Abstract

HIV-1 integrase (IN) is an important molecular target for the development of anti-AIDS drugs. A recently FDA-approved second-generation integrase strand transfer inhibitor (INSTI) cabotegravir (CAB, 2021) is being marketed for use in long-duration antiviral formulations. However, missed doses during extended therapy can potentially result in persistent low levels of CAB that could select for resistant mutant forms of IN, leading to virological failure. We report a series of N-substituted bicyclic carbamoyl pyridones (BiCAPs) that are simplified analogs of CAB. Several of these potently inhibit wild-type HIV-1 in single-round infection assays in cultured cells and retain high inhibitory potencies against a panel of viral constructs carrying resistant mutant forms of IN. Our lead compound, 7c, proved to be more potent than CAB against the therapeutically important resistant double mutants E138K/Q148K (>12-fold relative to CAB) and G140S/Q148R (>36-fold relative to CAB). A significant number of the BiCAPs also potently inhibit the drug-resistant IN mutant R263K, which has proven to be problematic for the FDA-approved second-generation INSTIs.

Keywords: HIV-1, bicyclic carbamoyl pyridone (BiCAP), INSTI, cabotegravir, one-pot synthesis, INSTI-resistance, resistant mutants

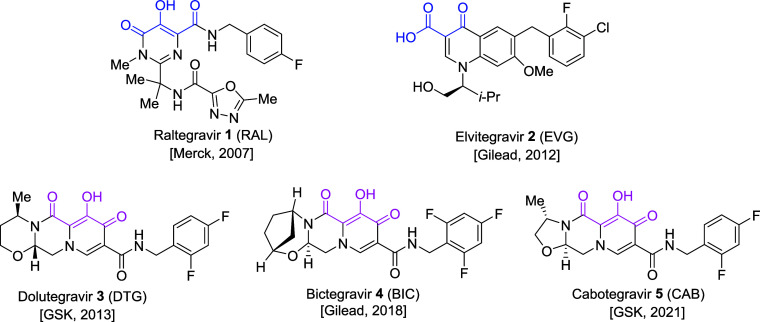

Integrase (IN) is a retroviral enzyme that inserts a linear double-stranded DNA copy of the viral genome into the host genome; this reaction is called integration. Because integration is essential for replication of human immunodeficiency virus-1 (HIV-1), the causative agent of AIDS, IN is an attractive target for the treatment of HIV-1 infections and for pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) that can be used to block new infections.1−3 IN-mediated integration involves two discrete steps, 3′-processing (3′-P) and strand transfer (ST). Agents that bind to IN and specifically block the ST step are known as integrase strand transfer inhibitors (INSTIs).4−9 Currently, approximately 38 million people worldwide are infected with HIV and more than half of these are undergoing some form of treatment with combination antiretroviral therapy (cART). INSTIs are important components of cART formulations.10−13 The first-generation INSTIs raltegravir (RAL, 1) and elvitegravir (EVG, 2) have been superseded by the second-generation INSTIs dolutegravir (DTG, 3), bictegravir (BIC, 4), and cabotegravir (CAB, 5) (Figure 1).10,12,14,15 Treatment with the first-generation INSTIs has led to the emergence of INSTI-resistant mutant forms of IN and, although second-generation INSTIs are less susceptible to the development of resistance than first-generation INSTIs, resistance is a significant problem.13,16−25 Causes of virological failure (VF) for INSTIs are currently an active area of investigation.26 Because of the emergence of resistance to the second-generation INSTIs and the potential for an increased frequency of VF associated with long-acting antiretroviral therapy (LA-ART), it is critical to develop new INSTIs that retain good antiviral efficacy against the known resistant IN mutants.

Figure 1.

Chemical structures of FDA-approved INSTIs with company and year of FDA approval shown in parentheses. Metal-chelating heteroatom triads are highlighted in blue and magenta for the first- and second-generation INSTIs, respectively.

In general, second-generation INSTIs are more effective than the first-generation INSTIs at retaining inhibitory potencies against INSTI-resistant IN mutants.27 However, resistance to the second-generation INSTI, DTG, can result from IN G118R, R263K, and Q148H mutations when these occur in combination with G140S. In single-round infection assays that employ viral constructs with wild-type (WT) IN or mutant INs having resistance mutations, reductions in susceptibility to DTG relative to WT are >5-fold for G118R, 2-fold for R263K, and 2-fold for G140S/Q148H.19,28 Recently, the FDA has approved an injectable formulation of CAB in combination with the non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor (NNRTI) rilpivirine for use in LA-ART. However, if there are adherence issues, these therapies carry an increased risk of breakthrough infection and selection for resistance, due to CAB’s long pharmacokinetic half-life (suboptimal plasma level concentrations can last for several months).23,29,30 The potential for virological failure during CAB therapy arises in part from the fact that this drug has a significant reduction in susceptibility to the IN mutants G118R, R263K, N155H and G140S/Q148H. Close monitoring is recommended to minimize the emergence of drug-resistant mutant forms of IN.31

INSTIs employ a triad of heteroatoms to chelate two catalytic Mg2+ ions in the IN active site (color-highlighted in Figure 1). These interactions are critical for the binding and activity of the drugs. Mutations near the IN active site can alter the Mg2+ ion cluster, which can weaken or reduce the binding of INSTIs.9,32−34 Metal-chelating bicyclic carbamoyl pyridone (BiCAP) motifs were originally developed to address conformational issues of monocyclic compounds.35,36 Second-generation INSTIs elaborate the BiCAP core into more extended tricyclic platforms.12 Structural extensions in second-generation INSTIs enhance the binding interactions within the catalytic site (see Figure 1).12 Here we revisit the BiCAP platform, with a focus on examining the inhibitory potencies of a set of BiCAP analogs against IN-resistant mutants. We refer to our BiCAP-based analogs as INSTIs. We show that mutations in IN affect the potency of the new compounds, strongly implicating that IN is the target, and we explicitly demonstrate that some of the most potent compounds block the ST step of integration. We compare the antiviral data with all three FDA-approved second-generation INSTIs, since there can be large differences in the antiviral potencies of the three INSTIs, particularly against IN double and triple mutants. We found that several BiCAP-based INSTIs display improved inhibitory potencies against a subset of IN mutants when compared to CAB and, in some cases, DTG.15 These data provide insights that will be useful in the search for INSTIs that are more broadly potent against drug-resistant mutants.

Results and Discussion

Rationale

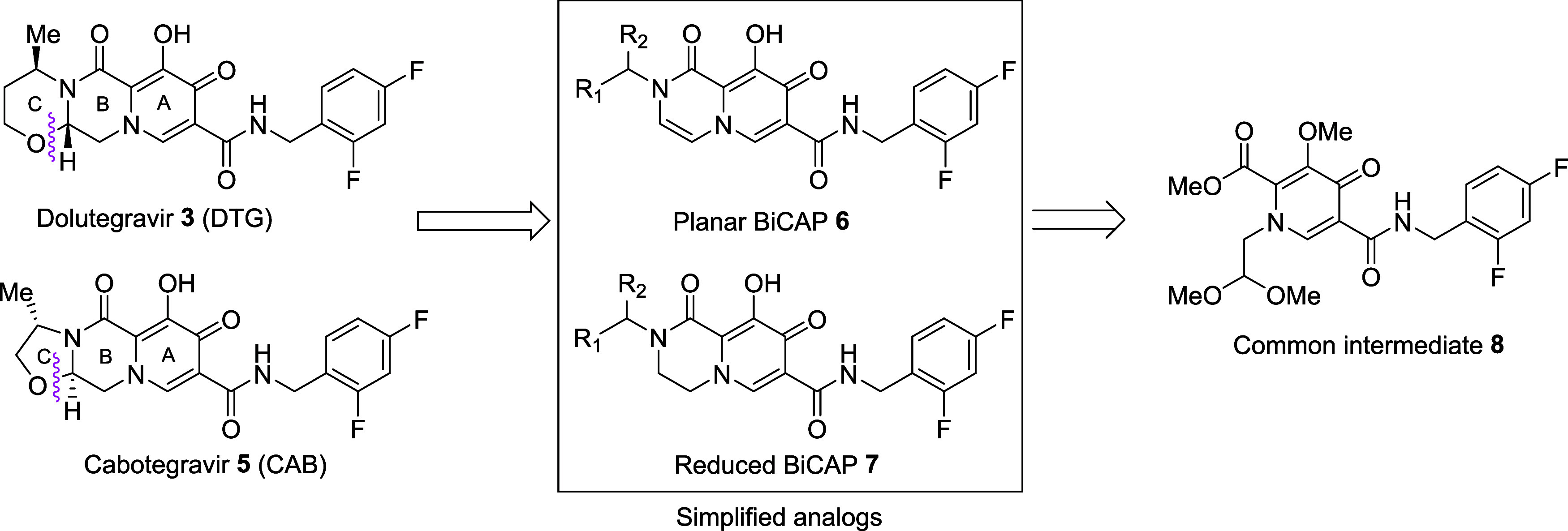

Two Mg2+ ions bound within the IN active site are critical for both the 3′-P and ST reactions. INSTIs chelate the two catalytic Mg2+ ions, displacing the end of the viral DNA and inhibiting the ST reaction.37 Carbamoyl pyridone-based compounds can chelate the Mg2+ ions in the IN active site, blocking the ST reaction. The BiCAP pharmacophore serves as a critical component of all FDA-approved INSTIs.35−38 We have developed a one-pot synthetic methodology that provides facile access to BiCAPs (see39,40 and Supporting Information). We have a long-standing interest in developing bicyclic INSTIs, with a focus on compounds that retain antiviral efficacy against resistant mutant forms of IN.3,40−45 We recently prepared a set of N-substituted BiCAPs of types 6 and 7, that can be derived from a common pyridone-acetal intermediate 8 (Figure 2).40 As we previously reported,40 synthesis of the BiCAPs begins with preparation of the common intermediate pyridone-acetal 8 (Figure 2). Our N-substituted BiCAPs 6b — 6m were synthesized using a three-step one-pot synthetic methodology that relied on the key known/commercially available common pyridone-acetal intermediate 8.40 Using this scheme, synthesis of these BiCAPs does not demand special synthetic reagents and requires only a single purification step, which enhanced overall yields compared to a routine multistep synthesis.40 The corresponding saturated BiCAPs 7b — 7m were obtained by Pd-catalyzed hydrogenation of the double bonds in the ring B of series 6 (see Supporting Information).40 BiCAPs 6 and 7 can be viewed as simplified analogs of DTG (3) and CAB (5) that lack a C ring (Figure 2). The C-ring was introduced into BiCAP-based INSTIs to improve antiviral profiles. The fact that mutations in IN have a major impact on the potencies of the compounds in our antiviral assays indicates that the compounds are blocking HIV replication by interfering with IN function. We also show, using an in vitro integration assay, that the most broadly effective of the new compounds block the strand transfer step of the integration reaction. The interactions of BiCAP-based INSTIs having a C ring have been elucidated in structural studies with simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) and HIV intasomes.33,45,46 Removing the third ring eliminates the stereocenter at the B–C ring junction.40 Additionally, the absence of a C-ring appended to the BiCAPs could potentially provide greater freedom of orientation of the INSTI metal-chelating triad with the two Mg2+ ions in the IN catalytic pocket. The N-alkyl group of the BiCAPs attached to the amide of the ring B provides greater rotational flexibility about the C–N bond than is possible when this functionality is part of a C-ring. This could potentially allow the compound to adjust the orientation around the bond to accommodate changes in the active site arising from mutations in the IN protein. This ability to adjust the orientation may facilitate alterations in ligand binding that could compensate for changes arising from resistant mutations. A similar approach has been used to make broadly effective non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors.47,48

Figure 2.

DTG, CAB, their simplified BiCAP congeners 6 and 7,35,36,40 and the key synthetic precursor 8.39,40

Cellular Cytotoxicities of BiCAPs

In general, INSTIs have little or no cytotoxicity. We measured the cellular cytotoxicities of the BiCAPs in human osteosarcoma (HOS) cells (Table 1). Most compounds showed cellular cytotoxicities (CC50 values) that were below detectable levels: BiCAPs 7a, 6j, 7j, 6k, 7k, 6l, 7l, 6m, and 7m exhibited CC50 values >250 μM (Table 1), which are comparable to the FDA-approved INSTIs. BiCAP 6a exhibited low but detectable cellular cytotoxicity (CC50 > 150 μM, Table 1).

Table 1. Antiviral Potencies in Single-Round Infection Assays Employing Viral Constructs with Wild-Type (WT) IN and IN with INSTI-Resistant Mutations.

| EC50 (nM)b |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| INSTIs | CC50 (μM)a | WT | S230N | G118R | R263K | N155H | G140S/Q148H |

| DTG | >250 | 2.6 ± 0.3 | 7.9 ± 1.3 | 18.4 ± 1.5 | 5.2 ± 0.6 | 3.6 ± 1.3 | 6.4 ± 1.6 |

| BIC | >250 | 2.4 ± 0.4 | 2.6 ± 0.6 | 9.1 ± 1.6 | 4.8 ± 0.8 | 2.7 ± 0.8 | 4.6 ± 0.4 |

| CAB | >250 | 1.8 ± 0.5 | 3.2 ± 0.5 | 35.5 ± 2.1 | 7.1 ± 0.1 | 2.2 ± 0.3 | 23.5 ± 7.2 |

| 6a | 150.2 ± 19.9 | 54.9 ± 3.7 (0.8×) | 84.5 ± 8.7 (1.2×) | 372.3 ± 36.5 (0.7×) | 54.2 ± 2.7 (2.7×) | 457.4 ± 21.0 | >5,000 |

| 7a | >250 | 44.2 ± 3.8 | 103.3 ± 22.8 | 275.8 ± 95.5 | 148.4 ± 36.5 | >5,000 | |

| 6b | 120.8 ± 2.7 | 2.7 ± 0.2 (1.7×) | 7.9 ± 0.9 (0.9×) | 32.0 ± 7.8 (0.6×) | 6.8 ± 0.4 (1.9×) | 275.8 ± 96.7 (0.4×) | |

| 7b | >250 | 4.6 ± 0.7 | 7.4 ± 0.5 | 19.7 ± 1.8 | 12.8 ± 2.2 | 104.1 ± 9.1 | |

| 6c | >250 | 3.8 ± 0.6 (0.8×) | 4.8 ± 0.2 (1×) | 26.7 ± 3.2 (0.7×) | 3.7 ± 0.2 (1.4×) | 4.3 ± 0.3 (0.8×) | 32.6 ± 7.5 (0.8×) |

| 7c | 162.7 ± 8.0 | 3.0 ± 0.1 | 4.7 ± 0.4 | 20.2 ± 1.4 | 5.2 ± 0.8 | 3.6 ± 0.9 | 27.3 ± 5.2 |

| 6d | >250 | 4.8 ± 0.9 (6.6×) | 9.3 ± 1.9 (4.1×) | 69.2 ± 12.0 (1×) | 6.0 ± 0.6 (5.3×) | 19.7 ± 1.7 (1.8×) | 295.3 ± 19.0 (1×) |

| 7d | >250 | 31.7 ± 3.8 | 38.0 ± 3.8 | 67.7 ± 11.7 | 32.2 ± 2.5 | 35.9 ± 1.1 | 300.0 ± 9.5 |

| 6e | >250 | 10.8 ± 1.7 (5×) | 15.4 ± 0.3 (6.3×) | 329.1 ± 18.5 (0.7×) | 16.1 ± 1.0 (5.9×) | 33.3 ± 8.8 (2×) | 626.3 ± 92.5 (1.9×) |

| 7e | 149.9 ± 3.9 | 54.5 ± 3.0 | 97.0 ± 16.9 | 242.7 ± 34.8 | 95.7 ± 12.7 | 66.9 ± 14.0 | 1200.3 ± 120.2 |

| 6f | >250 | 16.6 ± 2.0 (4. 6×) | 30.7 ± 1.4 (3.3×) | 75.4 ± 9.1 (12.8×) | 20.6 ± 1.3 (5.3×) | 45.5 ± 8.3 (6.8×) | 426.0 ± 35.8 (2.6×) |

| 7f | >250 | 75.7 ± 7.4 | 100.8 ± 17.5 | 963.8 ± 120.7 | 110.1 ± 17.3 | 310.7 ± 29.8 | 1100.7 ± 11.2 |

| 6g | >250 | 4.8 ± 0.2 (1×) | 6.3 ± 0.4 (1.3×) | 33.5 ± 4.7 (0.5×) | 5.0 ± 0.2 (1.9×) | 15.0 ± 1.6 (0.5×) | 253.4 ± 23.4 (0.5×) |

| 7g | >250 | 4.6 ± 0.4 | 8.8 ± 0.9 | 15.6 ± 4.1 | 9.4 ± 1.4 | 6.9 ± 0.5 | 122.6 ± 5.4 |

| 6h | >250 | 2.0 ± 0.2 (2×) | 4.6 ± 0.4 (1.4×) | 85.9 ± 7.9 (0.7×) | 2.6 ± 0.1 (3.3×) | 8.2 ± 1.3 (0.8×) | 129.2 ± 19.5 (1.5×) |

| 7h | 210.9 ± 3.0 | 4.0 ± 0.7 | 6.6 ± 0.3 | 65.0 ± 10.3 | 8.6 ± 0.6 | 6.9 ± 1.0 | 190.9 ± 15.1 |

| 6i | >250 | 1.9 ± 0.4 (2.0×) | 4.5 ± 0.6 (1.7×) | 47.5 ± 2.0 (0.3×) | 3.9 ± 0.8 (1.4×) | 11.9 ± 2.3 (0.5×) | 793.1 ± 27.1 (0.5×) |

| 7i | 138.5 ± 8.5 | 3.9 ± 0.5 | 7.8 ± 0.5 | 15.8 ± 2.2 | 5.5 ± 0.4 | 6.5 ± 1.0 | 430.6 ± 36.7 |

| 6j | >250 | 4.2 ± 1.0 (1.4×) | 7.7 ± 0.3 (1.7×) | 46.7 ± 4.1 (1.2×) | 6.8 ± 0.4 (0.9×) | 12.6 ± 1.2 (0.8×) | 442.9 ± 2.7 (0.4×) |

| 7j | >250 | 6.0 ± 1.2 | 12.8 ± 3.7 | 55.3 ± 3.6 | 6.5 ± 1.2 | 10.0 ± 0.7 | 168.5 ± 17.1 |

| 6k | >250 | 1.7 ± 0.1 (2.1×) | 3.0 ± 0.3 (4.8×) | 21.5 ± 1.3 (1.0×) | 2.8 ± 0.3 (4.5×) | 5.0 ± 0.7 (1×) | 34.1 ± 5.4 (1.0×) |

| 7k | >250 | 3.6 ± 0.1 | 14.4 ± 3.2 | 22.1 ± 3.7 | 12.6 ± 0.7 | 5.0 ± 0.9 | 34.4 ± 1.7 |

| 6l | >250 | 3.3 ± 0.3 (2×) | 5.2 ± 0.7 (1.6×) | 103.1 ± 2.9 (0.3×) | 4.4 ± 0.2 (1.2×) | 27.7 ± 2.7 (0.2×) | 1153.7 ± 113.5 (0.3×) |

| 7l | >250 | 6.5 ± 0.9 | 8.6 ± 1.2 | 36.4 ± 1.3 | 5.7 ± 0.9 | 6.3 ± 0.7 | 394.2 ± 39.0 |

| 6m | >250 | 38.9 ± 6.7 (0.5×) | 201.7 ± 11.7 (0.2×) | 164.8 ± 5.4 (0.6×) | 122.5 ± 5.5 (0.5×) | 81.6 ± 7.6 (0.3×) | 364.7 ± 43.3 (0.3×) |

| 7m | >250 | 21.4 ± 2.5 | 41.8 ± 4.2 | 102.7 ± 13.3 | 68.2 ± 8.0 | 25.6 ± 4.2 | 109.1 ± 20.5 |

CC50 values, which are the concentrations resulting in 50% reduction in the level of ATP in human osteosarcoma (HOS) cells, are given.

EC50 values were obtained from the cells infected with single-round HIV-1 vectors with indicated mutant. CC50 and EC50 values for of 6b–6i and 7b–7i have been previously reported.40 Antiviral activities have been previously reported for 6d–6f and 7d–7f against the S230N mutant.40 (× = 7/6 potency ratio) indicates the fold difference in antiviral potencies of the planar BiCAP 6 compared to the corresponding reduced BiCAP 7. “—” indicates not tested.

Antiviral Potencies of BiCAPs in Single-Round Infection Assays Employing Viral Constructs with WT IN

We determined antiviral EC50 values of the new BiCAPs in single-round infection assays employing WT IN.48 We compared the values for our newly synthesized BiCAPs 6a, 6j–6m, and 7a, 6j–6m with several previously studied BiCAP-based INSTIs (6b–6i and 7b–7i)40 and all three FDA-approved second-generation INSTIs (Table 1). The EC50 values of the new BiCAPs, 6j (4.2 ± 1.0 nM), 6k (1.7 ± 0.1 nM), 7k (3.6 ± 0.1 nM), and 6l (3.3 ± 0.3 nM) were comparable to the FDA-approved INSTIs DTG (2.6 ± 0.3 nM), BIC (2.4 ± 0.4 nM), and CAB (1.8 ± 0.5 nM). The BiCAPs 7j (6.0 ± 1.2 nM) and 7l (6.5 ± 0.9 nM) showed slightly lower antiviral potencies, while the remaining BiCAPs 6a, 7a, 6m, and 7m displayed EC50 values >20.0 nM (Table 1).

Antiviral Potencies of BiCAPs in Single-Round Infection Assays Using Viral Constructs Having INSTI-Resistant Mutant Forms of IN

S230N

HIV can develop resistance to all classes of antivirals; INSTIs are not an exception.3 Certain IN-resistant mutants are readily selected by the first-generation INSTIs, RAL and EVG, both in cultured cells infected with HIV and in people living with HIV-1 (PLWH). The second-generation INSTIs, DTG and BIC, are less susceptible to the development of resistance compared to first-generation INSTIs. However, resistance can still arise both in vitro and in PLWH.28 The IN mutant S230N has been selected in vitro by the early Merck INSTI L810,830.44,49 We recently reported the antiviral potencies of a subset of our BiCAPs in single-round infection assays that employed viral constructs containing IN with the S230N mutation (Table 1).40 In this assay, DTG and CAB showed antiviral potencies of EC50 = 7.9 ± 1.3 and 3.2 ± 0.5 nM, respectively; BIC retained more antiviral potency (2.6 ± 0.6 nM; Table 1). BiCAPs 6c (4.8 ± 0.2 nM), 6g (6.3 ± 0.4 nM), 6h (4.6 ± 0.4 nM), 6i (4.5 ± 0.6 nM), 6k (3.0 ± 0.3 nM), 6l (5.2 ± 0.7 nM), 7c (4.7 ± 0.4 nM), and 7h (6.6 ± 0.3 nM) showed potencies similar to the FDA-approved second-generation INSTIs. However, several of the compounds (6a, 6f, 6m,7a, 7d, 7e, 7f, and 7m) showed reduced antiviral potencies with EC50 values >30.0 nM (Table 1).

G118R

The G118R mutant was initially identified in selection studies using MK-2048.50 This mutant has been selected frequently in PLWH during initial DTG treatments, and it is considered to be a major IN resistant mutant for DTG.51−56 G118R has been shown to cause significant resistance (17×) against CAB in our single-round infection assays. Although CAB is generally more susceptible to losing inhibitory potency against resistant mutants than DTG or BIC, both DTG and BIC lose potency against the G118 R mutant (9× and 4×, respectively). In our single-round infection assays, neither the BiCAPs 6a–6m nor 7a–7m retained full antiviral potency against the G118R mutant (Table 1). However, compounds 7b (19.7 ± 1.8 nM), 7g (15.6 ± 4.1 nM), and 7i (15.8 ± 2.2 nM) retained moderate antiviral potencies that were similar to DTG (18.4 ± 1.5 nM). BICAPs 6c (26.7 ± 3.2 nM), 7c (20.2 ± 1.4 nM), 6k (21.5 ± 1.3 nM), and 7k (22.1 ± 3.7 nM) also showed antiviral potencies against this mutant that were better than CAB (35.5 ± 2.1 nM). The remaining BiCAPs (6a, 7a, 6b, 6d, 7d, 6e, 7e, 6f, 7f, 6g, 6h, 7h, 6i, 6j, 7j, 6l, 7l, 7m, and 7m) showed antiviral EC50 values that were greater than 33.0 nM. Overall antiviral potencies for the saturated congeners (7) were equivalent to or greater than the potencies shown by the unsaturated analogs (6), being 7f being the exception (Table 1).

R263K

The R263K mutant has been selected by DTG in vitro and, to a lesser extent, in PLWH. This mutant had a reduced susceptibility to DTG in single-round infection assays.18,27,57−60 Both the G118R and the R263K mutants have been observed in the same patients receiving ART that involves DTG, notably in a patient infected with HIV-1 subtype F.51,61−63 In our current assays, the R263K mutant showed a very slight reduction in potency to DTG (5.2 ± 0.6 nM), and to CAB (7.1 ± 0.1 nM), while BIC retained good potency (4.8 ± 0.8 nM). The BiCAPs 6c (3.7 ± 0.2 nM), 6h (2.6 ± 0.1 nM), 6i (3.9 ± 0.8 nM), and 6k (2.8 ± 0.3 nM) displayed antiviral potencies against this mutant that were similar to BIC and improved when compared to DTG (p values <0.05). These compounds, along with 7i (5.5 ± 0.4 nM) and 6l (4.4 ± 0.2 nM), showed improved antiviral potencies relative to CAB (p values ≤0.01). Compounds 7c (5.2 ± 0.8 nM) and 6d (6.0 ± 0.6 nM) exhibited a slight improvement in potency compared to CAB (p values <0.05). Against this mutant, BiCAPs 6h and 6k stood out as being the best of the series (Table 1). BiCAPs 6b (6.8 ± 0.4 nM), 7b (12.8 ± 2.2 nM), 6e (16.1 ± 1.0 nM), 7g (9.4 ± 1.4 nM), 7h (8.6 ± 0.6 nM), 6j (6.8 ± 0.4 nM), 7j (6.5 ± 1.2 nM), 7k (12.6 ± 0.7 nM), and 7l (5.7 ± 0.9 nM) displayed potencies that were similar to DTG and CAB against the R263K mutant. The remaining compounds, 6a (54.2 ± 2.7 nM), 7a (184.4 ± 36.5 nM), 7d (32.2 ± 2.5 nM), 7e (95.7 ± 12.7 nM), 6f (45.5 ± 8.3 nM), 7f (110.1 ± 17.3 nM), 6m (122.5 ± 5.5 nM), and 7m (68.2 ± 8.0 nM) showed larger reductions in potencies (Table 1). Compound 6h was the best in terms of retaining antiviral potency. This compound can be viewed as a simplified analog of DTG lacking an α-methyl group and it can also be considered as a simplified analog of CAB with an α-methyl. In general, members of the unsaturated series of analogs (7) were more potent against the R263K mutant than their saturated congeners (6).

N155H

The N155H mutation is commonly selected by first-generation INSTIs.22 This mutant has also been selected in DTG monotherapy clinical trials.64 BiCAPs 6c (4.3 ± 0.3 nM), 7c (3.6 ± 0.9 nM), 7g (6.9 ± 0.5 nM), 7h (6.9 ± 1.0 nM), 7i (6.5 ± 1.0 nM), 6k (5.0 ± 0.7 nM), 7k (5.0 ± 0.9 nM), and 7l (6.3 ± 1.7 nM) retained high antiviral potencies against the N155H mutant. The antiviral potencies of 6c (4.3 ± 0.3 nM) and 7c (3.6 ± 0.9 nM) were equivalent to those displayed by the second-generation INSTIs DTG (3.6 ± 1.3 nM), BIC (2.7 ± 1.0 nM), and CAB (2.2 ± 0.3 nM) (Table 1). Compounds 6d (19.7 ± 1.7 nM), 6g (15.0 ± 1.6 nM), 6i (11.9 ± 2.3 nM), 6j (12.6 ± 1.2 nM), and 7j (10.0 ± 0.7 nM) exhibited moderate losses in potency, while the remaining BiCAPs were less effective against this mutant, with EC50 values >25.0 nM (Table 1).

G140S/Q148H Double Mutant

The antiviral potency of INSTIs against the G140S/Q148H double mutant is important for establishing whether a compound merits further exploration.28,34 This IN double mutant causes a high level of resistance to CAB and the first-generation INSTIs.65,66 In single-round infection assays, this mutant caused a majority of our BiCAPs to lose significant potency when compared to DTG (6.4 ± 1.6 nM) and BIC (4.6 ± 0.4 nM, Table 1). These results agree with the antiviral data previously seen with the truncated analog 7b which lacks the C ring, and was 8-fold less effective against the IN mutant G140S/Q148H.33 In the data we report here, we saw approximately an 17-fold reduction of potency of 7b as compared to DTG and 4-fold loss relative to CAB. However, BiCAPs 6c (32.6 ± 7.5 nM), 7c (27.3 ± 5.2 nM), 6k (34.1 ± 5.4 nM), and 7k (34.4 ± 1.7 nM) were not significantly different in antiviral potencies against this double mutant compared to CAB (23.5 ± 7.2 nM) (Table 1). Other members of the current series of compounds exhibited significantly greater losses of inhibitory potencies (EC50 values >100.0 nM). BiCAPs 6a and 7a, which lack N-substituents, were essentially inactive (EC50 > 5000 nM, Table 1). Based on cryo-EM structures of simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) intasome-bound INSTIs, it has been suggested that the addition of a third ring onto the BiCAP platform should enhance binding interactions, in part by providing contacts with β4α2 loop proximal to the catalytic site. This is reflected in a more rapid off-rate for BiCAP inhibitor 6b as compared to DTG in studies with HIV-1 intasomes bearing the Q148H/G140S mutations.33 Thus, the loss of antiviral potencies of the simplified BiCAPs in the current series against the double mutant is not unexpected. Based on the antiviral potencies against the panel of single and double mutants, compounds 6c and 7c were the most effective, having antiviral potencies similar to CAB (Figure 3). These compounds were chosen for further study against a more extensive panel of IN double and triple mutants.

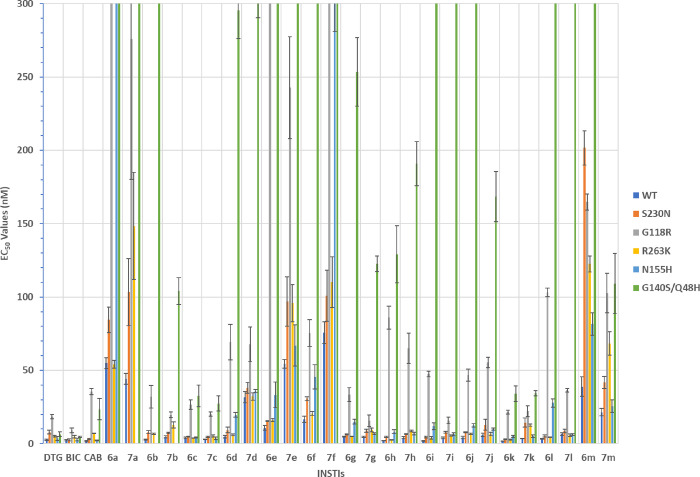

Figure 3.

Antiviral potencies of INSTIs in single-round infection assays employing HIV vectors with WT HIV-1 and with IN mutants S230N, G118R, R263K, N155H, and G140S/Q148H. The potencies of DTG, BIC, and CAB have been previously reported.46 Previously reported data are shown to facilitate comparison with the data for the new compounds. Error bars represent the standard deviations of independent experiments, n = 4, performed in triplicate. EC50 values shown in the graph have a maximum value of 300 nM.

Antiviral Potencies Against a Panel of Selected Double and Triple IN Mutants

Because of the importance of long-acting formulations for both maintenance therapies and for prophylaxis, we were particularly interested in comparing our new compounds to CAB. In order to differentiate 6c and 7c from CAB, we determined antiviral potencies against a select panel of double and triple IN mutants that we previously showed to lose susceptibility to the FDA-approved INSTIs (Table 2 and Figure 4). This panel of IN mutants includes E138K/Q148K, G140A/Q148K, G140S/Q148R, L74M/G140C/Q148R, T97A/G140S/Q148H, E138A/G140S/Q148H, E138K/G140A/Q138K, E138K/G140C/Q148R, and E138K/G140S/Q148H.28

Table 2. Comparison between CAB and 6c and 7c Against Complex IN Mutants.

|

EC50(nM)i |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| IN mutants | CAB | 6c | 7c |

| E138K/Q148K | 772.1 ± 72.2 | 56.1 ± 8.9 (13.9×) | 62.5 ± 8.0 (12.4×) |

| G140A/Q148K | 393.1 ± 51.1 | 207.5 ± 61.2 (1.9×) | 242.9 ± 55.6 (1.6×) |

| G140S/Q148R | 414.6 ± 14.5 | 15.3 ± 1.0 (27.1×) | 11.3 ± 0.7 (36.3×) |

| L74M/G140C/Q148R | 220.3 ± 41.2 | 157.5 ± 22.1 (1.4×) | 101.5 ± 5.5 (2.2×) |

| T97A/G140S/Q148H | 43.7 ± 4.2 | 260.1 ± 48.2 (0.2×) | 103.2 ± 12.4 (0.4×) |

| E138A/G140S/Q148H | 70.2 ± 9.0 | 146.7 ± 15.4 (0.5×) | 95.9 ± 9.8 (0.7×) |

| E138K/G140A/Q148K | 610.3 ± 8.6 | 380.9 ± 20.3 (1.6×) | 391.2 ± 22.7 (1.5×) |

| E138K/G140C/Q148R | 134.2 ± 0.3 | 56.1 ± 6.9 (2.4×) | 54.2 ± 11.9 (2.5×) |

| E138K/G140S/Q148H | 93.0 ± 6.1 | 206.6 ± 5.5 (0.5×) | 92.3 ± 3.3 (1×) |

EC50 values were obtained from the cells infected with lentiviral vectors as with indicated mutant. Values in parentheses equal the fold-ratio of antiviral potency relative to CAB.

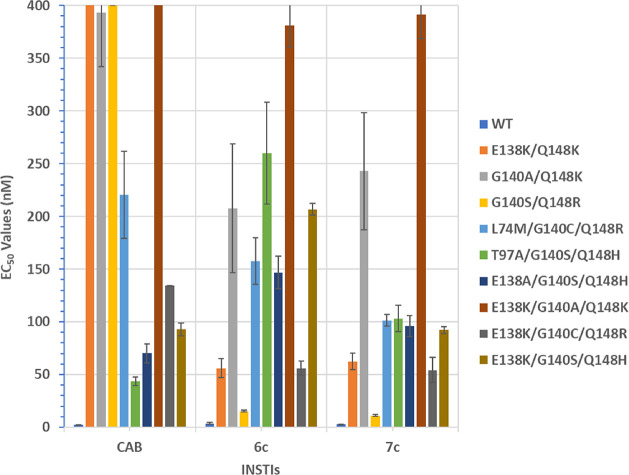

Figure 4.

Antiviral potencies of BiCAPs against a panel of selected IN double and triple mutants. EC50 values were determined using a vector that carries the IN mutant in a single-round infection assay. Error bars represent the standard deviations of independent experiments, n = 4, the assays were performed in triplicate in each experiment. The EC50 values shown in the graph have a maximum value of 400 nM.

When compared to CAB, 6c and 7c exhibited improved antiviral profiles across the panel of mutants. Both 6c and 7c had better efficacies against E138K/Q148K (56.1 ± 8.9 nM and 62.5 ± 8.0 nM, respectively; p values <0.001) than CAB (772.1 ± 72.2 nM). Additional significant improvements in antiviral potencies were observed for 6c and 7c against G140S/Q148R (15.3 ± 1.0 nM and 11.3 ± 0.7 nM, respectively; 414.6 ± 14.5 nM for CAB; p values <0.001), L74M/G140C/Q148R (157.5 ± 22.1 nM and 101.5 ± 5.5 nM, respectively; 220.3 ± 41.2 nM for CAB; p values <0.05), E138K/G140A/Q148K (380.9 ± 20.3 nM and 391.2 ± 22.7 nM, respectively; 610.3 ± 8.6 nM for CAB; p values <0.001), and E138K/G140C/Q148R (56.1 ± 6.9 nM and 54.2 ± 11.9 nM, respectively; 134.2 ± 0.3 nM for CAB; p values <0.001). CAB did display improved potencies against T97A/G140S/Q148H (43.7 ± 4.2 nM; for 6c and 7c, 260.1 ± 48.2 nM and 103.2 ± 12.4 nM, respectively, and p values <0.01) and E138A/G140S/Q148H (70.2 ± 9.0 nM; for 6c and 7c, 146.7 ± 15.4 nM and 95.9 ± 9.8 nM, respectively, with p values <0.01). Both CAB and 7c displayed similar efficacies against E138K/G140S/Q148H (93.0 ± 6.1 nM and 92.3 ± 3.3 nM, respectively), which were improved relative to 6c (206.6 ± 5.5 nM; p values <0.001). Overall, BiCAP 7c exhibited the best profile of antiviral potencies across this panel when compared to 6c and CAB (Table 2 and Figure 4).

In Vitro Integration Activities of CAB, 6c, and 7c

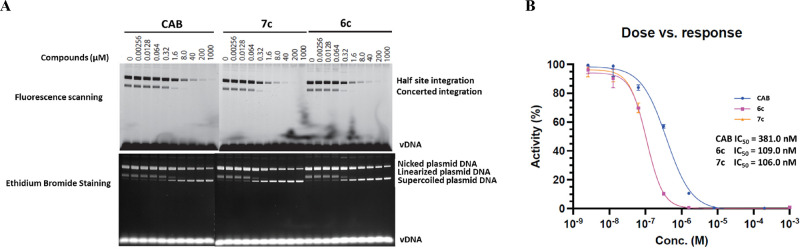

The data obtained with the viral assays, which showed that mutations in IN affected the potency of the compounds show that the compounds target IN. To show that, as expected, the compounds are acting as INSTIs, we tested and compared the abilities of CAB, 6c, and 7c to inhibit two-ended integration of viral DNA in an in vitro strand transfer assay using double-stranded DNA that mimics the ends of HIV-1 DNA. Both 6c and 7c potently inhibited the IN-strand transfer reaction (Figure 5A). When compared to CAB, both 6c and 7c showed an ∼4-fold more potent inhibition of the IN-strand transfer reaction. The relative potencies of the compounds could be extracted and extrapolated from the IN-strand transfer reactions (Figure 5B). Both 6c (109.0 nM) and 7c (106.0 nM) had potencies that were better than CAB (381.0 nM) by ∼4-fold. We note that the concentration of INSTI required to decrease integration product formation by 50%, relative to the amount of product produced in the absence of drug, is substantially greater than the EC50 values measured in the cell culture assays. This is due to limitations of the in vitro assay system. In vitro reactions require concentrations of integrase and viral DNA ends that are substantially higher than the EC50 of INSTIs. Thus, the concentration of complexes of integrase and viral DNA ends is expected to be sufficiently high to reduce the free concentration of INSTI. In contrast, in a viral infection there is only a single pair of viral DNA ends per infecting virion, so binding of INSTI does not affect the free INSTI concentration. Thus, the in vitro assays establish that the ST reaction is the target, but caution is required in interpreting the quantitation.

Figure 5.

In vitro enzymatic activities of CAB, 6c, and 7c. (A) Half site and concerted integrations were determined for CAB, 6c, and 7c using serial dilutions ranging from 0.00256 to 1000 μM as shown above the lanes. The IN-strand transfer reaction products were separated by agarose gel electrophoresis and visualized by both fluorescence scanning and ethidium bromide staining as indicated. The bands corresponding to the half site integration and concerted integration products are indicated on the fluorescence-scanned gels and the nicked plasmid DNA, linearized plasmid DNA, or supercoiled plasmid DNA are shown on the ethidium bromide-stained gels. (B) Using the data from the fluorescence-scanned gel, densitometry was used to generate the dose response curves to determine the potency of the inhibition (nM). The curves for CAB (blue marked with circles), 6c (magenta marked with squares), and 7c (orange marked with triangles) are indicated.

Conclusions

INSTIs are among the leading therapeutics being used to treat HIV-1 infections and in pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) to reduce HIV-1 transmission. Resistance can develop against all antivirals, and resistance is a problem for first-generation INSTIs. Although second-generation INSTIs have better resistance profiles than first-generation INSTIs, resistance can still arise against even the best INSTIs. Thus, there is a need to develop new INSTIs that retain better antiviral efficacies against emerging mutants. CAB, which is used in long-acting formulations is, of the second generation INSTIs, the most susceptible to resistance mutations. Given the importance of long-acting formulations both for PrEP and treatments, developing long-acting compounds/formulations that are less susceptible to resistance mutations is particularly important.

The central role played by metal chelation is reflected in the importance of the chelating structures in the development of INSTIs. A diverse set of metal-chelating structures have been tested, which has resulted in the adoption of the BiCAP motif in all FDA-approved second-generation INSTIs. Initially, the addition of cyclic structures “to the left” of the BiCAP motif was done empirically. In our current paper, we have examined the effects of appending open-chain functionalities on the left side of the BiCAP core that represent simplified versions of the cyclic structures found in the FDA-approved INSTIs. Compounds 6c, 7c, and 6k proved to be the most promising BiCAPs in the current series. These analogs retained good antiviral potencies against prominent INSTI-resistant single IN mutants. Importantly, certain BiCAPs displayed significant inhibitory potencies against the key R263K resistant mutant.

When these compounds were tested against a panel of IN double and triple mutants, both 6c and 7c had improved antiviral profiles relative to CAB. The open-chain N-substituents attached to the amide of ring B of our BiCAPs replace the cyclic structures of second-generation FDA-approved INSTIs. The greater conformational flexibility of the linear constructs may allow subtle differences in the binding of 6c and 7c as compared to CAB.46 Although the pathways and mechanisms that give rise to resistance to second-generation INSTIs are still being defined,46 it is possible that increasing the ability of INSTIs to adapt their conformations and orientations within the active site might help the compounds to accommodate to changes in the IN active site induced by resistance mutations. NNRTIs that use this type of adaptive binding to a drug target whose structure is altered have better retention of antiviral potency against drug resistant reverse transcriptase mutants.67−69 In spite of the fact that antiviral profiles of the current set of simplified BiCAPs do not exhibit significant improvements when compared to BIC and DTG, particularly against the IN mutants G118R and G140S/Q148H, they do advance our understanding of roles played by the third “C” ring in overcoming resistance against these important mutants. The information we present should help guide future INSTI design.

Methods

Determination of Antiviral Potencies and Cellular Cytotoxicities

Human embryonic kidney cell culture cell line 293 was acquired from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC). The human osteosarcoma cell line, HOS, was obtained from Dr. Richard Schwartz (Michigan State University, East Lansing, MI) and grown in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) supplemented with 5% (v/v) fetal bovine serum, 5% newborn calf serum, and penicillin (50 units/mL) plus streptomycin (50 μg/mL; Quality Biological, Gaithersburg, MD). The construction of IN mutants G118R, N155H, S230N, R263K, and G140S/Q148H have been previously described.47 Single round infection assays to determine the EC50 values and cellular cytotoxicity assays to determined CC50 values are briefly described here. On the day prior to transfection, 293 cells were plated on 100 mm-diameter dishes at a density of 1.5 × 106 cells per plate. 293 cells were transfected with 16 μg of pNLNgoMIVR–ΔLUC and 4 μg of pHCMV-g (obtained from Dr. Jane Burns, University of California, San Diego) using the calcium phosphate method. At approximately 6 h after the calcium phosphate precipitate was added, 293 cells were washed twice with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and incubated with fresh media for 48 h. The virus-containing supernatants were then harvested, clarified by low-speed centrifugation, filtered, and diluted for preparation in antiviral infection assays. On the day prior to the screen, HOS cells were seeded in a 96-well luminescence cell culture plate at a density of 4000 cells in 100 μL per well. On the day of the screen for cellular cytotoxicity determination, cells were treated with compounds from a concentration range of 250 μM to 0.05 μM and then incubated at 37 °C for 48 h. On the day of the screen for antiviral activity infection assays, cells were treated with compounds from a concentration range of 5 μM to 0.0001 μM using 11 serial dilutions and then incubated at 37 °C for 3 h. After compound incorporation and activation in the cell, 100 μL of virus-stock (WT or mutant) diluted to achieve a luciferase signal between 0.2 and 1.5 Relative Luciferase Units (RLUs) was added to each well and further incubated at 37 °C for 48 h. Cellular cytotoxicity was measured by using the ATP Lite Luminescence detection system and monitored by adding 100 μL of reconstituted Luminescence ATP detection assay reagent to all wells except for the negative control/background wells, the plates were mixed at 700 rpm at room temperature for 2 min using a compact thermomixer, incubated at room temperature for 20 min to allow time for signal development, and finally cytotoxicity was determined using the microplate reader. Infectivity was measured by using the Steady-lite plus luminescence reporter gene assay system (PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA). Luciferase activity was measured by adding 100 μL of Steady-lite plus buffer (PerkinElmer) to the cells, incubating at room temperature for 20 min, and measuring luminescence using a microplate reader. Both cytotoxicity and antiviral activity were normalized to the cellular cytotoxicity and infectivity in cells that did not receive the target compounds, respectively. KaleidaGraph (Synergy Software, Reading, PA) was used to perform nonlinear regression analysis on the data. EC50 and CC50 values were determined from the fit model.48

In Vitro IN Strand Transfer Assay46

Briefly, Sso7d IN (3 μM) and 1.0 μM viral DNA substrate were preincubated on ice in 20 mM Hepes (pH 7.5), 25% glycerol, 10 mM DTT, 5 mM MgCl2, 4 μM ZnCl2, 50 mM 3-(Benzyldimethyl-ammonio) propanesulfonate (Sigma), and 100 mM NaCl in a 20 μL reaction volume. The vDNA (Integrated DNA Technologies) was fluorescently labeled with a 6-carboxyfluorescein (6-FAM) fluorophore attached to the 5′-end of the precut oligonucleotide, yielding Fam-AGCGTGGGCGGGAAAATCTCTAGCA, which was annealed with 5′-ACTGCTAGAGATTTTCCCGCCCACGCT-3′ to form the precut vDNA substrate. Three hundred nanograms of target plasmid DNA pGEM-9zf was then added and the reaction was initiated by transfer to 37 °C and incubated for 2 h. The integration reactions were stopped by addition of SDS and EDTA to 0.2% and 10 mM, respectively, together with 5 μg of proteinase K and further incubated at 37 °C for a further 30 min. The DNA was then recovered by ethanol precipitation and subjected to electrophoresis in a 1.5% agarose gel in 1× tris-boric acid–EDTA buffer. DNA was visualized either by ethidium bromide staining or by fluorescence using a Typhoon 8600 fluorescence scanner (GE Healthcare).

To generate the dose response curves, the density of the bands corresponding to concerted integration on fluorescence-scanned gels was quantified by using ImageQuant (GE Healthcare). The ST activity of IN with compound omitted was set to 100%, and the activity with compound is presented as a percentage of that without compound. Prism (GraphPad) was used to generate the dose response curves.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsinfecdis.3c00525.

Synthetic details and NMR spectra of the synthesized compounds (PDF)

Author Contributions

∥ P.S.M. and S.J.S. contributed equally to this work. P.S.M., S.J.S., X.Z.Z., S.H.H., and T.R.B. contributed to the design of the compounds, P.S.M. synthesized compounds, S.J.S. performed all antiviral potency evaluation, S.J.S., M.L., and R.C. evaluated IN strand transfer activity, and all authors contributed to analysis of the data.

Authors acknowledge the funding from the NIH Intramural Program, Center for Cancer Research, National Cancer Institute (ZIA BC 007363 and Z01 BC 007333), the Intramural Program of the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases to R.C., and by grants from the Intramural AIDS Targeted Antiviral Program (IATAP). P.S.M. thanks the NIH for the award of 2023 Intramural AIDS Research Fellowship.

The authors declare the following competing financial interest(s): aspects of the reported research may be covered in pending patent applications.

Notes

Original biological data has been deposited at https://doi.org/10.25833/kwk9-t563.

Supplementary Material

References

- Lesbats P.; Engelman A. N.; Cherepanov P. Retroviral DNA Integration. Chem. Rev. 2016, 116, 12730–12757. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.6b00125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pommier Y.; Johnson A. A.; Marchand C. Integrase Inhibitors to Treat HIV/AIDS. Nat. Rev. Drug Discovery 2005, 4, 236–248. 10.1038/nrd1660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith S. J.; Zhao X. Z.; Passos D. O.; Lyumkis D.; Burke T. R. Jr.; Hughes S. H. Integrase Strand Transfer Inhibitors are Effective Anti-HIV drugs. Viruses 2021, 13, 205. 10.3390/v13020205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawasuji T.; Fuji M.; Yoshinaga T.; Sato A.; Fujiwara T.; Kiyama R. A Platform for Designing HIV Integrase Inhibitors. Part 2: A Two-metal Binding Model as a Potential Mechanism of HIV Integrase Inhibitors. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2006, 14, 8420–8429. 10.1016/j.bmc.2006.08.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johns B. A.; Svolto A. C. Advances in Two-metal Chelation Inhibitors of HIV Integrase. Expert Opin. Ther. Pat. 2008, 18, 1225–1237. 10.1517/13543776.18.11.1225. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bacchi A.; Carcelli M.; Compari C.; Fisicaro E.; Pala N.; Rispoli G.; Rogolino D.; Sanchez T. W.; Sechi M.; Neamati N. HIV-1 IN Strand Transfer Chelating Inhibitors: A Focus on Metal Binding. Mol. Pharmaceutics 2011, 8, 507–519. 10.1021/mp100343x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bacchi A.; Carcelli M.; Compari C.; Fisicaro E.; Pala N.; Rispoli G.; Rogolino D.; Sanchez T. W.; Sechi M.; Sinisi V.; Neamati N. Investigating the Role of Metal Chelation in HIV-1 Integrase Strand Transfer Inhibitors. J. Med. Chem. 2011, 54, 8407–8420. 10.1021/jm200851g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engelman A. N. Multifaceted HIV Integrase Functionalities and Therapeutic Strategies for their Inhibition. J. Biol. Chem. 2019, 294, 15137–15157. 10.1074/jbc.REV119.006901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jozwik I. K.; Passos D. O.; Lyumkis D. Structural biology of HIV Integrase Strand Transfer Inhibitors. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2020, 41 (9), 611–626. 10.1016/j.tips.2020.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menendez-Arias L.; Delgado R. Update and Latest Advances in Antiretroviral Therapy. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2022, 43, 16–29. 10.1016/j.tips.2021.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisinger R. W.; Lerner A. M.; Fauci A. S. Human Immunodeficiency Virus/AIDS in the Era of Coronavirus Disease 2019: A Juxtaposition of 2 Pandemics. J. Infect. Dis. 2021, 224, 1455–1461. 10.1093/infdis/jiab114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taoda Y.; Sugiyama S.; Seki T. New Designs for HIV-1 Integrase Inhibitors: A Patent Review (2018-present). Expert Opin. Ther. Pat. 2023, 33, 51–66. 10.1080/13543776.2023.2178300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey A. J.; Rhee S. Y.; Shafer R. W. Integrase Strand Transfer Inhibitor Resistance in Integrase Strand Transfer Inhibitor-Naive Persons. AIDS Res. Hum. Retrov. 2021, 37, 736–743. 10.1089/aid.2020.0261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawant A. A.; Jadav S. S.; Nayani K.; Mainkar P. S. Development of Synthetic Approaches Towards HIV Integrase Strand Transfer Inhibitors (INSTIs). ChemistrySelect 2022, 7, e20220191 10.1002/slct.202201915. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y.; Gu S. X.; He Q. Q.; Fan R. H. Advances in the Development of HIV Integrase Strand Transfer Inhibitors. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2021, 225, 113787 10.1016/j.ejmech.2021.113787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Llibre J. M.; Pulido F.; Garcia F.; Deltoro M. G.; Blanco J. L.; Delgado R. Genetic Barrier to Resistance for Dolutegravir. AIDS Rev. 2015, 17, 56–64. 10.1097/COH.0000000000000709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mesplede T.; Wainberg M. A. Resistance Against Integrase Strand Transfer Inhibitors and Relevance to HIV Persistence. Viruses 2015, 7, 3703–3718. 10.3390/v7072790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charpentier C.; Descamps D. Resistance to HIV Integrase Inhibitors: About R263K and E157Q Mutations. Viruses 2018, 10, 41. 10.3390/v10010041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhee S. Y.; Grant P. M.; Tzou P. L.; Barrow G.; Harrigan P. R.; Ioannidis J. P. A.; Shafer R. W. A Systematic Review of the Genetic Mechanisms of Dolutegravir Resistance. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2019, 74, 3135–3149. 10.1093/jac/dkz256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kagan R. M.; Dunn K. J.; Snell G. P.; Nettles R. E.; Kaufman H. W. Trends in HIV-1 Drug Resistance Mutations from a US Reference Laboratory from 2006 to 2017. AIDS Res. Hum. Retrov. 2019, 35, 698–709. 10.1089/aid.2019.0063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mesplede T.; Quashie P. K.; Wainberg M. A. Resistance to HIV Integrase Inhibitors. Curr. Opin. HIV AIDS 2012, 7, 401–408. 10.1097/COH.0b013e328356db89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scutari R.; Alteri C.; Vicenti I.; Di Carlo D.; Zuccaro V.; Incardona F.; Borghi V.; Bezenchek A.; Andreoni M.; Antinori A.; Perno C. F.; Cascio A.; De Luca A.; Zazzi M.; Santoro M. M. Evaluation of HIV-1 Integrase Resistance Emergence and Evolution in Patients Treated with Integrase Inhibitors. J. Glob. Antimicrob. Res. 2020, 20, 163–169. 10.1016/j.jgar.2019.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parikh U. M.; Mellors J. W. How Could HIV-1 Drug Resistance Impact Preexposure Prophylaxis for HIV Prevention?. Curr. Opin. HIV AIDS 2022, 17, 213–221. 10.1097/COH.0000000000000746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huik K.; Hill S.; George J.; Pau A.; Kuriakose S.; Lange C. M.; Dee N.; Stoll P.; Khan M.; Rehman T.; Rehm C. A.; Dewar R.; Grossman Z.; Maldarelli F. High-level Dolutegravir Resistance Can Emerge Rapidly from Few Variants and Spread by Recombination: Implications for Integrase Strand Transfer Inhibitor Salvage Therapy. AIDS 2022, 36, 1835–1840. 10.1097/QAD.0000000000003288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anstett K.; Brenner B.; Mesplede T.; Wainberg M. A. HIV Drug Resistance Against Strand Transfer Integrase Inhibitors. Retrovirology 2017, 14, 36. 10.1186/s12977-017-0360-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rusconi S.; Santoro M. M.; Capetti A. F.; Gianotti N.; Zazzi M. The Future of Long-acting Cabotegravir Plus Rilpivirine Therapy: Deeds and Misconceptions. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2022, 60, 106627 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2022.106627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira M.; Ibanescu R. I.; Anstett K.; Mésplède T.; Routy J. P.; Robbins M. A.; Brenner B. G. Selective Resistance Profiles Emerging in Patient-derived Clinical isolates with Cabotegravir, Bictegravir, Dolutegravir, and Elvitegravir. Retrovirology 2018, 15, 56. 10.1186/s12977-018-0440-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith S. J.; Zhao X. Z.; Burke T. R.; Hughes S. H. Efficacies of Cabotegravir and Bictegravir Against Drug-resistant HIV-1 Integrase Mutants. Retrovirology 2018, 15, 37. 10.1186/s12977-018-0420-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parikh U. M.; Koss C. A.; Mellors J. W. Long-Acting Injectable Cabotegravir for HIV Prevention: What Do We Know and Need to Know about the Risks and Consequences of Cabotegravir Resistance?. Curr. HIV/AIDS Rep. 2022, 19, 384–393. 10.1007/s11904-022-00616-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyers K.; Nguyen N.; Zucker J. E.; Kutner B. A.; Carnevale C.; Castor D.; Sobieszczyk M. E.; Yin M. T.; Golub S. A.; Remien R. H. The Long-Acting Cabotegravir Tail as an Implementation Challenge: Planning for Safe Discontinuation. AIDS Behav. 2023, 27, 4–9. 10.1007/s10461-022-03816-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhee S. Y.; Parkin N.; Harrigan P. R.; Holmes S.; Shafer R. W. Genotypic Correlates of Resistance to the HIV-1 Strand Transfer Integrase Inhibitor Cabotegravir. Antiviral Res. 2022, 208, 105427 10.1016/j.antiviral.2022.105427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Machado L. d. A.; Guimaräes A. C. R. Evidence for Disruption of Mg(2+) Pair as a Resistance Mechanism Against HIV-1 Integrase Strand Transfer Inhibitors. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2020, 7, 170. 10.3389/fmolb.2020.00170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook N. J.; Li W.; Berta D.; Badaoui M.; Ballandras-Colas A.; Nans A.; Kotecha A.; Rosta E.; Engelman A. N.; Cherepanov P. Structural Basis of Second-generation HIV Integrase Inhibitor Action and Viral Resistance. Science 2020, 367, 806–810. 10.1126/science.aay4919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engelman A. N.; Cherepanov P. Close-up: HIV/SIV Intasome Structures Shed New Light on Integrase Inhibitor Binding and Viral Escape Mechanisms. FEBS J. 2021, 288, 427–433. 10.1111/febs.15438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawasuji T.; Johns B. A.; Yoshida H.; Taishi T.; Taoda Y.; Murai H.; Kiyama R.; Fuji M.; Yoshinaga T.; Seki T.; Kobayashi M.; Sato A.; Fujiwara T. Carbamoyl Pyridone HIV-1 Integrase Inhibitors. 1. Molecular Design and Establishment of an Advanced Two-metal Binding Pharmacophore. J. Med. Chem. 2012, 55, 8735–8744. 10.1021/jm3010459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawasuji T.; Johns B. A.; Yoshida H.; Weatherhead J. G.; Akiyama T.; Taishi T.; Taoda Y.; Mikamiyama-Iwata M.; Murai H.; Kiyama R.; Fuji M.; Tanimoto N.; Yoshinaga T.; Seki T.; Kobayashi M.; Sato A.; Garvey E. P.; Fujiwara T. Carbamoyl Pyridone HIV-1 Integrase Inhibitors. 2. Bi- and Tricyclic Derivatives Result in Superior Antiviral and Pharmacokinetic Profiles. J. Med. Chem. 2013, 56, 1124–1135. 10.1021/jm301550c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hare S.; Gupta S. S.; Valkov E.; Engelman A.; Cherepanov P. Retroviral Intasome Assembly and Inhibition of DNA Strand Transfer. Nature 2010, 464, 232–236. 10.1038/nature08784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyagawa M.; Akiyama T.; Taoda Y.; Takaya K.; Takahashi-Kageyama C.; Tomita K.; Yasuo K.; Hattori K.; Shano S.; Yoshida R.; Shishido T.; Yoshinaga T.; Sato A.; Kawai M. Synthesis and SAR Study of Carbamoyl Pyridone Bicycle Derivatives as Potent Inhibitors of Influenza Cap-dependent Endonuclease. J. Med. Chem. 2019, 62, 8101–8114. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.9b00861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahajan P. S.; Burke T. R. Jr. Synthetic Approaches to a Key Pyridone-Carboxylic Acid Precursor Common to the HIV-1 Integrase Strand Transfer Inhibitors, Dolutegravir, Bictegravir and Cabotegravir. Org. Process Res. Dev. 2023, 27, 847–853. 10.1021/acs.oprd.3c00063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahajan P. S.; Smith S. J.; Hughes S. H.; Zhao X. Z.; Burke T. R. Jr. A Practical Approach to Bicyclic Carbamoyl Pyridones with Application to the Synthesis of HIV-1 Integrase Strand Transfer Inhibitors. Molecules 2023, 28, 1428. 10.3390/molecules28031428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao X. Z.; Smith S. J.; Maskell D. P.; Metifiot M.; Pye V. E.; Fesen K.; Marchand C.; Pommier Y.; Cherepanov P.; Hughes S. H.; Burke T. R. Structure-Guided Optimization of HIV Integrase Strand Transfer Inhibitors. J. Med. Chem. 2017, 60, 7315–7332. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.7b00596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao X. Z.; Smith S. J.; Maskell D. P.; Metifiot M.; Pye V. E.; Fesen K.; Marchand C.; Pommier Y.; Cherepanov P.; Hughes S. H.; Burke T. R. HIV-1 integrase strand transfer inhibitors with reduced susceptibility to drug resistant mutant integrases. ACS Chem. Biol. 2016, 11, 1074–1081. 10.1021/acschembio.5b00948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao X. Z.; Smith S. J.; Metifiot M.; Johnson B. C.; Marchand C.; Pommier Y.; Hughes S. H.; Burke T. R. Bicyclic 1-Hydroxy-2-oxo-1,2-dihydropyridine-3-carboxamide-Containing HIV-1 Integrase Inhibitors Having High Antiviral Potency against Cells Harboring Raltegravir-Resistant Integrase Mutants. J. Med. Chem. 2014, 57, 1573–1582. 10.1021/jm401902n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith S. J.; Zhao X. Z.; Passos D. O.; Lyumkis D.; Burke T. R.; Hughes S. H. HIV-1 Integrase Inhibitors That Are Active against Drug-Resistant Integrase Mutants. Antimicrob. Agents Chemther. 2020, 64, 10. 10.1128/aac.00611-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Passos D. O.; Li M.; Jozwik I. K.; Zhao X. Z.; Santos-Martins D.; Yang R. B.; Smith S. J.; Jeon Y.; Forli S.; Hughes S. H.; Burke T. R.; Craigie R.; Lyumkis D. Structural basis for Strand-transfer Inhibitor Binding to HIV Intasomes. Science 2020, 367, 810–814. 10.1126/science.aay8015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li M.; Oliveira Passos D.; Shan Z.; Smith S. J.; Sun Q.; Biswas A.; Choudhuri I.; Strutzenberg T. S.; Haldane A.; Deng N.; Li Z.; Zhao X. Z.; Briganti L.; Kvaratskhelia M.; Burke T. R.; Levy R. M.; Hughes S. H.; Craigie R.; Lyumkis D. Mechanisms of HIV-1 Integrase Resistance to Dolutegravir and Potent Inhibition of Drug-resistant Variants. Sci. Adv. 2023, 9, eadg5953. 10.1126/sciadv.adg5953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith S. J.; Zhao X. Z.; Passos D. O.; Pye V. E.; Cherepanov P.; Lyumkis D.; Burke T. R.; Hughes S. H. HIV-1 Integrase Inhibitors with modifications that affect their potencies against drug sesistant integrase mutants. ACS Infect. Dis. 2021, 7, 1469–1482. 10.1021/acsinfecdis.0c00819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith S. J.; Hughes S. H. Rapid Screening of HIV Reverse Transcriptase and Integrase Inhibitors. JoVE 2014, 86, e51400 10.3791/51400-v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hombrouck A.; Voet A.; Van Remoortel B.; Desadeleer C.; De Maeyer M.; Debyser Z.; Witvrouw M. Mutations in Human Immunodeficiency Virus Type 1 Integrase Confer Resistance to the Naphthyridine L-870,810 and Cross-resistance to the Clinical Trial Drug GS-9137. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2008, 52, 2069–2078. 10.1128/AAC.00911-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bar-Magen T.; Sloan R. D.; Donahue D. A.; Kuhl B. D.; Zabeida A.; Xu H. T.; Oliveira M.; Hazuda D. J.; Wainberg M. A. Identification of Novel Mutations Responsible for Resistance to MK-2048, a Second-Generation HIV-1 Integrase Inhibitor. J. Virol. 2010, 84, 9210–9216. 10.1128/JVI.01164-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tzou P. L.; Rhee S. Y.; Descamps D.; Clutter D. S.; Hare B.; Mor O.; Grude M.; Parkin N.; Jordan M. R.; Bertagnolio S.; Schapiro J. M.; Harrigan P. R.; Geretti A. M.; Marcelin A. G.; Shafer R. W. Integrase Strand Transfer Inhibitor (INSTI)-Resistance Mutations for the Surveillance of Transmitted HIV-1 Drug Resistance. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2020, 75, 170–182. 10.1093/jac/dkz417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brenner B. G.; Thomas R.; Blanco J. L.; Ibanescu R. I.; Oliveira M.; Mesplede T.; Golubkov O.; Roger M.; Garcia F.; Martinez E.; Wainberg M. A. Development of a G118R Mutation in HIV-1 Integrase Following a Switch to Dolutegravir Monotherapy Leading to Cross-resistance to Integrase Inhibitors. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2016, 71, 1948–1953. 10.1093/jac/dkw071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quashie P. K.; Mesplede T.; Han Y. S.; Veres T.; Osman N.; Hassounah S.; Sloan R. D.; Xu H. T.; Wainberg M. A. Biochemical Analysis of the Role of G118R-linked Dolutegravir Drug Resistance Substitutions in HIV-1 Integrase. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2014, 58, 3580–3580. 10.1128/AAC.02916-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thierry E.; Lebourgeois S.; Simon F.; Delelis O.; Deprez E. Probing Resistance Mutations in Retroviral Integrases by Direct Measurement of Dolutegravir Fluorescence. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 14067. 10.1038/s41598-017-14564-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mens H.; Fjordside L.; Fonager J.; Gerstoft J. Emergence of the G118R Pan-Integrase Resistance Mutation as a Result of Low Compliance to a Dolutegravir-Based cART. Infect. Dis. Rep. 2022, 14, 501–504. 10.3390/idr14040053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Kampen J. J. A.; Pham H. T.; Yoo S.; Overmars R. J.; Lungu C.; Mahmud R.; Schurink C. A. M.; van Boheemen S.; Gruters R. A.; Fraaij P. L. A.; Burger D. M.; Voermans J. J. C.; Rokx C.; van de Vijver D.; Mesplede T. HIV-1 Resistance Against Dolutegravir Fluctuates Rapidly Alongside Erratic Treatment Adherence: A Case Report. J. Glob. Antimicrob. Res. 2022, 31, 323–327. 10.1016/j.jgar.2022.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Revollo B.; Vinuela L.; de la Mora L.; Garcia F.; Noguera-Julian M.; Parera M.; Paredes R.; Llibre J. M. Integrase Resistance Emergence with Dolutegravir/Lamivudine with Prior HIV-1 Suppression. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2022, 77, 1738–1740. 10.1093/jac/dkac082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira M.; Mesplede T.; Moisi D.; Ibanescu R. I.; Brenner B.; Wainberg M. A. The Dolutegravir R263K Resistance Mutation in HIV-1 Integrase is Incompatible with the Emergence of Resistance Against Raltegravir. AIDS 2015, 29, 2255–2260. 10.1097/QAD.0000000000000866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pham H. T.; Alves B. M.; Yoo S.; Xiao M. A.; Leng J.; Quashie P. K.; Soares E. A.; Routy J. P.; Soares M. A.; Mesplede T. Progressive Emergence of an S153F Plus R263K Combination of Integrase Mutations in the Proviral DNA of One Individual Successfully Treated with Dolutegravir. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2021, 76, 639–647. 10.1093/jac/dkaa471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed N.; Flavell S.; Ferns B.; Frampton D.; Edwards S. G.; Miller R. F.; Grant P.; Nastouli E.; Gupta R. K. Development of the R263K Mutation to Dolutegravir in an HIV-1 Subtype D Virus Harboring 3 Class-drug Resistance. Open Forum Infect. Dis. 2019, 6, ofy329. 10.1093/ofid/ofy329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hassounah S. A.; Mesplede T.; Quashie P. K.; Oliveira M.; Sandstrom P. A.; Wainberg M. A. Effect of HIV-1 Integrase Resistance Mutations When Introduced into SIVmac239 on Susceptibility to Integrase Strand Transfer Inhibitors. J. Virol. 2014, 88, 9683–9692. 10.1128/JVI.00947-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Underwood M.; Horton J.; Nangle K.; Hopking J.; Smith K.; Aboud M.; Wynne B.; Sievers J.; Stewart E. L.; Wang R. Integrase Inhibitor Resistance Mechanisms and Structural Characteristics in Antiretroviral Therapy-Experienced, Integrase Inhibitor-naive Adults with HIV-1 Infection Treated with Dolutegravir Plus Two Nucleoside Reverse Transcriptase Inhibitors in the DAWNING Study. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2022, 66, e0164321 10.1128/AAC.01643-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lubke N.; Jensen B.; Huttig F.; Feldt T.; Walker A.; Thielen A.; Daumer M.; Obermeier M.; Kaiser R.; Knops E.; Heger E.; Sierra S.; Oette M.; Lengauer T.; Timm J.; Haussinger D. Failure of Dolutegravir First-Line ART with Selection of Virus Carrying R263K and G118R. New Engl. J. Med. 2019, 381, 887–889. 10.1056/NEJMc1806554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wijting I.; Rokx C.; Boucher C.; van Kampen J.; Pas S.; de Vries-Sluijs T.; Schurink C.; Bax H.; Derksen M.; Andrinopoulou E. R.; van der Ende M.; van Gorp E.; Nouwen J.; Verbon A.; Bierman W.; Rijnders B. Dolutegravir as Maintenance Monotherapy for HIV (DOMONO): A Phase 2, Randomised Non-inferiority Trial. Lancet HIV 2017, 4, E547–E554. 10.1016/S2352-3018(17)30152-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malet I.; Ambrosio F. A.; Subra F.; Herrmann B.; Leh H.; Bouger M. C.; Artese A.; Katlama C.; Talarico C.; Romeo I.; Alcaro S.; Costa G.; Deprez E.; Calvez V.; Marcelin A. G.; Delelis O. Pathway Involving the N155H Mutation in HIV-1 Integrase Leads to Dolutegravir Resistance. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2018, 73, 1158–1166. 10.1093/jac/dkx529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malet I.; Thierry E.; Wirden M.; Lebourgeois S.; Subra F.; Katlama C.; Deprez E.; Calvez V.; Marcelin A. G.; Delelis O. Combination of Two Pathways Involved in Raltegravir Resistance Confers Dolutegravir Resistance. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2015, 70, 2870–2880. 10.1093/jac/dkv197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das K.; Lewi P. J.; Hughes S. H.; Arnold E. Crystallography and the Design of Anti-AIDS Drugs: Conformational Flexibility and Positional Adaptability are Important in the Design of Non-nucleoside HIV-1 Reverse Transcriptase Inhibitors. Prog. Biophys. Mol. Bio. 2005, 88, 209–231. 10.1016/j.pbiomolbio.2004.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das K.; Bauman J. D.; Clark A. D.; Frenkel Y. V.; Lewi P. J.; Shatkin A. J.; Hughes S. H.; Arnold E. High-resolution Structures of HIV-1 Reverse Transcriptase/TMC278 Complexes: Strategic Flexibility Explains Potency Against Resistance Mutations. P. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 1466–1471. 10.1073/pnas.0711209105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith S. J.; Pauly G. T.; Hewlett K.; Schneider J. P.; Hughes S. H. Structure-based Non-Nucleoside Inhibitor Design: Developing Inhibitors that are Effective Against Resistant Mutants. Chem. Biol. Drug Des. 2021, 97, 4–17. 10.1111/cbdd.13766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.