Abstract

Introduction

Psychedelics have garnered increased attention as potential therapeutic options for various mental illnesses. Previous studies reported that psychedelics cause psychoactive effects through mystical experiences induced by these substances, including an altered state of consciousness. While this phenomenon is commonly assessed by the Mystical Experiences Questionnaire (MEQ30), a Japanese version of the MEQ30 has not been available. The aim of this study was to develop the Japanese version of the MEQ30.

Methods

We adhered to the “Principles of Good Practice for the Translation and Cultural Adaptation Process for Patient‐Reported Outcomes (PRO) Measures: Report of the ISPOR Task Force for Translation and Cultural Adaptation” in our translation process. Two Japanese psychiatrists independently performed forward translations, from which a unified version was derived through reconciliation. This version was subsequently back‐translated into English and reviewed by the original authors for equivalency. The iterative revision process was carried out through ongoing discussions with the original authors until they approved the final back‐translated version.

Results

The final, approved back‐translated version of the MEQ30 is presented in the accompanying figure. Additionally, the authorized Japanese version of the MEQ30 is included in the Appendix A.

Conclusions

In this study, we successfully developed a Japanese version of the MEQ30. This scale will facilitate the assessment of mystical experiences associated with psychedelic‐assisted therapy among Japanese speakers. Further research is warranted to evaluate the reliability and validity of this newly translated scale.

Keywords: human, Mystical Experiences Questionnaire, psychedelics

Psychedelics may aid mental illness treatment via mystical experiences. Although they are frequently assessed by the Mystical Experiences Questionnaire (MEQ30), no Japanese version existed. The approved MEQ30 Japanese version is now available.

1. INTRODUCTION

Recently, there has been mounting global interest in psychedelics as potential treatments for various mental illnesses, including treatment‐resistant depression, addictive disorders, post‐traumatic stress disorder, and terminal mental distress. 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 Psychedelics elicit altered states of consciousness, encompassing altered visual perception, a sense of unity with the universe, transcendence of time and space, and ego dissolution. 9 , 10 Previous studies have created several scales, such as the Psychological Insight Scale and Psychological Insight Questionnaire, to gauge these altered states induced by psychedelics. 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 Several studies indicate that the intensity of altered consciousness, as measured by these scales, correlates with the long‐term effects of psychedelics. 12 , 16 , 17 , 18 Thus, it is hypothesized that alterations in psychological processes resulting from these altered states of consciousness may play a pivotal role in the therapeutic effects of psychedelics. 19 , 20

Among the most scrutinized altered states of consciousness is the mystical experience. 11 , 15 , 21 , 22 Stace examined reports of mystical experiences across various world religions and identified universal elements independent of religious and cultural contexts. 23 Stemming from this research, a self‐administered 43‐item Mystical Experiences Questionnaire (MEQ43) was devised to assess mystical experiences with psychedelics. 11 , 24 , 25 Subsequently, Maclean et al. developed the MEQ30 as a refined version of the MEQ‐43. 15 Maclean et al. and Barret et al. tested the reliability and validity of the MEQ30, demonstrating high internal consistency and robust divergent, internal, and external validity. 15 , 22

Each item of the MEQ30 is rated on a 6‐point scale, where 0 = “none; not at all,” 1 = “so slight cannot decide,” 2 = “slight,” 3 = “moderate,” 4 = “strong (equivalent in degree to any previous strong experience or expectation of this description),” and 5 = “extreme (more than ever before in my life and stronger than 4).” The MEQ30 consists of four subscales: mystical, positive mood, transcendence of time/space, and ineffability. Scale scores for each participant are computed from the average of responses to all items within a given scale. 15 , 22

Previous studies have reported that a higher MEQ30 total score following psilocybin treatment predicted favorable long‐term outcomes in people with cancer‐related distress, 12 , 16 those seeking smoking cessation, 2 and those with alcohol dependence. 26 Self‐administered scales need to be prepared in each language to conduct clinical trials globally. However, a Japanese version of the MEQ30 has not yet been developed. The aim of this study was to develop a Japanese version of the MEQ30.

2. METHODS

We created a Japanese version of the MEQ30 by translating the original English version of the MEQ30, based on the “Principles of Good Practice for the Translation and Cultural Adaptation Process for Patient‐Reported Outcomes (PRO) Measures: Report of the ISPOR Task Force for Translation and Cultural Adaptation”. 27

Initially, we procured formal permission for the translation from the original authors of the MEQ30. Two native Japanese psychiatrists then independently undertook the forward translation from English to Japanese. We compared these translations and produced a single, reconciled forward‐translated version. This version was subsequently back‐translated into English by a professional translator who is a native English speaker. To assess the quality of the forward translation, the original authors of the MEQ30 compared the back‐translated version with the original version and evaluated it for equivalence. In case of discrepancies, the forward translators scrutinized the forward‐ and back‐translation processes. We iterated on these processes, communicating with the original authors, until the revised forward‐ and back‐translated versions received approval.

3. RESULTS

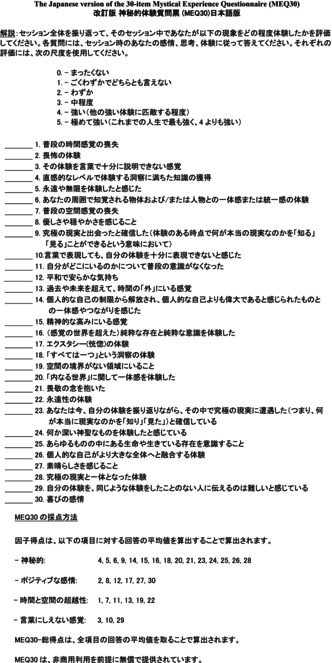

The original author‐approved, back‐translated MEQ30 is depicted in Figure 1. Furthermore, the authorized Japanese version of the MEQ30 is provided in the Appendix A.

FIGURE 1.

The original author‐approved, back‐translated version of the revised Mystical Experience Questionnaire (MEQ30).

4. DISCUSSION

In this study, we developed a Japanese version of the MEQ30, adhering to the “Principles of Good Practice for the Translation and Cultural Adaptation Process for PRO Measures: Report of the ISPOR Task Force for Translation and Cultural Adaptation.”

Given the rising global interest in psychedelic research, creating a Japanese version of the self‐administered MEQ30 is imperative. It is also crucial to assess the reliability and validity of the Japanese version of the MEQ30 when applying this scale to the Japanese populace. Regarding reliability, Maclean et al. reported that estimates of alpha reliability (Cronbach's alpha) were 0.933, 0.926, 0.831, 0.810, and 0.800 for the total score and the four subscales (mystical, positive mood, time/space, and ineffability) of the original MEQ30, respectively, indicating good internal consistency for these scales. 15 For validity, Maclean et al. showed that participants reporting mystical experiences had significantly higher total scores (p < 0.001) on all MEQ30 subscales compared to those not reporting any mystical experiences, implying good divergent validity of the original MEQ30. 15 To date, clinical trials for psychedelic‐assisted therapy have not been conducted in Japan. Therefore, feasibility studies are needed to evaluate its efficacy and safety and to characterize the mystical experience using the MEQ30 in a Japanese population. Upon data collection, the reliability and validity of the Japanese version of the MEQ30 should be confirmed.

In conclusion, we have developed a Japanese version of the MEQ30, which will help capture the mystical experiences induced by psychedelics in Japanese speakers. Future psychedelic research is needed to test the reliability and validity of this scale.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Dr. Yonezawa and Dr. Tani were involved in Conceptualization, translation, writing. Dr. Nakajima was involved in conceptualization, translation, project administration, supervision. Dr. Uchida was involved in conceptualization, methodology, project administration, supervision, writing. All authors have approved the final version of the manuscript.

FUNDING INFORMATION

This research was supported by the Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development (AMED) under grant numbers 22dk0307105h0001 and 23dk0307120h0001 (H.T., S.N., and H.U.).

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

Dr. Yonezawa has received manuscript fees from Sumitomo Pharma and Wiley Japan within the past 3 years. Dr. Tani has received manuscript or speaker fees from Sumitomo Pharma, Janssen Pharmaceutical, Otsuka Pharmaceutical, Takeda, Wiley Japan, and Yoshitomi Yakuhin within the past 3 years. Dr. Miura declares no conflict of interest. Dr. Nakajima has received grants from Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (18H02755, 22H03002), Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development (AMED), Japan Research Foundation for Clinical Pharmacology, Naito Foundation, Takeda Science Foundation, Uehara Memorial Foundation, Watanabe Foundation, and Osake‐no‐Kagaku Foundation within the past 3 years. Dr. Nakajima has received an investigator‐initiated clinical study grant from Asahi Quality & Innovations, Ltd. Dr. Nakajima has received research support, manuscript fees or speaker's honoraria from Sumitomo Pharma, Meiji‐ Seika Pharma, Otsuka Pharmaceutical, and MSD within the past 3 years. Dr. Uchida has received grants from Daiichi Sankyo, Eisai, Mochida, Otsuka, and Sumitomo Pharma; speaker's fees from Eisai, Janssen, Lundbeck, Meiji Seika Pharma, Otsuka, and Sumitomo Pharma; and advisory board fees from Lundbeck, Sumitomo Pharma, Takeda Pharmaceutical Company, and Boehringer Ingelheim Japan.

ETHICS STATEMENT

Approval of the research protocol by an Institutional Reviewer Board: N/A.

Informed consent: N/A.

Registry and the registration no. of the study/trial: N/A.

Animal studies: N/A.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to thank Drs Barrett and Griffiths for their support in reviewing the back‐translation.

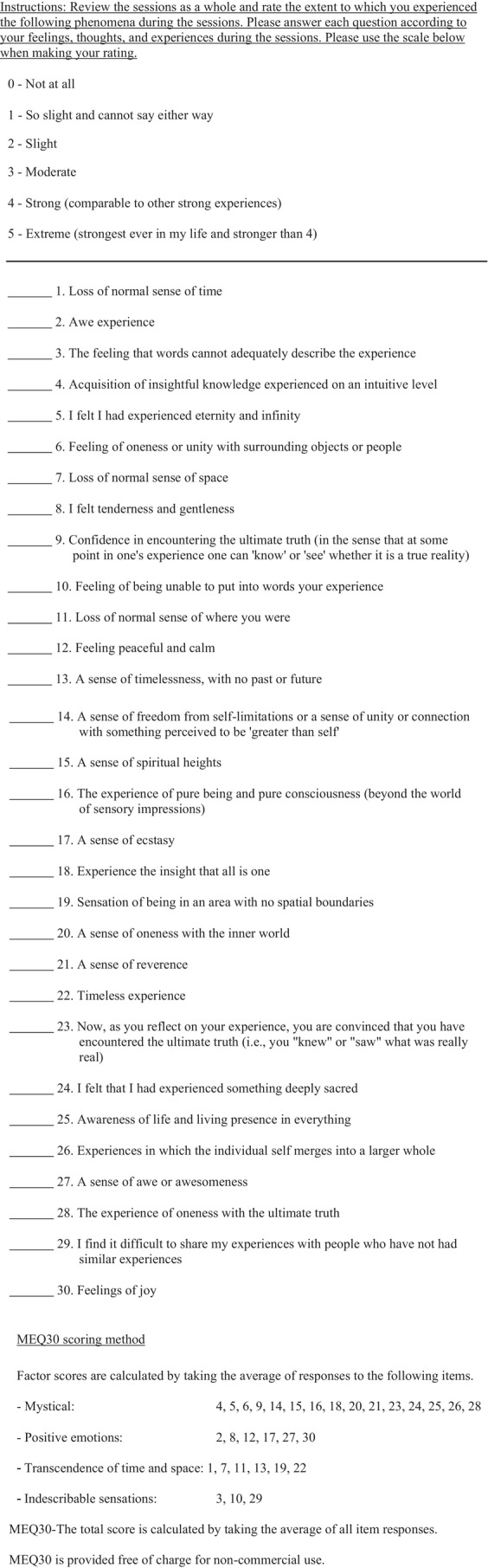

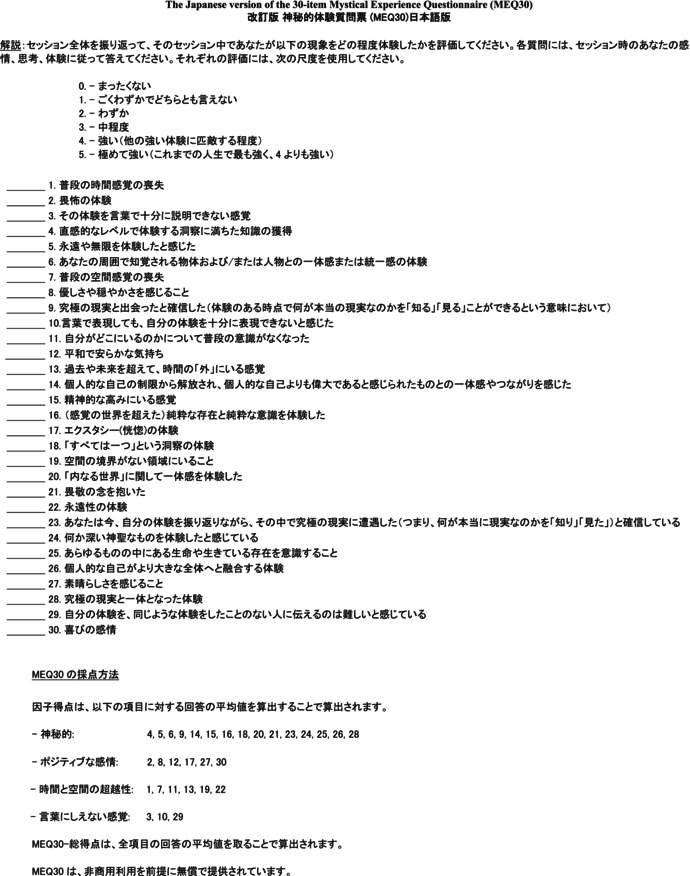

APPENDIX A.

A.1.

Yonezawa K, Tani H, Nakajima S, Uchida H. Development of the Japanese version of the 30‐item Mystical Experience Questionnaire. Neuropsychopharmacol Rep. 2024;44:280–284. 10.1002/npr2.12377

Kengo Yonezawa and Hideaki Tani contributed equally to this work.

REFERENCES

- 1. Goodwin GM, Aaronson ST, Alvarez O, Arden PC, Baker A, Bennett JC, et al. Single‐dose psilocybin for a treatment‐resistant episode of major depression. N Engl J Med. 2022;387(18):1637–1648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Johnson MW, Garcia‐Romeu A, Griffiths RR. Long‐term follow‐up of psilocybin‐facilitated smoking cessation. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2017;43(1):55–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Holze F, Gasser P, Müller F, Dolder PC, Liechti ME. Lysergic acid diethylamide‐assisted therapy in patients with anxiety with and without a life‐threatening illness: a randomized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled phase II study. Biol Psychiatry. 2023;93(3):215–223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Carhart‐Harris R, Giribaldi B, Watts R, Baker‐Jones M, Murphy‐Beiner A, Murphy R, et al. Trial of psilocybin versus escitalopram for depression. N Engl J Med. 2021;384(15):1402–1411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Davis AK, Barrett FS, May DG, Cosimano MP, Sepeda ND, Johnson MW, et al. Effects of psilocybin‐assisted therapy on major depressive disorder: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2021;78(5):481–489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Agin‐Liebes GI, Malone T, Yalch MM, Mennenga SE, Ponté KL, Guss J, et al. Long‐term follow‐up of psilocybin‐assisted psychotherapy for psychiatric and existential distress in patients with life‐threatening cancer. J Psychopharmacol. 2020;34(2):155–166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Sakurai H, Yonezawa K, Tani H, Mimura M, Bauer M, Uchida H. Novel antidepressants in the pipeline (phase II and III): a systematic review of the US clinical trials registry. Pharmacopsychiatry. 2022;55(4):193–202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Nichols DE, Walter H. The history of psychedelics in psychiatry. Pharmacopsychiatry. 2021;54(4):151–166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kelmendi B, Kaye AP, Pittenger C, Kwan AC. Psychedelics. Curr Biol. 2022;32(2):R63–R67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Reiff CM, Richman EE, Nemeroff CB, Carpenter LL, Widge AS, Rodriguez CI, et al. Psychedelics and psychedelic‐assisted psychotherapy. Am J Psychiatry. 2020;177(5):391–410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Griffiths RR, Richards WA, McCann U, Jesse R. Psilocybin can occasion mystical‐type experiences having substantial and sustained personal meaning and spiritual significance. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2006;187(3):268–283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ross S, Bossis A, Guss J, Agin‐Liebes G, Malone T, Cohen B, et al. Rapid and sustained symptom reduction following psilocybin treatment for anxiety and depression in patients with life‐threatening cancer: a randomized controlled trial. J Psychopharmacol. 2016;30(12):1165–1180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Peill JM, Trinci KE, Kettner H, Mertens LJ, Roseman L, Timmermann C, et al. Validation of the psychological insight scale: a new scale to assess psychological insight following a psychedelic experience. J Psychopharmacol. 2022;36(1):31–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Davis AK, Barrett FS, So S, Gukasyan N, Swift TC, Griffiths RR. Development of the psychological insight questionnaire among a sample of people who have consumed psilocybin or LSD. J Psychopharmacol. 2021;35(4):437–446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Maclean KA, Leoutsakos J‐MS, Johnson MW, Griffiths RR. Factor analysis of the mystical experience questionnaire: a study of experiences occasioned by the hallucinogen psilocybin. J Sci Study Relig. 2012;51(4):721–737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Griffiths RR, Johnson MW, Carducci MA, Umbricht A, Richards WA, Richards BD, et al. Psilocybin produces substantial and sustained decreases in depression and anxiety in patients with life‐threatening cancer: a randomized double‐blind trial. J Psychopharmacol. 2016;30(12):1181–1197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Roseman L, Nutt DJ, Carhart‐Harris RL. Quality of acute psychedelic experience predicts therapeutic efficacy of psilocybin for treatment‐resistant depression. Front Pharmacol. 2017;8:974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Aday JS, Mitzkovitz CM, Bloesch EK, Davoli CC, Davis AK. Long‐term effects of psychedelic drugs: a systematic review. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2020;113:179–189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Carhart‐Harris RL. Serotonin, psychedelics and psychiatry. World Psychiatry. 2018;17(3):358–359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Carhart‐Harris RL, Roseman L, Haijen E, Erritzoe D, Watts R, Branchi I, et al. Psychedelics and the essential importance of context. J Psychopharmacol. 2018;32(7):725–731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Griffiths RR, Johnson MW, Richards WA, Richards BD, McCann U, Jesse R. Psilocybin occasioned mystical‐type experiences: immediate and persisting dose‐related effects. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2011;218(4):649–665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Barrett FS, Johnson MW, Griffiths RR. Validation of the revised mystical experience questionnaire in experimental sessions with psilocybin. J Psychopharmacol. 2015;29(11):1182–1190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Stace WT. Mysticism and philosophy. New York: The MacMillan Press; 1960. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Pahnke WN. Psychedelic drugs and mystical experience. Int Psychiatry Clin. 1969;5(4):149–162. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Richards WA. Counseling, peak experiences and the human encounter with death: an empirical study of the efficacy of DPT‐assisted counseling in enhancing quality of life of persons with terminal cancer and their closest family members. The Catholic University of America. Washington: 1975. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Bogenschutz MP, Forcehimes AA, Pommy JA, Wilcox CE, Barbosa PCR, Strassman RJ. Psilocybin‐assisted treatment for alcohol dependence: a proof‐of‐concept study. J Psychopharmacol. 2015;29(3):289–299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Wild D, Grove A, Martin M, Eremenco S, McElroy S, Verjee‐Lorenz A, et al. Principles of good practice for the translation and cultural adaptation process for patient‐reported outcomes (PRO) measures: report of the ISPOR task force for translation and cultural adaptation. Value Health. 2005;8(2):94–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]