Abstract

Objective

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) prognosis involves multiple clinical factors. Although nomogram models targeting various clinical factors have been reported in early and locally advanced HCC, there are currently few studies on complete and effective prognostic nomogram models for stage IV HCC patients. This study aims to creat nomograms for cancer-specific survival (CSS) in patients at stage IV of HCC and developing a web predictive nomogram model to predict patient prognosis and guide individualized treatment.

Methods

Clinicopathological information on stage IV of HCC between January, 2010 and December, 2015 was collected from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database. The patients at stage IV of HCC were categorized into IVA (without distant metastases) and IVB (with distant metastases) subgroups based on the presence of distant metastasis, and then the patients from both IVA and IVB subgroups were randomly divided into the training and validation cohorts in a 7꞉3 ratio. Univariate and multivariate Cox regression analyses were used to analyze the independent risk factors that significantly affected CSS in the training cohort, and constructed nomogram models separately for stage IVA and stage IVB patients based on relevant independent risk factors. Two nomogram’s accuracy and discrimination were evaluated by receiver operator characteristic (ROC) curves and calibration curves. Furthermore, web-based nomogram models were developed specifically for stage IVA and stage IVB HCC patients by R software. A decision analysis curve (DCA) was used to evaluate the clinical utility of the web-based nomogram models.

Results

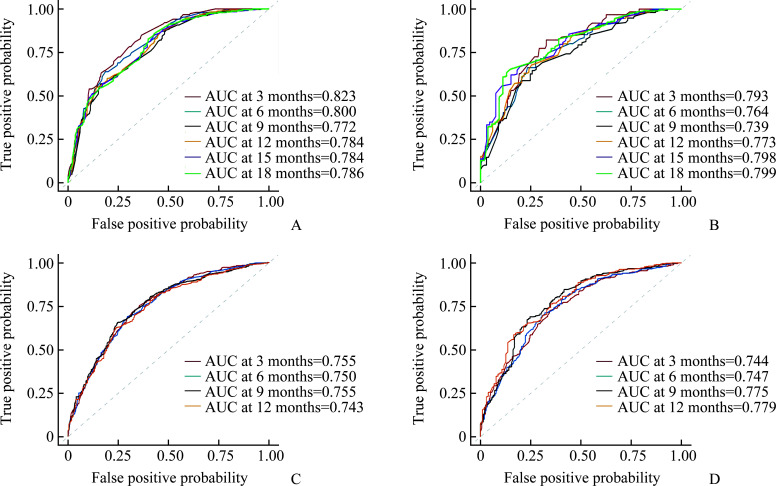

A total of 3 060 patients were included in this study, of which 883 were in stage IVA, and 2 177 were in stage IVB. Based on multivariate analysis results, tumor size, alpha-fetoprotein (AFP), T stage, histological grade, surgery, radiotherapy, and chemotherapy were independent prognostic factors for patients with stage IVA of HCC; and tumor size, AFP, T stage, N stage, histological grade, lung metastasis, surgery, radiotherapy, and chemotherapy were independent prognostic factors for patients with stage IVB HCC. In stage IVA patients, the 3-, 6-, 9-, 12-, 15-, and 18-month areas under the ROC curves for the training cohort were 0.823, 0.800, 0.772, 0.784, 0.784, and 0.786, respectively; and the 3-, 6-, 9-, 12-, 15-, and 18-month areas under the ROC curves for the validation cohort were 0.793, 0.764, 0.739, 0.773, 0.798, and 0.799, respectively. In stage IVB patients, the 3-, 6-, 9-, and 12-month areas under the ROC curves for the training cohort were 0.756, 0.750, 0.755, and 0.743, respectively; and the 3-, 6-, 9-, and 12-month areas under the ROC curves for the validation cohort were 0.744, 0.747, 0.775, and 0.779, respectively; showing that the nomograms had an excellent predictive ability. The calibration curves showed a good consistency between the predictions and actual observations.

Conclusion

Predictive nomogram models for CSS in stage IVA and IVB HCC patients are developed and validated based on the SEER database, which might be used for clinicians to predict the prognosis, implement individualized treatment, and follow up those patients.

Keywords: hepatocellular carcinoma, SEER database, cancer-specific survival, nomogram

Abstract

目的

肝细胞癌(hepatocellular carcinoma,HCC)的预后涉及多个临床因素。尽管目前针对多个临床因素的列线图模型在早期及局部晚期HCC中已有报道,但是鲜有完整有效的IV期HCC患者预后列线图模型的报道。本研究旨在创建预测IV期HCC患者癌症特异性生存期(cancer-specific survival,CSS)的列线图,开发网络预测列线图模型,用于预测患者预后及指导个体化治疗。

方法

从监测、流行病学和最终结果(Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results,SEER)数据库中收集2010年1月至2015年12月IV期HCC患者的临床病理信息,根据有无远处转移将IV期HCC患者分为IVA(无远处转移)和IVB(有远处转移)期2个亚组,然后将IVA和IVB期患者均按照7꞉3的比例随机分配到训练队列或验证队列。采用单因素和多因素Cox回归分析训练队列中显著影响CSS的独立危险因素,并根据相关的独立危险因素分别构建针对IVA期和IVB期HCC患者的列线图。通过受试者操作特征(receiver operator characteristic,ROC)曲线和校准曲线来评估2个列线图的准确性和辨别能力。此外,利用R软件开发分别针对IVA期和IVB期HCC患者的网络列线图模型。采用决策分析曲线(decision analysis curve,DCA)评估网络列线图的临床预测效果。

结果

本研究共纳入3 060例患者,其中IVA期883例,IVB期2 177例。多因素分析结果显示:肿瘤大小、甲胚蛋白(alpha-fetoprotein,AFP)、T分期、组织学分级、手术、放射治疗、化学治疗是IVA期HCC患者的独立预后因素;肿瘤大小、AFP、T分期、N分期、组织学分级、肺转移、手术、放射治疗和化学治疗是IVB期HCC患者的独立预后因素。在IVA期患者中,训练队列的3、6、9、12、15和18个月ROC曲线下面积分别为0.823、0.800、0.772、0.784、0.784和0.786;验证队列的3、6、9、12、15和18个月ROC曲线下面积分别为0.793、0.764、0.739、0.773、0.798和0.799。在IVB期患者中,训练队列的3、6、9和12个月ROC曲线下面积分别为0.756、0.750、0.755和0.743;验证队列的3、6、9和12个月ROC曲线下面积分别为0.744、0.747、0.775和0.779;表明列线图具有出色的预测能力。校准曲线显示预测结果与实际观察结果吻合良好。

结论

本研究开发并验证的基于SEER数据库的IVA和IVB期HCC患者CSS的预测列线图模型,可以被临床医生用来预测这些患者的预后、实施个体化治疗和随访管理。

Keywords: 肝细胞癌, SEER数据库, 癌症特异性生存期, 列线图

Primary liver cancer is the third most common cause of cancer-related death among the 6 most common cancers in the world[1]. More than 75% of primary liver cancers are hepatocellular carcinomas (HCC)[2]. It is estimated that only 20% to 35% of HCC patients are diagnosed in an early stage, despite improvements in diagnostic techniques, which means 65%-80% of patients are diagnosed at an advanced stage[3]. Due to the insidious onset and high metastatic potential of HCC, more than 30% of patients already have extrahepatic metastases at the first diagnosis[4]. According to the research[5] report, the 5-year survival rate for the early-stage HCC patients after the treatment with liver transplantation or tumor resection could be up to 60%. However, only 5%-15% of the early-stage HCC patients have an opportunity to receive surgical treatment[6]. Unfortunately, study[7] has shown that the 1-, 2-, and 3-year overall survival (OS) rates for the most advanced HCC patients are 29%, 16%, and 8%, respectively. Based on the characteristics of low early diagnosis rate and poor prognosis of advanced HCC, accurate assessment of the prognosis of those patients not only helps doctors make better decisions, but also helps alleviate the pain and economic burden of patients.

There are many factors that affect the prognosis of HCC, such as the patient’s age, gender, histological grade[8], tumor size[9], chemotherapy[10], surgery[11], and radiation therapy[12]. Some studies[13-18] have constructed nomogram models for the early-stage and advanced HCC based on the above factors. However, there is no complete and valid prognostic nomogram model for stage IV HCC patients. Based on the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database from the United States, we tried to develop and validate prediction nomogram models for the cancer-specific survival (CSS) of stage IVA and IVB HCC patients, which might be helpful for clinicians to predict the prognosis of those patients and implement individualized treatment.

1. Materials and methods

1.1. Material and data extraction

In the present study, we used SEER*Stat 8.4.0.1 software to collect clinicopathological information on stage IV HCC between January 2010 to December 2015 from the SEER database, such as baseline demographics (age, race, sex, year of diagnosis, and marriage), tumor characteristics (histological grade, fibrosis score, tumor size, T stage, N stage, brain metastasis, bone metastasis, and lung metastasis), treatment information(chemotherapy, surgery, and radiation), survival time, and survival status. There was no need for informed consent or approval from an institutional review board since the SEER database was publicly accessible. Our analysis followed usage rules of the SEER database data.

1.2. Inclusion criteria and exclusion criteria

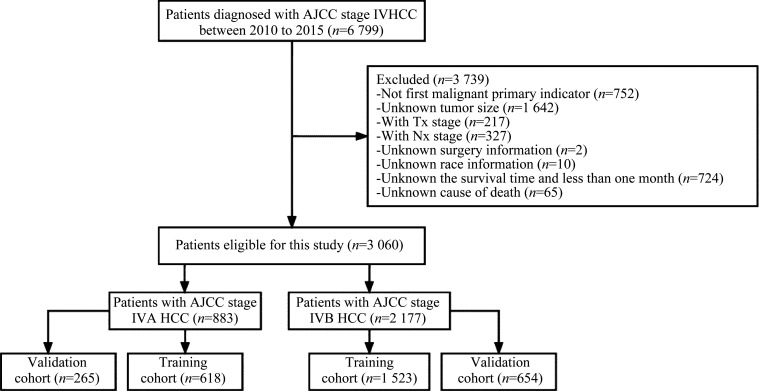

Inclusion criteria: 1) Diagnosed as stage IV HCC between January 2010 to December 2015 with known age; 2) international Classification of Diseases for Oncology, 3rd Edition [ICD-O-3] code 8170 to 8175. Exclusion criteria: 1) Not first malignant primary indicator; 2) unknown tumor size; 3) patients with Tx (x indicates that the primary lesion cannot be evaluated) stage; 4) patients with Nx stage; 5) unknown surgical information; 6) unknown race information; 7) unknown the survival time or less than one month; 8) unknown cause of death. The flowchart for patient selection is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Flow chart of patient’s screening.

1.3. Cancer stage definition

By the 8th edition of the American Joint Commission on Cancer staging (AJCC 8th), stage IVA HCC is defined as having regional lymph node metastases without distant metastases (IVA: T1-4; N1; M0); and stage IVB HCC refers to patients with distant metastases, whether or not lymph nodes were involved (IVB: T1-4; N0-1; M1).

1.4. Statistical analysis

Through univariate and multivariate Cox regression analysis, we obtained the independent risk factors (P<0.05) that significantly affected CSS, and the nomogram was constructed based on all independent risk factors to predict the patient’s prognosis. We tested the nomogram’s accuracy and discrimination by using a series of validation methods, including the area under the receiver operator characteristic (ROC) curve, and the calibration curve. The decision curve analysis (DCA) was used to evaluate the clinical practicability of our nomogram. In addition, based on our nomogram, we developed web nomogram models for CSS prediction through R software (version 4.1.1). SPSS (version 25.0) was used for all statistical analyses. A P<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

AJCC: American Joint Committee on cancer; HCC: Hepatocellular carcinoma.

2. Results

2.1. Patient demographic and clinical characteristics

A total of 3 060 patients were included, of which 883 were in stage IVA and 2 177 were in stage IVB. The median CSS and the interquartile range (IQR) for the entire stage IVA HCC patients were 6.0 months and 3.0-17.0 months, respectively. The median CSS and the IQR for the entire stage IVB HCC patients were 4.0 months and 2.0-9.0 months, respectively. Patients in both groups of stage IVA and IVB were randomly assigned to either the training cohort (70%) or the validation cohort (30%). In both training and validation cohorts, there were no statistically significant differences (P>0.05) in demographic and clinical characteristics except for fibrosis in stage IVA patients. The characteristics of HCC patients are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographics and clinical characteristics of stage IVA and stage IVB HCC patients at diagnosis

| Variables | AJCC stage IVA | AJCC stage IVB | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Training cohort (n=618)/[No.(%)] |

Validation cohort (n=265)/[No.(%)] |

P |

Training cohort (n=1 523)/[No.(%)] |

Validation cohort (n=654)/[No.(%)] |

P | |

| Age/year | 1.000 | 0.149 | ||||

| <65 | 246(39.8) | 105(39.6) | 946(62.1) | 384(68.7) | ||

| ≥65 | 372(60.2) | 160(60.4) | 577(37.9) | 270(41.3) | ||

| Sex | 0.536 | 0.635 | ||||

| Female | 111(18.0) | 53(20.0) | 292(19.2) | 119(18.2) | ||

| Male | 507(82.0) | 212(80.0) | 1 231(80.8) | 535(81.8) | ||

| Race | 0.683 | 0.691 | ||||

| White | 427(69.1) | 189(71.4) | 998(65.5) | 441(67.4) | ||

| Black | 103(16.7) | 38(14.3) | 258(17.0) | 105(16.1) | ||

| Others* | 88(14.2) | 38(14.3) | 267(17.5) | 108(16.5) | ||

Table 1.

| Variable | AJCC stage IVA | AJCC stage IVB | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Training cohort (n=618)/[No.(%)] |

Validation cohort (n=265)/[No.(%)] |

P |

Training cohort (n=1 523)/[No.(%)] |

Validation cohort (n=654)/[No.(%)] |

P | |

| Marital status | 0.135 | 0.934 | ||||

| Single | 155(25.1) | 64(24.1) | 380(25.0) | 168(25.7) | ||

| Married | 283(45.8) | 139(52.5) | 710(46.6) | 301(46.0) | ||

| Others† | 180(29.1) | 62(23.4) | 433(28.4) | 185(28.3) | ||

| Tumor grade | 0.212 | 0.207 | ||||

| I/II | 121(19.6) | 65(24.6) | 328(21.5) | 120(18.3) | ||

| III/IV | 71(11.5) | 25(9.4) | 196(12.9) | 82(12.5) | ||

| Unknown | 426(68.9) | 175(66.0) | 999(65.6) | 452(69.2) | ||

| Fibrosis | <0.001 | 0.844 | ||||

| No | 38(6.1) | 9(3.4) | 77(5.1) | 37(5.7) | ||

| Yes | 147(23.8) | 38(14.3) | 279(18.3) | 120(18.3) | ||

| Unknown | 433(70.1) | 218(82.3) | 1 167(76.6) | 497(76.0) | ||

| AFP | 0.591 | 0.754 | ||||

| Negative | 94(15.2) | 42(15.8) | 201(13.2) | 85(13.0) | ||

| Positive | 454(73.5) | 187(70.6) | 1 061(69.7) | 465(71.1) | ||

| Unknown | 70(11.3) | 36(13.6) | 261(17.1) | 104(15.9) | ||

| Tumor size/cm | 0.693 | 0.891 | ||||

| ≤5 | 483(48.1) | 82(30.9) | 427(28.0) | 178(27.2) | ||

| >5-10 | 362(36.1) | 116(43.8) | 618(40.6) | 272(41.6) | ||

| >10 | 159(15.8) | 67(25.3) | 478(31.4) | 204(31.2) | ||

| T stage | 0.865 | 0.774 | ||||

| T1 | 131(21.2) | 59(22.3) | 376(24.7) | 154(23.5) | ||

| T2 | 124(20.1) | 47(17.7) | 229(15.0) | 107(16.4) | ||

| T3 | 319(51.6) | 141(53.2) | 749(49.2) | 326(49.8) | ||

| T4 | 44(7.1) | 18(6.8) | 169(11.1) | 67(10.3) | ||

| N stage | 0.655 | |||||

| N0 | 0(0) | 0(0) | 1 069(70.2) | 466(71.3) | ||

| N1 | 618(100.0) | 265(100.0) | 454(29.8) | 188(28.7) | ||

| Bone metastasis | 0.835 | |||||

| No/Unknown | 1 075(70.6) | 458(70.0) | ||||

| Yes | 448(29.4) | 196(30.0) | ||||

| Brain metastasis | 0.327 | |||||

| No/Unknown | 1 497(98.3) | 638(97.6) | ||||

| Yes | 26(1.7) | 16(2.4) | ||||

| Lung metastasis | 0.870 | |||||

| No/Unknown | 983(64.5) | 419(64.1) | ||||

| Yes | 540(35.5) | 235(35.9) | ||||

| Surgery | 0.239 | 0.815 | ||||

| No | 554(89.6) | 245(92.5) | 1 436(94.3) | 619(94.6) | ||

| Yes | 64(10.4) | 20(7.5) | 87(5.7) | 35(5.4) | ||

| Chemotherapy | 0.685 | 0.457 | ||||

| No/Unknown | 279(45.1) | 115(43.4) | 745(48.9) | 332(50.8) | ||

| Yes | 339(54.9) | 150(56.6) | 778(51.1) | 322(49.2) | ||

| Radiation | 1.000 | 0.723 | ||||

| No | 546(88.3) | 234(88.3) | 1 199(78.7) | 520(79.5) | ||

| Yes | 72(11.7) | 31(11.7) | 324(21.3) | 134(20.5) | ||

*American Indian/AK Native/Asian/Pacific Islander; †Divorced/separated/Widowed. IVA: Stage IV without distant metastases; IVB: Stage IV with distant metastases; HCC: Hepatocellular carcinoma; AJCC: American Joint Committee on Cancer; AFP: Alpha-fetoprotein.

continued

2.2. Univariate and multivariate Cox regression analysis

Univariate and multivariate Cox regression analyses were used to determine the independent prognostic factors for 2 training cohorts. Tumor size, alpha-fetoprotein (AFP), T stage, histological grade, surgery, radiotherapy, and chemotherapy were independent prognostic factors (P<0.05) for stage IVA HCC patients (Table 2). Tumor size, AFP, T stage, N stage, histological grade, lung metastasis, surgery, radiotherapy, and chemotherapy were independent prognostic factors (P<0.05) for stage IVB HCC patients (Table 3). These prognostic factors were used to construct our nomogram.

Table 2.

Univariate and multivariate analyses of stage IVA HCC patients in the training cohort

| Variables | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 95% CI | P | HR | 95% CI | P | ||

| Age/years | |||||||

| <65 | Reference | ||||||

| ≥65 | 1.15 | 0.97-1.36 | 0.111 | ||||

| Sex | |||||||

| Female | Reference | ||||||

| Male | 0.93 | 0.75-1.16 | 0.523 | ||||

| Race | |||||||

| White | Reference | ||||||

| Black | 1.15 | 0.92-1.45 | 0.214 | ||||

| Others* | 1.01 | 0.80-1.29 | 0.911 | ||||

| Marital status | |||||||

| Single | Reference | ||||||

| Married | 1.02 | 0.83-1.26 | 0.837 | ||||

| Others† | 1.23 | 0.98-1.53 | 0.076 | ||||

| Tumor grade | |||||||

| I/II | Reference | Reference | |||||

| III/IV | 1.55 | 1.14-2.11 | 0.005 | 1.43 | 1.05-1.96 | 0.024 | |

| Unknown | 1.23 | 0.99-1.53 | 0.057 | 0.96 | 0.77-1.20 | 0.721 | |

| Fibrosis | |||||||

| No | Reference | ||||||

| Yes | 1.26 | 0.86-1.85 | 0.231 | ||||

| Unknown | 1.26 | 0.89-1.80 | 0.196 | ||||

| AFP | |||||||

| Negative | Reference | Reference | |||||

| Positive | 1.54 | 1.22-1.96 | <0.001 | 1.22 | 0.96-1.56 | 0.106 | |

| Unknown | 1.80 | 1.30-2.50 | <0.001 | 1.55 | 1.10-2.17 | 0.011 | |

| Tumor size/cm | |||||||

| ≤5 | Reference | Reference | |||||

| >5-10 | 1.43 | 1.18-1.74 | <0.001 | 1.12 | 0.89-1.42 | 0.329 | |

| >10 | 1.60 | 1.28-2.00 | <0.001 | 1.33 | 1.02-1.72 | 0.032 | |

| T stage | |||||||

| T1 | Reference | Reference | |||||

| T2 | 0.99 | 0.76-1.29 | 0.948 | 1.09 | 0.83-1.43 | 0.522 | |

| T3 | 1.69 | 1.36-2.10 | <0.001 | 1.60 | 1.25-2.04 | <0.001 | |

| T4 | 2.19 | 1.54-3.13 | <0.001 | 2.09 | 1.43-3.05 | <0.001 | |

Table 3.

Univariate and multivariate analyses of stage IVB HCC patients in the training cohort

| Variables | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 95% CI | P | HR | 95% CI | P | |

| Age/year | ||||||

| <65 | Reference | |||||

| ≥65 | 1.1 | 0.99-1.22 | 0.087 | |||

| Sex | ||||||

| Female | Reference | |||||

| Male | 0.96 | 0.84-1.10 | 0.559 | |||

| Race | ||||||

| White | Reference | Reference | ||||

| Black | 1.04 | 0.91-1.20 | 0.566 | 0.98 | 0.86-1.13 | 0.824 |

| Others* | 1.18 | 1.03-1.36 | 0.017 | 1.11 | 0.96-1.28 | 0.147 |

| Marital status | ||||||

| Single | Reference | |||||

| Married | 0.96 | 0.85-1.09 | 0.525 | |||

| Others† | 1.01 | 0.88-1.16 | 0.900 | |||

| Tumor grade | ||||||

| I/II | Reference | Reference | ||||

| III/IV | 1.55 | 1.29-1.85 | <0.001 | 1.53 | 1.27-1.83 | <0.001 |

| Unknown | 1.26 | 1.11-1.44 | <0.001 | 1.13 | 0.99-1.28 | 0.064 |

| Fibrosis | ||||||

| No | Reference | |||||

| Yes | 1.08 | 0.83-1.40 | 0.581 | |||

| Unknown | 1.18 | 0.93-1.50 | 0.163 | |||

| AFP | ||||||

| Negative | Reference | Reference | ||||

| Positive | 1.40 | 1.20-1.64 | <0.001 | 1.37 | 1.17-1.60 | 0.001 |

| Unknown | 1.36 | 1.13-1.64 | 0.001 | 1.31 | 1.09-1.59 | 0.005 |

| Tumor size/cm | ||||||

| ≤5 | Reference | Reference | ||||

| >5-10 | 1.28 | 1.13-1.46 | <0.001 | 1.19 | 1.01-1.39 | 0.038 |

| >10 | 1.46 | 1.27-1.67 | <0.001 | 1.35 | 1.14-1.60 | <0.001 |

Table 2.

| Variables | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 95% CI | P | HR | 95% CI | P | ||

| Surgery | |||||||

| No | Reference | Reference | |||||

| Yes | 0.29 | 0.21-0.39 | <0.001 | 0.27 | 0.19-0.37 | <0.001 | |

| Chemotherapy | |||||||

| No/Unknown | Reference | Reference | |||||

| Yes | 0.66 | 0.56-0.78 | <0.001 | 0.57 | 0.48-0.68 | <0.001 | |

| Radiation | |||||||

| No | Reference | Reference | |||||

| Yes | 0.61 | 0.46-0.79 | <0.001 | 0.48 | 0.37-0.63 | <0.001 | |

*American Indian/AK Native/Asian/Pacific Islander; †Divorced/separated/Widowed. IVA: Stage IV without distant metastases; HCC: Hepatocellular carcinoma.

continued

Table 3.

| Variables | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 95% CI | P | HR | 95% CI | P | |

| T stage | ||||||

| T1 | Reference | Reference | ||||

| T2 | 1.06 | 0.90-1.26 | 0.482 | 1.22 | 1.01-1.47 | 0.039 |

| T3 | 1.40 | 1.23-1.59 | <0.001 | 1.32 | 1.15-1.51 | 0.001 |

| T4 | 1.40 | 1.16-1.68 | <0.001 | 1.18 | 0.97-1.43 | 0.094 |

| N stage | ||||||

| N0 | Reference | Reference | ||||

| N1 | 1.20 | 1.07-1.34 | 0.001 | 1.15 | 1.03-1.30 | 0.017 |

| Bone metastasis | ||||||

| No/Unknown | Reference | |||||

| Yes | 0.98 | 0.87-1.09 | 0.689 | |||

| Brain metastasis | ||||||

| No/Unknown | Reference | |||||

| Yes | 1.15 | 0.78-1.69 | 0.492 | |||

| Lung metastasis | ||||||

| No/Unknown | Reference | Reference | ||||

| Yes | 1.28 | 1.15-1.43 | <0.001 | 1.21 | 1.08-1.36 | <0.001 |

| Surgery | ||||||

| No | Reference | Reference | ||||

| Yes | 0.41 | 0.32-0.52 | <0.001 | 0.41 | 0.32-0.52 | <0.001 |

| Chemotherapy | ||||||

| No/Unknown | Reference | Reference | ||||

| Yes | 0.61 | 0.55-0.68 | <0.001 | 0.58 | 0.52-0.64 | <0.001 |

| Radiation | ||||||

| No | Reference | Reference | ||||

| Yes | 0.70 | 0.62-0.79 | <0.001 | 0.75 | 0.66-0.85 | <0.001 |

*American Indian/AK Native/Asian/Pacific Islander; †Divorced/separated/Widowed. IVB: Stage IV with distant metastases; HCC: Hepatocellular carcinoma.

continued

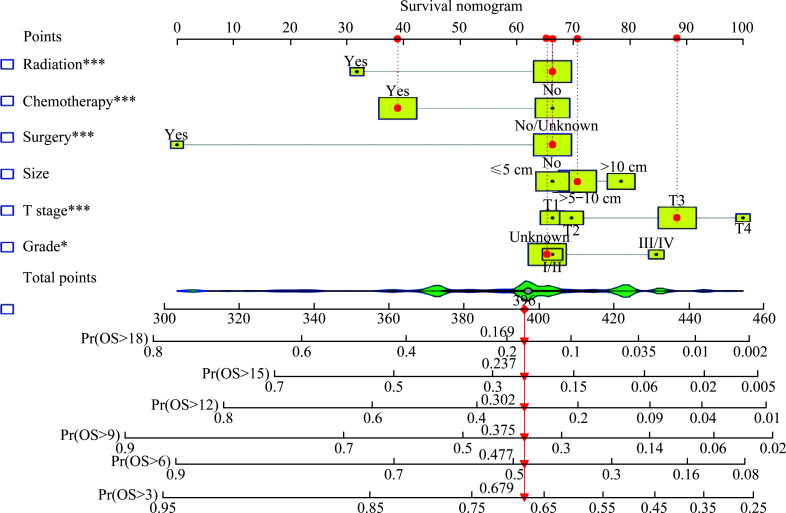

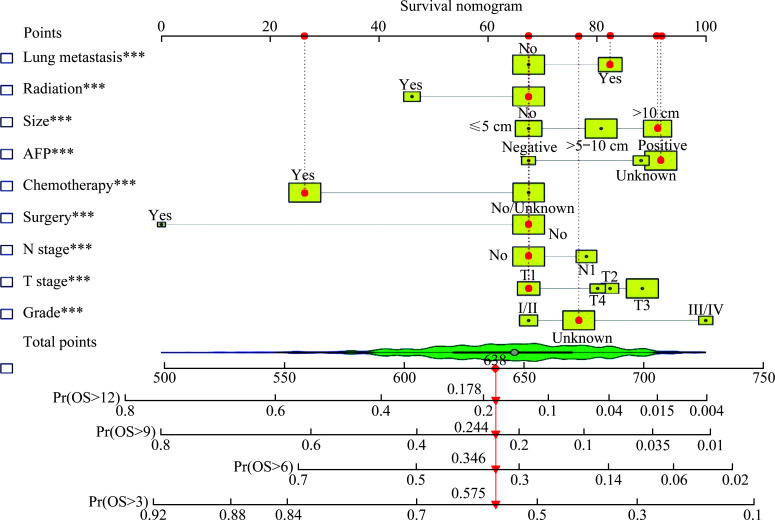

2.3. Nomogram construction

Based on the above independent prognostic factors, we constructed nomograms for predicting CSS probabilities in stage IVA patients (Figure 2) and IVB HCC patients (Figure 3), respectively. Each prognostic variable was scored based on its prognostic value, and the total score of each HCC patient was used to predict CSS in the corresponding month.

Figure 2. Nomogram of CSS in stage IVA HCC patients at 3-, 6-, 9-, 12-, 15-, and 18-month.

*P<0.05, ***P<0.001. CSS: Cancer-specific survival; IVA: Stage IV without distant metastases; HCC: Hepatocellular carcinoma.

Figure 3. Nomogram of CSS in stage IVB HCC patients at 3-, 6-, 9-, and 12-month.

***P<0.001. CSS: Cancer-specific survival; IVB: Stage IV with distant metastases; HCC: Hepatocellular carcinoma.

2.4. Nomogram validation

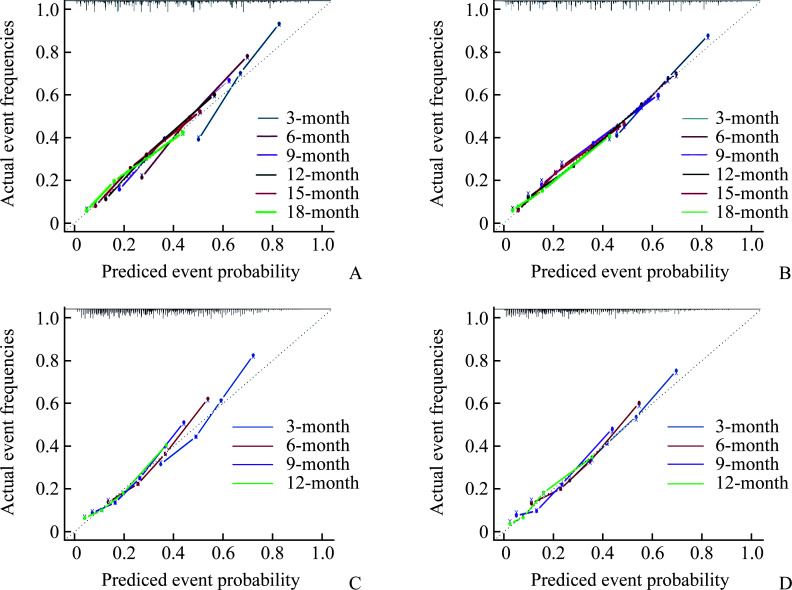

The ROC curves of 2 nomograms for predicting CSS in stage IVA and stage IVB HCC patients are shown in Figure 4. In stage IVA patients (Figure 4A, 4B), the 3-, 6-, 9-, 12-, 15-, and 18-month areas under the ROC curves for the training cohort were 0.823, 0.800, 0.772, 0.784, 0.784, and 0.786, respectively; and the 3-, 6-, 9-, 12-, 15-, and 18-month areas under the ROC curves for the validation cohort were 0.793, 0.764, 0.739, 0.773, 0.798, and 0.799, respectively. In stage IVB patients (Figure 4C, 4D), the 3-, 6-, 9-, and 12-month areas under the ROC curves for the training cohort were 0.756, 0.750, 0.755, and 0.743, respectively; and the 3-, 6-, 9-, and 12-month areas under the ROC curves for the validation cohort were 0.744,0.747,0.775, and 0.779, respectively. Furthermore, in the 2 nomograms, the calibration curves show good consistency between the training cohort and validation cohort (Figure 5).

Figure 4. ROC curves of the nomogram.

A and B: AUCs for predicting CSS in training cohort (A) and validation cohort (B) of stage IVA HCC patients; C and D: AUCs for predicting CSS in training cohort (C) and validation cohort (D) of stage IVB HCC patients. ROC: Receiver operator characteristic; AUC: Area under the curve; CSS: Cancer-specific survival; IVA: Stage IV without distant metastases; IVB: Stage IV with distant metastases; HCC: Hepatocellular carcinoma.

Figure 5. Calibration curves of the nomogram.

A and B: Calibration curves of the 3-, 6-, 9-, 12-, 15-, and 18- month predicting CSS in training cohort (A) and validation cohort (B) of stage IVA HCC patients; C and D: Calibration curves of the 3-, 6-, 9-, and 12- month predicting CSS in training cohort (C) and validation cohort (D) of stage IVB HCC patients. CSS: Cancer-specific survival; IVA: Stage IV without distant metastases; IVB: Stage IV with distant metastases; HCC: Hepatocellular carcinoma.

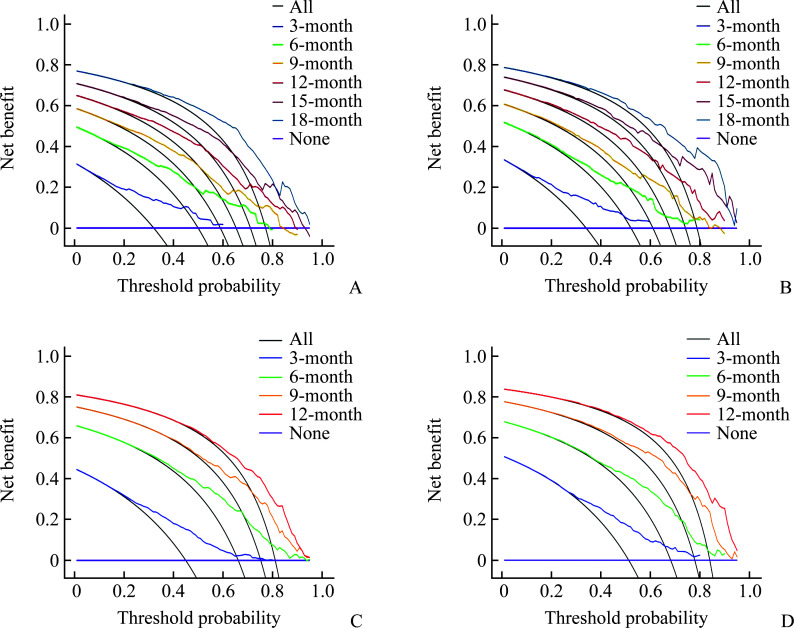

2.5. Clinical utility

DCA curves were used to evaluate the clinical utility of the nomograms. Both in patients with stage IVA HCC and stage IVB HCC, the nomogram-related

DCA curves in both the training and validation cohorts showed excellent clinical application prospects and good positive net benefit (Figure 6).

Figure 6. DCA curves of the nomogram.

A and B: DCA curves of the 3-, 6-, 9-, 12-, 15-, and 18- month predicting CSS in training cohort (A) and validation cohort (B) of stage IVA HCC patients; C and D: the calibration curves of the 3-, 6-, 9-, and 12- month predicting CSS in training cohort (C) and validation cohort (D) of stage IVB HCC patients. DCA: Decision curve analysis; CSS: Cancer-specific survival; IVA: Stage IV without distant metastases; IVB: Stage IV with distant metastases; HCC: Hepatocellular carcinoma.

2.6. Developed web nomogram

Based on the 2 nomograms, we developed web nomogram models for predicting CSS in stage IVA HCC and stage IVB HCC patients. When patient’s characteristics is input, the estimated survival probability is displayed immediately. For example, we evaluated an inoperable HCC patient in stage IVA (T3N1M0) with tumor size of 85 mm and unknown degree of differentiation. If the patient received only chemotherapy (curve B in Figure 7), the estimated survival probability for this patient at 3-, 6-,9-, 12-, 15-, and 18 months was 68.0% (63.0%-73.0%), 48.0% (42.0%-55.0%), 38.0% (31.6%-45.0%), 30.2% (24.5%- 37.0%), 23.7% (18.4%-30.4%), and 16.9% (12.5%- 23.0%), respectively; while if the patient received chemotherapy combined with radiation therapy (curve A in Figure 7), the estimated survival probability for this patient at 3-, 6-, 9-, 12-, 15-, and 18 months was 83.0% (78.0%-88.0%), 70.0% (63.0%-78.0%), 62.0% (54.0%- 72.0%), 56.0% (47.0%-66.0%), 50.0% (40.0%-61.0%), and 42.0% (33.0%-54.0%), respectively.

Figure 7. A web nomogram for predicting CSS for patients with stage IVA HCC.

CSS: Cancer-specific survival; IVA: Stage IV without distant metastases; HCC: Hepatocellular carcinoma.

The nomograms are accessible at websites (https://zhangouling.shinyapps.io/VIA-HCC-prediction/ and https://zhangouling.shinyapps.io/IVB-HCC-prediction/).

3. Discussion

HCC incidence and mortality continue to rise worldwide[19]. Patients with early-stage HCC usually have no obvious clinical symptoms, as a result, most patients have developed advanced HCC at the time of diagnosis[20]. However, so far, there is no complete and valid prognostic nomogram model for patients with stage IV HCC due to the lack of a large cohort of clinical prognostic models. Therefore, we developed and validated 2 nomogram models for the stage IVA and IVB HCC patients based on the SEER database, and developed web prediction nomogram models, which might be helpful for clinicians to predict the prognosis of those patients and make better clinical decisions.

By univariate and multivariate Cox regression analysis of this study, a total of 6 independent risk factors (including tumor size, T stage, grade, surgery, radiotherapy, and chemotherapy) affecting CSS in patients with stage IVA HCC and 9 independent risk factors (including tumor size, AFP, T stage, N stage, histological grade, lung metastasis, surgery, radiotherapy, and chemotherapy) affecting CSS in patients with stage IVB HCC were identified. These prognostic factors were used to construct 2 nomograms.

Demographic and social variables (race, age, and marital status) were regarded as prognostic factors of HCC and have been reported in many studies. Younger patients had longer CSS according to previous studies[21-22]. Race is currently a controversial prognostic factor. Some previous studies[15, 22-23] have shown that black people have shorter CSS than white people, while other races (Pacific Islander/Asian/Alaska Native/American Indian) have longer CSS than white and black people, another early study[24] showed that there are not significant difference in survival time between white and black patients, while our study showed that no significant difference in CSS between patients of different ethnicities. Although there are reports indicating a higher survival rates in married HCC patients[14, 21], our study showed no significant difference between patients with different marital statuses in CSS. In agreement with prior studies[15, 25-26], sex was not considered a prognostic factor. In our study, the above demographic and sociological factors were not statistically different between IVA and IVB HCC patients, which probably due to the rapid progression and the death of stage IV HCC and the statistical differences were not well represented.

For tumor feature variables in our study, T stage, histological grade, AFP, and tumor size were identified as independent influencing factors for CSS in HCC patients, regardless of whether patients were in stage IVA or IVB. Higher T stage[14, 21], larger tumor size[14, 21], poor differentiation[14, 21], and AFP positive[27] of HCC patients were associated with shorter CSS. Similar to previous studies[18], we found the fibrosis score was not a risk factor for patients with stage IVA or IVB, which might be stage IV HCC with the characteristics of extensive invasiveness and rapid progression, and liver fibrosis has no chance to develop into cirrhosis[28], while liver fibrosis does not affect survival before developing into cirrhosis. In addition, lung metastases and the N1 stage are poor prognostic factors in patients with stage IVB, which is consistent with the findings of Yang, et al[17] and Zhang, et al[18].

In patients with stage IVA and IVB HCC, surgery, chemotherapy, and radiotherapy were all independent protective factors in this study. The current guidelines do not recommend surgery for patients with stage IV HCC[29]. In previous study[30], surgery was found to be beneficial for patients with advanced HCC, particularly for those patients with regional lymph node invasions. However, considering the low proportion of patients undergoing surgery in this study, it is more reliable to strictly evaluate whether surgery is suitable for patients with stage IV HCC based on the specific clinical situation. Currently, for patients with stage IV HCC, the oral multi-kinase inhibitor sorafenib is the most accepted option globally, in 2 landmark studies[31-32] on sorafenib (the Asia-Pacific trial and the SHARP trial), the median OS was 6.5 and 10.7 months, respectively. Recently, some new findings of sorafenib in combination with other treatments have also yielded encouraging results, which promise to improve the treatment paradigms for patients with stage IV HCC[5, 33-34]. In addition, many studies[35-36] found that radiation therapy has been shown to be effective and safe for patients with inoperable stage IV HCC.

Nomogram models for predicting cancer patients, including those for predicting survival in HCC patients, have been widely established. At present, most existing constructed nomograms are used to predict survival in patients with full-stage[13-14] and early-stage HCC[15-18]. Yang, et al[17] constructed a prognostic nomogram model for the predicted 1-, 2-, and 3-year CSS of stage III and IV HCC patients based on the SEER database. As mentioned above, the median CSS and the IQR for the stage IVA HCC patients were 6.0 months and 3.0-17.0 months, respectively; IVB HCC patients were 4.0 months and 2.0-9.0 months, respectively. It is not appropriate to put stage III and IV HCC together, and the year-based nomogram may not fully reflect the poor prognosis of stage IV HCC. Zhang, et al[18] constructed 2 predictive nomograms for the predicted early death (<3 months) of patients with advanced HCC patients based on the SEER database, but the nomograms could not predict the CSS probability of patients who survived longer than 3 months. Considering the inadequacy of the studies of Yang, et al and Zhang, et al, we established month-based complete prognostic nomogram models for stage IV HCC patients. Furthermore, we develop 2 convenient and practical web predictive nomogram models, which were not mentioned in previous studies of advanced HCC. In this study, the AUCs showed that our nomograms had a good predictive ability, the calibration curves indicated an excellent consistency between the predictions and actual observations, and the DCA curves showed great clinical application prospects and good positive net benefit.

However, there are still several limitations in our study. First, as a retrospective analysis, selection bias was unavoidable. Second, the SEER database did not contain other potential prognostic factors for HCC, such as the etiology, HBsAg, and vascular invasion; in addition, immunotherapy has developed rapidly in the therapeutic field in recent years, but the SEER database does not contain this information. Third, although internal validation showed that our nomograms had outstanding utility, external validation with multiple centers including Chinese patients is needed to avoid overfitting.

In conclusion, through an analysis of the prognosis of stage IV HCC patients based on the SEER database, we developed and validated web prediction nomogram models for CSS of stage IVA and IVB HCC patients, which might be helpful for clinicians to predict the prognosis, implement individualized treatment, and follow up those patients.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation China (81872473).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

AUTHORS’CONTRIBUTIONS

ZHAN Gouling Data collection and interpretation, manuscript writing; CAO Peiguo and PENG Honghua Study design, paper supervision and revision. All authors have read and agreed to the final text.

Note

http://xbyxb.csu.edu.cn/xbwk/fileup/PDF/2023101546.pdf

References

- 1. Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, et al. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries[J]. CA Cancer J Clin, 2021, 71(3): 209-249. 10.3322/caac.21660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. McGlynn KA, Petrick JL, El-Serag HB. Epidemiology of hepatocellular carcinoma[J]. Hepatology, 2021, 73(Suppl 1): 4-13. 10.1002/hep.31288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Marrero JA, Kulik LM, Sirlin CB, et al. Diagnosis, staging, and management of hepatocellular carcinoma: 2018 Practice Guidance by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases[J]. Hepatology, 2018, 68(2): 723-750. 10.1002/hep.29913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Zhang K, Tao C, Wu F, et al. A practical nomogram from the SEER database to predict the prognosis of hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with lymph node metastasis[J]. Ann Palliat Med, 2021, 10(4): 3847-3863. 10.21037/apm-20-1876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bruix J, Reig M, Sherman M. Evidence-based diagnosis, staging, and treatment of patients with hepatocellular carcinoma[J]. Gastroenterology, 2016, 150(4): 835-853. 10.1053/j.gastro.2015.12.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Anwanwan D, Singh SK, Singh S, et al. Challenges in liver cancer and possible treatment approaches[J]. Biochim Biophys Acta Rev Cancer, 2020, 1873(1): 188314. 10.1016/j.bbcan.2019.188314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Llovet JM, Burroughs A, Bruix J. Hepatocellular carcinoma[J]. Lancet, 2003, 362(9399): 1907-1917. 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14964-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Roayaie S, Blume IN, Thung SN, et al. A system of classifying microvascular invasion to predict outcome after resection in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma[J]. Gastroenterology, 2009, 137(3): 850-855. 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Yamashita YI, Imai K, Yusa T, et al. Microvascular invasion of single small hepatocellular carcinoma ≤3 cm: Predictors and optimal treatments[J]. Ann Gastroenterol Surg, 2018, 2(3): 197-203. 10.1002/ags3.12057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Sung PS, Yang K, Bae SH, et al. Reduction of intrahepatic tumour by hepatic arterial infusion chemotherapy prolongs survival in hepatocellular carcinoma[J]. Anticancer Res, 2019, 39(7): 3909-3916. 10.21873/anticanres.13542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Nathan H, Hyder O, Mayo SC, et al. Surgical therapy for early hepatocellular carcinoma in the modern era: a 10-year SEER-medicare analysis[J]. Ann Surg, 2013, 258(6): 1022-1027. 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31827da749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Pan YX, Xi M, Fu YZ, et al. Stereotactic body radiotherapy as a salvage therapy after incomplete radiofrequency ablation for hepatocellular carcinoma: A retrospective propensity score matching study[J]. Cancers (Basel), 2019, 11(8): 1116. 10.3390/cancers11081116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Chen R, Hou B, Qiu S, et al. Development and validation of nomogram for predicting survival of primary liver cancers using machine learning[J]. Front Oncol, 2022, 12: 926359. 10.3389/fonc.2022.926359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Xiao Z, Yan Y, Zhou Q, et al. Development and external validation of prognostic nomograms in hepatocellular carcinoma patients: a population based study[J]. Cancer Manag Res, 2019, 11: 2691-2708. 10.2147/CMAR.S191287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. He T, Chen T, Liu X, et al. A web-based prediction model for cancer-specific survival of elderly patients with early hepatocellular carcinoma: A study based on SEER database[J]. Front Public Health, 2021, 9: 789026. 10.3389/fpubh.2021.789026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Wen C, Tang J, Luo H. Development and validation of a nomogram to predict cancer-specific survival for middle-aged patients with early-stage hepatocellular carcinoma[J]. Front Public Health, 2022, 10: 848716. 10.3389/fpubh.2022.848716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Yang D, Su Y, Zhao F, et al. A practical nomogram and risk stratification system predicting the cancer-specific survival for patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma[J]. Front Oncol, 2022, 12: 914192. 10.3389/fonc.2022.914192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Zhang H, Du X, Dong H, et al. Risk factors and predictive nomograms for early death of patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: a large retrospective study based on the SEER database[J]. BMC Gastroenterol, 2022, 22(1): 348. 10.1186/s12876-022-02424-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Orcutt ST, Anaya DA. Liver resection and surgical strategies for management of primary liver cancer[J]. Cancer Control, 2018, 25(1): 1145179885. 10.1177/1073274817744621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. European Association for the Study of the Liver; European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer . EASL-EORTC clinical practice guidelines: management of hepatocellular carcinoma[J]. J Hepatol, 2012, 56(4): 908-943. 10.1016/j.jhep.2011.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Yan B, Su BB, Bai DS, et al. A practical nomogram and risk stratification system predicting the cancer-specific survival for patients with early hepatocellular carcinoma[J]. Cancer Med, 2021, 10(2): 496-506. 10.1002/cam4.3613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Liu K, Huang G, Chang P, et al. Construction and validation of a nomogram for predicting cancer-specific survival in hepatocellular carcinoma patients[J]. Sci Rep, 2020, 10(1): 21376. 10.1038/s41598-020-78545-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Chen SH, Wan QS, Zhou D, et al. A simple-to-use nomogram for predicting the survival of early hepatocellular carcinoma patients[J]. Front Oncol, 2019, 9: 584. 10.3389/fonc.2019.00584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. El-Serag HB, Mason AC, Key C. Trends in survival of patients with hepatocellular carcinoma between 1977 and 1996 in the United States[J]. Hepatology, 2001, 33(1): 62-65. 10.1053/jhep.2001.21041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Huang Z, Gu Y, Zhang T, et al. Nomograms to predict survival outcomes after microwave ablation in elderly patients (>65 years old) with early-stage hepatocellular carcinoma[J]. Int J Hyperthermia, 2020, 37(1): 808-818. 10.1080/02656736.2020.1785556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Wan S, Nie Y, Zhu X. Development of a prognostic scoring model for predicting the survival of elderly patients with hepatocellular carcinoma[J/OL]. PeerJ, 2020, 8: e8497[2022-11-30]. 10.7717/peerj.8497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Asrani SK, Devarbhavi H, Eaton J, et al. Burden of liver diseases in the world[J]. J Hepatol, 2019, 70(1): 151-171. 10.1016/j.jhep.2018.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Liu H, Cen D, Yu Y, et al. Does fibrosis have an impact on survival of patients with hepatocellular carcinoma: evidence from the SEER database?[J]. BMC Cancer, 2018, 18(1): 1125. 10.1186/s12885-018-4996-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. European Association for the Study of the Liver . EASL clinical practice guidelines: Management of hepatocellular carcinoma[J]. J Hepatol, 2018, 69(1): 182-236. 10.1016/j.jhep.2018.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Chen L, Sun T, Chen S, et al. The efficacy of surgery in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: a cohort study[J]. World J Surg Oncol, 2020, 18(1): 119. 10.1186/s12957-020-01887-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Cheng AL, Kang YK, Chen Z, et al. Efficacy and safety of sorafenib in patients in the Asia-Pacific region with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: a phase III randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial[J]. Lancet Oncol, 2009, 10(1): 25-34. 10.1016/S1470-2045(08)70285-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Llovet JM, Ricci S, Mazzaferro V, et al. Sorafenib in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma[J]. N Engl J Med, 2008, 359(4): 378-390. 10.1056/NEJMoa0708857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Yau T, Park JW, Finn RS, et al. Nivolumab versus sorafenib in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma (CheckMate 459): a randomised, multicentre, open-label, phase 3 trial[J]. Lancet Oncol, 2022, 23(1): 77-90. 10.1016/S1470-2045(21)00604-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Vogel A, Qin S, Kudo M, et al. Lenvatinib versus sorafenib for first-line treatment of unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma: patient-reported outcomes from a randomised, open-label, non-inferiority, phase 3 trial[J]. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol, 2021, 6(8): 649-658. 10.1016/S2468-1253(21)00110-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Llovet JM, Kelley RK, Villanueva A, et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma[J]. Nat Rev Dis Primers, 2021, 7(1): 6. 10.1038/s41572-020-00240-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Cho JY, Paik YH, Park HC, et al. The feasibility of combined transcatheter arterial chemoembolization and radiotherapy for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma[J]. Liver Int, 2014, 34(5): 795-801. 10.1111/liv.12445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]