Abstract

Objective

To control the pandemic of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) effectively, strict isolation measures have been taken in China. Suspected patients must be isolated, and the confirmed patients specifically are isolated in negative-pressure isolation rooms. During the isolation, patients face difficulty in adapting to their surrounding environment, worry about the prognosis of the disease, lack confidence in treatment, separate from their families, and have a sense of distance from medical staff. Isolated patients may possess the feelings of negativity, including loneliness, anxiety, depression, insomnia, and despair. Hence, to reduce the risk of adverse psychological outcomes, “family member-like” care strategies were developed and implemented to solve problems associated with the COVID-19 pandemic. This study aims to examine whether using “family member-like” care strategies can improve psychological resilience and reduce depression, anxiety, and stress symptoms among patients with COVID-19 in an isolation ward.

Methods

A quasi-experimental design was used to evaluate the “family member-like” care strategies for adult patients with COVID-19 in an isolation ward. COVID-19 patients in the Xiangya ward of the West District of the Union Hospital of Tongji Medical College of Huazhong University of Science and Technology in Wuhan, Hubei province, were included in this study from February 9 to March 20, 2020. Healthcare providers who volunteered as family members were assigned to patients. They practiced one-to-one care and provided continuous and whole care for the patients who were from admission to discharge. Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale-10 (CD-RISC-10) and Depression Anxiety Stress Scale-21 (DASS-21) were used to evaluate the resilience and psychological status of COVID-19 inpatients upon hospital admission, 2 weeks after admission, and at their discharge from the hospital.

Results

The questionnaire response rate of the “family member-like” strategies was 100%. Of the 60 patients, 39 (65.0%) were male, and 21 (35%) were female. The hospital stay was (27.5±3.5) days. All the 60 patients were cured and discharged without any death and serious complications. The total scores for CD-RISC were 8.83±6.86 at admission, 29.13±5.42 at 2 weeks after admission, and 33.87±6.14 at discharge, which were significantly improved at the 2 follow-ups (F=404.564, P<0.001). Multivariate analysis and repeated measurements also indicated that patients experienced significant improvements in tenacity (F=360.839, P<0.001), strength (F=368.217, P<0.001), and optimism (F=328.456, P<0.001) at the 2 follow-ups. The total scores of DASS-21 were 49.27±11.30 at admission, 30.77±16.71 at 2 weeks after admission, and 4.17±11.03 at discharge, and the scores were significantly decreased at the 2 follow-ups (F=270.536, P<0.001). Multivariate analysis and repeated measurements also indicated that patients experienced significant decreases in depression (F=211.938, P<0.001), anxiety (F=285.592, P<0.001), and stress (F=287.478, P<0.001) at the 2 follow-ups.

Conclusion

“Family member-like” strategies had positive effects on improving psychological resilience and reducing the symptoms of anxiety and depression of COVID-19 patients. It might be an effective care method for COVID-19 patients. It should be incorporated into emergency care management to improve care quality during public health emergencies of infectious diseases.

Keywords: “family member-like” care strategies, resilience, depression, anxiety, stress, adult patients, coronavirus disease 2019

Abstract

目的

2019冠状病毒病(coronavirus disease 2019,COVID-19)暴发后,为了有效控制疫情,中国采取了严格的隔离措施,确诊患者需收治在负压隔离病房,疑似患者必须隔离。在隔离期间,患者不仅面临多种困难,如适应环境、担心疾病的预后、对治疗缺乏信心等,还经历着与家人分离、与医务人员有距离感的痛苦,这些问题都可能导致患者产生孤独、焦虑、抑郁、失眠和绝望等一系列心理不适。因此,为了减少患者的负面情绪,“家属”照护策略应运而生。本研究旨在探讨“家属”照护策略能否提高隔离病房患者的心理弹性,改善其抑郁、焦虑、压力症状。

方法

采用类实验设计评价对隔离病房成人COVID-19患者实施的“家属”照护策略的效果。2020年2月9日至3月20日期间在华中科技大学同济医学院武汉协和医院西院区湘雅病房住院的COVID-19患者被纳入本研究。医疗服务提供者自愿成为患者的家属,从患者入院到出院为其提供一对一、全程的家属式的照护。采用Connor-Davidson心理弹性量表简化版(CD-RISC-10)和抑郁-焦虑-压力量表中文版(DASS-21)对患者入院时、入院2周后和出院时的心理弹性和抑郁、焦虑、压力情况进行评估。

结果

此问卷的应答率为100%。在60名患者中,39名(65.0%)为男性,21名(35%)为女性,住院时间为(27.5±3.5) d。60例患者均痊愈出院,无1例死亡和发生严重的并发症。CD-RISC-10总分入院时为8.83±6.86,入院后2周为29.13±5.42,出院时为33.87±6.14,后2次评分较入院时均明显增加 (F=404.564,P<0.001);多变量重复测量方差分析表明患者在韧性(F=360.839,P<0.001)、力量(F=368.217,P<0.001)和乐观(F=328.456,P<0.001)方面的评分有显著提高。入院时DASS-21总分为49.27±11.30,入院后2周为30.77±16.71,出院时为4.17±11.03,后2次评分较入院时均明显下降(F=270.536,P<0.001);多变量重复测量方差分析表明患者在抑郁(F=211.938,P<0.001)、焦虑(F=285.592,P<0.001)和压力(F=287.478,P<0.001)方面的评分有显著下降。

结论

“家属”照护策略提升了COVID-19患者的心理弹性,改善了其抑郁、焦虑、压力症状,是一种针对COVID-19患者的有效管理方法。在传染病等突发公共卫生事件中,“家属”照护策略应该被纳入急救管理的措施中,以此来提高患者照护质量。

Keywords: “家属”照护策略, 心理弹性, 抑郁, 焦虑, 压力, 成人患者, 2019冠状病毒病

http://xbyxb.csu.edu.cn/xbwk/fileup/PDF/202107736.pdf

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) has become a major outbreak in the world[1] . The exact origin of COVID-19 and the appropriate antiviral treatments remain unknown[2-3]. To control the pandemic effectively, strict isolation control measures have been adopted in China. Suspected and confirmed patients must be isolated, and confirmed patients specifically are isolated in negative-pressure isolation rooms[3]. During the isolation period, patients not only face difficulty in adapting to their surrounding environment, but also worry about the prognosis of the disease, which may cause a series of psychological or psychiatric adverse reactions among them[4]. Isolated patients may become mired in feelings of negativity, including loneliness, denial, anxiety, depression, insomnia, and despair, due to factors such as the lack of knowledge of the disease, lack of confidence in their treatment, separation from their families, and a sense of distance from the medical staff[4-5]. According to our previous large cross-sectional online survey which was performed in Hubei Province for about 3 000 participants, and outside Hubei Province for 3 000 participants[6], we found that people who were infected COVID-19 had a much higher prevalence of depression and anxiety. Urgent psychological assistance and support were needed because of their fear of severe disease consequences and contagion[7], as well as their passive emotional experiences, which may reduce their treatment adherence. Some patients may even have an increased risk of aggression[8]. Hence, to reduce the risk of negative psychological outcomes, implementing psychological assistance and support for COVID-19 patients is imperative.

During the isolation period, healthcare providers play an important role in terms of making direct contact with patients and providing them with long-term care. They can help patients properly understand the progression of the disease and can provide essential psychological assistance to patients. They also create an atmosphere of humane care in their wards and implement cooperative care strategies for patients. Thus, healthcare providers are the most appropriate individuals to provide effective psychological aid to COVID-19 patients. Family support from an interprofessional intensive care unit (ICU) team can reduce the length of ICU patient stays in hospitals[9]. Therefore, “family member-like” care strategies were developed and implemented to solve problems associated with the current COVID-19 pandemic. A medical team was dispatched to the West Union Hospital of Wuhan on February 7, 2020 to manage one ward. Every healthcare provider on the team who volunteered as a “family member” adopted one patient, and they provided one-to-one, continuous, and whole-process care, as well as psychological aid for their corresponding patient from admission to discharge. This study aims to examine the effects of these “family member-like” care strategies, and its findings are summarized. The managerial strategies investigated here can help inform patient care in the global fight against the COVID-19 pandemic.

1. Subjects and methods

1.1. Research design

A quasi-experimental design was used to evaluate “family member-like” care strategies for adult patients with COVID-19 in an isolation ward. Scores of psychological resilience, depression, anxiety, and stress were compared.

1.2. Setting and participants

This study was conducted with COVID-19 patients from February 9 to March 20, 2020 in the Xiangya ward of the West District of the Union Hospital of Tongji Medical College of Huazhong University of Science and Technology in Wuhan, Hubei Province. The ward was responsible for treating adult COVID-19 patients in ordinary, severe, and critical cases, according to clinical classifications developed during the pandemic[10].

To be eligible for participation, COVID-19 patients had to fulfill the following criteria: 1) aged ≥18 years; 2) diagnosed with ordinary or severe cases according to clinical classification[10]; 3) conscious and able to communicate; 4) willing to participate in this study. The study’s exclusion criteria included the following: 1) diagnosed with a critical case according to clinical classification; 2) severe deterioration to a critical level during hospitalization; 3) communication difficulty for any reason.

1.3. Optimizing care strategies

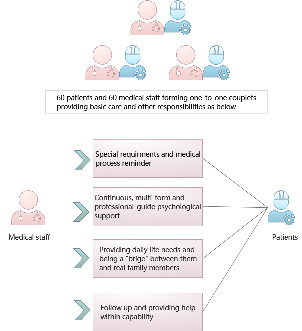

In our study, healthcare providers who volunteered as family members were assigned to patients: they practiced one-to-one care during their shifts and provided continuous and whole care for the patients that they were coupled with from admission to discharge. Family members had the following responsibilities as depicted in Figure 1.

Figure 1. “Family member-like” care strategies.

1) Each patient’s family member placed a reminder, such as a paper note, at the head of patients’ beds featuring the patient’s medication information, special treatment (e.g., atomization treatment, blood pressure monitoring, and blood glucose monitoring), diet, and special requirements. The family member regularly checked whether the required work was performed or not and reported to the doctor in charge.

2) The family members provided continuous psychological support. They assessed patients’ psychological status while at work and online after work. By providing psychological counseling to patients, they helped patients build confidence. By playing patients soothing music via WeChat, they provided psychological support and encouragement under the supervision of psychologists.

3) These healthcare providers were also familiar with patients’ family status and took the initiative to confirm whether patients needed help in daily life activities. Moreover, family members worked with patients to bridge any communication gaps, especially with elderly patients who did not have smartphones. They tried to get in touch with patients’ loved ones and even showed video records on their behalf to soothe patients’ anxiety.

4) Healthcare providers continued to follow up with their patients after they were discharged by aiding within their capacity.

1.4. Data collection

Study data were collected via a self-reported questionnaire. If patients had reading and writing difficulties, the data collectors read the questionnaire items for them and recorded their responses. Baseline data [i.e., results on the Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale-10 (CD-RISC-10)[11], Depression Anxiety Stress Scale-21 (DASS-21)[12]], and sociodemographic information, were collected upon patients’ admission. Follow-up data (i.e., CD-RISC-10 and DASS-21 scores) were collected 2 weeks after patients’ admission and at their discharge.

A simplified 10-item version of the CD-RISC-10 was used to evaluate patients’ ability to return to a normal state when encountering dilemmas or challenges[11]. This scale has demonstrated excellent internal consistency in evaluating Chinese earthquake victims (Cronbach’s alpha=0.91) and test-retest reliability (with an interval of 2 weeks; r=0.90)[13]. For this assessment, a five-point Likert scale was employed, where 0 meant not true at all, 1 meant rarely true, 2 meant sometimes true, 3 meant often true, and 4 meant true nearly all the time. As a sum of all the items’ points, patients’ total scores ranged from 0 to 40 points. A higher total score denoted a higher level of resilience.

The simplified DASS-21 was also employed[12]. The DASS-21 comprised 3 dimensions: depression, anxiety, and stress. Each dimension contained 7 items, which were used to evaluate subjects’ emotions over one week, prior to their completing the questionnaire. For this assessment, the items were rated on a four-point Likert scale (i.e., 1=none, 2=sometimes, 3=often, and 4=always). Each scale had a total score of 0-21. A higher score denoted a greater severity of negative emotions. Patients’ scores on the depression, anxiety, and stress scales were classified as normal, mild, moderate, severe, or extremely severe. This scale has demonstrated suitable psychometric properties in assessing Chinese college students, with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.89, and the Cronbach’s alpha for depression, anxiety, and stress scales being 0.83, 0.80, and 0.82, respectively[14].

1.5. Ethical considerations

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (World Medical Association, 2013) and was approved by the institutional ethical review committee of the Xiangya Hospital (No. 202002023). Patients were informed about the purpose and procedure of the study, and they were notified of their right to withdraw at any time, as well as their right to refrain from answering any question. Before the study began, written informed consent was obtained from all the patients after ensuring that they completely understood the study’s procedures.

1.6. Statistic analysis

The study’s primary outcome included a CD-RISC score change from the admission (Phase 1) to 2 weeks after patients’ admission (Phase 2) and at their discharge from the hospital (Phase 3). The secondary outcomes were DASS score changes at the 3 phases. Multivariate analysis and repeated measurements were used to evaluate and compare the dimensions and total CD-RISC and DASS-21 scores. Estimated within-group differences were reported with 95% confidence intervals. The acceptable significance was set at P< 0.05. All data analyses were performed using SPSS 25.0.

2. Results

2.1. Sociodemographic statistics

The questionnaire response rate of our “family member-like” strategies was 100%. Of the 60 patients, 39 (65.0%) were male and 21 (35%) were female. Furthermore, 14 (23.3%) were ≤50 years old, 28 (46.7%) were 51-64 years old, and 18 (30%) were ≥65 years old. Eleven (18.3%) had severe pneumonia and 49 (81.7%) had moderate pneumonia (Table 1). In our study, the hospital stay was (27.5±3.5) days. All the 60 patients were cured and discharged without any death and any serious complications.

Table 1.

Demographic data and characteristics of the patients (n=60)

| Variables | Category | Frequency | Constituent ratio/% |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 39 | 65.0 |

| Female | 21 | 35.0 | |

| Age/years | ≤50 | 14 | 23.3 |

| 51-64 | 28 | 46.7 | |

| ≥65 | 18 | 30.0 | |

| Education level | Primary school | 21 | 35.0 |

| Junior high school diploma | 22 | 36.7 | |

| High school degree and secondary technical school degree | 17 | 28.3 | |

| Marital status | Single | 2 | 3.3 |

| Married | 58 | 96.7 | |

| Number of children | ≥1 | 57 | 95.0 |

| 0 | 3 | 5.0 | |

| Occupation | Retiree | 27 | 45.0 |

|

Commercial, service, agriculture, forestry, animal husbandry, sideline, and fishery production personnel |

15 | 25.0 | |

| Personnel of enterprises and institutions | 14 | 23.3 | |

| Medical staff | 4 | 6.7 | |

| Whether an only child or not | Yes | 5 | 8.3 |

| No | 55 | 91.7 | |

| Grades of pneumonia | Severe | 11 | 18.3 |

| Moderate | 49 | 81.7 |

2.2. “Family member-like” strategies improved the resilience of COVID-19 patients

The total scores for CD-RISC were 8.83±6.86 at admission, 29.13±5.42 at 2 weeks after admission (at which time the severity of pneumonia remained unchanged), and 33.87±6.14 at discharge, which significantly improved at the 2 follow-ups (F=404.564, P<0.001). Multivariate analysis and repeated measurements also indicated that patients experienced significant improvements in tenacity (F=360.839, P<0.001), strength (F=368.217, P<0.001), and optimism (F=328.456, P<0.001) at the 2 follow-ups (Table 2).

Table 2.

Total and subdimension scores of CD-RISC at 3 time points ( ±s)

| Item | Admission | Two weeks after admission | Discharge | F | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tenacity | 4.62±3.57 | 14.60±2.88 | 17.42±3.13 | 360.839 | <0.001 |

| Strength | 2.33±1.98 | 8.65±1.67 | 9.72±2.03 | 368.217 | <0.001 |

| Optimism | 1.88±1.55 | 5.88±1.47 | 6.73±1.22 | 328.456 | <0.001 |

| Total | 8.83±6.86 | 29.13±5.42 | 33.87±6.14 | 404.564 | <0.001 |

2.3. “Family member-like” strategies improved depression, anxiety, and stress of COVID-19 patients

The total scores of DASS-21 were 49.27±11.30 at admission, 30.77±16.71 at 2 weeks after admission, and 4.17±11.03 at discharge, and scores significantly decreased at the 2 follow-ups (F=270.536, P<0.001). Multivariate analysis and repeated measurements also indicated that patients experienced significant decreases in depression (F=211.938, P<0.001), anxiety (F=285.592, P<0.001), and stress (F=287.478, P<0.001) at the 2 follow-ups (Table 3).

Table 3.

Total and subdimension scores of DASS-21 at 3 time points ( ±s)

| Item | Admission | Two weeks after admission | Discharge | F | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Depression | 16.18±4.55 | 9.62±6.04 | 1.10±3.83 | 211.938 | <0.001 |

| Anxiety | 15.65±3.80 | 9.67±5.25 | 0.92±3.35 | 285.592 | <0.001 |

| Stress | 17.43±3.22 | 11.28±5.94 | 2.15±4.05 | 287.478 | <0.001 |

| Total | 49.27±11.30 | 30.77±16.71 | 4.17±11.03 | 270.536 | <0.001 |

3. Discussion

COVID-19 leads to psychological disorders among the general population[15]. Previous study[16] found the incidence of anxiety and depression in isolated individuals without psychological support increased significantly. Hence, to improve resilience for the hospitalization of COVID-19 patients, “family member-like” strategies should be developed and implemented. With the stress of the disease itself and isolation from family members, the psychological problems of COVID-19 patients tended to be more serious than those of the general population[17]. In our study, we implemented “family member-like” care strategies, aiming to examine their effects on COVID-19 patients during the pandemic.

We found that significant improvements in participating patients’ mean resilience total score after 2 weeks of admission and at discharge compared to their baseline scores. This finding indicated “family member-like” care strategies had the effects to promote psychological recovery for the COVID-19 patients. Resilience is a protective factor that helps individuals to recover from negative experiences, especially major traumas, dilemmas, setbacks, difficulties, and stressful or even life-threatening situations[18]. The new strategies provided companionship and emotional support to both patients and healthcare providers, producing an overall positive influence. This research showed that patient-healthcare provider couplets are effective at improving resilience and mental well-being based on family-type emotional support and functions. Such an approach means that healthcare providers can offer encouragement, comfort, companionship, attention, and concern while acting more as family members than as healthcare providers. These strategies enable healthcare providers to obtain information from patients dynamically. They can also help healthcare providers to deal with existing or new problems more easily and improve patients’ psychological resilience.

Moreover, this study’s findings demonstrated that DASS scores for depression, stress, and anxiety also reduced significantly compared to patients’ baseline scores. These results could be explained by the fact that patients who were matched with healthcare providers may not only have received treatment and quality care during their designated family members’ shift but also have contacted and communicated with these members by using smartphones after the official shifts. As a result, minor psychological problems could be detected and managed at early stages. Furthermore, patients gained family support and psychological aid from the strategies. Hence, they may have relieved their negative emotions. With a more accessible and convenient care process, these strategies strengthen interventions, as well as follow-up continuity and completeness.

The implementations of the strategies in a quarantine ward not only resolved the shortage of psychological practitioner resources but also helped healthcare providers and patients. Therefore, they represented economic and feasible solutions for inpatient psychological care during the current COVID-19 outbreak. The psychological interference of this strategies is more economical than professional psychological counseling. “Family member-like” care strategies can also provide a reference for countries seeking to improve their medical human resources. Obviously, “family member-like” care strategies are two-way strategies. The strategies are also beneficial to healthcare providers because the current pandemic healthcare providers are also isolated and without access to their real-life family members. Therefore, the healthcare providers may also require psychological support. Based on these considerations, implementation of the proposed strategies would meet the practical requirements.

Our study included a few limitations. First, this research used a quasi-experimental study method. Because of the self-contrast design, the research objects were not compared to a randomized control group. Second, the data from the self-rating scale and questionnaire may be subjective. Third, this research was based on a highly special situation (i.e., the COVID-19 pandemic), and social circumstances and national conditions may have also influenced the strategies’ effects. The effectiveness of these strategies in a wider set or range of circumstances should be confirmed through further study.

Thus, researchers should consider randomized trials in future studies to provide more reliable evidence. Obviously, “family member-like” care strategies are two-way strategies, and healthcare providers’ psychological state should also be assessed in future implementations. Healthcare providers’ perception of the strategies can then be explored as a possible factor influencing the strategies’ effectiveness.

The findings of this research support “family member-like” strategies as an effective care management method for COVID-19 patients. The strategies improved COVID-19 patients’ psychological resilience and promoted psychological recovery effectively, while optimizing their experience during the hospital stay. “Family member-like” care strategies are optimal and innovative. Ideally, they should be incorporated into emergency care management in order to improve care quality during public health emergency of infectious diseases.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by the Scientific Research Project from Hunan Provincial Health Commission, China (20200815).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Note

http://xbyxb.csu.edu.cn/xbwk/fileup/PDF/202107736.pdf

References

- 1. Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China[J]. Lancet, 2020, 395(10223): 497-506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Tu H, Tu S, Gao S, et al. Current epidemiological and clinical features of COVID-19; a global perspective from China[J]. J Infect, 2020, 81(1): 1-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Pascarella G, Strumia A, Piliego C, et al. COVID-19 diagnosis and management: a comprehensive review[J]. J Intern Med, 2020, 288(2): 192-206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. 何丁玲, 赵霞, 万彬, 等. 新型冠状病毒肺炎隔离病房患者的心理反应及护理对策[J]. 现代临床医学, 2020, 46(4): 288-289. [Google Scholar]; HE Dingling, ZHAO Xia, WAN Bin, et al. Psychological response and nursing countermeasures of patients in COVID-19 isolation ward[J]. Journal of Modern Clinical Medicine, 2020, 4(46): 288-289. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Cheng SK, Wong CW, Tsang J, et al. Psychological distress and negative appraisals in survivors of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS)[J]. Psychol Med, 2004, 34(7): 1187-1195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Huang J, Liu F, Teng Z, et al. Public behavior change, perceptions, depression, and anxiety in relation to the COVID-19 outbreak[J]. Open Forum Infect Dis, 2020, 7(8): ofaa273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Xiang YT, Yang Y, Li W, et al. Timely mental health care for the 2019 novel coronavirus outbreak is urgently needed[J]. Lancet Psychiatry, 2020, 7(3): 228-229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Li W, Yang Y, Liu ZH, et al. Progression of mental health services during the COVID-19 outbreak in China[J]. Int J Biol Sci, 2020, 16(10): 1732-1738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. White DB, Angus DC, Shields AM, et al. A Randomized trial of a family-support intervention in Intensive Care Units[J]. N Engl J Med, 2018, 378(25): 2365-2375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. 林铃, 李太生. 《国家卫生健康委员会新型冠状病毒肺炎诊疗指南(试行第五版)》解读[J]. 中华医学杂志, 2020, 100(11): 805-807. [Google Scholar]; LIN Ling, LI Taisheng. Interpretation of “Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV) Infection by the National Health Commission (Trial Version 5)”[J]. Zhonghua Yi Xue Za Zhi, 2020, 100(11): 805-807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Connor KM, Davidson JR. Development of a new resilience scale: the Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC)[J]. Depress Anxiety, 2003, 18(2): 76-82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lovibond PF, Lovibond SH. The structure of negative emotional states: comparison of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS) with the Beck Depression and Anxiety Inventories[J]. Behav Res Ther, 1995, 33(3): 335-43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Wang L, Shi Z, Zhang Y, et al. Psychometric properties of the 10-item Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale in Chinese earthquake victims[J]. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci, 2010, 64(5): 499-504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Wang K, Shi HS, Geng FL, et al. Cross-cultural validation of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scale-21 in China[J]. Psychol Assess, 2016, 28(5): e88-e100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Salari N, Hosseinian-Far A, Jalali R, et al. Prevalence of stress, anxiety, depression among the general population during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review and meta-analysis[J]. Global Health, 2020, 16(1): 57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Lei L, Huang X, Zhang S, et al. Comparison of prevalence and associated factors of anxiety and depression among people affected by versus people unaffected by quarantine during the COVID-19 epidemic in Southwestern China[J]. Med Sci Monit, 2020, 26: e924609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Wang S, Zhang Y, Ding W, et al. Psychological distress and sleep problems when people are under interpersonal isolation during an epidemic: A nationwide multicenter cross-sectional study[J]. Eur Psychiatry, 2020, 63(1): e77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Bonanno GA. Loss, trauma, and human resilience: have we underestimated the human capacity to thrive after extremely aversive events?[J]. Am Psychol, 2004, 59(1): 20-28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]