Abstract

Introduction:

Immunotherapy (IT) is showing promise in the treatment of breast cancer, but IT alone only benefits a minority of patients. Radiotherapy (RT) is usually included in the standard of care for breast cancer patients and is traditionally considered as a local form of treatment. The emerging knowledge of RT-induced systemic immune response, and the observation that the rare abscopal effect of RT on distant cancer metastases can be augmented by IT, have increased the enthusiasm for combinatorial immunoradiotherapy (IRT) for breast cancer patients. However, IRT largely follows the traditional sole RT and IT protocols and does not consider patient specificity although patients’ responses to treatment remain heterogeneous.

Areas covered:

This review discusses the rationale of IRT for breast cancer, the current knowledge, challenges and future directions.

Expert opinion:

The synergy between RT and the immune system has been observed but not well understood at the basic level. The optimal dosages, timing, target, and impact of biomarkers are largely unknown. There is an urgent need to design efficacious pre-clinical and clinical trials to optimize IRT for cancer patients, maximize the synergy of radiation and immune response, and explore the abscopal effect in depth, taking into account patients’ personal features.

Keywords: Immunotherapy, radiotherapy, breast cancer, immune response, abscopal effect, precision medicine

1. Introduction

Breast cancer is the most commonly diagnosed cancer among American women, and there are about 3.8 million breast cancer survivors in the US. Around 43,600 women died of breast cancer in 2021, and an estimated 90% of these deaths are a consequence of metastatic disease, whether the cancer was metastatic at diagnosis or a metastatic recurrence that developed later [1].

In recent years, immunotherapy (IT), especially immune checkpoint blockade (ICB), has become a promising treatment for breast cancer patients, and the durable nature of the response to IT is particularly attractive [2]. However, IT alone for breast cancer has a low response rate which is usually <20% [3-6], partially because breast cancers typically lack infiltrating immune cells and have low to intermediate immunogenicity [4]. More and more research has been focused on combining additional interventions with IT to augment the tumor-specific immune response and improve treatment outcome. It has been reported that multiple local therapies, including high-intensity focused ultrasound, photodynamic therapy, cryotherapy, hyperthermia, and radiotherapy (RT), can induce immunologic effects that vary in frequency and level [7-11], and can potentially be combined with IT to overcome the primary or acquired immune resistance for the patients.

The focus of this review is the combination of IT and RT. RT is usually coupled with surgery and chemotherapy as the standard of care for breast cancer patients [12]. Randomized clinical trials have shown that RT can improve local control and overall survival for breast cancer patients [13-16], but RT is generally prescribed for localized tumors only and not an option for systemic treatment. Emerging data suggest that local RT can also produce systemic immune stimulatory effects [17-20]. Combinatorial immunoradiotherapy (IRT) is relatively new for breast cancer, and the optimal combination is largely undetermined.

Breast cancer is a highly heterogeneous disease due to the diverse biologic, clinical, genetic and environmental features of the patients [21-28]. However, the existing treatment protocols are based on the average outcome of previous clinical trials, and IRT usually follows the traditional sole RT and IT protocols. Given the limited option of treatments and the high levels of disease heterogeneity, there is an urgent need to replace the “one size fits all” approach with personalized approaches to prescribe IRT for breast cancer patients, taking into account patient specificity.

In this article, we summarize the current research of IRT for breast cancer, and discuss the mechanisms of the therapeutic effects, the limitations of current protocols, the need for optimal and precision treatments, and future research directions.

2. RT and immune response

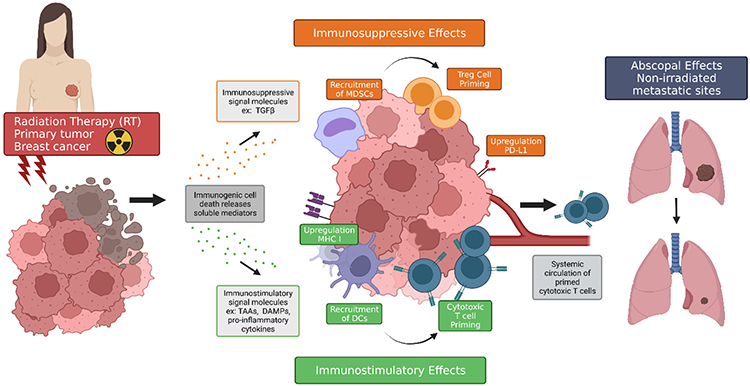

Traditionally, the effectiveness of RT has been interpreted as the result of irreparable DNA damages within the tumor cells, resulting in cell death and/or loss of replicative potential [29]. Recently, it is increasingly appreciated that RT can not only be a locoregional treatment but also be a key element in the systemic therapy for cancer patients [18-20]. Understanding the immunomodulatory effects and the associated mechanism of RT alone is critical for optimizing RT and combining it with other therapeutics. Figure 1 illustrates the effects of RT on the immune system.

Figure 1. Effects of RT on the immune system.

RT causes immunogenic cell death releasing soluble mediators including cytokines, chemokines, tumor-associated antigens (TAAs), and damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) inducing immunosuppressive and immunostimulatory effects and occasionally, abscopal effects. Immunosuppressive signaling molecules such as transforming growth factor β (TGFβ) are accompanied with recruitment of myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs), upregulation of programmed cell death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) on local tumor cells, and activation of regulatory T cells. Pro-inflammatory molecules namely DAMPs, and pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines are accompanied by enhanced expression of major histocompatibility complex I (MHC I), recruitment of antigen-presenting cells (APCs) like dendritic cells (DCs), and APC loading with antigens. Tumor antigen-loaded APCs increase T cell activation and proliferation and consequently, tumor cell recognition. Activated cytotoxic T cells travel in the circulatory system to distant sites of metastasis where, though rare, abscopal effects can occur.

Emerging data suggest that local RT can produce systemic immune stimulatory effects. Radiation induces tumor cell death and the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines, chemokines, tumor antigens and damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs). These signals can enhance antigen-presenting cell (APC) functions to activate tumor-specific T cell immunity. They stimulate the recruitment of APCs, promote the expression of major histocompatibility complex (MHC) by APCs and tumor antigen loading onto APCs, drive the migration of antigen-loaded APCs to draining lymph nodes, and enhance the proliferation of T cells and the recognition of the tumor by T cells [18,19,30-32].

On the other hand, RT can also induce, at the site of tumors, immunosuppressive effects. It can activate inhibitory immune components such as transforming growth factor β (TGFβ), regulatory T (Treg) cells, tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) and myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs), and upregulate the expression of programmed cell death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) on tumor cells which is a strong biological correlate of immunosuppression in cancer sites [32-37].

The abscopal effect, which describes the anticancer effect on tumor cells located distant from the locally treated site, was originally described by Mole in 1953 for radiation [38], but this concept been expanded nowadays because literature shows other local therapies can also cause abscopal effect [39-41]. The abscopal effect has been reported for various cancers including breast cancer over the years [42]. Considering the majority of deaths due to breast cancer are a consequence of metastatic disease [1,43], the abscopal effect may effectively suppress or eliminate the distant cancer cells and significantly benefit breast cancer patients. However, the abscopal effect arising from RT alone is exceedingly rare and only 46 cases were reported between 1969 and 2014 [44]. Pre-clinical studies show the abscopal effect is mediated by the immune system [45,46]. Although RT can promote proliferation and priming of T cells, the concentration of fully functional T cells induced by radiation alone is usually not sufficient to elicit an antitumor immunity due to the immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment associated with established tumors, which partially explains the rarity of abscopal effects caused by RT alone.

So far, our understanding of the influence of RT characteristics, such as RT dose, fractionation, dose rate, and treatment volume, on tumor immune modulation is largely incomplete, and we still lack effective strategies to enhance and utilize abscopal effects caused by RT.

3. IRT

Historically, it was considered that breast cancers were generally non-immunogenic [47]. However, recent studies suggested that breast cancers, particularly human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2)-positive and triple-negative breast cancers (TNBC), are immunogenic [48]. Different immunotherapeutic agents have been employed for breast cancer therapy, including monoclonal antibodies that target the oncogenic membrane receptors (e.g., HER2 extracellular domain) [48-51], cancer vaccines [32,52-54], adoptive cell therapy [35,37,55], and ICB (e.g., cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated protein 4 (CTLA-4) and programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1)/ PD-L1 antibodies) [3,5,32,56-58]. Among ICB antibodies, pembrolizumab (anti-PD-1) has been approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for early and advanced TNBCs based on KEYNOTE-522 [59] and KEYNOTE-355 [60] trials, respectively. The addition of pembrolizumab to chemotherapy benefits patients with early TNBC regardless of PD-L1 status [59], but only benefits advanced TNBC patients with PD-L1-positive disease [60]. However, the overall response rates to anti-PD-L1/PD-1 are still relatively low and immune response following treatment is not robust [4,56]. ICB alone is usually not efficacious to induce sufficient priming and/or infiltration of antitumor cytotoxic lymphocytes, and only benefits a minority of cancer patients.

Pre-clinical and clinical studies [45,46,61,62] found that, the combination of RT and IT, especially ICB, can enhance the immunomodulation and cross-priming of cytotoxic T-lymphocytes, augment the antitumor immune responses elicited by ICB, and promote durable, systemic immune response in both immunogenic and poorly immunogenic tumors (Figure 2). Moreover, the rare abscopal effect of RT on distant metastases can be augmented by IT [11,61,63]. The mechanism is that IT blocks the molecules that suppress the antitumor function of activated CD8 T cells, including Treg cells and checkpoint molecules expressed by T cells (CTLA-4 and PD-1) and by tumor cells (PD-L1), and restores the antitumor activity of T cells capable of rejecting tumor cells outside the radiation field (Figure 2). These findings provide the rationale for IRT for locally advanced or metastatic cancer, which is relatively new and under-studied for breast cancer [64,65].

Figure 2. Synergistic effects of combined IRT.

RT is performed at the primary tumor site inducing a mixture of immunosuppressive and immunostimulatory effects. Abscopal effects are rare because, most of time, the induced concentration of T cells is not sufficient to overcome the immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment. ICB uses antibodies for targeting surface molecules PD-1 and CTLA-4 of regulatory and effector T cells and PD-L1 of cancer cells to block the immunosuppressive effects of checkpoint proteins, sustaining the activation and anti-tumor effector function of T cells. Separately, response rates to RT and IT are low in metastatic disease and durable, systemic responses are unlikely. When combined, immunomodulation and cross-priming of T cells is greatly enhanced leading to robust locoregional responses; systemic antitumor responses are also amplified, leading to greater possibility for abscopal effects at distant metastatic sites.

There are conflicting reports on the efficacy of RT dose, fraction, timing (RT relative to IT) in eliciting the immune response. In current practice, IRT has largely followed the same protocol as the sole RT or IT. Furthermore, the current protocols completely ignore the fact that patients’ responses to the treatments remain heterogeneous. Therefore, IRT for breast cancer has multiple unresolved issues, including the limited information on the optimal dosages of RT and IT, RT fractionation, treatment volume and target selection, timing of RT with respect to IT, and the lack of the specific guidance of patient prescreening and classification.

4. Challenges for optimizing IRT

Figure 3 schematically shows the possible challenges for optimizing and personalizing IRT. RT dose and fractionation (F) that can optimize the ratio of immunogenic effects to immunosuppressive effects have not been established. Based on the early pre-clinical work [61,66], hypofractionated ablative RT such as 24Gy/3F or 30Gy/5F is more effective than a single high dose fraction of 20-30 Gy and was used as the standard dose-fractionation scheme for IRT. Vanpouille-Box et al. [66] showed that dose per fraction above 12-18 Gy can induce the DNA exonuclease Trex1 which attenuates tumor immunogenicity by removing cytosolic DNA, while repeated fractions of 8-10 Gy can amplify interferon- β production, induce cross presentation, T cell priming and tumor rejection as demonstrated by abscopal effects. However, the clinical efficacy of such hypofractionated protocols has not been demonstrated in several recent clinical trials for a variety of cancers including non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), melanoma and breast cancer [67,68], which makes the optimal RT dose and fractionation elusive. It is possible that other dose-fractionation schemes including conventionally fractionated RT will be more effective, and it is necessary to map out the unchartered territory of dose including those that have been previously assumed invalid. Besides the uncertainty in RT dose/fractionation, the optimal dose of immunotherapeutic agent may also vary when combining RT and IT because the two therapeutics interact with each other, while most of the previous IRT studies investigated RT dose and fraction regimens only.

Figure 3. Challenges for optimizing and personalizing IRT.

While protocols exist for IT and RT separately, impacts and effects of either treatment must be considered in congruence for future combination protocols. In RT, immunosuppressive and immunogenic effects must be balanced to promote greatest efficacy; RT dose, fractionation, and target volume must be adjusted to allow this balance in IRT. Likewise, IT dose must be evaluated to account for synergism of combined RT and IT protocols. Assessments of time windows for IRT are necessary and staged or simultaneous administrations may prove optimal based on tumor characteristics. Studies to determine biomarkers and genetic profiling for precision IRT are emerging, but multifactorial predictive indicators complicate the process. Individual traits such as host factors, tumor mutation burden, PD-L1 expression, tumor infiltrating lymphocyte, and radiation sensitivity all play a role in clinical treatment.

Conflicting recommendations of the optimal time window for IRT have been reported. Some study reported advanced melanoma patients who received anti-CTLA-4 IT before RT had better antitumor responses than those receiving IT after RT [69]. Another study [70] reported the addition of anti-PD-1 treatment after chemoradiation therapy for non-small cell lung cancer patients demonstrated a significant improvement in progression-free survival and overall survival. Other studies [61,71,72] showed the concomitant administration of RT and anti-PD-L1 or anti-CTLA-4 IT was superior to sequential administrations. Young et al. [54] evaluated time sequencing of two IT agents (anti-CTLA-4 and anti-OX40) relative to RT using murine colorectal and breast cancer models, and found anti-CTLA-4 was most effective when given prior to RT, in part due to regulatory T cell depletion, while anti-OX40 was most effective when given one day after RT during the window of increased antigen presentation. They proposed that the optimal timing of IT relative to RT depends on the mechanism of action of the IT used. Therefore, it is expected that the optimal timing for the combination of RT and IT needs to be determined case by case.

The RT target volume may need to be revisited. First, the traditional clinical target volume (CTV) and planning target volume (PTV) may well be overkill when RT is combined with IT. The smaller target can better spare organs at risk and is possibly adequate to induce enough immune stimulation [73]. Related to this, it needs to be determined whether uniform or heterogeneous irradiation is preferred for immune stimulation. Studies reported spatial fractionated RT (SFRT) or GRID, which is to treat the tumor with a non-uniform, sieve-like dose, can more effectively trigger local and distant tumor control than open field radiation [74]. Second, animal tumors are irradiated without any preceding surgery in most pre-clinical studies, while most human patients received RT after surgical removal of the tumor. It is necessary to find out if the sequence of lymph nodes and bulk tumor removal relative to RT makes a difference in RT-induced immune responses. Third, most real breast cancer patients have both tumor and draining lymph nodes irradiated to reduce the risk of cancer recurrence. Considering that the lymph nodes are needed for interactions between dendritic cells and T cells, it is necessary to determine whether irradiating the tumor but sparing lymph nodes can maximize synergy with the immune system. However, the risk of inadequate irradiation (undertreatment) has to be considered and more rigorous evidence needs to be generated to guide the partial or nonuniform irradiations.

Since metastatic breast cancer causes the majority of deaths, it is highly desirable to explore the abscopal effect in depth to eliminate distant metastases and achieve the maximum benefit. Some of the challenges listed above are also relevant to abscopal effect, e.g., if hypofractionated RT is preferred to the standard fractionation, and if the abscopal effect depends on the irradiated target volume. Besides these issues, it is not clear if animal model used in the pre-clinical studies, i.e., subcutaneous tumor or orthotopic tumor models, will affect the experimental results since most pre-clinical findings are based on subcutaneous tumor models, and if irradiating multiple or all lesions is necessary to enhance abscopal responses [75]. Besides the factors listed above, both RT and IT regimens and their sequence should be fine-tuned in order to make abscopal tumor regression more likely.

5. Challenges for precision IRT

The current imaging and RT delivery techniques allow anatomical personalization [40,41], but precision IRT is still in its infancy. Different patients respond to treatment very differently, i.e., for patients who have the same type, stage and location of disease, the identical RT dose and fractionation cured some but were invalid or induced severe morbidities to the others [21]. Molecular markers and gene expression profiling are being actively investigated as means of personalizing RT and other therapies for breast cancer patients, but currently there are very few robust biomarkers for predicting responses to RT [76-78]. The optimal dose for treating patients with an immunotherapeutic agent may differ according to the patients’ individual characteristics. Goldstein et al. [79] showed that a weight-based personalized pembrolizumab dose demonstrated a therapeutic efficacy in PD-L1 positive non-small cell lung cancer patients, equivalent to the efficacy of the FDA approved dose, but would have a significant reduction of drug cost. The authors called for personalized IT and emphasized the importance of it. However, currently there are no reliable biomarkers to help inform patient screening and classification, monitor treatment responses, and identify optimal treatment strategies to maximize antitumor immunity with minimal toxicity. To further cloud the issue, increasing evidence suggests that responses to cancer treatments such as IT, RT, or IRT cannot be adequately predicted by a single biomarker [80].

Tumor mutation burden (TMB) has been reported as a promising biomarker to predict clinical response to IT for various cancer types including breast cancer [81,82]. Microsatellite instability (MSI) is another predictive biomarker for cancer IT [83], and a combination of MSI and TMB is very informative for cancer diagnosis and treatment prescription because it provides additional characterization of tumor microenvironment. In 2017 and 2020, FDA granted accelerated approval to pembrolizumab for adult and pediatric patients with unresectable or metastatic MSI-high cancer [84,85] and TMB-high solid tumors [86], including breast cancer. Previously, measuring MSI relied on the immunohistochemistry or polymerase chain reaction (PCR) which may produce false negative results, and measuring TMB required the accurate but technically complicated and expensive whole exome sequencing (WES). TMB or MSI quantification based on the new next-generation sequencing (NGS) panel is a promising solution [87,88], and a few companies in the US such as FoundationOne provide both TMB and MSI testing.

Literature shows that high PD-L1 expression is positively associated with therapeutic response of melanoma, non-small cell lung cancer, and advanced TNBC patients who received anti-PD-1 or anti-PD-L1 IT [60,89,90], and is a potential prognostic biomarker for squamous cell anus carcinoma and head and neck cancer patients who received chemoradiotherapy [91,92]. However, the predictive role of PD-L1 expression in IRT is unclear. In some of the previous studies about melanoma, NSCLC and early TNBC breast cancer patients, PD-L1 negative tumors still responded to ICB [59,93] or IRT [94], suggesting that PD-L1 expression is not a definitive biomarker for all cancers or cancer stages. The variations in PD-L1 expression level also reduce the accuracy and reliability of PD-L1 expression as an independent biomarker [95].

Tumor infiltrating lymphocyte (TIL) is another potential biomarker. Studies have demonstrated the greater numbers of TILs are associated with breast cancer outcome after adjuvant chemotherapy such as disease-free survival and overall survival [96,97], and can be used as an independent predictor of response to chemotherapy [98,99]. The correlation between TILs and IRT outcome, however, is unknown.

Besides these tumor- and blood-related biomarkers, the other general features of the patients such as age, sex, weight, and lifestyle can also potentially influence the treatment outcome [23,100-103] and should be considered in the personalized prescription, which will certainly increase the complexity of future research studies and pre-clinical and clinical trials.

To the best of our knowledge, no clinical or pre-clinical studies have reported precision IRT for any cancer site. Considering that IT and RT are costly, may induce severe side effects and have limited efficacy in some patients, preselection of patients who are more likely to benefit from the specific treatment regimens can significantly lower the national cost of breast cancer care.

6. Conclusions

The concept of IRT is appealing because it has shown greater potential to treat breast cancer patients than RT or IT alone. However, our understanding of the influence of RT characteristics on tumor immune modulation and the beneficial abscopal effect is largely incomplete. Currently there are very few robust biomarkers for IRT, and precision IRT protocol based on them is lacking. Therefore, there is an urgent need to design efficacious pre-clinical and clinical trials to optimize IRT for cancer patients, maximize the synergy of radiation and immune response, and explore the abscopal effect in depth, taking into account patients’ personal features.

7. Expert opinion

The synergy between RT and the immune system has been observed in pre-clinical studies and clinical practice but not well understood at the basic level. The optimal dosages, timing, treatment volume, and impact of biomarkers are largely unknown. Investigation of these issues by clinical trials is difficult due to a multitude of variables involved, high risks and expenses. The lack of sufficient pre-clinical data also impedes a guided design of clinical trials.

Traditional clinical trials aim to find an optimal treatment without considering inter-patient heterogeneity. Precision medicine requires a departure from conventional trial methodology in that the optimal treatment should be tailored to patient subgroups. Moreover, due to the different mechanisms for treating cancer, IT behaves differently from chemotherapy or RT: the efficacy of IT may not increase with dose, and immune response is a unique and important outcome that is often closely related to the clinical outcome because IT achieves its therapeutic effect through activating the immune system. As the immune response is often quickly ascertainable, it provides a useful endpoint that can be used to quickly screen out futile doses and predict clinical outcome during a trial. The development of clinical trial designs for precision IT or IRT is still at its infancy. For those trials, it is desirable to simultaneously consider immune response, efficacy, and toxicities of multiple modalities, and explicitly account for patient heterogeneity and biomarkers. In addition, it is challenging to carry out subgroup dose finding based on biomarkers such as PD-L1 due to the typically small sample size in early phase oncology trials.

Several areas should be explored by the future pre-clinical and clinical studies. First, clinical trials are usually very expensive, and trial design that can accommodate small sample sizes is highly desirable. Efficacious pre-clinical and clinical trials that can accommodate small sample sizes and can take into account both efficacy and toxicity of the treatment should be pursued. Bayesian adaptive trial designs are particularly desirable due to their ability to incorporate historical and/or expert knowledge and the unique feature of the Bayesian approach [104,105]. For trials with small sample size and relatively large number of covariates, variable selection can be performed to reduce the dimension of the covariates [105]. Second, optimal IRT protocols for breast cancer patients should be searched instead of relying on the assumption that the standard IT and RT protocols are also applicable to IRT. Moreover, safety and efficacy of various combinations should be evaluated, along with investigations of therapeutic mechanisms. Unfortunately, funding for clinical testing of questions about RT and IT dose, fractionation, timing, volume etc. is very limited and difficult to secure. Federal agencies and foundations may need to reconsider their funding priority and sponsor these fundamental but important studies. Third, ICB is currently applied to TNBC, while it has not been approved for other subtypes and very few clinical studies reported treating hormone receptor positive (HR+) such as luminal A or B breast cancer using IT [106]. A recent phase II study showed RT combined with pembrolizumab did not produce an objective response in patients with HR+ metastatic breast cancer, but the enrolled patients were heavily pre-treated and the number of patients was low [107]. It is possible RT would extend the application of ICB to other subtypes by causing inflammatory response, and more investigation is warranted. Fourth, the predictive roles of various biomarkers and their combinations should be evaluated and the precision treatment strategy for different patient subgroups should be determined. Obviously, gaining fundamental knowledge on IRT and biomarkers will require exploratory, in-depth experiments such as imaging, genome sequencing, immunophenotyping, and some of them may generate negative or null results. Finally, the abscopal effect should be further explored using various dose regiments, tumor models, tumor volumes, and therapeutic sequences because it can potentially have a very high impact, cure breast cancer metastasis, and significantly reduce breast cancer mortality.

The advances in these areas will have profound impacts. They will significantly increase the confidence of IRT for breast cancer, suggest prescreening, dose, and timing guidelines, increase efficacy and reduce adverse effects, and enhance the base of evidence upon which clinical decisions can be made. All of these can potentially bring in enormous savings of time, cost and human resources, accelerate progress toward ending breast cancer and benefit all breast cancer patients worldwide.

Footnotes

Declaration of interest

The authors have no relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript.

References

- 1.Jin X, Mu P. Targeting Breast Cancer Metastasis Breast Cancer-Basic. 2015;9:23–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Emens LA. Breast Cancer Immunotherapy: Facts and Hopes Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. 2018. Feb 1;24(3):511–520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thomas R, Al-Khadairi G, Decock J. Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors in Triple Negative Breast Cancer Treatment: Promising Future Prospects Frontiers in oncology. 2020;10:600573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tokumaru Y, Joyce D, Takabe K. Current status and limitations of immunotherapy for breast cancer Surgery. 2020. Mar;167(3):628–630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zou YT, Zou XXZ, Zheng SQ, et al. Efficacy and predictive factors of immune checkpoint inhibitors in metastatic breast cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis Therapeutic advances in medical oncology. 2020. Aug;12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hu ZI, Ho AY, McArthur HL. Combined Radiation Therapy and Immune Checkpoint Blockade Therapy for Breast Cancer Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2017. Sep 1;99(1):153–164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.van Duijnhoven FH, Aalbers RI, Rovers JP, et al. The immunological consequences of photodynamic treatment of cancer, a literature review Immunobiology. 2003;207(2):105–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yang X, Gao M, Xu R, et al. Hyperthermia combined with immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy in the treatment of primary and metastatic tumors Frontiers in immunology. 2022;13:969447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wu F, Zhou L, Chen WR. Host antitumour immune responses to HIFU ablation International journal of hyperthermia : the official journal of European Society for Hyperthermic Oncology, North American Hyperthermia Group. 2007. Mar;23(2):165–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sabel MS, Nehs MA, Su G, et al. Immunologic response to cryoablation of breast cancer Breast cancer research and treatment. 2005. Mar;90(1):97–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ho AY, Wright JL, Blitzblau RC, et al. Optimizing Radiation Therapy to Boost Systemic Immune Responses in Breast Cancer: A Critical Review for Breast Radiation Oncologists Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2020. Sep 1;108(1):227–241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Halperin EC, Wazer DE, Perez CA, et al. Perez and Brady's Principles and Practice of Radiation Oncology, 7th Edition. Philadelphia, PA: LWW; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 13.McGale P, Taylor C, Correa C, et al. Effect of radiotherapy after mastectomy and axillary surgery on 10-year recurrence and 20-year breast cancer mortality: meta-analysis of individual patient data for 8135 women in 22 randomised trials Lancet. 2014. Jun 21;383(9935):2127–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fisher B, Anderson S, Bryant J, et al. Twenty-year follow-up of a randomized trial comparing total mastectomy, lumpectomy, and lumpectomy plus irradiation for the treatment of invasive breast cancer N Engl J Med. 2002. Oct 17;347(16):1233–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Clarke M, Collins R, Darby S, et al. Effects of radiotherapy and of differences in the extent of surgery for early breast cancer on local recurrence and 15-year survival: an overview of the randomised trials Lancet. 2005. Dec 17;366(9503):2087–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Darby S, McGale P, Correa C, et al. Effect of radiotherapy after breast-conserving surgery on 10-year recurrence and 15-year breast cancer death: meta-analysis of individual patient data for 10,801 women in 17 randomised trials Lancet. 2011. Nov 12;378(9804):1707–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Demaria S, Bhardwaj N, McBride WH, et al. Combining radiotherapy and immunotherapy: a revived partnership Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2005. Nov 1;63(3):655–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ahmed MM, Hodge JW, Guha C, et al. Harnessing the Potential of Radiation-Induced Immune Modulation for Cancer Therapy Cancer immunology research. 2013. Nov;1(5):280–284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Formenti SC, Demaria S. Systemic effects of local radiotherapy Lancet Oncology. 2009. Jul;10(7):718–726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Carvalho HA, Villar RC. Radiotherapy and immune response: the systemic effects of a local treatment Clinics (Sao Paulo). 2018. Dec 10;73(suppl 1):e557s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Langlands FE, Horgan K, Dodwell DD, et al. Breast cancer subtypes: response to radiotherapy and potential radiosensitisation Br J Radiol. 2013. Mar;86(1023):20120601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shaitelman SF, Howell RM, Smith BD. Effects of Smoking on Late Toxicity From Breast Radiation J Clin Oncol. 2017. May 20;35(15):1633–1635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Colzani E, Johansson AL, Liljegren A, et al. Time-dependent risk of developing distant metastasis in breast cancer patients according to treatment, age and tumour characteristics British journal of cancer. 2014. Mar 4;110(5):1378–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Huszno J, Budryk M, Kolosza Z, et al. The influence of BRCA1/BRCA2 mutations on toxicity related to chemotherapy and radiotherapy in early breast cancer patients Oncology. 2013;85(5):278–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bollet MA, Sigal-Zafrani B, Mazeau V, et al. Age remains the first prognostic factor for loco-regional breast cancer recurrence in young (<40 years) women treated with breast conserving surgery first Radiother Oncol. 2007. Mar;82(3):272–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Horton JK, Jagsi R, Woodward WA, et al. Breast Cancer Biology: Clinical Implications for Breast Radiation Therapy Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2018. Jan 1;100(1):23–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Toi M, Winer E, Benson J, et al. Personalized treatment of breast cancer. Japan: Springer; 2016. (Toi M, Winer E, Benson J, et al. , editors.). [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bouchardy C, Benhamou S, Fioretta G, et al. Risk of second breast cancer according to estrogen receptor status and family history Breast cancer research and treatment. 2011. May;127(1):233–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hall EJ, Giaccia AJ. Radiobiology for the Radiologist. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Voorwerk L, Slagter M, Horlings HM, et al. Publisher Correction: Immune induction strategies in metastatic triple-negative breast cancer to enhance the sensitivity to PD-1 blockade: the TONIC trial Nat Med. 2019. Jul;25(7):1175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Formenti SC, Demaria S. Combining radiotherapy and cancer immunotherapy: a paradigm shift J Natl Cancer Inst. 2013. Feb 20;105(4):256–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Emens LA. Breast cancer immunobiology driving immunotherapy: vaccines and immune checkpoint blockade Expert review of anticancer therapy. 2012. Dec;12(12):1597–611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Voorwerk L, Slagter M, Horlings HM, et al. Immune induction strategies in metastatic triple-negative breast cancer to enhance the sensitivity to PD-1 blockade: the TONIC trial Nat Med. 2019. Jun;25(6):920–928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Simmons CE, Brezden-Masley C, McCarthy J, et al. Positive progress: current and evolving role of immune checkpoint inhibitors in metastatic triple-negative breast cancer Therapeutic advances in medical oncology. 2020;12:1758835920909091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhang Y, Wang S, Yang B, et al. Adjuvant treatment for triple-negative breast cancer: a retrospective study of immunotherapy with autologous cytokine-induced killer cells in 294 patients Cancer biology & medicine. 2019. May;16(2):350–360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schwentner L, Wolters R, Koretz K, et al. Triple-negative breast cancer: the impact of guideline-adherent adjuvant treatment on survival--a retrospective multi-centre cohort study Breast cancer research and treatment. 2012. Apr;132(3):1073–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Byrd TT, Fousek K, Pignata A, et al. TEM8/ANTXR1-Specific CAR T Cells as a Targeted Therapy for Triple-Negative Breast Cancer Cancer research. 2018. Jan 15;78(2):489–500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mole RH. Whole body irradiation; radiobiology or medicine? Br J Radiol. 1953. May;26(305):234–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kleinovink JW, Fransen MF, Lowik CW, et al. Photodynamic-Immune Checkpoint Therapy Eradicates Local and Distant Tumors by CD8(+) T Cells Cancer immunology research. 2017. Oct;5(10):832–838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Eranki A, Srinivasan P, Ries M, et al. High-Intensity Focused Ultrasound (HIFU) Triggers Immune Sensitization of Refractory Murine Neuroblastoma to Checkpoint Inhibitor Therapy Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. 2020. Mar 1;26(5):1152–1161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Joosten JJ, Muijen GN, Wobbes T, et al. In vivo destruction of tumor tissue by cryoablation can induce inhibition of secondary tumor growth: an experimental study Cryobiology. 2001. Feb;42(1):49–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hu ZI, McArthur HL, Ho AY. The Abscopal Effect of Radiation Therapy: What Is It and How Can We Use It in Breast Cancer? Current breast cancer reports. 2017;9(1):45–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gupta GP, Massague J. Cancer metastasis: building a framework Cell. 2006. Nov 17;127(4):679–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Abuodeh Y, Venkat P, Kim S. Systematic review of case reports on the abscopal effect Current problems in cancer. 2016. Jan-Feb;40(1):25–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Demaria S, Kawashima N, Yang AM, et al. Immune-mediated inhibition of metastases after treatment with local radiation and CTLA-4 blockade in a mouse model of breast cancer Clinical Cancer Research. 2005. Jan 15;11(2):728–734. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Demaria S, Ng B, Devitt ML, et al. Ionizing radiation inhibition of distant untreated tumors (abscopal effect) is immune mediated Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2004. Mar 1;58(3):862–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Luen S, Virassamy B, Savas P, et al. The genomic landscape of breast cancer and its interaction with host immunity Breast. 2016. Oct;29:241–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Taylor C, Hershman D, Shah N, et al. Augmented HER-2 specific immunity during treatment with trastuzumab and chemotherapy Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. 2007. Sep 1;13(17):5133–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Musolino A, Naldi N, Bortesi B, et al. Immunoglobulin G fragment C receptor polymorphisms and clinical efficacy of trastuzumab-based therapy in patients with HER-2/neu-positive metastatic breast cancer J Clin Oncol. 2008. Apr 10;26(11):1789–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mohit E, Hashemi A, Allahyari M. Breast cancer immunotherapy: monoclonal antibodies and peptide-based vaccines Expert review of clinical immunology. 2014. Jul;10(7):927–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Muntasell A, Cabo M, Servitja S, et al. Interplay between Natural Killer Cells and Anti-HER2 Antibodies: Perspectives for Breast Cancer Immunotherapy Frontiers in immunology. 2017;8:1544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Arab A, Yazdian-Robati R, Behravan J. HER2-Positive Breast Cancer Immunotherapy: A Focus on Vaccine Development Archivum immunologiae et therapiae experimentalis. 2020. Jan 9;68(1):2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mittendorf EA, Clifton GT, Holmes JP, et al. Final report of the phase I/II clinical trial of the E75 (nelipepimut-S) vaccine with booster inoculations to prevent disease recurrence in high-risk breast cancer patients Ann Oncol. 2014. Sep;25(9):1735–1742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rosenberg SA, Yang JC, Restifo NP. Cancer immunotherapy: moving beyond current vaccines Nat Med. 2004. Sep;10(9):909–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Pilipow K, Darwich A, Losurdo A. T-cell-based breast cancer immunotherapy Seminars in cancer biology. 2021. Jul;72:90–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Swoboda A, Nanda R. Immune Checkpoint Blockade for Breast Cancer Cancer treatment and research. 2018;173:155–165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Nolan E, Savas P, Policheni AN, et al. Combined immune checkpoint blockade as a therapeutic strategy for BRCA1-mutated breast cancer Science translational medicine. 2017. Jun 7;9(393). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Gaynor N, Crown J, Collins DM. Immune checkpoint inhibitors: Key trials and an emerging role in breast cancer Seminars in cancer biology. 2020. Jul 2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Schmid P, Cortes J, Pusztai L, et al. Pembrolizumab for Early Triple-Negative Breast Cancer N Engl J Med. 2020. Feb 27;382(9):810–821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Cortes J, Rugo HS, Cescon DW, et al. Pembrolizumab plus Chemotherapy in Advanced Triple-Negative Breast Cancer N Engl J Med. 2022. Jul 21;387(3):217–226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Dewan MZ, Galloway AE, Kawashima N, et al. Fractionated but not single-dose radiotherapy induces an immune-mediated abscopal effect when combined with anti-CTLA-4 antibody Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. 2009. Sep 1;15(17):5379–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Pilones KA, Hensler M, Daviaud C, et al. Converging focal radiation and immunotherapy in a preclinical model of triple negative breast cancer: contribution of VISTA blockade Oncoimmunology. 2020;9(1). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Song HN, Jin H, Kim JH, et al. Abscopal Effect of Radiotherapy Enhanced with Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors of Triple Negative Breast Cancer in 4T1 Mammary Carcinoma Model International journal of molecular sciences. 2021. Sep 28;22(19). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Cao K, Abbassi L, Romano E, et al. Radiation therapy and immunotherapy in breast cancer treatment: preliminary data and perspectives Expert review of anticancer therapy. 2021. May 4;21(5):501–509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Tsoutsou PG, Zaman K, Martin Lluesma S, et al. Emerging Opportunities of Radiotherapy Combined With Immunotherapy in the Era of Breast Cancer Heterogeneity Frontiers in oncology. 2018;8:609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Vanpouille-Box C, Alard A, Aryankalayil MJ, et al. DNA exonuclease Trex1 regulates radiotherapy-induced tumour immunogenicity Nature communications. 2017. Jun 9;8:15618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Maity A, Mick R, Huang AC, et al. A phase I trial of pembrolizumab with hypofractionated radiotherapy in patients with metastatic solid tumours British journal of cancer. 2018. Nov;119(10):1200–1207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Theelen W, Peulen HMU, Lalezari F, et al. Effect of Pembrolizumab After Stereotactic Body Radiotherapy vs Pembrolizumab Alone on Tumor Response in Patients With Advanced Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer: Results of the PEMBRO-RT Phase 2 Randomized Clinical Trial JAMA oncology. 2019. Sep 1;5(9):1276–1282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Sugie T. [Today and future perspectives in breast cancer immunotherapy] Nihon rinsho Japanese journal of clinical medicine. 2012. Sep;70 Suppl 7:715–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Antonia SJ, Villegas A, Daniel D, et al. Overall Survival with Durvalumab after Chemoradiotherapy in Stage III NSCLC N Engl J Med. 2018. Dec 13;379(24):2342–2350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Dovedi SJ, Adlard AL, Lipowska-Bhalla G, et al. Acquired resistance to fractionated radiotherapy can be overcome by concurrent PD-L1 blockade Cancer research. 2014. Oct 1;74(19):5458–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Chen L, Douglass J, Kleinberg L, et al. Concurrent Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors and Stereotactic Radiosurgery for Brain Metastases in Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer, Melanoma, and Renal Cell Carcinoma Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2018. Mar 15;100(4):916–925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Markovsky E, Budhu S, Samstein RM, et al. An Antitumor Immune Response Is Evoked by Partial-Volume Single-Dose Radiation in 2 Murine Models Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2019. Mar 1;103(3):697–708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Kanagavelu S, Gupta S, Wu X, et al. In vivo effects of lattice radiation therapy on local and distant lung cancer: potential role of immunomodulation Radiat Res. 2014. Aug;182(2):149–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Brooks ED, Chang JY. Time to abandon single-site irradiation for inducing abscopal effects Nature reviews Clinical oncology. 2019. Feb;16(2):123–135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Mamounas EP, Tang G, Fisher B, et al. Association between the 21-gene recurrence score assay and risk of locoregional recurrence in node-negative, estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer: results from NSABP B-14 and NSABP B-20 J Clin Oncol. 2010. Apr 1;28(10):1677–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Scott JG, Berglund A, Schell MJ, et al. A genome-based model for adjusting radiotherapy dose (GARD): a retrospective, cohort-based study Lancet Oncol. 2017. Feb;18(2):202–211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Eschrich SA, Fulp WJ, Pawitan Y, et al. Validation of a radiosensitivity molecular signature in breast cancer Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. 2012. Sep 15;18(18):5134–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Goldstein DA, Gordon N, Davidescu M, et al. A Phamacoeconomic Analysis of Personalized Dosing vs Fixed Dosing of Pembrolizumab in Firstline PD-L1-Positive Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer J Natl Cancer Inst. 2017. Nov 1;109(11). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Grassberger C, Ellsworth SG, Wilks MQ, et al. Assessing the interactions between radiotherapy and antitumour immunity Nature Reviews Clinical Oncology. 2019. Dec;16(12):729–745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.O'Meara TA, Tolaney SM. Tumor mutational burden as a predictor of immunotherapy response in breast cancer Oncotarget. 2021. Mar 2;12(5):394–400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Goodman AM, Kato S, Bazhenova L, et al. Tumor Mutational Burden as an Independent Predictor of Response to Immunotherapy in Diverse Cancers Molecular cancer therapeutics. 2017. Nov;16(11):2598–2608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Chang L, Chang M, Chang HM, et al. Microsatellite Instability: A Predictive Biomarker for Cancer Immunotherapy Applied immunohistochemistry & molecular morphology : AIMM. 2018. Feb;26(2):e15–e21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Marcus L, Lemery SJ, Keegan P, et al. FDA Approval Summary: Pembrolizumab for the Treatment of Microsatellite Instability-High Solid Tumors Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. 2019. Jul 1;25(13):3753–3758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Dudley JC, Lin MT, Le DT, et al. Microsatellite Instability as a Biomarker for PD-1 Blockade Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. 2016. Feb 15;22(4):813–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Marcus L, Fashoyin-Aje LA, Donoghue M, et al. FDA Approval Summary: Pembrolizumab for the Treatment of Tumor Mutational Burden-High Solid Tumors Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. 2021. Sep 1;27(17):4685–4689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Fancello L, Gandini S, Pelicci PG, et al. Tumor mutational burden quantification from targeted gene panels: major advancements and challenges Journal for immunotherapy of cancer. 2019. Jul 15;7(1):183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Bonneville R, Krook MA, Chen HZ, et al. Detection of Microsatellite Instability Biomarkers via Next-Generation Sequencing Methods Mol Biol. 2020;2055:119–132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Rimm DL, Han G, Taube JM, et al. A Prospective, Multi-institutional, Pathologist-Based Assessment of 4 Immunohistochemistry Assays for PD-L1 Expression in Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer JAMA oncology. 2017. Aug 1;3(8):1051–1058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Larkin J, Chiarion-Sileni V, Gonzalez R, et al. Combined Nivolumab and Ipilimumab or Monotherapy in Untreated Melanoma N Engl J Med. 2015. Jul 2;373(1):23–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Balermpas P, Rodel F, Rodel C, et al. CD8+ tumour-infiltrating lymphocytes in relation to HPV status and clinical outcome in patients with head and neck cancer after postoperative chemoradiotherapy: A multicentre study of the German cancer consortium radiation oncology group (DKTK-ROG) Int J Cancer. 2016. Jan 1;138(1):171–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Balermpas P, Martin D, Wieland U, et al. Human papilloma virus load and PD-1/PD-L1, CD8(+) and FOXP3 in anal cancer patients treated with chemoradiotherapy: Rationale for immunotherapy Oncoimmunology. 2017;6(3):e1288331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Larkin J, Hodi FS, Wolchok JD. Combined Nivolumab and Ipilimumab or Monotherapy in Untreated Melanoma N Engl J Med. 2015. Sep 24;373(13):1270–1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Antonia SJ, Villegas A, Daniel D, et al. Durvalumab after Chemoradiotherapy in Stage III Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer N Engl J Med. 2017. Nov 16;377(20):1919–1929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Shklovskaya E, Rizos H. Spatial and Temporal Changes in PD-L1 Expression in Cancer: The Role of Genetic Drivers, Tumor Microenvironment and Resistance to Therapy International journal of molecular sciences. 2020. Sep 27;21(19). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.de Melo Gagliato D, Cortes J, Curigliano G, et al. Tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes in Breast Cancer and implications for clinical practice Bba-Rev Cancer. 2017. Dec;1868(2):527–537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Adams S, Gray RJ, Demaria S, et al. Prognostic value of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes in triple-negative breast cancers from two phase III randomized adjuvant breast cancer trials: ECOG 2197 and ECOG 1199 J Clin Oncol. 2014. Sep 20;32(27):2959–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Denkert C, Loibl S, Noske A, et al. Tumor-Associated Lymphocytes As an Independent Predictor of Response to Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy in Breast Cancer Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2010. Jan 1;28(1):105–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Loi S, Sirtaine N, Piette F, et al. Prognostic and predictive value of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes in a phase III randomized adjuvant breast cancer trial in node-positive breast cancer comparing the addition of docetaxel to doxorubicin with doxorubicin-based chemotherapy: BIG 02-98 J Clin Oncol. 2013. Mar 1;31(7):860–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Irelli A, Sirufo MM, D'Ugo C, et al. Sex and Gender Influences on Cancer Immunotherapy Response Biomedicines. 2020. Jul 21;8(7). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Nishijima TF, Muss HB, Shachar SS, et al. Comparison of efficacy of immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) between younger and older patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis Cancer Treat Rev. 2016. Apr;45:30–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Woodall MJ, Neumann S, Campbell K, et al. The Effects of Obesity on Anti-Cancer Immunity and Cancer Immunotherapy Cancers. 2020. May 14;12(5). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Deshpande RP, Sharma S, Watabe K. The Confounders of Cancer Immunotherapy: Roles of Lifestyle, Metabolic Disorders and Sociological Factors Cancers. 2020. Oct 15;12(10). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Guo B, Garrett L, Liu S. A Bayesian phase I/II design for cancer clinical trials combining an immunotherapeutic agent with a chemotherapeutic agent Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series C. 2021;70:1210–1229. [Google Scholar]

- 105.Guo B, Yuan Y. Bayesian phase I/II biomarker-based dose finding for precision medicine with molecularly targeted agents Journal of the American Statistical Association. 2017;112:508–520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Dieci MV, Guarneri V, Tosi A, et al. Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy and Immunotherapy in Luminal B-like Breast Cancer: Results of the Phase II GIADA Trial Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. 2022. Jan 15;28(2):308–317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Barroso-Sousa R, Krop IE, Trippa L, et al. A Phase II Study of Pembrolizumab in Combination With Palliative Radiotherapy for Hormone Receptor-positive Metastatic Breast Cancer Clinical breast cancer. 2020. Jun;20(3):238–245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]