive |

| 31 | Aldeghaither et al. | 2022 [29] | 25 | M | None | ND | Dyspnea, fever, and hypotension | 35 | No | 15–20 | ND | ND | None | — | Mixed inflammatory cells with some eosinophils | Yes | No | Corticosteroid, IVIG, and anakinra | Impella CP | 5 | LVEF of 35–40% | Alive |

| 32 | Aldeghaither et al. | 2022 [29] | 21 | M | ND | ND | Dyspnea and fever | 28 | No | 5–10 | ND | ND | None | — | Lymphocytic infiltrate | Yes | No | Methylprednisolone, IVIG, and anakinra | VA-ECMO Impella CP |

3 | LVEF of 45–50% | Alive |

| 33 | Valiton et al. | 2022 [30] | 52 | F | Raynaud syndrome | ND | Shortness of breath, chest pain, and dizziness | 3 | No | 25 | Yes | Yes | None | — | Thrombotic microangiopathy of the coronary capillaries with endothelial cell activation (endothelitis) characterized by enlarged nuclei and capillary thrombosis | Yes | No | Dexamethasone | Impella CP | 6 | Fully | Alive |

| 34 | Ismayl et al. | 2022 [31] | 53 | M | None | ND | Fever and upper respiratory symptoms | 35 | No | 25 | ND | ND | ND | — | Diffuse interstitial and perivascular neutrophilic and lymphocytic infiltration with rare eosinophils and rare myocyte necrosis | Yes | No | Steroids | VA-ECMO Impella CP |

5 | Fully | Alive |

| 35 | Yalcinkaya et al. | 2022 [32] | 29 | M | ND | 0 | Chest pain | ND | ND | Reduced ejection fraction | ND | ND | ND | Left ventricular apical thrombus, myocardial edema | Eosinophilic myocarditis | Yes | No | ND | No | — | ND | Alive |

| 36 | Nagata et al. | 2022 [33] | 13 | M | None | ND | Fever and malaise, nausea, and watery diarrhea | 20 | No | 20 | ND | ND | IRBBB | — | — | Yes | No | Prednisolone and IVIG | No | — | ND | Alive |

| 37 | Nishioka and Hoshino | 2022 [34] | 15 | M | None | ND | Fever, fatigue, and abdominal pain | 2 | No | 25 | Yes | ND | CAVB, prolonged QT interval, NSVT | — | — | Yes | No | No | VA-ECMO | 2 | LVEF 45% | Alive |

| 38 | Shahrami et al. | 2022 [35] | 7 | M | ND | ND | Dyspnea | 10 | Yes | 25 | No | No | AF | — | — | Yes | Hydroxychloroquine | Dexamethasone and IVIG | — | — | LVEF 45% | Dead |

| 39 | Menger et al. | 2022 [36] | 4 | F | Obesity | ND | Respiratory distress | 7 | Yes | ND | ND | ND | ND | — | The posterior wall of the heart showed small-spot fading | Yes | Remdesivir and bamlanivimab | Dexamethasone | VA-ECMO | 17 | — | Dead |

| 40 | Vannella et al. | 2021 [37] | 26 | M | None | ND | Chest pressure, shortness of breath, nausea, vomiting, and chills | 7 | No | <10 | ND | ND | SVT | — | Myocardial necrosis surrounded by cytotoxic T-cells and tissue-repair macrophages | Yes | — | — | VA-ECMO | — | — | Dead |

| 41 | Gozar et al. | 2021 [38] | 3 days | F | No | No | Arrhythmia | 2 | No | 30 | Yes | ND | VT | — | — | Yes | — | Dexamethasone and IVIG | No | — | Fully | Alive |

| 42 | Shen et al. | 2021 [39] | 43 | M | No | ND | Fever and abdominal pain | 49 | No | 20–25 | ND | ND | None | Diffuse myocardial oedema without delayed myocardial enhancement | — | Yes | No | IVIG | IABP | 4 | Fully | Alive |

| 43 | Ishikura et al. | 2021 [40] | 35 | M | No | ND | Fever and general weakness | 21 | No | 7.4 | ND | ND | None | — | — | Yes | Yes (details unknown) | Steroid and IVIG | VA-ECMO IABP |

7 | Fully | Alive |

| 44 | Saha et al. | 2021 [41] | 25 days | F | Sepsis | No | Fever | 17 | No | 40 | Yes | No | Cardiac arrest | — | — | Yes | No | Methylprednisolone and IVIG | No | — | LVEF 65% | Alive |

| 45 | Yeleti et al. | 2021 [42] | 25 | M | None | ND | Fever, abdominal pain, fatigue, and vomiting | 120 | No | 5–10 | Yes | No | VT | Transmural late gadolinium enhancement of basal-mid anterolateral and inferolateral segments | Lymphocytic myocarditis | ND | Remdesivir convalescent plasma | Methylprednisolone | Bilateral Impellas VA-ECMO |

3 | Normal | Alive |

| 46 | Gurin et al. | 2021 [43] | 26 | M | ND | ND | Fevers, chills, headache, nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea | 7 | Yes | 20 | Yes | No | None | — | Interstitial edema and inflammatory infiltrate consisting predominantly of interstitial macrophages with scant T-lymphocytes | Yes | — | Solumedrol and IVIG | No | — | LVEF 75% | Alive |

| 47 | Fiore et al. | 2021 [44] | 45 | M | None | ND | Shortness of breath, confusion, and asthenia | 5 | Yes | 25 | No | No | None | Severe impairment of biventricular global function associated with higher values of T1 and T2 mapping, in the absence of late gadolinium enhancement | Mild lymphohistiocytic inflammatory infiltrate without myocardial necrosis | Yes | Hydroxychloroquine | Anakinra | IABP | 7 | LVEF 55% | Alive |

| 48 | Bemtgen et al. | 2021 [45] | 18 | M | None | ND | Fever, chills, and tachycardia | 14 | No | 25 | Yes | No | None | — | Significant infiltration of immune cells (CD68+ macrophages and CD3+ T cells) | Yes | — | Dexamethasone, IVIG, and anakinra | VA-ECMO Impella |

7 | Fully | Alive |

| 49 | Tseng et al. | 2021 [46] | 5 | M | None | No | Fatigue and vomiting | 1 | No | ND | ND | ND | VT | — | — | Yes | — | Methylprednisolone and IVIG | VA-ECMO | 5 | ND | Alive |

| 50 | Gaudriot et al. | 2021 [47] | 38 | M | Chronic lymphopenia | ND | Chest pain and vomiting | 28 | Yes | 25 | Yes | Yes | IRBBB | T2 sequences showed diffuse hyperintense myocardium. Late gadolinium enhancement images demonstrated massive, heterogeneous, and predominantly subepicardial enhancement of the left ventricular myocardium | Myocardial necrosis, suppurated lesions, and lymphocytic infiltration | Yes | — | Antilymphocyte serum, corticosteroids, and mycophenolate mofetil (after heart transplantation) | VA-ECMO Impella |

8 | Not recovered | Alive (heart transplantation) |

| 51 | Menter et al. | 2021 [48] | 47 | F | Obesity | ND | Unconscious and apneic | 7 | Yes | 30 | ND | No | VF | — | Mild diffuse necrotizing myocarditis accompanied by extensive thrombotic microangiopathy of cardiac capillaries | Yes | No | No | No | — | No | Dead |

| 52 | Ghafoor et al. | 2021 [49] | 54 | F | HT, obesity, and heart failure | ND | Dyspnea, nausea, and vomiting | 7 | No | 10–15 | No | No | PEA | — | — | Yes | No | No | VA-ECMO | ND | — | Dead |

| 53 | Okor et al. | 2021 [50] | 72 | F | HT and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | ND | Shortness of breath | 7 | ND | 20 | Yes | No | None | — | — | Yes | No | Methylprednisolone | No | — | LVEF 50% | Dead |

| 54 | Tomlinson et al. | 2021 [51] | 13 | M | None | ND | Fever, listlessness, abdominal pain, vomiting, diarrhoea, headache, and rash | — | No | 53 | ND | ND | Ectopic wandering atrial pacemaker | — | — | Yes | No | No | No | — | — | Alive |

| 55 | Sampaio et al. | 2021 [52] | 45 | M | None | ND | Dyspnea, fever, myalgia, and postural hypotension | 7 | Yes | Normal | Yes | No | Asystole | — | — | Yes | Convalescent plasma | Methylprednisolone, IVIG, and tocilizumab | VA-ECMO | 9 | Fully | Alive |

| 56 | Apostolidou et al. | 2021 [53] | 7 | F | Late preterm birth, central hypothyroidism, failure to thrive, and recurrent respiratory tract infections | ND | Headache, loss of appetite, abdominal pain, and vomiting | 3 | Yes | Fractional shortening 10% | Yes | No | None | — | Acute lymphocytic myocarditis | Yes | Remdesivir convalescent plasma, and interferon-γ | Methylprednisolone, anakinra and extracorporeal hemadsorption | VA-ECMO Impella |

21 | — | Dead |

| 57 | Kallel et al. | 2021 [54] | 26 | M | None | ND | Diarrhea, vomiting, fever, fatigue, and weakness | 8 | Yes | 30 | Yes | No | None | Normal (7 weeks after the treatment) | — | Yes | No | No | No | — | LVEF 55% | Alive |

| 58 | Bulbul et al. | 2021 [55] | 49 | F | None | ND | Cough and shortness of breath | 7 | Yes | 25 | ND | ND | None | — | — | Yes | Hydroxychloroquine, oseltamivir, lopinavir, and ritonavir | Methylprednisolone, IVIG, and tocilizumab | VA-ECMO | 7 | LVEF 50% | Alive |

| 59 | Gauchotte et al. | 2021 [56] | 69 | M | HT, DM, and ischemic heart disease | ND | Fever, asthenia, and abdominal pain | 7 | No | 20 | Yes | ND | ND | — | Abundant myocardium edema and interstitial inflammation, showing a predominance of mononucleated leucocytes, associated with cardiomyocytes dystrophies | Yes | No | No | VA-ECMO | — | — | Dead |

| 60 | Gulersen et al. | 2021 [57] | 31 | F | Pregnant | ND | Cough, myalgias, and diarrhea | 7 | No | ND | Yes | ND | None | Normal cardiac function (not mentioned about myocarditis) | — | Yes | No | Dexamethasone and IVIG | No | — | Normal | Alive |

| 61 | Rasras et al. | 2021 [58] | 47 | F | None | ND | Dyspnea and leg pain | 21 | Yes | 10 | ND | ND | ND | — | — | Yes | No | Methylprednisolone | No | — | LVEF 30% | Alive |

| 62 | Purdy et al. | 2021 [59] | 53 | M | None | ND | Cough, fever, and shortness of breath | 35 | No | 25 | No | No | None | — | — | Yes | Hydroxychloroquine | Methylprednisolone | No | — | LVEF 60% | Alive |

| 63 | Purdy et al. | 2021 [59] | 30 | F | Obesity | ND | Fatigue and shortness of breath | 9 | Yes | 45 | Yes | ND | None | — | — | Yes | Hydroxychloroquine | Methylprednisolone | No | — | LVEF 55% | Alive |

| 64 | Sivalokanathan et al. | 2021 [60] | 37 | M | None | ND | Fever, diarrhea, and dizziness | 30 | Yes | 21 | Yes | ND | None | Left ventricular wall thickening, inhomogeneity of T1/T2 mapping values, and patchy non-infarct pattern late gadolinium enhancement in the inferolateral and apical septal walls | — | Yes | No | Hydrocortisone and IVIG | No | — | LVEF 70% | Alive |

| 65 | Ruiz et al. | 2021 [61] | 35 | F | Systemic sclerosis | ND | Generalized malaise, fever, and cough | 5 | Yes | <10 | No | No | PEA | Myocarditis (no detail) | — | Yes | Remdesivir | Methylprednisolone and IVIG | Bilateral impellas | 14 | LVEF 60% | Alive |

| 66 | Papageorgiou et al. | 2021 [62] | 43 | M | Mixed connective tissue disease | ND | Fever, cough, and chest pain | 4 | No | 10–15 | Yes | No | None | — | No evidence of myocarditis | Yes | No | Hydrocortisone | VA-ECMO Impella CP |

7 | Normal | Alive |

| 67 | Ciuca et al. | 2021 [63] | 6 | M | None | ND | Fever | 5 | Yes | 48 | Yes | No | None | Myocardial interstitial edema in T1/T2 mapping | — | Yes | Hydroxychloroquine | Dexamethasone and IVIG | No | — | Fully | Alive |

| 68 | Garau et al. | 2021 [64] | 18 | F | None | ND | Nausea and vomiting | 1 | No | 10 | Yes | Yes | None | Late gadolinium enhancement in basal to midinferior and inferoseptal segments | A low density of inflammatory cells without myocyte degeneration or necrosis | Yes | Hydroxychloroquine | Methylprednisolone and IVIG | VA-ECMO IABP |

17 | LVEF 48% | Alive |

| 69 | Hékimian et al. | 2021 [65] | 40 | M | Obesity and DM | ND | Dyspnea and asthenia | 2 | Yes | 45 | ND | ND | None | — | — | Yes | ND | No | VA-ECMO VV-ECMO |

8 | LVEF 60% | Alive |

| 70 | Hékimian et al. | 2021 [65] | 19 | F | None | ND | Fever, dyspnea, and cough | 9 | Yes | 30 | ND | ND | None | — | — | Yes | ND | No | VV-ECMO | 15 | LVEF 50% | Alive |

| 71 | Hékimian et al. | 2021 [65] | 22 | M | Obesity, DM, and asthma | ND | Fever, dyspnea, cough, and asthenia | 1 | Yes | 30 | ND | ND | None | — | — | No | ND | No | VV-ECMO | 5 | LVEF 60% | Alive |

| 72 | Hékimian et al. | 2021 [65] | 19 | M | None | ND | Fever, headache, diarrhea, dyspnea, and asthenia | 4 | No | 15 | ND | ND | None | — | — | Yes | ND | No | No | — | LVEF 60% | Alive |

| 73 | Hékimian et al. | 2021 [65] | 16 | M | None | ND | Fever, anosmia, abdominal pain, rash, conjunctivitis, strawberry tongue, chest pain, asthenia, and adenopathy | 7 | Yes | 20 | ND | ND | None | — | — | Yes | ND | IVIG | No | — | LVEF 45% | Alive |

| 74 | Hékimian et al. | 2021 [65] | 17 | M | Aortic regurgitation | ND | Fever, headache, abdominal pain, diarrhea, dyspnea, asthenia, and conjunctivitis | 4 | No | 20 | ND | ND | None | — | — | Yes | ND | Corticosteroid and IVIG | No | — | LVEF 50% | Alive |

| 75 | Hékimian et al. | 2021 [65] | 17 | F | None | ND | Chest pain and dyspnea | 1 | No | 20 | ND | ND | VT, cardiac arrest | — | — | Yes | ND | Corticosteroid and IVIG | VA-ECMO | — | No | Dead |

| 76 | Milla-Godoy et al. | 2021 [66] | 45 | F | Obesity | ND | Diarrhea, nausea, and vomiting | 4 | Yes | 10 | No | ND | Asystole | — | — | Yes | — | Methylprednisolone and IVIG | No | — | No | Dead |

| 77 | Hu et al. | 2021 [67] | 37 | M | ND | ND | Chest pain, dyspnea, and diarrhea | 3 | Yes | 27 | Yes | ND | None | — | — | Yes | No | Methylprednisoloneand IVIG | No | — | LVEF 66% | Alive |

| 78 | Marcinkiewicz et al. | 2021 [68] | 20 | M | None | ND | Fever and dyspnea | 42 | ND | 15 | No | Yes | None | Myocardial signal was globally increased on T2-weighted imaging. Delayed late gadolinium imaging showed diffuse fibrosis in the anteroseptal and inferior walls | — | ND | No | No | VA-ECMO IABP |

6 | LVEF 69% | Alive |

| 79 | Gay et al. | 2020 [69] | 56 | M | Obesity, HL | ND | Dyspnea and lethargy | 1 | Yes | <5 | Yes | Yes | ND | — | — | ND | — | Methylprednisolone and tocilizumab | VA-ECMO Impella 2.5/5.0 ProtekDuo |

12 | LVEF 65% | Alive |

| 80 | Jacobs et al. | 2020 [70] | 48 | M | HT | ND | Fever, diarrhea, cough, dysosmia, and dyspnea | 7 | Yes | ND | No | Yes | ND | — | Hypertrophic cardiac tissue with patchy muscular, sometimes perivascular, and slightly diffuse interstitial mononuclear inflammatory infiltrates, dominated by lymphocytes | Yes | No | — | VA-ECMO | — | No | Dead |

| 81 | Lozano Gomez et al. | 2020 [71] | 53 | M | None | ND | Fever and dyspnea | 10 | No | 10 | ND | ND | AF | — | — | Yes | No | No | No | — | No | Dead |

| 82 | Tiwary et al. | 2020 [72] | 30 | M | HT, DM, chronic kidney disease, glaucoma, and obesity | ND | Abdominal flank pain and shortness of breath | ND | Yes | ND | Yes | ND | LBBB | — | — | Yes | Remdesivir and convalescent plasma | Dexamethasone | No | — | ND | Alive |

| 83 | Othenin-Girard et al. | 2020 [73] | 22 | M | None | ND | Asthenia, chills, diffuse myalgia, abdominal pain, and diarrhea | 5 | No | ND | Yes | ND | CAVB | — | A severe myocardial inflammation with several foci of myocyte necrosis | Yes | — | Methylprednisolone, IVIG, tocilizumab, and cyclophosphamide | VA-ECMO | 5 | Recovered but not in detail | Alive |

| 84 | Albert et al. | 2020 [74] | 49 | M | None | ND | Fevers, myalgias, and dyspnea | 14 | No | 20 | ND | Yes | None | — | Mild infiltration of mononuclear cells in the endocardium and myocardium with >14 inflammatory cells per mm2 indicating myocarditis | Yes | No | Methylprednisolone and IVIG | VA-ECMO Impella CP |

4 | Normal | Alive |

| 85 | Salamanca et al. | 2020 [75] | 44 | M | None | ND | Dyspnea and syncope | 7 | Yes | 15 | Yes | No | CAVB | Diffuse edema with slightly less involvement of the inferolateral wall on T2 weighted image. T1 mapping with diffuse increase of native T1 | Isolated interstitial infiltrate with lymphocytes CD3+ | Yes | No | No | VA-ECMO IABP |

6 | LVEF 75% | Alive |

| 86 | Khatri and Wallach | 2020 [76] | 50 | M | HT and ischemic stroke | ND | Fevers, chills, generalized malaise, nonproductive cough, and dyspnea | 4 | Yes | ND | Yes | ND | None | — | — | Yes | Hydroxychloroquine and methylene blue | Methylprednisolone and IVIG | No | — | No | Dead |

| 87 | Bernal-Torres et al. | 2020 [77] | 38 | F | None | ND | Palpitation and general malaise | 3 | Yes | 30 | Yes | ND | None | Inflammatory manifestations | — | Yes | Hydroxychloroquine, lopinavir, and ritonavir | Methylprednisolone and IVIG | No | — | LVEF 60% | Alive |

| 88 | Chitturi et al. | 2020 [78] | 65 | F | HT, DM, HL, obesity, transient ischaemic attack, and breast cancer | ND | Fever, cough, and shortness of breath | 14 | Yes | 25 | Yes | No | None | — | — | Yes | No | Hydrocortisone and tocilizumab | No | — | LVEF 64% | Alive |

| 89 | Zeng et al. | 2020 [79] | 63 | M | Allergic cough | ND | Fever, shortness of breath, and chest tightness | ND | Yes | 32 | No | ND | ND | — | — | Yes | Lopinavir and ritonavir | Methylprednisolone, IVIG, and interferon α-1b | VA-ECMO | — | LVEF 68% | Dead |

| 90 | Singhavi et al. | 2020 [80] | 20 | M | None | ND | Fever | 1 | No | 30 | No | Yes | ND | — | — | Yes | ND | Methylprednisolone | No | — | ND | Alive |

| 91 | Naneishvili et al. | 2020 [81] | 44 | F | None | ND | Fever, lethargy, muscle aches, and syncope | 3 | Yes | 37 | Yes | Yes | AF | — | — | Yes | No | Methylprednisolone | No | — | Normal | Alive |

| 92 | Chao et al. | 2020 [82] | 49 | M | None | ND | Fever and cough | ND | Yes | 40 | No | No | RBBB | — | — | Yes | Hydroxychloroquine | Tocilizumab | VV-ECMO | 12 | LVEF 55% | Alive |

| 93 | Yan et al. | 2020 [83] | 44 | F | Obesity | ND | Fever, cough, and dyspnea | 7 | Yes | 40 | No | No | None | — | Mild myxoid edema, mild myocyte hypertrophy, and focal nuclear pyknosis. Rare foci with few scattered CD45+ lymphocytes | Yes | Hydroxychloroquine | Tocilizumab | No | — | ND | Dead |

| 94 | Kesici et al. | 2020 [84] | 2 | M | None | ND | Nausea, vomiting, and poor oral intake | ND | Yes | ND | Yes | No | None | — | — | Yes | ND | ND | VA-ECMO | — | — | Dead |

| 95 | Garot et al. | 2020 [85] | 18 | M | None | ND | Cough, fever, fatigue, and myalgias | ND | Yes | 30 | Yes | Yes | None | Strated nodular subepicardial enhancement of the LV basal posterolateral wall on late gadolinium enhancement images | — | Yes | Hydroxychloroquine | No | No | — | LVEF 54% | Alive |

| 96 | Coyle et al. | 2020 [86] | 57 | M | HT | ND | Shortness of breath, fevers, cough, myalgias, decreased appetite, nausea, and diarrhea | 7 | Yes | 35–40 | No | No | None | Diffuse biventricular and biatrial edema with a small area of late gadolinium enhancement | — | Yes | Hydroxychloroquine and AT-001 (caficrestat) | Methylprednisolone and tocilizumab | No | — | LVEF 82% | Alive |

| 97 | Richard et al. | 2020 [87] | 28 | F | DM, asthma, depression, and intravenous drug use | ND | Lethargy | ND | Yes | 26–30 | Yes | Yes | RBBB | Myocardial necrosis, fibrosis, and hyperemia, indicating myocarditis | — | Yes | No | Methylprednisolone | Impella | 4 | LVEF >55% | Alive |

| 98 | Pascariello et al. | 2020 [88] | 19 | M | Autistic spectrum disorder | ND | Fever, cough, diarrhea, and vomitting | 3 | Yes | 15–20 | ND | ND | None | — | — | Yes | Hydroxychloroquine, remdesivir, and oseltamivir | Dexamethasone | No | — | LVEF 50% | Alive |

| 99 | Shah et al. | 2020 [89] | 19 | M | None | ND | Fever, generalized weakness, cough, and shortness of breath | 7 | Yes | 24 | No | No | None | — | — | Yes | Hydroxychloroquine | Methylprednisolone, IVIG, and tocilizumab | No | — | LVEF 62% | Alive |

| 100 | Veronese et al. | 2020 [90] | 51 | F | Thalassemia minor | ND | Fever, dyspnea, and palpitations | 10 | No | 30 | No | Yes | VT, RBBB | Short tau inversion recovery sequences revealed diffuse increased signal intensity suggestive of diffuse edema. Transmural late gadolinium enhancement involved LV basal-lateral and basal-inferior walls | Diffuse lymphocytic inflammatory infiltrates | Yes | No | Methylprednisolone | VA-ECMO IABP |

6 | Fully | Alive |

| 101 | Hussain et al. | 2020 [91] | 51 | M | HT | ND | Fever, cough, fatigue, and dyspnea | ND | Yes | 20 | No | No | None | — | — | Yes | Hydroxychloroquine | Methylprednisolone | No | — | Not recovered | Alive (ongoing treatment) |

| 102 | Gill et al. | 2020 [92] | 65 | F | HT, DM, and breast cancer | ND | Shortness of breath and chest pain | ND | Yes | 25 | No | No | None | — | — | Yes | — | — | IABP | — | No | Dead |

| 103 | Gill et al. | 2020 [92] | 34 | F | None | ND | Shortness of breath, chest pain, and weakness | ND | No | 20 | Yes | No | None | — | — | Yes | — | Methylprednisolone | VA-ECMO | 4 | LVEF 60% | Alive |

| 104 | Fried et al. | 2020 [93] | 64 | F | HT, HL | ND | Chest pressure | 2 | No | 30 | Yes | Yes | None | — | — | Yes | Hydroxychloroquine | No | IABP | 7 | LVEF 50% | Alive |

| 105 | Craver et al. | 2020 [94] | 17 | M | None | ND | Headache, dizziness, nausea, and vomiting | 2 | No | ND | ND | ND | Asystole | — | Diffuse inflammatory infiltrates composed of lymphocytes, macrophages, with prominent eosinophils | ND | — | — | — | — | — | Dead |

| 106 | Irabien-Ortiz et al. | 2020 [95] | 59 | F | HT, cervical degenerative arthropathy, chronic lumbar radiculopathy, lymph node tuberculosis, and migraine | ND | Fever and chest pain | 5 | No | Preserved | Yes | Yes | Asystole | — | — | Yes | IFN B, lopinavir, and ritonavir | Methylprednisolone and IVIG | VA-ECMO IABP |

ND | Fully | Alive (ongoing treatment) |

| 107 | Tavazzi et al. | 2020 [96] | 69 | M | ND | ND | Dyspnoea, persistent cough, and weakness | 4 | Yes | 25 | No | No | ND | — | Low grade interstitial and endocardial inflammation | Yes | — | — | VA-ECMO IABP |

5 | Not recovered | Dead |

| 108 | Gomila-Grange et al. | 2020 [97] | 39 | M | ND | ND | Fever, right flank pain, and diarrhea | 6 | Yes | 20 | Yes | No | None | — | — | Yes | Hydroxychloroquine | Tocilizumab | No | — | Normal | Alive |

AF, atrial fibrillation; CAVB, complete atrioventricular block; CMR, cardiovascular magnetic resonance; DM, diabetes mellitus; F, female; HL, hyperlipidemia; HT, hypertension; IABP, intra-aortic balloon pumping; IRBBB, incomplete right bundle branch block; IVIG, intravenous immunoglobulin; LGE, late gadolinium enhancement; LV, left ventricle; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; LVSF, left ventricular shortening fraction; LVWT, left ventricular wall thickening; M, male; MCS; mechanical circulatory support; ND, not described; NSVT, nonsustained ventricular tachycardia; PE, pericardial effusion; PEA, pulseless electrical activity; PVC, premature ventricular contraction; VA/VV-ECMO, veno-arterial/veno-venous extracorporeal membrane oxygenation; VF, ventricular fibrillation; and VT, ventricular tachycardia.

Table 2.

Demographics and clinical data of studied patients. All descriptive parameters are obtained from the original papers.

| Demographic variables | |

|

| |

| N = 108 | |

| Age (years) | 34.8 ± 18.1 (range 0–72) |

| ≤20 | 30 (27.8%) |

| ≥60 | 10 (9.3%) |

| Sex | |

| Male | 67 (62.0%) |

| Female | 41 (38.0%) |

| Comorbidities | |

| Not described | 21 |

| None | 48 |

| Hypertension | 12 |

| Obesity | 11 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 8 |

| Asthma (including allergic cough) | 4 |

| Heart diseases | 4 |

| Gynecologic diseases | 3 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 3 |

| Connective tissue disorders | 3 |

| Blood disorders | 2 |

| Mental disorders | 2 |

|

| |

| Dose of vaccination | N = 19 |

| 0 | 15 |

| 1 | 2 |

| 2 | 1 |

| 3 | 1 |

| ≥4 | 0 |

|

| |

| Clinical data | |

|

| |

| Initial symptoms | N = 98 (excluding 10 patients with relevant information unavailable) |

| Fever | 51 (52.0%) |

| Dyspnea or shortness of breath | 45 (45.9%) |

| Diarrhea | 20 (20.4%) |

| Chest pain | 20 (20.4%) |

| Cough | 19 (19.4%) |

| Vomiting | 17 (17.3%) |

| Abdominal pain | 13 (13.3%) |

| Asthenia | 9 (9.2%) |

| Fatigue | 9 (9.2%) |

| Weakness | 5 (5.1%) |

| Lethargy | 5 (5.1%) |

| Loss of appetite | 3 (3.1%) |

|

| |

| Concurrent with pneumonia | N = 43 |

| 2020 | 20 |

| 2021 | 20 |

| 2022 | 3 |

|

| |

| Left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) | N = 108 |

| LVEF ≤ 20% | 48 (52.2%) |

| 20 < LVEF ≤ 30% | 31 (33.7%) |

| 30 < LVEF ≤ 40% | 7 (7.6%) |

| 40 < LVEF ≤ 50% | 3 (3.3%) |

| 50% < LVEF including preserved or normal | 3 (3.3%) |

| Unclassified | 16 |

|

| |

| Pericardial effusion | N = 108 |

| Yes | 45 (65.2%) |

| No | 24 (34.8%) |

| Not described | 39 |

| Left ventricular wall thickening | N = 108 |

| Yes | 24 (40.7%) |

| No | 35 (59.3%) |

| Not described | 49 |

|

| |

| Arrhythmia | N = 40 |

| VT | 11 |

| Asystole/cardiac arrest | 6 |

| PEA | 6 |

| VF | 5 |

| RBBB | 5 |

| AF | 4 |

| CAVB | 4 |

| Long QT | 2 |

| Ectopic wandering atrial pacemaker | 1 |

|

| |

| Diagnostic modality | N = 49 |

| Only CMR | 14 |

| Only biopsy | 23 |

| Both CMR and biopsy | 12 |

|

| |

| Mechanical circulatory support | N = 67 |

| ECMO | 56 (83.6%) |

| Impella | 19 (28.4%) |

| IABP | 12 (12.9%) |

| RVAD | 2 (3.0%) |

| Combination | 20 (29.9%) |

|

| |

| Outcome | N = 107 (excluding 1 patient with relevant information unavailable) |

| Alive | 83 (77.6%) |

| Dead | 24 (22.4%) |

AF, atrial fibrillation; CAVB, complete atrioventricular block; CMR, cardiovascular magnetic resonance; ECMO, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation; IABP, intra-aortic balloon pumping; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; PEA, pulseless electrical activity; RVAD, right ventricular assist device; RBBB, right bundle branch block; VF, ventricular fibrillation; and VT, ventricular tachycardia.

Myocarditis with concurrent pneumonia occurred in 43 cases (45%), of which 20 were in 2020 and 2021, and only 3 after 2021.

Among the 92 patients whose left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) on echocardiography at admission was available, 48 (52.2%) were classified as having LVEF ≤ 20%, 31 with 20 < LVEF ≤ 30% (33.7%), 7 with 30 < LVEF ≤ 40% (7.6%), 3 with 40 < LVEF ≤ 50% (3.3%), and 3 with 50% < LVEF (3.3%), which includes preserved or normal ejection fraction. The patients with 50% < LVEF were associated with the presence of ectopic wandering atrial pacemaker or asystole. Pericardial effusions were observed in 45 patients (65.2%) and left ventricular wall thickening was identified in 24 (40.7%).

Regarding arrhythmia, lethal arrhythmias, namely, ventricular tachycardia and ventricular fibrillation, occurred in 11 and 5 patients, respectively. Cardiac arrest, presented as pulseless electrical activity or asystole, occurred in 6 and 6 cases, respectively. Identified cardiac conduction defects included right bundle branch block (n = 5) and complete atrioventricular block (n = 4).

The diagnosis of myocarditis was made solely by CMR (n = 14, 13.0%), biopsy (n = 23, 21.3%), or both (n = 12, 11.1%), whereas the remaining cases (n = 659, 54.6%) were clinically diagnosed.

Antiviral treatment was administered in 35 cases, whereas immunomodulatory therapy was performed in 78; the most common immunomodulatory therapy was steroid administration (n = 72), followed by intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) (n = 38), tocilizumab (n = 13), and anakinra (n = 6).

Among the 93 patients whose catecholamine use history was available, most (n = 91, 97.8%) underwent catecholamine use. MCS was employed in 67 cases (62.0%). The type of MCS used was extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) (n = 56, 83.6%), percutaneous ventricular assist device (Impella®) (n = 19, 28.4%), intra-aortic balloon pumping (IABP) (n = 12, 12.9%), or right ventricular assist device (RVAD) (n = 2, 3.0%); combination of devices occurred in 20 cases (29.9%). The average duration of MCS was 7.7 ± 3.8 days. Cardiac function recovered to normal (LVEF ≥ 50%) in 67 cases. Of the 76 surviving patients whose cardiac function was available for follow-up, 65 (85.5%) recovered normally.

Finally, the overall mortality rate was 22.4%, and the recovery rate was 77.6% (alive: 83 patients, dead: 24 patients; outcome not described: 1 patient). One patient underwent a heart transplant.

4. Discussion

In this systematic review, we summarized the features of fulminant myocarditis with SARS-CoV-2 infection, including patients' demographics, comorbidities, history of vaccination, symptoms, clinical characteristics, treatments, and outcomes. To our knowledge, this is the first comprehensive review analyzing all cases of fulminant myocarditis related to SARS-CoV-2 infection.

4.1. Patients' Clinical Characteristics

The incidence of acute myocarditis in the general population is estimated to be approximately 10–22 per 100,000 people [98, 99]. The estimation of the mean prevalence of SARS-CoV-2 infection-related acute myocarditis was reportedly between 0.0012 and 0.0057 among hospitalized patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection [3]. Although the incidence of fulminant myocarditis is less well-defined, the condition is considered quite rare. Our systematic review revealed that only 108 cases of fulminant myocarditis with SARS-CoV-2 infection were reported between 2020 and 2022.

The mean age of the 108 patients with myocarditis with SARS-CoV-2 infection was 35 years, and 62% of them were male. Myocarditis has been reported to occur more frequently in males, with a male to female ratio around 1.5 : 1–1.7 : 1; therefore, the current review was consistent with previous reports [100, 101]. Surprisingly, the case of a 3-day-old newborn with myocarditis was reported; if mothers do not possess antibodies against COVID-19, newborns can be infected with the virus [38]. Conversely, the incidence was not so high among the elderly. Myocarditis typically occurs between 3 and 9 days after the onset of COVID-19 symptoms. The time course of the occurrence of myocarditis was similar to other viral infections, such as influenza [102].

4.2. Pathophysiology and Comorbidities

The possible pathophysiology of COVID-19 myocarditis is thought to involve the direct invasion of cardiac myocytes by the SARS-CoV-2 virus, and indirect cardiac injury due to increased release of cytokines and inflammatory pathways [103, 104]. The densities of CD68+ macrophages and CD3+ lymphocytes have been reported to be relatively high in myocarditis, from the results of EMB; additionally, myocardial macrophage and lymphocyte densities displayed a positive correlation with the symptom duration of myocarditis [105]. Thus, cytokines and inflammatory pathways are likely to play key roles in myocarditis' pathogenesis.

Previous reviews described that patients with cardiovascular comorbidities, such as hypertension, diabetes, obesity, hyperlipidemia, and ischemic heart disease were at a higher risk of developing COVID-19 myocarditis [104]. The results of our analysis revealed that hypertension, obesity, and diabetes mellitus were the most common comorbidities among patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection-related “fulminant” myocarditis. The association between hypertension and inflammation is well-known; inflammatory responses increase the disease's severity and patients' complications [106]. Obesity is associated with adipose tissues, chronic low-grade inflammation, and immune dysregulation with hypertrophy and hyperplasia of adipocytes and overexpression of proinflammatory cytokines. Increased epicardial and pericardial thickness can be observed on echocardiography of patients with myocarditis and has been attributed to an increased amount of epicardial adipose tissue (EAT), a highly inflammatory reservoir with dense macrophage infiltration and increased levels of proinflammatory cytokines, such as interleukin 6 (IL-6) [107]. EAT could fuel COVID-19-induced cardiac injury and myocarditis [108]. The EAT volume, as well as the volume of visceral adipose tissue, is increased in obese patients; therefore, obesity is also one of the major risk factors for myocarditis [109].

4.3. Vaccination and Variant of the Virus

Regarding vaccination, myocarditis following vaccination has been reported, with an incidence of myocarditis/pericarditis of 4.5 per 100,000 vaccinations across all doses [110]. Our review revealed that most cases of fulminant myocarditis caused by COVID-19 did not receive vaccination; however, vaccination's number was limited, with the accumulation of more findings being expected in the future.

The incidence of concurrent myocarditis and pneumonia has decreased over time, probably because of the change of viral variant and the widespread use of vaccines. The severity of COVID-19 is milder with the Omicron variant, compared with Alpha and Delta variants, identified by whole genome sequencing. In addition, Omicron has difficulty replicating in the lungs compared to the Delta variant, which may explain the reduced respiratory impairment with the Omicron [111, 112].

4.4. Clinical Presentation

The most reported symptoms were fever, dyspnea, shortness of breath, chest pain, and cough. These are typical manifestations in myocarditis as well as in COVID infections; accordingly, reaching an appropriate diagnosis can be challenging [113].

Regarding LVEF at admission, more than 90% of the patients with fulminant myocarditis were classified as having heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (LVEF ≤ 40%). Notably, regardless of the severity of the acute myocardial injury, the cardiac function of most patients returned to normal if they survived; our review showed that 85.5% of the patients recovered to a normal cardiac function. In previous reports of acute cardiac injury in patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection, 89% of the patients presented a LVEF of approximately 67%, while 26% developed myocarditis-like scars [114]. The long-term effect of such cardiac injury data is still unknown, and waiting for the follow-up data is warranted.

The overall incidence of arrhythmia in patients with COVID-19 was reported as 16.8%, of which approximately 8.2% constituted atrial arrhythmias (atrial fibrillation or atrial flutter), 10.8% conduction disorders, 8.6% ventricular tachycardia (ventricular tachycardia, tachycardia/ventricular flutter/ventricular fibrillation), and 12% unclassified arrhythmias [115]. Our review revealed that lethal arrhythmias or cardiac arrest occurred in a total of 26 cases with fulminant myocarditis (24.1%), a rate higher than previously reported. These arrhythmias often required MCS, and 62% of the patients in our review received MCS.

4.5. Diagnosis

CMR and EMB are essential myocarditis diagnostic tests. However, due to the risk of infection, such were sometimes not performed in patients with COVID-19. Additionally, CMR is usually performed after myocarditis stabilization, in a subacute phase. According to the revised Lake Louise Criteria of 2018, CMR-based diagnosis of myocarditis is based on at least one T1-based criterion (increased myocardial T1 relaxation times, extracellular volume fraction, or late gadolinium enhancement) with the presence of at least one T2-based criterion (increased myocardial T2 relaxation times, visible myocardial edema, or increased T2 signal intensity ratio). Additionally, supportive criteria include the presence of pericardial effusion in cine CMR images or high signal intensity of the pericardium in late gadolinium enhancement images, T1-mapping or T2-mapping, and systolic left ventricular wall motion abnormality in cine CMR images [7]. Diagnosis of myocarditis using the Lake Louise Criteria has a 91% specificity and 67% sensitivity. CMR can be used as a primary diagnostic technique for screening COVID-19-associated myocarditis in the absence of contraindications [116].

EMB remains the gold standard invasive technique in diagnosing myocarditis, and, especially for fulminant myocarditis with a fatal outcome, autopsy is also an useful diagnostic tool [117]. The sequence of myocardial damage after SARS-CoV-2 infection obtained from autopsy reviews varied. Raman et al. reported that only four patients (5%) presented suspected cardiac injury in an early autopsy series of 80 consecutive SARS-CoV-2 positive cases; two patients had comorbidities and died of sudden cardiac death, one presented acute myocardial infarction, and another showed right ventricular lymphocytic infiltrates. These results suggested that extensive myocardial injury as a major cause of death may be infrequent [118]. Basso et al. investigated cardiac tissue from the autopsies of 21 consecutive patients with COVID-19 assessed by cardiovascular pathologists. Myocarditis (characterized as lymphocytic infiltration as well as myocyte necrosis) was seen in 14% of the cases, infiltration of interstitial macrophage in 86%, and pericarditis as well as right-sided ventricular damage in 19% [119]. Halushka and Vander Heide reviewed 22 publications that described the autopsy outcomes of 277 affected individuals. Lymphocytic myocarditis was mentioned in 7.2% of cases, however, only 1.4% met the strict histopathological criteria for myocarditis, implying that proper myocarditis was uncommon; such cases comprised autopsies from patients with COVID-19 without a definitive myocarditis diagnosis before death [120]. Our review showed that diffuse lymphocytic inflammatory infiltrates with edema was the most common finding, and a few cases were associated with eosinophilic infiltrations in patients with confirmed myocarditis with SARS-CoV-2 infection.

In addition, it is difficult for clinicians to differentiate myocarditis with pneumonia from myocarditis with acute pulmonary edema. The distinction between myocarditis with COVID-19 pneumonia and myocarditis with acute pulmonary edema is primarily based on imaging findings and laboratory markers. Both conditions often present with similar symptoms such as fever, cough, and dyspnea. However, patients with myocarditis and pneumonia often have imaging studies that show localized pulmonary infiltrates or consolidation. The hallmark of COVID-19 pneumonia is the presence of ground-glass opacities, typically with a peripheral and subpleural distribution. In addition, the involvement of multiple lobes, particularly the lower lobes, has been reported in most cases of COVID-19 pneumonia [121]. In contrast, myocarditis with acute pulmonary edema typically presents with bilateral alveolar infiltrates indicating fluid overload [121]. Elevated biomarkers of heart failure such as brain natriuretic peptide (BNP) or N-terminal pro-BNP also suggest myocarditis with pulmonary edema [113]. Ultimately, the distinction is made by a combination of symptoms, specific imaging features, and the presence of biomarkers to guide the appropriate management of each condition.

4.6. Treatment

The management of myocarditis with SARS-CoV-2 is currently controversial and not yet established. Both American and European guidelines propose a management similar to that of other viral myocarditis and heart failure treatment [122, 123]. Hospitalization is recommended for patients with confirmed myocarditis that is either mild or moderate in severity, ideally at an advanced heart failure center. Patients with fulminant myocarditis should be managed at centers with an expertise in advanced heart failure, MCS, and other advanced therapies [122]. European consensus suggested that escalation to MCS should be carefully weighed against the development of coagulopathy associated with COVID-19 and the need for specific treatments for acute lung injury, such as prone position; when MCS is required, ECMO should be the preferred temporary technique, because of its oxygenation capabilities [123].

Regarding the specific treatment of COVID-19-associated myocarditis, no compelling evidence exists to support the use of immunomodulatory therapy, including corticosteroids and IVIG [123]. However, some authors indicate a possible benefit of high-dose steroids and IVIG, as the condition can be considered an immune-mediated myocarditis. Corticosteroids are indicated when respiratory involvement is present and have been administered to patients who showed favorable clinical outcomes [124, 125]. For those with pericardial involvement, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs may be used to help alleviate chest pain and inflammation. Regarding IVIG in myocarditis not associated with COVID-19, a meta-analysis reported improved survival and ventricular function with its administration with corticosteroids, especially in acute fulminant myocarditis [126]. Other immunomodulatory therapies, such as tocilizumab and anakinra, are currently being studied for SARS-CoV-2-associated myocarditis [122, 127]. Regarding antiviral treatment, none demonstrated efficacy at reducing COVID-19 mortality [128]. In this review, remdesivir was employed in 14 cases, and four of them culminated in death. Lopinavir/ritonavir were used in 4 cases, all of which survived. As for MCS, a large retrospective review that analyzed 147 patients with a diagnosis of acute myocarditis treated with ECMO from 1995 to 2011 showed that survival to hospital discharge was 61%, confirming ECMO as a useful therapy in adults with myocarditis with cardiogenic shock and highlighting its high in-hospital mortality [129]. Inadequate aortic valve opening or lack of left ventricular support could occasionally occur with single ECMO therapy; therefore, those cases may require dual cardiac assist devices to ensure adequate ventricular unloading, such as ECMO with Impella® or with IABP.

4.7. Prognosis and Outcomes

Rathore et al. reported that approximately 38% of the patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection-related myocarditis required vasopressor support; out of 28 patients, 82% survived, whereas 18% died [117]. Furthermore, Urban et al. reported that death was the outcome in 11 out of 63 cases (17%) [130]. Our review showed that the overall mortality rate was 22.4%, and the recovery rate was 77.6%, which were worse outcomes than the previously reported, because of our focus on fulminant myocarditis. However, reported cases are usually severe and complicated, which may constitute a bias for reporting a higher mortality.

4.8. Limitations

This systematic review had several limitations. First, our study is retrospective and descriptive in nature. In some cases, the myocarditis diagnosis was based on clinical expertise. CRM image acquisition was not standardized and relied on local protocols. A possibility of publication bias also exists, in which fatal forms of SARS-CoV-2 infection-associated myocarditis may not have been reported or identified due to its challenging diagnosis. Additionally, only published data including inpatient cases were included in the study. Clinical evaluations such as subjective symptoms reporting and many of the objective values may vary. Lastly, the clinical workup was heterogeneous.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, we reviewed previously reported cases of fulminant myocarditis with SARS-CoV-2 infection. We summarized an international experience with this severe condition that was accumulated for the last three years, since the start of this pandemic. We demonstrated that SARS-CoV-2 infection-associated fulminant myocarditis required MCS in 62% of the cases and resulted in death of one out of five patients, therefore demonstrating its high mortality. Conversely, most of the surviving patients recovered to normal systolic functions. Therefore, rapid bridging therapy including immunomodulatory therapies and/or MCS, if appropriate, may play an important role for improving outcomes in patients with fulminant myocarditis with SARS-CoV-2 infection.

Abbreviations

- CMR:

Cardiac magnetic resonance

- COVID-19:

Coronavirus disease 2019

- EAT:

Epicardial adipose tissue

- ECMO:

Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation

- EMB:

Endomyocardial biopsy

- IABP:

Intra-aortic balloon pumping

- IL-6:

Interleukin 6

- IVIG:

Intravenous immunoglobulin

- LVEF:

Left ventricular ejection fraction

- MCS:

Mechanical circulatory support

- PRISMA:

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis

- RVAD:

Right ventricular assist device

- SARS-CoV-2:

Acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Authors' Contributions

RO, TI, and HK conducted article search, and RO drafted the manuscript. TI, KA, HK, SO, and YK revised the manuscript critically. All authors contributed substantially to the conception of this review and in drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content. Finally, all authors approved the version to be published.

References

- 1.Dong E., Du H., Gardner L. An interactive web-based dashboard to track COVID-19 in real time. The Lancet Infectious Diseases . 2020;20(5):533–534. doi: 10.1016/s1473-3099(20)30120-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sarkar A., Omar S., Alshareef A., et al. The relative prevalence of the Omicron variant within SARS-CoV-2 infected cohorts in different countries: a systematic review. Human Vaccines and Immunotherapeutics . 2023;19(1) doi: 10.1080/21645515.2023.2212568.2212568 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ammirati E., Lupi L., Palazzini M., et al. Prevalence, characteristics, and outcomes of COVID-19-associated acute myocarditis. Circulation . 2022;145(15):1123–1139. doi: 10.1161/circulationaha.121.056817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mirabel M., Luyt C. E., Leprince P., et al. Outcomes, long-term quality of life, and psychologic assessment of fulminant myocarditis patients rescued by mechanical circulatory support. Critical Care Medicine . 2011;39(5):1029–1035. doi: 10.1097/ccm.0b013e31820ead45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liberati A., Altman D. G., Tetzlaff J., et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: explanation and elaboration. British Medical Journal . 2009;339 doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2700.b2700 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bozkurt B., Colvin M., Cook J., et al. Current diagnostic and treatment strategies for specific dilated cardiomyopathies: a scientific statement from the American heart association. Circulation . 2016;134(23):e579–e646. doi: 10.1161/cir.0000000000000455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ferreira V. M., Schulz-Menger J., Holmvang G., et al. Cardiovascular magnetic resonance in nonischemic myocardial inflammation: expert recommendations. Journal of the American College of Cardiology . 2018;72(24):3158–3176. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2018.09.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Noone S., Flinspach A. N., Fichtlscherer S., Zacharowski K., Sonntagbauer M., Raimann F. J. Severe COVID-19-associated myocarditis with cardiogenic shock- management with assist devices- a case report & review. BioMedical Central Anesthesiology . 2022;22(1):p. 385. doi: 10.1186/s12871-022-01890-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hoang B. H., Tran H. T., Nguyen T. T., et al. A successful case of cardiac arrest due to acute myocarditis with COVID-19: 120 minutes on manual cardiopulmonary resuscitation then veno-arterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. Prehospital and Disaster Medicine . 2022;37(6):843–846. doi: 10.1017/s1049023x2200139x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.De Smet M. A. J., Fierens J., Vanhulle L., et al. SARS-CoV-2-related Multisystem Inflammatory Syndrome in Adult complicated by myocarditis and cardiogenic shock. European Society of Cardiology Heart Failure . 2022;9(6):4315–4324. doi: 10.1002/ehf2.14126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Usui E., Nagaoka E., Ikeda H., et al. Fulminant myocarditis with COVID-19 infection having normal C-reactive protein and serial magnetic resonance follow-up. European Society of Cardiology Heart Failure . 2023;10(2):1426–1430. doi: 10.1002/ehf2.14228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ardiana M., Aditya M. Acute perimyocarditis- an ST-elevation myocardial infarction mimicker: a case report. American Journal of Case Reports . 2022;23 doi: 10.12659/ajcr.936985.e936985 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ya’Qoub L., Lemor A., Basir M. B., Alqarqaz M., Villablanca P. A visual depiction of left ventricular unloading in veno-arterial ExtraCorporeal membrane oxygenation with Impella. Journal of Invasive Cardiology . 2022;34(11):p. E825. doi: 10.25270/jic/22.00027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ajello S., Calvo F., Basso C., Nardelli P., Scandroglio A. M. Full myocardial recovery following COVID-19 fulminant myocarditis after biventricular mechanical support with BiPella: a case report. European Heart Journal- Case Reports . 2022;6(9) doi: 10.1093/ehjcr/ytac373.ytac373 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Asakura R., Kuroshima T., Kokita N., Okada M. A case of COVID-19-associated fulminant myocarditis successfully treated with mechanical circulatory support. Clinical Case Reports . 2022;10(9) doi: 10.1002/ccr3.6185.e6185 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nakatani S., Ohta-Ogo K., Nishio M., et al. Microthrombosis as a cause of fulminant myocarditis-like presentation with COVID-19 proven by endomyocardial biopsy. Cardiovascular Pathology . 2022;60 doi: 10.1016/j.carpath.2022.107435.107435 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Callegari A., Klingel K., Kelly-Geyer J., Berger C., Geiger J., Knirsch W. Difficulties in diagnosis of SARS-CoV-2 myocarditis in an adolescent. Swiss Medical Weekly . 2022;152(2930) doi: 10.4414/smw.2022.w30214.w30214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Phan P. H., Nguyen D. T., Dao N. H., et al. Case report: successful treatment of a child with COVID-19 reinfection-induced fulminant myocarditis by cytokine-adsorbing oXiris® hemofilter continuous veno-venous hemofiltration and extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. Front Pediatr . 2022;10 doi: 10.3389/fped.2022.946547.946547 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Carrasco-Molina S., Ramos-Ruperto L., Ibanez-Mendoza P., et al. Cardiac involvement in adult multisystemic inflammatory syndrome related to COVID-19. Two case reports. Journal of Cardiology Cases . 2022;26(1):24–27. doi: 10.1016/j.jccase.2022.01.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kohli U., Meinert E., Chong G., Tesher M., Jani P. Fulminant myocarditis and atrial fibrillation in child with acute COVID-19. Journal of Electrocardiology . 2022;73:150–152. doi: 10.1016/j.jelectrocard.2020.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bhardwaj A., Kirincich J., Rampersad P., Soltesz E., Krishnan S. Fulminant myocarditis in COVID-19 and favorable outcomes with VA-ECMO. Resuscitation . 2022;175:75–76. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2022.04.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mejia E. J., O’Connor M. J., Samelson-Jones B. J., et al. Successful treatment of intracardiac thrombosis in the presence of fulminant myocarditis requiring ECMO associated with COVID-19. The Journal of Heart and Lung Transplantation . 2022;41(6):849–851. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2022.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rajpal S., Kahwash R., Tong M. S., et al. Fulminant myocarditis following SARS-CoV-2 infection: JACC patient care pathways. Journal of the American College of Cardiology . 2022;79(21):2144–2152. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2022.03.346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Buitrago D. H., Munoz J., Finkelstein E. R., Mulinari L. A case of fulminant myocarditis due to COVID-19 in an adolescent patient successfully treated with venous arterial ECMO as a bridge to recovery. Journal of Cardiac Surgery . 2022;37(5):1439–1443. doi: 10.1111/jocs.16313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Thomson A., Totaro R., Cooper W., Dennis M. Fulminant Delta COVID-19 myocarditis: a case report of fatal primary cardiac dysfunction. European Heart Journal- Case Reports . 2022;6(4) doi: 10.1093/ehjcr/ytac142.ytac142 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rodriguez Guerra M. A., Lappot R., Urena A. P., Vittorio T., Roa Gomez G. COVID-induced fulminant myocarditis. Cureus . 2022;14(4) doi: 10.7759/cureus.23894.e23894 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Verma A. K., Olagoke O., Moreno J. D., et al. SARS-CoV-2-Associated myocarditis: a case of direct myocardial injury. Circulation: Heart Failure . 2022;15(3) doi: 10.1161/circheartfailure.120.008273.e008273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Edwards J. J., Harris M. A., Toib A., Burstein D. S., Rossano J. W. Asymmetric septal edema masking as hypertrophy in an infant with COVID-19 myocarditis. Progress in Pediatric Cardiology . 2022;64 doi: 10.1016/j.ppedcard.2021.101464.101464 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Aldeghaither S., Qutob R., Assanangkornchai N., et al. Clinical and histopathologic features of myocarditis in multisystem inflammatory syndrome (Adult)-Associated COVID-19. Critical Care Explorations . 2022;10(2) doi: 10.1097/cce.0000000000000630.e0630 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Valiton V., Bendjelid K., Pache J. C., Roffi M., Meyer P. Coronavirus disease 2019-associated coronary endotheliitis and thrombotic microangiopathy causing cardiogenic shock: a case report. European Heart Journal- Case Reports . 2022;6(2) doi: 10.1093/ehjcr/ytac061.ytac061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ismayl M., Abusnina W., Thandra A., et al. Delayed acute myocarditis with COVID-19 infection. Baylor University Medical Center Proceedings . 2022;35(3):366–368. doi: 10.1080/08998280.2022.2030189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yalcinkaya D., Yarlioglues M., Yigit H., Caydere M., Murat S. N. Cardiac mobile thrombi formation in an unvaccinated young man with SARS-CoV-2 associated fulminant eosinophilic myocarditis. European Heart Journal- Case Reports . 2022;6(2) doi: 10.1093/ehjcr/ytac036.ytac036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nagata M., Sakaguchi K., Kusaba K., Tanaka Y., Shimizu T. A case of multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children with cardiogenic shock. Pediatrics International: Official Journal of the Japan Pediatric Society . 2022;64(1) doi: 10.1111/ped.15304.e15304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nishioka M., Hoshino K. Coronavirus disease 2019-related acute myocarditis in a 15-year-old boy. Pediatrics International: Official Journal of the Japan Pediatric Society . 2022;64(1) doi: 10.1111/ped.15136.e15136 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shahrami B., Davoudi-Monfared E., Rezaie Z., et al. Management of a critically ill patient with COVID-19-related fulminant myocarditis: a case report. Respiratory Medicine Case Reports . 2022;36 doi: 10.1016/j.rmcr.2022.101611.101611 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Menger J., Apostolidou S., Edler C., et al. Fatal outcome of SARS-CoV-2 infection (B1.1.7) in a 4-year-old child. International Journal of Legal Medicine . 2022;136(1):189–192. doi: 10.1007/s00414-021-02687-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vannella K. M., Oguz C., Stein S. R., et al. Evidence of SARS-CoV-2-specific T-cell-mediated myocarditis in a MIS-A case. Frontiers in Immunology . 2021;12 doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.779026.779026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gozar L., Suteu C. C., Gabor-Miklosi D., Cerghit-Paler A., Fagarasan A. Diagnostic difficulties in a case of fetal ventricular tachycardia associated with neonatal COVID infection: case report. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health . 2021;18(23) doi: 10.3390/ijerph182312796.12796 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shen M., Milner A., Foppiano Palacios C., Ahmad T. Multisystem inflammatory syndrome in adults (MIS-A) associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection with delayed-onset myocarditis: case report. European Heart Journal- Case Reports . 2021;5(12) doi: 10.1093/ehjcr/ytab470.ytab470 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ishikura H., Maruyama J., Hoshino K., et al. Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) associated delayed-onset fulminant myocarditis in patient with a history of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection. Journal of Infection and Chemotherapy . 2021;27(12):1760–1764. doi: 10.1016/j.jiac.2021.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Saha S., Pal P., Mukherjee D. Neonatal MIS-C: managing the cytokine storm. Pediatrics . 2021;148(5) doi: 10.1542/peds.2020-042093.e2020042093 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yeleti R., Guglin M., Saleem K., et al. Fulminant myocarditis: COVID or not COVID? Reinfection or co-infection? Future Cardiology . 2021;17(8):1307–1311. doi: 10.2217/fca-2020-0237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gurin M. I., Lin Y. J., Bernard S., et al. Cardiogenic shock complicating multisystem inflammatory syndrome following COVID-19 infection: a case report. BioMedical Central Cardiovascular Disorders . 2021;21(1):p. 522. doi: 10.1186/s12872-021-02304-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fiore G., Sanvito F., Fragasso G., Spoladore R. Case report of cardiogenic shock in COVID-19 myocarditis: peculiarities on diagnosis, histology, and treatment. European Heart Journal-Case Reports . 2021;5(10) doi: 10.1093/ehjcr/ytab357.ytab357 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bemtgen X., Klingel K., Hufnagel M., et al. Case report: lymphohistiocytic myocarditis with severe cardiogenic shock requiring mechanical cardiocirculatory support in multisystem inflammatory syndrome following SARS-CoV-2 infection. Frontiers in Cardiovascular Medicine . 2021;8 doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2021.716198.716198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tseng Y. S., Herron C., Garcia R., Cashen K. Sustained ventricular tachycardia in a paediatric patient with acute COVID-19 myocarditis. Cardiology in the Young . 2021;31(9):1510–1512. doi: 10.1017/s1047951121000792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gaudriot B., Mansour A., Thibault V., et al. Successful heart transplantation for COVID-19-associated post-infectious fulminant myocarditis. European Society of Cardiology Heart Failure . 2021;8(4):2625–2630. doi: 10.1002/ehf2.13326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Menter T., Cueni N., Gebhard E. C., Tzankov A. Case report: Co-occurrence of myocarditis and thrombotic microangiopathy limited to the heart in a COVID-19 patient. Front Cardiovasc Med . 2021;8 doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2021.695010.695010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ghafoor K., Ahmed A., Abbas M. Fulminant myocarditis with ST elevation and cardiogenic shock in a SARS-CoV-2 patient. Cureus . 2021;13(7) doi: 10.7759/cureus.16149.e16149 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Okor I., Sleem A., Zhang A., Kadakia R., Bob-Manuel T., Krim S. R. Suspected COVID-19-induced myopericarditis. The Ochsner Journal . 2021;21(2):181–186. doi: 10.31486/toj.20.0090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tomlinson L. G., Cohen M. I., Levorson R. E., Tzeng M. B. COVID-19-associated multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children presenting uniquely with sinus node dysfunction in the setting of shock. Cardiology in the Young . 2021;31(7):1202–1204. doi: 10.1017/s1047951121000354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sampaio P. P. N., Ferreira R. M., de Albuquerque F. N., et al. Rescue venoarterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation after cardiac arrest in COVID-19 myopericarditis: a case report. Cardiovascular Revascularization Medicine . 2021;28:57–60. doi: 10.1016/j.carrev.2020.09.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Apostolidou S., Harbauer T., Lasch P., et al. Fatal COVID-19 in a child with persistence of SARS-CoV-2 despite extensive multidisciplinary treatment: a case report. Children . 2021;8(7):p. 564. doi: 10.3390/children8070564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kallel O., Bourouis I., Bougrine R., Housni B., El Ouafi N., Ismaili N. Acute myocarditis related to Covid-19 infection: 2 cases report. Annals of medicine and surgery (2012) . 2021;66 doi: 10.1016/j.amsu.2021.102431.102431 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bulbul R. F., Suwaidi J. A., Al-Hijji M., Tamimi H. A., Fawzi I. COVID-19 complicated by acute respiratory distress syndrome, myocarditis, and pulmonary embolism. A case report. The Journal of Critical Care Medicine . 2021;7(2):123–129. doi: 10.2478/jccm-2020-0041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gauchotte G., Venard V., Segondy M., et al. SARS-Cov-2 fulminant myocarditis: an autopsy and histopathological case study. International Journal of Legal Medicine . 2021;135(2):577–581. doi: 10.1007/s00414-020-02500-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gulersen M., Staszewski C., Grayver E., et al. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19)-Related multisystem inflammatory syndrome in a pregnant woman. Obstetrics and Gynecology . 2021;137(3):418–422. doi: 10.1097/aog.0000000000004256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Rasras H., Boudihi A., Hbali A., Ismaili N., Ouafi N. E. Multiple cardiovascular complications of COVID-19 infection in a young patient: a case report. Pan African Medical Journal . 2021;38:p. 192. doi: 10.11604/pamj.2021.38.192.27471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Purdy A., Ido F., Sterner S., Tesoriero E., Matthews T., Singh A. Myocarditis in COVID-19 presenting with cardiogenic shock: a case series. European Heart Journal- Case Reports . 2021;5(2) doi: 10.1093/ehjcr/ytab028.ytab028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sivalokanathan S., Foley M., Cole G., Youngstein T. Gastroenteritis and cardiogenic shock in a healthcare worker: a case report of COVID-19 myocarditis confirmed with serology. European Heart Journal-Case Reports . 2021;5(2) doi: 10.1093/ehjcr/ytab013.ytab013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ruiz J. G., Kandah F., Dhruva P., Ganji M., Goswami R. Case of coronavirus disease 2019 myocarditis managed with biventricular Impella support. Cureus . 2021;13(2) doi: 10.7759/cureus.13197.e13197 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Papageorgiou J. M., Almroth H., Tornudd M., van der Wal H., Varelogianni G., Lawesson S. S. Fulminant myocarditis in a COVID-19 positive patient treated with mechanical circulatory support- a case report. European Heart Journal-Case Reports . 2021;5(2) doi: 10.1093/ehjcr/ytaa523.ytaa523 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ciuca C., Fabi M., Di Luca D., et al. Myocarditis and coronary aneurysms in a child with acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2. European Society of Cardiology Heart Failure . 2021;8(1):761–765. doi: 10.1002/ehf2.13048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]