Abstract

Cyclophilins are cis-trans-peptidyl-prolyl isomerases that bind to and are inhibited by the immunosuppressant cyclosporin A (CsA). The toxic effects of CsA are mediated by the 18-kDa cyclophilin A protein. A larger cyclophilin of 40 kDa, cyclophilin 40, is a component of Hsp90-steroid receptor complexes and contains two domains, an amino-terminal prolyl isomerase domain and a carboxy-terminal tetratricopeptide repeat (TPR) domain. There are two cyclophilin 40 homologs in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae, encoded by the CPR6 and CPR7 genes. Yeast strains lacking the Cpr7 enzyme are viable but exhibit a slow-growth phenotype. In addition, we show here that cpr7 mutant strains are hypersensitive to the Hsp90 inhibitor geldanamycin. When overexpressed, the TPR domain of Cpr7 alone complements both cpr7 mutant phenotypes, while overexpression of the cyclophilin domain of Cpr7, full-length Cpr6, or human cyclophilin 40 does not. The open reading frame YBR155w, which has moderate identity to the yeast p60 homolog STI1, was isolated as a high-copy-number suppressor of the cpr7 slow-growth phenotype. We show that this Sti1 homolog Cns1 (cyclophilin seven suppressor) is constitutively expressed, essential, and found in protein complexes with both yeast Hsp90 and Cpr7 but not with Cpr6. Cyclosporin A inhibited Cpr7 interactions with Cns1 but not with Hsp90. In summary, our findings identify a novel component of the Hsp90 chaperone complex that shares function with cyclophilin 40 and provide evidence that there are functional differences between two conserved sets of Hsp90 binding proteins in yeast.

Cyclophilin 40 is one of several protein components of the Hsp90 protein complex. Hsp90 has a dual function; it acts as a chaperone after heat shock to help fold denatured proteins and also maintains the activity of signalling proteins under normal conditions. Hsp90 and associated proteins function as large chaperone units that regulate several molecules involved in signal transduction, including oncogenic kinases and members of the steroid receptor family (reviewed in references 2 and 43). These Hsp90 complexes consist of several proteins, including Hsp70, p60, p48, p23, and a large immunophilin, which may be either FKBP52, FKBP54, or cyclophilin 40. Several of these proteins have recently been shown to have chaperone activity in vitro (4, 22, 48).

Interactions between the components of the Hsp90 chaperone complex and their substrates are highly ordered and very dynamic. The order of assembly of these complexes with the progesterone receptor has been determined from reconstitution experiments in cell-free lysates (53, 54). First, Hsp70 binds the progesterone receptor, forming an early complex. Next, the progesterone receptor is found in an intermediate complex containing Hsp90, Hsp70, and p60. The trimeric Hsp90-Hsp70-p60 complex is soon displaced from the progesterone receptor by a preformed Hsp90-immunophilin-p23 complex. In this mature complex, the progesterone receptor is maintained in a state competent to bind hormone. If the receptor does not bind steroid, it is released from the mature complex and starts the association-dissociation cycle again. Recently, it has been shown that if the Hsp90 substrate is locked in a complex with Hsp90 and is not released, it is targeted for degradation by the proteasome (48). This study used the Hsp90 inhibitor geldanamycin, an antiproliferative agent that may find use as a novel chemotherapy agent. It has been previously suggested that geldanamycin blocks the binding of p23 to the Hsp90-immunophilin complex (59), which may improperly stabilize interactions between this complex and target proteins, thus stimulating degradation. Two recent studies show that geldanamycin inhibits binding of a yeast p23 homolog to yeast Hsp90 (1, 19).

By Hsp90 affinity chromatography and heterologous coexpression of the steroid receptor and a reporter gene under control of a steroid response element in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae, it was shown that the Hsp90 complex is biochemically and functionally conserved in S. cerevisiae (6, 8, 25, 36, 37, 42). Previous studies and the recent completion of the yeast genome sequencing project have identified genes encoding other proteins found in Hsp90 complexes. There are two HSP90 homologs in yeast, HSP82 and HSC82; HSC82 is expressed constitutively at high level and is moderately induced by heat shock, whereas HSP82 is expressed constitutively at a much lower level but is much more strongly induced by heat shock (3). Yeast strains require at least one copy of either HSP82 or HSC82 for viability. STI1, the yeast p60 homolog, physically and genetically interacts with HSP90, and mutations in STI1 affect HSP90 functions in vivo (9, 16, 39). In addition, several HSP70 homologs are found in S. cerevisiae (38). A yeast p23 homolog, Sba1, has also recently been identified (1, 19). There are two cyclophilin 40 genes in yeast, CPR6 and CPR7 (8, 15–17, 57). The Cpr6 and Cpr7 cyclophilins share 47 and 35% identity with human cyclophilin 40, respectively, and 41% identity with each other. All of the cyclophilin 40 homologs have in common an amino-terminal peptidyl-prolyl isomerase domain and a carboxy-terminal tetratricopeptide repeat (TPR) domain. TPR domains are loosely conserved repeats of roughly 34 amino acids that are found in several proteins that interact with Hsp90; the TPR domain of cyclophilin 40 mediates its binding to Hsp90 (13, 16, 41, 44). Yeast strains lacking cpr6 or cpr7, alone or in combination, are viable. cpr7 mutant strains, however, exhibit a slow-growth phenotype, while cpr6 mutant strains do not (15–17, 57).

Here we have further characterized the yeast cyclophilin 40 homologs. We find that cpr7 mutant strains are hypersensitive to the Hsp90 inhibitor geldanamycin (59). Mutant forms of the cyclophilin 40 homolog Cpr7 were analyzed to determine the unique features required for function in vegetative growth and geldanamycin resistance. The TPR domain of Cpr7 alone, when overexpressed, restores normal growth rate and geldanamycin resistance in both cpr7 and cpr6 cpr7 null mutant strains. Neither CPR6 nor the human cyclophilin 40 gene can functionally replace CPR7. In addition, the TPR domain did not have any dominant negative effect when overexpressed in a wild-type strain. We also found that transcription of the CPR6 gene is significantly induced by heat shock, whereas expression of CPR7 is not.

A novel yeast gene with homology to the yeast p60 homolog STI1 was isolated as a high-copy-number suppressor of the cpr7 slow-growth phenotype and has been named CNS1, for cyclophilin seven suppressor. When overexpressed, CNS1 complements both the slow growth and the geldanamycin sensitivity of both cpr7 single-mutant and cpr6 cpr7 double-mutant strains. CNS1 is required for viability in yeast, and the lethality of a Δcns1 null mutant strain is not rescued by overexpression of STI1, CPR6, CPR7, HSP90, or other genes implicated in Hsp90 functions. Unlike its homolog STI1, CNS1 is not transcriptionally regulated by heat shock. Finally, we show that the Cns1 protein is found in protein-protein complexes containing yeast Hsp90 and the yeast cyclophilin 40 homolog Cpr7 but not the Cpr6 cyclophilin. Taken together, our findings and previous studies reveal that the components of the Hsp90-associated chaperone machinery are duplicated in yeast and that one partner of each pair is heat inducible and nonessential (HSC82, CPR6, and STI1) whereas the other partner is constitutive and often more important for vegetative growth (HSC82, CPR7, and CNS1).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Media and strains.

Media were prepared as described in reference 49. Medium containing geldanamycin (National Cancer Institute) was prepared by adding a sterile stock of geldamycin in dimethyl sulfoxide to autoclaved medium at a final concentration of 20 μg/ml before pouring.

Strains used in this study were isogenic derivatives of JK93da (leu2-3,112 ura3-52 rme1 trp1 his4 HMLa [27]) with the following genotypic changes: KDY46, Δcpr6::G418; and KDY65, Δcpr7::G418 (strain construction described in reference 15). The Δcpr6 Δcpr7 double-mutant strain was constructed by crossing a MATα derivative of KDY46 to KDY65. The diploid was sporulated and dissected, and G418-resistant segregants were selected from tetrads with a 2 G418-resistant:2 G418-sensitive segregation pattern. The G418-resistant segregants were confirmed to be Δcpr6 Δcpr7 double mutants phenotypically (slow growth) and by PCR analysis of genomic DNA; the resulting Δcpr6::G418 Δcpr7::G418 strain was designated KDY66.5a.

Transformations and one-step gene disruptions.

Yeast transformation and one-step gene disruption were as described elsewhere (23, 45).

Cloning of CPR6 and CPR7.

The wild-type CPR6 and CPR7 genes were cloned by PCR using the following primers: for CPR6, 5′-GCCCGGATCCCCCACTGCATAAATGGACATCCGG-3′ and 5′-GCCCGTCGACCCCTTTATAGAACATAACTG-3′; for CPR7, 5′-GATCGGATCCGGGCGCTTCTTACCAAAGTTGCG-3′ and 5′-GGCGAATTCGGGTTGCAATTACCTGGC-3′. The resulting CPR7 PCR product was cleaved with EcoRI and BamHI and cloned into the corresponding sites of both the CEN (centromeric) URA3 vector pRS316 (50) and the 2μm URA3 vector YEplac195 (24) to generate plasmids pKS17 and pKS24, respectively. Similarly, to clone CPR6, the PCR product was cleaved with BamHI and SalI and cloned into the corresponding sites of pRS316 and YEp24 (5) to generate plasmids pKDw16 and pKDw10, respectively.

Construction of Cpr7 deletion mutant and Cpr6-Cpr7 fusion proteins.

The ΔCYP Cpr7, ΔTPR Cpr7, and Cpr6-Cpr7 hybrid proteins were engineered and expressed with CPR7 5′ and 3′ untranslated regions by PCR overlap mutagenesis as described in reference 28 by using the following primers: for ΔCYP Cpr7, 5′-TCCAACGCGATGTGGGAAAAA-3′ and 5′-CATAGTTTTTTCCCACATCGCGTT-3′; for ΔTPR Cpr7, 5′-ACAAGTAACTAATTACACTCCACAGTCGCTGATTCTAAC-3′ and 5′-GGAGTGTAATTAGTTACTTGTAAGGCT-3′; for Cpr6-Cpr7, 5′-TCTAGTCATCGCGTTGGATGTAGGTTG-3′, 5′-AACGCGATGACTAGACCTAAAAC T T T T-3′, 5′-TTTTTCCCACACGCCACAGTCATCAAT-3′, and 5′-TGTGGCGTGTGGGAAAAACTATGGGT-3′. Flanking primers for these constructs were 5′-GATCGGATCCGGGCGCTTCTTACCAAAGTTGCG-3′ and 5′-GGCGAATTCGGGTTGCAATTACCTGGC-3′. The resulting PCR products were cleaved with EcoRI and BamHI and cloned into the corresponding sites of both pRS316 (50) and YEplac195 (24).

The human cyclophilin 40 gene was fused to the 5′ and 3′ untranslated regions of CPR7 by gap repair as described elsewhere (40). Human cyclophilin 40 cDNA was amplified (cDNA clone provided by R. Handschumacher [31]) by using primers each with 39 bases of 5′ homology to either the 5′ or 3′ untranslated region of CPR7: 5′-ATTCTGAAAGGTGTTCGGCAGCAACCTACATCCAACGCGATGTCGCACCCGTCCCCCCAA-3′ and 5′-TTGGGTTATTTAATCTCAAAT TTCAGCCT TACAAGTAACTAACTAAGCAAACAT TT TTGCATA-3′. The wild-type yeast strain JK93da was cotransformed with the resulting PCR product and pKS17 (wild-type CPR7 plasmid) cleaved with SnaBI. The gap-repaired plasmid was rescued from yeast and sequenced, and expression of the human cyclophilin 40 clone was confirmed by Western blotting using antibodies that react specifically with human cyclophilin 40 (Affinity Bioreagents).

Northern analysis.

Wild-type (JK93da) and mutant (KDY98.4a Δcpr1::LEU2 Δcpr2::TRP1 cpr3::HIS3 Δcpr4::URA3 Δcpr5::LEU2 Δcpr6::G418 Δcpr7::G418 Δcpr8::MET15 fpr1::ADE2 Δfpr2::URA3 Δfpr3::URA3 Δfpr4::G418) yeast strains (15) were grown at 24°C to mid-log phase and heat shocked at 37°C, and samples were removed at 0, 2, 5, and 30 min. RNA was isolated as described elsewhere (47). Probes spanning the open reading frame for each gene were amplified by PCR and radiolabeled with [32P]dCTP by using a random primer DNA labeling kit (Boehringer Mannheim). Northern blot analysis was done as described in reference 46; levels of induction were normalized to actin message and quantified by PhosphorImager analysis.

Δcpr7::G418 high-copy-number suppressor screen.

A Δcpr7::G418 mutant strain was transformed with a high-copy-number URA3 yeast genomic library (provided by C. Alarcon), and transformants were selected on medium lacking uracil. Large colonies were streak purified, and plasmids were rescued from yeast transformants as described elsewhere (30) and amplified in Escherichia coli. The resulting plasmid DNA was used to transform both cpr7 and cpr6 cpr7 mutant strains to determine which suppressors were plasmid linked. Plasmids containing suppressing clones were classified by restriction mapping and PCR with primers to the CPR7 gene and then sequenced by Sequetech (Mountain View, Calif.). The yeast genome was then searched for homology to the cloned sequence (11), and it was determined that YBR155w was contained within the complementing clone for six isolates and the CPR7 gene in one isolate.

Cloning of STI1 and CNS1.

STI1 and CNS1 were cloned by PCR using the following primers: for CNS1, 5′-CGCGGATCCCCACTTTAATTTTAAATGCTT-3′) and 5′-CGTGGATCCCTGCATTTAGTACCGACAATA-3′; for STI1, 5′-CGCGGATCCCCCCGTCATAAGTTCCTATAC-3′ and 5′-CGTGGATCCTATGGCAGGCACATTACTAAA-3′. The CNS1 and STI1 PCR products were digested with BamHI and cloned into the corresponding sites of YEplac195 (24) to generate plasmids pKDw20 and pKDw19, respectively.

Construction of Δcns1::G418.

Disruption of the CNS1 open reading frame was done as described previously (35). Primers used to amplify the G418 resistance gene (56) were 5′-TATGTGCCAGGGCCAGGTGATCCTGAACTTCCACCCCAACTACAGCTGAAGCTTCGTACGC-3′ and 5′-TTGCTTATCCCACTTGGAAATCCACCCT TCACT TTCTACCT TGCATAGGCCACTAGTGGATCTG-3′. The resulting PCR product containing the G418 resistance gene open reading frame flanked by sequences identical to CNS1 was used to transform a diploid strain. G418-resistant colonies were screened by PCR to identify Δcns1::G418/CNS1 transformants.

Epitope tagging of Cns1.

The CNS1 gene was amplified by PCR with primers 5′-AAGCGATCCGCGGCCGCAATGAGCTCCGTTAACGCAAAT-3′ and 5′-AAGCTTGATGCGGCCGCACTGCATTTAGTACCGACAATA-3′. The PCR product was cleaved with NotI and cloned into the corresponding site of pYeF1 (12), which contains the hemagglutinin (HA) epitope under control of the GAL promoter, to result in fusion of the HA epitope to the amino terminus of CNS1. The resulting plasmid, pKDE3, expresses HA-Cns1 and restored viability in a Δcns1::G418 mutant strain, indicating that the HA epitope-tagged Cns1 is functional.

Antisera and immunoprecipitation experiments.

Immunoprecipitation experiments were done as described in reference 46. Wild-type (JK93da) yeast was transformed with pYeF1 (empty vector) or pKDE3 (HA-tagged Cns1), transformants were grown to an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 1 in the presence of galactose to induce Cns1 expression, and total-cell extracts were prepared as described elsewhere (7). Total-cell extracts were incubated for 12 h at 4°C with antibodies against HA coupled to Sepharose beads (Boehringer Mannheim), washed four times in lysis buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl, 100 mM KCl [pH 7.4]), and analyzed by Western blotting. Rabbit polyclonal antisera specific for Hsc82 and Cpr6 were generously provided by Susan Lindquist and Didier Picard, respectively. Mouse polyclonal antisera to yeast Hsc82 was generously provided by Avrom Caplan. Antisera against human cyclophilin 40 was purchased from Affinity Bioreagents.

GST-Cpr7.

The open reading frame of CPR7 was PCR amplified by using primers 5′-CGAGGATCCATGATTCAAGATCCCCTTGTA-3′ and 5′-CGAGGATCCTACTGCTAGGATGAGGCCCAG-3′. The resulting PCR product was cleaved with BamHI and cloned in the corresponding site of plasmid pGEX-2TK (52). Purification of the glutathione S-transferase (GST)–Cpr7 protein was performed as described previously (21). Yeast strains transformed with pYeF1 or pKDE3 were grown to an OD600 of 1. Protein extracts were made as described above and then incubated for 12 h at 4°C with either purified GST-Cpr7 or GST alone. In some cases, reaction mixtures contained 20 μM cyclosporin A (CsA) or 50 μM geldanamycin. Reaction products were then washed four times in lysis buffer and analyzed by Western blotting with mouse monoclonal antibodies against HA (Boehringer Mannheim) or mouse polyclonal antisera against yeast Hsc82 (provided by Avrom Caplan).

RESULTS

The TPR domain of the yeast cyclophilin 40 homolog Cpr7 is critical for function.

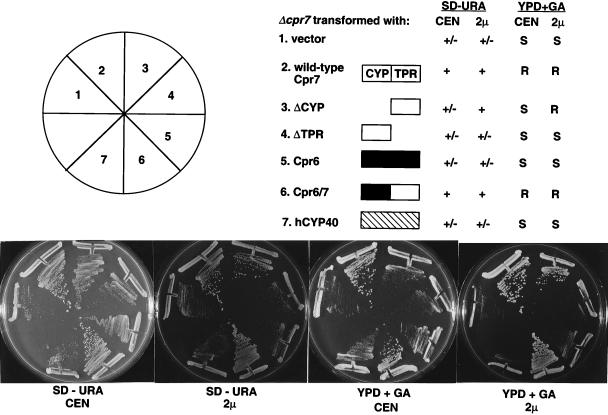

To determine which domains of the yeast cyclophilin 40 homolog Cpr7 are important for function, we engineered a series of deletion and fusion proteins and tested whether these restore normal growth in a cpr7 null mutant strain when expressed from either a low-copy-number CEN plasmid or a high-copy-number 2μm plasmid. As expected, expression of the wild-type CPR7 gene from either a CEN or 2μm plasmid complemented the slow-growth defect of the cpr7 mutation, restoring colony size to the wild-type level (Fig. 1). Interestingly, overexpression of the Cpr7 TPR domain alone from a 2μm plasmid (but not from a CEN plasmid) was sufficient to complement the cpr7 slow-growth mutant phenotype and restore colony size to wild-type (Fig. 1). In contrast, the Cpr7 cyclophilin domain failed to complement the cpr7 mutation, even when overexpressed (Fig. 1). These findings are in accord with a recent report by others (18). Expression of the yeast Cpr6 cyclophilin homolog, or human cyclophilin 40, also failed to complement the cpr7 mutation (Fig. 1). Western blot analysis with specific antisera confirmed that both Cpr6 and human cyclophilin 40 were expressed (data not shown). Finally, we note that when the Cpr7 TPR domain was fused to the cyclophilin domain of either Cpr7 (wild-type protein) or Cpr6 (Cpr6-7 hybrid protein), complementation was observed even with expression from a CEN plasmid. When overexpressed in a wild-type background, none of the cyclophilin 40 deletion or fusion proteins had any dominant negative effects on growth rate (data not shown).

FIG. 1.

The TPR domain is necessary and sufficient for Cpr7 function when overexpressed. The Δcpr7 mutant strain KDY65 was transformed with 2μm or CEN URA3 plasmids expressing wild-type Cpr7, the TPR domain of Cpr7 (ΔCYP), the cyclophilin domain of Cpr7 (ΔTPR), wild-type Cpr6, a hybrid protein containing the cyclophilin domain of Cpr6 fused to the TPR domain of Cpr7 (Cpr6/7), or human cyclophilin 40 (hCYP40). Expression of Cpr6 and human cyclophilin 40 was confirmed by Western blot (data not shown). Transformants were grown on synthetic dextrose medium lacking uracil (SD − URA) or on YPD medium containing 20 μg of geldanamycin per ml (YPD + GA) for 48 h at 30°C. The criteria used to establish complementation of the slow-growth, small-colony phenotype of the Δcpr7 mutant strain were twofold: first and most importantly, whether the introduced plasmid restored colony size to the wild-type level, and second, the overall level of growth. Findings presented are representative of several similar experiments. Open, solid, and hatched boxes, Cpr7, Cpr6, and human cyclophilin 40 protein sequences, respectively; +, wild-type colony size; +/−, smaller colony size and poorer growth; R and S, drug resistant and drug sensitive, respectively.

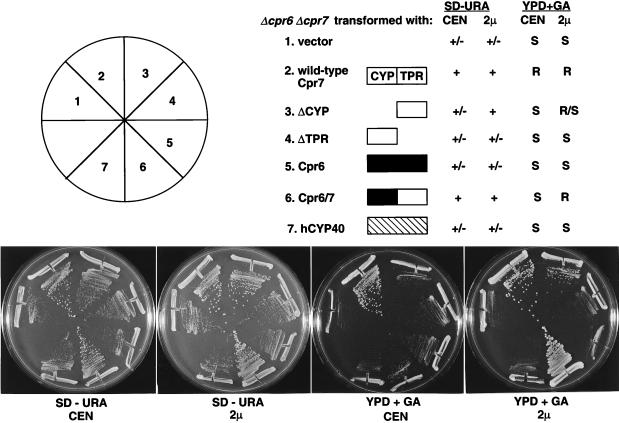

To test whether the TPR domain of Cpr7 required the presence of the Cpr6 protein to function, we repeated the preceding experiments in a cpr6 cpr7 double-mutant strain. When overexpressed, the TPR domain of Cpr7 still complemented the growth defect of the cpr6 cpr7 mutant strain (Fig. 2). In addition, the Cpr7 TPR domain alone restored normal growth in a cpr1 cpr6 cpr7 triple-mutant strain (CPR1 encodes the yeast cytoplasmic cyclophilin A); thus, no cytoplasmic cyclophilin domain is required for the TPR domain to complement the slow-growth defect of cpr7 (data not shown). Taken together, these findings indicate that it is the TPR domain of Cpr7 that is most critical for its in vivo function.

FIG. 2.

The TPR domain does not require the presence of Cpr6 to functionally replace Cpr7. The Δcpr6 Δcpr7 mutant strain KDY66.5a was transformed with 2μm or CEN URA3 plasmids expressing wild-type Cpr7, the TPR domain of Cpr7 (ΔCYP), the cyclophilin domain of Cpr7 (ΔTPR), wild-type Cpr6, a hybrid protein containing the cyclophilin domain of Cpr6 fused to the TPR domain of Cpr7 (Cpr6/7), or human cyclophilin 40 (hCYP40). Transformants were grown on synthetic dextrose media lacking uracil (SD − URA) or on YPD medium containing 20 μg of geldanamycin per ml (YPD + GA) for 48 h at 30°C. Criteria used to establish complementation of the Δcpr6 Δcpr7 mutant strain were as described in the legend to Fig. 1. Findings presented are representative of several similar experiments. Open, solid, and hatched boxes, Cpr7, Cpr6, and human cyclophilin 40 protein sequences, respectively; +, wild-type colony size; +/−, smaller colony size and poorer growth; R, R/S, and S, drug resistant, partially drug resistant, and drug sensitive, respectively.

cpr7 mutants are sensitive to the Hsp90 inhibitor geldanamycin.

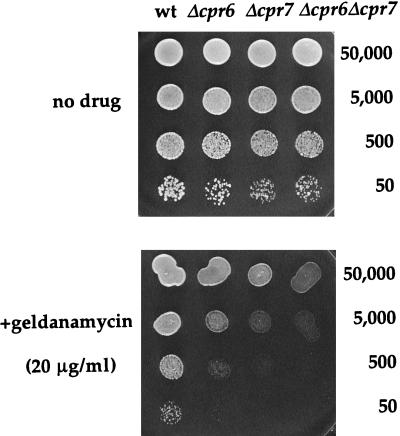

Geldanamycin is a potent antitumor drug whose target is Hsp90 (59). We found that cpr7 mutant strains, and also cpr6 and cpr6 cpr7 mutant strains, are hypersensitive to geldanamycin, indicating that in the absence of the yeast cyclophilin 40 homologs the cell is sensitive to perturbations in Hsp90 function (Fig. 3). These findings suggest that Cpr7 and Hsp90 normally interact, either physically, functionally, or both, in accord with previous genetic analyses that revealed a synthetic lethal interaction between yeast hsp90 and cpr7 mutations (16). We tested whether Cpr6, human cyclophilin 40, or any of the Cpr7 deletion proteins could restore growth to a cpr7 (or cpr6 cpr7) mutant strain on medium containing 20 μg of geldanamycin per ml. As in the growth rate studies, the Cpr6-Cpr7 fusion protein and the overexpressed Cpr7 TPR domain alone (but not Cpr6 or human cyclophilin 40) complemented the geldanamycin-sensitive phenotype of a cpr7 mutant strain (Fig. 1 and 2). This result provides further evidence that the slow-growth phenotype of cpr7 mutant strains is linked to defects in Hsp90 function.

FIG. 3.

Yeast mutants lacking cyclophilin 40 homologs are hypersensitive to the Hsp90 inhibitor geldanamycin. Isogenic wild-type (JK93da), Δcpr6 (KDY46), Δcpr7 (KDY65), and Δcpr6 Δcpr7 (KDY66.5a) mutant yeast strains were grown overnight in YPD medium, diluted to equal OD, and 10-fold serially diluted; 5-μl portions were plated on YPD medium containing no drug or 20 μg of geldanamycin per ml and incubated for 48 h at 30°C. Approximate numbers of cells plated are indicated to the right.

The overexpressed Cpr7 TPR domain only partially restored normal growth on medium containing geldanamycin in a cpr6 cpr7 double-mutant strain (Fig. 2). In addition, the Cpr6-Cpr7 fusion protein must be overexpressed to complement the geldanamycin sensitivity in the cpr6 cpr7 double-mutant strain, while in the cpr7 single mutant the fusion protein in low copy number was sufficient for full function. These results suggest that Cpr6 and Cpr7, though not functionally redundant, may to some extent overlap in function.

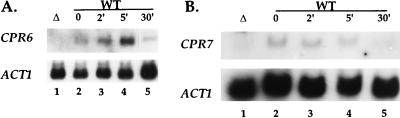

CPR6 expression is heat induced, whereas CPR7 expression is not.

Because several other proteins found in Hsp90 complexes are inducible by heat shock, we tested whether Cpr6 or Cpr7 expression is regulated by heat shock via Northern blot analysis. CPR6 was induced 3.3-fold after 5 min at 37°C (Fig. 4A), in accord with previous studies that have shown that Cpr6 protein levels are induced fourfold after heat shock at 39°C (57). In contrast, expression of the CPR7 gene was not induced by heat shock (Fig. 4B). In accord with these findings, the CPR6 gene promoter contains consensus heat shock response elements (57), whereas the CPR7 gene promoter does not. cpr6 and cpr7 single-mutant and cpr6 cpr7 double-mutant strains were not more sensitive to heat shock at 45 or 48°C than the isogenic wild-type strain (data not shown).

FIG. 4.

Cpr6 transcription is regulated by heat shock; Cpr7 expression is not. Total RNA was purified from wild-type (WT) and mutant (Δ; Δcpr1 Δcpr2 cpr3 Δcpr4 Δcpr5 Δcpr6 Δcpr7 Δcpr8 fpr1 Δfpr2 Δfpr3 Δfpr4 [15]) immunophilin strains and analyzed by Northern blot with probes specific to the gene indicated on the left. Lanes: 1, total RNA from the Δcpr1-8 Δfpr1-4 strain lacking CPR6 and CPR7 as a control; 2 through 5, total RNA from a wild-type yeast strain was isolated after 37°C heat shock for 0, 2, 5, or 30 min. Fold induction was determined by normalizing the amounts of immunophilin RNA to actin RNA by phosphorimaging.

cpr7 mutants are not suppressed by overexpression of known Hsp90-interacting proteins Ppt1, Cdc37, Cdc23, Ubc4, and Sun2.

We tested whether the yeast Hsp90 homologs can function as high-copy-number suppressors of the cpr7 slow-growth phenotype. Overexpression of Hsc82 or Hsp82 did not complement the slow-growth phenotype of a cpr7 mutant strain (data not shown). We also tested the following proteins that interact with Hsp90 or may be involved in Hsp90 functions: Ppt1, a serine/threonine phosphatase with four TPR domains that copurifies with the glucocorticoid receptor (10); Cdc37, the p50 component found in several Hsp90-kinase complexes (20, 32); Cdc23, which contains several TPR domains and is involved in ubiquitination and degradation of B-type mitotic cyclins (14, 51); Ubc4, a ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme with TPR domains which, when mutated, is synthetically lethal with cdc23 mutations (29); and Sun2, a component of the 26S proteasome (33). None of these proteins restored normal growth to a cpr7 mutant strain when overexpressed from a 2μm high-copy-number plasmid (data not shown).

Identification of a multicopy suppressor of cpr7 mutations as the p60/Sti1 homolog CNS1.

To identify the target(s) or novel components of the Cpr7-Hsp90 complex, a 2μm URA3 yeast genomic library was screened for genes that, when overexpressed, suppress the Δcpr7 slow-growth phenotype. We screened ∼55,000 Ura+ transformants on synthetic medium lacking uracil and identified eight potential suppressors. The plasmids containing the putative suppressor clones were rescued from the Δcpr7 mutant strain, amplified in E. coli, and retransformed into both a cpr7 single-mutant and a cpr6 cpr7 double-mutant strain. Seven of the eight rescued plasmids complemented the slow growth of both the cpr7 single and cpr6 cpr7 double-mutant strains and were further analyzed. By subcloning and sequencing, we determined that one of these clones contained the CPR7 gene, as expected. The remaining six clones were overlapping genomic sequences; all contained YBR155w, a previously uncharacterized open reading frame with moderate homology to STI1 (20% identity and 39% similarity [Fig. 5]). Another group has also independently identified YBR155w in a similar Δcpr7 suppressor screen (25a), and this open reading frame has been named CNS1, for cyclophilin seven suppressor.

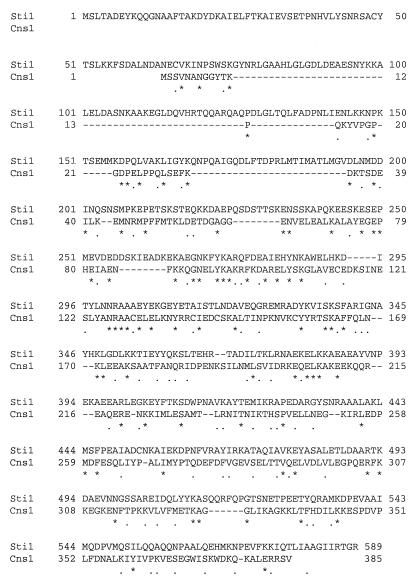

FIG. 5.

Alignment of Sti1 and Cns1 protein sequences by the Clustal method (MacVector software). Identical residues are marked with asterisks; similar residues are marked with periods.

Cns1 is an essential Sti1/p60 homolog that is not induced by heat shock.

The CNS1 gene was amplified by PCR and cloned in YEplac195, a 2μm URA3 vector; the resulting plasmid carrying the CNS1 gene alone was able to complement the slow-growth and geldanamycin-sensitive phenotypes of the Δcpr7 single-mutant and Δcpr6 Δcpr7 double-mutant strains. The CNS1 open reading frame was replaced by the G418 resistance gene in a wild-type diploid strain. The resulting heterozygous CNS1/Δcns1::G418 strain was sporulated and dissected, and 18 of 19 tetrads yielded two viable and two inviable segregants (a representative sample is shown in Fig. 6). All of the viable segregants were found to be G418 sensitive, consistent with the cosegregation of lethality and the Δcns1::G418 allele (data not shown).

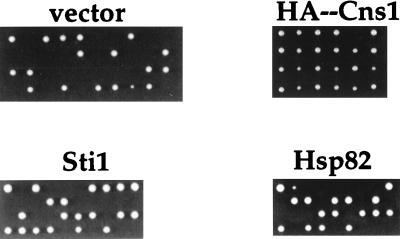

FIG. 6.

CNS1 is an essential gene. A CNS1/Δcns1::G418 diploid strain was transformed with high-copy-number 2μm plasmids alone (vector) or containing the HA epitope-tagged CNS1, wild-type STI1, or wild-type HSP82 gene. The transformed diploid strains were then sporulated and dissected; representative samples of the segregants are illustrated.

The CNS1/Δcns1::G418 heterozygous diploid was transformed with a plasmid containing the wild-type CNS1 and URA3 genes, sporulated, and dissected. The majority of the tetrads showed four viable and no inviable segregants (Fig. 6), which consisted of two G418-sensitive, 5-fluoro-orotic acid-resistant and two G418-resistant, 5-fluoro-orotic acid-sensitive segregants (data not shown). These findings indicate that CNS1 is an essential gene and that reintroduction of the wild-type CNS1 gene restores viability in the Δcns1::G418 mutant strain. Overexpression of CPR7, STI1, HSP82, HSC82, CDC23, UBC4, PPT1, or SUN2 did not restore viability of the Δcns1::G418 mutant (Fig. 6 and data not shown). In addition, overexpression of CNS1 did not suppress the conditional synthetic lethality exhibited by a Δsti1 mutation in combination with an hsp82 mutation (data not shown).

It was previously shown that STI1 is induced by heat shock (39). We examined CNS1 gene expression during heat shock by Northern analysis and found that transcription of the CNS1 gene was not induced at elevated temperatures (data not shown).

Cns1 is in protein complexes containing Hsc82 and Cpr7 but not Cpr6.

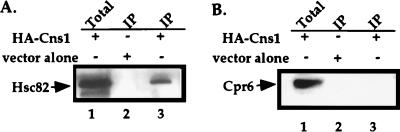

To examine physical interactions between Hsp90, Cns1, and cyclophilin 40, Cns1 was tagged with the HA epitope at its amino terminus (see Materials and Methods). The HA-tagged form of Cns1 complemented the lethality of a Δcns1::G418 null mutant (Fig. 6). Total-cell lysate was prepared from a wild-type yeast strain containing the HA-tagged Cns1. Cns1 was then immunoprecipitated with anti-HA antibodies coupled to Sepharose beads, and immunoprecipitates were analyzed by Western blotting. Hsc82 coimmunoprecipitated with the HA-Cns1 protein (Fig. 7A), indicating that Cns1 and Hsc82 are present in protein-protein complexes and may directly interact. This observation and interpretation would be in accord with previous findings that Hsp90 is directly physically associated with the p60/Sti1 protein that shares sequence identity with Cns1. In contrast to Hsc82, the Cpr6 protein was not present in Cns1 immunoprecipitates (Fig. 7B). This observation would again be in accord with previous observations that Hsp90 can exist in distinct complexes with p60/Sti1 and Cpr6 in yeast (9) and mammalian cells (41, 44).

FIG. 7.

The yeast Hsp90 protein Hsc82 and the p60/Sti1 homolog Cns1 are present in protein-protein complexes. Cellular lysates were incubated with anti-HA antibodies coupled to Sepharose beads, washed four times in lysis buffer, and then analyzed by Western blotting with antibodies to Hsc82 (A) or Cpr6 (B). Lanes: 1, total-cell extract control; 2, wild-type extract (immunoprecipitate [IP]) containing the empty plasmid pYeF1; 3, wild-type extract (IP) expressing the HA-tagged Cns1 from plasmid pYeF1.

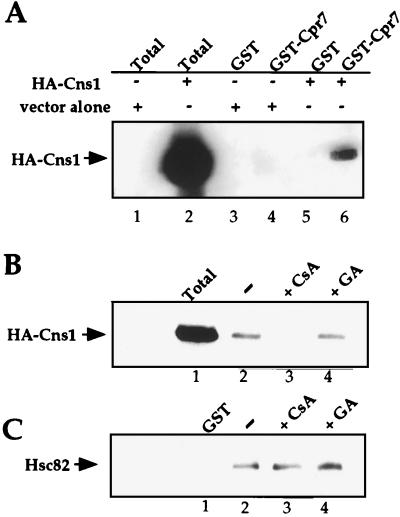

To examine interactions between cyclophilin 40, Cns1, and Cpr7 by a different approach, Cpr7 was fused to GST and expressed in bacteria, and GST-Cpr7 was adsorbed to glutathione-Sepharose beads. The resulting Cpr7 affinity matrix was then incubated with yeast total-cell extracts containing HA-Cns1. Interestingly, the HA-Cns1 protein interacted with the GST-Cpr7 fusion protein (Fig. 8A and B). Because Cpr6 was not detected in the Cns1 immunoprecipitate, this finding suggests that Cpr7 is distinguished from Cpr6 by its ability to interact, directly or indirectly, with the Cns1 protein. Western blot analysis revealed that Hsc82 was also specifically bound to the GST-Cpr7 affinity matrix (Fig. 8C), in accord with previous findings (16). Interestingly, CsA disrupted the Cpr7-Cns1 interaction (Fig. 8B), suggesting that the cyclophilin domain of Cpr7 may participate in binding of Cns1 to Cpr7. CsA did not inhibit Hsc82 binding to Cpr7 (Fig. 8C), in accord with previous findings that the TPR domain of Cpr7 is sufficient for binding to Hsc82 (16). Finally, the Hsp90 inhibitor geldanamycin had no effect on binding of either HA-Cns1 or Hsc82 to the GST-Cpr7 affinity matrix (Fig. 8B and C).

FIG. 8.

The yeast p60/Sti1 homolog Cns1 and the cyclophilin 40 homolog Cpr7 are present in protein-protein complexes. (A) Cellular lysates containing HA-Cns1 protein were incubated with GST-Cpr7 Sepharose beads (lanes 4 and 6) or GST beads alone (lanes 3 and 5), washed four times in lysis buffer, and analyzed by Western blotting with anti-HA antibodies to detect the HA-Cns1 protein. Lanes: 1 and 2, total cell extracts; 3 and 4, wild-type extracts containing the control plasmid pYeF1; 5 and 6, wild-type extract expressing the HA-tagged Cns1 protein from plasmid pYeF1. (B) Cellular lysates were incubated with GST-Cpr7 beads in the absence of drug (lane 2) or in the presence of 20 μM CsA (lane 3) or 50 μM geldanamycin (GA; lane 4), washed four times, and analyzed by Western blotting to detect HA-Cns1. Lane 1 contains total cell extract. (C) Cellular lysates were incubated with GST beads alone (lane 1) or with GST-Cpr7 beads in the absence of drug (lane 2) or the presence of 20 μM CsA (lane 3) or 50 μM geldanamycin (GA; lane 4), washed four times, and analyzed by Western blotting with mouse polyclonal antisera directed against the yeast Hsc82 protein.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we have further analyzed the structures and functions of components of the Hsp90-associated chaperone machinery. We performed a structure-function analysis of the yeast cyclophilin 40 homologs Cpr6 and Cpr7 that revealed the conserved TPR domain of Cpr7 is critical for function, demonstrated that yeast mutants lacking Cpr7 are hypersensitive to the Hsp90 inhibitor geldanamycin, and identified Cns1, a novel essential p60/Sti1 homolog that associates with Hsp90 and Cpr7.

The cyclophilin 40 proteins of yeast and mammals contain two conserved domains, an amino-terminal cyclophilin prolyl isomerase domain and a carboxy-terminal TPR domain (15–17, 57). We have found that the TPR domain of Cpr7 is critical for in vivo function, whereas the cyclophilin domain is largely dispensable. The TPR domain is known to be the critical domain for cyclophilin 40-Hsp90 interactions in both yeast and mammals (16, 41, 44). Because the TPR domain can complement in vivo and is the critical domain for Hsp90 interactions, Cpr7 and Hsp90 likely interact under normal physiological conditions via the Cpr7 TPR domain. While this report was in preparation, another group reported similar findings that the Cpr7 TPR domain is important for function (18).

We also find that yeast mutants lacking the cyclophilin 40 homolog Cpr7 are uniquely hypersensitive to the antitumor agent geldanamycin. Given previous studies that cpr7 and the yeast hsp90 homologs genetically interact and that geldanamycin binds to and perturbs Hsp90 function in mammalian cells and in yeast (1, 19, 26, 48, 55, 59), our findings provide additional evidence that Hsp90 function is compromised in cpr7 mutant strains. In addition, our findings open the door to a genetic dissection of geldanamycin action in yeast. Previous studies have revealed that Hsp90 and its associated partner proteins have been conserved, both in structure and in function, from yeast to mammals (3, 8, 9, 25, 39, 42); thus, our findings should be generally applicable to understanding Hsp90, cyclophilin 40, and p60/Sti1 functions in mammalian systems.

Our studies have also identified a previously uncharacterized open reading frame as a multicopy suppressor of the Δcpr7 mutation. The product of this suppressor gene, Cns1, shares limited sequence identity with Sti1, the yeast homolog of the mammalian p60 protein, which genetically and physically interacts with the yeast Hsp90 homologs. We have shown that Cns1 is found in protein complexes that contain Hsc82 and Cpr7. Others have shown that the Cns1 homologs, Sti1 in yeast and p60 in mammals, are also components of Hsp90 complexes (9, 53). It has also been shown that p60 and cyclophilin 40 are present in distinct complexes with Hsp90. p60 and cyclophilin compete, via their TPR domains, for Hsp90 binding and do not bind to each other (16, 41, 44). We have found, however, that the yeast Cns1 protein is present in complexes that contain the Cpr7 cyclophilin 40 homolog but not the Cpr6 cyclophilin. There are several different interpretations and implications of this result. First, there may subtle differences between the constitution of yeast and mammalian Hsp90 complexes. Studies that support a similarity between the protein content of yeast and mammalian Hsp90 complexes examined the presence of only Cpr6 and Sti1 (9). Second, because our experiments involved incubation of yeast extracts containing HA-Cns1 with bacterially expressed Cpr7 protein, Cns1 and Cpr7 need not directly interact and could, for example, be present in a ternary Cns1-Hsc82-Cpr7 complex in which Cns1 and Cpr7 are not in direct contact. However, our finding that cyclosporin A inhibits formation of Cpr7-Cns1 complexes, but not of Cpr7-Hsc82 complexes, suggests that Cpr7 directly interacts with both Cns1 and Hsc82. Finally, although the p60 homologs Sti1 and Cns1 are related, the level of sequence identity is low, the two genes are differentially regulated, and Cns1 is essential whereas Sti1 is not. Thus, Cns1 may have functions quite distinct from those of Sti1 that could involve direct protein-protein interactions with both Hsp90 and the cyclophilin 40 homolog Cpr7, whereas p60 and Sti1 have evolved to compete with cyclophilin 40 homologs for Hsp90 binding. Further study will be required to address these issues in detail.

Several of the proteins in Hsp90 complexes are encoded by two differentially regulated genes. For instance, the yeast homologs of Hsp90 (HSC82 and HSP82), Hsp70 (SSA1, SSA2, SSA3, and SSA4), cyclophilin 40 (CPR6 and CPR7), and p60 (STI1 and CNS1) are each encoded by at least two genes that are regulated differently at the transcriptional level, with one partner constitutively expressed and the other induced by heat shock (3, 38, 39, 57). Perhaps under normal conditions, expression of the constitutively expressed homolog is sufficient for physiological functions but growth at elevated temperatures requires higher levels of protein. Thus, it is more efficient to induce transcription of just one homolog. This is likely to be the case for the Hsp82-Hsc82 pair, which share 97% identity at the amino acid level and have seemingly overlapping functions. For more divergent sets such as Cpr6-Cpr7 (41% identity) and Sti1-Cns1 (20% identity and 39% similarity), the homologs may have partially overlapping but also unique functions. It is interesting that for the cyclophilin 40 and p60 homologs, the constitutively expressed gene has the more dramatic phenotype when mutated compared to the effects of mutating the heat-regulated homolog. One hypothesis consistent with these observations is that the stress-regulated homolog is less important during normal growth conditions. For instance, normally the constitutively expressed protein may have very transient interactions but under stressed conditions, chaperone-like interactions may persist, requiring a larger pool of protein; thus, the stress-regulated protein is induced. Alternatively, perhaps the range of substrates is broadened under stress conditions, which would also require an increase in chaperone protein levels. Examining Hsp90 complexes under stressed conditions by using reagents that detect specific homologs would help to address these alternative hypotheses.

Although our multicopy suppressor screen was exhaustive, just one suppressor of the Δcpr7 mutant phenotype was identified. Potential targets of the Hsp90 complex, however, were not identified in this high-copy-number suppressor screen. Perhaps targets were not isolated because there may be several, critical substrates for the Hsp90 complex, and overexpression of any one is not sufficient to restore a normal level of growth in the Δcpr7 mutant strain.

Possible functions and targets of cyclophilin 40 homologs have recently been identified by other studies. First, the Schizosaccharomyces pombe cyclophilin 40 homolog Wis2 was identified as a multicopy suppressor of a cdc25 wee1 win1 triple mutant, suggesting that the Wis2 cyclophilin may be involved in progression from the G2 phase to mitosis (58). Second, mammalian cyclophilin 40 has been shown to bind to and negatively regulate DNA binding by the c-Myb transcription factor (34). While the in vivo significance of this observation remains to be explored, an interesting finding was that the cyclophilin domain was required for inhibition of c-myb DNA binding activity; this is in contrast to our finding that the Cpr7 cyclophilin domain is not critical for in vivo function in yeast but may be in accord with our observation that the cyclophilin domain may be involved in high-affinity binding of Cpr7 to Cns1. Finally, in the cases of both Wis2 and c-Myb, a role for Hsp90 or other Hsp90-associated proteins remains to be elucidated.

Why does overexpression of the CNS1 gene suppress the cpr7 mutation? One model is that CNS1 overexpression makes formation of an initial Hsp90 complex (Hsp70-Hsp90-Cns1) more efficient. Alternatively, when overexpressed, Cns1 may substitute for Cpr7 in the mature Hsp90 complex (Hsp90-p23-immunophilin). Finally, our findings suggest that Cpr7 and Cns1 may be present simultaneously in the same Hsp90 complexes, and thus overexpression of one component might compensate for the loss of a different component of the complex. It is especially intriguing that while the components of the Hsp90 complex are duplicated, some components are significantly divergent. In this regard, Cns1 is quite divergent from its homolog Sti1, and further studies will be required to further address the unique or shared features of these distinct Hsp90-associated components.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Avrom Caplan, Sue Lindquist, Didier Picard, Don McDonnell, Robert Handschumacher, and the National Cancer Institute for providing plasmids, antisera, materials, and strains, Rick Gaber and Avrom Caplan for communicating results prior to publication, Lora Cavallo for superb technical assistance, and Mike Lorenz and John C. Matese for helpful discussions.

This work was supported in part by RO1 grants AI39115 and AI41937 from the NIAID to J.H. and M.E.C. and by KO1 award CA77075 from the NCI to M.E.C. J.H. is an assistant investigator of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bohen S P. Genetic and biochemical analysis of p23 and ansamycin antibiotics in the function of Hsp90-dependent signaling proteins. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:3330–3339. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.6.3330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bohen S P, Yamamoto K R. Modulation of steroid receptor signal transduction by heat shock proteins. In: Morimoto R I, Tissieres A, Georgopoulos C, editors. The biology of heat shock proteins and molecular chaperones. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Press; 1994. pp. 313–334. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Borkovich K, Farrelly F W, Finkelstein D B, Taulien J, Lindquist S. hsp82 is an essential protein that is required in higher concentrations for growth of cells at higher temperatures. Mol Cell Biol. 1989;9:3919–3930. doi: 10.1128/mcb.9.9.3919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bose S, Weikl T, Bugl H, Buchner J. Chaperone function of Hsp90-associated proteins. Science. 1996;274:1715–1717. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5293.1715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Botstein D, Falco S C, Stewart S E, Brennan M, Scherer S, Stinchcomb D T, Struhl K, Davis R W. Sterile host yeasts (SHY): a eukaryotic system of biological containment for recombinant DNA experiments. Gene. 1979;8:17–24. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(79)90004-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Caplan A J. Yeast molecular chaperones and the mechanism of steroid hormone action. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 1997;8:271–276. doi: 10.1016/s1043-2760(97)00079-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cardenas M, Hemenway C, Muir R S, Ye R, Fiorentino D, Heitman J. Immunophilins interact with calcineurin in the absence of exogenous immunosuppressive ligands. EMBO J. 1994;13:5944–5957. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06940.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chang H-C J, Lindquist S. Conservation of Hsp90 macromolecular complexes in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:24983–24988. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chang H-C J, Nathan D F, Lindquist S. In vivo analysis of the Hsp90 cochaperone Sti1 (p60) Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:318–325. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.1.318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen M-S, Silverstein A M, Pratt W B, Chinkers M. The tetratricopeptide repeat domain of protein phosphatase 5 mediates binding to glucocorticoid receptor heterocomplexes and acts as a dominant negative mutant. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:32315–32320. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.50.32315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cherry J M, Adler C, Ball C, Dwight S, Chervitz S, Juvik G, Roe T, Weng S, Botstein D. Saccharomyces genome database. 1997. http: //genome-www.stanford.edu/Saccharomyces/October http: //genome-www.stanford.edu/Saccharomyces/October 9, 1997. 9, 1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cullin C, Minvielle-Sebastia L. Multipurpose vectors designed for the fast generation of N- or C-terminal epitope-tagged proteins. Yeast. 1994;10:105–112. doi: 10.1002/yea.320100110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Das A K, Cohen P T W, Barford D. The structure of the tetratricopeptide repeats of protein phosphatase 5: implications for TPR-mediated protein-protein interactions. EMBO J. 1998;17:1192–1199. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.5.1192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Deshaies R J. Make it or break it: the role of ubiquitin-dependent proteolysis in cellular regulation. Trends Cell Biol. 1995;5:428–434. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(00)89102-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dolinski K, Muir R S, Cardenas M E, Heitman J. All cyclophilins and FK506 binding proteins are, individually and collectively, dispensable for viability in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:13093–13098. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.24.13093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Duina A A, Chang H C, Marsh J A, Lindquist S, Gaber R F. A cyclophilin function in Hsp-90 dependent signal transduction. Science. 1996;274:1713–1715. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5293.1713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Duina A A, Marsh J A, Gaber R F. Identification of two cyp-40-like cyclophilins in Saccharomyces cerevisiae, one of which is required for normal growth. Yeast. 1996;12:943–952. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0061(199608)12:10<943::aid-yea997>3.0.co;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Duina A A, Marsh J A, Kurtz R B, Chang H-C J, Londquist S, Gaber R F. The peptidyl-prolyl isomerase domain of the Cyp-40 cyclophilin 40 homolog Cpr7 is not required to support growth or glucocorticoid receptor activity in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:10819–10822. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.18.10819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fang Y, Fliss A E, Rao J, Caplan A J. SBA1 encodes a yeast Hsp90 cochaperone that is homologous to vertebrate p23 proteins. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:3727–3734. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.7.3727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fliss A E, Fang Y, Boschelli F, Caplan A J. Differential in vivo regulation of steroid hormone receptor activation by Cdc37p. Mol Biol Cell. 1997;8:2501–2509. doi: 10.1091/mbc.8.12.2501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Frangioni J V, Neel B G. Solubilization and purification of enzymatically active glutathione S-transferase (pGEX) fusion proteins. Anal Biochem. 1993;210:179–187. doi: 10.1006/abio.1993.1170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Freeman B C, Toft D O, Morimoto R I. Molecular chaperone machines: chaperone activities of the cyclophilin Cyp-40 and the steroid aporeceptor-associated protein p23. Science. 1996;274:1718–1720. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5293.1718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gietz R D, Schiestl R H, Willems A, Woods R A. Studies on the mechanism of high efficiency transformation of intact yeast cells. Yeast. 1995;11:355–360. doi: 10.1002/yea.320110408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gietz R D, Sugino A. New yeast-Escherichia coli shuttle vectors constructed with in vitro mutagenized yeast genes lacking six-base pair restriction sites. Gene. 1988;74:527–534. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(88)90185-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Godowski P J, Picard D, Yamamoto K R. Signal transduction and transcriptional regulation by glucocorticoid receptor-LexA fusion proteins. Science. 1988;241:812–816. doi: 10.1126/science.3043662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25a.Gaber, R. Personal communication.

- 26.Grenert J P, Sullivan W P, Fadden P, Haystead T A J, Clark J, Mimnaugh E, Krutzsch H, Ochel H J, Schulte T W, Sausville E, Neckers L M, Toft D O. The amino-terminal domain of heat shock protein 90 (hsp90) that binds geldanamycin is an ATP/ADP switch domain that regulates hsp90 conformation. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:23843–23850. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.38.23843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Heitman J, Movva N R, Hiestand P C, Hall M N. FK506-binding protein proline rotamase is a target for the immunosuppressive agent FK506 in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:1948–1952. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.5.1948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ho S N, Hunt H D, Horton R M, Pullen J K, Pease L R. Site-directed mutagenesis by overlap extension using the polymerase chain reaction. Gene. 1989;77:51–59. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(89)90358-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hochstrasser M. Protein degradation or regulation: Ub the judge. Cell. 1996;84:853–862. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81058-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hoffman C S, Winston F. A ten-minute DNA preparation from yeast efficiently releases autonomous plasmids for transformation of Escherichia coli. Gene. 1987;57:267–272. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(87)90131-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kieffer L J, Seng T W, Li W, Osterman D G, Handschumacher R E, Bayney R M. Cyclophilin-40, a protein with homology to the P59 component of the steroid receptor complex. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:12303–12310. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kimura Y, Rutherford S L, Miyata Y, Yahara I, Freeman B C, Yue L, Morimoto R I, Lindquist S. Cdc37 is a molecular chaperone with specific functions in signal transduction. Genes Dev. 1997;11:1775–1785. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.14.1775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kominami K-I, Okura N, Kawamura M, DeMartino G N, Slaughter C A, Shimbara N, Chung C H, Fujimuro M, Yokosawa H, Shimizu Y, Tanahashi N, Tanaka K, Toh-e A. Yeast counterparts of subunits S5a and p58 (S3) of the human 26S proteasome are encoded by two multicopy suppressors of nin1-1. Mol Biol Cell. 1997;8:171–187. doi: 10.1091/mbc.8.1.171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Leverson J D, Ness S A. Point mutations in v-myb disrupt a cyclophilin-catalyzed negative regulatory mechanism. Mol Cell. 1998;1:203–211. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80021-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lorenz M C, Muir R S, Lim E, McElver J, Weber S C, Heitman J. Gene disruption with PCR products in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Gene. 1995;158:113–117. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(95)00144-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mak P, McDonnell D P, Weigel N L, Schrader W T, O’Malley B W. Expression of functional chicken oviduct progesterone receptors in yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae) J Biol Chem. 1989;284:21613–21618. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Metzger D, White J H, Chambon P. The human oestrogen receptor functions in yeast. Nature. 1988;334:31–36. doi: 10.1038/334031a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Miao B, Davis J, Craig E A. The Hsp70 family—an overview. In: Gething M-J, editor. Guidebook to molecular chaperones and protein-folding catalysts. New York, N.Y: Oxford University Press; 1997. pp. 3–13. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nicolet C M, Craig E A. Isolation and characterization of STI1, a stress-inducible gene from Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell Biol. 1989;9:3638–3646. doi: 10.1128/mcb.9.9.3638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Orr-Weaver T L, Szostak J W, Rothstein R J. Yeast transformation: a model system for the study of recombination. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1981;78:6354–6358. doi: 10.1073/pnas.78.10.6354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Owens-Grillo J K, Stancato L F, Hoffmann K, Pratt W B, Krishna P. Binding of immunophilins to the 90 kDa heat shock protein (hsp90) via a tetratricopeptide repeat domain is a conserved protein interaction in plants. Biochemistry. 1996;35:15249–15255. doi: 10.1021/bi9615349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Picard D, Khursheed B, Garabedian M J, Fortin M G, Lindquist S, Yamamoto K R. Reduced levels of hsp90 compromise steroid receptor action in vivo. Nature. 1990;348:166–168. doi: 10.1038/348166a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pratt W B. The role of heat shock proteins in regulating the function, folding, and trafficking of the glucocorticoid receptor. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:21455–21458. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ratajczak T, Carrello A. Cyclophilin 40 (Cyp-40), mapping of its hsp90 binding domain and evidence that FKBP52 competes with Cyp-40 for hsp90 binding. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:2961–2965. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.6.2961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rothstein R. Targeting, disruption, replacement, and allele rescue: integrative DNA transformation in yeast. Methods Enzymol. 1991;194:281–301. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(91)94022-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Schmitt M E, Brown T A, Trumpower B L. A rapid and simple method for preparation of RNA from Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Nucleic Acids Res. 1990;18:3091–3092. doi: 10.1093/nar/18.10.3091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Schneider C, Sepp-Lorenzino L, Nimmesgern E, Ouerfelli O, Danishefsky S, Rosen N, Hartl F U. Pharmacologic shifting of a balance between protein refolding and degradation mediated by Hsp90. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:14536–14541. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.25.14536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sherman F. Getting started with yeast. Methods Enzymol. 1991;194:3–21. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(91)94004-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sikorski R S, Hieter P. A system of shuttle vectors and yeast host strains designed for efficient manipulation of DNA in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics. 1989;122:19–27. doi: 10.1093/genetics/122.1.19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sikorski R S, Michaud W A, Hieter P. p62cdc23 of Saccharomyces cerevisiae: a nuclear tetratricopeptide repeat protein with two mutable domains. Mol Cell Biol. 1993;13:1212–1221. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.2.1212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Smith D B, Johnson K S. Single-step purification of polypeptides expressed in E. coli as fusions with glutathione S-transferase. Gene. 1988;67:31–40. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(88)90005-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Smith D F. Dynamics of heat shock protein 90-progesterone receptor binding and the disactivation loop model for steroid receptor complexes. Mol Endocrinol. 1993;7:1418–1429. doi: 10.1210/mend.7.11.7906860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Smith D F, Whitesell L, Nair S C, Chen S, Prapapanich V, Rimerman R A. Progesterone receptor structure and function altered by geldanamycin, an Hsp90-binding agent. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:6804–6812. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.12.6804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Stebbins C E, Russo A A, Schneider C, Rosen N, Hartl F U, Pavletich N P. Crystal structure of an Hsp90-geldanamycin complex: targeting of a protein chaperone by an antitumor agent. Cell. 1997;89:239–250. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80203-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wach A, Brachat A, Pohlmann R, Philippsen P. New heterologous modules for classical or PCR-based gene disruptions in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast. 1994;10:1793–1808. doi: 10.1002/yea.320101310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Warth R, Briand P-A, Picard D. Functional analysis of the yeast 40 kDa cyclophilin Cyp40 and its role for viability and steroid receptor regulation. Biol Chem. 1997;378:381–391. doi: 10.1515/bchm.1997.378.5.381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Weisman R, Creanor J, Fantes P. A multicopy suppressor of a cell cycle defect in S. pombe encodes a heat shock-inducible 40 kDa cyclophilin-like protein. EMBO J. 1996;15:447–456. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Whitesell L, Mimnaugh E G, Costa B D, Myers C E, Neckers L M. Inhibition of heat shock protein HSP90-pp60v-src heteroprotein complex formation by benzoquinone ansamycins: essential role for stress proteins in oncogenic transformation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:8324–8328. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.18.8324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]