Abstract

Biological databases serve as a global fundamental infrastructure for the worldwide scientific community, which dramatically aid the transformation of big data into knowledge discovery and drive significant innovations in a wide range of research fields. Given the rapid data production, biological databases continue to increase in size and importance. To build a catalog of worldwide biological databases, we curate a total of 5825 biological databases from 8931 publications, which are geographically distributed in 72 countries/regions and developed by 1975 institutions (as of September 20, 2022). We further devise a z-index, a novel index to characterize the scientific impact of a database, and rank all these biological databases as well as their hosting institutions and countries in terms of citation and z-index. Consequently, we present a series of statistics and trends of worldwide biological databases, yielding a global perspective to better understand their status and impact for life and health sciences. An up-to-date catalog of worldwide biological databases, as well as their curated meta-information and derived statistics, is publicly available at Database Commons (https://ngdc.cncb.ac.cn/databasecommons/).

Keywords: Biological database, Catalog, Database Commons, Citation, z-index

Introduction

Biological data powered by high-throughput sequencing technologies are generated at explosive rates and scales, causing a bottleneck shift from data production to data management. Consequently, there is an ever-increasing number of biological databases that archive, integrate, and share different types of biological data often with value-added curation [1], [2], [3]. In the big data era, biological databases enable handling the data deluge and serve as a global fundamental infrastructure for the worldwide scientific community [4], dramatically increasing the pace to transform big data into knowledge discovery and driving significant innovations in life, medicine, and health sciences.

As biological databases continue to increase in size and importance, it is yet unknown how many biological databases exist in the world, which institutions and countries are heavily involved, and what their impact on biomedical research is. Toward this end, here we present Database Commons (https://ngdc.cncb.ac.cn/databasecommons/), a curated catalog of worldwide biological databases spanning diverse species, encompassing various data, and developed/maintained by different institutions in different countries. Unlike previous efforts made in the past several years (Table S1), Database Commons features a comprehensive and systematic catalog of biological databases by curating a wealth of database meta-information from publications. In addition, it provides multiple assessments to characterize the scientific impact of a database and accordingly yields a series of useful statistics and trends of biological databases at the global scale.

Database construction

Data curation

The catalog of worldwide biological databases was constructed based on literature search & curation. Specifically, database-related publications were first obtained from PubMed through keyword search via National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) E-utilities and then checked and validated by dedicated curators. Database meta-information was manually extracted from its associated publication(s), including short name, full name, URL, species, hosted institution, and country. All the meta-information for each database has been curated and reviewed by multiple curators.

Citation and z-index calculation

As one database may have multiple publications, database citation was calculated as the total citation summed over all its associated publication(s), where the citation was automatically obtained via Europe PMC at European Bioinformatics Institute (EBI). Moreover, the z-index was calculated by dividing database citation by database age as shown below:

| (1) |

where database age was estimated since the year of its first publication, and n represents the number of total associated publications of the database.

Database content

Distribution of global biological databases in terms of database count

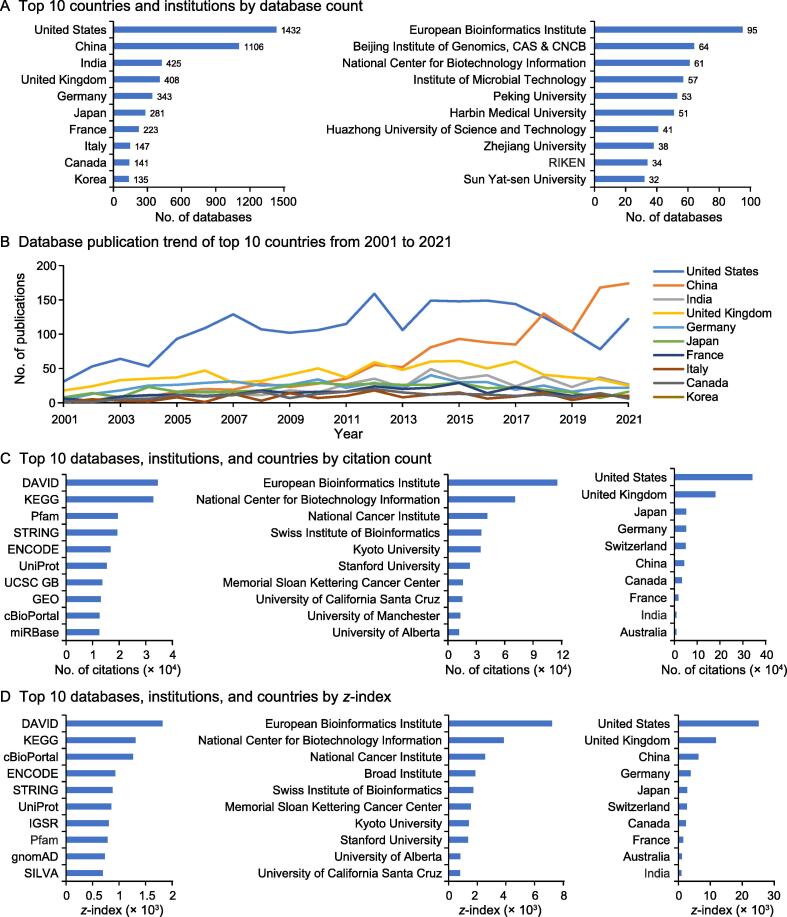

Totally, we catalog 5825 biological databases geographically distributed in 72 countries/regions, which are manually curated from more than 8900 publications (as of September 20, 2022). In terms of database count, the United States (US), China, India, and United Kingdom (UK) host 1432, 1106, 425, and 408 biological databases, respectively, together accounting for ∼ 58% of all global databases, followed by Germany, Japan, France, Italy, Canada, and Korea (Figure 1A). In these databases, not surprisingly, human, mouse, Arabidopsis thaliana, fruit fly, Saccharomyces cerevisiae, rice, Escherichia coli, rat, nematode, and zebrafish are the top 10 species. We also identify 1975 institutions worldwide that host multiple databases. The EBI [5], Beijing Institute of Genomics, Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS) & China National Center for Bioinformation (CNCB) [6], and NCBI [7], host the most databases with 95, 64, and 61, respectively, and together with Institute of Microbial Technology, Peking University, Harbin Medical University, Huazhong University of Science and Technology, Zhejiang University, RIKEN, and Sun Yat-sen University, make up the top 10 institutions (Figure 1A).

Figure 1.

The landscape of worldwide biological databases

A. Top 10 countries and institutions by database count. B. Database publication trend of top 10 countries from 2001 to 2021. C. Top 10 databases, institutions, and countries by citation count. D. Top 10 databases, institutions, and countries by z-index. All statistics were obtained from Database Commons as of September 20, 2022, which is publicly available at https://ngdc.cncb.ac.cn/databasecommons/ with frequent updates by expert curation and community submission. CAS, Chinese Academy of Sciences; cBioPortal, cBio cancer genomics portal; CNCB, China National Center for Bioinformation; DAVID, Database for Annotation, Visualization and Integrated Discovery; ENCODE, Encyclopedia of DNA Elements; GEO, Gene Expression Omnibus; gnomAD, Genome Aggregation Database; IGSR, International Genome Sample Resource; KEGG, Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes; UCSC GB, UCSC Genome Browser; UniProt, Universal Protein Resource.

Database publication trend from 2001 to 2021

When tracking the publication trend over a 20-year time frame, the number of database publications increases from 97 in 2001 to 588 in 2021. Consistently, the US, China, and UK are world-leading countries, with 2433, 1291, and 923 database publications over the past 20 years, where China started to surpass the other countries in publication count since 2019 (Figure 1B), correlating well with increasing funding investment in scientific data management as well as the establishment of CNCB in 2019.

Distribution of global biological databases in terms of citation count and z-index

As each database is curated from publication, database citation is summed over all associated publication(s). According to database citation, Database for Annotation, Visualization and Integrated Discovery (DAVID), Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG), and Pfam are ranked as the most highly cited databases (Figure 1C), conforming well with their popularity acknowledged by the global scientific community. Likewise, institutions/countries are ranked based on total citations summed over their associated databases. EBI, NCBI, National Cancer Institute (NCI), Swiss Institute of Bioinformatics (SIB) [8], and Kyoto University are leading institutions, and consistently, the US, UK, Japan, Germany, and Switzerland are leading nations in terms of citation, in agreement with their long-term investment in biological data management.

Since old databases tend to accumulate more citations than young databases, to normalize the age difference, we propose a z-index, a novel index to assess the database impact by factoring both citation and age, viz., z-index = citation/age, which is defined as the average number of citations per annum. Again, DAVID and KEGG top the ranking, and strikingly, cBioPortal is ranked 3rd by z-index but 9th by citation, along with International Genome Sample Resource (IGSR), Genome Aggregation Database (gnomAD), and SILVA that are emerged in the z-index-based top 10 list (Figure 1D), indicating that z-index reduces the influence of database age and enables relatively fair comparison among databases with different ages. Noticeably, EBI, NCBI, NCI, Broad Institute, and SIB top the ranking in terms of z-index; Broad Institute is present in the z-index-based top 10 list yet absent in the citation-based list, which is primarily contributed by its young highly-cited databases [e.g., Genotype-Tissue Expression (GTEx)]. Additionally, the top 10 countries are consistent in both z-index and citation; China ranks 3rd by z-index and 6th by citation, principally owing to several young databases becoming increasingly popular in recent years.

Discussion

There are, however, several caveats that should be borne in mind. First, it is improper to use z-index or citation to evaluate those databases that have no associated publication or are widely used, highly accessed yet often failed to be properly cited (e.g., GenBank and PubMed). Second, it might be inappropriate to calculate the database age since the year of its first publication, albeit rough yet relatively fair to all databases. Third, it would be unfair to assign a single hosted institution/country for databases that are collaboratively developed and/or maintained by multiple institutions across countries. Meanwhile, it should be noted that biological databases are threatened by funding cuts [9] and over time some of them become inaccessible due to various reasons [10]. Considering that different research areas have different numbers of researchers and citations, biological databases in non-mainstream areas would not achieve the high z-index values as those in highly topical areas, so that high z-index indicates broad impact, whereas the converse is not always true. Therefore, we argue that any single metric can just give a rough approximation to a database-multifaceted profile, and many other factors, such as user visits, page views, and community rating, should be considered in combination (see the Global Biodata Coalition at https://globalbiodata.org, attempting to identify core biodata resources worldwide that are crucial for sustaining the global biodata infrastructure).

To sum up, our study provides a comprehensive catalog of worldwide biological databases (https://ngdc.cncb.ac.cn/databasecommons), facilitating users to gain easy access and retrieval to a full collection of biological databases around the globe and yielding a global perspective to better understand their broad impact for life, medicine, and health sciences.

Data availability

An up-to-date catalog of worldwide biological databases as well as their curated meta-information and derived statistics is publicly available at Database Commons (https://ngdc.cncb.ac.cn/databasecommons/), which was built using Java, Spring boot, and MySQL.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Lina Ma: Conceptualization, Methodology, Data curation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Project administration, Funding acquisition. Dong Zou: Software, Data curation, Methodology. Lin Liu: Data curation, Visualization. Huma Shireen: Data curation. Amir A. Abbasi: Data curation. Alex Bateman: Data curation, Writing – review & editing. Jingfa Xiao: Conceptualization. Wenming Zhao: Conceptualization. Yiming Bao: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing. Zhang Zhang: Conceptualization, Methodology, Data curation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Project administration, Funding acquisition. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgments

We apologize to all those authors whose publications are not cited due to limited space. We thank more than fifty volunteers from the Beijing Institute of Genomics, Chinese Academy of Sciences and China National Center for Bioinformation, the Quaid-i-Azam University, and several database developers for their curation efforts (since 2015) in Database Commons. We sincerely thank Prof. Daniel Rigden (University of Liverpool, executive editor of Nucleic Acids Research database issue) for his kind recommendation of Database Commons for database registration. We also thank Jingchu Luo, Jun Yu, and Chuck Cook for their valuable comments and suggestions on this work. This work was supported by grants from the Strategic Priority Research Program of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (Grant Nos. XDA19090116 and XDA19050302), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Nos. 31871328 and 32030021), the Professional Association of the Alliance of International Science Organizations (Grant No. ANSO-PA-2020-07), the Youth Innovation Promotion Association of Chinese Academy of Sciences (Grant No. 2019104), and the International Partnership Program of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (Grant No. 153F11KYSB20160008).

Handled by Fangqing Zhao

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Beijing Institute of Genomics, Chinese Academy of Sciences / China National Center for Bioinformation and Genetics Society of China.

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gpb.2022.12.004.

Contributor Information

Lina Ma, Email: malina@big.ac.cn.

Zhang Zhang, Email: zhangzhang@big.ac.cn.

Supplementary material

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

Resources devoted to cataloging biological databases

References

- 1.Stein L.D. Integrating biological databases. Nat Rev Genet. 2003;4:337–345. doi: 10.1038/nrg1065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sanderson K. Bioinformatics: curation generation. Nature. 2011;470:295–296. doi: 10.1038/nj7333-295a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.International Society for Biocuration Biocuration: distilling data into knowledge. PLoS Biol. 2018;16:e2002846. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.2002846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Caswell J., Gans J.D., Generous N., Hudson C.M., Merkley E., Johnson C., et al. Defending our public biological databases as a global critical infrastructure. Front Bioeng Biotechnol. 2019;7:58. doi: 10.3389/fbioe.2019.00058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cantelli G., Bateman A., Brooksbank C., Petrov A.I., Malik-Sheriff R.S., Ide-Smith M., et al. The European Bioinformatics Institute (EMBL-EBI) in 2021. Nucleic Acids Res. 2022;50:D11–D19. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkab1127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.CNCB-NGDC Members & Partners. Database resources of the National Genomics Data Center, China National Center for Bioinformation in 2022. Nucleic Acids Res 2022;50:D27–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.Sayers E.W., Bolton E.E., Brister J.R., Canese K., Chan J., Comeau D.C., et al. Database resources of the National Center for Biotechnology Information. Nucleic Acids Res. 2022;50:D20–D26. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkab1112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.SIB Swiss Institute of Bioinformatics Members. The SIB Swiss Institute of Bioinformatics’ resources: focus on curated databases. Nucleic Acids Res 2016;44:D27–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Baker M. Databases fight funding cuts. Nature. 2012;489:19. doi: 10.1038/489019a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wren J.D., Bateman A. Databases, data tombs and dust in the wind. Bioinformatics. 2008;24:2127–2128. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btn464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Resources devoted to cataloging biological databases

Data Availability Statement

An up-to-date catalog of worldwide biological databases as well as their curated meta-information and derived statistics is publicly available at Database Commons (https://ngdc.cncb.ac.cn/databasecommons/), which was built using Java, Spring boot, and MySQL.