Abstract

Lisuride is a non-psychedelic serotonin (5-HT) 2A receptor (5-HT2A) agonist and analogue of the psychedelic lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD). Lisuride also acts as an agonist at the serotonin 1A receptor (5-HT1A), a property known to counter psychedelic effects. Here, we tested whether lisuride lacks psychedelic activity due to a dual mechanism: (1) partial agonism at 5-HT2A and (2) potent agonism at 5-HT1A. The in vitro effects of lisuride, LSD, and related analogues on 5-HT2A signaling were characterized by using miniGαq and β-arrestin 2 recruitment assays. The 5-HT1A- and 5-HT2A-mediated effects of lisuride and LSD were also compared in male C57BL/6J mice. The in vitro results confirmed that LSD is an agonist at 5-HT2A, with high efficacy and potency for recruiting miniGαq and β-arrestin 2. By contrast, lisuride displayed partial efficacy for both functional end points (6–52% of 5-HT or LSD Emax) and antagonized the effects of LSD. The mouse experiments demonstrated that LSD induces head twitch responses (HTRs)(ED50 = 0.039 mg/kg), while lisuride suppresses HTRs (ED50 = 0.006 mg/kg). Lisuride also produced potent hypothermia and hypolocomotion (ED50 = 0.008–0.023 mg/kg) that was blocked by the 5-HT1A antagonist WAY100635 (3 mg/kg). Blockade of 5-HT1A prior to lisuride restored basal HTRs, but it failed to increase HTRs above baseline levels. HTRs induced by LSD were blocked by lisuride (0.03 mg/kg) or the 5-HT1A agonist 8-OH-DPAT (1 mg/kg). Overall, our findings show that lisuride is an ultrapotent 5-HT1A agonist in C57BL/6J mice, limiting its use as a 5-HT2A ligand in mouse studies examining acute drug effects. Results also indicate that the 5-HT2A partial agonist-antagonist activity of lisuride explains its lack of psychedelic effects.

Keywords: 5-HT2A, lisuride, LSD, psychedelic, 5-HT1A

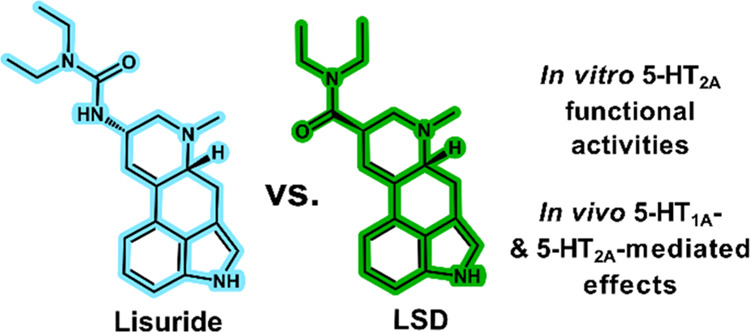

Lisuride is a close structural analogue of the psychedelic ergoline lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD, structures shown in Figure 1A). In contrast to LSD, lisuride does not produce psychedelic-like effects, despite its known agonist activity at the serotonin (5-HT) 2A receptor (5-HT2A).1−5 Clinical investigations show that lisuride is devoid of psychedelic subjective effects in humans,1,4,6 which is consistent with its lack of activity in animal models measuring psychedelic-like effects, including the 5-HT2A-mediated head twitch response (HTR) in mice.2,3,7 Because of its unique pharmacology, lisuride has been used in many preclinical pharmacological investigations as a “non-psychedelic” or “non-hallucinogenic” 5-HT2A agonist.2,3,7−11 Several potential explanations have been proposed to explain the lack of psychedelic effects for lisuride, including biased agonism or partial efficacy at 5-HT2A2,8,10,12−15 or potential non-5-HT2A activities that serve to attenuate its psychedelic actions.16−19

Figure 1.

Chemical structures of lisuride and LSD (A) and heatmap of functional parameters for each of the tested substances in both assay formats. (B) EC50 values for in vitro functional potency in βarr2 and miniGαq assays as well as Emax values relative to the Emax of LSD (C) and serotonin (D, 5-HT), which were arbitrarily defined as 100%. Darker colors indicate higher potencies (lower EC50 values) and efficacies. Data are from at least three biologically independent experiments, each performed in duplicate.

In addition to its 5-HT2A agonist activity,5,20,21 lisuride has many other biological targets.22 These include dopamine receptors (D1- and D2-like),22,23 non-5-HT2A serotonin receptor subtypes (5-HT1A, 5-HT2C, and others),5,20 as well as other sites (adrenergic and histamine receptors).22 From a clinical perspective, the dopamine receptor agonist properties of lisuride are thought to mediate its efficacy in treating early symptoms of Parkinson’s disease.24 Previous experiments in rats showed that lisuride is a more potent agonist at 5-HT1A than LSD, and this property distinguishes the two drugs.16,20,25 Finally, studies in mice demonstrate that the 5-HT2A-mediated HTR is suppressed by the 5-HT1A agonist activity of certain psychedelic compounds,26−32 including the ergoline lysergic acid morpholide (LSM-775).31

At present, it is unclear whether the lack of psychedelic effects of lisuride is due to weak signaling efficacy at 5-HT2A, effects exerted at non-5-HT2A targets, or perhaps both mechanisms. Here, we hypothesized that lisuride is devoid of psychedelic actions due to a two-pronged mechanism: (1) partial agonism at 5-HT2A, coupled with (2) potent agonism at 5-HT1A. First, we examined the in vitro 5-HT2A functional activities of lisuride, LSD, and three structurally related ergolines in assays measuring G-protein and β-arrestin 2 (βarr2) recruitment. Next, we compared the in vivo effects of lisuride and LSD in mice to evaluate 5-HT2A-mediated HTR and 5-HT1A-mediated hypothermia and locomotor suppression. Given the other known targets of lisuride, we also investigated the possible role of D1-like, D2-like, and 5-HT2C receptor activity in the acute effects of lisuride. Site-selective receptor antagonists were employed to discern the role of specific receptor subtypes in mediating in vivo effects.

Results and Discussion

Functional Assessments of Lisuride and LSD at 5-HT2AIn Vitro

The 5-HT2A activating potential of lisuride was compared to LSD and several ergoline analogues. To this end, two different in vitro assays were employed, which monitor the recruitment of either βarr2 or miniGαq by 5-HT2A, utilizing NanoBiT functional complementation techniques.33,34 In this study, we opted to test only βarr2, rather than both βarr1 and βarr2, because of the reported relevance of the latter in LSD-stimulated behaviors in mice.35 Further, βarr2 has recently been reported to be required for LSD-induced reopening of the “social reward learning critical period” in mouse behavioral studies.36 The employed NanoBiT technology is specifically designed to monitor protein–protein interactions37 and consists of two split subunits of a nanoluciferase enzyme. In the assays used here, one subunit of the enzyme is fused to the C-terminus of the 5-HT2A, and the other subunit to the N-terminus of either βarr2 or the engineered miniGαq protein (as described by Nehmé et al.).38 Upon activation of the receptor, the intracellular protein is brought closer to the receptor protein, thereby allowing functional complementation of the enzyme subunits and a concomitant luminescent signal in the presence of the enzyme substrate.37 The in vitro functional potencies (expressed as EC50 values) and efficacies (expressed as Emax values relative to the maximal response of LSD and 5-HT) obtained in both recruitment assays are provided in Figure 1B–D, with associated curves (%LSD) shown in Figures 2A,B and S1. LSD was included as a reference compound for Emax in addition to 5-HT because the present study aimed to directly compare lisuride to LSD.

Figure 2.

(A,B) Concentration–response curves for effects of lisuride (A) and LSD (B) in 5-HT2Ain vitro recruitment assays. (C, D) Effects of lisuride on the functional activity of LSD for 5-HT2A-mediated β-arrestin 2 (C) and miniGαq (D) recruitment assays. Concentration–response curves for cells that were preincubated for 5 min with either lisuride or a corresponding solvent control, after which a concentration range of LSD (green curve), 100 nM LSD (purple curve), or the corresponding solvent control (blue curve) was added. Data in all panels are the mean ± SEM of three biologically independent experiments, each performed in duplicate, and normalized relative to the Emax of LSD. LIS = lisuride.

In addition to lisuride, the structurally related ergolines 2-bromolysergic acid diethylamide (2-Br-LSD), 6-allyl-6-nor-lysergic acid diethylamide (AL-LAD), and lysergic acid methylpropylamide (LAMPA) were included in the current experiments (structures shown in Figure S1). DOI and serotonin were also included as reference compounds to enable comparison of the current results with those obtained previously. Results for reference agonists LSD, serotonin, and DOI align with previously published data obtained with the same assays and with data obtained using a cell line stably expressing the assay components of the βarr2 assay (Figures 1 and S1).33,34,39−43 Specifically, low nanomolar EC50 values were observed for LSD in both 5-HT2A receptor recruitment assays. Serotonin exhibited a similar EC50 value and a higher Emax value in the βarr2 assay relative to LSD. Serotonin also displayed weaker potency but higher Emax values in the miniGαq recruitment assay relative to LSD. The last reference compound, DOI, displayed higher potency and efficacy in the βarr2 assay, with a similar potency and an increased efficacy in the miniGαq assay vs LSD.

The data revealed notable functional differences among the various ergoline analogues (Figures 1, 2, and S1). Compared to LSD, lisuride displayed partial agonist effects in the βarr2 recruitment assay (52 and 45% of LSD and serotonin Emax respectively) with a slightly reduced potency. In the miniGαq assay, lisuride was even weaker, exhibiting an efficacy of only 15% relative to LSD, indicative of a relative preference toward βarr2 recruitment. When compared to DOI or serotonin as reference agonists, the relative efficacy of lisuride in the miniGαq assay would be even lower (yielding an Emax of 8% for lisuride when the Emax of DOI is set at 100%, or an Emax of merely 6% when the Emax of serotonin is set at 100%). These findings indicate a strong preference of lisuride toward βarr2 recruitment, relative to either DOI or serotonin.

2-Br-LSD displayed a slightly higher potency than LSD in both recruitment assays, but efficacies were strongly reduced relative to LSD, with a lower Emax in the βarr2 (47.7% of LSD Emax) and miniGαq (23.5% of LSD Emax) recruitment assays. It is interesting that we found the 5-HT2A efficacy profile of 2-Br-LSD to be quite similar to that of lisuride, and 2-Br-LSD is devoid of psychedelic effects in humans and animals.44 These observations still hold true when the data are normalized to the serotonin reference instead of LSD (Figure 1C). Relative to LSD as a reference, potencies for AL-LAD were similar to those of LSD in both assays, but the efficacies were higher, yielding values of 137 and 167% for βarr2 and miniGαq recruitment, respectively. The data with AL-LAD are noteworthy, since in the assay format used, it displayed a slight preference toward recruitment of miniGαq over βarr2. However, when normalized relative to serotonin, which is the most efficacious agonist in the miniGαq setup, both LSD and AL-LAD display efficacies below 100%. In that scenario, all of the investigated compounds are more efficacious in the βarr2 recruitment assay than in the miniGαq assay. Irrespective of whether LSD or serotonin is used as a reference compound, AL-LAD remains the most efficacious agonist in the βarr2 assay. The third analogue, LAMPA, displayed EC50 values similar to those of LSD and slightly decreased Emax values in both assays (87–89% of LSD Emax).

Based on the weak efficacy of lisuride in both recruitment assays, we assessed the ability of lisuride to antagonize the effects of LSD at 5-HT2Ain vitro. To this end, cells were preincubated with a concentration range of lisuride, to which 100 nM LSD was added, in both assays. The results of that experiment are shown in the purple curves of Figure 2C,D. The green and blue curves result from control conditions, involving a concentration range of LSD after “preincubation” with the solvent control of lisuride (in green), and a concentration range of lisuride to which the solvent control of LSD was added (in blue).

Following preincubation with a low concentration of lisuride, 100 nM LSD was still able to induce the recruitment of βarr2 to the same extent as when no lisuride was present. When the concentration of lisuride was increased, the activity of LSD was reduced to the level that coincided with the upper plateau of the concentration–response curve of lisuride in this assay. The results indicate that lisuride is capable of antagonizing the effect of LSD down to the level at which it can maximally induce βarr2 recruitment itself. Thus, in the βarr2 assay, lisuride acted as a partial agonist/antagonist to block LSD-mediated activity at 5-HT2A. For the miniGαq recruitment assay, the results were slightly different, consistent with a weaker partial agonism displayed by lisuride in that setup. Again, in the presence of a low concentration of lisuride, 100 nM LSD was able to induce the recruitment of miniGαq to the receptor to the same extent as when no lisuride was present. Increasing lisuride concentrations strongly reduced this recruitment of miniGαq, indicating that lisuride can fully antagonize the LSD-induced functional activity at 5-HT2A in this assay.

We must acknowledge some differences between the presently used and other 5-HT2A receptor functional assays. All in vitro assays used to study 5-HT2A activation inherently entail both advantages and limitations (see Pottie and Stove).45 For example, assays like the presently used miniGq recruitment assay measure an event upstream of distal downstream signaling cascades, which can be advantageous to directly study 5-HT2A activation. However, measurement of signaling events proximal to receptor activation may not fully recapitulate downstream signal amplification of assays measuring events more distal to the receptor. Conversely, distal downstream signaling cascades may have undergone substantial signal amplification, making it difficult to distinguish between full and partial agonists. Moreover, different experimental setups may have an impact on the obtained data, with the temperature at which the assay is performed and the readout time as specific examples in the context of 5-HT2A signaling induced by ergolines.46,47 Considerations inherent to the currently used recruitment assay are the fact that both the receptor and cytosolic protein are fused to small enzyme fragments, which may influence receptor function, and the use of the artificially engineered miniGq protein. It is therefore important to note differences between this assay and other assay systems measuring 5-HT2A receptor activation.

Affinities of Lisuride and LSD at 5-HT1A and 5-HT2A Receptors in Mouse Brain

We next assessed the binding affinities (Ki values) of lisuride and LSD at the 5-HT1A and 5-HT2A receptors. To this end, competition binding assays were carried out in mouse brain tissue using the 5-HT1A agonist [3H]8-OH-DPAT or 5-HT2A antagonist [3H]M100907. Lisuride and LSD displayed high affinities at both receptors in the low nM range (2–6 nM, Table 1 and Figure S2), consistent with previous radioligand binding studies.48−50 Additionally, control compounds 8-OH-DPAT and DOI displayed the expected low nM inhibition constants for [3H]8-OH-DPAT (1 nM) and [3H]M100907 (6 nM) binding, respectively (Table 1 and Figure S2).

Table 1. Inhibition Constants (Ki) in Mouse Brain Binding Assays as well as Potency (ED50) and Maximum Observed Effects (Emax) for In Vivo Tests in Mice Comparing Lisuride and LSDa.

| affinity-mouse brain |

potency & efficacy–mouse |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [3H]8-OH-DPAT binding m5-HT1A | [3H]M100907 binding m5-HT2A | HTR | temperature Δ | hypolocomotion | |

| ligand | Ki (nM) | Ki (nM) | ED50 (μg/kg s.c.) | ED50 (μg/kg s.c.) | ED50 (μg/kg s.c.) |

| lisuride | 2.2 (1.5–3.1) | 6.0 (4.9–7.1) | 6b (0.8–16) | 23 (17–32) | 8 (5–15) |

| Emax = −5.4 °C | Emax = 364 cm | ||||

| LSD | 2.1 (1.2–3.6) | 1.6 (1.3–1.9) | 39 (25–58) | 1620 (1218–2144) | 840 (475–1505) |

| Emax = 52 HTR | Emax = −3.1 °C | Emax = 758 cm | |||

m5-HT1A and m5-HT2A = mouse receptors and s.c. = subcutaneous drug administration. Parameters reported are expressed with 95% confidence intervals (CI) noted in parentheses. Ki values with 95% CI for DOI and 8-OH-DPAT at 5-HT2A and 5-HT1A receptors were 6.3 nM (4.5–8.6) and 0.8 nM (0.5–1.1), respectively.

Inhibition of basal spontaneous HTR.

Dose–Response of the Effects of Lisuride and LSD in Mice

Mouse studies were conducted to test the dose-related (0.001–3 mg/kg s.c.) acute effects of lisuride and LSD on HTR, body temperature, and locomotor activity over a 30 min testing session, using our previously reported methods.27,28,51 The resulting ED50 and Emax values can be found in Table 1, while mean effects for each dose and information about statistical comparisons can be found in Table S1. Lisuride displayed potent dose-related decreases in the HTR (ED50 = 6 μg/kg), along with hypothermia (ED50 = 23 μg/kg) and hypolocomotion (ED50 = 8 μg/kg) vs vehicle controls (Figure 3A–C and Table 1). In contrast, LSD induced robust dose-related increases in the HTR (ED50 = 39 μg/kg), while showing hypothermic and locomotor suppressive effects similar to lisuride at doses that were ∼70–100 times higher (ED50 = 800–1600 μg/kg) (Figure 3D–F and Table 1). Remarkably, the effects of lisuride were similar to those of the prototypical 5-HT1A agonist, 8-OH-DPAT, with lisuride being ∼6–30 times more potent across measures (Figure S3A–C and Table S2). Time-course plots of distance traveled during the session further illustrate the similarity in locomotor suppression induced by lisuride (0.01–3 mg/kg) and 8-OH-DPAT (0.1–30 mg/kg) vs LSD (0.3–3 mg/kg; Figure S4). Overall, these results from mice complement and extend previous findings from rats showing that lisuride produces 8-OH-DPAT-like effects, and does so much more potently than LSD.16,25

Figure 3.

Acute dose-related effects of lisuride and LSD in mice. Dose–response curves for lisuride (A–C) and LSD (D–F) were obtained for effects on HTR, body temperature, and distance traveled over the 30 min session. All values are the mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM) of n = 5–7.* = p < 0.05 vs vehicle control (0 mg/kg). More details regarding the pharmacological parameters determined and statistical comparisons made can be found in the Materials and Methods section and Tables 1 and S1.

In this study, lisuride failed to elicit any increase in the HTR and potently (ED50 = 6 μg/kg) reduced spontaneous HTR events relative to vehicle controls. This observation is consistent with findings from other groups that used much higher doses of lisuride in mice (≥400 μg/kg).2,3,7 Similar to lisuride, 8-OH-DPAT also reduced basal HTR events vs. vehicle controls (ED50 = 33 μg/kg). LSD showed the opposite effect, stimulating HTR with a typical inverted U-shaped dose–response curve, where the high doses (0.3–3 mg/kg) reduced total HTRs and compressed the time-course of effects (Figure S5A). The descending limb of the LSD HTR curve corresponded with the hypolocomotive and hypothermic effects seen at high doses and underscores the importance of using wide dose ranges when studying drug-induced HTRs. Notably, the observed potency for LSD-induced HTR shown here (39 μg/kg), is similar to the potency (ED50 = 53 μg/kg) and total number of events observed by other laboratories using the same strain of mice.2,3,35,87

Our dose–response studies show that lisuride produces very potent 5-HT1A agonist-like effects52,53 in the popularly used C57BL/6J mouse strain. Additionally, lisuride showed high potency for the reduction of spontaneous HTR. The present data show that the ED50 of lisuride to reduce spontaneous HTR events is ∼42–67 times lower than the lowest doses of lisuride (≥250–400 μg/kg) commonly employed in prior mouse studies.2,3,7,8 As a result, the present data indicate that conclusions drawn about the pharmacology of lisuride in mouse studies using doses higher than ∼5 μg/kg may be confounded by its potent 5-HT1A agonist-like effects, limiting hypothesis testing regarding its 5-HT2A-mediated effects. Findings from other recent studies of lisuride in mice support this, showing that lisuride produces potent acute 5-HT syndrome-like effects on motor activity and rearing behavior (0.01–4 mg/kg).9,54 These effects can affect the expression of the 5-HT2A-mediated HTR and other acutely expressed behaviors in rodents.

In contrast to the data shown here in mice, some studies have reported that lisuride induces hyperlocomotion in rats. For example, one study found that lisuride increases motor activity at doses of 200–500 μg/kg in Wistar rats,55 while others reported lisuride-induced hyperlocomotion in Sprague–Dawley rats, along with hypothermic effects.56,57 Drug discrimination experiments in Sprague–Dawley rats show that lisuride disrupts response rates at doses above 50–100 μg/kg, and similar doses evoke elements of the 5-HT behavioral syndrome, such as 5-HT1A-mediated ambulation, flat body posture, and forepaw treading.16,58 Thus, the apparent differences in behavioral manifestations of lisuride in rats vs mice could be related to the occurrence of elements of the 5-HT syndrome in rats, namely, ambulation and forepaw treading, which would be scored as locomotor activity. Others have postulated that lisuride has biphasic dose–response effects on locomotor activity in rats, with increased activity at high doses.59 In the least shrew, lisuride produced hyperlocomotion in addition to a robust HTR,60 and in other mouse studies, lisuride potently reduced motor activity and rearing (0.01–4 mg/kg).9,54 Taken together, the summed behavioral findings demonstrate key species differences in the effects of lisuride on motor activity, whereby the drug reliably suppresses locomotion in mice but enhances locomotion in rats, especially at high doses.

Role of 5-HT1A Receptors in the Effects of Lisuride and LSD

Given that we found lisuride to produce potent 8-OH-DPAT-like effects in mice, we next sought to verify whether these effects were mediated by 5-HT1A receptors. Additionally, since antagonism of 5-HT1A activity has been reported to enhance the 5-HT2A-mediated HTR induced by certain psychedelics,28,31 we also sought to test whether lisuride might induce HTR under conditions of 5-HT1A blockade. For these experiments, mice were pretreated with saline vehicle or the 5-HT1A antagonist WAY100635 (3 mg/kg s.c.), 30 min prior to administration of lisuride (0.02 mg/kg s.c.) or the comparator drugs LSD (3 mg/kg s.c. and 8-OH-DPAT (1 mg/kg s.c.) We chose these specific doses of lisuride, LSD, and 8-OH-DPAT because they produced similar efficacious reductions in locomotion and body temperature in the dose–response studies. Importantly, WAY100635 pretreatment did not produce any effect on locomotor activity or change in body temperature vs vehicle controls over the first 30 min prior to lisuride, LSD, or 8-OH-DPAT administration (Figure S6 and Tables S3 and S4).

Our results show that lisuride alone produced a significant reduction in basal HTR compared with the vehicle and antagonist control conditions. This reduction in HTR was prevented when mice were pretreated with WAY100635 (Figure 4A and Tables S3 and S4), but the number of HTRs was not elevated above control levels. The hypothermia and hypolocomotion induced by lisuride were also attenuated by WAY100635 pretreatment (Figure 4B,C and Tables S3 and S4). Interestingly, WAY100635 pretreatment prior to a high dose of LSD, which normally suppresses HTR (i.e., 3 mg/kg, corresponding to the descending limb of the HTR dose–response curve), produced a robust increase in HTR that was significant compared to all other groups, including vehicle + LSD (Figures 4D and S5B, Tables S3 and S4). The vehicle + LSD group also produced significant hypothermia vs all other groups, an effect that was blocked in the WAY100635 + LSD group (Figure 4E and Tables S3 and S4). It is noteworthy that the vehicle + LSD group did not exhibit significantly decreased locomotion relative to the other groups. The lack of effect of LSD on locomotion in this experiment differs from the findings in the dose–response studies and may be due to the longer habituation period used in the antagonist reversal studies (Figure 4F and Tables S3 and S4).28,61 Lastly, data for the effects of WAY100635 pretreatment in mice receiving 8-OH-DPAT mirrored the results for lisuride. Specifically, WAY100635 pretreatment reversed the 8-OH-DPAT-induced effects on basal HTR, hypothermia, and hypolocomotion (Figure S3D–F and Tables S3 and S4).

Figure 4.

Effects of WAY100635 pretreatment on acute effects of lisuride (A–C) and LSD (D–F). All data are mean with SEM (n = 5) and individual points plotted for total HTR count, body temperature change, and distance traveled. Bold points and symbols represent statistically significant differences (p < 0.05) via Tukey’s post-test as follows: *vs 0/0, # vs 3/0, ∧ vs 0/lisuride or LSD, + vs 3/lisuride or LSD. More details regarding statistical comparisons can be found in the Materials and Methods section and Tables S3 and S4.

Collectively, the results from these mouse studies support the hypothesis that the hypothermic and hypolocomotor effects of the compounds tested here involve 5-HT1A receptor activation. Furthermore, lisuride and 8-OH-DPAT suppress basal spontaneous HTR by a mechanism involving 5-HT1A. Interestingly, we found that the blockade of 5-HT1A completely reversed the suppression of HTR by high-dose LSD (3 mg/kg) and unmasked a fully efficacious HTR response. Consistent with our findings, a prior study showed that the LSD analogue LSM-775 does not increase HTR in mice unless mice are pretreated with the 5-HT1A antagonist WAY100635.31 In previous human studies, pretreating study participants with pindolol to antagonize 5-HT1A receptors enhanced the psychedelic subjective effects of intravenous N,N-dimethyltryptamine administration.62 Such results support a growing body of evidence that shows an inhibitory influence of 5-HT1A activation on psychedelic-like drug effects in rodents and humans.26−31,62,63

It is important to note that the inhibitory effect of lisuride on basal HTR was abrogated when blocking its 5-HT1A agonist activity, but no increase in the HTR above baseline control levels was observed. González-Maeso et al. previously used 5-HT1A knockout mice to test the role of this receptor in modulating HTR produced by LSD or lisuride.2 In 5-HT1A knockout mice, lisuride (0.4 mg/kg) did not induce the HTR, in agreement with the findings presented here. However, the effects of LSD (0.24 mg/kg) on HTR were not enhanced in 5-HT1A knockout mice, in apparent contrast to our results. One possible explanation for the discrepancy is that a global 5-HT1A knockout may trigger neuroadaptive mechanisms during development which compensate for the lack of this receptor, to functionally replace it. Another possibility for the discrepancy may be the different doses of LSD used between studies. At the lower dose of LSD used in the González-Maeso et al. study, 5-HT1A receptor activity may have less of a regulatory influence on 5-HT2A-mediated behavioral effects such as HTR. Regardless, the inability of lisuride to induce HTR in WAY100635-pretreated or 5-HT1A knockout mice suggests 5-HT1A-independent mechanisms in mediating the non-psychedelic properties of the drug.

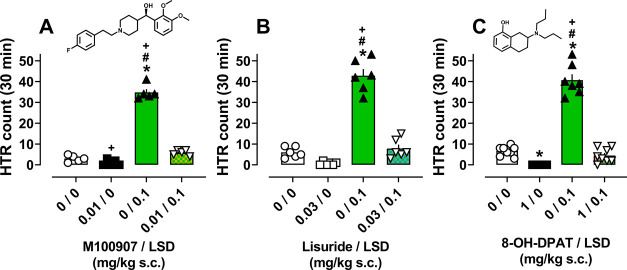

Effects of M100907, Lisuride, and 8-OH-DPAT on the LSD-Induced HTR

We next carried out experiments to verify that LSD (administered s.c. at 0.1 mg/kg) produces the HTR in a 5-HT2A-dependent manner. To test this, the 5-HT2A receptor antagonist64 M100907 (0.01 mg/kg) was administered 30 min prior to LSD. The vehicle + LSD group produced the expected increase in HTR, which was significantly higher than all other groups, with the M100907 + LSD group exhibiting a response indistinguishable from vehicle controls (Figures 5A and S5C and Tables S5 and S6). In accordance with previous studies from our laboratory, pretreatment with 0.01 mg/kg M100907 did not induce any effect on body temperature or locomotor activity before or after LSD administration (Figure S7A – C, Figure S8A – B, Table S5, Table S6).27,28 The finding that LSD-induced HTR is 5-HT2A-dependent is consistent with many other studies using pharmacological and genetic manipulations in mice, as well as clinical studies where the subjective effects of psilocybin or LSD are attenuated by pretreatment with ketanserin.2,35,65−69

Figure 5.

Effects of M100907 (A, structure shown), lisuride (B), and 8-OH-DPAT (C, structure shown) pretreatment on LSD-induced HTR. Data shown are mean with SEM (n = 6–8) and individual points plotted for total HTR count. Bold points and symbols represent statistically significant differences (p < 0.05) via Tukey’s post-test as follows: *vs 0/0, # vs pretreatment/0, ∧ vs 0/LSD, + vs pretreatment/LSD. More details regarding statistical comparisons can be found in the Materials and Methods section and Tables S5 and S6.

It has previously been shown that pretreatment or coadministration of 5-HT1A agonists reduces the effects of psychedelics in preclinical and clinical studies.29,30,63 Additionally, a higher dose of lisuride (0.4 mg/kg) has been shown to block LSD-induced HTR in mice.2 Therefore, we next sought to test whether a lower dose of lisuride that induces 5-HT1A-mediated effects can attenuate the 5-HT2A-mediated HTR by LSD. Mice were pretreated with lisuride (0.03 mg/kg s.c.) or 8-OH-DPAT (1 mg/kg s.c.) 15 min prior to administration of LSD (0.1 mg/kg s.c.) to monitor HTR, temperature changes, and locomotor activity for 30 min. Pretreatment with either lisuride or 8-OH-DPAT attenuated the LSD-induced HTR (Figures 5B–C and S5D–E and Tables S5 and S6). As expected, lisuride or 8-OH-DPAT pretreatment also produced hypolocomotor and hypothermic effects that were observable at the time point 15 min after administration of the drugs. These effects persisted through the end of the 30 min testing period after LSD administration (Figures S7 and S8 and Tables S5 and S6). Despite its 5-HT1A activity at higher doses, 0.1 mg/kg LSD did not influence the effects of lisuride or 8-OH-DPAT on body temperature or locomotor activity in these experiments.

Role of D1, D2, and 5-HT2C Receptors in the Effects of Lisuride

In addition to its affinity for 5-HT2A and 5-HT1A, lisuride has other receptor targets that potentially influence its biological effects, including its discriminative stimulus properties (e.g., dopamine receptors and other serotonin receptors).16,18,70−73 Given that we found that (i) lisuride does not produce an increase in the HTR (Figure 3), (ii) lisuride fails to induce HTRs under conditions of 5-HT1A blockade (Figure 4), and (iii) lisuride antagonizes LSD-induced HTR (Figure 5),2 we sought to test whether other pharmacologically relevant targets of lisuride might be responsible for its lack of psychedelic-like effects in mice. These experiments explored the effects of pretreatments with antagonists at D1-like (SCH23390, 0.01 mg/kg s.c.), D2-like (eticlopride, 0.03 mg/kg s.c.), or 5-HT2C (SB242084, 3 mg/kg s.c.) receptors as well as some antagonist combinations given 15 min prior to lisuride (0.03 mg/kg s.c.).

The results shown in Figure 6 indicate that none of the pretreatments with antagonists acting at D1, D2, D1 + D2, 5-HT2C, 5-HT2C + 5-HT1A, or D1 + D2 + 5-HT1A unveiled an increase in HTR activity of lisuride (Tables S7–S10). In fact, several of the antagonist pretreatments or their combinations significantly reduced basal HTR relative to saline vehicle controls, analogous to the vehicle+lisuride and antagonists+lisuride conditions. These results suggest that there is no masking of latent HTR by these various targets in vivo. Notably, many neurotransmitter systems can influence the HTR produced by psychedelics in mice,74,75 so blockade of some of the targets assessed may influence critical circuitry responsible for mice to display the HTR.

Figure 6.

Effects of blockade of various non-5-HT2A receptor targets of lisuride on the HTR. Effects of SCH23390 (A), eticlopride (B), SCH23390 + eticlopride (C), SB242084 (D), SB242084 + WAY100635 (E), and WAY100635 + eticlopride + SCH23390 (F) pretreatment on lisuride-induced reductions in basal HTR. Data shown are mean with SEM (n = 4–6) and individual points plotted for total HTR count. Symbols and bold points represent statistically significant differences (p < 0.05) via Tukey’s post-test as follows: *vs 0/0, # vs pretreatment/0, ∧ vs 0/lisuride, + vs pretreatment/lisuride. More details regarding statistical comparisons can be found in the Materials and Methods section and Tables S7–S10.

Pretreatment with the D1-like receptor antagonist SCH23390 alone resulted in decreased locomotor activity 45 min post administration (as assessed in the 30 min post lisuride time point) but had no effect on body temperature or the effects of lisuride (Figures S9A–C and S10A–B and Tables S7–S8). Similarly, a D2-like receptor blockade with eticlopride reduced locomotor activity after 45 min. Pretreatment with eticlopride did not affect lisuride-induced hypolocomotion but did partially attenuate lisuride-induced hypothermia (Figures S9D–F and S10C–D and Tables S7–S8). These results show that the activity of lisuride at D2-like receptors can modulate the pathways responsible for its effects on body temperature. When both D1-like and D2-like receptors were blocked, the observed effects resembled the effects of eticlopride alone, with the combination partially attenuating the hypothermia induced by lisuride (Figures S9G–I and S10E–F and Tables S7–S8).

5-HT2C receptor blockade with SB242084 did not significantly influence the locomotor effects of lisuride despite a trend for motor stimulation produced by the antagonist alone (Figure S11A–C and Tables S9–S10). Interestingly, 5-HT2C blockade seemed to enhance lisuride-induced hypothermia (Figure S12A–B and Tables S9–S10). Combining a 5-HT2C antagonist with the 5-HT1A antagonist, WAY100635, produced significant hyperlocomotion prior to lisuride administration, without altering effects on body temperature (Figures S11D–F and S12C,D and Tables S9–S10). Lastly, blocking 5-HT1A + D1 + D2 receptors together significantly reduced locomotor activity post lisuride administration (Figure S11G–I and Tables S9–S10), and partially attenuated lisuride-induced hypothermia (Figure S12E–F and Tables S9–S10). The overall results from these studies reveal that the blockade of many non-5-HT2A receptor targets of lisuride could not unmask suppressed psychedelic-like effects of the drug.

Despite the known dopaminergic effects of lisuride, blockade of the D1-like and D2-like receptor activities of lisuride in the present study did not reveal any 5-HT2A-mediated psychedelic-like effects on the HTR. González-Maeso et al. similarly investigated the effects of D1-like and D2-like agonists on effects of LSD, showing that these targets likely do not play a role in differential effects of lisuride vs LSD.2 Blocking combinations of D1-like, D2-like, or 5-HT2C receptors with or without additional 5-HT1A blockade further failed to reveal any HTR increase by lisuride. These data refute the hypothesis that non-5-HT2A receptor targets inhibit lisuride from producing psychedelic-like effects.

Integration of In Vitro and In Vivo Findings

Taken together, the results from this study confirm and extend previous findings related to the pharmacological effects of lisuride and LSD. We found that lisuride is a weak partial agonist at 5-HT2A, with particularly low efficacy at recruiting Gαq. Consistent with its low efficacy at 5-HT2A, lisuride could antagonize signaling at this receptor induced by LSD (Figure 2). One other study found that lisuride blocks the effects of LSD on the electrical properties of somatosensory neurons and induction of immediate early gene expression in mouse brain.2 Moreover, the same previous study and our present data (Figure 5B) both indicate that lisuride is capable of blocking the 5-HT2A-mediated effects of LSD on HTR in mice. Furthermore, a recent study has shown that βarr1 and βarr2 agonist-like signaling at 5-HT2A does not play a significant role in the behavioral effects of lisuride in mice.54 Together, these findings provide compelling and convergent evidence supporting the hypothesis that the partial agonist/antagonist profile of lisuride at 5-HT2A can be linked to its antagonism of the LSD-induced HTR and its inability to induce HTR. Supporting this notion, Lewis et al. recently reported that 2-Br-LSD, a non-hallucinogenic LSD analogue with a potential application for the treatment of mood disorders, acted as a potent but partial 5-HT2A agonist.44 In the study presented here, we found that lisuride and 2-Br-LSD displayed nearly equivalent partial agonist effects in βarr2 and miniGαq recruitment assays. Similar to lisuride, 2-Br-LSD does not induce the HTR in vivo.44

In addition to lisuride, our study evaluated the in vitro functional activity of several related ergolines. AL-LAD has been detected in recreational drug markets in both powdered and blotter forms.76 Its synthesis and psychedelic properties in humans are documented in TiHKAL.77 In drug discrimination studies, AL-LAD exhibited a higher potency than LSD in rats trained to discriminate LSD from saline, and AL-LAD induces HTR in mice with a slightly lower potency than LSD.76,78 Scarce pharmacological information is available about the related compound, LAMPA. In a study assessing the effects of 100 μg p.o. of LAMPA in six psychedelic-experienced subjects, two subjects reported effects reminiscent of a threshold dose of LSD, whereas four others did not report subjective effects.79 Data obtained for LAMPA in HTR experiments indicate a potency for psychedelic-like effects approximately 3-fold lower than that of LSD (ED50 = 116 vs 39 μg/kg).3,80 The present in vitro functional activities for these compounds generally agree with the existing literature, showing that LSD, AL-LAD, and LAMPA exhibit differences in their activation of 5-HT2A, as assessed by βarr2 and miniGαq recruitment assays.

Several hypotheses have been proposed to explain mechanistic differences between psychedelic and non-psychedelic 5-HT2A ligands. In a study comparing effects of the non-psychedelic 5-HT2A agonist, 2,5-dimethoxy-4-methyl-α-ethylphenethylamine (Ariadne), to those of the structurally related psychedelic 2,5-dimethoxy-4-methyl-amphetamine (DOM), Ariadne displayed a decrease in signaling potency and efficacy in several 5-HT2A-coupled functional pathways in vitro.81 No apparent change in preference toward either pathway was reported. In the same study, the authors proposed a “5-HT2A signaling efficacy hypothesis” to explain the lack of psychedelic effects for Ariadne, with a caveat that the hypothesis may be restricted to the comparison of structurally related analogues. Other evidence supports the idea that signaling bias at 5-HT2A may differentiate 5-HT2A agonists with and without psychedelic-like effects. A recent drug screening and optimization effort identified Gαq-biased 5-HT2A agonists with anxiolytic-like and antidepressant effects in mouse models, but which lack psychedelic-like effects.82 On the other hand, a different study found βarr2-biased 5-HT2A partial agonists that produce antidepressant activity without psychedelic-like effects.8 The latter study posited that drugs producing psychedelic-like effects require high transduction efficiency in both βarr2 and Gαq signaling pathways,8 which is consistent with the present observations for lisuride and a previous study of 2-Br-LSD44 vs other psychoactive ergolines, including LSD. Adding to the complexity, a recently published study highlights the importance of Gαq signaling in mediating the psychedelic-like effects of some 5-HT2A agonists in mice, showing that a "Gαq-efficacy threshold" of >70%, as measured in an in vitro BRET G protein dissociation assay, is required for a compound to produce the HTR.87

Two previous studies reported partial 5-HT2A agonist efficacy for lisuride and LSD, when compared to the endogenous neurotransmitter serotonin, in a phosphatidyl inositol hydrolysis assay (13–16 and 22–32% relative to serotonin, respectively).16,21 In the psychLight assay, which is based on a conformational change of 5-HT2A induced by psychedelic substances, lisuride did not display detectable activity, whereas LSD acted as a partial agonist.83 Of note, other studies report higher relative efficacies of lisuride (and LSD) relative to serotonin as a reference agonist. For example, Cussac et al. reported efficacies for lisuride of 40.7 and 48.6% relative to serotonin in a GTPγS and a Ca2+ mobilization assay, respectively.84 Similarly, Egan et al. reported that LSD and lisuride display similar Emax values of 32 and 25% relative to serotonin in a PI hydrolysis assay.5 Meanwhile, recent data from Wallach et al. found that LSD is an efficacious agonist at 5-HT2A for Gαq signaling and dose-dependently induces the HTR in mice, while lisuride does not achieve >70% the Emax of 5-HT and does not induce the HTR.87 Regardless of apparent differences across assays, together the collective findings suggest that there may be an “efficacy threshold” in one or both 5-HT2A signaling pathways that is required to produce psychedelic subjective effects in humans and psychedelic-like effects in rodents.

Conclusions

In summary, the results presented here demonstrate that lisuride induces potent 5-HT1A-mediated effects in mice that confound its ability to be used acutely as a “non-psychedelic” or “non-hallucinogenic” 5-HT2A agonist. Importantly, antagonism of 5-HT1A did not reveal latent psychedelic-like activity for lisuride, contrary to what has been observed for other psychedelic 5-HT2A agonists. At the receptor level, lisuride displayed weak partial agonism in both in vitro assays that monitor the recruitment of intracellular proteins to 5-HT2A, with particularly low efficacy in the miniGαq recruitment assay, which set it apart from LSD and related psychedelic analogues. Thus, the summed findings suggest that weak partial agonist activity at 5-HT2A likely underlies the non-psychedelic nature of lisuride.

Materials and Methods

Materials and Reagents

In Vitro Studies

Lisuride maleate (#4052) was purchased from Bio-Techne and dissolved in DMSO. The analytical standards of AL-LAD (#30442), LAMPA (#31500), and 2-Br-LSD (#36791) were procured from Sanbio (distributor for Cayman Chemical), while lysergic acid diethylamide and DOI hydrochloride were purchased from Chiron AS. DMEM (Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium, GlutaMAX), OptiMEM, penicillin/streptomycin, and HBSS (Hank’s Balanced Salt Solution) were purchased from Fisher Scientific. Poly-d-lysine hydrobromide and serotonin were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. FuGENE HD transfection reagent and NanoGlo Live Cell Reagent were purchased from Promega.

In Vivo Studies

Lisuride maleate (#4052), 8-OH-DPAT hydrobromide (#0529), (+)-SCH 23390 hydrochloride (#0925), and SB 242084 (#2901) were all procured from Tocris Biosciences. (+)-Lysergic acid diethylamide (+)-tartrate (2:1) was generously provided by the National Institute on Drug Abuse Drug Supply Program. (+)-M100907 freebase was generously provided by the laboratory of Kenner Rice, Ph.D. for antagonist studies. WAY100635 maleate (#14599) and DOI hydrochloride (#13885) were purchased from Cayman Chemical Company. (−)-Eticlopride hydrochloride (#E-101) was purchased from Research Biochemicals International. All drugs were administered subcutaneously as the weight of the salt dissolved or diluted in a sterile 0.9% saline vehicle at an injection volume of 0.01 mL/g body weight. For the administration of drug combinations, the appropriate concentrations of drug solutions were diluted together and coadministered as a combined solution in a single injection.

5-HT2A Functional Assays

The protocols for the functional complementation assays monitoring the recruitment of β-arrestin 2 (βarr2) or the engineered miniGαq protein (as described by Nehmé et al.)38 to 5-HT2A have been described previously.33,34,40,41 Human Embryonic Kidney (HEK) 293T cells were routinely cultured in a humidified atmosphere at 37 °C and 5% CO2. The culturing medium was DMEM containing 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS), 100 IU/mL of penicillin, 100 μg/mL of streptomycin, and 0.25 μg/mL amphotericin B. For transient transfection, the cells were seeded in a 6-well plate at a density of 500,000 cells per well. The following day, the cells are transfected with 1.65 μg of 5-HT2A-LgBiT and 1.65 μg of either SmBiT-βarr2 or SmBiT-miniGαq, utilizing FuGENE HD transfection reagent in a 3:1 FuGENE/DNA ratio. The transfection mixture is prepared in OptiMEM, according to the manufacturer’s protocol.

24 h post transfection, the cells are reseeded into a poly-d-lysine-coated white 96-well plate. The readout takes place on the next day (in total 48 h post transfection). The cells are rinsed twice with HBSS, and 100 μL of HBSS is pipetted into each well, to which 25 μL of NanoGlo Live Cell Substrate is added (diluted 1/20 in LCS dilution buffer, according to the manufacturer’s protocol). The plate is transferred to a Tristar2 LB 942 multimode microplate reader (Berthold Technologies GmbH & Co., Germany), where luminescence is monitored until equilibration of the signal. Subsequently, 10 μL of the 13.5× concentrated agonist solutions are added, to obtain in-well concentrations ranging from 10–5 to 10–11 M, alongside the appropriate solvent controls. Luminescence is continuously monitored for 2 h. Each experiment additionally included LSD, serotonin, and DOI as reference agonists for normalization and comparability with previous results. Data are gathered in three independent experiments, each including at least two replicates for each solvent control or ligand concentration point.

Mouse Studies

Male C57BL/6J mice (#000664) were purchased from the Jackson Laboratory and group housed under a 12:12 light–dark cycle (lights on at 7AM) for 1–2 weeks for facility acclimation with ad libitum access to food and water. After acclimation and under brief isoflurane immobilization, the mice were subcutaneously implanted with a temperature transponder (14 mm × 2 mm, model IPTT-300, Bio Medic Data Systems, Inc.) and allowed 1 week to recover prior to experiments as previously described.27,85 All mouse experiments were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee in facilities at the National Institute on Drug Abuse Intramural Research Program in Baltimore, MD.

Mouse studies were conducted as described previously with little modification.27,28 Briefly, cohorts of 12 C57BL/6J male mice (2–5 months, one cohort per drug) were tested for acute dose-related effects of lisuride, 8-OH-DPAT, or LSD once per week for 4–5 weeks. Similarly, separate cohorts of mice were used to test the effects of antagonist pretreatments on the effects of lisuride, 8-OH-DPAT, and LSD. For acute effects in dose–response studies, various doses of each test drug (0.001–30 mg s.c.) were administered and the HTR was recorded and scored from 30 min video recordings (GoPro Hero 7, 120 frames/s, 960P resolution).51 At the same time, locomotor activity was recorded via modified photobeam array chambers (TruScan, Coulbourne Instruments) and pre (just prior to drug administration after a 5 min chamber acclimation) to post-test session body temperature (30 min post drug administration) was measured using a hand-held device (Bio Medic Data Systems, Inc.) to read implanted transponders. For antagonist studies, antagonist drugs were administered either 15 or 30 min prior to test drugs, and the same end points measured in dose–response studies were monitored.

Data Analyses

In Vitro Studies

Data are analyzed as described before in more detail.86 In brief, the data are plotted in Microsoft Excel as time-luminescence profiles, corrected for interwell variability, and the area under the curve (AUC) is calculated. Upon subtracting the AUC of the corresponding solvent control (“blank”), the data are normalized in GraphPad Prism software (San Diego, CA), with the maximal response (Emax – as defined by a three parametric nonlinear regression) of reference agonist LSD or 5-HT defined as 100% in each individual experiment. The normalized data from the individual experiments are pooled, and the means of the data points are used to fit sigmoidal concentration–response curves through three parametric nonlinear regression, allowing one to calculate EC50 and Emax values.

In Vivo Studies

Nonlinear regression with either three- or four-parameter fits were utilized to construct concentration- and dose–response curves as well as to determine potencies and maximum values (ED50, Emax). In some cases (LSD HTR, lisuride locomotor activity), a “bell-shaped” nonlinear regression function was most appropriate to visually depict biphasic data. In these instances, the rising phase of the curves was used to determine ED50 potency values separately. Dose–response data for mean HTR count, temperature change (°C), and locomotor activity (distance traveled cm) were compared to saline vehicle control mice via one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s post-test. Effects in antagonist studies using the same end points were also compared via one-way ANOVA, but with Tukey’s post-test to assess all potential treatment group comparisons. Further information regarding statistical comparisons in mouse studies (group means, n values, p values, F statistics, degrees of freedom, etc.) can be found in the figure legends or in the Supporting Information.

Acknowledgments

Special thanks goes to K. Rice and A. Sulima for generously providing the M100907 used to complete a portion of the present study. The authors also thank the National Institute on Drug Abuse Drug Supply Program for their continued support of our research program.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- 5-HT

serotonin or 5-hydroxy-tryptamine

- 5-HT1A

serotonin 1A receptor

- 5-HT2A

serotonin 2A receptor

- 5-HT2C

serotonin 2C receptor

- D1

dopamine D1 receptor

- D2

dopamine D2 receptor

- LSD

lysergic acid diethylamide

- LSM-775

lysergic acid morpholide

- DOI

2,5-dimethoxy-4-iodoamphetamine

- AL-LAD

6-allyl-6-nor-lysergic acid diethylamide

- LAMPA

lysergic acid methylpropylamide

- 2-Br-LSD

2-bromolysergic acid diethylamide

- HTR

head twitch response

- ariadne

2,5-dimethoxy-4-methyl-α-ethylphenethylamine

- DOM

2,5-dimethoxy-4-methyl-amphetamine

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsptsci.3c00192.

In vitro functional assay concentration–response curves extended; concentration–response curves for mouse brain binding assays; mouse dose–response statistical table; mouse data for 8-OH–DPAT; mouse potency values for 8-OH-DPAT; locomotor activity time-course plots; HTR time-course plots; effects of WAY100635 on locomotor activity and body temperature; descriptive statistics for WAY100635 antagonist experiments; descriptive statistics for M100907, lisuride, and 8-OH-DPAT antagonist experiments; locomotor activity and temperature change plots for M100907, lisuride, and 8-OH-DPAT antagonist experiments; descriptive statistics for D1/D2/5-HT2C antagonist experiments; and locomotor activity and temperature change plots for D1/D2/5-HT2C antagonist experiments (PDF)

Author Contributions

§ G.C.G. and E.P. contributed equally to this work. Study design: G.C.G., E.P., C.P.S., M.H.B. 5-HT2A functional assays: E.P. Mouse brain binding assays: J.S.P. Mouse experiments: G.C.G. The manuscript was originally drafted by G.C.G. with help from E.P. and critically reviewed by C.P.S. and M.H.B. The final version was approved by all authors.

This work was supported by National Institute of Drug Abuse Intramural Research Program funds to M.H.B. (DA000522–16).

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Herrmann W. M.; Horowski R.; Dannehl K.; Kramer U.; Lurati K. Clinical Effectiveness of Lisuride Hydrogen Maleate: A Double-Blind Trial Versus Methysergide. Headache: J. Head Face Pain 1977, 17, 54–60. 10.1111/j.1526-4610.1977.hed1702054.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- González-Maeso J.; Weisstaub N. V.; Zhou M.; Chan P.; Ivic L.; Ang R.; Lira A.; Bradley-Moore M.; Ge Y.; Zhou Q.; Sealfon S. C.; Gingrich J. A. Hallucinogens Recruit Specific Cortical 5-HT2A Receptor-Mediated Signaling Pathways to Affect Behavior. Neuron 2007, 53, 439–452. 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halberstadt A. L.; Geyer M. A. Characterization of the head-twitch response induced by hallucinogens in mice: detection of the behavior based on the dynamics of head movement. Psychopharmacology 2013, 227, 727–739. 10.1007/s00213-013-3006-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horowski R. Psychiatric side-effects of high-dose lisuride therapy in parkinsonism. Lancet 1986, 328, 510 10.1016/s0140-6736(86)90374-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egan C. T.; Herrick-Davis K.; Miller K.; Glennon R. A.; Teitler M. Agonist activity of LSD and lisuride at cloned 5HT2A and 5HT2C receptors. Psychopharmacology 1998, 136, 409–414. 10.1007/s002130050585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pieri L.; Keller H. H.; Burkard W.; Da Prada M. Effects of lisuride and LSD on cerebral monoamine systems and hallucinosis. Nature 1978, 272, 278–280. 10.1038/272278a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de la Fuente Revenga M.; Jaster A. M.; McGinn J.; Silva G.; Saha S.; González-Maeso J. Tolerance and Cross-Tolerance among Psychedelic and Nonpsychedelic 5-HT(2A) Receptor Agonists in Mice. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2022, 13, 2436–2448. 10.1021/acschemneuro.2c00170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao D.; Yu J.; Wang H.; Luo Z.; Liu X.; He L.; Qi J.; Fan L.; Tang L.; Chen Z.; Li J.; Cheng J.; Wang S. Structure-based discovery of nonhallucinogenic psychedelic analogs. Science 2022, 375, 403–411. 10.1126/science.abl8615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y.; Liu J.; Yao Y.; Yan H.; Su R. Rearing behaviour in the mouse behavioural pattern monitor distinguishes the effects of psychedelics from those of lisuride and TBG. Front. Pharmacol. 2023, 14, 1021729 10.3389/fphar.2023.1021729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X.; Zhu H.; Gao H.; Tian X.; Tan B.; Su R. G(s) signaling pathway distinguishes hallucinogenic and nonhallucinogenic 5-HT(2A)R agonists induced head twitch response in mice. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2022, 598, 20–25. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2022.01.113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qu Y.; Chang L.; Ma L.; Wan X.; Hashimoto K. Rapid antidepressant-like effect of non-hallucinogenic psychedelic analog lisuride, but not hallucinogenic psychedelic DOI, in lipopolysaccharide-treated mice. Pharmacol., Biochem. Behav. 2023, 222, 173500 10.1016/j.pbb.2022.173500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- González-Maeso J.; Yuen T.; Ebersole B. J.; Wurmbach E.; Lira A.; Zhou M.; Weisstaub N.; Hen R.; Gingrich J. A.; Sealfon S. C. Transcriptome fingerprints distinguish hallucinogenic and nonhallucinogenic 5-hydroxytryptamine 2A receptor agonist effects in mouse somatosensory cortex. J. Neurosci. 2003, 23, 8836–8843. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-26-08836.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- González-Maeso J.; Sealfon S. C. Agonist-trafficking and hallucinogens. Curr. Med. Chem. 2009, 16, 1017–1027. 10.2174/092986709787581851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee A. A.; Vaidya V. A. Differential signaling signatures evoked by DOI versus lisuride stimulation of the 5-HT(2A) receptor. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2020, 531, 609–614. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2020.08.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karaki S.; Becamel C.; Murat S.; la Cour C. M.; Millan M. J.; Prézeau L.; Bockaert J.; Marin P.; Vandermoere F. Quantitative phosphoproteomics unravels biased phosphorylation of serotonin 2A receptor at Ser280 by hallucinogenic versus nonhallucinogenic agonists. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 2014, 13, 1273–1285. 10.1074/mcp.M113.036558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marona-Lewicka D.; Kurrasch-Orbaugh D. M.; Selken J. R.; Cumbay M. G.; Lisnicchia J. G.; Nichols D. E. Re-evaluation of lisuride pharmacology: 5-hydroxytryptamine1A receptor-mediated behavioral effects overlap its other properties in rats. Psychopharmacology 2002, 164, 93–107. 10.1007/s00213-002-1141-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halberstadt A. L.; Geyer M. A. LSD but not lisuride disrupts prepulse inhibition in rats by activating the 5-HT(2A) receptor. Psychopharmacology 2010, 208, 179–189. 10.1007/s00213-009-1718-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham K. A.; Callahan P. M.; Craigmyle N. A.; Appel J. B. Discriminative stimulus properties of clonidine: substitution by ergot derivatives. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1985, 119, 225–229. 10.1016/0014-2999(85)90299-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White F. J. Comparative effects of LSD and lisuride: clues to specific hallucinogenic drug actions. Pharmacol., Biochem. Behav. 1986, 24, 365–379. 10.1016/0091-3057(86)90367-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newman-Tancredi A.; Cussac D.; Quentric Y.; Touzard M.; Verrièle L.; Carpentier N.; Millan M. J. Differential actions of antiparkinson agents at multiple classes of monoaminergic receptor. III. Agonist and antagonist properties at serotonin, 5-HT(1) and 5-HT(2), receptor subtypes. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2002, 303, 815–822. 10.1124/jpet.102.039883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabin R. A.; Regina M.; Doat M.; Winter J. C. 5-HT2A receptor-stimulated phosphoinositide hydrolysis in the stimulus effects of hallucinogens. Pharmacol., Biochem. Behav. 2002, 72, 29–37. 10.1016/S0091-3057(01)00720-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millan M. J.; Maiofiss L.; Cussac D.; Audinot V.; Boutin J. A.; Newman-Tancredi A. Differential actions of antiparkinson agents at multiple classes of monoaminergic receptor. I. A multivariate analysis of the binding profiles of 14 drugs at 21 native and cloned human receptor subtypes. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2002, 303, 791–804. 10.1124/jpet.102.039867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newman-Tancredi A.; Cussac D.; Audinot V.; Nicolas J. P.; De Ceuninck F.; Boutin J. A.; Millan M. J. Differential actions of antiparkinson agents at multiple classes of monoaminergic receptor. II. Agonist and antagonist properties at subtypes of dopamine D(2)-like receptor and alpha(1)/alpha(2)-adrenoceptor. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2002, 303, 805–814. 10.1124/jpet.102.039875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goetz C. G.; Koller W. C.; Poewe O.; et al. DA agonists -- ergot derivatives: Lisuride. Mov. Disord. 2002, 17, S74–S78. 10.1002/mds.5565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millan M. J.; Bervoets K.; Colpaert F. C. 5-hydroxytryptamine (5-HT)1A receptors and the tail-flick response. I. 8-hydroxy-2-(di-n-propylamino) tetralin HBr-induced spontaneous tail-flicks in the rat as an in vivo model of 5-HT1A receptor-mediated activity. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1991, 256, 973–982. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein L. M.; Cozzi N. V.; Daley P. F.; Brandt S. D.; Halberstadt A. L. Receptor binding profiles and behavioral pharmacology of ring-substituted N,N-diallyltryptamine analogs. Neuropharmacology 2018, 142, 231–239. 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2018.02.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glatfelter G. C.; Pottie E.; Partilla J. S.; Sherwood A. M.; Kaylo K.; Pham D. N. K.; Naeem M.; Sammeta V. R.; DeBoer S.; Golen J. A.; Hulley E. B.; Stove C. P.; Chadeayne A. R.; Manke D. R.; Baumann M. H. Structure-Activity Relationships for Psilocybin, Baeocystin, Aeruginascin, and Related Analogues to Produce Pharmacological Effects in Mice. ACS Pharmacol. Transl. Sci. 2022, 5, 1181–1196. 10.1021/acsptsci.2c00177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glatfelter G. C.; Naeem M.; Pham D. N. K.; Golen J. A.; Chadeayne A. R.; Manke D. R.; Baumann M. H. Receptor Binding Profiles for Tryptamine Psychedelics and Effects of 4-Propionoxy-N,N-dimethyltryptamine in Mice. ACS Pharmacol. Transl. Sci. 2023, 6, 567–577. 10.1021/acsptsci.2c00222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darmani N. A.; Martin B. R.; Pandey U.; Glennon R. A. Do functional relationships exist between 5-HT1A and 5-HT2 receptors?. Pharmacol., Biochem. Behav. 1990, 36, 901–906. 10.1016/0091-3057(90)90098-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schreiber R.; Brocco M.; Audinot V.; Gobert A.; Veiga S.; Millan M. J. (1-(2,5-dimethoxy-4 iodophenyl)-2-aminopropane)-induced head-twitches in the rat are mediated by 5-hydroxytryptamine (5-HT) 2A receptors: modulation by novel 5-HT2A/2C antagonists, D1 antagonists and 5-HT1A agonists. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1995, 273, 101–112. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandt S. D.; Kavanagh P. V.; Twamley B.; Westphal F.; Elliott S. P.; Wallach J.; Stratford A.; Klein L. M.; McCorvy J. D.; Nichols D. E.; Halberstadt A. L. Return of the lysergamides. Part IV: Analytical and pharmacological characterization of lysergic acid morpholide (LSM-775). Drug Test. Anal. 2018, 10, 310–322. 10.1002/dta.2222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh S.; Botvinnik A.; Shahar O.; Wolf G.; Yakobi C.; Saban M.; Salama A.; Lotan A.; Lerer B.; Lifschytz T. Effect of psilocybin on marble burying in ICR mice: role of 5-HT1A receptors and implications for the treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder. Transl. Psychiatry 2023, 13, 164 10.1038/s41398-023-02456-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pottie E.; Cannaert A.; Van Uytfanghe K.; Stove C. P. Setup of a Serotonin 2A Receptor (5-HT2AR) Bioassay: Demonstration of Its Applicability To Functionally Characterize Hallucinogenic New Psychoactive Substances and an Explanation Why 5-HT2AR Bioassays Are Not Suited for Universal Activity-Based Screening of Biofluids for New Psychoactive Substances. Anal. Chem. 2019, 91, 15444–15452. 10.1021/acs.analchem.9b03104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pottie E.; Dedecker P.; Stove C. P. Identification of psychedelic new psychoactive substances (NPS) showing biased agonism at the 5-HT(2A)R through simultaneous use of β-arrestin 2 and miniGα(q) bioassays. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2020, 182, 114251 10.1016/j.bcp.2020.114251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguiz R. M.; Nadkarni V.; Means C. R.; Pogorelov V. M.; Chiu Y.-T.; Roth B. L.; Wetsel W. C. LSD-stimulated behaviors in mice require β-arrestin 2 but not β-arrestin 1. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 17690 10.1038/s41598-021-96736-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nardou R.; Sawyer E.; Song Y. J.; Wilkinson M.; Padovan-Hernandez Y.; de Deus J. L.; Wright N.; Lama C.; Faltin S.; Goff L. A.; Stein-O’Brien G. L.; Dölen G. Psychedelics reopen the social reward learning critical period. Nature 2023, 618, 790–798. 10.1038/s41586-023-06204-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixon A. S.; Schwinn M. K.; Hall M. P.; Zimmerman K.; Otto P.; Lubben T. H.; Butler B. L.; Binkowski B. F.; Machleidt T.; Kirkland T. A.; Wood M. G.; Eggers C. T.; Encell L. P.; Wood K. V. NanoLuc Complementation Reporter Optimized for Accurate Measurement of Protein Interactions in Cells. ACS Chem. Biol. 2016, 11, 400–408. 10.1021/acschembio.5b00753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nehmé R.; Carpenter B.; Singhal A.; Strege A.; Edwards P. C.; White C. F.; Du H.; Grisshammer R.; Tate C. G. Mini-G proteins: Novel tools for studying GPCRs in their active conformation. PLoS One 2017, 12, e0175642 10.1371/journal.pone.0175642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pottie E.; Cannaert A.; Stove C. P. In vitro structure-activity relationship determination of 30 psychedelic new psychoactive substances by means of β-arrestin 2 recruitment to the serotonin 2A receptor. Arch. Toxicol. 2020, 94, 3449–3460. 10.1007/s00204-020-02836-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pottie E.; Kupriyanova O. V.; Brandt A. L.; Laprairie R. B.; Shevyrin V. A.; Stove C. P. Serotonin 2A Receptor (5-HT(2A)R) Activation by 25H-NBOMe Positional Isomers: In Vitro Functional Evaluation and Molecular Docking. ACS Pharmacol. Transl. Sci. 2021, 4, 479–487. 10.1021/acsptsci.0c00189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poulie C. B. M.; Pottie E.; Simon I. A.; Harpsøe K.; D’Andrea L.; Komarov I. V.; Gloriam D. E.; Jensen A. A.; Stove C. P.; Kristensen J. L. Discovery of β-Arrestin-Biased 25CN-NBOH-Derived 5-HT2A Receptor Agonists. J. Med. Chem. 2022, 65, 12031–12043. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.2c00702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pottie E.; Kupriyanova O. V.; Shevyrin V. A.; Stove C. P. Synthesis and Functional Characterization of 2-(2,5-Dimethoxyphenyl)-N-(2-fluorobenzyl)ethanamine (25H-NBF) Positional Isomers. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2021, 12, 1667–1673. 10.1021/acschemneuro.1c00124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pottie E.; Poulie C. B. M.; Simon I. A.; Harpsøe K.; D’Andrea L.; Komarov I. V.; Gloriam D. E.; Jensen A. A.; Kristensen J. L.; Stove C. P. Structure–Activity Assessment and In-Depth Analysis of Biased Agonism in a Set of Phenylalkylamine 5-HT2A Receptor Agonists. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2023, 14, 2727–2742. 10.1021/acschemneuro.3c00267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis V.; Bonniwell E. M.; Lanham J. K.; Ghaffari A.; Sheshbaradaran H.; Cao A. B.; Calkins M. M.; Bautista-Carro M. A.; Arsenault E.; Telfer A.; Taghavi-Abkuh F. F.; Malcolm N. J.; El Sayegh F.; Abizaid A.; Schmid Y.; Morton K.; Halberstadt A. L.; Aguilar-Valles A.; McCorvy J. D. A non-hallucinogenic LSD analog with therapeutic potential for mood disorders. Cell Rep. 2023, 42, 112203 10.1016/j.celrep.2023.112203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pottie E.; Stove C. P. In vitro assays for the functional characterization of (psychedelic) substances at the serotonin receptor 5-HT(2A) R. J. Neurochem. 2022, 162, 39–59. 10.1111/jnc.15570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wacker D.; Wang S.; McCorvy J. D.; Betz R. M.; Venkatakrishnan A. J.; Levit A.; Lansu K.; Schools Z. L.; Che T.; Nichols D. E.; Shoichet B. K.; Dror R. O.; Roth B. L. Crystal Structure of an LSD-Bound Human Serotonin Receptor. Cell 2017, 168, 377–389.e12. 10.1016/j.cell.2016.12.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitz G. P.; Jain M. K.; Slocum S. T.; Roth B. L. 5-HT2A SNPs Alter the Pharmacological Signaling of Potentially Therapeutic Psychedelics. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2022, 13, 2386–2398. 10.1021/acschemneuro.1c00815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janowsky A.; Eshleman A. J.; Johnson R. A.; Wolfrum K. M.; Hinrichs D. J.; Yang J.; Zabriskie T. M.; Smilkstein M. J.; Riscoe M. K. Mefloquine and psychotomimetics share neurotransmitter receptor and transporter interactions in vitro. Psychopharmacology 2014, 231, 2771–2783. 10.1007/s00213-014-3446-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nichols D. E.; Frescas S.; Marona-Lewicka D.; Kurrasch-Orbaugh D. M. Lysergamides of isomeric 2,4-dimethylazetidines map the binding orientation of the diethylamide moiety in the potent hallucinogenic agent N,N-diethyllysergamide (LSD). J. Med. Chem. 2002, 45, 4344–4349. 10.1021/jm020153s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rickli A.; Moning O. D.; Hoener M. C.; Liechti M. E. Receptor interaction profiles of novel psychoactive tryptamines compared with classic hallucinogens. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2016, 26, 1327–1337. 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2016.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glatfelter G. C.; Chojnacki M. R.; McGriff S. A.; Wang T.; Baumann M. H. Automated Computer Software Assessment of 5-Hydroxytryptamine 2A Receptor-Mediated Head Twitch Responses from Video Recordings of Mice. ACS Pharmacol. Transl. Sci. 2022, 5, 321–330. 10.1021/acsptsci.1c00237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallach J.; Cao A. B.; Calkins M. M.; Heim A. J.; Lanham J. K.; Bonniwell E. M.; Hennessey J. J.; Bock H. A.; Anderson E. I.; Sherwood A. M.; Morris H.; de Klein R.; Klein A. K.; Cuccurazzu B.; Gamrat J.; Fannana T.; Zauhar R.; Halberstadt A. L.; McCorvy J. D. Identification of 5-HT2A receptor signaling pathways associated with psychedelic potential. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 8221. 10.1038/s41467-023-44016-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haberzettl R.; Bert B.; Fink H.; Fox M. A. Animal models of the serotonin syndrome: A systematic review. Behav. Brain Res. 2013, 256, 328–345. 10.1016/j.bbr.2013.08.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanchard R. J.; Griebel G.; Guardiola-Lemaître B.; Brush M. M.; Lee J.; Blanchard D. C. An Ethopharmacological Analysis of Selective Activation of 5-HT1A Receptors: The Mouse 5-HT1A Syndrome. Pharmacol., Biochem. Behav. 1997, 57, 897–908. 10.1016/S0091-3057(96)00472-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pogorelov V. M.; Rodriguiz R. M.; Roth B. L.; Wetsel W. C. The G protein biased serotonin 5-HT2A receptor agonist lisuride exerts anti-depressant drug-like activities in mice. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2023, 10, 1233743 10.3389/fmolb.2023.1233743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fink H.; Morgenstern R. Locomotor effects of lisuride: a consequence of dopaminergic and serotonergic actions. Psychopharmacology 1985, 85, 464–468. 10.1007/BF00429666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carruba M. O.; Ricciardi S.; Chiesara E.; Spano P. F.; Mantegazza P. Tolerance to some behavioural effects of lisuride, a dopamine receptor agonist, and reverse tolerance to others, after repeated administration. Neuropharmacology 1985, 24, 199–206. 10.1016/0028-3908(85)90074-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang K.; Liu X.; Su R. Contrasting effects of DOI and lisuride on impulsive decision-making in delay discounting task. Psychopharmacology 2022, 239, 3551–3565. 10.1007/s00213-022-06229-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiorella D.; Rabin R. A.; Winter J. C. Role of 5-HT2A and 5-HT2C receptors in the stimulus effects of hallucinogenic drugs II: reassessment of LSD false positives. Psychopharmacology 1995, 121, 357–363. 10.1007/BF02246075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adams L. M.; Geyer M. A. Patterns of exploration in rats distinguish lisuride from lysergic acid diethylamide. Pharmacol., Biochem. Behav. 1985, 23, 461–468. 10.1016/0091-3057(85)90022-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darmani N. A.; Mock O. B.; Towns L. C.; Gerdes C. F. The head-twitch response in the least shrew (Cryptotis parva) is a 5-HT2- and not a 5-HT1C-mediated phenomenon. Pharmacol., Biochem. Behav. 1994, 48, 383–396. 10.1016/0091-3057(94)90542-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halberstadt A. L.; Geyer M. A. Effect of Hallucinogens on Unconditioned Behavior. Curr. Top. Behav. Neurosci. 2018, 36, 159–199. 10.1007/7854_2016_466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strassman R. J. Human psychopharmacology of N,N-dimethyltryptamine. Behav. Brain Res. 1995, 73, 121–124. 10.1016/0166-4328(96)00081-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pokorny T.; Preller K. H.; Kraehenmann R.; Vollenweider F. X. Modulatory effect of the 5-HT1A agonist buspirone and the mixed non-hallucinogenic 5-HT1A/2A agonist ergotamine on psilocybin-induced psychedelic experience. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2016, 26, 756–766. 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2016.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casey A. B.; Cui M.; Booth R. G.; Canal C. E. ″Selective″ serotonin 5-HT(2A) receptor antagonists. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2022, 200, 115028 10.1016/j.bcp.2022.115028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandt S. D.; Kavanagh P. V.; Westphal F.; Stratford A.; Elliott S. P.; Hoang K.; Wallach J.; Halberstadt A. L. Return of the lysergamides. Part I: Analytical and behavioural characterization of 1-propionyl-d-lysergic acid diethylamide (1P-LSD). Drug Test. Anal. 2016, 8, 891–902. 10.1002/dta.1884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaster A. M.; Elder H.; Marsh S. A.; de la Fuente Revenga M.; Negus S. S.; González-Maeso J. Effects of the 5-HT(2A) receptor antagonist volinanserin on head-twitch response and intracranial self-stimulation depression induced by different structural classes of psychedelics in rodents. Psychopharmacology 2022, 239, 1665–1677. 10.1007/s00213-022-06092-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker A. M.; Klaiber A.; Holze F.; Istampoulouoglou I.; Duthaler U.; Varghese N.; Eckert A.; Liechti M. E. Ketanserin Reverses the Acute Response to LSD in a Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled, Crossover Study in Healthy Participants. Int. J. Neuropsychopharmacol 2023, 26, 97–106. 10.1093/ijnp/pyac075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preller K. H.; Herdener M.; Pokorny T.; Planzer A.; Kraehenmann R.; Stämpfli P.; Liechti M. E.; Seifritz E.; Vollenweider F. X. The Fabric of Meaning and Subjective Effects in LSD-Induced States Depend on Serotonin 2A Receptor Activation. Curr. Biol. 2017, 27, 451–457. 10.1016/j.cub.2016.12.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vollenweider F. X.; Vollenweider-Scherpenhuyzen M. F.; Bäbler A.; Vogel H.; Hell D. Psilocybin induces schizophrenia-like psychosis in humans via a serotonin-2 agonist action. NeuroReport 1998, 9, 3897–3902. 10.1097/00001756-199812010-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham K. A.; Callahan P. M.; Appel J. B. Discriminative stimulus properties of lisuride revisited: involvement of dopamine D2 receptors. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1987, 241, 147–151. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holohean A. M.; White F. J.; Appel J. B. Dopaminergic and serotonergic mediation of the discriminable effects of ergot alkaloids. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1982, 81, 595–602. 10.1016/0014-2999(82)90349-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimura K.; Akai T.; Nakamura K.; Yamaguchi M.; Nakagawa H.; Oshino N. Dual activation by lisuride of central serotonin 5-HT(1A) and dopamine D(2) receptor sites: drug discrimination and receptor binding studies. Behav. Pharmacol. 1991, 2, 105–112. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White F. J.; Appel J. B. The role of dopamine and serotonin in the discriminative stimulus effects of lisuride. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1982, 221, 421–427. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canal C. E.; Morgan D. Head-twitch response in rodents induced by the hallucinogen 2,5-dimethoxy-4-iodoamphetamine: a comprehensive history, a re-evaluation of mechanisms, and its utility as a model. Drug Test. Anal. 2012, 4, 556–576. 10.1002/dta.1333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canal C. E.Serotonergic Psychedelics: Experimental Approaches for Assessing Mechanisms of Action. In New Psychoactive Substances; Springer, 2018; Vol. 252, pp 227–260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandt S. D.; Kavanagh P. V.; Westphal F.; Elliott S. P.; Wallach J.; Colestock T.; Burrow T. E.; Chapman S. J.; Stratford A.; Nichols D. E.; Halberstadt A. L. Return of the lysergamides. Part II: Analytical and behavioural characterization of N(6) -allyl-6-norlysergic acid diethylamide (AL-LAD) and (2’S,4’S)-lysergic acid 2,4-dimethylazetidide (LSZ). Drug Test. Anal. 2017, 9, 38–50. 10.1002/dta.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shulgin A. T.; Shulgin A.. TiHKAL: The Continuation; Transform Press, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman A. J.; Nichols D. E. Synthesis and LSD-like discriminative stimulus properties in a series of N(6)-alkyl norlysergic acid N,N-diethylamide derivatives. J. Med. Chem. 1985, 28, 1252–1255. 10.1021/jm00147a022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abramson H. A.The Use of LSD in Psychotherapy and Alcoholism; Bobbs-Merrill, 1967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halberstadt A. L.; Klein L. M.; Chatha M.; Valenzuela L. B.; Stratford A.; Wallach J.; Nichols D. E.; Brandt S. D. Pharmacological characterization of the LSD analog N-ethyl-N-cyclopropyl lysergamide (ECPLA). Psychopharmacology 2019, 236, 799–808. 10.1007/s00213-018-5055-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham M. J.; Bock H. A.; Serrano I. C.; Bechand B.; Vidyadhara D. J.; Bonniwell E. M.; Lankri D.; Duggan P.; Nazarova A. L.; Cao A. B.; Calkins M. M.; Khirsariya P.; Hwu C.; Katritch V.; Chandra S. S.; McCorvy J. D.; Sames D. Pharmacological Mechanism of the Non-hallucinogenic 5-HT2A Agonist Ariadne and Analogs. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2023, 14, 119–135. 10.1021/acschemneuro.2c00597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan A. L.; Confair D. N.; Kim K.; Barros-Álvarez X.; Rodriguiz R. M.; Yang Y.; Kweon O. S.; Che T.; McCorvy J. D.; Kamber D. N.; Phelan J. P.; Martins L. C.; Pogorelov V. M.; DiBerto J. F.; Slocum S. T.; Huang X.-P.; Kumar J. M.; Robertson M. J.; Panova O.; Seven A. B.; Wetsel A. Q.; Wetsel W. C.; Irwin J. J.; Skiniotis G.; Shoichet B. K.; Roth B. L.; Ellman J. A. Bespoke library docking for 5-HT2A receptor agonists with antidepressant activity. Nature 2022, 610, 582–591. 10.1038/s41586-022-05258-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong C.; Ly C.; Dunlap L. E.; Vargas M. V.; Sun J.; Hwang I. W.; Azinfar A.; Oh W. C.; Wetsel W. C.; Olson D. E.; Tian L. Psychedelic-inspired drug discovery using an engineered biosensor. Cell 2021, 184, 2779–2792.e18. 10.1016/j.cell.2021.03.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cussac D.; Boutet-Robinet E.; Ailhaud M.-C.; Newman-Tancredi A.; Martel J.-C.; Danty N.; Rauly-Lestienne I. Agonist-directed trafficking of signalling at serotonin 5-HT2A, 5-HT2B and 5-HT2C-VSV receptors mediated Gq/11 activation and calcium mobilisation in CHO cells. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2008, 594, 32–38. 10.1016/j.ejphar.2008.07.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glatfelter G. C.; Partilla J. S.; Baumann M. H. Structure-activity relationships for 5F-MDMB-PICA and its 5F-pentylindole analogs to induce cannabinoid-like effects in mice. Neuropsychopharmacology 2022, 47, 924–932. 10.1038/s41386-021-01227-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pottie E.; Tosh D. K.; Gao Z.-G.; Jacobson K. A.; Stove C. P. Assessment of biased agonism at the A3 adenosine receptor using β-arrestin and miniGαi recruitment assays. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2020, 177, 113934 10.1016/j.bcp.2020.113934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.