Abstract

Objectives

To investigate potential knowledge gaps between neurologists and non-specialists and identify challenges in the current management of chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyradiculoneuropathy (CIDP), with a focus on ‘early diagnosis’ and ‘appropriate treatment’ for CIDP.

Design

A non-interventional, cross-sectional, web-based quantitative survey of physicians working in healthcare clinics or hospitals in Japan.

Setting

Participants were recruited from the Nikkei Business Publications panel from 18 August to 14 September 2022.

Participants

Responses from 360 physicians (120 each of internists, orthopaedists and neurologists) were collected.

Outcome measures

Responses relating to a CIDP hypothetical case and current understanding were assessed to determine awareness, collaboration preferences and diagnosis and treatment decisions.

Results

Understanding of CIDP was 90.8% among neurologists, 10.8% among orthopaedists and 13.3% among internists; >80% of orthopaedists and internists answered that neurologists are preferable for treatment. Diagnostic assessment using a hypothetical case showed 95.0% of neurologists, 74.2% of orthopaedists and 72.5% of internists suspected CIDP. Among orthopaedists and internists suspecting CIDP, >70% considered referring to neurology, while ~10% considered continuing treatment without a referral. Among neurologists, 69.4% chose intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIg) as first-line treatment and determined effectiveness to be ≤3 months.

Conclusions

Orthopaedists and internists had lower CIDP awareness compared with neurologists, which may lead to inadequate referrals to neurology. Evaluation of IVIg effectiveness for maintenance therapy occurred earlier than the guideline recommendations (6–12 months), risking premature discontinuation. Improving CIDP knowledge among orthopaedists and internists is critical for better diagnosis and collaboration with neurologists. Neurologists should consider slow and careful evaluation of IVIg maintenance therapy.

Trial registration number

UMIN000048516.

Keywords: Polyradiculoneuropathy, Chronic Inflammatory Demyelinating; Awareness; Clinical Competence; Cross-Sectional Studies

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study included a diverse range of specialists and non-specialists across various healthcare settings in Japan.

The survey questions underwent rigorous validation by an expert panel, including a neurologist with chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyradiculoneuropathy expertise, orthopaedists and general physicians.

The reliance on a hypothetical case study may limit its real-world applicability and the generalisability of findings to actual clinical practice.

The inclusion of incentives and the non-mandatory nature of participation may introduce potential sources of bias.

Limiting the study to Nikkei Business Publications-registered physicians, the prevalence of board-certified fellows among participants and the uneven distribution of neurologists across different regions in Japan could influence the study’s outcomes.

Introduction

Chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyradiculoneuropathy (CIDP) is a type of neuropathy characterised by demyelination of both motor and sensory nerves. Initial symptoms are typically non-specific and include weakness, numbness and problems with gait and balance.1 Clinical guidelines recommend intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIg), corticosteroids and plasma exchange (PE) as first-line treatments.2 Current evidence does not suggest an overall preference between these options, although short-term and long-term effectiveness, risks and costs should be considered.2 As ‘early diagnosis’ and ‘appropriate treatment’ of CIDP are crucial to minimise disease progression,3 timely identification can lead to improved patient outcomes.4

However, achieving ‘early diagnosis’ presents challenges, as both misdiagnoses and underdiagnoses are common in clinical practice.5 This is often linked to patients with CIDP initially seeking care from non-specialists, such as orthopaedists and general internists, owing to initial symptoms that may appear indicative of orthopaedic conditions or medical disorders other than neurology. In Japan, the prevalence of CIDP has been reported to be between 0.00081% and 0.00161% in the total population,6 7 which was lower than global CIDP prevalence rates.8 These lower rates may be attributed to underdiagnosis9 due to the lack of knowledge about CIDP among non-specialists and limited collaboration with neurologists.

Regarding the ‘appropriate treatment’ of CIDP, the current status and challenges in CIDP treatment remain unclear due to a lack of surveillance surveys for neurologists. In particular, the following issues have not been clarified: (1) the consensus on the first-line drug for CIDP, (2) the optimal maintenance dosage of oral steroids and (3) the duration of IVIg maintenance therapy.

Thus, the purpose of this web-based surveillance survey was (1) to investigate potential knowledge gaps between specialists (neurologists) and non-specialists (orthopaedists and general internists) and (2) to determine the current status of CIDP treatment by neurologists in Japan.

Materials and methods

Study design

This was a non-interventional, cross-sectional, web-based quantitative survey conducted through the Nikkei Business Publications (NBP) panel from 18 August to 14 September 2022 in Japan. A planned total of 360 physicians (120 each of general internists, orthopaedists and neurologists) working in healthcare clinics or hospitals participated in the study. Participants were provided with information on the eligibility criteria and compensation through the study web page (managed by Rakuten Insight Global, Tokyo, Japan). Participants provided informed consent and answered screening questions to determine eligibility. Eligible participants received compensation, whereas ineligible participants did not. This study was registered at the University Hospital Medical Information Network-Clinical Trials Registry (https://www.umin.ac.jp/ctr/index.htm; identification: UMIN000048516).

Study setting and data sources

Participants were recruited from the NBP portal. A rigorous physician certification system ensured participant authenticity by including educational institution and graduation year.

On study registration, physical correspondence was mailed to the physician’s facility to confirm practice location. As of March 2022, there were 198 990 NBP-registered physicians (~59% of physicians in Japan). Approximately 62 000 were registered as general internists, 11 000 as orthopaedists and 4700 as neurologists, including both hospital and clinic physicians. All NBP-registered physicians were sent the web-based survey.

Selection criteria

Physicians who held medical society membership and had expertise in general internal medicine, orthopaedics or neurology were included. Physicians with <2 years of clinical practice (excluding training period) who were not actively practicing; were working in facilities other than clinics, university hospitals, general hospitals and national and public hospitals; or were not currently treating outpatients or inpatients were excluded.

Patient involvement

As the survey focused on the level of understanding of physicians, patients were not involved in the design, conduct, reporting or dissemination plans of this research study.

Objectives

The primary objective was to determine the level of self-assessed awareness of CIDP (defined as understanding how to treat or diagnose) among non-specialists (general internists and orthopaedists) and specialists (neurologists). Secondary objectives were to identify factors that led to misdiagnosis of CIDP among specialists and to determine key factors used to support diagnosis and treatment decisions in CIDP.

Variables

Survey questions (covariates) were delivered in Japanese. This included five screening questions and 40 questions related to the hypothetical case study, current understanding of CIDP and demographics of the study physicians. Question assessment and validation were conducted by a neurologist with CIDP expertise, orthopaedists and general physicians prior to the study start; five physicians (neurologist, orthopaedists, general internists), including authors YT, NO and YI, reviewed the questions. The case study used a tiered evaluation concept and comprised four stages (with four questions at each stage) and one question that applied to all stages (online supplemental table 1). Quantitative variables of interest included awareness of CIDP among participants, distribution and percentages of initial examinations and treatments in the hypothetical case study, and types of collaboration for CIDP at each stage of the hypothetical case study.

bmjopen-2023-083669supp001.pdf (620.8KB, pdf)

Statistical analysis

Data were anonymised by NBP and transferred and encrypted for storage. A descriptive analysis was performed to understand the quantitative nature of the collected data and the characteristics of the samples investigated rather than to establish statistical power; thus, sample size calculation was not conducted. Continuous (numeric) data were described by the number of non-missing values, median, mean, SD, minimum, maximum and IQRs. Categorical (nominal) data were reported as total numbers and percentages for each category. Statistical methods for handling missing data were not required in this study as questions with no answers were disallowed. χ2 testing was used to report p values <0.05. Aggregation and statistical analyses were performed using SAS V.9.4 (SAS Institute).

Results

Participant disposition

Of the 845 physicians who accessed the survey, 831 provided informed consent. The planned 360 participants (120 neurologists, 120 orthopaedists and 120 general internists) were included in the analysis (online supplemental figure 1). Reasons for exclusion were as follows: not continuing with the survey (n=68); holding positions other than neurologist, orthopaedist and general internist (n=60); discrepancies in age and years of experience in their current specialty (n=55); not affiliated with a medical society related to neurology, orthopaedics or general internal medicine (n=40); not working at a clinic or hospital (n=6); <2 years of experience in their current specialty, excluding training period (n=5); and/or not seeing inpatients or outpatients (n=1). Furthermore, 236 physicians were excluded due to exceeding the planned number of inclusions via a first-in method.

Demographics and other baseline characteristics

Participants were predominantly male (table 1). Mean (SD) years of experience was 21.13 (9.22) for neurologists, 21.07 (10.77) for orthopaedists and 22.80 (7.39) for general internists; the mean (SD) age in years was 50.45 (10.02) for neurologists, 49.31 (11.30) for orthopaedists and 54.06 (8.50) for general internists. Almost half of the participants worked at hospitals other than university, national or public hospitals.

Table 1.

Demographics and other baseline characteristics of study participants

| Characteristic | Study participants (N=360) | ||

| Neurologists N=120 |

Orthopaedists N=120 |

General internists N=120 |

|

| Sex | |||

| Male | 107 (89.2) | 112 (93.3) | 104 (86.7) |

| Female | 7 (5.8) | 3 (2.5) | 10 (8.3) |

| Prefer not to answer | 6 (5.0) | 5 (4.2) | 6 (5.0) |

| Experience, years | |||

| Mean (SD) | 21.13 (9.22) | 21.07 (10.77) | 22.80 (7.39) |

| Median (min, max) | 22 (2, 45) | 20.5 (2, 47) | 25 (6, 36) |

| Age, years | |||

| Mean (SD) | 50.45 (10.02) | 49.31 (11.30) | 54.06 (8.50) |

| Median (min, max) | 51 (28, 73) | 50 (30, 76) | 56 (36, 70) |

| Institution type | |||

| Clinic | 10 (8.3) | 22 (18.3) | 46 (38.3) |

| University hospital | 31 (25.8) | 16 (13.3) | 5 (4.2) |

| National or public hospital | 25 (20.8) | 24 (20.0) | 12 (10.0) |

| Other hospital | 54 (45.0) | 58 (48.3) | 57 (47.5) |

| Board certification | |||

| Board-certified trainer | 63 (52.5) | 35 (29.2) | 26 (21.7) |

| Board-certified fellow | 43 (35.8) | 74 (61.7) | 63 (52.5) |

| Board-certified member | 7 (5.8) | 3 (2.5) | 14 (11.7) |

| Not certified for any of the above | 7 (5.8) | 8 (6.7) | 17 (14.2) |

| Region | |||

| Northern | 14 (11.7) | 9 (7.5) | 17 (14.2) |

| Central | 90 (75.0) | 76 (63.3) | 78 (65.0) |

| Western | 16 (13.3) | 35 (29.2) | 25 (20.8) |

Data are n (%) unless otherwise specified.

Northern region includes Hokkaido and Tohoku; central region includes Kanto, Chubu and Kinki; western region includes Chugoku, Shikoku, Kyushu and Okinawa.

max, maximum; min, minimum.

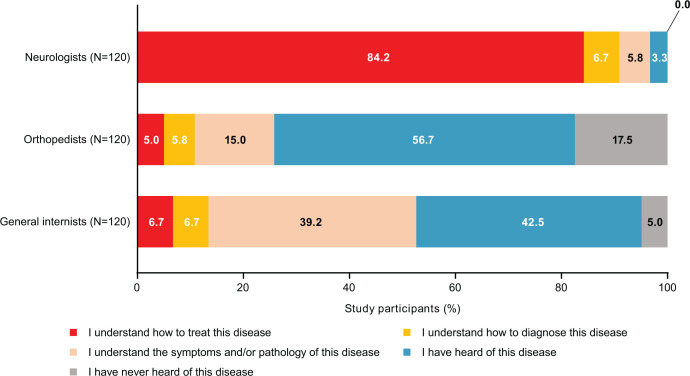

Level of understanding of CIDP diagnosis and treatment

Overall, self-assessed awareness of CIDP (defined as understanding how to treat or diagnose) was 90.8% among neurologists, 10.8% among orthopaedists and 13.3% among general internists. Knowledge level was highest among neurologists; 84.2% answered that they understood how to treat CIDP and 6.7% answered they understood how to diagnose it (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Awareness (knowledge level) of CIDP among participants. CIDP, chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyradiculoneuropathy.

CIDP hypothetical case study

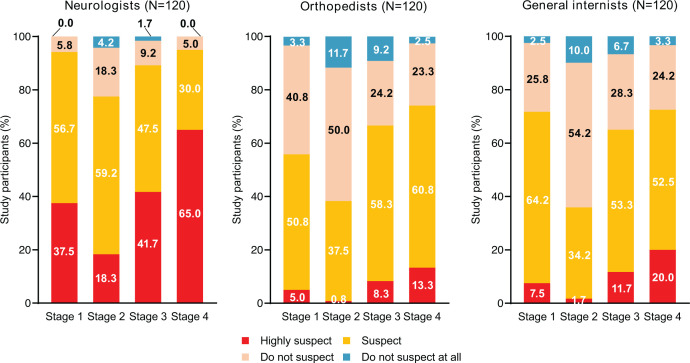

CIDP suspicion in each stage

On completion of the case study (stage 4), 95.0% of neurologists, 74.2% of orthopaedists and 72.5% of general internists suspected or highly suspected CIDP. At stage 1 (online supplemental table 1), most neurologists suspected CIDP (37.5% highly suspected and 56.7% suspected) (figure 2). Over half of orthopaedists suspected CIDP (5.0% highly suspected and 50.8% suspected). A higher proportion of internists highly suspected (7.5%) or suspected (64.2%) CIDP compared with orthopaedists. At stage 2, fewer neurologists highly suspected CIDP (18.3%) compared with stage 1, although the number of those who suspected CIDP (59.2%) was similar. CIDP suspicion among both orthopaedists and internists decreased in stage 2 compared with stage 1. At stage 3, CIDP suspicion among neurologists increased to 41.7% highly suspecting and 47.5% suspecting. A similar increase was seen among orthopaedists and internists. At stage 4, those who highly suspected CIDP experienced the largest increase in numbers among neurologists (65.0%), followed by internists (20.0%) and orthopaedists (13.3%).

Figure 2.

Distribution and percentages of CIDP suspicion in each stage among participants (results of responses to hypothetical case questions). CIDP, chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyradiculoneuropathy.

Types of collaboration for CIDP in each stage

At stage 1, most neurologists (85.8%) and orthopaedists (75.0%) preferred to continue treatment in their own department, while this was the case for 40.8% of general internists (online supplemental figure 2A). At stage 2, 54.2% of neurologists preferred to continue treatment in their own department, which remained consistent through stages 3 (50.0%) and 4 (48.3%).

At stage 2, the proportion of orthopaedists who preferred to continue treatment in their own department dropped to 40.8%, and this dropped further to 15.8% at stage 3 and to 12.5% at stage 4. At stage 4, 50.0% preferred referral to a different department at a different institution. Only a small proportion of general internists preferred to continue treatment in their own department at stages 2 (10.8%), 3 (5.8%) and 4 (11.7%). At stage 2, 40.0% indicated referral to a different department at a different institution; this increased to 51.7% at stage 3 and 68.3% at stage 4. These preferences were similar in a subset of orthopaedists (n=67) and general internists (n=86) who suspected CIDP at stage 1 (online supplemental figure 2B).

Treatment choice for suspected CIDP by region

Immunoglobulin was generally the most commonly selected treatment choice for suspected CIDP in all regions across all stages of the hypothetical case study (online supplemental table 2).

Neurologist behaviour in clinical practice

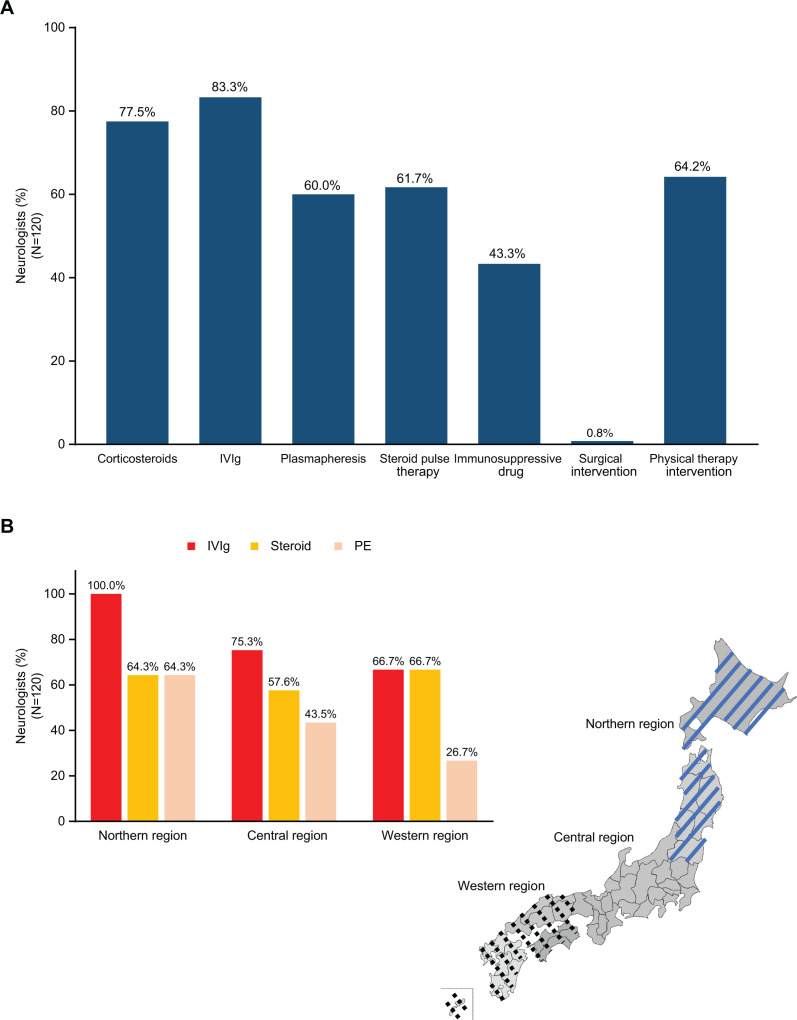

CIDP treatments typically administered among neurologists

Neurologists most typically administered IVIg (83.3%) for CIDP treatment, followed by corticosteroids (77.5%), physical therapy intervention (64.2%), steroid pulse therapy (61.7%) and plasmapheresis (60.0%) (figure 3A).

Figure 3.

First-line drug treatment choice for CIDP. (A) Distribution and percentage of CIDP treatments typically administered during clinical practice among neurologists. (B) Regional differences in treatment choice for CIDP. CIDP, chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyradiculoneuropathy; IVIg, intravenous immunoglobulin; PE, plasma exchange.

Regional differences in treatment choice for CIDP

Among neurologists from the northern region, IVIg was the predominant first-line treatment choice (100.0%), with both steroids and PE selected by 64.3% of neurologists (figure 3B). In the central region, IVIg was the most selected treatment choice (75.3%), followed by steroids (57.6%) and PE (43.5%). In the western region, the selection rates for IVIg and steroids were identical (66.7%), while the selection rate for PE was lower (26.7%). There were no regional differences in steroid selection rates, but IVIg had a higher selection rate in the northern region, and PE had a lower selection rate in the western region.

Selection of CIDP maintenance therapy among neurologists

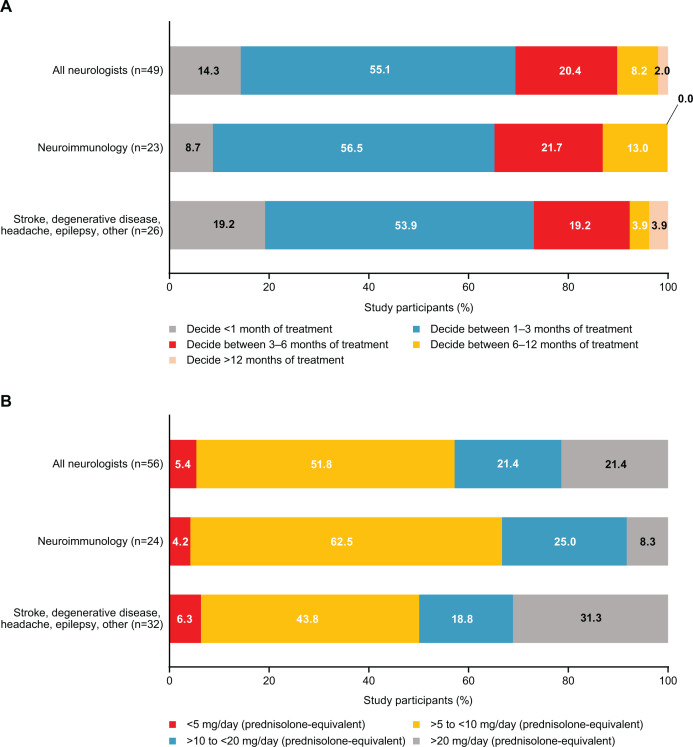

Timing of assessment of patient response to immunoglobulin maintenance treatment

Among neurologists who selected immunoglobulin for CIDP maintenance therapy (n=49), 55.1% considered 1–3 months of treatment before assessment as appropriate (figure 4A). A smaller proportion considered <1 month (14.3%), 3–6 months (20.4%) and 6–12 months (8.2%) as appropriate. One neurologist considered >12 months as appropriate.

Figure 4.

Distribution and percentage of CIDP maintenance treatment preferences among neurologists. (A) Timing of patient treatment response to immunoglobulin maintenance treatment. (B) CIDP maintenance dosage of steroids. CIDP, chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyradiculoneuropathy.

Among the subset of neurologists specialising in neuroimmunology (n=23), 8.7% selected a duration of <1 month for IVIg maintenance therapy, while the selection rate for the same duration was 19.2% among neurologists in other fields (eg, stroke, degenerative disease, headache, epilepsy or other).

CIDP maintenance dosage of steroids

Among neurologists who selected steroids for CIDP maintenance therapy (n=56), 51.8% indicated that a prednisolone-equivalent dosage of 5–10 mg/day was appropriate (figure 4B). Higher dosages of 10–20 mg/day or >20 mg/day were indicated as appropriate by 21.4% of neurologists, and a lower dosage of <5 mg/day was indicated as appropriate by 5.4%.

Among neurologists specialising in neuroimmunology (n=24), a higher proportion indicated they would prescribe 5–10 mg/day (62.5%). Among those specialising in stroke, degenerative disease, headache, epilepsy or other (n=32), a lower proportion indicated they would prescribe 5–10 mg/day (43.8%). Interestingly, 31.3% from this subset indicated >20 mg/day was appropriate.

Discussion

This non-interventional, cross-sectional, web-based quantitative survey is the first to evaluate the level of self-assessed awareness of CIDP (defined as understanding how to treat or diagnose) among physicians in Japan. We reported referral preferences between non-specialists (orthopaedists and general internists) and neurologists in Japan as well as CIDP treatment preferences of neurologists in clinical practice.

Notably, our study had several strengths. First, data were collected from a diverse array of participants, encompassing both specialists and non-specialists from healthcare clinics and hospital settings across Japan. Second, survey questions underwent assessment and validation by a panel of experts comprising a neurologist with CIDP expertise, orthopaedists and general physicians. We identified several limitations. The hypothetical case used in our study may not fully represent real clinical practice, despite collaboration with experts. Limited details on lower limb weakness make CIDP diagnosis uncertain. More specific nerve conduction studies to show demyelination findings could have been informative, as other conditions may mimic the presentation. As participation was non-mandatory, there may have been selection bias as highly motivated physicians were more likely to participate. The inclusion of incentives has the potential to influence physicians' perceptions and participation, introducing bias that may subsequently affect the study’s outcomes. Responses may have been limited by the regulations and standards of their respective institutions. Recall bias may have occurred due to the nature of human memory. There was no process to check response accuracy. Participants may not have understood the questions asked or the reasons for the survey. Demand characteristics may have also occurred, where participants responded or behaved differently because they were part of a study. For instance, physicians who answered ‘I understand how to treat this disease’, ‘I understand how to diagnose this disease’ and ‘I understand the symptoms and/or pathology of this disease’ should theoretically be able to suspect CIDP, yet among the non-specialist groups, a higher proportion suspected CIDP at stage 1 of the case study than had indicated they understood CIDP. This study was limited to NBP-registered neurologists, orthopaedists and general internists, and the results cannot be broadly generalised to other specialties. The prevalence of board-certified fellows among physicians in this study, particularly in the non-neurology group, could potentially limit the interpretation of the presented data. Furthermore, the distribution of neurologists or neurology departments across different regions in Japan was not consistent. Response bias may have occurred due to the discrepancy of information bias among regions.

We found that most neurologists had a better understanding of CIDP relative to non-specialists, who mostly preferred to refer patients to another physician for treatment (figure 1). This is reflected in the results of CIDP suspicion across all stages of a hypothetical case study, where more neurologists suspected CIDP than non-specialists. This highlights the importance of increasing CIDP awareness and knowledge among non-specialty physicians. This is in line with previous studies, which also recommend the need for clearer and more clinically focused guidelines in Japan.10 11

In stage 2 of the case study, some physicians who suspected CIDP at stage 1 turned to suspect orthopaedic diseases despite inconsistencies between the imaging findings and the clinical signs from neurological examinations (figure 2). Unfortunately, this suggests that physicians might give more weight to imaging findings than clinical signs. Meanwhile, as symptoms of early-stage CIDP (including weakness in the limbs) are common in cervical spondylotic myelopathy, neurologists and orthopaedists cannot dismiss the possibility of disorders relating to the spinal cord.12

Regarding referral practices in the hypothetical case study, 75.0% of orthopaedists and 40.8% of general internists preferred to continue to evaluate for a potential CIDP diagnosis within their own department at stage 1, with ~12% of orthopaedists and general internists still preferring this by stage 4 (online supplemental figure 2A). It is reasonable to speculate that some patients with CIDP would not be referred to neurologists in clinical practice. Because of the lack of CIDP awareness among non-specialists, missed diagnoses can lead to delayed, erroneous or completely absent treatments, resulting in negative long-term outcomes for patients. This emphasises the importance of collaboration between non-specialists and neurologists, and the importance of CIDP education.

Most neurologists preferred IVIg (83.3%) or corticosteroids (77.5%) as the treatment choice for CIDP in clinical practice (figure 3A). This is in line with clinical guidelines, which recommend both IVIg and oral or intravenous corticosteroids as first-line treatments.2 IVIg may be preferred for short-term effectiveness or if contraindications to corticosteroids exist.2 Corticosteroids may be preferred for long-term effectiveness due to increased rate and duration of remission or if IVIg costs are unaffordable.2 Comparable results were observed in the Dutch survey, wherein most neurologists preferred IVIg as the first treatment choice (82%) and corticosteroids as a second choice (71%).11 Treatment choice was different among neurologists in the USA compared with this study. A cross-sectional, quantitative survey reported that only 44% of neurologists described using IVIg alone as first line, while 20% preferred corticosteroids alone as first line.10 Then, 24% reported using IVIg and corticosteroids together as first line despite this not being a guideline recommendation.2 10

The results of this study showed that 55.1% of neurologists who responded that they use IVIg to treat CIDP decided to evaluate patient response to IVIg maintenance treatment between 1 and 3 months, while 14.3% considered <1 month as appropriate. This trend was consistent regardless of specialisation in neuroimmunology. However, this trend differs from the clinical guidelines, which recommend a review every 6–12 months during the first 2–3 years of treatment and less frequently (every 1–2 years) thereafter.2 A 2022 post hoc analysis of the phase 3 PRISM trial of IVIg for CIDP suggested that treatment response may continue up to 24 weeks (~6 months).13 Moreover, some research has indicated that demyelinated nerves took up to 6 months to recover.14 15 Therefore, it would be more appropriate to assess treatment at longer time intervals, preferably at ≥6 months. However, if neurologists decide to evaluate patient response to IVIg maintenance treatment within 1–3 months, patients may prematurely discontinue treatment before effectiveness has been sufficiently evaluated.

Among neurologists who said they use corticosteroids as maintenance treatment for CIDP, 73.2% prescribed treatment in prednisolone-equivalent dosages of 5–20 mg/day in clinical practice, although international guidance on corticosteroid-tapering regimens for adults recommends a maintenance prednisolone-equivalent dosage of 5–7.5 mg/day.16 The EAN/PNS Clinical Practice Guideline 2021 states the best corticosteroid dose and tapering regimen are not known. Standards on corticosteroid doses for CIDP currently do not exist in Japan. However, the guideline reiterates that long-term treatment induces significant side effects.2 A consensus is needed among Japanese neurologists to ensure consistency of corticosteroid doses for CIDP.

This study of physicians’ awareness of CIDP showed that neurologists had a better understanding of CIDP compared with non-specialists. Lower awareness among non-specialists resulted in a lack of referral to neurologists. Increased knowledge is critical for better diagnosis and collaboration with neurologists as delays in referral would be detrimental during initial CIDP treatment.3 Furthermore, this study showed that evaluation of the effectiveness of IVIg maintenance therapy is determined to be ≤3 months in clinical practice, which is earlier than the 6-month guideline and clinical trial recommendation.2 13 To achieve ‘early diagnosis’ and implement ‘appropriate treatment’ for CIDP, it is critical to (1) improve CIDP knowledge among orthopaedists and general internists and (2) establish collaboration with neurologists in the early stages of CIDP management. Neurologists should carefully consider the appropriate dose of oral steroids and evaluate IVIg maintenance therapy.

bmjopen-2023-083669supp002.pdf (84.1KB, pdf)

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all study participants. They would also like to thank Keiko Asao, MD, PhD (IQVIA Solutions Japan KK), for medical review as a general physician and Sven Demiya, PhD, MBA, and Sona-Sanae Aoyagi, PhD (IQVIA Solutions Japan KK), for statistical analysis. Medical writing assistance was provided by Jason Vuong, BPharm, and Prudence Stanford, PhD, CMPP, of ProScribe – Envision Pharma Group, and was funded by Takeda. ProScribe’s services complied with international guidelines for Good Publication Practice (GPP). Takeda was involved in the study design and preparation of the manuscript. Nikkei Business Publications (NBP) panel, a subsidiary of the Nihon Keizai Shimbun Group, was involved in data collection and data analysis. IQVIA Solutions Japan KK was involved in statistical analysis.

Footnotes

Contributors: YT, YI, AO, MK and NO contributed to the study design and interpretation. AO, MK and NO performed the study. YT, YI, AO, MK and NO read and approved the final manuscript. AO is responsible for the overall content as guarantor.

Funding: This study was supported by Takeda Pharmaceutical Company Limited.

Competing interests: YT and YI have received support and consulting fees from Takeda Pharmaceutical Company Limited. AO, MK and NO are employees of Takeda Pharmaceutical Company Limited.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research. Refer to the Methods section for further details.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; peer reviewed for ethical and funding approval prior to submission.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

No data are available.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

This study involves human participants and was approved by MINS Research Ethics Review Committee. Participants gave informed consent to participate in the study before taking part.

References

- 1. Querol LA, Hartung H-P, Lewis RA, et al. The role of the complement system in chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy: implications for complement-targeted therapies. Neurotherapeutics 2022;19:864–73. 10.1007/s13311-022-01221-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Van den Bergh PYK, van Doorn PA, Hadden RDM, et al. European Academy of Neurology/Peripheral Nerve Society guideline on diagnosis and treatment of chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyradiculoneuropathy: report of a joint Task Force-Second revision. Eur J Neurol 2021;28:3556–83. 10.1111/ene.14959 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Muley SA, Parry GJ. Inflammatory demyelinating neuropathies. Curr Treat Options Neurol 2009;11:221–7. 10.1007/s11940-009-0026-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Allen JA, Gelinas DF, Freimer M, et al. Immunoglobulin administration for the treatment of CIDP: IVIG or SCIG?. J Neurol Sci 2020;408:116497. 10.1016/j.jns.2019.116497 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Eftimov F, Lucke IM, Querol LA, et al. Diagnostic challenges in chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyradiculoneuropathy. Brain 2020;143:3214–24. 10.1093/brain/awaa265 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kusumi M, Nakashima K, Nakayama H, et al. Epidemiology of inflammatory neurological and inflammatory neuromuscular diseases in Tottori Prefecture, Japan. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 1995;49:169–74. 10.1111/j.1440-1819.1995.tb02223.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Iijima M, Koike H, Hattori N, et al. Prevalence and incidence rates of chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy in the Japanese population. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2008;79:1040–3. 10.1136/jnnp.2007.128132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Broers MC, Bunschoten C, Nieboer D, et al. Incidence and prevalence of chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyradiculoneuropathy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Neuroepidemiology 2019;52:161–72. 10.1159/000494291 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Miyashiro A, Matsui N, Shimatani Y, et al. Are multifocal motor neuropathy patients underdiagnosed? An epidemiological survey in Japan. Muscle Nerve 2014;49:357–61. 10.1002/mus.23930 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Gelinas D, Katz J, Nisbet P, et al. Current practice patterns in CIDP: a cross-sectional survey of neurologists in the United States. J Neurol Sci 2019;397:84–91. 10.1016/j.jns.2018.11.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Broers MC, van Doorn PA, Kuitwaard K, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyradiculoneuropathy in clinical practice: a survey among Dutch neurologists. J Peripher Nerv Syst 2020;25:247–55. 10.1111/jns.12399 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. de Oliveira Vilaça C, Orsini M, Leite MAA, et al. Cervical spondylotic myelopathy: what the neurologist should know. Neurol Int 2016;8:6330. 10.4081/ni.2016.6330 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Rajabally YA, Ouaja R, Kasiborski F, et al. Assessment timing and choice of outcome measure in determining treatment response in chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy: a post hoc analysis of the PRISM trial. Muscle Nerve 2022;66:562–7. 10.1002/mus.27713 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Grimm A, Décard BF, Schramm A, et al. Ultrasound and electrophysiologic findings in patients with Guillain-Barre syndrome at disease onset and over a period of six months. Clin Neurophysiol 2016;127:1657–63. 10.1016/j.clinph.2015.06.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Riekhoff AGM, Jadoul C, Mercelis R, et al. Childhood chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuroradiculopathy--three cases and a review of the literature. Eur J Paediatr Neurol 2012;16:315–31. 10.1016/j.ejpn.2011.12.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Liu D, Ahmet A, Ward L, et al. A practical guide to the monitoring and management of the complications of systemic corticosteroid therapy. Allergy Asthma Clin Immunol 2013;9:30. 10.1186/1710-1492-9-30 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2023-083669supp001.pdf (620.8KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2023-083669supp002.pdf (84.1KB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

No data are available.