Abstract

Telepsychiatry formed part of the Australian mental health response to COVID-19, but relevant reviews pre- and post-pandemic are sparse. This scoping review aimed to map the literature on telepsychiatry in Australia and identify key research priorities. We searched databases (Medline, PubMed, PsycINFO, Scopus, Web of Science, EBSCO Psychology & Behavioral Sciences Collection, Proquest databases, and Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials) and reference lists from January 1990 to December 2022. Keywords included telepsychiatry, videoconferencing, telephone consultation, psychiatry, mental health, and Australia. Two reviewers independently screened titles, abstracts, and full texts. We identified 96 publications, one-third of which appeared since 2020. Extracted data included article types, service types, usage levels, outcome measures, perceptions, and research gaps. Most publications were quantitative studies (n = 43) and narrative reports of services (n = 17). Seventy-six papers reported mostly publicly established services. Videoconferencing alone was the most common mode of telepsychiatry. There was increased use over time, with the emergence of metropolitan telepsychiatry during the pandemic. Few papers used validated outcome measures (n = 5) or conducted economic evaluations (n = 4). Content analysis of the papers identified perceptions of patient (and caregiver) benefits, clinical care, service sustainability, and technology capability/capacity. Benefits such as convenience and cost-saving, clinical care issues, and implementation challenges were mentioned. Research gaps in patient perspectives, outcomes, clinical practice, health economics, usage patterns, and technological issues were identified. There is consistent interest in, and growth of, telepsychiatry in Australia. The identified perception themes might serve as a framework for future research on user perspectives and service integration. Other research areas include usage trends, outcome measures, and economic evaluation.

Keywords: Australia, mental health services, remote consultation, telemental health, telepsychiatry, videoconferencing

What do we already know about this topic?

Telepsychiatry existed in Australia for decades and developed rapidly since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic.

How does your research contribute to the field?

This scoping review is the most comprehensive review of literature on telepsychiatry in Australia to date, offering an overview of telepsychiatry development in the country and providing the background for further research.

What are your research’s implications toward theory, practice, or policy?

The findings of this scoping review can serve as a useful reference for policymakers and clinicians in Australia and other countries, especially on the use of telepsychiatry to improve access in rural and remote areas and funding for large-scale telepsychiatry services.

Introduction

Telehealth involves the use of information technology (IT) to deliver healthcare services, including clinical assessment, care, and health-related support across geographical distances.1 -3 Telehealth provided by psychiatrists is known as telepsychiatry.4,5 Telepsychiatry may involve synchronous methods (telephone, videoconferencing) or asynchronous methods (e-mail, web-based systems, and mobile applications). Most commonly, telepsychiatry denotes 2-way, live psychiatric consultations. 6

Telepsychiatry began in the 1950s as a means to expand clinical services to distant geographical areas. 4 In the 1960s, several services were implemented in the United States. 7 In the following decades, various telepsychiatry programs developed globally. By 1998, an international survey identified 29 programs, with 25 in the United States, 1 in Canada, 1 in England, 1 in Norway, and 1 in Australia. 7 The first Australian telepsychiatry service began in 1993. 8 By 2001, there were 36 telepsychiatry programs across Australia. 9 Facilitated by advancements in communication technologies that enable high-quality videoconferencing at reduced costs, the COVID-19 pandemic greatly stimulated the uptake of telepsychiatry. 10 A global survey found that more than 90% of mental health professionals from over 100 countries engaged in telehealth. 11 Many countries also made regulatory and funding changes to allow tele-psychiatric care. 12

Australia faces substantial challenges in psychiatric care provision due to the vastness of the continent, the relatively small population, the remoteness of many communities, as well as the reliance upon a national telecommunications network to maintain connectivity and provides healthcare, government and other public services, and business. The early literature on Australian telepsychiatry services emerged in the 1990s.13 -15 Subsequently, telepsychiatry has grown across Australia. 9 Similar to other telehealth services, telepsychiatry mostly involved videoconferencing between hospital-based clinicians and patients in rural and remote areas, and it was aided by the improvement in broadband capacity through the construction of the National Broadband Network (NBN). 16 During the COVID-19 pandemic, telepsychiatry formed part of the nation’s mental health response as the Australian Government expanded telepsychiatry availability in the Medicare Benefits Schedule (MBS) in early 2020. 17 Since then, rapid uptake of telepsychiatry has been observed.18 -20

Several systematic reviews and meta-analyses have examined the outcomes, effectiveness, and cost-effectiveness of telepsychiatry in an international context.21 -23 However, searches of the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, PROSPERO International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews, and Joanna Briggs Institute Systematic Review Register in December 2022 found no relevant Australia-specific review. Many new research findings on service usage and other aspects of telepsychiatry in Australia have emerged during the pandemic. Although there have been opinion pieces, speculative articles, and scholarly discussions on its ongoing role, a full review of the current evidence base is lacking.

Unlike systematic reviews that tend to focus on the effectiveness of interventions, a scoping review allows a broader approach to answering a wider range of research questions. 24 It can ascertain the extent of, and approach(es) used, in the current research on a given topic24,25 concerning a specific context or location, such as Australia. 26 Adopting a country-specific approach is appropriate, since understanding a country’s particular circumstances is crucial in the evaluation of mental health policies and plans. 27 The objective of this scoping review was to systematically map and explore the existing literature on telepsychiatry in Australia. It sought to identify key research priorities to advance relevant policy and practice.

The research questions (RQs) were:

RQ1. What were the types of telepsychiatry research conducted in Australia?

RQ2. What types of telepsychiatry services were implemented in Australia?

RQ3. What was known about the level of usage of telepsychiatry in Australia?

RQ4. What were the reported quantitative outcome measures used?

RQ5. What were the reported perceptions about telepsychiatry in Australia?

RQ6. What were the research gaps for telepsychiatry in Australia in the literature?

Materials and Methods

This scoping review was conducted according to the methodology described by Arksey and O’Malley, 25 Levac et al, 28 Peters et al, 24 Peters et al, 29 and the Joanna Briggs Institute Reviewer’s Manual. 30 The review protocol was pre-registered on the Open Science Framework (https://osf.io/mfpsv). It is reported according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-Scr, see Supplemental material 1). 31

Inclusion Criteria

Based on the Population, Concept, and Context mnemonic for scoping reviews, 30 we included sources that focused on:

- Telepsychiatry consultation in Australia.

- Consultation was defined as a session between a treating psychiatrist and a patient, which ordinarily involves history taking, assessment of symptoms, mental state examination, possibly physical examination, case formulation, discussion of diagnoses and treatment, decision-making related to treatment, and interventions.

- The consultation could be either general or focused only on specific assessments or therapeutic procedures.

- Psychiatrists (private or public sector) working solo, as part of a mental healthcare team, or in shared care with local clinicians (eg, general practitioners).

- Psychiatry trainees were included.

Synchronous consultations by videoconferencing and/or telephone.

Studies of general telemental health were included if specific results and information about telepsychiatry could be extracted.

- Local, regional, or national telepsychiatry services in Australia.

- Reports of multinational studies involving Australia were included if specific Australian information could be extracted.

Exclusion Criteria

Telemental health consultations by other mental health professionals, such as clinical psychologists, counselors, mental health nurses, social workers, or occupational therapists without the involvement of a psychiatrist.

Videoconferencing for psychiatry training and education or administrative purposes without involving direct clinical assessment and/or care of patients.

Other eHealth or mHealth resources or interventions, such as helplines, emails, text messages, websites, mobile apps, social media, chatbots, virtual reality, and gaming for mental health promotion and prevention, mental health literacy and education, screening, self-monitoring, automated assessments or diagnostics, self-help, online peer groups, and computerized or internet-delivered therapies.

Information Sources

The following databases were included: MEDLINE, PubMed, PsycINFO, Scopus, Web of Science, EBSCO Psychology & Behavioral Sciences Collection, Proquest databases, and Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL).

The following limits were imposed on the sources:

Human studies.

Peer-reviewed journals.

Research articles or letters/correspondences, including quantitative, qualitative, and mixed-method studies.

Case reports, reviews, recommendations, guidelines, editorials, commentaries, and opinions were also included.

Date of publication: January 1990 to December 2022. The start-year of 1990 was chosen given the expansion and wider application of telepsychiatry that has occurred during the last 3 decades 4 and lack of comparability of older studies due to technological changes.

English language articles

Search

A 3-step search strategy was adopted. 30 The initial search strategy was developed by 1 researcher (LW) in consultation with the other research team members. LW conducted a preliminary limited search of 2 online databases, MEDLINE and PsycINFO. The text words in the title and abstract of retrieved papers and their index terms were studied. In collaboration with 2 librarians, a second search with a refined search strategy incorporating identified keywords and index terms was undertaken across all databases.

The following is the final full search strategy for MEDLINE:

exp Telemedicine/ or exp Videoconferencing/ or exp Remote Consultation/

(Telepsychiatry or Telehealth or Telecare or Teleconsultation or “Telemental health” or “Tele-mental health”).tw.

(“Telephone consult*” or “Phone consult*” or “Video consult*”).tw.

(“Video conferencing” or Teleconferencing).tw.

(e-health or ehealth).tw.

or/1 to 5

exp Psychiatry/ or exp Mental Health/

exp Mental disorders/

Mental health services/ or Psychiatric department, hospital/ or Hospitals, psychiatric/ or Community mental health services/

(“Psychiatric disorder*” or “Depressive disorder*” or “Anxiety disorder*” or Schizophrenia or “Psychotic disorder*” or “Bipolar disorder*” or “Personality disorder*”).tw.

Psychiatrist*.tw.

“Psychiatric patient*.”tw.

(“Psychiatric service*” or “Psychiatric care” or “Mental health care” or “Mental healthcare”).tw.

or/7 to 13

Australia/ or New South Wales/ or Queensland/ or South Australia/ or Tasmania/ or Victoria/ or Western Australia/ or Australian Capital Territory/ or Northern Territory/

(Australia or “New South Wales” or Queensland or “South Australia” or Tasmania or Victoria or “Western Australia” or “Australian Capital Territory” or “Jervis Bay Territory” or “Northern Territory”).tw.

15 or 16

6 and 14 and 17

limit 18 to (English language and humans and yr = “1990 -Current”)

Search strategies for other databases are listed in Supplemental material 2.

The last search was executed on 17 January 2023. The PRESS Peer Review of Electronic Search Strategies: 2015 Guideline Statement guided this process. 32 Finally, the reference lists of identified articles were searched.

Selection Process

All search results were exported to EndNote (Clarivate Analytics, PA, USA). Duplicates were removed. The Rayyan platform 33 was used for title and abstract screening followed by a full-text screening. Two reviewers (LW and JL) independently screened the titles and abstracts. Disagreements were resolved by conferencing. When a consensus was not reached, a third reviewer (PM) was consulted. The selected papers were read in full, and any disagreements were settled through the same processes.

Data Charting Process

A standardized data-charting form was developed and trialed with the initial 3 papers to ensure all relevant results were extracted. A reviewer (LW) extracted data from each evidence source. Other research team members (JL, PM, and RR) reviewed the extraction to ensure its accuracy and completeness. 34 Care was taken to avoid redundant extraction. Data from a secondary source (eg, a review) were not extracted when the primary source was already included. Data from multiple sources on the same service were extracted if they reported different periods or aspects of the service.

Data Items

The data items encompassed metadata, methodology and findings of the publications, including article types, types of services, usage levels, outcome measures, perceptions, and research gaps. See Supplemental material 3 for the data charting form containing all data items and the guidance for extraction.

Critical Appraisal of Individual Sources of Evidence

This is an optional stage for scoping reviews. 31 Since there was a wide range of study designs and methodologies, an assessment of the risk of bias or methodological limitations was not performed. 29

Synthesis and Presentation of Results

Analysis and presentation of results were guided by the Recommendations for the Extraction, Analysis, and Presentation of Results in Scoping Reviews. 34 Descriptive information was analyzed using Microsoft Excel (Redmond, Washington, USA). Key information was grouped and presented in a narrative format according to the research questions. For the perceptions qualitative data, basic content analysis29,35 was employed using NVivo 12 Pro (QSR International, United Kingdom). A deductive approach was adopted. 35 The categorization matrix for coding was based on the groupings of criteria and measures for the key dimensions of the Framework for Telehealth Evaluation in Australia (Supplemental material 4). 36 The matrix was unconstrained, with new categories created to describe the data as necessary. Researchers reviewed, discussed, refined, and finalized the themes. For the qualitative data of research gaps, inductive content analysis was used. 35

Results

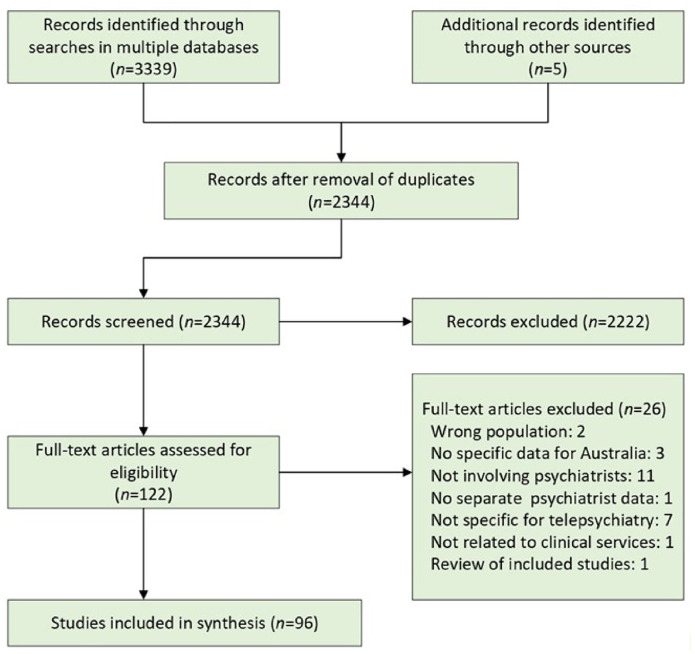

We identified 3339 searches from the databases, of which 1000 were duplicates. Five additional articles were identified through a hand search of reference lists. The title and abstract screening identified 122 publications. Full-text screening resulted in 96 eligible publications (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram of systematic search and study selection.

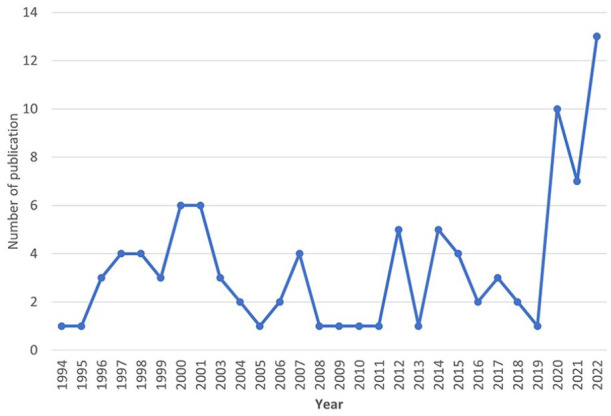

The articles were published in 29 different journals, the 3 most frequent being the Journal of Telemedicine and Telecare (n = 31, 32.3%), Australasian Psychiatry (n = 26, 27.1%), and the Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry (n = 9, 9.4%). Of note, 31.3% of all articles were published since 2020, largely during the COVID-19 pandemic (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Number of accepted articles on telepsychiatry in Australia per year from 1994 to 2022.

The key findings of this scoping review are summarized in Table 1. Detailed results are presented in the following subsections for the research questions. The full extraction of characteristics and results of sources of evidence is available in Supplemental material 5.

Table 1.

Key Findings of the Scoping Review According to the Research Questions.

| Research question | Key findings |

|---|---|

| RQ1. What were the types of telepsychiatry research conducted in Australia? | • The most common study types were quantitative studies and descriptive service reports • Few experimental, qualitative, or mixed methods studies • Few economic analyses of telepsychiatry services |

| RQ2. What types of telepsychiatry services were implemented in Australia? | • Most earlier services involved public health providers • Medicare-reimbursed telepsychiatry by private psychiatrists predominate since 2020 • The most frequent mode of telepsychiatry was videoconferencing |

| RQ3. What was known about the level of usage of telepsychiatry in Australia? | • Few studies examined usage levels and patterns over time • Early, regional services reported growth in usage • Prior to 2020, Medicare-funded telepsychiatry formed a tiny fraction of all Medicare psychiatric consultations • After the Medicare telehealth item expansion in 2020, a considerable increase in telepsychiatry usage was reported |

| RQ4. What were the reported quantitative outcome measures used? | • Few studies reported clinical outcomes of telepsychiatry using validated instruments • Comparisons with face-to-face consultations did not show significant differences in diagnostic accuracy and outcomes • Cost analyses of early services demonstrated cost savings with telepsychiatry • No cost analysis for Medicare-funded telepsychiatry |

| RQ5. What were the reported perceptions about telepsychiatry in Australia? | • Four main themes were identified • Patient (and caregiver) needs: improved access and flexibility; cost-saving; acceptance and satisfaction • Clinical care: rapport-building; issues with mental state examination; improved outcomes; safety and risk concerns • Service sustainability: administrative support; costs and funding; providers’ willingness to use telepsychiatry • Technical capability/capacity: need for infrastructure, devices, and technical support; cybersecurity and medicolegal issues |

| RQ6. What were the research gaps for telepsychiatry in Australia in the literature? | • Patient perspectives and engagement • Measurement of effectiveness and quality of care • Clinical practice: clinicians’ preferences; skills training; clinician-patient interactions • Health economic evaluation • Usage trends and patient profiles • Technology-related: new devices and safe use |

RQ1: Types of Research

Seventy-six publications were full articles, while the remainder were correspondence (n = 9), abstracts (n = 5), editorials (n = 3), commentaries (n = 2), and a book chapter. After excluding expert opinions (n = 14) and reviews (n = 6), the most common study types were quantitative studies (n = 43) and description of telepsychiatry service reports (n = 18). Retrospective observational studies were the most prevalent quantitative studies (n = 20). There were 3 quasi-experimental studies and no clinical trials, small numbers of qualitative studies (n = 7) and mixed methods studies (n = 5), and 4 case reports.

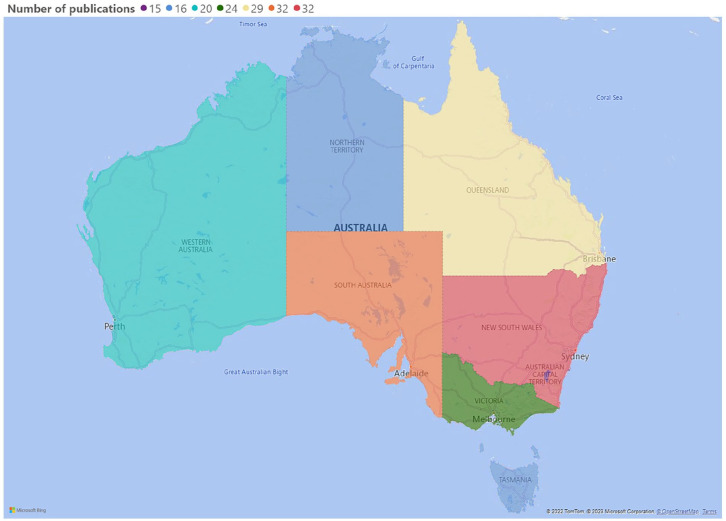

There were 76 papers that reported established clinical services. Thirty-two articles were related to nation-wide telepsychiatry. For states and territories, most papers came from New South Wales (NSW, n = 19), South Australia (n = 18), and Queensland (n = 15, Figure 3).

Figure 3.

A heat map of Australia representing the number of articles on telepsychiatry clinical services and studies conducted in each state and territory. Articles reporting telepsychiatry at the national level are included in the count for each state and territory.

RQ2: Types of Services

Most reported services and clinical studies involved public health providers (n = 57, 75%); only 9 reports involved private practice psychiatrists solely (12%). Comparing the publications before 2020 (n = 56) and 2020 onward (n = 20), increased involvement of private psychiatrists from 5% to 30% was seen.

The most frequent mode of telepsychiatry was videoconferencing alone (n = 48, 63%), while 30% involved both videoconferencing and telephone consultations. Only 2 reports were related to telephone consultations alone. Telepsychiatry was mostly used for direct general consultation for various diagnostic and therapeutic activities. Other clinical applications included indirect consultation (n = 7), Mental Health Act assessments (n = 3), cognitive behavioral therapy, inpatient management, and psychiatric assessment in the emergency department (1 each).

Most telepsychiatry services did not specify the patient subpopulations they served. Excluding case reports, only 5 publications definitively mentioned the involvement of adult patients (aged ≥18 years old). Many reports focused on children and adolescents (n = 19) and 3 reports each of geriatric services and forensic services, respectively. Only 2 reports of services specifically mentioned Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander patients. Before 2010, most funding came from funds or grants from Commonwealth and State governments. After 2010, most services were reimbursed by Medicare.

RQ3: Level of Usage

Fifty-three papers included information related to usage levels, but only few studies examined usage levels and patterns over time. Trott reported that in 1996, clinical usage of the Queensland Northern Regional Health Authority telemental health project doubled within the first 2 months, and subsequently plateaued. 37 The Rural and Remote Mental Health Service (RRMHS) in South Australia recorded the largest number of telepsychiatry sessions among the early services, with 2219 clinical sessions (1947 involving direct patient assessments) from 1994 to 1998. 8 Alexander and Lattanzio 38 also reported a steady rise in Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander patients utilizing the service of the RRMHS from 2006 to 2009. A report in 2016 noted that the annual number of sessions increased substantially from 400 sessions in the initial 3 years to more than 2600 sessions. 39

For Medicare-funded telepsychiatry, Smith et al found considerably increased annual number of consultations from 15 in 2002-2003 to 2555 in 2010 to 2011 but representing only 0.06% of all psychiatric consultations. 40 More usage data have been reported since the COVID-19 outbreak. Several studies reported that telepsychiatry constituted between 40% and 62% of all psychiatric consultations throughout the pandemic,18,19,41 -43 although fluctuations were present in the proportions of telepsychiatry across larger and smaller states.44,45 Snoswell et al examined telemental health services during the pandemic using interrupted time series regression analysis and found a significant increase. However, the analysis also included services provided by psychologists. 46 Another analysis of MBS data between January 2016 and June 2020 also found an increase in psychiatric consultations, with telepsychiatry representing a considerable portion. 43

RQ4: Quantitative Outcome Measures

Thirteen papers assessed the outcomes of telepsychiatry. Five papers employed validated instruments, including the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI), 47 Mental Health Inventory (MHI),48,49 Health of the Nation Outcome Scale (HoNOS),48,49 Severity of Dependence Scale, 50 Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Scale (DASS), 50 Behavior and Symptom Identification Scale (BASIS-32), 51 and Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale expanded version (BPRS-24). 51 All indicated patient improvement, except a pilot study in rural Queensland. 48 Whenever comparisons were made with face-to-face consultations, outcome differences were insignificant. One study assessed clinical effectiveness by calculating patient transferal rates to the metropolitan hospital, which was significantly lowered with telepsychiatry. 52 Two other studies found that telepsychiatry’s diagnostic accuracy was largely comparable with face-to-face assessments.13,53

There were 4 studies, all in Queensland, that performed cost analysis of telepsychiatry services.48,54 -56 All demonstrated that telepsychiatry was more cost-saving than alternative services. Additionally, 14 papers reported user satisfaction using non-standardized scales or questions, the findings of which were generally positive.

The most frequent comparator was face-to-face consultation (n = 22). One study compared telepsychiatry alone and in combination with a face-to-face consultation, 57 while another involved a comparison of videoconferencing with telephone assessments. 52 One more study examined the difference between low bandwidth (128 kbit/s) and high bandwidth (512 kbit/s) telepsychiatry and found that the higher bandwidth was associated with wider use. 58

RQ5: Perceptions About Telepsychiatry

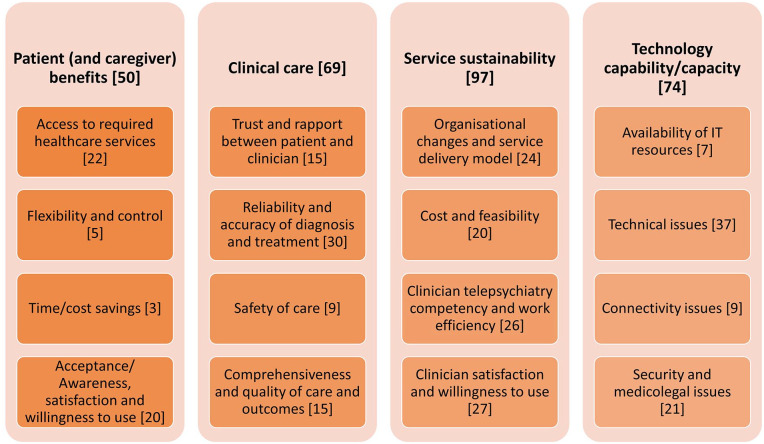

Based on the Framework for Telehealth Evaluation in Australia, four main themes were identified: patient (and caregiver) needs, clinical care, service sustainability, and technical capability/capacity (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Main themes and subthemes of perceptions about telepsychiatry in Australia from the reviewed publications. Numbers in brackets indicate number of publications coded for the subthemes.

Patient (and caregiver) benefits

Improved access to services was reported by patients,37,59,60 rural clinicians who were the referrers, 61 and telepsychiatry providers.62,63 Telepsychiatry allowed urgent assessment for remote areas.53,64 -66 Patients could be seen in their own setting or close to home.67,68 Thus, telepsychiatry reduced the need for rural patients making stressful travel to regional hospitals.37,69 -71 For Australian-based international telepsychiatry, time differences across different time zones might impair access to the service. 72

Telepsychiatry gave patients more flexibility and greater control over the consultation locale.59,69 They could choose to move out of view of the telehealth platform temporarily if they wished. 73 In contrast, rural referrers to a pediatric telepsychiatry service in NSW observed a lack of flexible availability of the service. 74 Time/cost-saving issues were identified in only a few papers and included the avoidance of traveling costs,37,75 and the absence of extra fees for the telepsychiatry service. 66

Some papers reported a high level of patient and caregiver acceptance13,72,76 and satisfaction.48,65 However, patient resistance was a barrier in a Victorian telepsychiatry program. 62 Cultural appropriateness, especially with Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander people37,62,77,78 requires better understanding 77 and the use of culturally sensitive interviewing techniques. 38

Clinical care

Some positive perceptions included: caregivers’ reports of good rapport and engagement 65 ; patients’ feeling they were treated respectfully 79 ; being listened to; and freedom to talk ad hoc during the consultations. 80 Nevertheless, clinicians sometimes reported difficulties in engaging patients, building rapport, and conveying empathy.47,59,67,81,82 Sometimes, patients felt more inhibited 62 and isolated 59 and perceived the interviewer as “dull” or “boring” on video display. 13 There was 1 report of a psychotic patient developing delusional beliefs toward the interviewer. 13 From a psychotherapeutic perspective, impact on therapeutic alliance and emergence of negative transference were postulated. 83

There were reservations regarding telepsychiatry’s inadequacy compared with face-to-face consultations.8,62,65,82 Mental state examination was limited,69,72 as nuances of mental state could be lost, 53 including nonverbal cues, affective prosody, and other subtleties.74,83,84 Telepsychiatry might be inappropriate for patients with significant hearing and visual disabilities,78,79,81 children under five 74 and young patients with psychopathologies such as anxiety and inattention. 67 Telepsychiatry might be problematic for insight-oriented dynamic psychotherapy. 85 A hybrid approach, with a planned and structured transition from the initial face-to-face session to subsequent telepsychiatry, was suggested.63,83,86

Telepsychiatry provided a safe interview environment 53 avoiding the risks of travel 82 and infection.63,84 However, there were also safety and risk concerns.67,81 The clinician lacked the means for effective engagement with an unstable patient. 83 A case report described the difficulty of safely conducting a hyperventilation exercise with an anxious patient through telepsychiatry. 47 The need for a proper safety plan was mentioned. 84

Positive outcomes included improved clinical care and reduced admissions.62,78,87 Patients concurred that telepsychiatry helped their treatment. 48 Telepsychiatry enabled continuity of care when face-to-face consultations were disrupted.81,88 Participation of family members who otherwise would not have attended appointments in home-based telepsychiatry illustrated its capacity for more comprehensive care. 67 However, some observed less family involvement in telepsychiatry. 74 Telepsychiatry could potentially function as virtual home visits, allowing greater insight into a patient’s psychosocial milieu. 69 Finally, clinicians providing telepsychiatry services to rural patients might lack local knowledge.74,89

Service sustainability

Under the theme of service sustainability, managerial support was important in the success of a telepsychiatry service.8,37,73,78,90 -92 The service model should be well-defined,91,93 coherent with organizational values, 94 and embedded as part of usual practice. 60 Streamlined systems were needed for booking, scheduling, prescribing (such as an e-prescribing system), billing, and reporting.78,81,84,91 Communication with clinicians on telepsychiatry availability was important.44,94 For some services, the inclusion of a telepsychiatry facilitator or coordinator was helpful.68,95 Telepsychiatry also contributed to more equitable distribution of mental health resources to remote and rural area. 96

High costs were an early concern. 85 However, infrastructural and technical advances have led to increasingly affordable costs. 97 Funding for services was also an issue, 75 especially for early services. 71 As Medicare subsidies were introduced, 98 telepsychiatry was gradually perceived as cost-saving.51,70,75,77,78,87,99 Telepsychiatry helped ensuring private practice business sustainability when face-to-face consultations were restricted during lockdowns.81,88

Lack of telepsychiatry knowledge and skills was a barrier among clinicians,37,59,83,92 and was described as a lack of “telehealth culture.” 78 Telepsychiatry-related procedures, such as scheduling, 48 were perceived as extra burdens.8,37 Staff training helped improving acceptance of telepsychiatry. 15 Telepsychiatry was also widely recognized as improving clinician efficiency.62,78,79,99 Potential downsides were increased fatigue due to long screen time, sedentary behavior, 59 and blurred work-life boundaries. 100

Rural telepsychiatry referrers reported positive experiences, particularly in reducing isolation and improving access to specialist support.38,61,68,75,79,89,94,101 However, support was not uniform 94 and some local rural workers felt devalued. 8 Some providers found that telepsychiatry was convenient59,60 and improved communication. 62 Nevertheless, conservatism 93 and resistance 62 were also reported as hurdles to implementation.

Technological capability/capacity

This theme encompasses the availability and use of technology as well as the potential complications of its use. There was a lack of IT infrastructure accessibility for psychiatrists,8,62,67 including portable devices.81,83,89 Patients may also lack basic devices such as private telephones, 66 especially among patients in rural and remote areas,70,87,102 Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander communities, 77 and elderly patients. 87

Audio and visual difficulties due to technical limitations or insufficient technical support, particularly for videoconferencing, were the commonest technical issues.37,47,62,63,65,69,72,79,82,99,101,103 The use of technical jargon and the lack of user-friendliness were other drawbacks.74,78 However, technical improvements led to perceived ease of use78,97 and satisfaction.48,71,73,75 Difficulties with security firewalls, platform preferences, and compatibility, especially in government organizations, were also mentioned. 87

Access to a network with adequate bandwidth ensured good transmission quality. 85 Connectivity problems were cited both in early publications75,82 and in more recent papers, especially in rural and remote areas.66,70 This issue persisted during the COVID-19 pandemic.63,65,67

Concerning security and medicolegal issues, privacy and confidentiality were mentioned,47,59,63,72,78,79,82,83,98 with special concerns about Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. 37 Privacy to practice in a quiet and confidential location was essential. 69 Additionally, cybersecurity concern70,72,81 warrants the use of licensed, secure videoconferencing platforms. 83 Medicolegal issues such as consent, prescribing rights, fee charging, and liability issues were raised.82,83,98 Assessments under the Mental Health Act 71 and issuing detention orders 98 through interstate telepsychiatry required accreditation of the clinician in both states. Concurrent registration in each country (patient/psychiatrist) was also required for international telepsychiatry. 72

RQ6: Research Gaps

Forty papers discussed telepsychiatry research gaps. Patients’ preferences, their experience and satisfaction with telepsychiatry required further study. Patients should be involved as partners in development, planning and implementation, 99 and the reasons behind patients’ reluctance to engage telepsychiatry need to be explored. 63 For children and adolescents, it was also necessary to better engage family members and caregivers in order to improve and enrich evaluation of telepsychiatry services. 67

Another research focus was the measurement of effectiveness and quality of care.20,59,79,104 The impacts of telepsychiatry on burnout, privacy, and safety should be investigated. 69 Additionally, psychometric properties of outcome measurement instruments, such as the HoNOS 105 and the MHI, 106 should be further studied. 49 Differences in efficacy between telepsychiatry via telephone and videoconferencing should also be examined. 46

Clinicians’ preferences and satisfaction, and web-based clinician-patient interaction requires further exploration. 83 Additionally, adaptations of interviewing techniques for telepsychiatry should be investigated. 85 Research on telepsychiatry skills training for clinicians, 59 suitable blended models of telepsychiatry and face-to-face care, 63 and private practitioners’ coordination with public mental health services, 84 was recommended.

Research on the equity of health resource distribution was mentioned,99,101 but more authors stated the need for economic evaluation, including possible cost-effectiveness analysis 89 and cost-benefit analysis56,107 to assess its feasibility and long-term sustainability. Examples included patient out-of-pocket costs for private telepsychiatry 20 and metrics for service efficiency targets. 108

Longitudinal study of service usage patterns was recommended, especially in the context of COVID-19.18,44 Investigating the effect of patient clinical characteristics, demographic and geographical factors was also suggested. 41 Tackling cultural attitudes toward telepsychiatry, especially involving individuals from indigenous or culturally diverse backgrounds, was another identified gap.38,77,78

Finally, some authors advocated further research on technological aspects. Examples included the use of portable devices, and hearing or visual aids for telepsychiatry catering to elderly patients. 79 Others suggested developing guidelines for the safe use of telepsychiatry 100 and monitoring their effect on users. 99 Cybersecurity should also be researched, 81 especially in the context of several recent significant data breaches for Australian health 109 and business 110 organizations.

Discussion

In this scoping review, we systematically searched major databases for all peer-reviewed publications related to telepsychiatry in Australia from 1990 onward and identified 96 publications. There was a noticeable surge of publications during the COVID-19 pandemic. Telepsychiatry, mostly in the form of videoconferencing for general consultations, was used in all states and territories, for various patient populations, and clinical conditions. We discuss the review findings in two broad areas: research methodologies and telepsychiatry service trends, highlighting the pre- and post-pandemic differences whenever relevant.

Many included papers were narrative descriptions of telepsychiatry services, especially in the early period. While they were useful to inform the initial development of telepsychiatry, they could not address pertinent research questions that require more rigorous methodologies. Many were quantitative, retrospective studies, with only very few involving experimental elements. Randomized trials of telepsychiatry have been conducted in several countries,111 -113 but not in Australia. When clinical trials are not feasible, quantitative research that employs a “natural experiment” design, such as interrupted time series, might be feasible.114,115 Recent papers researched publicly available Medicare data.18,41 -46 Analyses of Medicare reimbursement data continue to provide insights into the impact of policy decisions on the availability of telepsychiatry options.

There were few qualitative studies. While quantitative studies provide objective information on telepsychiatry-related research questions, they cannot provide in-depth and more nuanced explanations for the qualitative success or failure of a service. It is, therefore, necessary to explore the organizational contexts, behavioral patterns, and social interactions that are involved in telepsychiatry. 116 Additionally, mixed methods approaches, which integrate qualitative and quantitative investigations, may further improve understanding of complex healthcare interventions such as telepsychiatry. 117

There were very few health economic evaluations of Australian telepsychiatry services. All identified studies were conducted more than 10 years ago and focused on local or regional services.48,54 -56 For Medicare-funded rural and remote private practice telepsychiatry, only 1 study reported that the costs for videoconferencing items formed just 0.06% of the costs of all psychiatric consultations from July 2002 to June 2011, without further analysis of the costs incurred. 40 All 4 earlier studies attempted cost-minimization analysis by examining cost savings with telepsychiatry in comparison to face-to-face consultation. Given the absence of actual effectiveness data, cost-minimization analysis may be a suitable alternative to cost-effectiveness analysis for telepsychiatry in Australia. This is given that telepsychiatry has so far shown effectiveness largely equal to face-to-face consultation.22,23,118

Earlier services for rural and remote areas were run by public sector providers such as major public hospitals, often in collaboration with healthcare workers in rural services. The inclusion of telepsychiatry into the Medicare scheme in the early 2000s saw the entry of private practice psychiatrists, but their involvement remained low in the following years 40 until the pandemic arrived. 20 This shift has been a boon for telepsychiatry research in Australia, as it provides a trove of usage data at the national level, unparalleled by previous service data at local and regional levels, and indeed, unique internationally. From the clinical service perspective, although most of the new telepsychiatry items were made permanent, 119 it remains to be seen how well telepsychiatry can be fully integrated into private psychiatry practice.

The 4 main themes of perceptions of telepsychiatry in Australia identified: patient (and caregiver) benefits, clinical care, service sustainability, and technology capability/capacity largely align with the groupings of criteria and measures for key dimensions in the original Framework for Telehealth Evaluation in Australia. These themes resonate with the findings of qualitative studies on telemedicine in Australia during the COVID-19 pandemic. Reduced costs, 120 improved access120,121 and convenience120,122 are key benefits for patients. Clinicians from other specialities 122 and patients 120 also perceived rapport building and communication as important considerations and possible obstacles of telemedicine. Psychiatrists’ concerns regarding challenges with mental state examination and certain psychopathologies are unique to the discipline. Yet these ideas also correspond to the unease with inadequate examination and patient selection voiced by other clinicians. 122 A study involving general practitioners highlights several issues relevant to service sustainability, namely, financial and business pressures, logistical changes to existing services to incorporate telemedicine consultations, and the importance of clinician attitudes and experiences in shaping the use of telemedicine. 123 Finally, technical problems, such as limited connectivity, are also an issue. 120 Our framework might be a useful template for the development of qualitative research questions on telepsychiatry perceptions in Australia.

Some identified research gaps warrant mention. In exploring patients’ acceptance of telepsychiatry, the focus should not only be on technological characteristics. Patients’ social environment should also be considered, as the level of social support contributes to user acceptance.124,125 Regarding the clinical practice of telepsychiatry, in terms of clinician-patient interactions, we should identify useful skill sets for conducting online interviews and effective strategies for the inclusion of telemedicine interview training in medical education. 126 We should also examine the implementation process of telepsychiatry services to understand how a complex and relatively new intervention can be “normalized” as part of routine clinical practice. 127

This scoping review is the most comprehensive review of all peer-reviewed papers on telepsychiatry in Australia to date (2023). It offers an overview of telepsychiatry development in the country and provides the background for further research. This body of evidence can also serve as a useful reference for policymakers and clinicians in other countries, especially on the use of telepsychiatry to improve access in rural and remote areas and funding for large-scale telepsychiatry services. Further research could include usage trend analysis, clinician engagement and feedback, and economic evaluations, among others. Some study limitations need to be considered. In restricting the inclusion of sources to peer-reviewed publications, “Grey Publications” such as government reports were not included. This might have reduced the amount of data for synthesis. Despite employing a comprehensive search strategy, some publications might still have been missed. Given the diverse evidence sources, a critical appraisal of individual sources was not done. As this review focused on Australia, its findings might not be directly generalizable to other countries, especially those with very different healthcare funding and organization.

In conclusion, there is considerable evidence base on telepsychiatry in Australia, suggesting that it is a feasible mode of care. As telepsychiatry is being made more widely available, it is especially important to examine issues such as usage trends, integration into existing services, and economic evaluations to inform policy decisions. With careful consideration of local contexts and appropriate adaptations, analysis of the Australian experience could also contribute to the advancement of the practice of, and research into telepsychiatry internationally.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-docx-4-inq-10.1177_00469580241237116 for Telepsychiatry in Australia: A Scoping Review by Luke Sy-Cherng Woon, Paul A. Maguire, Rebecca E. Reay and Jeffrey C.L. Looi in INQUIRY: The Journal of Health Care Organization, Provision, and Financing

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-1-inq-10.1177_00469580241237116 for Telepsychiatry in Australia: A Scoping Review by Luke Sy-Cherng Woon, Paul A. Maguire, Rebecca E. Reay and Jeffrey C.L. Looi in INQUIRY: The Journal of Health Care Organization, Provision, and Financing

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-2-inq-10.1177_00469580241237116 for Telepsychiatry in Australia: A Scoping Review by Luke Sy-Cherng Woon, Paul A. Maguire, Rebecca E. Reay and Jeffrey C.L. Looi in INQUIRY: The Journal of Health Care Organization, Provision, and Financing

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-3-inq-10.1177_00469580241237116 for Telepsychiatry in Australia: A Scoping Review by Luke Sy-Cherng Woon, Paul A. Maguire, Rebecca E. Reay and Jeffrey C.L. Looi in INQUIRY: The Journal of Health Care Organization, Provision, and Financing

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-5-inq-10.1177_00469580241237116 for Telepsychiatry in Australia: A Scoping Review by Luke Sy-Cherng Woon, Paul A. Maguire, Rebecca E. Reay and Jeffrey C.L. Looi in INQUIRY: The Journal of Health Care Organization, Provision, and Financing

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Ms Elizabeth Bott, librarian of the Australian Capital Territory (ACT ) Health Services Library and Ms Megan Taylor, librarian of the Australian National University (ANU) Library for their assistance.

Footnotes

Author Contributions: LW, JL, PM, and RR contributed to the conception and design of the study. LW acquired, analyzed, and interpreted study data with assistance from JL, PM, and RR. LW wrote the first draft of the manuscript. JL, PM, and RR critically revised the manuscript. All authors read and gave final approval to the submitted version.

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethics Statement: Our study did not require ethical board approval because this is a review article that contains an analysis of existing scientific publications without any direct human subject participation.

ORCID iD: Luke Sy-Cherng Woon  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8216-0694

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8216-0694

Supplemental Material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- 1. Sood S, Mbarika V, Jugoo S, et al. What is telemedicine? A collection of 104 peer-reviewed perspectives and theoretical underpinnings. Telemed E Health. 2007;13(5):573-590. doi: 10.1089/tmj.2006.0073 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Standards Australia. Health informatics—Telehealth services—Quality planning guidelines. AS ISO 13131:2022, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Wade VA, Karnon J, Elshaug AG, Hiller JE. A systematic review of economic analyses of telehealth services using real time video communication. BMC Health Serv Res. 2010;10(1):233. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-10-233 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Mucic D. WPA global guidelines for telepsychiatry. Eur Psychiatry. 2021;64(Suppl 1):S124-S124. doi: 10.1192/j.eurpsy.2021.349 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Waugh M, Voyles D, Thomas MR. Telepsychiatry: benefits and costs in a changing health-care environment. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2015;27(6):558-568. doi: 10.3109/09540261.2015.1091291 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Shore J. The evolution and history of telepsychiatry and its impact on psychiatric care: current implications for psychiatrists and psychiatric organizations. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2015;27(6):469-475. doi: 10.3109/09540261.2015.1072086 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Allen A, Wheeler T. Telepsychiatry background and activity survey. The development of telepsychiatry. Telemed Today. 1998;6(2):34-37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hawker F, Kavanagh S, Yellowlees P, Kalucy RS. Telepsychiatry in South Australia. J Telemed Telecare. 1998;4(4):187-194. doi: 10.1258/1357633981932181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Lessing K, Blignault I. Mental health telemedicine programmes in Australia. J Telemed Telecare. 2001;7(6):317-323. doi:10.1258/1357633011936949 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Stein DJ, Naslund JA, Bantjes J. COVID-19 and the global acceleration of digital psychiatry. Lancet Psychiatry. 2022;9(1):8-9. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(21)00474-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Montoya MI, Kogan CS, Rebello TJ, et al. An international survey examining the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on telehealth use among mental health professionals. J Psychiatr Res. 2022;148:188-196. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2022.01.050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kinoshita S, Cortright K, Crawford A, et al. Changes in telepsychiatry regulations during the COVID-19 pandemic: 17 countries and regions’ approaches to an evolving healthcare landscape. Psychol Med. 2022;52(13):2606-2613. doi: 10.1017/S0033291720004584 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Baigent MF, Lloyd CJ, Kavanagh SJ, et al. Telepsychiatry: ‘tele’ yes, but what about the ‘psychiatry’? J Telemed Telecare. 1997;3(1_suppl):3-5. doi: 10.1258/1357633971930346 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Clarke PH. A referrer and patient evaluation of a telepsychiatry consultation-liaison service in South Australia. J Telemed Telecare. 1997;3(Suppl 1):12-14. doi: 10.1258/1357633971930788 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Yellowlees P, Kennedy C. Telemedicine applications in an integrated mental health service based at a teaching hospital. J Telemed Telecare. 1996;2(4):205-209. doi: 10.1258/1357633961930086 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Taylor A. Telehealth services in Australia and Brazil. In: Taylor A. (ed.) Healthcare Technology in Context: Lessons for Telehealth in the Age of COVID-19. Springer; 2021;81-119. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Department of Health. Australians embrace telehealth to save lives during COVID-19. Published April 20, 2020. Accessed January 8, 2022 https://www.health.gov.au/ministers/the-hon-greg-hunt-mp/media/australiansembrace-telehealth-to-save-lives-during-covid-19

- 18. Looi JC, Allison S, Bastiampillai T, Pring W, Reay R. Australian private practice metropolitan telepsychiatry during the COVID-19 pandemic: analysis of quarter-2, 2020 usage of new MBS-telehealth item psychiatrist services. Australas Psychiatry. 2021;29(2):183-188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Looi JC, Allison S, Bastiampillai T, Pring W, Kisely SR. Telepsychiatry and face-to-face psychiatric consultations during the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic in Australia: patients being heard and seen. Australas Psychiatry. 2022;30(2):206-211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Looi JC, Bastiampillai T, Pring W, et al. Lessons from billed telepsychiatry in Australia during the COVID-19 pandemic: rapid adaptation to increase specialist psychiatric care. Public Health Res Pract. 2022;32(4):e3242238. doi: 10.17061/phrp3242238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Chipps J, Brysiewicz P, Mars M. Effectiveness and feasibility of telepsychiatry in resource constrained environments? A systematic review of the evidence. Afr J Psychiatry. 2012;15(4):235-243. doi: 10.4314/ajpsy.v15i4.30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Guaiana G, Mastrangelo J, Hendrikx S, Barbui C. A systematic review of the use of telepsychiatry in Depression. Community Ment Health J. 2021;57(1):93-100. doi: 10.1007/s10597-020-00724-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hubley S, Lynch SB, Schneck C, Thomas M, Shore J. Review of key telepsychiatry outcomes. World J Psychiatry. 2016;6(2):269-282. doi: 10.5498/wjp.v6.i2.269 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Peters MDJ, Godfrey CM, Khalil H, et al. Guidance for conducting systematic scoping reviews. Int J Evid Based Healthc. 2015;13(3):141-146. doi: 10.1097/xeb.0000000000000050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Arksey H, O’Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2005;8(1):19-32. doi: 10.1080/1364557032000119616 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Anderson S, Allen P, Peckham S, Goodwin N. Asking the right questions: scoping studies in the commissioning of research on the organisation and delivery of health services. Health Res Policy Syst. 2008;6(1):7. doi: 10.1186/1478-4505-6-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. World Health Organization. Improving health systems and services for mental health. World Health Organization; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Levac D, Colquhoun H, O’Brien KK. Scoping studies: advancing the methodology. Implement Sci. 2010;5(1):69. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-5-69 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Peters MDJ, Marnie C, Tricco AC, et al. Updated methodological guidance for the conduct of scoping reviews. JBI Évid Synth. 2020;18(10):2119-2126. doi: 10.11124/JBIES-20-00167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Peters MDJ, Godfrey C, McInerney P, et al. Scoping reviews. In: Aromataris EMZ. (ed.) Joanna Briggs Institute Reviewer’s Manual. The Joanna Briggs Institute; 2017:1-28. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169(7):467-473. doi: 10.7326/M18-0850 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. McGowan J, Sampson M, Salzwedel DM, et al. PRESS peer review of electronic search strategies: 2015 guideline statement. J Clin Epidemiol. 2016;75:40-46. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2016.01.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Ouzzani M, Hammady H, Fedorowicz Z, Elmagarmid A. Rayyan-a web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst Rev. 2016;5(1):210. doi: 10.1186/s13643-016-0384-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Pollock D, Peters MDJ, Khalil H, et al. Recommendations for the extraction, analysis, and presentation of results in scoping reviews. JBI Évid Synth. 2023;21(3):520-532. doi: 10.11124/JBIES-22-00123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Elo S, Kyngäs H. The qualitative content analysis process. J Adv Nurs. 2008;62(1):107-115. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04569.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Dattakumar A, Gray K, Jury S, et al. A Unified Approach for the Evaluation of Telehealth Implementations in Australia. Institute for a Broadband-Enabled Society; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Trott P. The Queensland Northern Regional Health Authority telemental health project. J Telemed Telecare. 1996;2(2 Suppl 1):98-104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Alexander J, Lattanzio A. Utility of telepsychiatry for Aboriginal Australians. Aust N Z J Psychiatr. 2009;43(12):1185. doi: 10.3109/00048670903279911 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Mosler D. A 20-year history of telepsychiatry in South Australia: from inception to integration. Aust N Z J Psychiatr. 2016;50(S1):188. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Smith AC, Armfield NR, Croll J, Gray LC. A review of medicare expenditure in Australia for psychiatric consultations delivered in person and via videoconference. J Telemed Telecare. 2012;18(3):169-171. doi: 10.1258/jtt.2012.SFT111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Looi JC, Allison S, Bastiampillai T, et al. Increased Australian outpatient private practice psychiatric care during the COVID-19 pandemic: usage of new MBS-telehealth item and face-to-face psychiatrist office-based services in Quarter 3, 2020. Australas Psychiatry. 2021;29(2):194-199. doi: 10.1177/1039856221992634 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Looi JCL, Allison S, Kisely SR, et al. Greatly increased Victorian outpatient private psychiatric care during the COVID-19 pandemic: new MBS-telehealth-item and face-to-face psychiatrist office-based services from April-September 2020. Australas Psychiatry. 2021;29(4):423-429. doi: 10.1177/10398562211006133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Sreedharan S, Mian M, Giles S. Mental health attendances in Australia during the COVID-19 pandemic: a telehealth success story? Asia Pac J Public Health. 2021;33(4):453-455. doi: 10.1177/1010539521998857 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Looi JC, Allison S, Bastiampillai T, Pring W. Private practice metropolitan telepsychiatry in larger Australian states during the COVID-19 pandemic: an analysis of the first 2 months of new MBS telehealth item psychiatrist services. Australas Psychiatry. 2020;28(6):644-648. doi: 10.1177/1039856220961906 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Looi JC, Allison S, Bastiampillai T, Pring W. Private practice metropolitan telepsychiatry in smaller Australian jurisdictions during the COVID-19 pandemic: preliminary analysis of the introduction of new Medicare Benefits Schedule items. Australas Psychiatry. 2020;28(6):639-643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Snoswell CL, Arnautovska U, Haydon HM, Siskind D, Smith AC. Increase in telemental health services on the Medicare benefits schedule after the start of the coronavirus pandemic: data from 2019 to 2021. Aust Health Rev. 2022;46(5):544-549. doi: 10.1071/AH22078 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Cowain T. Cognitive–behavioural therapy via videoconferencing to a rural area. Aust N Z J Psychiatr. 2001;35(1):62-64. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1614.2001.00853.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Kennedy C, Yellowlees P. A community-based approach to evaluation of health outcomes and costs for telepsychiatry in a rural population: preliminary results. J Telemed Telecare. 2000;6:155-157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Kennedy C, Yellowlees P. The effectiveness of telepsychiatry measured using the health of the nation outcome Scale and the Mental Health inventory. J Telemed Telecare. 2003;9(1):12-16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Smirnov A, Hynes S, Davey G, Gonzales C. The Queensland injectors health network COVID-19 psychiatry telehealth project: pilot study of case conferencing to improve outcomes for people with dual diagnosis. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2021;40(1):S135-S135. doi: 10.1111/dar.13384 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51. D’Souza R. Telemedicine for intensive support of psychiatric inpatients admitted to local hospitals. J Telemed Telecare. 2000;6(Suppl 1):S26-S28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Buckley D, Weisser S. Videoconferencing could reduce the number of mental health patients transferred from outlying facilities to a regional mental health unit. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2012;36(5):478-482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Brett A, Blumberg L. Video-linked court liaison services: forging new frontiers in psychiatry in Western Australia. Australas Psychiatry. 2006;14(1):53-56. doi: 10.1080/j.1440-1665.2006.02236.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Smith AC, Scuffham P, Wootton R. The costs and potential savings of a novel telepaediatric service in Queensland. BMC Health Serv Res. 2007;7:35. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-7-35 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Smith AC, Stathis S, Randell A, et al. A cost-minimization analysis of a telepaediatric mental health service for patients in rural and remote Queensland. J Telemed Telecare. 2007;13(3_suppl):79-83. doi: 10.1258/13576330778324723917359571 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Trott P, Blignault I. Cost evaluation of a telepsychiatry service in northern Queensland. J Telemed Telecare. 1998;4(Suppl 1):66-68. doi: 10.1258/1357633981931515 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Bidargaddi N, Schrader G, Smith D, Carson D, Strobel J. Characteristics of patients seen by visiting psychiatrists through Medicare in a rural community mental health service with an established telemedicine service. Australas Psychiatry. 2017;25(3):266-269. doi: 10.1177/1039856216689527 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Bidargaddi N, Schrader G, Roeger L, et al. Early effects of upgrading to a high bandwidth digital network for telepsychiatry assessments in rural South Australia. J Telemed Telecare. 2015;21(3):174-175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Randall L, Raisin C, Waters F, et al. Implementing telepsychiatry in an early psychosis service during COVID-19: experiences of young people and clinicians and changes in service utilization. Early Interv Psychiatry. 2023;17:470-477. doi: 10.1111/eip.13342 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Saurman E, Perkins D, Roberts R, et al. Responding to mental health emergencies: implementation of an innovative telehealth service in rural and remote new South Wales, Australia. J Emerg Nurs. 2011;37(5):453-459. doi: 10.1016/j.jen.2010.11.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Gelber H, Alexander M. An evaluation of an Australian videoconferencing project for child and adolescent telepsychiatry. J Telemed Telecare. 1999;5(Suppl 1):S21-S23. doi: 10.1258/1357633991933297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Buist A, Coman G, Silvas A, Burrows G. An evaluation of the telepsychiatry programme in Victoria, Australia. J Telemed Telecare. 2000;6(4):216-221. doi: 10.1258/1357633001935383 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. McQueen M, Strauss P, Lin A, et al. Mind the distance: experiences of non-face-to-face child and youth mental health services during COVID-19 social distancing restrictions in Western Australia. Aust Psychol. 2022;57(5):301-314. doi: 10.1080/00050067.2022.2078649 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Clarke P, Hafner RJ. Telepsychiatry in South Australia. Australas Psychiatry. 1997;5(3):124-126. [Google Scholar]

- 65. Delves M, Luscombe GM, Juratowitch R, et al. Say hi to the lady on the television’: a review of clinic presentations and comparison of telepsychiatry and in-person mental health assessments for people with intellectual disability in rural New South Wales. J Policy Pract Intellect Disabil. 2023;20(2):177-191. doi: 10.1111/jppi.12448 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Saurman E, Johnston J, Hindman J, Kirby S, Lyle D. A transferable telepsychiatry model for improving access to emergency mental health care. J Telemed Telecare. 2014;20(7):391-399. doi: 10.1177/1357633X14552372 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Hopkins L, Pedwell G. The COVID PIVOT - re-orienting child and youth mental hHealth are in the light of pandemic restrictions. Psychiatr Q. 2021;92(3):1259-1270. doi: 10.1007/s11126-021-09909-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Taylor M, Kikkawa N, Hoehn E, et al. The importance of external clinical facilitation for a perinatal and infant telemental health service. J Telemed Telecare. 2019;25(9):566-571. doi: 10.1177/1357633X19870916 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Khanna R, Murnane T, Kumar S, et al. Making working from home work: reflections on adapting to change. Australas Psychiatry. 2020;28(5):504-507. doi: 10.1177/1039856220953701 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Noble D, Haveland S, Islam MS. Integrating telepsychiatry based care in rural acute community mental health services? A systematic literature review. Asia Pac J Heal Manag. 2022;17(2):1-13. doi: 10.24083/apjhm.v17i2.1105 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Yellowlees P. The use of telemedicine to perform psychiatric assessments under the Mental Health Act. J Telemed Telecare. 1997;3(4):224-226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Samuels A. International telepsychiatry: a link between New Zealand and Australia. Aust N Z J Psychiatr. 1999;33(2):284-286. doi: 10.1080/0004867990063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Yellowlees P, Kavanagh S. The use of telemedicine in mental health service provision. Australas Psychiatry. 1994;2(6):268-270. [Google Scholar]

- 74. Starling J, Foley S. From pilot to permanent service: ten years of paediatric telepsychiatry. J Telemed Telecare. 2006;12(3_suppl):80-82. doi: 10.1258/135763306779380147 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Dossetor DR, Nunn KP, Fairley M, Eggleton D. A child and adolescent psychiatric outreach service for rural New South Wales: a telemedicine pilot study. J Paediatr Child Health. 1999;35(6):525-529. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1754.1999.00410.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Yellowlees P, Richard Chan S, Burke Parish M. The hybrid doctor-patient relationship in the age of technology - telepsychiatry consultations and the use of virtual space. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2015;27(6):476-489. doi: 10.3109/09540261.2015.1082987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Edirippulige S, Bambling M, Fern EZP. Telemental health services for indigenous communities in Australia: a work in progress? In: Jefee-Bahloul H, Barkil-Oteo A, Augusterfer EF, eds. Telemental Health in Resource-Limited Global Settings. Oxford University Press; 2017:131-144. [Google Scholar]

- 78. Newman L, Bidargaddi N, Schrader G. Service providers’ experiences of using a telehealth network 12 months after digitisation of a large Australian rural mental health service. Int J Med Inform. 2016;94:8-20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Dham P, Gupta N, Alexander J, et al. Community based telepsychiatry service for older adults residing in a rural and remote region- utilization pattern and satisfaction among stakeholders. BMC Psychiatry. 2018;18(1):316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Wade VA, Eliott JA, Hiller JE. A qualitative study of ethical, medico-legal and clinical governance matters in Australian telehealth services. J Telemed Telecare. 2012;18(2):109-114. doi: 10.1258/jtt.2011.110808 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Looi JC, Pring W. To tele- or not to telehealth? Ongoing COVID-19 challenges for private psychiatry in Australia. Australas Psychiatry. 2020;28(5):511-513. doi: 10.1177/1039856220950081 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Sullivan DH, Chapman M, Mullen PE. Videoconferencing and forensic mental health in Australia. Behav Sci Law. 2008;26(3):323-331. doi: 10.1002/bsl.815 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Chherawala N, Gill S. Up-to-date review of psychotherapy via videoconference: implications and recommendations for the RANZCP psychotherapy written case during the COVID-19 pandemic. Australas Psychiatry. 2020;28(5):517-520. doi: 10.1177/1039856220939495 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Looi JC, Pring W. Private metropolitan telepsychiatry in Australia during covid-19: current practice and future developments. Australas Psychiatry. 2020;28(5):508-510. doi: 10.1177/1039856220930675 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Kavanagh SJ, Yellowlees PM. Telemedicine–clinical applications in mental health. Aust Fam Physician. 1995;24(7):1242-1247. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Eapen V, Dadich A, Balachandran S, et al. E-mental health in child psychiatry during COVID-19: an initial attitudinal study. Australas Psychiatry. 2021;29(5):498-503. doi: 10.1177/10398562211022748 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Burke D, Burke A, Huber J. Psychogeriatric SOS (services-on-screen) - a unique e-health model of psychogeriatric rural and remote outreach. Int Psychogeriatr. 2015;27(11):1751-1754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Looi JCL, Atchison M, Matias M, Viljakainen P. Sustainable operation of private psychiatric practice for pandemics. Australas Psychiatry. 2022;30(2):275-276. doi: 10.1177/10398562211052915 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Saurman E, Kirby SE, Lyle D. No longer ‘flying blind’: how access has changed emergency mental health care in rural and remote emergency departments, a qualitative study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2015;15:156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Hawker F. Rural and remote mental health service of South Australia: a personal perspective of its evolution. Australas Psychiatry. 2003;11(2):245-246. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1665.2003.t01-4-00557.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Kavanagh S, Hawker F. The fall and rise of the South Australian telepsychiatry network. J Telemed Telecare. 2001;7 Suppl 2(Suppl 2):41-43. doi:1258/1357633011937083 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Ryan VN, Stathis S, Smith AC, Best D, Wootton R. Telemedicine for rural and remote child and youth mental health services. J Telemed Telecare. 2005;11 Suppl 2(Suppl 2):S76-S78. doi: 10.1258/135763305775124902 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Yellowlees PM. The future of Australasian psychiatrists: online or out of touch? Aust N Z J Psychiatr. 2000;34(4):553-559. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1614.2000.00762.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Hockey AD, Yellowlees PM, Murphy S. Evaluation of a pilot second-opinion child telepsychiatry service. J Telemed Telecare. 2004;10(Suppl 1):48-50. doi: 10.1258/1357633042614186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Wood J, Stathis S, Smith A, Krause J. E-CYMHS: an expansion of a child and youth telepsychiatry model in Queensland. Australas Psychiatry. 2012;20(4):333-337. doi: 10.1177/1039856212450756 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. D’Souza R. Telehealth as a tool for a more equal distribution of mental health care to remote and rural populations - outcome studies in efficacy, effectiveness and efficiency of telepsychiatry in Australia. Aust N Z J Psychiatr. 2001;35(4):A6-A6. [Google Scholar]

- 97. Chapman M, Binns P, Stone P, Newby P, Pringle B. Telepsychiatry - how the west was won! Developing electronic clinical and educational services for rural and remote mental health services in Western Australia. Aust N Z J Psychiatr. 2012;46(1):15-15. doi: 10.1177/0004867412445952 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 98. O’Shannessy L. Using the law to enhance provision of telemedicine. J Telemed Telecare. 2000;6 Suppl 1:S59-S62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Gelber H. The experience in Victoria with telepsychiatry for the child and adolescent mental health service. J Telemed Telecare. 2001;7(Suppl 2):32-34. doi: 10.1258/1357633011937065 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Looi JC, Maguire PA, Bastiampillai T, Allison S. Penumbra of the pandemic workplace for psychiatrists and trainees in Australia. Australas Psychiatry. 2022;30(6):736-738. doi: 10.1177/10398562221109742 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Gelber H. The experience of the Royal Children’s Hospital Mental Health Service videoconferencing project. J Telemed Telecare. 1998;4(Suppl 1):71-73. doi: 10.1258/1357633981931542 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Myhill K. Telepsychiatry in rural South Australia. J Telemed Telecare. 1996;2(4):224-225. doi: 10.1258/135763396193011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Large M, Paton M, Wright M, Keller A, Trenaman A. Current approaches to enhancing non-metropolitan psychiatrist services. Australas Psychiatry. 2000;8(3):249-252. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1665.2000.00270.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 104. Greenwood J, Chamberlain C, Parker G. Evaluation of a rural telepsychiatry service. Australas Psychiatry. 2004;12(3):268-272. doi: 10.1111/j.1039-8562.2004.02097.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105. Wing JK, Beevor AS, Curtis RH, et al. Health of the Nation Outcome Scales (HoNOS). Br J Psychiatry. 1998;172:11-18. doi: 10.1192/bjp.172.1.11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106. Veit CT, Ware Je The structure of psychological distress and well-being in general populations. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1983;51:730-742. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.51.5.730 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107. Saurman E, Lyle D, Perkins D, Roberts R. Successful provision of emergency mental health care to rural and remote New South Wales: an evaluation of the Mental Health Emergency Care-Rural Access Program. Aust Health Rev. 2014;38(1):58-64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108. Saurman E, Lyle D, Kirby S, Roberts R. Assessing program efficiency: a time and motion study of the mental health emergency care - rural access program in NSW Australia. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2014;11(8):7678-7689. doi: 10.3390/ijerph110807678 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109. Taylor J. Medibank class action launched after massive hack put private information of millions on dark web. The Guardian. February 16, 2023. Accessed April 18, 2023. https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2023/feb/16/medibank-class-action-launched-data-breach-private-information-dark-web

- 110. Barrett J. Latitude Financial vows not to pay ransom to hackers in wake of massive data breach. The Guardian. April 11, 2023. https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2023/apr/11/latitude-financial-vows-not-to-pay-ransom-to-hackers-in-wake-of-massive-data-breach

- 111. De Las Cuevas C, Arredondo MT, Cabrera MF, Sulzenbacher H, Meise U. Randomized clinical trial of telepsychiatry through videoconference versus face-to-face conventional psychiatric treatment. Telemed E Health. 2006;12(3):341-350. doi: 10.1089/tmj.2006.12.341 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112. Farabee D, Calhoun S, Veliz R. An experimental comparison of telepsychiatry and conventional psychiatry for Parolees. Psychiatr Serv. 2016;67(5):562-565. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201500025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113. O’Reilly R, Bishop J, Maddox K, et al. Is telepsychiatry equivalent to face-to-face psychiatry? Results from a randomized controlled equivalence trial. Psychiatr Serv. 2007;58(6):836-843. doi: 10.1176/ps.2007.58.6.836 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114. Bernal JL, Cummins S, Gasparrini A. Interrupted time series regression for the evaluation of public health interventions: a tutorial. Int J Epidemiol. 2016;46(1):348-355. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyw098 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115. Khullar D, Jena AB. “Natural experiments” in health care research. JAMA Heal Forum. 2021;2(6):e210290-e210290. doi: 10.1001/jamahealthforum.2021.0290 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116. MacFarlane A, Harrison R, Wallace P. The benefits of a qualitative approach to telemedicine research. J Telemed Telecare. 2002;8(2_suppl):56-57. doi: 10.1177/1357633x020080s226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117. Caffery LJ, Martin-Khan M, Wade V. Mixed methods for telehealth research. J Telemed Telecare. 2017;23(9):764-769. doi: 10.1177/1357633x16665684 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118. Snoswell CL, Chelberg G, De Guzman KR, et al. The clinical effectiveness of telehealth: a systematic review of meta-analyses from 2010 to 2019. J Telemed Telecare. 2023;29(9):669-684. doi: 10.1177/1357633X211022907 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119. Department of Health and Aged Care. MBS Telehealth Services from 1 July 2022. Published July 5, 2022. Accessed April 28, 2023 http://www.mbsonline.gov.au/internet/mbsonline/publishing.nsf/Content/Factsheet-telehealth-1July22

- 120. Toll K, Spark L, Neo B, et al. Consumer preferences, experiences, and attitudes towards telehealth: qualitative evidence from Australia. PLoS One. 2022;17(8):e0273935. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0273935 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121. Thomas LT, Lee CMY, McClelland K, et al. Health workforce perceptions on telehealth augmentation opportunities. BMC Health Serv Res. 2023;23(1):182. doi: 10.1186/s12913-023-09174-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122. Smyth L, Roushdy S, Jeyasingham J, et al. Clinician perspectives on rapid transition to telehealth during COVID-19 in Australia – a qualitative study. Aust Health Rev. 2022;47(1):92-99. doi: 10.1071/AH22037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123. De Guzman KR, Snoswell CL, Giles CM, Smith AC, Haydon HH. GP perceptions of telehealth services in Australia: a qualitative study. BJGP Open. 2022;6(1):BJGPO.2021.0182. doi: 10.3399/bjgpo.2021.0182 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124. Harst L, Lantzsch H, Scheibe M. Theories predicting End-User acceptance of telemedicine use: systematic review. J Med Internet Res. 2019;21(5):e13117. doi: 10.2196/13117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125. Kim J, Park H-A. Development of a health information technology acceptance model using consumers’ Health Behavior Intention. J Med Internet Res. 2012;14(5):e133. doi: 10.2196/jmir.2143 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126. Martinez L, Holley A, Brown S, Abid A. Addressing the rapidly increasing need for telemedicine education for future physicians. Prime. 2020;4(16):16. doi: 10.22454/PRiMER.2020.275245 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127. May C, Finch T. Implementing, embedding, and integrating practices: an outline of normalization process theory. Sociology. 2009;43(3):535-554. doi: 10.1177/0038038509103208 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, sj-docx-4-inq-10.1177_00469580241237116 for Telepsychiatry in Australia: A Scoping Review by Luke Sy-Cherng Woon, Paul A. Maguire, Rebecca E. Reay and Jeffrey C.L. Looi in INQUIRY: The Journal of Health Care Organization, Provision, and Financing

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-1-inq-10.1177_00469580241237116 for Telepsychiatry in Australia: A Scoping Review by Luke Sy-Cherng Woon, Paul A. Maguire, Rebecca E. Reay and Jeffrey C.L. Looi in INQUIRY: The Journal of Health Care Organization, Provision, and Financing