Abstract

目的

随着微创外科技术的发展,达芬奇机器人技术的应用越来越广泛。本研究通过分析机器人辅助胃切除术(robotic-assisted gastrectomy,RAG)与腹腔镜辅助胃切除术(laparoscopic-assisted gastrectomy,LAG)2种不同外科技术初期阶段学习曲线的比较,探讨先进手术机器人技术对外科手术学习曲线的可能影响。

方法

选取在2017年9月至2020年12月一名主刀医师从初始阶段开始实施RAG或LAG手术的远端胃癌根治术的108例患者,分为行达芬奇Si机器人系统RAG的RAG组(n=27)和行LAG的LAG组(n=81),胃癌区域淋巴结分组参照日本胃癌治疗指南实施,分析其围手术期结果、术后并发症、术后肿瘤学结果和外科手术学习曲线等相关情况。

结果

2组患者在一般资料、肿瘤大小、组织学分级和临床分期上的差异均无统计学意义(均P>0.05);RAG组术后严重并发症的发生率低于LAG组(P=0.003);RAG组术中的失血量低于LAG组的失血量(P=0.046);RAG组清扫淋巴结数量更多(P=0.003),其中在第9组(P=0.038)和11p组(P=0.015)淋巴结清扫中表现出明显优势;RAG组手术时间明显比LAG组长(P=0.015);学习曲线分析发现,RAG组的累积和分析(cumulative sum analysis,CUSUM)值从第10例开始下降,而LAG组的CUSUM值从第28例开始下降,RAG的学习曲线比LAG的学习曲线具有更少的截止案例。手术机器人的独特设计可能有助于提高手术效率和缩短外科手术学习曲线。

结论

先进机器人技术有助于经验丰富的外科医生快速学习掌握RAG技能,超越机器人学习曲线达到熟练阶段需要的最少手术例数为10例,并在第9组和11p组淋巴结清扫和减轻手术创伤方面优于LAG。RAG手术比LAG手术能清扫出更多的淋巴结,有更好的围手术期疗效。

Keywords: 达芬奇机器人系统, 机器人辅助下胃切除术, D2淋巴结清扫, 胃癌

Abstract

Objective

Da Vinci robot technology is widely used in clinic,with minimally invasive surgery development. This study aims to explore the possible influence of advanced surgical robotics on the surgery learning curve by comparing the initial clinical learning curves of 2 different surgical techniques: robotic-assisted gastrectomy (RAG) and laparoscopic-assisted gastrectomy (LAG).

Methods

From September 2017 to December 2020, a chief surgeon completed a total of 108 cases of radical gastric cancer from the initial stage, including 27 cases of RAG of the Da Vinci Si robotic system (RAG group) and 81 cases of LAG (LAG group). The lymph node of gastric cancer implemented by the Japanese treatment guidelines of gastric cancer. The surgical results, postoperative complications, oncology results and learning curve were analyzed.

Results

There was no significant difference in general data, tumor size, pathological grade and clinical stage between the 2 groups (P>0.05). The incidence of serious complications in the RAG group was lower than the LAG group (P=0.003). The intraoperative blood loss in the RAG group was lower than that in the LAG group (P=0.046). The number of lymph nodes cleaned in the RAG group was more (P=0.003), among which there was obvious advantage in lymph node cleaning in the No.9 group (P=0.038) and 11p group (P=0.015). The operation time of the RAG group was significantly longer than the LAG group (P=0.015). The analysis of learning curve found that the cumulative sum analysis (CUSUM) value of the RAG group decreased from the 10th case, while the CUSUM of the LAG group decreased from the 28th case. The learning curve of the RAG group had fewer closing cases than that of the LAG group. The unique design of the surgical robot might help to improve the surgical efficiency and shorten the surgical learning curve.

Conclusion

Advanced robotics helps experienced surgeons quickly learn to master RAG skills. With the help of robotics, RAG are superior to LAG in No.9 and 11p lymph node dissection and surgical trauma reduction. RAG can clear more lymph nodes than LAG, and has better perioperative effect.

Keywords: Da Vinci surgical robot system, robot-assisted gastrectomy, lymph adenectomy (D2), gastric cancer

胃癌在中国存在发病率高、预后相对较差的临床特点,根治性切除加D2淋巴结清扫术是胃癌手术治疗的主要方法。由于开放手术存在术后疼痛和住院时间延长等缺点,外科医生更加重视微创手术(minimally invasive surgery,MIS)。目前,腹腔镜胃癌手术技术的疗效已得到了充分验证[1-2]。然而,腹腔镜手术仍存在一些技术局限,例如二维手术视野和主刀医师手部动作等。达芬奇机器人系统作为先进手术机器人技术的代表,与腹腔镜相比,具有三维(three dimensional,3D)放大的可视化效果、良好的人体工程学结构和精细解剖等技术优势,有利于D2淋巴结清扫[3-6]。研究[7-10]表明机器人辅助胃切除术(robotic-assisted gastrectomy,RAG)可以作为胃癌患者的可靠选择,其临床疗效与腹腔镜辅助胃切除术(laparoscopic-assisted gastrectomy,LAG)相当。随着达芬奇机器人技术在中国临床应用的发展,目前已有较多研究探讨了RAG的临床疗效。然而,较少有研究关注机器人技术优势对于主刀医师的手术技能学习曲线的影响。本研究通过分析RAG和LAG学习曲线的临床疗效差异,比较RAG与LAG学习曲线变化趋势,探讨机器人技术与腹腔镜技术对胃癌根治术学习曲线的影响。

1. 资料与方法

1.1. 一般资料

选取2017年9月至2020年12月在中南大学湘雅三医院(以下简称“我院”)完成胃癌根治术的108例患者,分为行达芬奇Si机器人系统RAG的RAG组 (n=27)和行LAG的LAG组(n=81),其中RAG组男性患者16例,女性患者11例,LAG组男性患者50例,女性患者31例。所有手术均由同一名主刀医师完成。临床病理资料和术后病理分期根据日本胃癌临床诊疗指南[11]进行记录。胃癌区域淋巴结分组情况参照日本胃癌治疗指南实施[12]。所有患者术前均详细告知RAG和LAG的优缺点,自主选择手术方式,并签署手术知情同意书。所有患者数据均在我院机器人外科数据库中注册(包含Da Vinci RAG、LAG和开腹手术数据库)。所有RAG病例的主要手术步骤和D2淋巴结清扫等均使用Da Vinci Si手术系统(Intuitive Surgical Inc,Sunnyvale,CA)。无化学治疗(以下简称“化疗”)禁忌证的患者均于术后第4周或第5周进行首次辅助化疗。所有纳入研究的患者都随访12个月。本研究在“Clinicaltrials.gov”注册(ID:NCT02752698),并获得人类研究保护计划认证协会(Association for The Accreditation of Hunan Research Protection Program,AAHRPP)审核批准(项目编号:T16005,2016年2月)。

1.2. 纳入标准

1)内窥镜活检证实为原发性远端胃癌(肿瘤分期为T1、T2和T3,不累及其他器官或血管);2)年龄在18至75岁;3)美国麻醉学会(American Society of Anesthesiogists,ASA)分级 3;4)无术前治疗;5)实施了LAG或RAG手术。

1.3. 排除标准

1)急诊手术;2)同时或异时多处原发肿瘤;3)肿瘤远处转移;4)肿瘤广泛侵犯邻近器官;5)存在严重心肺功能损害。

1.4. 观察指标

手术时间(operative time,OT)、失血量(blood loss,BL)、综合并发症指数(charlson comorbidity index,CCI)、清扫淋巴结数目、手术切缘情况,中转开腹情况、相关并发症情况、术后30 d病死率和术后恢复参数(包括第一次排气时间、饮食时间和手术后住院时间)。

1.5. CUSUM及拟合方程

采用累积和分析(cumulative sum analysis,CUSUM)评估LAG或RAG的学习曲线。选择5个指标对学习曲线进行评价:OT、预估的BL、清扫的第9组和11p组淋巴结的数量以及CCI。应用以下公式计算单因素CUSUM值:CUSUM n =Xn -μ+CUSUM n -1,其中Xn 代表每个病例的OT,而μ是整个队列的平均OT;在这个方程中,CUSUM0被设置为0。多因素CUSUM值的计算方法参照以往的研究[13]。根据本队列中对应的均值,所有变量都有目标值,标记为T0,而每个案例的值标记为T n ;每个变量的得分用公式S=T n -T0进行计算。当一个病例达到整个队列的平均值(更短的OT,更少的BL,更低的CCI,以及更多回收到的第9和11组淋巴结数量)时,T n 的值被记录为0。当一个病例无法达到平均值时(更大的OT、BL和CCI以及更少回收到的第9和11组淋巴结数量),T n 记录为1。本研究中多因素CUSUM的方程定义为CUSUM n =S n +CUSUM n -1,并且CUSUM0也设置为0。以病例数为横坐标,OT的CUSUM值为纵坐标进行学习曲线拟合。当P<0.05时,认为曲线拟合成功,用R 2来表示拟合优度。CUSUM拟合曲线顶点为跨越学习曲线所需的最小累计手术病例数,以此为依据划分不同的学习曲线阶段。

1.6. 手术步骤

所有RAG手术均通过4个机器人端口和一个辅助端口进行D2淋巴结清扫术。LAG加D2淋巴结清扫术步骤和胃癌区域淋巴结分组参照日本胃癌治疗指南[12]实施。主要手术步骤如下。1)胃大弯游离:从胃结肠韧带和胃脾韧带中游离胃大弯网膜(从内侧到外侧);离断左侧胃网膜血管,清扫第4 s组和4 d组淋巴结;离断胃短血管,清扫第2、10、11组淋巴结。2)幽门下游离:沿中结肠动脉分离至上结肠根部,暴露胰头并清扫第6组淋巴结;行D2淋巴结清扫的患者同时也需要清扫第14组淋巴结,并结扎胃网膜右静脉和动脉。3)幽门上分离和十二指肠分离:分离胰腺和十二指肠上方的区域,使用机器人内腕器械帮助引导线性切割闭合器离断十二指肠。4)胰上区淋巴结清扫:横断十二指肠后,胃右动、静脉显露出来,分离小网膜,清扫肝动脉周围的淋巴结(第5、7、8、9和12a组淋巴结),膈肌周围的淋巴结(第1和3组淋巴结),以及脾动脉周围的淋巴结(第11p组淋巴结)。5)胃切除:线性切割闭合器横断胃体,保留1/4容积残胃。6)重建和闭合:重建采用毕式胃空肠吻合术或R-Y胃空肠吻合术。7)标本取出:取正中切口4 cm,取出切除胃标本,分层缝合关腹。

1.7. 统计学处理

使用SPSS 25.0统计软件进行统计分析。符合正态分布的计量资料采用均数±标准差( ±s)表示,组间比较采用t检验;计数资料用例数(%)表示,组间比较采用χ2检验。P<0.05为差异具有统计学意义。多变量线性回归分析用于筛选影响OT的因素(包括性别、年龄、BMI、ASA评分、组织学分级、TNM分期、肿瘤大小、BL、CCI、首次胀气时间、饮食时间,住院时间以及第7、8a、9、11p和12a组淋巴结)。建立线性回归方程,计算标准化OT。

2. 结 果

2.1. 一般资料

LAG和RAG组在年龄、性别、BMI、ASA分级、术后首次排气时间、术后首次进食时间、住院时间及术后并发症的差异均无统计学意义(均P>0.05,表1)。与LAG组比较,RAG组的术中BL显著降低(P=0.046),但RAG组的平均OT显著延长(P=0.015)。LAG组中转开腹手术的中转率比RAG组高,差异有统计学意义(P=0.043),LAG组中2例患者因脾静脉损伤出血接受中转开腹手术。

表1.

2组一般情况的比较

Table 1 Comparison of general information of patients in 2 groups

| 组别 | n | 年龄/岁 | 男/女 | BMI/(kg·m-2) | ASA分级/[例(%)] | 术中失血量/mL | OT/min | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | |||||||

| LAG组 | 81 | 56.35±3.28 | 50/31 | 25.93±1.41 | 17(58.0) | 21(38.2) | 3(3.8) | 156.83±98.37 | 281.48±32.69 |

| RAG组 | 27 | 44.84±2.92 | 16/11 | 23.64±1.08 | 15(59.3) | 11(40.7) | 1(3.7) | 133.80±95.28 | 304.45±42.08 |

| t/χ 2 | 3.260 | 2.936 | 1.947 | 2.978 | -0.034 | 0.002 | |||

| P | 0.600 | 0.947 | 0.288 | 0.899 | 0.046 | 0.015 | |||

| 组别 |

首次排气 时间/d |

进食时间/d | 住院时间/d |

中转开腹 手术/[例(%)] |

胃肠道重建/[例(%)] | 肿瘤大小/cm | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 毕式吻合 | R-Y吻合 | ||||||

| LAG组 | 3.02±0.77 | 4.27±1.01 | 7.43±1.01 | 2(2.5) | 69(85.2) | 12(14.8) | 3.15±0.55 |

| RAG组 | 2.76±0.83 | 3.92±0.91 | 7.32±0.75 | 0 | 24(88.9) | 3(11.1) | 3.10±0.40 |

| t/χ 2 | 4.321 | 2.990 | 1.446 | 1.923 | 2.996 | 1.945 | |

| P | 0.145 | 0.124 | 0.610 | 0.043 | 0.173 | 0.597 | |

| 组别 | TNMs分期/[例(%)] | R1切除边缘/[例(%)] | 肿瘤复发及相关死亡/[例(%)] | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | IIa | IIb | IIIa | IIIb | IIIc | |||

| LAG组 | 0 | 4(4.9) | 16(19.8) | 40(49.4) | 17(21.0) | 4(4.9) | 1(1.2) | 0 |

| RAG组 | 0 | 2(7.4) | 7(25.9) | 14(51.9) | 3(11.1) | 1(3.7) | 0 | 0 |

| t/χ 2 | 3.268 | 1.978 | — | |||||

| P | 0.857 | 1.000 | — | |||||

| 组别 | 组织学分级/[例(%)] |

皮下气肿/ [例(%)] |

心脏并发症/[例(%)] |

肺部感染/ [例(%)] |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 低分化腺癌 | 中分化腺癌 | 高分化腺癌 | 未分化腺癌 | ||||

| LAG组 | 40(49.4) | 15(18.5) | 9(11.1) | 17(21.0) | 7(8.6) | 6(7.4) | 6(7.4) |

| RAG组 | 12(44.4) | 6(22.2) | 3(11.2) | 6(22.2) | 2(7.4) | 2(7.4) | 2(7.4) |

| t/χ 2 | 2.589 | 1.978 | 1.589 | 2.478 | |||

| P | 0.997 | 0.875 | 0.813 | 0.813 | |||

| 组别 |

十二指肠瘘/ [例(%)] |

低蛋白血症/[例(%)] | 胰瘘/[例(%)] | 吻合口出血 | 腹腔出血/[例(%)] | 吻合口瘘/[例(%)] | CCI评分 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LAG组 | 4(4.9) | 6(7.4) | 4(4.9) | 3(3.7) | 3(3.7) | 1(1.2) | 23.56±6.50 |

| RAG组 | 1(3.7) | 2(7.4) | 1(3.7) | 1(3.7) | 0 | 0 | 19.40±8.10 |

| t/χ 2 | 2.768 | 3.114 | 2.732 | 2.589 | 0.006 | 0.013 | -0.019 |

| P | 0.753 | 0.813 | 0.753 | 0.785 | 0.002 | 0.005 | 0.025 |

LAG:腹腔镜辅助胃切除术;RAG:机器人辅助胃切除术;BMI:体重指数;ASA:美国麻醉医师协会;OT:手术时间;CCI:综合并发症指数。

2.2. 肿瘤组织学及术后结果

2组之间在肿瘤大小、组织学分级和临床分期上差异均无统计学意义(均P>0.05);与LAG组相比,RAG组的CCI评分较低(P=0.041,表1)。LAG组有1例R1切缘(1.2%),此病例存在术前未发现的胃内转移病灶;RAG组未发现R1切缘病例。2组均无患者在30 d内死亡。术后随访12个月观察到2组均无肿瘤复发,差异无统计学意义(P>0.05,表1)。此外,LAG组术后出现严重并发症(基于Clavien-Dindo分类)Ⅰ级的患者17例(20.9%),Ⅱ级26例(32.1%),Ⅲa级3例(3.7%),Ⅲb级4例(4.9%);RAG组术后出现严重并发症Ⅰ级的患者6例(22.22%),Ⅱ级8例(29.62%),Ⅲa级1例(3.70%),2组患者在Ⅰ、Ⅱ级并发症发生率的差异无统计学意义(均P>0.05),LAG组III级以上并发症的发生率较高,差异有统计学意义(P=0.003)。

与LAG组相比,RAG组清扫的淋巴结数量更多(P=0.003),其中在9组(P=0.038)和11p组(P=0.015)淋巴结的清扫中存在明显优势(表2)。

表2.

2组淋巴结清扫数量的比较

Table 2 Comparison of lymph nodes dissected of patients in 2 groups

| 组别 | n | 淋巴结清扫总数/个 | 7组/个 | 8a组/个 | 9组/个 | 11p组/个 | 12a组/个 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LAG组 | 81 | 32.78±5.98 | 2.52±0.92 | 2.02±1.04 | 2.78±1.30 | 1.99±0.84 | 2.64±0.97 |

| RAG组 | 27 | 37.32±8.26 | 3.44±1.50 | 2.28±1.06 | 3.56±1.66 | 2.48±0.96 | 2.92±1.00 |

| χ 2 | 0.017 | 3.116 | 2.978 | 2.245 | 0.019 | 3.116 | |

| P | 0.003 | 0.704 | 0.287 | 0.038 | 0.015 | 0.214 |

LAG:腹腔镜辅助胃切除术;RAG:机器人辅助胃切除术。

2.3. 学习曲线分析

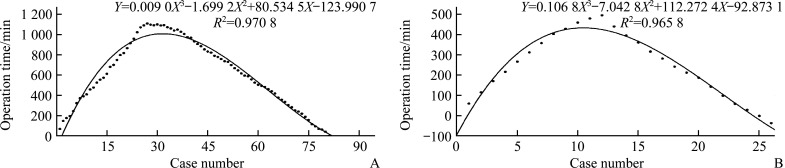

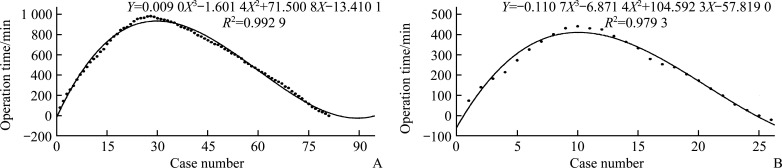

影响OT因素的多元线性回归分析表明:BL、9组和11p组淋巴结对OT有显著影响,而其他因素对OT无显著影响。根据用于评估机器人辅助手术学习曲线的单因素CUSUM分析(图1),本研究结果表明:对于OT,RAG的界限为第12个案例,LAG的界限为第30个案例。然而,在多因素CUSUM分析中,当设置5个变量进行描述时,RAG的界限为第10例,R 2较高值为0.979 3;LAG界限为第28例,R 2较高值为0.992 9(图2)。根据多因素CUSUM分析中的界限将其分为2个亚组(表3)。前半部分(first half,FH)包括临界限之前的10例RAG病例和28例LAG病例,后半部分(second half,SH)包括17例RAG病例和53例LAG病例,资料和手术结果见表3。

图1.

基于单因素累积和分析LAG组(A)和RAG组(B)学习曲线的比较

Figure 1 Comparison of learning curve in the LAG group (A) and the RAG group (B) based on dimensional accumulation and cumulative sum analysis

图2.

基于多因素累积和分析LAG组(A)和RAG组(B)学习曲线的比较

Figure 2 Comparison of learning curve in the LAG group (A) and the RAG group (B) based on multi-dimensional accumulation and cumulative sum analysis

表3.

RAG组和LAG组的学习曲线2个亚组的比较

Table 3 Learning curves comparison of patients in the RAG group and the LAG group between the 2 subgroups

| 阶段 | 男/女 | 年龄/岁 |

ASA I/II/III级/ 例 |

BMI/ (kg·m-2) |

R0/R1切除边缘 | OT/min |

机器设置 时间/min |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FH(n=38) | LAG(n=28) | 10/18 | 60.32±4.62 | 15/10/3 | 24.04±1.53 | 28/0 | 320.36±21.81 | — |

| RAG(n=10) | 6/4 | 57.30±5.27 | 6/3/1 | 23.50±1.35 | 10/0 | 350.50±10.92 | 26.3±10.56 | |

| t/χ 2 | 3.189 | 2.936 | 2.435 | 3.331 | 1.926 | -0.001 | ||

| P | 1.000 | 0.095 | 0.782 | 0.334 | 1 | <0.001 | ||

| SH(n=70) | LAG(n=53) | 30/23 | 57.30±3.72 | 32/21/0 | 23.87±1.36 | 52/1 | 260.47±11.53 | — |

| RAG(n=17) | 10/7 | 58.20±286 | 11/6/0 | 23.73±0.88 | 17/0 | 274.00±21.23 | 15.87±5.08 | |

| t/χ 2 | 3.178 | 1.999 | 2.048 | 2.769 | 3.117 | 0.011 | -0.015 | |

| P | 0.814 | 0.391 | 0.979 | 0.651 | 1.000 | 0.030 | 0.017* | |

| 0.010* |

| 阶段 | 术中BL/mL | 肿瘤大小/cm | CCI评分 | TNMs分期/[例(%)] | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | IIa | IIb | IIIa | IIIb | IIIc | ||||

| FH(n=38) | 296.25±78.78 | 3.11±0.66 | 28.29±3.68 | 0 | 2(7.1) | 5(17.9) | 14(50.0) | 7(25.0) | 0(0.0) |

| 235.50±67.23 | 3.05±0.50 | 26.60±4.40 | 0 | 0 | 2(20.0) | 6(60.0) | 2(20.0) | 0(0.0) | |

| t/χ 2 | 3.114 | 2.117 | 3.005 | 5.112 | |||||

| P | 0.037* | 0.804 | 0.245 | 0.952 | |||||

| SH(n=70) | 116.79±17.79 | 3.18±0.49 | 21.06±6.29 | 0 | 2(3.8) | 11(20.7) | 26(49.1) | 10(18.9) | 4(7.5) |

| 66.00±18.54 | 3.13±0.35 | 14.60±6.20 | 0 | 2(11.8) | 5(29.4) | 8(47.0) | 1(5.9) | 1(5.9) | |

| t/χ 2 | -0.059 | 1.993 | -0.001 | 3.176 | 3.145 | ||||

| P | <0.001 | 0.737 | 0.001 | 0.581 | 0.581 | ||||

| <0.001* | |||||||||

| 阶段 | 组织学分级例数(低/中/高/未分化) | 首次排气时间/d | 首次进食时间/d | 住院时间/d |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FH(n=38) | 14/6/3/5 | 3.140.80 | 4.50±0.69 | 7.43±0.79 |

| 5/2/3/0 | 2.800.53 | 4.20±0.70 | 7.40±0.84 | |

| t/χ 2 | 3.222 | 2.145 | 2.995 | 1.179 |

| P | 0.334 | 0.625 | 0.871 | 0.924 |

| SH(n=70) | 26/9/6/12 | 2.96±0.76 | 4.15±1.13 | 7.43±1.12 |

| 8/3/0/6 | 2.93±0.96 | 4.13±0.99 | 7.27±0.70 | |

| t/χ 2 | 2.321 | 2.168 | 3.111 | 2.421 |

| P | 0.564 | 0.903 | 0.957 | 0.586 |

*RAG案例的FH和SF之间的比较。FH:前半部分;SF:后半部分;ASA:美国麻醉医师协会;BMI:体重指数;OT:手术时间;CCI:综合并发症指数;BL:失血量;LAG:腹腔镜辅助胃切除术;RAG:机器人辅助胃切除术。

本研究结果显示:2个亚组中RAG的OT仍然长于LAG组(分别P<0.001和P=0.030),2个亚组中RAG组的术中BL小于LAG组,差异均有统计学意义(分别P=0.037和P<0.001)。FH中RAG的CCI与LAG相似(P=0.245);而SH中RAG组的CCI显著低于LAG组(P=0.001),清扫的淋巴结数量更多的(P=0.003,表4)。同时,在SH中,RAG组中清扫的9和11p组淋巴结数量高于LAG组,差异均有统计学意义(分别P<0.001和P=0.003,表4)。2个亚组在第一次排气时间、饮食时间和手术后住院时间中的差异均无统计学意义(均P>0.05)。

表4.

2组学习曲线中淋巴结清扫数量的比较

Table 4 Comparison of lymph nodes dissected of patients in 2 groups in the learning curve

| 阶段 | 淋巴结清扫总数/个 | 7组/个 | 8a组/个 | 9组/个 | 11p组/个 | 12a组/个 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FH(n=38) | LAG(n=28) | 27.50±6.03 | 1.76±0.96 | 1.07±0.94 | 1.640.91 | 1.31±0.79 | 2.07±0.77 |

| RAG(n=10) | 30.20±3.99 | 1.30±1.16 | 1.60±0.97 | 1.90±0.88 | 2.10±1.23 | 2.30±0.95 | |

| t | 3.114 | 2.980 | 1.936 | 1.119 | 0.015 | 3.338 | |

| P | 0.198 | 0.084 | 0.138 | 0.444 | 0.036 | 0.452 | |

| SH(n=70) | LAG(n=53) | 35.57±3.64 | 3.01±0.76 | 2.53±0.67 | 3.38±1.06 | 2.300.53 | 2.94±0.93 |

| RAG(n=17) | 42.07±6.81 | 3.53±0.92 | 2.73±0.88 | 4.67±0.98 | 2.97±0.72 | 3.33±0.82 | |

| t | 2.982 | 0.001 | 3.691 | -0.011 | 0.009 | 3.125 | |

| P | 0.003 | 0.053 | 0.333 | <0.001 | 0.044 | 0.146 | |

| <0.001* | <0.001* | 0.037* |

*RAG案例的FH和SF之间的比较。FH:前半部分;SF:后半部分;LAG:腹腔镜辅助胃切除术;RAG:机器人辅助胃切除术。

此外,SH阶段的OT和机器组装时间比FH短(分别为P=0.001和P=0.017),FH阶段的CCI高于SH(P=0.001),手术BL在FH阶段高于SH阶段(P<0.001),SH阶段中清扫的第9、11p和7组淋巴结的数量明显大于FH阶段的清扫数量(分别P<0.001、P=0.037、 P<0.001,表4)。

3. 讨 论

近年来,越来越多的临床证据表明机器人辅助手术对胃癌患者的安全性和有效性与腹腔镜辅助手术和开放手术相似[14-15],机器人手术已被证明是胃癌患者外科治疗的有效选择[16-18]。

本研究发现RAG加D2淋巴结清扫术具有术中出血量较少,中转率低的特点;中转患者术后并发症的发生率往往较高且肿瘤预后结果较差,机器人胃癌手术的低中转率可以有助于患者术后恢复和改善肿瘤分期结果。这与之前的几项临床研究[19-20]结果相似,与LAG相比,使用达芬奇手术机器人的RAG术具有类似的优势。本研究结果显示:与LAG相比,RAG组的OT明显延长,可能与额外的机器人装机时间、机械臂移动和器械更换缓慢等因素有关;但是通过学习曲线分析发现,RAG组SH阶段的OT比FH阶段的时间明显缩短,OT缩短表明手术医师克服学习曲线后手术技能提高。此外,本研究发现RAG组的患者出现严重并发症(Clavien-Dindo分类≥IIIa级)的发生率显著降低,CCI也更低,这与2个大型临床研究[21-22]的结果相似,也证实了机器人辅助手术并发症较少,有利于术后康复。

在肿瘤学结果方面,RAG组和LAG组在组织学分级、病理分期、肿瘤大小和切除边缘方面差异均无统计学意义;但RAG组中清扫的淋巴结总数大于LAG组,并且在第9组和11p组淋巴结清扫时表现突出,在胰上淋巴结清扫中有明显优势。相关研究[23]已经证实D2淋巴结清扫术在胃癌根治术中的重要性,有助于改善远期疗效,胰上淋巴结清扫又是胃癌D2根治性切除的关键和难点,主要包括第7、8、9、11p和12组淋巴结的清扫[24];胰上区解剖结构复杂,区域内存在腹腔干、门静脉、脾静脉等重要血管,在胃手术D2淋巴结清扫术中,严重的术中并发症之一是胰上区血管损伤。本研究LAG组中出现2例由于胰上区脾血管损伤而导致中转开腹手术,与腹腔镜手术相比,RAG凭借其灵巧的内腕运动、3D视觉、震颤过滤和运动缩放等技术优势,方便外科医生充分暴露血管,完成胰上区淋巴结清扫,避免血管损伤。因此,RAG的灵巧解剖可以帮助手术医师在关键区域进行充分淋巴结清扫,可能有利于胃癌患者的长期预后。此外,达芬奇机器人独特的内腕运动可以使外科医生在暴露胰上区域时避免对胰腺造成不必要的压迫,从而减少胰腺损伤,降低胰漏的发生风险。一些研究[24-25]在达芬奇机器人辅助下胃癌根治中也报告了类似的研究结果。

本研究中,通过多因素CUSUM分析,RAG组的拟合曲线在第10例手术时达到最高点;而LAG组的学习曲线最高点为第28例,外科医生必须积累28例以上的手术经验才能完成学习提高阶段。因此,本研究中RAG的学习曲线比LAG的学习曲线具有更少的截止案例。笔者认为手术机器人的独特设计可能有助于提高学习效率。通过安装在机械臂上由主刀医生自主控制的高清3D内窥镜,手术视野被放大了10倍,主刀医生可以更好地进行内窥镜控制,在减少对助手依赖的同时获得稳定、清晰的手术视野。此外,机器人手术器械具有7个自由度,可以实现90°关节,540°旋转,提供类似手腕的运动能力,改善了手术的灵活性和人体工程学,实现在较小的空间内进行精细操作。上述机器人的独特优势必然为手术者实施胰腺上缘的血管游离和淋巴结清扫提供帮助。多项研究[26-27]表明机器人技术可以使手术医师的灵活性提高65%,减少93%基于技能的错误,并将完成给定任务所需的时间缩短40%。而且,与LAG中杠杆模式的反向操作不同,外科医师在机器人主从控制模式下通过动作映射进行同向操作,类似于人类的自然动作行为,从而让外科医师易于快速而熟练地掌握相关手术技巧。手术机器人的技术优势降低了手术复杂程度,从而缩短了外科手术学习曲线。

根据本研究亚组分析,RAG和LAG的学习曲线SH阶段在OT、BL、CCI和淋巴结(第9、7、11p组)清扫数量方面都有明显优势,这说明频繁的手术操作和全面的操作实践有助于外科医生提高手术技能,积累经验,从而获得良好的手术效果。此外,在本研究中,参与研究的外科医生自2017年起就独立实施LAG,从2018年开始,RAG和LAG实施过程出现重叠;考虑到RAG手术环境和手术步骤与LAG相似,这种前期经验可能有益于RAG学习曲线的提升[28-31]。另外,RAG在SH阶段的OT短于FH阶段,缩短的OT说明手术医师在克服学习曲线后表现出手术技能的提高和手术经验的积累。同时,有先前的临床研究发现,随着手术经验的积累,OT将显著缩短,这表明熟练掌握机器人辅助手术技能后,在学习曲线延伸阶段,RAG的OT与LAG的OT可表现出相似性[32-33]。综上,随着学习曲线的延伸和手术技能的熟练掌握,机器人手术的固有缺陷(较长OT)将会得到改善。

本研究存在局限性:首先,本研究受到非随机性的限制,可能存在选择偏倚和信息偏倚;其次,数据是基于单个外科医生的经验,可能会降低结果的普遍性;再次,缺乏总生存期、无病生存期的长期随访数据;最后,RAG组的样本量相对较小,并且属于单中心的研究,未来需要进行多中心随机对照研究来提供更高级的循证医学证据。

机器人技术有助于经验丰富的外科医生快速学习掌握RAG技能,超越机器人学习曲线达到熟练阶段需要的最少手术例数为10例,并且与LAG相比,RAG在第9组和11组淋巴结清扫中表现出明显优势。但未来仍需聚焦于使用国产手术机器人进行随访时间更长的多中心随机对照试验。

基金资助

湖南省重点研发计划项目(2021SK2001)。

This work was supported by the Key Research and Development Program of Hunan Province (2021SK2001), China.

利益冲突声明

作者声称无任何利益冲突。

作者贡献

谢京茂 研究设计,数据分析,论文撰写与修改;雷阳、张皓、刘毅辉 数据采集;易波 论文指导。所有作者阅读并同意最终的文本。

原文网址

http://xbyxb.csu.edu.cn/xbwk/fileup/PDF/202305716.pdf

参考文献

- 1. Hyung WJ, Yang HK, Park YK, et al. Long-term outcomes of laparoscopic distal gastrectomy for locally advanced gastric cancer: the KLASS-02-RCT randomized clinical trial[J]. J Clin Oncol, 2020, 38(28): 3304-3313. 10.1200/JCO.20.01210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Shi Y, Xu XH, Zhao YL, et al. Long-term oncologic outcomes of a randomized controlled trial comparing laparoscopic versus open gastrectomy with D2 lymph node dissection for advanced gastric cancer[J]. Surgery, 2019, 165(6): 1211-1216. 10.1016/j.surg.2019.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ebihara Y, Kurashima Y, Murakami S, et al. Short-term outcomes of robotic distal gastrectomy with the “preemptive retropancreatic approach”: a propensity score matching analysis[J]. J Robot Surg, 2022, 16(4): 825-831. 10.1007/s11701-021-01306-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ojima T, Nakamura M, Hayata K, et al. Short-term outcomes of robotic gastrectomy vs laparoscopic gastrectomy for patients with gastric cancer: a randomized clinical trial[J]. JAMA Surg, 2021, 156(10): 954-963. 10.1001/jamasurg.2021.3182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. 杨小峰, 苏文斌. 腹腔镜下腹部无切口结直肠癌切除对比传统腹腔镜下结直肠癌切除可行性和安全性的Meta分析[J]. 中南大学学报(医学版), 2017, 42(1): 88-97. 10.11817/j/issn.1672-7374.2017.01. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; YANG Xiaofeng, SU Wenbin. Laparoscopic-assisted resection for colorectal cancer without incision at abdomen versus traditional laparoscopic resection: A Meta-analysis[J]. Journal of Central South University. Medical Science, 2017, 42(1): 88-97. 10.11817/j/issn.1672-7374.2017.01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Mala T, Førland D, Skagemo C, et al. Early experience with total robotic D2 gastrectomy in a low incidence region: surgical perspectives[J]. BMC Surg, 2022, 22(1): 137. 10.1186/s12893-022-01576-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ojima T, Nakamura M, Hayata K, et al. Robotic D2 total gastrectomy with en-mass removal of the spleen and body and tail of the pancreas for locally advanced gastric cancer[J]. Surg Oncol, 2020, 35: 22-23. 10.1016/j.suronc.2020.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Barrows CE, Ore AS, Critchlow J, et al. Robot-assisted technique for total gastrectomy and D2 lymphadenectomy with anomalous vasculature[J]. Ann Surg Oncol, 2018, 25(4): 964. 10.1245/s10434-017-6304-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. van Boxel GI, Ruurda JP, van Hillegersberg R. Robotic-assisted gastrectomy for gastric cancer: a European perspective[J]. Gastric Cancer, 2019, 22(5): 909-919. 10.1007/s10120-019-00979-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Caruso S, Patriti A, Roviello F, et al. Robot-assisted laparoscopic vs open gastrectomy for gastric cancer: systematic review and meta-analysis[J]. World J Clin Oncol, 2017, 8(3): 273-284. 10.5306/wjco.v8.i3.273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Japanese Gastric Cancer Association . Japanese classifification of gastric carcinoma: 3rd English edition[J]. Gastric Cancer, 2011, 14(2): 101-112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Japanese Gastric Cancer Association . Japanese gastric cancer treatment guidelines 2018 (5th edition)[J]. Gastric Cancer, 2021, 24(1): 1-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Yu J, Rao SR, Lin Z, et al. The learning curve of endoscopic thyroid surgery for papillary thyroid microcarcinoma: CUSUM analysis of a single surgeon’s experience[J]. Surg Endosc, 2019, 33(4): 1284-1289. 10.1007/s00464-018-6410-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Obama K, Kim YM, Kang DR, et al. Long-term oncologic outcomes of robotic gastrectomy for gastric cancer compared with laparoscopic gastrectomy[J]. Gastric Cancer, 2018, 21(2): 285-295. 10.1007/s10120-017-0740-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kim JS, Batajoo H, Son T, et al. Delta-shaped gastroduodenostomy using a robotic stapler in reduced-port totally robotic gastrectomy: its safety and efficiency compared with conventional anastomosis techniques[J]. Sci Rep, 2020, 10(1): 14729. 10.1038/s41598-020-71807-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Robotic and Laparoscopic Surgery Committee of Chinese Research Hospital Association . Expert consensus on robotic surgery in gastric cancer (2015 edition)[J]. Journal of Chinese Research Hospitals, 2016, 3(1): 22-28. https:// 10.3760/cma.j.issn.441530-20210727-00299. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17. 苗长丰, 詹渭鹏, 张文涛, 等. 机器人辅助胃癌根治术的安全性及可行性分析[J]. 机器人外科学杂志(中英文), 2021, 2(3): 162-169. [Google Scholar]; MIAO Changfeng, ZHAN Weipeng, ZHANG Wentao, et al. Safety and feasibility analysis of robot-assisted radical gastrectomy for gastric cancer [J]. Journal of robotic surgery (English & Chinese), 2021, 2(3): 162-169. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Chinese Society of Laparoscopic Surgery, Chinese College of Endoscopists, Chinese Medical Doctor Association; Robotic and Laparoscopic Surgery Committee of Chinese Research Hospital Association; Chinese Laparoscopic Gastrointestinal Surgery Study Group , “Expert consensus on quality control of the laparoscopic radical resection for gastric cancer in China (2017. edition), ” Chinese Journal of Digestive Surgery, 2017, 16, 6, 539–547. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lu J, Zheng CH, Xu BB, et al. Assessment of robotic versus laparoscopic distal gastrectomy for gastric cancer[J]. Ann Surg, 2020, 273(5): 858-867. 10.1097/sla.0000000000004466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Li ZY, Zhou YB, Li TY, et al. Robotic gastrectomy versus laparoscopic gastrectomy for gastric cancer: A multicenter cohort study of 5. 402 Patients in China[J/OL]. Ann Surg, 2023, 277(1): e87-e95[2023-01-05]. 10.1097/SLA.0000000000005046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Shen WS, Xi HQ, Wei B, et al. Robotic versus laparoscopic gastrectomy for gastric cancer: comparison of short-term surgical outcomes[J]. Surg Endosc, 2016, 30(2): 574-580. 10.1007/s00464-015-4241-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Wang WJ, Li HT, Yu JP, et al. Severity and incidence of complications assessed by the Clavien-Dindo classification following robotic and laparoscopic gastrectomy for advanced gastric cancer: a retrospective and propensity score-matched study[J]. Surg Endosc, 2019, 33(10): 3341-3354. 10.1007/s00464-018-06624-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Faiz Z, Hayashi T, Yoshikawa T. Lymph node dissection for gastric cancer: establishment of D2 and the current position of splenectomy in Europe and Japan[J]. Eur J Surg Oncol, 2021, 47(9): 2233-2236. 10.1016/j.ejso.2021.04.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kim YW, Reim D, Park JY, et al. Role of robot-assisted distal gastrectomy compared to laparoscopy-assisted distal gastrectomy in suprapancreatic nodal dissection for gastric cancer[J]. Surg Endosc, 2016, 30(4): 1547-1552. 10.1007/s00464-015-4372-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Wang WJ, Li HT, Yu JP, et al. Severity and incidence of complications assessed by the Clavien-Dindo classification following robotic and laparoscopic gastrectomy for advanced gastric cancer: a retrospective and propensity score-matched study[J]. Surg Endosc, 2019, 33(10): 3341-3354. 10.1007/s00464-018-06624-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ruhle BC, Ferguson Bryan A, Grogan RH. Robot-assisted endocrine surgery: indications and drawbacks[J]. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A, 2019, 29(2): 129-135. 10.1089/lap.2018.0308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ruurda JP, Broeders IA, Simmermacher RP, et al. Feasibility of robot-assisted laparoscopic surgery: an evaluation of 35 robot-assisted laparoscopic cholecystectomies[J]. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech, 2002, 12(1): 41-45. 10.1097/00129689-200202000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Huang KH, Lan YT, Fang WL, et al. Comparison of the operative outcomes and learning curves between laparoscopic and robotic gastrectomy for gastric cancer[J/OL]. PLoS One, 2014, 9(10): e111499[2022-12-02]. 10.1371/journal.pone.0111499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kim MS, Kim WJ, Hyung WJ, Comprehensive learning curve of robotic surgery : Discovery from a multicenter prospective trial of robotic gastrectomy[J]. Ann Surg, 2021, 273(5): 949-956. 10.1097/SLA.0000000000003583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. 冯存成, 高永建, 宋德锋, 等. 达芬奇机器人结直肠癌根治术学习曲线研究[J]. 中国临床研究, 2022, 35(8): 1073-1078. 10.13429/j.cnki.cjcr.2022.08.009. 35445495 [DOI] [Google Scholar]; FENG Cuncheng, GAO Yongjian, SONG Defeng, et al. Study on learning curve of Da Vinci robot assisted radical resection of colorectal cancer[J]. Chinese Journal of Clinical Research, 2022, 35(8): 1073-1078. 10.13429/j.cnki.cjcr.2022.08.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31. 田园, 林叶成, 李勇, 等. 达芬奇机器人胃癌手术学习曲线[J]. 中华腔镜外科杂志(电子版), 2020, 13(3): 151-155. [Google Scholar]; TIAN Yuan, LIN Yecheng, LI Yong, et al. Da Vinci robot gastric cancer surgery learning curve [J]. Chinese Journal of Endoscopic Surgery. Electronic version, 2020, 13(3): 151-155. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Ielpo B, Duran H, Diaz E, et al. Robotic versus laparoscopic surgery for rectal cancer: a comparative study of clinical outcomes and costs[J]. Int J Colorectal Dis, 2017, 32(10): 1423-1429. 10.1007/s00384-017-2876-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Caruso R, Vicente E, Núñez-Alfonsel J, et al. Robotic-assisted gastrectomy compared with open resection: a comparative study of clinical outcomes and cost-effectiveness analysis[J]. J Robotic Surg, 2020, 14(4): 627-632. 10.1007/s11701-019-01033-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]