Abstract

The secondary lymphoid organs (SLOs) undergo structural changes with age, which correlates with diminishing immune responses against infectious disease. A growing body of research suggests that the aged tissue microenvironment can contribute to decreased immune function, independent of intrinsic changes to hematopoietic cells with age. Stromal cells impart structural integrity, facilitate fluid transport, and provide chemokine and cytokine signals that are essential for immune homeostasis. Mechanisms that drive SLO development have been described, but their roles in SLO maintenance with advanced age are unknown. Disorganization of the fibroblasts of the T cell and B cell zones may reduce the maintenance of naïve lymphocytes and delay immune activation. Reduced lymphatic transport efficiency with age can also delay the onset of the adaptive immune response. This review focuses on recent studies that describe age-associated changes to the stroma of the lymph nodes and spleen. We also review recent investigations into stromal cell biology, which include high-dimensional analysis of the stromal cell transcriptome and viscoelastic testing of lymph node mechanical properties, as they constitute an important framework for understanding aging of the lymphoid tissues.

Keywords: stroma, fibroblast, endothelium, lymphatics, tissue microenvironment, aging

1. Introduction

The immune system is a collection of cells and tissues that work in concert to protect the entire organism. Timely response to pathogenic agents is critical to avoid catastrophic damage to life-sustaining functions. Thus, immune responses are expedited by the activity of organized lymphoid structures strategically located throughout the body. The secondary lymphoid organs (SLOs) increase the efficiency of immune responses by coordinating distinct subsets of immune cells and physically bringing innate and adaptive immune cells together. In addition to immune cells of hematopoietic origin, lymphoid tissues are also composed of heterogenous stromal cells, which have roles in both organ structural support and immune regulation. Fibroblastic stromal cells have mechanical properties to provide structural integrity, whereas blood and lymphatic vascular endothelial cells facilitate fluid transport. In addition to their contributions to SLO architecture, stromal cells have prominent roles in supporting immune homeostasis and function. Appreciation of the importance of stromal cells to immune regulation has been facilitated by technological advances and engineering approaches, which have enabled in-depth analysis of lymphoid cells and their structural properties.

Biological aging is associated with dramatic changes to the tissue integrity of all organs, with the SLOs being no exception. Age-associated decline of immune function has been correlated to structural changes in aging lymphoid tissues, and investigations into how aging impacts lymphoid architecture and function are ongoing. Here, advanced age in humans is roughly defined as being greater than 55 years-old, which is approximated in laboratory mice and rats that are 18-24 months of age. [1,2] Aging has been strongly associated with increased baseline levels of inflammatory signaling markers[3,4] and the accumulation of senescent cells,[5-7] the contributions of which to immune regulation are an active area of study. In this review, we will focus on the impact of aging on the non-hematopoietic stroma of the SLOs, with emphasis on the lymph nodes and spleen, of which age-related changes have been most explored. Age-associated changes to the primary lymphoid organs, the bone marrow and thymus, have also been described and have been reviewed by us and others.[8-10]

2. Influence of tissue microenvironment on aged immune outcomes

Changes in the homeostasis and function of immune cells with age, particularly T cells and B cells, have been well documented.[11-13] It has been consistently observed that the frequency and numbers of naïve T cells (CD45RA+CD62L+CD95−) decreased sharply with age in human blood, though CD95+ memory T cell numbers remains constant.[14] The decline in naïve T cells is also apparent in laboratory mice, with a gradual decline of CD44loCD62Lhi cells in the blood in adulthood from 3-16 months, and a sharper decrease in frequencies thereafter.[15] For both humans and mice, circulating naïve T cell decline is more dramatic in CD8+ T cells.[14,15] Naïve T cell attrition is significant, as it has been associated with diminished protection against infectious disease.[16] However, it has been difficult to uncouple age-associated T and B cell defects that are due to intrinsic changes in the lymphocytes from those driven by the aging tissue microenvironment. Despite these challenges, there is growing evidence that the age of lymphoid tissues impacts the maintenance and response of T and B cells beyond intrinsic age-related impairments.

Several lines of study indicate that the mechanisms of homeostatic maintenance and activation of naïve T cells decline with age. Experiments in mice suggest that impaired recruitment to and persistence of naïve T cells is exacerbated within the aged tissue microenvironment. Both CD4+ and CD8+ naive T cells, isolated from young mice (2-3 months-old), were adoptively transferred into sub-lethally irradiated mice, and had diminished homeostatic proliferation within aged hosts (16-22 months-old).[17,18] When equivalent numbers of young naïve T cells, either polyclonal[18] or T cell receptor (TCR) transgenic,[19] were adoptively-transferred into young or aged mice, reduced frequencies and numbers of donor-derived cells were recovered from the SLOs of aged hosts. In other experiments, the recovery of young CD44lo naïve and CD44hiCD49dhi virtual-memory T cells two months after transfer into aged mice was significantly diminished as compared to transfer into young hosts.[20] The complementary scenario, in which either young or aged naïve T cells were transferred into young hosts, revealed comparable homeostatic turnover between the naïve T cell ages.[17] Furthermore, aged TCR transgenic CD8+ naïve T cells that were transferred into young hosts were able to expand robustly in response to Listeria monocytogenes (Lm) infection.[21] The aged microenvironment had reduced induction of CD8+ T effector transcriptional and metabolic programs upon acute infection, defects that could be rescued with exogenous addition of interleukins-12 and −18 (IL-12, IL-18) in the aged mice.[21] These experiments suggest that naïve T cells have impaired ability to traffic to and survive within the aged SLOs, and that aged T cells may in fact retain much of their function when presented with an intact microenvironment. The influence of the lymphoid microenvironment is likely pertinent to humans as well, as the capacity for CD45RAhi naïve T cells to maintain their naïve phenotype was dependent on the 3-D structure of human lymphoid tissue FRC organoids.[22]

Experiments using parabiosis, the surgical conjoining of the blood circulation of a pair of mice, have revealed whether immune alterations are transferrable via circulating hematopoietic cells, or are determined by the resident stroma of the host. Studies that conjoined mice of different ages resulted in the seeding of both ages of T cells to the lymph nodes, yet the cellularity of the aged mouse lymph nodes remained significantly reduced compared to that of its young partner, indicating that lymph node capacity was determined by the hosts’ resident cells.[23] Parabiosis experiments have also recently demonstrated that the failure to differentiate B cells during peptide immunization was specific to the aged host, despite circulating young lymphocytes from the conjoined young partner.[24] Thus, aged lymphoid tissues can reduce the maintenance and activation of lymphocytes, even for transferred lymphocytes isolated from young organisms, but the investigation into the mechanisms by which aged tissues limit homeostasis and function are still ongoing.

3. Lymphoid architecture organization and maintenance with age

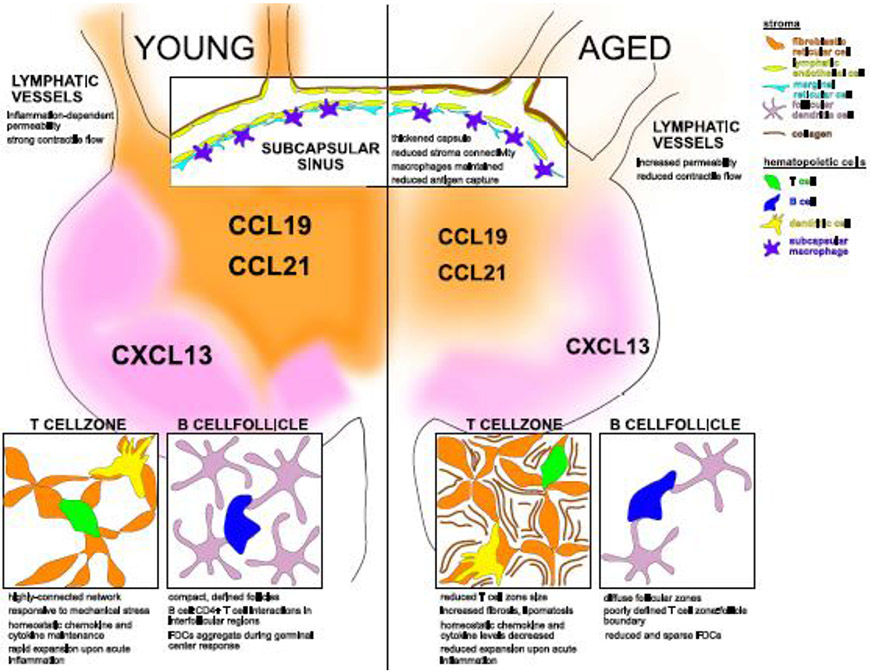

The lymph nodes and splenic white pulp are organized into compartments (Figure 1). Separate regions are dedicated to the support and function of T and B lymphocytes, and passages facilitate the access and transport of lymph and blood. Like a scaffold, stromal cells form a meshlike network within the lymphoid compartments, thus facilitating the migration of adaptive and innate immune cells through the lymphoid tissues.[25] Stromal cells form only about 1% of SLO cellularity,[26] and can be differentiated based on their lack of hematopoietic marker CD45, with subsets broadly distinguished based on expression levels of the surface markers podoplanin (PDPN; gp38) and CD31 (PECAM).[27] These subsets consist of fibroblastic reticular cells (FRCs; PDPN+CD31−), lymphatic endothelial cells (LECs; PDPN+CD31+), blood endothelial cells (BECs, PDPN−CD31+), and double-negative progenitor cells (DNs; PDPN−CD31−). Though the investigation of stroma from the human SLOs is challenging, studies have indicated that they are structurally and transcriptionally similar to those in murine SLOs, which are easier to harvest and study.[27,28] Single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNAseq) of mouse lymph nodes have revealed as many as nine transcriptionally-distinct clusters of FRCs[29-31] and four groups of LECs[32], which enables the functional specialization of the lymphoid compartments. Correlates for the FRC subsets identified within mice were found by scRNAseq analysis of human FRCs, obtained from resected lymph nodes.[30] FRC subsets have also been analyzed by scRNAseq of the murine spleen, which were correlated to human splenic FRCs by microscopy.[33] These transcriptionally distinct stromal subsets form specialized neighborhoods to support immune cell function. At the time of this review, there have not been published datasets of aged stromal cell scRNAseq, though recently Bennett and colleagues have RNA sequenced ex vivo cultured lymph node stromal cells obtained from aged mice.[34] They found that gene expression from aged stromal cells stimulated with either recombinant interferon-alpha (IFNα) or West Nile virus particles was similar to that of young stromal cells, and in fact had upregulated expression of immediate early response genes upon stimuli.[34] scRNAseq of aged stromal cells is certainly to be expected within the next couple years and would further elucidate how aging affects the subset distribution of stromal cell subsets.

Figure 1. Age-associated changes to lymph node architecture.

The lymph node is organized into compartments that express CCL19 and CCL21 (orange) in the T cell zone or CXCL13 (purple) in the B cell follicles. In adulthood (young- left panel), CCL19/21 and CXCL13 expression organizes the T cell and B cell zones. With advanced age (aged- right panel) the lymph node is atrophied, and chemokine expression is reduced and less responsive to immune activation. Contraction of lymphatic vessels deliver solutes and cells via the lymph, but lymphatic vessels with age become more permeable and generate less contractile force. Within the cellular niches of the T cell zone, B cell follicle, and subcapsular sinus (insets) specialized stroma create structures to coordinate hematopoietic cell function. The aged T cell zone is smaller, with increased fibrosis and/or lipomatosis. The aged B cell follicle loses its definition and harbors less follicular dendritic cells (FDCs) during the germinal center response. Lymphatics drain into the subcapsular sinus to allow antigen sampling from the lymph. With age, collagen of the capsule is thickened, gaps between stromal cells widen, though macrophage numbers remain constant. Stroma elements and hematopoietic cells are color-coded in the top right legend.

The SLOs arise during embryonic development through the interactions of hematopoietic lymphoid tissue inducer (LTi) cells and mesenchymal lymphoid tissue organizer (LTo) cells, the latter of which gives rise to heterogenous stromal cells (reviewed in [35-37]). Commitment of LTo cells to the fibroblast and endothelial cell fates is driven by constitutive signals received through the lymphotoxin-beta receptor (LTβR) by lymphotoxin ligands that are expressed by LTi cells and T and B lymphocytes.[38] The interactions between hematopoietic cells and stroma sustains constitutive crosstalk via LTβR,[39] and drives a transcriptional program within stroma to further promote lymphocyte homing to the SLOs.[40] Signaling through LTγR is essential for SLO development, in that Lta−/− and Ltbr−/− mice fail to develop lymph nodes and have diminished spleens,[41] and smaller lymph nodes with defective antiviral immunity was also observed when Ltbr was deleted in a stromal cell-specific manner.[42] Inducible deletion of Ltbr in adult mice also resulted in reduced size and organization of lymph nodes and spleen, indicating a continued requirement of signaling via LTβR for postnatal SLO maintenance.[43] Disorganization can similarly be observed after infections that bear tropism to the SLOs, such as lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus (LCMV); furthermore, the ability for SLOs to recover stromal architecture post-infection is dependent on LTβR signaling, as demonstrated by LCMV-infected spleens treated with a LTβR-blocking fusion protein.[44]

Despite its well-investigated roles in development, the direct impact of LTβR signaling on the size and organization of aged SLOs is unknown. Our studies have indicated that Ltbr is reduced in bulk aged stroma from murine lymph nodes.[18] Along these lines, an overall reduction in lymphocyte cellularity in aged murine lymph nodes and spleen has been observed.[15] Furthermore, aging is associated with disorganization of the T and B cell compartments within the lymph nodes[18,45] and the splenic white pulp.[46] Though immune defects are studied in advanced age, there are indications that SLO changes begin earlier; by inducible labeling of recent thymic emigrants (RTEs) in mice, Sonar and colleagues have demonstrated the preferential loss of RTE retention within the SLOs as early as six months of age in the skin-draining lymph nodes, which coincided with stromal network disorganization and defective immunity against West Nile virus.[47] The molecular mechanisms by which hematopoietic and stromal cells regulate the size and organization of the SLOs in adulthood remain an active area of inquiry.

3.1. FRCs of the T cell zone support T cells

Non-hematopoietic stromal cells are sources of the survival cytokine interleukin-7 (IL-7) and thus play a fundamental role in T cell homeostasis.[48] Levels of IL-7 are tightly regulated, as both innate and adaptive hematopoietic cells express the IL-7 receptor and thus form a control loop modulating IL-7 availability.[49] T cell zone FRCs (TRCs) are major components of the stromal cell networks within the SLOs, being the major sources of IL-7 in the lymph node and the primary mediators of naïve T cell survival.[25,50] The close contacts between T cells and TRCs facilitate homeostatic signaling,[51] as IL-7 is immobilized to cell surfaces by glycosaminoglycans.[52] It should be noted that Il7 is also expressed by LECs,[53] though it is not clear whether they equally support T cell survival.[50] This is perhaps because LECs can lose their gene expression signature during in vitro manipulation.[44] Interestingly, transcript expression of Il7 is maintained with age in mouse lymphoid tissues[17,18] and IL-7 protein expression remains stable in aged mouse and human serum.[17] It has been suggested that despite its continued expression with age, IL-7 is not bioavailable in the aged microenvironment. Experiments in aged mice were able to restore homeostatic proliferation of naïve T cells by the administration of IL-7/M25 antibody complexes.[17,54] Notably, studies using FRC and LEC-specific Il7-knockout mice indicated that naïve T cells may be able to procure IL-7 from other sources in vivo, though central memory T cells remained sensitive to a loss of FRC-derived IL-7.[55] An in vitro study with splenic stromal cells demonstrated that their presence was required for the survival of LTi-like cells isolated from adult mice, but that IL-7 itself was not.[56] Further study is needed to determine whether age-associated changes to IL-7 access within the tissue microenvironment could potentially improve aging immune outcomes.

Stromal expression of the chemokine ligands CCL19 and CCL21 promotes the recruitment of CCR7+ immune cells from the blood and their positioning within the SLOs.[57] Homeostatic expression of CCL19 and CCL21 is maintained by non-canonical NFκB signaling, downstream of LTβR.[39] Though often discussed together, CCL19 and CCL21 have different tissue expression patterns and signaling through CCR7.[58] Surface-immobilized CCL21 induces integrin activation and cell adhesion, which promotes robust and sustained T cell motility.[58] In contrast, binding of CCL19 causes desensitization and internalization of CCR7, which can attenuate T cell migration.[58] The roles of CCL19 and CCL21 are likely not redundant, as Ccl19−/− mice had lymph nodes with distinguished T and B cell zones yet decreased maintenance of T cells; this is in contrast to plt/plt mice, which lack both CCL19 and CCL21 and as a result have disorganized lymph nodes and minimal T cells.[50] Emphasizing their prominent role, diphtheria toxin-induced depletion of FRCs significantly reduced expression of both CCL19 and CCL21, as well as the retention of naïve T cells within the lymph nodes of mice, though this effect was less pronounced in the spleen.[59] Studies have indicated that aged murine lymph nodes have decreased homeostatic expression of either Ccl19[17] or Ccl21[18] transcripts. Inconsistencies in reported results of chemokine expression may be due to differences in stromal cell isolation techniques, which rely on different digestive enzymes such as collagenase or dispase that can cleave certain surface molecules, variability in mechanical stress applied to disrupt the lymphoid issues, or in the choice of lymph node sites that are pooled.[50,60] Nonetheless, both studies determined that reduced Ccl19 or Ccl21 expression by lymph node stromal cells was associated with decreased naïve T cell maintenance within aged mice.[17,18] During acute infection, immune activation further increases CCL19 and CCL21 levels in the SLOs, to promote naïve T cell recruitment. However, upon immunization, protein levels of CCL21 were dramatically decreased in aged as compared to young murine lymph nodes.[19,61] As discussed earlier, SLOs have been reported to decrease in size with age, though the relative changes to the different compartments are likely not equivalent; immunofluorescence imaging revealed smaller T cell zones with decreased overall cellularity within aged murine lymph nodes.[45] In contrast, the murine spleen has been either described as having similar total cellularity yet smaller T cell zones with age,[62] or as having increased T cell zone occupancy, which drove a larger white pulp area with age.[63] Changes to chemokine distribution may be a mechanism for disorganization of T and B cell compartments with age, but more evidence is needed to establish this link.

Not only do FRCs express IL-7, CCL19, and CCL21 to promote immune homeostasis, but they also regulate the magnitude of lymphocyte expansion during immune activation. Mouse studies have revealed that FRCs have receptors for pro-inflammatory ligands including interferon-gamma (IFNγ) and tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNFα), which when sensed will trigger the production of nitric oxide (NO) and dampen T cell proliferation.[64] NO-mediated control of T cell proliferation depended on strong TCR signaling, but FRCs were able to regulate both weakly and strongly stimulated T cells in vitro by expressing prostaglandin E2 (PGE2), the lipid mediator of fever, pain, and swelling during inflammation.[65] PGE2 is generated by cyclooxygenase (COX) enzymes from arachidonic acid, and constitutive activation of COX-2 enables FRCs to generate PGE2 that signal the prostaglandin EP4 receptor on T cells.[65] T cell regulation by murine FRCs has been confirmed with in vitro culture of human T cells with human tonsil tissues, with T cell activation being restored when indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase (IDO), adenosine, PGE2, and transforming growth factor-beta receptor (TGFβR)-signaling pathways were blocked.[66] Lymphocyte expansion was notably reduced upon infection in aged murine lymph nodes,[61] but the roles of NO or PGE2 in suppressing T cell expansion with age have not been explored. Interestingly, upregulation of COX-2 expression has been investigated as a driver of aging[67] and in chronic diseases, including cancer.[68]

As introduced above, high-dimensional analysis of lymph node stroma from adult mice has revealed that fibroblast subsets carry dynamic transcriptional signatures. For example, Ccl19hi TRCs facilitate immune homeostasis, but can adopt an activated, Cxcl9+ TRC signature upon acute inflammation.[29,31] There are also indications that FRCs from different SLOs will be specialized to their anatomical niches, as careful quantification has shown that mesenteric lymph nodes have less FRCs than skin-draining sites.[60] The development of FRCs appears to be site-specific, as the unique trajectories of FRCs in the mesenteries[69] and Peyer’s Patches[70] have been recently explored. Our initial studies have indicated that aging also impacted FRCs in a site-specific manner, as we found that the frequency of PDPNhi FRCs was significantly diminished in aged murine lymph nodes of the mesenteries, though not of the skin-draining sites, whereas DNs and BECs frequencies were increased.[18] We further found that putative FRC progenitors, identified by lower expression levels of the adhesion molecule VCAM-1,[38] had decreased surface expression of LTBR and Ly6A/SCA-1,[18] a fibroblast activation marker.[31] Given the essential role of TRCs in antiviral immunity,[31,42] further work is needed in studying immune activation of TRCs from different tissue sites within aged organisms.

Not only is the crosstalk between FRCs and T cells important, but the interplay among FRCs, T cells, and dendritic cells (DCs) is critical for not only T cell activity, but in the maintenance of the SLOs. Like naïve T cells, activated DCs express CCR7, which enables them to home to the SLOs to traffic upon CCL19- and CCL21-expressing stroma.[25] By migrating along the stromal network within the T cell zone, DCs can present antigens to activate T cells.[51] Evidence supports a model in which stroma are not merely a passive scaffold for DCs searching for T cells, but that they actively signal with DCs to promote stromal activation. In vitro culture of lymph node stroma with activated DCs and TNFα stimulated stromal cell proliferation, an effect that was dependent on expression of the surface marker SIRPα by DCs.[71] SIRPα+ DCs were similarly shown to be important for FRC maintenance in the splenic white pulp.[72] In addition to their responses to stromal CCL19 and CCL21, DC expression of the receptor CLEC-2 has been identified as an axis by which FRCs influence the motility of DCs.[73] Studies have shown that Clec1b-deficient DCs from the skin have reduced migratory capacity to the lymph nodes, and it was further shown, using 3-D cell cultures, that CLEC-2 engagement of PDPN stimulated actin polymerization, thus enabling DCs to extend protrusions and crawl along the FRC network.[73] The engagement of aged DCs with aged stroma has not been addressed, though age-associated changes to the DC compartment have been reported.[74,75] In naïve aged mice, numbers of DC subsets were constant, though their frequencies within the spleen were decreased.[75] When aged mice were challenged with Lm, CD8α+ DCs had impaired expansion and exhibited maturation defects, reflected in poor upregulation of MHC-II, CD86, and CD40.[74] Changes to DCs with age and their ability to engage the stromal cell network may have repercussions on lymph node remodeling during immune activation.

3.2. FRCs of the follicles support B cells

Distinct from TRCs, FRCs in the B cell follicles (BRCs) express CXCL13 and CXCL12,[76,77] serve to support B cell maintenance, antigen sampling, and the generation of germinal centers. Mature B cells expressing CXCR5 are recruited to the follicles in response to the CXCL13 chemokine gradient,[78] and are furthermore maintained by stroma expressing B-cell activating factor (BAFF).[79] Immunofluorescence detection and protein quantification has reported that CXCL13 coverage and abundance in aged mice is reduced in the lymph nodes[45] and spleen,[19,80] though some studies concluded instead that CXCL13 was increased when analyzed by immunofluorescence staining, mRNA transcript expression,[17] and protein quantification.[80] Immunization of aged mice indicated that protein expression of CXCL13 failed to increase in aged murine lymph nodes to the same extent as in young mice, which was correlated to impaired development of humoral responses.[61] B cells compete for BAFF to ensure survival,[11] though aging is associated with an expansion of a B cell phenotype that does not require BAFF signaling for survival.[81] It has not been determined whether stromal expression of BAFF in the SLOs is impacted by aging.

In addition to TRCs and BRCs, some FRCs express intermediate levels of CCL19 or CXCL13, delineating a boundary between T and B cell zones.[29] These interfollicular FRCs serve important roles facilitating interactions between the two compartments.[31] Notably, during immune activation, a subset of activated CD4+ T cells will upregulate CXCR5 in order to migrate to the CXCL13-expressing B cell follicle as they differentiate into T follicular helper (Tfh) cells, and interact with activated B cells to initiate the germinal center response.[82] Live-cell 2-photon microscopy has revealed that CD4+ T cell:B cell interactions occur in the interfollicular regions within 1 to 3 days post-immunization.[83] With age, the boundary between the B cell follicles and T cell zone becomes increasingly irregular in both the murine lymph nodes[45] and the spleen,[63] with the B cell follicles becoming less defined and more diffuse. Experiments in which Ccl19-expressing FRCs were conditionally-depleted resulted in reduced B cells, loss of follicular boundaries, mixing of T and B cell zones, and ultimately reduced germinal center formation.[84] Further studies are needed to determine whether age-associated loss of follicular compartmentalization is related to changes to stromal organization.

It has been well established that germinal centers, organized tissue structures that develop within the follicles during immune activation,[85,86] are reduced in numbers and performance in both mice[87,88] and humans.[89,90] Germinal centers are divided into two histologically distinct regions, the light the dark zones, which contain both lymphocytes and specific BRC subsets. Supporting the notion that B-cell extrinsic influences diminish germinal center responses, young antigen-specific B cells, transferred into young or aged mice and then immunized with their cognate antigen, had reduced positive selection in aged hosts, as read out by c-Myc expression.[91] On the other hand, antigen-specific B cells, isolated from young and aged mice, had comparably robust germinal center expansion within young hosts.[91] Much effort has focused on age-associated defects to lymphocytes, particularly CD4+ Tfh cells, in germinal center initiation and maintenance,[19,87,92] but recent progress has also been made in determining how BRCs impair germinal centers.

The CXCL13+ BRC subset of follicular dendritic cells (FDCs) have been implicated in diminished germinal centers with age. FDCs are distinguished by their expression of surface molecules CD35 and CD21,[93] and are distributed sparsely throughout the follicle at steady state. Upon immunization, they become concentrated into foci within the follicles to serve their predominant role in promoting germinal center responses.[94] Their localization to the light zone of the germinal center and ability to retain antigen complexes enable them to effectively drive the selection of germinal center B cells.[85] Study of aged murine lymph nodes had indicated that FDCs covered a smaller follicular space with age, despite the follicles retaining comparable total area.[45,91] Corresponding to their decreased follicular coverage, aged FDCs had decreased capacity for the uptake of fluorescently-labeled immune complexes.[45] Opposite of FDCs in the light zone, a subset of Cxcl12-expressing BRCs in the dark zone have been identified as supporting germinal center cycling by attracting CXCR4+ germinal center B cells.[77,95] Without cell surface-immobilized CXCL12, transgenic mice have disorganized germinal centers and impaired antibody affinity maturation.[96] Recently, Silva-Cayetano and colleagues have found that CXCR4 expression was increased CD4+ Tfh cells in aged mice.[91] Expression of CXCR4 drove Tfh mislocalization to the dark zone, and restoring light zone-positioning of Tfh promoted FDC expansion and germinal center outputs.[91] It is unclear if CXCL12+ BRCs themselves change with age, as immunofluorescence of aged murine germinal centers showed comparable CXCL12 expression patterns.[91]

Interstitial fluids drain to the lymph nodes and accumulate as lymph in a cavity just beneath the lymph node capsule, known as the subcapsular sinus (SCS). In a similar fashion, blood is filtered through the marginal sinus of the spleen. For the SLOs, transit of fluids through these sinuses is necessary to screen for lymph- or blood-borne antigens. The sinus floors are formed from a layer of LECs or BECs, respectively, and the uptake of antigens is carried out by specialized CD169+ SCS macrophages via cellular protrusions extended through the endothelial barrier.[97] A type of FRC known as the marginal reticular cell (MRC) forms a reticular cell niche lining the lymph node SCS or splenic marginal sinus.[93] MRCs are distinguished among FRCs by expression of the adhesion molecule MAdCAM-1, increased expression of CXCL13, even at steady state, and lack of CCL21 expression.[93] MRCs can respond to LTβ and TNFα signaling in order to give rise to FDCs,[94] which support the germinal center responses as described above. Despite increased frequencies and numbers of SCS macrophages, MRCs are decreased in the aging murine lymph nodes.[45] The clear boundary of MAdCAM-1+ MRCs along the marginal zone of the murine spleen is similarly disrupted with age.[46] Denton and colleagues recently established the contribution of stroma to impaired humoral responses, demonstrating that aged mice had significantly diminished MRC and FDC compartments, which failed to proliferate upon immunization.[24] Administration of Toll-like receptor-4 (TLR4)-stimulating adjuvant was able to restore MRC and germinal center B cell expansion in immunized aged mice; however, antibody responses were not restored,[24] suggesting other factors yet contribute to diminished antibody generation with age.

3.3. Tissue integrity

The lymph nodes must be able to swell up to ten-times their original size within one week after immunization to accommodate the rapid proliferation of lymphocyte effectors.[98,99] SLO architecture is comprised of a strong yet deformable conduit network of FRCs surrounding extracellular matrix (ECM) fiber bundles, creating a reticular network that is highly connected.[100] As the conduits are formed by the bodies of FRCs wrapped around collagen fibers, the FRCs are thus positioned to make direct contact with lymphocytes and can therefore rapidly respond upon lymphocyte activation.[101] In vitro studies demonstrated that FRCs can be induced to lay down ECM to generate the reticular network when stimulated by TNFα and LTβ ligands provided by immune cells.[102] Inflammation-induced expansion of the FRCs network leads to local fissures in the conduits, but the intricate channels provide enough redundancy to maintain connectivity of the network.[103] The FRC network has been modeled using graph theory as a small-world network,[101] which similarly captures the idea that FRCs, modeled as network nodes, are highly interconnected and can thus maintain structural integrity even when perturbed. In this context, where lymph node architecture is treated as a reticular network, it was demonstrated that FRCs in the T cell zone of aged murine lymph nodes responded to immunization by maintaining the same degree of branching and network length as those in young lymph nodes.[104] Rather, the study concluded that it was the organization of the aged B cell follicle stromal network and the interfollicular zones that was disrupted upon immunization, unlike what was observed in the T cell zone.[104] This suggests that the capacity for the FRC network to interact with T cells during lymph node expansion is not diminished with age; what is left is whether the quality of the FRC:T cell interaction is also maintained with age.

Network expansion is thus cued by lymphocyte activation, which provides cytokine signals as well as mechanical stress cues.[98] In peptide-immunized mice, the first wave of proliferation is by LECs, followed closely by FRC expansion.[105] Though stroma in the developing spleen emerge from perivascular precursors,[106] mosaic-labelling of sparse TRCs reveal clusters of progeny cells proliferating in place in response to local activating signals.[107] In aged mice, quantification of lymph node stromal subsets indicated that magnitude of expansion for FRCs and LECs was diminished and delayed.[104] Recently, the lymph node has been analyzed as a viscoelastic system, in which the stress-strain responses of the FRC network was determined. The network was held under tension, even as the density of T cells packed within the spaces between network fibers increased.[107,108] The mechanical forces generated by the increased tension were relieved by engagement of PDPN on FRCs by CLEC-2-expressing DCs, which downregulated the activities of actin-tethering proteins and enabled FRC elongation.[108] In addition to network stretching, increased structural stiffness was sensed via PDPN to induce FRC proliferation.[107,108] As FRCs receive mechanical feedback to proliferate until the network is large enough to accommodate the lymphocytes therein, yet it appears that aged lymph nodes do not expand to the same size as young lymph nodes,[104] it would be interesting to determine whether this mechanical stress feedback loop is perturbed in aging.

The lymph nodes of aged mice have capsule thickening and accumulation of fibrosis within the parenchyma,[15,18] suggesting that the integrity of the stromal network could be changing with age. Our live-cell 2-photon microscopy analysis of murine slice explants revealed that the motility of young, adoptively-transferred naïve T cells was diminished in aged lymph nodes when in proximity to collagen deposition.[18] Lymph node fibrosis can result from chronic disease, such as human or simian immunodeficiency virus infection,[109-111] lymphedema caused by impaired lymphatic flow,[112] or during transplant rejection,[113,114] but it is unclear if the etiology of fibrosis seen in aging lymph nodes is analogous to these pathologies. When exploring the role of Hippo signaling in FRC maturation, Choi and colleagues demonstrated that genetic hyperactivation of Hippo pathway mediators YAP and TAZ drove a fibrotic lymph node architecture.[115] The authors demonstrated that YAP and TAZ were hyperactivated in a FRC-specific, Ltbr-deficient mouse, resulting in a fibrotic lymph node and thus demonstrating a link between Hippo and LTβR signaling.[115] While there are reports that human lymph nodes can become fibrotic with age,[89,116] or among populations in developing countries with endemic diseases,[117] lipid accumulation also appears to be a predominant phenotype observed.[118] A recent study by Bekkhus and colleagues found that, with age, stromal cells of the lymph node medulla co-stained for both fibroblast and adipocyte markers; an associated reduction in the expression of LTβ, necessary for commitment to the fibroblast lineage,[38] suggested a model in which loss of LTβR signaling could drive the differentiation of mesenchymal precursors away from the fibroblast and towards the adipocyte fate.[118] Unlike the fibrotic lymph node observed with hyperactivated YAP and TAZ, Choi and colleagues had also found that an adipogenic lymph node fate was promoted by genetic cessation of YAP and TAZ expression.[115] Thus, changes to lymph node stroma may also play a role in SLO aging, where aberrant YAP and TAZ activity, either hyperactivation or abrogation, potentially increases fibrotic deposition in the SLOs or transforms FRC precursors to adipocytes, respectively.

3.4. Lymphatic transport

The SLOs are hubs in a circuit composed of lymphatic and blood vasculature, which essentially forms a body-wide fluid transport network. The lymphatic vasculature is a unidirectional fluid transport system that carries interstitial fluid—containing cellular products, solutes, and antigenic material—from the organs and body barrier tissues to eventually empty into the blood circulation (reviewed in [119]). The lymphatics serve a critical link between the innate and adaptive immune responses, as antigens taken up at the barrier surfaces by activated CCR7+ DCs will be guided by CCL21 expression on LECs of the lymphatic capillaries,[120] where they will drain to the nearest lymph node and begin screening for antigen-specific T cells. Thus, effective lymphatic transport is integral to the generation of adaptive immune responses, as had been demonstrated in transgenic mice lacking lymphatic capillaries.[121]

The permeability and contractility of lymphatic vessels govern the efficiency of lymphatic transport. Fluid transport must be driven by the lymphatic vessels themselves, as there is no pump like the heart in blood circulation. These properties are regulated by both biochemical and mechanical stress cues. Vessels are surrounded by a glycocalyx, a structure composed of carbohydrates and proteins that also plays a significant role in regulating vascular permeability, and smooth muscle that contracts and drives fluid in one direction through one-way valves. In addition to its immune regulatory role, NO promotes vascular permeability and impacts contractile pumping.[122] Studies in aged rats indicated that NO was dysregulated, impairing lymphatic flow.[123] Thus with age, the lymphatics are more permeable and less contractile,[124] which has significant implications on the efficacy of immune responses. Analysis of lymphatic vessels from aged rats using electron microscopy revealed declining structure with reduced ECM, which corresponded to defects in the glycocalyx and reduced integrity of tight junctions.[125] In addition to signs of increased permeability, structural analysis of aged rat lymphatic vessels revealed a reduction in the expression of proteins associated with smooth muscle contraction, as well as inefficient in vivo pumping.[125] Given their structural and signaling roles in the lymphatic vascular apparatus, further analyses into the properties of aging LECs of the SLOs and the lymphatic vasculature are needed in order to determine their impacts on immune cell trafficking and activation.

4. Conclusions

The last decade has seen increased research activity in the field of lymphoid stromal cell immunology, capitalizing on new analytical technologies. Furthermore, the study of immunobiology has become infused with engineering concepts, as we now understand that both biochemical and mechanical forces are inputs for immune control loops. In this review we provided a basic understanding of how the immune functions of the SLOs are dictated by their structure and form. This knowledge is important, as the organization and structural properties of the SLOs may be altered by the biological processes of aging, thus impairing their efficient performance. We have focused on the known subsets of SLO fibroblastic and endothelial stromal cells, but our review is incomplete, as analyses of these subsets with age is yet ongoing. As technology will enable more sophisticated ways to describe the SLOs as interconnected systems, we expect that therapies will also be developed that address tissue-specific changes elicited by aging. Immune function is context-dependent, and so targeting SLO stromal cells to restore the immune microenvironment is a potential strategy for improving immune outcomes for older individuals.

Highlights.

Reduced immune outputs with age coincide with secondary lymphoid organ degradation.

Crosstalk of lymphocytes and stroma is necessary for lymphoid tissue maintenance.

Aged stromal cells have impaired expansion during immune activation and reduced chemokine expression.

Acknowledgements

We thank Fotini Gounari for reading and comments of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Mayo Clinic Robert and Arlene Kogod Center on Aging Innovation Award [UL1R002377] and National Institutes of Health grant R01 AG080037.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- [1].Flurkey K, Currer JM, Harrison DE, Mouse Models in Aging Research, in: The Mouse in Biomedical Research: Normative Biology, Husbandry, and Models, 2nd ed., Academic Press, Burlington, MA, 2007: pp. 637–672. [Google Scholar]

- [2].Miller RA, Nadon NL, Principles of Animal Use for Gerontological Research, Journal of Gerontology. 55A (2000) B117–123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Bauernfeind F, Niepmann S, Knolle PA, Hornung V, Aging-Associated TNF Production Primes Inflammasome Activation and NLRP3-Related Metabolic Disturbances, J.I 197 (2016) 2900–2908. 10.4049/jimmunol.1501336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Franceschi C, Garagnani P, Parini P, Giuliani C, Santoro A, Inflammaging: a new immune–metabolic viewpoint for age-related diseases, Nat Rev Endocrinol. 14 (2018) 576–590. 10.1038/s41574-018-0059-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Budamagunta V, Foster TC, Zhou D, Cellular senescence in lymphoid organs and immunosenescence, Aging. 13 (2021) 19920–19941. 10.18632/aging.203405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Gorgoulis V, Adams PD, Alimonti A, Bennett DC, Bischof O, Bishop C, Campisi J, Collado M, Evangelou K, Ferbeyre G, Gil J, Hara E, Krizhanovsky V, Jurk D, Maier AB, Narita M, Niedernhofer L, Passos JF, Robbins PD, Schmitt CA, Sedivy J, Vougas K, von Zglinicki T, Zhou D, Serrano M, Demaria M, Cellular Senescence: Defining a Path Forward, Cell. 179 (2019) 813–827. 10.1016/j.cell.2019.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Kennedy BK, Berger SL, Brunet A, Campisi J, Cuervo AM, Epel ES, Franceschi C, Lithgow GJ, Morimoto RI, Pessin JE, Rando TA, Richardson A, Schadt EE, Wyss-Coray T, Sierra F, Geroscience: Linking Aging to Chronic Disease, Cell. 159 (2014) 709–713. 10.1016/j.cell.2014.10.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Srinivasan J, Lancaster JN, Singarapu N, Hale LP, Ehrlich LIR, Richie E, Age-Related Changes in Thymic Central Tolerance, Frontiers in Immunology. 12 (2021) 24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Chinn IK, Blackburn CC, Manley NR, Sempowski GD, Changes in primary lymphoid organs with aging, Seminars in Immunology. 24 (2012) 309–320. 10.1016/j.smim.2012.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Lepletier A, Alsharif A, Chidgey AP, Inflammation and Thymus Ageing, Endocrine Immunology. 48 (2017) 19–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Kogut I, Scholz JL, Cancro MP, Cambier JC, B cell maintenance and function in aging, Seminars in Immunology. 24 (2012) 342–349. 10.1016/j.smim.2012.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Goronzy JJ, Weyand CM, Mechanisms underlying T cell ageing, Nat Rev Immunol. 19 (2019) 573–583. 10.1038/s41577-019-0180-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Nikolich-Žugich J, The twilight of immunity: emerging concepts in aging of the immune system, Nat Immunol. 19 (2018) 10–19. 10.1038/s41590-017-0006-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Fagnoni FF, Vescovini R, Passeri G, Bologna G, Pedrazzoni M, Lavagetto G, Casti A, Franceschi C, Passeri M, Sansoni P, Shortage of circulating naive CD8+ T cells provides new insights on immunodeficiency in aging, Blood. 95 (2000) 2860–2868. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Thompson HL, Smithey MJ, Uhrlaub JL, Jeftić I, Jergović M, White SE, Currier N, Lang AM, Okoye A, Park B, Picker LJ, Surh CD, Nikolich-Žugich J, Lymph nodes as barriers to T-cell rejuvenation in aging mice and nonhuman primates, Aging Cell. 18 (2019) e12865. 10.1111/acel.12865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Appay V, Sauce D, Naive T cells: The crux of cellular immune aging?, Experimental Gerontology. 54 (2014) 90–93. 10.1016/j.exger.2014.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Becklund BR, Purton JF, Ramsey C, Favre S, Vogt TK, Martin CE, Spasova DS, Sarkisyan G, LeRoy E, Tan JT, Wahlus H, Bondi-Boyd B, Luther SA, Surh CD, The aged lymphoid tissue environment fails to support naïve T cell homeostasis, Sci Rep. 6 (2016) 30842. 10.1038/srep30842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Kwok T, Medovich SC, Silva-Junior IA, Brown EM, Haug JC, Barrios MR, Morris KA, Lancaster JN, Age-Associated Changes to Lymph Node Fibroblastic Reticular Cells, Front. Aging 3 (2022) 838943. 10.3389/fragi.2022.838943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Lefebvre JS, Maue AC, Eaton SM, Lanthier PA, Tighe M, Haynes L, The aged microenvironment contributes to the age-related functional defects of CD4 T cells in mice: The aged environment impairs CD4 T-cell functions, Aging Cell. 11 (2012) 732–740. 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2012.00836.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Quinn KM, Fox A, Harland KL, Russ BE, Li J, Nguyen THO, Loh L, Olshanksy M, Naeem H, Tsyganov K, Wiede F, Webster R, Blyth C, Sng XYX, Tiganis T, Powell D, Doherty PC, Turner SJ, Kedzierska K, La Gruta NL, Age-Related Decline in Primary CD8+ T Cell Responses Is Associated with the Development of Senescence in Virtual Memory CD8+ T Cells, Cell Reports. 23 (2018) 3512–3524. 10.1016/j.celrep.2018.05.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Jergović M, Thompson HL, Renkema KR, Smithey MJ, Nikolich-Žugich J, Defective Transcriptional Programming of Effector CD8 T Cells in Aged Mice Is Cell-Extrinsic and Can Be Corrected by Administration of IL-12 and IL-18, Front. Immunol 10 (2019) 2206. 10.3389/fimmu.2019.02206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Lambert S, Cao W, Zhang H, Colville A, Liu J-Y, Weyand CM, Goronzy JJ, Gustafson CE, The influence of three-dimensional structure on naïve T cell homeostasis and aging, Front. Aging 3 (2022) 1045648. 10.3389/fragi.2022.1045648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Davies JS, Thompson HL, Pulko V, Padilla Torres J, Nikolich-Žugich J, Role of Cell-Intrinsic and Environmental Age-Related Changes in Altered Maintenance of Murine T Cells in Lymphoid Organs, The Journals of Gerontology: Series A. 73 (2018) 1018–1026. 10.1093/gerona/glx102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Denton AE, Dooley J, Cinti I, Silva-Cayetano A, Fra-Bido S, Innocentin S, Hill DL, Carr EJ, McKenzie ANJ, Liston A, Linterman MA, Targeting TLR4 during vaccination boosts MAdCAM-1 + lymphoid stromal cell activation and promotes the aged germinal center response, Sci. Immunol 7 (2022) eabk0018. 10.1126/sciimmunol.abk0018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Bajénoff M, Egen JG, Koo LY, Laugier JP, Brau F, Glaichenhaus N, Germain RN, Stromal Cell Networks Regulate Lymphocyte Entry, Migration, and Territoriality in Lymph Nodes, Immunity. 25 (2006) 989–1001. 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.10.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Malhotra D, Fletcher AL, Astarita J, Lukacs-Kornek V, Tayalia P, Gonzalez SF, Elpek KG, Chang SK, Knoblich K, Hemler ME, Brenner MB, Carroll MC, Mooney DJ, Turley SJ, Transcriptional profiling of stroma from inflamed and resting lymph nodes defines immunological hallmarks, Nat Immunol. 13 (2012) 499–510. 10.1038/ni.2262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Grasso C, Pierie C, Mebius RE, van Baarsen LGM, Lymph node stromal cells: subsets and functions in health and disease, Trends in Immunology. 42 (2021) 920–936. 10.1016/j.it.2021.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Mueller SN, Germain RN, Stromal cell contributions to the homeostasis and functionality of the immune system, Nat Rev Immunol. 9 (2009) 618–629. 10.1038/nri2588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Rodda LB, Lu E, Bennett ML, Sokol CL, Wang X, Luther SA, Barres BA, Luster AD, Ye CJ, Cyster JG, Single-Cell RNA Sequencing of Lymph Node Stromal Cells Reveals Niche-Associated Heterogeneity, Immunity. 48 (2018) 1014–1028.e6. 10.1016/j.immuni.2018.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Kapoor VN, Müller S, Keerthivasan S, Brown M, Chalouni C, Storm EE, Castiglioni A, Lane R, Nitschke M, Dominguez CX, Astarita JL, Krishnamurty AT, Carbone CB, Senbabaoglu Y, Wang AW, Wu X, Cremasco V, Roose-Girma M, Tam L, Doerr J, Chen MZ, Lee WP, Modrusan Z, Yang YA, Bourgon R, Sandoval W, Shaw AS, De Sauvage FJ, Mellman I, Moussion C, Turley SJ, Gremlin 1+ fibroblastic niche maintains dendritic cell homeostasis in lymphoid tissues, Nat Immunol. 22 (2021) 571–585. 10.1038/s41590-021-00920-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Perez-Shibayama C, Islander U, Lütge M, Cheng H-W, Onder L, Ring SS, De Martin A, Novkovic M, Colston J, Gil-Cruz C, Ludewig B, Type I interferon signaling in fibroblastic reticular cells prevents exhaustive activation of antiviral CD8 + T cells, Sci. Immunol 5 (2020) eabb7066. 10.1126/sciimmunol.abb7066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Fujimoto N, He Y, D’Addio M, Tacconi C, Detmar M, Dieterich LC, Single-cell mapping reveals new markers and functions of lymphatic endothelial cells in lymph nodes, PLoS Biol. 18 (2020) e3000704. 10.1371/journal.pbio.3000704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Alexandre YO, Schienstock D, Lee HJ, Gandolfo LC, Williams CG, Devi S, Pal B, Groom JR, Cao W, Christo SN, Gordon CL, Starkey G, D’Costa R, Mackay LK, Haque A, Ludewig B, Belz GT, Mueller SN, A diverse fibroblastic stromal cell landscape in the spleen directs tissue homeostasis and immunity, Sci. Immunol 7 (2022) eabj0641. 10.1126/sciimmunol.abj0641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Bennett AK, Richner M, Mun MD, Richner JM, Type I IFN stimulates lymph node stromal cells from adult and old mice during a West Nile virus infection, Aging Cell. 22 (2023) e13796. 10.1111/acel.13796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Pikor NB, Cheng H-W, Onder L, Ludewig B, Development and Immunological Function of Lymph Node Stromal Cells, J.I 206 (2021) 257–263. 10.4049/jimmunol.2000914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Brendolan A, Caamaño JH, Mesenchymal cell differentiation during lymph node organogenesis, Front. Immun 3 (2012). 10.3389/fimmu.2012.00381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Onder L, Ludewig B, A Fresh View on Lymph Node Organogenesis, Trends in Immunology. 39 (2018) 775–787. 10.1016/j.it.2018.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Bénézech C, White A, Mader E, Serre K, Parnell S, Pfeffer K, Ware CF, Anderson G, Caamaño JH, Ontogeny of Stromal Organizer Cells during Lymph Node Development, J.I 184 (2010) 4521–4530. 10.4049/jimmunol.0903113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Mukherjee T, Chatterjee B, Dhar A, Bais SS, Chawla M, Roy P, George A, Bal V, Rath S, Basak S, A TNF-p100 pathway subverts noncanonical NF-κB signaling in inflamed secondary lymphoid organs, EMBO J. 36 (2017) 3501–3516. 10.15252/embj.201796919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Browning JL, Inhibition of the lymphotoxin pathway as a therapy for autoimmune disease, Immunological Reviews. 223 (2008) 202–220. 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2008.00633.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Tumanov AV, Grivennikov SI, Shakhov AN, Rybtsov SA, Koroleva EP, Takeda J, Nedospasov SA, Kuprash DV, Dissecting the role of lymphotoxin in lymphoid organs by conditional targeting, Immunological Reviews. 195 (2003) 106–116. 10.1034/j.1600-065X.2003.00071.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Chai Q, Onder L, Scandella E, Gil-Cruz C, Perez-Shibayama C, Cupovic J, Danuser R, Sparwasser T, Luther SA, Thiel V, Rülicke T, Stein JV, Hehlgans T, Ludewig B, Maturation of Lymph Node Fibroblastic Reticular Cells from Myofibroblastic Precursors Is Critical for Antiviral Immunity, Immunity. 38 (2013) 1013–1024. 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.03.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Shou Y, Koroleva E, Spencer CM, Shein SA, Korchagina AA, Yusoof KA, Parthasarathy R, Leadbetter EA, Akopian AN, Muñoz AR, Tumanov AV, Redefining the Role of Lymphotoxin Beta Receptor in the Maintenance of Lymphoid Organs and Immune Cell Homeostasis in Adulthood, Front. Immunol 12 (2021) 712632. 10.3389/fimmu.2021.712632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Scandella E, Bolinger B, Lattmann E, Miller S, Favre S, Littman DR, Finke D, Luther SA, Junt T, Ludewig B, Restoration of lymphoid organ integrity through the interaction of lymphoid tissue–inducer cells with stroma of the T cell zone, Nat Immunol. 9 (2008) 667–675. 10.1038/ni.1605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Turner VM, Mabbott NA, Structural and functional changes to lymph nodes in ageing mice, Immunology. 151 (2017) 239–247. 10.1111/imm.12727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Turner VM, Mabbott NA, Influence of ageing on the microarchitecture of the spleen and lymph nodes, Biogerontology. 18 (2017) 723–738. 10.1007/s10522-017-9707-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Sonar SA, Uhrlaub JL, Coplen CP, Sempowski GD, Dudakov JA, van den Brink MRM, LaFleur BJ, Jergović M, Nikolich-Žugich J, Early age–related atrophy of cutaneous lymph nodes precipitates an early functional decline in skin immunity in mice with aging, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 119 (2022) e2121028119. 10.1073/pnas.2121028119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Huang H-Y, Luther SA, Expression and function of interleukin-7 in secondary and tertiary lymphoid organs, Seminars in Immunology. 24 (2012) 175–189. 10.1016/j.smim.2012.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Martin CE, Spasova DS, Frimpong-Boateng K, Kim H-O, Lee M, Kim KS, Surh CD, Interleukin-7 Availability Is Maintained by a Hematopoietic Cytokine Sink Comprising Innate Lymphoid Cells and T Cells, Immunity. 47 (2017) 171–182.e4. 10.1016/j.immuni.2017.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Link A, Vogt TK, Favre S, Britschgi MR, Acha-Orbea H, Hinz B, Cyster JG, Luther SA, Fibroblastic reticular cells in lymph nodes regulate the homeostasis of naive T cells, Nat Immunol. 8 (2007) 1255–1265. 10.1038/ni1513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Tasnim H, Fricke GM, Byrum JR, Sotiris JO, Cannon JL, Moses ME, Quantitative Measurement of Naïve T Cell Association With Dendritic Cells, FRCs, and Blood Vessels in Lymph Nodes, Front. Immunol 9 (2018) 1571. 10.3389/fimmu.2018.01571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Kimura K, Matsubara H, Sogoh S, Kita Y, Sakata T, Watanabe S, Hamaoka T, Fujiwara H, Role of glycosaminoglycans in the regulation of T cell proliferation induced by thymic stroma-derived T cell growth factor., (1991) 8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Onder L, Narang P, Scandella E, Chai Q, Iolyeva M, Hoorweg K, Halin C, Richie E, Kaye P, Westermann J, Cupedo T, Coles M, Ludewig B, IL-7–producing stromal cells are critical for lymph node remodeling, Blood. 120 (2012) 4675–4683. 10.1182/blood-2012-03-416859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Uhrlaub JL, Jergović M, Bradshaw CM, Sonar S, Coplen CP, Dudakov J, Murray KO, Lanteri MC, Busch MP, van den Brink MRM, Nikolich-Žugich J, Quantitative restoration of immune defense in old animals determined by naive antigen-specific CD8 T-cell numbers, Aging Cell. 21 (2022). 10.1111/acel.13582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Knop L, Deiser K, Bank U, Witte A, Mohr J, Philipsen L, Fehling HJ, Müller AJ, Kalinke U, Schüler T, IL-7 derived from lymph node fibroblastic reticular cells is dispensable for naive T cell homeostasis but crucial for central memory T cell survival, Eur. J. Immunol 50 (2020) 846–857. 10.1002/eji.201948368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Hou TZ, Mustafa MZ, Flavell SJ, Barrington F, Jenkinson EJ, Anderson G, Lane PJL, Withers DR, Buckley CD, Splenic stromal cells mediate IL-7 independent adult lymphoid tissue inducer cell survival, Eur. J. Immunol 40 (2010) 359–365. 10.1002/eji.200939776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Krishnamurty AT, Turley SJ, Lymph node stromal cells: cartographers of the immune system, Nat Immunol. 21 (2020) 369–380. 10.1038/s41590-020-0635-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Hauser MA, Legler DF, Common and biased signaling pathways of the chemokine receptor CCR7 elicited by its ligands CCL19 and CCL21 in leukocytes, Journal of Leukocyte Biology. 99 (2016) 869–882. 10.1189/jlb.2MR0815-380R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Denton AE, Roberts EW, Linterman MA, Fearon DT, Fibroblastic reticular cells of the lymph node are required for retention of resting but not activated CD8+ T cells, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 111 (2014) 12139–12144. 10.1073/pnas.1412910111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Fletcher AL, Malhotra D, Acton SE, Lukacs-Kornek V, Bellemare-Pelletier A, Curry M, Armant M, Turley SJ, Reproducible Isolation of Lymph Node Stromal Cells Reveals Site-Dependent Differences in Fibroblastic Reticular Cells, Front. Immun 2 (2011). 10.3389/fimmu.2011.00035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Richner JM, Gmyrek GB, Govero J, Tu Y, van der Windt GJW, Metcalf TU, Haddad EK, Textor J, Miller MJ, Diamond MS, Age-Dependent Cell Trafficking Defects in Draining Lymph Nodes Impair Adaptive Immunity and Control of West Nile Virus Infection, PLoS Pathog. 11 (2015) e1005027. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Masters AR, Jellison ER, Puddington L, Khanna KM, Haynes L, Attrition of T Cell Zone Fibroblastic Reticular Cell Number and Function in Aged Spleens, IH. 2 (2018) 155–163. 10.4049/immunohorizons.1700062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Aw D, Hilliard L, Nishikawa Y, Cadman ET, Lawrence RA, Palmer DB, Disorganization of the splenic microanatomy in ageing mice, Immunology. 148 (2016) 92–101. 10.1111/imm.12590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Lukacs-Kornek V, Malhotra D, Fletcher AL, Acton SE, Elpek KG, Tayalia P, Collier A, Turley SJ, Regulated release of nitric oxide by nonhematopoietic stroma controls expansion of the activated T cell pool in lymph nodes, Nat Immunol. 12 (2011) 1096–1104. 10.1038/ni.2112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Schaeuble K, Cannelle H, Favre S, Huang H-Y, Oberle SG, Speiser DE, Zehn D, Luther SA, Attenuation of chronic antiviral T-cell responses through constitutive COX2-dependent prostanoid synthesis by lymph node fibroblasts, PLoS Biol. 17 (2019) e3000072. 10.1371/journal.pbio.3000072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Knoblich K, Cruz Migoni S, Siew SM, Jinks E, Kaul B, Jeffery HC, Baker AT, Suliman M, Vrzalikova K, Mehenna H, Murray PG, Barone F, Oo YH, Newsome PN, Hirschfield G, Kelly D, Lee SP, Parekkadan B, Turley SJ, Fletcher AL, The human lymph node microenvironment unilaterally regulates T-cell activation and differentiation, PLoS Biol. 16 (2018) e2005046. 10.1371/journal.pbio.2005046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Kim J, Vaish V, Feng M, Field K, Chatzistamou I, Shim M, Transgenic expression of cyclooxygenase-2 (COX2) causes premature aging phenotypes in mice, Aging. 8 (2016) 2392–2406. 10.18632/aging.101060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Gonçalves S, Yin K, Ito Y, Chan A, Olan I, Gough S, Cassidy L, Serrao E, Smith S, Young A, Narita M, Hoare M, COX2 regulates senescence secretome composition and senescence surveillance through PGE2, Cell Reports. 34 (2021) 108860. 10.1016/j.celrep.2021.108860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Li C, Lam E, Perez-Shibayama C, Ward LA, Zhang J, Lee D, Nguyen A, Ahmed M, Brownlie E, Korneev KV, Rojas O, Sun T, Navarre W, He HH, Liao S, Martin A, Ludewig B, Gommerman JL, Early-life programming of mesenteric lymph node stromal cell identity by the lymphotoxin pathway regulates adult mucosal immunity, Sci. Immunol 4 (2019) eaax1027. 10.1126/sciimmunol.aax1027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70].Prados A, Onder L, Cheng H-W, Mörbe U, Lütge M, Gil-Cruz C, Perez-Shibayama C, Koliaraki V, Ludewig B, Kollias G, Fibroblastic reticular cell lineage convergence in Peyer’s patches governs intestinal immunity, Nat Immunol. (2021). 10.1038/s41590-021-00894-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71].Komori S, Saito Y, Respatika D, Nishimura T, Kotani T, Murata Y, Matozaki T, SIRPα+ dendritic cells promote the development of fibroblastic reticular cells in murine peripheral lymph nodes, Eur. J. Immunol 49 (2019) 1364–1371. 10.1002/eji.201948103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [72].Saito Y, Respatika D, Komori S, Washio K, Nishimura T, Kotani T, Murata Y, Okazawa H, Ohnishi H, Kaneko Y, Yui K, Yasutomo K, Nishigori C, Nojima Y, Matozaki T, SIRPα+ dendritic cells regulate homeostasis of fibroblastic reticular cells via TNF receptor ligands in the adult spleen, Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 114 (2017) E10151–E10160. 10.1073/pnas.1711345114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [73].Acton SE, Astarita JL, Malhotra D, Lukacs-Kornek V, Franz B, Hess PR, Jakus Z, Kuligowski M, Fletcher AL, Elpek KG, Bellemare-Pelletier A, Sceats L, Reynoso ED, Gonzalez SF, Graham DB, Chang J, Peters A, Woodruff M, Kim Y-A, Swat W, Morita T, Kuchroo V, Carroll MC, Kahn ML, Wucherpfennig KW, Turley SJ, Podoplanin-Rich Stromal Networks Induce Dendritic Cell Motility via Activation of the C-type Lectin Receptor CLEC-2, Immunity. 37 (2012) 276–289. 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.05.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [74].Li G, Smithey MJ, Rudd BD, Nikolich-Žugich J, Age-associated alterations in CD8α+ dendritic cells impair CD8 T-cell expansion in response to an intracellular bacterium, Aging Cell. 11 (2012) 968–977. 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2012.00867.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [75].van Dommelen SL, Rizzitelli A, Chidgey A, Boyd R, Shortman K, Wu L, Regeneration of dendritic cells in aged mice, Cell Mol Immunol. 7 (2010) 108–115. 10.1038/cmi.2009.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [76].Cosgrove J, Novkovic M, Albrecht S, Pikor NB, Zhou Z, Onder L, Mörbe U, Cupovic J, Miller H, Alden K, Thuery A, O’Toole P, Pinter R, Jarrett S, Taylor E, Venetz D, Heller M, Uguccioni M, Legler DF, Lacey CJ, Coatesworth A, Polak WG, Cupedo T, Manoury B, Thelen M, Stein JV, Wolf M, Leake MC, Timmis J, Ludewig B, Coles MC, B cell zone reticular cell microenvironments shape CXCL13 gradient formation, Nat Commun. 11 (2020) 3677. 10.1038/s41467-020-17135-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [77].Pikor NB, Mörbe U, Lütge M, Gil-Cruz C, Perez-Shibayama C, Novkovic M, Cheng H-W, Nombela-Arrieta C, Nagasawa T, Linterman MA, Onder L, Ludewig B, Remodeling of light and dark zone follicular dendritic cells governs germinal center responses, Nat Immunol. 21 (2020) 649–659. 10.1038/s41590-020-0672-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [78].Ansel KM, Ngo VN, Hyman PL, Luther SA, Förster R, Sedgwick JD, Browning JL, Lipp M, Cyster JG, A chemokine-driven positive feedback loop organizes lymphoid follicles, Nature. 406 (2000) 309–314. 10.1038/35018581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [79].Gorelik L, Gilbride K, Dobles M, Kalled SL, Zandman D, Scott ML, Normal B Cell Homeostasis Requires B Cell Activation Factor Production by Radiation-resistant Cells, Journal of Experimental Medicine. 198 (2003) 937–945. 10.1084/jem.20030789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [80].Minges Wols HA, Johnson KM, Ippolito JA, Birjandi SZ, Su Y, Le PT, Witte PL, Migration of immature and mature B cells in the aged microenvironment, Immunology. 129 (2010) 278–290. 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2009.03182.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [81].Hao Y, O’Neill P, Naradikian MS, Scholz JL, Cancro MP, A B-cell subset uniquely responsive to innate stimuli accumulates in aged mice, Blood. 118 (2011) 1294–1304. 10.1182/blood-2011-01-330530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [82].Arnold CN, Campbell DJ, Lipp M, Butcher EC, The germinal center response is impaired in the absence of T cell-expressed CXCR5, Eur. J. Immunol 37 (2007) 100–109. 10.1002/eji.200636486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [83].Kerfoot SM, Yaari G, Patel JR, Johnson KL, Gonzalez DG, Kleinstein SH, Haberman AM, Germinal Center B Cell and T Follicular Helper Cell Development Initiates in the Interfollicular Zone, Immunity. 34 (2011) 947–960. 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.03.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [84].Cremasco V, Woodruff MC, Onder L, Cupovic J, Nieves-Bonilla JM, Schildberg FA, Chang J, Cremasco F, Harvey CJ, Wucherpfennig K, Ludewig B, Carroll MC, Turley SJ, B cell homeostasis and follicle confines are governed by fibroblastic reticular cells, Nature Immunology. 15 (2014) 973–981. 10.1038/ni.2965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [85].Victora GD, Nussenzweig MC, Germinal Centers, Annual Review of Immunology. 40 (2022) 413–432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [86].Allen CDC, Okada T, Cyster JG, Germinal-Center Organization and Cellular Dynamics, Immunity. 27 (2007) 190–202. 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.07.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [87].Stebegg M, Bignon A, Hill DL, Silva-Cayetano A, Krueger C, Vanderleyden I, Innocentin S, Boon L, Wang J, Zand MS, Dooley J, Clark J, Liston A, Carr E, Linterman MA, Rejuvenating conventional dendritic cells and T follicular helper cell formation after vaccination, ELife. 9 (2020) e52473. 10.7554/eLife.52473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [88].Lefebvre JS, Lorenzo EC, Masters AR, Hopkins JW, Eaton SM, Smiley ST, Haynes L, Vaccine efficacy and T helper cell differentiation change with aging, Oncotarget. 7 (2016) 33581–33594. 10.18632/oncotarget.9254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [89].Luscieti P, Hubschmid T, Cottier H, Hess MW, Sobin LH, Human lymph node morphology as a function of age and site., Journal of Clinical Pathology. 33 (1980) 454–461. 10.1136/jcp.33.5.454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [90].Lazuardi L, Jenewein B, Wolf AM, Pfister G, Tzankov A, Grubeck-Loebenstein B, Age-related loss of naive T cells and dysregulation of T-cell/B-cell interactions in human lymph nodes, Immunology. 114 (2005) 37–43. 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2004.02006.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [91].Silva-Cayetano A, Fra-Bido S, Robert PA, Innocentin S, Burton AR, Watson EM, Lee JL, Webb LMC, Foster WS, McKenzie RCJ, Bignon A, Vanderleyden I, Alterauge D, Lemos JP, Carr EJ, Hill DL, Cinti I, Balabanian K, Baumjohann D, Espeli M, Meyer-Hermann M, Denton AE, Linterman MA, Spatial dysregulation of T follicular helper cells impairs vaccine responses in aging, Nat Immunol. (2023). 10.1038/s41590-023-01519-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [92].Eaton SM, Burns EM, Kusser K, Randall TD, Haynes L, Age-related Defects in CD4 T Cell Cognate Helper Function Lead to Reductions in Humoral Responses, Journal of Experimental Medicine. 200 (2004) 1613–1622. 10.1084/jem.20041395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [93].Katakai T, Marginal reticular cells: a stromal subset directly descended from the lymphoid tissue organizer, Front. Immun 3 (2012). 10.3389/fimmu.2012.00200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [94].Wang X, Cho B, Suzuki K, Xu Y, Green JA, An J, Cyster JG, Follicular dendritic cells help establish follicle identity and promote B cell retention in germinal centers, Journal of Experimental Medicine. 208 (2011) 2497–2510. 10.1084/jem.20111449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [95].Rodda LB, Bannard O, Ludewig B, Nagasawa T, Cyster JG, Phenotypic and Morphological Properties of Germinal Center Dark Zone Cxcl12 -Expressing Reticular Cells, The Journal of Immunology. 195 (2015) 4781–4791. 10.4049/jimmunol.1501191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [96].Barinov A, Luo L, Gasse P, Meas-Yedid V, Donnadieu E, Arenzana-Seisdedos F, Vieira P, Essential role of immobilized chemokine CXCL12 in the regulation of the humoral immune response, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 114 (2017) 2319–2324. 10.1073/pnas.1611958114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [97].Camara A, Cordeiro OG, Alloush F, Sponsel J, Chypre M, Onder L, Asano K, Tanaka M, Yagita H, Ludewig B, Flacher V, Mueller CG, Lymph Node Mesenchymal and Endothelial Stromal Cells Cooperate via the RANK-RANKL Cytokine Axis to Shape the Sinusoidal Macrophage Niche, Immunity. 50 (2019) 1467–1481.e6. 10.1016/j.immuni.2019.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [98].Yang C-Y, Vogt TK, Favre S, Scarpellino L, Huang H-Y, Tacchini-Cottier F, Luther SA, Trapping of naive lymphocytes triggers rapid growth and remodeling of the fibroblast network in reactive murine lymph nodes, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 111 (2014) E109–E118. 10.1073/pnas.1312585111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [99].Astarita JL, Cremasco V, Fu J, Darnell MC, Peck JR, Nieves-Bonilla JM, Song K, Kondo Y, Woodruff MC, Gogineni A, Onder L, Ludewig B, Weimer RM, Carroll MC, Mooney DJ, Xia L, Turley SJ, The CLEC-2–podoplanin axis controls the contractility of fibroblastic reticular cells and lymph node microarchitecture, Nat Immunol. 16 (2015) 75–84. 10.1038/ni.3035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [100].Acton SE, Onder L, Novkovic M, Martinez VG, Ludewig B, Communication, construction, and fluid control: lymphoid organ fibroblastic reticular cell and conduit networks, Trends in Immunology. 42 (2021) 782–794. 10.1016/j.it.2021.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [101].Novkovic M, Onder L, Bocharov G, Ludewig B, Topological Structure and Robustness of the Lymph Node Conduit System, Cell Reports. 30 (2020) 893–904.e6. 10.1016/j.celrep.2019.12.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [102].Katakai T, Hara T, Sugai M, Gonda H, Shimizu A, Lymph Node Fibroblastic Reticular Cells Construct the Stromal Reticulum via Contact with Lymphocytes, Journal of Experimental Medicine. 200 (2004) 783–795. 10.1084/jem.20040254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [103].Martinez VG, Pankova V, Krasny L, Singh T, Makris S, White IJ, Benjamin AC, Dertschnig S, Horsnell HL, Kriston-Vizi J, Burden JJ, Huang PH, Tape CJ, Acton SE, Fibroblastic Reticular Cells Control Conduit Matrix Deposition during Lymph Node Expansion, Cell Reports. 29 (2019) 2810–2822.e5. 10.1016/j.celrep.2019.10.103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [104].Masters AR, Hall A, Bartley JM, Keilich SR, Lorenzo EC, Jellison ER, Puddington L, Haynes L, Assessment of Lymph Node Stromal Cells as an Underlying Factor in Age-Related Immune Impairment, The Journals of Gerontology: Series A. 74 (2019) 1734–1743. 10.1093/gerona/glz029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [105].Abe J, Shichino S, Ueha S, Hashimoto S, Tomura M, Inagaki Y, Stein JV, Matsushima K, Lymph Node Stromal Cells Negatively Regulate Antigen-Specific CD4+ T Cell Responses, J.I 193 (2014) 1636–1644. 10.4049/jimmunol.1302946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [106].Cheng H-W, Onder L, Novkovic M, Soneson C, Lütge M, Pikor N, Scandella E, Robinson MD, Miyazaki J, Tersteegen A, Sorg U, Pfeffer K, Rülicke T, Hehlgans T, Ludewig B, Origin and differentiation trajectories of fibroblastic reticular cells in the splenic white pulp, Nat Commun. 10 (2019) 1739. 10.1038/s41467-019-09728-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [107].Assen FP, Abe J, Hons M, Hauschild R, Shamipour S, Kaufmann WA, Costanzo T, Krens G, Brown M, Ludewig B, Hippenmeyer S, Heisenberg C-P, Weninger W, Hannezo E, Luther SA, Stein JV, Sixt M, Multitier mechanics control stromal adaptations in the swelling lymph node, Nat Immunol. 23 (2022) 1246–1255. 10.1038/s41590-022-01257-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [108].Horsnell HL, Tetley RJ, De Belly H, Makris S, Millward LJ, Benjamin AC, Heeringa LA, de Winde CM, Paluch EK, Mao Y, Acton SE, Lymph node homeostasis and adaptation to immune challenge resolved by fibroblast network mechanics, Nat Immunol. 23 (2022) 1169–1182. 10.1038/s41590-022-01272-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [109].Estes JD, Reilly C, Trubey CM, Fletcher CV, Cory TJ, Piatak M, Russ S, Anderson J, Reimann TG, Star R, Smith A, Tracy RP, Berglund A, Schmidt T, Coalter V, Chertova E, Smedley J, Haase AT, Lifson JD, Schacker TW, Antifibrotic Therapy in Simian Immunodeficiency Virus Infection Preserves CD4+ T-Cell Populations and Improves Immune Reconstitution With Antiretroviral Therapy, The Journal of Infectious Diseases. 211 (2015) 744–754. 10.1093/infdis/jiu519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [110].Zeng M, Smith AJ, Wietgrefe SW, Southern PJ, Schacker TW, Reilly CS, Estes JD, Burton GF, Silvestri G, Lifson JD, Carlis JV, Haase AT, Cumulative mechanisms of lymphoid tissue fibrosis and T cell depletion in HIV-1 and SIV infections, J. Clin. Invest 121 (2011) 998–1008. 10.1172/JCI45157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [111].Huang L, Deng J, Xu W, Wang H, Shi L, Wu F, Wu D, Nei W, Zhao M, Mao P, Zhou X, CD8+ T cells with high TGF-β1 expression cause lymph node fibrosis following HIV infection, Mol Med Report. 18 (2018) 77–86. 10.3892/mmr.2018.8964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [112].Avraham T, Daluvoy S, Zampell J, Yan A, Haviv YS, Rockson SG, Mehrara BJ, Blockade of Transforming Growth Factor-β1 Accelerates Lymphatic Regeneration during Wound Repair, The American Journal of Pathology. 177 (2010) 3202–3214. 10.2353/ajpath.2010.100594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [113].Li X, Zhao J, Kasinath V, Uehara M, Jiang L, Banouni N, McGrath MM, Ichimura T, Fiorina P, Lemos DR, Shin SR, Ware CF, Bromberg JS, Abdi R, Lymph node fibroblastic reticular cells deposit fibrosis-associated collagen following organ transplantation, Journal of Clinical Investigation. (2020) 10.1172/JCI136618. 10.1172/JCI136618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [114].Suenaga F, Ueha S, Abe J, Kosugi-Kanaya M, Wang Y, Yokoyama A, Shono Y, Shand FHW, Morishita Y, Kunisawa J, Sato S, Kiyono H, Matsushima K, Loss of Lymph Node Fibroblastic Reticular Cells and High Endothelial Cells Is Associated with Humoral Immunodeficiency in Mouse Graft-versus-Host Disease, J.I 194 (2015) 398–406. 10.4049/jimmunol.1401022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [115].Choi SY, Bae H, Jeong S-H, Park I, Cho H, Hong SP, Lee D-H, Lee C, Park J-S, Suh SH, Choi J, Yang MJ, Jang JY, Onder L, Moon JH, Jeong H-S, Adams RH, Kim J-M, Ludewig B, Song J-H, Lim D-S, Koh GY, YAP/TAZ direct commitment and maturation of lymph node fibroblastic reticular cells, Nat Commun. 11 (2020) 519. 10.1038/s41467-020-14293-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [116].Hadamitzky C, Spohr H, Debertin AS, Guddat S, Tsokos M, Pabst R, Age-dependent histoarchitectural changes in human lymph nodes: an underestimated process with clinical relevance?, Journal of Anatomy. 216 (2010) 556–562. 10.1111/j.1469-7580.2010.01213.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [117].Kityo C, Makamdop KN, Rothenberger M, Chipman JG, Hoskuldsson T, Beilman GJ, Grzywacz B, Mugyenyi P, Ssali F, Akondy RS, Anderson J, Schmidt TE, Reimann T, Callisto SP, Schoephoerster J, Schuster J, Muloma P, Ssengendo P, Moysi E, Petrovas C, Lanciotti R, Zhang L, Arévalo MT, Rodriguez B, Ross TM, Trautmann L, Sekaly R-P, Lederman MM, Koup RA, Ahmed R, Reilly C, Douek DC, Schacker TW, Lymphoid tissue fibrosis is associated with impaired vaccine responses, Journal of Clinical Investigation. 128 (2018) 2763–2773. 10.1172/JCI97377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [118].Bekkhus T, Olofsson A, Sun Y, Magnusson PU, Ulvmar MH, Stromal transdifferentiation drives lipomatosis and induces extensive vascular remodeling in the aging human lymph node, The Journal of Pathology. (2022) path.6030. 10.1002/path.6030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [119].Randolph GJ, Ivanov S, Zinselmeyer BH, Scallan JP, The Lymphatic System: Integral Roles in Immunity, Annu. Rev. Immunol 35 (2017) 31–52. 10.1146/annurev-immunol-041015-055354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [120].Ivanov S, Scallan JP, Kim K-W, Werth K, Johnson MW, Saunders BT, Wang PL, Kuan EL, Straub AC, Ouhachi M, Weinstein EG, Williams JW, Briseño C, Colonna M, Isakson BE, Gautier EL, Förster R, Davis MJ, Zinselmeyer BH, Randolph GJ, CCR7 and IRF4-dependent dendritic cells regulate lymphatic collecting vessel permeability, Journal of Clinical Investigation. 126 (2016) 1581–1591. 10.1172/JCI84518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]