Abstract

Despite the revolutionary success of chimeric antigen receptor (CAR)-T therapy for hematological malignancies, successful CAR-T therapies for solid tumors remain limited. One major obstacle is the scarcity of tumor-specific cell-surface molecules. One potential solution to overcome this barrier is to utilize antibodies that recognize peptide/major histocompatibility complex (MHCs) in a T cell receptor (TCR)-like fashion, allowing CAR-T cells to recognize intracellular tumor antigens. This study reports a highly specific single-chain variable fragment (scFv) antibody against the MAGE-A4p230-239/human leukocyte antigen (HLA)-A∗02:01 complex (MAGE-A4 pMHC), screened from a human scFv phage display library. Indeed, retroviral vectors encoding CAR, utilizing this scFv antibody as a recognition component, efficiently recognized and lysed MAGA-A4+ tumor cells in an HLA-A∗02:01-restricted manner. Additionally, the adoptive transfer of T cells modified by the CAR-containing glucocorticoid-induced tumor necrosis factor receptor (TNFR)-related receptor (GITR) intracellular domain (ICD), but not CD28 or 4-1BB ICD, significantly suppressed the growth of MAGE-A4+ HLA-A∗02:01+ tumors in an immunocompromised mouse model. Of note, a comprehensive analysis revealed that a broad range of amino acid sequences of the MAGE-A4p230-239 peptide were critical for the recognition of MAGE-A4 pMHC by these CAR-T cells, and no cross-reactivity to analogous peptides was observed. Thus, MAGE-A4-targeted CAR-T therapy using this scFv antibody may be a promising and safe treatment for solid tumors.

Keywords: CAR, MAGE-A4 peptide, MHC complex, pMHC, GITR, ICD

Graphical abstract

Miyahara and colleagues reported that the intracellular tumor antigen MAGE-A4 could be targeted by a novel CAR-T cell therapy utilizing an antibody with high affinity and specificity for the MAGE-A4p230-239/HLA-A∗02:01 complex. Additionally, the intracellular domain of GITR in CAR constructs enhanced in vivo function compared with CD28 and 4-1BB.

Introduction

The clinical efficacy of CD19-targeted CAR-T cell therapy has revolutionized the treatment of patients with B cell-lineage hematologic malignancies.1,2,3 In this context, the development of chimeric antigen receptor (CAR)-T cell therapy for the treatment of patients with solid tumors is highly anticipated. However, the wider application of CAR-T therapy for solid tumors is limited so far.4 One major reason for this is the paucity of cell-surface molecules highly specific to tumor cells. Although a promising clinical result for CAR-T therapy targeting cell-surface molecule disialoganglioside (GD2) has recently been reported,5 the clinical efficacy of most of CAR-T therapies targeting cell-surface molecules remains undefined. In contrast, the majority of tumor-specific antigens belong to intracellular antigens. Therefore, there is a need for the development of CAR-T cells capable of recognizing intracellular tumor-specific antigens.

CAR-T cell therapy, which takes advantage of the variable fragment of a T cell receptor (TCR)-like antibody that recognizes the intracellular antigen-derived peptide/major histocompatibility complex (pMHC) on the cell surface has been advocated as a promising strategy.6,7,8,9 Several groups, including our own,10 have reported the potential usefulness of CAR-T therapies targeting intracellular tumor antigens, such as NY-ESO-1, Wilms tumor 1, and PR1, using TCR-like antibodies.11,12,13,14,15 In addition, TCR-like antibodies that are specific to shared mutated antigen-derived peptides/MHCs have recently been developed.16 Although this strategy has attracted considerable attention, caution must be exercised to avoid fatal damage owing to the substantial risk of cross-reactivity of TCR-like antibodies with normal tissues.17,18,19

In this study, we focused on the cancer/testis antigen MAGE-A4 as a promising intracellular target antigen of CAR-T cell therapy for solid tumors. MAGE-A4 is a member of the MAGE family of genes and is frequently expressed in various types of tumors, but not in normal tissues except the placenta and testis.20,21 To date, several MAGE-A4-derived pMHCs recognized by cytotoxic CD8+ T cells have been reported.22,23,24,25 In this study, we selected the MAGE-A4p230-239/human leukocyte antigen (HLA)-A∗02:01 complex (MAGE-A4 pMHC)25 with well-established crystal structure26 as a promising therapeutic target. Given that cell therapy targeting MAGE-A4 has significant therapeutic potential applicable to a large number of patients with solid tumors, the development of TCR-T therapies targeting the same MAGE-A4 pMHC is currently underway.27,28

On the other hand, there are persistent concerns that currently used CAR structures are still not fully optimized for the treatment of solid tumors. To address this issue, in this study we investigated whether the intracellular domain of glucocorticoid-induced tumor necrosis factor receptor (TNFR)-related receptor (GITR), which has been reported to play an essential role in potent immunity exerted by CD4+ and CD8+ T cells against viruses and tumors,29,30 might confer T cells with superior in vivo efficacy against tumors.

Here, we aimed to evaluate the preclinical efficacy and safety of a novel CAR-T therapy against solid tumors using the MAGE-A4 pMHC-specific antibody and GITR intracellular domain (ICD). Our results will lay the foundation for CAR-T cell therapy, which uses a TCR-like antibody specific to MAGE-A4 pMHC. This treatment approach offers a new, potent, and safe treatment for solid tumors.

Results

Isolation of a single-chain variable fragment antibody highly specific to the MAGE-A4p230-239/HLA∗A02:01 complex

Among the MAGE-A4-derived peptide/MHC complexes, we focused on the MAGE-A4p230-239/HLA∗A02:01 complex as a well-characterized target for screening single-chain variable fragment (scFv) antibodies in a human scFv phage display library. To exclude MHC-binding antibodies, we used HLA-A∗02:01 loaded with several HLA-A∗02:01 binding peptides derived from cytomegalovirus (CMV), Melan A, and NY-ESO-1 as competitors. Initially, we identified four independent positive clones that bound specifically to MAGE-A4 pMHC and investigated their inability to bind to irrelevant pMHCs (CMV, Glypican-3, Melan A, NY-ESO-1, and MAGE-A3/HLA-A∗02:01 complexes) (Figure 1A). An enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) showed that a single clone (#17) passed all criteria and was confirmed to bind to MAGE-A4 pMHC with a KD value of 22 nM by surface plasmon resonance analysis (Figure 1B).

Figure 1.

scFv antibody #17 recognizes MAGE-A4p230-239/HLA-A∗02:01 with high specificity

(A) The culture supernatant of scFv #17 specifically reacted with MAGE-A4 pMHC as detected by anti-cp3 (capsid protein 3) antibody followed by HRP-conjugated anti-mouse IgG. (B) MAGE-A4p230-239/HLA-A∗02:01 was immobilized on a CAP sensor chip as the ligand, and 100, 200, 400, and 600 nM scFv #17-conjugated with His-FLAG for MAGE-A4p230-239/HLA-A∗02:01 was applied as the analyte. After 120 s of association reaction, the dissociation reaction was measured, and the KD value was calculated by global fitting. (C) Alanine substitution analysis identified MAGE-A4p230-239 peptide residues essential for recognition by scFv #17. The MAGE-A4p230-239 peptide sequence was substituted with alanine from residues 1 through 10. T2 was pulsed with the indicated peptides (see Table S1 for sequences) at 10 μM for 1 h. Subsequently, the cells were stained with an anti-DDDDK mouse monoclonal antibody for 1 h at R.T. and then with an Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated goat anti-mouse polyclonal antibody for 1 h at room temperature (RT) in the dark. Finally, the cells were analyzed by flow cytometry. (D) The peptides in (C) were subjected to an HLA-stabilizing assay to determine the critical amino acids required for HLA-A∗02:01 binding. T2 cells were used as peptide-loading cells and their HLA-A∗02:01 expression was determined by flow cytometry. (E) Validation of potential risk peptides derived from the human proteome database. T2 cells were pulsed with the indicated peptides (see Table S2 for sequences) at 10 μM for 1 h and analyzed by flow cytometry as described in (C). (F) The peptides in (E) were subjected to an HLA-stabilizing assay. T2 cells were used as peptide-loading cells and their HLA-A∗02:01 expression was determined by FACS.

To confirm the specificity of scFv #17 for MAGE-A4 pMHC and evaluate the potential risk of cross-reactivity with self-peptides, we sought to determine the essential amino acid residues of the MAGE-A4p230-239 peptide (GVYDGREHTV) for the binding of scFv #17 to MAGE-A4 pMHC. The alanine substitution assay using the MAGE-A4p230-239 peptide sequence with alanine substituted at residues 1–10 (Table S1) revealed that the amino acid residues at positions 1–6 and 8 of the MAGE-A4p230-239 peptide were critical for the interaction of scFv #17 with MAGE-A4 pMHC (Figure 1C). We also observed that the third and fifth amino acids contribute for the MAGE-A4p230-239 peptide to bind HLA-A∗02:01 by an HLA-stabilizing assay (Figure 1D). Based on these results, we conducted an in silico search using the BLAST program blastp (http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi) to identify a 10-mer peptide containing the GVYDGRxHxx motif. Notably, no peptide containing this motif has been identified in the human proteome database. Therefore, we prepared 10 similar peptides with various half-maximum inhibitory concentrations (IC50; Table S2). As expected, eight of the 10 peptides belong to the MAGE family of antigens. As shown in Figure 1E, scFv #17 was unable to bind to T2 cells loaded with these similar peptides, although most of them potentially bind to HLA-A∗02:01 (Figure 1F). Notably, scFv #17 does not bind to T2 cells loaded with MAGE-A1 (EVYDGREHSA) or MAGE-C2 (GVYAGREHFV). In addition to high similarity to MAGE-A4p230-239 (GVYDGREHTV), MAGE-C2 (GVYAGREHFV) has been identified to bind to HLA-A∗02:01 by the IEDB MS-validated database. Collectively, these results indicate that scFv #17 has significantly low cross-reactivity to self-peptides.

MAGE CAR-T cells showed functional capacities in vitro

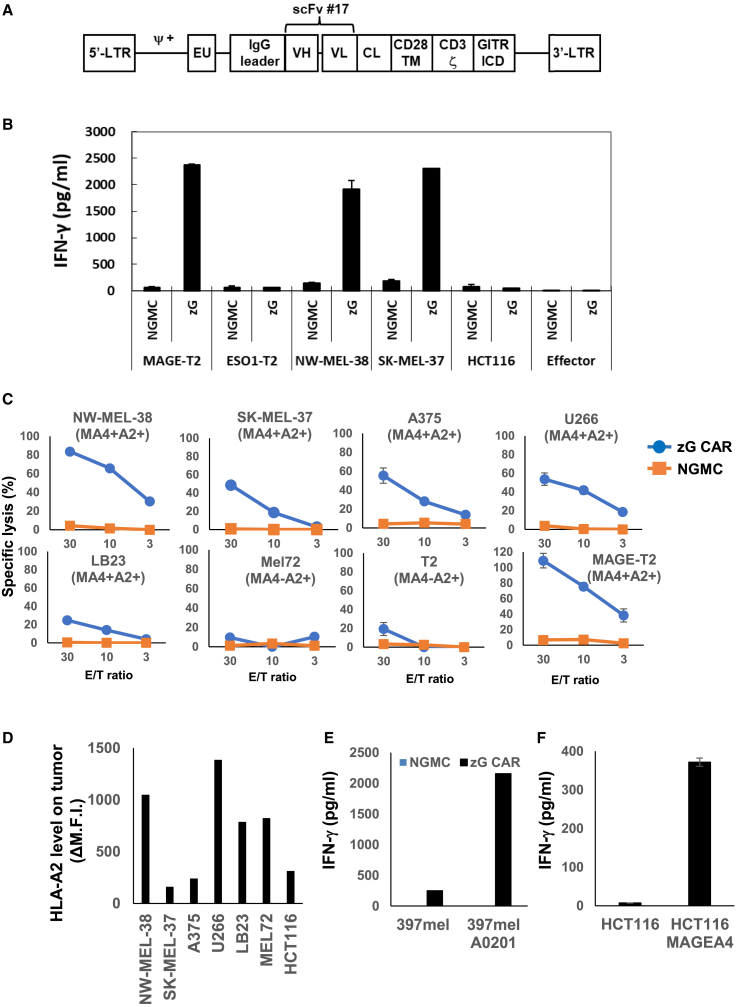

Next, we determined whether human T cells engineered to express the CAR using scFv #17 could recognize an endogenously derived MAGE-A4 peptide in the HLA-A∗02:01 context. To achieve this, we constructed a retroviral vector expressing the CAR fused with the GITR ICD (Figure 2A), as previously reported.10 Although we attempted to construct a retroviral vector with Gz.CAR containing GITR ICD upstream of CD3ζ, we observed minimal transduction efficacy. Consequently, we used zG.CAR with GITR ICD downstream of CD3ζ (see Figure S1 for the sequence).

Figure 2.

MAGE CAR-T cells show functional capacities in vitro

(A) Schematic representation of retroviral vectors encoding MAGE-A4p230-239/HLA-A∗02:01-specific CAR. The transgene contains the 5′ long terminal repeat (LTR) region, a packaging signal (Ψ), the IgG leader sequence region, the scFv (VH-VL sequence) derived from the MAGE A4-pMHC complex-specific monoclonal antibody #17, the CL region, the human CD28 transmembrane region (CD28 TM), human CD3ζ, the intracellular domain of human GITR (GITR ICD), and the 3′-LTR region. (B) IFN-γ production of MAGE CAR-T in response to the indicated tumor cell lines. Culture supernatants were harvested at 24 h and subjected to an IFN-γ ELISA in triplicate. Error bars represent the standard deviation (SD) of the mean. NGMC, mock-transduced T cells; MAGE-T2, T2 cells pulsed with MAGE-A4p230-239; ESO1-T2, T2 cells pulsed with NY-ESO-1p157-165. A representative result of three independent experiments is shown. (C) Cytotoxic activity of CAR+ T cells against the indicated tumor cell lines assessed by 2-h non-radioactive system in triplicate as described in section “materials and methods.” Error bars represent the SD of the mean. A representative result of three independent experiments is shown. (D) HLA-A2 expression on the indicated tumor cell lines. Values of net mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) were calculated by subtracting the MFI of cells stained by isotype control from that stained by anti-HLA-A2 monoclonal antibody (mAb). (E) Production of IFN-γ by zG CAR-T cells or NGMCs stimulated with 397mel or HLA-A∗02:01 transduced-397mel. Culture supernatants were harvested at 24 h and subjected to IFN-γ ELISA in triplicate. Error bars represent the SD of the mean. A representative result of three independent experiments is shown. (F) Production of IFN-γ by zG CAR-T cells or NGMCs stimulated with HCT116 or MAGE-A4 transduced-397mel. Error bars represent the SD of the mean. A representative result of three independent experiments is shown.

For the cytokine secretion assay, we used a panel of tumor cell lines as targets. As shown in Figure 2B, mock-transduced T cells with no genetic modifications (NGMCs) did not exhibit any reactivity against these tumor cell lines. In contrast, scFv #17 CAR-T (MAGE CAR-T) cells specifically produced interferon (IFN)-γ upon interaction with MAGE-A4+ HLA-A∗02:01+ tumor cell lines (NW-MEL-38 and SK-MEL-37) but not with HLA-A∗02:01+ tumor cell lines lacking MAGE-A4 (HCT-116 and T2 cells).

Based on these findings, MAGE CAR-T cells were used to further evaluate the cytotoxic function of MAGE-A4+ HLA-A∗02:01+ tumor cells. Figure 2C shows that MAGE CAR-T cells lysed MAGE-A4+ HLA-A∗02:01+ tumor cell lines (NW-MEL-38, SK-MEL-37, A375, U266, LB23) but not MAGE-A4− HLA-A∗02:01+ tumor cell line (Mel72). MAGE CAR-T cells also showed cytotoxic activity against SK-MEL-375 and A375 tumor cell lines, which have relatively low cell-surface expression of HLA-A∗02:01 (Figure 2D). We observed that cytotoxic activities of MAGE CAR-T cells against a variety of tumor cell lines at high E/T ratio could be detected at a relatively early time point. This observation might be explained by the usage of an antibody that has higher affinity than conventional TCRs. Furthermore, MAGE CAR-T cells became able to recognize 397mel (MAGE-A4+HLA-A∗02:01−) tumor cell line only after transduction with HLA-A∗02:01 (Figure 2E). Conversely, MAGE CAR-T cells became able to recognize HCT116 (MAGE-A4− HLA-A∗02:01+) tumor cell line only after transduction with MAGE-A4. Taken together, T cells engineered to express the CAR utilizing scFv #17 efficiently recognize the endogenously derived MAGE-A4 peptide in the context of HLA-A∗02:01.

GITR ICD confers superior in vivo efficacy on CAR-T cells targeting MAGE-A4 MHC

We proceeded to evaluate the therapeutic potential of MAGE zG.CAR-T cells using a xenograft model with immunodeficient NOD/Shi-scid/IL-2Rγnull (NOG) mice. These mice were bilaterally transplanted with NW-MEL-38 (MAGE-A4+ HLA-A∗02:01+) cells and HCT116 (MAGE-A4− HLA-A∗02:01+) cells. To this end, we constructed two other retroviral vectors expressing CARs sharing the same extracellular and transmembrane domains but different intracellular domains (28z., CD28 ICD with a CD3ζ; and 4-1BBz., 4-1BB ICD with a CD3ζ) (Figure 3A). We sorted and used each type of CD8+ CAR+ T cell derived from identical healthy donors to accurately compare in vivo efficacy (Figure 3B). Among the different types of CD8+ CAR+ T cells, the adoptive transfer of zG.CD8+ CAR+ T cells significantly suppressed the growth of NW-MEL-38 but not HCT116 tumors, indicating that zG.CAR-T cells exerted the most potent in vivo antitumor effect in an antigen-specific manner (Figure 3C). Furthermore, we observed that tumor tissues from mice treated with zG.CD8+ CAR+ T cells were heavily infiltrated with CAR-T cells, as determined by the measurement of CD8+ cells (Figure 3D). To explore the reasons for the superior in vivo functionality of zG CAR-T cells, cytokine secretion assays for assessing antigen sensitivities were performed on T2 cells pulsed with serially diluted MAGE-A4p230-239 peptide using CAR-T cells with three different ICDs. Although the obtained data showed that zG-type CARs tended to be able to recognize lower concentrations of peptide, the difference was not significant and seemed to be insufficient to explain the differences in vivo efficacies (Figure 3E).

Figure 3.

zG.CAR-T cells show superior in vivo function in suppressing tumor growth in a NOG mouse model

(A) Schematic representation of retroviral vectors encoding each type of MAGE-A4p230-239/HLA-A∗02:01-specific CAR. (B) Expression of CARs on human T cells. Cells were stained with phycoerythrin-labeled HLA-A∗02:01 tetramers presenting MAGE-A4p230-239 along with PE-cy7 anti-CD8 and APC anti-CD4. NGMCs served as background staining. (C) Schematic representation of the adoptive transfer experiment using NOG mice (upper). Growth curves of HCT116 and NW-MEL-38 tumors, and body weight of NOG mice (n = 3) transferred with CAR-T cells or NGMCs. Error bars represent the SD of the mean. ∗∗p < 0.01. Representative results from three independent experiments are shown. (D) Six days after intravenous injection of mock-transduced T cells (left) or zG.CD8+CAR+ T cells (right), NW-MEL-38 tumor tissues were harvested and subjected to immunohistochemical analysis. A representative result from two independent experiments is shown. (E) Production of IFN-γ by 28z, 4-1BBz, zG CAR-T cells, or NGMCs stimulated with T2 cells loaded with serially diluted MAGE peptide. Culture supernatants were harvested at 24 h and subjected to IFN-γ ELISA in triplicate. A representative result from two independent experiments is shown.

CD4+ CAR+ T cells attenuate the antitumor efficacy of CD8+ CAR+ T cells

Next, we investigated the antitumor efficacy of zG CARs, with and without CD4+ zG CARs, in NOG mice transplanted with NW-MEL-38 cells (MAGE-A4+ HLA-A∗02:01+) (Figure 4A). Adoptive transfer of CD8+ zG CAR+ T cells (5 × 106 cells) significantly suppressed NW-MEL-38 cell growth (Figure 4B). Mice injected with CD4+ zG CAR-T cells (5 × 106 cells) showed a slight decrease in tumor size, and the targeted cell killing effect was delayed compared to that of CD8+ zG CAR+ T cells. Notably, mice treated with a mixture of CD8+ zG CAR+ (5 × 106 cells) and CD4+ zG CAR+ (2 × 106 cells) T cells displayed an initial decrease in tumor size, but the effect was attenuated after day 10 (6 days after infusion). On day 5 (1 day after infusion), infiltrated CD4+ T cells were observed, but no CD8+ zG CAR+ T cells were detected in the tumor tissues (Figure 4C). On day 10, significant CD8+ T cell infiltration was observed in the tumor tissues of mice injected with CD8+ zG CAR-T cells, with a mean CD8+ cell count of 47%. Conversely, fewer CD8+ T cells infiltrated the tumor tissues in mice treated with CD8+ zG CAR+ and CD4+ zG CAR+ T cells, with a mean CD8+ cell count of 21% (Figure 4D). We also observed a proportional decrease in PD-L1 expression in tumor tissues as the degree of CD8+ infiltration decreased, which was considered to reflect a reduced antitumor immune response. These results may indicate that CD4+ zG CAR+ T cells infiltrate the tumor tissues more rapidly than CD8+ zG CAR+ T cells. It has been shown CAR regulatory T cells (Tregs) inadvertently generated during manufacture of CAR-T cell products affect efficacy in patients with large B cell lymphoma treated with either axicabtagene ciloleucel (axi-cel) or tisagenlecleucel (tisa-cel).31,32 In the former study, even 5% CAR-Tregs completely abrogated the efficacy of CAR-T cells in a mouse xenograft model. Therefore, it is possible that antitumor function of CD8+ zG CAR+ T cells was hampered by CAR-Tregs contaminated in CD4+ zG CAR+ T cell preparation (10.9% ± 2.3%) via suppression of infiltration and/or effector function of CD8+ zG CAR+ T cells.

Figure 4.

CD4+ zG.CAR+ T cells attenuate the antitumor efficacy of CD8+ zG.CAR+ T cells in a NOG mice model

(A) Schematic representation of the adoptive transfer experiment using NOG mice. (B) Tumor growth curves of NW-MEL-38 tumors of NOG mice (n = 4) treated with PBS and CARs. Error bars represent the SD of the mean. ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01. Representative results from three independent experiments are shown. (C) Immunofluorescence analysis of NW-MEL38 tumor tissues at day 5 and day 10 after tumor inoculation. (D) Immunofluorescence analysis using HALO (Indica Labs) at day10. Error bars represent the SD of the mean. ∗p < 0.05.

Lack of cross-reactivity of MAGE CAR-T cells to analogous peptides on HLA-A∗0201

Based on the functional capacity of MAGE CAR-T cells, we evaluated the potential risk of CAR-T cells against the self-peptide/HLA-A∗02:01 complex. Initially, we conducted IFN-γ ELISA to determine the reactivity of CAR-T cells to T2 cells pulsed with an array of alanine-substituted peptides analogous to the MAGE-A4p230-239 peptide, as described in Figure 1A. As expected, the amino acids at the same position were confirmed to be critical for recognition by MAGE CAR-T cells, which was consistent with the scFv #17 antibody (Figure S2). Moreover, MAGE CAR-T cells did not recognize the prepared analogous 10-mer peptides, indicating the high specificity of CAR-T cells for MAGE-A4 pMHC (Figure S2).

We performed an IFN-γ enzyme-linked immunosorbent spot (ELISPOT) assay to investigate the reactivity of CD8+ zG. CAR-T to T2 cells that were pulsed with an array of MAGE-A4p230-239 analogous peptides substituted at each position with all 20 amino acids. Our results showed that, at most, a few amino acid substitutions in the N-terminal contiguous six-amino acid sequence were permissive for CAR-T cell recognition by MAGE-A4 pMHC. We prepared all available human antigen-derived (8–10 mer) peptides containing permissive amino acid residues at positions 1–6 using the BLAST database (Table 1). The selected peptides are low binders to HLA-A∗02:01 as estimated by the IC50 value (Table 1) and confirmed by HLA-stabilizing assay (Figure 5B). Therefore, we were unable to identify any peptide recognized by MAGE CAR-T cells in the context of HLA-A∗02:01 (Figure 5C).

Table 1.

Peptides with permissible amino acids at the first to sixth position for recognition by zG.CD8+CAR+ T cells

| Gene name | Length (mer) | Peptide name | Sequence | IC50 (nM) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| G-protein signal modulator 1 | 10 | RISK1 | GVFDGRSRPR | 23,118.6 |

| 9 | RISK2 | GVFDGRSRP | 29,930.0 | |

| 8 | RISK3 | GVFDGRSR | 35,235.6 | |

| Splicing factor, arginine/serine-rich10 | 10 | RISK4 | GIYMGRPTYG | 21,870.4 |

| 9 | RISK5 | GIYMGRPTY | 22,106.1 | |

| 8 | RISK6 | GIYMGRPT | 30,357.6 | |

| Transformer 2 protein homolog alpha | 10 | RISK7 | GIYMGRPTHS | 21,114.4 |

| 9 | RISK8 | GIYMGRPTH | 34,897.9 | |

| 8 | Identical to RISK6 | GIYMGRPT | 30,357.6 | |

| Nectin-3 | 10 | RISK9 | GIFCYRRRRT | 26,657.2 |

| 9 | RISK10 | GIFCYRRRR | 23,524.1 | |

| 8 | RISK11 | GIFCYRRR | 33,582.2 | |

| GPI ethanolamine phosphate transferase 2 | 10 | RISK12 | GVYCYRAAIG | 15,406.6 |

| 9 | RISK13 | GVYCYRAAI | 789.1 | |

| 8 | RISK14 | GVYCYRAA | 19,714.0 | |

| Hyaluronan and proteoglycan link protein 4 | 10 | RISK15 | GVYCYRAPGA | 1,890.9 |

| 9 | RISK16 | GVYCYRAPG | 15,509.8 | |

| 8 | RISK17 | GVYCYRAP | 31,629.0 | |

| Hyaluronan and proteoglycan link protein 3 | 8 | RISK18 | GVYCYRQH | 39,397.2 |

| MAGE-A4 | 10 | GVYDGREHTV | 376.8 | |

| MAGE-A4 | 9 | GVYDGREHT | 12,268.7 | |

| MAGE-A4 | 8 | GVYDGREH | 40,916.5 | |

Figure 5.

Lack of cross-reactivity of MAGE CAR-T cells to analogous peptides on HLA-A∗0201

(A) Comprehensive amino acid substitution analysis identified amino acid residues that could be substituted at each position of the MAGE-A4p230-239 peptide sequence for recognition by CD8+ MAGE CAR-T cells. An IFN-γ ELISPOT assay was conducted to examine the reactivity of #17zG.CD8+CAR+ T cells to T2 cells pulsed sequentially with 200 peptides, comprising MAGE-A4p230-239 peptide substituted with all 20 amino acids. The percentage data shown in the heatmap in the upper column were calculated as follows: (experimental spot counts)/(spot counts of parental MAGE-A4p230-239). Permissible amino acid residues were defined (lower column) based on a 0.1 (10%) cutoff value. (B) The indicated peptides (see Table 1 for sequences) were subjected to an HLA-stabilizing assay to determine the capacity binding to HLA-A∗02:01. T2 cells were used as peptide-loading cells and their HLA-A∗02:01 expression was determined by FACS. (C) Validation of potential risk peptides derived from the human proteome by BLAST search. An IFN-γ ELISPOT assay was conducted to examine the reactivity of #17zG.CD8+CAR+ T cells to T2 cells pulsed with the indicated peptides in triplicate.

Collectively, the results obtained in this study indicate the strict specificity of CAR-T cells for MAGE-A4 pMHC.

Discussion

One of the major obstacles to the wider application of CAR-T cells in solid tumors is the limited number of cell-surface antigens specifically expressed on tumor cells.33 Although there are some exceptions, such as EGFRvIII and an activated form of integrin β7,34,35,36 the majority of tumor-specific antigens exist intracellularly and cannot be targeted by conventional CARs. One approach to circumvent this limitation involves the development of CARs utilizing scFv antibody that recognizes peptides in association with MHC class I and enables targeting a variety of intracellular tumor-specific antigens.37 In line with this approach, this study demonstrated that T cells modified by CAR, using an scFv antibody highly specific to MAGE-A4 pMHC, could be a promising treatment for solid tumors. An additional potential advantage of pMHC-targeted CAR-T therapy is that, like TCR-T therapy, post-transfer vaccination can activate and expand CAR-T cells in vivo,38,39 which may improve clinical efficacy, as previously reported.10 However, there is a potential risk of cross-reactivity between the pMHC-targeted CAR-T cells and self-peptides, which can lead to fatal toxicities.17 Particularly, caution is warranted when targeting antigens belonging to the MAGE family. This is because of the fatal on- and off-target toxicities reported in cases of MAGE-A1/A3-targeted TCR-T therapy utilizing affinity-enhanced TCRs.18,19

To address this issue, we investigated the reactivity of CAR-T cells to an array of peptides in addition to conventional alanine substitution analysis. We substituted each amino acid of the MAGE-A4p230-239 peptide for all 20 amino acids. Surprisingly, our results revealed that only a few amino acids could replace the six-amino acid sequence at the N terminus for recognition by MAGE-A4 pMHC-targeted CAR-T cells. The glycine (G) residue at the first position and the arginine (R) residue at the sixth position were extremely restricted and critical for this recognition (Figure 5A). In general, 9-mer-length peptides often bind to the groove formed by MHC class I. However, in the case of the 10-mer-length MAGE-A4p230-239 peptide, the R residue at the sixth position has been deduced to protrude out of the groove from the crystal structure.26 Considering the MAGE pMHC forming such a tight structure, the high specificity of CAR-T cells for MAGE-A4 pMHC may be partially explained. In addition, as the number of amino acid residues essential for recognition by CAR-T cells is as high as that required for recognition by TCR40 and double the number required for WT-1 pMHC-targeted CAR,10 we believe that the adoptive transfer of MAGE-A4 pMHC-targeted CAR-T cells could be a safe strategy. Nevertheless, our data do not exclude the possibility that CAR-T cells recognize unrelated peptides associated with unexpected HLA types.41,42 Therefore, the current Ph1 clinical trial for evaluating the safety and tolerability of this novel CAR-T cell therapy has been underway with careful step-by-step protocols, starting with the transfer of a small number of CAR-T cells.43

However, the wider application of CAR-T cell therapy for solid tumors faces another challenge imposed by the limited efficacy of CAR-T cells in the suppressive tumor microenvironment.44,45 Given that the physiological functions of CAR-T cells are directly defined by the cellular signaling delivered by the ICD of the CAR,46,47 the development of a CAR with an appropriate ICD could potentially confer superior in vivo efficacy of T cells against tumors. In this study, we focused on the GITR ICD to improve the efficacy of CAR-T cells, as the GITR/GITR ligand (GITRL) axis has been shown to play critical roles in exerting potent tumor immunity.48,49 As previously reported, GITR signaling not only activates the function of T cells, especially CD8+ T cells, but also renders them resistant to regulatory T cells in mouse models.48,50 Moreover, several groups have reported that GITR and TCR signaling can fully activate CD8+ T cells independent of CD28 signaling,51 which is presumed to be the target of the suppressive machinery through programmed death-1 (PD-1).52,53 Thus, CAR-T cells utilizing the GITR ICD could have another advantage in avoiding immunosuppressive mechanisms by regulatory T cells and the PD-1/PD-L1 axis at tumor sites.

We have demonstrated successful adoptive transfer of zG.CAR-T cells but not of CD28z.CAR-T cells or 4-1BBz. CAR-T cells, which significantly suppressed the growth of MAGE-A4+ HLA-A∗02:01+ tumor cells in an immunocompromised mouse model. In particular, there was a difference in the in vivo efficacy of zG.CAR-T cells and 4-1BBz. This finding is noteworthy as both GITR and 4-1BB belong to the TNFR superfamily (TNFRSF) and utilize a slightly different but similar TRAF signaling pathway.54,55 One possible explanation for this difference is that GITR signaling enhances T cell function, whereas 4-1BB signaling enhances T cell survival.46,47 Another possibility is that the optimal hinge domain (H) and transmembrane domain (TM) might be different between GITR ICD and 4-1BB ICD. Although we used Cλ H and CD28 TM in this study, it has been reported that the combination of CD28 H and CD28 TM is optimal for 4-1BB ICD.56 Further analysis is required to address this issue.

The other critical practical consideration is that the effectiveness of CAR-T therapy may be strongly influenced by factors such as the number and density of target molecules on the target cell surface, in addition to the ICD or the affinity of scFv.57 With a high number of target molecules, the GITR ICD may exhaust CAR-T cells and direct them toward the cell death pathway. Thus, the GITR ICD could potentially be more effective at targeting pMHC. However, this scenario remains speculative and requires further clarification through experimentation using different target antigens and CARs.

The adoptive transfer of CD4+ CAR-T cells attenuated the in vivo antitumor efficacy of CD8+ CAR+ T cells in a xenograft model. This unexpected result was noteworthy. One possible explanation is that CD4+ CAR-T cells recognize pMHC independently of CD8 molecules in in vitro assays (Figure S3), but the in vivo function of CD4+ CAR-T cells is low. Another possible explanation is that Tregs might attenuate the antitumor effect of CD8+ CAR-T cells.31,32 A certain frequency of foxp3-positive CD4+ CAR-T cells has been observed, and, therefore, the possibility that these cells exert an immunosuppressive effect locally in the tumor site cannot be excluded. Thus, a detailed evaluation of the actual immunosuppression by these cells is definitely needed, and further studies are required to obtain a definitive answer. In future clinical trials, we are considering the use of CAR constructs co-expressing the CD8 molecule or sorted CD8+ CAR+T cells to exclude these Treg cells.

In conclusion, the present results suggest that CAR-T cell therapy, which utilizes an antibody with high specificity for MAGE-A4 pMHC, may be effective for the treatment of patients with various types of solid tumors without associated risks. We believe that antibodies with such high specificity can be extended to other therapeutic methods, such as bispecific antibodies.

Materials and methods

Ethics statements

Written informed consent was obtained from healthy volunteers, in accordance with the guidelines set forth by the Declaration of Helsinki. The experimental protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Mie University School of Medicine (approval no. 3264).

All mice were housed under specific pathogen-free conditions and were used at 6–10 weeks of age. All animal experiments were conducted according to the protocols approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of the Mie University Life Science Center (approved no. 23-21).

Cell lines

MAGE-A4−/HLA-A∗02:01+, TAP-deficient transfected T2 cells, which can effectively load exogenous peptides, were used in combination with various cell lines, such as MAGE-A4+/HLA-A∗02:01+ melanoma cell lines NW-MEL-38 and SK-MEL-37, A375, myeloma cell line U266, sarcoma cell line LB23, MAGE-A4−/HLA-A∗02:01+ melanoma cell line Mel72, MAGE-A4+/HLA-A∗02:01− melanoma cell line 397mel, and MAGE-A4−/HLA-A∗02:01+ colon cancer cell line HCT116. All cell lines were cultured in Roswell Park Memorial Institute (RPMI)-1640 (WAKO) medium supplemented with 25 mM HEPES, 10% fetal calf serum (FCS; Biowest), 2 mM glutamine, 100 U/mL penicillin, and 100 μg/mL streptomycin.

Peptides

MAGE-A4p230-239 (GVYDGREHTV), CMVpp65-derived peptide (NLVPMVATV), Melan-Ap26-35 (ELAGIGILTV), Glypican-3p144-152 (FVGEFFTDV), NY-ESO-1p157-165 (SLLMWITQC), MAGE-A3p112-120 (KVAELVHFL), and all peptides prepared for the cross-reactivity assay were synthesized at a purity higher than 80% from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA, USA). All peptides were dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide at a concentration of 10 mM and subsequently stored in aliquots at −80°C prior to use.

Isolation of scFv reactive to the MAGE-A4p230-239/HLA-A∗02:01 complex

We chose the MAGE-A4p230-239/HLA-A∗02:01 complex as a target for screening scFv from an original human scFv phage display library (3.4 × 1012 colony-forming units). To exclude MHC-binding antibodies, we used HLA-A∗02:01 loaded with several HLA-A∗02:01-binding peptides derived from cytomegalovirus (CMV), Melan A, and NY-ESO-1 as competitors. The library solution was mixed with 120 μg of competitor tetramer, 100 μg of streptavidin (Pierce), 2% bovine serum albumin (BSA), and 20 μg of human IgG in 2 mL of 1% Triton X-100/phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), rotated at 4°C for 1 h, and then mixed with 10 μg MAGE-A4 tetramer-bound magnetic beads (Dynabeads MyOne, Invitrogen) at 4°C for 1 h. Magnetic beads were trapped by magnet-trapper (TOYOBO), washed with 1% Triton X-100/PBS several times, washed with PBS, and infected into Escherichia coli XL1-Blue (Invitrogen). Phage-infected E. coli was cultured in 2xYT medium with 200 μg/mL ampicillin at 37°C centigrade for 2 h and then spread on 2xYT agarose plate with 200 μg/mL ampicillin and 1% glucose (2xYTAG medium) at 37°C for around 15 h. After collecting with 2xYTAG medium, E. coli was cultured and infected with VCSM helper phage, incubated for 120 min at 37°C, kanamycin and isopropyl beta-D-1 thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) were added at a final concentration of 30 μg/mL and 0.5 mM, respectively, and it was cultured at 28°C for 20 h. Supernatant was collected by centrifugation, concentrated by PEG precipitation, and suspended with PBS. After screening three times, E. coli was spread onto 2xYTAG agarose plate. E. coli colony was picked up and cultured with LB medium with 0.5 mM IPTG at 30°C for 15 h, supernatant was collected by centrifugation, and antibody specificity was detected by ELISA. Briefly, 0.5 μg of Neutravidin was coated onto 96 well Maxisorp plate (NUNC), washed by PBS, and blocked with BSA. After immobilization of 100 ng of biotinylated MAGE-A4 tetramer onto the plate for 15 h at 4°C, the plate was washed with PBS. After that, 0.05% Tween PBS-diluted E. coli supernatant was added and incubated at 4°C for 20 h. After that, supernatant solution was discarded and the plate was washed with 0.05% Tween PBS, incubated with PBST-diluted anti-cp3 monoclonal antibody (MBL, special order) for 1 h, washed with PBST, incubated with HRP-conjugated anti-mouse IgG (MBL) for 1 h, washed with PBST, incubated with TMB solution (Thermo Fisher Scientific), and then stopped by 2% H2SO4. The 450-nm absorbance was measured by Spectromax M2 (Molecular Devices). Initially, we identified four independent positive clones that bound specifically to MAGE-A4 pMHC and investigated their inability to bind to irrelevant pMHCs (CMV, Glypican-3, Melan A, NY-ESO-1, and MAGE-A3/HLA-A∗02:01 complexes) (Figure 1A).

Surface plasmon resonance analysis

The kinetics and affinities of the scFv #17 antibody to MAGE-A4p230-239/HLA-A∗02:01 were analyzed by surface plasmon resonance using Biacore 3000 system (GE Healthcare). Biotinylated MAGE-A4p230-239/HLA-A∗02:01 was captured by a CAP sensor chip (GE Healthcare). Binding studies were performed at 25°C with varying concentrations of scFv #17 in the form fused with two domains of Fc-binding protein A, using a running buffer that contained 10 mM HEPES, 150 mM NaCl, 3 mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid, and 0.05% Surfactant P-20 (pH 7.4).58 The association and dissociation phase data were simultaneously fitted to a 1:1 model using the BIA evaluation 3.2 software (GE Healthcare).

scFv purification

The DNA fragment of scFv #17 was introduced into a His-FLAG expression vector and transformed into competent E. coli DH5a cells. The correct clone was selected through DNA sequencing. E. coli was cultured overnight at 30°C with shaking in 100 mL of 2× YT medium with 200 μg/mL ampicillin and 0.2 mM IPTG. The supernatant was collected by centrifugation and an equal volume of water-saturated ammonium sulfate was added. After centrifugation, the pellet was suspended in PBS with complete protease inhibitor (Roche). The sample was again centrifuged, and the resulting solution was applied to a Ni Sepharose Excel (GE Healthcare) column. The column was washed with 0.5 M NaCl in PBS and 20 mM imidazole and then eluted with 0.25 M imidazole and 0.5 M NaCl/PBS. After dialysis with PBS, the sample solution was quantified using sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and Coomassie staining. The sample was further purified using AKTA Prime Plus with an imidazole gradient.

scFv #17 binding assay

T2 cells were cultured in RPMI-1640 with 10% FCS. Next, 2 × 105 cells were suspended in RPMI-1640 with each peptide at a final concentration of 10 μM for 15 min at room temperature. Then, a 1/10 volume of FCS was added and incubated in a CO2 incubator at 37°C for 45 min. After washing with 10% FCS in RPMI-1640, the cells were stained with purified scFv at 5 g/mL for 1 h at room temperature. Subsequently, the cells were stained with an anti-DDDDK mouse monoclonal antibody for 1 h at room temperature and then with an Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated goat anti-mouse polyclonal antibody (Invitrogen) for 1 h at room temperature in the dark. Finally, the cells were washed with PBS containing 0.5% BSA and analyzed by flow cytometry using the FACSCalibur system (BD Biosciences).

Peptide binding assay

Peptide binding affinity to HLA-A∗02:01 was assessed by HLA stabilization assay as previously described59 using T2 cell line as a peptide-loading cell. Briefly, after incubation of the T2 cells in culture medium at 37°C for 24 h, cells were washed with plain RPMI with 2 mM glutamine, and suspended in 1 mL of X-Vivo15 (Lonza) in the presence or absence of a given peptide at 10 μM, followed by incubation at 37°C for 12 h. After washing with culture medium, stabilized HLA-A∗02:01 on the cell surface was determined by flow cytometry using Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated anti-HLA-A2 monoclonal antibodies (BB7.2 Bio-Rad). The mean fluorescence intensity was used as a surrogate for the binding affinity. Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated mouse IgG2b was used as an isotype control antibody.

Vector construction and preparation of virus solutions

The monoclonal antibody scFv #17 specific to the MAGE-A4p230-239/HLA-A∗02:01 complex in the VH-VL orientation, a Cλ hinge domain, and a CD28 transmembrane domain with either our novel construct of CD3ζ and GITR signaling domains, CD28 and CD3ζ signaling domains, or 4-1BB and CD3ζ signaling domains was inserted into a pMS3 retroviral vector (Takara Bio). After transduction with TransIT-293 (Mirus Bio) into G3T-hi cells (Takara Bio), cell culture supernatants were used to transduce PG13 cells (ATCC) to produce each GaLV-pseudotyped retrovirus.

To synthesize the single-chain MAGE-A4p230-239/HLA-A∗02:01 complex, the peptide was refolded with recombinant HLA-A∗02:01 and β2-microglobulin, followed by purification on a Superdex 200 10/300 GL column (GE Healthcare). The complex was then biotinylated using Bulk BirA (AVIDITY) and tetramerized using streptavidin-phycoerythrin (PROzyme). Immobilization was performed on either MyOne Streptavidin T1 Dynabeads (Invitrogen) or NeutrAvidin (Thermo Scientific)-coated MAXISORP NUNC-IMMUNO MODULE (Thermo Fisher Scientific).

In silico sequence analysis

In silico sequence analysis was performed using an amino acid scan using BLAST (NIH). After comparing the query and subject sequences, the subject sequence was subjected to MHC-1 Processing Prediction (IEDB) to predict the IC50 value.

T cell transduction

Human T cells expressing CAR specific to MAGE-A4 pMHC were prepared by retroviral transduction, as described previously.10 In brief, peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were stimulated with plate-coated anti-CD3 (5 μg/mL; OKT3, Janssen Pharmaceutica, Beerse, Belgium) and RetroNectin (25 μg/mL; Takara Bio). The PBMCs were cultured with GT-T551 (Takara Bio) supplemented with 600 IU/mL human recombinant IL-2 (Novartis), 0.2% human serum albumin (CLC Behring, USA), and 0.6% autologous human plasma. On days 4 and 5, these cells (mostly T cells) were transduced with the retroviral vector pMS3, containing CAR #17, using the RetroNectin-bound virus infection method. The retroviral solutions were preloaded onto RetroNectin (Takara Bio)-coated plates and centrifuged at 2,000 × g for 2 h at 32°C, followed by expansion culture. The cells were used for experiments on days 10–14. The MAGE-A4p230-239/HLA-A∗02:01 tetramer, along with anti-CD4 APC (RPA-T4) and anti-CD8 APC-Cy7 (RPA-T8) (both purchased from BioLegend), were used to detect CAR in CD4+/CD8+ T cells. In some experiments, CD8+CAR+ T cells were sorted on FACS Aria flow cytometer on day 7, expanded with LCLs (5 × 106), autologous PBMCs (2.5 × 107), IL-2 (100 IU/mL), and anti-CD3 (10 g/mL OKT3), and then used for experiments 10 days later. We preferentially produced CAR-T cells from HLA-A∗02:01-positive healthy individuals and used them in in vitro and in vivo assays.

Sorting of CD4+ and CD8+ CAR-T cells using flow cytometry

In several experiments, human CD4+CAR+ T cells and CD8+CAR+ T cells were isolated during days 7–9 using FACS Aria flow cytometer (BD Bioscience) and a prototype of the closed-cell isolation system developed by the Sony Group Corporation.60 The cultured cells were washed and resuspended in sorting buffer (PBS + 0.5% BSA). Then, APC-conjugated anti-CD4 antibody (TPA-T4; BioLegend), PE-Cy7-conjugated anti-CD8 antibody (RPA-T8; BioLegend), and PE-conjugated anti-lambda antibody (MHL-38; BioLegend) were added to the cell suspension, gently mixed, and incubated at 4°C for 60 min. After washing the cells, they were resuspended in sorting buffer, and the labeled cells were isolated using the previously mentioned cell sorters. The gates for CD4+CAR+ T cells and CD8+CAR+ T cells were set to include events based only on specific fluorescence signals that were tagged to each cell of interest. After isolating these cells, the purity of CD4+CAR+ T cells and CD8+CAR+ cells was >99%. The isolated cells were washed and resuspended in an expansion buffer (GT-T551; TaKaRa Bio) supplemented with 600 IU/mL human recombinant IL-2 (Novartis), 0.2% human serum albumin (CLC Behring, USA), and 0.6% autologous human plasma.

In vitro functional assay

Cytotoxicity was analyzed using standard chromium release assays, as described previously.24 In brief, 1 × 104 peptide-loaded T2 cells or various tumor cell lines labeled with 51Cr were plated in triplicate onto round-bottom 96-well plates in the presence of varying numbers of CAR-T cells (3 × 104 to 3 × 105 cells/0.2 mL per well) and incubated for 6 h. Control wells, which were used to determine spontaneous 51Cr release, contained only labeled target cells. The maximal release was determined by adding Triton X-100 (1%) to the target cells. The percentage-specific lysis was calculated according to the following formula: [(experimental 51Cr release – spontaneous 51Cr release)/(maximum 51Cr release – spontaneous 51Cr release)] × 100. In several experiments, we analyzed cytotoxicity of CAR-T cells using a non-radioactive assay system (Techno Suzuta), as described previously.61 In brief, 1 × 104 peptide-loaded T2 cells or various tumor cell lines labeled with bis(butyryloxymethyl) 4′-hydroxymethyl-2,2′:6′,2′′-terpyridine-6,6′′-dicarboxylate (BM-HT) were plated in triplicate onto round-bottom 96-well plates in the presence of varying numbers of CAR-T cells at effector-to-target ratios of 3, 10, and 30:1 for 2 h at 37°C with 5% CO2. After being centrifuged at 600 × g for 2 min at room temperature, the supernatants (25 μL each) were removed to a new round-bottom 96-well plate containing 250 μL of Eu3+ solution, from which 200-μL samples were transferred to a 96-well optical plate (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Time-resolved fluorometry (TRF) was measured through a TriStar2 LB942 multiplate reader (Berthold Technologies). All experiments were performed in triplicate. Specific lysis (%) was calculated as 100 × [experimental release (counts) – spontaneous release (counts)]/[maximum release (counts) – spontaneous release (counts)]. Cytokine production was analyzed using IFN-γ ELISA. CAR-T cells (1 × 105 cells/0.2 mL per well) were co-cultured with tumor cells (1 × 104 cells/0.2 mL well), and culture supernatants were harvested at 24 h and subjected to ELISA for checking IFN-γ levels.

In vivo antitumor activity

NOG mice (Central Institute for Experimental Animals, Kawasaki, Japan) were subcutaneously injected bilaterally with 2.5 × 106 NW-MEL-38 and HCT116 tumor cells. Four days later, the mice were intravenously injected with either 5 × 106 CAR-T cells or mock-transduced T cells. Tumor growth was monitored twice a week, and the tumor size was determined by measuring the mean length of two right-angled diameters using microcalipers. When the tumors reached a maximum diameter of 20 mm, the mice were humanely euthanized.

ELISPOT assay

The human IFN-γ ELISPOT assay was performed with some modifications, as previously described.62 ELISPOT plates (MAHA S4510; Millipore) were coated with an anti-human IFN-γ monoclonal antibody (1-D1K; Ptech). A total of 1 × 104 CD8+ zG CAR-T cells and 1 × 104 peptide-pulsed T2 cells were seeded in each well of the plate. After incubation for 22 h at 37°C, the plate was washed, supplemented with biotinylated capture antibody (7-B6-1, Mabtech), and incubated overnight at 4°C. After washing, the cells were treated with a streptavidin-alkaline phosphatase conjugate and stained using an alkaline phosphatase conjugate substrate kit (Bio-Rad). Finally, the spots were counted using an ELISPOT Plate Reader (ImmunoSpot, CTL-Europe).

Fluorescent immunohistochemistry

Frozen tumor specimens embedded in OCT compound (Sakura Finetech) were sectioned into 3-μm-thick sections, air-dried for 2 h, fixed with ice-cold acetone for 15 min, and subjected to immunohistochemistry. Subsequently, the tissue sections were washed three times with PBS and treated with a blocking solution (PBS supplemented with 1% BSA, 5% Blocking One Histo [Nacalai Tesque]) at 4°C for 30 min. Then, the tissue sections were incubated with fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated monoclonal antibody specific for CD8 (HIT8a; BD Biosciences) diluted with PBS supplemented with 1% BSA and 5% Blocking One Histo, for 1 h at room temperature in a humidified chamber. After washing thrice with PBS supplemented with 0.02% Tween 20, the slides were mounted in Prolong Gold antifade reagent with DAPI (Life Technologies) and observed by fluorescence microscopy (BX53F; Olympus; Tokyo, Japan).

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation, where error bars are shown. Statistical analyses were performed using unpaired two-tailed Student’s t tests using Microsoft Excel. The significance level was set at p < 0.05. All experiments were conducted more than twice, and representative results are shown.

Data and code availability

Data supporting this study are available from the corresponding author, Y.M., upon request.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Chisaki Amaike-Hyuga, Tae Hayashi, and Junko Nakamura for technical assistance. This research was partly supported by the Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development (AMED) under grant numbers JP19ck0106412 and JP21ck0106658.

Author contributions

L.W., Y.A., K.S., N.S., N.J., and Y.M. designed and performed the experiments, analyzed the results, and prepared the figures. M.M. and Y.K. provided a prototype of the closed-cell isolation system. K.T. provided advice for the experiments. Y.M. and H.S. conceived the study, interpreted the data, and supervised the work. Y.M. wrote the paper.

Declaration of interests

M.M. and Y.K. are employees of Sony Group Corporation, which collaborated in the development of a closed-cell isolation system. The Department of Personalized Cancer Immunotherapy, Mie University Graduate School of Medicine, is an endowment department supported by a grant from T cell Nouveau.

Footnotes

Supplemental information can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ymthe.2024.01.018.

Contributor Information

Yoshihiro Miyahara, Email: miyahr-y@med.mie-u.ac.jp.

Hiroshi Shiku, Email: shiku@med.mie-u.ac.jp.

Supplemental information

References

- 1.Kalos M., Levine B.L., Porter D.L., Katz S., Grupp S.A., Bagg A., June C.H. T cells with chimeric antigen receptors have potent antitumor effects and can establish memory in patients with advanced leukemia. Sci. Transl. Med. 2011;3:95ra73. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3002842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Davila M.L., Riviere I., Wang X., Bartido S., Park J., Curran K., Chung S.S., Stefanski J., Borquez-Ojeda O., Olszewska M., et al. Efficacy and toxicity management of 19-28z CAR T cell therapy in B cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Sci. Transl. Med. 2014;6:224ra25. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3008226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Maude S.L., Frey N., Shaw P.A., Aplenc R., Barrett D.M., Bunin N.J., Chew A., Gonzalez V.E., Zheng Z., Lacey S.F., et al. Chimeric antigen receptor T cells for sustained remissions in leukemia. N. Engl. J. Med. 2014;371:1507–1517. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1407222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schmidts A., Maus M.V. Making CAR T cells a solid option for solid tumors. Front. Immunol. 2018;9:2593. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.02593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Del Bufalo F., De Angelis B., Caruana I., Del Baldo G., De Ioris M.A., Serra A., Mastronuzzi A., Cefalo M.G., Pagliara D., Amicucci M., et al. GD2-CART01 for Relapsed or Refractory High-Risk Neuroblastoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2023;388:1284–1295. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2210859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Andersen P.S., Stryhn A., Hansen B.E., Fugger L., Engberg J., Buus S. A recombinant antibody with the antigen-specific, major histocompatibility complex-restricted specificity of T cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1996;93:1820–1824. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.5.1820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chames P., Hufton S.E., Coulie P.G., Uchanska-Ziegler B., Hoogenboom H.R. Direct selection of a human antibody fragment directed against the tumor T-cell epitope HLA-A1–MAGE-A1 from a nonimmunized phage-Fab library. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2000;97:7969–7974. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.14.7969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Willemsen R.A., Debets R., Hart E., Hoogenboom H.R., Bolhuis R.L., Chames P. A phage display selected fab fragment with MHC class I-restricted specificity for MAGE-A1 allows for retargeting of primary human T lymphocytes. Gene Ther. 2001;8:1601–1608. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3301570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chames P., Willemsen R.A., Rojas G., Dieckmann D., Rem L., Schuler G., Bolhuis R.L., Hoogenboom H.R. TCR-like human antibodies expressed on human CTLs mediate antibody affinity-dependent cytolytic activity. J. Immunol. 2002;169:1110–1118. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.2.1110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Akahori Y., Wang L., Yoneyama M., Seo N., Okumura S., Miyahara Y., Amaishi Y., Okamoto S., Mineno J., Ikeda H., et al. Antitumor activity of CAR-T cells targeting the intracellular oncoprotein WT1 can be enhanced by vaccination. Blood. 2018;132:1134–1145. doi: 10.1182/blood-2017-08-802926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Held G., Matsuo M., Epel M., Gnjatic S., Ritter G., Lee S.Y., Tai T.Y., Cohen C.J., Old L.J., Pfreundschuh M., et al. Dissecting cytotoxic T cell responses towards the NY-ESO-1 protein by peptide/MHC-specific antibody fragments. Eur. J. Immunol. 2004;34:2919–2929. doi: 10.1002/eji.200425297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stewart-Jones G., Wadle A., Hombach A., Shenderov E., Held G., Fischer E., Kleber S., Nuber N., Stenner-Liewen F., Bauer S., et al. Rational development of high-affinity T-cell receptor-like antibodies. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2009;106:5784–5788. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0901425106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dao T., Yan S., Veomett N., Pankov D., Zhou L., Korontsvit T., Scott A., Whitten J., Maslak P., Casey E., et al. Targeting the intracellular WT1 oncogene product with a therapeutic human antibody. Sci. Transl. Med. 2013;5:176ra33. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3005661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhao Q., Ahmed M., Tassev D.V., Hasan A., Kuo T.Y., Guo H.F., O'Reilly R.J., Cheung N.K.V. Affinity maturation of T-cell receptor-like antibodies for Wilms tumor 1 peptide greatly enhances therapeutic potential. Leukemia. 2015;29:2238–2247. doi: 10.1038/leu.2015.125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ma Q., Garber H.R., Lu S., He H., Tallis E., Ding X., Sergeeva A., Wood M.S., Dotti G., Salvado B., et al. A novel TCR-like CAR with specificity for PR1/HLA-A2 effectively targets myeloid leukemia in vitro when expressed in human adult peripheral blood and cord blood T cells. Cytotherapy. 2016;18:985–994. doi: 10.1016/j.jcyt.2016.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Douglass J., Hsiue E.H.C., Mog B.J., Hwang M.S., DiNapoli S.R., Pearlman A.H., Miller M.S., Wright K.M., Azurmendi P.A., Wang Q., et al. Bispecific antibodies targeting mutant RAS neoantigens. Sci. Immunol. 2021;6:abd5515. doi: 10.1126/sciimmunol.abd5515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kurosawa N., Midorikawa A., Ida K., Fudaba Y.W., Isobe M. Development of a T-cell receptor mimic antibody targeting a novel Wilms tumor 1-derived peptide and analysis of its specificity. Cancer Sci. 2020;111:3516–3526. doi: 10.1111/cas.14602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Linette G.P., Stadtmauer E.A., Maus M.V., Rapoport A.P., Levine B.L., Emery L., Litzky L., Bagg A., Carreno B.M., Cimino P.J., et al. Cardiovascular toxicity and titin cross-reactivity of affinity-enhanced T cells in myeloma and melanoma. Blood. 2013;122:863–871. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-03-490565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Morgan R.A., Chinnasamy N., Abate-Daga D., Gros A., Robbins P.F., Zheng Z., Dudley M.E., Feldman S.A., Yang J.C., Sherry R.M., et al. Cancer regression and neurological toxicity following anti-MAGE-A3 TCR gene therapy. J. Immunother. 2013;36:133–151. doi: 10.1097/CJI.0b013e3182829903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.De Plaen E., Arden K., Traversari C., Gaforio J.J., Szikora J.P., De Smet C., Brasseur F., van der Bruggen P., Lethé B., Lurquin C., et al. Structure, chromosomal localization, and expression of 12 genes of the MAGE family. Immunogenetics. 1994;40:360–369. doi: 10.1007/BF01246677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yakirevich E., Sabo E., Lavie O., Mazareb S., Spagnoli G.C., Resnick M.B. Expression of the MAGE-A4 and NY-ESO-1 cancer-testis antigens in serous ovarian neoplasms. Clin. Cancer Res. 2003;9:6453–6460. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang Y., Stroobant V., Russo V., Boon T., Van der Bruggen P. A MAGE-A4 peptide presented by HLA-B37 is recognized on human tumors by cytolytic T lymphocytes. Tissue Antigens. 2002;60:365–371. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-0039.2002.600503.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kobayashi T., Lonchay C., Colau D., Demotte N., Boon T., van der Bruggen P. New MAGE-4 antigenic peptide recognized by cytolytic T lymphocytes on HLA-A1 tumor cells. Tissue Antigens. 2003;62:426–432. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-0039.2003.00123.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Miyahara Y., Naota H., Wang L., Hiasa A., Goto M., Watanabe M., Kitano S., Okumura S., Takemitsu T., Yuta A., et al. Determination of cellularly processed HLA-A2402-restricted novel CTL epitopes derived from two cancer germ line genes, MAGE-A4 and SAGE. Clin. Cancer Res. 2005;11:5581–5589. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-2585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Duffour M.T., Chaux P., Lurquin C., Cornelis G., Boon T., van der Bruggen P. A MAGE-A4 peptide presented by HLA-A2 is recognized by cytolytic T lymphocytes. Eur. J. Immunol. 1999;29:3329–3337. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4141(199910)29:10<3329::AID-IMMU3329>3.0.CO;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hillig R.C., Coulie P.G., Stroobant V., Saenger W., Ziegler A., Hülsmeyer M. High-resolution structure of HLA-A∗0201 in complex with a tumour-specific antigenic peptide encoded by the MAGE-A4 gene. J. Mol. Biol. 2001;310:1167–1176. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.4816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Davari K., Holland T., Prassmayer L., Longinotti G., Ganley K.P., Pechilis L.J., Diaconu I., Nambiar P.R., Magee M.S., Schendel D.J., et al. Development of a CD8 co-receptor independent T-cell receptor specific for tumor-associated antigen MAGE-A4 for next generation T-cell-based immunotherapy. J. Immunother. Cancer. 2021;9 doi: 10.1136/jitc-2020-002035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hong D.S., Van Tine B.A., Biswas S., McAlpine C., Johnson M.L., Olszanski A.J., Clarke J.M., Araujo D., Blumenschein G.R., Jr., Kebriaei P., et al. Autologous T cell therapy for MAGE-A4+ solid cancers in HLA-a∗02+ patients: a phase 1 trial. Nat. Med. 2023;29:104–114. doi: 10.1038/s41591-022-02128-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Suvas S., Kim B., Sarangi P.P., Tone M., Waldmann H., Rouse B.T. In vivo kinetics of GITR and GITR ligand expression and their functional significance in regulating viral immunopathology. J. Virol. 2005;79:11935–11942. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.18.11935-11942.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Knee D.A., Hewes B., Brogdon J.L. Rationale for anti-GITR cancer immunotherapy. Eur. J. Cancer. 2016;67:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2016.06.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Haradhvala N.J., Leick M.B., Maurer K., Gohil S.H., Larson R.C., Yao N., Gallagher K.M.E., Katsis K., Frigault M.J., Southard J., et al. Distinct cellular dynamics associated with response to CAR-T therapy for refractory B cell lymphoma. Nat. Med. 2022;28:1848–1859. doi: 10.1038/s41591-022-01959-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Good Z., Spiegel J.Y., Sahaf B., Malipatlolla M.B., Ehlinger Z.J., Kurra S., Desai M.H., Reynolds W.D., Wong Lin A., Vandris P., et al. Post-infusion CAR T(Reg) cells identify patients resistant to CD19-CAR therapy. Nat. Med. 2022;28:1860–1871. doi: 10.1038/s41591-022-01960-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hinrichs C.S., Restifo N.P. Reassessing target antigens for adoptive T-cell therapy. Nat. Biotechnol. 2013;31:999–1008. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sampson J.H., Choi B.D., Sanchez-Perez L., Suryadevara C.M., Snyder D.J., Flores C.T., Schmittling R.J., Nair S.K., Reap E.A., Norberg P.K., et al. EGFRvIII mCAR-modified T-cell therapy cures mice with established intracerebral glioma and generates host immunity against tumor-antigen loss. Clin. Cancer Res. 2014;20:972–984. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-0709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Goff S.L., Morgan R.A., Yang J.C., Sherry R.M., Robbins P.F., Restifo N.P., Feldman S.A., Lu Y.C., Lu L., Zheng Z., et al. Pilot trial of adoptive transfer of chimeric antigen receptor–transduced T cells targeting EGFRvIII in patients with glioblastoma. J. Immunother. 2019;42:126–135. doi: 10.1097/CJI.0000000000000260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hosen N., Matsunaga Y., Hasegawa K., Matsuno H., Nakamura Y., Makita M., Watanabe K., Yoshida M., Satoh K., Morimoto S., et al. The activated conformation of integrin β 7 is a novel multiple myeloma–specific target for CAR T cell therapy. Nat. Med. 2017;23:1436–1443. doi: 10.1038/nm.4431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dahan R., Reiter Y. T-cell-receptor-like antibodies–generation, function and applications. Expert Rev. Mol. Med. 2012;14:E6. doi: 10.1017/erm.2012.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chodon T., Comin-Anduix B., Chmielowski B., Koya R.C., Wu Z., Auerbach M., Ng C., Avramis E., Seja E., Villanueva A., et al. Adoptive transfer of MART-1 T-cell receptor transgenic lymphocytes and dendritic cell vaccination in patients with metastatic melanoma. Clin. Cancer Res. 2014;20:2457–2465. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-3017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Poschke I., Lövgren T., Adamson L., Nyström M., Andersson E., Hansson J., Tell R., Masucci G.V., Kiessling R. A phase I clinical trial combining dendritic cell vaccination with adoptive T cell transfer in patients with stage IV melanoma. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 2014;63:1061–1071. doi: 10.1007/s00262-014-1575-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hennecke J., Wiley D.C. T cell receptor–MHC interactions up close. Cell. 2001;104:1–4. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00185-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yarmarkovich M., Marshall Q.F., Warrington J.M., Premaratne R., Farrel A., Groff D., Li W., di Marco M., Runbeck E., Truong H., et al. Cross-HLA targeting of intracellular oncoproteins with peptide-centric CARs. Nature. 2021;599:477–484. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-04061-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 42.Lai J., Choo J.A.L., Tan W.J., Too C.T., Oo M.Z., Suter M.A., Mustafa F.B., Srinivasan N., Chan C.E.Z., Lim A.G.X., et al. TCR–like antibodies mediate complement and antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity against Epstein-Barr virus–transformed B lymphoblastoid cells expressing different HLA-A∗02 microvariants. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:9923. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-10265-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Okumura S., Ishihara M., Kiyota N., Yakushijin K., Takada K., Kobayashi S., Ikeda H., Endo M., Kato K., Kitano S., et al. Chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy targeting a MAGE A4 peptide and HLA-A∗02:01 complex for unresectable advanced or recurrent solid cancer: protocol for a multi-institutional phase 1 clinical trial. BMJ Open. 2022;12 doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2022-065109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kakarla S., Gottschalk S. CAR T cells for solid tumors: armed and ready to go? Cancer J. 2014;20:151–155. doi: 10.1097/PPO.0000000000000032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Martinez M., Moon E.K. CAR T cells for solid tumors: new strategies for finding, infiltrating, and surviving in the tumor microenvironment. Front. Immunol. 2019;10:128. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.00128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kawalekar O.U., O'Connor R.S., Fraietta J.A., Guo L., McGettigan S.E., Posey A.D., Jr., Patel P.R., Guedan S., Scholler J., Keith B., et al. Distinct signaling of coreceptors regulates specific metabolism pathways and impacts memory development in CAR T cells. Immunity. 2016;44:380–390. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2016.01.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Li G., Boucher J.C., Kotani H., Park K., Zhang Y., Shrestha B., Wang X., Guan L., Beatty N., Abate-Daga D., Davila M.L. 4-1BB enhancement of CAR T function requires NF-κB and TRAFs. JCI Insight. 2018;3 doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.121322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nishikawa H., Kato T., Hirayama M., Orito Y., Sato E., Harada N., Gnjatic S., Old L.J., Shiku H. Regulatory T cell–resistant CD8+ T cells induced by glucocorticoid-induced tumor necrosis factor receptor signaling. Cancer Res. 2008;68:5948–5954. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-5839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Imai N., Ikeda H., Tawara I., Wang L., Wang L., Nishikawa H., Kato T., Shiku H. Glucocorticoid-induced tumor necrosis factor receptor stimulation enhances the multifunctionality of adoptively transferred tumor antigen-specific CD8+ T cells with tumor regression. Cancer Sci. 2009;100:1317–1325. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2009.01179.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Stephens G.L., McHugh R.S., Whitters M.J., Young D.A., Luxenberg D., Carreno B.M., Collins M., Shevach E.M. Engagement of glucocorticoid-induced TNFR family-related receptor on effector T cells by its ligand mediates resistance to suppression by CD4+ CD25+ T cells. J. Immunol. 2004;173:5008–5020. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.8.5008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ronchetti S., Nocentini G., Bianchini R., Krausz L.T., Migliorati G., Riccardi C. Glucocorticoid-induced TNFR-related protein lowers the threshold of CD28 costimulation in CD8+ T cells. J. Immunol. 2007;179:5916–5926. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.9.5916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hui E., Cheung J., Zhu J., Su X., Taylor M.J., Wallweber H.A., Sasmal D.K., Huang J., Kim J.M., Mellman I., Vale R.D. T cell costimulatory receptor CD28 is a primary target for PD-1–mediated inhibition. Science. 2017;355:1428–1433. doi: 10.1126/science.aaf1292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kamphorst A.O., Wieland A., Nasti T., Yang S., Zhang R., Barber D.L., Konieczny B.T., Daugherty C.Z., Koenig L., Yu K., et al. Rescue of exhausted CD8 T cells by PD-1–targeted therapies is CD28-dependent. Science. 2017;355:1423–1427. doi: 10.1126/science.aaf0683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Snell L.M., Lin G.H.Y., McPherson A.J., Moraes T.J., Watts T.H. T-cell intrinsic effects of GITR and 4-1BB during viral infection and cancer immunotherapy. Immunol. Rev. 2011;244:197–217. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2011.01063.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ward-Kavanagh L.K., Lin W.W., Šedý J.R., Ware C.F. The TNF receptor superfamily in co-stimulating and co-inhibitory responses. Immunity. 2016;44:1005–1019. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2016.04.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Majzner R.G., Rietberg S.P., Sotillo E., Dong R., Vachharajani V.T., Labanieh L., Myklebust J.H., Kadapakkam M., Weber E.W., Tousley A.M., et al. Tuning the Antigen Density Requirement for CAR T-cell Activity. Cancer Discov. 2020;10:702–723. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-19-0945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hudecek M., Lupo-Stanghellini M.T., Kosasih P.L., Sommermeyer D., Jensen M.C., Rader C., Riddell S.R. Receptor affinity and extracellular domain modifications affect tumor recognition by ROR1-specific chimeric antigen receptor T cells. Clin. Cancer Res. 2013;19:3153–3164. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-0330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ito W., Kurosawa Y. Development of an artificial antibody system with multiple valency using an Fv fragment fused to a fragment of protein A. J. Biol. Chem. 1993;268:20668–20675. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Nijman H.W., Houbiers J.G., Vierboom M.P., van der Burg S.H., Drijfhout J.W., D'Amaro J., Kenemans P., Melief C.J., Kast W.M. Identification of peptide sequences that potentially trigger HLA-A2.1-restricted cytotoxic T lymphocytes. Eur. J. Immunol. 1993;23:1215–1219. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830230603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Matsumoto M., Tashiro S., Ito T., Takahashi K., Hashimoto G., Kajihara J., Miyahara Y., Shiku H., Katsumoto Y. Fully closed cell sorter for immune cell therapy manufacturing. Mol. Ther. Methods Clin. Dev. 2023;30:367–376. doi: 10.1016/j.omtm.2023.07.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Tagod M.S.O., Mizuta S., Sakai Y., Iwasaki M., Shiraishi K., Senju H., Mukae H., Morita C.T., Tanaka Y. Determination of human γδ T cell–mediated cytotoxicity using a non-radioactive assay system. J. Immunol. Methods. 2019;466:32–40. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2019.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Power C.A., Grand C.L., Ismail N., Peters N.C., Yurkowski D.P., Bretscher P.A. A valid ELISPOT assay for enumeration of ex vivo, antigen-specific, IFNγ-producing T cells. J. Immunol. Methods. 1999;227:99–107. doi: 10.1016/s0022-1759(99)00074-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data supporting this study are available from the corresponding author, Y.M., upon request.