Abstract

目的

慢性肾脏病(chronic kidney disease,CKD)已日益成为全球重要的公共卫生问题。心血管事件的发生是CKD患者的主要死因,而动脉硬化是心血管疾病发生和发展的重要病理生理基础。肱踝脉搏波传导速度(brachial-ankle pulse wave velocity,baPWV)和踝臂指数(ankle-brachial index,ABI)是临床上常用的反映早期动脉硬化的重要指标。在健康人群、高血压病及糖尿病人群中,半胱氨酸蛋白酶抑制剂C(cystatin C,Cys C)和同型半胱氨酸(homocysteine,Hcy)均与动脉硬化密切相关,而在CKD患者中,Hcy、Cys C与动脉硬化的相关研究报道甚少。本研究旨在探讨CKD患者体内Cys C、Hcy水平与动脉硬化指标的关系。

方法

选择2019年6月至2020年6月在中南大学湘雅三医院健康管理中心进行健康体检并符合CKD诊断标准的611名个体作为研究对象。测量并记录受试者的身高、体重、收缩压(systolic pressure,SBP)、舒张压(diastolic pressure,DBP)等,并计算体重指数(body mass index,BMI)。抽取受试者血液样本5 mL并检测Cys C、Hcy、空腹血糖(fasting blood glucose,FBG)、总胆固醇(total cholesterol,TC)、血肌酐(serum creatinine,SCr)等指标。留取受试者尿液,检测尿微量白蛋白、尿肌酐,并计算尿微量白蛋白与尿肌酐比值(albumin/creatinine ratio,UACR)。采用全自动动脉硬化检测仪测定baPWV、ABI。以受试者血中Cys C和Hcy水平的四分位数分组,并比较各组间baPWV和ABI异常的比例。采用Pearson相关分析Cys C、Hcy与baPWV的相关性;采用单因素及多因素logistic回归分析Cys C、Hcy对ABI、baPWV的影响。

结果

在611例CKD患者中,435例(71.19%)baPWV异常,48例(7.86%)ABI异常。随着Cys C和Hcy水平的升高,baPWV及ABI异常的比例也逐渐增加。baPWV与Cys C(r=0.32)、Hcy(r=0.20)均呈正相关(均P<0.01)。在校正性别、BMI、FBG等混杂因素后,Cys C(OR=6.54,95% CI:1.93~22.14,P<0.01)及Hcy(OR=1.08,95% CI:1.01~1.16,P=0.02)是baPWV异常的独立危险因素。在校正年龄、性别、BMI、FBG等混杂因素后,Cys C(OR=9.95,95% CI:2.84~34.92,P<0.01)及Hcy(OR=1.06,95% CI:1.01~1.11,P=0.02)是ABI异常的独立危险因素。

结论

在CKD患者中,动脉硬化指标baPWV、ABI与体内Cys C和Hcy水平显著相关。检测Cys C及Hcy的水平有助于对CKD患者动脉硬化的早期诊断。

Keywords: 动脉硬化, 半胱氨酸蛋白酶抑制剂, 同型半胱氨酸, 肱踝脉搏波传导速度, 踝臂指数, 慢性肾脏病

Abstract

Objective

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) has become an important public health problem in the world. The occurrence of cardiovascular events is the main cause of death in patients with CKD, and arteriosclerosis is an important pathophysiological basis for cardiovascular diseases. Nowadays, brachial-ankle pulse wave velocity (baPWV) and ankle-brachial index (ABI) are clinically important indicators to reflect early atherosclerosis. Cystatin C (Cys C)and homocysteine (Hcy) are related to arteriosclerosis in healthy, hypertensive, and diabetic people, while there are few studies on the correlation among Hcy, CysC and arteriosclerosis in patients with CKD. This study aims to investigate the relationship between Cys C, Hcy and atherosclerosis in patients with CKD.

Methods

A total of 611 individuals, who met the diagnostic criteria for CKD and underwent physical examination in the Health Management Center of Third Xiangya Hospital, Central South University from June 2019 to June 2020, were selected as the research subjects. Height, weight, systolic blood pressure (SBP), and diastolic blood pressure (DBP) were measured and recorded, and body mass index (BMI) was calculated. Blood samples (5 mL) were collected and Cys C, Hcy, fasting blood glucose (FBG), total cholesterol (TC), serum creatinine (SCr), and other blood indexes were tested. Urine was collected to detect microalbumin and creatinine, and the albumin/creatinine ratio (UACR) was calculated. baPWV and ABI were measured by automatic arteriosclerosis detector. The quartiles of Cys C and Hcy were divided into groups, and the proportion of baPWV and ABI abnormalities among groups was compared pairwise. The correlation between Cys C, Hcy, and baPWV was analyzed by Pearson correlation analysis. Univariate and multivariate logistic regression were used to analyze the effects of Cys C and Hcy on ABI and baPWV.

Results

Among 611 patients with CKD, 435 (71.19%) had abnormal baPWV and 48 (7.86%) had abnormal ABI. With the increase of Cys C and Hcy levels, the proportion of baPWV and ABI abnormalities were gradually increased. BaPWV was positively correlated with Cys C (r=0.32) and Hcy (r=0.20). After adjusting for confounding factors such as gender, BMI, and FBG, Cys C (OR=6.54, 95% CI 1.93 to 22.14, P<0.01) and Hcy (OR=1.08, 95% CI 1.01 to 1.16, P=0.02) were independent risk factors for abnormal baPWV. Also, after adjusting for confounding factors such as age, sex, BMI, and FBG, Cys C (OR=9.95, 95% CI 2.84 to 34.92, P<0.01) and Hcy (OR=1.06, 95% CI 1.01 to 1.11, P=0.02) were independent risk factors for abnormal ABI.

Conclusion

In patients with CKD, baPWV and ABI are significantly correlated with Cys C and Hcy levels. Detection of Cys C and Hcy levels is helpful for the early diagnosis of arteriosclerosis.

Keywords: arteriosclerosis, cystatin C, homocysteine, brachial-ankle pulse wave velocity, ankle-brachial index, chronic kidney disease

慢性肾脏病(chronic kidney disease,CKD)的患病率逐年上升,中国CKD的患病率高达10.8%[1],欧洲为3.31%~17.3%[2]。CKD患者主要的死因是心血管疾病[3-4],因此早期诊断心血管疾病对于改善CKD患者的预后至关重要。动脉硬化是心血管疾病发生的重要危险因素,目前临床有许多评估动脉硬化的无创性检查,其中肱踝脉搏波传导速度(brachial-ankle pulse wave velocity,baPWV)和踝臂指数(ankle-brachial index,ABI)均被证明是预测心血管疾病发生的重要指标[5-8]。

与血肌酐(serum creatinine,SCr)相比,半胱氨酸蛋白酶抑制剂C(cystatin C,Cys C)是一项能更好地反映早期肾功能损伤的敏感的内源性标志物[9-10]。Cys C的水平与动脉硬化关系密切[11-12]。同型半胱氨酸(homocysteine,Hcy)是一种含硫基氨基酸,在细胞代谢中起重要作用。研究[13-14]表明Hcy的升高是动脉硬化的危险因素。然而,目前国内外对于CKD患者血清Cys C、Hcy与动脉硬化关系的研究尚少。因此,本研究旨在探讨CKD患者中Cys C及Hcy与动脉硬化指标之间的相关性,从而为CKD患者心血管事件的防治提供临床依据。

1. 对象与方法

1.1. 对象

选取2019年6月至2020年6月在中南大学湘雅三医院健康管理中心进行健康体检的人群为研究对象。入选标准:1)年龄≥18岁且有本研究所需要的全部数据者;2)CKD患者,即满足尿微量白蛋白与尿肌酐比值(albumin/creatinine ratio,UACR)≥30 mg/g和/或估算的肾小球滤过率(estimated glomerular filtration rate,eGFR)<60 mL/(min·1.73 m2)[15]者。排除严重心功能不全、急性冠脉综合征、先天性心脏病、心肌病、肺源性心脏病、严重心律失常、脑卒中、脑梗死、外周血管疾病、急性肾功能不全、肝功能衰竭、急性或慢性感染性疾病、肿瘤、妊娠等患者。

1.2. 分组

分别以血中Cys C和Hcy水平的四分位数分组:Cys C≤0.61 mg/L(QC1组),0.62~0.72 mg/L(QC2组),0.73~0.85 mg/L(QC3组),≥0.86 mg/L(QC4组);Hcy≤11.50 μmol/L(QH1组),11.60~13.50 μmol/L(QH2组),13.60~15.90 μmol/L(QH3组),≥16.00 μmol/L(QH4组)。

1.3. 方法

1.3.1. 问卷调查

采用统一设计的健康体检自测问卷调查表,由已通过专门培训的人员作为问卷调查员。问卷调查表内容包括受试者的基本信息、家族史、既往史(高血压病史、糖尿病史、心血管疾病史等)、用药史等。

1.3.2. 体格检查

由专业人员分别测量并记录受试者的身高、体重、收缩压(systolic blood pressure,SBP)、舒张压(diastolic blood pressure,DBP)等,并计算体重指数(body mass index,BMI)。血压测量按照2017年ACC/ANA高血压指南[16]推荐的方法。

1.3.3. 实验室检查

受试者均需空腹8 h以上,抽取其血液样本 5 mL。血液检测指标包括:Cys C、Hcy、空腹血糖(fasting blood glucose,FBG)、总胆固醇(total cholesterol,TC)、三酰甘油(triglyceride,TG)、低密度脂蛋白胆固醇(low-density lipoprotein cholesterol,LDL-C)、高密度脂蛋白胆固醇(high-density lipoprotein cholesterol,HDL-C)、SCr、尿酸(uric acid,UA)、血尿素氮(blood urea nitrogen,BUN)等。留取受试者(月经期妇女除外)尿液,检测尿微量白蛋白、尿肌酐,并计算UACR。

1.3.4. baPWV和ABI的检测

采用全自动动脉硬化检测仪测定baPWV和ABI。检查前受试者需静卧休息5 min,操作时处于仰卧位,将4个标准袖带分别缚于受试者双侧上臂肱动脉和下肢脚踝处的后胫动脉处,心音采集装置置于胸骨左缘第4肋间,心电图电极夹于左右手腕内侧,待心电图和心音图稳定后,记录受试者的baPWV和ABI,每位受试者均重复测量2次,取2次数据的平均值作为最终结果。采用左、右两侧baPWV中的较大值进行分析,将baPWV≥1 400 mm/s作为baPWV异常的标准。以左、右任意一侧ABI<0.9或≥1.3作为ABI异常的标准。

1.4. 统计学处理

采用SPSS 25.0软件进行统计学分析。计量资料以均数±标准差( ±s)描述,两组间比较采用两独立样本t检验,多组间比较采用单因素方差分析。计数资料采用例(%)表示,组间比较采用χ2检验。采用Pearson相关分析Cys C、Hcy水平与baPWV的相关性;采用单因素及多因素logistic回归分析Cys C、Hcy对baPWV、ABI的影响,结果以比值比(OR)和95% CI表示。以P<0.05为差异有统计学意义。

2. 结 果

2.1. 受试者的人口学及临床特征

共纳入611名研究对象,其中男356人,年龄为19~82(51.94±10.56)岁;女255人,年龄为18~87(54.05±10.03)岁。男性患者比例、年龄、SBP、BUN、SCr、尿酸和UACR均随Cys C水平的升高而增加,eGFR随Cys C水平的升高而降低(表1)。男性患者比例、SBP、DBP、SCr、尿酸和UACR均随Hcy水平的升高而增加,HDL、eGFR随Hcy水平的升高而降低(表2)。

表1.

不同Cys C水平组间的一般资料的比较(n=611)

Table 1 Comparison of basic data between groups with different levels of Cys C (n=611)

| 组别 | n | 年龄/岁 | 男/[例(%)] |

BMI/ (kg·m-2) |

SBP/mmHg | DBP/mmHg | LDL/(mmol·L-1) | HDL/(mmol·L-1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| QC1 | 159 | 47.67±8.64 | 76(47.80) | 25.34±3.51 | 128.05±19.22 | 79.41±12.68 | 2.74±0.88 | 1.32±0.28 |

| QC2 | 155 | 51.86±9.85* | 79(50.97) | 25.63±3.52 | 132.65±18.64 | 82.03±12.52 | 2.87±0.92 | 1.35±0.31 |

| QC3 | 145 | 54.09±9.80* | 93(64.14)*† | 25.32±3.06 | 138.05±17.97* | 84.69±13.81* | 2.68±0.87 | 1.30±0.31 |

| QC4 | 152 | 57.97±10.48*†‡ | 108(71.05)*† | 25.56±3.74 | 140.97±21.28*† | 83.98±13.95* | 2.87±0.83 | 1.30±0.29 |

| 组别 |

TC/ (mmol·L-1) |

TG/ (mmol·L-1) |

FBG/ (mmol·L-1) |

BUN/ (mmol·L-1) |

SCr/ (μmol·L-1) |

UA/ (μmol·L-1) |

UACR/ (mg·g-1) |

eGFR/[mL·min-1·1.73 m-2)] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| QC1 | 5.27±1.16 | 3.01±4.48 | 5.53±2.93 | 4.75±1.19 | 61.99±12.37 | 324.78±92.27 | 78.03±8.99 | 114.45±21.92 |

| QC2 | 5.31±1.03 | 2.66±3.06 | 6.22±2.13 | 4.89±1.16 | 68.49±15.61 | 341.48±91.61 | 80.81±10.13 | 102.23±21.38* |

| QC3 | 5.22±0.94 | 2.40±1.98 | 6.17±1.89 | 5.36±1.38* | 75.64±18.29* | 363.84±88.93* | 87.08±19.13 | 94.50±20.45*† |

| QC4 | 5.26±1.23 | 2.21±2.33 | 6.16±1.57 | 6.40±2.61*†‡ | 104.47±61.71*†‡ | 386.48±93.72*† | 139.61±22.48* | 76.26±29.12*†‡ |

与QC1组比较,*P<0.05;与QC2组比较,†P<0.05;与QC3组比较,‡P<0.05。1 mmHg=0.133 kPa。

表2.

不同Hcy水平组间的一般资料的比较(n=611)

Table 2 Comparison of basic data between groups with different levels of Hcy (n=611)

| 组别 | n | 年龄/岁 | 男/[例(%)] | BMI/(kg·m-2) | SBP/mmHg | DBP/mmHg | LDL/(mmol·L-1) |

HDL/ (mmol·L-1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| QH1 | 153 | 49.75±8.98 | 30(19.61) | 24.69±3.28 | 129.22±19.50 | 79.05±12.15 | 2.91±0.80 | 1.39±0.28 |

| QH2 | 153 | 53.18±10.51* | 83(54.25)* | 25.66±3.73 | 134.89±20.27 | 81.88±13.73 | 2.86±0.86 | 1.31±0.28 |

| QH3 | 157 | 52.01±9.95 | 117(74.52)*† | 25.96±3.27* | 135.47±18.81* | 83.52±12.73* | 2.71±0.93 | 1.20±0.28*† |

| QH4 | 148 | 56.49±10.38*†‡ | 126(85.14)*†‡ | 25.54±3.48 | 139.75±19.88* | 85.48±14.11* | 2.68±0.90 | 1.21±0.27*† |

| 组别 |

TC/ (mmol·L-1) |

TG/ (mmol·L-1) |

FBG/(mmol·L-1) |

BUN/ (mmol·L-1) |

SCr/(μmol·L-1) | UA/(μmol·L-1) | UACR/(mg·g-1) | eGFR/[mL·min-1·1.73m-2)] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| QH1 | 5.25±0.91 | 1.85±1.61 | 5.72±1.33 | 4.57±1.04 | 58.48±11.19 | 302.06±72.85 | 78.84±11.66 | 111.01±20.21 |

| QH2 | 5.34±1.19 | 2.49±2.96 | 6.49±2.45 | 5.26±1.24* | 68.15±14.84* | 343.04±82.35* | 89.41±17.82 | 103.04±21.44* |

| QH3 | 5.32±1.30 | 3.34±4.25*† | 6.67±2.73* | 5.21±1.24* | 77.13±19.03*† | 374.16±91.23*† | 84.53±12.47 | 97.09±24.98* |

| QH4 | 5.05±0.95 | 2.64±3.03* | 6.22±1.91 | 6.39±2.74*†‡ | 107.31±60.72*†‡ | 396.87±102.16*† | 133.09±21.74*† | 76.36±29.31*†‡ |

与QH1组比较,*P<0.05;与QH2组比较,†P<0.05;与QH3组比较,‡P<0.05。1 mmHg=0.133 kPa。

2.2. Cys C及Hcy水平与动脉硬化指标的相关性

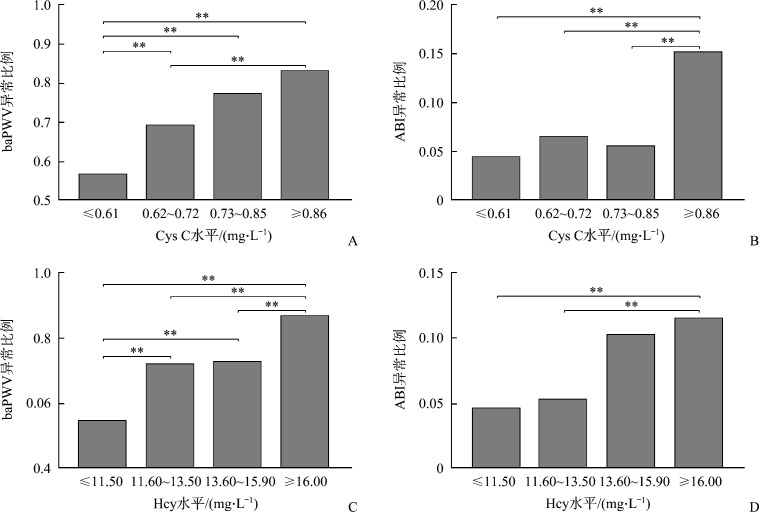

在611例CKD患者中,435例(71.19%)baPWV异常,48例(7.86%)ABI异常。以血中Cys C和Hcy水平的四分位数分组,并进行各组间的baPWV和ABI异常比例的两两比较,结果表明:随着Cys C和Hcy水平的升高,baPWV及ABI异常的比例也逐渐增加(图1)。进一步以baPWV作为因变量,Cys C和Hcy分别作为自变量进行Pearson相关分析,结果表明baPWV与Cys C(r=0.32)、Hcy(r=0.20)均呈正相关(均P<0.01,表3)。

图1.

不同胱抑素C、同型半胱氨酸水平受试者baPWV和ABI异常比例

Figure 1 Comparison of proportion of abnormal baPWV and ABI under different levels of Cys C and Hcy in subjects

A: Proportion of baPWV abnormality in different levels of Cys C; B: Proportion of ABI abnormality in different levels of Cys C; C: Proportion of baPWV abnormality in different levels of Hcy; D: Proportion of ABI abnormality in different levels of Hcy. **P<0.01.

表3.

baPWV与人口学资料及肾损伤分子、肾功能、血脂及血糖指标的相关性分析

Table 3 Correlation analysis of baPWV with index of demographic data, renal damage molecules, renal function, blood lipid and blood glucose

| 指标 | r | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 人口学资料 | 年龄 | 0.54 | <0.01 |

| BMI | 0.01 | 0.73 | |

| SBP | 0.62 | <0.01 | |

| DBP | 0.40 | <0.01 | |

| 肾损伤分子 | Cys C | 0.32 | <0.01 |

| Hcy | 0.20 | <0.01 | |

| 肾功能 | BUN | 0.25 | <0.01 |

| SCr | 0.24 | <0.01 | |

| UA | 0.11 | <0.01 | |

| eGFR | -0.27 | <0.01 | |

| 血脂 | TC | 0.03 | 0.48 |

| TG | 0.04 | 0.39 | |

| LDL | -0.01 | 0.95 | |

| HDL | -0.02 | 0.57 | |

| 血糖 | FBG | 0.15 | <0.01 |

2.3. baPWV与人口学及其他生化指标的相关性

以baPWV作为因变量,年龄、BMI、SBP、DBP、BUN、SCr、UA、eGFR、TC、TG、LDL、HDL、FBG分别作为自变量进行Pearson相关分析,结果表明:baPWV与年龄、SBP、DBP、BUN、SCr、UA和FBG均呈正相关(均P<0.01),与eGFR (r=-0.27)呈负相关(P<0.01,表3)。

2.4. baPWV异常、ABI异常的独立危险因素

Cys C(OR=13.68,95% CI:4.89~38.28,P<0.01)和Hcy(OR=1.16,95% CI:1.09~1.23,P<0.01)均是baPWV异常的危险因素;在校正性别、BMI、BUN、UA、eGFR、TG、TC、LDL、HDL、FBG等混杂因素后,Cys C(OR=6.54,95% CI:1.93~22.14,P<0.01)及Hcy(OR=1.08,95% CI:1.01~1.16,P=0.02)是baPWV异常的独立危险因素(表4)。

表4.

Cys C、Hcy与动脉硬化指标的单因素及多因素logistic回归分析

Table 4 Univariate and multivariate logistic regression analysis of Cys C, Hcy and arteriosclerosis indicators

| 模型 | baPWV异常 | ABI异常 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR(95% CI) | P | OR(95% CI) | P | |

| Cys C | ||||

| 模型1 | 13.68(4.89, 38.28) | <0.01 | 3.40(1.80, 6.42) | <0.01 |

| 模型2 | 6.54(1.93, 22.14) | <0.01 | ||

| 模型3 | 9.95(2.84, 34.92) | <0.01 | ||

| Hcy | ||||

| 模型1 | 1.16(1.09, 1.23) | <0.01 | 1.07(1.03, 1.11) | <0.01 |

| 模型2 | 1.08(1.01, 1.16) | 0.02 | ||

| 模型3 | 1.06(1.01, 1.11) | 0.02 | ||

模型1:未经校正;模型2:校正性别、BMI、BUN、UA、eGFR、TG、TC、LDL、HDL、FBG混杂因素后;模型3:校正年龄、性别、BMI、BUN、UA、eGFR、TG、TC、LDL、HDL、FBG混杂因素后。

Cys C(OR=3.40,95% CI:1.80~6.42,P<0.01)和Hcy(OR=1.07,95% CI:1.03~1.11,P<0.01)均是ABI异常的危险因素;在校正年龄、性别、BMI、BUN、UA、eGFR、TG、TC、LDL、HDL、FBG等混杂因素后,Cys C(OR=9.95,95% CI:2.84~34.92,P<0.01)及Hcy(OR=1.06,95% CI:1.01~1.11,P=0.02)是ABI异常的独立危险因素(表4)。

3. 讨 论

CKD现已日益成为严重的公共卫生问题[17]。既往有研究[18]表明心血管事件的发生是CKD患者最重要的死亡原因,动脉硬化是心血管疾病发生和发展的重要病理生理基础[19-20],因此,在CKD患者中早期识别动脉硬化的危险因素对于预防心血管事件的发生至关重要。baPWV和ABI作为目前临床常用的无创血管功能的检测方法,具有操作简单、可重复性等优点,被认为是早期动脉硬化的重要指标。一项在748名中国健康人群中的研究[21]表明Cys C与baPWV呈明显的正相关。Wang等[22]对220名研究对象的一项前瞻性研究显示Hcy的增高可能会增加发生动脉硬化的风险。既往多数研究[21-24]已证明在健康人群、高血压及糖尿病人群中,Hcy、CysC与动脉硬化密切相关,而在CKD患者中Hcy、CysC与动脉硬化的相关研究报道甚少。

本研究通过对611名CKD患者的横断面研究,结果表明性别、年龄、血压、肾功能指标与Cys C及Hcy水平相关,且随着Cys C及Hcy水平升高而增加,而eGFR随Cys C、Hcy水平的升高而降低,说明Cys C、Hcy水平可能可以作为临床评估肾功能损伤程度的良好指标。而且确有研究[25-26]发现与SCr、BUN等传统的肾功能指标相比,Cys C的敏感性和特异性更强,与肾功能下降的相关性也更加显著。Hcy也被证明是影响肾脏疾病发生和进展的主要生物化学因素。Kundi等[27]对390名2型糖尿病患者进行研究,结果发现Hcy水平与SCr水平呈正相关。一项在5 917名中老年患者中进行的前瞻性队列研究[28]表明高Hcy水平是eGFR下降的危险因素。

本研究以baPWV作为因变量,年龄、BMI、SBP、DBP分别作为自变量进行Pearson相关分析,结果表明baPWV与年龄、SBP、DBP呈正相关,提示CKD患者的年龄、血压是影响动脉硬化的重要因素。本研究发现baPWV与BUN、SCr呈明显的正相关,与eGFR呈显著的负相关,说明肾功能下降与动脉硬化存在显著的关系,既往许多研究[29-30]也证明了这一点。van Varik等[29]的研究结果也表明动脉硬化和eGFR之间存在关联,这种联系在CKD后期表现得更加明显,在肾损害的发展中起直接作用。

本研究结果显示:CKD患者baPWV异常所占的比例为71.19%,ABI异常所占的比例为7.86%,且随着Cys C和Hcy水平的升高,baPWV及ABI异常的比例也逐渐升高。Pearson相关分析的结果表明baPWV与Cys C、Hcy均呈正相关。同时,通过单因素及多因素logistic回归分析,校正性别、BMI、BUN、UA、eGFR、TG、TC、LDL、HDL、FBG等混杂因素后,结果显示Cys C及Hcy是baPWV异常的独立危险因素。上述结果表明在CKD患者中,普遍存在动脉硬化,且随着Cys C及Hcy水平的升高,动脉硬化发生的风险逐渐上升。Cys C和Hcy水平的升高与肾功能下降密切相关,而动脉硬化又与肾功能下降呈正相关,这也部分解释了在CKD患者中,Cys C和Hcy的水平与动脉硬化之间的关系。

此外,CKD患者Cys C和Hcy水平的升高本身也会导致动脉硬化。Cys C在体内主要的生理作用是抑制半胱氨酸蛋白酶,参与组织内肽类以及蛋白质(包括胶原蛋白)的代谢,保持细胞外基质的动态平衡,当体内Cys C水平和组织蛋白酶活性失衡时,会导致胶原分解、弹性纤维断裂、细胞外基质重塑及血管壁重构,进而促进动脉硬化的发生、发展。此外,Cys C及其降解产物能激活中性粒细胞,促进炎症介质的生成,参与炎症过程,最终诱发动脉硬化[31-33]。CKD患者高水平的Hcy可以破坏动脉壁的弹性层、促进血管平滑肌细胞的增殖和迁移及动脉壁胶原纤维的沉积[34-35];另外,Hcy水平的升高会加剧氧化应激反应和血管内皮细胞的炎症,降低NO的生成和生物利用度,导致内皮依赖性血管舒张功能障碍,而内皮舒张功能障碍会引发血管炎症反应,进一步刺激血管壁中的细胞因子和血管活性物质的生成,从而导致动脉硬化的形成[36-37]。

综上,在CKD患者中,随着肾功能损伤的进展,Cys C和Hcy水平逐渐增高,动脉硬化的发生率亦随之增加,Cys C及Hcy的增加均是动脉硬化的独立危险因素,因此检测血中Cys C及Hcy水平对于CKD患者动脉硬化的诊断有重要的临床指导意义。

利益冲突声明

作者声称无任何利益冲突。

原文网址

http://xbyxb.csu.edu.cn/xbwk/fileup/PDF/2021121338.pdf

参考文献

- 1. Zhang L, Wang F, Wang L, et al. Prevalence of chronic kidney disease in China: a cross-sectional survey[J]. Lancet, 2012, 379(9818): 815-822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Brück K, Stel VS, Gambaro G, et al. CKD prevalence varies across the European general population[J]. J Am Soc Nephrol, 2016, 27(7): 2135-2147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ramesh S, Zalucky A, Hemmelgarn BR, et al. Incidence of sudden cardiac death in adults with end-stage renal disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis[J]. BMC Nephrol, 2016, 17(1): 78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Liu M, Li XC, Lu L, et al. Cardiovascular disease and its relationship with chronic kidney disease[J]. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci, 2014, 18(19): 2918-2926. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Sequí-Domínguez I, Cavero-Redondo I, Álvarez-Bueno C, et al. Accuracy of pulse wave velocity predicting cardiovascular and all-cause mortality. A systematic review and Meta-analysis[J]. J Clin Med, 2020, 9(7): 2080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Sarafidis PA, Loutradis C, Karpetas A, et al. Ambulatory pulse wave velocity is a stronger predictor of cardiovascular events and all-cause mortality than office and ambulatory blood pressure in hemodialysis patients[J]. Hypertension, 2017, 70(1): 148-157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Gu X, Man C, Zhang H, et al. High ankle-brachial index and risk of cardiovascular or all-cause mortality: A Meta-analysis[J]. Atherosclerosis, 2019, 282: 29-36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Xu L, He R, Hua X, et al. The value of ankle-branchial index screening for cardiovascular disease in type 2 diabetes[J]. Diabetes Metab Res Rev, 2019, 35(1): e3076. (2018-09-25)[2021-01-25]. 10.1002/dmrr.3076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Premaratne E, MacIsaac RJ, Finch S, et al. Serial measurements of cystatin C are more accurate than creatinine-based methods in detecting declining renal function in type 1 diabetes[J]. Diabetes Care, 2008, 31(5): 971-973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. He L, Li J, Zhan J, et al. The value of serum cystatin C in early evaluation of renal insufficiency in patients undergoing chemotherapy: a systematic review and Meta-analysis[J]. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol, 2019, 83(3): 561-571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Yamashita H, Nishino T, Obata Y, et al. Association between cystatin C and arteriosclerosis in the absence of chronic kidney disease[J]. J Atheroscler Thromb, 2013, 20(6): 548-556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Chung YK, Lee YJ, Kim KW, et al. Serum cystatin C is associated with subclinical atherosclerosis in patients with type 2 diabetes: A retrospective study[J]. Diab Vasc Dis Res, 2018, 15(1): 24-30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Okura T, Miyoshi K, Irita J, et al. Hyperhomocysteinemia is one of the risk factors associated with cerebrovascular stiffness in hypertensive patients, especially elderly males[J]. Sci Rep, 2014, 4: 5663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Chen L, Wang B, Wang J, et al. Association between serum total homocysteine and arterial stiffness in adults: a community-based study[J]. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich), 2018, 20(4): 686-693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ma YC, Zuo L, Chen JH, et al. Modified glomerular filtration rate estimating equation for Chinese patients with chronic kidney disease[J]. J Am Soc Nephrol, 2006, 17(10): 2937-2944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Welton PK, Carey RM, Aronow WS, et al. 2017 ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA Guideline for the Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Management of High Blood Pressure in Adults: Executive Summary: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines[J/OL]. Circulation, 2018, 138(17): e426-e483 (2018-10-22)[2021-01-25]. 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ma Y, Zhou L, Dong J, et al. Arterial stiffness and increased cardiovascular risk in chronic kidney disease[J]. Int Urol Nephrol, 2015, 47(7): 1157-1164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Grams ME, Yang W, Rebholz CM, et al. CRIC Study Investigators. Risks of adverse events in advanced CKD: The Chronic Renal Insufficiency Cohort (CRIC) Study[J]. Am J Kidney Dis, 2017, 70(3): 337-346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Vlachopoulos C, Aznaouridis K, Stefanadis C. Prediction of cardiovascular events and all-cause mortality with arterial stiffness: a systematic review and Meta-analysis[J]. J Am Coll Cardiol, 2010, 55(13): 1318-1327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Pandey A, Khan H, Newman AB, et al. Arterial stiffness and risk of overall heart failure, heart failure with preserved ejection fraction, and heart failure with reduced ejection fraction: The Health ABC Study (Health, Aging, and Body Composition) [J]. Hypertension, 2017, 69(2): 267-274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Yang W, Zhang S, Zhang S, et al. Relation between serum cystatin C level and brachial-ankle pulse wave velocity in Chinese general population[J]. Clin Exp Hypertens, 2018, 40(1): 1-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Wang K, Wang Y, Chu C, et al. Joint association of serum homocysteine and high-sensitivity C-reactive protein with arterial stiffness in Chinese population: A 12-year longitudinal study[J]. Cardiology, 2019, 144(1/2): 27-35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Chung YK, Lee YJ, Kim KW, et al. Serum cystatin C is associated with subclinical atherosclerosis in patients with type 2 diabetes: A retrospective study[J]. Diab Vasc Dis Re, 2018, 15(1): 24-30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ozkok A, Akpinar TS, Tufan F, et al. Cystatin C is better than albuminuria as a predictor of pulse wave velocity in hypertensive patients[J]. Clin Exp Hypertens, 2014, 36(4): 222-226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Wang D, Feng JF, Wang AQ, et al. Role of cystatin C and glomerular filtration rate in diagnosis of kidney impairment in hepatic cirrhosis patients[J]. Medicine (Baltimore), 2017, 96(20): e6949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Dharnidharka VR, Kwon C, Stevens G. Serum cystatin C is superior to serum creatinine as a marker of kidney function: a meta-analysis[J]. Am J Kidney Dis, 2002, 40(2): 221-226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kundi H, Kiziltunc E, Ates I, et al. Association between plasma homocysteine levels and end-organ damage in newly diagnosed type 2 diabetes mellitus patients[J]. Endocr Res, 2017, 42(1): 36-41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kong X, Ma X, Zhang C, et al. Hyperhomocysteinemia increases the risk of chronic kidney disease in a Chinese middle-aged and elderly population-based cohort[J]. Int Urol Nephrol, 2017, 49(4): 661-667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. van Varik BJ, Vossen LM, Rennenberg RJ, et al. Arterial stiffness and decline of renal function in a primary care population[J]. Hypertens Res, 2017, 40(1): 73-78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Chen YF, Chen C. Estimated glomerular filtration rate and arterial stiffness in Japanese population: a secondary analysis based on a cross-sectional study[J]. Lipids Health Dis, 2019, 18(1): 57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Cheng XW, Huang Z, Kuzuya M, et al. Cysteine protease cathepsins in atherosclerosis-based vascular disease and its complications[J]. Hypertension, 2011, 58(6): 978-986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Tsai HT, Wang PH, Tee YT, et al. Imbalanced serum concentration between cathepsin B and cystatin C in patients with pelvic inflammatory disease[J]. Fertil Steril, 2009, 91(2): 549-555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Eriksson P, Deguchi H, Samnegård A, et al. Human evidence that the cystatin C gene is implicated in focal progression of coronary artery disease[J]. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol, 2004, 24(3): 551-557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Jiang C, Zhang H, Zhang W, et al. Homocysteine promotes vascular smooth muscle cell migration by induction of the adipokine resistin[J]. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol, 2009, 297(6): C1466-C1476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Steed MM, Tyagi SC. Mechanisms of cardiovascular remodeling in hyperhomocysteinemia[J]. Antioxid Redox Signal, 2011, 15(7): 1927-1943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Spoelstra-De Man AM, Smulders YM, Dekker JM, et al. Homocysteine levels are not associated with cardiovascular autonomic function in elderly Caucasian subjects without and with type 2 diabetes mellitus: Hoom study[J]. J Intern Med, 2005, 258(6): 536-543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Ungvari Z, Csiszar A, Edwards JG, et al. Increased superoxide production in coronary arteries in hyperhomocysteinemia: role of tumor necrosis factor-alpha, NAD(P)H oxidase, and inducible nitric oxide synthase[J]. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol, 2003, 23(3): 418-424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]