Abstract

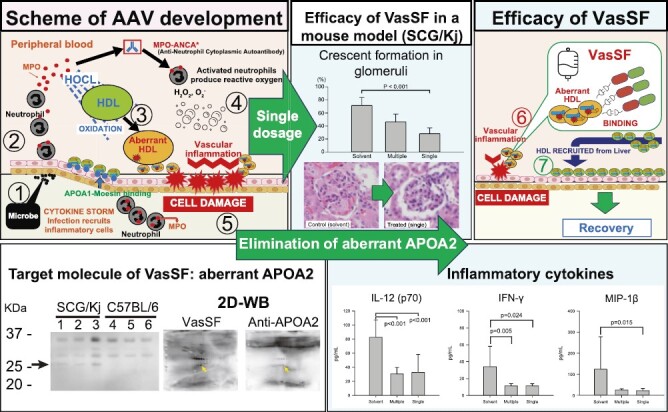

Based on the efficacy of intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIg) for the treatment of antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA)-associated vasculitis (AAV), we developed a recombinant single-chain-fragment variable clone, VasSF, therapeutic against AAV in a mouse model (SCG/Kj mice). VasSF is thought to bind to vasculitis-associated apolipoprotein A-II (APOA2) as a target molecule. VasSF is a promising new drug against AAV, but difficulties in the yield and purification of VasSF remain unresolved. We produced monomers of new VasSF molecules by modifying the plasmid structure for VasSF expression and simplifying the purification method using high-performance liquid chromatography. We compared the therapeutic effects between 5-day continuous administration of the monomers, as in IVIg treatment, and single shots of 5-day-equivalent doses. We also evaluated the life-prolonging effect of the single-shot treatment. Two-dimensional western blots were used to examine the binding of VasSF to APOA2. Our improved manufacturing method resulted in a 100-fold higher yield of VasSF than in our previous study. Monomerization of VasSF stabilized its efficacy. Single shots of a small amount (1/80 000 of IVIg) produced sufficient therapeutic effects, including decreased glomerular crescent formation, a decreasing trend of serum ANCA against myeloperoxidase (MPO-ANCA), decreases in multiple proinflammatory cytokines, and a trend toward prolonged survival. Two-dimensional western blots confirmed the binding of VasSF to APOA2. The newly produced pure VasSF monomers are stable and therapeutic for AAV with a single low-dose injection, possibly by removing vasculitis-associated APOA2. Thus, the new VasSF described herein is a promising drug against AAV.

Keywords: antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody-associated vasculitis (AAV), microscopic polyangiitis (MPA), antibody drug, apolipoprotein, SCG/Kj, VasSF

AAV is believed to develop with ANCA production after a cytokine storm caused by microbe infection. Here, we produced completely pure and stable monomers of VasSF and then demonstrated its efficacy with a single shot of a small amount: decreased glomerular crescent formation, MPO-ANCA, and proinflammatory cytokines. In addition, the VasSF-treated group tended to survive longer than the control group. Two-dimensional western blots confirmed the binding of VasSF to APOA2 (aberrant APOA2: aberrant HDL), indicating that VasSF would be a promising drug against AAV.

Graphical Abstract

Graphical Abstract.

Introduction

Blood-vessel injury secondary to dysregulation of activated neutrophils can cause antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA)-associated vasculitis (AAV) [1], such as microscopic polyangiitis (MPA). Major target antigens of ANCA are myeloperoxidase (MPO) and leukocyte proteinase 3. In Japan, the guidelines for treating severe vasculitis recommend steroids, immunosuppressive therapy, and antibody drugs such as rituximab [2, 3]. However, antibody drugs for treatment of vasculitis must be developed based on specific target molecules involved in the etiological mechanism of the disease. Avacopan, a C5a receptor (C5aR) inhibitor, has been recently approved as an alternative to steroids for treating vasculitis [4, 5]. However, C5aR inhibitors may be associated with a risk of infection because C5a is essential for neutrophil activation and defense during bacterial infection [6]. Intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIg) is effective for the treatment of vasculitis [7–11] but has some disadvantages as a biologic, such as high cost, short supply, the need for massive doses, and infection risk due to its human-blood origin. Therefore, both doctors and patients are anticipating the development of recombinant immunoglobulins as therapeutic drugs to overcome these disadvantages. In a previous study, by focusing on human immunoglobulin G (IgG) used for IVIg, we established a recombinant human single-chain IgG library consisting of 204 clones as a source of therapeutic drugs for vasculitis [12, 13]. We then developed VasSF, a clone with therapeutic activity against vasculitis, via selection from the library [12, 13]. To evaluate the efficacy of VasSF in the treatment of vasculitis, we employed our original therapeutic evaluation method [14] using a mouse model of vasculitis (spontaneous crescentic glomerulonephritis-forming/Kinjoh [SCG/Kj] mice) [15]. We proposed binding to vasculitis-associated apolipoprotein A-II (APOA2) as the therapeutic mechanism. We also found that VasSF could potentially improve the reproductive performance of SCG/Kj mice [16]. Thus, VasSF is a promising candidate drug for the treatment of vasculitis.

The practical application of VasSF as a therapeutic drug has been hampered by low manufacturing efficiency. For more efficient recombinant protein production in Escherichia coli, the signal sequence of the recombinant protein is generally modified or removed [17, 18]. Monomerization increases productivity, eliminates uncertainty associated with the diversity of the molecule, and facilitates quality control and determination of drug efficacy. Although we used a 5-day continuous dosing regimen similar to IVIg in our previous study [13], a single administration is preferable to decrease the burden on the patient. Furthermore, we had insufficient information on the binding of the drug to its putative target (APOA2) and a group of molecules related to APOA2. Clarification of the molecular biological mechanism is important when considering drug efficacy and safety.

The aims of this study were to develop a new procedure for formulation and administration of VasSF to improve the manufacturing process, simplify the administration protocol, and elucidate the kinetics of VasSF and its target molecules. For these purposes, we improved plasmid construction for recombinant protein expression, improved and simplified the formulation purification method, assured quality through monomerization and stabilization of molecules, improved and simplified the administration method, confirmed the life-prolonging effect of treatment, and confirmed VasSF binding with target molecules by one-dimensional western blot (1D-WB), two-dimensional fluorescence difference gel electrophoresis (2D-DIGE), and two-dimensional western blot (2D-WB).

Materials and methods

Production of new VasSF proteins (9nSU)

Expression and purification of subclone 9nSU

As shown in Supplementary Fig. S1, new plasmids (subclone 9nSU) were constructed by the removal of signals and His-tag sequences from existing plasmids (subclone URq01). Escherichia coli expressing 9nSU protein was cultured for 16 h at 37°C in lysogeny broth. The cells were harvested after centrifugation for 30 min at 4°C and treated with sonication for 10 min at room temperature. The pellet was solubilized by sonication and resuspended in 6 M guanidine hydrochloric acid solution containing 20 mM dithiothreitol and 1 mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid.

Separation and stability analysis of VasSF polymers and monomers

New VasSF proteins (9nSU) were separated by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) (Shimadzu Corporation, Kyoto, Japan) using a gel-filtration column (Shodex 803 + 804 column; Showa Denko, Tokyo, Japan). The purity of the 9nSU proteins was determined by sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE; 4–20% gel; stained by Coomassie Brilliant Blue, CBB) in combination with western blot using anti-human IgG-F(abʹ)2 and profiles of fractions eluted from the gel-filtration column in the HPLC system. The stability of the VasSF molecules was determined by the invariable retention times of the eluted fractions in HPLC.

Animals

The therapeutic effects of the new VasSF protein (9nSU) were evaluated using SCG/Kj mice as a mouse model for MPO-ANCA-associated vasculitis [15]. C57BL/6 mice were used as normal controls for the binding assay.

Evaluation of VasSF treatments in SCG/Kj mice

Guanidine was removed from the VasSF suspension by dialysis, and the VasSF proteins were resuspended in a solvent for injection (phosphate-buffered saline containing 15 mg/ml D-mannitol, 4.5 mg/ml glycine, and 0.4 M arginine).

Therapeutic effects of various doses of new VasSF (9nSU) in SCG/Kj mice

Four doses of 9nSU (0.01, 0.03, 0.1, and 0.3 mg/kg body weight [BW] once daily for 5 days) were administered intraperitoneally to 10-week-old SCG/Kj female mice, with the solvent group as the control. Three weeks later, kidneys and spleens were collected to examine the crescent-formation rates and spleen weight/BW ratios.

Therapeutic effects of polymers and monomers of new VasSF (9nSU) in SCG/Kj mice

Unseparated 9nSU (a mixture of polymers and monomers), polymers, and monomers (0.005 mg/kg BW once daily for 5 days) were administered intraperitoneally to 10-week-old SCG/Kj female mice, with the solvent group as the control. The urinary protein and occult blood scores of the mice were monitored for 3 weeks, and kidneys, spleens, and blood were then collected to determine the crescent-formation rates, spleen/BW ratios, and serum MPO-ANCA levels.

Therapeutic effects of multiple and single administrations of new VasSF (9nSU) in SCG/Kj mice

Three formulations of 9nSU monomer were administered to 10-week-old SCG/Kj female mice: 0.005 mg/kg BW per day for 5 days (multiple shots), 0.025 mg/kg BW only once (single shot), and solvent only (solvent group) as the control. Three weeks later, kidneys, spleens, lungs, and blood were collected to examine the histology of the three tissues, crescent-formation rates, spleen/BW ratios, blood cell counts, and serum levels of cytokines and chemokines.

Urinary protein and occult blood scores

Urinary protein and occult blood scores were measured by Uropaper III Eiken E-UR42 (Eiken Chemical Co. Ltd., Tokyo, Japan). The urinary protein score was 0, 1, 2, and 3 if the urinary protein concentration was < 30, 30–100 mg/dl, 101–300, and 301–1000 mg/dl, respectively. The occult blood score ranged from 0 (not detected) to 3 (high concentration).

Histopathology of kidneys, spleens, and lungs

Kidneys, spleens, and lungs were histopathologically examined by hematoxylin and eosin staining.

Crescent-formation rate

The crescent-formation rate (% crescents) was determined using 80–100 glomeruli on hematoxylin-and eosin-stained slides of kidney tissues.

Blood counts: white blood cells, lymphocytes, monocytes, granulocytes, and platelets

White blood cell, lymphocyte, monocyte, and granulocyte counts were measured using a VetScan HM2 Hematology Analyzer (Abaxis, Union City, CA, USA).

Measurement of serum MPO-ANCA level

Serum levels of MPO-ANCA were measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. The MPO-ANCA titers are shown as the equivalent of standard mouse anti-mouse MPO IgG [19].

Cytokines and chemokines

Multiplex immunoassays (Bio-Plex; Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) were used to measure the serum levels of 23 inflammatory cytokines and chemokines: interleukin (IL)-1α, IL-1β, IL-2, IL-3, IL-4, IL-5, IL-6, IL-9, IL-10, IL-12 (p40), IL-12 (p70), IL-13, IL-17, eotaxin, granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF), granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF), interferon (IFN)-γ, keratinocyte-derived chemokine, monocyte chemoattractant protein-1, macrophage inflammatory protein (MIP)-1α, MIP-1β, regulated on activation normal T-cell expressed and secreted (RANTES), and tumor necrosis factor-α.

Survival analysis of mice treated with single shots of 9nSu monomers

The mortality of SCG/Kj mice given 0.025 mg/kg BW of 9nSU monomers (single shot), or solvent only was monitored. For ethical reasons, the mice were euthanized when they showed severe weakness (day of euthanization = day of death).

Binding assays of VasSF and anti-APOA2 antibodies to serum proteins

Peroxidase conjugations of VasSF monomers and anti-APOA2 antibodies

VasSF monomers and anti-APOA2 antibodies (SAB1403558; Sigma–Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) were conjugated with horseradish peroxidase (HRP) using an Ab-10 Rapid Peroxidase Labeling Kit (Dojindo Laboratories, Kumamoto, Japan).

Removal of albumin and IgG from serum proteins

Albumin- and IgG-depleted serum proteins (AG-minus proteins) were prepared by removing albumin and IgG with Cibacron Blue-Agarose Beads (BioVision Inc., Waltham, MA, USA), and protein G (Sigma–Aldrich), respectively.

SDS–PAGE of AG-minus proteins

AG-minus proteins (approximately 5 μg/lane) from SCG/Kj and C57BL/6 mice were separated by SDS-PAGE under non-reducing conditions using NuPAGE Bis-Tris Gel (4–12%) and NuPAGE MES SDS Running Buffer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). Precision Plus Protein Unstained Protein Standard (Bio-Rad) was used as a molecular weight marker. The proteins in the gels were stained with SYPRO Ruby (Thermo Fisher Scientific), and the stained-gel image was photographed using an image scanner (FX Pro; Bio-Rad).

Binding assay with 1D-WB using HRP-VasSF monomers

As described above, AG-minus proteins (approximately 5 μg/lane) from SCG/Kj and C57BL/6 mice were separated by non-reducing SDS-PAGE. After electrotransfer of the proteins onto a polyvinylidene fluoride membrane (FluoroTrans W; Pall Life Sciences, Port Washington, NY, USA), proteins to which VasSF monomers could bind were visualized by treatment with HRP-conjugated VasSF monomers followed by chemiluminescence substrates (Pierce ECL Plus Western Blotting Substrate; Thermo Fisher Scientific). A chemiluminescent image was captured using an LAS-3000 Imaging System (Fujifilm, Tokyo, Japan).

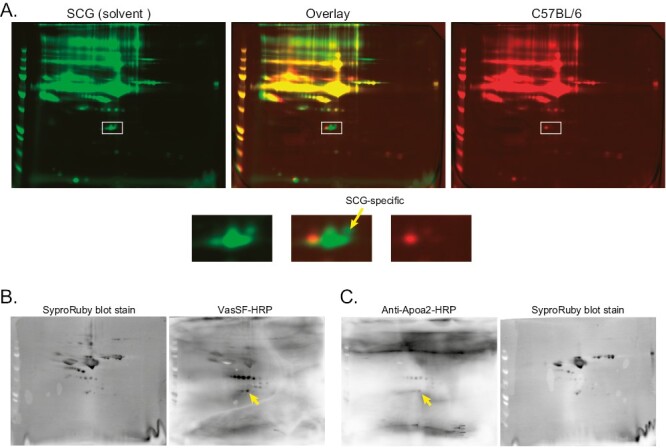

2D-DIGE search for strain-dependent differential proteins

AG-minus proteins from SCG/Kj and C57BL/6 mice were labeled with IC3-OSu and IC5-OSu (Dojindo Laboratories), respectively [20]. Proteins combined with fluorophore-labeled proteins from the two strains (~10 μg/strain) were separated by 2D electrophoresis under non-reducing conditions (first dimension: isoelectric focusing using immobilized pH gradient strips [pH 3–10; Bio-Rad]; second dimension: NuPAGE Bis–Tris Gel [4–12%] and NuPAGE MES SDS Running Buffer). Precision Plus All Blue Protein Standard (Bio-Rad) was used as a molecular weight marker. The fluorescent-gel images were photographed using an image scanner (FX Pro). Fluorescent-gel images of AG-minus proteins from SCG/Kj and C57BL/6 mice were shown with pseudo colors (green and red, respectively), and an overlay image was created using image-analysis software (Quantity One; Bio-Rad).

Binding assay with 2D-WB using HRP-VasSF monomers and HRP-anti-APOA2 antibodies

As described above, AG-minus proteins from SCG/Kj mice (~30 μg/strain) were separated by 2D electrophoresis under non-reducing conditions. Precision Plus All Blue Protein Standard (Bio-Rad) was used as a molecular weight marker. After electrotransfer of the proteins onto polyvinylidene fluoride membranes, the total proteins on the membranes were visualized by SYPRO Ruby Protein Blot Stain (Thermo Fisher Scientific), and the image was captured using an image scanner (FX Pro). The membranes were then treated with HRP-conjugated VasSF monomers or HRP-conjugated anti-APOA2 antibodies, followed by chemiluminescence substrates. The chemiluminescent images were captured using an LAS-3000 Imaging System.

Statistical analyses

Two-way repeated-measures ANOVA after rank transformation was used to test urinary protein and occult blood scores for significant differences between the treatment groups using SigmaPlot version 14 (Systat Software Inc., San Jose, CA, USA) because urinary protein and occult blood scores did not show normality over time. The other observed values were statistically analyzed using ANOVA, followed by the Holm–Sidak test if normality and equal variance were confirmed by the Shapiro–Wilk test and Brown–Forsythe test, respectively. Otherwise, statistical analyses were performed using the Kruskal–Wallis ANOVA by ranks followed by Dunn’s test. Survival times were compared using Kaplan–Meier analysis and the log-rank test. Differences were considered significant when P < 0.05.

Results

Production of new VasSF protein (9nSu)

With the new plasmids encoding neither signal peptides nor His-tags (Supplementary Fig. S1), and using our improved purification methods, we obtained ~16 mg of pure VasSF (9nSu) by 1-L culture of E. coli. The yield was approximately 100-fold higher than that obtained by VasSF production using the clone URq01 in our previous study [13].

Evaluation of VasSF treatments in SCG/Kj mice

Therapeutic effects of various doses of new VasSF (9nSU) in SCG/Kj mice

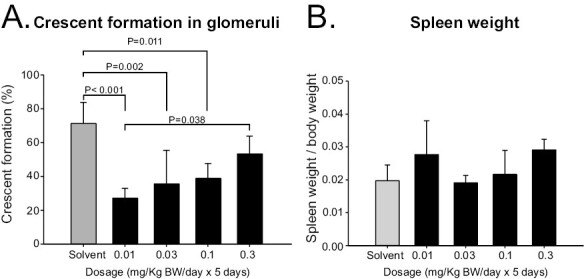

We evaluated the therapeutic effects of various doses of 9nSU (mixture of polymers and monomers) in SCG/Kj mice. We found significant dose dependency in the crescent-formation rate (P < 0.001 by ANOVA) (Fig. 1A) but not in the spleen weight/BW ratio (P = 0.08 by ANOVA) (Fig. 1B). We chose 0.005 mg/kg per day for five consecutive days as the treatment regimen for the subsequent experiments because 0.01 mg/kg per day was also effective.

Figure 1.

Crescent formation and spleen weight/BW ratio in SCG/Kj mice intraperitoneally administered various doses of new VasSF protein (9nSU). Various doses of new VasSF protein (9nSU) were intraperitoneally administered to SCG/Kj mice once daily for five consecutive days. SCG/Kj mice treated intraperitoneally with solvent alone served as controls. (A) Glomerular crescent-formation rates. (B) Spleen weight/BW ratios.

Therapeutic effects of polymers and monomers of new VasSF (9nSU) in SCG/Kj mice

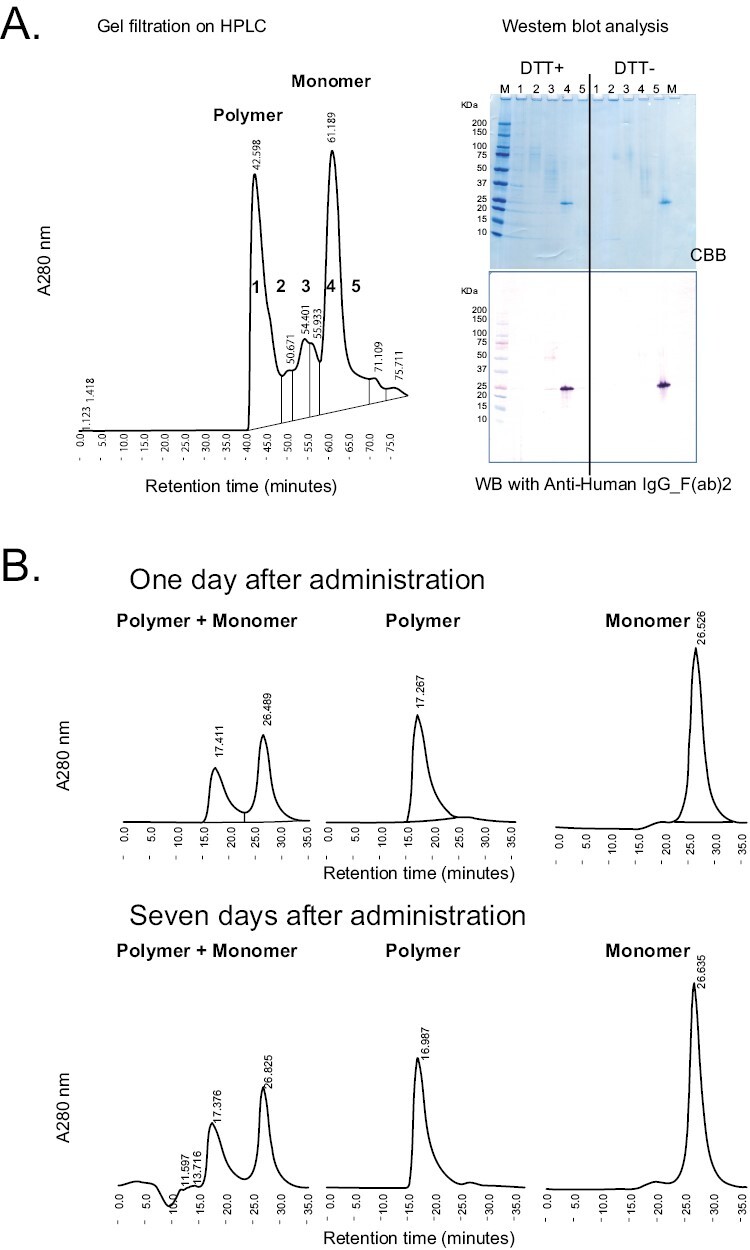

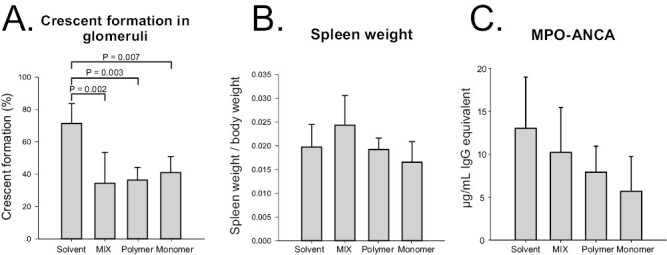

Because VasSF (9nSU) usually forms a mixture of monomers and polymers, we separated monomers and polymers from the mixture to eliminate molecular diversity and facilitate quality control and drug-efficacy determination. HPLC effectively separated the monomers from the polymers (Fig. 2A). The obtained polymers and monomers were stable for 7 days (Fig. 2B). Compared with the solvent, the unseparated (MIX) and the monomers tended to improve the mean change in urinary protein, but not occult blood, scores over time in SCG/Kj mice, although there was no statistically significant difference between the treatment groups (P = 0.166 and 0.348, respectively, in Tables 1 and 2). All VasSF-treated groups showed a significant reduction in the crescent-formation rate compared with the solvent group (P < 0.001 by ANOVA) (Fig. 3A), but not in the spleen weight/BW ratio (P = 0.166 by ANOVA) (Fig. 3B). The MPO-ANCA level tended to be lower in all VasSF-treated groups than in the solvent group (P = 0.289 by ANOVA) (Fig. 3C). By contrast, the monomers were stable and optimal for quality control, and we thus focused on the therapeutic effects of the monomers in the subsequent experiments.

Figure 2.

HPLC separation of polymers/monomers of new VasSF protein (9nSU). (A) HPLC elution pattern of polymers/monomers from 9nSU preparation. The separation of polymers and monomers was confirmed by SDS–PAGE, followed by WB with anti-human IgG-F(ab)2. The band of fraction four containing monomers under reducing conditions (dithiothreitol-positive) was the same size as the band under non-reducing conditions (dithiothreitol-negative). (B) Stability of new VasSF protein (9nSU). The HPLC elution patterns of unseparated mixtures, polymers, and monomers of new VasSF proteins (9nSU) at 7 days after administration (lower panel) were essentially the same as those after administration (upper panel)

Table 1.

Effect of new VasSF protein (9nSU) in unseparated (MIX), polymeric, and monomeric forms on urinary protein scores in SCG/Kj mice

| Days after treatment | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group | 0 | 4 | 7 | 14 | 17 | 21 |

| Solvent (8) | 2.1 ± 1.2 | 2.5 ± 1.1 | 2.3 ± 0.7 | 2.5 ± 0.9 | 2.5 ± 1.1 | 1.8 ± 1.2 |

| MIX (4) | 2.3 ± 0.5 | 2.0 ± 0.8 | 1.1 ± 0.6 | 1.8 ± 1.0 | 1.8 ± 0.5 | 1.0 ± 0.0 |

| Polymer (4) | 1.8 ± 0.5 | 1.8 ± 0.5 | 1.5 ± 0.6 | 3.0 ± 0.8 | 2.5 ± 0.6 | 1.3 ± 0.5 |

| Monomer (4) | 1.8 ± 0.5 | 2.0 ± 0.8 | 1.0 ± 0.0 | 2.0 ± 0.0 | 1.5 ± 0.6 | 2.0 ± 0.8 |

Values are presented as mean ± standard deviation. The number of mice observed is shown in parentheses.

Table 2.

Effect of new VasSF protein (9nSU) in unseparated (MIX), polymeric, and monomeric forms on occult blood scores in SCG/Kj mice

| Days after treatment | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group | 0 | 4 | 7 | 14 | 17 | 21 |

| Solvent (8) | 0.9 ± 1.6 | 0.8 ± 1.4 | 0.1 ± 0.2 | 1.6 ± 1.6 | 0.5 ± 1.4 | 0.9 ± 1.5 |

| MIX (4) | 1.0 ± 1.4 | 1.5 ± 1.3 | 0.3 ± 0.3 | 1.0 ± 0.8 | 1.5 ± 1.3 | 0.5 ± 0.4 |

| Polymer (4) | 1.5 ± 0.6 | 1.5 ± 1.3 | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 2.3 ± 1.0 | 1.8 ± 1.0 | 0.5 ± 1.0 |

| Monomer (4) | 0.5 ± 1.0 | 1.8 ± 2.1 | 0.3 ± 0.3 | 0.6 ± 0.9 | 1.5 ± 1.0 | 1.0 ± 1.4 |

Values are presented as mean ± standard deviation. The number of mice observed is shown in parentheses.

Figure 3.

Effects of new VasSF protein (9nSU) in unseparated, polymeric, and monomeric forms in SCG/Kj mice. Unseparated 9nSU (MIX), polymer only, and monomer only were administered intraperitoneally to SCG/Kj mice at a dose of 0.005 mg/kg BW per day once daily for five consecutive days. SCG/Kj mice treated intraperitoneally with solvent served as controls. (A) Glomerular crescent-formation rates. (B) Spleen weight/BW ratios. (C) Serum MPO-ANCA concentrations

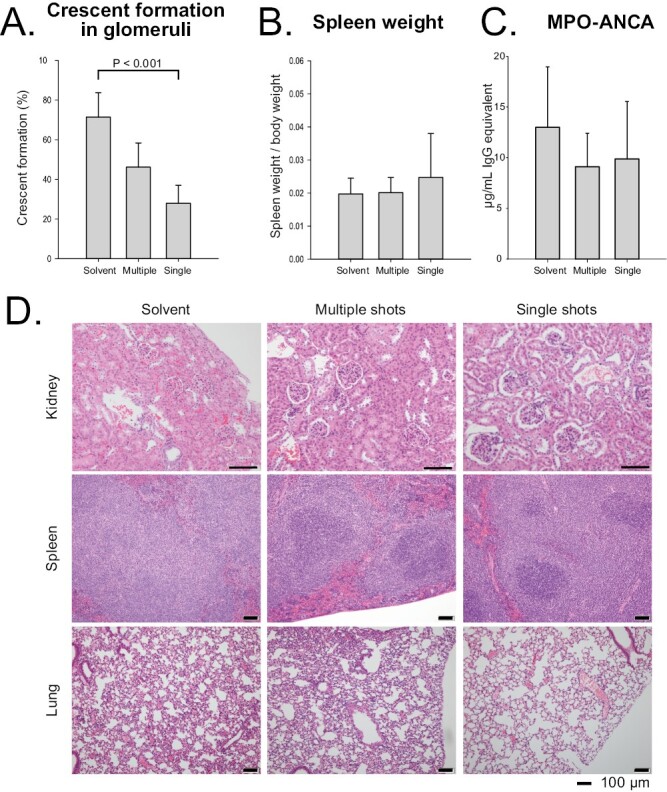

Therapeutic effects of multiple and single administrations of new VasSF (9nSU) in SCG/Kj mice

Using the 9nSU monomers, we compared the efficacy of two administration methods: multiple shots (0.005 mg/kg for five consecutive days) and a single shot (0.025 mg/kg). The dosages of monomers were set so that the total amounts would be identical. Compared with the solvent group, the single shots significantly decreased the crescent-formation rates in SCG/Kj mice (P < 0.001) (Fig. 4A). There was no statistically significant difference in the spleen weight/BW ratio among the three groups (P = 0.829 by ANOVA) (Fig. 4B). Both multiple and single shots reduced tissue damage in the kidneys, spleens, and lungs compared with the solvent group (Fig. 4D). As shown by the crescent-formation rates in Fig. 4A, more normal glomeruli were found in VasSF-treated kidneys, especially those treated with single shots, than in solvent-treated kidneys. Microscopic observations indicated that the white and red pulp were clearly separated in VasSF-treated spleens, unlike in the solvent group. The lungs in the single-shot group recovered more fully to normal lung tissue compared with those in the other two groups. The blood levels of 9 of the 23 cytokines measured were significantly reduced by VasSF compared with those in the solvent group (P values by ANOVA are shown in parentheses; post hoc tests are shown in Fig. 5): GM-CSF (P = 0.025), IL-2 (P = 0.027), IL-4 (P = 0.002), IL-6 (P = 0.018), IL-12 (p70) (P < 0.001), IL-9 (P = 0.001), IL-17 (P = 0.001), INF-γ (P = 0.003), and MIP-1β (P = 0.017). Compared with the solvent group, GM-CSF, IL-2, and IL-9 levels were significantly different in the multiple-shot group; IL-6 and MIP-1β levels were significantly different in the single-shot group; and IL-7, IL-12(p70), IFN-γ, and IL-4 levels were significantly different in both the multiple- and single-shot groups. There were no significant changes in the levels of the other 14 cytokines: eotaxin (P = 0.653), G-CSF (P = 0.137), IL-1α (P = 0.260), IL-1β (P = 0.431), IL-3 (P = 0.237), IL-5 (P = 0.088), IL-10 (P = 0.066), IL-12 (p40) (P = 0.077), IL-13 (P = 0.158), keratinocyte-derived chemokine (P = 0.052), monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (P = 0.064), MIP-1α (P = 0.176), RANTES (P = 0.669), or tumor necrosis factor-α (P = 0.062). With respect to the blood cell counts, the platelet count was elevated in the multiple-shot group compared with the solvent group (P = 0.014), but there was no significant difference in white blood cell, granulocyte, lymphocyte, or monocyte counts (P = 0.952, 0.239, 0.779, and 0.534, respectively, by ANOVA).

Figure 4.

Effects of multiple and single shots of 9nSU monomers in SCG/Kj mice. VasSF monomers were intraperitoneally administered to SCG/Kj mice at a dose of 0.005 mg/kg BW per day five times daily (multiple shots) or at a single dose of 0.025 mg/kg BW (single shot). SCG/Kj mice treated intraperitoneally with solvent alone were used as controls. (A) Glomerular crescent-formation rates. (B) Spleen weight/BW ratios. (C) Serum MPO-ANCA concentrations. (D) Histopathologic observations

Figure 5.

Effects of multiple and single shots of 9nSU monomers on serum cytokines/chemokines in SCG/Kj mice. Serum cytokines/chemokines were measured in three groups of SCG/Kj mice (multiple shots, single shots, and controls; see Fig. 4). Of 23 cytokines/chemokines measured, 9 showed significant differences among the three groups by ANOVA. All values are expressed as mean ± standard deviation

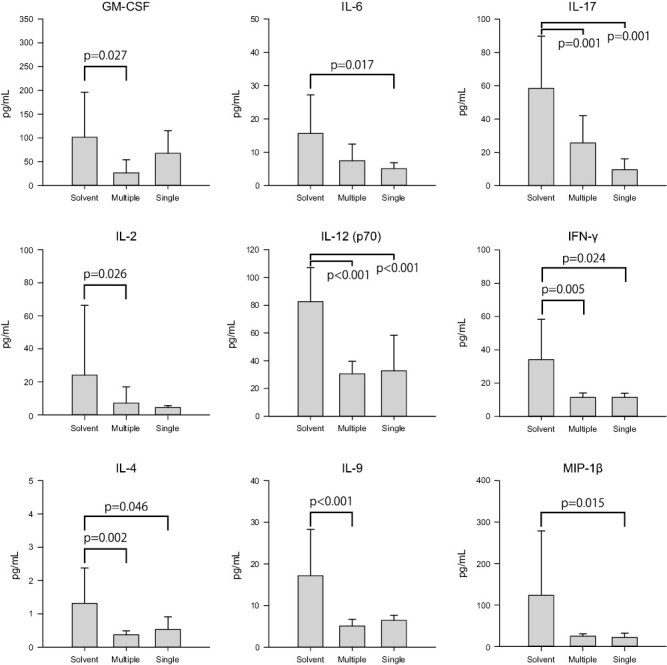

Survival analysis in mice treated with single shots of 9nSu monomers

SCG/Kj mice treated with single shots of 9nSU monomers tended to survive longer than mice treated with solvent only (P = 0.278 by log-rank test) (Fig. 6).

Figure 6.

Effect of single shots of 9nSU monomers on survival times in SCG/Kj mice. The mortality of SCG/Kj mice after single shots of 9nSU monomers or solvent only was compared by Kaplan–Meier analysis and the log-rank test. Mice treated with 9nSU monomers tended to survive longer than those treated with solvent only (P = 0.278).

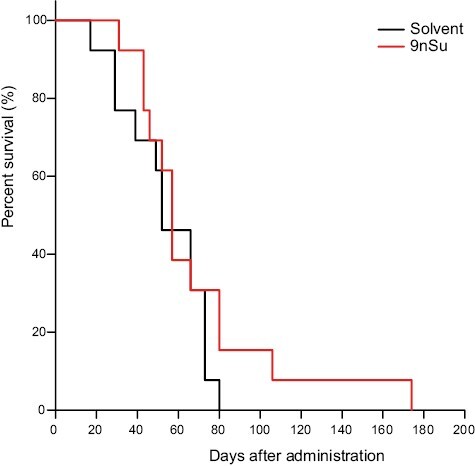

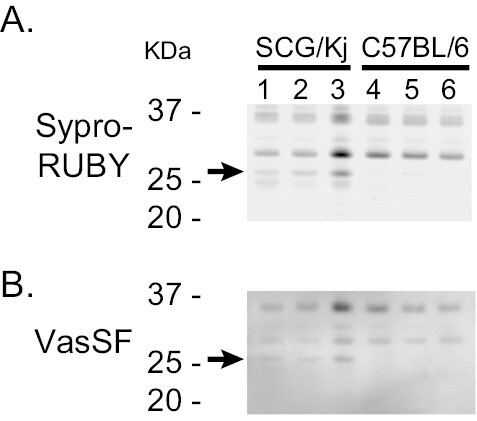

Binding assays of VasSF and anti-APOA2 antibodies to serum proteins

Binding assays of VasSF to serum proteins by 1D-WB (Fig. 7) showed ~26-kDa SCG/Kj-specific bands (arrows) in untreated mice (solvent group) and VasSF-treated mice, but not in normal control mice (C57BL/6N).

Figure 7.

Binding assay of VasSF to serum proteins. Albumin and IgG of serum protein samples from SCG/Kj and C57BL/6 mice were depleted in advance (AG-minus proteins). (A) SYPRO Ruby-stained gel image of AG-minus proteins (~5 μg/lane) after non-reducing SDS-PAGE. (B) AG-minus proteins to which HRP-conjugated VasSF could bind were visualized after non-reducing SDS–PAGE followed by WB. Note that the ~26-kDa bands (arrows) bound to VasSF monomers were present only in SCG/Kj mice.

In 2D-DIGE (Fig. 8A), one SCG/Kj-specific spot was observed (isoelectric point: ~6.2, molecular weight: approximately 26 kDa). The spots were bound to both VasSF monomers and anti-APOA2 antibodies in 2D-WB (Fig. 8B and C), indicating that one target of VasSF was APOA2. In addition, some other spots that bound to VasSF but either did not bind or bound only weakly to anti-APOA2 antibodies were present adjacent to the spot that bound anti-APOA2 antibodies.

Figure 8.

2D electrophoresis analysis of VasSF-binding serum proteins. The SCG/Kj-specific VasSF-binding serum proteins at ~26 kDa shown in Fig. 7B were further analyzed by 2D electrophoresis with AG-minus proteins. (A) 2D-DIGE of SCG/Kj and C57BL/6 AG-minus proteins with pseudocolor green and red, respectively, revealed an SCG/Kj-specific protein spot at approximately 26 kDa (arrow in the lower panels, which are enlarged images of the squares in the upper panels). Both HRP-VasSF and HRP-anti-APOA2 antibodies bound to the same spot in 2D-WB with SCG/Kj mice (arrows in B and C, respectively), indicating that VasSF bound to the serum APOA2 in SCG/Kj mice.

Discussion

Our study established a new formulation of VasSF (9nSu) that was stable and effective in treating vasculitis in an SCG/Kj mouse model at lower and less-frequent (single) doses than in our previous study [13]. These properties were due to improvements in the composition and manufacturing process of VasSF, which increased the yield of VasSF and enabled us to obtain high-purity monomers. In addition, the binding of VasSF to the target molecule (APOA2) was reconfirmed by 2D protein analyses. Thus, the new VasSF formulation (9nSu) is promising for practical use as a therapeutic agent for human vasculitis.

Modification of the expression plasmid structure (removal of the His-tag and signal peptide) and improvement of the purification method (less precipitation associated with plasmid improvement, which simplified the purification method) resulted in a 100-fold increase in the yield of new VasSF proteins compared with old VasSF proteins [13]. To meet the requirements for druggability of recombinant proteins, the His-tag should not be contained in the proteins [21]. His-tagged proteins tend to aggregate more than non-His-tagged proteins [22]. In some cases, the His-tag interferes with the biological properties of recombinant proteins. The C-terminal His-tag on some single-chain fragment variables (scFv) adversely affects their binding properties [23]. In one study, the presence of the His-tag at the amino terminus of some enzymes decreased their enzymatic activity compared with their non-His-tagged counterparts [24]. In another study, the His-tag induced structural and biochemical changes in higher-order oligomerization of membrane proteins [25]. Removal of signal peptides can induce higher-yield production of human-secreted proteins in E. coli [26]. Thus, we achieved simple and efficient production of new VasSF proteins by applying our new production protocol.

The new formulation of VasSF (9nSu) was effective in treating vasculitis in our SCG/Kj mouse model at lower doses (Fig. 1) than in our previous study [13]. The greater effect at lower concentrations may be attributed to the increased binding activity to vasculitis-associated APOA2 per unit mass due to structural improvements in the formulation and increased purification. The therapeutic effect decreased at higher concentrations, although VasSF was not toxic. These observations imply that VasSF removes vasculitis-associated APOA2 specifically and efficiently even at low concentrations, but the effect decreases at higher concentrations because of the increased percentage of non-specific binding to proteins other than those of vasculitis-associated APOA2 as a target protein. Efficacy at low doses is a general trend for scFv [27]. Considering the possibility that even lower doses might further enhance the therapeutic effect, we used a very low dose of 0.005 mg/kg (five doses) in later experiments.

VasSF monomers obtained by HPLC purification (Fig. 2) showed a better therapeutic effect compared to polymers (Fig. 3). Polymers are not suitable for drug manufacturing and quality control because the number of monomer molecules cannot be determined (di- tri-, tetra-, penta-, etc.). Monomers were used for subsequent study of the administration method because their quality and substance stability were easy to control and because their therapeutic effect was clearer than that of the polymers (especially the urinary protein score).

The new VasSF formulation was more therapeutic with a simpler single-shot method of administration than with a multiple-shot method (Fig. 4). Tissue healing was particularly pronounced with the single shot. In addition, 9 of the 23 inflammatory cytokines/chemokines measured significantly decreased (Fig. 5), showing that VasSF treatment markedly improved the serum cytokine/chemokine profiles in SCG/Kj mice: inflammation (IL-6 and IL-17), cellular immunity (IFN-γ, IL-2, and IL-12), antibody production/allergy reaction (IL-4), stimulation of blood cell proliferation (GM-CSF, and IL-9), and chemotactic stimuli (MIP-1β). In particular, the decrease in serum IL-12 levels by VasSF is considered important as a therapeutic effect because the pathophysiology has been associated with high plasma IL-12 levels in patients with MPA [28] and Takayasu arteritis [29]. Treatment of Kawasaki disease with IVIg was initially problematic because of the high patient burden caused by the need for repeated administration [7, 30], but in recent years, single-shot administration has become the standard of care [31]. The new VasSF also has the advantage of being administered as a single shot and can be expected to be highly effective if applied to human clinical use. In patients with rapidly developing vasculitis, drugs that act only at that point are more effective and reduce the incidence of side effects. In general, scFv have a short half-life (< 1 h in mice [32]) and are more rapidly cleared from the body than whole antibodies. Therefore, side effects of scFv are expected to be less severe. Although not statistically significant, the survival curve in this study showed a trend toward a delay in the onset of disease immediately after inoculation (Fig. 6). For patients with Kawasaki disease, high-dose IVIg treatment (standard single-dose method) is effective only in the early stages of disease onset (within 10 days) [33], which may be related to the fact that the new VasSF was effective in the early phase of vasculitis in SCG/Kj mice.

Our binding assays (Figs. 7 and 8) reconfirmed that VasSF specifically binds APOA2, a component of high-density lipoprotein (HDL), as shown in our previous study [13]. This finding confirms that APOA2 plays a pivotal role in the etiology of vasculitis. The involvement of APOA2 in vasculitis was also implied by the beneficial effect of anti-APOA2 in an animal model of coronary arteritis in Kawasaki disease [34]. Mouse APOA2 proteins exist in plasma exclusively as monomers (~10 kDa) because of the absence of a cysteine residue at position 6 [35]. However, in SCG/Kj, an AAV mouse model, the apparent molecular weight of accumulated plasma APOA2 was ~26 kDa, suggesting the AAV-related modification of APOA2 (production of aberrant APOA2). In addition, although the major target of VasSF is aberrant APOA2, the 2D-WB results imply that some other molecules that weakly interact with VasSF are present in SCG/Kj mouse serum (Fig. 8). More molecular species would interact with VasSF if higher doses of VasSF were used. This may explain why higher doses of VasSF reduced the effect on aberrant APOA2 in HDL and thus weakened the therapeutic effect (Fig. 1).

Vasculitis drugs that can achieve an anti-inflammatory effect without immunosuppression are preferable because immunosuppressive drugs can have an anti-inflammatory effect while also posing a risk of infection. For example, Avacopan (a C5aR inhibitor), a drug approved for vasculitis [4, 5], suppresses C5aR, which is one of the molecules involved in infection, inflammation, and immunity. Therefore, excessive suppression by Avacopan may increase the risk of infection. Another approved drug, rituximab [2, 3], is also an anticancer and immunosuppressive agent; thus, the use of rituximab also carries a risk of infection [36, 37]. By contrast, VasSF is promising as a safer treatment because its main target is aberrant APOA2, which is less involved in the immune response, and the risk of infection is considered low. In fact, less than half of the cytokines/chemokines tested in this study were affected by VasSF (Fig. 5). In addition, scFv drugs such as VasSF have the advantage of low overreaction and low antibody-induced side effects because the drugs act only on acute inflammation (e.g. AAV) and disappear quickly because of their rapid turnover. Possible mechanisms for the development of AAV and the treatment of VasSF include the following (Supplementary Fig. S2). Within blood vessels, HDLs cover the surface of the endothelial cells by APOA1–moesin binding [38]. Activation of neutrophils by viral/bacterial infection and/or genetic factors releases MPO [39], and antibodies to MPO (MPO-ANCA) are thought to be produced slowly [40]. Much later, neutrophils are reactivated by bacteria or viruses, and excess MPO produces hypochlorous acid [41], converting normal HDL to aberrant HDL by the formation of APOA1–APOA2 heterodimers [42]. At the same time, MPO is exposed on the surface of neutrophils [40], producing high numbers of reactive oxygen species [43] and possibly damaging endothelial cells. This epithelial cell damage leads to vasculitis. In the kidney, endothelial cell damage in the glomerular capillaries causes leakage of blood components into Bowman’s space, resulting in the formation of glomerular crescents [44]. We hypothesize that VasSF eliminates the damaging effects of aberrant HDL by capturing APOA2 within aberrant HDL and promoting endothelial cell restoration by normal HDL supplied by the liver, thereby curing vasculitis. As a result, the glomerular crescent formation caused by vasculitis in the kidney decreases and the glomerulonephritis resolves. Thus, VasSF is a therapeutic candidate that acts directly on the pathogenic mechanism of vasculitis, rather than suppressing inflammation by immunosuppression after its onset, and is expected to be a drug with a low risk of infection and side effects when used clinically.

The improved VasSF produced in this study was therapeutic at low doses and with a single administration, making it a promising candidate for the treatment of vasculitis. As a next step, we intend to conduct preclinical studies for human application and search for targets of VasSF in the sera of patients with vasculitis, such as AAV.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank Ms. Hiroko Urahama (NIBIOHN) for her help in preparing the manuscript. We also thank Prof. Wako YUMURA (Tohoku Medical and Pharmaceutical University), Dr. Yoshitomo HAMANO (Juntendo University Graduate School of Medicine), and Dr. Shunsuke FURUTA (Rheumatology, Chiba University Hospital) for their advice and expertise.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- 1D-WB

one-dimensional western blot

- 2D-DIGE

two-dimensional fluorescence difference gel electrophoresis

- 2D-WB

two-dimensional western blot

- AAV

antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody-associated vasculitis

- AG-minus proteins

albumin- and IgG-depleted serum proteins

- ANCA

antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody

- APOA2

apolipoprotein A-II

- BW

body weight

- C5aR

C5a receptor

- G-CSF

granulocyte colony-stimulating factor

- GM-CSF

granulocyte–macrophage colony-stimulating factor

- HDL

high-density lipoprotein

- HPLC

high-performance liquid chromatography

- HRP

horseradish peroxidase

- IFN

interferon

- IgG

immunoglobulin G

- IVIg

intravenous immunoglobulin

- MIP

macrophage inflammatory protein

- MPA

microscopic polyangiitis

- MPO

myeloperoxidase

- RANTES

regulated on activation normal T-cell expressed and secreted

- scFv

single-chain fragment variables

- SDS–PAGE

sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis

Contributor Information

Minako Koura, Laboratory of Animal Models for Human Diseases, National Institutes of Biomedical Innovation, Health and Nutrition (NIBIOHN), 7-6-8 Saito-Asagi, Ibaraki City, Osaka, Japan.

Yosuke Kameoka, Department of Research and Development, A-CLIP Institute, Chyuo-ku, Chiba City, Chiba, Japan.

Fukuko Kishi, Department of Research and Development, A-CLIP Institute, Chyuo-ku, Chiba City, Chiba, Japan.

Yoshio Yamakawa, Department of Research and Development, A-CLIP Institute, Chyuo-ku, Chiba City, Chiba, Japan.

Fuyu Ito, Laboratory of Infectious Diseases, Asia International Institute of Infectious Disease Control, Teikyo University, Itabashi-ku, Tokyo, Japan.

Ryuichi Sugamata, Laboratory of Infectious Diseases, Asia International Institute of Infectious Disease Control, Teikyo University, Itabashi-ku, Tokyo, Japan.

Yuko Doi, Laboratory of Animal Models for Human Diseases, National Institutes of Biomedical Innovation, Health and Nutrition (NIBIOHN), 7-6-8 Saito-Asagi, Ibaraki City, Osaka, Japan.

Kazuko Uno, Interferon & Host-defense Laboratory, Louis Pasteur Center for Medical Research, Sakyo-ku, Kyoto, Japan.

Toshinori Nakayama, Department of Allergy and Clinical Immunology, Chiba University Graduate School of Medicine, Chuo-ku, Chiba, Chiba, Japan.

Takashi Miki, Division of Co-creative Research in Disaster Therapeutics, Chiba University Research Institute of Disaster Medicine, Chuo-ku, Chiba City, Chiba, Japan.

Hiroshi Nakajima, Department of Allergy and Clinical Immunology, Chiba University Graduate School of Medicine, Chuo-ku, Chiba, Chiba, Japan.

Kazuo Suzuki, Department of Research and Development, A-CLIP Institute, Chyuo-ku, Chiba City, Chiba, Japan; Interferon & Host-defense Laboratory, Louis Pasteur Center for Medical Research, Sakyo-ku, Kyoto, Japan; Division of Co-creative Research in Disaster Therapeutics, Chiba University Research Institute of Disaster Medicine, Chuo-ku, Chiba City, Chiba, Japan.

Osamu Suzuki, Laboratory of Animal Models for Human Diseases, National Institutes of Biomedical Innovation, Health and Nutrition (NIBIOHN), 7-6-8 Saito-Asagi, Ibaraki City, Osaka, Japan.

Ethical approval

All animal experiments followed the guidelines of the National Institutes of Biomedical Innovation, Health and Nutrition, Osaka, Japan (authorization number: DS25-60).

Conflict of interests

The authors have no conflicts of interest requiring disclosure.

Funding

This study was supported in part by grants-in-aid from the Gamma Globulin Projects from the Ministry of Health, Welfare and Labour, Japan and a grant from the Gamma Globulin Project from the Japan Science and Technology Agency and the Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development in Japan.

Data availability

All data are incorporated into the article and its online supplementary material.

Author contributions

M.K.: conceptualization, investigation, data curation, and resources. Y.K.: methodology, investigation, and resources. F.K.: methodology, investigation, and resources. Y.Y.: methodology, investigation, and resources. F.I.: investigation. R.S.: data curation, and formal analysis. Y.D.: investigation, and resources. K.U.: investigation. T.N.: methodology, and writing-review and editing. T.M.: methodology. H.N.: methodology. K.S.: conceptualization, funding acquisition, investigation, data curation, methodology, visualization, writing-review and editing. O.S.: conceptualization, investigation, data curation, methodology, formal analysis, visualization, writing—original draft, and writing-review and editing.

References

- 1. Alba MA, Jennette JC, Falk RJ.. Pathogenesis of ANCA-associated pulmonary vasculitis. Semin Respir Crit Care Med 2018, 39, 413–24. doi: 10.1055/s-0038-1673386 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Jones RB, Tervaert JW, Hauser T, Luqmani R, Morgan MD, Peh CA, et al. Rituximab versus cyclophosphamide in ANCA-associated renal vasculitis. N Engl J Med 2010, 363, 211–20. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0909169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Stone JH, Merkel PA, Spiera R, Seo P, Langford CA, Hoffman GS, et al. Rituximab versus cyclophosphamide for ANCA-associated vasculitis. N Engl J Med 2010, 363, 221–32. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0909905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Jayne DRW, Bruchfeld AN, Harper L, Schaier M, Venning MC, Hamilton P, et al. Randomized trial of C5a receptor inhibitor avacopan in ANCA-associated vasculitis. J Am Soc Nephrol 2017, 28, 2756–67. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2016111179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Tesar V, Hruskova Z.. Avacopan in the treatment of ANCA-associated vasculitis. Expert Opin Investig Drugs 2018, 27, 491–6. doi: 10.1080/13543784.2018.1472234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Guo RF, Ward PA.. Role of C5a in inflammatory responses. Annu Rev Immunol 2005, 23, 821–52. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.23.021704.115835 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Furusho K, Kamiya T, Nakano H, Kiyosawa N, Shinomiya K, Hayashidera T, et al. High-dose intravenous gammaglobulin for Kawasaki disease. Lancet 1984, 2, 1055–8. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(84)91504-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Jayne DR, Chapel H, Adu D, Misbah S, O’Donoghue D, Scott D, et al. Intravenous immunoglobulin for ANCA-associated systemic vasculitis with persistent disease activity. QJM 2000, 93, 433–9. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/93.7.433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ito-Ihara T, Ono T, Nogaki F, Suyama K, Tanaka M, Yonemoto S, et al. Clinical efficacy of intravenous immunoglobulin for patients with MPO-ANCA-associated rapidly progressive glomerulonephritis. Nephron Clin Pract 2006, 102, c35–42. doi: 10.1159/000088313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Gopaluni S, Jayne D.. Clinical trials in vasculitis. Curr Treatm Opt Rheumatol 2016, 2, 161–77. doi: 10.1007/s40674-016-0045-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Shimizu T, Morita T, Kumanogoh A.. The therapeutic efficacy of intravenous immunoglobulin in anti-neutrophilic cytoplasmic antibody-associated vasculitis: a meta-analysis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2020, 59, 959–67. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kez311 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kameoka Y, Koura M, Matsuda J, Suzuki O, Ohno N, Nakayama T, et al. Establishment of a library having 204 effective clones of recombinant single chain fragment of variable region (hScFv) of IgG for vasculitis treatment. ADC Lett Infect Dis Control 2017, 4, 44–7. doi: 10.20814/adc.4.2_pp44. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kameoka Y, Kishi F, Koura M, Yamakawa Y, Nagasawa R, Ito F, et al. Efficacy of a recombinant single-chain fragment variable region, VasSF, as a new drug for vasculitis. Drug Des Devel Ther 2019, 13, 555–68. doi: 10.2147/DDDT.S188651 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Tomizawa K, Nagao T, Kusunoki R, Saiga K, Oshima M, Kobayashi K, et al. Reduction of MPO-ANCA epitopes in SCG/Kj mice by 15-deoxyspergualin treatment restricted by IgG2b associated with crescentic glomerulonephritis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2010, 49, 1245–56. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keq087 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kinjoh K, Kyogoku M, Good RA.. Genetic selection for crescent formation yields mouse strain with rapidly progressive glomerulonephritis and small vessel vasculitis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1993, 90, 3413–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.8.3413 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Koura M, Doi Y, Kishi F, Kameoka Y, Yamakawa Y, Nagasawa R, et al. VasSF treatment increased the number of pup deliveries per female in SCG/Kj mice. ADC Lett Infect Dis Control 2021, 8, 33–5. doi: 10.20814/adc.8.1_33. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Bird RE, Hardman KD, Jacobson JW, Johnson S, Kaufman BM, Lee SM, et al. Single-chain antigen-binding proteins. Science 1988, 242, 423–6. doi: 10.1126/science.3140379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Buchner J, Rudolph R.. Routes to active proteins from transformed microorganisms. Curr Opin Biotechnol 1991, 2, 532–8. doi: 10.1016/0958-1669(91)90077-i [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Suzuki K, Nagao T, Itabashi M, Hamano Y, Sugamata R, Yamazaki Y, et al. A novel autoantibody against moesin in the serum of patients with MPO-ANCA-associated vasculitis. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2014, 29, 1168–77. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gft469 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Toda T, Nakamura M, Morisawa H, Hirota M.. Proteomic identification of oxidative-stress-reporting biomarkers differentially secreted from human neuroblastoma SH-SY5Y cells. J Electrophoresis 2007, 51, 21–6. doi: 10.2198/jelectroph.51.21 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Chen F, Du G, Shih M, Yuan H, Bao P, Shi S, et al. Safe and effective subcutaneous adipolysis in minipigs by a collagenase derivative. PLoS One 2019, 14, e0227202. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0227202 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Katyal P, Montclare JK.. Design and characterization of fibers and bionanocomposites using the coiled-coil domain of cartilage oligomeric matrix protein. Methods Mol Biol 2018, 1798, 239–63. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-7893-9_19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Goel A, Colcher D, Koo JS, Booth BJ, Pavlinkova G, Batra SK.. Relative position of the hexahistidine tag effects binding properties of a tumor-associated single-chain Fv construct. Biochim Biophys Acta 2000, 1523, 13–20. doi: 10.1016/s0304-4165(00)00086-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Turkewitz DR, Moghaddasi S, Alghalayini A, D’Amario C, Ali HM, Wallach M, et al. Comparative study of His- and non-His-tagged CLIC proteins, reveals changes in their enzymatic activity. Biochem Biophys Rep 2021, 26, 101015. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrep.2021.101015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ayoub N, Roth P, Ucurum Z, Fotiadis D, Hirschi S.. Structural and biochemical insights into His-tag-induced higher-order oligomerization of membrane proteins by cryo-EM and size exclusion chromatography. J Struct Biol 2023, 215, 107924. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2022.107924 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Dai X, Chen Q, Lian M, Zhou Y, Zhou M, Lu S, et al. Systematic high-yield production of human secreted proteins in Escherichia coli. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2005, 332, 593–601. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.04.163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Jiang S, Jin J, Hao S, Yang M, Chen L, Ruan H, et al. Low dose of human scFv-derived BCMA-targeted CAR-T cells achieved fast response and high complete remission in patients with relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma. Blood 2018, 132, 960. doi: 10.1182/blood-2018-99-113220. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Krajewska Wojciechowska J, Krajewski W, Koscielska-Kasprzak K, Zatonski T.. Serum cytokines in ANCA-associated vasculitis: correlation with disease-related clinical and laboratory findings. Medicina Clínica 2021, 157, 464–72. doi: 10.1016/j.medcli.2020.07.036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Nakajima T, Yoshifuji H, Shimizu M, Kitagori K, Murakami K, Nakashima R, et al. A novel susceptibility locus in the IL12B region is associated with the pathophysiology of Takayasu arteritis through IL-12p40 and IL-12p70 production. Arthritis Res Ther 2017, 19, 197. doi: 10.1186/s13075-017-1408-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Newburger JW, Takahashi M, Burns JC, Beiser AS, Chung KJ, Duffy CE, et al. The treatment of Kawasaki syndrome with intravenous gamma globulin. N Engl J Med 1986, 315, 341–7. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198608073150601 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Newburger JW, Takahashi M, Beiser AS, Burns JC, Bastian J, Chung KJ, et al. A single intravenous infusion of gamma globulin as compared with four infusions in the treatment of acute Kawasaki syndrome. N Engl J Med 1991, 324, 1633–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199106063242305 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Hutt M, Farber-Schwarz A, Unverdorben F, Richter F, Kontermann RE.. Plasma half-life extension of small recombinant antibodies by fusion to immunoglobulin-binding domains. J Biol Chem 2012, 287, 4462–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.311522 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Oates-Whitehead RM, Baumer JH, Haines L, Love S, Maconochie IK, Gupta A, et al. Intravenous immunoglobulin for the treatment of Kawasaki disease in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2003, 2003, CD004000. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Ito F, Oharaseki T, Tsukui D, Kimura Y, Yanagida T, Kishi F, et al. Beneficial effects of anti-apolipoprotein A-2 on an animal model for coronary arteritis in Kawasaki disease. Pediatr Rheumatol Online J 2022, 20, 119. doi: 10.1186/s12969-022-00783-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Gong EL, Stoltfus LJ, Brion CM, Murugesh D, Rubin EM.. Contrasting in vivo effects of murine and human apolipoprotein A-II. Role of monomer versus dimer. J Biol Chem 1996, 271, 5984–7. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.11.5984 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Habibi MA, Alesaeidi S, Zahedi M, Hakimi Rahmani S, Piri SM, Tavakolpour S.. The efficacy and safety of rituximab in ANCA-associated vasculitis: a systematic review. Biology (Basel) 2022, 11, 1767. doi: 10.3390/biology11121767 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Vassilopoulos A, Vassilopoulos S, Kalligeros M, Shehadeh F, Mylonakis E.. Incidence of serious infections in patients with ANCA-associated vasculitis receiving immunosuppressive therapy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Med (Lausanne) 2023, 10, 1110548. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2023.1110548 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Matsuyama A, Sakai N, Hiraoka H, Hirano K, Yamashita S.. Cell surface-expressed moesin-like HDL/apoA-I binding protein promotes cholesterol efflux from human macrophages. J Lipid Res 2006, 47, 78–86. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M500425-JLR200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Aratani Y. Myeloperoxidase: its role for host defense, inflammation, and neutrophil function. Arch Biochem Biophys 2018, 640, 47–52. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2018.01.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Ben-Smith A, Dove SK, Martin A, Wakelam MJ, Savage CO.. Antineutrophil cytoplasm autoantibodies from patients with systemic vasculitis activate neutrophils through distinct signaling cascades: comparison with conventional Fcgamma receptor ligation. Blood 2001, 98, 1448–55. doi: 10.1182/blood.v98.5.1448 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Furtmuller PG, Obinger C, Hsuanyu Y, Dunford HB.. Mechanism of reaction of myeloperoxidase with hydrogen peroxide and chloride ion. Eur J Biochem 2000, 267, 5858–64. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.2000.01491.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Kameda T, Usami Y, Shimada S, Haraguchi G, Matsuda K, Sugano M, et al. Determination of myeloperoxidase-induced apoAI-apoAII heterodimers in high-density lipoprotein. Ann Clin Lab Sci 2012, 42, 384–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Kettritz R, Jennette JC, Falk RJ.. Crosslinking of ANCA-antigens stimulates superoxide release by human neutrophils. J Am Soc Nephrol 1997, 8, 386–94. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V83386 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Wong MN, Tharaux PL, Grahammer F, Puelles VG.. Parietal epithelial cell dysfunction in crescentic glomerulonephritis. Cell Tissue Res 2021, 385, 345–54. doi: 10.1007/s00441-021-03513-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data are incorporated into the article and its online supplementary material.