Abstract

Objective

Shelter hospital was an alternative way to provide large-scale medical isolation and treatment for people with mild coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). Due to various reasons, patients admitted to the large shelter hospital was reported high level of psychological distress, so did the healthcare workers. This study aims to introduce a comprehensive and multifaceted psychosocial crisis intervention model.

Methods

The psychosocial crisis intervention model was provided to 200 patients and 240 healthcare workers in Wuhan Wuchang shelter hospital. Patient volunteers and organized peer support, client-centered culturally sensitive supportive care, timely delivery of scientific information about COVID-19 and its complications, mental health knowledge acquisition of non-psychiatric healthcare workers, group activities, counseling and education, virtualization of psychological intervention, consultation and liaison were exhibited respectively in the model. Pre-service survey was done in 38 patients and 49 healthcare workers using the Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7-item (GAD-7) scale, the Patient Health Questionnaire 2-item (PHQ-2) scale, and the Primary Care PTSD screen for the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th edition (PC-PTSD-5). Forty-eight healthcare workers gave feedback after the intervention.

Results

The psychosocial crisis intervention model was successfully implemented by 10 mental health professionals and was well-accepted by both patients and healthcare workers in the shelter hospital. In pre-service survey, 15.8% of 38 patients were with anxiety, 55.3% were with stress, and 15.8% were with depression; 16.3% of 49 healthcare workers were with anxiety, 26.5% were with stress, and 22.4% were with depression. In post-service survey, 62.5% of 48 healthcare workers thought it was very practical, 37.5% thought more practical; 37.5% of them thought it was very helpful to relief anxiety and insomnia, and 27.1% thought much helpful; 37.5% of them thought it was very helpful to recognize patients with anxiety and insomnia, and 29.2% thought much helpful; 35.4% of them thought it was very helpful to deal with patients’ anxiety and insomnia, and 37.5% thought much helpful.

Conclusion

Psychological crisis intervention is feasible, acceptable, and associated with positive outcomes. Future tastings of this model in larger population and different settings are warranted.

Keywords: psychosocial support, crisis intervention, shelter hospital, anxiety, depression

Abstract

目的

方舱医院是一种能够为新型冠状病毒肺炎轻症患者提供大规模医疗隔离和治疗的可选择方式。由于各种原因,收治入方舱医院的患者反映出较高的心理困扰,医务人员也是如此。本研究旨在介绍一种在武汉武昌方舱医院实施的多方面的心理社会危机干预模型。

方法

对武汉武昌方舱医院内200名患者和240名医务人员提供心理社会危机干预模型,包括患者志愿者和有组织的同伴支持、以当事人为中心的文化敏感性支持护理、及时提供有关新型冠状病毒肺炎及其并发症的科学信息、非精神卫生医务人员的心理健康知识获取、团体活动、咨询和教育、心理干预的虚拟化、咨询和联络。使用7项广泛性焦虑障碍量表、2项患者健康问卷、基于精神疾病诊断与统计手册的创伤后应激障碍初级筛查问卷对方舱医院内38名患者和49名医务人员进行干预前评估。48名医务人员完成干预后反馈。

结果

心理社会危机干预模型由10名精神卫生专业人员实施,得到方舱医院的患者和医护人员的广泛认可。在干预前,38名患者中焦虑占15.8%,应激占55.3%,抑郁占15.8%;49名医务人员中焦虑占16.3%,应激占26.5%,抑郁占22.4%。48名医务人员完成干预后反馈,认为比较实用占62.5%,非常实用占37.5%;对于缓解自身焦虑与失眠比较有帮助占37.5%,非常有帮助占27.1%;对于识别患者的焦虑与失眠比较有帮助占37.5%,非常有帮助占29.2%;对于处理患者的焦虑与失眠比较有帮助占35.4%,非常有帮助占37.5%。

结论

该干预模型是可行且可接受的,并有积极的效果。未来该模式可应用于更大人群和不同环境中。

Keywords: 心理社会支持, 危机干预, 方舱医院, 焦虑, 抑郁

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) has sparked a pandemic worldwide and triggered continued concern[1-3]. This epidemic was extremely stressful for people in communities and subsequently increased the demand for mental health care.

Although severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection was related to high rate of intensive care and mortality, the majority of cases were reported to be mild[4]. In the early stage of COVID-19 epidemic, with rapidly increasing caseloads, general medical facilities quickly became overcrowded with ill patients[5]. Familial clusters of infection were reported because people in home isolation could still infect family members and community neighbors, which further increased utilization of medical resources and affected regional epidemic control[6]. Due to the shortage of hospital beds and the huge number of infections, shelter hospital was an alternative way to provide large-scale medical isolation and treatment under such a circumstance[7]. The idea is to turn a huge non-medical premise such as a stadium into a temporary medical facility with minimal changes[8]. Shelter hospital was similar to mobile medical units, makeshift hospitals or emergency field hospitals in disaster-relief situations such us Ebola outbreaks or earthquakes[5, 9-10]. During the COVID-19 pandemic, shelter hospital was established in many parts of the world where stadiums, warehouses, abandoned factories, and other facilities have been re-modelled for SARS-CoV-2 infection control and management use[11]. From January to March 2020, in Wuhan, 16 shelter hospitals were quickly established by converting the existent exhibition centers and stadiums, provided a total of 20 000 beds for patients with mild symptoms[7].

Previous study[12] has showed that severe infectious diseases often brought psychological distress to patients and medical workers, leading to post traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). In 2003, when the outbreak of severe acute respiratory symptoms (SARS) occurred, 10% of the respondents including patients, medical workers in SRAS wards, and those with friends or relatives contracting SARS were reported with PTSD symptoms[13]. During Ebola epidemic, medical workers easily showed psychosomatic symptoms that could be seen in patients with Ebola, and nurses may encounter the highest psychological stress in medical teams because of the frequent contacting with epidemic patients[14]. Paladino, et al[10] also reported the potential epidemic of PTSD symptoms in Ebola survivors and health-care workers. Park, et al[15] reported that in South Korea, one year after Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) outbreak, 42.9% of survivors had PTSD symptoms, and 27.0% had depressive symptoms.

Early psychological intervention or mental health support could reduce stress or the incidence of PTSD during the outbreak of infectious disease. During SARS, there were attempts at pre-job psychological training for front-line medical workers before they entered isolation wards[16]. A pilot study[17] showed that during SARS pandemic in Hong Kong, group debriefing could effectively release depressive symptoms for patients with chronic disease. These findings also suggest that early psychological intervention should be done as soon as possible when the shelter hospital is established. This article aims to introduce a comprehensive and multifaceted psychosocial intervention model and service challenges in a large, short-term shelter hospital setting during COVID-19 pandemic.

1. Subjects and methods

1.1. Subjects

Wuhan Wuchang Hongshan Stadium was the first shelter hospital established during this coronavirus outbreak. It accommodated a maximum of 748 confirmed COVID-19 patients at one time. The whole multidisciplinary team consisted of 10 mental health professionals including 5 psychiatrists, 2 psychologists and 3 psychiatric nurses from the Second Xiangya Hospital of Central South University. Some of them were the key mental health providers in this shelter hospital. The goal was to provide onsite psychological support to both patients and healthcare workers.

The Wuchang shelter hospital was divided into 3 areas. The authors team worked in the area A that had 200 patients. The population we serviced included 200 mild COVID-19 patients, 705 nursing workers, and 165 medical doctors. The ratio of mental health providers to recipients was 1꞉107. Due to the time constraint and disease control focus, we were not able to collect data on basic demographics of the population. Total 240 clinical personnel attended the course that stretched in 8 days due to limited available time every day.

There were several challenges the team had to face in providing psychological support to this population. The first and obvious one was shortage of staffing, and because of this, it was impossible to do routine screen evaluation on every patient or healthcare worker. With a goal to help everybody on the premise, we had to improvise a new method to provide basic psychosocial support to all, quickly screen out those who need mental health professional help and do outside referral for those who needed higher level of psychiatric care.

The second challenge was the mental health illiteracy and stigma. We noticed in the beginning that most of the patients showed no interest in talking with mental health professionals. They preferred to communicate with their medical providers. Similarly, the front-line healthcare workers did not want to openly talk about their psychological stress, instead, most of them chose to isolate and self-adjust[18].

The third challenge was caused by the overloading work schedule of every care provider. After the end of daily duty, everybody was exhausted and could not afford time or energy for a meaningful counsel or even a supportive conversation.

Last but not the least, physical distancing and wearing personal protective equipment (PPE) imposed a unique challenge to mental health evaluation and intervention. We had to largely rely on language and body gestures instead of facial expression or other important factors mental health specialists routinely use in daily practices.

1.2. Pre-service survey

In order to understand the population, we distributed a survey questionnaire through the most popular Chinese social media WeChat. The survey was comprised of 3 validated instruments: the Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7-item (GAD-7) scale [19], the Patient Health Questionnaire 2-item (PHQ-2) scale[20], and the Primary Care PTSD screen for the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th edition (PC-PTSD-5)[21]. We hoped to use this survey to learn the symptomology of mental health at the shelter hospital. and gauge the demand for psychological help. A total of 38 patients and 49 healthcare workers (8 doctors and 41 nurses) responded. The study involving human participants was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of the Second Xiangya Hospital, Central South University, China (No. 2020zdggwssj). The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

1.3. Methods

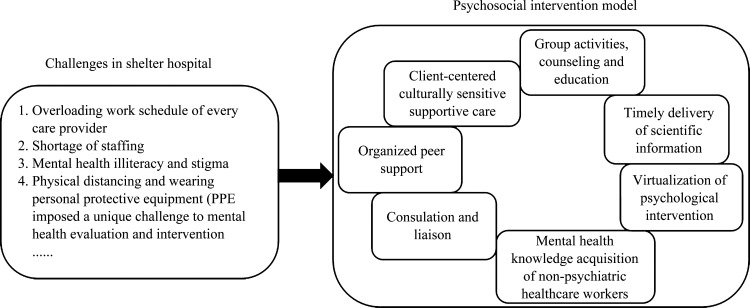

Figure 1 showed the psychosocial intervention model in shelter hospital.

Figure 1. Psychosocial intervention model.

1.3.1. Patient volunteers and organized peer support

One of the ways to solve inadequate staffing problem was to recruit patient volunteers to make meaningful contribution in mental health promotion. Wuchang shelter hospital Area A was physically divided into 10 wards. As patients with asymptomatic or mild SARS-CoV-2 infection were ambulatory, optimal activities were allowed and highly encouraged. Unsurprisingly, majority of patients voluntarily participated and organized themselves to help each other. Each ward elected a chief and a deputy chief who provided tremendous help in organizing and leading different activities prescribed by the mental health professional team. The chiefs usually had more life experience, better sense of responsibility, and some managerial ability. We provided training sessions teaching them psychological skills coping with stress in hopes that they could transfer the knowledge to other patients at large and act as intermediary for constructive feedback. They practiced active listening, learned skills to build friendships and camaraderie. In the meantime, some other volunteers were recruited to assist the ward chief. Volunteers were mostly young patients with high motivation to help others and relatively better health condition. While each patient’s autonomy was protected and highly respected, this kind of organized peer support system helped patients achieve confidence in fighting coronavirus and gain a sense of belonging that has been scientifically proven to be beneficial for mental health[22].

1.3.2. Client-centered culturally sensitive supportive care

Traditional family structure occupied an important position in Chinese culture. For many patients, “Family first” was an ideology. The study[23] found that the stronger the family cohesion, the lower the prevalence of mood disorders. Family function had more influence on people’s mental health than family structure[24]. We incorporated this tradition in our care approach and took consideration of this cultural difference from 2 perspectives. First, because family support playes a very important role in Chinese patient care, the team tried every possible way to build up a “big family” milieu that could provide everybody a sense of “family membership” and a strong network of support. Loving each other and living in a big “family” in the shelter hospital was more than a support group.

The stress factors were summarized in Table 1. The unique psychosocial situation put the patients at high risk for mental distress, including worrying about getting inadequate care, fearing medical decompensation and even death, unfamiliar shelter hospital environment, no family visitation because of isolation requirement, etc[25]. Many patients had concerns of rejection or discrimination by community residents after the treatment, which were reported in Ebola virus disease (EVD) and SARS epidemic[26-27]. Healthcare workers also expressed concerns about spreading the disease to their families, frustration about inadequate protective gear and a sense of not providing enough for their patients due to lack of experience and evidenced-based treatment[28-29].

Table 1.

Stress factors and supportive care to patients and healthcare workers

| Groups | Stress factors | Supportive care |

|---|---|---|

| COVID patients |

Fear of worsening condition and possibly death[25]; Worry about not receiving adequate medical care in shelter hospital; Noisy shelter hospital environment and lack of privacy; Feel guilty because of transmitting virus to other family members; Loneliness[25]; Worry about long term sequalae, and fear of rejection or discrimination by community[26-27]. |

Provide scientific education and debunk misinformation about coronavirus; Coordinate communication with medical providers; Provide support to activities of daily living; Provide sleep hygiene education. Provide eye masks and earplugs to reduce or block light or noise disruptive to sleep. Use table lamp to limit the amount of light and interference with other patients; Compassionate support to help examine and sort through guilty feelings. Provide skills to uncover guilt and address emotions in a positive way; Treat every patient with kindness and high respect. Create therapeutic “big family” milieu; Daytime activity “corner” to allow scheduled reading, arts and crafts, and other possible entertainments; Routine schedule for optimal level of exercise, meditation, relaxation, etc; Organize COVID-19 Webinar from medical experts to help understand more about the illness. Provide individualized services for patients with special needs. |

| Healthcare workers |

Having to wear PPE routinely is cumbersome, and creates difficulty in direct patient care; Long working hours and overwhelming workload[19]; Uncertainties about COVID-19 treatment[29]; Worry about contracting COVID-19 and transmitting to family members[19]; Communication barrier because of distancing and PPE. |

Work with hospital leadership to help organize work schedule and shift hours to limit duty hours and ensure adequate rest; Provide nutrition education and balanced diet; Opportunities for indoor exercise; Group activities with family remote involvement. Collaborate with local healthcare facilities to provide medical assistance to family members when necessary; Mutual support; WeChat web conference for healthcare workers to share feelings at work. |

PPE: Personal protective equipment.

In response to the unique stresses this population was experiencing, client-centered culturally sensitive supportive care was provided according to the characteristics of each group (Table 1). As for the front-line healthcare workers, emotional strain and physical exhaustion from caring large disproportionate number of patients made them more vulnerable to mental breakdown. In the shelter hospital our team serviced, normal duty hours per shift were scheduled to be 4 hours when there were enough workers but it usually took 2-3 extra hours to wait in line for changing protective gears and self-sanitizing. During off-duty time, each healthcare provider was mostly isolated in the room and did not have much interaction with colleagues. This left almost no room for any psychological support. Taking advantage of wireless technology, we organized various online group activities to promote communication and mutual support. Also, we launched activities to reach out to families that might be thousands of miles away. One example was “a letter from family on Women’s Day”, during which each participant received an electronic letter from family and was given a chance to openly talk out feelings and share with others in the group.

1.3.3. Timely delivery of scientific information about COVID-19 and its complications

Unfortunately, in the midst of battling SARS-CoV-2 infection, people also needed to fend off a myriad of misinformation that always could cause emotional distress. Therefore, delivering accurate and clear scientific information regarding the epidemic became one of the most important psychosocial interventions in the shelter hospital. The “Patient’s manual of shelter hospital” was the manual issued by the Medical Administration Bureau and Medical Management Service Guidance Center of NHC. This manual clearly described the background and rationale of the shelter hospital. Also explained were patient admission criteria, treatment goal, standard of care, discharge requirement, and disinfection guide[30]. We ensured everybody a copy of the manual and receive updates promptly. Q&A sessions were used to clarify anything in doubt. Using a WeChat group, the team was able to timely disseminate truthful and helpful scientific knowledge and, in the meantime, provide tips on who to trust and what to look out for. Special attention was paid to those who have many questions regarding the treatment. As the medical doctors did not usually have enough time to answer those questions during routine rounds due to overwhelming case load, we coordinated online and offline shelter hospital treatment Q&A sessions to invite medical specialists to provide education and answer general questions about COVID-19 and its complications treatment.

Additionally, we encouraged patients, workers and healthcare workers to read scientific books that could be downloaded online for free. We provided topics and gave recommendations. For example, “Walking in the shelter hospital” was a book we highly recommended because it was specifically written for those who temporarily reside in the shelter hospital. The book expounded the principles of psychological protection under special circumstances, including chapters on recognizing psychological symptoms, breathing relaxation skills, and indoor exercise methods.

1.3.4. Mental health knowledge acquisition of non-psychiatric healthcare workers

Recognizing the high rates of depression, anxiety, stress and burnout among frontline healthcare workers in the shelter hospital[31], the team designed a quick mental health knowledge acquisition course. The purpose was to twofold: Learn to help self and others. Specifically, the program focused on obtaining knowledge on identification of symptoms and signs of depression, anxiety, and PTSD, mindfulness and self-relaxation skills, therapeutic communication and psychological crisis intervention basics.

1.3.5. Group activities, counseling and education

Promoting group support was one of the key components of our model. Patients were given opportunities to participate in weekly scheduled activity groups of meditation, relaxation, exercise, etc. The district chief, a volunteer or a nurse was appointed as the leader of such a group. Group counseling was run by a psychological counselor and a psychiatric nurse. Each group had 8-10 patients. With appropriate protection, group members sat around a table and shared experience on fighting the COVID-19. With the intention to create a safe shelter hospital milieu, to provide mutual support of peers going through same treatment, and to emphasize recovery goal setting and accomplishing, the counselors focused on psychoeducation, instillation of hope, and free ventilation of emotions. After each session, patients chose their favorite stationery and shared notes with others who were not able to participate. During debriefing, each patient was also given a chance to record a short “speak out” video to express how they felt but dared not to speak out. It was not to our surprise that many people openly talked about the fear and anxiety about the COVID-19; some shared positive and negative life experiences in the shelter hospital.

Psychoeducation was delivered both online and in person. Medical specialists were also invited as speakers to give creditable general information about COVID-19. Patients were divided into 4 groups according to the time of hospitalization: Newly admitted, admitted > 1 week ago, preparing for discharge, and post-discharge (within 15 days). We noticed people in different stages of mild COVID-19 recovery had different psychological concerns, we provided customized education materials with special attention to the mental health risks of each group.

1.3.6. Virtualization of psychological intervention

On-site face-to-face intervention was impractical at the shelter hospital due to many obvious reasons including physical distancing requirement and the inconvenience of putting on and taking off PPE. Fortunately, today’s high technology allows virtualization of psychological intervention. The main audio-video tool used was WeChat, through which we could do video or audio-only consultation, per client’s preference. The services we provided included Q & A on live webcasts, online COVID-19 related knowledge learning, psychoeducation, online group relaxation, online Bahrain group, etc.

1.3.7. Consultation and liaison

Once a healthcare workers identified a high-risk patient and felt there was a need for specialist help, he or she would initiate a psychiatric consultation in a timely manner. The psychiatrist would do a thorough evaluation and provide treatment, including referring to a team psychologist for individual psychotherapy sessions. If the patient needed psychiatric hospitalization, a referral to a local psychiatric hospital would be sent out. During the time the authors’ team working at the Wuchang shelter hospital, one patient developed acute mania that required immediate referral to a local mental health facility, three other patients experienced moderate to severe depression that warranted pharmacologic management with anti-depressants.

2. Results

2.1. Pre-service survey

Figure 2 showed a summary of scores of these 3 rating scales and demonstrated the mental health needs of patients at the shelter hospital. Figure 2 depicted that both patients and healthcare workers in the shelter hospital reported a high level of depression and anxiety.

Figure 2. Pre-service survey results.

GAD-7: Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 items; PHQ-2: Patient Health Questionnaire-2 items; PC-PTSD-5: Primary Care PTSD screen for the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th edition.

2.2. Post-service survey

To assess the effectiveness of our approach, we conducted an anonymous WeChat survey after the shelter hospital was closed. Forty-eight subjects (46 nurses and 2 doctors) responded. The results are summarized in Table 2. Interestingly, all responders were women. Most felt that the training was very helpful in relieving own anxiety and insomnia, and also in recognizing and dealing with the patients’ anxiety and insomnia complaints. Some reported that the course helped to learn more about self-protection.

Table 2.

Feedback of training from 48 medical workers

| Characteristic | n | Practical value of training/No. | Gains from training/No. | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Very practical | More practical | A little beneficial | Very beneficial | More beneficial | ||

| Sex | ||||||

| Men | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Women | 48 | 30 | 18 | 3 | 25 | 20 |

| Education level | ||||||

| Undergraduate | 37 | 21 | 16 | 3 | 18 | 16 |

| College | 8 | 6 | 2 | 0 | 4 | 4 |

| Postgraduate | 3 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 |

| Job | ||||||

| Nurse | 46 | 28 | 18 | 3 | 23 | 20 |

| Doctor | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| Technical title | ||||||

| Junior nurse | 15 | 6 | 9 | 1 | 5 | 9 |

| Primary nurse | 5 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 1 |

| Deputy chief nurse | 5 | 3 | 2 | 0 | 3 | 2 |

| Supervisor nurse | 21 | 15 | 6 | 1 | 12 | 8 |

| Deputy chief physician | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| Characteristic | Relief of anxiety and insomnia/No. | Recognition of patients with anxiety and insomnia/No. | Dealing with patients’ anxiety and insomnia/No. | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A little helpful | Very helpful | Much helpful | A little helpful | Very helpful | Much helpful | A little helpful | Very helpful | Much helpful | |

| Sex | |||||||||

| Men | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Women | 17 | 18 | 13 | 16 | 18 | 14 | 13 | 17 | 18 |

| Education level | |||||||||

| Undergraduate | 14 | 14 | 9 | 11 | 16 | 10 | 9 | 14 | 14 |

| College | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 |

| Postgraduate | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 |

| Job | |||||||||

| Nurse | 16 | 17 | 13 | 15 | 18 | 13 | 12 | 17 | 17 |

| Doctor | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Technical title | |||||||||

| Junior nurse | 7 | 2 | 6 | 5 | 3 | 7 | 3 | 1 | 11 |

| Primary nurse | 1 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 1 |

| Deputy chief nurse | 1 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 3 |

| Supervisor nurse | 7 | 11 | 3 | 7 | 11 | 3 | 7 | 12 | 2 |

| Deputy chief physician | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

2.3. Case panel

Case 1: A gentleman who lost his wife before his admission to shelter hospital because of mild SARS-CoV-2 infection. The patient felt extremely guilty about not being able to take good care of his wife. The nursing workers noticed that he was very isolative, quiet, and minimally interactive with others. In daily rounds, he answered most questions in single words. The direct care nurse participated in our training sessions and learned active listening skills. She was able to recognize patient’s depressive symptoms and signs. She was very empathetic and compassionate, gradually built a good rapport with the patient. The patient began to talk more about his feelings and admitted to depression that was precipitated by his wife’s death. With encouragement from the nurse, he decided to seek psychiatric help. A psychological consult was formally requested. We conducted a one-on-one video psychiatric interview and assessed his safety and risk for self-harm. No pharmacologic management was considered but grief counseling was provided through video. The patient actively participated and showed improvement.

Case 2: A nurse who arrived in Wuhan on the same day when the shelter hospital opened. Not given enough time for rest, she started working immediately. She had no previous experience taking care of infectious disease patients so with overwhelming workload, she felt physically and mental exhausted every day. She started having difficulty falling and maintaining sleep. She also had severe anxiety worrying about contracting COVID-19 and transmitting it to her mother and children. Her work performance declined. She isolated herself in her room after work, had crying spells and lost interest in all activities. She initiated a request for professional psychological help. The psychiatrist did a video interview and made a diagnosis of moderate anxiety. Psychotherapy sessions were delivered through video. She learned self-regulation skills, also received audio instruction for progressive muscle relaxation and guided mindfulness therapy. She practiced these skills faithfully. Her anxiety significantly improved after several therapy sessions. She also reported sleep improvement and better energy level during working hours.

3. Discussion

The past 2 decades witnessed a gradual transformation of mental health services in China, largely guided by government policy change and law establishment. In 2005, the State Council of China issued a general contingency plan for public emergency to require provision of psychological assistance to emergency workers and casualties[32]. The 2013 Mental Health Law again emphasized the need for psychological assistance in the government emergency plans[33]. Most recently, the 2015—2020 national mental health work plan stipulated that different levels of psychological crisis intervention teams should be rapidly assembled in the case of emergencies[34]. In response to the coronavirus outbreak in China, NHC issued a guiding principle for emergency psychological crisis intervention on January 26th, 2020. The Guide classified COVID-19 affected population into 4 different groups: The front-line healthcare workers, the confirmed patients with COVID-19, the front-line management, and the logistic support workers. All 4 groups were high priority. The stipulated main psychological crisis intervention work for COVID-19 epidemic included timely identification of high-risk groups, suicide and impulsive behavior prevention, and provision of high-quality treatment, and case management to target population.

Due to very limited resources and various other reasons, providing mental health support and psychological crisis intervention to COVID-19 patients and front-line healthcare workers was an unprecedented challenge. This article described an implementable multi-component model that could be used in large-scale medical isolation place such as a shelter hospital. The model had 3 major characteristics: Organized peer support, client-centered culturally sensitive supportive care, and using front-line healthcare providers, and patients as facilitators. The model also abided some basic principles of crisis counseling including simplicity, brevity, pragmatism, immediacy, and innovation.

In a crisis, people could not afford complicated procedures. Simple psychological support had the best chance of having a positive effect. Our intervention focused on providing truthful COVID-19 knowledge, psychoeducation, basic relaxation skills, and group activities. These proved to be a simple avenue for psychological support to people in quarantine. All interventions were short, from minutes up to one hour. We also worked closely with hospital administrative to make the schedule flexible and minimize conflict with daily routines. The interventions were practical. Most of the educational materials were written in lay-person languages and were very comprehensible by majority of people. They were distributed online and could be conveniently downloaded to smartphones. Self-relaxation techniques were easy to learn and practice. All services were provided on site and right away. When specialist care was deemed to be necessary, the referral was made without any delay. The unique quarantine environment did not allow regular face-to-face psychological intervention. By use of online audio and video conference tools, we were able to provide psychoeducation, assessment, group relaxation, Bahrain group, and individual consultation. The offline in-person evaluation and treatment were initiated whenever deemed necessary. The hybrid service was well-accepted because of less worry about infection, comfort, convenience, and accessibility.

Chinese healthcare workers were usually very reluctant to receive professional psychological help, even if they admit to significant psychological stress during COVID-19[18]. In a survey of the front-line medical workers preference for psychological intervention when experiencing mental distress, more than 90% people chose self-reading psychological science books or self-adjustment (stress management skills) instead of external help (telephone hotline, online psychological counseling). In our model, healthcare workers were trained to be facilitators to help self and others. They functioned as active providers and also intermediaries in the mental health team. They learned how to screen psychological symptoms and make referrals, also grasped communication and coping skills. The approach was well-accepted in the shelter hospital probably that it was namely oriented to equip them with psychological skills to help their patients, but on the other hand, it could help them identify their own mental health symptoms and needs. In our post survey, 64.6% trainees felt that the training was much or more helpful for themselves to relieve anxiety and improve sleep quality.

Mobilizing non-mental health professionals to facilitate psychological screening or intervention has demonstrated good outcomes in previous infectious epidemics. For example, during the period of EVD outbreak in Sierra Leone, due to the lack of health workers in the whole country, region level nurse led clinics were established to provide psychosocial support in communities[35-36]. When MERS outbreak in Korea in 2015, a community based proactive intervention model was established for isolated people and families with MERS patients[37]. Our post survey showed 70.8% of healthcare workers felt learning to recognize mental health symptoms was very helpful; 72.9% considered gaining knowledge on anxiety and insomnia was extremely beneficial.

During the service, 10 patients were referred to psychiatric specialists for further evaluation and care. One noticeable advantage was that healthcare workers were not mental health professionals. The services they provided were more acceptable by patients, who commonly had stigma towards mental health care.

Psychological intervention needed to be mindful with cultures. Our model was in line with Chinese cultural background. The sense of belonging was at the emotional level of familism culture, which was a sense of security and responsibility. Family culture had a profound influence on Chinese society[38]. When people felt a sense of belonging, they were often happy and healthy[22]. Our model respected Chinese traditional family structure and used client-centered culturally sensitive supportive care that helped patients gain the sense of belonging and feel at home instead of a quarantine hospital environment. It has the following specific characteristics: 1) Interventions were tailored per client’s specific needs under specific circumstances. 2) It conceptualized the client-provider relationship as a partnership so emphasizes collaboration instead of cooperation. The psychological intervention was viewed as a “help” instead of “treatment”. Clients were given opportunities to be heard and validated. Like any supportive care, therapeutic alliance was considered as a key in our model. With client’s active involvement, customized services were provided to individuals to help alleviate symptoms, improve self-esteem, relate to the reality, and enhance the ability to cope with shelter hospital related stressors and challenges. 3) It acknowledged the role of traditions (i.e. family, customs) in health and healing. The providers respected client’s cultures and values, and incorporated those into psychological services to help build expectations and facilitate changes and improvement.

This model also has implications for policymakers including occupational health surveillance and coping strategies within psychological support and disability programs[39-41]. Furthermore, this model can be applied to shelter hospitals and community centralized isolation in different setting in worldwide if necessary. In addition, the model could provide experience for future epidemic control. Psychological training for mental health and other medical workers should be prior to deployment to infectious isolation areas. The health status of medical workers and patients need to be tracked and evaluated during the epidemic, and continued support should be provided after the epidemic.

However, our intervention model was not without limitations. The model was tried on a small sample that could not represent all shelter hospital patients. We did not have time to conduct clinical interview on every patient to rule in/out psychiatric diagnosis therefore the intervention was not diagnosis-specific. Due to the aforementioned reason and time limit, no standard care level therapy such as cognitive behavioral therapy or interpersonal psychotherapy was used in the model. There was no structured follow-up scheduled for patients after discharge to measure the short- or long-term outcome. The psychological intervention model in shelter hospital was explored by the mental health workers based on the previous experience of crisis intervention and the actual observation in a closed situation. It was carried out under the circumstance of time urgency and inadequate preparation. It should be gradually improved and verified in more population. The results were not fully validated.

In the midst of this unprecedented COVID-19 pandemic, to meet the huge mental health demand in a large shelter hospital, our psychological intervention was proven to be feasible, acceptable, and associated with positive outcomes. Future tastings of this model in larger population and different settings are warranted.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to all the participants in the survey.

Http://xbyxb.csu.edu.cn

《中南大学学报(医学版)》编辑部

Funding Statement

This work was supported by the Special Project for the Construction of Innovative Provinces in Hunan Province (2020SK3003), China.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

AUTHORS’CONTRIBUTIONS

ZHANG Li Wrote and revised the manuscript; LI Lingjiang, WANG Xiaoping, TAN Liwen, and ZHANG Yan Conceived the article; ZHENG Wanhong and LI Weihui Conceived and made multiple revisions of the manuscript; GAO Xueping, CHEN Qiongni, XU Junmei, TANG Juanjuan, LUO Xingwei, CHEN Xudong, ZHANG Xiaocui, HE Li, TIAN Yi, and WEN Chuan Worked in the shelter hospital, conducted the pre-interview survey as well as collected the cases. CHENG Peng, XU Lizhi, and LIU Jin Made the statistical analysis. All authors endorsed the final manuscript.

Note

http://xbyxb.csu.edu.cn/xbwk/fileup/PDF/20230192.pdf

References

- 1. Sohrabi C, Alsafi Z, O'Neill N, et al. World Health Organization declares global emergency: a review of the 2019 novel coronavirus (COVID-19)[J]. Int J Surg, 2020, 76: 71-76. 10.1016/j.ijsu.2020.02.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Liu YC, Kuo RL, Shih SR. COVID-19: the first documented coronavirus pandemic in history[J]. Biomed J, 2020, 43(4): 328-333. 10.1016/j.bj.2020.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Wang HH, Li XM, Li T, et al. The genetic sequence, origin, and diagnosis of SARS-CoV-2[J]. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis, 2020, 39(9): 1629-1635. 10.1007/s10096-020-03899-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Schwartz DA, Graham AL. Potential maternal and infant outcomes from (Wuhan) coronavirus 2019-nCoV infecting pregnant women: lessons from SARS, MERS, and other human coronavirus infections[J]. Viruses, 2020, 12(2): 194. 10.3390/v12020194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Zhu WH, Wang Y, Xiao K, et al. Establishing and managing a temporary coronavirus disease 2019 specialty hospital in Wuhan, China[J]. Anesthesiology, 2020, 132(6): 1339-1345. 10.1097/ALN.0000000000003299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Yu P, Zhu J, Zhang ZD, et al. A familial cluster of infection associated with the 2019 novel coronavirus indicating possible person-to-person transmission during the incubation period[J]. J Infect Dis, 2020, 221(11): 1757-1761. 10.1093/infdis/jiaa077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Chen SM, Zhang ZJ, Yang JT, et al. Fangcang shelter hospitals: a novel concept for responding to public health emergencies[J]. Lancet, 2020, 395(10232): 1305-1314. 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30744-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Peng FJ, Tu L, Yang YS, et al. Management and treatment of COVID-19: the Chinese experience[J]. Can J Cardiol, 2020, 36(6): 915-930. 10.1016/j.cjca.2020.04.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hata T. The comprehensive role of general physicians is very important in the chronic phase of a disaster area: beyond and after the Great East Japan Earthquake[J]. J Gen Fam Med, 2017, 18(5): 212-216. 10.1002/jgf2.65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Paladino L, Sharpe RP, Galwankar SC, et al. Reflections on the Ebola public health emergency of international concern, part 2: the unseen epidemic of posttraumatic stress among health-care personnel and survivors of the 2014-2016 Ebola outbreak[J]. J Glob Infect Dis, 2017, 9(2): 45-50. 10.4103/jgid.jgid_24_17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. 佚名. 美国纽约的“方舱”医院[EB/OL]. 凤凰网(2020-03-29)[2021-12-01]. https://news.ifeng.com/c/7vEIDpRqoLo#p=1. ; Anon . “Square Cabin” Hospital in New York, USA[EB/OL]. IFENG(2020-03-29)[2021-12-01]. https://news.ifeng.com/c/7vEIDpRqoLo#p=1.

- 12. 梁敉宁, 陈琼妮, 李亚敏, 等. 湖南省4 237名护士焦虑、抑郁、失眠现状及影响因素[J]. 中南大学学报(医学版), 2021, 46(8): 822-830. 10.11817/j.issn.1672-7347.2021.210212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; LIANG Mining, CHEN Qiongni, LI Yamin, et al. Status quo and influencing factors for anxiety, depression, and insomnia among 4237 nurses in Hunan Province[J]. Journal of Central South University. Medical Science, 2021, 46(8): 822-830. 10.11817/j.issn.1672-7347.2021.210212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Wu P, Fang YY, Guan ZQ, et al. The psychological impact of the SARS epidemic on hospital employees in China: exposure, risk perception, and altruistic acceptance of risk[J]. Can J Psychiatry, 2009, 54(5): 302-311. 10.1177/070674370905400504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hall RCW, Hall RCW, Chapman MJ. The 1995 Kikwit Ebola outbreak: lessons hospitals and physicians can apply to future viral epidemics[J]. Gen Hosp Psychiatry, 2008, 30(5): 446-452. 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2008.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Park HY, Park WB, Lee SH, et al. Posttraumatic stress disorder and depression of survivors 12 months after the outbreak of Middle East respiratory syndrome in South Korea[J]. BMC Public Health, 2020, 20(1): 605. 10.1186/s12889-020-08726-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. 丛中, 吕秋云, 阎俊, 等. SARS病人及相关人群的心理特征与心理干预[J]. 北京大学学报(医学版), 2003, (S1): 47-50. 10.19723/j.issn.1671-167x.2003.s1.019. [DOI] [PubMed]; CONG Zhong, Qiuyun LÜ, YAN Jun, et al. Mental stress and crisis intervention in the patients with SARS and the people related[J]. Journal of Peking University. Health Science, 2003, (S1): 47-50. 10.19723/j.issn.1671-167x.2003.s1.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ng SM, Chan TH, Chan CL, et al. Group debriefing for people with chronic diseases during the SARS pandemic: strength-focused and meaning-oriented approach for resilience and transformation (SMART)[J]. Community Ment Health J, 2006, 42(1): 53-63. 10.1007/s10597-005-9002-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Chen QN, Liang MN, Li YM, et al. Mental health care for medical staff in China during the COVID-19 outbreak[J]. Lancet Psychiatry, 2020, 7(4): e15-e16[2021-10-25]. 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30078-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Mossman SA, Luft MJ, Schroeder HK, et al. The Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7-item scale in adolescents with generalized anxiety disorder: signal detection and validation[J]. Ann Clin Psychiatry, 2017, 29(4): 227-234A. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Arrieta J, Aguerrebere M, Raviola G, et al. Validity and utility of the patient health questionnaire (PHQ)-2 and PHQ-9 for screening and diagnosis of depression in rural Chiapas, Mexico: A cross-sectional study[J]. J Clin Psychol, 2017, 73(9): 1076-1090. 10.1002/jclp.22390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Prins A, Bovin MJ, Smolenski DJ, et al. The primary care PTSD screen for DSM-5 (PC-PTSD-5): development and evaluation within a veteran primary care sample[J]. J Gen Intern Med, 2016, 31(10): 1206-1211. 10.1007/s11606-016-3703-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Liu DY, Yu XB, Wang YC, et al. The impact of perception of discrimination and sense of belonging on the loneliness of the children of Chinese migrant workers: a structural equation modeling analysis[J]. Int J Ment Health Syst, 2014, 8: 52. 10.1186/1752-4458-8-52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Guo M, Li SJ, Liu JY, et al. Family relations, social connections, and mental health among Latino and Asian older adults[J]. Res Aging, 2015, 37(2): 123-147. 10.1177/0164027514523298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Cheng Y, Zhang LY, Wang F, et al. The effects of family structure and function on mental health during China’s transition: a cross-sectional analysis[J]. BMC Fam Pract, 2017, 18(1): 59. 10.1186/s12875-017-0630-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Xiang YT, Yang Y, Li W, et al. Timely mental health care for the 2019 novel coronavirus outbreak is urgently needed[J]. Lancet Psychiatry, 2020, 7(3): 228-229. 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30046-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Bakare WA, Stephen Ilesanmi O, Nabena EP, et al. Psychosocial stressors and support needs of survivors of Ebola virus disease, Bombali District, Sierra Leone, 2015[J]. Healthc Low Resour Settings, 2016, 3(2): 48-51. 10.4081/hls.2015.5411. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Siu JYM. Coping with future epidemics: Tai Chi practice as an overcoming strategy used by survivors of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) in post-SARS Hong Kong[J]. Health Expect, 2016, 19(3): 762-772. 10.1111/hex.12270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Magnavita N, Chirico F, Garbarino S, et al. SARS/MERS/SARS-CoV-2 outbreaks and burnout syndrome among healthcare workers. an umbrella systematic review[J]. Int J Environ Res Public Health, 2021, 18(8): 4361. 10.3390/ijerph18084361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Chirico F, Ferrari G, Nucera G, et al. Prevalence of anxiety, depression, burnout syndrome, and mental health disorders among healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: A rapid umbrella review of systematic reviews[J]. J Health Soc Sci, 2021, 6(2): 209-220. 10.19204/2021/prvl7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30. 国家卫生健康委医政医管局,国家卫生健康委医疗管理服务指导中心 . 方舱医院患者手册(第三版)[M/OL]. [2020-10-25]. http://www.360doc.cn/mip/894212596.html. [Google Scholar]; Medical Administration of the National Health Commission of China, Medical Management Service Guidance Center of the National Health Commission . Patient handbook for cabin hospitals(3th edition)[M/OL]. [2020-10-25]. http://www.360doc.cn/mip/894212596.html. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Lai JB, Ma SM, Wang Y, et al. Factors associated with mental health outcomes among health care workers exposed to coronavirus disease 2019[J]. JAMA Netw Open, 2020, 3(3): e203976 [2021-10-25]. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.3976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. 中华人民共和国中央人民政府 . 国家突发公共事件总体应急预案[EB/OL]. (2006-02-20) [2020-03-20]. https://www.mem.gov.cn/xw/jyll/200602/t20060220_230269.shtml. ; The Central People’s Government of People’s Republic of China . National General Emergency Plan for Public Emergencies[EB/OL]. (2006-02-20) [2020-03-20]. https://www.mem.gov.cn/xw/jyll/200602/t20060220_230269.shtml.

- 33. Chen H, Phillips M, Cheng H, et al. Mental Health Law of the People’s Republic of China (English translation with annotations): Translated and annotated version of China’s new Mental Health Law[J]. Shanghai Arch Psychiatry, 2012, 24(6): 305-321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. 卫生计生委, 中央综治办, 发展改革委, 等. 全国精神卫生工作规划(2015——2020年)[EB/OL]. (2015-06-18) [2020-03-25]. http://www.rmzxb.com.cn/c/2015-06-18/519945.shtml. [Google Scholar]; National Health and Family Planning Commission of China, Office of the Central Committee for Comprehensive Management of Public Security, National Development and Reform Commission, et al . National Mental Health Work Plan (2015—2020)[EB/OL]. (2015-06-18) [2020-03-25]. http://www.rmzxb.com.cn/c/2015-06-18/519945.shtml. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Kamara S, Walder A, Duncan J, et al. Mental health care during the Ebola virus disease outbreak in Sierra Leone[J]. Bull World Health Organ, 2017, 95(12): 842-847. 10.2471/BLT.16.190470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Hughes P. Mental illness and health in Sierra Leone affected by Ebola[J]. Intervention, 2015, 13(1): 60-69. 10.1097/wtf.0000000000000082. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Yoon MK, Kim SY, Ko HS, et al. System effectiveness of detection, brief intervention and refer to treatment for the people with post-traumatic emotional distress by MERS: a case report of community-based proactive intervention in South Korea[J]. Int J Ment Health Syst, 2016, 10: 51. 10.1186/s13033-016-0083-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Zhang YD, Jia XM. A qualitative study on the grief of people who lose their only child: from the perspective of familism culture[J]. Front Psychol, 2018, 9: 869. 10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Chirico F, Magnavita N. The crucial role of occupational health surveillance for health-care workers during the COVID-19 pandemic[J]. Workplace Health Saf, 2021, 69(1): 5-6. 10.1177/2165079920950161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Chirico F. Spirituality to cope with COVID-19 pandemic, climate change and future global challenges[J]. J Health Soc Sci, 2021, 6(2): 151-158. 10.19204/2021/sprt2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Chirico F, Ferrari G. Role of the workplace in implementing mental health interventions for high-risk groups among the working age population after the COVID-19 pandemic[J]. J Health Soc Sci, 2021, 6(2): 145-150. 10.19204/2021/rlft1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]