Abstract

Jixueteng, the vine of the bush Spatholobus suberectus Dunn., is widely used to treat irregular menstruation and arthralgia. Yinyanghuo, the aboveground part of the plant Epimedium brevicornum Maxim., has the function of warming the kidney to invigorate yang. This research aimed to investigate the effects and mechanisms of the Jixueteng and Yinyanghuo herbal pair (JYHP) on cisplatin-induced myelosuppression in a mice model. Firstly, ultra-high performance liquid chromatography quadrupole time-of-flight mass spectrometry (UPLC-Q-TOF/MS) screened 15 effective compounds of JYHP decoction. Network pharmacology enriched 10 genes which may play a role by inhibiting the apoptosis of bone marrow (BM) cells. Then, a myelosuppression C57BL/6 mice model was induced by intraperitoneal (i.p.) injection of cis-Diaminodichloroplatinum (cisplatin, CDDP) and followed by the intragastric (i.g.) administration of JYHP decoction. The efficacy was evaluated by blood cell count, reticulocyte count, and histopathological analysis of bone marrow and spleen. Through the vivo experiments, we found the timing of JYHP administration affected the effect of drug administration, JYHP had a better therapeutical effect rather than a preventive effect. JYHP obviously recovered the hematopoietic function of bone marrow from the peripheral blood cell test and pathological staining. Flow cytometry data showed JYHP decreased the apoptosis rate of BM cells and the western blotting showed JYHP downregulated the cleaved Caspase-3/Caspase-3 ratios through RAS/MEK/ERK pathway. In conclusion, JYHP alleviated CDDP-induced myelosuppression by inhibiting the apoptosis of BM cells through RAS/MEK/ERK pathway and the optimal timing of JYHP administration was after CDDP administration.

Keywords: cisplatin, myelosuppression, traditional Chinese medicine, suberect Spatholobus stem, epimedium sagittatum

Introduction

cis-Diaminodichloroplatinum (cisplatin, CDDP), the first generation of platinum-based drugs, has been used for the treatment of ovarian, cervical, head and neck, and non-small-cell lung cancer and many other solid cancers. 1 However, CDDP induces DNA damage and apoptosis as it is non-specific to DNA replication. A series of adverse effects follows the anti-cancer effect including nephrotoxicity, neurotoxicity, gastrointestinal toxicity and hematological toxicity.2,3 Bone marrow (BM) is the organ where hemopoiesis occurs, and damage induced by myelosuppressive chemotherapy is manifested as anemia, erythropenia, neutropenia, and thrombocytopenia, which could cause dizziness and fatigue, and increase the risk of infection.4-6 Previous studies had shown that patients who received therapy with CDDP had a higher frequency of micronucleus in peripheral blood lymphocytes which means they were vulnerable to myelosuppression in the long term. 7 Patients were forced to reduce the dose and the therapeutic effect was then limited by its toxic effect. 8

Clinics used to give iron supplements or transfusions for specific symptoms such as anemia. 9 For severe neutropenia, hematopoietic growth factors such as granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF), 10 granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF), 11 and erythropoietin (EPO), 12 were used to promote hematopoietic recovery. However, oral medicine always has a slow effect, and SCF and growth factors have high costs. Furthermore, recent research reported the increase of neutrophils after G-CSF administration could aggravate the extensive infiltration of immune cells into the lungs especially in COVID-19-infected patients. 13 Therefore, there is an urgent need for a safer and more economical treatment for CDDP-induced myelosuppression.

Research proved Tradition Chinese medicine (TCM) and natural products protect against CDDP-induced organ toxicity by inducing cell death through apoptosis or necrosis, showing an advantage in alleviating CDDP-induced myelosuppression. 14 Herniarin decreased the ROS level in bone marrow cells and the percentage of apoptotic cells to protect the hematopoietic function. 15 Flavored Guilu Erxian decoction could enhance the possibility of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells repairing after CDDP injury. 16 Chemotherapy was described as the evil of heat toxicity in TCM and patients presented with symptoms of fatigue and blood-insufficiency. JXT (Jixueteng) could revitalize and replenish blood. Studies have shown that JXT was an effective herb for the treatment of anemia. 17 YYH (Yinyanghuo), has the function of warming the kidney to reinforce Yang, strengthening tendons and bone. YYH could attenuate chemotherapy-induced myelosuppression and promotes immunefunction.18,19 However, studies mentioned before have shown that both JXT and YYH could restore the hematopoietic function alone; whether or how JXT and YYH herb pair play the same role still remains unclear.15,16

The main compounds in Jixueteng and Yinyanghuo herb pair (JYHP) decoction were determined by ultra-high performance liquid chromatography quadrupole time-of-flight mass spectrometry (UPLC-Q-TOF/MS). On account of the multi-compounds, multi-targets, and multi-pathways of JYHP effects, network pharmacology was utilized to do the preliminary screening work. Then we established a CDDP-induced myelosuppression mice model to validate the pharmacological mechanism of JYHP in attenuating CDDP-induced myelosuppression in vivo. To our knowledge, this study was the first to explore the combination mechanisms of JXT and YYH herb pair for CDDP-induced myelosuppression based on network pharmacology combined with vivo experiment validation.

Materials and Methods

Preparation of JYHP Decoction

Jixueteng (Batch number: 2230314Y) and Yinyanghuo (Batch number: 2220902Y) were purchased from Zhejiang Mintai Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. (Hangzhou, China). JYHP was prepared as a decoction (mass ratios were 1:1). The herbs were mixed to 25 g and added 250 mL water, then heated the mixture at 100℃ for 20 minutes after soaking for a half hour, filtered through 70 μm mesh and the suspension was collected. Subsequently, we added another 250 mL water and repeated the previous steps. Next, these 2 suspensions were mixed, evaporated, and concentrated to 2.4 g/mL in a 100℃ water bath. Finally, we centrifuged and collected the new suspensions for the in vivo experiments.

Active Ingredients Identification of JYHP

We constructed a self-built JYHP database and utilized ultra-high performance liquid chromatography quadrupole time-of-flight mass spectrometry (UPLC/Q-TOF/MS) to find out what active components were at work in our experiment. Firstly, the active components of JYHP were obtained from TCMSP (https://old.tcmsp-e.com/tcmsp.php) under the screening condition of oral bioavailability (OB) ≥ 30% and drug likeness (DL) ≥ 0.18. Next, we downloaded these chemical structural formulas on Chemical BooK (https://www.chemicalbook.com/ProductIndex.aspx). Then the UPLC/Q-TOF/MS detection results were imported into the database and compared to determine the components of JYHP in this study.

The principal components of JYHP were identified by ultra-high performance UPLC/Q-TOF/MS. Sample preparation: take 200 μL of JYHP prepared extract (2.4 g/mL) above and dissolve it in 5 times methanol to remove the protein. Fully vibrate and centrifuge at a speed of 12 000g for 10 minutes, filter the supernatant through a sterile 0.22 μm filter membrane, and blow dry the liquid with nitrogen. Then redissolve the solid with 100 uL of methanol. Chromatographic conditions: injection volume: 2 μL; mobile phase: A solvent (Acetonitrile); B solvent (0.1% formic acid-H2O); Flow rate: 0.3 mL/min; column temperature:35℃; Gradient elution method:the specific conditions are shown in Supplemental Table S1. Mass spectrometry method: ESI ion source was used to positive ion scan in MSE and continue full scan mode for 0.2 second, the scanned area was set to 50 to 1200. Collision energy is used in MSE, with a low impact energy of 6 V and high impact energy of 15 to 45 V. Sodium formate was used to correct the mass spectrometer and Leucine-Enkephalin in [M + H]+ =556.2771 to do an online correction. Ion source parameters are shown in Supplemental Table 1.

Network Pharmacology Analysis

Corresponding protein targets of JYHP screened components were searched on TCMSP and transferred to official symbols by utilizing UniProtKB (https://www.uniprot.org/). Genes related to myelosuppression were searched on GeneCards (http://www.genecards.org/), DisGeNET (https://www.disgenet.org/), OMIM (https://omim.org/), DigSee (http://gcancer.org/digsee)

Then we screened the overlapping genes as the targets and used STRING (https://cn.string-db.org/) and Cytoscape 3.9.1 (https://cytoscape.org/) to construct the protein-protein interaction (PPI) network. Subsequently, we screened the hub genes according to the degree and betweenness centrality. Next, we performed GO and KEGG Enrichment analysis on Metascape (https://metascape.org/gp/index.html#/main/step1) to explore the molecular mechanisms. We ranked the results according to the P value and visualized the results on Bioinformatics (https://bioinfogp.cnb.csic.es/tools/venny/index.html).

Chemicals and Reagents

The following reagents, kits, and antibodies were used: Cisplatin (Targrtmol, T1564, USA) Annexin V-APC/7-AAD apoptosis kit (AT105, Multi Science, China), Cleaved Caspase-3(#9664, Cell Signal Technology, CST), Caspase-3 (#9662, CST), β-Actin (#3700, CST), p-ERK1/2 (#4370, CST), Erk1/2(#4695, CST), p-MEK1/2 (#3958, CST), MEK1/2 (#9126, CST), RAS ( ER40115, HUABIO, China), HRP-labeled Goat Anti-rabbit IgG (1:1000 dilution, EpiZyme, LF102, China), HRP-labeled Goat Anti-Mouse IgG (1:2000 dilution, EpiZyme, LF101, China).

Animals and Administration

C57BL/6 mice aged 8 weeks and weighing 20to 25 g were purchased from Shanghai SIPPR-Bk Lab Animal Co. Ltd. (Shanghai, China), maintained at 24 ± 1℃, 50 ± 10% RH, and a 12 hour/12 hour light/dark cycle; provided with ad libitum food and water; and acclimatized for 7 days before the experiment. The mice and their ambient environment were regularly disinfected. All animal experiments were approved by the Institutional Animal Ethics Committee of NO. 20220801-07.

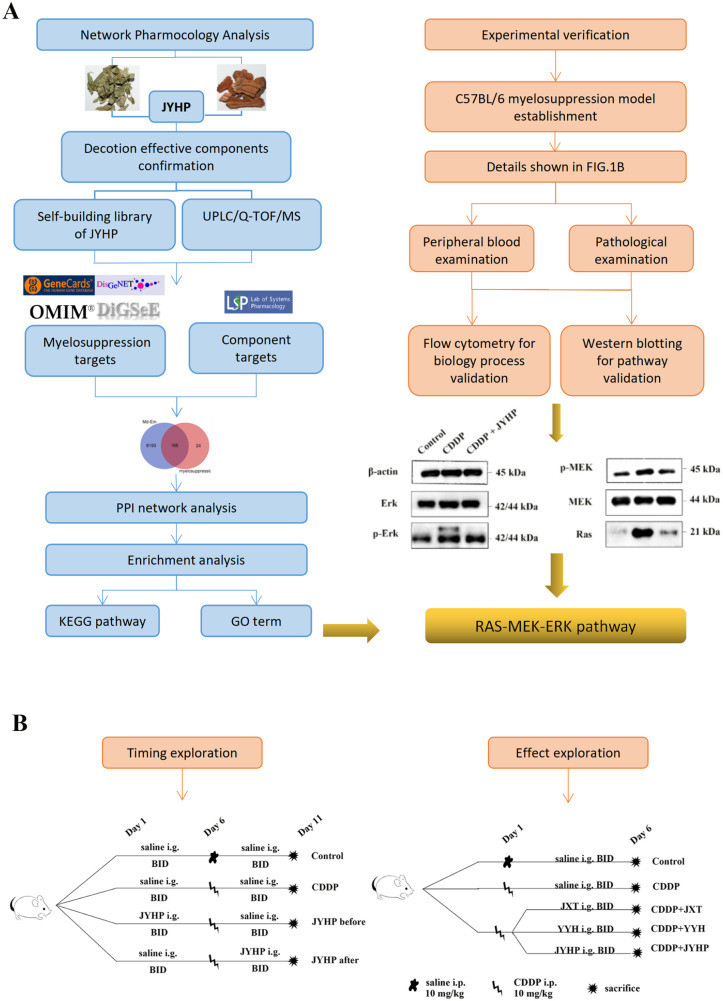

The mice experiments were divided into 2 parts. In the first part, we explored whether the timing of JYHP administration affects its efficacy. Twenty-four mice were randomized into four 4 groups which were control group, CDDP group, JYHP before CDDP group, JYHP after CDDP group. Each group had equal numbers of mice. CDDP was dissolved in normal saline at a concentration of 10 mg/kg for i.p. The second part was to explore the effect of JYHP and verify the results of network pharmacology. Thirty mice were divided into 5 groups: control group, CDDP group, JYHP group, Jixueteng group, Yinyanghuo group. The specific steps were shown in Figure 1B.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of JYHP alleviating myelosuppression: (A) flow chart of network pharmacology analysis and experiment validation and (B) flow chart of vivo experiment.

Blood Cell Counting

Peripheral blood samples were collected from mice eyes; complete blood count including Red Blood Cell (RBC), Hemoglobin (HGB), and Neutrophil (NEUT), Platelet (PLT), Reticulocyte (RET), White Blood Cell (WBC), Lymphocyte (LYM), immature reticulocyte fraction (IRF) were estimated using Sysmex XN-1000V automated hematology analyzer (Japan).

Hematoxylin and Eosin (HE) Staining

After sacrificing the mice, femurs and spleen were collected and fixed in 4% formaldehyde for more than 24 hours. Femurs were immersed in decalcification (updated for 3 days). Then embedded femurs and spleens in paraffin and sliced into 5 μm, stained with hematoxylin and eosin.

Cell Apoptosis Detection by Annexin V-APC/7-AAD Staining

Collected BM cells from mice and added RBC Lysis Buffer for 4 minutes. Centrifuged at 4℃ for 5 minutes and washed twice, then resuspended with 100 μL of binding buffer solution and incubated with 2 μL Annexin V-FITC and 4 μL 7-AAD at 4℃ for 10 minutes. After washing with PBS, assessed on Agilent NovoCyte. The data were analyzed with FlowJo VX (FlowJo LLC, Ashland, OR, USA).

Quantitative Real Time Polymerase Chain Reaction (qPCR)

Total RNA was extracted from the BM cells using SteadyPure RNA Extraction Kit (No. AG21024, Accurate Biotechnology, Ningbo, China) according to the instructions. Then total RNA was reverse transcribed into cDNA using Evo M-MLV RT Mix with gDNA Clean for qpcr (NO. AG11728, Accurate Biotechnology). RT-qPCR was performed using a SYBR Green Premix Pro Taq HS qPCR Kit (No. AG11701, Accurate Biotechnology). All primers were synthesized by Beijing Tsingke Biotech Co., Ltd. and shown in Supplemental Table 2.

Western Blotting Analysis

Cells were lysed with radioimmunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) buffer (Applygen Technologies Inc., Beijing, China). Protein content was assessed using a bicinchoninic acid (BCA) assay (No. P0010, Beyotime Biotechnology). The samples were denatured in 100℃ of metal bath for 15 minutes and stored at −20℃. 15 μg of the total protein were separated by 10% SDS-PAGE at 60to 120 V for 1.5 hours and transferred to a polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membrane (Millipore GmbH, Vienna, Austria) at the condition of 300 mAh for 45 minutes. Blocked the membrane with 5% (w/v) skim milk and hybridized to appropriate primary and HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies for subsequent detection in an enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) system (MP4+ ChemidocXRS; Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA). Differences in gray values were calculated with ImageJ (https://imagej.net/software/imagej/).

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed by one-way ANOVA using SPSS (version 21.0) software and presented as the mean ± SEM (standard deviations). P < .05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

The Relationship Between the Timing of JYHP Administration and Efficacy

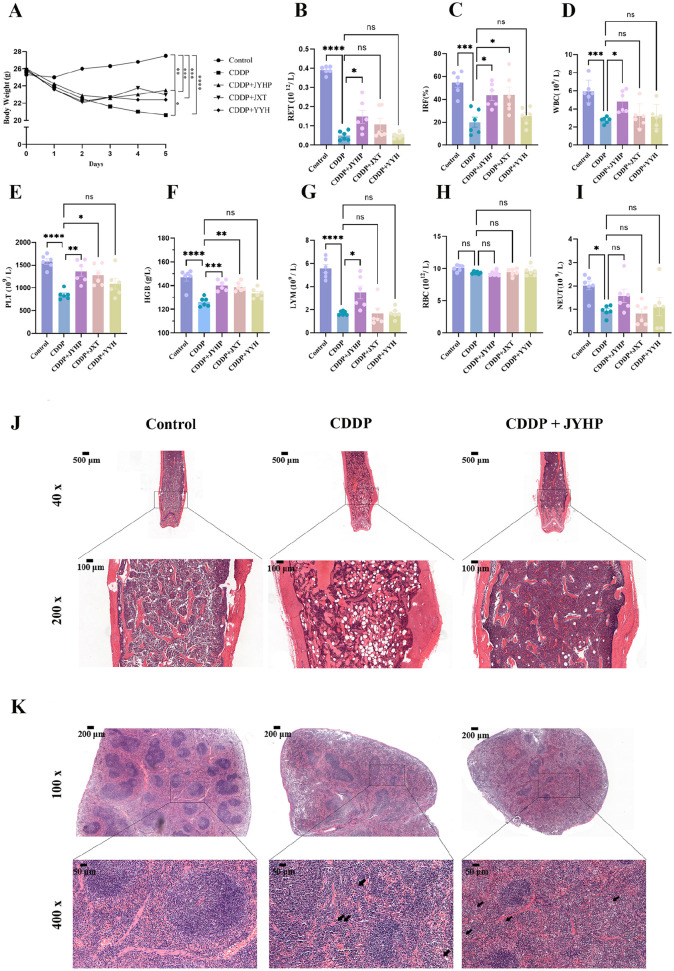

The results of the first part of the mice experiment showed that JYHP had efficacy in treating CDDP-induced myelosuppression and the timing of JYHP influenced its effectiveness. Compared with the control group, the count of RET (P < .0001), PLT (P < .05), WBC (P < .05), LYM (P < .01) and the body weight (P < .0001) in CDDP group significantly decreased (Figure 2A, B, and E-G). The count of RBC, HGB, and NEUT (Figure 2C, D, and H) did not show a noticeable rebound, possibly due the relatively long lifespan of RBCs. This indicated CDDP induced myelosuppression in mice at a dose of 10 mg/kg.

Figure 2.

Effect of JYHP on hematopoiesis: (A) body weight in each group, (B) RET count, (C) RBC count, (D) HGB count, (E) PLT count, (F) WBC count, (G) LYM count, (H) NEUT count. *P < .05, **P < .01, ***P < .001, ****P < .0001. Data was shown as mean ± SEM; n = 6.

We also found giving JYHP after CDDP improved the situation of the CDDP group in terms of body weight (P < .05)(Figure 2A), RET (P < .05)(Figure 2B), WBC (P < .05)(Figure 2F) and LYM (P < .05)(Figure 2G) while JYHP before CDDP did not show such effect. Therefore, administering JYHP after CDDP was more favorable than giving JYHP before CDDP, as it resulted in milder myelosuppression in mice. The treatment timing utilized for the remaining studies was the administration of JYHP after CDDP-induced myelosuppression.

Effect of JYHP on Peripheral Blood Cells and Bone Marrow in Myelosuppression Mice

Next, we investigated whether there are differences in the efficacy among the JYHP, JXT, and YYH. As Figure 3A shows, body weight significantly decreased after CDDP injecting (P < .0001). Only the JYHP group showed a significant increase in body weight compared to the CDDP group (P < .05). Reticulocyte percentage represents the hematopoietic capacity of the bone marrow, and the IRF has been proposed as a more sensitive marker of bone marrow regeneration after cytotoxic drug therapy. JYHP administration increased in terms of RET (P < .05) (Figure 3B) and IRF (P < .05) (Figure 3C) compared with the CDDP group. Additionally, the CDDP + JYHP group also exhibited significant improvement in the levels of WBC (P < .05), PLT (P < .01), HGB (P < .001), and LYM (P < .05) (Figure 3D-G) compared with the CDDP group, though RBC and NEUT (Figure 3H and I) did not show a significant change among these 3 treatment groups compared with the CDDP group. However, using JYX and YYH individually did not show such comprehensive efficacy, CDDP + JXY only increased IRF PLT and HGB, and CDDP + YYH alone did not improve any type of cell of peripheral blood. Therefore, we supposed that JYHP had better efficacy in treating CDDP-induced bone marrow suppression compared to single JXT or YYH therapy.

Figure 3.

Basic condition of C57BL/6 mice and pathological staining: (A) body weight in each group, (B-I) peripheral blood examination in each group, (J) HE staining of bone marrow, and (K) HE staining of the spleen, arrow refers to megakaryocytes. *P < .05, **P < .01, ***P < .001, ****P < .0001. Data was shown as mean ± SEM; n = 6.

From the HE staining of bone, we found BM cells decreased more severely in CDDP group than JYHP with CDDP group (Figure 3J). Meanwhile, the staining of spleen (Figure 3K) showed the structure of the marginal zone was destroyed and the boundary between red pulp and white pulp was not clear. Moreover, the red pulp was markedly expanded by numerous hematopoietic cells, including megakaryocytes (as shown by arrows) while being reduced in the JYHP group.

Effective Components From JYHP Decoction After UPLC-Q-TOF/MS

Typical total ion chromatogram (TIC) of JYHP decoction in positive mode is presented in (Figure 4A). After comparing with the self built JYHP database (based on TCMSP database), we finally identified 15 effective compounds of JYHP decoction (Figure 4B), including 6 components of JXT and 9 components of YYH.

Figure 4.

Determination of JYHP components: (A) UPLC-Q-TOF/MS chromatogram of JYHP decotion and (B) identifiable components of JYHP.

Acquisition of Core Targets of JYHP for Treating Myelosuppression

Network pharmacology analysis was performed to predict the potential mechanism of JYHP in alleviating CDDP-induced myelosuppression. We obtained 202 targets with JYHP through the TCMSP database and 8439 targets related to myelosuppression (Supplemental Table 3). There were 168 genes simultaneously existing in both JYHP and myelosuppression related gene targets showing in Venny diagram (Figure 5A). Then we submitted these genes to STRING and Cytoscape 3.9.1 to construct the PPI network (Figure 5B). The network had 153 nodes and 1182 edges. We next analyzed the topological characteristics utilizing cytoHubba ranked by degree and betweenness centrality, we screened 10 key target genes (Table 1) which were identified as the potential targets of JYHP alleviating myelosuppression (Figure 5C).

Figure 5.

Network pharmacology analysis reasoning possible mechanism of JYHP alleviating myelosuppression. (A) The Venny diagram shows potential targets for JYHP in the treatment of myelosuppression. (B) PPI network of potential targets for JYHP in alleviating myelosuppression. The circle represents the target protein. The darker the color, the larger the diameter of the circle, representing a greater degree value. The lines represent the interaction relationship between proteins. (C) Hub genes for JYHP treating myelosuppression. (D) GO-BP, GO-CC, GO-MF term analysis of hub genes in Metascape. (E) KEGG pathway enrichment in Metascape.

Table 1.

Key target genes of JYHP alleviating myelosuppression screened by cytoHubba.

| Gene name | Betweenness centrality | Degree |

|---|---|---|

| AKT1 | 0.0911 | 61 |

| TP53 | 0.0947 | 61 |

| TNF | 0.0625 | 53 |

| IL6 | 0.0303 | 46 |

| RELA | 0.0345 | 43 |

| EGFR | 0.0373 | 43 |

| CASP3 | 0.0313 | 43 |

| MAPK1 | 0.0343 | 42 |

| MYC | 0.0299 | 41 |

| VEGFA | 0.0256 | 39 |

Prediction of Key Effects of JYHP in the Treatment of Myelosuppression

One hundred sixty-eight overlapping genes were subjected to GO enrichment and KEGG pathway enrichment analyses to investigate the biological activity and possible mechanisms of JYHP treating myelosuppression. GO analysis describes genes from 3 aspects of cellular component (CC), molecular function (MF), and biological process (BP). As shown in Figure 5D, the top 10 items with P-values for each category were visualized. In detail, GO-MF (blue histogram) was mainly enriched in DNA-binding transcription factor binding (GO: 0140297), transcription factor binding (GO: 0008134), and RNA polymerase II-specific DNA-binding transcription factor binding (GO: 0061629). Cyclin dependent protein kinase holoenzyme complex was enriched by GO-CC (pink histogram) which was critical regulators of cellular proliferation. 20 Membrane raft, membrane microdomain, and transcription regulator complex showed a large proportion in GO-BP (orange histogram). Meanwhile, KEGG enrichment analysis enriched 204 pathways, indicating the primary pathways included IL-17 signaling pathway (hsa04657), TNF signaling pathway (hsa04668), 21 PI3K-Akt signaling pathway (hsa04151), 22 mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signaling pathway23,24 (hsa04010) (Figure 5E). According to the above results, we had reasons to infer JYHP may alleviate myelosuppression involving proliferation and apoptosis of BM cells through multiple pathways.

Effect of JYHP Administration on Apoptosis and Cell Cycle of BM Cells

Based on the network pharmacology and enrichment analysis, we performed qPCR to explore the change in the 10 target genes (Table 1). The results displayed that there were no differences except CASP3 and MAPK1 (Figure 6). To further investigate whether JYHP comes into effect by influencing apoptosis and proliferation of BM cells, we evaluated the apoptosis rate of BM cells by flow cytometry and apoptosis related proteins through Western blotting.

Figure 6.

mRNA expression levels of target genes. Quantification of mRNA expression levels of AKT1 (A), TP53 (B), TNF (C), IL6 (D), RELA (E), EGFR (F), CASP3 (G), MAPK1 (H), MYC (I), VEGFA (J). Data were presented as the mean ± SEM. *P < .05, **P < .01, ***P < .001, ****P < .0001; n = 3.

As shown in Figure 7A and B, the sum of the events observed in quadrants 2 and 3 of flow cytometry indicated the number of cells undergoing apoptosis. The apoptosis percentage in the control group was 2.517 ± 0.29, which significantly increased in the CDDP group (5.32 ± 0.36, P < .01) while falling back to the control level after JYHP administration (2.65 ± 0.18, P < .01). Meanwhile, as Caspase3 25 was a frequently activated death protease, we estimated the ratio of Cleaved-Caspase3 and Caspase3 which manifested the same trend (Figure 7C and D). However, CDDP didn’t affect DNA synthesis based on the cell cycle results (Figure 7E and F).

Figure 7.

JYHP alleviated CDDP induced apoptosis of BM cells. (A) Apoptosis of BM cells was examined by flow cytometry analysis with Annexin V APC and 7-AAD double staining. (B) The apoptosis rate calculated as early apoptosis (Q3) plus late apoptosis (Q2) and shown in the histogram. (C/D) Apoptosis protein expression measured by Western blotting. (E/F) Cell cycle of each group was examined by flow cytometry analysis. Data were presented as the mean ± SEM. *P < .05, **P < .01, n = 3.

Effect of JYHP Alleviated CDDP-Induced Myelosuppression Through RAS/MEK/ERK Pathway

The KEGG pathway enrichment showed that the mechanism of JYHP in alleviating anemia was significantly related to multi-signal pathways. According to the results of RT-qPCR, we found the mRNA level of MAPK (Figure 6H) had significantly changed while TNF-α, AKT, TP53, IL6, EGFR, RELA, MYC, and VEGFA (Figure 6A-F, I, and J) had no change. We speculated that the MAPK signaling pathway may be the relevant pathway. From the results of Western blotting (Figure 8), we could see that compared with the normal control, the expression of RAS (P < .05), p-MEK/MEK (P < .01), p-ERK/ERK (P < .01) were all significantly increased after injecting CDDP. While compared with the CDDP group, p-MEK/MEK (P < .01), RAS (P < .05), and p-MEK/MEK (P < .05) all went down in JYHP group.

Figure 8.

Affect of JYHP administration on protein expression of RAS/MEK/ERK pathway. (A) Expressions of β-Actin, ERK, p-ERK, MEK, p-MEK measured by Western blotting. Quantification of protein expression levels of RAS (B), p-MEK/MEK (C), p-ERK/ERK (D) Data were presented as the mean ± SEM. *P < .05, **P < .01, n = 3.

Discussion

Overall, our studies established a CDDP-induced myelosuppression mice model then found JYHP administration had an effect on myeloprotection, and observed administration of JYHP after the initiation of chemotherapy rather than before would show higher efficacy. Then we verified JYHP exerted such an effect by inhibiting apoptosis of BM cells through RAS/MEK/ERK pathway by conducting a series of experiments.

The previous study used CTX to establish the model of chemotherapy-induced myelosuppression. 26 However, CDDP and other platinum-based drugs cause myelosuppression as their hematologic toxicities had been reported in clinical researches.27,28 We constructed a 10 day model on C57/BL mice by CDDP intraperitoneal injection. From the results of peripheral blood cell counts in the first part of the study, we found the timing of JYHP administration affected the effectiveness. Specifically, giving JYHP after injecting CDDP had a better effect than injecting it before Then, we evaluated the herbal pair compared with the single herbs. Peripheral blood cell counts directly reflected the hematopoietic function of bone marrow. WBC, PLT, NEUT, and RET parameters rose again after treating with JYHP which revealed JYHP decoction affected hematopoietic function recovery of bone marrow. RET is an indicator of the patient’s bone marrow response, so we calculated RET-related parameters (RET%, IRF, LFR, MFR, HFR) to assess the bone marrow hematopoietic function. 29 And IRF is an indicator that precedes other parameters, which could explain why RBC counts didn’t change; meanwhile IRF significance changed in these groups. 30

The spleen 31 is the largest lymphoid organ in the human body except for bone marrow, whose red pulp has the functions of blood storage, and removal of aging red blood cells. Based on the pathological staining, we speculated that there was extramedullary hematopoiesis in the spleen, which was a compensatory mechanism for hematopoiesis because of the inadequate hematopoiesis of bone marrow.32,33

In consideration of the complicated constituents in the JYHP decoction, we did UPLC/Q-TOF/MS to make the identification. Then after a literature search, we found partial components of JYHP alleviating myelosuppression caused by chemotherapy. Both quercetin and icaritin could decrease the hematopoietic inhibitory factors and increase the hematopoietic growth factors such as GFM-CS, G-CSF, TPO, and EPO to relieve myelosuppression.18,34 (+)-Catechin was capable of inhibiting the reduction of granulocytes and monocytes and enhancing the restoration of granulocytes and monocytes of the 5-FU-treated mice after 16 days. 35 And it also could alleviate cyclophosphamide-induced neutropenia. 36 However, our research found JYHP had a better effect than either of them from the number of peripheral blood leukocytes.

Hematopoietic stem cells (HSC) reside in bone marrow and differentiate into all kinds of blood cells.37,38 Bone marrow suppression consists of acute myelosuppression and residual bone marrow injury. 39 Apoptosis of HSC has been assumed to maintain hematopoietic homeostasis by regulating the amount of hematopoietic lineages. 40 CDDP was considered to be an inhibitor of DNA synthesis to exert anticancer activity, 1 while bone marrow is susceptible to CDPP for its high rate of proliferation.41,42 Lower concentrations of CDDP induced premature senescence and secondary nonstress-induced apoptosis which represent the primary response to DNA damage.43,44 In addition to the acute cytotoxicity, CDDP also caused irreversible chronic damage to the bone marrow. 45 Patients who have received prior regular CDDP therapy manifested bone marrow regeneration impairment. 46 Though some evidence demonstrated apoptosis was not the only way to the death of cells, the damage to cells caused by CDDP was indisputable.47-49 The results of pathology and flow cytometry proved this theory.

Combining the KEGG enrichment analysis with the qPCR results, we excluded IL-17 and TNF signaling pathways, and speculated that MAPK signaling pathways might participate in the apoptosis of BM cells caused by CDDP. MAPK is a group of protein kinases, widely known to regulate a variety of biological processes such as cell growth, differentiation, and apoptosis.23,24 The mammalian MAPK family includes 3 main pathways, namely extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK), p38, and c-JunNH2-terminal kinase (JNK).50,51 CDDP, as a DNA-damaging agent had been proven to induce the apoptotic function of RAS/RAF/ERK pathway.52,53 CDDP-induced ERK1/2 activation in ovarian carcinoma cell lines with dose- and time-dependence. 54 The activation of ERK motivated caspase-3 and caspase-9 then induced apoptosis in human bone marrow stromal cells. 55 The activation of ERK1/2 enhanced the cytotoxicity of CDDP in breast cancer cell lines. 56 Moreover, Icariin protected bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells by targeting the MAPK pathway. 57 However, our study utilized Western blotting and qPCR excluded PI3K-Akt pathway and TNF signal pathway then finally found JYHP could inhibit the RAS/MEK/ERK pathway to protect BM cells from apoptosis.

Conclusion

To sum up, our network pharmacology analysis and vivo studies demonstrated that JYHP attenuated CDDP-induced myelosuppression by the mechanisms associated with the reduction of bone marrow cells’ apoptosis through the RAS/MEK/ERK signal pathway. Moreover, the timing of the JYHP administration was vital. Specifically speaking, the effect of JYHP giving after the start of chemotherapy was better than before the chemotherapy, which means JYHP had a significant therapeutic effect rather than a preventative effect. Our research provided advice on the timing of clinical use of JXT and YYH in conjunction with chemotherapy.

However, other possible mechanisms by which JYHP alleviates CDDP-induced myelosuppression cannot be denied based on our network pharmacology enrichment. More experimental verification should be conducted in subsequent work.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-xlsx-1-ict-10.1177_15347354241237969 for Integration of Network Pharmacology and Experimental Validation to Explore Jixueteng - Yinyanghuo Herb Pair Alleviate Cisplatin-Induced Myelosuppression by Yi Liu, Shuying Dai, Yixiao Xu, Yuying Xiang, Yao Zhang, Zeting Xu, Lin Sun, Gao-chen-xi Zhang and Qijin Shu in Integrative Cancer Therapies

Supplemental material, sj-xlsx-2-ict-10.1177_15347354241237969 for Integration of Network Pharmacology and Experimental Validation to Explore Jixueteng - Yinyanghuo Herb Pair Alleviate Cisplatin-Induced Myelosuppression by Yi Liu, Shuying Dai, Yixiao Xu, Yuying Xiang, Yao Zhang, Zeting Xu, Lin Sun, Gao-chen-xi Zhang and Qijin Shu in Integrative Cancer Therapies

Supplemental material, sj-xlsx-3-ict-10.1177_15347354241237969 for Integration of Network Pharmacology and Experimental Validation to Explore Jixueteng - Yinyanghuo Herb Pair Alleviate Cisplatin-Induced Myelosuppression by Yi Liu, Shuying Dai, Yixiao Xu, Yuying Xiang, Yao Zhang, Zeting Xu, Lin Sun, Gao-chen-xi Zhang and Qijin Shu in Integrative Cancer Therapies

Footnotes

Abbreviations: JYHP, jixuetng and yinyanghuo herbal pair; UPLC-Q-TOF/MS, ultra-high performance liquid chromatography quadrupole time-of-flight mass spectrometry; CDDP, cisplatin; i.p., intraperitoneal; i.g., intragastric; BM, bone marrow; G-CSF, granulocyte colony-stimulating factor; GM-CSF, granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor; EPO, erythropoietin; TCM, Tradition Chinese medicine; qPCR, Quantitative real time polymerase chain reaction; JXT, Jixueteng; YYH, Yinyanghuo; OB, oral bioavailability; DL, drug-likeness; PPI, protein-protein interaction; RBC, red blood cell; HGB, hemoglobin; NEUT, neutrophil; PLT, platelet; RET, reticulocyte; WBC, white blood cell; LYM, lymphocyte; IRF, immature reticulocyte fraction; HE, hematoxylin-eosin staining; RIPA, radioimmunoprecipitation; PVDF, polyvinylidene fluoride; ECL, enhanced chemiluminescence; TIC, Typical total ion chromatogram; COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019.

Data Availability: All data needed to evaluate the conclusions in the paper are present in the paper and/or Supplementary Materials. Additional data related to this paper may be requested from the authors.

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by grants from the Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 81873243).

ORCID iDs: Yuying Xiang  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8991-7066

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8991-7066

Qijin Shu  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3460-8925

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3460-8925

Supplemental Material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- 1. Ghosh S. Cisplatin: the first metal based anticancer drug. Bioorg Chem. 2019;88:102925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Qi L, Luo Q, Zhang Y, et al. Advances in toxicological research of the anticancer drug cisplatin. Chem Res Toxicol. 2019;32:1469-1486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Barabas K, Milner R, Lurie D, Adin C. Cisplatin: a review of toxicities and therapeutic applications. Vet Comp Oncol. 2008;6:1-18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Sampi K, Sakurai M, Kumai R, et al. Combination of pipemidic acid, colistin sodium methanesulfonate and nystatin may be less effective than nystatin alone for prevention of infection during chemotherapy-induced granulocytopenia in acute leukemia. Med Oncol Tumor Pharmacother. 1989;6:291-296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Inaba H, Pei D, Wolf J, et al. Infection-related complications during treatment for childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Ann Oncol. 2017;28:386-392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Langer CJ, Gadgeel SM, Borghaei H, et al. Carboplatin and pemetrexed with or without pembrolizumab for advanced, non-squamous non-small-cell lung cancer: a randomised, phase 2 cohort of the open-label KEYNOTE-021 study. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17:1497-1508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Osanto S, Thijssen JC, Woldering VM, et al. Increased frequency of chromosomal damage in peripheral blood lymphocytes up to nine years following curative chemotherapy of patients with testicular carcinoma. Environ Mol Mutagen. 1991;17:71-78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Blijham GH. Prevention and treatment of organ toxicity during high-dose chemotherapy: an overview. Anticancer Drugs. 1993;4:527-533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Crawford J, Dale DC, Lyman GH. Chemotherapy-induced neutropenia: risks, consequences, and new directions for its management. Cancer. 2004;100:228-237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Herbst C, Naumann F, Kruse EB, et al. Prophylactic antibiotics or G-CSF for the prevention of infections and improvement of survival in cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;2009:CD007107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Arnberg H, Letocha H, Nõu F, Westlin JF, Nilsson S. GM-CSF in chemotherapy-induced febrile neutropenia–a double-blind randomized study. Anticancer Res. 1998;18:1255-1260. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Thomaidis T, Weinmann A, Sprinzl M, et al. Erythropoietin treatment in chemotherapy-induced anemia in previously untreated advanced esophagogastric cancer patients. Int J Clin Oncol. 2014;19:288-296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Zhang AW, Morjaria S, Kaltsas A, et al. The effect of neutropenia and filgrastim (G-CSF) on cancer patients with Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2022;74:567-574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Dasari S, Njiki S, Mbemi A, Yedjou CG, Tchounwou PB. Pharmacological effects of cisplatin combination with natural products in cancer chemotherapy. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23: 1532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Salehcheh M, Safari O, Khodayar MJ, Mojiri-Forushani H, Cheki M. The protective effect of herniarin on genotoxicity and apoptosis induced by cisplatin in bone marrow cells of rats. Drug Chem Toxicol. 2022;45:1470-1475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ke B, Shi L, Xu Z, et al. Flavored Guilu Erxian decoction inhibits the injury of human bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells induced by cisplatin. Cell Mol Biol. 2018;64:58-64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Guan Y, An P, Zhang Z, et al. Screening identifies the Chinese medicinal plant caulis spatholobi as an effective HAMP expression inhibitor. J Nutr. 2013;143:1061-1066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Sun C, Yang J, Pan L, et al. Improvement of icaritin on hematopoietic function in cyclophosphamide-induced myelosuppression mice. Immunopharmacol Immunotoxicol. 2018;40:25-34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Zheng J, Hu S, Wang J, et al. Icariin improves brain function decline in aging rats by enhancing neuronal autophagy through the AMPK/mTOR/ULK1 pathway. Pharm Biol. 2021;59:183-191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Cuomo ME, Platt GM, Pearl LH, Mittnacht S. Cyclin-cyclin-dependent kinase regulatory response is linked to substrate recognition. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:9713-9725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Rath PC, Aggarwal BB. TNF-induced signaling in apoptosis. J Clin Immunol. 1999;19:350-364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Chang F, Lee JT, Navolanic PM, et al. Involvement of PI3K/Akt pathway in cell cycle progression, apoptosis, and neoplastic transformation: a target for cancer chemotherapy. Leukemia. 2003;17:590-603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Yue J, López JM. Understanding MAPK signaling pathways in apoptosis. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21:2346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Yong HY, Koh MS, Moon A. The p38 MAPK inhibitors for the treatment of inflammatory diseases and cancer. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2009;18:1893-1905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Porter AG, Jänicke RU. Emerging roles of caspase-3 in apoptosis. Cell Death Differ. 1999;6:99-104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Yeager AM, Levin FC, Levin J. Effects of cyclophosphamide on murine bone marrow and splenic megakaryocyte-CFC, granulocyte-macrophage-CFC, and peripheral blood cell levels. J Cell Physiol. 1982;112:222-228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kwon JH, Kim JH, Lee JA, et al. Phase II study with fractionated schedule of docetaxel and cisplatin in patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2010;66:889-897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Iwasaki Y, Ohsugi S, Natsuhara A, et al. Phase I/II trial of biweekly docetaxel and cisplatin with concurrent thoracic radiation for stage III non-small-cell lung cancer. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2006;58:735-741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Piva E, Brugnara C, Spolaore F, Plebani M. Clinical utility of reticulocyte parameters. Clin Lab Med. 2015;35:133-163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Noronha JF, De Souza CA, Vigorito AC, et al. Immature reticulocytes as an early predictor of engraftment in autologous and allogeneic bone marrow transplantation. Clin Lab Haematol. 2003;25:47-54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Cesta MF. Normal structure, function, and histology of the spleen. Toxicol Pathol. 2006;34:455-465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Orphanidou-Vlachou E, Tziakouri-Shiakalli C, Georgiades CS. Extramedullary hemopoiesis. Semin Ultrasound CT MR. 2014;35:255-262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Short C, Lim HK, Tan J, O’Neill HC. Targeting the spleen as an alternative site for hematopoiesis. Bioessays. 2019;41: 1800234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Chuang CH, Lin YC, Yang J, Chan ST, Yeh SL. Quercetin supplementation attenuates cisplatin induced myelosuppression in mice through regulation of hematopoietic growth factors and hematopoietic inhibitory factors. J Nutr Biochem. 2022;110: 109149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Takano F, Tanaka T, Aoi J, Yahagi N, Fushiya S. Protective effect of (+)-catechin against 5-fluorouracil-induced myelosuppression in mice. Toxicology. 2004;201:133-142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Ganeshpurkar A, Saluja AK. Protective effect of catechin on humoral and cell mediated immunity in rat model. Int Immunopharmacol. 2018;54:261-266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Kandarakov O, Belyavsky A, Semenova E. Bone marrow niches of hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23:4462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Höfer T, Rodewald HR. Differentiation-based model of hematopoietic stem cell functions and lineage pathways. Blood. 2018;132:1106-1113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Wang Y, Probin V, Zhou D. Cancer therapy-induced residual bone marrow injury-mechanisms of induction and implication for therapy. Curr Cancer Ther Rev. 2006;2:271-279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Wickremasinghe RG, Hoffbrand AV. Biochemical and genetic control of apoptosis: relevance to normal hematopoiesis and hematological malignancies. Blood. 1999;93:3587-3600. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Cepeda V, Fuertes MA, Castilla J, et al. Biochemical mechanisms of cisplatin cytotoxicity. Anticancer Agents Med Chem. 2007;7:3-18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Rebillard A, Lagadic-Gossmann D, Dimanche-Boitrel MT. Cisplatin cytotoxicity: DNA and plasma membrane targets. Curr Med Chem. 2008;15:2656-2663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Mauch P, Constine L, Greenberger J, et al. Hematopoietic stem cell compartment: acute and late effects of radiation therapy and chemotherapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1995;31:1319-1339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Galotto M, Berisso G, Delfino L, et al. Stromal damage as consequence of high-dose chemo/radiotherapy in bone marrow transplant recipients. Exp Hematol. 1999;27:1460-1466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Kemp K, Morse R, Wexler S, et al. Chemotherapy-induced mesenchymal stem cell damage in patients with hematological malignancy. Ann Hematol. 2010;89:701-713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Lucas D, Scheiermann C, Chow A, et al. Chemotherapy-induced bone marrow nerve injury impairs hematopoietic regeneration. Nat Med. 2013;19:695-703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Gonzalez VM, Fuertes MA, Alonso C, Perez JM. Is cisplatin-induced cell death always produced by apoptosis? Mol Pharmacol. 2001;59:657-663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Berndtsson M, Hägg M, Panaretakis T, et al. Acute apoptosis by cisplatin requires induction of reactive oxygen species but is not associated with damage to nuclear DNA. Int J Cancer. 2007;120:175-180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Fuertes MA, Castilla J, Alonso C, Pérez JM. Cisplatin biochemical mechanism of action: from cytotoxicity to induction of cell death through interconnections between apoptotic and necrotic pathways. Curr Med Chem. 2003;10:257-266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Schaeffer HJ, Weber MJ. Mitogen-activated protein kinases: specific messages from ubiquitous messengers. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:2435-2444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Cuadrado A, Nebreda AR. Mechanisms and functions of p38 MAPK signalling. Biochem J. 2010;429:403-417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Wang X, Martindale JL, Holbrook NJ. Requirement for ERK activation in cisplatin-induced apoptosis. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:39435-39443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Woessmann W, Chen X, Borkhardt A. Ras-mediated activation of ERK by cisplatin induces cell death independently of p53 in osteosarcoma and neuroblastoma cell lines. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2002;50:397-404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Persons DL, Yazlovitskaya EM, Cui W, Pelling JC. Cisplatin-induced activation of mitogen-activated protein kinases in ovarian carcinoma cells: inhibition of extracellular signal-regulated kinase activity increases sensitivity to cisplatin. Clin Cancer Res. 1999;5:1007-1014. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Kim GS, Hong JS, Kim SW, et al. Leptin induces apoptosis via ERK/cPLA2/cytochrome c pathway in human bone marrow stromal cells. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:21920-21929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Ko H, Lee M, Cha E, et al. Eribulin mesylate improves cisplatin-induced cytotoxicity of triple-negative breast cancer by extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 activation. Medicina. 2022;58:547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Deng S, Zeng Y, Xiang J, Lin S, Shen J. Icariin protects bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells in aplastic anemia by targeting MAPK pathway. Mol Biol Rep. 2022;49:8317-8324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, sj-xlsx-1-ict-10.1177_15347354241237969 for Integration of Network Pharmacology and Experimental Validation to Explore Jixueteng - Yinyanghuo Herb Pair Alleviate Cisplatin-Induced Myelosuppression by Yi Liu, Shuying Dai, Yixiao Xu, Yuying Xiang, Yao Zhang, Zeting Xu, Lin Sun, Gao-chen-xi Zhang and Qijin Shu in Integrative Cancer Therapies

Supplemental material, sj-xlsx-2-ict-10.1177_15347354241237969 for Integration of Network Pharmacology and Experimental Validation to Explore Jixueteng - Yinyanghuo Herb Pair Alleviate Cisplatin-Induced Myelosuppression by Yi Liu, Shuying Dai, Yixiao Xu, Yuying Xiang, Yao Zhang, Zeting Xu, Lin Sun, Gao-chen-xi Zhang and Qijin Shu in Integrative Cancer Therapies

Supplemental material, sj-xlsx-3-ict-10.1177_15347354241237969 for Integration of Network Pharmacology and Experimental Validation to Explore Jixueteng - Yinyanghuo Herb Pair Alleviate Cisplatin-Induced Myelosuppression by Yi Liu, Shuying Dai, Yixiao Xu, Yuying Xiang, Yao Zhang, Zeting Xu, Lin Sun, Gao-chen-xi Zhang and Qijin Shu in Integrative Cancer Therapies