Abstract

Background

Malaria is extremely rare in the United States. Physicians should not only be familiar with signs and symptoms, but also be aware of the available resources at their respective institutions to be able to effectively treat it.

Presentation

52-year-old female presented with worsening generalized fatigue. Vitals were stable. Labs were significant for anemia and thrombocytopenia. Peripheral smear showed ring formed parasitic trophozoites consistent with Plasmodium falciparum. Due to unavailability of antimalarial agents at our hospital, the patient was transferred to a tertiary care center. Patient was started on IV artesunate therapy. Repeat smear after 3 days showed <1% parasitemia after 3 days and the patient was discharged with artemether/lumefantrine for 3 additional days, resulting in full recovery.

Conclusion

This case gives a unique insight into the challenges that hospitals in non-endemic regions may have to face, in terms of diagnosing malaria and having access to antimalarial agents.

Keywords: Malaria, Artesunate, Plasmodium falciparum, Non-endemic region

1. Introduction

Malaria is spread by the bite of the female Anopheles mosquito infected with the Plasmodium parasite. The majority of human infections are due to P. falciparum (90%) and severe illness is most often attributable to the same.1–3 The WHO estimates that annually, there are 247 million malaria cases worldwide in 2021 but only 2000 occur in the US. Of these, approximately 300 patients experience severe illness (predominantly related to P. falciparum) and 5–10 patients die.

Almost all cases of malaria in the US are acquired by traveling back from countries with known malaria transmission,1,2 but recent cases in Florida and Texas have highlighted that locally acquired mosquito-borne malaria is a possibility, even though this phenomenon was last described in 2003.4,5 Treatment depends on the infective species, likelihood of resistance to therapeutics depending on region of acquisition, and severity. IV Artesunate is the only drug available for treating severe malaria in the US, which used to be supplied by CDC. However, in September 2022, hospitals were asked to procure this drug commercially and have it stocked, thus adding another layer of complexity to the management of this deadly disease.6

Here, we describe a middle-aged woman, otherwise healthy, who presented to the emergency department of a rural community hospital in New Hampshire with features indicative of severe malaria. During treatment, interim therapy was provided until the recommended drugs were made available. The case underscores the importance of appropriate triage, obtaining a thorough history including travel, maintaining a high index of suspicion for this illness, and, most importantly, the availability of rapid diagnostics and adequate supply of appropriate therapeutic agents balanced against the unique challenges posed by resource limitations in a rural hospital.

2. Presentation

A 52-year-old female presented to the emergency department of a rural community hospital in New Hampshire, complaining of severe fatigue. Except for being diagnosed with COVID-19 three weeks prior to presentation, she was otherwise healthy and took no medications. She had not received any treatment for COVID-19 after self-diagnosing herself with a home test. Except for the fatigue, the rest of her symptoms had improved. On presentation, she was afebrile with a heart rate of 126 beats/min, blood pressure 102/58 mm Hg, respiratory rate 20 breaths/min, and saturating 98% on room air. Patient was alert, oriented, in no apparent distress and the physical exam was significant for scleral icterus. Laboratory tests are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Laboratory parameters of the patient.

| Laboratory test | Outcome |

|---|---|

| Hemoglobin (Hb) | 10.8 g/dl |

| Hematocrit | 31% |

| White Blood Cell count | 3600/microliter |

| Platelet count | 28,000/microliter |

| Sodium | 128 mEq/L |

| Potassium | 3.3 mEq/L |

| Creatinine | 0.79 mmol/L |

| Lactate | 6.5 mmol/L |

| ALT (Alanine transaminase) | 51 unit/L |

| AST (Aspartate transaminase) | 81 unit/L |

| Total bilirubin | 4.2 mg/dl |

Given significant abnormalities, laboratory tests were repeated after 5 h and showed a further drop in Hb to 7.8 g/dl and persistent thrombocytopenia. Given the anemia and thrombocytopenia, a peripheral blood smear was performed and the preliminary lab report indicated presence of numerous intraerythrocytic parasitic forms.

Unaware of her travel history and given the endemicity of Babesiosis in the New England region, the patient was initiated on oral atovaquone and azithromycin with plans for inpatient admission. Given her elevated lactate, tachycardia and borderline hypotension, fluid resuscitation was initiated for presumed sepsis secondary to a parasitic infection. When evaluated by the hospitalist, the patient provided additional history of recent travel to Sierra Leone to work in a gold mine as a part of her family business. She had not taken any chemoprophylaxis for malaria as a part of this trip. During the time of her travel, Sierra Leone was not known to have any active Ebola outbreaks either.

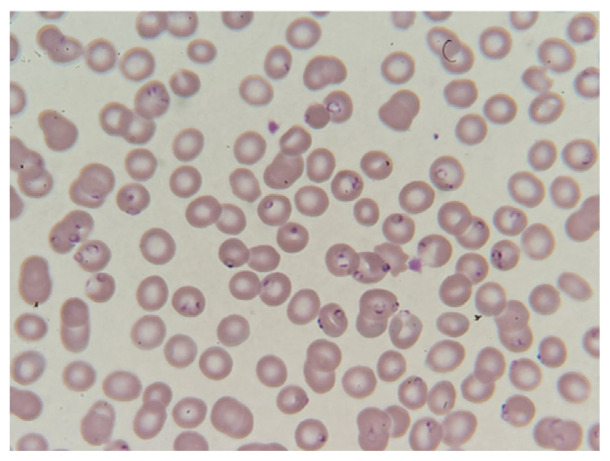

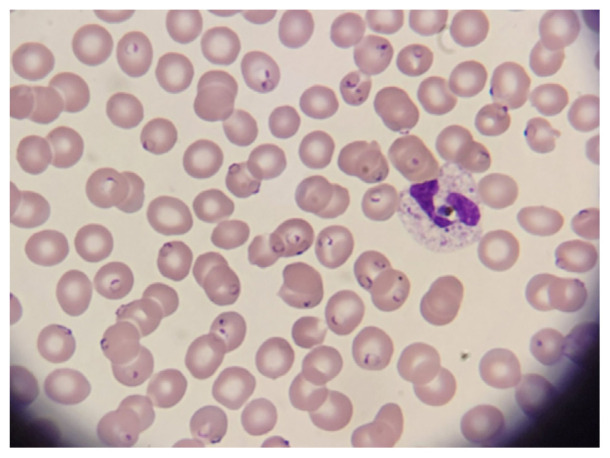

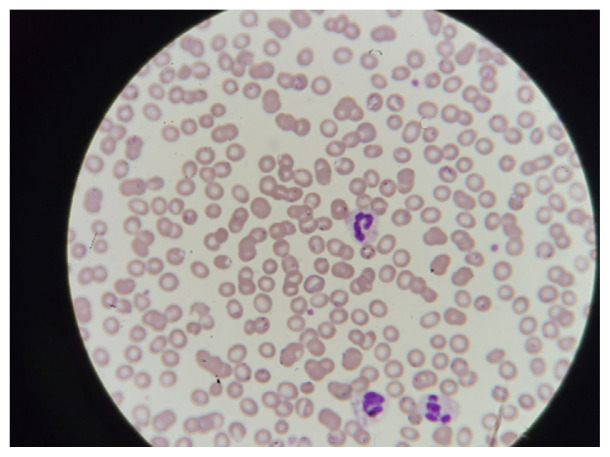

Given this history and her seeming to be confused during this interaction, the on call pathologist was asked to review the smear, who in turn reported, numerous ring-formed parasitic trophozoites, and occasional cluster schizont forms within RBCs, consistent with malaria and a very high parasite load estimated at 39.3% as shown in Fig. 1 Concurrent microbiology testing was positive for Plasmodium falciparum antigen. In the light of these findings, the patient was diagnosed with severe malaria due to Plasmodium falciparum (see Figs. 2 and 3).

Fig. 1.

Image of peripheral blood smear showing normochromic, normocytic anemia with numerous ring-formed parasitic trophozoites, and occasional cluster schizont forms within RBC consistent with malaria.

Fig. 2.

Image of peripheral blood smear showing normochromic, normocytic anemia with numerous ring-formed parasitic trophozoites, and occasional cluster schizont forms within RBC consistent with malaria.

Fig. 3.

Image of peripheral blood smear showing normochromic, normocytic anemia with numerous ring-formed parasitic trophozoites, and occasional cluster schizont forms within RBC consistent with malaria.

The current first-line agent for severe malaria or central nervous system malaria is parenteral Artesunate therapy.7,8 Unfortunately, given the lack of Infectious Diseases coverage at our hospital over the weekend, there was confusion regarding availability of antimalarials on campus and the process of acquiring it. We called the CDC hotline and were informed of the process to procure IV Artesunate and to start oral antimalarials in the interim. As the patient had a high parasite load with impending signs of deterioration, we initiated a prompt transfer to the tertiary academic medical center within our health system to help facilitate evaluation, diagnosis and treatment for the patient. Unfortunately, the tertiary facility also only had the oral antimalarial Artemether/Lumefantrine in stock, which they started, while awaiting a shipment of IV Artesunate from another facility within the region and the regional distributor.

Within 24 h of transfer, IV Artesunate was procured and initiated on the patient. Subsequent peripheral smears showed an improving parasite load. Given the patient's confusion, a non-contrast head CT was done, which showed no acute findings. Since the patient was already on IV Artesunate and because of severe thrombocytopenia, lumbar puncture was not done. Ophthalmology was consulted and diagnosed malaria retinopathy via dilated ophthalmologic examination, confirming severe malaria.

After 3 days of IV artesunate treatment, a repeat peripheral blood smear showed <1% parasitemia and artesunate was replaced with artemether/lumefantrine for three more days of treatment. Her vitals, clinical exam and blood counts improved and she was discharged on hospital day 6, fully recovered.

3. Discussion

Malaria is a disease caused by protozoan parasites plasmodium and is mainly seen in the tropical regions of the world where this protozoan is endemic. The vast majority of the new cases are seen in Sub Saharan Africa.9 Malaria is uncommon in the United States and is seen in approximately 2000 people per year, 80% of whom acquired the infection in Africa.10 The number of cases of malaria diagnosed in the United States increased from 614 cases in 1972–2161 cases in 2017.11 In 2023, the CDC reported locally acquired cases in Florida and Texas for the first time in 20 years.12

Malaria may prove to be an elusive diagnosis for those that do not routinely deal with it, for example, physicians that practice in non-endemic regions.9 Given increase in global travel, physicians need to maintain a high index of suspicion for it when evaluating fever in a returning traveler, especially in immigrants who may be visiting friends and relatives, as several factors may lead to reduced adherence to protective measures thus increasing their risk of acquiring illness.13 In this case, due to the lack of a thorough travel history and anchoring on an endemic illness like Babesiosis, malaria did not even feature on the initial list of differential diagnoses. Patients with severe malaria have a high mortality rate and timely diagnosis and treatment are extremely important for better outcomes.14–16 CDC has resources regarding various tools to help clinicians diagnose cases of malaria especially in a non-endemic region like the United States. One is through microscopic diagnosis to examine the species in blood smear, which is considered to be gold standard for laboratory confirmation. Other resources include use of antigen detection techniques using Rapid Diagnostic Tests (RDTs). Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) helps to detect parasitic nucleic acids may have a limited utility in acutely ill patients; however it is slightly more sensitive than smear microscopy. Lastly, using serology to detect antibodies against malarial parasites through indirect immunofluorescence (IFA) or enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), one can measure past exposure.17

Intravenous Artesunate is the recommended first line therapy for treatment of severe falciparum malaria in adults.7,8,17–19 In a meta-analysis, treatment with artesunate significantly reduced the risk of deaths in adults (risk ratio [RR] 0.61, 95% CI 0.50–0.75).20 In places where parenteral artesunate is not immediately available, patients should receive interim oral treatment.17

Until September 2022, CDC was the only source of IV Artesunate and providers managing active cases had to contact CDC for the same. However, since then, hospitals have been directed to stock their own supply of IV Artesunate, thus creating some challenges, especially for rural community hospitals in a non-endemic setting, where cost of the treatment course might be counter-productive to its estimated use.6 However, to avoid delays in treatment and facilitate safe patient care, instead of every facility procuring this drug, it may make sense for healthcare facilities to have the drug stocked at specific nodal sites for use across their own healthcare system or regional healthcare consortiums such that it can be transferred expeditiously thus enabling cost sharing, preventing drug wastage and enhancing the logistics of the same.

4. Conclusion

Malaria continues to predominantly be a travel-related illness in the US, with the majority of the cases being imported. However, given increasing international travel, climate change and rising incidence of locally-acquired cases, it is imperative for physicians to be familiar with its symptoms, maintain a high index of suspicion especially in someone with the appropriate risk factors such as travel to affected regions and be aware of rapid means to diagnose and treat these patients with appropriate therapeutics. This is especially important for those practicing in rural community settings in non-endemic regions as they may be faced with unique challenges as regards access to the means to diagnose and treat this infection and logistics supporting it, as described in this case.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: Authors confirm there is no conflict of interest.

Funding: No funding was obtained or provided in any manner.

References

- 1.WHO Guidelines for Malaria. World Health Organization; Geneva: [Google Scholar]

- 2.World malaria report 2021. [Accessed August 9, 2023]. https://www.who.int/teams/global-malaria-programme/reports/world-malaria-report-2021 .

- 3. White NJ, Pukrittayakamee S, Hien TT, Faiz MA, Mokuolu OA, Dondorp AM. Malaria. Lancet. 2014;383:723–735. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60024-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.CDC - Malaria - Malaria in Florida. 2023. [Accessed July 14, 2023]. https://www.cdc.gov/malaria/new_info/2023/malaria_florida.html .

- 5.Health Alert Network (HAN) - 00494. 2023. [Accessed August 4, 2023]. https://emergency.cdc.gov/han/2023/han00494.asp .

- 6.Discontinuation of CDC's Distribution of Intravenous Artesunate as Commercial Drug Is Widely Available in the United States. Medical Health Cluster - Clúster de Colegios y asociaciones de salud; 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Dondorp AM, Fanello CI, Hendriksen ICE, et al. Artesunate versus quinine in the treatment of severe falciparum malaria in African children (AQUAMAT): an open-label, randomised trial. Lancet. 2010;376:647–657. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61924-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kurth F, Develoux M, Mechain M, et al. Intravenous artesunate reduces parasite clearance time, duration of intensive care, and hospital treatment in patients with severe malaria in Europe: the TropNet severe malaria study. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;61:441–444. doi: 10.1093/cid/civ575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Jerrard DA, Broder JS, Hanna JR, et al. Malaria: a rising incidence in the United States. J Emerg Med. 2002;23:23–33. doi: 10.1016/s0736-4679(02)00457-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Daily JP, Minuti A, Khan N. Diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of malaria in the US: a review. JAMA. 2022;328:460–471. doi: 10.1001/jama.2022.12366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Mace KE, Lucchi NW, Tan KR. Malaria surveillance - United States, 2017. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2021;70:1–35. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.ss7002a1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.CDC - Malaria - Malaria in Florida. 2023. [Accessed July 25, 2023]. https://www.cdc.gov/malaria/new_info/2023/malaria_florida.html .

- 13. Walz EJ, Volkman HR, Adedimeji AA, et al. Barriers to malaria prevention in US-based travellers visiting friends and relatives abroad: a qualitative study of West African immigrant travellers. J Trav Med. 2019;26 doi: 10.1093/jtm/tay163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Balerdi-Sarasola L, Parolo C, Fleitas P, et al. Host biomarkers for early identification of severe imported Plasmodium falciparum malaria. Trav Med Infect Dis. 2023;54:02608. doi: 10.1016/j.tmaid.2023.102608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Mahittikorn A, Mala W, Wilairatana P, et al. Prevalence, antimalarial chemoprophylaxis and causes of deaths for severe imported malaria: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Trav Med Infect Dis. 2022;49:02408. doi: 10.1016/j.tmaid.2022.102408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bruneel F, Tubach F, Corne P, et al. Severe imported falciparummalaria: a cohort study in 400 critically ill adults. PLoS One. 2010;5:e13236. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0013236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cdc-Centers for Disease Control. Prevention: CDC - Malaria - Diagnosis & Treatment (United States) - Treatment (U.s.) - Guidelines for Clinicians (Part 1) 2009. Published Online First. 8 February. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lengeler C, Burri C, Awor P, et al. Community access to rectal artesunate for malaria (CARAMAL): a large-scale observational implementation study in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Nigeria and Uganda. PLOS Glob Public Health. 2022;2:e0000464. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgph.0000464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Dondorp A, Nosten F, Stepniewska K, Day N, White N. South East Asian Quinine Artesunate Malaria Trial (SEAQUAMAT) group: artesunate versus quinine for treatment of severe falciparum malaria: a randomised trial. Lancet. 2005;366:717–725. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67176-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Sinclair D, Donegan S, Isba R, Lalloo DG. Artesunate versus quinine for treating severe malaria. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;2012:CD005967. doi: 10.1002/14651858CD005967.pub4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]