Abstract

Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) has become an increasingly popular tool to modulate neural excitability and induce neural plasticity in clinical and preclinical models; however, the physiological mechanisms in which it exerts these effects remain largely unknown. To date, studies have primarily focused on characterizing rTMS-induced changes occurring at the synapse, with little attention given to changes in intrinsic membrane properties. However, accumulating evidence suggests that rTMS may induce its effects, in part, via intrinsic plasticity mechanisms, suggesting a new and potentially complementary understanding of how rTMS alters neural excitability and neural plasticity. In this review, we provide an overview of several intrinsic plasticity mechanisms before reviewing the evidence for rTMS-induced intrinsic plasticity. In addition, we discuss a select number of neurological conditions where rTMS-induced intrinsic plasticity has therapeutic potential before speculating on the temporal relationship between rTMS-induced intrinsic and synaptic plasticity.

Keywords: intrinsic plasticity, neurophysiology, brain stimulation, repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation, axonal plasticity, neural plasticity, neuronal excitability, axon initial segment

Introduction

Non-invasive brain stimulation, particularly repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS), has become extremely popular in basic and clinical neuroscience as a tool to drive neural plasticity. While the effects of rTMS on the brain are not yet fully understood, a common outcome (albeit with substantial variability) is a change to the “excitability” of neural networks, particularly in the motor cortex and the corticospinal tract. At the single-cell level, neural excitability is regulated by synaptic and intrinsic mechanisms. Whereas synaptic mechanisms directly affect the extent of neural input, such as the amount of neurotransmitter release or connectivity of neuronal networks, intrinsic membrane properties affect the conversion of neural input to neural output (i.e., action potentials [APs]). However, despite the importance of synaptic and intrinsic mechanisms in regulating neural excitability, rTMS-induced plasticity to date has been attributed to changes at the synapse (synaptic plasticity) with little attention given to changes in intrinsic membrane properties (intrinsic plasticity).

There are several mechanisms of intrinsic plasticity, but a common mechanistic feature is a change to the density, distribution, or kinetics of voltage-gated and/or calcium-dependent ion channels in the plasma membrane (Sehgal and others 2013). Depending on the neuronal compartment (i.e., somatodendritic) and class of ion channel (sodium, potassium, etc.) that is modulated, intrinsic plasticity ultimately alters neuronal excitability. These processes are independent of changes at the synapse as they regulate the integration of synaptic input, initiation of APs, and maximum frequency of APs. Similar to synaptic plasticity, intrinsic plasticity plays a critical role in shaping adaptive changes in the brain, including the processes of learning and memory (for review, see Sehgal and others 2013). In this review, we provide a brief overview of the different intrinsic plasticity mechanisms before discussing the evidence of rTMS-induced intrinsic plasticity. For synaptic and glial mechanisms of rTMS-induced neural plasticity, see the reviews by Tang and others (2017) and Cullen and Young (2016), respectively. In addition, we discuss a select number of neurological conditions where rTMS-induced intrinsic plasticity has therapeutic potential, and we speculate on the temporal relationship of rTMS-induced intrinsic and synaptic plasticity.

Box 1. Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation.

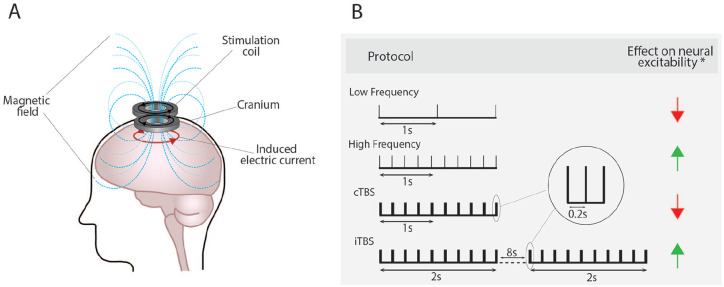

Transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) is a form of non-invasive brain stimulation based on the principles of electromagnetic induction. A stimulation coil placed over the scalp is used to deliver brief pulses of magnetic fields, which induce an electrical current in the underlying brain (Fig. 1A) (Barker and others 1985). The intensity of the induced electrical current is proportional to the rate of change in the magnetic field. When delivered at “high intensities,” the electrical currents induced by TMS can non-invasively activate neural networks (Funke 2018). TMS can also be used to induce neuromodulatory effects by applying several hundred or thousands of TMS pulses, known as repetitive TMS (rTMS), which has become an increasingly popular tool to modulate neural excitability and induce neural plasticity in human and animal models (Funke 2018). Stimulation parameters, such as the timing/frequency of the TMS pulses and stimulation intensity, can be altered to exert specific effects on neural excitability and plasticity, albeit with substantial variability (Goetz and others 2016). In particular, the frequency of the rTMS pulses is considered crucial in determining the direction of rTMS-induced plasticity outcomes, with low-frequency rTMS (≤1 Hz) typically reducing neural excitability and with high-frequency rTMS (≥5 Hz) typically increasing neural excitability (Fig. 1B) (Wassermann and Zimmermann 2012). Additionally, patterned protocols of rTMS such as theta burst stimulation, which mimic endogenous neural theta activity, are also known to display frequency-specific effects and can decrease or increase neural excitability when delivered in a continuous or intermittent pattern, respectively (Fig. 1B) (Huang and others 2005).

Figure 1.

Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation induces its effects via electromagnetic induction (A) and in a frequency-dependent manner (B). *The expected effect on neural excitability with substantial variability observed. cTBS = continuous theta burst stimulation; iTBS = intermittent theta burst stimulation.

Intrinsic Plasticity Mechanisms

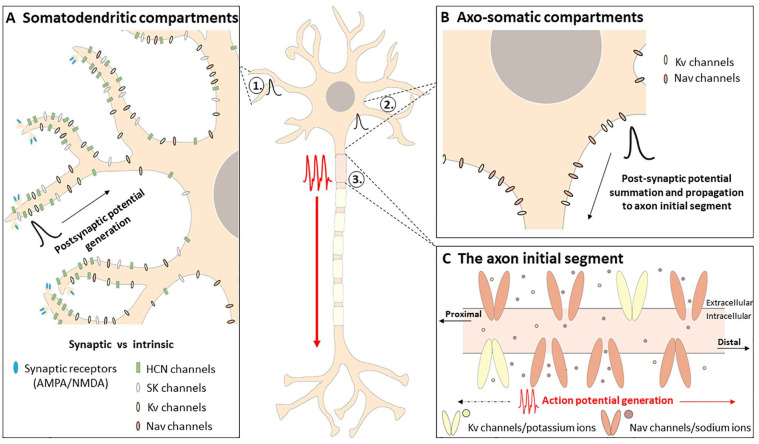

Intrinsic plasticity occurs at neuronal compartments outside the synapse, including the cell body or soma, dendrites, and axonal compartments, and on local scales (i.e., inputs arriving at the distal dendrites) or global scales (i.e., somatodendritic compartments that integrate multiple inputs) (Fig. 2). Functionally, intrinsic plasticity can modulate neuronal excitability by 1) amplifying or attenuating incoming synaptic inputs arriving predominantly at the dendrites (i.e., synaptic potentials), 2) changing the resting membrane potential of the neuron, and/or 3) changing the threshold required to induce AP firing, known as AP threshold (Debanne and others 2019). The following section provides a brief description of how each of these intrinsic mechanisms alters the input-output function of a neuron.

Figure 2.

Intrinsic factors influencing neuronal excitability. Arriving synaptic signals (i.e., via presynaptic neurotransmitter release) activate synaptic receptors and generate a postsynaptic potential (A). Voltage-gated and calcium-dependent ion channels (i.e., intrinsic factors) located in somatodendritic (A) and axosomatic (B) compartments influence the propagation of postsynaptic potentials to the axon initial segment (C) where, if the threshold is met, an action potential will be generated and propagated along the axon. In addition, action potentials can be propagated back toward somatodendritic compartments to influence dendritic excitability. Voltage-gated and calcium-dependent ion channels in somatodendritic (A) and axosomatic (B) compartments also contribute to the regulation of the resting membrane potential, which determines the amount of depolarizing current needed to reach action potential threshold. Note: Voltage-gated calcium channels are also present at the axon initial segment and somatodendritic and axosomatic regions but are not discussed in this review. HCN = hyperpolarization-activated cyclic-nucleotide gated; Kv = voltage-gated potassium; Nav = voltage-gated sodium; NMDA = N-methyl-d-aspartate; SK = small-conductance calcium-activated potassium.

Amplification or Attenuation of Postsynaptic Potentials at the Dendrites

Intrinsic excitability, in its most basic form, is the likelihood that a neuron will generate an output (an AP) in response to a given input. These inputs, which can be in the magnitude of thousands (Salinas and Sejnowski 2000), can arrive at somatic, dendritic, and axonal regions and will either depolarize or hyperpolarize the neuron in the form of excitatory or inhibitory postsynaptic potentials (EPSPs and IPSPs), respectively. For the efficient conversion of synaptic potentials to APs, postsynaptic potentials must propagate from their site of generation to the axon initial segment (AIS), where they are summated to influence AP initiation (Stuart and others 1997). However, through cable theory, it is known that electrical current decays with distance (Rall 1969). Therefore, synaptic potentials that are generated farther away from the soma (e.g., at distal dendrites) are more likely to undergo filtering and decay before reaching the AIS. As a result, excitatory potentials generated at distal locations relative to the AIS will be less effective in depolarizing the neuron to the threshold required for AP initiation as compared with excitatory potentials generated at more proximal locations. Fortunately, this can be modulated by active electrical properties, such as voltage-gated ion channels, that enhance or attenuate postsynaptic potential amplitudes and increase or reduce their propagation to the AIS, respectively.

Within the dendrites, there are several voltage-gated ion channels that influence the excitability of the dendrites and actively shape postsynaptic potential waveforms. This includes the hyperpolarization-activated cyclic-nucleotide gated (HCN) channel and its associated hyperpolarization-activated cation current (Ih). In pyramidal neurons, HCN channels are nonuniformly distributed throughout the dendrites, with high densities anchored at the distal dendrites relative to proximal dendritic regions (Fig. 2A) (Magee 1999; Williams and Stuart 2000). HCN channels become activated at negative (i.e., hyperpolarized) potentials (approximately −50 mV) and are permeable to sodium and potassium ions, in turn providing an inward current that slowly depolarizes the cell membrane and contributes to maintaining the resting membrane potential (Wahl-Schott and Biel 2009). Despite this depolarizing potential, it is the deactivation of HCN channels and Ih currents that act to amplify EPSP propagation from distal regions to the soma, specifically those generated at distal dendrites. This is due to a change in the membrane resistance, which reflects the number of open ion channels at the membrane. A reduction in the number of open channels results in an increase in membrane resistance, which essentially decreases the amount of current that “leaks” out of the membrane and instead facilitates or “shunts” current along the dendrites. Thus, the resulting increase in membrane resistance following HCN channel deactivation acts to prevent the decay of EPSP amplitudes as they propagate to the AIS for integration, increasing the likelihood that the depolarizing current threshold to generate an AP will be reached (Magee 1999; Stuart and Hausser 2001; Williams and Stuart 2000). Conversely, activation of HCN channels at hyperpolarized potentials attenuate EPSP amplitudes by decreasing the resistance of the membrane and increasing the likelihood of EPSP decay (Kase and Imoto 2012). Activated HCN channels are also known to actively suppress IPSPs, as the hyperpolarizing current of inhibitory inputs recruits the opening of more HCN channels, thereby increasing the amount of HCN depolarizing current (Williams and Stuart 2003). Through its role in regulating EPSP attenuation and neuronal excitability, it is no surprise that HCN channels play a role in neural plasticity. For example, chronic decreases in the network activity of CA1 pyramidal neurons results in the downregulation of HCN channels and, as a consequence, increases neural excitability due to greater membrane resistance and EPSP summation (Fan and others 2005). This activity-dependent regulation of HCN expression is bidirectional, as increased hippocampal network activity upregulates HCN expression and Ih current, leading to a decrease in membrane resistance and neural excitability (Fan and others 2005).

In addition to HCN channels, small-conductance calcium-activated potassium (SK) channels and voltage-gated sodium (Nav) channels contribute to the shape of EPSP waveforms. SK channels, which are activated by increases in the intracellular concentration of calcium, provide an efflux of potassium ions that hyperpolarizes the cell (Sun and others 2020), in turn attenuating synaptic potentials by opposing the depolarizing currents induced by EPSPs (Faber and others 2005). On the other hand, activation of axonal and somatic Nav channels amplifies EPSPs arriving at the soma by providing an inward positive current that further depolarizes the cell (Fig. 2B) (Stuart and Sakmann 1995). Thus, intrinsic plasticity can influence the integration and propagation of postsynaptic potentials, which then affects the likelihood that synaptic input will lead to the generation of an AP and subsequent neuronal output.

Alterations in Resting Membrane Potential

Plasticity of the resting membrane potential is another mechanism for regulating neuronal input-output. At “rest,” the membrane potential of a neuron is maintained at a relatively stable voltage due to the activity of various ion pumps and channels, such as the sodium-potassium pump and HCN channels (Lamas and others 2002; Wahl-Schott and Biel 2009). Deviations from this resting membrane potential that depolarize or hyperpolarize a neuron will drive a neuron closer to or further away from the threshold required to generate an AP, respectively. That is, the difference between the resting membrane potential and AP threshold will ultimately determine how much depolarizing current is needed to induce neuronal firing, making intrinsic plasticity of the resting membrane potential another mechanism to alter neuronal excitability and neuronal output.

Although HCN channel activation attenuates EPSPs and reduces intrinsic excitability, this effect can be offset by the role that HCN channels have in regulating the resting membrane potential. In dentate granule cells of the hippocampus, repetitive activation leads to a lasting (>10 min) depolarization of the resting membrane potential, in turn increasing neuronal excitability by reducing the current needed to reach AP threshold and induce AP firing (Mellor and others 2002). This effect can be abolished via application of ZD7288, a specific HCN channel blocker, which induces hyperpolarization of the membrane potential (Mellor and others 2002). Thus, HCN regulation of the resting membrane potential is one intrinsic mechanism to alter neuronal excitability and subsequent neuronal responsiveness to inputs. Independent of HCN channels, intrinsic plasticity to the resting membrane potential can occur due to the modulation of the pumps that regulate the resting membrane potential. In the dentate gyrus, high-frequency electrical stimulation of the perforant pathway induces a long-lasting depolarization to the resting membrane potential of interneurons (Ross and Soltesz 2001). As a result, interneurons with a depolarized resting membrane potential generate APs to synaptic inputs that were previously subthreshold (i.e., below the threshold required for AP generation). The cellular mechanism underlying the long-lasting depolarization is due to a decrease in the activity of the Na+/K+-ATPase pump, which provides a hyperpolarizing current (Ross and Soltesz 2000), as inhibiting the pump prevents the change to the resting membrane potential.

Functionally, plasticity of the resting membrane potential has been shown to occur following skilled motor learning in rodents (Kida and others 2016). Specifically, 1 d of skilled motor training significantly hyperpolarized the resting membrane potential and depolarized AP threshold in layer 2/3 pyramidal neurons of the primary motor cortex, leading to a decrease in neuronal excitability. On the other hand, 2 d of skilled motor training did not alter the AP threshold but did significantly depolarize the resting membrane potential, indicating an increase in neuronal excitability. To rule out that these intrinsic changes were not the result of synaptic mechanisms (i.e., mediated via α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic [AMPA] or N-methyl-d-aspartate NMDA receptors), the AMPA receptor antagonist CNQX and the NMDA receptor antagonist APV were delivered prior to motor training. Neither drug had any effect on the resting membrane potential, suggesting a direct intrinsic plasticity mechanism to regulate excitability during motor learning (Kida and others 2016). Although the specific ion channels involved in this functional change are unknown, this study does highlight a role for intrinsic plasticity of the resting membrane potential in motor learning that is independent of synaptic plasticity.

Alterations in AP Threshold

The final intrinsic plasticity mechanism in which the input-output function of a neuron can be regulated is via changes to the threshold required for the generation of APs, often referred to as AP threshold. Modifications in AP threshold typically occur via Nav and voltage-gated potassium (Kv) channels that underlie the depolarization and repolarization phase of the AP, respectively (Hodgkin and Huxley 1952; Rowan and others 2014). For example, increasing the density of either Nav or Kv channels will lead to greater ion current flow upon activation of these channels. In the case of Nav, greater sodium ion influx leads to a depolarizing current and drives the membrane potential closer to the AP threshold and increases the likelihood of AP firing. Conversely, increased potassium ion efflux leads to a greater hyperpolarizing current and drives the membrane potential further away from AP threshold, consequently reducing the likelihood of AP firing. Examples of this can be seen at the AIS, which contains high densities of Nav and Kv channels (Fig. 2C). In particular, the density of Nav channels is estimated to range between 5- and 50-fold higher at the AIS than that observed at the dendrites or in the distal axon (Kole and others 2008), which is thought to contribute to the AIS having the lowest threshold for AP initiation. The AIS is known to undergo periods of structural and functional plasticity in response to altered neural activity levels. Structurally, this includes changes in AIS length, location of the AIS relative to the soma, and the density and distribution of ion channels anchored at the AIS. The functional outcome of structural AIS plasticity is a change to the intrinsic excitability and firing properties which influence neuronal output (Chand and others 2015; Evans and others 2015; Galliano and others 2021; Grubb and Burrone 2010; Jamann and others 2018; Jamann and others 2021; Kuba and others 2010). For example, in the avian auditory system, deprivation of presynaptic input following cochlear removal causes a distal increase in AIS length and markedly larger clusters of Nav1.6 channels (Kuba and others 2010), which are low threshold–activating Nav channels thought to support AP initiation and propagation along the axon (Hu and others 2009). These structural changes led to an increase in membrane excitability and spontaneous neuronal firing, reflecting the relationship between Nav density and the likelihood that AP threshold will be met (Kuba and others 2010). Similar to increased sodium currents, elongation of the AIS following auditory deprivation has been shown to cause a redistribution of Kv channels, specifically Kv1.1 and Kv7.2. Under normal physiologic conditions, AP generation is regulated predominantly by somatic and AIS Kv1 channels, which act to suppress AP initiation (Yamada and others 2015). However, following sensory deprivation, Kv1.1 channels are downregulated, and a reduced Kv1.1 current causes an increase in input resistance and a reduction in AP threshold, in turn increasing neuronal excitability. Coinciding with Kv1.1 changes is an increase in Kv7.2 channel expression at the AIS. Due to the slow activation properties of Kv7 channels, an increased expression, accompanied by the decrease in Kv1.1 expression, is thought to reduce the amount of current leaking out of the membrane at voltages around the AP threshold. This essentially lowers AP threshold and, as a consequence, results in an increase in neuronal excitability (Yamada and others 2015). Similarly, in juvenile hippocampal interneurons, high-frequency electrical stimulation induces a downregulation of Kv1 channels, which, as expected, results in a more hyperpolarized AP threshold (Campanac and others 2013). This change in Kv1 channel activity may be localized to the cell body and axon, as similar changes in neuronal firing patterns can be reproduced in computational models that block Kv1 channels at these neuronal compartments (Campanac and others 2013).

The AIS is known to undergo other forms of structural plasticity that modulate neuronal excitability, including changes in its location along the axon relative to the soma (Grubb and Burrone 2010). For example, neurons with a distally located AIS are thought to be less excitable, as synaptic inputs, which attenuate with distance, must travel farther to depolarize the AIS, in turn reducing the likelihood of AP initiation (Grubb and Burrone 2010). This was seen in mouse hippocampal cultures following 48 h of chronic depolarization, which caused a distal shift in AIS location by ~11 µm, evident by the distal shift in various AIS-specific components, such as Nav channels and the scaffolding proteins ankyrin G and βIV-spectrin (Grubb and Burrone 2010). Direct neuronal recordings (i.e., patch-clamp electrophysiologic recordings) to quantify the functional consequences of AIS distal relocation showed a significant depolarization of AP threshold, reflecting a decrease in overall neuronal excitability and highlighting the link between AIS location relative to the soma and neuronal excitability (Grubb and Burrone 2010). However, the relationship between AIS location relative to the soma and neuronal excitability appears to be nonlinear, with experimental and theoretical studies demonstrating enhanced excitability when the AIS is positioned distally along the axon (Hamada and others 2016; Kole and Brette 2018). This disparity in results may reflect two variables: 1) the influence of neuronal morphology and AIS geometry on excitability and 2) the parameters used to measure excitability. In the former, modeling studies propose that a distal shift in AIS position increases the electrical isolation of the AIS from the soma, which should lead to an increase in excitability. To some extent, this was verified experimentally, whereby “pinching” the proximal axon to model electrical isolation of the AIS (i.e., a distal relocation) led to a decrease in AP threshold in 50% of the layer 5 pyramidal neurons that were recorded from (Fékété and others 2021). Yet, modeling studies have demonstrated that enhanced excitability following a distal relocation of the AIS holds true only in neurons with large axonal (Goethals and Brette 2020) or somatodendritic (Gulledge and Bravo 2016) compartments. Conversely, neurons with small axonal (Goethals and Brette 2020) or somatodendritic (Gulledge and Bravo 2016) compartments are more excitable when the AIS is located proximal to the soma, indicating neuronal morphology as a contributing factor in AIS position and neuronal excitability. In the context of the parameters used to measure excitability, there is debate surrounding how changes in excitability resulting from AIS plasticity should best be measured, with a theoretical study by Goethals and Brette (2020) suggesting somatic voltage threshold as a measurement of AIS-induced excitability changes, as opposed to changes in axonal threshold and/or rheobase. Nonetheless, changes in AIS location relative to the soma, with the other forms of AIS structural plasticity discussed, are yet another mechanism in which intrinsic plasticity of the AP threshold can modulate neuronal excitability.

As detailed earlier, intrinsic plasticity mechanisms can have profound consequences on how neuronal input is converted into an output, making intrinsic plasticity a promising target for interventions aiming to modulate neuronal excitability in health and disease. An example of such an intervention may be neuromodulatory tools such as rTMS. While most mechanistic rTMS studies have focused on synaptic mechanisms, there is evidence showing that rTMS modulates intrinsic excitability (Hoppenrath and others 2016; Tang and others 2016). This has led us to suggest that rTMS-induced plasticity is, in part, due to intrinsic plasticity mechanisms. Encouragingly, rTMS-induced intrinsic plasticity occurs in response to stimulation intensity—both subthreshold, which does not directly trigger AP firing, and suprathreshold, which does directly trigger AP firing. The following section discusses in detail two studies that provide direct evidence of rTMS-induced intrinsic plasticity.

Evidence of rTMS-Induced Intrinsic Plasticity

Using subthreshold rTMS (600 pulses of intermittent θ burst stimulation [iTBS]), Tang and others (2016) delivered stimulation to brain slices obtained from the sensorimotor cortex of mice. Through electrophysiologic patch-clamp recordings, they observed an increase in the excitability of layer 5 pyramidal neurons following stimulation. While subthreshold iTBS did not alter membrane properties such as resting membrane potential or input resistance, it did increase the firing frequency of evoked APs in response to small depolarizing current injections and induced a more hyperpolarized AP threshold (i.e., an AP threshold “closer” to the resting membrane potential). Moreover, these changes in AP threshold occurred both immediately and 20 min post-stimulation but not at 10 min post-stimulation. The hyperpolarized AP threshold was thought to result from changes in the voltage gating properties of Nav channels at the AIS, rather than changes to the density of Nav channels, which at the time was thought to require longer to develop post-stimulation. However, it is now known that changes in Nav densities can occur in as little as 5 min at neuronal regions such as the AIS (Benned-Jensen and others 2016). Thus, it may be that the immediate effects on AP threshold following subthreshold iTBS are the result of changes in Nav gating properties (i.e., conformation changes that trigger the activation and/or inactivation of Nav channels) while the effects observed at 20 min poststimulation arise from an increase in Nav density at the AIS. Interestingly, unlike the changes in AP threshold, enhanced AP firing frequency was present at all time points measured post-stimulation (0, 10, and 20 min). Therefore, given that the change to AP firing frequency was present throughout the 20 min poststimulation, it is possible that this form of plasticity occurs independently from the change in AP threshold. This was thought to result from changes in the kinetics of Kv channels, which are known to be involved in the regulation of repetitive firing in layer 5 pyramidal neurons, although further investigation with pharmacologic experiments is required to confirm Nav and Kv modulation. Additionally, it is important to consider that the mice used by Tang and others were relatively young (12–15 d old) and were therefore potentially in a hyperplastic state, making them more susceptible to plastic changes as compared with neurons in the adult brain. Nevertheless, the changes to AP threshold and firing frequency provide a proof of concept that subthreshold rTMS can induce plasticity beyond the synapse and recruit intrinsic plasticity mechanisms. From the results of Tang and others, we speculate that subthreshold iTBS induces intrinsic plasticity at the AIS. We base our speculation on the fact that Nav and Kv channels, which regulate AP threshold and firing frequencies, are localized at the AIS. Moreover, the ion channels at the AIS are known to undergo activity-dependent modulation over rapid and longer-lasting time scales. Additionally, previous studies using optogenetic stimulation (light stimulation of genetically engineered proteins) have shown that only “physiologically relevant” patterns of stimulation (i.e., ones that mimic exogenous brain activity such as iTBS, as opposed to steady, 1- to 20-Hz stimulation) induce AIS plasticity (Grubb and Burrone 2010). Thus, follow-up studies are required to confirm that subthreshold iTBS preferentially targets the AIS. Furthermore, it would be interesting to determine which frequencies/pulse patterns of subthreshold rTMS induce intrinsic plasticity and if they target specific neuronal domains.

In the context of suprathreshold stimulation, rTMS has been shown to enhance the excitability of layer 2/3 fast-spiking interneurons of the rat somatosensory cortex. In a study by Hoppenrath and others (2016), three blocks (1800 pulses total) of suprathreshold iTBS were delivered to awake rats of different ages (26–62 d), and the changes in neuronal excitability were recorded 2 h poststimulation. In vitro patch clamp recordings revealed increases in the evoked spike firing frequency for rats aged 29 to 38 d, with the greatest effect seen between 32- and 35-d-old rats, along with a more depolarized resting membrane potential (approximately +14 mV for rats aged 32–35 d and +10 mV for rats aged 36–38 d). Changes in intrinsic plasticity were age-dependent and did not occur in rodents <29 d postnatal or mice >36 d postnatal. These results demonstrate the importance of age in determining the extent to which iTBS can induce intrinsic plasticity. For this reason, it will be crucial for future studies to characterize rTMS-induced effects in the adult and aged brain to determine its capacity for driving plasticity in a more mature/stable state, as opposed to the young and hyperplastic brain states investigated to date. In addition to the changes in firing frequency and resting membrane potential, Hoppenrath and others reported an increase in the frequency of spontaneous excitatory postsynaptic currents, indicating a concomitant increase in the excitability of presynaptic excitatory cells. Although the authors could not exclude that enhanced fast-spiking interneuron excitability was influenced by the increase in EPSC frequency, it did not appear that the spontaneous excitatory input rate observed was alone sufficient to induce the depolarized resting membrane potential observed post-iTBS, suggesting intrinsic mechanisms at play as opposed to synaptic changes. While an iTBS-induced increase in excitatory and inhibitory neuronal activity seems counterproductive and energetically costly, it may reflect a homeostatic mechanism to gate the excitatory changes in both neuronal subtypes. In this way, iTBS-induced increases in cortical excitability can be gated by iTBS-induced increases in inhibitory activity, which, as a result, will allow neural network activity to be maintained at an equilibrium, as opposed to a hypo- or hyperexcitable state. This is supported by similar studies that reported increases in inhibitory excitability following rTMS lasting from up to 40 min post-stimulation (Hoppenrath and Funke 2013) to 7 d post-stimulation (Trippe and others 2009), which is thought to reflect a protective or compensatory mechanism to offset the initial increase in excitatory network activity (Hoppenrath and Funke 2013; Trippe and others 2009). However, whether rTMS does preferentially affect one neuronal type more than the other is still unknown.

By combining the studies using iTBS (Table 1), there is a foundation of evidence to suggest that even a single block of rTMS can induce lasting changes to the intrinsic excitability of excitatory and inhibitory neurons, with the changes occurring quite rapidly (e.g., immediately post-stimulation). Thus, our interpretation of how rTMS affects the brain, in a basic and a clinical neuroscience context, should not be limited to changes at the synapse but should also include intrinsic plasticity mechanisms. It is our hope that by further exploring rTMS-induced intrinsic plasticity, it may be possible to expand the clinical use of rTMS to treat neurological disorders underpinned by maladaptive intrinsic plasticity.

Table 1.

rTMS-Induced Intrinsic Plasticity.

| Study | Cell Type | rTMS protocol | +0 min | +10 min | +20 min | +2 h |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tang and others (2016) | Layer 5 pyramidal neurons of the mouse sensorimotor cortex | 1 block (600 pulses) of subthreshold iTBS | Hyperpolarized AP threshold (–1.76 ± 1.13 mV). Increase in AP firing frequency (+1.74 ± 0.32 Hz) | Increase in AP firing frequency (+3.33 ± 0.54 Hz) | Hyperpolarized AP threshold (–2.08 ± 1.60 mV). Increase in AP firing frequency (+4.44 ± 0.61 Hz) | |

| Hoppenrath and others (2016) | Layer 2/3 fast-spiking interneurons of the rat cortex | 3 blocks of suprathreshold iTBS (3 × 600 pulses separated by 15 min) | Increase in AP firing frequency. Increase in resting membrane potential (32-35 d old: sham −71 ± 2 mV vs. iTBS −57 ± 3 mV; 36-38 d old: sham −71 ± 2 mV vs. verum −57 ± 3 mV). |

Blank cells indicate not applicable. AP = action potential; iTBS = intermittent θ burst stimulation; rTMS = repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation.

Maladaptive Intrinsic Plasticity in Neurological Disorders

While intrinsic plasticity mechanisms are important in the regulation of neuronal excitability in the intact and healthy brain, maladaptive intrinsic plasticity is also known to occur and has been implicated in several neurological disorders and conditions. The following section discusses maladaptive intrinsic plasticity occurring in stroke and Alzheimer’s disease, before speculating whether rTMS has the potential to treat these conditions via intrinsic mechanisms.

Stroke

Maladaptive plasticity of neuronal excitability is a common consequence of stroke. In clinical and animal models of stroke of the motor cortex, neurons in the peri-infarct region display decreased excitability, as do connecting neurons from ipsilesional and contralesional cortical regions, while neurons in the contralesional hemisphere are thought to become hyperexcitable (Boddington and others 2020; Carmichael 2012; Cirillo and others 2020; Clarkson and others 2010). While synaptic mechanisms such as impaired neuronal connectivity have been well documented following stroke, a growing body of evidence suggests that intrinsic changes also contribute to the impaired neuronal excitability poststroke. For example, stroke has been shown to induce abnormal structural plasticity of the AIS, which, due to its role in AP initiation, is proposed to have profound consequences on neuronal firing behaviors and subsequent neuronal excitability. Two weeks after focal cortical stroke to the mouse motor cortex, the length of the AIS in cortical excitatory neurons in the peri-infarct region was decreased by ~3 µm (Hinman and others 2013). The shortening of the AIS occurred at the distal end of the AIS and, as a consequence, led to an overall reduction in Nav1.6 channels. Functionally, a loss of Nav1.6 channels is expected to reduce excitability, as Nav1.6 channels are responsible for the initiation and forward propagation of APs (Hu and others 2009). Therefore, a loss of Nav1.6 channels in addition to an overall reduction in AIS length may in part explain decreased neuronal excitability that is typically observed in the peri-infarct region. Similar disruptions to AIS structure have been reported following oxygen-glucose deprivation (a common model of stroke), such as the loss of essential cytoskeletal proteins βIV-spectrin and ankyrin G (Schafer and others 2009), which are integral for the formation and maintenance of the AIS alongside the recruitment and tethering of AIS ion channels (Leterrier 2018; Schafer and others 2009). Unsurprisingly, disruption of these cytoskeletal proteins resulted in a loss of Nav channels at the AIS (Schafer and others 2009). Although neuronal excitability was not measured in either of these studies, similar decreases in AIS length (~3.5 µm) coupled with reductions in ankyrin G expression and Nav distribution in non-stroke studies have resulted in a significant reduction in neuronal excitability (Evans and others 2015). Thus, while it seems likely that stroke-induced reductions in AIS length alters neuronal excitability, further studies are required to confirm this.

Maladaptive neuronal excitability has been shown to contribute to secondary consequences of stroke, such as epilepsy. The process of stroke-induced epileptogenesis is thought to occur due to secondary damage to the thalamus, which is known to be involved in epileptic activity (Detre and others 1996). After delivering a focal photothrombotic stroke in the rat somatosensory cortex, Paz and others (2013) found excitability changes in the functionally related thalamus, including increased intrinsic excitability of thalamocortical neurons in the ipsilesional hemisphere. While AP properties were unchanged, there was a significant increase in input resistance that resulted from a reduction in neuronal membrane area. Moreover, HCN channel–mediated Ih was significantly altered such that the activation kinetics were increased and the half-activation voltage was more depolarized, in turn increasing the number of HCN channels open at the resting membrane potential. As a consequence of thalamocortical neuronal hyperexcitability, patch-clamp recordings revealed robust spontaneous epileptiform network oscillations generated in thalamic slices poststroke, highlighting a stroke-induced intra-thalamic network of hyperexcitable cells that over time, led to epileptic activity. This epileptic activity could be terminated by selectively inhibiting ipsilesional thalamocortical neurons with optogenetic light stimulation, essentially abolishing epileptic activity in the ipsilesional and contralesional hemispheres and rescuing postinjury thalamic and cortical activity. Collectively, these studies highlight maladaptive intrinsic plasticity as not only a consequence of stroke, but also a potential therapeutic target.

Alzheimer’s Disease

Similar to stroke, the dysregulation of neuronal excitability is known to play a prominent role in the pathophysiology of conditions such as Alzheimer’s disease. In its early stages, Alzheimer’s models of cortical and hippocampal neuronal networks are known to become hyperactive, in part due to alterations in the intrinsic properties of various neuronal populations (Dickerson and others 2005; Reiman and others 2012). For example, hyperexcitability of CA1 pyramidal neurons of the hippocampus is thought to arise from a depletion of dendritic Kv4.2 channels (Hall and others 2015), which under normal conditions provide a hyperpolarizing current that dampens dendritic excitability and gates synaptic plasticity by attenuating backpropagation of APs to dendritic processes (Hoffman and others 1997; Kim and others 2005). When Kv4.2 channels are downregulated, as observed in preclinical models of Alzheimer’s disease, this hyperpolarizing current is attenuated, in turn increasing dendritic excitability and overall intrinsic neuronal excitability (Hall and others 2015). This increased neuronal excitability is then thought to contribute to the learning and memory deficits observed in Alzheimer’s disease by essentially dysregulating the equilibrium of network-wide activity and instead driving it toward a hyperactive state (Hall and others 2015). Pyramidal neuron hyperexcitability has also been reported as a consequence of the interactions between β-amyloid peptides (which are thought to play a causal role in Alzheimer’s pathogenesis) and Nav channels. Specifically, β-amyloid increased the expression of Nav1.6 channels, which, as a result, decreased AP threshold and increased AP firing frequencies, implicating Nav channel regulation as another intrinsic mechanism that underlies the progression of Alzheimer’s disease (Wang and others 2016).

In addition to altered pyramidal neuron excitability, a hyperactive network is thought to arise from impaired inhibition of network activity. In a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease, parvalbumin interneurons display reduced Nav1.1 channel densities, which is thought to contribute to a reduction in inhibitory neuronal excitability (Verret and others 2012). Additionally, interneurons of the mouse dentate gyrus have been shown to not generate APs as reliably as healthy control mice, leading to abnormal firing patterns and impaired network inhibition (Perez and others 2016). Moreover, these interneurons had a more depolarized resting membrane potential and smaller AP amplitudes, which is thought to further contribute to abnormal firing patterns (Perez and others 2016). Thus, it appears that a combination of both hyperexcitability of excitatory pyramidal neurons and dysfunctional inhibitory neuronal activity contributes to the early pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease.

Taken together, these findings provide evidence that maladaptive intrinsic plasticity contributes to stroke and Alzheimer’s disease (Table 2). Moreover, as our understanding of intrinsic mechanisms and their role in neurological disease continues to increase, intrinsic plasticity will likely be classed as a promising target for the treatment of these conditions. Therefore, while there is much more to discover on the role of maladaptive intrinsic plasticity in neurological disorders, there is a crucial need to develop tools that target and treat intrinsic plasticity mechanisms. Currently, rTMS is used experimentally to treat stroke, but these protocols target stroke-induced synaptic dysfunction, with little consideration given to the contribution of intrinsic mechanisms. Thus, while it is tempting to explore the use of rTMS to treat neurological dysfunction, we argue that the priority should be to first investigate how rTMS modulates the different intrinsic plasticity mechanisms in the intact brain. By characterizing rTMS-induced intrinsic plasticity in response to different stimulation protocols (frequency, duration etc) and in brain regions, cell types, and ages, a more targeted use of rTMS to treat impaired intrinsic plasticity can be applied.

Table 2.

Intrinsic Plasticity Occurring in Stroke and Alzheimer’s Disease.

| Neurological Condition: Study | Cortical Region / Neuronal Type | Intrinsic Modulation | Effect |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stroke | |||

| Hinman and others (2013) | Glutamatergic neurons of the mouse motor cortex / peri-infarct region | Altered AIS structure: AIS shorter and Nav1.6 channel density reduced | Not confirmed but thought to contribute to neuronal hypoexcitability poststroke |

| Schafer and others (2009) | Rat and mice primary cortical and hippocampal neuronal cultures | Altered AIS structure: loss of AIS cytoskeletal proteins and Nav channels | Not confirmed but thought to contribute to neuronal hypoexcitability poststroke |

| Paz and others (2013) | Rat thalamocortical neurons following stroke of the somatosensory cortex | Increased input resistance, increased Ih current conductance | Hyperexcitability of thalamocortical neurons, epileptogenesis |

| Alzheimer’s disease | |||

| Hall and others (2015) | Mouse CA1 pyramidal neurons | Depletion of dendritic Kv4.2 channels, which is thought to increase dendritic excitability | Increased excitatory network activity |

| Wang and others (2016) | Primary culture pyramidal neurons from amyloid precursor protein / presenilin 1 mice | Beta-amyloid–induced upregulation of Nav1.6 channels, with decreased AP threshold (i.e., more hyperpolarized) and increased firing frequency | Increased excitatory network activity |

| Perez and others (2016) | Inhibitory neurons of the mouse dentate gyrus | More depolarized resting membrane potential and smaller AP amplitude | Thought to contribute to reduced inhibitory excitability and reduced network inhibition |

| Verret and others (2012) | Mouse inhibitory parvalbumin neurons | Downregulation of Nav1.1 channels | Thought to contribute to reduced inhibitory excitability and reduced network inhibition |

AP = action potential; AIS = axon initial segment.

Does rTMS-Induced Intrinsic Plasticity Occur Independently of Synaptic Plasticity?

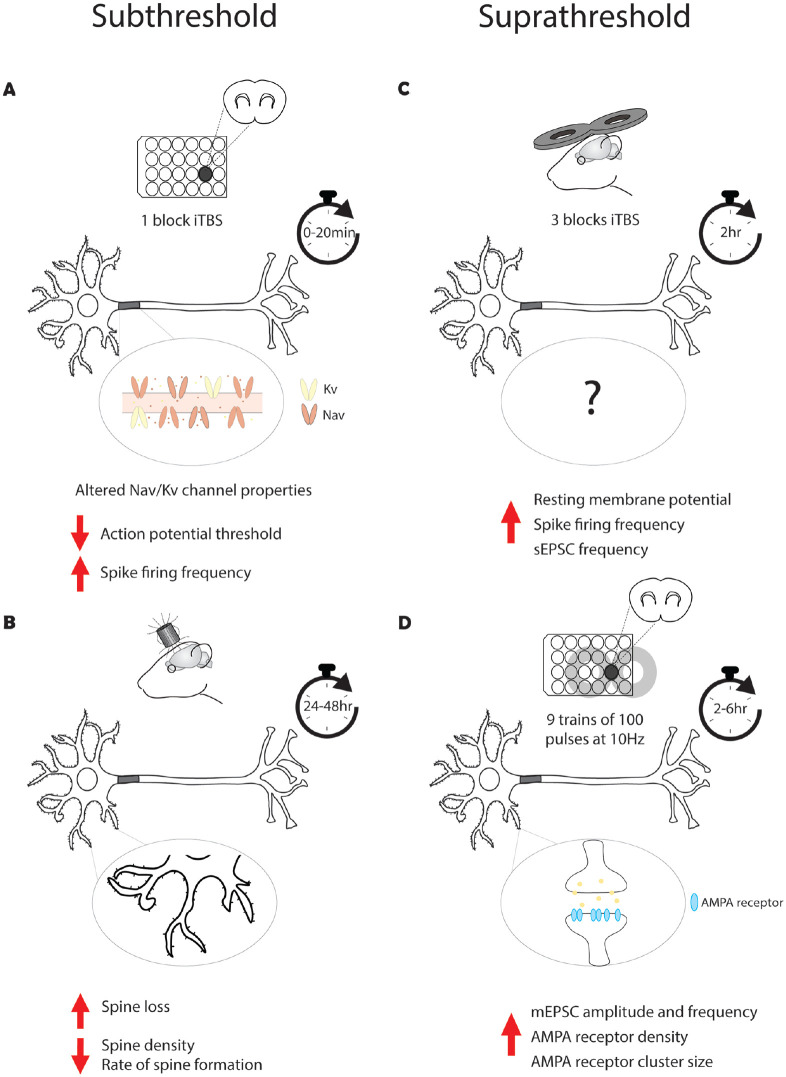

Up to this point, we have discussed rTMS-induced intrinsic plasticity independently from rTMS-induced synaptic plasticity. However, it is currently unknown if they occur simultaneously or if one drives the other, and if so, which mechanism is induced first? Understanding when each form of plasticity is induced is crucial to our interpretation of the effects and use of rTMS. Here we discuss the evidence for each possibility (Fig. 3)

Figure 3.

Time course of intrinsic and synaptic plasticity in response to repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS). A single block of subthreshold intermittent θ burst stimulation (iTBS; 600 pulses) has been shown to induce immediate intrinsic plasticity via a decrease in action potential threshold and an increase in spike firing frequency (Tang and others 2016) (A), while changes in synaptic plasticity occur 24 to 48 h post-stimulation, suggesting that intrinsic plasticity precedes synaptic plasticity (Tang and others 2021) (B). Three blocks of suprathreshold iTBS have resulted in intrinsic plasticity measured at 2 h post-stimulation (Hoppenrath and others 2016) (C), while 10-Hz rTMS has been shown to induce long-term potentiation-like plasticity at 2 to 6 h post-stimulation, again suggesting that rTMS-induced intrinsic plasticity occurs before synaptic plasticity (Vlachos and others 2012) (D). Although no study has directly recorded rTMS-induced intrinsic and synaptic plasticity, these findings provide insight into the potential temporal relationship between these forms of plasticity. AMPA= α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic; Kv = voltage-gated potassium; mEPSC = miniature excitatory postsynaptic current; Nav = voltage-gated sodium; NMDA = N-methyl-d-aspartate; sEPSC = spontaneous excitatory postsynaptic current.

As there has been no study to date that has directly compared the time course of the different forms of plasticity following rTMS, it is difficult to speculate which mechanism occurs first, and it is very much a “chicken or the egg” scenario. In the pivotal studies conducted in the hippocampus by the Vlachos laboratory, repetitive magnetic stimulation was shown to strengthen excitatory synapses of CA1 pyramidal neurons in vitro (Fig. 3D). Interestingly, the increase in synapse strength and accompanying structural changes, such as dendritic spine size and AMPA receptor subunit cluster size and density, took >2 h to develop (Vlachos and others 2012). While there was an immediate increase in the number of functional synapses post-stimulation, these measurements were pooled from recordings made in the 0 to 2 h post-stimulation, making it difficult to determine how soon after stimulation the change in functional synapses occurred. In comparison, Tang and others (2016) showed that iTBS induces intrinsic plasticity immediately post-stimulation (Fig. 3A). While this may suggest that rTMS induces intrinsic plasticity before synaptic plasticity is induced, it is important to note that it is not possible to compare the published studies on the different forms of rTMS-induced plasticity, as they vary greatly in rTMS protocol, intensity of stimulation, neural circuits, and time post-stimulation investigated.

In studies outside the rTMS field, it is known that intrinsic plasticity can occur simultaneously with synaptic plasticity. In the hippocampus, the induction of long-term potentiation in CA1 pyramidal neurons with direct electrical stimulation results in a concurrent decrease in AP threshold (Xu and others 2005). Similarly, the induction of long-term depression in cerebellar Purkinje cell synapses with direct electrical stimulation is accompanied by a concurrent decrease in neural excitability, with a decrease in the evoked AP firing frequency and a decrease in input resistance (Shim and others 2017). Unfortunately, there is only indirect evidence to suggest that rTMS-induced intrinsic and synaptic plasticity occur simultaneously. Hoppenrath and others (2016) observed iTBS-induced intrinsic plasticity ~2 h post-stimulation in the cortex (Fig. 3C), which overlaps with the 2 h time point of synaptic plasticity induction observed in the hippocampus. However, the iTBS was given in vivo, and the measurements ~2 h post-stimulation were the earliest that in vitro recordings could be made due to the time needed to prepare brain slices. Therefore, it is not known whether changes in intrinsic excitability were also present immediately post-stimulation, as observed by Tang and others.

Assuming a temporal order of rTMS-induced plasticity mechanisms (i.e., that one occurs before the other), could one form of rTMS-induced plasticity promote or affect the other? This is an interesting prospect, as it suggests that rTMS could be used to enhance or regulate the induction of subsequent plasticity in the brain, known as metaplasticity (see Abraham 2008 for a comprehensive review on metaplasticity). Intrinsic plasticity is a known mechanism of metaplasticity, as changes to neuronal excitability affect the depolarization-dependent mechanisms of synaptic plasticity. For example, altering intrinsic membrane properties changes the amount of long-term potentiation that can be induced in the hippocampus with direct electrical stimulation (Ramakers and Stormt 2002). Similarly, by using behavior as the driver of plasticity, environmental enrichment has been shown to enhance the amount of long-term potentiation that can be induced in the hippocampus with electrical stimulation (Malik and Chattarji 2012). The greater amount of LTP was attributed to the hyperpolarized AP threshold and increased evoked AP firing frequency present in CA1 pyramidal neurons after the enrichment. Whether this occurs following rTMS is unclear as the evidence for rTMS-induced intrinsic plasticity serving as a metaplastic mechanism is indirect, with subthreshold iTBS—which is known to induce intrinsic plasticity in vitro—delivered before or after skilled motor training enhancing the rate of learning and performance in adult mice (Tang and others 2018), potentially by enhancing the synaptic plasticity needed for learning (Tang and others 2021). While the concept of rTMS affecting subsequent synaptic plasticity is not a new concept (see Müller-Dahlhaus and Ziemann 2015 for review), rTMS-induced metaplasticity through the induction of intrinsic plasticity is novel and offers an alternative interpretation to the metaplastic effects observed with rTMS.

Conclusion and Future Directions

Despite the widespread use of rTMS in clinical and basic neuroscience, we are still just beginning to understand the cellular mechanisms that underlie its effect on neural plasticity. While there has been considerable evidence to support synaptic mechanisms underlying rTMS-induced plasticity (Lenz and others 2015; Lenz and others 2016; Tang and others 2021; Vlachos and others 2012), emerging evidence suggests a role for intrinsic plasticity, prompting a significant shift in our understanding of how rTMS alters neural excitability and neural plasticity.

In this review, we have described how a protocol of rTMS designed to mimic exogenous brain activity (iTBS) drives intrinsic plasticity at the single-cell level, and how these intrinsic targets of rTMS overlap with ones known to be maladaptive in neurological conditions such as stroke and Alzheimer’s disease. Expanding our knowledge or rTMS-induced intrinsic plasticity will advance our basic understanding of how rTMS alters the brain and provide a foundation of how rTMS can be used to study or treat maladaptive intrinsic plasticity, such as AIS plasticity disorders. Moving forward, it will be critical to investigate which protocols of rTMS (high/low-frequency rTMS, continuous θ burst stimulation, etc.) drive intrinsic plasticity and the type of intrinsic mechanisms they modulate. For example, can an “inhibitory” protocol of rTMS, such as continuous θ burst stimulation, reduce neuronal excitability via intrinsic modulation? Moreover, it will be essential to investigate how rTMS-induced intrinsic plasticity at the single-cell level affects neural activity at the circuit and network level, and how this subsequently affects function and/or behavior. Thus, while there is still much to uncover, we hope that this review will provide a new perspective on rTMS-induced plasticity and the need to expand our mechanistic understanding of rTMS beyond the synapse.

Acknowledgments

We thank Marissa Penrose-Menz for her assistance in figure design and construction.

Footnotes

Author Contributions: Both authors conceived and designed the review; Emily S. King drafted the manuscript; both authors edited the manuscript, approved the final copy, and are fully accountable for all aspects of the work.

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by the Raine Medical Research Foundation (RPG06-20, 2020) and the Western Australian Future Health and Research Innovation Fund (WANMA-Ideas 2021).

ORCID iD: Emily S. King  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6220-9027

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6220-9027

References

- Abraham W. 2008. Metaplasticity: tuning synapses and networks for plasticity. Nat Rev Neurosci 9:387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barker AT, Jalinous R, Freeston IL. 1985. Non-invasive magnetic stimulation of the human motor cortex. Lancet 325:1106–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benned-Jensen T, Christensen RK, Denti F, Perrier JF, Rasmussen HB, Olesen SP. 2016. Live imaging of kv7.2/7.3 cell surface dynamics at the axon initial segment: high steady-state stability and calpain-dependent excitotoxic downregulation revealed. J Neurosci 36:2261–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boddington LJ, Gray JP, Schulz JM, Reynolds JNJ. 2020. Low-intensity contralesional electrical theta burst stimulation modulates ipsilesional excitability and enhances stroke recovery. Exp Neurol 323:113071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campanac E, Gasselin C, Baude A, Rama S, Ankri N, Debanne D. 2013. Enhanced intrinsic excitability in basket cells maintains excitatory-inhibitory balance in hippocampal circuits. Neuron 77:712–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carmichael ST. 2012. Brain excitability in stroke: the yin and yang of stroke progression. Arch Neurol 69:161–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chand AN, Galliano E, Chesters RA, Grubb MS. 2015. A distinct subtype of dopaminergic interneuron displays inverted structural plasticity at the axon initial segment. J Neurosci 35:1573–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cirillo C, Brihmat N, Castel-Lacanal E, le Friec A, Barbieux-Guillot M, Raposo N, and others. 2020. Post-stroke remodeling processes in animal models and humans. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 40:3–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarkson AN, Huang BS, Macisaac SE, Mody I, Carmichael ST. 2010. Reducing excessive GABA-mediated tonic inhibition promotes functional recovery after stroke. Nature 468:305–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cullen CL, Young KM. 2016. How does transcranial magnetic stimulation influence glial cells in the central nervous system? Front Neural Circuits 10:26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Debanne D, Inglebert Y, Russier M. 2019. Plasticity of intrinsic neuronal excitability. Curr Opin Neurobiol 54:73–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Detre JA, Alsop DC, Aguirre GK, Sperling MR. 1996. Coupling of cortical and thalamic ictal activity in human partial epilepsy: demonstration by functional magnetic resonance imaging. Epilepsia 37:657–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickerson BC, Salat DH, Greve DN, Chua EF, Rand-Giovannetti E, Rentz DM, and others. 2005. Increased hippocampal activation in mild cognitive impairment compared to normal aging and AD. Neurology 65:404–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans MD, Dumitrescu AS, Kruijssen DLH, Taylor SE, Grubb MS. 2015. Rapid modulation of axon initial segment length influences repetitive spike firing. Cell Rep 13:1233–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faber ESL, Delaney AJ, Sah P. 2005. SK channels regulate excitatory synaptic transmission and plasticity in the lateral amygdala. Nat Neurosci 8:635–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan Y, Fricker D, Brager DH, Chen X, Lu HC, Chitwood RA, and others. 2005. Activity-dependent decrease of excitability in rat hippocampal neurons through increases in Ih. Nat Neurosci 8:1542–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fékété A, Ankri N, Brette R, Debanne D. 2021. Neural excitability increases with axonal resistance between soma and axon initial segment. PNAS 118:33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Funke K. 2018. Transcranial magnetic stimulation of rodents: repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation—a noninvasive way to induce neural plasticity in vivo and in vitro. Handbook of Behavioral Neuroscience 28:365–87. [Google Scholar]

- Galliano E, Hahn C, Browne LP, Villamayor PR, Tufo C, Crespo A, and others. 2021. Brief sensory deprivation triggers cell type-specific structural and functional plasticity in olfactory bulb neurons. J Neurosci 41:2135–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goethals S, Brette R. 2020. Theoretical relation between axon initial segment geometry and excitability. Elife 9:e53432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goetz SM, Luber B, Lisanby SH, Murphy DL, Kozyrkov IC, Grill WM, Peterchev AV. 2016. Enhancement of neuromodulation with novel pulse shapes generated by controllable pulse parameter transcranial magnetic stimulation. Brain Stim 9:39–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grubb MS, Burrone J. 2010. Activity-dependent relocation of the axon initial segment fine-tunes neuronal excitability. Nature 465:1070–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gulledge AT, Bravo JJ. 2016. Neuron morphology influences axon initial. eNeuro 3:ENEURO.0085-15.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall AM, Throesch BT, Buckingham SC, Markwardt SJ, Peng Y, Wang Q, and others. 2015. Tau-dependent Kv4.2 depletion and dendritic hyperexcitability in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurosci 35:6221–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamada MS, Goethals S, de Vries SI, Brette R, Kole MHP. 2016. Covariation of axon initial segment location and dendritic tree normalizes the somatic action potential. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 113:14841–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinman JD, Rasband MN, Carmichael ST. 2013. Remodeling of the axon initial segment after focal cortical and white matter stroke. Stroke 44:182–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodgkin AL, Huxley AF. 1952. Currents carried by sodium and potassium ions through the membrane of the giant axon of Loligo. J Physiol 116:449–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman DA, Magee JC, Colbert CM, Johnston D. 1997. K+ channel regulation of signal propagation in dendrites of hippocampal pyramidal neurons. Nature 387:869–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoppenrath K, Funke K. 2013. Time-course of changes in neuronal activity markers following iTBS-TMS of the rat neocortex. Neurosci Lett 536:19–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoppenrath K, Härtig W, Funke K. 2016. Intermittent theta-burst transcranial magnetic stimulation alters electrical properties of fast-spiking neocortical interneurons in an age-dependent fashion. Front Neural Circuits 10:1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu W, Tian C, Li T, Yang M, Hou H, Shu Y. 2009. Distinct contributions of Nav1.6 and Nav1.2 in action potential initiation and backpropagation. Nat Neurosci 12:996–1002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang YZ, Edwards MJ, Rounis E, Bhatia KP, Rothwell JC. 2005. Theta burst stimulation of the human motor cortex. Neuron 45:201–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jamann N, Dannehl D, Lehmann N, Wagener R, Thielemann C, Schultz C, and others. 2021. Sensory input drives rapid homeostatic scaling of the axon initial segment in mouse barrel cortex. Nat Commun 12:1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jamann N, Jordan M, Engelhardt M. 2018. Activity-dependent axonal plasticity in sensory systems. Neurosci 368:268–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kase D, Imoto K. 2012. The role of HCN channels on membrane excitability in the nervous system. J Sign Transduct 2012:1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kida H, Tsuda Y, Ito N, Yamamoto Y, Owada Y, Kamiya Y, and others. 2016. Motor training promotes both synaptic and intrinsic plasticity of layer II/III pyramidal neurons in the primary motor cortex. Cereb Cortex 26:3494–507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J, Wei DS, Hoffman DA. 2005. Kv4 potassium channel subunits control action potential repolarization and frequency-dependent broadening in rat hippocampal CA1 pyramidal neurones. J Physiol 569:41–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kole MH, Brette R. 2018. The electrical significance of axon location diversity. Curr Opin Neurobiol 51:52–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kole MHP, Ilschner SU, Kampa BM, Williams SR, Ruben PC, Stuart GJ. 2008. Action potential generation requires a high sodium channel density in the axon initial segment. Nat Neurosci 11:178–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuba H, Oichi Y, Ohmori H. 2010. Presynaptic activity regulates Na+ channel distribution at the axon initial segment. Nature 465:1075–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamas JA, Reboreda A, Codesido V. 2002. Ionic basis of the resting membrane potential in cultured rat sympathetic neurons. NeuroReport 13:585–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenz M, Galanis C, Müller-Dahlhaus F, Opitz A, Wierenga CJ, Szabó G, and others. 2016. Repetitive magnetic stimulation induces plasticity of inhibitory synapses. Nat Commun 7:10020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenz M, Platschek S, Priesemann V, Becker D, Willems LM, Ziemann U, and others. 2015. Repetitive magnetic stimulation induces plasticity of excitatory postsynapses on proximal dendrites of cultured mouse CA1 pyramidal neurons. Brain Struct Funct 220:3323–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leterrier C. 2018. The axon initial segment: an updated viewpoint. J Neurosci 38:2135–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magee JC. 1999. Dendritic Ih normalizes temporal summation in hippocampal CA1 neurons. Nat Neurosci 2:508–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malik R, Chattarji S. 2012. Enhanced intrinsic excitability and EPSP-spike coupling accompany enriched environment-induced facilitation of LTP in hippocampal CA1 pyramidal neurons. J Neurophysiol 107:1366–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mellor J, Nicoll RA, Schmitz D. 2002. Mediation of hippocampal mossy fiber long-term potentiation by presynaptic Ih channels. Science 295:143–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Müller-Dahlhaus F, Ziemann U. 2015. Metaplasticity in human cortex. Neuroscientist 21:185–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paz JT, Davidson TJ, Frechette ES, Delord B, Parada I, Peng K, and others. 2013. Closed-loop optogenetic control of thalamus as a tool for interrupting seizures after cortical injury. Nat Neurosci 16:64–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez C, Ziburkus J, Ullah G. 2016. Analyzing and modeling the dysfunction of inhibitory neurons in Alzheimer’s disease. PLoS One 11:1–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rall W. 1969. Distributions of potential in cylindrical coordinates and time constants for a membrane cylinder. Biophys J 9:1509–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramakers GMJ, Stormt JF. 2002. A postsynaptic transient K+ current modulated by arachidonic acid regulates synaptic integration and threshold for LTP induction in hippocampal pyramidal cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 99:10144–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiman EM, Quiroz YT, Fleisher AS, Chen K, Velez-Pardo C, Jimenez-Del-Rio M, and others. 2012. Brain imaging and fluid biomarker analysis in young adults at genetic risk for autosomal dominant Alzheimer’s disease in the presenilin 1 E280A kindred: a case-control study. Lancet Neurol 11:1048–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross ST, Soltesz I. 2000. Selective depolarisation of interneurons in the early posttraumatic dentate gyrus: involvement of the Na+/K+-ATPase. J Neurophysiol 83:2916–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross ST, Soltesz I. 2001. Long-term plasticity in interneurons of the dentate gyrus. PNAS 98:8874–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowan MJM, Tranquil E, Christie JM. 2014. Distinct Kv channel subtypes contribute to differences in spike signalling properties in the axon initial segment and presynaptic boutons of cerebellar interneurons. J Neurosci 34:6611–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salinas E, Sejnowski TJ. 2000. Impact of correlated synaptic input on output firing rate and variability in simple neuronal models. J Neurosci 20:6193–209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schafer DP, Jha S, Liu F, Akella T, McCullough LD, Rasband MN. 2009. Disruption of the axon initial segment cytoskeleton is a new mechanism for neuronal injury. J Neurosci 29:13242–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sehgal M, Song C, Ehlers VL, Moyer JR. 2013. Learning to learn—intrinsic plasticity as a metaplasticity mechanism for memory formation. Neurobiol Learn Mem 105:186–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shim HG, Jang DC, Lee J, Chung G, Lee S, Kim YG, and others. 2017. Long-term depression of intrinsic excitability accompanied by synaptic depression in cerebellar Purkinje cells. J Neurosci 37:5659–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stuart G, Hausser M. 2001. Dendritic coincidence detection of EPSPs and action potentials. Nat Neurosci 4:63–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stuart G, Sakmann B. 1995. Amplification of EPSPs by axosomatic sodium channels in neocortical pyramidal neurons. Neuron 15:1065–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stuart G, Spruston N, Sakmann B, Häusser M. 1997. Action potential initiation and backpropagation in neurons of the mammalian CNS. Trends Neurosci 20:125–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun J, Liu Y, Baudry M, Bi X. 2020. SK2 channel regulation of neuronal excitability, synaptic transmission, and brain rhythmic activity in health and diseases. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Cell Res 1867:118834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang AD, Bennett W, Bindoff AD, Bolland S, Collins J, Langley RC, and others. 2021. Subthreshold repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation drives structural synaptic plasticity in the young and aged motor cortex. Brain Stimul 14:1498–507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang AD, Bennett W, Hadrill C, Collins J, Fulopova B, Wills K, and others. 2018. Low intensity repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation modulates skilled motor learning in adult mice. Sci Rep 8:1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang AD, Hong I, Boddington LJ, Garrett AR, Etherington S, Reynolds JNJ, and others. 2016. Low-intensity repetitive magnetic stimulation lowers action potential threshold and increases spike firing in layer 5 pyramidal neurons in vitro. Neurosci 335:64–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang AD, Thickbroom G, Rodger J. 2017. Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation of the brain: mechanisms from animal and experimental models. Neuroscientist 1:82–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trippe J, Mix A, Aydin-Abidin S, Funke K, Benali A. 2009. Theta burst and conventional low-frequency rTMS differentially affect GABAergic neurotransmission in the rat cortex. Exp Brain Res 199:411–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verret L, Mann EO, Hang GB, Barth AMI, Cobos I, Ho K, and others. 2012. Inhibitory interneuron deficit links altered network activity and cognitive dysfunction in Alzheimer model. Cell 149:708–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vlachos A, Müller-Dahlhaus F, Rosskopp J, Lenz M, Ziemann U, Deller T. 2012. Repetitive magnetic stimulation induces functional and structural plasticity of excitatory postsynapses in mouse organotypic hippocampal slice cultures. J Neurosci 32:17514–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wahl-Schott C, Biel M. 2009. HCN channels: structure, cellular regulation and physiological function. Cell and Mol Life Sci 66:470–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Zhang XG, Zhou TT, Li N, Jang CY, Xiao ZC, and others. 2016. Elevated neuronal excitability due to modulation of the voltage-gated sodium channel Nav1.6 by Aβ1-42. Front Neurosci 10:1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wassermann EM, Zimmermann T. 2012. Transcranial magnetic brain stimulation: therapeutic promises and scientific gaps. Pharmacol Ther 133:98–107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams SR, Stuart GJ. 2000. Site independence of EPSP time course is mediated by dendritic I(h) in neocortical pyramidal neurons. J Neurophysiol 83:3177–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams SR, Stuart GJ. 2003. Voltage- and site-dependent control of the somatic impact of dendritic IPSPs. J Neurosci 23:7358–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu J, Kang N, Jiang L, Nedergaard M, Kang J. 2005. Activity-dependent long-term potentiation of intrinsic excitability in hippocampal CA1 pyramidal neurons. J Neurosci 25: 1750–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamada R, Ishiguro G, Adachi R, Kuba H. 2015. Redistribution of Kv1 and Kv7 enhances neuronal excitability during structural axon initial segment plasticity. Nat Commun 6:8815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]