Significance

Music is powerful in expressing and experiencing emotions, and affective neuroscience research used music to investigate brain mechanisms for processing auditory emotions. Previous research used recorded music to define a neural model for musical emotion processing, but the use of recorded music has limitations. Unlike recorded music, intense musical emotions are most often expressed in live musical performances and are experienced when listening to live music in concerts, given the dynamic relationship between performing artists and the audience. Here, we show that live music can stimulate the affective brain of listeners more strongly and consistently than recorded music. Live music also leads to dynamic music-brain couplings, including brain responses that are partly contrary to established neural models on musical emotions.

Keywords: music, emotion, amygdala, limbic, neurofeedback

Abstract

Music is powerful in conveying emotions and triggering affective brain mechanisms. Affective brain responses in previous studies were however rather inconsistent, potentially because of the non-adaptive nature of recorded music used so far. Live music instead can be dynamic and adaptive and is often modulated in response to audience feedback to maximize emotional responses in listeners. Here, we introduce a setup for studying emotional responses to live music in a closed-loop neurofeedback setup. This setup linked live performances by musicians to neural processing in listeners, with listeners’ amygdala activity was displayed to musicians in real time. Brain activity was measured using functional MRI, and especially amygdala activity was quantified in real time for the neurofeedback signal. Live pleasant and unpleasant piano music performed in response to amygdala neurofeedback from listeners was acoustically very different from comparable recorded music and elicited significantly higher and more consistent amygdala activity. Higher activity was also found in a broader neural network for emotion processing during live compared to recorded music. This finding included observations of the predominance for aversive coding in the ventral striatum while listening to unpleasant music, and involvement of the thalamic pulvinar nucleus, presumably for regulating attentional and cortical flow mechanisms. Live music also stimulated a dense functional neural network with the amygdala as a central node influencing other brain systems. Finally, only live music showed a strong and positive coupling between features of the musical performance and brain activity in listeners pointing to real-time and dynamic entrainment processes.

Music listening is a universally beloved and popular activity, often because music is successful at portraying emotions in musical performances and eliciting various emotions in listeners (1, 2). Such emotions can range from pleasant to unpleasant at the most basic level (3, 4), but music can also evoke more specific negative and positive emotions in listeners (5, 6) such as fear (7), sadness (5, 8), joy (9), pleasure (10), and positive emotional chills (11). Music not only evokes strong subjective feelings in listeners (12) but also stimulates a broad network for emotional processing and emotion recognition in the human brain (1, 13). Affective processing usually involves a broader cortical and subcortical network of brain systems (14), and music as a non-verbal and presumably direct channel of emotional communication can elicit neural processing for affect recognition in many of these subsystems and networks (15). Musical emotions thus seem key to a mechanistic understanding of the affective brain circuits (13, 16).

Musical emotions have been shown to trigger neural processing in the auditory system (low-level auditory cortex AC, higher-order superior temporal cortex ST) (5, 17), fronto-insular system (IFC inferior frontal cortex, aINS anterior insula) (12, 18), dorsal (Cd caudate nucleus) (11, 19) and ventral striatum (NAcc nucleus accumbens) (4), motor systems (MC motor cortex, PMC premotor cortex, Cbll cerebellum) (20, 21), and limbic systems (6, 22). These brain systems seem to support different mechanisms for analyzing the affective meaning of music, such as acoustical sound analysis and (predictive) temporal soundtracking, affective appraisal and categorization, salience detection and reward coding, and (in-)voluntary action tendencies (1). One of the central roles in this neural network might belong to the limbic system (6, 23). The limbic system provides relevant neural mechanisms to perform affective distinctions, such as discriminating complex affective meaning in the hippocampus (HC) (5, 22) as well as processing socio-affective associations and music-related values in the orbitofrontal cortex (5, 24). Furthermore, the amygdala (Amy) as a central hub in the limbic circuit might basically detect and register affective information encoded in sound and sound changes (25), and might prepare and coordinate other brain circuits for affective processing given its central position in emotional brain networks (14, 26).

Concerning the amygdala, previous studies have often shown amygdala activity in response to musical emotions (1, 6). The amygdala seems to respond to the consonance/dissonance level of music as a proxy of general affective (un)pleasantness (3, 27), is sensitive to specific negative and positive emotions portrayed in music (28), regulates listeners’ arousal levels during music listening (29), and responds to sudden and affectively charged changes in music (12, 30). Amygdala activity thus seems to be triggered by many musically portrayed emotions and emotional sound features and also influences functional connections to other brain systems, such as the auditory system (AC), limbic and paralimbic systems (HC, NAcc), and frontal systems (IFC) (1). The amygdala is furthermore composed of different subnuclei with different functional roles according to input and output nodes in the amygdala complex (6), and with different sensitivities to musical emotions. For example, the superficial subnucleus of the amygdala responds more to unpleasant music (9), whereas the laterobasal subnucleus responds more to pleasant music (27). These reports overall seem to confirm the notion of the amygdala being a central hub in the neural network for processing musical emotions and associated mechanisms (13, 16). However, the reports on the involvement of the amygdala as well as the limbic and paralimbic system in processing musical emotions are not very consistent overall. Based on a previous meta-analytic report (1), the probability of significant amygdala activity in responses to musical emotions is only about 50%, and the probability for other limbic and paralimbic activity is about the same or even lower. Although methodological differences across studies might contribute to this inconsistency, there might also be some specific experimental limitations and factors of previous setups, which we tried to overcome here.

One of these factors concerns the use of pre-recorded music as stimuli (31), especially in the case of human neuroimaging paradigms (6, 15). Although recorded music can powerfully portray musical emotions and induce an emotional response in listeners, such pre-recorded music is usually non-dynamic and non-adaptive. This non-adaptive nature mainly concerns individual listener responses to certain types and features of music, which can only be dynamically changed and adapted in live performance settings. Some listeners might not show emotional responses to certain musical pieces while other listeners do. Researchers have tried to overcome this issue using musical pieces individually selected by listeners (10). This approach has been successfully used to study the most positive and pleasurable emotional experiences when listening to music, but negative and aversive emotional responses to music have not been investigated in this manner so far. Furthermore, while this approach takes into account individual emotional responses to music, it is still non-adaptive in nature with regard to the musical performance.

Another factor is the non-adaptive nature of pre-recorded music. Unlike pre-recorded music, live music allows adapting and modulating the performance according to the emotional responses of listeners. Despite tremendous advancements in recording technology across the last century, millions of music fans still flock to live concerts worldwide, presumably because the adaptive and dynamic nature of live musical performances can induce stronger and more consistent emotional responses. Live music elicits greater body movement (32) and synchronizes bodily arousal (33) and brain states in the audience (34), and it reduces stress (35) and stress hormones (36) significantly more than recorded music. Live music also connects the brains of musicians with the brains of a listening audience (37). Using live and dynamic music might thus also elicit stronger and more consistent overall, and specifically limbic, brain responses in listeners. This effect might be consistent with previous observations that more expressive, rather than mechanic (38), as well as more improvised, rather than imitated (39), recordings of musical pieces elicit higher amygdala activity.

To investigate the ability of adaptive and dynamic live music to elicit more consistent brain activity in the limbic brain system as well as in the broader neural network for processing musical emotions, we implemented a closed-loop music performance setup for a human neuroimaging environment (Fig. 1). Previous setups that connected listeners’ brain responses with online music generation algorithms demonstrated general emotional and cognitive effects in listeners, such as reduced depressive symptoms (40), better memory performance (41), and increased brain alpha oscillations (42). We here introduced a setup that connects the live music performance of human piano players with the neural limbic responses in listeners based on a real-time functional MRI (fMRI) approach (25). This setup had four main features: 1) piano players were asked to modulate their live music performance on 12 pleasant and unpleasant musical pieces specifically composed for this experiment in order to increase and maximize amygdala activity in listeners in real time; 2) piano music was chosen because piano is a popular and familiar solo instrument, and pianists can play a melody simultaneously with harmonic accompaniment, both important for conveying and inducing emotions; 3) we chose the left amygdala as a target region for neurofeedback setup, as it has been shown to more reliably respond to emotional music than the right amygdala (1, 6); and 4) we chose to compare neural activity during the live music performance with pre-recordings of the same musical pieces by the same pianists as the optimal baseline condition that allows to control for critical features of our experimental design. Specifically, during both conditions (live, recorded), we presented the same musical pieces played by the same pianists, with the major difference being the feedback loop (live) compared with the no-feedback condition (recorded). We predicted finding significantly higher neural activity in the limbic target region and the broader neural network for music emotion processing with our setup, compared with a pre-recorded music setup for human neuroimaging, given its adaptive and dynamic nature.

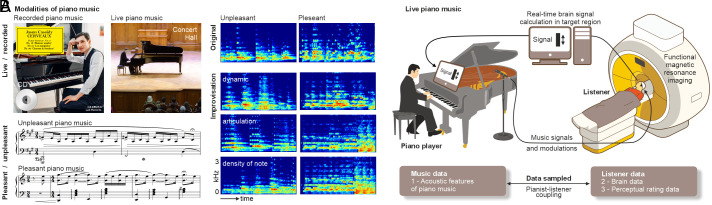

Fig. 1.

Closed-loop music performance setup linking a piano player and a human listener during real-time neuroimaging. (A) The study compared neural brain responses in the amygdala and the broader brain network for decoding emotions in music while listening to live (live) and recorded (rec) piano music. The Lower panel shows example scores for unpleasant and pleasant piano music. Example spectrograms of two recorded musical pieces, as well as the three types of modulations (dy dynamic, ar articulation, de density of note) that produced variations in the performances of each piece. (B) During the live musical performance condition, two piano players (n = 2, 1 male, 1 female) independently performed and modulated the musical pieces based on neural feedback from listeners’ (n = 27) amygdala activity that was quantified with functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) in a real-time neuroimaging setup. We recorded and acoustically analyzed the performed musical pieces of the piano players, and we quantified brain activity and perceptual ratings from listeners in response to listening to the performed musical pieces.

Results

Live Music Drives Amygdala Activity for Processing Musical Emotions.

The major goal of this study was to investigate whether musical emotions expressed in live piano music can elicit stronger and more consistent activity in the amygdala as a central region in the limbic brain system for affective processing. Emotions expressed in live music can be more engaging, dynamic, and adaptable to listeners’ neurocognitive responses that support affective processing. We therefore compared neural dynamics in the amygdala when humans listened to musical performances that were dynamically adapted to their amygdala signal, with amygdala activity in the same listeners when presented with prerecorded, and thus non-adaptive, versions of the same musical pieces. This study only included participants who lacked an in-depth musical education. These participants were thus labeled as “non-musicians” according to common standards (43, 44).

Two professional pianists (1 female, 1 male) played twelve short pieces (30 s) that were composed of four different musical themes, two of which were of a pleasant and positive valence and two of which were of unpleasant and negative valence. We here refer to the valence of these musical pieces as being “pleasant” or “unpleasant”, being aware that unpleasant music does not necessarily evoke only negative feelings in listeners or vice versa (8). The emotional conditions were labeled in this manner to avoid confusion with notions of negative and positive effects in terms of statistical outcomes. Three different musical variations (articulation, note density, and dynamics) of all musical pieces were presented to the participants, resulting in a total of 12 different pieces. This set of musical variations was introduced to standardize the possible variations to a certain degree and to make them comparable across piano players and listening participants. These musical variations were separately introduced as either 1) “articulation” variation, which describes how a note or musical event is played and can be considered a measure of expressiveness; as 2) “density of note” variation, which refers to how many musical events are played within a given unit of time and can be a measure of the complexity of a piece; or as 3) “dynamic” variation, which refers to the energy or volume of a sound or note. The musical variations were introduced both during pleasant and unpleasant music conditions and also both during the recorded and the live musical conditions.

Participants had two modes of listening during the experiment referred to as “live” and “recorded” conditions. The recorded condition served as the baseline condition in that it presented the same musical pieces played by the same pianists as the live condition, but these pieces were pre-recorded before the experiment and thus remained unmodulated as no neural feedback was adaptively included here during the pre-recording session.

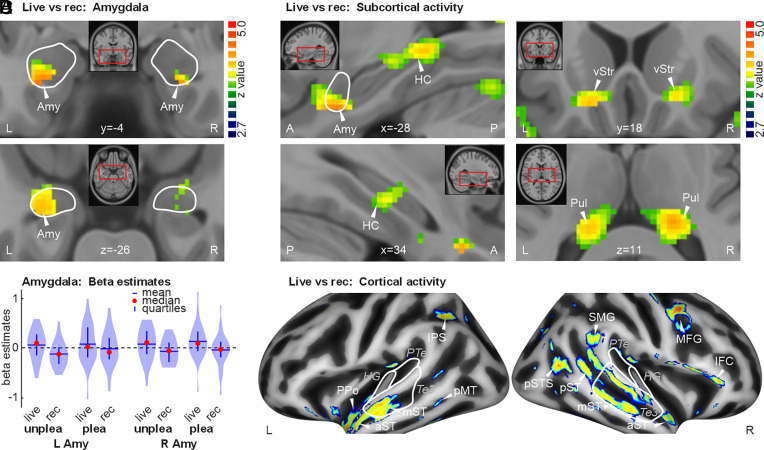

When listening to both pleasant and unpleasant live music, participants showed significantly higher activity in the left amygdala, which was the target brain area for neural upregulation by the piano players in our study (Fig. 2 A and B). In addition to this spatially extended and significant activity in the left amygdala (MNIxyz [-28 -1 -26], z = 3.99), we also found higher activity in the right amygdala in the live music condition, although of a smaller spatial extent ([26 - 1 -28], z = 3.73). Thus, emotions expressed in live and adaptive musical performances can trigger stronger and more consistent amygdala activity, but also in a broader brain network for emotional processing from music.

Fig. 2.

Brain activity for live versus recorded music across pleasant and unpleasant music. (A) Brain activity (n = 27) in the left and right amygdala (amy). White lines demarcate the amygdala. All brain activity is thresholded at a voxel threshold of P < 0.005 and a cluster extent threshold of k > 51, resulting in a combined threshold of P < 0.05 corrected at the cluster level. (B) Brain activity (beta estimates) extracted from peak locations of activity in the left and right amygdala and plotted separately for pleasant and unpleasant music in the live and recorded condition (rec). Amygdala activity was generally higher for the live compared to the recorded music condition. (C) Subcortical activity for [live>rec] music in the bilateral HC, ventral striatum (vStr), and pulvinar (Pul). (D) Cortical brain activity for [live>rec] music in left intrap-arietal sulcus (IPS), right lateral frontal cortex (MFG, IFC), and in bilateral superior temporal cortex (ST). Left ST activity was predominantly located in the anterior part covering planum polare (PPo), anterior (aST), mid ST (mST), and posterior MT (pMT). Right ST activity was broadly extended from anterior to posterior ST (aST, mST, pST), extending posteriorly also into the posterior superior temporal sulcus (pSTS) and supramarginal gyrus (SMG). White lines correspond to primary (HG), secondary (PTe planum temporale), and higher-order AC (area Te3).

Musical Emotions Elicit Activity in Many Cortico-Subcortical Regions.

The processing of emotions expressed in music involves not only the amygdala but also a broader brain network of cortical and subcortical brain regions. We accordingly found additional significant brain activity for the live compared with the recorded music condition in several subcortical brain regions of the limbic system (HC, vStr ventral striatum) and the thalamus (Pul pulvinar) (Fig. 2C and SI Appendix, Table S1). Cortical activations were found in secondary (PPo planum polare, PTe planum temporale), higher-order (a/m/pST anterior/mid/posterior superior temporal cortex), and associative auditory cortical regions (pMT posterior middle temporal cortex, pSTS posterior superior temporal sulcus). Additional activations were also found in fronto-parietal regions of the ventral (IFC inferior frontal cortex) and dorsal processing stream (IPS intra-parietal sulcus, SMG supramarginal gyrus, MFG middle frontal gyrus) (Fig. 2D). Comparing brain activity for the recorded versus the live music conditions did not reveal any significant activity in the amygdala and other regions of the brain. This result highlights the notion that live music can indeed specifically trigger brain activity in humans when performed in adaptation to listeners’ responses. This finding seems to apply to performances of both pleasant and unpleasant musical pieces.

Differential Brain Effects of Pleasant and Unpleasant Music.

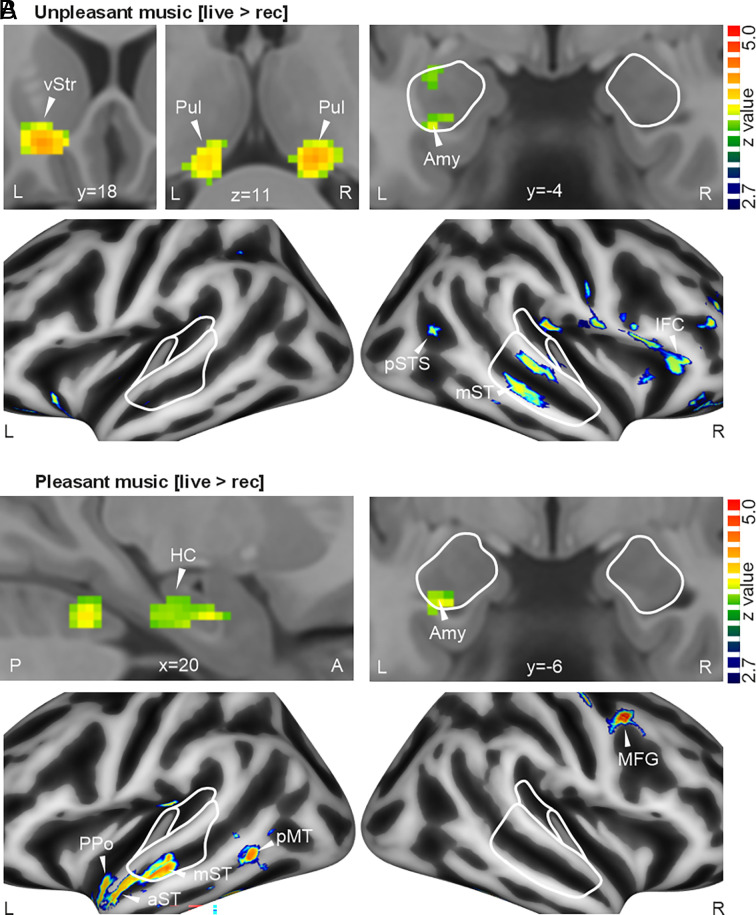

When we compared the neural effects separately for pleasant and unpleasant music, we found a common effect for both types of music in the left amygdala (Fig. 3 A and B; unpleasant [-30 -6 -16], z = 2.93; pleasant [-28 -8 -28], z = 3.04), which was the target for neurofeedback modulation during both conditions in the live music setup. Besides this common neural effect in the left amygdala, we found some differential effects in other brain areas (SI Appendix, Table S2). During live versus recorded unpleasant music, we found activity in bilateral Pul, left vStr, left IFC, and especially the right AC (mST, pSTS). During live versus recorded pleasant music, this auditory cortical activity was more lateralized to the left hemisphere (PPo, aST, mST, pMT), additional to right MFG and right HC activity. Taken together, live pleasant and unpleasant music seem to commonly elicit significant activity in the amygdala as well as common and differential activity in a broader cortico-subcortical brain network. The dynamics in this network were investigated in the next step of the data analysis.

Fig. 3.

Brain activity for live versus recorded music separated into pleasant and unpleasant music conditions. (A) Subcortical (Upper) and cortical activity (Lower) for [live>rec] music while listening to unpleasant music (n = 27). For areas and abbreviations, see Fig. 2. All brain activity reported in this figure is thresholded at a voxel threshold of P < 0.005 and a cluster extent threshold of k > 51, resulting in a combined threshold of P < 0.05 corrected at the cluster level. (B) Same as A, but for pleasant music.

Live Music Stimulates a Broad Interconnected Limbic-Cortical Network.

To determine the functional neural network architecture across the brain areas that were more active during live compared to recorded music, we used a Granger causality analysis (GCA) approach (Fig. 4). GCA determines the directional connectivity between brain areas during specific experimental conditions. For this GCA approach, we defined ROIs (regions-of-interests) that were based on functional activations that we revealed during the analysis of contrasting experimental conditions (Fig. 2). This explorative approach allowed us to further describe the functional properties of the activated brain regions in terms of their functional characteristics in the broader brain network.

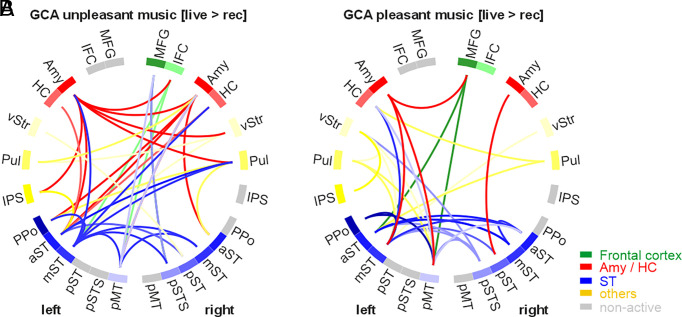

Fig. 4.

Patterns of functional brain connectivity for live versus recorded music listening. (A) Connectivity patterns (n = 324 trials for each condition) for unpleasant music and (B) for pleasant music. Colors indicate the seed region of the connection; connections are thresholded at P < 0.01, FDR corrected.

For unpleasant music, we found a neural network with significantly higher functional connections during the live compared to the recorded music condition (SI Appendix, Table S3). The network for live unpleasant music had three major features: First, the left amygdala was the seed of many connections to most other brain systems, such as the limbic system (right Amy, right vStr), left AC, and the fronto-parietal system. This finding highlights the notion that the amygdala not only shows significantly higher activity during live unpleasant music but also seems to subsequently stimulate and feed-forward information to other brain systems. As a second major feature, the right amygdalo-hippocampal, pulvinar, and frontal systems showed interconnectivity with the AC system, which highlights the role of the AC in the acoustic analysis of unpleasant musical emotions and its interdependency with other brain systems. The AC subregions also showed strong interhemispheric connectivity. And as a third major feature, the vStr targeted AC regions and the pulvinar.

Compared to this network for unpleasant music, the network for live pleasant music had similar features, but was less complex (SI Appendix, Table S4): First, the amygdala was the seed for connections to AC subregions and the frontal system, which again highlights the role of the amygdala in stimulating and forwarding information to other brain systems while listening to live pleasant music. Second, the AC subregions again showed strong interconnectivity between the left and right hemispheres, but only showed some minor interconnectivity with limbic brain systems (HC, vStr). The AC, however, was the target of many afferent connections from several brain systems (limbic, frontal, vStr, Pul), and this finding seemed more strongly lateralized to the left hemisphere in terms of targeted AC subregions. Taken together, there were commonalities and differences in the functional brain networks for live pleasant and unpleasant music, and this result was also reflected in the acoustic properties of these musical conditions.

Live Music Is Acoustically Different from Recorded Music.

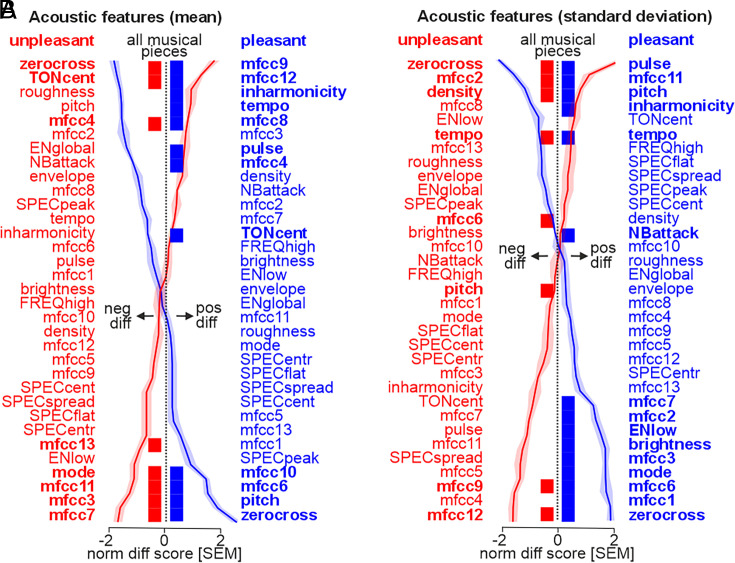

For all live and recorded musical pieces, we used the Music Information Retrieval (MIR) toolbox (45) to quantify 33 acoustic features that are commonly associated with unpleasant and pleasant emotions expressed in music (12) (SI Appendix, SI Methods). The 33 acoustic features belonged to six major categories: dynamics, rhythm, pitch, tonality, spectral features, and Mel-frequency cepstral coefficients (mfcc). For all features, we quantified the mean level across the 30-s musical performances as a measure of the overall acoustic profile of the musical pieces, but we also quantified the SD of these features as a measure of the dynamic nature of each feature. For the mean and the SD of the features, we specifically quantified the difference between the live and the recorded condition separately for pleasant and unpleasant musical pieces (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Acoustic differences between live and recorded music for 33 acoustic features. (A) Difference of mean acoustic features for contrasting [live>rec] across all modulation types (Left) (n = 27). Features are quantified as the mean over the 30-s period for each trial. Red indicates pleasant music and blue indicates unpleasant music; features are sorted from most negative to most positive difference (and vice versa). Bold feature names and bold bars in the midline indicate significant differences (P < 0.0001, FDR corrected), with higher mean features for live music plotted toward the Right, and lower mean features toward the Left. (B) Same as A but for the difference of the SD as a measure of the variation of the musical features over the 30-s period (n = 27). Significance at P < 0.0001, FDR corrected.

For the mean levels of each acoustic feature (Fig. 5A), live pleasant and unpleasant music showed significant negative and positive differences to recorded music along several mfcc features. These mfcc features (mfcc1-13) describe the shape, structuredness, and complexity of the spectral profile of an auditory signal and are often used in music research to describe aspects of the musical timbre. Live pleasant (mfcc 4/8/9/12) and unpleasant music (mfcc 3/7/11/12) showed less power on several broadly-spaced mfcc’s, while having a stronger power on other specific mfcc’s, such as mfcc4 (medium-level spectral profile) for unpleasant music and mfcc6/10 (high-level spectral profile) for pleasant music. This finding might indicate that live music has a less defined timbral quality and structure overall, probably due to their improvised nature and their unique adaptations to each listener. But some specific mfcc components seem to be amplified in live music. In addition to the mfcc modulations, both live unpleasant and pleasant music was noisier than recorded music (zero-crossing rate feature, denoted as “zerocross”). There were also specific differences between live pleasant and unpleasant music compared to recorded versions of these conditions. Live unpleasant music had a higher tonal center (TONcent) and was performed to acoustically appear with a more salient minor mode (mode) as compared to the recorded unpleasant music. Live pleasant music had a lower tonal key (TONcent), beat clarity (pulse), tempo, and inharmonicity, but had a higher mean pitch (pitch).

For the SD of the acoustic features as a proxy for the dynamic nature and range of the musical pieces, there were again differences concerning the mfcc features for live compared to recorded music (Fig. 5B). Whereas there was lower power variation in the higher mfcc range for live unpleasant (mfcc9/12) and live pleasant music (mfcc11), there was higher power variation in the lower mfcc ranges (unpleasant music: mfcc2/6, pleasant music: mfcc1/2/3/6/7). There was also commonly lower pitch (pitch) and higher noisiness variations (zerocross) for live unpleasant and pleasant music. Additionally, live unpleasant music had higher variations in event density (density) and tempo (tempo). Live pleasant music, on the other hand, had fewer variations in tempo (tempo), beat clarity (pulse), inharmonicity, and musical attacks (NBattack). But there were more variations for musical brightness, mode, and low energy rate (ENlow) for live pleasant music. Live modulations in music thus overall show a differential acoustic profile compared to recorded music. Live modulations can take many different forms, and we investigated three types of modulations in this study.

Differential Live Modulations in Musical Performances.

For pleasant and unpleasant music, the piano players were allowed to introduce three different types of modulations in the musical performance, which were referred to as articulation, density of note, and dynamic modulations. We therefore also quantified acoustic differences between live and recorded music for the three modulation types (SI Appendix, Fig. S1). These acoustic differences largely followed the general variations that were found across the modulation types (Fig. 5 A and B), but also revealed some more specific differences.

For the mean level of acoustic features (SI Appendix, Fig. S1A), especially for density of note for live versus recorded unpleasant music revealed some higher pitch, inharmonicity, and spectral spikiness (SPECflat), combined with lower high-frequency power (FREQhigh) and contrastiveness (ENlow). For live pleasant music, again the modulation type of density of note was associated with additional specific features, such as lower event density (density) and musical attacks (NBattack) as well as higher spectral peak variability (SPECpeak) and contrastiveness (ENlow). The latter was contrary to the dynamic modulation type during live pleasant music, which showed lower contrastiveness (ENlow).

For the SD of acoustic features, the three modulation types also revealed additional specificities (SI Appendix, Fig. S1B). For live unpleasant music, the dynamic modulation type showed more variation in attacks (NBattack), the articulation modulation had more variable higher mfcc ranges (mfcc8/11) and tempo variations, and the density of note modulation type had more variations in tempo (tempo), pitch (pitch), event density (density), and contrastiveness (ENlow). For live pleasant music, there were additional specificities for the three modulation types. The dynamic modulation type had more variations in major/minor mode but fewer variations in spectral/pitch features (SPECentr, SPECflat, FREQhigh, pitch) and inharmonicity. The articulation type had more brightness (brightness) variations, while the density of note type had more variations in lower timbre ranges (mfcc2/4/6) and lower variations in tempo.

It might be thus that live musical performances more dynamically and temporally adjust to audience response in terms of the mean and variation of musical features, and that these adjustments should be reflected in temporal correlations between musical, perceptual, and brain signals.

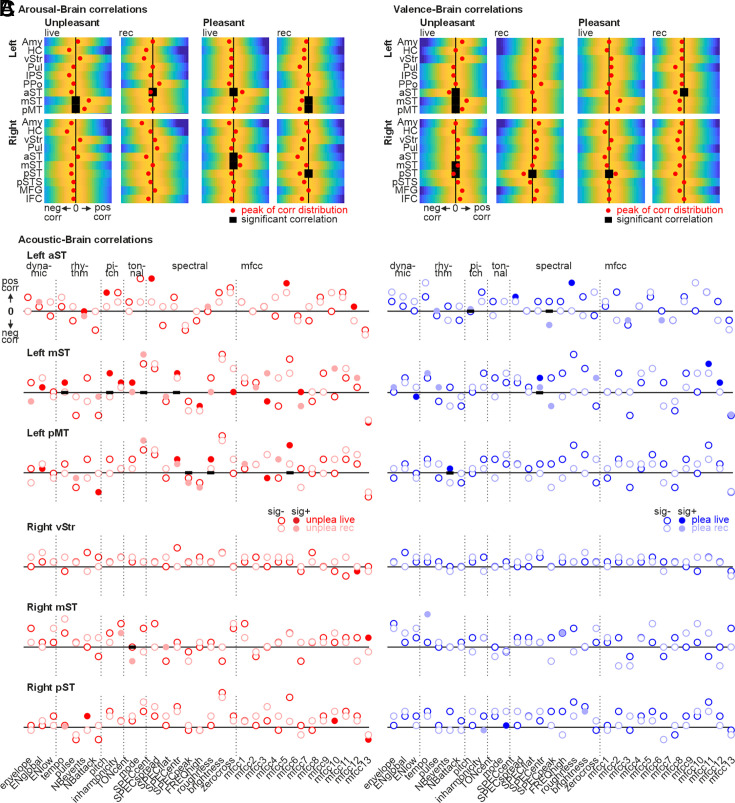

Brain Responses to Live Music Correlate with Perceptual Impressions and Musical Features.

To quantify whether musical performances during the live and the recorded music condition were temporally linked with neural activity, we performed a correlation analysis with the 9 left and 10 right hemispheric regions that showed significantly higher activity during the live versus recorded condition across several comparisons performed (Figs. 2 and 3). For this purpose, we extracted the signal time course in these 19 brain regions, shifted them by 4 s to account for delays in the hemodynamic response function (HRF) (46), and correlated them first with the perceptual ratings of the listeners (arousal, valence), and second with the 33 acoustic features of the musical pieces.

In terms of the perceptual ratings, all listening participants performed dynamic arousal (low-to-high arousal) and valence ratings (negative-to-positive) for each live and recorded musical piece that they heard during the neuroimaging experiment (SI Appendix, SI Methods). These dynamic ratings were downsampled to the sampling rate of the functional brain signal and compared with correlation analyses (Pearson correlation). For the correlation analysis between the perceptual arousal ratings and brain activity (Fig. 6A), we revealed three major observations: First, all significant correlations were associated with subregions of the AC as no significant correlations were found with other brain areas; second, live music only showed positive correlations with brain activity, while recorded music showed only negative correlations (aST, mST, pST, pMT); and third, correlations with live unpleasant music were associated with mid-posterior AC subregions (left mST, left pMT), while correlations with live pleasant music were associated with mid-anterior AC regions (right mST, left/right aST).

Fig. 6.

Association between brain activity and perceptual ratings and musical features. (A) Distribution of correlation coefficients between arousal ratings and brain activity in Left (Upper) and Right ROI (n = 19, Lower) as defined in Figs. 3 and 4. All correlations are thresholded at P < 0.01, FDR corrected. Significance is indicated by bold black midline bars. Red dots indicate a positive or negative difference for the peak of the distribution compared to the distribution originating from random sampling (permutation analysis, n = 500 permutations). (B) Same as A but for valence ratings. (C) Same as A and B but showing the correlation coefficients for the association of musical acoustical features (n = 33) with brain activity in Left and Right ROIs (n = 19). Shown are the peak levels of the correlation distributions (comparable to the red dots in A and B); filled circles indicate significance, P < 0.01, FDR corrected.

For the correlation analysis between perceptual valence ratings and brain activity (Fig. 6B), we revealed three major observations: First, again there were only significant correlations with AC regions; second, for recorded music we only found negative correlations (aST, pST), while live music revealed positive correlations with pleasant music (right pST) as well as a mix of positive (left/right mST, left pMT) and negative correlations (left aST, right pST) with unpleasant music. Overall, brain activity for live music showed many mostly positive correlations with the emotional perceptual impressions as reported by the listening participants. Recorded music did not reveal any positive correlations.

In the second part of the correlation analyses, we quantified the association between acoustic features of the musical pieces and brain activity in listeners (Fig. 6C). We determined significant correlations and correlation differences in a two-step procedure: First, any correlation distribution had to be significantly different from zero (Fig. 6C, filled circles), and second, there had to be a significant difference between the live and recorded condition (Fig. 6C bold black bars). We only report significant findings that fulfilled both conditions. These findings had four major features: First, again, we only found correlations with AC regions since no other region showed significant correlations. The only exception was a correlation between the right vStr and the mfcc12 feature, but this correlation fulfilled only one of the significance conditions. Second, there were more correlations with the left than with the right AC regions. Third, there were more correlations with unpleasant than with pleasant music.

And fourth, live music again revealed mostly positive correlations, while recorded music mostly showed some negative correlations. Specifically, live unpleasant music revealed positive correlations in left AC regions with some rhythm (tempo), pitch (pitch), spectral (SPECflat, FREQhigh), and mfcc features (mfcc5). Live pleasant music revealed positive correlations with rhythm (NBevents) and spectral features (SPECflat). Overall, brain activity during live music listening seems not only to correlate mainly positively with the emotional perceptual impressions of listeners but also with the central acoustic features of live music performances that point to entrainment processes between the musical performance and brain responses in listeners.

Discussion

Most humans enjoy listening to music, often because of the power of music to convey and elicit emotions in listeners. Similarly, most musicians enjoy performing music because of its power to express emotions. While recorded music allows the encoding of emotions in music and the modulation of musical emotions over time, it cannot fully anticipate, dynamically adapt, and potentially enhance listeners’ responses on an individual level. Live musical performances on the other hand enable musicians to directly influence and intensify emotional responses in the audience with dynamic performance modulations based on the audience’s response. Music thus has been assumed to be an ideal modality to stimulate intensive and extensive emotional responses in listeners and to understand neural mechanisms in affective brain circuits (13, 16).

Previous studies used recorded music and could show that the human brain can strongly respond to emotional music and musical features. Many studies specifically also reported activity in central neural systems of the emotional brain network in listeners, especially in the amygdala in response to recorded music (1, 6). In spite of the assumed power of music to elicit emotions and to trigger neural responses for emotional processing, evidence for consistent brain responses to music has been inconsistent to date. This inconsistency across findings might be related to the non-adaptive nature of recorded music, which might be able to trigger but not maximize emotional and neural processing in listeners. In our study, we included a record music condition that was similar to previous studies. The recorded music condition served as a baseline against which we compared the emotional and neural effects of live music. We targeted the left amygdala as a central node in the emotional brain network (6) and could observe that live, adaptive emotional music could indeed elicit significantly higher activity in this brain area compared to recorded music. Thus, a live music setup that allows maximizing emotional expressions in musical performances, and consequently maximizing limbic brain response in listeners, is able to elicit significantly higher amygdala activity than previous setups. This significantly higher activity in the amygdala is probably based on the fact that only live music allows affectively (more) relevant modulations and improvisation in the performance. Furthermore, only live musical performances can be adapted and individualized to responses in listeners to maximize their brain responses in target regions, while these responses then serve as feedback to the musicians in a closed-loop setup.

Furthermore, the study included both pleasant and unpleasant musical pieces, and both types of emotional music seem to be able to elicit significantly higher amygdala activity compared to the same musical pieces presented as recordings. The amygdala generally responds to pleasant and unpleasant music (3, 5, 30), but different amygdala subnuclei might be sensitive to certain musical emotions. The superficial subnucleus of the amygdala responds more to unpleasant music (9), whereas the laterobasal subnucleus responds more to pleasant music (27). All peak activity locations in our study were most likely located in the laterobasal nucleus, which is the subregion of the amygdala that typically integrates and emotionally assesses information provided by sensory cortices, especially information from the neural auditory system (6). This process might be especially relevant when listening to live and dynamic musical performances, which accentuate important musical features for emotional portrayal.

Live music not only elicited significantly higher activity in the amygdala of the listeners but also in a broader neural network that is essential for processing emotions from music. This network included the HC, potentially associated with the retrieval of musical associations (6) and aesthetic evaluations (22), the ventral striatum for processing the reward quality (4) and reward prediction errors of music (47), and the AC for sound analysis (48) and emotional information integration (49) when listening to live compared to recorded music. The network also included the intra-parietal sulcus as part of the dorsal auditory stream for sensory-motor integration (50) and the right lateral frontal cortex for tracking sound variations (51) and emotional valuations of sounds (52). Of note, it is here again that this common brain activity, which was similarly also reported with recorded music in previous studies (1, 13), was significantly increased in our study during the live condition. Live and dynamic music thus seems to stimulate both the amygdala and the broader brain network for music emotion processing better than recorded music.

Besides finding activity in well-known brain areas for musical emotional processing, we also revealed three important and findings concerning this neural network: First, we observed a previously unreported consistent activity in the pulvinar nucleus of the thalamus in response to live music. The pulvinar is central to attentional orienting and regulates neural information flow based on attentional demands (53). Live music might induce more attentional capture given its dynamic nature, which consequently also requires controlling the neural information flow in the broader neural network and especially in sensory cortices. The pulvinar also helps to sharpen AC processing for sound analysis while increasing the signal-to-noise ratio (54). This neural support for auditory processing might be especially relevant for live unpleasant music, as found here. Second and similarly, we found that activity in the ventral striatum was more relevant for processing live unpleasant music. This observation seems rather unexpected given that pleasant rather than unpleasant music typically triggers reward mechanisms associated with the ventral striatum (55). The ventral striatum, and especially the nucleus accumbens, also mediates aversive states (56) and supports the prediction and duration of aversive events (57), which seems highly relevant for live unpleasant music. For live music, aversive coding while listening to unpleasant music seems more important than reward coding for pleasant music. Third, neural activity in the AC showed a laterality effect with unpleasant music predominantly activating the right AC, while pleasant music predominantly activates the left AC. This finding could confirm previous assumptions for general brain lateralization in response to pleasant and unpleasant music (58), but our data especially qualify this assumption for neural processing in the AC. This lateralization might be related to the neural processing modes for pleasant and unpleasant music (59). Unpleasant music might receive a more natural and holistic processing in the right AC (60), while pleasant music might receive a more analytical and structural analysis in the left AC (61, 62).

Processing emotions from live music thus seems to involve increased activations in the amygdala and a broader neural network. To investigate the information flow in this network, we performed a directed functional connectivity analysis. For both pleasant and unpleasant music, we found that the functional connectivity between many regions of the network was significantly increased during the live compared to the recorded condition. A relatively extended connectivity pattern was especially found for live unpleasant music. This connectivity pattern had several important features: First, the left and partly also the right amygdala had a central position in this network showing many efferent connections to all other major brain systems that were active during the live conditions. Stimulating and maximizing amygdala activity based on neurofeedback during live unpleasant music seems thus to also stimulate functional connections to other relevant brain areas for musical emotion processing. Second, there were extensive intra- and inter-hemispheric connections for the AC, with additional inter-connections with the amygdalo-hippocampal complex, pulvinar, and frontal system. The auditory system for sound analysis and affective sound information integration thus seems to have an additional and complementary important role for processing emotions from live unpleasant music as for the amygdala (6). Third, the ventral striatum showed efferent connections to the AC and to the pulvinar, probably signifying the relevance of sound information to guide sound analysis (4) and attention orienting (53).

Compared to the functional network for processing live unpleasant music, the functional network for processing live compared to recorded pleasant music had a complex but slightly reduced profile: First, the amygdala showed only connections to the AC and the frontal system; second, while the AC showed similar intra- and inter-hemispheric connections as for live unpleasant music, it was predominantly the target of top–down afferent connections from other systems, such as frontal system, ventral striatum, and pulvinar. Live pleasant music thus seems to involve central functional mechanisms in the amygdala for emotional processing in an amygdala-frontal-auditory triangle that might lead to a broad top–down control of acoustic and emotional integration in the AC. The AC is largely involved in processing pleasant musical emotions, especially of a highly arousing nature (5), and seems to integrate the relevant information from various neural sources. This might be particularly based on the specific acoustic and perceptual nature of live compared to recorded music.

We accordingly found significant acoustic differences between live and recorded music of the same musical pieces in general, but also for the three different modulation types. These differences might originate from the fact that live but not recorded music in this study was adapted to listeners’ brain responses. Live music overall had some general features that indicated their increased improvised and more expressive nature (38, 39), such as being noisier and having a less well-defined timbral quality. Besides this improvised nature, live music might also utilize acoustic features and feature variations that highlight the specific emotional quality of the music and that might intensify emotional responses in listeners (12). For example, live unpleasant music was performed such as having a stronger dominance or saliency of the minor mode compared to recorded unpleasant music. Live pleasant music had a higher mean pitch level than recorded pleasant music but also seemed to be more harmonic and smoother. This smoother quality might be based on the fact that there was less of a beat and musical attack structure present in live pleasant music. The acoustic difference profiles for the three different modulation types largely followed these general difference profiles for live versus recorded music but also pointed to specific and differential acoustic properties. The acoustic difference between live and recorded music largely confirmed the intended variations for the three modulation types, such as higher contrastiveness and spectral spikiness for the density of note modulation, lower contrastiveness and more attack variations during the dynamic modulation, and more brightness and tempo variations during the articulation type modulation. These results altogether highlight the common and differential strategies that can be used during live performances to introduce acoustic and perceptual variations and that also depend on individual responses in the listening audience (32, 63).

Individual responses in listeners can only be taken into account by musicians during live music performances. If live music performance is successfully adapted to and modulated by listeners’ responses, this behavior should result in correlations between music performance features produced by the piano players on one side, and the processing of musical and affective features in listeners on the other side. We tested such adaptation processes on two levels. First, in listeners, we tested for the correspondence between their neural brain activity and their perceptual impressions of the perceived music in terms of arousal and valence ratings. Interestingly, only live music was able to elicit positive brain-perception correlations in listeners, possibly related to the fact that live music might better attract listeners’ attention, which could support synchronization between processing levels (64). Recorded music only elicited a negative brain-perception correlation, probably based on the non-adaptive and rather predictable nature of recorded music. Another important observation was that brain-perception correlations were only significant in the AC. The amygdala as the target of the neurofeedback loop seems thus only indirectly involved here, probably by functional connections between the amygdala and the AC, as discussed above. The AC however seems ideally suited for the brain-perception correlations, given the computational nature of the AC for emotion information integration (1, 6, 25).

In the second approach for testing entrainment processes, we quantified brain-acoustic correlations, which finally connect the musician (musical acoustic features) with the listener (brain responses) as the essential feature of the closed-loop social setup in our study. Again, there were mostly positive correlations for live music with the AC subregions, while recorded music mostly showed negative correlations. Many of the positive correlations for live music concerned rhythm and spectral features, highlighting the notion that both temporal and spectral features connect musicians and listeners in live performances.

Overall, our data provide evidence that live music can more consistently elicit amygdala activity in response to musical emotions than previous setups using recorded music. Brain stimulation for affective processing with live music not only shows significantly increased brain activity in common neural networks for music processing but also leads to observations in terms of neural mechanisms for affect processing from music. Live music is acoustically different from recorded music, and only live settings lead to a close coupling between musical performances and emotional responses in listeners, which is a central mechanism for music as a social entrainment process.

Materials and Methods

Participants.

Twenty-seven healthy participants (15 female, mean age 27.97 y, SD 5.17) took part in the experiment. The sample size resulted from the calculation of the optimal size based on effects reported in previous studies in order to achieve a statistical power of 80%. A previous study reported amygdala effects in response to emotional music of about Δm ~ [0.080 0.085] (SD ~ 0.15) (3) suggesting a sample size of n = 27 to 30. A previous real-time imaging study (25) with amygdala feedback to live versus recorded affective voices suggested effects on amygdala activity of Δm ~ [0.57 0.66] (SD ~ [1.01 1.18]) suggesting a sample size of n = 21 to 36. Based on these estimated effects, we targeted a final sample size of n ~ 28 participants.

Only non-musician individuals were recruited for this study as listening participants. The notion of non-musicians was operationalized as having no music education, no regular musical practice before age 10, and no current or past regular musical practice for more than 5 y in a row. All participants reported having normal hearing and that they had no history of any psychiatric, neurological, or toxicological issues. The study was approved by the Swiss governmental ethics committee. All participants provided informed written consent in accordance with the regulations of the ethical and data security guidelines of the University of Zurich.

Experimental Stimuli.

Naturalistic piano pieces (30-s duration) composed for the study to induce pleasant and unpleasant emotions were used as auditory stimuli and played by two professional pianists (referred to as “musicians”) from the Zurich University of the Arts (ZHdK, Switzerland) (1 female, 1 male; mean age 27.50 y, SD 0.70) (Fig. 1A). The musical pieces were composed to provide the basic musical structures for the piano performances but were mostly in a style of themes similar to “Jazz standards” to allow musical modulations and improvisations. These pieces were differently played and interpreted as a function of the two experimental conditions: a) Prior to the main fMRI experiment, the two musicians were invited to a piano recording session to play the set of piano pieces on a digital piano (Roland® FP 90, Japan). This first condition is referred to as the recorded condition. b) During the main fMRI experiment, the same musicians were invited to play the same musical pieces on the same digital piano, which was directly connected to both the headphones of the listening participants inside the MRI scanner and the experimental computer. This second condition is referred to as the live condition.

Musicians were informed and trained on how to introduce variations in their musical performance and in different acoustic features, which was of major interest for the fMRI experiment. For the piano recordings (recorded condition), pianists were asked to perform the four piano themes that comprised two positive/pleasant and two negative/unpleasant themes. Each musical theme included three recorded pieces very similar in their composition and emotion but diverging in terms of three distinct performance modulation types, namely, articulation (how a note or musical event is played, also referred to as the expressiveness of the piece), density of note (how many musical events played, also referred as the complexity of the piece) and dynamic (refers to the energy or volume of a sound/note). Musicians were instructed to perform the pieces during the recording session by closely applying these distinct musical variations while inducing pleasant or unpleasant emotions (respective to the piano theme) to an imaginary audience. All piano pieces, which were digitally recorded in 16-bit with a sampling rate of 44.1 kHz, were cut to an exact duration of 30 s and subsequently adjusted for loudness to an average sound intensity of 70-dB SPL. Music recordings and loudness adjustments were done using the Audacity software (https://www.audacityteam.org/).

The auditory material for the main neuroimaging experiment thus encompassed 12 piano pieces. The piano pieces were validated in a pre-experimental rating study (n = 7 participants, 4 female; mean age 29.14, SD 2.97) to confirm that their valence qualities were consistently either pleasant or unpleasant for human listeners (SI Appendix, Fig. S2).

Experimental Setup and Procedures.

Auditory stimuli from both the pre-recorded and live conditions were delivered binaurally through high-quality, MR-compatible earphones (MR Confon®, Magdeburg, Germany) at approximately 70-dB SPL. The fMRI experiment comprised eight experimental blocks during which participants were presented with either the recorded or real-time live music condition (4 blocks each). For both pre-recorded and live conditions, two of the four blocks were characterized as conveying a pleasant/positive emotion, while the other two corresponded to an unpleasant/negative emotion. With a duration of 7 min, each block consisted of an alternating sequence of seven resting periods with no auditory stimulation (30 s each) and six musical periods (30 s each) corresponding to one of the 12 musical pieces. The blocks always started with a resting period, followed by a 500-ms auditory cue which was presented 2 s prior to the beginning of each musical period (each period with a different piece of music). The order of the blocks, as well as the order of the musical pieces inside the blocks, were presented in a pseudo-randomized order and counterbalanced across participants. For each participant, half of the eight experimental blocks were equally distributed between the two musicians so that each musician played the four main conditions (pre-recorded pleasant, pre-recorded unpleasant, live pleasant, and live unpleasant). The total set of 12 musical pieces of either pleasant or unpleasant emotion was presented twice (once for the pre-recorded condition and once for the live condition) by each of the two musicians, leading to a total of 48 musical pieces. The recorded condition was the control condition for the study because during this condition the pianists did not have access to neural feedback from the participants and therefore could not directly influence participants’ brain signals.

Task of the fMRI Participants (“Listeners”).

Participants were instructed to passively but attentively listen to all musical pieces throughout the whole experiment. Participants were naïve to the fact that the experiment comprised live and pre-recorded conditions as well as a differential modulation in their amygdala activity during half of the conditions (live), induced by variations in the musicians’ performance. To ensure that participants listened attentively to the music, we asked control questions about the overall pleasantness of the music during each of the eight blocks. All participants gave valid and reasonable evaluations of the major pleasant or unpleasant nature of the musical pieces during each block.

Task of the Pianists (Musicians).

The pianists were asked to upregulate the activity of the listeners’ left amygdala using visual analog feedback presented on a screen and updated every 2 s. Prior to the data collection in the fMRI sessions, musicians were instructed and trained to dynamically induce variations in their musical performance that could potentially drive an increase in the mean left amygdala signal of the listeners.

Brain Image Acquisition.

We recorded functional imaging data on a 3T Philips Achieva Scanner equipped with a 32-channel receiver head-coil array and using a T2*-weighted gradient echo-planar imaging sequence including parallel imaging (SENSE-factor 2) with the following parameters: 30 sequential axial slices, whole brain, TR/TE: 2 s/30 ms, flip angle = 82°, slice thickness: 3.0 mm, gap: 1.1 mm, field of view: 240 × 240 mm, acquisition matrix 80 × 80 voxel, resulting voxel size 3 mm3, axial orientation. Structural images were acquired using a high-resolution magnetization prepared rapid acquisition gradient echo T1-weighted sequence and had 1-mm isotropic resolution (TR/TE: 6.73/3.1 ms, voxel size 1 mm3, 145 slices, axial orientation). Acoustic stimuli were presented via MR-compatible headphones (MR Confon®, Magdeburg, Germany) at an approximate 70-dB SPL both for the recorded and the live condition. Acoustic loudness for the live condition was adjusted for each participant and speaker prior to each experimental acquisition.

Online Functional Brain Data Analysis for Real-Time fMRI Neurofeedback.

The listening participant’s anatomical image acquired at the beginning of the fMRI session was used to manually and individually segment the left amygdala according to anatomical landmarks as used in previous studies (65, 66). The size of the segmented amygdala had a mean of n = 672.39 voxels in native space (SD 116.73, range 485 to 864) and a mean of n = 795.13 voxels in MNI (MontrealNeurological Institute) space (SD) 82.72, range 682 to 967; these values are based on a 1 mm3 isotropic voxel resolution of the anatomical images, which were used to segment the left amygdala. This segmentation procedure according to anatomical landmarks ensured that the major three subnuclei of the amygdala (laterobasal nucleus, centromedial nucleus, superficial nucleus) were accurately included and non-amygdalar structures were excluded in the ROI mask as previously shown (65).

The left amygdala was chosen in the current work because of its more reliable and consistent activation in response to affective and naturalistic music compared to the right amygdala (6). The segmented amygdala, which was used as an ROI mask, was then individually coregistered with some functional brain images recorded for this purpose before the main fMRI experiment. The real-time neurofeedback setup used both Turbo BrainVoyager software (Brain Innovation®, Maastricht, The Netherlands) and custom Matlab scripts. Online functional brain data analysis included the extraction of the left amygdala activity (mean signal of all voxels within the manually segmented mask) and real-time 3D head motion correction, spatial Gaussian smoothing, and temporal filtering (drift removal).

During live condition blocks, the representation of the percent signal change in the left amygdala was visually fed back on an extended screen to the musicians with a delay of 2 s from the image acquisition. The feedback signal was computed as a moving average over the current and the five immediately preceding functional images (average signal over the last 12 s) and then normalized to a percentage signal change (PSC) using a reference signal. This reference signal was newly calculated for each musical period during the live conditions by averaging the activation of the left amygdala over the last six images of the previous resting period. The PSC represented the percentage of signal increase/decrease in the moving average interval relative to the reference signal. The visual feedback was presented as a bar with a zero point that represented the reference signal and a range of ±1 PSC. The bar increased above the zero point or decreased below it according to the positive or negative PSC in relation to the reference signal.

Offline Functional Brain Data analysis.

fMRI analyses were performed using Statistical Parametric Mapping (SPM12, version 7771; fil.ion.ucl.ac.uk/spm). Functional images were first manually realigned to the anterior–posterior commissure plane. The pre-processing steps included realignment, slice timing correction, coregistration of the structural image to the mean functional image, segmentation of the anatomical image to allow estimation of normalization parameters, normalization of anatomical and structural images to the MNI stereotactic space, and an 8-mm isotropic Gaussian kernel smoothing.

The first level analysis was performed using a general linear model (GLM), in which the performance mode (live or recorded condition) and the valence condition (pleasant or unpleasant emotion) were entered into the GLM design on a trial basis and separately convolved with the canonical HRF. A single trial consisted of the 30 s of music presentation, with 6 trials included in each of the 8 blocks. Each block was modeled separately in the overall GLM design. Motion parameters, as estimated during the realignment pre-processing step (six realignment values), were entered as non-interest covariates, while the extracted loudness scores (see acoustic analysis of live and recorded musical pieces) were entered in the design as parametric modulators. For each of the four conditions (recorded pleasant, recorded unpleasant, live pleasant, live unpleasant), main contrast images were created while regressing out the activity related to parametric regressors (loudness).

The second-level whole-brain analysis included each of these four regressors in a flexible factorial design. We performed different contrasts between these experimental conditions, and all second-level whole-brain contrast images were thresholded at a combined voxel level threshold of P < 0.005 and a cluster extent threshold of k > 51. We determined this cluster corrected threshold by using the 3DClustSim algorithm implemented in the AFNI software (afni.nimh.nih.gov/afni; version AFNI_18.3.01; including the new (spatial) autocorrelation function extension) and based on the estimated smoothness of the residual images.

GCA to Estimate Directional Functional Brain Connectivity.

To estimate the directional functional connectivity of the amygdala and other ROIs that were activated according to the different contrasts performed, we conducted a GCA. This GCA determines how the time course in one brain region A can explain the time course in another brain area B. If this determination is significant, we assume that region A is directionally connected to region B. GCA was performed with the MVGC Multivariate Granger Causality toolbox (version 1.0) (67).

We defined the ROIs based on activations resulting from group-level contrasts between the live and recorded music conditions across and within the unpleasant and pleasant music conditions. We thus included 19 ROIs in total from bilateral AC (left PPo, aST, mST, pMT; right aST, mST, pST, pSTS); bilateral Amy, HC, vStr, and Pul; left IPS, right MFG, and right IFC. The exact MNI coordinates of the peak voxels of each ROI are marked with an asterisk in SI Appendix, Table S1. The ROIs comprised voxels within a 3-mm sphere around the peak location.

From each ROI, we extracted the time course of activity as the first eigenvariate across voxels within the ROI. For each participant, we epoched the ROI time course data for each trial in a time window from music onset to 44 s after onset to account for any delays in the BOLD response and its relaxation to baseline in each ROI. We pooled all epochs across all participants instead of estimating the GCA for each participant separately. This process is in accordance with previous fMRI studies (68, 69), since the number of trials for each participant is usually too low to provide an accurate estimation of brain connectivity. We used F-tests to assess the significance of the connections at P < 0.01 [false discovery rate (FDR) corrected]. For each of the four experimental conditions, we ran a separate GCA. To compare the music conditions, we subtracted the GCA results of the live from the recorded music condition for each emotion separately.

Correlation Analyses between Music Performance and Listener Data.

The time courses of musical features were subjected to correlation analyses with the time courses of both perceptual rating dimensions and with the time courses of brain data in different regions (19 ROIs as defined in the GCA). We downsampled the perceptual ratings to 0.5 Hz to match the sampling rate of the functional brain data (TR) and acoustic features. To evaluate the relationship between musical features and brain activity, we shifted the vocal features by 4 s (2*TR) to account for the delay of the BOLD signal (46).

We estimated the Pearson correlation coefficient of each musical feature to the perceptual ratings or to the brain data for each single 30-s music period of the main experiment for each participant separately. This process resulted in correlation coefficient distributions containing 324 coefficients for each musical feature within each of the four experimental conditions across all listening subjects (27 participants × 12 music periods per condition). For each of the four experimental conditions, the musical feature–brain data relationships resulted in distributions containing 627 coefficients (33 musical features × 19 ROIs) and the musical feature–rating relationships resulted in 66 distributions (33 musical features × 2 rating dimensions).

The correlation coefficients were transformed by using the Fisher-z-transformation procedure, and the distribution of these transformed coefficients was fitted with a normal distribution resulting in two fit parameters (M mean, SD). First, to test whether the distribution of correlation coefficients was significantly different from a normal distribution with M = 0, we performed a permutation test to acquire a null distribution with an estimated M and SD. For the permutation, we shuffled the acoustic feature (n = 33) to music period (n = 12) relationship 500 times for each condition and each participant, resulting in 42,768 permutations for the entire sample. Each fitted distribution of the empirical data (empirical M and SD) was compared with the normal distribution resulting from the permutation sampling (permutation M and SD) by using two-sided Kolmogorov–Smirnov tests; significance was tested for each of the 33 musical features in each condition by using an FDR-corrected level of P < 0.01. Next, the same procedure as described above was also applied to the relationships between the time courses of the perceptual ratings and the brain data in all 19 ROIs, resulting in 38 correlation coefficient distributions (2 rating dimensions × 19 ROIs). Finally, to compare distributions between conditions directly, we used a Wilcoxon rank sum test (P < 0.01, FDR corrected).

Supplementary Material

Appendix 01 (PDF)

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the Swiss NSF (SNSF 100014_182135/1 to S.F.). We thank Philipp Stämpfli for technical assistance with the neurofeedback setup.

Author contributions

N.F. and S.F. designed research; W.T., C.T., N.F., F.S., and S.F. performed research; W.T., C.T., N.F., F.S., and S.F. analyzed data; and W.T., C.T., N.F., and S.F. wrote the paper.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interest.

Footnotes

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

Contributor Information

Wiebke Trost, Email: wjstrost@gmail.com.

Sascha Frühholz, Email: s.fruehholz@gmail.com.

Data, Materials, and Software Availability

Data are available upon reasonable request. The conditions of ethics approval and consent procedures do not permit public archiving of anonymized study data. Music examples can be found here: https://caneuro.github.io/blog/2023/study-live-music/ (70). Group T-maps of the fMRI data are available on NeuroVault (identifiers.org/neurovault.collection:13989) (71). No custom-made code was used for the analyses in this study.

Supporting Information

References

- 1.Frühholz S., Trost W., Kotz S. A., The sound of emotions-Towards a unifying neural network perspective of affective sound processing. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 68, 1–15 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Juslin P. N., Laukka P., Communication of emotions in vocal expression and music performance: Different channels, same code? Psychol. Bull. 129, 770–814 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Koelsch S., Fritz T., Cramon D. Y. V., Müller K., Friederici A. D., Investigating emotion with music: An fMRI study. Hum. Brain Mapp. 27, 239–250 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Salimpoor V. N., et al. , Interactions between the nucleus accumbens and auditory cortices predict music reward value. Science 1979, 216–219 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Trost W., Ethofer T., Zentner M., Vuilleumier P., Mapping aesthetic musical emotions in the brain. Cereb. Cortex 22, 2769–2783 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Frühholz S., Trost W., Grandjean D., The role of the medial temporal limbic system in processing emotions in voice and music. Prog. Neurobiol. 123, 1–17 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Trevor C., Renner M., Frühholz S., Acoustic and structural differences between musically portrayed subtypes of fear. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 153, 384–399 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sachs M. E., Damasio A., Habibi A., The pleasures of sad music: A systematic review. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 9, 404 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Koelsch S., et al. , The roles of superficial amygdala and auditory cortex in music-evoked fear and joy. Neuroimage 81, 49–60 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Blood A. J., Zatorre R. J., Intensely pleasurable responses to music correlate with activity in brain regions implicated in reward and emotion. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 98, 11818–11823 (2001). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Salimpoor V. N., Benovoy M., Larcher K., Dagher A., Zatorre R. J., Anatomically distinct dopamine release during anticipation and experience of peak emotion to music. Nat. Neurosci. 14, 257–264 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Trost W., Frühholz S., Cochrane T., Cojan Y., Vuilleumier P., Temporal dynamics of musical emotions examined through intersubject synchrony of brain activity. Soc. Cogn. Affect. Neurosci. 10, 1705–1721 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Koelsch S., Brain correlates of music-evoked emotions. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 15, 170–180 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pessoa L., A network model of the emotional brain. Trends Cogn. Sci. 21, 357–371 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Juslin P. N., Sakka L. S., “Neural correlates of music and emotion” in The Oxford Handbook of Music and the Brain, Thaut M. H., Hodges D. A., Eds. (Oxford University Press, 2019), pp. 285–332. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vuust P., Heggli O. A., Friston K. J., Kringelbach M. L., Music in the brain. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 23, 287–305 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Koelsch S., Skouras S., Lohmann G., The auditory cortex hosts network nodes influential for emotion processing: An fMRI study on music-evoked fear and joy. PLoS One 13, e0190057 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Koelsch S., Cheung V. K. M., Jentschke S., Haynes J.-D., Neocortical substrates of feelings evoked with music in the ACC, insula, and somatosensory cortex. Sci. Rep. 11, 10119 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Trost W., et al. , Getting the beat: Entrainment of brain activity by musical rhythm and pleasantness. Neuroimage 103, 55–64 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gordon C. L., Cobb P. R., Balasubramaniam R., Recruitment of the motor system during music listening: An ALE meta-analysis of fMRI data. PLoS One 13, e0207213 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Putkinen V., et al. , Decoding music-evoked emotions in the auditory and motor cortex. Cereb. Cortex 31, 2549–2560 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Trost W., Frühholz S., The hippocampus is an integral part of the temporal limbic system during emotional processing. Comment on “The quartet theory of human emotions: An integrative and neurofunctional model” by S. Koelsch et al. Phys. Life Rev. 13, 87–88 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cheung V. K. M., et al. , Uncertainty and surprise jointly predict musical pleasure and amygdala, hippocampus, and auditory cortex activity. Curr. Biol. 29, 4084–4092.e4 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Koelsch S., Investigating the neural encoding of emotion with music. Neuron 98, 1075–1079 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Steiner F., et al. , Affective speech modulates a cortico-limbic network in real time. Prog. Neurobiol. 214, 102278 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Phelps E. A., LeDoux J. E., Contributions of the amygdala to emotion processing: From animal models to human behavior. Neuron 48, 175–187 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mueller K., et al. , Investigating brain response to music: A comparison of different fMRI acquisition schemes. Neuroimage 54, 337–343 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Koelsch S., A coordinate-based meta-analysis of music-evoked emotions. Neuroimage 223, 117350 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Singer N., et al. , Common modulation of limbic network activation underlies musical emotions as they unfold. Neuroimage 141, 517–529 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lehne M., Rohrmeier M., Koelsch S., Tension-related activity in the orbitofrontal cortex and amygdala: An fMRI study with music. Soc. Cogn. Affect. Neurosci. 9, 1515–1523 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Warrenburg L. A., Choosing the right tune. Music Percept. 37, 240–258 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 32.Swarbrick D., et al. , How live music moves us: Head movement differences in audiences to live versus recorded music. Front. Psychol. 9, 2682 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Czepiel A., et al. , Synchrony in the periphery: Inter-subject correlation of physiological responses during live music concerts. Sci. Rep. 11, 22457 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chabin T., et al. , Interbrain emotional connection during music performances is driven by physical proximity and individual traits. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1508, 178–195 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shoda H., Adachi M., Umeda T., How live performance moves the human heart. PLoS One 11, e0154322 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fancourt D., Williamon A., Attending a concert reduces glucocorticoids, progesterone and the cortisol/DHEA ratio. Publ. Health 132, 101–104 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hou Y., Song B., Hu Y., Pan Y., Hu Y., The averaged inter-brain coherence between the audience and a violinist predicts the popularity of violin performance. Neuroimage 211, 116655 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chapin H., Jantzen K., Kelso J. A. S., Steinberg F., Large E., Dynamic emotional and neural responses to music depend on performance expression and listener experience. PLoS One 5, e13812 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Engel A., Keller P. E., The perception of musical spontaneity in improvised and imitated jazz performances. Front. Psychol. 2, 1–13 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ramirez R., Palencia-Lefler M., Giraldo S., Vamvakousis Z., Musical neurofeedback for treating depression in elderly people. Front. Neurosci. 9, 354 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ehrlich S., Guan C., Cheng G., “A closed-loop brain-computer music interface for continuous affective interaction” in 2017 International Conference on Orange Technologies (ICOT) (IEEE, Singapore, 2017), pp. 176–179. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Takabatake K., et al. , Musical auditory alpha wave neurofeedback: Validation and cognitive perspectives. Appl. Psychophysiol. Biofeedback 46, 323–334 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fuller C. D., Galvin J. J., Maat B., Free R. H., BaÅŸkent D., The musician effect: Does it persist under degraded pitch conditions of cochlear implant simulations? Front. Neurosci. 8, 179 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Miendlarzewska E. A., Trost W. J., How musical training affects cognitive development: Rhythm, reward and other modulating variables. Front. Neurosci. 7, 279 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lartillot O., Toiviainen P., Eerola T., “A matlab toolbox for music information retrieval” in Data Analysis, Machine Learning and Applications, C. Preisach, H. Burkhardt, L. Schmidt-Thieme, R. Decker, Eds. (Springer, 2007), pp. 261–268. [Google Scholar]