Abstract

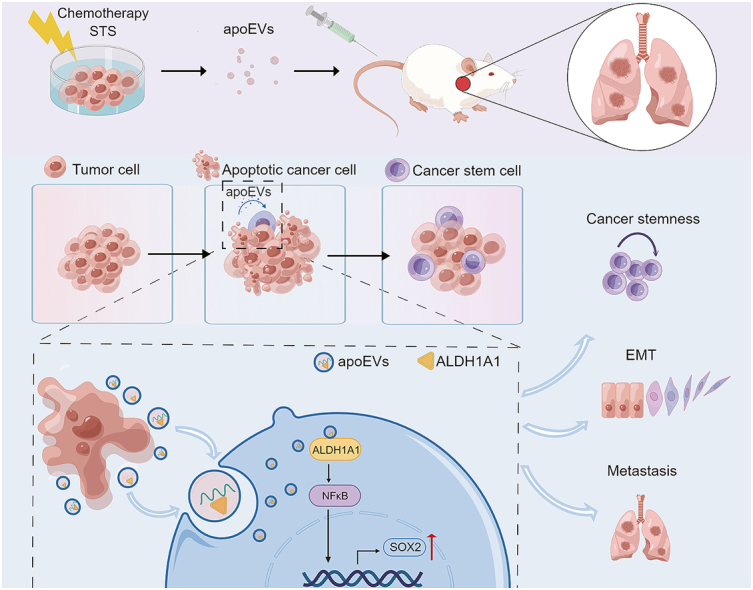

Apoptosis has long been recognized as a significant mechanism for inhibiting tumor formation, and a plethora of stimuli can induce apoptosis during the progression and treatment of tumors. Moreover, tumor-derived apoptotic extracellular vesicles (apoEVs) are inevitably phagocytosed by live tumor cells, promoting tumor heterogeneity. Understanding the mechanism by which apoEVs regulate tumor cells is imperative for enhancing our knowledge of tumor metastasis and recurrence. Herein, we conducted a series of in vivo and in vitro experiments, and we report that tumor-derived apoEVs promoted lung adenocarcinoma (LUAD) metastasis, self-renewal and chemoresistance. Mechanistically, we demonstrated that apoEVs facilitated tumor metastasis and stemness by initiating the epithelial-mesenchymal transition program and upregulating the transcription of the stem cell factor SOX2. In addition, we found that ALDH1A1, which was transported by apoEVs, activated the NF-κB signaling pathway by increasing aldehyde dehydrogenase enzyme activity in recipient tumor cells. Furthermore, targeting apoEVs-ALDH1A1 significantly abrogated these effects. Collectively, our findings elucidate a novel mechanism of apoEV-dependent intercellular communication between apoptotic tumor cells and live tumor cells that promotes the formation of cancer stem cell-like populations, and these findings reveal that apoEVs-ALDH1A1 may be a potential therapeutic target and biomarker for LUAD metastasis and recurrence.

Keywords: Lung adenocarcinoma, Apoptotic extracellular vesicles, Stemness, Proteomics, SOX2

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

SOX2 is associated with the recurrence and cancer stem cell of residual lung adenocarcinoma after classical treatment.

-

•

Tumor-derived apoEVs promote the metastasis and stemness of lung adenocarcinoma in vivo and in vitro.

-

•

Tumor-derived apoEVs deliver protein cargo ALDH1A1 promote the EMT phenotype and SOX2 transcription in lung adenocarcinoma.

-

•

Targeting apoEVs-ALDH1A1 inhibits tumor metastasis and stemness, and increases chemosensitivity.

1. Introduction

Lung cancer is currently the most prevalent malignancy worldwide, and it has the highest mortality rate [1]. Lung adenocarcinoma (LUAD) is the predominant histological subtype of lung cancer, and over half of all lung cancer cases are LUAD cases [2]. Despite the administration of diverse therapeutic approaches to treat patients in the clinic, tumor recurrence and metastasis often result in uncontrolled tumor growth and a subsequent increase in mortality rates. Numerous factors, including metastasis, recurrence, heterogeneity, resistance to chemotherapy and radiotherapy, and the absence of immune surveillance, contribute to the failure of cancer treatment. The characteristics of cancer stem cells (CSCs) offer a comprehensive explanation for such treatment failure [3]. CSCs possess self-renewal and differentiation capacities, which enable them to give rise to diverse cancer subtypes [4]. It is widely acknowledged that CSCs constitute a minor proportion of the cells that are found within primary tumors. Nevertheless, it is important to note that stemness is not an inherent and unalterable characteristic; rather, stemness can be acquired [5]. CSCs are influenced by various factors, such as transcription factors, signaling pathways, and the tumor microenvironment, which collectively impact the proportion and functionality of CSCs [6]. Therefore, understanding how LUAD acquires tumor stemness is vital for improving currently available therapeutic approaches and mitigating tumor recurrence.

SOX2, which is a pivotal transcription factor in CSCs, plays a crucial role in preserving the undifferentiated state of stem cells during their initial phases of development. Notably, investigations have revealed that SOX2 serves as an independent predictor of unfavorable outcomes in stage I LUAD [7]. Recently, Courtney M Schaal et al. found that electronic cigarettes promote the migration and stemness of non-small cell lung cancer cells by enhancing the expression of SOX2 and mesenchymal markers [8]. Additionally, previous research has demonstrated that SOX2 is involved in the regulation of tolerance to EGFR-TKIs, the promotion of tumor metastasis, and the alteration of the immune microenvironment in LUAD [[9], [10], [11]]. However, our understanding of how SOX2 expression is regulated in cancer cells, particularly in LUAD patients after treatment, remains limited.

Apoptotic extracellular vesicles (apoEVs) are particles that are bound by phospholipid bilayer membranes and are generated during apoptosis; these vesicles contain nucleic acids, proteins and other metabolites [[12], [13], [14]]. Previous studies have confirmed that apoEVs are different from exosomes in terms of size, morphology, density, protein composition, and specific biomarkers, and such studies have revealed that apoEVs have more complex contents than exosomes [15]. During the progression of tumor formation and growth, various factors, such as radiotherapy, chemotherapy, targeted therapy, and hypoxia, contribute to tumor cell apoptosis. Consequently, a substantial quantity of tumor-derived apoEVs is found within the tumor microenvironment. These apoEVs may mediate communication between different cancer cell populations, thereby altering tumor heterogeneity and promoting cancer evolution. Despite extensive research on the role of other extracellular vesicles, such as exosomes and microvesicles, in the tumor microenvironment [[16], [17], [18]], little is known about the role of apoEVs in tumor niches. Because CSCs and apoEVs have significant impacts, a better understanding of these relationships is needed.

Here, we used a mouse model and LUAD cells to investigate the involvement of tumor-derived apoEVs in LUAD metastasis and stemness. Our findings indicate that tumor-derived apoEVs activate the NF-κB pathway by increasing aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH) enzyme activity. In addition, tumor-derived apoEVs promote the tumor epithelial-mesenchymal transformation (EMT) phenotype. Furthermore, the stem cell-related transcription factor SOX2 is upregulated via mechanisms that rely on tumor-derived apoEVs, leading to enhanced tumor cell invasion, metastasis and chemotherapy resistance. Finally, targeting apoEVs-ALDH1A1 significantly inhibits the NF-κB pathway, thus inhibiting tumor migration and stemness. These results suggest that NF-κB/SOX2 signaling that is dependent on tumor-derived apoEVs-ALDH1A1 plays a role in LUAD, rendering this process an effective target for tumor recurrence prevention and CSC therapy.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Human samples

A cohort of 79 surgical tumor samples was procured from patients who underwent surgical resection for neoadjuvant chemotherapy in resectable stage III lung adenocarcinoma at the Department of Thoracic Surgery, Sun Yat-sen University Cancer Center, from September 2012 to September 2021. The diagnosis of LUAD was confirmed through bronchoscopy or puncture biopsy, followed by histopathological examination. Before undergoing the surgical procedure, these patients were administered 2–4 cycles of dual-drug chemotherapy containing platinum. In addition, nine samples of resectable stage III lung adenocarcinoma tissues were procured subsequent to neoadjuvant chemotherapy or targeted therapy between the months of January 2022 and July 2023. These samples were subjected to embedding in paraffin wax, while a portion of the fresh samples was lysed to create a single-cell suspension for tumorsphere formation culture in a serum-free stem cell medium. A postoperative follow-up was conducted to obtain clinicopathological characteristics and prognosis information (relevant clinical information of each patient is provided in Supplementary Table 1). This study was approved by the Ethics and Research Committees of the Sun Yat-sen University Cancer Center. The staging of all LUAD cases was conducted according to the eighth edition AJCC cancer staging classification of malignant tumors. The mRNA (RNASeqv2) pre-processed data and clinical information for the TCGA-LUAD cohort were obtained from cBioPortal (www.cBioPortal.org).

2.2. Cell culture

BEAS2b, A549, PC9, HCC827 and H1299 were obtained from ATCC, luciferase labeled A549 (A549-luc) was purchased from Meisen Chinese tissue culture collection (Zhejiang, China), and all these cell lines were cultured according to provider's recommendations. All cells were cultured at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 incubator. Fresh tumor samples were dissociated into single cells using StemPro Accutase (Gibco), subsequently, filtered and resuspended in serum-free stem cells medium (DMEM/F12, 20 ng/ml B-27, 20 ng/ml EGF, 20 ng/ml basic-FGF) as described. Cells were pre-treated with apoEVs or an equivalent volume of PBS before functional assays in vitro. Cells were seeded at a density of 5 × 105 in a 100 mm culture plate and treated with 20 μg/ml of apoEVs per day for 96 h.

2.3. Mice and tumor models

In the tail-vein injection metastasis mouse model, a total of 5 × 105 A549-luc cells were intravenously injected into male 5-week-old NOD/SCID mice. Subsequently, the mice underwent treatment with apoEVs (20 μg in 100 μl PBS) or a comparable volume of PBS via tail vein injection every other day for a duration of 3 weeks. The mice were then monitored using weekly bioluminescence imaging, which was captured by the BLT Aniview600 multimodal animal imaging system (Biolight Biotechnology, Guangzhou, China). At the end of the experiment, dissected lungs were subjected to histological analysis. The frequency of tumor-initiating cells and self-renewal ability of A549-luc cells treated with apoEVs or PBS in vivo were investigated by tumorsphere formation assay in vitro and serial transplantation assays with limiting dilution, in brief, 5-week-old male NOD/SCID mice were subcutaneously injected with a mixture of 1 × 103 pre-treated cells and Matrigel. Eight mice were used in each group. The tumors were defined as tumorigenesis once their diameter reaches 5 mm. The parameters of tumor latency and tumor incidence were documented. In the in vivo and in vitro assay for drug treatment, Disulfiram (DSF) (Selleck) was suspended in a specialized solvent according to the manufacturer's instructions. Following the injection of tumor cells and apoEVs into the tail vein, DSF (50 mg/kg, 5 mg/ml) or an equal volume of the vehicle was orally administered to mice with tumors every 3 days for 3 weeks. All animal-related protocols and procedures were meticulously adhered to at the Animal Experiment Center of Sun Yat-Sen University, in strict accordance with the established guidelines. Furthermore, all animal experimentation conducted at the Sun Yat-Sen University Cancer Center received prior approval from the Experimental Animal Ethics Committee.

2.4. Generation of stable cell lines

To silencing ALDH1A1 in LUAD cell lines, shRNA sequences of ALDH1A1 were cloned into the pLKO.1-U6-scramble vector (IGE Biotechnology, Ltd, Guangzhou, China). The complete list of shRNA sequences can be found in Supplementary Table S2. The lentiviruses were used to infect the cell lines, resulting in the establishment of stable cell lines. After 24 h of transfection, the cells were subjected to selection in media supplemented with 2 μg/ml puromycin (Gibco). The efficacy of gene silencing was confirmed through the utilization of qRT-PCR and Western blot analysis employing an anti-ALDH1A1 antibody. The sh-NC and sh-ALDH1A1 stable transfected cells were employed to induce and isolate apoEVs for subsequent investigation.

2.5. Isolation and validation of apoEVs

Since we tried to investigate the function of apoEVs produced by a wide range of apoptosis phenomena is not limited to chemotherapy, we used cisplatin (DDP, Beyotime) and Staurosporine (STS, Bioss) to induce LUAD cell apoptosis. After 24 h treatment, differential centrifugation was used to isolate apoEVs from the medium of apoptotic cells. Detailed operation flow is shown as an optimized protocol (Fig. 2a). In brief, apoptotic cell fragments were removed after continuous centrifugation of 800 g at 4 °C for 10 min and 2000 g at 4 °C for 10 min. Next, the supernatant was collected and centrifuged at 4 °C for 16,000 g 30min to obtain apoEVs, then washed twice with sterile PBS. ApoEVs were quantified by measuring the protein concentration via a BSA assay (Beyotime).

Fig. 2.

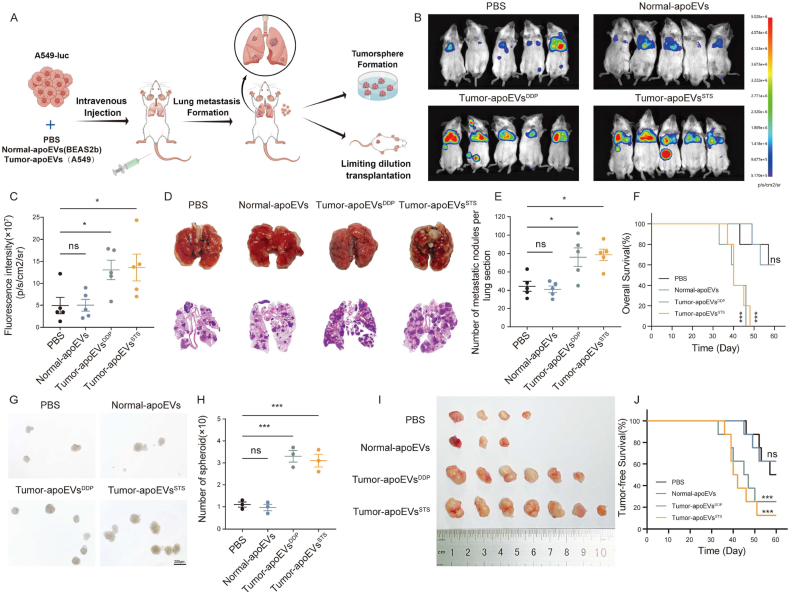

Tumor-derived apoEVs promote metastasis and stemness of LUAD in vivo. (A) Schematic diagram illustrating the procedure of experimental lung metastasis formation assay. (B) Bioluminescence imaging of lung metastasis formation model, which tumor-bearing mice treated with PBS or apoEVs (n = 5). (C) Scatter plot depicting the ROI quantification of A549-luc whole-body metastatic tumor radiance from mice described in (B), tumor-bearing mice treated with PBS was used as control group. (D) Representative images of the lung and H&E staining of tissue sections taken from the lung metastasis formation model. (E) The number of metastatic nodules in lung sections described in (D). (F)Kaplan–Meier plot for the OS of lung metastasis mice from the experiment described in (A), tumor-bearing mice treated with PBS was used as control group, all p values are based on log-rank (Mantel–Cox test). (G, H) Dissociated fresh A549-luc single cells from lung metastasis formation model performing tumorsphere formation assay in vitro. The numbers and volumes of tumorsphere were quantified. (I) Image of tumors formed by 1000 A549-luc cells from lung metastasis formation model before subcutaneous injection into NOD/SCID mice (n = 8). (J) Kaplan–Meier plot for the tumor-free survival of lung metastasis mice from the experiment described in (I), all p values are based on log-rank (Mantel–Cox test). Data represent means ± SEM of three independent experiments. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001; ns., not significant.

The morphology of apoEVs was examined using transmission electron microscopy (TEM), whereby apoEV particles were resuspended in a 1% glutaraldehyde solution. Copper grids coated with Formvar were dripped with samples and incubated for 10 min. Following washing, samples were treated with phosphotungstic acid (PTA) for 3 min. The images were taken with a JEM-1200EX (JEOL, Japan) after drying at room temperature.

To assess the size distribution, nanoparticle tracking analysis (NTA) was conducted employing ZetaView PMX 110 (Particle Metrix, Germany). Record the image after adjusting the sample concentration properly. The measurements encompassed the particle size distribution as well as the potential, then particle size and concentration were calculated using ZetaView software 8.04.02 SP2 (Particle Metrix, Germany). Furthermore, apoEVs were diluted in PBS, and identified surface markers using an ACEA NovoCyte flow cytometer (ACEA Biosciences, USA) according to the manufacturer's protocol. ApoEVs derived from LUAD cell lines and Human Normal Lung Epithelial Cells BEAS2b were incubated with PE-conjugated anti-CD9, CD63 and CD81 (Elabscience), the general EV markers, at 4 °C for 30 min. To detect phosphatidylserine (Ptdser), FITC-Annexin V was used to stain apoEVs suspended in Annexin V Binding Buffer (Elabscience) for 15 min at 4 °C. Western blot was used to detect apoptosis-associated markers cleaved caspase-3 in apoEVs.

2.6. RNA extraction, RT-qPCR, and RNA sequencing

TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, California, USA) was used to extract total RNA from cells following the manufacturer's instructions. We measured the concentration of RNA using NanoDrop 2000 (Thermo Fisher Scientific). For cDNA synthesis, HiScript II cDNA Synthesis Kit (Vazyme, China) was used. Real-time quantitative PCR was performed for gene expression analysis using 2X SYBR Green qPCR Master Mix (APExBIO, Houston, USA), as previously described [19]. GAPDH was utilized as a normalization control, and mRNA expression was analyzed using a ΔΔCt method. We list the primers used for PCR In Supplementary Table 3.

Total RNA from the A549 cells treated with PBS or apoEVs for 96 h in vitro was extracted using TRIzol reagent, and RNA sequencing was performed by Novogene Co., Ltd (Beijing, China). Using the R program (version 4.1.1, http://www.R-project.org), transcriptional analysis was conducted, and to identify differentially expressed genes (DEGs) in different clusters, the "limma" package was utilized. In order to analyze functional enrichments using Gene Ontology (GO) and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) databases, the R package “clusterProfiler” was used. The gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) was conducted using GSEA software (version 3.0) downloaded from the GSEA website (http://software.broadinstitute.org/gsea/index.jsp), then we used the annotation of Hallmark gene sets to identify potential biological functions (https://www.gsea-msigdb.org/gsea/msigdb/index.jsp).

2.7. Colony formation assay

We seeded LUAD cells into 6-well plates at a density of 1 × 103 cells per well and incubated them for a duration of two weeks. Following fixation with 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) for 20 min, the cells were then stained with 1% crystal violet for 30 min. We quantified the number of colony-forming using Image J software.

2.8. Migration and invasion assays

The migration effect of A549 and HCC827 cells treated with apoEVs or PBS was assessed by wound-healing assay and transwell assay as described earlier [20]. In brief, A549 or HCC827 cells were seeded into 6-well plates using DMEM medium supplemented with 10% FBS. Upon reaching 90% cell density, the cells were subjected to serum deprivation by replacing the medium with serum-free DMEM, then, we scratched up the cell monolayers and gently washed them with serum-free DMEM by using a pipette tip. Images were captured at the 48-h time point. For transwell assay, we placed a Matrigel chamber (Corning, USA) in a 24-well plate containing serum medium for 30 min at 37 °C. A total of 5 × 104 LUAD cells resuspension with serum-free medium were added to the upper compartment of a transwell chamber. 24 hours later, the upper basement membrane cells were gently wiped off using cotton swabs. In the last step, we fixed the cells with paraformaldehyde and stained them with crystal violet staining solution (1%). Images were analyzed by Image J.

2.9. Tumorsphere formation assay

For the in vitro tumorsphere formation assay, cells were plated in ultralow attachment 24-well dishes (Corning, NY) and serum-free stem cell medium as described earlier. 1 × 103 cells in 300 μl of stem cell medium were seeded into each well and incubated for about two weeks. 30 μl of stem cell medium supplement was added every two days until the end of the experiment. The number of spheroids formed in the first passage was counted and recorded under a light microscope. The spheroid from the first passage was collected through a 70 μm cell strainer and dissociated with StemPro Accutase. The stem cell medium has been resuspended after centrifugation for 5 min at 1500 rpm, 1 × 103 cells were seeded into each well and incubated for another two weeks. Similarly, spheroids formed during the second passage were counted and recorded under the light microscope.

2.10. Apoptosis assay

LUAD cell lines were co-cultured with either PBS or apoEVs for a duration of 96 h. Subsequently, these cells were further cultured in EV-free DMEM supplemented with cisplatin (DDP) for an additional 24 h. All dead cells in supernatant together with trypsinized cells were counted and 5 × 105 cells were used for each analysis. Following this, FITC-Annexin V and propidium iodide (PI) (Elabscience Biotechnology Co., Ltd) were used to stain the cells at room temperature in the dark for 15 min. The control set-up and fluorescent compensation were performed with unstained and stained (Annexin V-FITC and PI) cells. The cell suspension was topped up to 200 μl with binding buffer before subjecting to a cell analyzer by cytoFLEX flow cytometer (Beckman Coulter, Inc.). Apoptosis assay results were analyzed by FlowJo software (10.8.1) (BD biosciences, USA).

2.11. ALDFOUR assay and fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS)

The activity of the ALDH enzyme was detected by performing the Aldehyde Dehydrogenase assay using the ALDEFLUOR Assay Kit (STEMCELL Technologies, Vancouver, CA) following the manufacturer's instructions. The ALDH + cells were quantified using a cytoFLEX flow cytometer (Beckman Coulter, Inc.) and analyzed using FlowJo software (10.8.1) (BD biosciences, USA) according to the manufacturer's recommendations, cells treated with Diethylaminoazobenzene (DEAB) reagent serving as a negative control. FACS was conducted with a BD FACSmelody Cell Sorter (BD Biosciences) and the data were analyzed using BD FACSChorus software (BD Biosciences).

2.12. diaPASEF proteomic analysis

Parallel accumulation-serial fragmentation combined with data-independent acquisition (diaPASEF) mode can use an extremely small protein sample to present deep proteome coverage, reproducibility, and quantitative accuracy [21]. Compared with the traditional data-independent acquisition modes, the diaPASEF process can follow an accurate quantitative proteome in extracellular vesicles. We prepared protein lysates of apoEVs as described in previous studies [22], and proteomic analysis was performed by Personalbio Technology Co., Ltd (Shanghai, China). Briefly, we obtained mass spectrometry (MS) data using the timsTOF Pro (Bruker) in two different acquisition modes: data-independent acquisition (DIA) and data-dependent acquisition (DDA). The DDA data was utilized to construct a Spectral Library through the employment of Spectronaut software (SpectronautTM 14.4.200727.47,784). To identify proteins from the UniProt database, a false discovery rate (FDR) of 1% was implemented for both peptides and proteins. DIA data are processed by Spectronaut software. The mass spectrometry proteomics data had been deposited to the Integrated Proteome Resources Database with the dataset identifier IPX0006839001.

For proteomic bioinformatics analysis, in order to screen apoEVs protein cargo accurately, only proteins quantified in at least two out of three biological replicates in all the apoEVs were considered. KEGG and GO databases were used to analyze the functional characteristics of proteins that were significantly upregulated in apoEVs (fold change >2 and FDR <0.05). The proteomaps were created based on t-test difference values without converting them into log2 values [23]. Prediction of subcellular localization was performed by CELLO (http://cello.life.nctu.edu.tw/). The Protein-Protein Interaction (PPI) network analysis was conducted using the STRING database [24], and visualized using Cytoscape (version 3.9.1) [25].

2.13. Western blot analysis

Cells were lysed in Cell lysis buffer supplemented with protease and phosphatase inhibitor (Beyotime Biotechnology). The protein quantity was determined using the BSA assay provided by Beyotime Biotechnology. Electrophoresis was performed on 10% or 12% SDS-PAGE gels to separate the proteins, which were then transferred onto polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membranes (Millipore). To prevent non-specific binding, the PVDF membranes were treated with a protein-free rapid-blocking buffer (Epizyme Biomedical Technology Co., Ltd) for a duration of 30 min. The membranes were subsequently exposed to primary antibodies and secondary antibodies (Supplementary Table 4), and antibodies were used at the dilutions indicated by the manufacturer. Proteins were detected using BLT GelView 6000 Pro multifunctional imaging station (Biolight Biotechnology, Guangzhou, China). Chemiluminescent signals were detected by ECL™ Western Blotting substrate (fg-level) (Affinity Biosciences, ltd.).

2.14. Immunohistochemistry and immunofluorescence staining

Tissue sections made from paraffin-embedded surgical specimens or tumor tissues from animal experiments were deparaffinized in xylene and rehydrated. The tissue slides were subjected to treatment with citrate buffer and subsequent blocking with 2% BSA to prevent any potential non-specific binding of antibodies. The samples were incubated overnight at a temperature of 4 °C with the primary antibodies (Supplementary Table 4), and then further incubated with secondary antibody (Alex Fluor 488/594–conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG; Alexa Fluor 488/594–conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG, Immunoway) for 20 min, nuclear staining was then performed using DAPI for 10 min. Five random images were captured utilizing a Nikon Eclipse Ti2 microscope (Nikon), and subsequent analysis was conducted employing ImageJ software (NIH).

For immunofluorescence staining of tumor cells cultured in vitro, LUAD cell lines were cultured with apoEVs or PBS. Afterward, cells were fixed with 4% PFA in PBS for 15 min, followed by permeabilization using 0.1% Triton X-100 for 5 min. Subsequently, the sample was washed in PBS before being blocked in PBS with 2% BSA for 60 min. Then cells were incubated with rabbit anti-human E-cadherin (1:200, Hangzhou HuaAn Biotechnology Co., Ltd), rabbit anti-human Vimintin (1:200, Hangzhou HuaAn Biotechnology Co., Ltd), rabbit anti-human SOX2 (1:200, Immunoway Biotechnology Co., Ltd) overnight at 4 °C. After incubation with secondary antibody for 1 h at room temperature, DAPI was used to stain the cells. The FV1000 confocal laser scanning biological microscope (Olympus) or Nikon Eclipse Ti2 microscope (Nikon) were used to acquire and analyze the images. Thereafter, the acquisition and analysis of images were performed by immunofluorescence as previously described.

Immunohistochemistry (IHC) was conducted on paraffin sections of LUAD tissues or animal tumors using SP Rabbit & Mouse HRP Kit (Cwbio, China) following the manufacturer's instructions. In order to assess the intensity and proportion within the entire section, we use a grading scale of 0 (no staining), 1 (light yellow), 2 (yellow), and 3 (dark yellow). The total score for the detected protein was calculated as the sum of the proportion multiplied by the intensity score.

2.15. Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 9.0, R (version 4.1.1, http://www.R-project.org), and SPSS 19.0. Kaplan-Meier analysis was utilized to evaluate the overall survival of patients. Differential expression analysis was conducted using an unpaired two-tailed t-test in R for the transcriptomes and quantitative proteomics study; Adjusted p-values were calculated by correcting for false discovery rate using the Benjamini-Hochberg method. Two-group comparisons were conducted using Student's t-test, while one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by two-tailed t-tests were employed to determine differences among three or more groups. Except for the exceptions described in the figure legends, experiments with independent cohorts of animal were usually conducted only once. Each animal is represented by a dot in the figures during animal experiments. All experiments in vitro were replicated a minimum of three times. Each experiment was conducted multiple times with similar results. The figure legends indicate the quantity of biological replicates for each experiment. The data were presented as the mean ± SEM. A significance level of p < 0.05 was deemed statistically significant. The statistical significance of the data is summarized as follows: *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

3. Results

3.1. Isolation and characterization of apoEVs from BEAS2b and LUAD cells

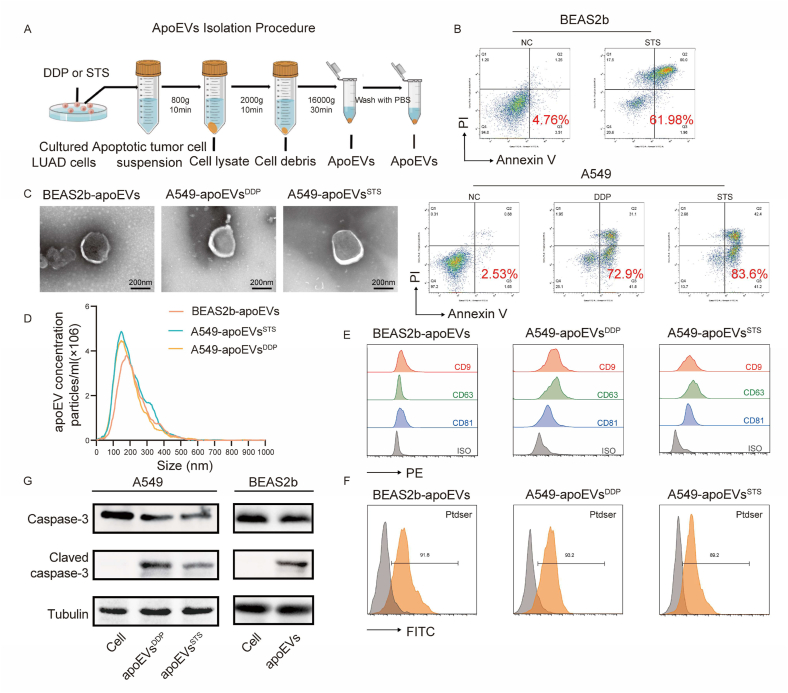

After exposure to chemotherapy, radiotherapy or targeted therapy, tumor cells undergo apoptosis within a brief timeframe, resulting in the appearance of a substantial number of apoptotic vesicles. Due to the robust endocytic capability of tumor cells, these apoEVs are initially engulfed by the remaining tumor cells. This process has the potential to induce changes in the biological functionality of neighboring cells and consequently promote tumor heterogeneity. This study attempted to explore the biological hypotheses described above after cells were treated with different inducers of apoptosis. We induced apoptosis in the A549 LUAD cell line with cisplatin (DDP) and staurosporine (STS), and subsequently, apoEVs were extracted through differential centrifugation (Fig. 1A and B). To enhance the examination of functional disparities and evaluate the functional constituents within tumor-derived apoEVs, we also isolated apoEVs from the BEAS2b normal lung epithelial cell line (Normal-apoEVs) for comparative purposes. To authenticate the characteristics of the apoptotic vesicles that were extracted, their morphology and size were assessed using transmission electron microscopy (TEM); the results revealed that apoEVs exhibited a double-membrane spherical configuration (Fig. 1C). Nanoparticle tracking analysis confirmed that the apoEVs had a size that peaked at approximately 170–200 nm (Fig. 1D). Flow cytometric analysis confirmed the high expression of common markers of extracellular vesicles (EVs), including CD9, CD63, and CD81 (Fig. 1E). In addition, flow cytometric analysis also revealed the presence of a specific surface marker, namely, phosphatidylserine (PtdSer), and its expression on apoEVs was detected with FITC-Annexin V (Fig. 1F). Western blotting further revealed the presence of cleaved caspase-3, which is a specific apoptosis-associated product, in apoEVs (Fig. 1G). These findings provide solid evidence that the apoEVs that were examined in this study possess the classical characteristics of apoptotic vesicles [26].

Fig. 1.

Characteristics of apoptotic extracellular vesicles (apoEVs) derived from LUAD cells and normal lung epithelial cells. (A) Schematic diagram of apoEVs isolation. A549 and BEAS2b are induced by STS or Cisplatin (DDP) for 24 h and then apoptotic cell suspensions are isolated using a differential centrifugation to obtain apoEVs. (B) Representative flow cytometry analysis of BEAS2b apoptosis after STS treatment, and A549 apoptosis after Cisplatin (DDP) and STS treatment. (C) Representative TEM micrographs of apoEVs collected from the conditioned medium after apoptosis induction treatment of A549 and BEAS2b cells evaluated are shown. Scale bar, 200 nm. (D) Size distribution of BEAS2b- and A549-apoEVs were measured by nanoparticle tracking analyzer (NTA). (E) Representative histograms show the profile of the CD9, CD63 and CD81 levels in comparison to isotype control-stained for the BEAS2b and A549-derived apoEVs. (F) Nanoflow cytometry show apoEVs express apoptotic vesicles-specific surface markers Ptdser (shown by Annexin V staining). (G) Western blot of the indicated proteins in apoEVs, Tubulin (loading control) were used, western blotting was repeated at least three times and representative data are shown.

3.2. Tumor-derived apoEVs promote the metastasis and stemness of LUAD in vivo

To investigate the potential effect of apoptotic tumor cell-derived apoEVs on live tumor cells and to evaluate the potential contribution of this intercellular communication to tumor metastasis, we established an experimental model of lung metastasis. Specifically, we administered A549 cells that were stably transfected to express luciferase (A549-luc) into immunodeficient (NOD/SCID) mice via caudal vein injection. To observe the biological functionality of tumor-derived apoEVs, we administered PBS or various types of apoEVs. We investigated whether recipient tumor cells could engulf apoEVs in vivo. Immunofluorescent staining revealed the presence of PKH26-labeled apoEVs within the lung metastatic tumor tissue of tumor-bearing mice 24 h after infusion (Fig. S1). Subsequently, we assessed metastasis through bioluminescence imaging 28 days after tumor cell injection, and we continued to monitor the overall survival of the mice (Fig. 2A). According to the bioluminescence results, no discernible difference was observed in the development of lung metastasis between mice that were injected with normal-apoEVs and those that were injected with PBS (Fig. 2B–C). Interestingly, DDP- and STS-induced A549-derived apoEVs (Tumor-apoEVsDDP and Tumor-apoEVsSTS, respectively) enhanced the formation of metastatic tumors (Fig. 2B–E). In addition, it was observed that the presence of tumor-apoEVs shortened the survival time of mice in the metastatic model (Fig. 2F).

Furthermore, to further investigate the effect of apoEVs on tumor stemness, we isolated LUAD cells from mice that were treated with apoEVs. Subsequently, these cells were cultured in stem cell medium to assess their capacity to form tumorspheres. Concurrently, transplantation assays employing limiting dilution were conducted in NOD/SCID mice to evaluate tumor formation efficiency (Fig. 2G–H). Our findings demonstrate that the tumorspheres that were formed by tumor cells after exposure to tumor-apoEVs in mice exhibited enhanced characteristics (Fig. 2I–J), including the presence of substantial tumor stem cell-like populations. This indicates a significant enhancement of the self-renewal ability of tumor cells. These results suggest that LUAD cells that are exposed to tumor-apoEVs, as opposed to apoEVs derived from normal cells, possess a stronger self-renewal ability, increased stemness, and a propensity to promote tumor metastasis.

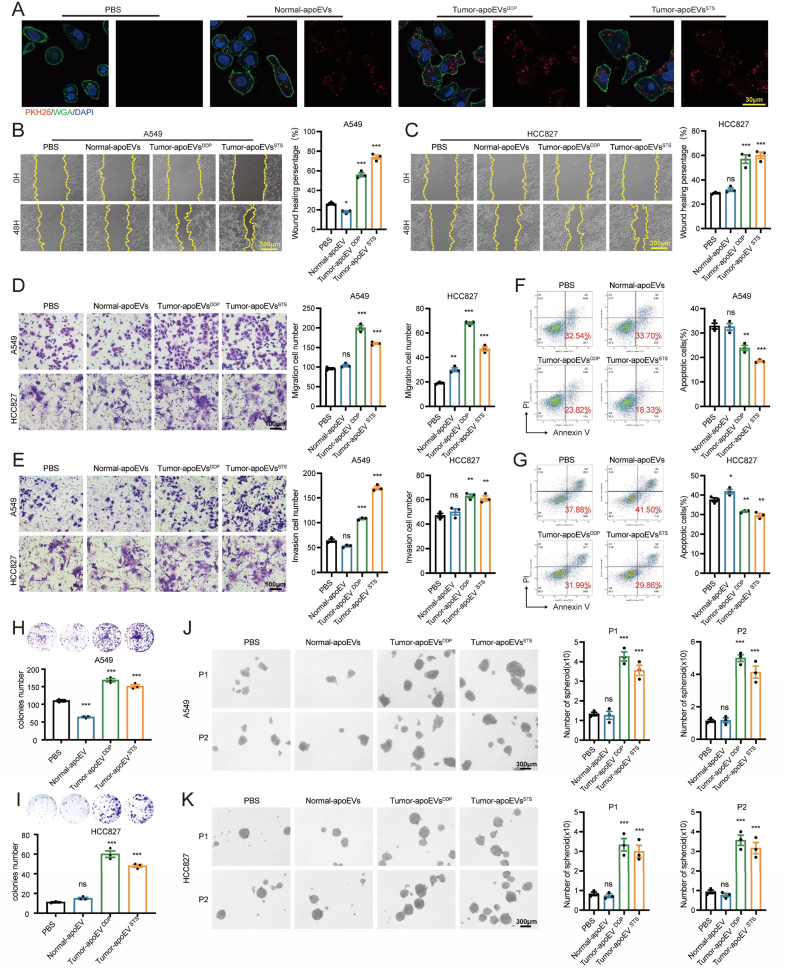

3.3. Tumor-derived apoEVs promote the invasion, migration, chemoresistance and stemness of LUAD cells in vitro

In vitro experiments were performed to evaluate the effect of treatment with PBS, Normal-apoEVs, Tumor-apoEVsDDP and Tumor-apoEVsSTS on LUAD cells. Initially, apoEVs were labeled with the fluorescent dye PKH26 and subsequently added to the LUAD culture medium to investigate their potential to be internalized by LUAD cells. As anticipated, the utilization of a laser-scanning confocal microscope revealed distinct red fluorescence signals in LUAD cells that were treated with various types of apoEVs. Conversely, no fluorescence signals were detected in cells that were treated with PBS, indicating the successful internalization of PKH26-labeled apoEVs by LUAD cells (Fig. 3A). The wound healing assay and Transwell assay demonstrated that compared with normal apoEVs, tumor-derived apoEVs exerted the strongest effect in enhancing cell migration and invasiveness (Fig. 3B–E). Previous studies have indicated that residual tumor cells after treatment often exhibit drug resistance [27,28]; however, the impact of apoEVs on drug resistance warrants further investigation. Therefore, we investigated the effect of apoEVs on tumor drug resistance. According to the study, tumor-derived apoEVs induced cisplatin resistance, but normal apoEVs did not (Fig. 3F–G). In addition, consistent results were observed in vivo, and tumor-apoEVs promote the self-renewal ability of tumor cells, as observed in colony formation and tumorsphere formation assays (Fig. 3H–K). These findings suggest a previously unknown role of tumor-apoEVs in promoting migration, drug resistance and stemness in vitro, and these findings prompted us to further investigate the molecular mechanism underlying this observation.

Fig. 3.

Tumor-derived apoEVs increase migration, chemo-resistance and stemness of LUAD in vitro (A) Representative confocal microscopy images showing uptake of apoEVs (red) by LUAD cells in vitro. Cells nuclear staining with DAPI (blue) and membrane staining with WGA (green). apoEVs were stained with the PKH26 (red). Scalebars, 30 μm. (B, C) Wound healing assays of LUAD cells pre-treated with PBS or apoEVs. Scale bars, 300 μm. (D, E) Migration and invasion assays of LUAD cells pre-treated with PBS or apoEVs. Scale bars, 100 μm. (F, G) Cisplatin-induced apoptosis assay in LUAD cells pre-treated with PBS or apoEVs were stained with PI and Annexin V-FITC. Flow cytometry was conducted to determine the percentage of apoptotic cells. (H–I) Colony formation assay of LUAD cells pre-treated with PBS or apoEVs. (J–K) Tumorsphere formation assay of LUAD cells pre-treated with PBS or apoEVs. Representative photographs of spheroids formed after incubation. The histogram indicates the number of spheres formed per 1000 cells. Scale bars, 300 μm. P1 and P2 represent passage 1 and 2, respectively. LUAD cell lines treated with PBS was used as control group. Data represent means ± SEM of three independent experiments and p values are based on a two-tailed Student's t-test. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001; ns., not significant.

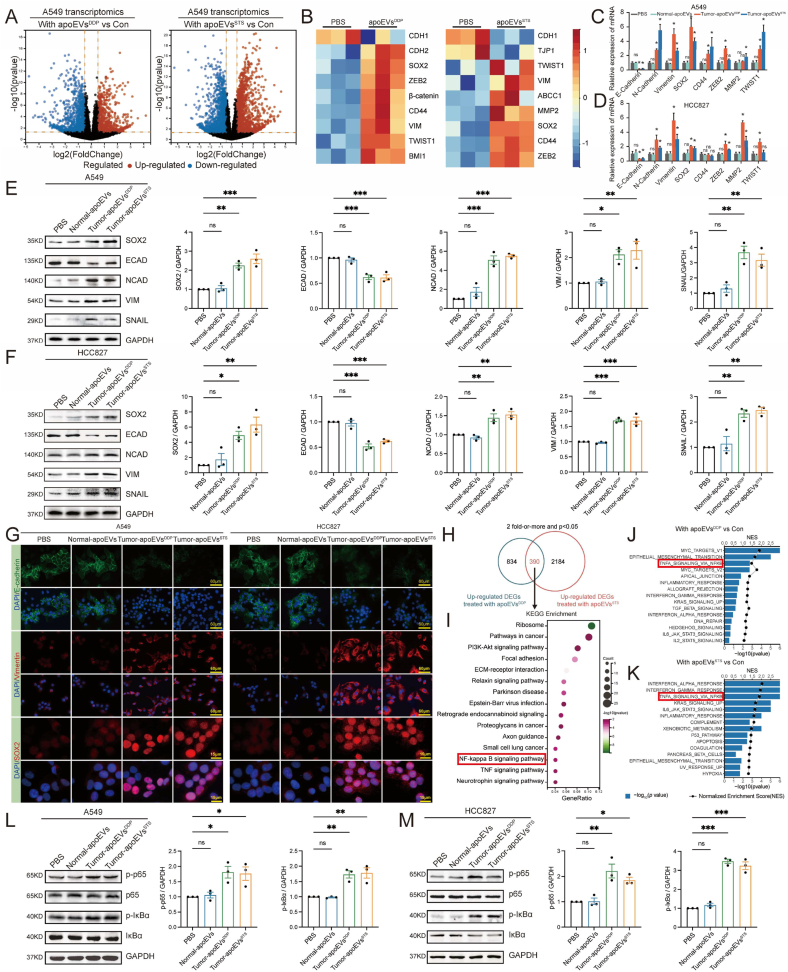

3.4. Tumor-derived apoEVs promote the EMT phenotype and SOX2 transcription in LUAD cells

To further explore how tumor-apoEVs mediate the migration and stemness of LUAD, we analyzed the transcriptome of A549 cells that were treated with tumor-apoEVsDDP or tumor-apoEVsSTS by RNA-seq. Our findings indicate that both types of tumor-apoEVs significantly affected the tumor transcriptome (Fig. 4A). Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) demonstrated a notable enrichment in the epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) phenotype, as shown in Fig. S2. Notably, the heatmap displays the differential expression of EMT-related genes and pluripotency-related genes in cells that were treated with apoEVs (Fig. 4B). The aberrant reactivation of the EMT is a prerequisite for the acquisition of a malignant phenotype in tumor cells, including increased migratory and invasive capabilities, as well as resistance to therapeutic agents [29,30], and reactivation of the EMT also has a complicated relationship with cancer stem cells [31]. Furthermore, selected genes that have been implicated in EMT and stemness were selected to individually verify their expression patterns via real-time quantitative PCR (Fig. 4C–D). As expected, EMT-related genes and SOX2 were significantly upregulated by treatment with tumor-apoEVs compared with PBS or normal-apoEVs.

Fig. 4.

Tumor-apoEVs activate EMT phenotype and NF-κB/SOX2 signaling in LUAD cells. (A) Volcano plots indicating differentially expressed genes between A549 pretreated with A549-apoEVsDDP or A549-apoEVsSTS compared with PBS-treated A549 (A549-Con). Significant differences (log2 fold-change >0.5, FDR <0.05) are indicated in red (up-regulated) and blue (down-regulated), RNA-seq was performed using biologically independent samples (n = 3). (B) A heatmap showing the expression of EMT-related genes and pluripotency genes in each up-regulated DEGs (n = 3). (C, D) EMT-related genes and pluripotency genes were described in (B) was quantified by qPCR. (E, F) The protein expression of SOX2 and EMT-related genes was verified by Western blot analysis. (G)Representative immunofluorescence images show fluorescence localization and intensity of E-cadherin, Vimentin and SOX2 in LUAD cells pre-treated with apoEVs or PBS. (H) Venn diagram representing the numbers of unique and overlapping up-regulated genes between two groups described in (A). (I) KEGG analysis with 390 selected genes that were significantly up-regulated in A549 pre-treated with A549-apoEVsDDP and A549-apoEVsSTS. (J, K) Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) shows that both A549-apoEVs mediate multiple hallmark pathways. (L, M) Western blot showing activation of enhanced phosphorylation of p65 and IκBα in tumor-apoEVs treated LUAD cells. LUAD cell lines treated with PBS was used as control group. Western blotting and IF were repeated at least three times and representative data are shown. All data are represented as mean ± SEM of three independent experiments and p values are based on a two-tailed Student's t-test. *p < 0.05; ns., not significant.

Western blotting analysis showed that tumor-apoEV-treated cells exhibited increased expression of SOX2, N-cadherin, Vimentin and SNAIL and decreased expression of E-cadherin; however, there was no significant difference in the protein expression levels between the normal-apoEV group and the control group (Fig. 4E–F). To further characterize the EMT phenotype in apoEV-treated LUAD cells, we performed immunofluorescence analysis of N-cadherin, Vimentin and SOX2 in the coculture system and examined the cellular localization and intensity of each protein marker (Fig. 4G). Consistent with the transcriptome analysis results, the expression of protein markers was strongly induced in tumor-apoEVs-treated cells compared with normal-apoEV-treated cells. These findings suggest that tumor-derived apoEVs play a crucial role in promoting the EMT phenotype and SOX2 transcription in LUAD cells.

3.5. LUAD cell-derived apoEVs induce stemness in LUAD cells via NF-κB signaling

Based on the observation described above, we proceeded to elucidate potential signaling pathway activation during EMT and SOX2 transcription. Transcriptome analysis indicated significant changes in several molecular functions, including the classical EMT-promoting GO term pathways “NF-κB signaling pathway” and “TNF signaling pathway” (Fig. 4H–I, Fig. S3). Consistent with this finding, GSEA also revealed significant enrichment of gene sets for “TNF-α signaling via NF-κB”, which was one of the most highly enriched pathways in LUAD cells that were treated with both types of tumor-apoEVs (Fig. 4J–K). Previous studies have demonstrated that the degradation of p65 can impede the expression of SOX2, thereby inhibiting the stemness of tumor cells [32]. In addition, the NF-κB pathway serves as an essential link for regulating inflammation, self-renewal, or maintenance and metastasis of CSCs [6]. Furthermore, immunoblotting analysis confirmed the enhanced phosphorylation of p65 kinase and IκBα (Fig. 4L–M), both of which are kinases that are involved in the regulation of NF-κB. These findings were observed in LUAD cell lines that were treated with tumor-derived apoEVs but not in cells that were treated with normal apoEVs. Then, the lung adenocarcinoma cells were treated with 20 nM QNZ (EVP4593) (Selleck, Houston, TX, USA) for 24 h to inhibit NF-κB signaling, and DMSO solution was used as a negative control. Notably, QNZ inhibited the effects of tumor-apoEVs on promoting migration, invasion, proliferation, and spheroid formation in lung adenocarcinoma (Figs. S4A–F). These results support that tumor-apoEVs promote lung adenocarcinoma metastasis and stemness by activating the NF-κB signaling pathway. Further, we investigated whether inhibiting NF-κB activation in lung adenocarcinoma could inhibit tumor-apoEVs-mediated SOX2 upregulation (Fig. S4G). Western blot results suggested that SOX2 up-regulation mediated by tumor-apoEVs could be reversed by NF-κB activation inhibitor. Taken together, these data confirmed that NF-κB/SOX2 pathway activation was dependent on tumor-apoEVs.

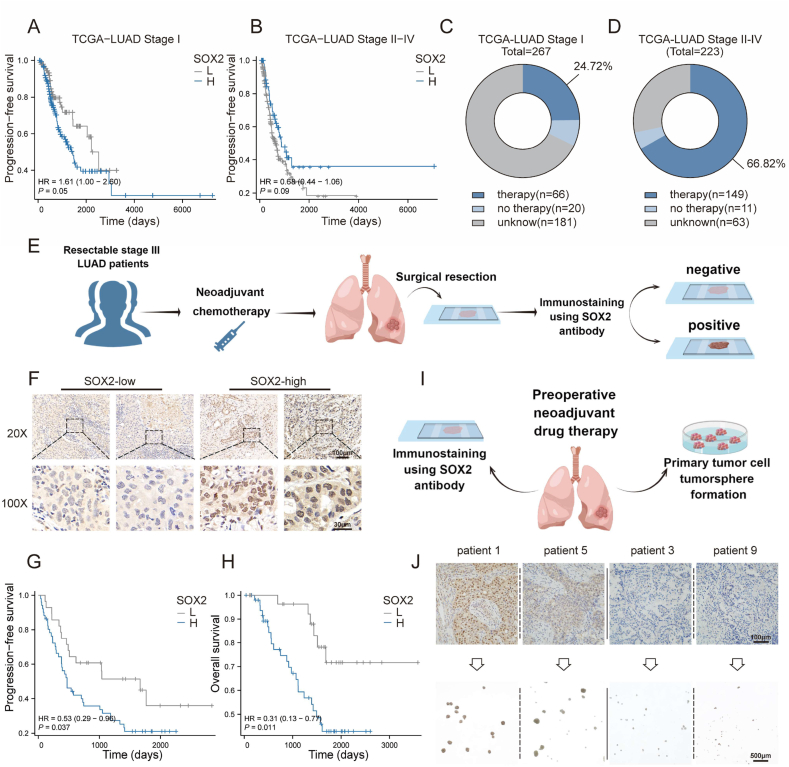

3.6. SOX2 is associated with the recurrence and stemness of residual LUAD tumors after classical treatment

The above studies found that tumor-derived apoEVs could mediate the upregulation of tumor stemness factor SOX2 in lung adenocarcinoma. The observations were further confirmed by analyzing the relationship between SOX2 expression and progression-free survival in the TCGA-LUAD cohort, it was determined that the expression level of SOX2 in stage I patients serves as a reliable indicator for predicting tumor recurrence (Fig. 5A); this result is consistent with the findings of a previous study [7]. However, elevated expression of SOX2 in stage II-IV patients does not predict recurrence and, in fact, follows an opposite trend in these patients (Fig. 5B). Consequently, we conducted an investigation of the reasons underlying this phenomenon, and we conducted statistical analyses on patients who were administered different treatment modalities (patients following radiotherapy, chemotherapy, and targeted therapy, collectively referred to as the therapy group). (Fig. 5C–D). The findings indicate that most patients with stage II-IV disease were administered postoperative adjuvant therapy, and these patients represented a significantly higher proportion compared to patients with stage I disease (66.82% vs. 24.72%). With the adherence to current clinical guidelines and the promotion of standardized treatment, the difference in the proportion of patients who received adjuvant and neoadjuvant therapy may be greater between the two populations. Furthermore, the expression level of SOX2 might have been altered by the administered treatment and apoEVs produced during treatment, thereby rendering the prediction of tumor recurrence based on the SOX2 expression level in untreated samples unreliable.

Fig. 5.

High SOX2 expression is associated with poor prognosis and CSCs in LUAD patients following conventional treatment. (A)Kaplan-Meier survival analysis of PFS of stage I patients' high level (n = 164) versus low level (n = 97) mRNA expression of SOX2 in TCGA-LUAD cohort. Data were analyzed using the log-rank test. Patients who had not progressed at the time of analysis were censored. (B) Kaplan-Meier survival analysis of PFS of stage II-IV patients' high level (n = 56) versus low level (n = 154) mRNA expression of SOX2 in TCGA-LUAD cohort. Data were analyzed using the log-rank test. Patients who had not progressed at the time of analysis were censored. (C, D) Distribution of patients receiving treatment or not from the TCGA-LUAD cohort described in (A) and (B) (Undergoing radiotherapy, chemotherapy, or targeted therapy, collectively referred to as the therapy group). (E) Schematic representation of the analysis of patient samples for SOX2 expression in LUAD. SOX2 immunostaining was performed on tissue specimens (surgical resection samples) from 79 LUAD patients with neoadjuvant chemotherapy containing platinum drugs. The IHC samples were scored by independent pathologists as either SOX2-high (The IHC score≥4) or SOX2-low (The IHC score≤3). (F) Representative microscopic images of SOX2-high and SOX2-low cases in LUAD tissue samples described in (D). Scale bars, 100 μm and 20 μm. (G, H) Kaplan–Meier analysis of the probability of OS and PFS in 79 LUAD patients according to SOX2-high expression (n = 50) or SOX2-low expression (n = 29). Data were analyzed using the log-rank test. Patients whose survival time or disease progression could not be accurately recorded at the time of analysis were censored. (I) Schematic protocol for assessing tumorsphere formation ability with regard to SOX2 expression of the resected tumor taken from patients after neoadjuvant target or chemotherapy. (J) The expression of SOX2 was evaluated in LUAD specimens by immunohistochemistry (n = 9). Their corresponding isolated cells were plated in stem cell medium. Scale bars represent 100 μm in the upper panels and 500 μm in the lower panels.

To comprehensively assess the potential prognostic value of SOX2 expression in posttreatment tumor samples, residual surgical tumor samples were obtained from 79 patients who were diagnosed with resectable stage III LUAD. These patients had undergone neoadjuvant chemotherapy followed by surgical resection (Fig. 5E). Subsequently, immunohistochemical staining was conducted on these tumor samples (Fig. 5F). In our study, the expression of SOX2 in the resected residual tumor samples was significantly correlated with both poor progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS), as shown in Fig. 5G–H (p < 0.05). Additionally, to evaluate the relationship between SOX2 expression and tumorsphere formation ability, which serves as an indicator of cancer stemness and self-renewal ability, a total of 9 fresh tumor samples were collected from patients who were administered neoadjuvant chemotherapy or targeted therapy. Subsequently, primary LUAD cells were collected from patients who received neoadjuvant therapy, and the cells were cultured in stem cell permissive medium (Fig. 5I). The inability to propagate tumor cells was observed in samples (3/3) with low SOX2 expression, whereas tumor cells from samples (4/6) with high SOX2 expression could be propagated for at least 3 passages (Fig. 5J). These findings indicated a positive correlation between SOX2 expression and unfavorable prognosis in patients with LUAD after conventional treatment and that SOX2 is upregulated in LUAD stem cells.

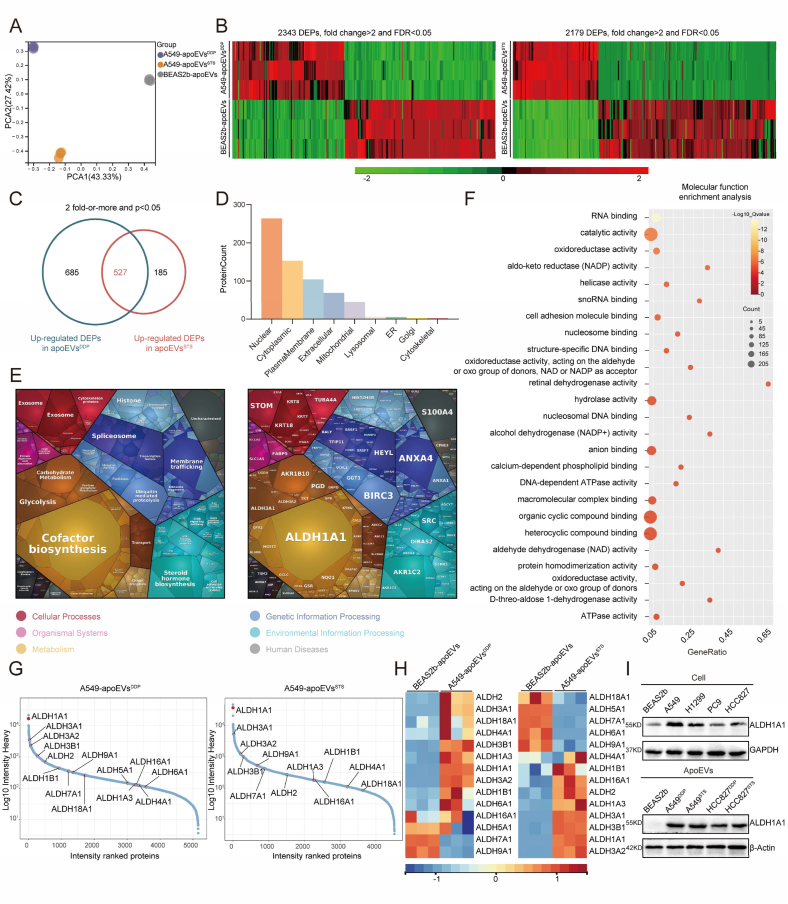

3.7. Quantitative proteomics shows that ALDH1A1 is enriched in tumor-derived apoEVs and responsible for ALDH enzyme activity in LUAD

To determine the specific proteins that mediate the functions of tumor-derived apoEVs, we conducted diaPASEF quantitative proteomics analysis on the proteins contained in A549-apoEVsDDP, A549-apoEVsSTS and BEAS2b-apoEVs. Principal component analysis (PCA) mapping revealed a distinct separation among the different types of apoEVs, indicating variations in their origins (Fig. 6A). Subsequently, a comparative analysis was conducted among A549-apoEVsDDP, A549-apoEVsSTS and BEAS2b-apoEVs to identify differentially expressed proteins (DEPs) among these types of vesicles (Fig. 6B). To further elucidate the biological roles of the protein contents of tumor-apoEVs, we conducted a comprehensive screening of 527 proteins that were upregulated in A549-apoEVs that were induced by both DDP and STS (Fig. 6C). Subsequently, we analyzed the subcellular localization of the co-upregulated DEPs, and these proteins were predominantly observed in the nucleus, cytoplasm, plasma membrane, extracellular space, and mitochondria (Fig. 6D). We then constructed proteomaps to cluster the DEPs according to their Kyoto Encyclopedia Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway annotations, and we found that these upregulated DEPs were associated with “Cofactor biosynthesis”, “Glycolysis” and “Carbohydrate Metabolism” within the “Metabolism” domain; “Steroid hormone biosynthesis” within the “Environmental Information Processing” domain; “Membrane trafficking” and “Spliceosome” within the “Genetic Information Processing” domain; and “Exosome” and “Cytoskeleton Proteins” within the “Cellular Processes” domain (Fig. 6E). Interestingly, transcriptome analysis of A549 cell line treated with tumor-derived apoEVs indicated significant changes in several metabolic processes, including “Cellular aldehyde metabolic process”, “Fatty acid derivative metabolic process”, “rRNA metabolic process”, “Pyrimidine metabolism”, “Nitrogen metabolism”, “Parathyroid hormone synthesis”, “Secretion, pantothenate and CoA biosynthesis” and “Nicotinate and nicotinamide metabolism” (Fig. S3), quantitative proteomics shows that apoEVs contain complex metabolic enzyme components, which may be the reason for the activation of many metabolic pathways in recipient cells. Additionally, a PPI analysis was conducted to illustrate a comprehensive protein network with functional associations (Fig. S5). Subsequently, GO molecular function enrichment analysis revealed that tumor-apoEVs contained increased levels of proteins with the metabolic function of dehydrogenases (Fig. 6F), including ‘catalytic activity’, ‘aldo-keto reductase (NADP) activity’, ‘retinal dehydrogenase activity’, ‘alcohol dehydrogenase (NADP+) activity’ and ‘D-threo-aldose 1-dehydrogenase activity’. High levels of acetaldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH) were found among the upregulated proteins in the tumor-apoEVs. Ranking of protein levels revealed the relative expression of ALDH family members among all the protein contents of apoEVs, and ALDH1A1 was the protein with the highest abundance in A549-apoEVs (Fig. 6G), moreover, its expression was upregulated compared with that in BEAS2b-apoEVs (Fig. 6H). We observed the protein expression level of ALDH1A1 in a LUAD cell line. In addition, the upregulation of ALDH1A1 in tumor-apoEVs was confirmed through immunoblotting analysis (Fig. 6I). The overexpression of ALDH1A1 has been implicated in facilitating both tumor initiation and tumor progression [33,34]. However, the precise mechanism underlying its upregulation in tumor cells remains unknown. The accumulation of ALDH1A1 through the delivery of apoEVs may be a mechanism by which tumor metastasis and stemness are regulated. These results suggest that apoEVs-ALDH1A1 may be a functional protein that leads to tumor metastasis and stemness, and we conducted further investigation.

Fig. 6.

Quantitative proteomic analysis revealed that ALDH1A1 was a functional protein within apoEVs. (A) PCA plot of protein expression of apoEV-A549DDP, apoEV-A549STS and apoEV-BEAS2b. (B) Heatmaps depict the clustering of differentially expressed proteins (DEPs) between Beas2b and A549-apoEVs (n = 3). (C) The Venn diagram illustrates the number of proteins that were significantly up-regulated DEPs in both A549-apoEVsDDP and A549-apoEVsSTS compared with BEAS2b-apoEVs. (D) Subcellular localization of DEPs described in (C). (E) The Proteomaps demonstrate the KEGG functional categories of the up-regulated DEPs in both A549-apoEVsDDP and A549-apoEVsSTS. Each polygon depicted in the Proteomaps represents a distinct KEGG pathway, with its size indicating the protein's quantitative intensity determined through diaPASEF quantitative proteomic analysis. (F) ‘Molecular function’ enrichment analysis of the DEPs in (C). The top 25 enriched GO terms were presented as a bubble chart. The Y-axis of the graph represents Gene Ontology (GO) terms, while the X-axis represents the rich factor GeneRatio. The color of each bubble on the graph indicates the level of enrichment significance, while the size of the bubble corresponds to the number of DEPs. (G) The quantified proteins in A549-apoEVsDDP and A549-apoEVsSTS are ranked based on their heavy intensity. The ALDH protein family in apoEVs is highlighted in the scatter plots. (H) Heatmap showing the detected ALDH protein family expression in A549-apoEVs compared with BEAS2b-apoEVs (n = 3). (I) Western blot showing ALDH1A1 expression in the indicated LUAD cell lines and apoEVs, with GAPDH and β-actin as the loading standard.

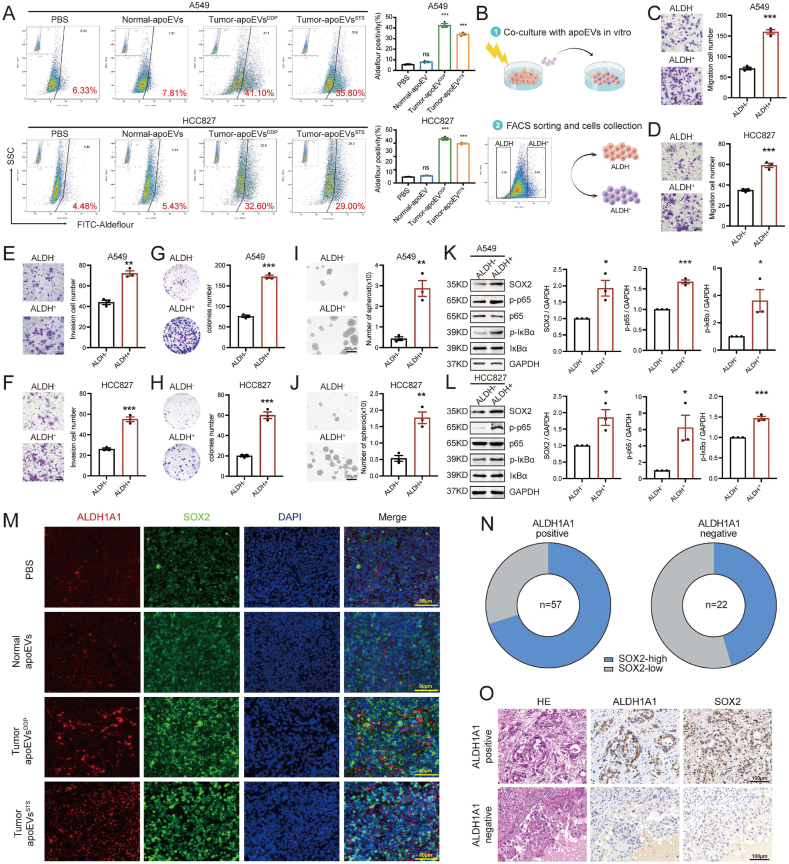

3.8. apoEVs-ALDH1A1 upregulate SOX2 transcription in LUAD cells through NF-κB signaling

It has been reported that overactivation of ALDH can lead to the accumulation of acidic products, which in turn activate the NF-κB signaling pathway [35]. Activation of the NF-κB pathway can regulate SOX2 transcription and EMT initiation to mediate cancer cell migration, stemness and chemotherapy resistance [36]. Therefore, we asked whether the increase in ALDH activity that is induced by tumor-apoEVs activates the NF-κB/SOX2 pathway. To this end, we first measured the activity of the ALDH enzyme in LUAD cells that were treated with apoEVs. Aldefluor analysis showed that ALDH enzyme activity was extremely increased in LUAD cells that were treated with tumor-apoEVs but not LUAD cells that were treated with PBS and normal-apoEVs (Fig. 7A). We then investigated whether tumor-apoEV-induced ALDH enzyme activation contributed to cell migration and stemness. We performed FACS sorting of LUAD cells that were treated with tumor-apoEVs to separate cell populations with different degrees of ALDH enzyme activity (Fig. 7B). We further investigated the migration and tumorigenicity capacities of the ALDH+ and ALDH- populations. The results showed that the ALDH + population had stronger mobility and self-renewal abilities than the ALDH- population (Fig. 7C–J). To confirm that NF-κB/SOX2 signaling activation was a consequence of apoEV-induced ALDH enzyme activation, Western blotting was performed, and the results indicated that the ALDH + population that was treated with tumor-apoEVs exhibited increased phosphorylation of p65 and IκBα (Fig. 7K–L). Furthermore, to verify this regulatory relationship in tissue samples, we subsequently performed immunofluorescence analysis of ALDH1A1 and SOX2 in sections of tumor tissues that were harvested from metastatic model mice, as described in Fig. 2. ALDH1A1 and SOX2 were strongly co-expressed in tumor tissues after treatment with tumor-apoEVs compared with tumor tissue after treatment with PBS or normal-apoEVs (Fig. 7M). To further investigate the relationship between ALDH1A1 and SOX2 in clinical samples during neoadjuvant chemotherapy, IHC analyses were performed, and the results showed a significant correlation between ALDH1A1 and SOX2 protein levels (Fig. 7N–O). The close association between ALDH1A1 and SOX2 was further demonstrated through the analysis of their transcription levels using external TCGA and GEO databases (Fig. S6). These findings provide evidence for a correlation between ALDH1A1 and SOX2 expression in both experimental and clinical samples.

Fig. 7.

apoEVs-ALDH1A1 is involved in activating NF-κB -SOX2 axis. (A)ALDH enzyme activity assay of LUAD cells pre-treated with PBS or apoEVs. Aldefluor-positive cells were quantified by flow cytometry. Each sample treated with the ALDH inhibitor DEAB was used as a negative control. (B)Schematic diagram illustrating the experimental design for subsequent cell function assays in vitro. (C–F) Migration and invasion assays of ALDH+ and ALDH- LUAD cell populations. ALDH+ and ALDH- cell populations were sorted from LUAD cells pre-treated with apoEVsDDP. Scale bars, 100 μm. (G, H) Colony formation assay of ALDH+ and ALDH- cell populations. (I, J) Tumorsphere formation assay of ALDH+ and ALDH- cell populations. Representative photographs of spheroids formed after incubation. The histogram indicates the number of spheres formed per 1000 cells. Scale bars, 200 μm. (K, L) The activation of the p-p65 and p- IκBα signaling and upregulated SOX2 expression were in ALDH + LUAD cell populations pre-treated with tumor-apoEVsDDP analyzed by Western blot. (M) Representative immunofluorescence images of ALDH1A1 (red), SOX2 (green), and DAPI nuclear counterstaining (blue) in tissue samples taken from the mouse lung metastases formation assay in Fig. 2. The presented data are a representative image of n = 5. Scale bars, 80 μm. (N, O) Representative microscopic images of H&E staining and IHC analyses of ALDH1A1 and SOX2 expression in human clinical LUAD tissue samples. The presented data are a representative image of n = 5. Scale bars, 100 μm. Western blotting and IF were repeated at least three times and representative data are shown. All data are represented as mean ± SEM of three independent experiments and p values are based on a two-tailed Student's t-test. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001; ns., not significant.

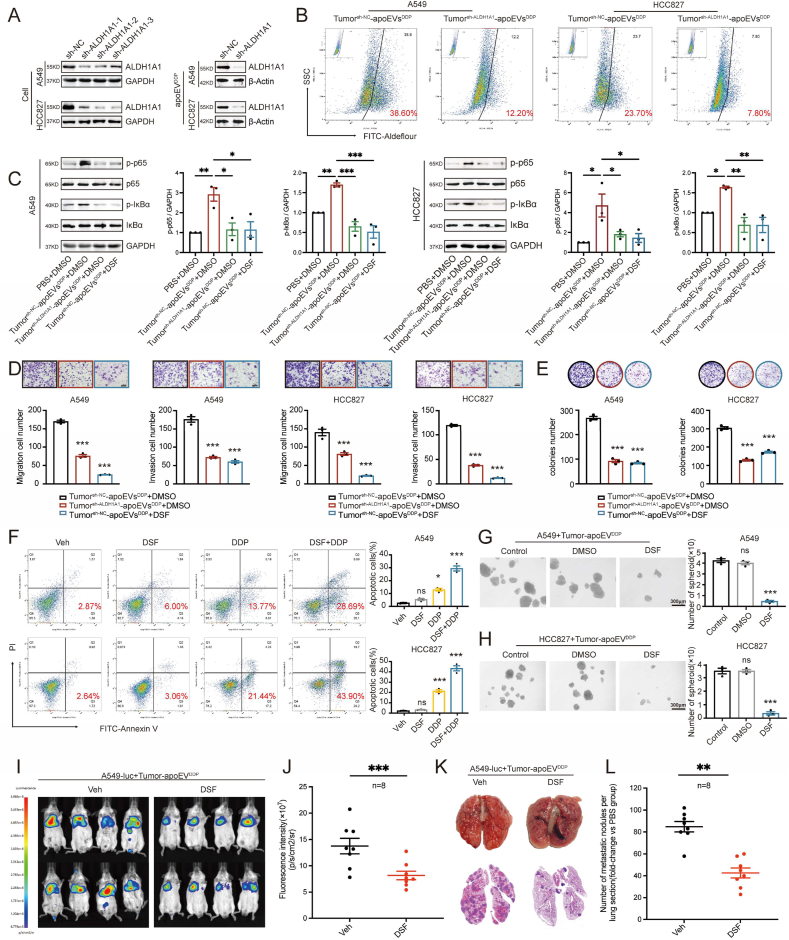

3.9. Targeting ALDH1A1 inhibits tumor metastasis and stemness, and increases chemosensitivity

To further determine the function of apoEVs-ALDH1A1, we established stable ALDH1A1-knockdown (sh-ALDH1A1-1, sh-ALDH1A1-2 and sh-ALDH1A1-3) and vehicle control cells (sh-NC) in the A549 and HCC827 LUAD cell lines. We induced tumor cells and isolated tumor-derived apoEVs. Then, Western blotting analysis confirmed that knockdown of ALDH1A1 reduced the protein levels of ALDH1A1 that were contained in tumorsh−ALDH1A1-apoEVs compared to those in tumorsh−NC-apoEVs (Fig. 8A). The Aldefluor assay confirmed that the ALDH enzyme activity was significantly reduced in LUAD cells that were treated with tumorsh−ALDH1A1-apoEVs compared to LUAD cells that were treated with tumorsh−NC-apoEVs (p < 0.05) (Fig. 8B). These results indicated that the enhanced ALDH enzyme activity depended on apoEVs-ALDH1A1. The undruggable nature of the transcription factor SOX2 has prevented the discovery of SOX2 inhibitors [37], Consequently, targeting ALDH1A1 could potentially serve as an alternative approach that is more tolerable and applicable to the treatment of LUAD or other tumor types that are characterized by elevated ALDH1A1 expression by inhibiting cancer stem cells and preventing recurrence and metastasis.

Fig. 8.

Targeting apoEVs-ALDH1A1 diminished the activity of apoEVs-ALDH1A1 in promoting migration, invasion, drug resistance, and stemness of LUAD. (A) Western blot analysis showing ALDH1A1 level in ALDH1A1 knockdown (sh-ALDH1A1) LUAD cells and apoEVs (apoEVs-ALDH1A1) derived from the knockdown LUAD cell. (B)ALDH enzyme activity assay of LUAD cells pre-treated with indicated tumor-apoEVs. Each sample treated with the ALDH inhibitor DEAB was used as a negative control. The presented data are a representative image of three independent experiments. (C)Western blot showing the activation of p-p65 and p- IκBα signaling in LUAD cells treated with apoEVsDDP derived from control LUAD cells (sh-NC) can be reversed by Disulfiram (DSF), while p-p65 and p-IκBα signaling in LUAD cells treated with apoEVsDDP derived from ALDH1A1 knockdown LUAD cells (sh-ALDH1A1) were not significantly up-regulated. Colony formation (E), migration and invasion (D) assay showing the effect of indicated apoEVs and DSF on tumor-apoEVs treated cell model. (F) Flow cytometry analysis of apoptotic cells exhibiting the synergistic response of DSF and cisplatin on tumor-apoEVs treated cell model. The percentages of apoptotic cells were plotted. (G, H) Estimation of the suppressing effect of DSF on tumor-apoEVs treated cell model using the tumorsphere formation assay. The tumor-apoEVs treated cell model was treated with the DSF (0.15 μM) for 5 days. Scale bars, 300 μm. (I) Bioluminescence imaging of animals treated with tumor-derived apoEVs to estimate the suppressing effect of DSF on the lung metastasis formation model. (J) Scatter plot depicting the ROI quantification of A549-luc whole-body metastatic tumor radiance from mice described in (I). Animals treated with DSF orally (n = 8); Animals treated with an equal volume of the vehicle orally (n = 8). (K) Representative images of the lung and H&E staining of tissue sections taken from the lung metastasis formation model. (L) The number of metastatic nodules in lung sections described in (K). Data represent means ± SEM of three independent experiments. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001; ns., not significant.

Disulfiram (DSF) is an irreversible ALDH inhibitor with reliable safety, and it is extensively used in clinical settings for the treatment of chronic alcoholism [38], Multiple lines of evidence have suggested the potential utility of DSF as an anticancer agent, operating through diverse mechanisms [38,39]. However, whether DSF can be used to control tumor stem cells and prevent recurrence and metastasis in LUAD remains to be further studied. Our research showed that the apoEVs-ALDH1A1-induced phosphorylation of p65 and IκBα was decreased by knocking down the protein levels of ALDH1A1 in apoEVs or by treating cells with DSF (Fig. 8C). Functionally, cell ability of migration, invasion and self-renewal were also decreased, which was consistent with NF-κB signaling results (Fig. 8D–E). In addition, we tested whether the combination of DSF and cisplatin had a synergistic effect on LUAD cells. Our findings indicate that while treatment with DSF alone had a limited impact, the combination treatment notably improved the responsiveness of LUAD cells to cisplatin (Fig. 8F). In addition, DSF reduced the tumorsphere formation ability of treated LUAD cells that were treated with tumor-apoEVs (Fig. 8G–H). Finally, DSF also exerted a significant effect on diminishing metastasis in NOD/SCID mice that were treated with tumor-apoEVs (Fig. 8I). These data verify that the luciferase signal and metastatic nodule number were reduced in mice that were orally administered DSF compared to mice that were orally administered the same volume of vehicle (Fig. 8J-L). Taken together, these results revealed a promising direction for developing a novel and reliable treatment strategy combined with routine treatment.

4. Discussion and conclusion

Apoptotic cells produce apoptotic bodies for a considerable period of time, but the identification of smaller apoptotic extracellular vesicles (apoEVs) has only recently occurred [40], and further investigation is needed to understand their mechanisms and functions. Recent research has demonstrated the significant roles of apoEVs derived from mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) in immune regulation, disease treatment, and drug delivery [[41], [42], [43], [44], [45]]. In the field of cancer research, it is noteworthy that tumor cells have the ability to secrete apoEVs. In the context of solid tumor treatment, conventional treatments induce tumor cell apoptosis, which consequently leads to the inevitable formation of apoptotic vesicles, especially after radiotherapy and chemotherapy. Apoptotic tumor cells release a substantial quantity of apoEVs in a relatively short time, and these apoEVs serve as a means of communication with neighboring residual tumor cells. ApoEVs that are derived from glioblastoma have been found to promote therapeutic resistance and induce an aggressive migratory phenotype in recipient cells through changes in RNA splicing, as reported by previous studies [46]. Additionally, reports have indicated that hepatectomy-induced apoEVs can stimulate a subset of neutrophils with regenerative properties to secrete growth factors that facilitate tissue regeneration without eliciting an inflammatory response [47]. In addition, apoEVs derived from brain metastatic cancer cells have potential as carriers for brain-targeted delivery, with remarkable delivery efficiency [48]. However, the impact of tumor-derived apoEVs on the stemness of cancer cells remains unexplored. Here, we discovered that tumor-derived apoEVs enhance cell migration and confer resistance to chemotherapy by inducing stemness and promoting EMT in LUAD cells.

ALDH1A1 and SOX2 are essential regulators that have been implicated in the preservation of cancer stem cells, and they exert synergistic effects on modulating cancer-related biological processes, such as tumor advancement, maintenance of cancer stem cell characteristics, and induction of chemotherapy resistance [34,34,49]. However, limited investigations have been conducted to explore the regulatory relationship between these two factors, necessitating further research in this area. In this study, we conducted in vivo and in vitro experiments to demonstrate that tumor-derived apoEVs enhance the activity of the ALDH enzyme, thereby activating the NF-κB-SOX2 axis in LUAD cells through the delivery of the ALDH1A1 protein to recipient tumor cells. These findings contribute to a novel understanding of the transcriptional regulation of SOX2 after tumor treatment. In addition, despite the extensive documentation of the involvement of ALDH family proteins in disease progression and therapeutic resistance in cancers [[50], [51], [52], [53]], limited research has been conducted on the extracellular functions of ALDH. To our knowledge, there is a dearth of reports on the potential secretion of ALDH into EVs in the context of cancer. Furthermore, academic research has established that the human genome includes a total of 19 functional ALDH genes, and ALDH1A1 exhibits the strongest enzyme activity. Notably, ALDH1A1 has been identified as a key activator of the retinoic acid (RA) signaling pathway, subsequently triggering the activation of tumor stem cells across various tumor types [54,55]. Consequently, understanding the underlying mechanism that is responsible for the upregulation of ALDH1A1 is very important in the field of tumor prevention and treatment. In this study, we have identified a novel mechanism by which ALDH1A1 is upregulated in tumor cells, and we clearly demonstrated that ALDH1A1 is encapsulated within apoEVs; it has been established that EVs play a crucial role in maintaining the stability of their cargo and facilitating its delivery to distant sites [56]. Under the protection of the apoEV lipid bilayer, ALDH1A1 is transferred to surrounding cells, accumulates in recipient cells, and subsequently increases ALDH enzyme activity. Furthermore, based on an analysis of clinical samples and public databases, our study reveals a significant association between the presence of ALDH1A1 in residual tumor cells and the upregulation of SOX2 as well as tumor recurrence and metastasis in patients with LUAD who were treated with neoadjuvant chemotherapy combined with surgical resection. In addition to ALDH1A1, other ALDH proteins, such as ALDH2, ALDH3A1 and ALDH3A2, are also prominently enriched in apoEVs. Further investigation is warranted to elucidate the potential involvement of these differentially expressed ALDH proteins in tumorigenesis.

Furthermore, EMT and cancer stemness have been implicated in the development of treatment resistance and tumor recurrence [57]; however, the intricate association between these two phenotypes requires additional elucidation. On the one hand, recent literature provides evidence of the need to activate the EMT program to acquire stemness [5,58,59]. On the other hand, although cells that exist in either epithelial or mesenchymal cell states can exhibit stemness characteristics, the emerging concept “epithelial-mesenchymal plasticity (EMP)” indicates that cancer cells exist in a hybrid epithelial/mesenchymal state (E/M state), wherein hybrid cells possess greater stemness capabilities than their purely epithelial or mesenchymal counterparts [[60], [61], [62]]; therefore, determining the factor that induces E/M state transformation could provide a new direction for tumor treatment. In our study, we found that tumor-derived apoEVs can induce the expression of EMT-related genes and pluripotency genes, including VIM, CDH2, ZEB2, TWIST1 and SOX2. This transcriptional regulation changes dynamically with different phases of cancer occurrence, development and treatment. Notably, in practical clinical work, the administration of radiotherapy and chemotherapy to patients with lung cancer leads to the periodic production of apoEVs, which intermittently stimulate cancer cells to transition into the epithelial-to-mesenchymal (E/M) state and increase the likelihood that residual tumor cells will transform into cancer stem cells, potentially contributing to the recurrence and metastasis of cancer after treatment. Consequently, apoEVs have emerged as a promising therapeutic target in this context.

Taken together, our findings suggest that apoEVs that are derived from apoptotic tumor cells promote the metastasis and stemness of LUAD, and these characteristics are intricately associated with recurrence and resistance to therapy in a clinical context. Notably, this apoptotic vesicle-dependent intercellular communication represents a general response to cells undergoing necrosis or apoptosis. This newly activated apoEV signaling provides an adaptive mechanism by which recipient tumor cells resist proapoptotic treatments and offers a new opportunity for the treatment of LUAD, as it renders cells dependent on ALDH1A1/NF-κB/SOX2 signaling and the activation of a stem cell-like population. Thus, this study provids a new rationale for combination therapy that includes cytotoxic compounds and ALDH inhibitors and provides new possibilities for the prevention of tumor recurrence.

Data availability statement

All data obtained and/or utilized in the research are accessible to readers. The RNA sequencing and NGS sequencing produced in this investigation are publicly accessible in the Gene Expression Omnibus under the accession number GSE241595. Interested readers may obtain the data generated in our study from the corresponding authors.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the Ethics and Research Committees of the Sun Yat-sen University Cancer Center (protocol number SL-B2023-244-01). All animal experimentation conducted at the Sun Yat-Sen University Cancer Center received prior approval from the Experimental Animal Ethics Committee (protocol number L102012022110H).

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Xiaotian He: Writing – original draft, Validation, Software, Project administration, Investigation, Data curation, Conceptualization. Yiyang Ma: Writing – original draft, Software, Project administration, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation. Yingsheng Wen: Writing – original draft, Validation, Project administration, Methodology, Investigation. Rusi Zhang: Writing – original draft, Software, Project administration, Investigation. Dechang Zhao: Resources, Project administration, Investigation. Gongming Wang: Visualization, Validation, Project administration, Data curation. Weidong Wang: Visualization, Supervision, Software, Project administration, Conceptualization. Zirui Huang: Software, Investigation, Formal analysis. Guangran Guo: Project administration, Investigation, Formal analysis. Xuewen Zhang: Project administration, Investigation. Huayue Lin: Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Resources, Funding acquisition, Formal analysis, Conceptualization. Lanjun Zhang: Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Resources, Funding acquisition, Conceptualization.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by grants from the Director Foundation of Sun Yat-sen university Cancer Center (PT12020401), the National Key Research and Development Program of China (No. 2021YFC2500905), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 82073121), Guangdong Basic and Applied Basic Research Foundation (No. 2020A1515010041). Graphical abstract is created using Figdraw (www.figdraw.com).

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of KeAi Communications Co., Ltd.

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bioactmat.2024.02.026.

Contributor Information

Xiaotian He, Email: hext@sysucc.org.cn.

Yiyang Ma, Email: mayy1@sysucc.org.cn.

Yingsheng Wen, Email: wenyingsh@sysucc.org.cn.

Rusi Zhang, Email: zhangrs@sysucc.org.cn.

Dechang Zhao, Email: zhaodc@sysucc.org.cn.

Gongming Wang, Email: wanggm@sysucc.org.cn.

Weidong Wang, Email: wangweid@sysucc.org.cn.

Zirui Huang, Email: huangzr@sysucc.org.cn.

Guangran Guo, Email: guogr@sysucc.org.cn.

Xuewen Zhang, Email: zhangxuew@sysucc.org.cn.

Huayue Lin, Email: linhy29@mail.sysu.edu.cn.

Lanjun Zhang, Email: zhanglj@sysucc.org.cn.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article.

References

- 1.Sung H., Ferlay J., Siegel R.L., Laversanne M., Soerjomataram I., Jemal A., Bray F. Global cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. Ca - Cancer J. Clin. 2021;71:209–249. doi: 10.3322/caac.21660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Travis W.D., Brambilla E., Noguchi M., Nicholson A.G., Geisinger K.R., Yatabe Y., Beer D.G., Powell C.A., Riely G.J., Van Schil P.E., Garg K., Austin J.H.M., Asamura H., Rusch V.W., Hirsch F.R., Scagliotti G., Mitsudomi T., Huber R.M., Ishikawa Y., Jett J., Sanchez-Cespedes M., Sculier J.-P., Takahashi T., Tsuboi M., Vansteenkiste J., Wistuba I., Yang P.-C., Aberle D., Brambilla C., Flieder D., Franklin W., Gazdar A., Gould M., Hasleton P., Henderson D., Johnson B., Johnson D., Kerr K., Kuriyama K., Lee J.S., Miller V.A., Petersen I., Roggli V., Rosell R., Saijo N., Thunnissen E., Tsao M., Yankelewitz D. International association for the study of lung cancer/american thoracic society/european respiratory society international multidisciplinary classification of lung adenocarcinoma. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2011;6:244–285. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e318206a221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Reya T., Morrison S.J., Clarke M.F., Weissman I.L. Stem cells, cancer, and cancer stem cells. Nature. 2001;414:105–111. doi: 10.1038/35102167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Visvader J.E., Lindeman G.J. Cancer stem cells: current status and evolving complexities. Cell Stem Cell. 2012;10:717–728. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2012.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Laplane L., Solary E. Towards a classification of stem cells. Elife. 2019;8 doi: 10.7554/eLife.46563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yang L., Shi P., Zhao G., Xu J., Peng W., Zhang J., Zhang G., Wang X., Dong Z., Chen F., Cui H. Targeting cancer stem cell pathways for cancer therapy. Signal Transduct. Targeted Ther. 2020;5:8. doi: 10.1038/s41392-020-0110-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sholl L.M., Barletta J.A., Yeap B.Y., Chirieac L.R., Hornick J.L. Sox2 protein expression is an independent poor prognostic indicator in stage I lung adenocarcinoma. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2010;34:1193–1198. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e3181e5e024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schaal C.M., Bora-Singhal N., Kumar D.M., Chellappan S.P. Regulation of Sox2 and stemness by nicotine and electronic-cigarettes in non-small cell lung cancer. Mol. Cancer. 2018;17:149. doi: 10.1186/s12943-018-0901-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kuo M.-H., Lee A.-C., Hsiao S.-H., Lin S.-E., Chiu Y.-F., Yang L.-H., Yu C.-C., Chiou S.-H., Huang H.-N., Ko J.-C., Chou Y.-T. Cross-talk between SOX2 and TGFβ signaling regulates EGFR-TKI tolerance and lung cancer dissemination. Cancer Res. 2020;80:4426–4438. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-19-3228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mao L., Chen J., Lu X., Yang C., Ding Y., Wang M., Zhang Y., Tian Y., Li X., Fu Y., Yang Y., Gu Y., Gao F., Huang J., Liao L. Proteomic analysis of lung cancer cells reveals a critical role of BCAT1 in cancer cell metastasis. Theranostics. 2021;11:9705–9720. doi: 10.7150/thno.61731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mollaoglu G., Jones A., Wait S.J., Mukhopadhyay A., Jeong S., Arya R., Camolotto S.A., Mosbruger T.L., Stubben C.J., Conley C.J., Bhutkar A., Vahrenkamp J.M., Berrett K.C., Cessna M.H., Lane T.E., Witt B.L., Salama M.E., Gertz J., Jones K.B., Snyder E.L., Oliver T.G. The lineage-defining transcription factors SOX2 and NKX2-1 determine lung cancer cell fate and shape the tumor immune microenvironment. Immunity. 2018;49:764–779.e9. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2018.09.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gregory C.D., Rimmer M.P. Extracellular vesicles arising from apoptosis: forms, functions, and applications. J. Pathol. 2023 doi: 10.1002/path.6138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Atkin-Smith G.K., Poon I.K.H. Disassembly of the dying: mechanisms and functions. Trends Cell Biol. 2017;27:151–162. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2016.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Atkin-Smith G.K., Tixeira R., Paone S., Mathivanan S., Collins C., Liem M., Goodall K.J., Ravichandran K.S., Hulett M.D., Poon I.K.H. A novel mechanism of generating extracellular vesicles during apoptosis via a beads-on-a-string membrane structure. Nat. Commun. 2015;6:7439. doi: 10.1038/ncomms8439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang X., Tang J., Kou X., Huang W., Zhu Y., Jiang Y., Yang K., Li C., Hao M., Qu Y., Ma L., Chen C., Shi S., Zhou Y. Proteomic analysis of MSC‐derived apoptotic vesicles identifies Fas inheritance to ameliorate haemophilia a via activating platelet functions. J. Extracell. Vesicles. 2022;11 doi: 10.1002/jev2.12240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Couch Y., Buzàs E.I., Di Vizio D., Gho Y.S., Harrison P., Hill A.F., Lötvall J., Raposo G., Stahl P.D., Théry C., Witwer K.W., Carter D.R.F. A brief history of nearly EV-erything - the rise and rise of extracellular vesicles. J. Extracell. Vesicles. 2021;10 doi: 10.1002/jev2.12144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]