Abstract

Native mass spectrometry (nMS) has emerged as a key analytical tool to study the organizational states of proteins and their complexes with both endogenous and exogenous ligands. Specifically, for membrane proteins, it provides a key analytical dimension to determine the identity of bound lipids and to decipher its effects on the observed structural assembly. We have recently developed an approach to study membrane proteins directly from intact and tunable lipid membranes where both the biophysical properties of the membrane and its lipid compositions can be customized. Extending this, we use our liposome-nMS platform to decipher the lipid specificity of membrane proteins through their multi-organelle trafficking pathways. To demonstrate this, we used VAMP2 and reconstituted it in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER), Golgi, synaptic vesicle (SV), and plasma membrane (PM) mimicking liposomes. By directly studying VAMP2 from these customized liposomes we show how the same transmembrane protein can bind to different sets of lipids in different organellar-mimicking membranes. Considering the cellular trafficking pathway of most eukaryotic integral membrane proteins involves residence in multiple organellar membranes, this study highlights how the lipid-specificity of the same integral membrane protein may change depending on the membrane context. Further, leveraging the capability of the platform to study membrane proteins from liposomes with curated biophysical properties, we show how we can disentangle chemical vs biophysical properties of individual lipids in regulating membrane protein assembly.

INTRODUCTION

The chemical interplay between membrane proteome and lipidome plays a central role in regulating all aspects of cellular biology in both health and disease. Using a chemically diverse arsenal of lipids, cells create membrane environments that modulate biogenesis, assembly, structure, and active conformational states of the embedded and associated membrane proteome1. This in turn controls a cell’s ability to sense and respond to a myriad of physicochemical stimuli and drive downstream signaling cascades. This chemical interplay between proteins and lipids can be broadly classified into two categories. In certain cases, specific lipids can directly bind to a target protein in a distinct binding site and regulate its conformational state2, functional assemblies3–5, or its ability to interact with downstream effector proteins6–8. From inducing specific functional conformational states of ion channels to regulating functional homomeric and heteromeric assemblies, there are abundant examples of this direct interaction2–4,6,9. In these cases, lipids act like endogenous ligands and modulate the structural/functional state of the protein through direct and specific binding. Alternatively, cells also organize their lipidome in a laterally heterogeneous manner to create membrane nanodomains that harbor specific biophysical properties such as membrane curvature, fluidity, tension, etc1,10–12. These bulk bilayer properties also can directly modulate all aspects of biogenesis, assembly state, and functions of membrane proteins. From curvature-induced oligomerization of BAR domain proteins to membrane tension-induced opening of ion channels13,14, examples of bulk bilayer properties regulating membrane proteins are also plentiful in biology. In these cases, instead of directly binding to proteins, lipids collectively exert specific membrane properties that regulate the functional organization states of membrane proteins and in turn the downstream signaling cascade. Hence, capturing this aspect of membrane protein–lipid interplay demands the ability to study their organization directly from a tunable lipid bilayer environment. The ability to tune the lipid bilayer both in terms of its lipid composition, as well as specific bilayer properties such as curvature, tension, fluidity, etc. enables not just detection of their membrane-embedded organization states but further elucidation of the key membrane properties that regulate these organizations.

Native mass spectrometry (nMS) has emerged as a key quantitative technique in determining the organization states of proteins and their ligands15–18. Recently, key orthogonal developments in single ion charge detection mass spectrometry19–22, gas phase mobility separations23–26, and a range of orthogonal fragmentation/dissociation approaches are collectively enabling routine breakage of the glass ceiling for how big we can go in the mass axis, how well resolved the masses are, and how precisely we can determine the stoichiometry and sub-assembly states4,27–33. Applications of this combined arsenal of nMS-technologies on membrane proteins have enabled several key discoveries about the organization states, assembly rules, role of specific lipids, and conformational reorganization of membrane proteins and their partners34–41. Nevertheless, a key bottleneck in nMS analysis of membrane proteins has been its limitation in studying them directly from lipid bilayers where both the composition and the bilayer property can be curated. This is because nMS analysis of membrane proteins typically demands prior disruption of the lipid membranes with detergents, or occasionally with other chemical (amphipole, bicelle) or mechanical means34–39,41–43. This in turn constrains the range of membrane protein complexes that can be studied using nMS and consequently limits our understanding of how cells regulate them through specific membrane properties, such as curvature, fluidity, tension, etc. Addressing this limitation, we have recently developed a platform that enables nMS analysis of target membrane proteins directly from intact and tunable lipid bilayers where both lipid compositions, as well as key membrane properties (fluidity, curvature, tension), can be quantitatively modified44. By directly subjecting these intact-customizable lipid membranes in nMS, we demonstrated the ability to precisely determine the organizational states of the embedded membrane proteins, their specifically bound lipids, and how specific membrane constituents regulate their oligomeric states. Extending this further, in this current work we first ask an intriguing question about membrane protein trafficking: how does the lipid binding specificity of the same transmembrane domain (TMD) change across its trafficking path? To answer this question, we took the example of VAMP2, a synaptic vesicle protein that drives vesicular fusion45,46, and showed how the same TMD binds to different sets of lipids in different liposomes mimicking different organelles. This leads us to our second question: how can we distinguish between the chemical and biophysical properties of specific lipids in regulating the formation of higher-order membrane protein assemblies? Addressing this, we used SemiSWEET as a model system to elucidate the role of specific lipid interactions on oligomerization.

EXPERIMENTAL SECTION

Materials

All lipids used in this study were purchased from Avanti Polar Lipids Inc. (Alabaster, AL). n-Octyl-β-D-glucopyranoside (OG) was purchased from CHEM-IMPEX INT’L INC. Spectra/Por 6–8 kD Molecular weight cut-off dialysis membrane was purchased from Fisher Scientific. Ammonium acetate solution was purchased from Millipore Sigma. Sephadex G-50 Fine was purchased from Cytiva. All other chemicals used in this study were purchased from Thermo Fisher.

Recombinant protein expression and purification

The recombinant v-SNARE (VAMP2) protein was purified as described in previous studies44. The protein was expressed in the E. coli BL21 strain using 0.5mM IPTG for 4 hours. The cells were lysed using a cell disruptor (Avestin, Ottawa, Canada) in HEPES buffer (25mM HEPES, 400mM KCl, 4% Triton X-100, 10% glycerol, pH 7.4) containing 1mM DTT. The samples were clarified using a 45Ti rotor (Beckman Coulter, Atlanta, GA) at 35,000 RPM for 30 minutes and subsequently incubated with Ni-NTA resin (Thermofisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) overnight at 4°C. The resin was washed with HEPES buffer supplemented with 25 mM imidazole, 1% octylglucoside (OG), and 1 mM DTT. The resin was incubated with SUMO protease in HEPES buffer supplemented with 1% OG and 1mM DTT overnight at 4°C, and the protein was collected as flow-through from the gravity flow column.

The SemiSWEET and AqpZ proteins were purified as described previously4,36. The proteins were expressed in Rosetta (DE3)pLysS cells, induced with IPTG, and grown at 37°C overnight except for SemiSWEET, which was grown at 22°C for 15 hours. The cells were harvested by centrifugation, resuspended in lysis buffer (20 mM Tris, 300 mM NaCl, pH 7.4 supplemented with protease inhibitor cocktail tablets), lysed using a cell disruptor (Avestin, Ottawa, Canada), and the membranes were pelleted by ultracentrifugation (100,000 g, 2 hours 15 minutes, 4°C). The membranes were homogenized in membrane resuspension buffer (20 mM Tris, 100 mM NaCl, 20% Glycerol, pH 7.4 with 2% (w/v) powder DDM) and left to tumble at 4°C for 2 hours. The samples were clarified by centrifugation (20,000 g, 40 minutes, 4°C) and filtered through 0.22 μm filters. The proteins were first purified by His-tag affinity chromatography and then cleaved from respective tags using appropriate protease. The proteins were further purified using reverse Ni chromatography and size exclusion chromatography with detergent exchange to OG for protein reconstitution into lipid vesicles.

LacY was purified as described previously47.

Preparation of native MS ready proteo- lipid vesicles

We used our previously developed protocol for preparing nMS-ready liposomes44. All VAMP2 studies are done from liposomes prepared through the density gradient float-up method. All other proteoliposomes were prepared using the Sephadex G50 column method. For SemiSWEET, three different lipid compositions were used and they are as follows - for Figure 4(a) and Figure 5(b): 67%DOPE, 23.2%DOPG, 9.8% 18:1Cardiolipin, for Figure 4(b): 70.9%DOPE, 27.1%DOPG, 2% 16:0–18:1DAG, and for Figure 4(c): 67%DOPE, 23.2%DOPG, 9.8% 18:0Dilysocardiolipin. To make high-curvature vesicles, DAG-containing vesicles were further passed through extrusion with a 50nm membrane filter. The experimental details of modulating curvature are described in the next section. LacY in Figure 5(d) was reconstituted in 67%DOPE, 23.2%DOPG, 9.8% 18:1Cardiolipin and AqpZ in Figure 5(f) was reconstituted in E. coli polar lipid extract.

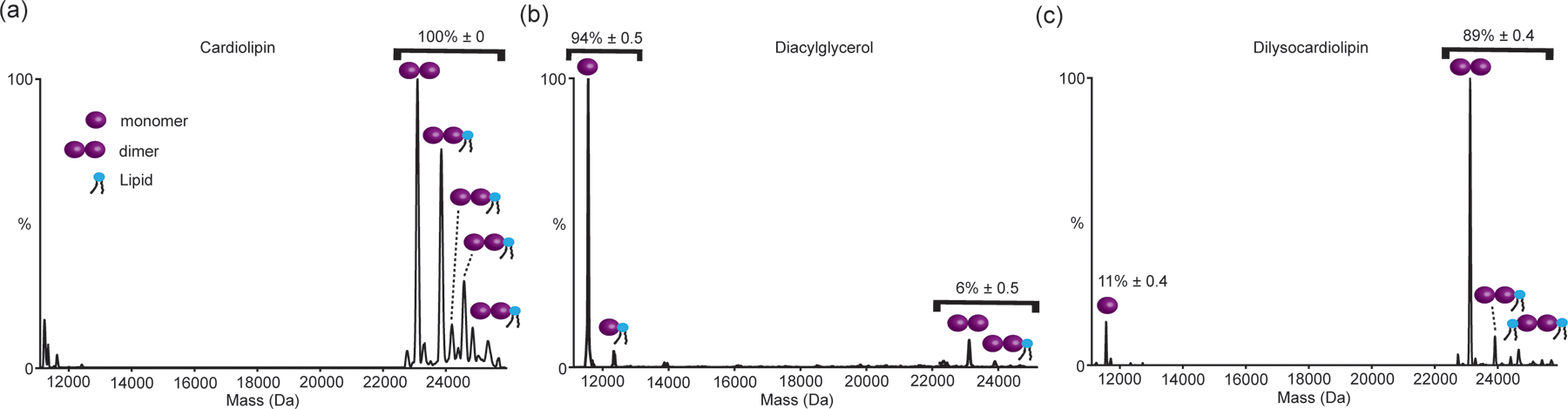

Figure 4.

UniDec derived Mass plot of semiSWEET in liposomes containing (a) 67%DOPE, 23.2%DOPG, 9.8% 18:1Cardiolipin (CL), (b) 70.9%DOPE, 27.1%DOPG, 2% 16:0–18:1DAG, and (c) 67%DOPE, 23.2%DOPG, 9.8% 18:0Dilysocardiolipin (dilyso-CL). As shown while the semiSWEET is present almost exclusively as a dimer in CL containing liposomes mimicking the gram-negative inner membrane composition, replacing CL with DAG and increasing the curvature leads to almost complete loss of the dimer. In contrast in dilyso-CL containing liposomes semiSWEET is mostly present as a dimer, highlighting the role of CL headgroup chemistry in regulating the dimeric state. The relative percentage of monomer and dimer was obtained from three independent experiment and the number on top of the peaks is mean±s.e. (n=3)

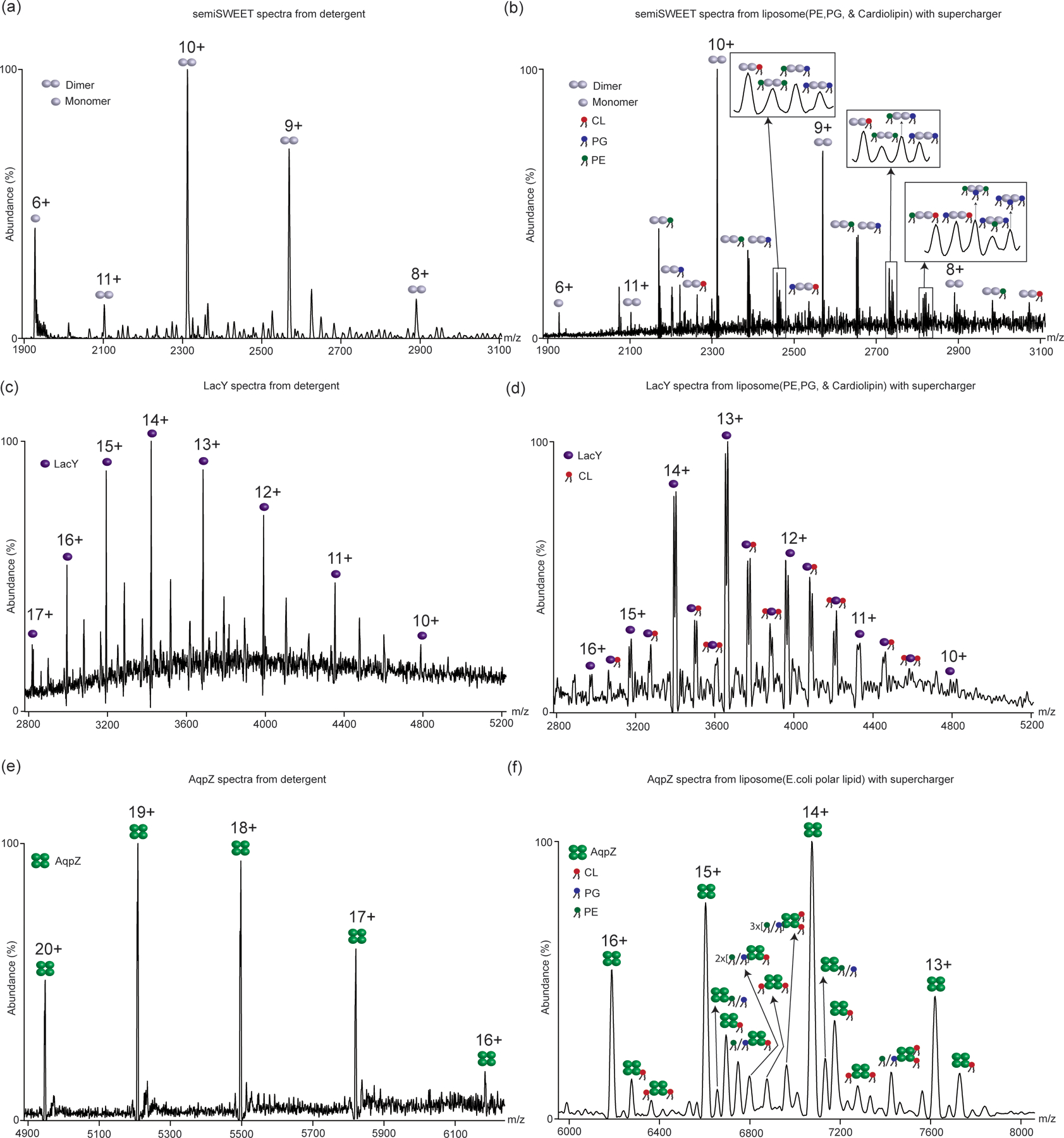

Figure 5:

nMS of different membrane proteins from detergent and proteoliposomes. (a) nMS of semiSWEET from detergent and (b) from 67%DOPE, 23.2%DOPG, 9.8% 18:1Cardiolipin proteoliposomes. (c) nMS of LacY from detergent and (d) from 67%DOPE, 23.2%DOPG, 9.8% 18:1 cardiolipin proteoliposomes. (e) nMS of AqpZ from detergent and (f) from E. coli polar lipid extract proteoliposomes. Different lipid-bound states are marked with the respective lipids. All proteoliposome samples were electrosprayed with supercharger.

Modulating size and hence curvature of nMS-ready liposomes

The curvature of a curved surface is related to the radius of curvature of that point by the formula : k = 2/(R); where k is the mean curvature and R is the radius of curvature.

For a spherical liposome, this R translates to the radius of the liposome. Hence, by precisely varying the radius of liposomes the curvature of the membrane can be modulated. To create liposomes of a specific radius, we extruded the liposomes through specific-size membrane filters 21 times. The size of the filter defines the diameter of the liposomes. The size of the extruded liposomes was further confirmed through negative stain imaging.

Native MS analysis from intact liposomes

All nMS of liposome samples were performed in 200 mM ammonium acetate and 2 mM DTT, and the protein concentration was maintained between 2uM and 5uM. To achieve stable electrospray ionization, in-house nano-emitter capillaries were used with the Q Exactive UHMR (Thermo Fisher Scientific). These nano-emitter capillaries were created by pulling borosilicate glass capillaries (O.D – 1.2mm, I.D – 0.69mm, length – 10cm, Sutter Instruments) using a Flaming/Brown micropipette puller (Model P-1000, Sutter Instruments). The nano-emitters were coated with gold using rotary pumped coater Q150R Plus (Quorum Technologies) and were used for all nMS analyses. For the nMS of proteins from lipid vesicles, the prepared proteo-lipid vesicles were used to fill the nano-emitter capillary, which was installed into the Nanospray FelxTM ion source (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The MS parameters were optimized for each sample. The spray voltage ranged between 1.2 – 1.5 kV, the capillary temperature was 275°C, and the resolving power of the MS was in the range between 3,125 – 50,000 (for MS analysis), the ultrahigh vacuum pressure was in the range of 5.51e-10 to 6.68e-10 mbar, and the in-source trapping range was between −50V and −300V. The HCD voltage was optimized for each sample ranging between 0 to 200V. In some cases, the use of 5–10% Glycerol-1,2-carbonate was observed to enhance the detection of membrane proteins out of lipid bilayer with small desolvation energy. Glycerol 1,2-Carbonate (GC) was used for SemiSWEET and AqpZ samples. All the mass spectra were visualized and analyzed with the Xcalibur software and assembled into figures using Adobe Illustrator.

For the VAMP2 lipid-bound percentage calculation in Figure 3, individual peaks were plotted in the Origin software and then the area under the curve was obtained by fitting the peak with constant baseline mode. The peak areas of protein and lipid-bound protein from Origin software were then taken for percentage calculations and the final pi-chart of this calculation is shown in Figure 3. UniDec48 was used for the calculation of the oligomer percentage of SemiSWEET (Figure 4). The outcome of spectra deconvolution in UniDec is shown in Figure 4. After spectral deconvolution, the intensity of monomer mass, dimer mass, lipid-bound monomer, and lipid-bound dimer mass were taken and the percentage of monomer (Apo+lipid bound) and dimer (Apo+lipid bound) were calculated. The relative percentage of monomer and dimer was obtained from three independent experiment and the number on top of the peaks in Figure 4 is mean±s.e. (n=3).

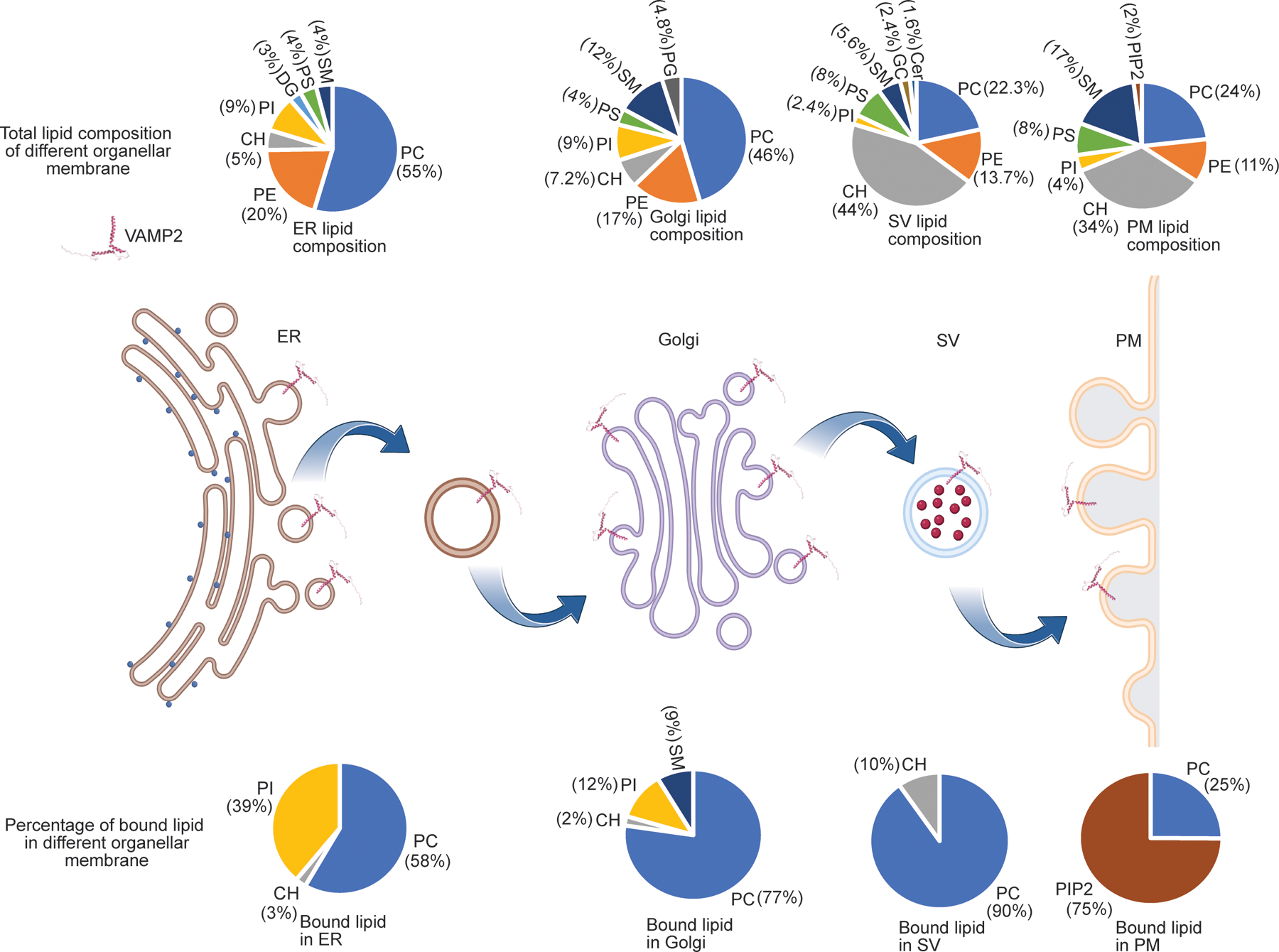

Figure 3.

Summary of lipid binding to VAMP2 in different organellar mimic liposomes. For each organelle, the pie chart above shows the lipid composition of the liposomes in mole%, whereas the pie chart below shows lipids that bind to VAMP2 in that organelle and their relative binding percentage. The total lipid bound VAMP2 is normalized to 100% for each organelle. The data highlights how the same membrane protein can bind to a different set of lipids, with different specificity, in different organellar membranes.

Negative Stain EM Protocol

The lipid vesicles were diluted 1:150 in 50 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.4. A carbon, Type-B 400 mesh, Cu grid was glow discharged for 30 seconds and 5 microliters of the sample were applied to the grid. After keeping the sample on the grid for 1 minute, it was removed with blotting paper. Next, 5 microliters of 2% uranyl formate (UFo) were applied to the grid for 5 seconds and then removed with blotting paper. Immediately after, 5 microliters of UFo were applied to the grid and kept for 1 minute. The stain was then removed with blotting paper and the grid was left to dry for 30 minutes. Finally, all images were acquired using a JEOL JEM 1400-plus at 120 kV.

RESULTS and DISCUSSION

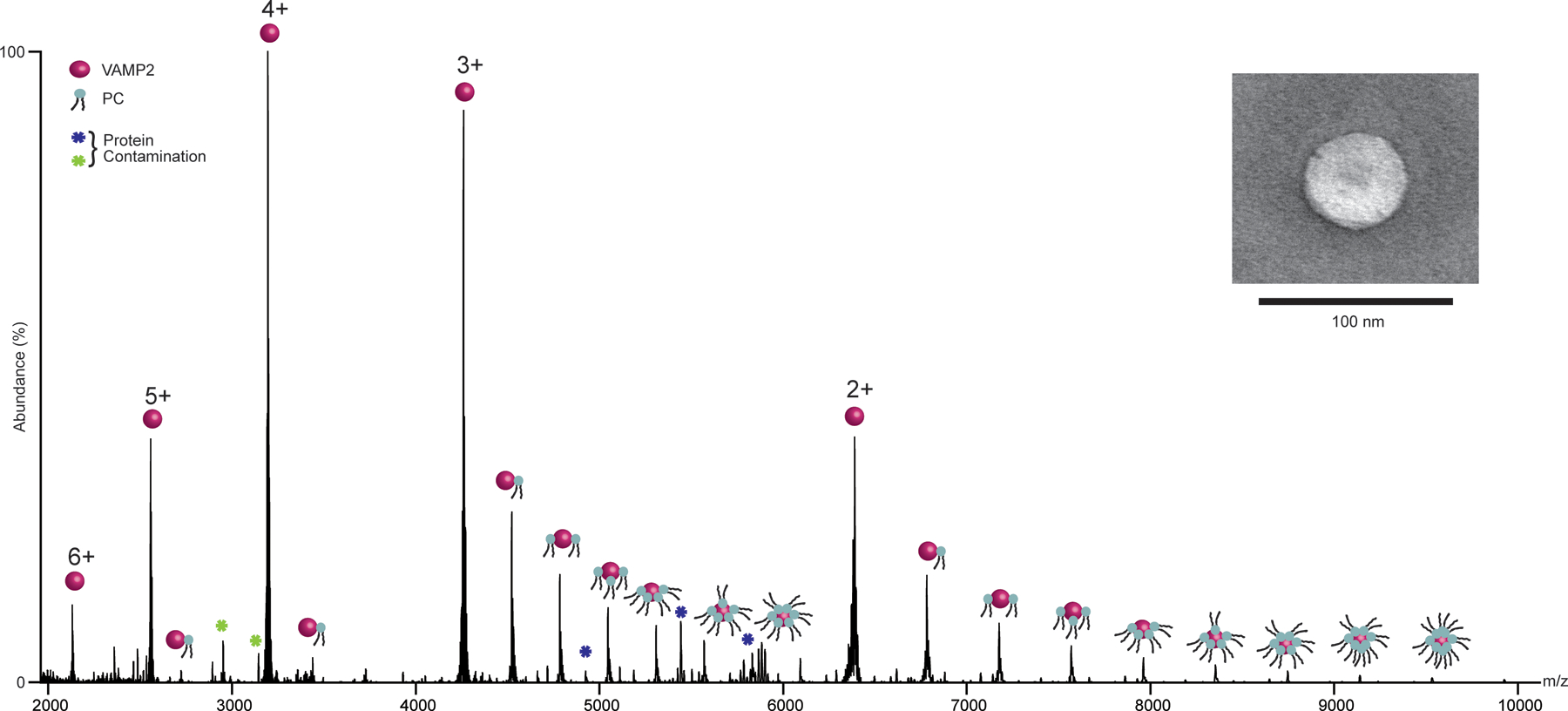

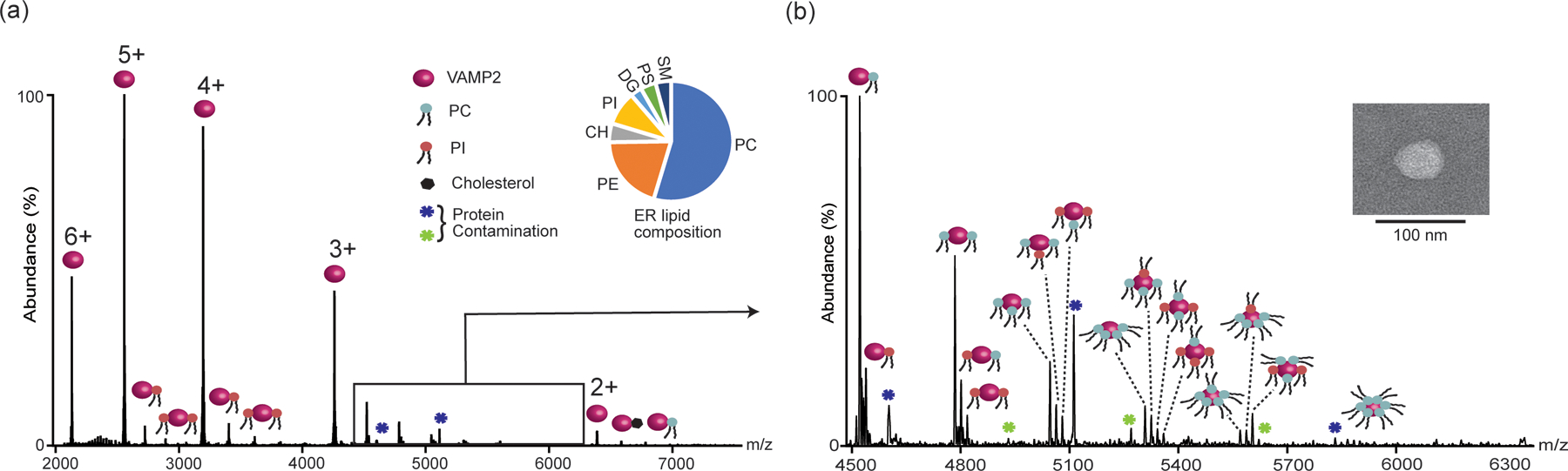

The trafficking pathway of most integral membrane proteins in eukaryotic cells involves residence in different organellar membranes49. These intracellular organelles, namely endoplasmic reticulum (ER), Golgi, mitochondria, lysosome, etc, all have lipid bilayer membranes with bespoke lipid compositions and biophysical characteristics. This means that during its trafficking pathway, the same transmembrane domain (TMD) of an integral membrane protein encounters different membrane environment. Consequently, the same TMD may bind to different sets of lipids in different organellar membranes. Such lipid-mediated sorting is thought to play a key role in both anterograde and retrograde transport of membrane proteins along the trafficking path49–51. Taking the example of VAMP2, often termed synaptobrevin or V-SNARE, we show how such selectivity can be captured through nMS analysis of the protein directly from liposomes curated to mimic the broad class-specific lipid composition of different eukaryotic organellar membranes. To achieve this, we make use of previously described methodologies to prepare nMS-ready customizable liposomes (See Methods for more details)44. We previously found that some membrane proteins are recalcitrant to ejection from the lipid membrane through collisional activation (CID), and a small amount of supercharging agents can significantly enhance our capability to ablate them from the liposome in the gas phase44. Superchargers are known to induce protonation of analytes in the gas phase52,53. We believe for proteoliposomes, this leads to protonation induced destabilization of the bilayer. Such chemical properties of the bilayer are also exploited to attain the specificity with which many mRNA vaccines release their cargo in the acidic endolysosomal systems in cells54. We believe the supercharges emulate the same chemistry in the gas phase. We expect to shed more mechanistic insight into this in the future through work that is currently ongoing in our lab. Nevertheless, a point to note here is for VAMP2 we do not require any supercharger to ablate it from the bilayer. Figure 1 shows the nMS spectra of VAMP2 directly from the 100% PC bilayer, without using any supercharger. The spectra were acquired using a front-end-trapping and desolvation voltage of 150V55. It is important to note that VAMP2 is a single-pass transmembrane protein. Considering the first annular shell of lipids, a single TM helix may consist of 10–12 lipids around it. Here, we observe up to 8 PC binding to VAMP2 in single charge states (Figure 1 charge state 2+). This is close to a full first annular shell of lipids. This indicates that we can capture almost the entire first-annular shell of the lipidome. This allowed us to subsequently study VAMP2 in different liposomes that mimic different organellar membranes without the use of a supercharger.

Figure 1.

(a) nMS spectra of VAMP2 in 100%DOPC liposomes. The spectra show distinct charge state distribution from 6+ to 2+, with bound DOPC. Inset shows the negative stain EM image of the liposome.

During its biogenesis, nascent VAMP2, a C-terminal tail-anchored membrane protein, gets first incorporated into the ER bilayer via the GET pathway chaperones. Figure 2 shows the nMS of VAMP2 in liposomes containing seven different classes of lipids, with their composition broadly mimicking that of ER membrane56,57. All apo-protein charge states, along with their lipid-bound peaks are highlighted. Specifically, the 3+ charge state is expanded due to the complexity of the lipid-bound peaks and their heterogeneity. Identities of the bound lipids could be directly determined by comparing the mass of the adduct with that of the theoretical masses of the lipids used (Table 1).

Figure 2.

(a) nMS of VAMP2 directly from liposomes containing seven different classes of lipids at a molar ratio that mimics the class-specific composition of ER. Different lipid-bound states are marked with the respective lipids. (b) Expanded view of the 3+ charge states showing up to six lipids (PC/PI) binding. Inset shows the negative stain image of the corresponding liposome.

TABLE 1:

Molar percentage of different lipids in different organellar membranes mimicking vesicles

| Lipid | Exact mass (Da) | ER | Golgi | Synaptic Vesicle | PM |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PC(18:1(9Z)/18:1(9Z)) | 785.60 | 54 | 45 | 21.3 | 23 |

| PE(18:1(9Z)/18:1(9Z)) | 743.54 | 21 | 17 | 13.7 | 11 |

| Cholesterol | 386.35 | 5 | 7.2 | 44.0 | 34 |

| PI(16:0/18:1(9Z)) | 836.52 | 9 | 9 | 2.4 | 4 |

| DAG(16:0/18:1(9Z)) | 594.52 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| PS(16:0/18:1(9Z)) | 761.52 | 4 | 4 | 8.0 | 8 |

| SM(d18:1/18:0) | 730.59 | 4 | 12 | 5.6 | 17 |

| Brain PIP2 | 1096.38(Formula Weight) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| CL(1’-[18:1(9Z)/18:1(9Z)],3’-[18:1(9Z)/18:1(9Z)]) | 1457.04 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| PG(18:1(9Z)/18:1(9Z)) | 748.50 | 0 | 4.8 | 0 | 0 |

| C16 Galactosyl(α) Ceramide | 699.56 | 0 | 0 | 2.4 | 0 |

| C16 Ceramide | 537.95 | 0 | 0 | 1.6 | 0 |

We have previously shown that in cases where the masses are closely spaced, high-resolution MS/MS analysis of the protein-lipid complex can be performed to unambiguously determine the bound lipid IDs44. But in this current work, the class-specific representative lipids are chosen in a manner that they can be distinguished at the MS1 level.

As shown in Figure 2, among the 7 different classes of lipids only phosphatidylcholine (PC) (Mass addition = 786 Da), phosphatidylinositol (PI) (Mass addition = 836 Da), and a small amount of Cholesterol (CHL) (Mass addition = 386 Da) binding was observed. Interestingly, different charge states were found to contain different extents of different lipid-bound species. This is not entirely surprising, as different charge states experience different degrees of activation under the same MS conditions. Consequently, they may retain bound lipids to a different degree. Hence, while making an overall conclusion about the ID of the bound lipids, all charge states need to be accounted for. The most complex lipid binding was observed for 3+ charge states, showing multiple successive bindings of both PC and PI. For charge state 2+, a small amount of CHL binding was observed.

Following the trafficking pathway from ER to Golgi, we next reconstituted VAMP2 in liposomes containing the broadly class-specific lipid composition of Golgi56,57. The nMS of VAMP2 from Golgi mimicking liposomes is shown in Supplementary Figure 1. Here, in addition to PC, PI, and CHL, a significant amount of SM binding was also observed. Like before, here also 3+ charge state shows the most complex lipid binding pattern. We believe this is because it provides the right balance between abundance and activation. Under the same MS CID activation conditions, higher charge states would experience higher degrees of unfolding58,59. Consequently, they show a lower amount of bound ligands. The observation of a higher percentage of lipid binding to a 3+ charge state, over +4, is a direct consequence of this. The same can be stated while comparing 3+ and 2+. But the overall low abundance of 2+ yields a lower overall abundance of the lipid-bound peaks.

In neurons, from the Golgi, VAMP2 gets packaged into synaptic vesicles (SV) and directed toward the plasma membrane (PM) of the nerve terminal. Following this, we reconstituted VAMP2 in liposomes containing class-specific lipid composition mimicking that of SV60. The nMS of VAMP2 from SV mimicking liposomes is shown in Supplementary Figure 2. Besides maintaining the lipid composition, we also controlled the size of the liposomes closer to that of SV (~30nm diameter). Additionally, we also controlled the copy number of VAMP2 to its physiologically relevant density (roughly 60 protein/vesicles)60. nMS of VAMP2 from these vesicles (Supplementary Figure 2) echoed our previously established observation that in SV-like membranes, PC and CHL binding to VAMP2 is observed44. A point to highlight here is, among the eight different lipid classes present in the SV, both PI and SM are present. VAMP2 is found to bind to both these sets of lipids in membranes of other organellar mimics but not in the SV. We have previously shown how this specificity of PC and CHL binding may arise from the partitioning of VAMP2 in lipid domains that are enriched in these two lipids, and how that, in turn, regulates the speed of neurotransmitter release44. This further highlights the importance of capturing lipid binding to membrane proteins directly from the collective milieu of the bilayer lipid mixture. Directly studying membrane proteins from liposomes that allow such lateral diffusion and subsequent diffusion-controlled binding enables us to capture these binding specificities.

Finally, post-fusion and before endocytosis, VAMP2 resides on the PM of the axon. Supplementary Figure 3 shows the nMS of VAMP2 in liposomes mimicking the broad, class-specific composition of the PM56,57. Surprisingly, the most abundant bound lipid was found to be PIP2. Again, both PC and SM are present in this bilayer with mol%> 20%. Interestingly, it has been shown that PIP2 plays a central role in regulating the exo- and endocytosis cycle at the nerve terminal61. While current work in the lab is ongoing to delineate the functional role of this PIP2 binding, it highlights how small changes in the membrane composition can significantly alter the lipid binding specificity of a membrane protein.

Figure 3 summarizes the lipid binding specificity of the same transmembrane domain across its organellar trafficking. This data further highlights how we can leverage the customizability of the liposome platform to curate the bilayer environment to meet the needs of required lipid composition and detect membrane protein-lipid binding specificity.

Looking beyond the tunability of lipid composition, liposomes also provide a unique platform to modulate bulk bilayer properties, allowing us to tightly control both biophysical and chemical bilayer properties. This enables us to tease apart the chemical vs biophysical properties of specific lipids in regulating the formation of higher-order membrane assemblies. To demonstrate this, we take SemiSWEET as a model system where we disentangle the role of bulk bilayer properties versus specific lipid interactions on oligomerization. As shown before, SemiSWEET exists almost exclusively as a dimer in liposomes mimicking the inner membrane lipidome of gram-negative bacteria44. We have observed similar observation in this study as well which is shown in Figure 4(a). We have previously demonstrated that the presence of Cardiolipin (CL) can regulate the functional dimeric state of this bacterial sugar transporter44. CL, among all bacterial inner membrane lipids, has the highest negative charge with its diphosphate moiety. Apart from this high negative charge density, it is also known to induce curvature in biological membranes. Using the tunability of liposomes, we aimed to understand whether the negatively charged headgroup or the high-curvature-inducing property that stabilizes the dimeric state of SemiSWEET. To independently dissect the role of these two properties, we next reconstituted SemiSWEET in high curvature liposomes that are devoid of any CL (See Methods). Here, we replace CL with diacylglycerol (DAG), another curvature-inducing lipid without the same headgroup chemistry as CL (Figure 4(b)). nMS analysis of SemiSWEET from these liposomes showed near-complete abrogation of the dimeric species, with almost exclusive presence of monomer (Figure 4(b)). We then probed the effect of the diphosphate headgroup of CL by reconstituting SemiSWEET in liposomes containing dilyso-CL, which lacks two alkyl chains but has the same diphosphate headgroup as CL. Reversing the trend observed for DAG-containing liposomes, the introduction of dilyso-CL almost completely rescued the dimeric state back to the level of CL-containing liposomes (Figure 4(c)). This confirms that the di-phosphate headgroup chemistry of CL leads to the stabilization of the dimeric state of SemiSWEET, but not its curvature-inducing properties. The small amount of decrease in the dimer population observed for the dilyso-CL liposomes, compared to the CL-liposomes, could be attributed to the additional dimer stability imparted by two-alkyl chains/CL that is missing in the dilyso-CL.

The experiments described above demonstrate how combining liposomes with nMS enable us to not just determine membrane-bound organization states of proteins and the identity of the bound lipids, but also gain quantitative insight into how specific membrane properties and constituents regulate these observed oligomeric organizations. Taking the example of VAMP2, we show how lipid specificity of the same transmembrane domain changes across the different organellar membranes that VAMP2 encounters in its trafficking cycle. The case study of SemiSWEET shows how the tunability of the liposomes enables quantitative determination of the role of lipids in regulating membrane protein oligomerization.

A critical point to note here is that none of the vesicles required the use of a supercharger to liberate VAMP2, which contrasts with the SemiSWEET that required the use of a supercharger (Figure 4). A tempting speculation is that the larger numbers of TMDs in proteins require greater energy for ejection from the bilayer (SemiSWEET dimer has 6 TMD whereas VAMP2 has just one). However, we have previously shown MscL, another oligomeric, multi-TMD protein does not require the use of a supercharger44. Explaining this may demand more nuanced reasoning involving the thermodynamics of TMD-bilayer interactions. Indeed, ejecting a TMD from the bilayer involves overcoming the solvation energy of that TMD in the given lipid environment through ergodic collisional activation. Hence, the energy required for the detection of TMD from a given membrane is expected to be a function of the TMD-bilayer solvation energy. Although the precise mechanism by which superchargers destabilize liposomes in the gas phase is not fully understood, the general physicochemical rationale involves protonation-induced destabilization of the bilayer by the superchargers44. In future studies, by systematically incorporating model TMDs in liposomes of specific compositions, we aim to gain a more comprehensive understanding of the mechanism.

Another critical point here is the use of superchargers has been previously found to increase the charge states of proteins in the gas phase52,53. This increase in charge state often results in the loss of ligand binding and de-oligomerization. It is believed that the increased charge states cause the unfolding of protein structures, leading to the loss of non-covalent interactions between proteins and ligands. This phenomenon has been previously demonstrated in soluble proteins through various observations62,63. Consequently, we were cautious about any potential impact of superchargers on detecting protein-protein/protein-lipid complexes from proteo-liposomes. However, intriguingly, no appreciable increase in average charge states was observed when membrane proteins were directly studied from liposomes in the presence of superchargers. Figure 5 illustrates the comparison of nMS results for several membrane proteins in detergent before their incorporation into liposomes, and the respective nMS results obtained from proteoliposomes in the presence of a supercharger. As shown, no increase in charge state was observed when superchargers were added to the proteoliposomes. We believe that the reason behind this intriguing observation is related to why superchargers facilitate the removal of membrane proteins from the lipid bilayer. We posit this is because in the gas phase, while studying proteoliposomes, superchargers preferentially protonate lipid headgroups over the embedded membrane proteins. This is supported by previous work conducted by Prell and colleagues64, which demonstrated that in the gas phase, protonation of choline headgroups in lipids is more favorable than that of basic amino acids like arginine. Choline headgroups are the predominant headgroup in the eukaryotic lipidome, found in both phosphatidylcholine (PC) and sphingomyelin (SM) lipid classes, constituting over one-third of the human lipidome. Additionally, the protein-to-lipid ratio in proteoliposomes is heavily skewed toward lipids, ranging from 1:100 to 1:1000. As a result, the preferential protonation of lipids upon the addition of a supercharger to proteoliposomes induces surface charge-based strains in the lipid bilayer, leading to its destabilization in the gas phase. This protonation of lipids also ensures that the charge states of proteins do not increase even after the addition of a supercharger. Consequently, the typical unfolding of proteins induced by superchargers and the subsequent loss of non-covalent interactions are minimized in this case. This can be observed in Figure 5 comparing the nMS of different membrane proteins before reconstructions in detergents (no supercharger) and post-reconstitution from liposomes (with supercharger). No observable increase in average charge state distribution was observed. Further, in each of these cases, we could detect specific binding of lipids. For AqpZ in E. coli polar lipid liposomes in Figure 5(f), we could detect the binding of cardiolipin (CL), which has been previously demonstrated in detergent-based studies and shown to regulate AqpZ functions36. Complex lipid binding to other membrane proteins can also be observed, e.g. PE, PG, and CL binding to SemiSWEET (Figure 5(b)) and CL binding to LacY in Figure 5(d). All these examples illustrate the retention of bound lipids to membrane proteins in the presence of superchargers.

Together, the current platform enables us to directly put a target membrane protein in bilayers of defined composition and biophysical properties. This allows us to study protein organization state, lipid-protein interaction, and how specific membrane properties and constituents regulate these protein organizations. Using this platform, we show VAMP2 binds to different sets of lipids in different biological membranes. By using curated bilayers, we capture the competitive binding of different sets of lipids directly from the complex milieu of native-like composition. This underscores the critical point that even if a lipid can bind directly to a target TMD in isolation, binding of that lipid would bind to the same TMD in the native membrane milieu would depend on both the affinity of other lipids present and their mole %. Further, in the two-dimensional membrane, it would also depend on whether the target TMD and the lipid both partition into the same membrane domain. This is captured in the observed PC-CHL binding to VAMP2 in an SV-like membrane. Despite the SV-membrane containing lipids that VAMP2 binds to in other organellar mimic liposomes (e.g. SM, PI), only PC and CHL binding is observed SV-membrane. Using coarse-grained MD simulation, we previously showed that PC and CHL form distinct domains in the SV-like membrane where VAMP2 partitions into44. This effectively excludes other lipids from encountering VAMP2 and binding. Directly studying membrane proteins from bilayers where lateral diffusion and membrane heterogeneity can be maintained allows us to capture these diffusion-controlled binding events. The VAMP2 results showing distinctly different lipid binding patterns of the same membrane protein in different organellar membrane composition highlights this point. While in the current study, we used class-specific representatives, similar studies can highlight chain-length and unsaturation-based preferences and partitioning in membrane protein-lipid selectivity in the membrane.

Beyond determining protein-lipid interactions, the tunability of the platform enables us to further evaluate the effects of specific membrane properties. We highlight this using SemiSWEET. nMS of SemiSWEET in the native lipidome of the gram-negative bacteria yields a dimeric state of the protein. We showed that the presence of CL in the membrane can directly influence the stability of this dimeric state. Here we further expanded on this observation to tease apart whether such stability is imparted by the high curvature-inducing properties of CL or because of its negative charge. By studying SemiSWEET from liposomes of high curvature, we conclude that the effect of CL is directly owing to its negative charge and not its curvature-inducing properties.

CONCLUSION

Our work highlights the ability of nMS to study target membrane protein complexes directly from customizable liposomes where both composition and membrane properties can be modulated to mimic a target physiological membrane. This enables not just the detection of the membrane-embedded organization state but also enables us to titrate in/out specific membrane constituents/properties to tease apart their role in regulating the observed oligomeric organization states. Such customizability of liposomes to mimic and modulate properties of the native membrane has already made it the vehicle of choice to study a range of functions of membrane proteins, including ion transport2,9, G-protein driven signaling65,66, and protein trafficking67,68, to name a few. Very recently, there has also been a steady increase in the number of CryoEM structures of membrane proteins directly from liposomes69–71. Coupling these techniques with our liposome-nMS protocol will allow direct structural, functional, and mass spectral analysis of target membrane proteins directly from the same liposome samples. Our work establishes that nMS can provide molecular resolution to determine molecular organization states, the identity of the bound lipids, and their effects in regulating those organizations, while CryoEM can provide atomistic resolution to visualize these assemblies, and functional analysis can tease apart how these complexes eventually regulate the desired cellular function; all directly from customizable lipid membranes.

Supplementary Material

(a) nMS of VAMP2 directly from liposomes containing seven different classes of lipids at a molar ratio that mimics the class-specific composition of Golgi. Different lipid-bound states are marked with the respective lipids. (b) The 3+ charge state is expanded to show lipid binding of PC, PI, and SM. Inset shows the negative stain image of the corresponding liposome.

(a) nMS of VAMP2 directly from liposomes containing eight different classes of lipids at a molar ratio that mimics the class-specific composition of the synaptic vesicle (SV). The size of the vesicles was also tuned to match the diameter and curvature of SV. Different lipid-bound states are marked with the respective lipids. Only PC and CHL binding was observed. (b) The 3+ charge state is expanded to show up to six binding of PC. Inset shows the negative stain image of the corresponding liposome.

(a) nMS of VAMP2 directly from liposomes containing seven different classes of lipids at a molar ratio that mimics the class-specific composition of PM. Different lipid-bound states are marked with the respective lipids. PIP2 and PC were the only two lipids observed to be bound. (b) The 3+ charge state is expanded to show multiple binding of PIP2 and PC. Inset shows the negative stain image of the corresponding liposome.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health grants R01GM141192 to KG.

Footnotes

COMPETING INTERESTS STATEMENT

The authors declare no competing interests.

REFERENCES

- (1).Sezgin E; Levental I; Mayor S; Eggeling C The Mystery of Membrane Organization: Composition, Regulation and Roles of Lipid Rafts. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol 2017, 18 (6), 361–374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Schmidpeter PAM; Wu D; Rheinberger J; Riegelhaupt PM; Tang H; Robinson CV; Nimigean CM Anionic Lipids Unlock the Gates of Select Ion Channels in the Pacemaker Family. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol 2022, 29 (11), 1092–1100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Chadda R; Krishnamani V; Mersch K; Wong J; Brimberry M; Chadda A; Kolmakova-Partensky L; Friedman LJ; Gelles J; Robertson JL The Dimerization Equilibrium of a ClC Cl(−)/H(+) Antiporter in Lipid Bilayers. eLife 2016, 5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Gupta K; Donlan JAC; Hopper JTS; Uzdavinys P; Landreh M; Struwe WB; Drew D; Baldwin AJ; Stansfeld PJ; Robinson CV The Role of Interfacial Lipids in Stabilizing Membrane Protein Oligomers. Nature 2017, 541 (7637), 421–424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Danoff EJ; Fleming KG Novel Kinetic Intermediates Populated along the Folding Pathway of the Transmembrane β-Barrel OmpA. Biochemistry 2017, 56 (1), 47–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Whorton MR; MacKinnon R Crystal Structure of the Mammalian GIRK2 K+ Channel and Gating Regulation by G Proteins, PIP2, and Sodium. Cell 2011, 147 (1), 199–208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Polley A; Orłowski A; Danne R; Gurtovenko AA; Bernardino de la Serna J; Eggeling C; Davis SJ; Róg T; Vattulainen I Glycosylation and Lipids Working in Concert Direct CD2 Ectodomain Orientation and Presentation. J. Phys. Chem. Lett 2017, 8 (5), 1060–1066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Yen H-Y; Hoi KK; Liko I; Hedger G; Horrell MR; Song W; Wu D; Heine P; Warne T; Lee Y; et al. PtdIns(4,5)P2 Stabilizes Active States of GPCRs and Enhances Selectivity of G-Protein Coupling. Nature 2018, 559 (7714), 423–427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Ananchenko A; Hussein TOK; Mody D; Thompson MJ; Baenziger JE Recent Insight into Lipid Binding and Lipid Modulation of Pentameric Ligand-Gated Ion Channels. Biomolecules 2022, 12 (6). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Engelman DM Membranes Are More Mosaic than Fluid. Nature 2005, 438 (7068), 578–580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Andersen OS; Koeppe RE Bilayer Thickness and Membrane Protein Function: An Energetic Perspective. Annu. Rev. Biophys. Biomol. Struct 2007, 36, 107–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Levental KR; Malmberg E; Symons JL; Fan Y-Y; Chapkin RS; Ernst R; Levental I Lipidomic and Biophysical Homeostasis of Mammalian Membranes Counteracts Dietary Lipid Perturbations to Maintain Cellular Fitness. Nat. Commun 2020, 11 (1), 1339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Simunovic M; Voth GA; Callan-Jones A; Bassereau P When Physics Takes over: BAR Proteins and Membrane Curvature. Trends Cell Biol. 2015, 25 (12), 780–792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Kefauver JM; Ward AB; Patapoutian A Discoveries in Structure and Physiology of Mechanically Activated Ion Channels. Nature 2020, 587 (7835), 567–576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Katta V; Chait BT Observation of the Heme-Globin Complex in Native Myoglobin by Electrospray-Ionization Mass Spectrometry. J. Am. Chem. Soc 1991, 113 (22), 8534–8535. [Google Scholar]

- (16).Marcoux J; Robinson CV Twenty Years of Gas Phase Structural Biology. Structure 2013, 21 (9), 1541–1550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Leney AC; Heck AJR Native Mass Spectrometry: What Is in the Name? J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom 2017, 28 (1), 5–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Jooß K; McGee JP; Kelleher NL Native Mass Spectrometry at the Convergence of Structural Biology and Compositional Proteomics. Acc. Chem. Res 2022, 55 (14), 1928–1937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Elliott AG; Harper CC; Lin H-W; Williams ER Mass, Mobility and MSn Measurements of Single Ions Using Charge Detection Mass Spectrometry. Analyst 2017, 142 (15), 2760–2769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Keifer DZ; Pierson EE; Jarrold MF Charge Detection Mass Spectrometry: Weighing Heavier Things. Analyst 2017, 142 (10), 1654–1671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Kafader JO; Melani RD; Durbin KR; Ikwuagwu B; Early BP; Fellers RT; Beu SC; Zabrouskov V; Makarov AA; Maze JT; et al. Multiplexed Mass Spectrometry of Individual Ions Improves Measurement of Proteoforms and Their Complexes. Nat. Methods 2020, 17 (4), 391–394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Wörner TP; Snijder J; Bennett A; Agbandje-McKenna M; Makarov AA; Heck AJR Resolving Heterogeneous Macromolecular Assemblies by Orbitrap-Based Single-Particle Charge Detection Mass Spectrometry. Nat. Methods 2020, 17 (4), 395–398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Clemmer DE; Hudgins RR; Jarrold MF Naked Protein Conformations: Cytochrome c in the Gas Phase. J. Am. Chem. Soc 1995, 117 (40), 10141–10142. [Google Scholar]

- (24).Wyttenbach T; Bowers MT Structural Stability from Solution to the Gas Phase: Native Solution Structure of Ubiquitin Survives Analysis in a Solvent-Free Ion Mobility-Mass Spectrometry Environment. J. Phys. Chem. B 2011, 115 (42), 12266–12275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Marklund EG; Degiacomi MT; Robinson CV; Baldwin AJ; Benesch JLP Collision Cross Sections for Structural Proteomics. Structure 2015, 23 (4), 791–799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Eschweiler JD; Farrugia MA; Dixit SM; Hausinger RP; Ruotolo BT A Structural Model of the Urease Activation Complex Derived from Ion Mobility-Mass Spectrometry and Integrative Modeling. Structure 2018, 26 (4), 599–606.e3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Shaw JB; Li W; Holden DD; Zhang Y; Griep-Raming J; Fellers RT; Early BP; Thomas PM; Kelleher NL; Brodbelt JS Complete Protein Characterization Using Top-down Mass Spectrometry and Ultraviolet Photodissociation. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2013, 135 (34), 12646–12651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Sahasrabuddhe A; Hsia Y; Busch F; Sheffler W; King NP; Baker D; Wysocki VH Confirmation of Intersubunit Connectivity and Topology of Designed Protein Complexes by Native MS. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2018, 115 (6), 1268–1273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Li H; Nguyen HH; Ogorzalek Loo RR; Campuzano IDG; Loo JA An Integrated Native Mass Spectrometry and Top-down Proteomics Method That Connects Sequence to Structure and Function of Macromolecular Complexes. Nat. Chem 2018, 10 (2), 139–148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Harvey SR; Seffernick JT; Quintyn RS; Song Y; Ju Y; Yan J; Sahasrabuddhe AN; Norris A; Zhou M; Behrman EJ; et al. Relative Interfacial Cleavage Energetics of Protein Complexes Revealed by Surface Collisions. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2019, 116 (17), 8143–8148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Crittenden CM; Novelli ET; Mehaffey MR; Xu GN; Giles DH; Fies WA; Dalby KN; Webb LJ; Brodbelt JS Structural Evaluation of Protein/Metal Complexes via Native Electrospray Ultraviolet Photodissociation Mass Spectrometry. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom 2020, 31 (5), 1140–1150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Schachner LF; Jooß K; Morgan MA; Piunti A; Meiners MJ; Kafader JO; Lee AS; Iwanaszko M; Cheek MA; Burg JM; et al. Decoding the Protein Composition of Whole Nucleosomes with Nuc-MS. Nat. Methods 2021, 18 (3), 303–308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Wörner TP; Aizikov K; Snijder J; Fort KL; Makarov AA; Heck AJR Frequency Chasing of Individual Megadalton Ions in an Orbitrap Analyser Improves Precision of Analysis in Single-Molecule Mass Spectrometry. Nat. Chem 2022, 14 (5), 515–522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).Whitelegge JP; Gundersen CB; Faull KF Electrospray-Ionization Mass Spectrometry of Intact Intrinsic Membrane Proteins. Protein Sci. 1998, 7 (6), 1423–1430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35).Barrera NP; Di Bartolo N; Booth PJ; Robinson CV Micelles Protect Membrane Complexes from Solution to Vacuum. Science 2008, 321 (5886), 243–246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (36).Laganowsky A; Reading E; Allison TM; Ulmschneider MB; Degiacomi MT; Baldwin AJ; Robinson CV Membrane Proteins Bind Lipids Selectively to Modulate Their Structure and Function. Nature 2014, 510 (7503), 172–175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (37).Konijnenberg A; Bannwarth L; Yilmaz D; Koçer A; Venien-Bryan C; Sobott F Top-down Mass Spectrometry of Intact Membrane Protein Complexes Reveals Oligomeric State and Sequence Information in a Single Experiment. Protein Sci. 2015, 24 (8), 1292–1300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (38).Cong X; Liu Y; Liu W; Liang X; Laganowsky A Allosteric Modulation of Protein-Protein Interactions by Individual Lipid Binding Events. Nat. Commun 2017, 8 (1), 2203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (39).Zhang G; Keener JE; Marty MT Measuring Remodeling of the Lipid Environment Surrounding Membrane Proteins with Lipid Exchange and Native Mass Spectrometry. Anal. Chem 2020, 92 (8), 5666–5669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (40).Fantin SM; Parson KF; Yadav P; Juliano B; Li GC; Sanders CR; Ohi MD; Ruotolo BT Ion Mobility-Mass Spectrometry Reveals the Role of Peripheral Myelin Protein Dimers in Peripheral Neuropathy. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2021, 118 (17). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (41).Chen S; Getter T; Salom D; Wu D; Quetschlich D; Chorev DS; Palczewski K; Robinson CV Capturing a Rhodopsin Receptor Signalling Cascade across a Native Membrane. Nature 2022, 604 (7905), 384–390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (42).Hopper JTS; Yu YT-C; Li D; Raymond A; Bostock M; Liko I; Mikhailov V; Laganowsky A; Benesch JLP; Caffrey M; et al. Detergent-Free Mass Spectrometry of Membrane Protein Complexes. Nat. Methods 2013, 10 (12), 1206–1208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (43).Chorev DS; Baker LA; Wu D; Beilsten-Edmands V; Rouse SL; Zeev-Ben-Mordehai T; Jiko C; Samsudin F; Gerle C; Khalid S; et al. Protein Assemblies Ejected Directly from Native Membranes Yield Complexes for Mass Spectrometry. Science 2018, 362 (6416), 829–834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (44).Panda A; Giska F; Duncan AL; Welch AJ; Brown C; McAllister R; Hariharan P; Goder JND; Coleman J; Ramakrishnan S; et al. Direct Determination of Oligomeric Organization of Integral Membrane Proteins and Lipids from Intact Customizable Bilayer. Nat. Methods 2023. Apr 27. doi: 10.1038/s41592-023-01864-5. Online ahead of print [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (45).Archer BT; Ozçelik T; Jahn R; Francke U; Südhof TC Structures and Chromosomal Localizations of Two Human Genes Encoding Synaptobrevins 1 and 2. J. Biol. Chem 1990, 265 (28), 17267–17273. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (46).Söllner T; Whiteheart SW; Brunner M; Erdjument-Bromage H; Geromanos S; Tempst P; Rothman JE SNAP Receptors Implicated in Vesicle Targeting and Fusion. Nature 1993, 362 (6418), 318–324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (47).Guan L; Mirza O; Verner G; Iwata S; Kaback HR Structural Determination of Wild-Type Lactose Permease. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2007, 104 (39), 15294–15298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (48).Marty MT; Baldwin AJ; Marklund EG; Hochberg GKA; Benesch JLP; Robinson CV Bayesian Deconvolution of Mass and Ion Mobility Spectra: From Binary Interactions to Polydisperse Ensembles. Anal. Chem 2015, 87 (8), 4370–4376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (49).Palade G Intracellular Aspects of the Process of Protein Synthesis. Science 1975, 189 (4200), 347–358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (50).von Blume J; Hausser A Lipid-Dependent Coupling of Secretory Cargo Sorting and Trafficking at the Trans-Golgi Network. FEBS Lett. 2019, 593 (17), 2412–2427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (51).Weigel AV; Chang C-L; Shtengel G; Xu CS; Hoffman DP; Freeman M; Iyer N; Aaron J; Khuon S; Bogovic J; et al. ER-to-Golgi Protein Delivery through an Interwoven, Tubular Network Extending from ER. Cell 2021, 184 (9), 2412–2429.e16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (52).Ogorzalek Loo RR; Lakshmanan R; Loo JA What Protein Charging (and Supercharging) Reveal about the Mechanism of Electrospray Ionization. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom 2014, 25 (10), 1675–1693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (53).Going CC; Xia Z; Williams ER New Supercharging Reagents Produce Highly Charged Protein Ions in Native Mass Spectrometry. Analyst 2015, 140 (21), 7184–7194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (54).Mitchell MJ; Billingsley MM; Haley RM; Wechsler ME; Peppas NA; Langer R Engineering Precision Nanoparticles for Drug Delivery. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov 2021, 20 (2), 101–124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (55).Fort KL; van de Waterbeemd M; Boll D; Reinhardt-Szyba M; Belov ME; Sasaki E; Zschoche R; Hilvert D; Makarov AA; Heck AJR Expanding the Structural Analysis Capabilities on an Orbitrap-Based Mass Spectrometer for Large Macromolecular Complexes. Analyst 2017, 143 (1), 100–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (56).van Meer G; Voelker DR; Feigenson GW Membrane Lipids: Where They Are and How They Behave. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol 2008, 9 (2), 112–124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (57).Casares D; Escribá PV; Rosselló CA Membrane Lipid Composition: Effect on Membrane and Organelle Structure, Function and Compartmentalization and Therapeutic Avenues. Int. J. Mol. Sci 2019, 20 (9). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (58).Kitova EN; El-Hawiet A; Schnier PD; Klassen JS Reliable Determinations of Protein-Ligand Interactions by Direct ESI-MS Measurements. Are We There Yet? J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom 2012, 23 (3), 431–441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (59).Chingin K; Barylyuk K Charge-State-Dependent Variation of Signal Intensity Ratio between Unbound Protein and Protein-Ligand Complex in Electrospray Ionization Mass Spectrometry: The Role of Solvent-Accessible Surface Area. Anal. Chem 2018, 90 (9), 5521–5528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (60).Takamori S; Holt M; Stenius K; Lemke EA; Grønborg M; Riedel D; Urlaub H; Schenck S; Brügger B; Ringler P; et al. Molecular Anatomy of a Trafficking Organelle. Cell 2006, 127 (4), 831–846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (61).Cremona O; Di Paolo G; Wenk MR; Lüthi A; Kim WT; Takei K; Daniell L; Nemoto Y; Shears SB; Flavell RA; et al. Essential Role of Phosphoinositide Metabolism in Synaptic Vesicle Recycling. Cell 1999, 99 (2), 179–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (62).Cubrilovic D; Zenobi R Influence of Dimehylsulfoxide on Protein-Ligand Binding Affinities. Anal. Chem 2013, 85 (5), 2724–2730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (63).Yao Y; Richards MR; Kitova EN; Klassen JS Influence of Sulfolane on ESI-MS Measurements of Protein-Ligand Affinities. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom 2016, 27 (3), 498–506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (64).Miller ZM; Zhang JD; Donald WA; Prell JS Gas-Phase Protonation Thermodynamics of Biological Lipids: Experiment, Theory, and Implications. Anal. Chem 2020, 92 (15), 10365–10374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (65).Berstein G; Blank JL; Smrcka AV; Higashijima T; Sternweis PC; Exton JH; Ross EM Reconstitution of Agonist-Stimulated Phosphatidylinositol 4,5-Bisphosphate Hydrolysis Using Purified M1 Muscarinic Receptor, Gq/11, and Phospholipase C-Beta 1. J. Biol. Chem 1992, 267 (12), 8081–8088. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (66).Suzuki Y; Ogasawara T; Tanaka Y; Takeda H; Sawasaki T; Mogi M; Liu S; Maeyama K Functional G-Protein-Coupled Receptor (GPCR) Synthesis: The Pharmacological Analysis of Human Histamine H1 Receptor (HRH1) Synthesized by a Wheat Germ Cell-Free Protein Synthesis System Combined with Asolectin Glycerosomes. Front. Pharmacol 2018, 9, 38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (67).Shao S; Rodrigo-Brenni MC; Kivlen MH; Hegde RS Mechanistic Basis for a Molecular Triage Reaction. Science 2017, 355 (6322), 298–302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (68).Guna A; Hegde RS Transmembrane Domain Recognition during Membrane Protein Biogenesis and Quality Control. Curr. Biol 2018, 28 (8), R498–R511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (69).Liu Y; Sigworth FJ Automatic Cryo-EM Particle Selection for Membrane Proteins in Spherical Liposomes. J. Struct. Biol 2014, 185 (3), 295–302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (70).Yao X; Fan X; Yan N Cryo-EM Analysis of a Membrane Protein Embedded in the Liposome. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2020, 117 (31), 18497–18503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (71).Sengupta N; Mondal AK; Mishra S; Chattopadhyay K; Dutta S Single-Particle Cryo-EM Reveals Conformational Variability of the Oligomeric VCC β-Barrel Pore in a Lipid Bilayer. J. Cell Biol 2021, 220 (12). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(a) nMS of VAMP2 directly from liposomes containing seven different classes of lipids at a molar ratio that mimics the class-specific composition of Golgi. Different lipid-bound states are marked with the respective lipids. (b) The 3+ charge state is expanded to show lipid binding of PC, PI, and SM. Inset shows the negative stain image of the corresponding liposome.

(a) nMS of VAMP2 directly from liposomes containing eight different classes of lipids at a molar ratio that mimics the class-specific composition of the synaptic vesicle (SV). The size of the vesicles was also tuned to match the diameter and curvature of SV. Different lipid-bound states are marked with the respective lipids. Only PC and CHL binding was observed. (b) The 3+ charge state is expanded to show up to six binding of PC. Inset shows the negative stain image of the corresponding liposome.

(a) nMS of VAMP2 directly from liposomes containing seven different classes of lipids at a molar ratio that mimics the class-specific composition of PM. Different lipid-bound states are marked with the respective lipids. PIP2 and PC were the only two lipids observed to be bound. (b) The 3+ charge state is expanded to show multiple binding of PIP2 and PC. Inset shows the negative stain image of the corresponding liposome.