Abstract

Introduction

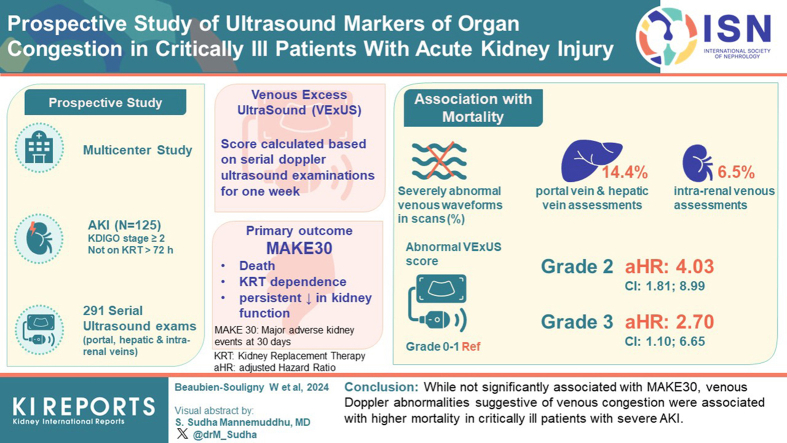

Organ congestion may be a mediator of adverse outcomes in critically ill patients with severe acute kidney injury (AKI). The presence of abnormal venous Doppler waveforms could identify patients with clinically significant organ congestion who may benefit from a decongestive strategy.

Methods

This prospective multicenter cohort study enrolled patients with severe AKI defined as Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes stage 2 or higher. Patients were not eligible if they received renal replacement therapy (RRT) for more than 72 hours at the time of screening. Participants underwent serial Doppler ultrasound examinations of the portal, hepatic and intrarenal veins during the week following enrolment. We calculated the venous excess ultrasound (VExUS) score based on these data. The primary outcome studied was major adverse kidney events at 30 days (MAKE30) defined as death, RRT dependence, or a persistent decrease in kidney function.

Results

A total of 125 patients were included for whom 291 ultrasound assessments were performed. Severely abnormal venous waveforms were documented in 14.4% of portal vein assessments, 6.5% of intrarenal venous assessments, and 14.4% of hepatic vein assessments. The individual ultrasound markers were not associated with MAKE30. The VExUS score (grade 0–1: reference; grade 2: adjusted hazard ratio [aHR]: 4.03, confidence interval [CI]: 1.81–8.99; grade 3: aHR: 2.70, CI: 1.10–6.65; P = 0.03), as well as severely abnormal portal, hepatic and intrarenal vein Doppler were each independently associated with mortality.

Conclusion

Although not significantly associated with MAKE30, venous Doppler abnormalities suggestive of venous congestion were associated with higher mortality in critically ill patients with severe AKI.

Keywords: acute kidney injury, cardiorenal, fluid balance, organ congestion, venous Doppler, VExUS

Graphical abstract

Organ congestion has been hypothesized to be a significant mediator of adverse outcomes in critical illness.1 Patients with severe AKI are at particular risk of fluid accumulation since their ability to excrete sodium and water is often compromised. In the setting of severe AKI, fluid accumulation documented through cumulative fluid balance estimation is associated with a higher risk of death.2, 3, 4 However, depending on the clinical circumstance, cumulative fluid balance following intensive care unit (ICU) admission may not be an accurate reflection of organ congestion. Preexisting fluid overload, due to heart failure or fluid resuscitation before ICU admission, or nonquantifiable fluid losses, such as acute hemorrhage or insensible losses, may distort the actual relationship between fluid balance and pathogenic congestion.5,6 To prevent or resolve organ edema, accurate clinical markers are needed to inform precise fluid management.

Ultrasound modalities available on point-of-care machines have been used to detect indirect markers of organ congestion.7 Venous pulse-wave Doppler ultrasound performed at multiple sites including the main portal vein, the hepatic veins, and interlobar veins of the kidney enable the detection of abnormal waveforms suggestive of decreased venous compliance.8 A grading system based on the combination of these markers has been termed the VExUS assessment.9 Significant congestion based of the VExUS grading system was able to predict the subsequent development of AKI after cardiac surgery with greater accuracy than central venous pressure measurements.9

In this study, we aimed to determine whether ultrasound markers of venous congestion are associated with adverse clinical events in critically ill patients with severe AKI. Secondarily, we aimed to describe the association between serial changes of these markers and adverse outcomes.

Methods

Study Design

This is a multicenter prospective cohort study conducted in 4 academic centers in Canada (St. Michael’s Hospital, Centre Hospitalier de l’Université de Montréal, Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre, University of Alberta Hospital), and one in Spain (Hospital General Universitari de Castelló from September 2018 to December 2021. All participants, or substitute decision-makers, provided informed written consent for participation. The study was approved by the ethics board of each participating institution (SMH:18-161 [2018-08-17], UoA:18-161 [2019-08-07], SHSC:373-2018 [2019-01-10], HGUC:ECHOAKI [2020-11-30], CHUM:19.176 [2019-09-16]). Procedures were followed in accordance with the ethical standards of the Tri-Council Policy Statement (TCPS 2) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975.We followed the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) guidelines.10 The study was registered at clinicaltrials.gov (NCT04095143).

Participants

Patients who were 18 years and older and admitted to the ICU were eligible if they developed severe AKI defined by the Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes AKI stage of either 2 or 3 which was defined as follows: (i) a ≥2-fold increase in serum creatinine, (ii) serum creatinine ≥354 μmol/l (≥4.0 mg/dl) with evidence of a minimum increase of 27 μmol/l (≥0.3 mg/dl), (iii) urine output <6.0 ml/kg over the preceding 12 hours, or (iv) initiation of RRT for AKI in the preceding 72 hours. Participants also had to have at least 1 creatinine value equal or superior to 100 μmol/l for females or 130 μmol/l for males. We excluded patients for whom there was a lack of commitment to provide RRT according to goals of care and those with preexisting severe chronic kidney disease defined as an estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) <20 ml/min per 1.73 m2.11

Ultrasound Assessment

Ultrasound assessments were performed on the day of enrolment (day 1), as well as at 72 hours and 7 days, provided the participants were still alive and admitted to the ICU. Ultrasound studies were performed at the bedside using an ultrasound machine with a phased array transducer and/or a convex array transducer by investigators trained in critical care ultrasound (WBS, LG, BB, and VL) as previously reported12 and detailed in the Supplementary Material.

Based on previous data, a portal Doppler waveform exhibiting a pulsatility fraction (PF) ≥50%,12,13 a hepatic vein waveform with a retrograde systolic component (S/D ratio ≤0),9 and a pattern of intrarenal venous flow in which prolonged interruption with signal only present in diastole were each considered severely abnormal.14 The VExUS grade was determined in participants who had at least 2 of the sites successfully assessed based on the previously published classification9 as presented in Supplementary Figure S1. Basic evaluation of left ventricular and right ventricular function was also performed as described in the Supplementary Material.

Reproducibility

Three experienced operators were asked to interpret sets of 25 images of portal, hepatic, and renal Doppler chosen at random among the ultrasound images collected during the study. Operators reviewed all images and graded them independently. Interobserver agreement was reported as the percentage of agreement and using Fleiss’ Kappa statistic15 for 3 category classification (normal/mildly abnormal/severely abnormal). A supplementary analysis was done according to a binary classification (normal/mildly abnormal vs. severely abnormal).

Data Collection

Baseline characteristics of participants, including demographic information, medical history, current episode of care, and severity of illness were collected including the use of vasopressors, inotropes, and RRT at enrolment. Baseline eGFR was derived from the Chronic Kidney Disease – Epidemiology Collaboration equation.11 Clinical information was collected at the time of ultrasound assessments, and these included hemodynamic parameters, use of mechanical ventilation, and Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA score).16

Follow-up information collected included ICU cumulative fluid balance from admission to 7 days after enrolment, number of days in the ICU and in the hospital, number of days on vasopressor support and mechanical ventilation, mortality, receipt of RRT at 30 and 90 days, as well as creatinine values at 30 and 90 days (± 7 days), if available.

Clinical Outcomes

The primary outcome was a MAKE30.17,18 This composite outcome comprised death, RRT dependence, or sustained loss of kidney function (new onset of eGFR <60 ml/min per 1.73 m2 or, if preexisting eGFR <60 ml/min per 1.73 m2, a ≥25% decline in eGFR). To estimate kidney function at 30 days, we used the nearest creatinine value ± 7 days. We also assessed 90-day vital status and RRT dependence from available medical records or by contacting participants by phone.

Prespecified secondary outcomes included the individual components of MAKE30, ICU-free days through day 30, ventilator-free days through day 30, vasopressor-free days through day 30, and eGFR at 90 days calculated with the Chronic Kidney Disease – Epidemiology Collaboration equation11 using a serum creatinine from a sample drawn as close as possible to day 90. A ventilator-free or vasopressor-free day required receipt of mechanical ventilation or vasopressors (norepinephrine, epinephrine, vasopressin, and phenylephrine) for less than 2 hours per 24 hour period, respectively. Participants who were alive and free of RRT at 90 days but who did not have a serum creatinine value available (within 30 days of the 90-day follow-up date) were excluded from the analysis regarding eGFR at 90 days but were included in the analysis regarding MAKE30 using their last available serum creatinine prior to Day 30.

Statistical Analysis

For the primary analysis, the association between the first recorded VExUS score and MAKE30 was assessed using univariable and multivariable logistic regression. We adjusted for an array of a priori selected variables, including biological sex, diabetes, coronary disease, chronic kidney disease, receipt of RRT, vasopressors, mechanical ventilation, and vasoactive medications.

Time-dependent Cox regression analysis was performed to study the association between mortality and venous Doppler markers. In this analysis, the result of the venous Doppler marker of interest was updated after each subsequent assessment during the first 7 days after enrolment. Adjustment was performed using the same covariates. Survival during the initial 30 days according to initial VExUS score was also depicted using Kaplan-Meier survival curves.

For RRT dependence and worsening of kidney function at 30 days, a multinomial logistic regression was used to account for the competing risk of mortality. Results are expressed as odd ratios (ORs) with 95% CIs. As a sensitivity analysis, all analyses were also performed using the last recorded result for each ultrasound marker as the exposure variable. We also performed an additional multivariable analysis using SOFA score as the sole adjustment variable. No imputation was performed for missing values except for SOFA score in the sensitivity analysis for which the median value was imputed for missing values in components of the score which ranged from 4.0% to 8.0%. We used a last-value carried forward strategy for the purpose of the time-dependent Cox models to account for missing ultrasound assessments after ICU discharge. Details of the sample size estimation and simple comparisons are presented in the Supplementary Material. All analyses were performed using SPSS version 26 (IBM, Armonk, NY).

Results

Participant Characteristics and Outcomes

During the study period, 130 patients were enrolled, and 125 patients were included in the analyses (Supplementary Figure S2). Baseline characteristics of participants are presented in Table 1 and Supplementary Table S1. The median age was 67 (interquartile range [IQR]: 56–73) years. The primary reasons for ICU admission were cardiovascular (36.8%) or infectious (23.2%). At the time of enrolment, 29.6% were receiving RRT. The median time from ICU admission to enrolment was 3 days (IQR: 2–5). At enrolment, most participants were on vasopressor support (54.8%) and mechanical ventilation (68.0%) with a median SOFA score of 10 (IQR: 7–13). The median cumulative ICU fluid balance at enrolment was 5.1 L (IQR: 1.8–8.7) which represented a median fluid accumulation of 6.5% (IQR: 2.5–10.1) above admission body weight.

Table 1.

Patients characteristics in relationship with Venous Excess Ultrasound grading at enrolment

| Characteristics | All patients n (%) (N = 125) |

Normal venous Doppler (VExUS grade 0 or1) (N = 83) |

Abnormal venous Doppler (VExUS grade 2 or 3) (N = 30) |

P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline characteristics | ||||

| Age (years) | 67 (56–73) | 66 (56–73) | 69 (58–74) | 0.05 |

| Weight (kg) | 82 (69–96) | 83 (69–98) | 82 (71–94) | 0.81 |

| Female - Male sex | 35 - 90 (27%–72%) | 26 – 57 (31.3%–68.7%) | 5 – 25 (16.7%–83.3%) | 0.12 |

| Medical history | ||||

|

73 (58.4%) | 44 (53.0%) | 22 (73.3%) | 0.053 |

|

41 (32.8%) | 26 (31.3%) | 9 (30.0%) | 1.00 |

|

12 (9.6%) | 7 (8.4%) | 3 (10.0%) | 0.80 |

|

22 (17.6%) | 16 (19.3%) | 6 (20.0%) | 1.00 |

|

17 (13.6%) | 14 (16.9%) | 1 (3.3%) | 0.06 |

|

9 (7.2%) | 5 (6.0%) | 3 (10.0%) | 0.47 |

|

17 (13.6%) | 14 (16.9%) | 2 (6.7%) | 0.23 |

|

26 (20.8%) | 13 (15.7%) | 10 (33.3%) | 0.04 |

|

21 (16.8%) | 7 (8.4%) | 8 (26.7%) | 0.01 |

|

9 (7.2%) | 5 (6.0%) | 4 (13.3%) | 0.20 |

| Admission diagnostic category | ||||

| Cardiovasculara | 46 (36.8%) | 18 (21.7%) | 24 (80.0%) | <0.001 |

| Sepsis | 29 (23.2%) | 22 (26.5%) | 2 (6.7%) | |

| Gastrointestinal/hepatic | 17 (13.6%) | 16 (19.3%) | 1 (3.3%) | |

| Respiratory | 12 (9.6%) | 9 (10.8%) | 2 (6.7%) | |

| Neurologic | 4 (3.2%) | 3 (3.6%) | 1 (3.3%) | |

| Trauma | 3 (2.4%) | 2 (2.4%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Other | 14 (11.2%) | 13 (15.7%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Cardiothoracic surgery with cardiopulmonary bypass in prior 7 days | 34 (27.2%) | 12 (14.5%) | 20 (66.7%) | <0.001 |

| Time from ICU admission to enrolment (Days) | 3 (2–5) | 2 (1–5) | 3 (2–6) | 0.09 |

| Mechanical ventilation at enrolment | 85 (68.0%) | 55 (68.8%) | 23 (76.7%) | 0.49 |

| Vasopressor support at enrolment | 81 (64.8%) | 50 (61.7%) | 22 (73.3%) | 0.28 |

| Inotropic support at enrolment | 16 (12.8%) | 4 (4.8%) | 11 (36.7%) | <0.001 |

| SOFA score | 10 (7–13) | 9 (6–12) | 10 (7–15) | 0.59 |

| RRT at enrollment | 37 (29.6%) | 22 (26.5%) | 11 (36.7%) | 0.29 |

| Cumulative fluid balance at enrolment (l) | 5.1 (1.8–8.7) | 5.0 (1.7–8.7) | 6.0 (3.2–10.1) | 0.29 |

| Outcomes | ||||

| Receipt of any RRT during hospitalization (including at enrolment) | 72 (57.6%) | 42 (50.6%) | 16 (53.3%) | 0.80 |

| Death at 30 days | 40 (32.0%) | 22 (26.5%) | 13 (43.3%) | 0.09 |

| Death at 90 days | 45 (38.5%) | 27 (32.5%) | 13 (43.3%) | 0.29 |

| Receipt of RRT at 30 days | 9 (7.2%) | 8 (9.6%) | 1 (3.3%) | 0.44 |

| Receipt of RRT at 90 days | 3 (2.6%) | 3 (3.6%) | 0 (0%) | 0.5 |

| Sustained loss of kidney function b at 30 days | 15 (12.0%) | 10 (12.0%) | 5 (16.1% | 1.00 |

| Sustained loss of kidney function b at 90 days | 9 (7.7%) | 7 (8.4%) | 2 (6.7%) | 1.00 |

| Major adverse kidney eventsc at 30 days | 64 (51.2%) | 40 (48.2%) | 18 (60.0%) | 0.27 |

| Major adverse kidney eventsc at 90 days | 57 (48.7%) | 36 (46.8%) | 15 (51.7%) | 0.65 |

eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; ICU, intensive care unit, RRT, Renal replacement therapy; VExUS, venous excess ultrasound.

VExUS grading could not be completed in 12 (9.6%) of patients. Continuous variables expressed as median (interquartile range); categorical variables expressed as number (%).

Details of cardiovascular admissions are presented in Supplementary Table S1.

In patients not receiving RRT, sustained loss of kidney function was defined as a sustained loss of kidney function (new onset of eGFR) <60 ml/min per 1.73 m2 or, if preexisting eGFR <60 ml/min per 1.73 m2, a 25% or greater decline in eGFR.

Major adverse kidney event were defined as death, RRT dependence, or sustained loss of kidney function.

MAKE30 occurred in 51.2% participants (32.0% death, 7.2% RRT dependence, and 12.0% worsening of kidney function). At 90-day follow-up, 48.7% attained MAKE90 criteria (38.5% death, 2.6% RRT dependence, and 7.7% worsening of kidney function).

Ultrasound Assessments

Interrater agreement was excellent for portal vein Doppler (Kappa = 0.92, P < 0.001) and moderate for hepatic (Kappa = 0.76, P < 0.001) and renal (Kappa = 0.79, P < 0.001) Doppler assessments. The agreement improved for hepatic and renal Doppler when considering a binary (normal/mildly abnormal vs. severely abnormal) classification (Kappa = 0.88, P < 0.001 and Kappa = 0.92, P < 0.001, respectively).

A total of 291 ultrasound assessments were performed, including 125 at enrolment, 99 at 72 hours and 67 at 7 days. Image acquisition success rate for portal vein Doppler was excellent (93.8%), whereas it was good for hepatic vein Doppler (83.2%) and moderate for intrarenal venous Doppler (70.1%) (Supplementary Table S2). At least 2 sites were available for computation of the VExUS grade in 89.3% of exams.

Results from the ultrasound assessment are presented in Table 2. Severely abnormal signals were documented in 14.4% of portal vein assessments, 6.5% of intrarenal vein assessments, and 14.4% of hepatic vein assessments. VExUS grade 2 and grade 3 were present in 10.7% and 9.6% of all assessments, respectively. The prevalence of portal Doppler PF as well as the proportion of participants with a PF ≥50% significantly decreased during the first 72 hours after enrolment (PF: 27% [14; 40] to 23% [15; 35] P = 0.04; and PF ≥50%: 19.2% to 9.1%, P = 0.008). The prevalence of other venous Doppler markers and VExUS grade did not significantly change over time. Change in VExUS grading over time in participants is illustrated in Supplementary Figure S3.

Table 2.

Results of the ultrasound assessments

| First assessment (Enrolment) (N = 125) |

Second assessment (72 hours) (N = 99) |

Third Assessment (7 days) (N = 67) |

All assessments (N = 291) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Portal vein Doppler | ||||

| Median PF (IQR) | 27 (14–40)a | 23 (15–35)a | 21 (11–33) | 25 (14–36) |

| Severely abnormal | 24 (19.2%)a | 9 (9.1%)a | 9 (13.4%) | 42 (14.4%) |

| Hepatic vein Doppler | ||||

| Median S/D ratio (IQR) | 1.04 (0.31–1.39) | 1.07 (0.41–1.29) | 1.09 (0.86–1.40) | 1.05 (0.62–1.39) |

| Severely abnormal | 22 (17.6%) | 15 (15.2%) | 5 (7.5%) | 42 (14.4%) |

| Renal venous Doppler | ||||

| Severely abnormal | 10 (8.0%) | 7 (7.1%) | 2 (3.0%) | 19 (6.5%) |

| VExUS grading | ||||

| Grade 0–1 | 83 (66.4%) | 69 (69.7%) | 49 (73.1%) | 200 (68.7%) |

| Grade 2 | 14 (11.2%) | 10 (10.1%) | 7 (10.4%) | 31 (10.7%) |

| Grade 3 | 16 (12.8%) | 9 (9.1%) | 3 (4.5%) | 28 (9.6%) |

D, diastolic; IQR, interquartile range; PF, pulsatility fraction; S, systolic; VExUS, venous excess ultrasound.

Median portal pulsatility fraction (PF) significantly decreased from the first to the second assessment (P = 0.04) as did the proportion of participants with a severely abnormal portal vein waveform (P = 0.008). There were no significant changes over time for other markers and timepoints.

As shown in Table 1, patients with at least 1 abnormal Doppler marker on the first assessment (VExUS grade 2 or 3) were more likely to have been admitted to the ICU for a cardiovascular cause (80.0% vs. 21.7% among those with VExUS grade 1, P < 0.001), more likely to have had surgery with cardiovascular bypass in the previous 7 days (66.7% vs. 14.5% among those with VExUS grade 1, P < 0.001), and more likely to be receiving vasoactive support at the time of enrolment (36.7% vs. 4.8% among those with VExUS grade 1, P < 0.001).

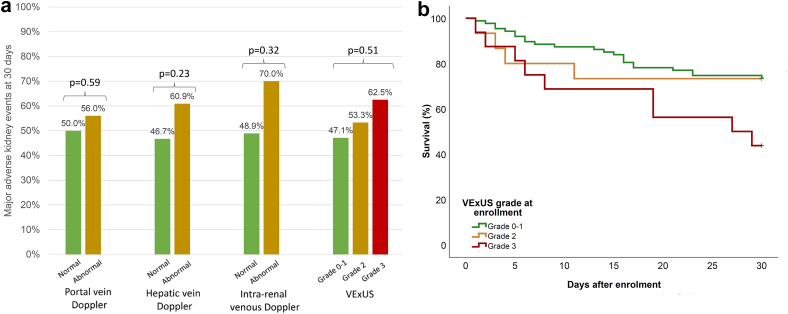

Association Between Ultrasound Markers at Baseline and Outcomes

VExUS grade and organ-specific markers of congestion measured at enrolment were not associated with MAKE30 (Table 3 and Figure 1a). When evaluated as a time-dependent exposure, abnormal portal Doppler (HR: 2.36, [95% CI: 1.18–4.72], P = 0.02), severely abnormal intrarenal Doppler (HR: 2.58, [95% CI: 1.07–6.23], P = 0.04) as well as VExUS grade 2 (HR: 3.12 [95% CI: 1.49–6.53], P = 0.003) and 3 (HR: 2.81, [95% CI: 1.20–6.56], P = 0.02) were associated with 90-day mortality. After adjustment for baseline characteristics and receipt of organ support, all remained independently associated with mortality (Table 4). Survival according to the VExUS grade on the first assessment is illustrated in Figure 1b.

Table 3.

Association between ultrasound markers at enrolment and major adverse kidney event at day 30 (MAKE30)

| Incidence of MAKE30 | Univariable OR (CI) P-value | Multivariable ORa (CI) P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Portal vein Doppler (N = 118) | |||

| Normal or mildly abnormal | 48 (51.1%) | Ref | Ref |

| Severely abnormal | 13 (54.2%) | 1.13 (0.46–2.78) P = 0.79 | 1.25 (0.45–3.46) P = 0.67 |

| Hepatic vein Doppler (N = 104) | |||

| Normal or mildly abnormal | 43 (46.7%) | Ref | Ref |

| Severely abnormal | 14 (60.9%) | 1.77 (0.70–4.50) 0.23 | 1.53 (0.52–4.50) 0.44 |

| Intrarenal vein Doppler (N = 88) | |||

| Normal or mildly abnormal | 39 (49.4%) | Ref | Ref |

| Severely abnormal | 6 (66.7%) | 2.05 (0.48–8.78) P = 0.33 | 2.75 (0.52–14.47) P = 0.23 |

| VExUS grading (N = 113) | |||

| Grade 0–1 | 40 (48.2%) | Ref | Ref |

| Grade 2 | 8 (57.1%) | 1.43 (0.46–4.49) P = 0.54 | 1.09 (0.28–4.28) P = 0.90 |

| Grade 3 | 10 (62.5%) | 1.79 (0.60–5.38) P = 0.30 | 2.12 (0.60–7.47) 0.24 |

CI, confidence interval; MAKE30, major adverse kidney events at 30 days; VExUS: Venous Excess UltraSound grading system.

Logistic regression model with ultrasound markers at the first assessment as the exposure variable.

Adjusted for sex, diabetes, coronary disease, chronic kidney disease, receipt of renal replacement therapy at enrolment, receipt of vasopressors at enrolment, receipt of mechanical ventilation at enrolment and receipt of inotropic medication at enrolment.

Figure 1.

Participant outcomes in the first 30 days after enrolment. (a) Major adverse kidney events according to ultrasound markers at enrolment. (b) Kaplan-Meier curves illustrating survival according to Venous Excess UltraSound (VExUS) grading at enrolment in the first 30 days after enrolment (Log-rank P = 0.049).

Table 4.

Association between ultrasound markers as time-dependent variables and mortality through 90 days

| Univariable HR (CI) P-value | Multivariablea Adjusted HR (CI) P-value |

|

|---|---|---|

| Normal or mildly abnormal | Ref | Ref |

| Severely abnormal | 2.36 (1.18–4.72) 0.02 | 2.43 (1.19–4.98) 0.02 |

| Per 10% increase in pulsatility fraction | 1.09 (1.01–1.18) 0.03 | 1.12 (1.02–1.23) 0.01 |

| Normal or mildly abnormal | Ref | Ref |

| Severely abnormal | 2.38 (0.15–4.91) 0.02 | 2.51 (1.15–5.46) 0.02 |

| Per 0.1 decrease in the S/D velocity ratio | 1.02 (099–1.06) 0.19 | 1.03 (0.99–1.07) 0.17 |

| Normal or mildly abnormal | Ref | Ref |

| Severely abnormal | 2.58 (1.07–6.23) 0.04 | 2.89 (1.11–7.55) 0.03 |

| Grade 0-1 | Ref | Ref |

| Grade 2 | 3.12 (1.49–6.53) 0.003 | 4.03 (1.81–8.99) <0.001 |

| Grade 3 | 2.81 (1.20–6.56) 0.02 | 2.70 (1.10–6.65) 0.03 |

CI, confidence interval; D, diastolic; S, systolic; HR, hazard ratio; VExUS, venous excess ultrasound assessment.

Cox regression model with ultrasound markers as time-dependent variable updated at each ultrasound examination.

Adjusted for sex, diabetes, coronary disease, chronic kidney disease, receipt of renal replacement therapy at enrolment, receipt of vasopressors at enrolment, receipt of mechanical ventilation at enrolment, and receipt of inotropic medication at enrolment.

As a sensitivity analysis, we performed the analysis using portal PF as a continuous variable, which showed a significant association with mortality (HR: 1.09, [95% CI: 1.01–1.18], P = 0.03; aHR: 1.12 [95% CI: 1.02–1.23], P = 0.01 per 10% increase in PF). We also created an alternative multivariable model with SOFA score at enrolment as an adjustment variable which produced similar results (Supplementary Table S3). Inferior vena cava dimensions were not associated with MAKE30 or mortality (Supplementary Tables S4 and S5). Finally, an association was found between VExUS grade 3 and mortality when considering only the first assessment after enrolment (non-time varying) (Supplementary Table S6).

VExUS grading at first assessment was not associated with kidney-specific outcomes or therapy-free days (Supplementary Table S7). Severely abnormal intrarenal vein Doppler at initial assessment was associated with fewer vasopressor-free days (3 [IQR: 0–19] days vs. 26 [IQR: 11–29] days, P = 0.02). For participants not on RRT at enrolment, VExUS grading was not predictive of RRT initiation during hospitalization (VExUS grade 2 OR: 4.22 [95% CI: 0.45–37.14], P = 0.20; VExUS grade 3: OR: 0.82 [95% CI: 0.25–2.72], P = 0.75).

Association Between Last Available Ultrasound Markers and Outcomes

Associations between the last available results for ultrasound assessment as the exposure variable and studied outcomes are presented in Supplementary Table S8. VExUS grading and individual ultrasound assessments were not associated with MAKE30 but were associated with a higher risk of 30-day and 90-day mortality (VExUS grade 2: OR: 4.65, [95% CI: 1.53–14.18], P = 0.007; VExUS grade 3: OR: 4.89 [95% CI: 1.31–18.18], P = 0.02). Severely abnormal portal vein Doppler and hepatic vein Doppler were also associated with increased risk of mortality. Furthermore, a higher VExUS grade and severely abnormal hepatic vein Doppler were associated with fewer vasopressor-free days.

Association Between Ultrasound Markers and Other Clinical Characteristics

During the study period, portal Doppler PF was associated with cumulative ICU fluid balance (β: 0.50 [95% CI: 0.52–0.95], P = 0.03), whereas the other markers were not (Supplementary Table S9). All venous Doppler markers were associated with right ventricular dysfunction and were negatively associated with tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion, a marker of right ventricular systolic function, as well as with the maximal diameter of the inferior vena cava. No patients exhibiting an inferior vena cava with important respiratory variations (>50%) had severely abnormal venous Doppler markers.

Discussion

In critically ill patients with severe AKI, we found that abnormal Doppler patterns in the portal and hepatic veins, as well as VExUS grades of ≥2 were associated with mortality but not with MAKE. Only portal vein pulsatility was associated with cumulative fluid balance, but all markers were strongly associated with right ventricular function and were more commonly found in patients admitted for a cardiovascular diagnosis.

Venous Doppler assessment has been proposed as a method to identify settings where venous hypertension is severe enough to lead to organ dysfunction. Abnormal waveforms in the hepatic, portal, and interlobar veins of the kidney are correlated with various markers reflective of venous congestion, including elevated right ventricular end-diastolic ventricular pressure,13 high cumulative fluid balance,12 and increased concentrations of natriuretic peptides.12 Furthermore, these markers have been associated with adverse outcomes in patients with congestive heart failure,14,19 pulmonary hypertension,20 and cardiac surgery.12,13 In a cohort of 114 critically ill patients, portal vein Doppler PF was associated with MAKE30, whereas intrarenal and hepatic vein Doppler alterations were not.21 We deliberately selected patients with severe AKI where fluid accumulation is nearly ubiquitous. This is also a subset of the ICU population with a greater severity of illness compared to the sample studied by Spiegel et al.21 as reflected by a higher 30-day mortality rate (32.0% vs. 17.5%), and consequently a higher rate of MAKE30 (51.2% vs. 37.4%). The components that comprise MAKE, specifically progression to chronic kidney disease and RRT dependence, were not associated with VExUS grade although the competing risk of death may have overshadowed the associations with kidney-specific end points.

Cardiac dysfunction appears to be a primary factor associated with the occurrence of venous Doppler abnormalities with strong associations observed with right ventricular dysfunction and tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion, respectively. Moreover, venous Doppler markers were strikingly more frequent in patients admitted for a cardiovascular diagnosis or in the context of recent surgery with cardiopulmonary bypass. Similarly, a low prevalence of severe venous Doppler markers was reported in other cohorts with a predominance of medical admissions and sepsis22,23 compared to previous studies performed in cardiac surgery and acute decompensated heart failure. Conversely, there was no significant differences in cumulative fluid balance at enrolment in patients with abnormal venous Doppler. Previous experiments showed that fluid expansion can worsen intrarenal venous Doppler patterns in patients with congestive heart failure,24 whereas improvements are observed during decongestive treatment.25,26 We hypothesize that hemodynamic alterations due to high venous pressure, which in turn contribute to the appearance of these venous Doppler alterations, could mediate the association between fluid accumulation and adverse outcomes predominantly in specific clinical contexts, such as cardiac surgery or cardiogenic shock, in which rapid lowering of central venous pressure may be important for hemodynamic improvement.

Our study has several strengths. First, its prospective design avoided bias related to the indication of performing a venous Doppler ultrasound. Participants were enrolled in multiple centers providing access to a diverse population. Second, this is one of the first studies in which the VExUS grading system was applied to a cohort of general ICU patients. We included only patients with severe AKI, a subpopulation of critically ill patients at high risk of adverse outcomes who are particularly affected by fluid accumulation but with variable cardiac impairment. Third, we performed serial ultrasound assessments during the first week after enrolment to more precisely establish the relationship between ultrasound markers of interest and mortality.

Our study has some limitations. Considering the trends observed, which were consistent across all studied venous Doppler markers, it is possible that an association with the primary outcome of MAKE30 was present but went undetected due to a lack of statistical power. This limitation applies in particular to the kidney-specific components for which the event rate was low. The absence of association with kidney-specific end point may also be related to the inclusion of patients late in the course of AKI, when RRT was already initiated, although the median duration from ICU admission to enrolment was relatively short (3 days). In addition, the prevalence of the studied ultrasound markers was lower than expected, which further compromised statistical power to detect clinically meaningful differences in outcomes. Although this finding is important to report, because it indicates that venous congestion may only affect a subgroup of patients with severe AKI, additional enrichment of the sample with participants with documented cardiac dysfunction may have yielded different results. The limited sample size may have also limited our ability to compare subgroups of patients and their evolving venous congestion markers over time. Furthermore, the success rate of kidney Doppler assessments was suboptimal as previously reported in other studies involving critically ill patients,21,27 which emphasizes the importance of performing the assessment at multiple anatomical sites and potentially investigating alternate sites such as the femoral vein.28

Conclusions

In patients with severe AKI, readily-measured ultrasonographic markers of congestion are associated with higher mortality although an adverse impact on kidney recovery was not observed. Further study is needed to determine whether fluid management strategies guided by point-of-care ultrasound impact on clinical outcomes.

Disclosure

WB-S has received speaker fees from Baxter in 2023. AD is a speaker and consultant for CAE Healthcare, a speaker for Edwards and Masimo, and received a research grant from Edwards (2019). All the other authors declared no competing interests.

Acknowledgments

WB-S’s work is supported by the KRESCENT program (Kidney Foundation of Canada) and is the recipient of a research career award from the Fonds de recherche du Québec en Santé (Clinical Research Scholar Junior 1). This work was supported by the Fondation du CHUM (Ly family donation for dialysis research).

Footnotes

Supplementary Methods.

Figure S1. Venous Excess Ultrasound grading.

Figure S2. Inclusion flowchart.

Figure S3. Sankey diagram illustrating change in VExUS grading.

Table S1. Admission diagnostic for participants in the cardiovascular category.

Table S2. The success rate of ultrasound assessment.

Table S3. Sensitivity analysis: alternative model adjusted for severity of illness (SOFA) to assess the association between ultrasound markers as time-dependent variables and mortality through 90 days.

Table S4. Association between inferior vena cava parameters as time-dependent variables and mortality through 90 days.

Table S5. Association between inferior vena cava parameters at the first available assessment and major adverse kidney event at day 30.

Table S6. Sensitivity analysis: Association between ultrasound markers at the first assessment and 90-day mortality.

Table S7. Association between individual ultrasound markers at the first assessment and studied outcomes.

Table S8. Clinical outcomes in relationship with last recorded values of the studied ultrasound markers.

Table S9. Association between venous Doppler parameters and other clinical characteristics.

Supplemental References

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Methods

Figure S1. Venous Excess Ultrasound grading.

Figure S2. Inclusion flowchart.

Figure S3. Sankey diagram illustrating change in VExUS grading.

Table S1. Admission diagnostic for participants in the cardiovascular category.

Table S2. The success rate of ultrasound assessment.

Table S3. Sensitivity analysis: alternative model adjusted for severity of illness (SOFA) to assess the association between ultrasound markers as time-dependent variables and mortality through 90 days.

Table S4. Association between inferior vena cava parameters as time-dependent variables and mortality through 90 days.

Table S5. Association between inferior vena cava parameters at the first available assessment and major adverse kidney event at day 30.

Table S6. Sensitivity analysis: Association between ultrasound markers at the first assessment and 90-day mortality.

Table S7. Association between individual ultrasound markers at the first assessment and studied outcomes.

Table S8. Clinical outcomes in relationship with last recorded values of the studied ultrasound markers.

Table S9. Association between venous Doppler parameters and other clinical characteristics.

Supplemental References

References

- 1.Prowle J.R., Kirwan C.J., Bellomo R. Fluid management for the prevention and attenuation of acute kidney injury. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2014;10:37–47. doi: 10.1038/nrneph.2013.232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bouchard J., Soroko S.B., Chertow G.M., et al. Fluid accumulation, survival and recovery of kidney function in critically ill patients with acute kidney injury. Kidney Int. 2009;76:422–427. doi: 10.1038/ki.2009.159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Heung M., Wolfgram D.F., Kommareddi M., Hu Y., Song P.X., Ojo A.O. Fluid overload at initiation of renal replacement therapy is associated with lack of renal recovery in patients with acute kidney injury. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2012;27:956–961. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfr470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bellomo R., Cass A., Cole L., et al. An observational study fluid balance and patient outcomes in the Randomized Evaluation of Normal vs. augmented Level of Replacement Therapy trial. Crit Care Med. 2012;40:1753–1760. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e318246b9c6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Perren A., Markmann M., Merlani G., Marone C., Merlani P. Fluid balance in critically ill patients. Should we really rely on it? Minerva Anestesiol. 2011;77:802–811. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Davies H., Leslie G., Jacob E., Morgan D. Estimation of body fluid status by fluid balance and body weight in critically ill adult patients: a systematic review. Worldviews Evid-Based Nurs. 2019;16:470–477. doi: 10.1111/wvn.12394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Beaubien-Souligny W., Bouchard J., Desjardins G., et al. Extracardiac signs of fluid overload in the critically ill cardiac patient: a focused evaluation using bedside ultrasound. Can J Cardiol. 2017;33:88–100. doi: 10.1016/j.cjca.2016.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Deschamps J., Denault A., Galarza L., et al. Venous Doppler to assess congestion: a comprehensive review of current evidence and nomenclature. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2023;49:3–17. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2022.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Beaubien-Souligny W., Rola P., Haycock K., et al. Quantifying systemic congestion with Point-Of-Care ultrasound: development of the venous excess ultrasound grading system. Ultrasound J. 2020;12:16. doi: 10.1186/s13089-020-00163-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Von Elm E., Altman D.G., Egger M., et al. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147:573–577. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-147-8-200710160-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Levey A.S., Stevens L.A., Schmid C.H., et al. A new equation to estimate glomerular filtration rate. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150:604–612. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-150-9-200905050-00006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Beaubien-Souligny W., Benkreira A., Robillard P., et al. Alterations in portal vein flow and intrarenal venous flow are associated with acute kidney injury after cardiac surgery: a prospective observational cohort study. J Am Heart Assoc. 2018;7 doi: 10.1161/JAHA.118.009961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Eljaiek R., Cavayas Y.A., Rodrigue E., et al. High postoperative portal venous flow pulsatility indicates right ventricular dysfunction and predicts complications in cardiac surgery patients. Br J Anaesth. 2019;122:206–214. doi: 10.1016/j.bja.2018.09.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Iida N., Seo Y., Sai S., et al. Clinical implications of intrarenal hemodynamic evaluation by Doppler ultrasonography in heart failure. JACC Heart Fail. 2016;4:674–682. doi: 10.1016/j.jchf.2016.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Falotico R., Quatto P. Fleiss’ kappa statistic without paradoxes. Qual Quant. 2015;49:463–470. doi: 10.1007/s11135-014-0003-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vincent J.-L., De Mendonça A., Cantraine F., et al. Use of the SOFA score to assess the incidence of organ dysfunction/failure in intensive care units: results of a multicenter, prospective study. Working group on “sepsis-related problems” of the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine. Crit Care Med. 1998;26:1793–1800. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199811000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Palevsky P.M., Molitoris B.A., Okusa M.D., et al. Design of clinical trials in acute kidney injury: report from an NIDDK workshop on trial methodology. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2012;7:844–850. doi: 10.2215/CJN.12791211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Semler M.W., Rice T.W., Shaw A.D., et al. Identification of major adverse kidney events within the electronic health record. J Med Syst. 2016;40:167. doi: 10.1007/s10916-016-0528-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yamamoto M., Seo Y., Iida N., et al. Prognostic impact of changes in intrarenal venous flow pattern in patients with heart failure. J Card Fail. 2021;27:20–28. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2020.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Husain-Syed F., Birk H.W., Ronco C., et al. Doppler-derived renal venous stasis index in the prognosis of right heart failure. J Am Heart Assoc. 2019;8 doi: 10.1161/JAHA.119.013584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Spiegel R., Teeter W., Sullivan S., et al. The use of venous Doppler to predict adverse kidney events in a general ICU cohort. Crit Care. 2020;24:615. doi: 10.1186/s13054-020-03330-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fujii K., Nakayama I., Izawa J., et al. Association between intrarenal venous flow from Doppler ultrasonography and acute kidney injury in patients with sepsis in critical care: a prospective, exploratory observational study. Crit Care. 2023;27:278. doi: 10.1186/s13054-023-04557-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Andrei S., Bahr P.A., Nguyen M., Bouhemad B., Guinot P.G. Prevalence of systemic venous congestion assessed by venous Excess ultrasound Grading System (VExUS) and association with acute kidney injury in a general ICU cohort: a prospective multicentric study. Crit Care. 2023;27:224. doi: 10.1186/s13054-023-04524-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nijst P., Martens P., Dupont M., Tang W.H.W., Mullens W. Intrarenal flow alterations during transition from euvolemia to intravascular volume expansion in heart failure patients. JACC Heart Fail. 2017;5:672–681. doi: 10.1016/j.jchf.2017.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ter Maaten J.M., Dauw J., Martens P., et al. The effect of decongestion on intrarenal venous flow patterns in patients with acute heart failure. J Card Fail. 2021;27:29–34. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2020.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bouabdallaoui N., Beaubien-Souligny W., Denault A.Y., Rouleau J.L. Impacts of right ventricular function and venous congestion on renal response during depletion in acute heart failure. ESC Heart Fail. 2020;7:1723–1734. doi: 10.1002/ehf2.12732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wiersema R., Kaufmann T., van der Veen H.N., et al. Diagnostic accuracy of arterial and venous renal Doppler assessment for acute kidney injury in critically ill patients: a prospective study. J Crit Care. 2020;59:57–62. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2020.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bhardwaj V., Rola P., Denault A., Vikneswaran G., Spiegel R. Femoral vein pulsatility: a simple tool for venous congestion assessment. Ultrasound J. 2023;15:24. doi: 10.1186/s13089-023-00321-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.