Abstract

Microrobots are being explored for biomedical applications such as drug delivery, biological cargo transport, and minimally invasive surgery. However, current efforts largely focus on proof-of-concept studies with non-translatable materials through a “design-and-apply” approach, limiting the potential for clinical adaptation. While these proof-of-concept studies have been key to advancing microrobot technologies, we believe that the distinguishing capabilities of microrobots will be most readily brought to patient bedsides through a “design-by-problem” approach, which involves focusing on unsolved problems to inform the design of microrobots with practical capabilities. As outlined below, we propose that the clinical translation of microrobots will be accelerated by a judicious choice of target applications, improved delivery considerations, and the rational selection of translation-ready biomaterials, ultimately reducing patient burden and enhancing the efficacy of therapeutic drugs for difficult-to-treat diseases.

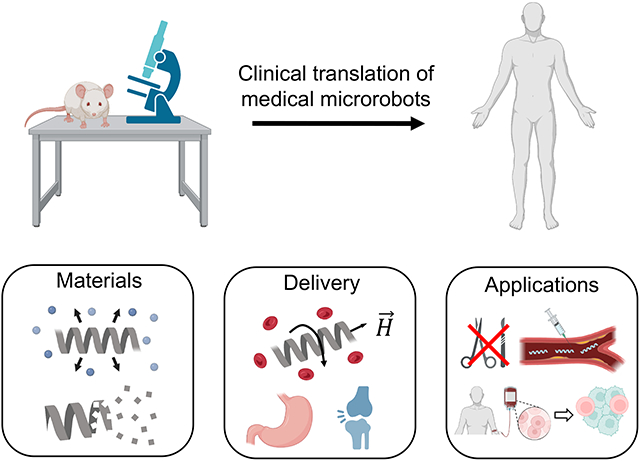

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

Microrobots are micron-sized objects that carry out programmable actions such as sensing,1 object manipulation,2 and enhanced navigation3 when powered by external fields or environmental sources. Common strategies to power microrobots include external fields, such as magnetic,4 acoustic,5 and electric fields,6 and environmental sources, such as chemical reactions7-9 and biological signals.10 Due to their programmable action, the small size of microrobots enables their use in traditionally difficult-to-reach environments, such as blood vessels, cavities, and confined porous media (i.e., cortical bone,11 mucus,12 and extracellular matrix13) found within the human body. Moreover, force acting on microrobots powered by external fields is significantly greater than those acting on nanoparticles, allowing them to reach to target sites effectively.14-16 This bestows microrobots the potential of revolutionizing minimally invasive medicine and the targeted delivery of therapeutic agents.

Despite the immense promise of medical microrobots, there has been limited translation of these technologies from the lab bench to pre-clinical or clinical settings. We believe this is because the community has primarily focused on a small portion of the major challenges associated with this emerging technology, shying away from more practical challenges required to move microrobots to clinical settings. It is often claimed that increased robot intelligence, more advanced materials, and higher resolution imaging are the key challenges that remain. However, designing microrobots that address these issues promotes the development of laboratory-specific toolboxes for problems that may not necessarily address actual clinical needs. More importantly, this focus lends itself towards continued proof-of-concept studies, such as demonstrating enhanced maneuverability, resulting in technologies that are not practical in clinical scenarios (e.g., remote surgery, in situ sensing, and biopsy collection).

While there is utility in proof-of-concept studies that advance our knowledge, highlight the functionality of medical microrobots, and provide a solid groundwork for future advancements, we believe that the key to clinical translation is shifting our collective focus toward addressing disease states that lack efficacious treatments. This requires i) shifting scientific effort to address more realistic biomedical applications, ii) developing application-specific microrobot delivery requirements, and iii) using materials with the necessary properties (e.g., degradation, clearance, and immune interactions) for clinical feasibility. Finally, each of these steps must be accompanied by earlier and more frequent communication with clinicians and end users to help shepherd medical microrobots from the lab to the bedside and improve current treatment outcomes.

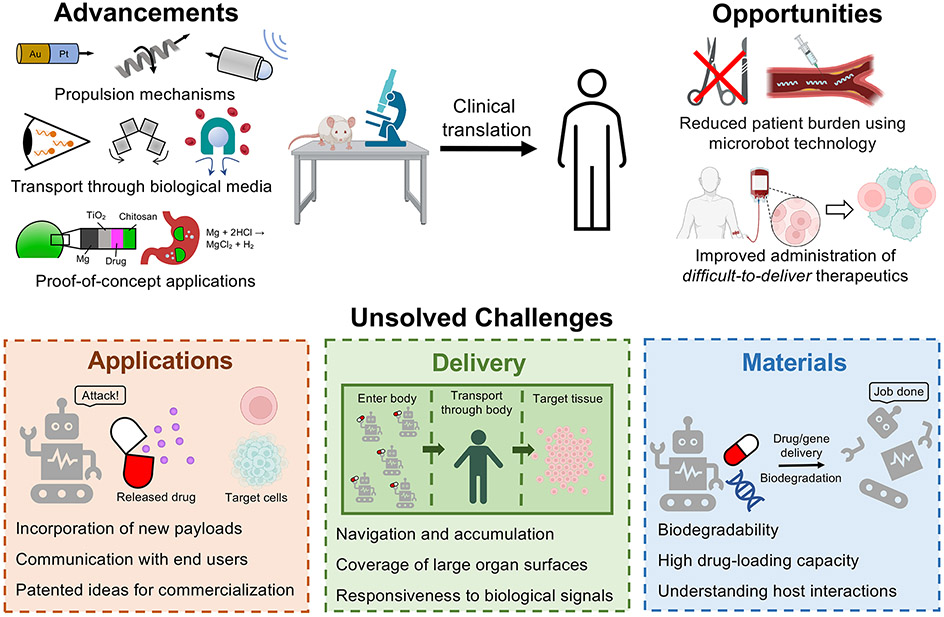

In this perspective, we outline what we identify as the most important advancements, opportunities, and unsolved challenges in three different aspects of translating microrobots from proof-of-concept studies to clinical applications (Figure 1). First, we articulate which biomedical applications are most ready for microrobots, focusing on use cases that can be tested in biologically relevant environments and take advantage of the strengths of microrobots for ailments that currently lack effective treatments. Second, we discuss the negative consequences of prioritizing studies that focus on single particle locomotion instead of improving the localization or dispersion of microrobots in vivo. Lastly, we detail how advances in materials chemistry from the drug delivery community must be used to accelerate the clinical translation of microrobots.

Figure 1.

Advancements, opportunities, and unsolved challenges for the clinical translation of medical microrobots. Some parts of this figure were made with BioRender.

Applications

The revolutionary capabilities of microrobots have sparked a flurry of scientific research aimed at pushing the boundaries of biomedical research. Advancements in propulsion science, materials engineering, and fluid mechanics has enabled engineers and scientists to create microrobots with a suite of functionalities.17-24 Such functions include transporting living cells and other biological cargo, moving through complex heterogeneous biological media, providing targeted and controlled drug delivery,29,30 offering switchable control over modes of locomotion,31,32 and enabling in vivo imaging.33 These advancements have fueled proof-of-concept studies in areas such as ocular drug delivery,14 in vitro fertilization,25 root canal prevention,34 and tumor treatment,4 among others. Additionally, some theoretical and experimental studies have shown the propulsion of microrobots in non-Newtonian environments to highlight their potential for use in vivo.15,35,36

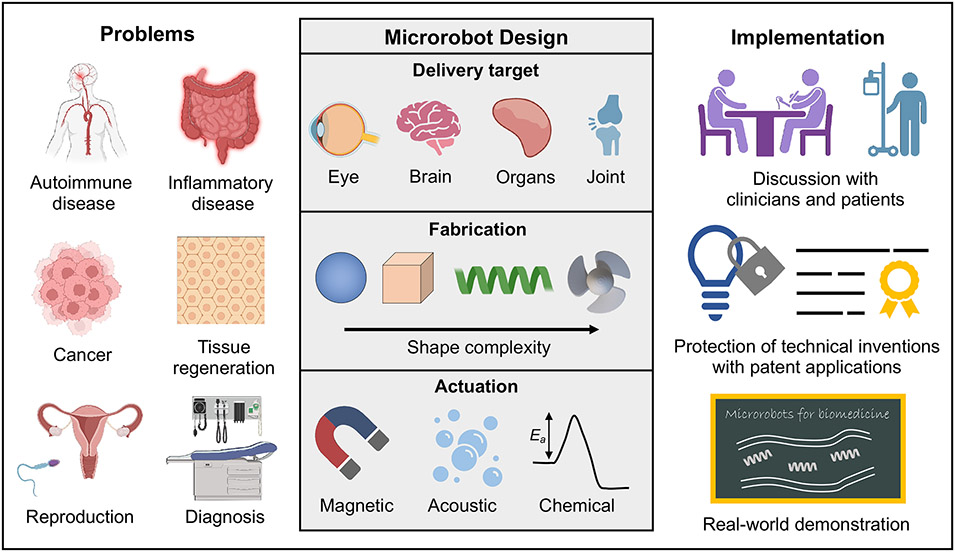

Despite this, most of the medical microrobots developed to date have focused on proof-of-concept applications under controlled benchtop conditions, while claiming improbable applications. We believe the origins of these limitations for translation are due to the “design-and-apply” approach that is commonly employed, which focuses on the fabrication and propulsion of microrobots under non-physiological settings. This approach only highlights the potential for microrobots; it seldom solves a practical and unmet clinical need. Thus, to go beyond the bench toward useful applications in humans, we propound that medical microrobots must be developed using a “design-by-problem” approach (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Medical microrobots design approach for real-world applications. Some parts of this figure were made with BioRender.

To apply a “design-by-problem” approach, microrobots should first and foremost be designed to solve biomedical problems that lack effective options and can be overcome by leveraging the specific strengths of the microrobots. For example, to use microrobots for cancer treatment, they must carry therapeutic agents and penetrate the tumor stroma and cellular junctions.37 This capability is difficult to achieve with traditional nanoparticles alone. While nanoparticles have shown utility in biomedicine as therapeutic delivery vehicles,38-41 they rely on passive diffusion or circulation for transport, subjecting them to both physical and biological barriers that limits their delivery efficiency to places like solid tumors (i.e., only ≈ 0.7% of systemically injected nanoparticles reach solid tumors).42 Thus, designing microrobots with specific transport capabilities will be necessary for many biomedical applications to avoid biological filters. Moreover, once microrobots enter in vivo environments, the adsorption of macromolecules on their surfaces leads to protein corona formation that may influence their propulsion, interactions with target cells, degradation, or internalization by phagocytes.43 Therefore, tailored microrobot design to maintain stability and function after in vivo administration should be addressed. While judicious material choices can be employed to offset this issue, transport and actuation mechanisms that may be inhibited by such biological interactions should be avoided. This illustrates the need for greater communication across research disciplines; for example, collaboration between materials scientists, physicists, and immunologists would promote an understanding of the limitations associated with multiple aspects of microrobot design. For synergistic problem solving to occur, researchers must be willing to communicate the strengths and limitations of their approaches across disciplines both frequently and candidly such that collaborations can be more easily forged.

Another challenge for the clinical translation of medical microrobots is to drive propulsion at high Reynolds numbers. Intravenous injection of microrobots will initially result in convection-dominated transport, yet most proof-of-concept studies are performed at low Reynolds numbers.44 Thus, the route of administration should be carefully considered to avoid navigation in areas of fast flow such as the cardiovascular system. These considerations should also inform the intended application of medical microrobots. For example, microsurgery or remote biopsy may be heavily impacted by flow conditions that make precise control difficult. When considering the administration of medical microrobots in clinical settings, the methods used should avoid exposure to regions with high fluid flows when possible, as this may result in limited control over where the microrobots accumulate. Some promising focus areas we identify include creating microrobots with a high drug loading capacity45, controlling drug release rates in vivo46, maximizing microrobot retention time47, and selecting administration routes with minimal travel requirements48.

Delivery

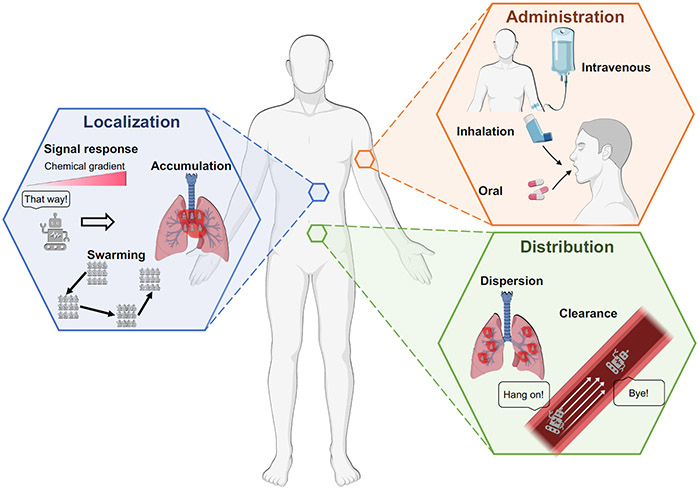

The delivery and transport of microrobots is another key aspect of their potential use in biomedical applications (Figure 3). Microrobots must be delivered to the correct area in the body, with the correct number density, at the correct time. This task is complicated by the complexity of the biological environments that microrobots may encounter. During transport, microrobots must often move through tortuous networks filled with complex fluids, penetrate biological tissues, and respond to interactions from other micron-sized objects such as cells.49-51 These challenges have compelled researchers to focus on building single microrobots that can move through increasingly complex environments with high resolution. However, such capabilities are far less useful when the clinical application involves driving thousands to millions of robots through tortuous three-dimensional pathways within the body.

Figure 3.

Considerations and strategies for the delivery of microrobots in vivo. Some parts of this figure were made with BioRender.

In this respect, several microrobots have been proposed to offer high resolution maneuverability in complex environments.15,31,52-55 While this problem is interesting from a fundamental perspective and will enable future studies on directing the motions of multiple microrobots, single microparticle maneuverability in a complex physiological environment is not applicable to most biomedical tasks. Applications such as medical catheterization, stent placement, and clot clearance do require precise single particle manipulation;56,57 however, many proposed applications such as remote biopsy, surgery, and sensing are likely infeasible given the current capabilities of microrobots, meaning that a focus on such applications will only hinder clinical translatability. To motivate translatable efforts, we believe that a greater emphasis should be placed on their use in drug delivery, an application that will more readily bring microrobots to the bedside and eventually lead to other applications.

The delivery of therapeutic payloads takes advantage of the ability of microrobots to enhance the localization and release of drugs. In this way, an ideal microrobot system for drug delivery must be able to i) migrate to the region of interest with high specificity and ii) disperse itself within that region. These functionalities are non-trivial. First, the transport of multiple microrobots to the desired region must be considered. Similar to single microrobot transport, biological barriers, complex fluids, and innate clearance mechanisms make it difficult to maneuver to, and sustain many microrobots within, a region of interest. Additionally, there is often the challenge of determining where the region of interest is located (e.g., the precise location of a neoplastic tumor). One promising mechanism to address this challenge is using microrobots that can home to the regions of interest by responding to inherent chemical signals such as chemokines. Alternatively, to circumvent these issues, researchers could address medical ailments that reside in well-defined regions of the body where microrobots have proven transport capabilities. This could include the gastrointestinal tract,58 reproductive system25, bladder,47 lungs,59,60 and eye.14 These environments are all easily accessible through non-invasive means, enabling facile dispatching.

Despite the challenges associated with using microrobots to deliver drugs, the opportunities are plentiful, and careful implementation could create drug delivery systems that greatly improve patient outcomes. One exciting opportunity is in the development of microrobots that can respond to signals released from target areas in the body by creating cell-microrobot complexes.4,61 These complexes take advantage of the chemotactic capabilities of cells and may enhance the localization of microrobots at target sites. Another promising opportunity to accelerate the therapeutic efficacy of microrobots is the use of robotic swarms.59,62-64 Swarming allows for the localized movement of large amounts of microrobots, which could improve both imaging capabilities and payload delivery.65 One final opportunity is to engineer microrobots that remain at target sites by utilizing microrobots with high surface areas,66 adhesive surface coatings,67 or responsiveness to stimuli to promote robust physical interactions with target tissues,47,68 to better tolerate biological clearance mechanisms, such as strong fluid flow.47,68,69

We also believe there is an opportunity to show that microrobots perform in a manner superior to traditional micro- or nanoparticles in drug delivery, something that has not yet been adequately investigated by the community. By showing that microrobots can accumulate at target sites better than traditional (non-active) particle systems and provide better mechanisms for controlling the release of drugs within those target sites, microrobots may be poised as a top contender for particle-based drug delivery systems.

Materials

The persistence of microrobots at target sites depends on the method of administration and their final delivery location. Use of microrobots in areas that involve direct clearance mechanisms (e.g., the bladder, where microrobots attached to the epithelial lining can be shed and excreted through urination,47 or the lungs, where coughing or mucociliary action can eject microrobots through the trachea70) allows for use of materials that are biocompatible but not biodegradable.47,71 In contrast, applications in regions where microrobots cannot be reliably cleared by phagocytosis or excretion (e.g., solid tumors, where microrobots can be trapped to dense tissue microstructures, or in the bloodstream, where large microrobots cannot undergo digestion in phagosomes or kidney filtration) are common.72-75 In these systems, non-biodegradable microrobots are unusable. Despite the necessity of biodegradability for many biomedical applications, current efforts continue to focus on designing proof-of-concept microrobots with non-biodegradable components, limiting their potential for in vivo testing. While proof-of-concept studies are useful for establishing feasibility, a greater emphasis must be placed on moving past such systems developed with non-biodegradable materials and toward in vivo testing with translation-ready biomaterials.

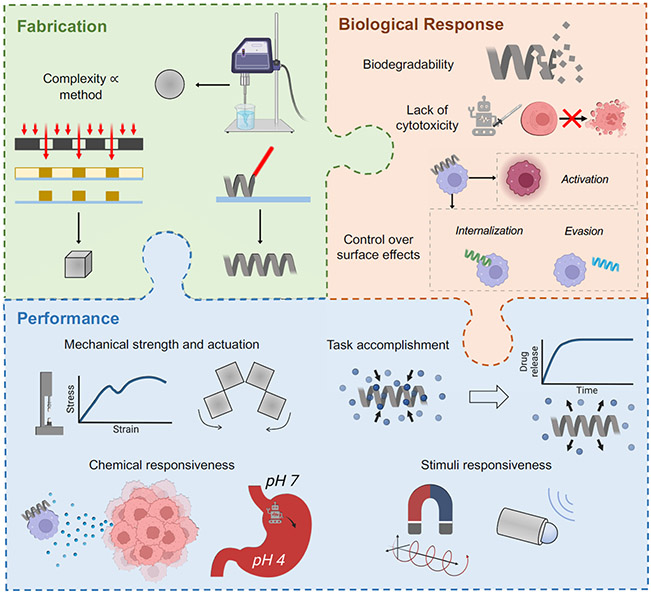

Innovations in drug delivery systems over the last several decades provide a foundation for implementing biodegradable materials into microrobots. Using drug delivery materials that have already been clinically investigated (e.g., polyesters, phospholipids, polysaccharides) will allow for accelerated translation due to FDA approval and the wealth of supporting literature.76 However, fabrication techniques compatible with most of the materials used for drug delivery tend to limit the complexity of particles that can be fabricated (e.g., spheres, discs, or ellipsoids).61,77 Particle designs that can undergo complex transport, such as helices or particles with well-defined cavities, require the use of high-resolution lithography. Therefore, there is a critical need for simple, robust, and tunable materials that are biodegradable and photocurable.78

Alternatively, multi-step fabrication techniques such as molding/templating can be implemented to formulate microrobots from non-photocurable materials. Molding allows for the use of non-biodegradable materials to form negative shapes with high complexity, followed by backfilling with the desired biodegradable material. This approach may enable the rapid use of biodegradable materials that are non-photocurable, but it requires careful consideration of solvents and often has limited throughput compared to lithographic methods.79-82 One notable exception is the particle replication in non-wetting templates (PRINT®) method, a high-throughput fabrication process for generating complex particles for drug delivery, which demonstrates the potential for clinical translation of molding methods.83 While molding is a highly enabling process for the use of many common drug delivery materials, the need for photocurable drug delivery materials remains due to the resolution, reliability, and scalability of lithographic techniques. A comprehensive review of modern fabrication techniques can be found elsewhere.84

Hydrogels with photocurable linkers have been widely used for implants and in tissue engineering, and there are some examples of their successful use in microrobotics.19,85-87 However, applications of microrobots made from hydrogels are limited due to the swelling and relatively low mechanical strength of hydrogels. Given the challenge of designing biodegradable materials that enable complex task performance, we list a handful of synthetic polymers from the drug delivery and tissue engineering communities that are promising for making microrobots due to their history of use, biodegradation, hydrophobicity, and photocurable properties (Table 1). Natural materials such as polysaccharides, lipids, and extracellular matrix proteins, while also promising for the clinical translation of microrobots, have been described elsewhere.76,88

Table 1.

Biodegradable polymers for microrobot fabrication.

| Material | Degradation | Immune effects |

FDA approval |

Fabrication methods |

Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) [PLGA] | Bulk hydrolysis 1-6 months | Inert | Yes | Emulsion, molding | Degradation rate controlled by LA to GA ratio89,90 |

| Poly(β-amino ester) [PBAE] | Surface, then bulk, hydrolysis 1-2 years; 1-45 days modified | Inert | No | Emulsion, molding, photolithography | Acrylate modification necessary for photocuring; suitable for gene delivery due to positive charges78,91 |

| Polyhydroxyalk-anoate [PHA] | Surface hydrolysis and enzyme-mediated degradation 6 months-2 years | Minimally inflammatory | Yes (poly[4-hydroxybutyrate] only) | Emulsion, molding | Produced by bacterial fermentation92-94 |

| Polycaprolactone [PCL] | Bulk or surface hydrolysis (end-group dependent) 1-2 years | Inert | Yes (without modifications) | Emulsion, molding, photolithography | Methylacrylate modification necessary for photocuring95,96 |

| Poly(glycerol sebacate) [PGS] | Surface hydrolysis 2 months | Minimally inflammatory | Yes (reactants [glycerol, sebacic acid-containing polymers] only) | Emulsion, molding, photolithography | Acrylate modification necessary for photocuring97-100 |

| Polydioxanone [PDS] | Bulk hydrolysis 1-6 months | Minimally anti-inflammatory | Yes | Emulsion, molding | Commonly used as a copolymer101,102 |

In addition to these bulk materials, care must be taken to ensure that stimuli-responsive moieties used in microrobots (e.g., magnetic handles or catalytic patches) are biodegradable or at least biocompatible, such as using iron oxide for imparting magnetic responsiveness instead of cobalt.103,104 Materials considerations for the fabrication, biological response, and performance of microrobots are summarized in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Considerations for selecting or designing materials for microrobots. Some parts of this figure were made with BioRender.

We anticipate that drug, gene, and cell delivery will be one of the earliest opportunities for translating microrobots. As such, the physical properties of the drug and manner by which it is incorporated into the microrobot is a critical materials consideration. Drug loading capacity of small molecules, proteins, and nucleic acids in common drug delivery systems have been described elsewhere.105 Hydrophobic small molecules are one of the simplest therapeutic modalities to incorporate due to their stability in organic solvents and compatibility with many types of polymers; however, gene delivery, although more difficult, is an increasingly important therapeutic strategy that should be investigated for a range of disease types that are not treatable by other methods.106 For example, delivery of genes requires physical insertion into cells, making nonviral gene delivery a suitable target application for microrobots due to the potential for actuation-guided gene insertion.107 As such, strategies for transporting and delivering genes by microrobots should be prioritized.

For both cell delivery and other applications, exploiting materials immunogenicity may be a way to confer advantageous immune responses without the use of drugs or synergistically with drug release. Both the materials used for fabricating microrobots and their degradation products may provide some degree of immunomodulation, such as a proinflammatory response, which may be useful in treating diseases such as cancer. Often, immune activation is avoided (e.g., by inert surface coatings),85 where the aim is to prevent unwanted immune activation or premature clearance of microrobots. Instead, judicious materials selection may enable control over immune cell activation for a therapeutic benefit; a similar approach has been demonstrated through the use of cell membrane particle coatings.73 This design choice may allow for the use of a wider range of materials that were previously avoided due to unwanted immune effects. The opportunity for drug and gene delivery as well as therapeutic material-cell interactions should be leveraged to design medical microrobots with multiple therapeutic functionalities.

Conclusion

Microrobots are a budding technology with the potential to mold the future of minimally invasive medicine and drug delivery. Recent work has illustrated the potential of microrobots to accomplish challenging biomedical tasks such as targeted drug release, cell transport, and advanced imaging. Despite the competencies of microrobots, limited effort has been made to facilitate their translation to the bedside. This is due to the “design-and-apply” approach often taken, where in vitro proof-of-concept studies have been favored over deliberate pushes to pre-clinical and clinical trials through in vivo studies with translational materials. This can be overcome by applying a “design-by-problem” approach instead, wherein the intrinsic capabilities of microrobots are used to enhance the efficacy of treatments for diseases that currently lack effective treatment options. To accomplish this, researchers should prioritize feasible applications, consider the dispersion of microrobots in vivo, and use materials advancements from the drug delivery community to prepare translation-ready microrobots. One hurdle that may inhibit the adoption of a “design-by-problem” approach is a lack of funding sources and incentives to motivate researchers in basic science and in clinical settings to take on developmental challenges that are often considered incremental by funding agencies, academic institutions, and research journals. This might be alleviated by increased partnership with industry, wherein both monetary support and the motivation to translate technologies to patients will be more readily available. Microrobots designed with these principles will have numerous advantages that will support their clinical translation and may result in their widespread adoption in targeted drug delivery, in vivo imaging, and a collage of other applications.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by an NSF CAREER grant (CBET 2143419), the NIH (R35GM147455), the Office of Naval Research (ONR, N000142212541), and the U.S. Department of Education Graduate Assistantships in Areas of National Need (GAANN) Program for Soft Materials (ED P200A180070). Wyatt Shields is a Pew Scholar in the Biomedical Sciences, supported by the Pew Charitable Trusts. He would like to thank the Packard Foundation for their support of this project. Nicole Day is funded by the Teets Family Endowed Doctoral Fellowship in Nanotechnology.

References

- (1).Ergeneman O; Chatzipirpiridis G; Pokki J; Marin-Suárez M; Sotiriou GA; Medina-Rodriguez S; Sanchez JFF; Fernandez-Gutiérrez A; Pane S; Nelson BJ In Vitro Oxygen Sensing Using Intraocular Microrobots. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng 2012, 59 (11), 3104–3109. 10.1109/TBME.2012.2216264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Zhou H; Mayorga-Martinez CC; Pumera M Microplastic Removal and Degradation by Mussel-Inspired Adhesive Magnetic/Enzymatic Microrobots. Small Methods 2021, 5 (9), 2100230. 10.1002/smtd.202100230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Wu Z; Zhang Y; Ai N; Chen H; Ge W; Xu Q Magnetic Mobile Microrobots for Upstream and Downstream Navigation in Biofluids with Variable Flow Rate. Adv. Intell. Syst 2022, 4 (7), 2100266. 10.1002/aisy.202100266. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Gwisai T; Mirkhani N; Christiansen MG; Nguyen TT; Ling V; Schuerle S Magnetic Torque–Driven Living Microrobots for Increased Tumor Infiltration. Sci. Robot 2022, 7 (71), eabo0665. 10.1126/scirobotics.abo0665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Luo T; Wu M Biologically Inspired Micro-Robotic Swimmers Remotely Controlled by Ultrasound Waves. Lab. Chip 2021, 21 (21), 4095–4103. 10.1039/D1LC00575H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Han K; Shields CW; Velev OD Engineering of Self-Propelling Microbots and Microdevices Powered by Magnetic and Electric Fields. Adv. Funct. Mater 2018, 28 (25), 1705953. 10.1002/adfm.201705953. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Soler L; Magdanz V; Fomin VM; Sanchez S; Schmidt OG Self-Propelled Micromotors for Cleaning Polluted Water. ACS Nano 2013, 7 (11), 9611–9620. 10.1021/nn405075d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Paxton WF; Kistler KC; Olmeda CC; Sen A; St. Angelo SK; Cao Y; Mallouk TE; Lammert PE; Crespi VH Catalytic Nanomotors: Autonomous Movement of Striped Nanorods. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2004, 126 (41), 13424–13431. 10.1021/ja047697z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Ganguly A; Gupta A Going in Circles: Slender Body Analysis of a Self-Propelling Bent Rod. Phys. Rev. Fluids 2023, 8 (1), 014103. 10.1103/PhysRevFluids.8.014103. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Sanchez T; Chen DTN; DeCamp SJ; Heymann M; Dogic Z Spontaneous Motion in Hierarchically Assembled Active Matter. Nature 2012, 491 (7424), 431–434. 10.1038/nature11591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Augat P; Schorlemmer S The Role of Cortical Bone and Its Microstructure in Bone Strength. Age Ageing 2006, 35 (suppl_2), ii27–ii31. 10.1093/ageing/afl081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Yudin AI; Hanson FW; Katz DF Human Cervical Mucus and Its Interaction with Sperm: A Fine-Structural View. Biol. Reprod 1989, 40 (3), 661–671. 10.1095/biolreprod40.3.661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Alberts B; Bray D; Lewis J; Raff M; Roberts K; Watson JD In Molecular Biology of the Cell; Garland Publishing: New York, NY, 1994; pp 971–995. [Google Scholar]

- (14).Wu Z; Troll J; Jeong H-H; Wei Q; Stang M; Ziemssen F; Wang Z; Dong M; Schnichels S; Qiu T; Fischer P A Swarm of Slippery Micropropellers Penetrates the Vitreous Body of the Eye. Sci. Adv 2018, 4 (11), eaat4388. 10.1126/sciadv.aat4388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Aghakhani A; Pena-Francesch A; Bozuyuk U; Cetin H; Wrede P; Sitti M High Shear Rate Propulsion of Acoustic Microrobots in Complex Biological Fluids. Sci. Adv 2022, 8 (10), eabm5126. 10.1126/sciadv.abm5126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Shields CW Biohybrid Microrobots for Enhancing Adoptive Cell Transfers. Acc. Mater. Res 2023, accountsmr.3c00061. 10.1021/accountsmr.3c00061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Kummer MP; Abbott JJ; Kratochvil BE; Borer R; Sengul A; Nelson BJ OctoMag: An Electromagnetic System for 5-DOF Wireless Micromanipulation. IEEE Trans. Robot 2010, 26 (6), 1006–1017. 10.1109/TRO.2010.2073030. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Roth EJ; Zimmermann CJ; Disharoon D; Tasci TO; Marr DWM; Neeves KB An Experimental Design for the Control and Assembly of Magnetic Microwheels. Rev. Sci. Instrum 2020, 91 (9), 093701. 10.1063/5.0010805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Ceylan H; Yasa IC; Yasa O; Tabak AF; Giltinan J; Sitti M 3D-Printed Biodegradable Microswimmer for Theranostic Cargo Delivery and Release. ACS Nano 2019, 13 (3), 3353–3362. 10.1021/acsnano.8b09233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Harinarayana V; Shin YC Two-Photon Lithography for Three-Dimensional Fabrication in Micro/Nanoscale Regime: A Comprehensive Review. Opt. Laser Technol 2021, 142, 107180. 10.1016/j.optlastec.2021.107180. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Esparza López C; Gonzalez-Gutierrez J; Solorio-Ordaz F; Lauga E; Zenit R Dynamics of a Helical Swimmer Crossing Viscosity Gradients. Phys. Rev. Fluids 2021, 6 (8), 083102. 10.1103/PhysRevFluids.6.083102. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Bertin N; Spelman TA; Stephan O; Gredy L; Bouriau M; Lauga E; Marmottant P Propulsion of Bubble-Based Acoustic Microswimmers. Phys. Rev. Appl 2015, 4 (6), 064012. 10.1103/PhysRevApplied.4.064012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Thome CP; Hoertdoerfer WS; Bendorf JR; Lee JG; Shields CW Electrokinetic Active Particles for Motion-Based Biomolecule Detection. Nano Lett. 2023, 23 (6), 2379–2387. 10.1021/acs.nanolett.3c00319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Han K. Electric and Magnetic Field-Driven Dynamic Structuring for Smart Functional Devices. Micromachines 2023, 14 (3), 661. 10.3390/mi14030661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Medina-Sánchez M; Schwarz L; Meyer AK; Hebenstreit F; Schmidt OG Cellular Cargo Delivery: Toward Assisted Fertilization by Sperm-Carrying Micromotors. Nano Lett. 2016, 16 (1), 555–561. 10.1021/acs.nanolett.5b04221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Ren L; Nama N; McNeill JM; Soto F; Yan Z; Liu W; Wang W; Wang J; Mallouk TE 3D Steerable, Acoustically Powered Microswimmers for Single-Particle Manipulation. Sci. Adv 2019, 5 (10), eaax3084. 10.1126/sciadv.aax3084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Bishop KJM; Biswal SL; Bharti B Active Colloids as Models, Materials, and Machines. Annu. Rev. Chem. Biomol. Eng 2023, 14 (1), annurev-chembioeng-101121-084939. 10.1146/annurev-chembioeng-101121-084939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Al Harraq A; Bello M; Bharti B A Guide to Design the Trajectory of Active Particles: From Fundamentals to Applications. Curr. Opin. Colloid Interface Sci 2022, 61, 101612. 10.1016/j.cocis.2022.101612. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Bozuyuk U; Yasa O; Yasa IC; Ceylan H; Kizilel S; Sitti M Light-Triggered Drug Release from 3D-Printed Magnetic Chitosan Microswimmers. ACS Nano 2018, 12 (9), 9617–9625. 10.1021/acsnano.8b05997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).De Ávila BE-F; Angsantikul P; Li J; Angel Lopez-Ramirez M; Ramírez-Herrera DE; Thamphiwatana S; Chen C; Delezuk J; Samakapiruk R; Ramez V; Obonyo M; Zhang L; Wang J Micromotor-Enabled Active Drug Delivery for in Vivo Treatment of Stomach Infection. Nat. Commun 2017, 8 (1), 272. 10.1038/s41467-017-00309-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Ze Q; Wu S; Dai J; Leanza S; Ikeda G; Yang PC; Iaccarino G; Zhao RR Spinning-Enabled Wireless Amphibious Origami Millirobot. Nat. Commun 2022, 13 (1), 3118. 10.1038/s41467-022-30802-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Yang T; Tomaka A; Tasci TO; Neeves KB; Wu N; Marr DWM Microwheels on Microroads: Enhanced Translation on Topographic Surfaces. Sci. Robot 2019, 4 (32), eaaw9525. 10.1126/scirobotics.aaw9525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Wang Q; Chan KF; Schweizer K; Du X; Jin D; Yu SCH; Nelson BJ; Zhang L Ultrasound Doppler-Guided Real-Time Navigation of a Magnetic Microswarm for Active Endovascular Delivery. Sci. Adv 2021, 7 (9), eabe5914. 10.1126/sciadv.abe5914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).Dasgupta D; Peddi S; Saini DK; Ghosh A Mobile Nanobots for Prevention of Root Canal Treatment Failure. Adv. Healthc. Mater 2022, 11 (14), 2200232. 10.1002/adhm.202200232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35).Han K; Shields CW; Bharti B; Arratia PE; Velev OD Active Reversible Swimming of Magnetically Assembled “Microscallops” in Non-Newtonian Fluids. Langmuir 2020, 36 (25), 7148–7154. 10.1021/acs.langmuir.9b03698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (36).Supekar R; Song B; Hastewell A; Choi GPT; Mietke A; Dunkel J Learning Hydrodynamic Equations for Active Matter from Particle Simulations and Experiments. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci 2023, 120 (7), e2206994120. 10.1073/pnas.2206994120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (37).Schmidt CK; Medina-Sánchez M; Edmondson RJ; Schmidt OG Engineering Microrobots for Targeted Cancer Therapies from a Medical Perspective. Nat. Commun 2020, 11 (1), 5618. 10.1038/s41467-020-19322-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (38).Vargason AM; Anselmo AC; Mitragotri S The Evolution of Commercial Drug Delivery Technologies. Nat. Biomed. Eng 2021, 5 (9), 951–967. 10.1038/s41551-021-00698-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (39).Mitchell MJ; Billingsley MM; Haley RM; Wechsler ME; Peppas NA; Langer R Engineering Precision Nanoparticles for Drug Delivery. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov 2021, 20 (2), 101–124. 10.1038/s41573-020-0090-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (40).Day NB; Dalhuisen R; Loomis NE; Adzema SG; Prakash J; Shields CW IV Tissue-Adhesive Hydrogel for Multimodal Drug Release to Immune Cells in Skin. Acta Biomater. 2022, 150, 211–220. 10.1016/j.actbio.2022.07.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (41).Trac N; Ashraf A; Giblin J; Prakash S; Mitragotri S; Chung EJ Spotlight on Genetic Kidney Diseases: A Call for Drug Delivery and Nanomedicine Solutions. ACS Nano 2023, 17 (7), 6165–6177. 10.1021/acsnano.2c12140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (42).Wilhelm S; Tavares AJ; Dai Q; Ohta S; Audet J; Dvorak HF; Chan WCW Analysis of Nanoparticle Delivery to Tumours. Nat. Rev. Mater 2016, 1 (5), 16014. 10.1038/natrevmats.2016.14. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (43).Lee JG; Lannigan K; Shelton WA; Meissner J; Bharti B Adsorption of Myoglobin and Corona Formation on Silica Nanoparticles. Langmuir 2020, 36 (47), 14157–14165. 10.1021/acs.langmuir.0c01613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (44).Nauber R; Goudu SR; Goeckenjan M; Bornhäuser M; Ribeiro C; Medina-Sánchez M Medical Microrobots in Reproductive Medicine from the Bench to the Clinic. Nat. Commun 2023, 14 (1), 728. 10.1038/s41467-023-36215-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (45).Lee H; Park S Magnetically Actuated Helical Microrobot with Magnetic Nanoparticle Retrieval and Sequential Dual-Drug Release Abilities. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2023, 15 (23), 27471–27485. 10.1021/acsami.3c01087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (46).Chen H; Zhang H; Dai Y; Zhu H; Hong G; Zhu C; Qian X; Chai R; Gao X; Zhao Y Magnetic Hydrogel Microrobots Delivery System for Deafness Prevention. Adv. Funct. Mater 2023, 2303011. 10.1002/adfm.202303011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (47).Lee JG; Raj RR; Thome CP; Day NB; Martinez P; Bottenus N; Gupta A; Wyatt Shields C Bubble-Based Microrobots with Rapid Circular Motions for Epithelial Pinning and Drug Delivery. Small 2023, 2300409. 10.1002/smll.202300409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (48).Esteban-Fernández De Ávila B; Angell C; Soto F; Lopez-Ramirez MA; Báez DF; Xie S; Wang J; Chen Y Acoustically Propelled Nanomotors for Intracellular SiRNA Delivery. ACS Nano 2016, 10 (5), 4997–5005. 10.1021/acsnano.6b01415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (49).Xu H; Medina-Sánchez M; Maitz MF; Werner C; Schmidt OG Sperm Micromotors for Cargo Delivery through Flowing Blood. ACS Nano 2020, 14 (3), 2982–2993. 10.1021/acsnano.9b07851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (50).Li D; Jeong M; Oren E; Yu T; Qiu T A Helical Microrobot with an Optimized Propeller-Shape for Propulsion in Viscoelastic Biological Media. Robotics 2019, 8 (4), 87. 10.3390/robotics8040087. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (51).Venugopalan PL; Ghosh A Investigating the Dynamics of the Magnetic Micromotors in Human Blood. Langmuir 2021, 37 (1), 289–296. 10.1021/acs.langmuir.0c02881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (52).Wang X; Hu C; Pane S; Nelson BJ Dynamic Modeling of Magnetic Helical Microrobots. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett 2022, 7 (2), 1682–1688. 10.1109/LRA.2020.3049112. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (53).Tan L; Cappelleri DJ Design, Fabrication, and Characterization of a Helical Adaptive Multi-Material MicroRobot (HAMMR). IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett 2023, 8 (3), 1723–1730. 10.1109/LRA.2023.3242164. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (54).Walker D; Käsdorf BT; Jeong H-H; Lieleg O; Fischer P Enzymatically Active Biomimetic Micropropellers for the Penetration of Mucin Gels. Sci. Adv 2015, 1 (11), e1500501. 10.1126/sciadv.1500501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (55).Chen Y; Lordi N; Taylor M; Pak OS Helical Locomotion in a Porous Medium. Phys. Rev. E 2020, 102 (4), 043111. 10.1103/PhysRevE.102.043111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (56).Hwang J; Jeon S; Kim B; Kim J; Jin C; Yeon A; Yi B; Yoon C; Park H; Pané S; Nelson BJ; Choi H An Electromagnetically Controllable Microrobotic Interventional System for Targeted, Real-Time Cardiovascular Intervention. Adv. Healthc. Mater 2022, 11 (11), 2102529. 10.1002/adhm.202102529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (57).Fischer C; Boehler Q; Nelson BJ Using Magnetic Fields to Navigate and Simultaneously Localize Catheters in Endoluminal Environments. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett 2022, 7 (3), 7217–7223. 10.1109/LRA.2022.3181420. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (58).Srinivasan SS; Alshareef A; Hwang AV; Kang Z; Kuosmanen J; Ishida K; Jenkins J; Liu S; Madani WAM; Lennerz J; Hayward A; Morimoto J; Fitzgerald N; Langer R; Traverso G RoboCap: Robotic Mucus-Clearing Capsule for Enhanced Drug Delivery in the Gastrointestinal Tract. Sci. Robot 2022, 7 (70), eabp9066. 10.1126/scirobotics.abp9066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (59).Zimmermann CJ; Herson PS; Neeves KB; Marr DWM Multimodal Microwheel Swarms for Targeting in Three-Dimensional Networks. Sci. Rep 2022, 12 (1), 5078. 10.1038/s41598-022-09177-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (60).Zimmermann CJ; Schraeder T; Reynolds B; DeBoer EM; Neeves KB; Marr DWM Delivery and Actuation of Aerosolized Microbots. Nano Sel. 2022, 3 (7), 1185–1191. 10.1002/nano.202100353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (61).Shields CW; Evans MA; Wang LL-W; Baugh N; Iyer S; Wu D; Zhao Z; Pusuluri A; Ukidve A; Pan DC; Mitragotri S Cellular Backpacks for Macrophage Immunotherapy. Sci. Adv 2020, 6 (18), eaaz6579. 10.1126/sciadv.aaz6579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (62).Yang L; Jiang J; Gao X; Wang Q; Dou Q; Zhang L Autonomous Environment-Adaptive Microrobot Swarm Navigation Enabled by Deep Learning-Based Real-Time Distribution Planning. Nat. Mach. Intell 2022, 4 (5), 480–493. 10.1038/s42256-022-00482-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (63).Dong X; Sitti M Controlling Two-Dimensional Collective Formation and Cooperative Behavior of Magnetic Microrobot Swarms. Int. J. Robot. Res 2020, 39 (5), 617–638. 10.1177/0278364920903107. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (64).Xie H; Sun M; Fan X; Lin Z; Chen W; Wang L; Dong L; He Q Reconfigurable Magnetic Microrobot Swarm: Multimode Transformation, Locomotion, and Manipulation. Sci. Robot 2019, 4 (28), eaav8006. 10.1126/scirobotics.aav8006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (65).Fraire JC; Guix M; Hortelao AC; Ruiz-González N; Bakenecker AC; Ramezani P; Hinnekens C; Sauvage F; De Smedt SC; Braeckmans K; Sánchez S Light-Triggered Mechanical Disruption of Extracellular Barriers by Swarms of Enzyme-Powered Nanomotors for Enhanced Delivery. ACS Nano 2023, acsnano.2c09380. 10.1021/acsnano.2c09380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (66).Roh S; Williams AH; Bang RS; Stoyanov SD; Velev OD Soft Dendritic Microparticles with Unusual Adhesion and Structuring Properties. Nat. Mater 2019, 18 (12), 1315–1320. 10.1038/s41563-019-0508-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (67).Guo J; Tardy BL; Christofferson AJ; Dai Y; Richardson JJ; Zhu W; Hu M; Ju Y; Cui J; Dagastine RR; Yarovsky I; Caruso F Modular Assembly of Superstructures from Polyphenol-Functionalized Building Blocks. Nat. Nanotechnol 2016, 11 (12), 1105–1111. 10.1038/nnano.2016.172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (68).Lee Y; Kim J; Bozuyuk U; Dogan NO; Khan MTA; Shiva A; Wild A; Sitti M Multifunctional 3D-Printed Pollen Grain-Inspired Hydrogel Microrobots for On-Demand Anchoring and Cargo Delivery. Adv. Mater 2023, 2209812. 10.1002/adma.202209812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (69).Soon RH; Ren Z; Hu W; Bozuyuk U; Yildiz E; Li M; Sitti M On-Demand Anchoring of Wireless Soft Miniature Robots on Soft Surfaces. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci 2022, 119 (34), e2207767119. 10.1073/pnas.2207767119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (70).El-Sherbiny IM; Villanueva DG; Herrera D; Smyth HDC Overcoming Lung Clearance Mechanisms for Controlled Release Drug Delivery. In Controlled Pulmonary Drug Delivery; Smyth HDC, Hickey AJ, Eds.; Springer New York: New York, NY, 2011; pp 101–126. 10.1007/978-1-4419-9745-6_5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (71).Cong Z; Tang S; Xie L; Yang M; Li Y; Lu D; Li J; Yang Q; Chen Q; Zhang Z; Zhang X; Wu S Magnetic-Powered Janus Cell Robots Loaded with Oncolytic Adenovirus for Active and Targeted Virotherapy of Bladder Cancer. Adv. Mater 2022, 34 (26), 2201042. 10.1002/adma.202201042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (72).Zhou J; Karshalev E; Mundaca-Uribe R; Esteban-Fernández de Ávila B; Krishnan N; Xiao C; Ventura CJ; Gong H; Zhang Q; Gao W; Fang RH; Wang J; Zhang L Physical Disruption of Solid Tumors by Immunostimulatory Microrobots Enhances Antitumor Immunity. Adv. Mater 2021, 33 (49), 2103505. 10.1002/adma.202103505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (73).Song X; Qian R; Li T; Fu W; Fang L; Cai Y; Guo H; Xi L; Cheang UK Imaging-Guided Biomimetic M1 Macrophage Membrane-Camouflaged Magnetic Nanorobots for Photothermal Immunotargeting Cancer Therapy. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2022, 14 (51), 56548–56559. 10.1021/acsami.2c16457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (74).Dai Y; Bai X; Jia L; Sun H; Feng Y; Wang L; Zhang C; Chen Y; Ji Y; Zhang D; Chen H; Feng L Precise Control of Customized Macrophage Cell Robot for Targeted Therapy of Solid Tumors with Minimal Invasion. Small 2021, 17 (41), 2103986. 10.1002/smll.202103986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (75).Chen H; Li Y; Wang Y; Ning P; Shen Y; Wei X; Feng Q; Liu Y; Li Z; Xu C; Huang S; Deng C; Wang P; Cheng Y An Engineered Bacteria-Hybrid Microrobot with the Magnetothermal Bioswitch for Remotely Collective Perception and Imaging-Guided Cancer Treatment. ACS Nano 2022, 16 (4), 6118–6133. 10.1021/acsnano.1c11601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (76).Shields CW; Wang LL; Evans MA; Mitragotri S Materials for Immunotherapy. Adv. Mater 2020, 32 (13), 1901633. 10.1002/adma.201901633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (77).Yoo J-W; Mitragotri S Polymer Particles That Switch Shape in Response to a Stimulus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci 2010, 107 (25), 11205–11210. 10.1073/pnas.1000346107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (78).Muralidharan A; McLeod RR; Bryant SJ Hydrolytically Degradable Poly(B-amino Ester) Resins with Tunable Degradation for 3D Printing by Projection Micro-Stereolithography. Adv. Funct. Mater 2022, 32 (6), 2106509. 10.1002/adfm.202106509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (79).de Marco C; Alcântara CCJ; Kim S; Briatico F; Kadioglu A; de Bernardis G; Chen X; Marano C; Nelson BJ; Pané S Indirect 3D and 4D Printing of Soft Robotic Microstructures. Adv. Mater. Technol 2019, 4 (9), 1900332. 10.1002/admt.201900332. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (80).Liu Z; Li M; Dong X; Ren Z; Hu W; Sitti M Creating Three-Dimensional Magnetic Functional Microdevices via Molding-Integrated Direct Laser Writing. Nat. Commun 2022, 13 (1), 2016. 10.1038/s41467-022-29645-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (81).Alcântara CCJ; Landers FC; Kim S; De Marco C; Ahmed D; Nelson BJ; Pané S Mechanically Interlocked 3D Multi-Material Micromachines. Nat. Commun 2020, 11 (1), 5957. 10.1038/s41467-020-19725-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (82).Sanchis-Gual R; Ye H; Ueno T; Landers FC; Hertle L; Deng S; Veciana A; Xia Y; Franco C; Choi H; Puigmartí-Luis J; Nelson BJ; Chen X; Pané S 3D Printed Template-Assisted Casting of Biocompatible Polyvinyl Alcohol-Based Soft Microswimmers with Tunable Stability. Adv. Funct. Mater 2023, 2212952. 10.1002/adfm.202212952. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (83).DeSimone JM Co-Opting Moore’s Law: Therapeutics, Vaccines and Interfacially Active Particles Manufactured via PRINT®. J. Controlled Release 2016, 240, 541–543. 10.1016/j.jconrel.2016.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (84).Dabbagh SR; Sarabi MR; Birtek MT; Seyfi S; Sitti M; Tasoglu S 3D-Printed Microrobots from Design to Translation. Nat. Commun 2022, 13 (1), 5875. 10.1038/s41467-022-33409-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (85).Cabanach P; Pena-Francesch A; Sheehan D; Bozuyuk U; Yasa O; Borros S; Sitti M Zwitterionic 3D-Printed Non-Immunogenic Stealth Microrobots. Adv. Mater 2020, 32 (42), 2003013. 10.1002/adma.202003013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (86).Wu J; Liu L; Chen B; Ou J; Wang F; Gao J; Jiang J; Ye Y; Wang S; Tong F; Tian H; Wilson DA; Tu Y; Peng F Magnetically Powered Helical Hydrogel Motor for Macrophage Delivery. Appl. Mater. Today 2021, 25, 101197. 10.1016/j.apmt.2021.101197. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (87).Sheridan A; Brown AC Recent Advances in Blood Cell-Inspired and Clot-Targeted Thrombolytic Therapies. J. Tissue Eng. Regen. Med 2023, 2023, 1–14. 10.1155/2023/6117810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (88).Tong X; Pan W; Su T; Zhang M; Dong W; Qi X Recent Advances in Natural Polymer-Based Drug Delivery Systems. React. Funct. Polym 2020, 148, 104501. 10.1016/j.reactfunctpolym.2020.104501. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (89).Xu Y; Kim C-S; Saylor DM; Koo D Polymer Degradation and Drug Delivery in PLGA-Based Drug-Polymer Applications: A Review of Experiments and Theories. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. B Appl. Biomater 2017, 105 (6), 1692–1716. 10.1002/jbm.b.33648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (90).Park K; Skidmore S; Hadar J; Garner J; Park H; Otte A; Soh BK; Yoon G; Yu D; Yun Y; Lee BK; Jiang X; Wang Y Injectable, Long-Acting PLGA Formulations: Analyzing PLGA and Understanding Microparticle Formation. J. Controlled Release 2019, 304, 125–134. 10.1016/j.jconrel.2019.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (91).Cordeiro RA; Serra A; Coelho JFJ; Faneca H Poly(β-Amino Ester)-Based Gene Delivery Systems: From Discovery to Therapeutic Applications. J. Controlled Release 2019, 310, 155–187. 10.1016/j.jconrel.2019.08.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (92).Gregory DA; Taylor CS; Fricker ATR; Asare E; Tetali SSV; Haycock JW; Roy I Polyhydroxyalkanoates and Their Advances for Biomedical Applications. Trends Mol. Med 2022, 28 (4), 331–342. 10.1016/j.molmed.2022.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (93).Philip S; Keshavarz T; Roy I Polyhydroxyalkanoates: Biodegradable Polymers with a Range of Applications. J. Chem. Technol. Biotechnol 2007, 82 (3), 233–247. 10.1002/jctb.1667. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (94).Rodríguez-Contreras A; Canal C; Calafell-Monfort M; Ginebra M-P; Julio-Moran G; Marqués-Calvo M-S Methods for the Preparation of Doxycycline-Loaded Phb Micro- and Nano-Spheres. Eur. Polym. J 2013, 49 (11), 3501–3511. 10.1016/j.eurpolymj.2013.08.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (95).Bartnikowski M; Dargaville TR; Ivanovski S; Hutmacher DW Degradation Mechanisms of Polycaprolactone in the Context of Chemistry, Geometry and Environment. Prog. Polym. Sci 2019, 96, 1–20. 10.1016/j.progpolymsci.2019.05.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (96).Bliley JM; Marra KG Polymeric Biomaterials as Tissue Scaffolds. In Stem Cell Biology and Tissue Engineering in Dental Sciences; Elsevier, 2015; pp 149–161. 10.1016/B978-0-12-397157-9.00013-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (97).Ifkovits JL; Devlin JJ; Eng G; Martens TP; Vunjak-Novakovic G; Burdick JA Biodegradable Fibrous Scaffolds with Tunable Properties Formed from Photo-Cross-Linkable Poly(Glycerol Sebacate). ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2009, 1 (9), 1878–1886. 10.1021/am900403k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (98).Wang Y; Kim YM; Langer R In Vivo Degradation Characteristics of Poly(Glycerol Sebacate). J. Biomed. Mater. Res 2003, 66A (1), 192–197. 10.1002/jbm.a.10534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (99).Rai R; Tallawi M; Grigore A; Boccaccini AR Synthesis, Properties and Biomedical Applications of Poly(Glycerol Sebacate) (PGS): A Review. Prog. Polym. Sci 2012, 37 (8), 1051–1078. 10.1016/j.progpolymsci.2012.02.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (100).Vogt L; Ruther F; Salehi S; Boccaccini AR Poly(Glycerol Sebacate) in Biomedical Applications—A Review of the Recent Literature. Adv. Healthc. Mater 2021, 10 (9), 2002026. 10.1002/adhm.202002026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (101).Boland ED; Coleman BD; Barnes CP; Simpson DG; Wnek GE; Bowlin GL Electrospinning Polydioxanone for Biomedical Applications. Acta Biomater. 2005, 1 (1), 115–123. 10.1016/j.actbio.2004.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (102).Goonoo N; Jeetah R; Bhaw-Luximon A; Jhurry D Polydioxanone-Based Bio-Materials for Tissue Engineering and Drug/Gene Delivery Applications. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm 2015, 97, 371–391. 10.1016/j.ejpb.2015.05.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (103).Day NB; Wixson WC; Shields CW Magnetic Systems for Cancer Immunotherapy. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 2021, 11 (8), 2172–2196. 10.1016/j.apsb.2021.03.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (104).Stepien G; Moros M; Pérez-Hernández M; Monge M; Gutiérrez L; Fratila RM; Las Heras MD; Menao Guillén S; Puente Lanzarote JJ; Solans C; Pardo J; De La Fuente JM Effect of Surface Chemistry and Associated Protein Corona on the Long-Term Biodegradation of Iron Oxide Nanoparticles In Vivo. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2018, 10 (5), 4548–4560. 10.1021/acsami.7b18648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (105).Manzari MT; Shamay Y; Kiguchi H; Rosen N; Scaltriti M; Heller DA Targeted Drug Delivery Strategies for Precision Medicines. Nat. Rev. Mater 2021, 6 (4), 351–370. 10.1038/s41578-020-00269-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (106).Sung Y; Kim S Recent Advances in the Development of Gene Delivery Systems. Biomater. Res 2019, 23 (1), 8. 10.1186/s40824-019-0156-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (107).Esteban-Fernández De Ávila B; Angell C; Soto F; Lopez-Ramirez MA; Báez DF; Xie S; Wang J; Chen Y Acoustically Propelled Nanomotors for Intracellular SiRNA Delivery. ACS Nano 2016, 10 (5), 4997–5005. 10.1021/acsnano.6b01415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]