Abstract

Infective endocarditis (IE) is a condition with low prevalence but high mortality rates within intensive care units. Microbiologically, most cases are attributed to Gram-positive cocci, while Gram-negative bacilli are less commonly involved. This case report describes a patient with IE caused by Citrobacter koseri (C. koseri) with secondary bacteremia due to blunt testicular trauma and epididymitis. We conducted a review of the literature to assess the clinical and associated risk factors of this underreported condition. Elderly and urinary tract infections could be associated with this entity. Cefazolin was used as the final targeted treatment. The use of precision medicine in IE is required for specific interventions.

Keywords: case report, Citrobacter koseri, epididymitis, infective endocarditis, risk factors

Plain language summary

Infection of the heart valve from testicular injury: a case study and review of medical literature

Infective endocarditis (IE) is a serious but rare infection that can lead to death, especially in intensive care units. Typically, it’s caused by certain types of bacteria, but our case study focuses on a patient whose IE was caused by a less common bacterium called Citrobacter koseri (C. koseri). This infection occurred after the patient experienced blunt trauma to the testicles, leading to a bloodstream infection. We looked at other similar cases in medical literature and found that older age and urinary tract infections might increase the risk of this type of IE. In this case, IE caused by this unusual bacteria was treated with cefazolin.

Introduction

Infective endocarditis (IE) is a disease described by Sir William Osler in the 1890s. Initially, it was suggested as a unified theory in which vulnerable patients developed ‘fungal’ growth in their valves which were later ‘transferred to distant parts of the body’. 1 This condition might be life-threatening, with an estimated incidence of 1.5–11.6 cases per 100,000 population and a mortality rate of approximately 25%, prosthetic valves and cardiac devices (pacemakers, implantable cardioverter-defibrillators, etc.) are associated with a greater incidence of IE. 2 Rheumatic heart disease also has been described as a significant risk factor for IE, and the mitral valve is the most involved. 3

In most of IE cases, Gram-positive bacteria, particularly Streptococcus spp. and Staphylococcus spp., are commonly isolated. However, etiology varies depending on the local epidemiology. Infections by non-influenzae Haemophilus, Aggregatibacter, Cardiobacterium, Eikenella, and Kingella (HACEK) Gram-negative bacilli (NH-GNB), have been reported in approximately 2% of the IE cases. The most frequently found GNB include Escherichia coli, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Klebsiella pneumoniae, mainly related to healthcare settings. 4 Citrobacter koseri-related IE cases are quite infrequently reported,5–12 and so far, no clear associated factors have been described. We present a case report of IE attributed to C. koseri in an elderly patient with no comorbidities after blunt testicular trauma.

Case presentation

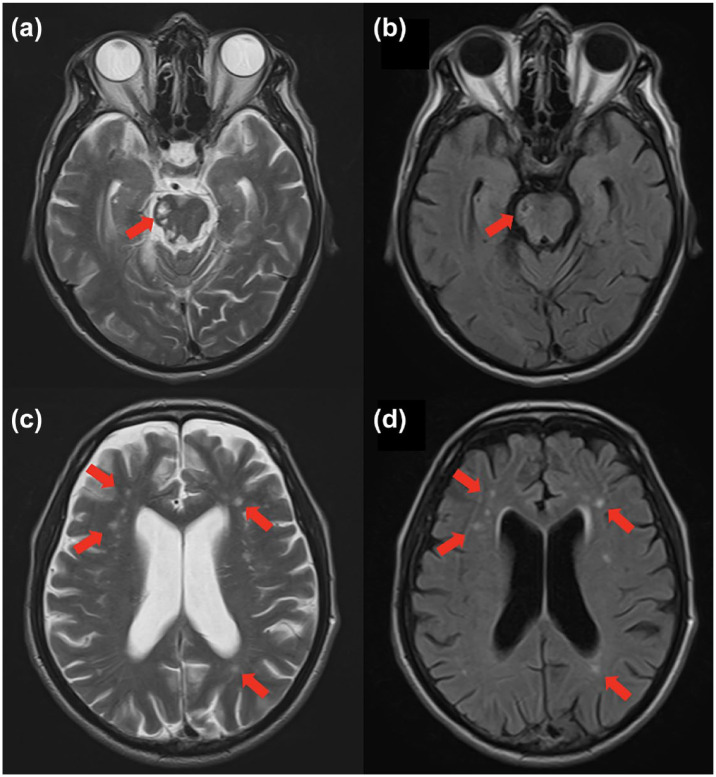

An 81-year-old male patient was admitted with urinary symptoms following moderate blunt testicular trauma with a small lawnmower during gardening activities. His background history included arterial hypertension. The clinical diagnosis included right epididymitis and an ipsilateral testicular abscess. After 3 days of general hospitalization and an unfavorable evolution, blood cultures were drawn, and C. koseri was identified by matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization-time of flight mass spectrometry from three sets of blood cultures drawn from three separate venipuncture sites. On intensive care unit (ICU) admission, vital signs showed a blood pressure of 88/52 mmHg, a heart rate of 117 beats per minute, a respiratory rate of 23 breaths per minute, and a temperature of 36°C. He developed multiple organ dysfunction syndrome, requiring vasopressors and ventilatory support. Multiple septic embolisms were detected in the brain (Figure 1), lungs, and lower limbs; therefore, IE was suspected. A transesophageal echocardiogram was performed, revealing two masses attached to the atrial aspect of the mitral valve. One mass measured 19 mm × 8 mm, and the other measured 13 mm × 9 mm, causing severe mitral regurgitation (Figure 2). He received initial empiric therapy with meropenem and, later, cefazolin as a definitive treatment after a susceptibility test was performed. Subsequently, the patient underwent a biological mitral valve replacement due to severe symptomatic valvular dysfunction, with evidence of IE documented by direct inspection during heart surgery. The patient received cefazolin for 6 weeks, with complete clinical recovery and no neurological deficit.

Figure 1.

Cerebral MRI. (a, b) T2 weighted and FLAIR – right pontine infarction (red arrow). (c, d) T2 weighted and FLAIR – subcortical and deep white matter hyperintensities compatible with multiple septic embolisms (red arrows).

FLAIR, fluid attenuation inversion recovery; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging.

Figure 2.

Transesophageal echocardiogram. (a, b) Two masses, one measuring 19 mm × 8 mm and the other 13 mm × 9 mm, are attached to the atrial wall of the mitral valve (red arrows). (c) Three-dimensional image of the mitral valve mass (red arrow). (d) Severe mitral valve insufficiency (yellow arrow).

Discussion

The genus Citrobacter includes 11 species, more frequently isolated species are as follows: Citrobacter freundii, C. koseri, and Citrobacter amalonaticus. The name ‘Citrobacter’ is derived from the fact that citrate serves as the exclusive carbon source for this bacterium. Intrinsic resistance to ampicillin and ticarcillin has been reported, with in vitro sensitivity to ciprofloxacin; carbapenem; first-, second-, and third-generation cephalosporins; piperacillin/tazobactam; trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole; and aminoglycosides. 13 Citrobacter koseri (which used to be called Citrobacter diversus) is a Gram-negative aerobic bacillus, widely distributed and infrequently induces infections in humans. This microorganism has been detected in both the genitourinary and gastrointestinal systems of animals and humans, primarily as part of the gut microbiota. It is classified as an opportunistic bacterium, commonly observed in individuals with weakened immune systems, particularly immunosuppressed patients, and infants.14,15 Urinary infections account for 46% of the reported cases, followed by respiratory tract infections (16%) and bacteremia (16%). 15

IE caused by NH-GNB is a condition with low prevalence; the 2018 study by Falcon et al. 4 that explored risk factors and outcomes of IE associated with NH-GNB showed that patients with implantable cardiac devices, urinary tract infections, and immunosuppression were at higher risk of IE, with a prevalence of NH-GNB of 3.4% (58/1722 endocarditis patients), being C. koseri responsible for 3 of 58 patients in this cohort.

The first reported case of IE caused by C. koseri was documented in 1977 in a patient with a history of aortic valve replacement. 5 Subsequently, only a limited number of cases have been described in the literature (Table 1), most of them in patients with immunosuppression, hemodialysis, intravenous drug users, male gender, and recurrent urinary tract infections. Among the eight reported cases, 88.8% involved male patients, ranging in age from 25 to 81 years.

Table 1.

Summary of prior cases of endocarditis caused by C. koseri.

| Case | Author | Year | Age/gender | Risk factor | Treatment | Prognosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | MacCulloch et al. | 1977 | 43/male | Not described | Cephalothin/gentamicin and aortic valve replacement. | Alive |

| 2 | Tellez et al. | 2000 | 51/male | Intravenous drug user | Ceftriaxone/gentamicin/vancomycin | Alive |

| 3 | Aubron et al. | 2006 | 58/male | Chronic bronchitis | Cefotaxime/pefloxacin mitral valve replacement | Dead |

| 4 | Dzeing-Ella et al. | 2009 | 30/male | No comorbidities | Ceftriaxone and amikacin | Alive |

| 5 | Figueroa et al. | 2009 | 25/male | Hemodialysis | Ciprofloxacin | Alive |

| 6 | Raval et al. | 2014 | 43/male | Intravenous drug user Hepatitis C | Ticarcillin/clavulanate | Alive |

| 7 | Takahashi et al. | 2014 | 80/female | Recurrent pyelonephritis | Cefazolin/gentamicin mitral valve replacement | Alive |

| 8 | Al-Alwan et al. | 2022 | 67/male | Type 2 diabetes, chronic kidney disease, atrial fibrillation, septic shock of urinary origin | Ceftriaxone/cefuroxime | Alive |

| 9 | Casallas et al. | 2023 | 81/male | Testicular trauma with epididymitis | Cefazolin and mitral valve replacement | Alive |

In this specific case, the absence of comorbidities and the aforementioned risk factors should be considered. However, the presence of a non-penetrating testicular wound with epididymitis and secondary abscess formation in an elderly and frailty patient were the unique factors associated with bacteremia and IE of the mitral valve. This observation is consistent with findings from other case reports, underscoring the heightened risk of bacteremia leading to IE caused by NH-GNB in susceptible individuals with genitourinary tract infections.

Conclusion

IE caused by C. koseri is very unusual. A comprehensive analysis of the literature revealed a total of nine documented cases worldwide, urinary tract infections could be a potential risk factor for this entity, despite the lack of any strong detectable common risk factors among them. In the future, a characterization of host and microorganisms associated with the development of IE by NH-BGN, with the use of precision medicine, is required. Such information can guide the development of specific interventions and the identification of potential risk factors.

Acknowledgments

None.

Footnotes

ORCID iD: Julian Orlando Casallas-Barrera  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8511-7237

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8511-7237

Contributor Information

Julian Orlando Casallas-Barrera, Department of Critical Care Medicine, Fundación Clínica Shaio, Dg. 115a #70c–75, Bogotá 111111, Colombia.

Claudia Marcela Poveda-Henao, Cardiology and Critical Care Department, Fundación Clínica Shaio, Bogotá, Colombia.

Karen Andrea Mantilla-Viviescas, Critical Care Resident, Universidad de La Sabana, Chía, Colombia.

Edwin Silva-Monsalve, Division of Infectious Disease, Fundación Clínica Shaio, Bogotá, Colombia.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate: This study adhered to ethical requirements. It was approved by the Ethics committee in research of the Fundacion Abood Shaio (ID approval 354 from 8 February 2023).

Consent for publication: Written informed consent for publication of the clinical details and clinical images was obtained from the patient.

Author contributions: Julian Orlando Casallas-Barrera: Conceptualization; Investigation; Methodology; Validation; Writing – original draft; Writing – review & editing.

Claudia Marcela Poveda-Henao: Data curation; Formal analysis; Methodology; Writing – original draft; Writing – review & editing.

Karen Andrea Mantilla-Viviescas: Formal analysis; Investigation; Writing – original draft.

Edwin Silva-Monsalve: Conceptualization; Formal analysis; Investigation; Supervision; Writing – review & editing.

Funding: The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Availability of data and materials: The authors confirm that clinical data are available from the corresponding author, upon reasonable request.

References

- 1. Osler W. The Gulstonian Lectures, on malignant endocarditis. Br Med J 1885; 1: 577–579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Murdoch DR, Corey GR, Hoen B, et al. Clinical presentation, etiology, and outcome of infective endocarditis in the 21st century: the International Collaboration on Endocarditis-Prospective Cohort study. Arch Intern Med 2009; 169: 463–473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Rabinovich S, Evans J, Smith IM, et al. A long-term view of bacterial endocarditis. 337 cases 1924 to 1963. Ann Intern Med 1965; 63: 185–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Falcone M, Tiseo G, Durante-Mangoni E, et al. Risk factors and outcomes of endocarditis due to non-HACEK Gram-negative bacilli: data from the prospective multicenter Italian Endocarditis Study Cohort. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2018; 62: e02208–e02217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. MacCulloch D, Menzies R, Cornere BM. Endocarditis due to Citrobacter diversus developing resistance to cephalothin. N Z Med J 1977; 85: 182–183. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Tellez I, Chrysant GS, Omer I, et al. Citrobacter diversus endocarditis. Am J Med Sci 2000; 320: 408–410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Aubron C, Charpentier J, Trouillet JL, et al. Native-valve infective endocarditis caused by Enterobacteriaceae: report on 9 cases and literature review. Scand J Infect Dis 2006; 38: 873–881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Dzeing-Ella A, Szwebel TA, Loubinoux J, et al. Infective endocarditis due to Citrobacter koseri in an immunocompetent adult. J Clin Microbiol 2009; 47: 4185–4186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Figueroa CE, Smith PW. Citrobacter koseri endocarditis in a patient undergoing hemodialysis: case report and review of the literature. Infect Dis Clin Pract 2009; 17: 198–200. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Raval J, Nagaraja V, Poojara L, et al. Citrobacter koseri native valve endocarditis: a case report and review of the literature. J Indian Coll Cardiol 2014; 4: 246–248. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Takahashi K, Uno S, Sada R. An 80-year-old woman surgically treated for native valve infective endocarditis caused by Citrobacter koseri. J Formos Med Assoc 2017; 116: 129–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Al-Alwan A, Sirpal V, Yarrarapu S, et al. Citrobacter koseri infective endocarditis with septic endophthalmitis. Infections and infectious complications in the ICU/Thematic Poster Session. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2022; 205: A1644. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Deveci A, Coban AY. Optimum management of Citrobacter koseri infection. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther 2014; 12: 1137–1142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Terence ID. The role of Citrobacter in clinical disease of children: review. Clin Infect Dis 1999; 28: 384–394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Mohanty S, Singhal R, Sood S, et al. Citrobacte infections in a tertiary care hospital in Northern India. J Infect 2007; 54: 58–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]