ABSTRACT

Objectives

To determine the optimal settings for reconstructing the buccal surfaces of different tooth types using the virtual bracket removal (VBR) technique.

Materials and Methods

Ten postbonded digital dentitions (with their original prebonded dentitions) were enrolled. The VBR protocol was carried out under five settings from three commonly used computer-aided design (CAD) systems: OrthoAnalyzer (O); Meshmixer (M); and curvature (G2), tangent (G1), and flat (G0) from Geomagic Studio. The root mean squares (RMSs) between the reconstructed and prebonded dentitions were calculated for each tooth and compared with the clinically acceptable limit (CAL) of 0.10 mm.

Results

The overall prevalences of RMSs below the CAL were 66.80%, 70.08%, 62.30%, 94.83%, and 56.15% under O, M, G2, G1, and G0, respectively. For the upper dentition, the mean RMSs were significantly lower than the CAL for all tooth types under G1 and upper incisors and canines under M and G2. For the lower dentition, the mean RMSs were significantly lower than the CAL for all tooth types under G1 and lower incisors and canines under M, G2, and G0 (all P < .05). Additionally, the mean RMSs of all teeth under G1 were significantly lower than those under the other settings (all P < .001).

Conclusions

The optimal settings varied among different tooth types. G1 performed best for most tooth types compared to the other four settings.

Keywords: Orthodontics, CAD/CAM, VBR, Retainer

INTRODUCTION

Stability is crucial for orthodontic treatment.1 The timely production and use of retainers can greatly improve the long-term stability of a successful orthodontic treatment.2 For patients with fixed appliances, it is necessary to remove the brackets from the patients’ teeth or the plaster model before retainer production,3 which, however, is usually time-consuming in the clinic or technique sensitive in the laboratory.4

To address these issues, virtual bracket removal (VBR) has been used to obtain digital dentitions before retainer fabrication.5–7 This technique can be used to remove the brackets and tubes and then reconstruct the buccal surfaces of the digital dentition (Figure 1).8 VBR can be performed using various computer-aided design (CAD) systems such as Meshmixer, OrthoAnalyzer, and Geomagic Studio. It has been reported to reduce repeated appointments for patients, provide immediate delivery, improve clinical efficacy, facilitate remote follow-up, and decrease costs, all of which are favorable for digital retainer fabrication.8

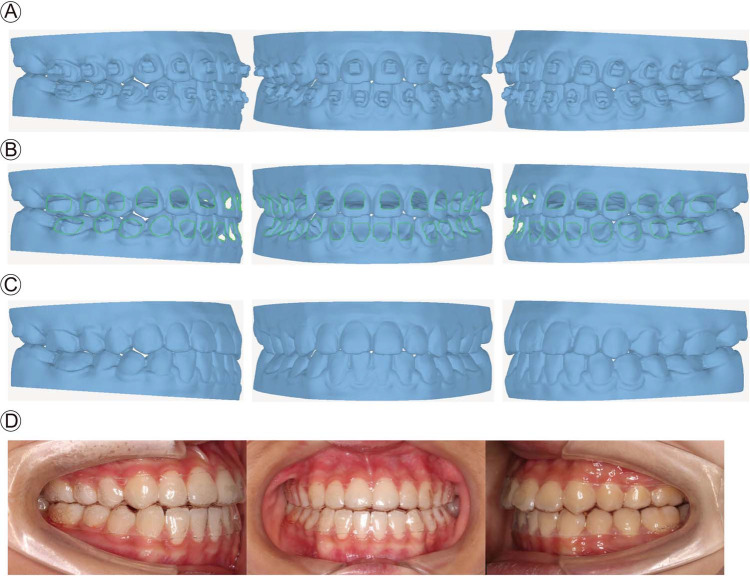

Figure 1.

Process of VBR in clinical practice. (A) An intraoral scan was made for a patient with brackets and tubes before VBR. (B) The brackets/tubes were virtually removed from the digital dentition. (C) The buccal surfaces were reconstructed for 3D printing. (D) The patient wore thermoplastic retainers fabricated from the 3D-printed model.

However, since the buccal surfaces of different tooth types vary, it remains unclear whether one setting in one CAD system can reconstruct all buccal surfaces well.9,10 Therefore, this study aimed to evaluate the accuracy of the buccal surfaces reconstructed under five settings from three commonly used CAD systems and determine the optimal settings for specific tooth types.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Subjects and Criteria

This project was approved by the local institutional ethical committee (WCHSIRB-D-2021-282). Ten pairs of digital prebonded dentitions (upper and lower) were included, each with well-aligned teeth with normal crown morphology.11 The dentitions were digitally bonded with brackets (Clarity adhesive-coated advanced brackets; 3M Unitek, Monrovia, Calif) and tubes (Shinye Orthodontic Products, Hangzhou, China) in OrthoAnalyzer software (O) (3Shape, Copenhagen, Denmark) and were termed postbonded dentitions. Every participant signed an informed consent form.

Virtual Bracket Removal Protocol

In Geomagic Studio 2013 (Raindrop Geomagic Studio 2013; Raindrop Geomagic Inc), the brackets/tubes were virtually removed from the postbonded dentitions. Next, the dentitions were left with holes on the buccal surfaces for reconstruction with smooth surfaces using curvature (G2), tangent (G1), flat (G0) in Geomagic Studio. In O and Meshmixer (M) (version 3.5; Autodesk Inc), the reconstruction was implemented using the postbonded dentitions without holes. In O, a 0.15-mm brush was used for reconstruction as described in a previous study.8 In M, according to preliminary results, bulge degrees of −1, 0, 1, 2, 4, and 5 were applied to the upper incisors, upper molars and lower molars, upper canines and lower incisors, lower canines, lower premolars, and upper premolars, respectively (Supplemental Figure 1; Figure 2).

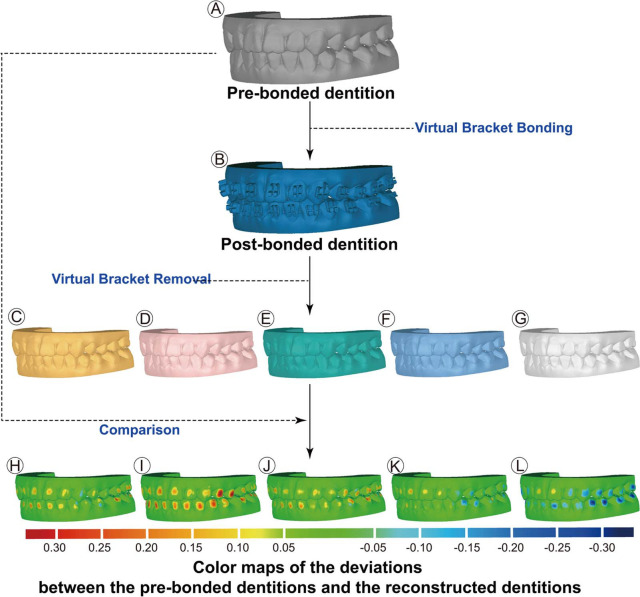

Figure 2.

Study design. (A) Prebonded dentitions. Original dentitions were included. (B) Postbonded dentitions, virtually bonded with brackets/tubes. (C through G) Reconstructed dentitions. Dentitions were generated after buccal surface reconstruction under five different settings (O, M, G2, G1, and G0, respectively). (H through L) Color-coded maps indicating differences between the reconstructed dentitions and the prebonded dentitions under five different settings (O, M, G2, G1, and G0, respectively).

Measurement of the Surface Deviation

The root mean squares (RMSs) between the reconstructed and prebonded dentitions were calculated for each tooth in Geomagic Studio 2013 according to previous studies.8,12,13

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed in SPSS 16.0 (IBM, Armonk, NY). Twenty teeth were randomly selected, and the RMSs were measured by the same investigator again after 2 weeks to evaluate measurement reproducibility. A descriptive analysis was performed for the surface deviations (RMSs) of all tooth types under five settings. An RMS of 0.10 mm was defined as the clinically acceptable limit (CAL) for all teeth.14,15 The proportions of RMSs below the CAL were calculated.

To compare the RMSs with the CAL, a paired t-test was applied for normally distributed data, and a Wilcoxon signed-rank test was applied for nonnormally distributed data. A level of α = 0.05 was set as statistically significant. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was applied for normally distributed data, followed by Tukey’s post hoc analysis to compare the RMSs among groups under different settings. The Kruskal-Wallis H test and the Nemenyi test were conducted on nonnormally distributed data.

With a total sample size of 1180 teeth, the powers of both the Wilcoxon signed-rank test (2-tailed) and the paired t-test were almost 100% for detecting small effect sizes at a significance level of 0.05 (Cohen’s d = 0.5) (G*Power 3.1.9.3; University of Dusseldorf).

RESULTS

In total, the buccal surfaces of 1180 teeth were reconstructed under five settings from the three CAD systems. Measurements were performed based on RMS calculations using Geomagic Studio and were repeated to verify precision.

Comparison of the RMSs with the CAL (0.1 mm)

The overall prevalences of RMSs below the CAL (0.1 mm) were 66.80%, 70.84%, 62.30%, 94.83%, and 56.15% under O, M, G2, G1, and G0, respectively. The prevalence of RMSs below the CAL for each tooth type is illustrated in Table 1.

Table 1.

Prevalence of RMSs Below the Clinically Acceptable Limita

| Tooth Type | O | M | G2 | G1 | G0 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Upper incisor | 90.00% | 90.00%* | 87.50%* | 100.00%* | 72.50%* |

| Upper canine | 94.44%* | 94.44%* | 94.44%* | 93.75%* | 61.11% |

| Upper premolar | 54.17% | 50.00% | 46.88% | 86.67%* | 40.63%* |

| Upper molar | 60.53% | 60.53% | 51.61% | 92.59%* | 38.71%* |

| Lower incisor | 62.50% | 95.00%* | 80.00%* | 100.00%* | 75.00%* |

| Lower canine | 85.00%* | 85.00%* | 100.00%* | 100.00%* | 80.00%* |

| Lower premolar | 79.17% | 37.50% | 41.94% | 100.00%* | 41.94% |

| Lower molar | 32.50%* | 47.50% | 12.50%* | 84.38%* | 40.63%* |

| All tooth types | 66.80% | 70.08%* | 62.30%* | 94.83%* | 56.15% |

The CAL was 0.10 mm for all tooth types. O indicates settings using OrthoAnalyzer; M, settings using Meshmixer; G2, G1, and G0, settings using Geomagic; G2, curvature specifies; G1, tangent specifies; and G0, flat specifies. “*” means that there was a significant difference between the mean RMS of a specific tooth type and the CAL (P < .05).

For upper dentitions, settings with mean RMSs below the CAL varied among different tooth types. The mean RMSs for the upper incisors under M (0.05 mm), G2 (0.05 mm), G1 (0.03 mm), and G0 (0.08 mm); the upper canines under O (0.06 mm), M (0.07 mm), G2 (0.05 mm), and G1 (0.05 mm); and the upper premolars under G1 (0.06 mm) were significantly lower than the CAL. Specifically, for the upper molars, G1 was the only setting showing a mean RMS (0.05 mm) significantly lower than the CAL (P < .05). However, the mean RMSs were significantly higher than the CAL (P < .05) under G2 for upper premolars and molars and G0 for upper molars.

Likewise, for lower teeth, the mean RMSs under M, G2, G1, and G0 for the incisors (0.06, 0.07, 0.04, and 0.06 mm, respectively) and O, M, G2, G1, and G0 for the canines (0.06, 0.07, 0.06, 0.04, and 0.06 mm, respectively) were significantly lower than the CAL (P < .05). For the posterior lower teeth, the mean RMS for premolars under G1 was 0.04 mm, and the mean RMS under G1 for the molars was 0.07 mm, both of which were significantly lower than the CAL (P < .05). The mean RMSs under O, G2, and G0 for the lower molars were significantly higher than the CAL (P < .05).

Comparison of the RMSs Under the Five Settings

The overall mean of the RMSs under G1 was 0.04 mm, significantly lower than those under O (0.09 mm), M (0.07 mm), G2 (0.08 mm), and G0 (0.09 mm) (P < .05). Considering the specific tooth types, for the incisors and molars, the mean RMSs under G1 were significantly lower than those under the other four settings (P < .05), while for the upper and lower premolars, the mean RMSs under G1 were significantly lower than those under G2, M, and O (P < .05) (Table 2).

Table 2.

RMSs of Different Tooth Types Under Different Settingsa

| RMS, Mean ± SD/Median ± Quartile |

P Value (Overall) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tooth Type | O | M | G2 | G1 | G0 | |

| Upper incisor | 0.12 ± 0.06 | 0.05 ± 0.03 | 0.05 ± 0.04# | 0.03 ± 0.02# | 0.08 ± 0.04 | .000* |

| Upper canine | 0.06 ± 0.02 | 0.07 ± 0.03# | 0.05 ± 0.03# | 0.05 ± 0.03 | 0.08 ± 0.05 | .007* |

| Upper premolar | 0.12 ± 0.08 | 0.11 ± 0.07 | 0.10 ± 0.05# | 0.06 ± 0.05# | 0.13 ± 0.15# | .000* |

| Upper molar | 0.10 ± 0.07# | 0.10 ± 0.05 | 0.10 ± 0.07# | 0.05 ± 0.03# | 0.12 ± 0.04 | .000* |

| Lower incisor | 0.09 ± 0.05# | 0.06 ± 0.02 | 0.07 ± 0.04# | 0.04 ± 0.01 | 0.06 ± 0.07# | .000* |

| Lower canine | 0.06 ± 0.03# | 0.07 ± 0.03 | 0.06 ± 0.02 | 0.04 ± 0.02# | 0.06 ± 0.04 | .018* |

| Lower premolar | 0.06 ± 0.05# | 0.11 ± 0.05 | 0.13 ± 0.07 | 0.04 ± 0.04# | 0.11 ± 0.13# | .000* |

| Lower molar | 0.12 ± 0.07# | 0.11 ± 0.05 | 0.15 ± 0.04 | 0.07 ± 0.03 | 0.13 ± 0.07 | .000* |

| Overall | 0.09 ± 0.08# | 0.07 ± 0.06# | 0.08 ± 0.07# | 0.04 ± 0.03# | 0.09 ± 0.09# | .000* |

Means ± standard deviations of the RMSs are given for normally distributed data, and medians ± quartiles are presented for nonnormally distributed data (marked with #). Overall P values generated by one-way ANOVA or the Kruskal-Wallis H test showed statistically significant differences among the RMSs under different settings for the same tooth type. “*” means that there was a significant difference between mean RMSs of specific tooth types among the five settings (P < .05). SD indicates standard deviation; O, settings using OrthoAnalyzer; M, settings using Meshmixer; G2, G1, and G0, settings using Geomagic; G2, curvature specifies; G1, tangent specifies; and G0, flat specifies.

DISCUSSION

This study aimed to find the optimal settings to reconstruct the buccal surfaces of different tooth types for VBR. It was found that the optimal settings varied among different tooth types and CAD systems, and G1 performed the best for most tooth types.

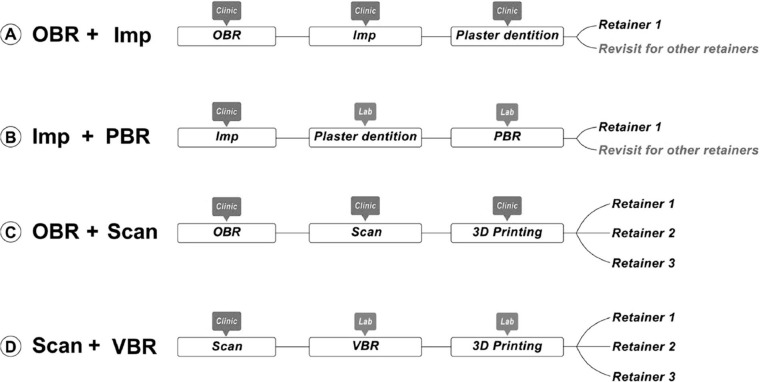

Prompt fabrication and application of retainers are essential for the success and long-term stability of orthodontic treatment.2 Before the fabrication of the thermoplastic retainer for patients with fixed appliances, the brackets are usually removed intraorally in the clinic (intraoral bracket removal [OBR]). Next, an impression (OBR+Imp) or intraoral scan (OBR+Scan) is made to acquire a plaster (Figure 3A) or three-dimensional (3D)-printed (Figure 3C) model, respectively.5,7,8 These approaches for fabricating thermoplastic retainers are summarized in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Four approaches for fabricating thermoplastic retainers. (A) OBR+Imp. (B) Imp+PBR. (C) OBR+Scan. (D) Scan+VBR. For approaches A and B, since the plaster model could crack after fabricating the thermoplastic retainer, the patient would need to return for the fabrication of a replacement appliance. However, for approaches C and D, the 3D-printed dentitions could be reused to fabricate multiple thermoplastic retainers, so there would be no need for the patient to return when requiring additional retainers. Imp indicates impression; PBR, plaster model bracket removal; OBR, intraoral bracket removal; and VBR, virtual bracket removal.

Alternatively, there are two other approaches for fabricating thermoplastic retainers. One is to first take an impression and then manually remove the brackets from the plaster dental model (plaster model bracket removal [PBR]) in the laboratory (Imp+PBR). The other is to first perform a scan intraorally, then virtually remove the brackets (VBR) from the digital dental model using CAD (Scan+VBR), and finally 3D print the resin dental model.3,16,17 These approaches are summarized in Figure 3B and D.

Comparing the four approaches, Scan+VBR and Imp+PBR are less time-consuming than OBR+Imp and OBR+Scan in the clinic.7 Between the two more efficient approaches, Scan+VBR has better repeatability, higher accuracy, and easier operation than Imp+PBR in the process of surface reconstruction.8 Additionally, during retention follow-up, retainers could be obtained more easily from Scan+VBR and OBR+Scan since the 3D-printed model could be used repeatedly for multiple retainers (Figure 3).7,8

The current study involved both the removal of brackets and the reconstruction of tooth surfaces. Considering the processing differences among the three CAD systems, Geomagic was used in this study to remove the brackets/tubes first, leaving a hole for the reconstruction process using the other two CAD systems (O′ and M′) for all of the postbonded dentitions. It was also found that the mean RMSs were lowest under G1 compared to the other 6 settings (O, O′, M, M′, G2, and G0) (Supplemental Table 1). This indicated that tooth surface reconstruction affected the results of VBR among the five settings.

The CAL was used to judge whether the degree of RMS was clinically acceptable. In previous studies, the CAL ranged from 0.16 to 0.30 mm.14,18 In this study, however, a lower CAL (0.10 mm for all teeth) was used. The reason for this was that only the surface reconstruction process was studied, and a lower CAL would leave room for errors from other crucial steps during VBR.

The mean RMSs of most tooth types were found to be lower than the CAL under the settings of O, G2, and G1. Details of the recommended optimal settings for different tooth types are shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Recommended Optimal Settings for Different Tooth Typesa

| Tooth Type | Setting(s) | Tooth Type | Setting(s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Upper incisor | M, G2, G1 | Lower incisor | M, G2, G1 |

| Upper canine | O, M, G2, G1 | Lower canine | O, M, G2, G1 |

| Upper premolar | G1 | Lower premolar | G1 |

| Upper molar | G1 | Lower molar | G1 |

O indicates settings using OrthoAnalyzer; G2, G1, and G0, settings using Geomagic; G2, curvature specifies; G1, tangent specifies; and G0, flat specifies.

Interestingly, compared with those under other settings, the percentage of RMSs below the CAL (94.83%) was the highest under G1. For every tooth type, the mean RMS under G1 was significantly lower than the CAL (P < .05). Additionally, the mean RMS under G1 was significantly lower than those under the other four settings. These findings demonstrated that G1 had the highest precision of reconstruction.

It has been reported that molars had the greatest surface deviation derived from VBR, with RMS values of up to 0.33 mm, while the smallest amount of surface change was seen for the incisors, with RMS values of as low as 0.12 mm.7 Consistently, this trend was also suggested in the present study. For the molars, the mean RMS was higher than those for the other tooth types (P < .05). This might have been caused by interference from the gingival margin and buccal grooves.7,8 For the premolars, the RMS was higher than those for the incisors and canines (all P < .05). This could be explained by the high ratio of the bracket base relative to the premolar buccal surface compared to that of anterior teeth, which increased the surface reconstruction deviation.

The surfaces were reconstructed according to the curvature of the surrounding area under G1. With the morphology of the buccal surface, the curvature of the reconstruction area was able to change automatically without additional adjustments in G1. Settings such as G1 with automatic features are referred to as dynamic self-adaptive settings.

However, for M, multiple bulge values were available to choose from. The reconstructed buccal surface tended to be more convex toward the buccal side as the bulge value increased, which meant that M was not a dynamic self-adaptive setting. In the pre-experiment, the mean RMS first decreased and then increased with the increase of the bulge values for every tooth type. The bulge values providing the minimum RMS values were −1 for the upper incisors, 0 for the upper and lower molars, 1 for the upper canines and lower incisors, 2 for the lower canines, 4 for the lower premolars, and 5 for the upper premolars (Supplemental Figure 1).

In this study, after the selection of bulge, the prevalence of RMSs below the clinically acceptable limit under M was higher than 85% for the anterior tooth types but lower than 65% for the posterior tooth types. However, under G1, the prevalences of RMSs below the clinically acceptable limit were higher than 90% for the anterior tooth types and higher than 80% for the posterior tooth types, and the mean RMSs of G1 for all tooth types except the upper canines were significantly lower than those under M (Table 2; P < .05). The results of this study suggested that dynamic self-adaptive settings performed better.

The time for the whole VBR process was evaluated on five pairs of dentitions using the three CAD systems. The results showed that VBR using Geomagic Studio took less time (11.63 ± 0.47 min) than those using OrthoAnalyzer (14.52 ± 0.42 min) and Meshmixer (15.44 ± 0.38 min). One possible reason for this was that each area on the bracket needed to be selected manually in Meshmixer and OrthoAnalyzer. The other possible reason was that once the area was chosen inaccurately, the operation needed to be completely redone in OrthoAnalyzer. In contrast, only the surrounding lines are required for selection in Geomagic Studio, and inverted selection is allowed. However, Geomagic Studio was more expensive ($19,950) than OrthoAnalyzer ($3,222/year) and Meshmixer ($0).

In the future, the accuracy of 3D-printed resin models for fabricating retainers and the clinical effect and management of retainers made via VBR should be further studied under optimal settings. Additionally, to reduce cost and improve efficiency, it is necessary to build a new CAD system tailored for VBR and apply optimal settings to reconstruct buccal surfaces.

CONCLUSIONS

The optimal settings for reconstruction varied among different tooth types.

G1 performed best for most tooth types compared to the other four settings.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (62206190); the Natural Science Foundation of Sichuan Province (22NSFSC2984); the Interdisciplinary Innovation Project and Clinical Research Project of West China Hospital of Stomatology, Sichuan University (RD-03-202108, LCYJ-2022-YY-3); and the National College Student Innovation and Entrepreneurship Training Program (C2023124860).

SUPPLEMENTAL DATA

The Appendix with supplemental data is available online.

REFERENCES

- 1. Lin F, Sun H, Yao L, Chen Q, Ni Z. Orthodontic treatment of severe anterior open bite and alveolar bone defect complicated by an ankylosed maxillary central incisor: a case report. Head Face Med. 2014;10((1)):1–8. doi: 10.1186/1746-160X-10-47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kravitz ND, Groth C, Jones PE, Graham JW, Redmond WR. Intraoral digital scanners. J Clin Orthod. 2014;48((6)):337–347. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Mohammed S, Hajeer MY, Muessing DS. Acceptability comparison between Hawley retainers and vacuum-formed retainers in orthodontic adult patients: a single-center, randomized controlled trial. Eur J Orthod. 2017;39((4)):453–461. doi: 10.1093/ejo/cjx024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Jheon AH, Oberoi S, Solem RC, Kapila S. Moving towards precision orthodontics: an evolving paradigm shift in the planning and delivery of customized orthodontic therapy. Orthod Craniofac Res. 2017;20:106–113. doi: 10.1111/ocr.12171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Vasudavan S, Sullivan SR, Sonis AL. Comparison of intraoral 3D scanning and conventional impressions for fabrication of orthodontic retainers. J Clin Orthod. 2010;44((8)):495–497. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Groth C, Kravitz ND, Shirck JM. Incorporating three-dimensional printing in orthodontics. J Clin Orthod. 2018;52((1)):28–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Marsh K, Weissheimer A, Yin K, Chamberlain-Umanoff A, Tong H, Sameshima GT. Three-dimensional assessment of virtual bracket removal for orthodontic retainers: a prospective clinical study. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2021;160((2)):302–311. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2020.09.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Chamberlain-Umanoff A. Assessment of 3D Surface Changes Following Virtual Bracket Removal Los Angeles, Calif: University of Southern California; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Bai D, Xiao L, Chen Y. A study on central zone contour of tooth-crown vesicular surface among young people with normal occlusion. J Biomed Eng. 2002;19((2)):287–290. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Andrews LF. The straight-wire appliance. Br J Orthod. 1979;6((3)):125–143. doi: 10.1179/bjo.6.3.125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Andrews LF. The six keys to normal occlusion. Am J Orthod. 1972;62((3)):296–309. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9416(72)90268-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lin H-H, Chiang W-C, Lo L-J, Wang C-H. A new method for the integration of digital dental models and cone-beam computed tomography images Annu Int Conf IEEE Eng Med Biol Soc 2013: 2328 2331 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Gkantidis N, Schauseil M, Pazera P, Zorkun B, Katsaros C, Ludwig B. Evaluation of 3-dimensional superimposition techniques on various skeletal structures of the head using surface models. PLoS One. 2015;10((2)):e0118810. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0118810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hazeveld A, Slater JJH, Ren Y. Accuracy and reproducibility of dental replica models reconstructed by different rapid prototyping techniques. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2014;145((1)):108–115. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2013.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Michelinakis G, Apostolakis D, Tsagarakis A, Kourakis G, Pavlakis E. A comparison of accuracy of 3 intraoral scanners: a single-blinded in vitro study. J Prosthet Dent. 2020;124((5)):581–588. doi: 10.1016/j.prosdent.2019.10.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Diner M, Aslan B. Effects of thermoplastic retainers on occlusal contacts. Eur J Orthod. 2009;32((1)):6–10. doi: 10.1093/ejo/cjp062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Krämer A, Sjöström M, Hallman M, Feldmann I. Vacuum-formed retainer versus bonded retainer for dental stabilization in the mandible—a randomized controlled trial. Part I: retentive capacity 6 and 18 months after orthodontic treatment. Eur J Orthod. 2019;42((5)):551–558. doi: 10.1093/ejo/cjz072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kim S-Y, Shin Y-S, Jung H-D, Hwang C-J, Baik H-S, Cha J-Y. Precision and trueness of dental models manufactured with different 3-dimensional printing techniques. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2018;153((1)):144–153. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2017.05.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.