Highlights

Feasibility of a self-directed upper extremity training program to promote actual arm use for individuals living in the community with chronic stroke

-

•Distinct from clinic-based rehabilitation, self-directed rehabilitation approaches must address unique challenges related to decreased client motivation and adherence.

-

•Shared decision making and behavior change frameworks can support the implementation of UE self-directed rehabilitation.

-

•The Use My Arm-Remote program was feasible and safe to implement for individuals living in the community with chronic stroke.

-

•

Keywords: Self-directed training, Actual arm use, Shared decision-making, Stroke, Upper extremity

Abstract

Objective

To determine the feasibility of a self-directed training protocol to promote actual arm use in everyday life. The secondary aim was to explore the initial efficacy on upper extremity (UE) outcome measures.

Design

Feasibility study using multiple methods.

Setting

Home and outpatient research lab.

Participants

Fifteen adults (6 women, 9 men, mean age=53.08 years) with chronic stroke living in the community. There was wide range of UE functional levels, ranging from dependent stabilizer (limited function) to functional assist (high function).

Intervention

Use My Arm-Remote protocol. Phase 1 consisted of clinician training on motivational interviewing (MI). Phase 2 consisted of MI sessions with participants to determine participant generated goals, training activities, and training schedules. Phase 3 consisted of UE task-oriented training (60 minutes/day, 5 days/week, for 4 weeks). Participants received daily surveys through an app to monitor arm training behavior and weekly virtual check-ins with clinicians to problem-solve challenges and adjust treatment plans.

Outcome Measures

Primary outcome measures were feasibility domains after intervention, measured by quantitative study data and qualitative semi-structured interviews. Secondary outcomes included the Canadian Occupational Performance Measure (COPM), Motor Activity Log (MAL), Fugl-Meyer Assessment (FMA), and accelerometry-based duration of use metric measured at baseline, discharge, and 4-week follow-up.

Results

The UMA-R was feasible in the following domains: recruitment rate, retention rate, intervention acceptance, intervention delivery, adherence frequency, and safety. Adherence to duration of daily practice did not meet our criteria. Improvements in UE outcomes were achieved at discharge and maintained at follow-up as measured by COPM-Performance subscale (F[1.42, 19.83]=17.72, P<.001) and COPM-Satisfaction subscale (F[2, 28]=14.73, P<.001), MAL (F[1.31, 18.30]=12.05, P<.01) and the FMA (F[2, 28]=16.62, P<.001).

Conclusion

The UMA-R was feasible and safe to implement for individuals living in the community with chronic stroke. Adherence duration was identified as area of refinement. Participants demonstrated improvements in standardized UE outcomes to support initial efficacy of the UMA-R. Shared decision-making and behavior change frameworks can support the implementation of UE self-directed rehabilitation. Our results warrant the refinement and further testing of the UMA-R.

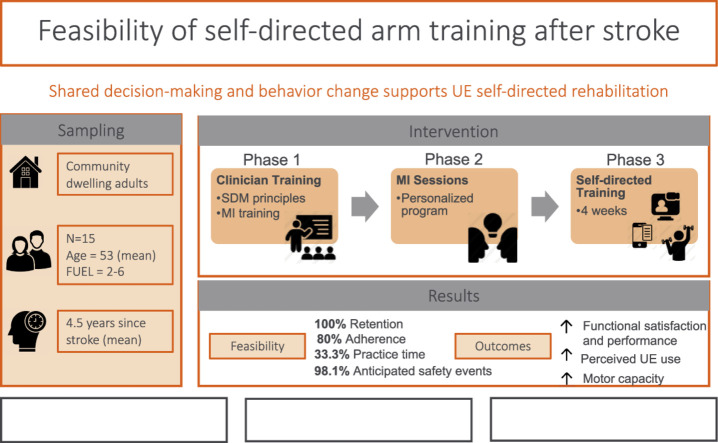

Graphical Abstract

Stroke is the leading cause of disability in adults in the United States.1,2 Approximately 50% of stroke survivors experience upper extremity (UE) impairment,3,4 and of those, over 60% have continued impairment after 6 months.5,6 Based on the International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health, impairment is defined as limitations in body function and structures.7 Limited UE functional use after stroke can affect performance with activities of daily living, return to work, and quality of life.8, 9, 10 Chronic UE disability and subsequent effect on participation and independence highlights the need for continued therapy beyond acute and subacute periods of recovery as individuals re-integrate back into the community.11

Evidence suggests that UE improvements achieved in the clinic do not automatically generalize to actual use of the affected UE in the home and community.12, 13, 14, 15, 16 In other words, what clients do in the clinic is different from what they do at home. Actual arm use, defined as the use of the affected UE in everyday activities in real world settings,17 was first introduced into the stroke literature as a key outcome for Constraint Induced Movement Therapy (CIMT) measured by the Motor Activity Log (MAL). Despite the widespread research on CIMT, actual arm use as a construct has been largely understudied. Distinct from motor capacity or functional ability, emerging literature suggests that actual arm use is a complex behavior informed by multiple factors related to the person, their environment, and the task itself.18 Therefore, interventional approaches that target actual arm use likely require self-directed training in daily activities completed in real-world settings.19

We define self-directed rehabilitation as structured motor or functional training program with clear patient objectives completed remotely in the client's home under indirect supervision of a clinician.20,21 Evidence comparing the effectiveness of home-based vs clinic-based rehabilitation has consistently demonstrated no differences in physical and motor outcomes for older adult populations with general chronic health conditions.20,22, 23, 24 Similarly, home-based UE interventions in stroke are comparable with clinic-based interventions for UE activity performance and dexterity.25 Self-directed training approaches are also effective in post stroke rehabilitation. There is a wide range of self-directed training approaches with studies using robotics, interactive gaming, CIMT, and electrical stimulation (e-stim) with CIMT and e-stim approaches demonstrating most robust improvements in UE functional ability and daily use.26 While CIMT is the most established self-directed training approach, common limitations include the narrow inclusion criteria 27,28 and limited ecological validity of constraining the less affected hand because individuals complete most daily tasks bilaterally.29,30 Additionally, no differences were reported between structured vs non-structured approaches within self-directed rehabilitation studies.19 The literature on the effectiveness of self-directed UE rehabilitation in stroke is emerging and the available evidence is mixed.19,24 More work is needed in this area to delineate key components of self-directed UE rehabilitation that effectively maximize actual arm use in daily life.

To address the need to better understand and develop effective home-based, self-directed rehabilitation approaches, Use My Arm-Remote (UMA-R) was adapted with permission from the original Use My Arm.31,32 UMA-R is a self-directed rehabilitation program informed by both motor learning principles and health behavior change frameworks. UMA-R combines several evidence-based approaches (eg, task-oriented practice, motivational interviewing (MI), ecological momentary assessments [EMAs]) to target actual arm use. Distinct from clinic-based rehabilitation, self-directed rehabilitation in the home setting must address unique challenges related to decreased motivation and adherence, because clients must self-initiate training and complete the recommended tasks with indirect therapist supervision. UMA-R uses shared decision-making (SDM) approach and EMAs to maximize intrinsic motivation and adherence.

The task-oriented approach, also referred to as task specific training in the literature, is based on the principles of neuroplasticity and the systems model of motor control.33 Task-oriented approach emphasizes the importance of selecting tasks that are meaningful to the client, training in real-world environments outside of therapy settings, and the use of motor learning principles (eg, repetition and practice, adaptation).33 UE training using a task-oriented approach can be implemented by having clients select and practice meaningful everyday tasks that require UE use. Emphasis is placed on using the client's own materials within the context of daily routines (eg, practicing brushing their hair using their own brush during their self-care routine).

SDM is a collaborative process between patients, families, and clinicians when patient values and preferences are prioritized along with existing evidence when making decisions about a specific scenario.34 MI can be used to implement an SDM approach. MI is a counseling approach based on the guiding principle that behavior change is contingent on the client- rather than the clinician-driving decision and expressing the reasons for change.35 MI has been integrated into cognitive and behavioral interventions to maximize self-initiated action and encourage activity engagement.35

EMA produces real-time data about an individual's behavior, mood, or experiences in their natural settings.36,37 EMA has been used extensively to target health behavior change such as smoking cessation, diabetes management, and weight loss.36 EMA in stroke has been used to measure caregiver burden,38 predictors of depression,39,40 and fatigue.41 The emergence and use of mobile technologies (ie, text messages or phone app) has greatly increased the ability to implement EMA successfully in a variety of clinical populations and is well-suited to capture client's daily activities in the context of their routines at home.

UMA-R addresses the unique challenges for self-directed UE training and bridges the gap between gains made in the clinic and generalized arm use in real world settings. As an initial step in intervention development and testing, the primary aim of the study was to examine the feasibility of the UMA-R protocol by addressing the following domains: recruitment and retention rates, intervention delivery, intervention acceptance, intervention adherence, and safety. The secondary aim of the study was to report initial efficacy of the UMA-R as measured by UE outcomes.

Methods

Design

This was a feasibility study that used multiple methods to collect quantitative and qualitative data to address the study aims.

Participants

The study protocol was registered with ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT05032638) and approved by the Institutional Review Board at NYU Langone Health. Participant recruitment occurred from September 2021 to September 2022 through multiple sources including referrals from the Ambulatory Care Center at Rusk Rehabilitation, stroke support groups, hospital-based study registry, stroke study registry, and community referrals in a major urban metropolitan area. Inclusion criteria for participants included: history of a stroke >6 months, over the age of 18, currently living in the community, presence of motor impairment of the affected UE (Fugl-Meyer Assessment score >0), access to a tablet or smart phone and internet connection, medically stable, and able to provide informed consent (Mini Mental Status Exam >24). Exclusion criteria included: other neurologic diagnosis, presence of spatial neglect (Star Cancellation Task score <43), receiving current rehabilitation for affected UE, or inability to answer open ended questions over the phone.

Use my arm-remote intervention

The full protocol outlining detailed description of the intervention, data collection procedures, outcomes measures, and data analysis methods has been published elsewhere.42 Briefly, the UMA-R consisted of 3 phases. In Phase 1, occupational therapists from Rusk Rehabilitation with extensive clinical experience in neurorehabilitation, completed MI training.

In Phase 2, each participant met virtually with their occupational therapist for MI sessions using a SDM approach to generate personalized goals, identify specific everyday activities, and develop a customized schedule to implement during the training period. Additionally, occupational therapists explored participants’ confidence and readiness to complete self-directed training. Participants advanced to next phase once they rated their confidence and readiness to change at 7 or above on a 10-point scale.

In Phase 3, participants completed task-oriented training of self-selected everyday activities that promoted affected UE use. Participants practiced functional tasks with their own materials at home to support personalized UE goals established in Phase 2 (eg, hand-writing, meal preparation, grooming, tying laces). Based on clinician assessment, preparatory activities (eg, self-range of motion of the hand, wrist, scapula; weightbearing of the hand; repetitive task practice of opening/closing of hand) were integrated into personalized training plan as needed to maximize success of functional task practice. Study staff communicated daily with participants through daily EMA surveys using a commercial appa to monitor the frequency and duration of arm training, motivation levels, and experience of adverse reactions. Expiwell was used to measure ecological momentary assessment through a daily survey via an app on participant's phones. Occupational therapists communicated weekly with participants using Zoom for weekly check-ins to discuss challenges and modify treatment plans as needed. See figure 1 for overall study diagram.

Fig 1.

Overall study diagram.

Feasibility domain

Feasibility (study Aim 1) was assessed in the following domains: recruitment, retention, intervention acceptance, intervention delivery, adherence, and safety.43 Quantitative data (study documentation, EMA survey responses) and qualitative data (participant interviews) were used to assess feasibility domains.

UE outcome measures

To address Aim 2, we collected 4 quantitative outcomes at baseline, discharge, and 4-week follow-up to capture UE change. We assessed multiple aspects of the UE including, perceived satisfaction and performance of UE function (Canadian Occupational Performance Measure [COPM]), self-reported arm use in daily activities at home (MAL), motor impairment (Fugl Meyer Assessment [FMA]), and real-world arm use (accelerometry).b Actigraph GT9X Link was used for accelerometry data via a wrist wear time sensor. See Kim et al.42 for a full description of each measure including psychometric properties and scoring guidelines.

Data analysis

Participants were characterized using demographics including age, time since stroke, stroke characteristics, and UE impairment and functional levels. Feasibility domains were assessed using multiple study documents and participant interviews. See table 1 for additional details on feasibility domains, methods of data collection and analysis.

Table 1.

Data collection and analysis plan

| Study Aims | Quantitative Data | Qualitative Data | Criteria/Analysis |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aim 1: Feasibility | |||

| Recruitment | Recruitment rate Source: screening log |

Participants enrolled divided by total contacted | |

| Intervention delivery | Therapist self-rating scores on MI training Phase 1: # visits to complete Phase 2: completion rate for weekly check ins |

Average scores MI training questionnaire Phase 1: completion within 6 sessions Phase 2: rate of completion of 3 weekly check in visits |

|

| Intervention acceptance | Recommendation rate Source: study documents |

Semi-structured interviews with participants | Percentage of participants who recommend study to others, narrative summary of qualitative responses |

| Intervention Retention |

Retention rate Source: study documents |

Percentage of participants who completed entire study | |

| Intervention adherence | Frequency (total number of days practiced compared with total available days) Duration (average daily minutes of practice) Source: EMA survey data |

Criteria for adherence to frequency (≥.60) Criteria for adherence to duration of practice (>30 min) |

|

| Safety | Adverse symptoms Source: EMA survey data |

Sum of anticipated and unanticipated adverse events over duration of study | |

| Aim 2: Change in UE outcomes | |||

| Motor capacity | FMA-UE |

Mean change scores, standard deviations, analysis of variance Mean change scores, standard deviations, analysis of variance |

|

| Perceived actual arm use | MAL | ||

| Person-centered outcomes | COPM | ||

| Accelerometry | Duration of use Bilateral magnitude ratio |

||

Abbreviation: FMA-UE, Fugl-Meyer Assessment-Upper Extremity.

Estimates of potential effect for FMA, MAL, COPM, and accelerometry data metrics (ie, duration of use) were reported using mean change scores, 95% confidence intervals, variance, and standard deviations (SDs).44 Variance across means for all outcome measures were compared at the 3 study timepoints using parametric or non-parametric statistics. Effect size was calculated from these data to estimate potential samples sizes for a future larger study. SPSS v19c was used to conduct all analyses and with an intention to treat approach.

There is a wide variation in methods to calculate accelerometry metrics including determination of activity counts and duration of use with no standard methodology agreed upon in stroke rehabilitation. See appendix 1 for the methodology used in our study, an overview of data processing, and calculation of activity counts and duration of use.

Results

Participant demographics

Fifteen individuals with stroke met our inclusion criteria and completed the UMA-R protocol. We had no early withdrawals or missing data. All participants lived in the community with time post stroke ranging from 6 months to 13 years. With the exception of 1 participant, individuals were modified independent with community mobility. Based on Functional Upper Extremity Level classification,45 participants had a wide range of UE functional levels, ranging from dependent stabilizer (limited function) to functional assist (high function). See table 2 for full details of participant demographics.

Table 2.

Participant demographics, N=15

| Variable | Participants (N=15) |

|---|---|

| Age, mean ± SD | 53.08 (14.51) |

| Sex, n (%) | |

| Men | 9 (60.00) |

| Women | 6 (40.00) |

| Race, n (%) | |

| White | 9 (60.00) |

| Black | 4 (26.67) |

| Asian | 1 (6.67) |

| Hispanic | 1 (6.67) |

| Living situation, n (%) | |

| With spouse/partner | 9 (60.00) |

| Alone | 2 (13.33) |

| Other (with other family members) | 4 (26.67) |

| Current level of community mobility, n (%) | |

| Independent with or without AD | 14 (93.33) |

| Needs physical assistance | 1 (6.67) |

| Time since stroke in years, (mean range) | 4.50 (0.55-13.18) |

| Type of stroke, n (%) | |

| Ischemic | 9 (60.00) |

| Hemorrhagic | 3 (20.00) |

| Other | 2 (13.33) |

| UE affected by stroke, n (%) | |

| Left | 8 (53.33) |

| Right | 7 (46.67) |

| UE FUEL levels, n (%) | |

| Non-functional | 0 |

| Dependent stabilizer | 1 (6.67) |

| Independent stabilizer | 4 (26.67) |

| Gross assist | 3 (20.00) |

| Semi-functional assist | 4 (26.67) |

| Functional assist | 3 (20.00) |

| Fully functional | 0 |

Abbreviation: AD, adaptive device; FUEL, Functional Upper Extremity Level.

Feasibility domains

We achieved a 36.5% recruitment rate (target 30%). All participants completed the study, resulting in a 100% retention rate. All 15 participants stated that they would recommend UMA-R program to someone else, reflecting a high acceptance of the intervention.

Intervention delivery was determined in multiple ways. Therapists average self-rating of implementing MI during the protocol was 5.83 (out of 7) for competence and 6.10 (out of 7) for adherence. It took on average 3.2 visits to complete phase 2 activities (identifying barriers to self-directed training, personalized goal setting, and personalized treatment planning). These results are well within the 3-6 visits allotted within the protocol. During phase 3, the interventionists were able to complete the 3 weekly Zoom check-ins with participants at 100% completion rate.

Adherence to self-directed training was collected through participant responses to daily surveys for frequency and duration of practice. Eighty percent of participants met the criteria for adherence frequency with 12 participants reporting self-directed training in at least 12 out of the 20 possible training days. For duration of practice, 33.3% of participants met the criteria with 5 out of the 15 participants reported practicing for at least 30 minutes per day on average. This did not meet our internal criteria for having most (>50%) participants practice for at least 30 minutes a day.

Safety data were collected daily as part of the EMA survey. A vast majority (98.1%) of reported adverse events were anticipated. Most common reported symptoms were mild to moderate muscle soreness or stiffness, which resolved with rest. All reported events were monitored and discussed during weekly check-ins with the interventionists. One participant reported an unanticipated adverse (new onset of seizure activity) during the follow-up period. Per participant's physician, this event was most likely due to the history of CVA and not related to study participation.

Preliminary efficacy data of UE outcomes

To assess whether the UMA-R program shows promise of being successful with individuals with stroke living in the community, we examined individual and group level change scores on UE outcome measures. Distribution of data for UE outcomes were normally distributed, and therefore means, SDs, and parametric methods were reported for the group level analyses.

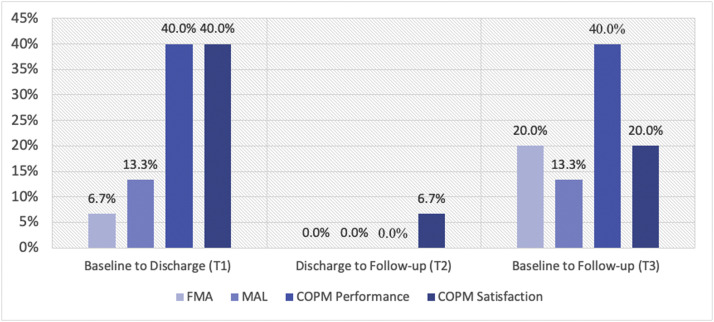

Figure 2 provides a visual summary of individual change scores for the standardized outcome measures with established minimally clinically important difference (MCID) thresholds at T1 (baseline to discharge), T2 (discharge to follow-up), and T3 (baseline to follow-up). The highest rates of clinical improvement were at T1 and T3 for COPM performance subscale (40%), T1 for COPM satisfaction subscale (40%), T3 for FMA (20%), and T1 and T3 for MAL (13%).

Fig 2.

Percentage of participants who reached clinically significant improvements (MCID threshold) for the FMA, MAL, COPM-Performance, and COPM Satisfaction at T1, T2, and T3, N=15. MCID for FMA=Δ 5.25 points, MCID for MAL=Δ1.0 point, MCID for COPM Performance=Δ3.0 points, MCID for COPM Satisfaction=Δ3.2 points.

We used an analysis of variance (ANOVA) to compare group means across the 3 timepoints for each outcome measure. See table 3 for ANOVA results. We found a significant main effect for FMA (F[2, 28]=16.62, P<.001), MAL (F[1.31, 18.30]=12.05, P<.01), COPM performance (F[1.42, 19.83]=17.72, P<.001), and COPM satisfaction (F[2, 28]=14.73, P<.001). Bonferroni post hoc analysis further determined that there was significant improvement on all outcome measures at T1 (baseline to discharge) and T3 (baseline to follow-up). Duration of use metric (captured using accelerometry) was not significant.

Table 3.

Comparison of group means at baseline, discharge, and follow up, N=15

| Baseline | Discharge | Follow-up | F | P | Eta-squared (η2) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | ||||

| MAL | 1.72 (1.23) | 2.16 (1.27) | 2.28 (1.30) | 12.05 | .001† | .463 |

| FMA | 35.13 (15.02) | 37.73 (14.68) | 38.53 (14.05) | 16.62 | <.001‡ | .543 |

| COPM_perf | 3.22 (1.50) | 5.26 (1.52) | 5.60 (1.75) | 17.71 | <.001‡ | .559 |

| COPM_satis | 2.88 (1.67) | 5.49 (1.75) | 4.86 (2.31) | 14.73 | <.001‡ | .513 |

| Duration of UE use | 713.56 (315.47) | 917.48 (406.17) | 797.30 (527.34) | .90 | .420 | .060 |

Abbreviations: COPM perf, Canadian Occupational Performance Measure, performance subscale; COPM satis, Canadian Occupational Performance Measure, satisfaction subscale; UE, upper extremity.

P<.01.

P<.001.

Preliminary effect sizes for the UE outcome measures used in the study were calculated with the eta squared (η2) statistic as a measure of effect size for ANOVA models. Using46,47 guidelines for magnitude of effects, all outcome measures had a large effect: FMA (0.54), MAL (0.46), COPM satisfaction (0.51), and COPM performance (0.56).

Discussion

We completed a feasibility study on 15 individuals with chronic stroke living in the community. For the primary aim, we demonstrated feasibility of the UMA-R protocol for recruitment, retention, acceptability, intervention delivery, adherence frequency, and safety. For the secondary aim, we reported the initial efficacy of the UMA-R on UE outcome measures. Our results show promise of the UMA-R to be acceptable and beneficial to individuals with chronic stroke living in the community. In the subsequent sections, we will further discuss the key components of the UMA-R protocol in order to inform the next phase of intervention testing and development.

Shared decision-making

Participants positively endorsed setting their own goals because it was more personal, more motivating, and increased their commitment. One participant stated he needed to “figure out ways to do it” because it was his goal. While another participant stated “I liked it because you know yourself best”. However, participants also acknowledged that setting personalized goals was difficult and stated the importance of working with their occupational therapist for additional ideas and structure. Our results support existing literature on the benefits of SDM (eg, improved performance, sense of goal achievement, and therapy engagement),34,48,49 as well as the challenge of implementing a complex process.34,50,51 Additional work is needed to understand implementation strategies for SDM within the context of stroke rehabilitation. We explored occupational therapists’ perspectives on the implementation SDM approach during the UMA-R, which will be published in a separate paper.

Ecological momentary assessment

Our results demonstrate that EMA surveys using a phone app can be used to monitor adherence and response to training of daily UE self-directed training at home for individuals with chronic stroke. All 15 participants had a neutral to good response about completing the daily survey stating that “it was fine” or “it was useful, the app was good” and a “good reminder to consistently do the work”.

A potential concern for delivering remote rehabilitation is the lack of direct supervision of patients while training; however, the use of EMA to sample daily adverse events was effective in monitoring for anticipated and unanticipated events. Importantly, UMA-R was safe—with the overwhelming majority of reported symptoms being anticipated and related to practice.

Common suggestions for improving the EMA questions including making the motivation question more specific (eg, asking about enthusiasm to practice specific personalized tasks rather than a general level of motivation), providing open comments feature so that they could explain reason for their responses, and providing performance feedback “some way to see progress, for example a graph, that shows you what you were doing or reporting the last week or two”. These suggestions will be incorporated into the refinement of the EMA survey for the next iteration.

Adherence to self-directed training

We achieved high rates for adherence frequency (80%) but lower rates of duration of daily practice (33%). This indicates a majority of participants completed self-directed arm training every day; however, only a third of participants were able to practice for greater than 30 minutes daily. One potential reason for this result is work and life demands. While all participants determined their own practice schedules, participants who worked or had full schedules at baseline had a particularly difficult time reaching the 60 minutes of arm practice. “I had work responsibilities” and “I don't know if I could do that [more than 30 minutes] based on my work schedule”. Notably, all participants strongly endorsed the weekly check-ins with their therapist to help with adherence stating that it was “critical, absolutely critical” because it facilitated accountability, making adjustments, and establishing good communication. However, additional structure or real time feedback of arm training may be needed to increase the duration of daily practice in between weekly check-ins.

Real-time feedback of desired behaviors can support health behavior change outside of the clinic.52 Wearable sensors have used home-based interventions to provide real-time feedback during UE training, which yielded more repetitions and longer practice duration compared with UE training without sensors.53,54 The use of wearable sensors to provide performance feedback in real time of UE self-training may be a viable solution to improve duration of daily practice in the UMA-R.

We asked both the therapists and the participants about the length of the training period at 4 weeks. All interventionists endorsed extending the training period to 8 weeks, with less frequent check ins in the second month. Of the 6 participants who had an opinion, all endorsed extending the duration to 8-12 weeks. Based on stakeholder feedback and motor learning practice principles,55 a distributed practice approach will be considered decreasing the duration of daily practice to 30 minutes and increasing the overall training period to 8 weeks.

Study limitations

The current study relied on self-report to collect the adherence frequency and duration data, which has inherent limitations for accuracy because it relies on participants’ memory recall. While our sample provides initial support that the UMA-R is potentially beneficial for a heterogeneous mix of individuals, the UMA-R relied heavily on verbal communication because most visits are completed remotely (phone app, Zoom visits). This limits participation for individuals with decreased English proficiency and for those with moderate to severe aphasia.

Future directions

There are several recommendations for future iterations of the UMA-R. To improve adherence duration, we will integrate wearable sensors to provide real-time performance feedback during self-directed arm training to maximize engagement and motivation. We will increase the specificity and personalization of EMA questions and include options for subjective explanations. Spanish is the most prevalent non-English language spoken at home in New York City metropolitan area,56 therefore adaption of UMA-R into Spanish would increase the inclusion and participation of Spanish-speaking participants in future research.

Conclusions

The UMA-R is an acceptable, safe, and beneficial self-directed training intervention to address UE use in daily life for individuals with chronic stroke. Adherence duration was identified as an area of refinement. Participants demonstrated improvements in UE outcomes for perceived satisfaction and performance of personalized activities (COPM), self-reported arm use in daily activities (MAL), and motor capacity (FMA) after completing the UMA-R program. Our results support the integration of shared decision making and behavior change frameworks into self-directed UE rehabilitation approaches and warrant further intervention refinement and testing of the UMA-R.

Suppliers

a. ExpiWell; b. Actigraph GT9X Link; c. SPSS v 27; IBM.

Footnotes

This study was funded by the American Occupational Therapy Foundation Interventional Research Grant (AOTFIRG21KIM).

Disclosures: The authors report no conflict of interest.

Clinical trials registration: NCT05032638.

Appendix 1

Data processing

To calculate performance metrics for the bilateral upper extremities (UEs), we initially sorted the data by the self-logged timestamps. This step allowed us to distinguish between periods of use and non-use in the accelerometer data.

Determination of activity counts and duration of use

For computing the paretic UE use/activity counts, we performed the following steps for each of the three sessions:

We first took the square root of the sum of the squares of the three accelerometer axes at each time point for the paretic UE. This step resulted in a single accelerometer time series for each subject per session. We next calculated the average accelerometer value during the non-use periods for each session. This average value served as the threshold for determining activity counts. We finally compared the acceleration values from the use time period with the threshold (average non-use value). If the average acceleration of the paretic side exceeded the average value from the non-use period, it was considered an activity count [1,2,3]. Since accelerometry data were captured at a rate of 100Hz, we divided the values by 100 to convert it to seconds, then divided by 60 to convert the data to minutes.

References

-

1.

Choi L, Liu Z, Matthews CE, Buchowski MS. Validation of accelerometer wear and nonwear time classification algorithm. Med Sci Sports Exerc. Feb 2011;43(2):357-64. 10.1249/MSS.0b013e3181ed61a3

-

2.

Esliger DW, Copeland JL, Barnes JD, Tremblay MS. Standardizing and Optimizing the Use of Accelerometer Data for Free-Living Physical Activity Monitoring. Journal of Physical Activity and Health. 01 Jul. 2005 2005;2(3):366-383. 10.1123/jpah.2.3.366

-

3.

Migueles JH, Cadenas-Sanchez C, Ekelund U, et al. Accelerometer Data Collection and Processing Criteria to Assess Physical Activity and Other Outcomes: A Systematic Review and Practical Considerations. Sports Medicine. 2017/09/01 2017;47(9):1821-1845. 10.1007/s40279-017-0716-0

References

- 1.Kochanek KD, Murphy SL, Xu J, Arias E. Mortality in the United States, 2013. NCHS Data Brief. 2014;(178):1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Benjamin EJ, Virani SS, Callaway CW, et al. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics-2018 Update: a report From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2018;137:e67–492. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Simpson LA, Hayward KS, McPeake M, Field TS, Eng JJ. Challenges of estimating accurate prevalence of arm weakness early after stroke. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 2021;35:871–879. doi: 10.1177/15459683211028240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Persson HC, Parziali M, Danielsson A, Sunnerhagen KS. Outcome and upper extremity function within 72 hours after first occasion of stroke in an unselected population at a stroke unit. A part of the SALGOT study. BMC Neurol. 2012;12:162. doi: 10.1186/1471-2377-12-162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Broeks JG, Lankhorst GJ, Rumping K, Prevo AJ. The long-term outcome of arm function after stroke: results of a follow-up study. Disabil Rehabil. 1999;21:357–364. doi: 10.1080/096382899297459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Allison R, Shenton L, Bamforth K, Kilbride C, Richards D. Incidence, time course and predictors of impairments relating to caring for the profoundly affected arm after stroke: a systematic review. Physiother Res Int. 2016;21:210–227. doi: 10.1002/pri.1634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stucki G, Ewert T, Cieza A. Value and application of the ICF in rehabilitation medicine. Disabil Rehabil. 2002;24:932–938. doi: 10.1080/09638280210148594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hmaied Assadi S, Barel H, Dudkiewicz I, Gross-Nevo RF, Rand D. Less-affected hand function is associated with independence in daily living: a longitudinal study poststroke. Stroke. 2022;53:939–946. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.121.034478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ekstrand E, Brogårdh C. Life satisfaction after stroke and the association with upper extremity disability, sociodemographics, and participation. PM R. 2022;14:922–930. doi: 10.1002/pmrj.12712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Houwink A, Nijland RH, Geurts AC, Kwakkel G. Functional recovery of the paretic upper limb after stroke: who regains hand capacity? Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2013;94:839–844. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2012.11.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Barker RN, Gill TJ, Brauer SG. Factors contributing to upper limb recovery after stroke: a survey of stroke survivors in Queensland Australia. Disabil Rehabil. 2007;29:981–989. doi: 10.1080/09638280500243570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Doman CA, Waddell KJ, Bailey RR, Moore JL, Lang CE. Changes in upper-extremity functional capacity and daily performance during outpatient occupational therapy for people with stroke. Am J Occup Ther. 2016;70 doi: 10.5014/ajot.2016.020891. 7003290040p1-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rand D, Eng JJ. Predicting daily use of the affected upper extremity 1 year after stroke. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2015;24:274–283. doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2014.07.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rand D, Eng JJ. Disparity between functional recovery and daily use of the upper and lower extremities during subacute stroke rehabilitation. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 2012;26:76–84. doi: 10.1177/1545968311408918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Waddell KJ, Strube MJ, Bailey RR, et al. Does task-specific training improve upper limb performance in daily life poststroke? Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 2017;31:290–300. doi: 10.1177/1545968316680493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lang CE, Holleran CL, Strube MJ, et al. Improvement in the capacity for activity versus improvement in performance of activity in daily life during outpatient rehabilitation. J Neurol Phys Ther. 2023;47:16–25. doi: 10.1097/NPT.0000000000000413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Uswatte G, Taub E. Implications of the learned nonuse formulation for measuring rehabilitation outcomes: lessons from constraint-induced movement therapy. Rehabil Psychol. 2005;50:34–42. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim GJ, Lebovich S, Rand D. Perceived facilitators and barriers for actual arm use during everyday activities in community dwelling individuals with chronic stroke. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19:11707. doi: 10.3390/ijerph191811707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ballester BR, Winstein C, Schweighofer N. Virtuous and vicious cycles of arm use and function post-stroke. Front Neurol. 2022;13 doi: 10.3389/fneur.2022.804211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Anderson L, Sharp GA, Norton RJ, et al. Home-based versus centre-based cardiac rehabilitation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;6 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007130.pub4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wong Y, Ada L, Wang R, Månum G, Langhammer B. Self-administered, home-based, upper limb practice in stroke patients: a systematic review. J Rehabil Med. 2020;52:jrm00118. doi: 10.2340/16501977-2738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Aoike DT, Baria F, Kamimura MA, Ammirati A, Cuppari L. Home-based versus center-based aerobic exercise on cardiopulmonary performance, physical function, quality of life and quality of sleep of overweight patients with chronic kidney disease. Clin Exp Nephrol. 2018;22:87–98. doi: 10.1007/s10157-017-1429-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ashworth NL, Chad KE, Harrison EL, Reeder BA, Marshall SC. Home versus center based physical activity programs in older adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005;2005 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004017.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jansons P, Robins L, O'Brien L, Haines T. Gym-based exercise and home-based exercise with telephone support have similar outcomes when used as maintenance programs in adults with chronic health conditions: a randomised trial. J Physiother. 2017;63:154–160. doi: 10.1016/j.jphys.2017.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nascimento LR, Gaviorno LF, de Souza Brunelli M, Gonçalves JV, Arêas F. Home-based is as effective as centre-based rehabilitation for improving upper limb motor recovery and activity limitations after stroke: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Clin Rehabil. 2022;36:1565–1577. doi: 10.1177/02692155221121015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Da-Silva RH, Moore SA, Price CI. Self-directed therapy programmes for arm rehabilitation after stroke: a systematic review. Clin Rehabil. 2018;32:1022–1036. doi: 10.1177/0269215518775170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wolf SL, Winstein CJ, Miller JP, et al. Effect of constraint-induced movement therapy on upper extremity function 3 to 9 months after stroke: the EXCITE randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2006;296:2095–2104. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.17.2095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nijland R, Kwakkel G, Bakers J, van Wegen E. Constraint-induced movement therapy for the upper paretic limb in acute or sub-acute stroke: a systematic review. Int J Stroke. 2011;6:425–433. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-4949.2011.00646.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kilbreath SL, Heard RC. Frequency of hand use in healthy older persons. Aust J Physiother. 2005;51:119–122. doi: 10.1016/s0004-9514(05)70040-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bailey RR, Klaesner JW, Lang CE. Quantifying real-world upper-limb activity in nondisabled adults and adults with chronic stroke. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 2015;29:969–978. doi: 10.1177/1545968315583720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Capasso N, Feld-Glazman R, Herman T. Enhancing upper extremity motor function after brain injury: daily practice assignments for clients in an acute rehabilitation setting wtih the Use My Arm Program. 2013: Poster presented at: American Occupational Therapy Association Conference; April 25-28, 2013; San Diego, CA.

- 32.Capasso N, McClelland K, Fiumara E. Use my arm: improving functional use of the affected upper extremity through additional therapy and designated practice sessions. 2016: American Occupational Therapy Association Conference; April 7-10, 2016; Chicago, IL.

- 33.Mathiowetz V, Nilsen D, Gillen G. In: Stroke rehabilitation: a function-based approach. 5th ed. Gillen G, Nilson D, editors. Elsevier; Philadelphia, PA: 2021. Task-oriented approach to stroke rehabilitation; pp. 59–79. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Armstrong MJ. Shared decision-making in stroke: an evolving approach to improved patient care. Stroke Vasc Neurol. 2017;2:84–87. doi: 10.1136/svn-2017-000081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Miller WR, Moyers TB. Motivational interviewing and the clinical science of Carl Rogers. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2017;85:757–766. doi: 10.1037/ccp0000179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Heron KE, Smyth JM. Ecological momentary interventions: incorporating mobile technology into psychosocial and health behaviour treatments. Br J Health Psychol. 2010;15(Pt 1):1–39. doi: 10.1348/135910709X466063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shiffman S, Stone AA, Hufford MR. Ecological momentary assessment. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2008;4:1–32. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.3.022806.091415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Noguchi T, Nakagawa-Senda H, Tamai Y, et al. The association between family caregiver burden and subjective well-being and the moderating effect of social participation among Japanese adults: a cross-sectional study. MDPI. 2020:87. doi: 10.3390/healthcare8020087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jean FA, Swendsen JD, Sibon I, Fehér K, Husky M. Daily life behaviors and depression risk following stroke: a preliminary study using ecological momentary assessment. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. 2013;26:138–143. doi: 10.1177/0891988713484193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Neff AJ, Lee Y, Metts CL, Wong AWK. Ecological momentary assessment of social interactions: associations with depression, anxiety, pain, and fatigue in individuals with mild stroke. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2021;102:395–405. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2020.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lenaert B, Neijmeijer M, van Kampen N, van Heugten C, Ponds R. Poststroke fatigue and daily activity patterns during outpatient rehabilitation: an experience sampling method study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2020;101:1001–1008. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2019.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kim GJ, Gahlot A, Magsombol C, Waskiewicz M, Capasso N, Van Lew S, Goverover Y, Dickson VV. Protocol for a remote home-based upper extremity self-training program for community-dwelling individuals after stroke. Contemp Clin Trials Commun. 2023;33:101112. doi: 10.1016/j.conctc.2023.101112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Aschbrenner KA, Kruse G, Gallo JJ, Plano Clark VL. Applying mixed methods to pilot feasibility studies to inform intervention trials. Pilot Feasibility Stud. 2022;8:217. doi: 10.1186/s40814-022-01178-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Eldridge SM, Chan CL, Campbell MJ, et al. CONSORT 2010 statement: extension to randomised pilot and feasibility trials. BMJ. 2016;355:i5239. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i5239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Van Lew S, Geller D, Feld-Glazman R, Capasso N, Dicembri A, Zipp GP. Development and preliminary reliability of the Functional Upper Extremity Levels (FUEL) Am J Occup Ther. 2015;69 doi: 10.5014/ajot.2015.016006. 6906350010p1-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cohen J. Academic Press; New York, NY: 2013. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fritz CO, Morris PE, Richler JJ. Effect size estimates: current use, calculations, and interpretation. J Exp Psychol Gen. 2012;141:2–18. doi: 10.1037/a0024338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sugavanam T, Mead G, Bulley C, Donaghy M, Van Wijck F. The effects and experiences of goal setting in stroke rehabilitation–a systematic review. Disabil Rehabil. 2013;35:177–190. doi: 10.3109/09638288.2012.690501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Voogdt-Pruis HR, Ras T, van der Dussen L, et al. Improvement of shared decision making in integrated stroke care: a before and after evaluation using a questionnaire survey. BMC Health Serv Res. 2019;19:936. doi: 10.1186/s12913-019-4761-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tinetti M, Dindo L, Smith CD, et al. Challenges and strategies in patients’ health priorities-aligned decision-making for older adults with multiple chronic conditions. PLoS One. 2019;14 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0218249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Baker A, Cornwell P, Gustafsson L, Stewart C, Lannin NA. Developing tailored theoretically informed goal-setting interventions for rehabilitation services: a co-design approach. BMC Health Serv Res. 2022;22:811. doi: 10.1186/s12913-022-08047-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Winstein C, Varghese R. Been there, done that, so what's next for arm and hand rehabilitation in stroke? Neurorehabilitation. 2018;43:3–18. doi: 10.3233/NRE-172412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Chae SH, Kim Y, Lee KS, Park HS. Development and clinical evaluation of a Web-based upper limb home rehabilitation system using a Smartwatch and machine learning model for chronic stroke survivors: prospective comparative study. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2020;8:e17216. doi: 10.2196/17216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Schwerz de Lucena D, Rowe JB, Okita S, Chan V, Cramer SC, Reinkensmeyer DJ. Providing real-time wearable feedback to increase hand use after stroke: a randomized, controlled trial. Sensors (Basel) 2022;22:6938. doi: 10.3390/s22186938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Magill R, Anderson DI. 12th ed. McGraw-Hill Publishing; New York: 2020. The amount and distribution of practice Motor learning and control: concepts and applications. chap 417-28. [Google Scholar]

- 56.U.S. Census Bureau. Population Estimates, July 1, 2022 — New York. Available at: https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/NY. Accessed June 3, 2023.