Abstract

Objective

Latent class analysis was used to identify functional classes among patients hospitalized for pneumonia. Then, we determined predictors of class membership and examined variation in distal outcomes among the functional classes.

Design

An observational, cross-sectional study design was used with retrospectively collected data between 2014 and 2018.

Setting

The study setting was a single health system including 5 acute care hospitals.

Participants

A total of 969 individuals hospitalized with the primary diagnosis of pneumonia and receipt of an occupational and/or physical therapy evaluation were included in the study.

Interventions

Not applicable.

Main Outcomes

The following 5 distal outcomes were examined: (1) occupational therapy treatment use, (2) physical therapy treatment use, (3) discharge to home with no services, (4) discharge to home with home health, and (5) institutional discharge.

Results

Five functional classes were identified and labeled as follows: Globally impaired, Independent with low-level self-care, Independent low-level mobility, Independent self-care, and Independent. Probability of occupational therapy treatment use (χ2[4]=50.26, P<.001) and physical therapy treatment use (χ2[4]=50.86, P<.001) varied significantly across classes. The Independent with low-level self-care class had the greatest probability of occupational therapy treatment use and physical therapy treatment use. Probability of discharging to home without services (yes/no; χ2[4]=88.861, P<.001), home with home health (yes/no; χ2[4]=15.895, P=.003), and an institution (yes/no; χ2[4]=102.013, P<.001) varied significantly across the 5 classes. The Independent class had the greatest probability of discharging to home without services.

Conclusions

Five functional classes were identified among individuals hospitalized for pneumonia. Functional classes could be used by the multidisciplinary team in the hospital as a framework to organize the heterogeneity of functional deficits after pneumonia, improve efficiency of care processes, and help deliver targeted rehabilitation treatment.

KEYWORDS: Acute care, Daily activities, Function, Mobility, Pneumonia, Rehabilitation, Self-care

Every year, 1 million Americans are hospitalized for pneumonia.1 Pneumonia has been among the most common reasons for hospitalization in the United States for more than 20 years.2 During hospitalization, patients with pneumonia frequently experience a decline in their ability to perform self-care and mobility tasks.3,4 Functional decline for patients with pneumonia is associated with poor health outcomes such as prolonged hospital stays, greater rates of hospital readmission, and greater rates of mortality.5, 6, 7, 8, 9 Early identification of functional decline in individuals with pneumonia is difficult due to the heterogeneity of symptoms and different etiologies.10, 11, 12, 13, 14 Functional assessments with summed scores are commonly used in clinical practice to evaluate functional impairment; however, summed scores from functional assessments can mask persistent functional impairments due to lack of sensitivity.15, 16, 17 For example, the National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale is a well-validated and commonly used functional assessment. However, individuals after stroke categorized as having a mild stroke according to the National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale experience persistent disability.18 Although summed scores from functional assessments are valuable for expediated clinical decision-making, they may impede targeted interventions and patient experiences. Identifying classes of patients with pneumonia based on specific patterns of activity limitations with mobility and self-care then examining how predictors and outcomes vary among the classes may help to augment the use of functional assessments by improving efficient use of targeted interventions, thus mitigating functional decline in the hospital.

In this study, we used latent class analysis (LCA) to identify distinct classes among patients hospitalized for pneumonia. LCA is a statistical procedure that identifies subgroups from populations who appear to have similar characteristics (eg, individuals with pneumonia). We characterized classes using patients’ activity limitations with mobility and self-care tasks according to the Activity Measure for Post-Acute Care (AM-PAC). The AM-PAC is a commonly used tool in the hospital19 and well-positioned to produce descriptive functional classes. We also identified predictors of membership for the classes and examined variation in the following distal outcomes across the classes: (1) physical therapy (PT) treatment use, (2) occupational therapy (OT) treatment use, and (3) discharge location.

Methods

Data source, study setting, and cohort selection

We performed an observational, cross-sectional study using patient-level retrospective, deidentified, electronic medical records (EMRs) from patients admitted to 1 of 5 acute care hospitals within a single health system between 2014 and 2018. Only patients with the primary diagnosis of pneumonia were included in the study. Primary diagnosis was determined using International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision and Ninth Revision codes (supplemental table 1, available online only at http://www.archives-pmr.org/). Inclusion criteria were (1) aged ≥18 years, (2) evaluation for OT and/or PT, and (3) complete data for the study variables. Exclusion criteria were (1) death during hospitalization or (2) discharged or transferred to another acute care hospital. Using the inclusion and exclusion criteria, we collected and deidentified data by using Health Data Compass,20 an enterprise health data warehouse within the study site's health system. Quality checks were completed by Health Data Compass analysts and the authors to ensure data accuracy, then the deidentified data were delivered to the authors. A total of 969 patients met the inclusion criteria. The study site's institutional review board approved a Not Human Subjects research determination; thus, no patient consent was required.

Measures

Indicators for latent classes

The AM-PAC was used to characterize the classes, specifically the “6-Clicks” Basic Mobility and Daily Activity short forms. Physical therapists completed the Basic Mobility forms, whereas occupational therapists completed the Daily Activity forms. Basic Mobility and Daily Activity forms have a rating range of 1 (total assistance) to 4 (no assistance). Greater scores indicate greater levels of independence. Mobility tasks included in the Basic Mobility form are (1) turning over in bed; (2) sitting down on/standing up from a chair with arms; (3) moving from lying on back to sitting on the side of the bed; (4) moving to and from a bed to a chair; (5) walking in the hospital room; and (6) climbing 3 to 5 steps with a railing. The Daily Activity form includes the following self-care tasks: (1) upper body dressing; (2) lower body dressing; (3) bathing; (4) toileting; (5) grooming; and, (6) eating.19 All 12 AM-PAC items collected at the time of OT or PT evaluation were used to identity unique classes for patients with pneumonia. Consistent with previous studies,21 we dichotomized all 12 AM-PAC into the following categorial indicators: assistance required (score ≤3) vs no assistance (score=4).

Covariates

We included the following covariates: age, comorbidity burden, length of stay, sex, significant other, minority status, and insurance type. Age, comorbidity burden, and length of stay were included as continuous variables. To determine comorbidity burden, we calculated the Elixhauser Comorbidity Index according to Moore et al.22 Sex was dichotomized into female or male. Significant other and racial/ethnic minority status also were dichotomized into yes or no. Racial/ethnic minority status included individuals who identified as American Indian or Alaskan Native, Asian, Black or African American, Multiple Race, Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander, Hispanic/Latinx, or Other. Insurance type was categorized into (1) private, (2) Medicare, (3) Medicaid, and (4) other (eg, workers’ compensation). Age, sex, race/ethnicity, comorbidities, and insurance type are associated with the study outcomes for individuals hospitalized with respiratory illness23,24 and were thus controlled for in our study.

Distal outcomes

We performed follow-up analyses25 to examine differences between patient classes based on the following 5 distal outcomes: (1) OT treatment use, (2) PT treatment use, (3) discharge to home with no services, (4) discharge to home with home health, and (5) discharge to an institution. Discharge to home with no services, discharge to home with home health, and discharge to an institution are collectively referred to as discharge location. Receipt of OT and/or PT treatment was defined by the first documentation of OT or PT treatment billing codes (yes/no) that immediately followed an OT or PT evaluation (ie, first OT/PT treatment session).

Data analysis

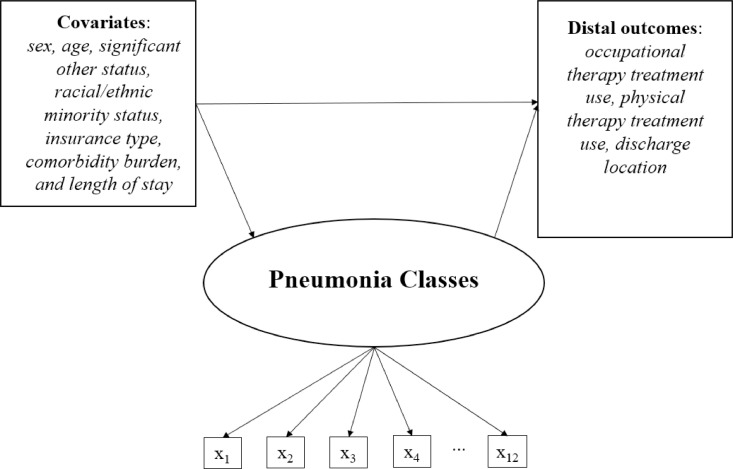

Three analyses were performed using Mplus26: (1) latent class enumeration, (2) multinomial regression to examine predictors of the functional subgroups, and (3) manual Bolck-Croon-Hagenaars (BCH) approach to examine variability in the distal outcomes among the classes (fig 1).

Fig 1.

Latent class model with predictors of class membership and distal outcomes. NOTE. x1-x12 signify the AM-PAC items used to identify the functional subgroups, which are: (1) turning over in bed; (2) sitting down on/standing up from a chair with arms; (3) moving from lying on back to sitting on the side of the bed; (4) moving to and from a bed to a chair; and (5) walking in the hospital room; and (6) climbing 3-5 steps with a railing; (7) upper body dressing; (8) lower body dressing; (9) bathing; (10) toileting; (11) grooming; and (12) eating.

LCA (class enumeration)

LCA is a statistical method used to identify latent class membership for a group of patients using observed indicator variables.27 More specifically, we used LCA with robust maximum likelihood estimation to identify classes based on patients’ probability of requiring assistance with each of the 12 AM-PAC items (ie, observed indicator variables) (fig 1). Models were fit with 1 to 8 classes. Five model fit statistics were evaluated to identify candidate models: (1) Akaike information criterion (AIC), (2) Bayesian information criterion (BIC), (3) Adjusted Bayesian information criterion (ABIC), (4) Lo-Mendell-Rubin likelihood ratio test, and lastly, the (5) bootstrap likelihood ratio test.28,29 Lower numbers for the AIC, BIC, and ABIC indicate improved model fit. A significant P value for the Lo-Mendell-Rubin likelihood ratio test and bootstrap likelihood ratio tests indicate improved model fit compared with the model with k–1 classes. Candidate models were further assessed by examining relative entropy, mean posterior class probability across classes, and clinical interpretability.28,29 For clinical interpretability, 3 authors with clinical experience working with patients hospitalized for pneumonia as occupational therapists (J.E., A.K., and A.H.) achieved consensus on the optimal model. Upon selecting the optimal model, patients’ membership to a specific class were then determined based on posterior probability. After patients were assigned to classes, descriptive statistics were calculated by class.

Follow-up analyses

Follow-up analyses were performed examining the predictors of membership for the classes and variation in distal outcomes (OT treatment use, PT treatment use, and discharge location) across the classes. We estimated a multinomial regression model and used the covariates as predictors of class membership. Odds ratios were generated from multinomial regression analyses, which compared the odds of a patient's membership to one class vs the odds of membership to the Independent class (Table 1) based on the specified covariate. To examine variation in distal outcomes across the functional subgroups, we used the manual BCH approach. The manual BCH approach accounts for measurement error in latent class membership, thereby enabling more accurate parameter estimates and standard errors.30, 31, 32

Table 1.

Multinomial regression results explaining class membership (n=969)

| Variable | Class (Reference Class = Independent [Class 5]) |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Globally Impaired (Class 1) |

Independent Low-Level Self-Care (Class 2) |

Independent Low-Level Mobility (Class 3) |

Independent Self-Care (Class 4) |

|||||

| OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | |

| Woman (ref = man) | 0.66 | 0.43-1.02 | 0.69 | 0.44-1.07 | 0.77 | 0.47-1.26 | 0.88 | 0.51-1.52 |

| Age | 1.02 | 1.00, 1.04* | 1.01 | 0.99-1.02 | 1.02 | 1.00-1.04* | 1.00 | 0.98-1.03 |

| Significant other (ref = no) | 0.54 | 0.35-0.83† | 0.79 | 0.50-1.23 | 0.76 | 0.46-1.25 | 0.87 | 0.50-1.49 |

| Minority (ref = no) | 1.16 | 0.66-2.02 | 0.95 | 0.52-1.72 | 1.42 | 0.77-2.63 | 1.43 | 0.74-2.77 |

| Insurance type (ref = Private) | ||||||||

| Medicare | 2.29 | 0.99-5.28 | 1.39 | 0.65-2.95 | 5.21 | 1.43-18.94* | 1.80 | 0.67-4.87 |

| Medicaid | 2.62 | 0.97-7.11 | 1.30 | 0.52-3.25 | 8.14 | 2.02-32.83† | 1.93 | 0.61-6.05 |

| Other | 0.41 | 0.07-2.53 | 0.41 | 0.08-1.97 | 1.99 | 0.30-13.36 | 2.54 | 0.65-9.96 |

| Comorbidity burden | 1.01 | 0.99-1.03 | 1.01 | 0.99-1.03 | 0.99 | 0.97-1.02 | 1.00 | 0.98-1.03 |

Abbreviations: 95% CI, 95% confidence interval for the odds ratio; OR, odds ratio.

P≤.05.

P≤.01.

Results

Class enumeration

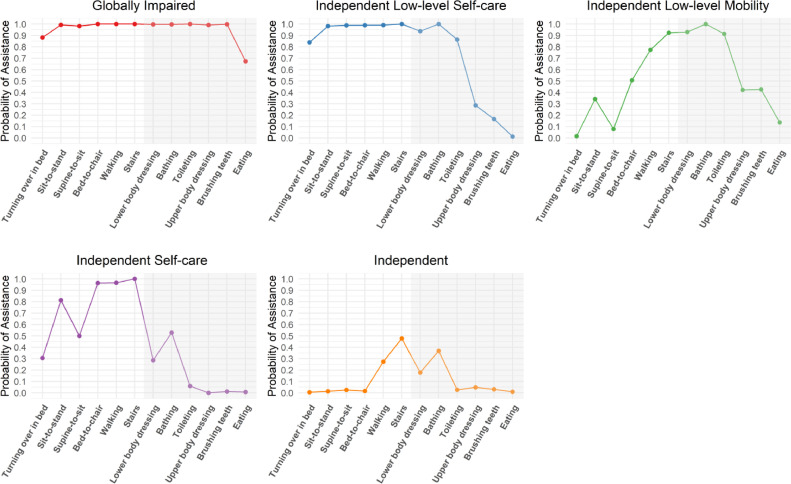

Class enumeration uses model fit statistics, conditional item probability, class separation, and clinical interpretability to identify latent classes for a population. Trends of lowering AIC, BIC, and ABIC began to diminish after adding a sixth class, leading us to consider models with 5 to 7 classes as candidate solutions. Conditional item probabilities were closely examined by the study team, including by authors with clinical experience (J.E., A.K., and A.H.). The study team reached a consensus and selected the 5-class solution because classes were qualitatively distinct and clinically interpretable. Further, the 5-class solution had superior class separation (ie, high [.70] or low [.30] conditional item probabilities across classes) compared with the 6-class and 7-class solutions, making the classes more qualitatively distinct.29

Description and predictors of membership for classes

The 5 classes were labeled as follows: (1) Globally impaired (Class 1), (2) Independent with low-level self-care (Class 2), (3) Independent low-level mobility (Class 3), (4) Independent self-care (Class 4), and (5) Independent (Class 5). The largest class was Class 1 (28.6%) (Table 2) followed by Class 2 (21.8%) and Class 3 (19.1%). Patients in the Class 1 (n=277; 28.6%) were characterized by having a high probability of needing assistance with all mobility (turning over in bed, sit to stand, supine to sit, bed to chair, walking, and stairs) and most self-care tasks (lower body dressing, bathing, toileting, upper body dressing, brushing teeth) (fig 2). Significant predictors of membership for Class 1 were older age and no significant other compared with Class 5 (Table 1). Class 2 (n=211; 21.8%) included patients who had a low probability of needing assistance with upper-body dressing, brushing teeth, and eating but high probability of requiring assistance for all the remaining mobility and self-care tasks. None of the covariates were significant predictors of membership for Class 2. Class 3 (n=185; 19.1%) included patients who had a low probability of needing assistance with turning over in bed and supine to sit but a high probability of needing assistance with mobility and self-care tasks requiring good dynamic balance. Patients who were older and had Medicare or Medicaid for their insurance compared with private insurance were most likely to be in Class 3 class compared with Class 5. Class 4 (n=120: 12.4%) was the smallest class and differed from Class 2 by including patients who had a low probability of needing assistance with most of the self-care tasks but a high probability of requiring assistance with most mobility tasks. None of the covariates were significant predictors of class membership for Class 4. Lastly, Class 5 (n=176; 18.2%) included patients who had a low probability of requiring assistance with most of the mobility or self-care tasks.

Table 2.

Descriptive analysis (N=969)

| Class |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Total Sample (N=970) | Globally Impaired (Class 1) | Independent Low-Level Self-Care Tasks (Class 2) | Independent With Low-Level Mobility Tasks (Class 3) | Independent With Self-Care (Class 4) | Independent (Class 5) |

| Covariates | ||||||

| Legal sex; n (%) | ||||||

| Men | 450 (46.4) | 130 (46.9) | 104 (49.3) | 85 (45.9) | 55 (45.8) | 76 (43.2) |

| Women | 519 (53.6) | 147 (53.1) | 107 (50.7) | 100 (54.1) | 65 (54.2) | 100 (56.8) |

| Age, y; mean (SD) | 74.9 (14.4) | 77.1 (14.5) | 73.9 (14.8) | 76.7 (13.8) | 72.9 (13.7) | 71.9 (14.1) |

| Significant other status; n (%) | ||||||

| No | 543 (56.0) | 177 (63.9) | 112 (53.1) | 107 (57.8) | 63 (52.5) | 84 (47.7) |

| Yes | 426 (44.0) | 100 (36.1) | 99 (46.9) | 78 (42.2) | 57 (47.5) | 92 (52.3) |

| Racial/ethnic minority status; n (%) | ||||||

| No | 798 (82.4) | 230 (83.0) | 179 (84.8) | 148 (80.0) | 94 (78.3) | 147 (83.5) |

| Yes | 171 (17.6) | 47 (17.0) | 32 (15.2) | 37 (20.0) | 26 (21.7) | 29 (16.5) |

| Insurance type; n (%) | ||||||

| Medicare | 767 (79.2) | 235 (84.8) | 165 (78.2) | 154 (83.2) | 89 (74.2) | 124 (70.5) |

| Medicaid | 103 (10.6) | 27 (9.7) | 21 (10.0) | 23 (12.4) | 14 (11.7) | 18 (10.2) |

| Private insurance | 22 (2.3) | 2 (0.7) | 3 (1.4) | 3 (1.6) | 7 (5.8) | 7 (4.0) |

| Other | 77 (7.9) | 13 (4.7) | 22 (10.4) | 5 (2.7) | 10 (8.3) | 27 (15.3) |

| Comorbidity burden; median (IQR) | 6 (0.0-11.0) | 5 (5.0-13.5) | 7 (0.0-11.0) | 0 (0.0-9.0) | 7 (0.0-12.0) | 6 (0.0-10.5) |

| Length of stay; median (IQR) | 3 (3.0-6.5) | 4 (2.0-5.0) | 3 (2.0-5.0) | 3 (2.0-5.0) | 3 (2.0-4.0) | 3 (2.0-4.0) |

| Distal outcomes | ||||||

| Discharge location; n (%) | ||||||

| Home without services | 517 (53.4) | 76 (27.4) | 104 (49.3) | 110 (59.5) | 79 (65.8) | 148 (84.1) |

| Home health care | 180 (18.6) | 46 (16.6) | 44 (20.9) | 43 (23.2) | 30 (25.0) | 17 (9.7) |

| Institution | 272 (28.1) | 155 (56.0) | 63 (29.9) | 32 (17.3) | 11 (9.2) | 11 (6.3) |

| Occupational therapy treatment use; n (%) | ||||||

| No | 629 (64.9) | 159 (57.4) | 114 (54.0) | 105 (56.8) | 99 (82.5) | 152 (86.2) |

| Yes | 340 (35.1) | 118 (42.6) | 97 (46.0) | 80 (43.2) | 21 (17.5) | 24 (13.6) |

| Physical therapy treatment use; n (%) | ||||||

| No | 580 (59.9) | 148 (53.4) | 98 (46.4) | 115 (62.2) | 69 (57.5) | 150 (85.2) |

| Yes | 389 (40.1) | 129 (46.6) | 113 (53.6) | 70 (37.8) | 51 (42.5) | 26 (14.8) |

NOTE. Class assignment is based on posterior membership probabilities and does not account for measurement error in latent class membership.

Abbreviation: IQR, interquartile range.

Fig 2.

Profile plot illustrating conditional item probabilities for each of the 5 latent classes. No shading indicates mobility tasks. Shading indicated self-care tasks.

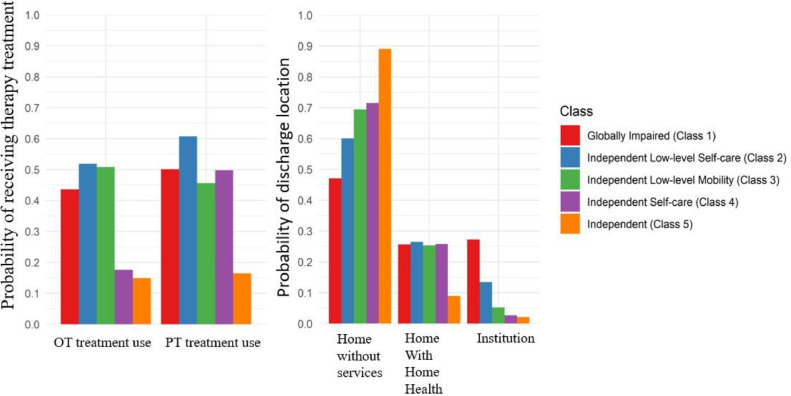

We examined variation in distal outcomes across the 5 latent classes. The Wald chi-square test indicated that the probability of OT treatment use (χ2[4]=50.26, P<.001) and PT treatment use (χ2[4]=50.86, P<.001) varied significantly across classes. Patients in Class 2 had the greatest probability of OT treatment use (.52) and PT treatment use (.61) (fig 3). Conversely, patients in Class 5 had the lowest probability of OT treatment use (.15) and PT treatment use (.16).

Fig 3.

Estimated probability of receiving OT and PT treatment use and discharge location across the 5 latent classes. Estimates adjusted for sex, age, significant other status, minority status, insurance type, comorbidity burden, and length of stay.

We found significant variation across the discharge locations. Omnibus results indicated that overall probability of discharging to home without services (yes/no; χ2[4]=88.861, P<.001), home with home health (yes/no; χ2[4]=15.895, P=.003), and an institution (yes/no; χ2[4]=102.013, P<.001) varied significantly across the 5 classes. Patients in Class 5 had the greatest probability of discharging to home without services (.89), whereas Class 1 had the lowest probability of discharging to home without services (.47). Class 2 had the greatest probability of discharging home with home health (.26). Class 1 had the greatest probability of discharging to an institution (.27), followed by Class 2 (13%).

Discussion

We identified 5 classes of patients hospitalized with pneumonia, derived from varying patterns of activity limitations with mobility and self-care tasks. We also identified predictors of class membership (eg, age; insurance type; significant other status), shedding light on risk factors for functional impairment for patients hospitalized with pneumonia specific to the functional classes. Variation was found across all 5 classes in the distal outcomes (OT treatment use, PT treatment use, and discharge location). Our findings offer a nuanced depiction of the heterogeneity of functional impairment in this population, which can inform efforts aimed at improving functional status while hospitalized, efficiently and equitably allocating therapy resources, augmenting therapy documentation by providing early guidance for targeted treatments and optimizing discharge planning.

The largest class among patients hospitalized for pneumonia was the Globally impaired class (Class 1; n=277; 28.6%). Class 1 included patients who had a high probability of needing assistance with all mobility and self-care tasks, except for eating. Patients hospitalized for pneumonia commonly experience functional decline during their hospital stay.5,7,33,34 Functional decline is a strong predictor of need for follow-up rehabilitation services after hospital discharge.35, 36, 37 Individuals with greater functional decline would be anticipated to have greater need for follow-up rehabilitation services after hospitalization. However, our findings show that many patients in Class 1 were discharged home with no services, suggesting potential gaps in access to care. Future studies should consider including change in functional status to determine whether unmet needs or quick functional recovery during hospitalization is responsible for the high probability of patients in Class 1 discharging home with no services. Future studies could also include health systems in which the AM-PAC is administered to all patients regardless of consultation to OT and PT services. Evaluating the functional recovery of patients who did not have an OT or PT consultation could help researchers understand differences between unmet needs and spontaneous functional recovery. Including health systems in future research where the AM-PAC is administered systemically would help to identify any groups of patients who are underrepresented in the findings and improve generalizability.

Patients in 4 of 5 classes, Class 1, Independent low-level self-care (Class 2), Independent low-level mobility (Class 3), and Independent self-care (Class 4), had similarly low, but almost equal, probabilities of discharging to home with home health (.25 to .26). The equal probabilities across several functional classes show a wide variety of functional limitations that are addressed by home health services. For example, patients who required assistance with mobility tasks but not self-care tasks (Class 4) vs patients who required assistance with self-care tasks but not mobility tasks (Class 3) had the same probability of discharging to home with home health. Our results suggest that discharge to home with home health may be appropriate for a wide range of patients with varying functional limitations, but is underused. Patients prefer to discharge home after hospitalization.38, 39, 40 As alternative payment models become more prevalent in the United Stated health care system, discharging home from the hospital vs a costly institution stay is becoming more incentivized for hospital systems.41,42 Future studies should consider examining patients’ long-term outcomes in terms of function, quality of life, and reintegration into the community after discharging to home with home health vs other discharge locations to better understand the unique benefits of home health. In addition, eligibility for home health services based on functional limitations should be examined. Class 1 had almost equal probability of discharging to home but considerably more functional limitations than the other classes. Future studies may consider evaluating the cost-effectiveness of home health for patients with significant functional limitations and compare long-term outcomes with other discharge locations.

Several previous studies examining functional limitations for patients with pneumonia have used the Modified Barthel Index33,43, 44, 45 Although the Modified Barthel Index is a reliable and valid functional assessment tool46,47 used to measure dependence with activities of daily living for a variety of diagnoses, clinical interpretability of the results from the tool are limited to only numeric changes in total scores.48 In terms of classes composed of individuals with pneumonia, Wittermans et al49 created classes for patients with pneumonia, but classes were characterized by biomarkers data (eg, plasma concentration of interleukin-1 receptor antagonist) and used to evaluate response to corticosteroids; no functional data were included. Our study provides a clinically interpretable framework to examine differences in patient outcomes based on functional limitations and not limited to numeric changes in total scores. In addition, our findings are novel because no other studies have examined predictors of membership to the classes. Predictors of class membership varied, but common predictors were older age, insurance type, and whether the patient had a significant other. Creating classes based on functional limitations and identifying predictors of membership may help to identify patients early who need follow-up rehabilitation services while hospitalized and are at risk for a noncommunity discharge.

Study limitations

Limitations should be noted for our study. First, the generalizability of our study is limited because we analyzed data from a single health care system. However, the single health care system included both urban and rural hospitals, creating a more representative sample. Second, we used EMR data, which are real-world data and not entered for research purposes, resulting in unknown interrater reliability. Despite the limitations with real-world data, this type of data has several notable strengths. For example, real-world data allow for larger sample sizes, less expensive and faster completion of studies, can assess care delivery patterns across a broader range of outcomes, and produce real-world outcomes.50 Third, the discharge locations were recommended dispositions after hospitalized and not actual disposition. This is a common limitation for studies that use EMR data. Actual disposition for patients after hospitalization can only be confirmed using all-payer claims data at the state-level. Future studies should consider including all-payer claims data to verify patients’ actual disposition. Fourth, AM-PAC scores that were used to characterize the latent classes were collected during the first OT and PT visit regardless of location in the hospital (ie, intensive care unit, floor). As a result, the functional status of a patient may have changed by the time of discharge from the hospital. However, early prediction of discharge location has shown promise during the discharge planning process in the hospital.51 Further, collecting the first OT and PT visit helped us to determine the need for OT treatment use and PT treatment use and receipt of only 1 to 3 visits from OT and PT services in the hospital is typical for patients with pneumonia.9 Future studies should consider including change in functional status to characterize functional classes. In addition, future studies could examine variation in service frequency as a distal outcome between functional classes. Lastly, local independence is an inherent limitation of LCA. Local independence states that indicator variables should be independent, uncorrelated items. Confirming local independence is exceedingly difficult because LCA studies with large sample sizes that run statistical tests of association will be systematically significant regardless of effect size. Notably, evidence exists that supports local independence for the AM-PAC items.52 Despite this evidence and identifying a priori model fit criteria, the risk of local independence not being met is still a possible limitation of the study.

Conclusions

We identified 5 distinct classes based on activity limitations with mobility and self-care tasks among patients hospitalized for pneumonia. Predictors of class membership varied among the classes, with older age, insurance type, and whether the patient had a significant other being common predictors. Patients hospitalized with pneumonia are at high risk for functional decline during hospitalization.5,7 Hospital-based OT and PT services are directly focused on reducing functional decline during hospitalization53; however, guidelines for hospital-based OT and PT services are minimal. Our findings may help hospital-based rehabilitation departments identify early patients who may need hospital-based, follow-up OT and PT services and may be at high risk for noncommunity discharge, thus helping to more efficiently allocate services. Further, discharge planning in the hospital is a complex process requiring coordination from the entire multidisciplinary team. Our results allow providers to identify patients who have a high probability of needing home health services or an institutional discharge. Future studies should consider examining long-term outcomes across the 5 classes including 30-day readmission risk, quality of life, community reintegration, and function.

Footnotes

Disclosures: The authors have no conflicts to report.

Supported by the American Occupational Therapy Foundation (AOTFHSR19MALCOLM) (PI: Malcolm).

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.arrct.2024.100323.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

References

- 1.American Thoracic Society. Top pneumonia facts. Available at:https://www.thoracic.org/patients/patient-resources/resources/top-pneumonia-facts.pdf. Accessed July 12, 2022.

- 2.Salah HM, Minhas AMK, Khan MS, et al. Causes of hospitalization in the USA between 2005 and 2018. Eur Heart J Open. 2021;1:oeab001. doi: 10.1093/ehjopen/oeab001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kosai K, Izumikawa K, Imamura Y, et al. Importance of functional assessment in the management of community-acquired and healthcare-associated pneumonia. Intern Med. 2014;53:1613–1620. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.53.2499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Torres OH, Muñoz J, Ruiz D, et al. Outcome predictors of pneumonia in elderly patients: importance of functional assessment. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52:1603–1609. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52492.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kim SJ, Lee JH, Han B, et al. Effects of hospital-based physical therapy on hospital discharge outcomes among hospitalized older adults with community-acquired pneumonia and declining physical function. Aging Dis. 2015;6:174–179. doi: 10.14336/AD.2014.0801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jeon K, Yoo H, Jeong BH, et al. Functional status and mortality prediction in community-acquired pneumonia. Respirology. 2017;22:1400–1406. doi: 10.1111/resp.13072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tonkikh O, Shadmi E, Flaks-Manov N, Hoshen M, Balicer RD, Zisberg A. Functional status before and during acute hospitalization and readmission risk identification. J Hosp Med. 2016;11:636–641. doi: 10.1002/jhm.2595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Edelstein J, Middleton A, Walker R, Reistetter T, Reynolds S. Impact of acute self-care indicators and social factors on medicare inpatient readmission risk. Am J Occup Ther. 2022;76 doi: 10.5014/ajot.2022.049084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Freburger JK, Chou A, Euloth T, Matcho B. Variation in acute care rehabilitation and 30-day hospital readmission or mortality in adult patients with pneumonia. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3 doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.12979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chalmers JD. Corticosteroids for community-acquired pneumonia: a critical view of the evidence. Eur Respir J. 2016;48:984. doi: 10.1183/13993003.01329-2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Anand N, Kollef MH. The alphabet soup of pneumonia: CAP, HAP, HCAP, NHAP, and VAP. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2009;30:3–9. doi: 10.1055/s-0028-1119803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ewig S, Welte T, Chastre J, Torres A. Rethinking the concepts of community-acquired and health-care-associated pneumonia. Lancet Infect Dis. 2010;10:279–287. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(10)70032-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kaku N, Yanagihara K, Morinaga Y, et al. The definition of healthcare-associated pneumonia (HCAP) is insufficient for the medical environment in Japan: a comparison of HCAP and nursing and healthcare-associated pneumonia (NHCAP) J Infect Chemother. 2013;19:70–76. doi: 10.1007/s10156-012-0454-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Park CM, Dhawan R, Lie JJ, et al. Functional status recovery trajectories in hospitalised older adults with pneumonia. BMJ Open Respir Res. 2022;9 doi: 10.1136/bmjresp-2022-001233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fisher SR, Middleton A, Graham JE, Ottenbacher KJ. Same but different: FIM summary scores may mask variability in physical functioning profiles. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2018;99 doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2018.01.016. 1479-82.e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Abdul-Rahim AH, Fulton RL, Sucharew H, et al. National institutes of health stroke scale item profiles as predictor of patient outcome: external validation on independent trial data. Stroke. 2015;46:395–400. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.114.006837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sucharew H, Khoury J, Moomaw CJ, et al. Profiles of the National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale items as a predictor of patient outcome. Stroke. 2013;44:2182–2187. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.113.001255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Khatri P, Conaway MR, Johnston KC. Ninety-day outcome rates of a prospective cohort of consecutive patients with mild ischemic stroke. Stroke. 2012;43:560–562. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.593897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jette DU, Stilphen M, Ranganathan VK, Passek SD, Frost FS. AM-PAC "6-clicks" funtional assessment scores predict acute care hospital discharge destination. Phys Ther. 2014;94:1252–1261. doi: 10.2522/ptj.20130359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Health Data Compass. Health Data Compass. Available at: https://www.healthdatacompass.org/. Accessed Juluy 15th, 2022.

- 21.Edelstein J, Kinney AR, Keeney T, Hoffman A, Graham JE, Malcolm MP. Identification of disability subgroups for patients after ischemic stroke. Phys Ther. 2023;103:pzad001. doi: 10.1093/ptj/pzad001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moore L, Lavoie A, Camden S, et al. Statistical validation of the Glasgow Coma Score. J Trauma. 2006;60:1238–1243. doi: 10.1097/01.ta.0000195593.60245.80. discussion 1243-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Patel S, Truong GT, Rajan A, et al. Discharge disposition and clinical outcomes of patients hospitalized with COVID-19. Int J Infect Dis. 2023;130:1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2023.01.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kinney AR, Graham JE, Middleton A, Edelstein J, Wyrwa J, Malcolm MP. Mobility status and acute care physical therapy utilization: the Moderating roles of age, significant others, and insurance type. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2022;103:1600–1606.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2021.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Asparouhov T, Muthen B. Auxiliary variables in mixture modeling: using the BCH method in mplus to estimate a distal outcome model and an arbitrary secondary model. Available at:https://www.statmodel.com/download/asparouhov_muthen_2014.pdf. Accessed April 8, 2022.

- 26.Muthén L, Muthén B. 8th ed. Muthén & Muthén; Los Angeles, CA: 2017. Mplus user's guide. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sinha P, Calfee CS, Delucchi KL. Practitioner's guide to latent class analysis: methodological considerations and common pitfalls. Crit Care Med. 2021;49:e63–e79. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000004710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Muthén B. Statistical and substantive checking in growth mixture modeling: comment on Bauer and Curran (2003) Psychol Methods. 2003;8:369–377. doi: 10.1037/1082-989X.8.3.369. discussion 384-93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Masyn K. In: The Oxford handbook of quantitative methods in psychology. Little D, editor. Oxford Handbooks Online; Oxford: 2013. Latent class analysis and finite mixture modeling. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nylund-Gibson K, Grimm RP, Masyn KE. Prediction from latent classes: a demonstration of different approaches to include distal outcomes in mixture models. Structural Equation Modeling. 2019;26:967–985. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gudicha DW, Vermunt JK. In: Algorithms from and for nature and life: classification and data analysis. Lausen B, van den Poel D, Ultsch A, editors. Springer; Cham: 2013. Mixture model clustering with covariates using adjusted three-step approaches; pp. 87–94. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bakk Z, Tekle FB, Vermunt JK. Estimating the association between latent class membership and external variables using bias-adjusted three-step approaches. Sociol Methodol. 2013;43:272–311. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Andrew MK, MacDonald S, Godin J, et al. Persistent functional decline following hospitalization with influenza or acute respiratory illness. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2021;69:696–703. doi: 10.1111/jgs.16950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chen H, Hara Y, Horita N, Saigusa Y, Hirai Y, Kaneko T. Declined functional status prolonged hospital stay for community-acquired pneumonia in seniors. Clin Interv Aging. 2020;15:1513–1519. doi: 10.2147/CIA.S267349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jenq GY, Tinetti ME. Post-acute care: who belongs where? JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175:296–297. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.4298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Roberts P, Wertheimer J, Park E, Nuño M, Riggs R. Identification of functional limitations and discharge destination in patients with COVID-19. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2021;102:351–358. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2020.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Robinson TN, Wallace JI, Wu DS, et al. Accumulated frailty characteristics predict postoperative discharge institutionalization in the geriatric patient. J Am Coll Surg. 2011;213:37–42. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2011.01.056. discussion 42-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Robinson SM, B NB, B NM, Cotter PE, O'Connor M, Home O'Keeffe ST. please: a conjoint analysis of patient preferences after a bad hip fracture. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2015;15:1165–1170. doi: 10.1111/ggi.12415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Johnson JK, Hohman JA, Vakharia N, et al. High-intensity postacute care at home. NEJM Catalyst. 2021;2 [Google Scholar]

- 40.Augustine MR, Davenport C, Ornstein KA, et al. Implementation of post-acute rehabilitation at home: a skilled nursing facility-substitutive model. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2020;68:1584–1593. doi: 10.1111/jgs.16474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chandra A, Dalton MA, Holmes J. Large increases in spending on postacute care in Medicare point to the potential for cost savings in these settings. Health Aff (Millwood) 2013;32:864–872. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2012.1262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.McWilliams JM, Gilstrap LG, Stevenson DG, Chernew ME, Huskamp HA, Grabowski DC. Changes in postacute care in the Medicare shared savings program. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177:518–526. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.9115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Miyashita N, Nakamori Y, Ogata M, Fukuda N, Yamura A. Functional outcomes in elderly patients with hospitalized COVID-19 pneumonia: a 1 year follow-up study. Influenza Other Respir Viruses. 2022;16:1197–1198. doi: 10.1111/irv.13033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Murcia J, Llorens P, Sánchez-Payá J, et al. Functional status determined by Barthel Index predicts community acquired pneumonia mortality in general population. J Infect. 2010;61:458–464. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2010.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sanz F, Morales-Suárez-Varela M, Fernández E, et al. A composite of functional status and pneumonia severity index improves the prediction of pneumonia mortality in older patients. J Gen Intern Med. 2018;33:437–444. doi: 10.1007/s11606-017-4267-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dos Santos Barros V, Bassi-Dibai D, Guedes CLR, et al. Barthel Index is a valid and reliable tool to measure the functional independence of cancer patients in palliative care. BMC Palliat Care. 2022;21:124. doi: 10.1186/s12904-022-01017-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ohura T, Hase K, Nakajima Y, Nakayama T. Validity and reliability of a performance evaluation tool based on the modified Barthel Index for stroke patients. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2017;17:131. doi: 10.1186/s12874-017-0409-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lee SY, Kim DY, Sohn MK, et al. Determining the cut-off score for the Modified Barthel Index and the Modified Rankin Scale for assessment of functional independence and residual disability after stroke. PLoS One. 2020;15 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0226324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wittermans E, van der Zee PA, Qi H, et al. Community-acquired pneumonia subgroups and differential response to corticosteroids: a secondary analysis of controlled studies. ERJ Open Res. 2022;8:00489–02021. doi: 10.1183/23120541.00489-2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Camm AJ, Fox KAA. Strengths and weaknesses of ‘real-world’ studies involving non-vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulants. Open Heart. 2018;5 doi: 10.1136/openhrt-2018-000788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mickle CF, Deb D. Early prediction of patient discharge disposition in acute neurological care using machine learning. BMC Health Serv Res. 2022;22:1281. doi: 10.1186/s12913-022-08615-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Haley SM, Andres PL, Coster WJ, Kosinski M, Ni P, Jette AM. Short-form activity measure for post-acute care. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2004;85:649–660. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2003.08.098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Boltz M, Resnick B, Galik E. Preventing functional decline in the acute care setting. In: Boltz M, Capezuti E, Fulmer T, Zwicker D, editors. Evidence-based geriatric nursing protocols for best practice. New York: Springer Publishing Company. p. 195-210.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.