Abstract

The Drosophila Groucho (Gro) protein is a corepressor required by a number of DNA-binding transcriptional repressors. Comparison of Gro with its homologues in other eukaryotic organisms reveals that Gro contains, in addition to a conserved C-terminal WD repeat domain, a conserved N-terminal domain, which has previously been implicated in transcriptional repression. We determined, via a variety of hydrodynamic measurements as well as protein cross-linking, that native Gro is a tetramer in solution and that tetramerization is mediated by two putative amphipathic α-helices (termed leucine zipper-like motifs) found in the N-terminal region. Point mutations in the leucine zipper-like motifs that block tetramerization also block repression by Gro, as assayed in cultured Drosophila cells with Gal4-Gro fusion proteins. Furthermore, the heterologous tetramerization domain from p53 fully substitutes for the Gro tetramerization domain in transcriptional repression. These findings suggest that oligomerization is essential for Gro-mediated repression and that the primary function of the conserved N-terminal domain is to mediate this oligomerization.

Promoter activity in eukaryotic cells is regulated, in large part, by coactivators and corepressors (25). These factors do not bind DNA on their own but are recruited to the DNA by protein-protein interactions with DNA-binding transcription factors. Coactivators and corepressors appear to modulate rates of transcription by a variety of mechanisms. These include direct interactions with the basal machinery to assist in the recruitment of this machinery to the promoter, as well as interactions with the chromatin template, which may serve to modulate the accessibility of the template.

The product of the Drosophila groucho (gro) gene is a corepressor that plays multiple roles in development (35). This gene is 1 of 11 genes in the Enhancer of split complex which encode factors that negatively regulate neurogenesis (5, 39). Gro lacks any recognizable DNA binding motif and does not appear to interact directly with DNA. Rather, Gro contains multiple tandemly repeated copies of a 40-amino-acid motif known as the WD repeat (21). This motif, which is present in a large number of proteins performing an array of cellular functions (33), is thought to provide a protein-protein interaction interface (28, 30, 43).

The Gro corepressor is recruited to the template via protein-protein interactions with a wide variety of Drosophila transcription factors. For example, Gro mediates repression by the members of the Hairy family of transcriptional repressors. Members of this family include Hairy, which regulates neurogenesis and segmentation (40); Deadpan, which regulates sex determination (53); and seven of the protein products of the Enhancer of split complex (13, 27). These factors are characterized by a number of conserved sequence features, including a basic helix-loop-helix DNA binding and dimerization domain and a C-terminal WRPW tetrapeptide motif. Hairy family factors are thought to recruit Gro to the template via a protein-protein interaction that requires the WRPW motif (16, 36).

Other factors that repress transcription via Gro include Runt (2), Engrailed (24), and Dorsal (15). The Dorsal protein functions as both an activator and a repressor to control genes required for dorsal-ventral pattern formation in the early embryo (11). Activation by Dorsal may involve recruitment of the coactivator CBP (1), while Gro is critical for Dorsal-mediated repression (15). The interaction between Dorsal and Gro is of low affinity, and stable recruitment of Gro by Dorsal appears to require the formation of a multiprotein DNA-bound complex that includes Gro, Dorsal, and additional DNA-binding transcription factors (46).

Gro homologues are found in a wide variety of eukaryotic organisms. For example, the yeast Tup1 protein may be a Gro homologue, since it contains C-terminal WD repeats and functions as a corepressor in conjunction with a broad array of DNA-binding repressors (26, 50). In addition, human cells contain several proteins termed transducin-like Enhancer of split proteins that are clearly homologous to Gro, in terms of both sequence and biological function (22, 44). The mouse homologues of the transducin-like Enhancer of split proteins are termed Grg proteins (29, 31, 32). Gro and its homologues in multicellular eukaryotes share, in addition to the C-terminal WD repeat domain, a highly conserved N-terminal region (44, 45). Previous studies have suggested that this N-terminal region can function as a repression domain (16) and a dimerization domain (38).

In an effort to illuminate the mechanism of transcriptional repression by Gro, we have examined the quaternary structure of native Gro protein. We found that the protein forms a homotetramer and that tetramerization is mediated by a pair of putative amphipathic α-helices in the conserved N-terminal domain. Furthermore, we have shown that point mutations in the tetramerization domain that block tetramerization also prevent Gro-mediated transcriptional repression in cultured cells. Finally, we found that a heterologous tetramerization domain can substitute for the Gro N-terminal region in repression, suggesting that the only function of this N-terminal region essential for its role in repression is the tetramerization function.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plasmids.

For the expression of Gal4-Gro fusion proteins in SL2 cells we used plasmid pActGal4Gro (16) (kindly provided by M. Caudy). The luciferase reporter plasmids are based on the pGL3-Basic vector (Promega). The vector ptkLuc was constructed by inserting a SalI/XhoI fragment from -37tkCAT (12) into the XhoI site of pGL3-Basic. pDE5tkLuc and pS4tkLuc were generated by inserting the SphI (blunted)/XhoI fragments from ptkCAT5X(dl-Ebox) (41) and -37tkCAT9 (12) into ptkLuc between the SmaI and XhoI sites. The reporter plasmids containing five UASG repeats were constructed by inserting XbaI/HindIII fragments (both ends blunted) from pG5MLTG− (kindly provided by M. Carey) into the SacI or SalI site of the reporter vectors listed above.

Protein preparation and cross-linking analysis.

The recombinant baculovirus expressing FLAG-tagged M2-Gro was kindly provided by J. Zwicker and R. Tjian, and purification of M2-Gro was conducted as described previously (7). The constructs for expressing six-His-tagged Gro(2–194), containing amino acids 2 to 194, proteins in Escherichia coli BL21(DE3) cells were made by inserting PCR-generated fragments into the NdeI/BamHI sites of the pET-3C vector. The E. coli cells were grown and lysed as described previously (41). The 6HGro(2–194) proteins were purified from inclusion bodies, which were solubilized in buffer A (25 mM HEPES, pH 7.6; 20% glycerol; 0.1% Nonidet P-40; and 1 mM dithiothreitol [DTT]) containing 6 M guanidine-HCl, 0.5 M KCl, and 20 mM imidazole. The solubilized proteins were then incubated with Ni-nitrilotriacetic acid agarose (Qiagen). The agarose beads were subsequently extensively washed with buffer A containing 6 M guanidine-HCl, 1 M KCl, and 20 mM imidazole, then with buffer A containing 6 M guanidine-HCl, 2 M KCl, and 20 mM imidazole, and finally with buffer A containing 6 M guanidine-HCl, 0.5 M KCl, and 60 mM imidazole. The imidazole concentration in the wash buffer was then increased first to 100 mM, then to 200 mM, and finally to 500 mM to elute bound proteins. Fractions containing the pure His-tagged protein were pooled and dialyzed into buffer A containing 0.1 M KCl.

The protein cross-linking analysis was conducted as follows. Equal amounts of purified or in vitro-translated Gro proteins were incubated in a buffer containing 20 mM HEPES (pH 7.6), 1.5 mM MgCl2, 50 mM NaCl, 10% glycerol, 0.5 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 0.2 mM EDTA, 20 mM DTT, and 0.05% Nonidet P-40 with various concentrations of glutaraldehyde at 37°C for 20 min. Cross-linking reactions were stopped by the addition of sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) sample buffer and further analyzed by SDS-PAGE and either Coomassie blue staining or autoradiography.

ND-PAGE, gel filtration, and sucrose gradient sedimentation analyses.

Nondenaturing (ND)-PAGE was conducted by the procedure described in the ND Protein Molecular Weight Determination Kit from Sigma. Purified Gro was analyzed on a Superdex 200 gel filtration column connected to a fast protein liquid chromatography system with a running buffer containing 50 mM sodium phosphate, pH 7.4, and 150 mM NaCl. The column was calibrated with native protein standards from Pharmacia. About 10 μg of purified Gro was loaded onto the column, and 0.5-ml fractions were collected. A total of 100 μl of each fraction was concentrated by trichloroacetic acid precipitation and further analyzed by SDS-PAGE and silver staining for the presence of Gro. Sucrose (5 to 20%) gradient sedimentation was performed as described previously (17). To calculate the native molecular weight (M) of Gro from its Stokes radius (59.5 Å), derived from gel filtration, and its sedimentation coefficient (14.5S), determined by sucrose gradient centrifugation, we applied the following equation (42): M = 6πηNas/(1−υρ), where a is the Stokes radius, s is the sedimentation coefficient, υ is the partial specific volume (0.725 cm3 g−1), η is the viscosity of the medium (0.01 P), ρ is the density of the medium (1 g cm−3), and N is Avogadro’s number. To determine the frictional-coefficient ratio, we applied the following equation (42): f/f0 = a/(3υM/4πN)1/3.

Site-directed mutagenesis and yeast two-hybrid assays.

The single point mutant forms (containing either L38P or L87P) and double point mutant forms (containing both L38P and L87P) of Gro were generated with the pET17b-Gro vector (36) as the DNA template and the QuickChange site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene). Two pairs of complementary oligonucleotide primers were used for mutagenesis. The sequences of the coding strand-mutagenic oligonucleotides were 5′-GAGGAGTTCAACTTCCCGCAGGCGCACTACCAC-3′ and 5′-GAGATCGCCAAGCGGCCGAACACACTGATCAACCAG-3′ (mutated base pairs are underlined). All point mutations were confirmed by DNA sequencing. The yeast two-hybrid assays were performed as described previously (36).

In vitro translation and coimmunoprecipitation.

In vitro transcription and translation were performed as described previously (41). The wild-type and mutant versions of pET17b-Gro vectors were used to generate [35S]methionine-labeled full-length Gro. The DNA fragments for making the C-terminal-deletion variants 35S-Gro(1–133), -(1–194), -(1–255), and -(1–390) were produced by PCR with Pfu DNA polymerase and directly used in the in vitro transcription and translation reactions. The plasmids for generating the N-terminal-deletion variants Gro(134–719), -(195–719), -(257–719), and -(391–719) were constructed by inserting the corresponding PCR-generated fragment into the BamHI/SalI sites of pGEM-3Zf(+) (Promega). These constructs were linearized with either HindIII or HincII and subsequently utilized for in vitro transcription and translation. Coimmunoprecipitation assays were conducted as described previously (15) with purified M2-Gro and the 35S-Gro variants.

Transient transfection, luciferase reporter assays, and immunoblotting.

Calcium phosphate cotransfections into Drosophila SL2 cells were performed as described previously (12). In general, 5 μg of luciferase reporter, 0.1 μg of TK-RLuc internal control reporter (Promega), 4 μg of each Gal4-Gro fusion construct, and 11 μg of pBluescript carrier DNA were transfected with either 60 ng of pPacDorsal and 20 ng of pPacTwi (41) or 20 ng of pPacSp1 (12). The luciferase reporter activity was determined with the dual-luciferase reporter assay system (Promega). To monitor the expression level of Gal4-Gro fusion proteins, 1-ml aliquots of total cell lysate (from about 4 × 107 transfected SL2 cells) were first precipitated with 1 μg of polyclonal anti-Gal4 DNA binding domain antibody (Santa Cruz) by the IMMUNOcatcher system (CytoSignal). After being extensively washed with the lysis buffer, the immunoprecipitates were resolved by SDS-PAGE and subsequently immunoblotted with the anti-Gal4 DNA binding domain antibody.

RESULTS

Determination of the oligomeric state of Gro.

To characterize the molecular properties of Gro, we have expressed and immunoaffinity purified FLAG epitope-tagged Gro to near homogeneity with the baculovirus expression system (Fig. 1A). Starting with 109 recombinant baculovirus-infected Sf9 cells, we routinely obtained 150 to 200 μg of purified epitope-tagged Gro. The Gro protein prepared in this way is more than 95% pure, as judged by Coomassie blue staining of an SDS-polyacrylamide gel (Fig. 1A, lanes 3 and 4). Gro has an apparent subunit molecular mass of 89 kDa as determined by SDS-PAGE. This value is somewhat greater than the molecular mass calculated from the amino acid sequence of the epitope-tagged protein, which is 81 kDa.

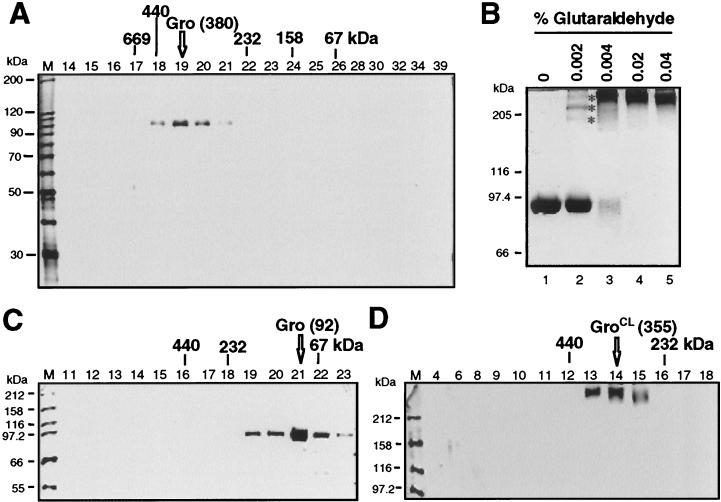

FIG. 1.

Determination of the molecular mass of native Gro. (A) Expression and purification of FLAG-tagged Gro. A Coomassie blue-stained SDS–8% polyacrylamide gel is shown. Lane 1, protein mass markers (MM) with sizes indicated on the left; lane 2, 10 μl of nuclear extract (NE) prepared from Sf9 insect cells infected with the baculovirus expressing FLAG-tagged Gro; lane 3, 1.0 μg of purified Gro; lane 4, 0.5 μg of purified Gro. (B) ND-PAGE analysis of Gro. A Coomassie blue-stained ND–8% polyacrylamide gel is shown. Lanes 1 and 6, bovine serum albumin (66-kDa monomer and 132-kDa dimer); lanes 2 and 5, urease (272-kDa trimer and 545-kDa hexamer); lanes 3 and 4, 1.0 μg of purified Gro (marked by asterisks) without (−DTT) or with (+DTT) treatment with 40 mM DTT prior to electrophoresis. (C) Molecular mass determination. The calibration curve prepared from Ferguson plots is shown (see text for details). The known masses of standards and the calculated mass of native Gro are given in kilodaltons above the curve.

To estimate the native size of Gro, the purified protein was analyzed by ND-PAGE on gels of various polyacrylamide concentrations (6, 7, 8, and 9%). A representative 8% gel stained with Coomassie blue (Fig. 1B) shows that, in the absence of DTT, Gro runs as a high-molecular-mass aggregate, with a mobility lower than that of the 545-kDa standard (lane 3). However, after treatment with DTT to break disulfide bonds, the protein migrates between the 272- and 545-kDa standards (Fig. 1B, lane 4).

To more precisely determine the native molecular mass of Gro, we calculated the mobilities of the protein standards and of Gro relative to the tracking dye in each gel (data not shown). This information was then used to generate plots of mobility versus polyacrylamide concentration. The slopes of such plots represent the “retardation coefficients” of the proteins (4). A log-log plot in which the negative retardation coefficients of the standards were plotted against the known native molecular masses of the standards was then generated (Fig. 1C). From this calibration curve, we estimate that Gro has a native size of 371 kDa under reducing conditions. Since this is roughly four times the subunit molecular mass, these findings suggest that Gro is a tetramer under reducing conditions and that it forms a higher-order aggregate under oxidizing conditions. Since the inside of a eukaryotic cell is generally viewed as a reducing environment that does not favor the formation of disulfide bonds, all subsequent analysis was carried out under reducing conditions.

To confirm the findings from ND-PAGE, purified Gro was subjected to Superdex 200 gel filtration chromatography. The column fractions were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and silver staining for the presence of Gro (Fig. 2A). The Gro peak (fraction 19) eluted between the 440- and 232-kDa standards. Quantitative analysis of the data yielded a native molecular mass for Gro of 380 kDa, in excellent agreement with the ND-PAGE analysis, which yielded a value of 371 kDa. This also suggests that Gro is a tetramer under native conditions.

FIG. 2.

Analysis of Gro quaternary structure by gel filtration, cross-linking, and velocity sedimentation. (A) Superdex 200 gel filtration of DTT-treated Gro. A silver-stained SDS-PAGE gel is shown with gel filtration fraction numbers labeled at the top of each lane. Fractions with peak levels of native protein standards that were run in a parallel gel filtration experiment are indicated above the gel: thyroglobulin, 669 kDa (Stokes radius, 88 Å); ferritin, 440 kDa (62 Å); catalase, 232 kDa (52.2 Å); aldolase, 158 kDa (48 Å); and bovine serum albumin, 67 kDa (35 Å). The position of the Gro peak is indicated by an arrow. (B) Protein cross-linking analysis of Gro. Equal amounts of Gro plus DTT were incubated with various concentrations of glutaraldehyde (indicated above each lane). Cross-linked Gro products were resolved by SDS-PAGE and visualized by Coomassie blue staining. The Gro multimers resulting from cross-linking with sizes corresponding to Gro dimer, trimer, and tetramer are marked with asterisks. (C and D) Sucrose gradient (5 to 20%) centrifugation of non-cross-linked (C) or cross-linked (D) Gro. Silver-stained SDS-PAGE gels to analyze gradient fractions for the presence of Gro are shown, with fraction numbers indicated at the top of each lane. The peak positions of native protein standards centrifuged through parallel gradients are indicated above the gel: ferritin (440 kDa), catalase (232 kDa), and bovine serum albumin (67 kDa). The positions of Gro or Gro incubated with 0.05% glutaraldehyde (GroCL) prior to centrifugation are indicated.

We next employed glutaraldehyde cross-linking analysis to examine the oligomeric state of Gro. Purified Gro was incubated with concentrations of glutaraldehyde ranging from 0.002 to 0.04% and then analyzed by SDS-PAGE and Coomassie blue staining (Fig. 2B). After treatment with 0.002% glutaraldehyde, we observed three distinct cross-linked forms with sizes corresponding to those of the Gro dimer, trimer, and tetramer (Fig. 2B, lane 2). At higher concentrations of glutaraldehyde, Gro was quantitatively cross-linked in a high-molecular-mass form (Fig. 2B, lanes 3 to 5). Although the mobility of this final cross-linked species on SDS-PAGE gels is consistent with the idea that it is a tetramer, the resolution in this region of the gel was poor. We therefore used velocity sedimentation through a sucrose gradient to determine more accurately the size of the cross-linked species. After centrifugation, sucrose gradients were fractionated and analyzed by SDS-PAGE and silver staining for the presence of Gro. Cross-linked Gro (GroCL) sedimented at a position between the 440-kDa (ferritin) and 232-kDa (catalase) standards (Fig. 2D). The estimated molecular mass of the cross-linked protein from the sedimentation analysis was 355 kDa, consistent with the idea that the protein is a tetramer. Somewhat surprisingly, when Gro was not cross-linked prior to sedimentation, the protein sedimented at a position close to that of the 67-kDa protein marker (Fig. 2C), suggesting that Gro is monomeric under these conditions. Thus, it appears that Gro tetramers are unstable and dissociate under the conditions of sucrose gradient centrifugation, a phenomenon described previously for other oligomeric proteins (18). In contrast to the dramatic effect of glutaraldehyde cross-linking on the sedimentation velocity of Gro, cross-linking has no effect on the gel filtration mobility of the protein (data not shown), strongly suggesting that cross-linking does not, by itself, perturb the size or shape of the protein.

Although we have used gel filtration and sedimentation to estimate the molecular mass of Gro, these techniques are, strictly speaking, direct measures of Stokes radius and sedimentation coefficient, respectively. In employing these approaches to determine molecular mass, we have assumed that Gro and the protein standards have roughly similar shapes. By combining information about the Stokes radius and the sedimentation coefficient of Gro, it is possible to estimate the molecular mass of Gro without making any assumptions about shape (42). From the Stokes radii and sedimentation coefficients of the protein standards, we estimated that Gro has a Stokes radius of 59.5 Å and a sedimentation coefficient (after cross-linking) of 14.5S. By combining these values (see Materials and Methods), we estimated a molecular mass for Gro of 360 kDa, consistent once again with the idea that Gro is a tetramer. Evaluation of the hydrodynamic data can also yield information about the shape of native Gro. From the calculated molecular mass and the Stokes radius, we calculated an f/f0 ratio of 1.27 (see Materials and Methods). This value is consistent with the idea that the Gro tetramer is a prolate or oblate ellipsoid with an axial ratio of about 5 to 1 (6).

Mapping the tetramerization domain of Gro.

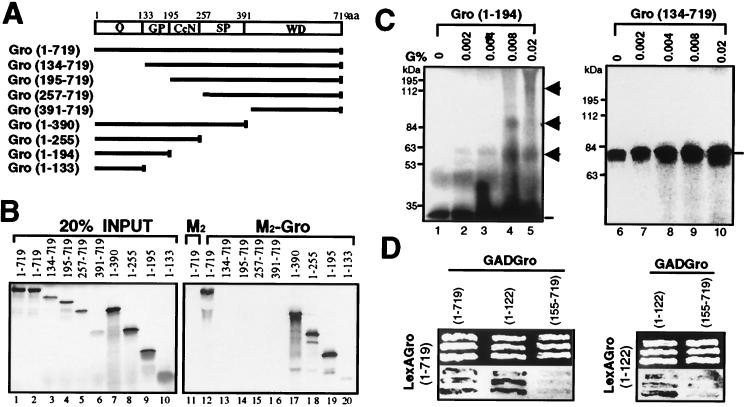

We next employed coimmunoprecipitation assays to map the region(s) responsible for Gro oligomerization. Using in vitro translation, we produced a series of [35S]methionine-labeled Gro deletion variants (Fig. 3A). These variants were then incubated with purified epitope-tagged Gro (M2-Gro). After immunoprecipitation with an anti-FLAG affinity resin, the precipitates were subjected to extensive washing. The bound 35S-Gro variants were then eluted and analyzed by SDS-PAGE and autoradiography (Fig. 3B). As a negative control for nonspecific binding, anti-FLAG affinity resin lacking M2-Gro was incubated with full-length 35S-Gro. Full-length 35S-Gro failed to associate with anti-FLAG affinity beads alone (Fig. 3B, lanes 1 and 11) but was strongly retained on the affinity beads containing purified M2-Gro (lanes 2 and 12). 35S-Gro variants lacking the N-terminal 133-amino-acid region failed to interact with M2-Gro (Fig. 3B, lanes 3 to 6 and 13 to 16), indicating a requirement of this region for binding. Conversely, all 35S-Gro deletion variants possessing the first 133 amino acids bound to M2-Gro (Fig. 3B, lanes 7 to 10 and 17 to 20), revealing that this region is both necessary and sufficient for the interaction.

FIG. 3.

Mapping the tetramerization domain of Gro. (A) Schematic diagram of various full-length or truncated [35S]methionine-labeled Gro proteins that were produced by in vitro translation. The conserved N-terminal glutamine-rich domain (Q) and C-terminal WD repeat domain (WD) are indicated. GP and SP, glycine-proline and serine-proline, respectively, which are predominant in these regions; CcN, CcN motif containing putative cdc2 and casein kinase II phosphorylation sites as well as a nuclear localization signal (44); aa, amino acids. (B) In vitro coimmunoprecipitation assays. Purified FLAG-tagged Gro (1 μg) (M2-Gro) immobilized on anti-FLAG affinity resin was incubated with 10 μl of each of the 35S-labeled Gro variants. Lanes 1 to 10 show an amount of each input protein equal to 20% of the amount used in the binding reactions shown in lanes 11 to 20. After being extensively washed, the bound 35S-Gro was eluted with SDS-PAGE sample buffer, resolved by SDS-PAGE, and visualized by autoradiography (lanes 12 to 20). As a negative control, the anti-FLAG affinity bead (M2) alone was examined for interaction with full-length 35S-Gro (11). (C) Cross-linking analysis of truncated 35S-Gro proteins. Cross-linking reactions conducted as described in the legend to Fig. 2B were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and autoradiography. The left and right panels show the cross-linking profiles of 35S-labeled Gro(1–194) and Gro(134–719), respectively. The percent glutaraldehyde (G%) used in the cross-linking reactions is shown above the lanes. The 35S-Gro monomers are indicated by lines, and cross-linked dimer, trimer, and tetramer species are indicated by arrowheads. The sizes of prestained protein markers are indicated on the left. (D) Yeast two-hybrid analysis of Gro oligomerization. The top panels show three independent yeast colonies cotransformed with the LexA DNA binding domain-Gro fusion proteins (LexAGro, indicated on the left of each panel) and GAD-Gro fusion proteins (GADGro, indicated on the top of each panel). The bottom panels show the results of growing these colonies in the presence of the chromogenic β-galactosidase substrate X-Gal. Cells expressing β-galactosidase turn blue.

Protein cross-linking assays were utilized to confirm that the N-terminal region of Gro directly mediates protein tetramerization. When incubated with glutaraldehyde, 35S-Gro(1–194), which contains the N-terminal domain, was cross-linked to produce higher-molecular-mass species with molecular masses approximating those expected for the dimer, trimer, and tetramer (Fig. 3C, lanes 2 to 5). In contrast, 35S-Gro(134–719), which lacks the N-terminal domain, did not yield cross-linked species under the same conditions (Fig. 3C, lanes 7 to 10). Note that in this experiment, the relatively low level of cross-linking observed with the N-terminal domain and the diffuse appearance of the bands representing the cross-linked species can most likely be attributed to interference by the impurities present in the unpurified in vitro-translated protein. When pure protein was used in a similar experiment (see Fig. 4E below), we observed a much higher cross-linking efficiency and the cross-linked species had much more discrete electrophoretic mobilities.

FIG. 4.

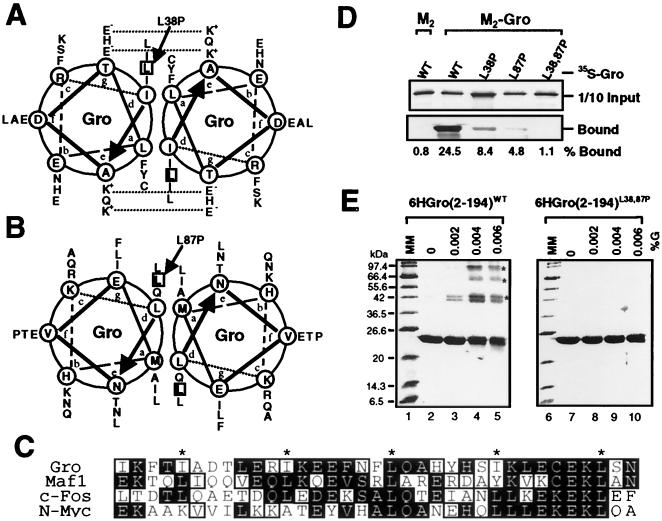

Sequence analysis and mutagenesis of the tetramerization domain. (A to C) Sequence analyses of the N-terminal tetramerization region of Gro. (A and B) Helical-wheel projections of the two putative LZL segments (residues 24 to 52 and 73 to 100) found in this region. Heptad positions are labeled by letters a through g in the wheels, where hydrophobic residues at positions a and d constitute the cores of proposed Gro homodimeric coiled coils. Potential interhelical salt bridges between charged residues at positions e and g are indicated by dashed lines. The two leucine residues (L38 and L87) mutated to prolines are boxed. (C) Sequence alignment of Gro LZL motif (residues 20 to 54) with leucine zippers found in the proto-oncogene products Maf-1 (9), c-Fos (47), and N-Myc (14). Identical residues are shaded in black and conserved residues are boxed. The hydrophobic residue at the d position of each heptad repeat is labeled with an asterisk. (D) The double point mutation (L38,87P) abolishes Gro oligomerization in vitro. With the coimmunoprecipitation assays described in the legend to Fig. 3B, wild-type (WT) and mutant forms of full-length 35S-Gro (indicated at the top of the gel) were examined for interaction with purified FLAG-tagged Gro (M2-Gro). The upper panel shows 10% of the input 35S-Gro proteins used for assays and the lower panel indicates 35S-Gro retained on the anti-FLAG M2 beads alone or beads with purified M2-Gro. The percentage of input protein bound is indicated on the bottom of each lane. (E) Cross-linking analyses of wild-type (WT) and mutant Gro tetramerization domains. Wild-type and mutant forms of the six-histidine-tagged N-terminal region (residues 2 to 194) of Gro (6HGro) were purified and subjected to protein cross-linking assays as described in the legend to Fig. 2B. Cross-linked products were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and Coomassie blue staining. The cross-linking patterns of wild-type and L38,87P mutant forms of 6HGro are shown. The asterisks indicate the dimer, trimer, and tetramer species.

Yeast two-hybrid assays also revealed the involvement of the N-terminal region in homo-oligomerization (Fig. 3D). In these experiments, LexA fusion proteins containing all or some portions of Gro were tested for their ability to recruit Gal4 activation domain (GAD) fusion proteins containing all or some portions of Gro to a lacZ reporter gene with LexA binding sites. Successful recruitment was revealed by lacZ activation and, therefore, blue color on X-Gal (5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-d-galactopyranoside) indicator plates. A LexA-Gro(full length) fusion protein was able to recruit GAD-Gro(full length) and GAD-Gro(1–122), but not GAD-Gro(155–719), to the reporter. In addition, a LexA-Gro(1–122) fusion protein was able to recruit GAD-Gro(1–122), but not GAD-Gro(155–719), to the reporter. These results confirm that the N-terminal 122-amino-acid region is responsible for Gro tetramerization.

Sequence analysis of the N-terminal tetramerization domain of Gro.

The N-terminal region of Gro is highly conserved among the members of the Gro family of corepressor proteins (44). Sequence analysis of the conserved N-terminal region (with the Multicoil program) (51) predicted two α-helices (residues 24 to 52 and 73 to 100) in this region of Gro that have a high propensity to form coiled coils (data not shown). Sequence alignment with Gro homologues from Caenorhabditis elegans, Xenopus, zebra fish, rats, mice, and humans shows that the two putative amphipathic helices and the region between them are highly conserved in all Gro family members (data not shown). The first of these amphipathic helices was previously identified as a potential leucine zipper domain in other Gro family proteins (38). By using the consensus sequence produced by our alignment to search protein databases, we found that the first conserved motif does indeed have high sequence similarity with leucine zipper motifs present in the proto-oncogene products Maf-1 (9), c-Fos (47), and N-Myc (14) (Fig. 4C). In addition, the two motifs as well as the intervening sequence exhibit high sequence homology to multiple regions of two coiled-coil proteins: the murine homologue of the leukemia-associated PML isoform 1 (19) and human centromeric protein E (52) (data not shown). Because of their similarity to leucine zippers, we refer to these motifs as leucine zipper-like (LZL) motifs. Helical-wheel projections (Fig. 4A and B) of the two LZL motifs revealed that both segments contain 4-3 hydrophobic heptad repeats, since almost all residues at the a and d positions are hydrophobic in nature. In addition, as reported previously (38), potential interhelical salt bridges in the first LZL motif may further contribute to the stability and specificity of a potential parallel coiled-coil structure (Fig. 4A).

Role of the LZL motifs in Gro oligomerization.

To determine if the two LZL motifs are involved in Gro oligomerization, we replaced leucine residues (L38 and L87) in each motif with prolines (Fig. 4A and B). These substitutions greatly reduced the predicted propensity of these motifs to form coiled coils (data not shown). Using the coimmunoprecipitation assays described above, we first examined the effects of these mutations on the interaction with purified M2-Gro (Fig. 4D). Unlike wild-type 35S-Gro, which strongly interacted with M2-Gro (24.5% of input protein was bound), 35S-GroL38,87P bound M2-Gro very poorly (1.1% bound). The single mutants (35S-GroL38P and GroL87P) exhibited intermediate levels of binding (8.4 and 4.8% bound, respectively).

Using glutaraldehyde cross-linking assays, we further studied the effects of those mutations on Gro tetramerization. Wild-type or mutant forms of the Gro N-terminal domain (from residues 2 to 194) tagged with six N-terminal histidine residues [6HGro(2–194)] were expressed in E. coli and purified by metal-chelate affinity chromatography. Purified products were subjected to glutaraldehyde cross-linking, and cross-linked products were visualized on Coomassie blue-stained SDS-PAGE gels (Fig. 4E). Cross-linking of wild-type 6HGro(2–194) resulted in several multimeric species with the molecular masses expected for the dimer, trimer, and tetramer species (Fig. 4E, lanes 2 to 5). In contrast, the double point mutant form (L38,87P) of 6HGro(2–194) did not yield cross-linked species under the same conditions (Fig. 4E, lanes 7 to 10). Cross-linking of the single point mutant forms (L38P and L87P) resulted primarily in the production of a cross-linked dimer (data not shown). Thus, the L38,87P double point mutation abolishes Gro tetramerization, while the single point mutations have intermediate effects, indicating that both LZL motifs are required for efficient Gro tetramerization.

Role of the LZL motifs in Gro-mediated repression.

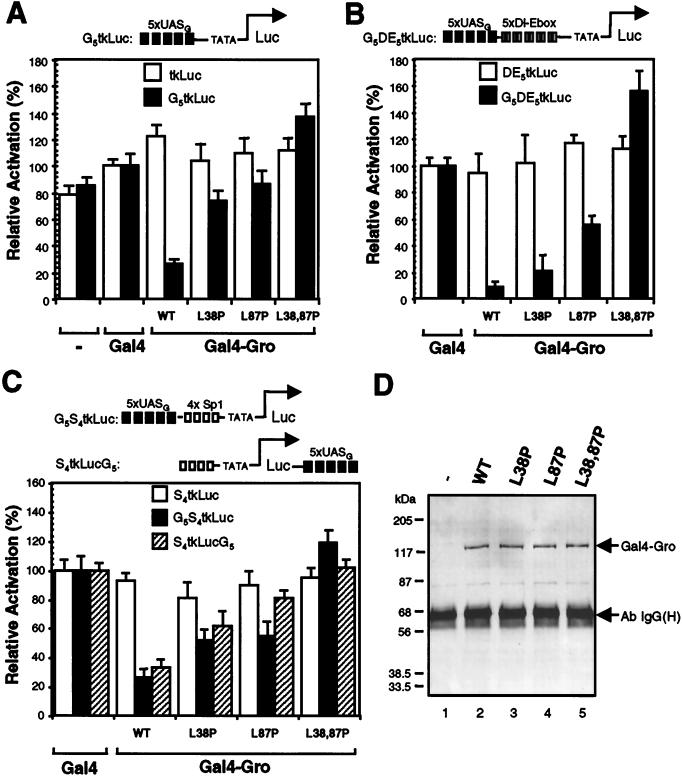

Using transient-transfection assays, Fisher and coworkers (16) have shown that Gro can actively repress transcription in Drosophila SL2 cells when directly targeted to a promoter by the heterologous Gal4 DNA binding domain. To take advantage of this assay, we generated expression constructs encoding proteins with the Gal4 DNA binding domain (residues 1 to 147) fused to the wild-type or mutant forms of Gro to study how these mutations affect Gro-mediated repression. Gal4-Gro fusion proteins were first examined for the ability to repress basal transcription (Fig. 5A). We cotransfected each Gal4-Gro fusion construct into SL2 cells with a luciferase reporter driven by the herpes simplex virus thymidine kinase core promoter (12) with or without five upstream Gal4 binding sites (G5tkLuc or tkLuc). The Gal4 DNA binding domain alone had a very minor stimulatory effect on transcription. Cotransfection of the vector encoding the wild-type Gal4-Gro fusion protein resulted in an approximately fourfold repression of transcription compared to the activity promoted by the Gal4 DNA binding domain alone. The level of repressed transcription was well below the basal level observed in the absence of the Gal4 DNA binding domain. This repression was dependent upon the Gal4 binding sites. The L38,87P double mutation of Gro completely abolished the repression activity, while the single mutants exhibited much-reduced repression activity. As shown by an immunoblot in which extracts of transfected cells were probed with an antibody against the Gal4 DNA binding domain, the wild-type and mutant proteins were expressed at nearly identical levels (Fig. 5D).

FIG. 5.

LZL motifs are essential for Gro-mediated repression in Drosophila SL2 cells. (A) Gal4-GroL38,87P fails to repress basal transcription. Expression constructs encoding the Gal4-DNA binding domain (residues 1 to 147) fused to wild-type or mutant forms of Gro were cotransfected into SL2 cells with one of the firefly luciferase reporters (either tkLuc or G5tkLuc) and an internal control reporter (pRL-TK) encoding Renilla luciferase. All firefly luciferase activities (measured by Promega’s dual-luciferase assay system and further normalized to Renilla luciferase activities) driven by Gal4-Gro fusion proteins were normalized to that mediated by Gal4(1–147) alone, which was set at 100%. Each bar represents the average + standard deviation of three independent duplicate experiments. (B) Gal4-GroL38,87P fails to repress transcription activated by the combination of Dorsal and Twist. SL2 cells were transfected with one of the luciferase reporters (DE5tkLuc or G5DE5tkLuc) and DNA constructs expressing Dorsal, Twist, and one of the indicated Gal4-Gro fusion proteins. All activities were normalized to the activity observed in the presence of Dorsal, Twist, and Gal4(1–147), which was set at 100%. (C) Gal4-GroL38,87P fails to repress transcription activated by Sp1. SL2 cells were transfected with one of the luciferase reporters (S4tkLuc, G5S4tkLuc, or S4tkLucG5) and with expression constructs encoding Sp1 and one of the indicated Gal4-Gro fusion proteins. All activities were normalized to the activity observed in the presence of Sp1 and Gal4(1–147), which was set at 100%. (D) Immunoblot analysis of the expression level of Gal4-Gro fusion proteins in the transient-transfection experiments described above. Gal4-Gro fusion proteins were first precipitated from total cell lysates with the anti-Gal4 DNA binding domain antibody, and the immunoprecipitates were then resolved by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with antibody against the Gal4 DNA binding domain. The positions of the Gal4-Gro fusion proteins and of the immunoglobulin G heavy chain [Ab IgG(H)] are indicated.

Previous genetic analysis has demonstrated that Gro is maternally required for conversion of Dorsal from an activator to a repressor (15). In addition, Dorsal and Twist proteins together can synergistically activate transcription in SL2 cells (41). To test the possibility that Gal4-Gro can override this synergistic activation, we prepared a luciferase reporter vector bearing five copies of a regulatory module containing both the Dorsal and Twist binding sites (Dl-Ebox [Fig. 5B]) (41), which were inserted just upstream of the herpes simplex virus thymidine kinase core promoter. Two versions of this vector, with and without Gal4 binding sites upstream of the Dorsal and Twist binding sites, were prepared (G5DE5tkLuc and DE5tkLuc). Cotransfection of expression vectors encoding Dorsal and Twist with these reporters resulted in 30- to 50-fold activation (reference 41 and data not shown). The addition of wild-type Gal4-Gro expression vectors resulted in strong Gal4 binding site-dependent repression (>15-fold) of the Dorsal-Twist-activated transcription (Fig. 5B). Therefore, when directly tethered to the promoter, Gro acts in a dominant fashion to repress the synergistic activation promoted by Dorsal and Twist. We next analyzed the effects of the Gro point mutations on repression. Gal4-GroL38,87P was unable to repress Dorsal-Twist-activated transcription, while both Gal4-GroL38P and Gal4-GroL87P retained partial binding site-dependent repression activity.

To determine if Gal4-Gro can repress transcription promoted by another activator, we prepared luciferase reporters containing Sp1 binding sites. For these experiments, we also examined the effect of altering the position of the Gal4 binding sites by placing them either immediately upstream of the Sp1 sites or ∼2 kb downstream of the transcriptional start site (Fig. 5C). In these assays, we found that Sp1 by itself yielded an approximately 10- to 15-fold activation of transcription (data not shown). The addition of wild-type Gal4-Gro resulted in binding site-dependent four- to fivefold repression of Sp1-activated transcription, regardless of the location of the binding sites (Fig. 5C). Thus, Gro can repress Sp1-activated transcription in not only a short-range but also a long-range manner when directly targeted to DNA by a heterologous DNA binding domain. Once again, the double point mutation disrupting both LZL motifs completely abolished repression, while the single point mutations exhibited a reduced ability to repress transcription. Thus, the double point mutation not only disrupts Gro tetramerization but also abolishes Gal4-Gro-dependent transcriptional repression, suggesting that tetramerization is required for Gro-mediated repression.

Replacement of the Gro tetramerization domain with a heterologous tetramerization domain.

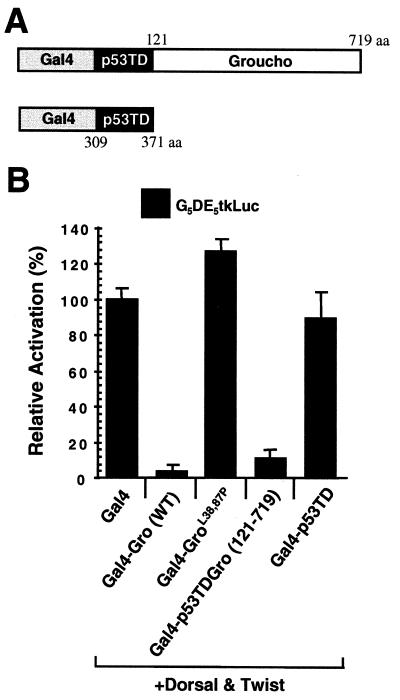

The N-terminal region of Gro is able to repress transcription when fused to the Gal4 DNA binding domain (16). Therefore, it is possible that the L38,87P mutation abolishes Gro-mediated repression, not because of its effect on homotetramerization but because of its effect on the ability of Gro to associate with another cofactor required for repression. To address this issue, we replaced the Gro tetramerization domain with the well-defined tetramerization domain of tumor suppressor protein p53 (residues 309 to 371 [Fig. 6A]) (8, 23). The replacement of the Gro tetramerization domain with the p53 tetramerization domain resulted in a chimeric protein that was able to repress transcription nearly as well as the wild-type Gal4-Gro fusion protein (Fig. 6B). The p53 tetramerization domain alone resulted in no repression when fused to the Gal4 DNA binding domain. Thus, the two tetramerization domains are functionally interchangeable, suggesting that the N-terminal region of Gro may function solely, or primarily, as an oligomerization domain.

FIG. 6.

Functional analysis of the Gro tetramerization domain. (A) Schematic diagram of the p53 tetramerization domain (p53TD)-containing transcription factor chimeras used in this experiment. p53TD is the region of p53 from residue 309 to residue 371. aa, amino acids. (B) The Gro and p53 tetramerization domains are functionally interchangeable for repression. Transient-transfection assays were conducted essentially as described in legend to Fig. 5B with the reporter G5DE5tkLuc and expression vectors expressing Dorsal, Twist, and each indicated Gal4 fusion protein. WT, wild type.

DISCUSSION

We have found that Gro forms a tetramer in solution and that tetramerization depends critically upon two putative amphipathic α-helices (LZL motifs) in the conserved N-terminal region. In addition, repression, as assayed in SL2 cells with Gal4 fusion proteins, depended upon these same two LZL motifs, strongly suggesting that tetramerization is a prerequisite for efficient transcriptional repression. Furthermore, full repression activity was observed when the Gro tetramerization domain was replaced with the tetramerization domain from p53. These findings imply that the primary and perhaps sole function of the N-terminal domain is to mediate tetramerization.

If the N-terminal domain functions only as a tetramerization domain, then how, as was demonstrated in a previous study (16), is it able to bring about transcriptional repression in SL2 cells when tethered to the DNA via a Gal4 DNA binding domain? This can be readily explained by the fact that most cells, including SL2 cells, contain high levels of endogenous Gro or Gro-related proteins (22). When the Gro tetramerization domain is tethered to the DNA via a Gal4 DNA binding domain, it is probably able to recruit endogenous Gro via the tetramerization interaction. Repression domains in regions of Gro outside the conserved N-terminal region would then be able to mediate repression.

A previous study on two of the Gro homologues in mice (Grg proteins) identified the conserved N-terminal domain as a dimerization domain (38). However, this study employed yeast two-hybrid assays and glutathione S-transferase pull-down assays to study oligomerization, and so the actual size of the native oligomer was not determined. Thus, with respect to the size of the oligomer, there is no conflict between our results and those obtained for the Grg proteins. The same study also examined, via glutathione S-transferase pull-down assays, the possible role of the first of the two LZL motifs in oligomerization and came to the conclusion that this region played only a minor role in oligomerization. We can reconcile these results with ours by noting two differences between the experiments. First, we chose to introduce prolines into the putative helices, because computer modeling had demonstrated that these substitutions nearly eliminated the propensity of the region to form coiled coils. The substitutions made in the previous study were more conservative in nature, and the mutant LZL motif was probably still capable of forming a coiled coil. Second, in the previous study, the second LZL motif was not recognized and was therefore not mutagenized. Our experiments show that the complete elimination of oligomerization requires the disruption of both LZL motifs.

How might Groucho oligomerization be required for transcriptional repression? One obvious possibility is that oligomerization serves to increase the concentration of DNA-bound repression domains, thereby increasing the efficiency of repression. A similar phenomenon has been observed for transcription factor Sp1 (10). Specifically, forms of Sp1 defective in DNA binding are able to synergize with wild-type Sp1 in the activation of transcription. This phenomenon is thought to reflect the ability of Sp1 to self-associate, thereby allowing wild-type Sp1 to recruit mutant Sp1 to the template. The resulting increase in the concentration of DNA-bound activation domains could then result in superactivation.

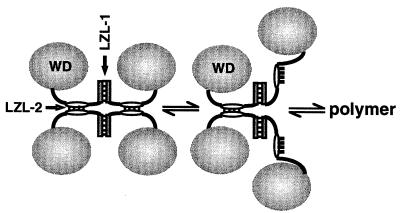

An alternative (but not mutually exclusive) explanation for the role of oligomerization in repression is that repression could require the polymerization of Gro along the template. Support for this idea comes from the finding that Groucho family proteins can bind histones (34). According to this model, perhaps the DNA-bound factors that recruit Gro to the template serve to nucleate a Gro polymer that spreads out along the template, thereby promoting a change in chromatin structure that results in transcriptional repression. The same LZL motifs that promote tetramerization could also promote polymerization (Fig. 7). In the context of chromatin, polymerization might be favored by favorable contacts between Gro and histones. Polymerization of Gro along the template could explain how this factor is able to repress transcription at a distance. A precedent for the idea that a corepressor needs to polymerize along the template may be provided by the yeast Sir3 and Sir4 proteins, which are thought to spread along the template from the HM silencers to induce heterochromatin formation, thereby inactivating the HM loci (20).

FIG. 7.

Speculative model for Gro tetramerization and Gro polymerization. Since leucine zippers are dimerization motifs, we postulate that the LZL motifs are dimerization motifs. The polymerization of Gro could be facilitated by the same interactions that promote tetramerization. In accord with this idea, we have modeled the Gro tetramer as a dimer of dimers (left). Breaking one of the coiled-coil interactions holding the tetramer together (middle) would expose hydrophobic surfaces that could be used in the further oligomerization (right) of Gro via contacts with the similar hydrophobic surfaces on another similarly disrupted tetramer. The postulated process is related to the phenomenon of domain swapping (3).

Tup1, a putative yeast homologue of Gro, lacks the LZL motifs found in Gro family members from multicellular eukaryotes. An explanation for this difference can perhaps be found in the fact that Tup1 functions as a part of a complex with the tetratricopeptide repeat-containing protein Ssn6, while no Ssn6 homologue has been identified in multicellular eukaryotes. The ratio of Tup1 to Ssn6 in this complex is four to one (48). Perhaps in the Tup1-Ssn6 complex, Ssn6 is serving to hold together four Tup1 protomers, making a homotetramerization domain in Tup1 unnecessary.

Finally, we note that paired amphipathic α-helices, such as those that we believe serve to mediate Gro tetramerization, have also been found in another extremely important and ubiquitous transcriptional corepressor, namely, Sin3 (49). This protein has multiple paired amphipathic α-helices, some of which have been implicated in protein-protein interactions. Sin3 is believed to be a component of a high-molecular-mass corepressor complex found in many (perhaps all) eukaryotic cells (37). A critical feature of this complex is that it contains one or more polypeptides that function as histone deacetylases. It has therefore been proposed that this complex mediates transcriptional repression by catalyzing histone deacetylation, which could result in chromatin condensation. It will be extremely interesting to determine if histone deacetylation also plays a role in Gro-mediated repression.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Stephen Smale, David Eisenberg, and Ruben Flores-Saiib for their critical reading of the manuscript. We are also grateful to Jörk Zwicker and Robert Tjian for the baculovirus expressing M2-Gro and for advice on the purification of M2-Gro. We thank Alfred Fisher and Michael Caudy for pActGal4Gro, Michael Carey for pG5MLTG−, Arnold Berk for the wild-type p53 cDNA, Stephen Smale for assistance with the gel filtration, and Robert Yang for assistance with the yeast two-hybrid assays.

This work was supported by a grant to A.J.C. from the National Institutes of Health (GM44522).

REFERENCES

- 1.Akimaru H, Hou D X, Ishii S. Drosophila CBP is required for dorsal-dependent twist gene expression. Nat Genet. 1997;17:211–214. doi: 10.1038/ng1097-211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aronson B D, Fisher A L, Blechman K, Caudy M, Gergen J P. Groucho-dependent and -independent repression activities of Runt domain proteins. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:5581–5587. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.9.5581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bennett M J, Schlunegger M P, Eisenberg D. 3D domain swapping: a mechanism for oligomer assembly. Protein Sci. 1995;4:2455–2468. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560041202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bryan J K. Molecular weight of protein multimers from polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. Anal Biochem. 1977;78:513–519. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(77)90111-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Campos-Ortega J A. Mechanisms of early neurogenesis in Drosophila melanogaster. J Neurobiol. 1993;24:1305–1327. doi: 10.1002/neu.480241005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cantor C R, Schimmel P R. Biophysical chemistry. II. New York, N.Y: W. H. Freeman; 1980. pp. 560–562. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen J L, Tjian R. Reconstitution of TATA-binding protein-associated factor/TATA-binding protein complexes for in vitro transcription. Methods Enzymol. 1996;273:208–217. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(96)73021-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Clore G M, Omichinski J G, Sakaguchi K, Zambrano N, Sakamoto H, Appella E, Gronenborn A M. High-resolution structure of the oligomerization domain of p53 by multidimensional NMR. Science. 1994;265:386–391. doi: 10.1126/science.8023159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cordes S P, Barsh G S. The mouse segmentation gene Kr encodes a novel basic domain-leucine zipper transcription factor. Cell. 1994;79:1025–1034. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90033-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Courey A J, Holtzman D A, Jackson S P, Tjian R. Synergistic activation by the glutamine-rich domains of human transcription factor Sp1. Cell. 1989;59:827–836. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90606-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Courey A J, Huang J. The establishment and interpretation of transcription factor gradients in the Drosophila embryo. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1995;1261:1–18. doi: 10.1016/0167-4781(94)00234-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Courey A J, Tjian R. Analysis of Sp1 in vivo reveals multiple transcriptional domains, including a novel glutamine-rich activation motif. Cell. 1988;55:887–898. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90144-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Delidakis C, Artavanis-Tsakonas S. The Enhancer of split [E(spl)] locus of Drosophila encodes seven independent helix-loop-helix proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:8731–8735. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.18.8731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Depinho R A, Legouy E, Feldman L B, Kohl N E, Yancopoulos G D, Alt F W. Structure and expression of the murine N-myc gene. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1986;83:1827–1831. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.6.1827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dubnicoff T, Valentine S A, Chen G, Shi T, Lengyel J A, Paroush Z, Courey A J. Conversion of dorsal from an activator to a repressor by the global corepressor Groucho. Genes Dev. 1997;11:2952–2957. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.22.2952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fisher A L, Ohsako S, Caudy M. The WRPW motif of the Hairy-related basic helix-loop-helix repressor proteins acts as a 4-amino-acid transcription repression and protein-protein interaction domain. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:2670–2677. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.6.2670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Friedman P N, Chen X, Bargonetti J, Prives C. The p53 protein is an unusually shaped tetramer that binds directly to DNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:3319–3323. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.8.3319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gething M-J, McCammon K, Sambrook J. Protein folding and intracellular transport: evaluation of conformational changes in nascent exocytotic proteins. Methods Cell Biol. 1989;32:185–207. doi: 10.1016/s0091-679x(08)61171-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Goddard A D, Yuan J Q, Fairbairn L, Dexter M, Borrow J, Kozak C, Solomon E. Cloning of the murine homolog of the leukemia-associated PML gene. Mamm Genome. 1995;6:732–737. doi: 10.1007/BF00354296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Grunstein M. Yeast heterochromatin: regulation of its assembly and inheritance by histones. Cell. 1998;93:325–328. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81160-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hartley D A, Preiss A, Artavanis-Tsakonas S. A deduced gene product from the Drosophila neurogenic locus, enhancer of split, shows homology to mammalian G-protein beta subunit. Cell. 1988;55:785–795. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90134-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Husain J, Lo R, Grbavec D, Stifani S. Affinity for the nuclear compartment and expression during cell differentiation implicate phosphorylated Groucho/TLE1 forms of higher molecular mass in nuclear functions. Biochem J. 1996;317:523–531. doi: 10.1042/bj3170523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jeffrey P D, Gorina S, Pavletich N P. Crystal structure of the tetramerization domain of the p53 tumor suppressor at 1.7 angstroms. Science. 1995;267:1498–1502. doi: 10.1126/science.7878469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jimenez G, Paroush Z, Ish-Horowicz D. Groucho acts as a corepressor for a subset of negative regulators, including Hairy and Engrailed. Genes Dev. 1997;11:3072–3082. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.22.3072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kadonaga J T. Eukaryotic transcription: an interlaced network of transcription factors and chromatin-modifying machines. Cell. 1998;92:307–313. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80924-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Keleher C A, Redd M J, Schultz J, Carlson M, Johnson A D. Ssn6-Tup1 is a general repressor of transcription in yeast. Cell. 1992;68:709–719. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90146-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Knust E, Schrons H, Grawe F, Campos-Ortega J A. Seven genes of the Enhancer of split complex of Drosophila melanogaster encode helix-loop-helix proteins. Genetics. 1992;132:505–518. doi: 10.1093/genetics/132.2.505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Komachi K, Johnson A D. Residues in the WD repeats of Tup1 required for interaction with α2. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:6023–6028. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.10.6023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Koop K E, MacDonald L M, Lobe C G. Transcripts of Grg4, a murine groucho-related gene, are detected in adjacent tissues to other murine neurogenic gene homologues during embryonic development. Mech Dev. 1996;59:73–87. doi: 10.1016/0925-4773(96)00582-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lambright D G, Sondek J, Bohm A, Skiba N P, Hamm H E, Sigler P B. The 2.0 A crystal structure of a heterotrimeric G protein. Nature. 1996;379:311–319. doi: 10.1038/379311a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Leon C, Lobe C G. Grg3, a murine Groucho-related gene, is expressed in the developing nervous system and in mesenchyme-induced epithelial structures. Dev Dyn. 1997;208:11–24. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0177(199701)208:1<11::AID-AJA2>3.0.CO;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mallo M, Franco del Amo F, Gridley T. Cloning and developmental expression of Grg, a mouse gene related to the groucho transcript of the Drosophila Enhancer of split complex. Mech Dev. 1993;42:67–76. doi: 10.1016/0925-4773(93)90099-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Neer E J, Schmidt C J, Nambudripad R, Smith T F. The ancient regulatory-protein family of WD-repeat proteins. Nature. 1994;371:297–300. doi: 10.1038/371297a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Palaparti A, Baratz A, Stifani S. The Groucho/transducin-like enhancer of split transcriptional repressors interact with the genetically defined amino-terminal silencing domain of histone H3. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:26604–26610. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.42.26604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Parkhurst S M. Groucho: making its Marx as a transcriptional co-repressor. Trends Genet. 1998;14:130–132. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(98)01407-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Paroush Z, Finley R, Jr, Kidd T, Wainwright S M, Ingham P W, Brent R, Ish-Horowicz D. Groucho is required for Drosophila neurogenesis, segmentation, and sex determination and interacts directly with hairy-related bHLH proteins. Cell. 1994;79:805–815. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90070-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pazin M J, Kadonaga J T. What’s up and down with histone deacetylation and transcription? Cell. 1997;89:325–328. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80211-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pinto M, Lobe C G. Products of the grg (Groucho-related gene) family can dimerize through the amino-terminal Q domain. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:33026–33031. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.51.33026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Preiss A, Hartley D A, Artavanis-Tsakonas S. The molecular genetics of Enhancer of split, a gene required for embryonic neural development in Drosophila. EMBO J. 1988;7:3917–3927. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1988.tb03278.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rushlow C A, Hogan A, Pinchin S M, Howe K M, Lardelli M, Ish-Horowicz D. The Drosophila hairy protein acts in both segmentation and bristle patterning and shows homology to N-myc. EMBO J. 1989;8:3095–3103. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1989.tb08461.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shirokawa J M, Courey A J. A direct contact between the Dorsal rel homology domain and Twist may mediate transcriptional synergy. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:3345–3355. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.6.3345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Siegel L M, Monty K J. Determination of molecular weights and frictional ratios of proteins in impure systems by use of gel filtration and density gradient centrifugation. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1966;112:346–362. doi: 10.1016/0926-6585(66)90333-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sondek J, Bohm A, Lambright D G, Hamm H E, Sigler P B. Crystal structure of a G-protein beta gamma dimer at 2.1A resolution. Nature. 1996;379:369–374. doi: 10.1038/379369a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Stifani S, Blaumueller C M, Redhead N J, Hill R E, Artavanis-Tsakonas S. Human homologs of a Drosophila enhancer of split gene product define a novel family of nuclear proteins. Nat Genet. 1992;2:119–127. doi: 10.1038/ng1092-119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tata F, Hartley D A. The role of the enhancer of split complex during cell fate determination in Drosophila. Dev Suppl. 1993;1993:139–148. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Valentine S A, Chen G, Shandala T, Fernandez J, Mische S, Saint R, Courey A J. Dorsal-mediated repression requires the formation of a multiprotein repression complex at the ventral silencer. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:6584–6594. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.11.6584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.van Straaten F, Muller R, Curran T, van Beveren C, Verma I M. Complete nucleotide sequence of a human c-onc gene: deducted amino acid sequence of the human c-fos protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1983;80:3183–3187. doi: 10.1073/pnas.80.11.3183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Varanasi U S, Klis M, Mikesell P B, Trumbly R J. The Cyc8 (Ssn6)-Tup1 corepressor complex is composed of one Cyc8 and four Tup1 subunits. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:6707–6714. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.12.6707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wang H, Clark I, Nicholson P R, Herskowitz I, Stillman D J. The Saccharomyces cerevisiae SIN3 gene, a negative regulator of HO, contains four paired amphipathic helix motifs. Mol Cell Biol. 1990;10:5927–5936. doi: 10.1128/mcb.10.11.5927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Williams F E, Trumbly R J. Characterization of TUP1, a mediator of glucose repression in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell Biol. 1990;10:6500–6511. doi: 10.1128/mcb.10.12.6500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wolf E, Kim P S, Berger B. Multicoil: a program for predicting two and three stranded coiled coils. Protein Sci. 1997;6:1179–1189. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560060606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yen T J, Li G, Schaar B T, Szilak I, Cleveland D W. CENP-E is a putative kinetochore motor that accumulates just before mitosis. Nature. 1992;359:536–539. doi: 10.1038/359536a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Younger-Shepherd S, Vaessin H, Bier E, Jan L Y, Jan Y N. deadpan, an essential pan-neural gene encoding an HLH protein, acts as a denominator in Drosophila sex determination. Cell. 1992;70:911–922. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90242-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]