Abstract

Staphylococcus aureus is a major cause of prosthetic vascular graft or endograft infections (VGEIs) and the optimal choice of antibiotics is unclear. We investigated various antibiotic choices as either monotherapy or combination therapy with rifampicin against MRSA in vitro and in vivo.

Fosfomycin, daptomycin and vancomycin alone or in combination with rifampicin was used against MRSA USA300 FPR3757. Each antibiotic was tested for synergism or antagonism with rifampicin in vitro, and all antibiotic regimens were tested against actively growing bacteria in media and non-growing bacteria in buffer, both as planktonic cells and in biofilms. A rat model of VGEI was used to quantify the therapeutic efficacy of antibiotics in vivo by measuring bacterial load on grafts and in spleen, liver and kidneys.

In vitro, rifampicin combinations did not reveal any synergism or antagonism in relation to growth inhibition. However, quantification of bactericidal activity revealed a strong antagonistic effect, both on biofilms and planktonic cells. This effect was only observed when treating active bacteria, as all antibiotics had little or no effect on inactive cells. Only daptomycin showed some biocidal activity against inactive cells. In vivo evaluation of therapy against VGEI contrasted the in vitro results. Rifampicin significantly increased the efficacy of both daptomycin and vancomycin. The combination of daptomycin and rifampicin was by far the most effective, curing 8 of 13 infected animals.

Our study demonstrates that daptomycin in combination with rifampicin shows promising potential against VGEI caused by MRSA. Furthermore, we show how in vitro evaluation of antibiotic combinations in laboratory media does not predict their therapeutic effect against VGEI in vivo, presumably due to a difference in the metabolic state of the bacteria.

Keywords: Vascular graft or endograft infections, VGEI, Prosthesis, MRSA, Staphylococcus aureus, Infections, Biofilm, Persister cells, Rat model, Rifampicin

Highlights

-

•

Vascular graft/endograft infections (VGEI) are characterized by biofilms with inactive, antibiotic-tolerant bacteria.

-

•

Vancomycin, daptomycin, and fosfomycin were effective against active but not inactive MRSA in vitro.

-

•

In vitro, rifampicin antagonized the biocidal activity of these drugs against active but not inactive MRSA.

-

•

Rifampicin combination therapy was the most effective treatment against VGEI in rats, indicating inactive bacteria dominate.

-

•

Daptomycin and rifampicin combinations was the most efficacious treatment.

1. Introduction

Prosthetic vascular graft or endograft infections (VGEI) are a devastating complication to an otherwise life-saving surgical procedure [1,2]. Vascular grafts are used in the treatment of aortic aneurisms and aortic dissections among others and the most common materials used are Dacron and polytetrafluorethylene (PTFE) [3]. The infection rate is up to 6%, though this depends on the type of implant material and the anatomical location [4]. VGEIs are typically divided into early or late infections according to the timing of their onset, with Staphylococcus aureus being a major cause of early VGEI [5]. S. aureus is a common cause of implant-associated infections due to an array of virulence factors and the ability to form biofilms [6]. Further, S. aureus infections are characterised by the presence of persister cells, a sub-population of transiently antibiotic tolerant cells with low or no growth and metabolism [7,8]. Given that both the presence of biofilms and persister cells leads to decreased efficacy of antibiotics and the sinister prognosis of VGEI, it is imperative to establish which antibiotics are most efficacious in treating early VGEIs – especially infections caused by MRSA, in which the selection of antibiotics is limited [3]. Current knowledge on successful treatment of implant associated infections is largely based on studies and expert opinion on the treatment of orthopedic implant associated infections. In this field, several diagnostic criteria and algorithms exist, some of which are based on randomized control trials [9]. In contrast to this, there is no consensus on best clinical practice of antibiotic or surgical treatment regarding VGEI. The latest guidelines from the European Society of Vascular Surgery on vascular graft infection from 2020 does not contain concrete advice on duration of antimicrobial therapy, choice of antibiotics or under which circumstances combination therapy should be utilized [3]. Combination therapy involving rifampicin has for decades been regarded as essential against acute prosthetic joint infections caused by staphylococci [10,11]. This is in part due to rifampicin’s anti-biofilm properties against staphylococci, which has been extensively demonstrated in vitro and in preclinical in vivo models of implant-associated infections [12]. Further, previous in vitro studies have demonstrated that rifampicin is able to kill persister cells formed by e.g., Mycobacterium tuberculosis or Escherichia coli [13,14]. Whether it is beneficial to combine other antibiotics with rifampicin to specifically target S. aureus persister cells is currently unknown. Interestingly, retrospective studies on VGEI found a significantly lower risk of treatment failure if rifampicin was administered with an OR of 0.3 (95% CI: 0.09–0.87, 95% CI, p = 0.04) and OR 0.32 (95% CI: 0.10–0.96; p = 0.04), yet such studies inherently risk bias in the form of confounding by indication, making it impossible to ascertain if the effect is caused by rifampicin enhanced killing of persister cells [15,16].

We have previously shown a dramatic increase in therapeutic effect when combining vancomycin with rifampicin to treat early MRSA VGEI in a novel rat model [17]. This finding led us to hypothesize that combination of other antibiotics with rifampicin would also improve the antimicrobial efficacy against MRSA infections. The aim of this study was therefore to determine if combination of daptomycin and fosfomycin with rifampicin leads to an improved antimicrobial effect in vitro and in vivo against active bacteria and against inactive/non-growing cells that display the same antibiotic tolerance as persister cells.

2. Methods and materials

2.1. Ethics

The animal experiments in this study were approved by the Danish Animal Experiments Inspectorate under permissions 2017-15-0201-01153 and 2022-15-0201-01132 and were carried out in accordance with the guidelines of Aarhus University and under the supervision of faculty veterinarians. All animal experiments followed the Animal Research: Reporting of In Vivo Experiments (ARRIVE) guidelines (Table S2).

2.2. Bacterial strain, growth media and antibiotics

The clinical MRSA isolate USA300 FPR3757 (ATCC® BAA-1556) was used for all experiments [18]. Tryptic Soy Broth (TSB, T8907, Sigma Aldrich) was used as bacterial growth media unless otherwise stated. The strain was cultivated on Tryptic Soy Agar (TSA) and experiments were performed from double overnight cultures and done in triplicates or quadruplicates. Modified M9 buffer (mM9) was used for bacterial starvation conditions. mM9 contains 1 × M9 salts (M6030, Sigma Aldrich), 2 mM MgSO42−, 0.1 mM CaCl2, 1 mM Thiamine-HCl, 0.05 mM Nicotinamide and 1 ml/L TMS3 [19]. For in vitro assays using daptomycin, 50 mg/l Ca2+ was added, and for fosfomycin, 25 mg/l glucose-6-phosphate was added. Antibiotic powder for injection solutions was diluted in 0.9% NaCl solution. The following antibiotics were used: Daptomycin (“Cubicin”, Merck Sharp & Dohme), fosfomycin (InfectoPharm GmbH), vancomycin (“Bactocin”, MIP Pharma GmbH), rifampicin (“Rifadin”, Sanofi S.r.I.) and cefuroxime (Fresenius Kabi AB).

2.3. Quantification of minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) and antibiotic interactions

The MIC of daptomycin, vancomycin and rifampicin was determined using broth dilution, whereas MIC of fosfomycin was determined using agar dilution in accordance with the European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST) regulations 2023 (http://www.eucast.org).

Checkerboard assays (n ≥ 3) were performed to determine potential synergy between combinations of a primary antibiotic and rifampicin (daptomycin and rifampicin; fosfomycin and rifampicin; and vancomycin and rifampicin). A 2-fold dilution series of the primary antibiotic was performed horizontally on a 96-well plate in TSB and subsequently a 2-fold dilution series of rifampicin was performed laterally. MRSA was added to a starting concentration of 5 × 105 CFU/ml. The 96-well plates were incubated at 50 rpm, 37 °C overnight. Synergy, no interaction and antagonism was determined by calculating the Fractional Inhibitory Concentration Index (FICI) [20].

2.4. Quantification of biocidal activity against inactive cells

The method for preparing inactive cells was adapted from Ref. [21]. An overnight culture of MRSA was diluted 1:1000 and incubated overnight once more in growth media at 180 rpm, 37 °C. Cells were then harvested by centrifugation (13,150×g for 10 min), washed, and resuspended to OD600 = 1 in mM9 to maintain a metabolically inactive state or in TSB to stimulate metabolic activity. The washed cells were added to 96-well plates containing mM9 or TSB with 0 × , 10 × , 50 × or 100 × MIC daptomycin, fosfomycin or vancomycin and w or w/o 10 mg/l rifampicin. The starting concentration of cells was ∼5 × 107 CFU/ml and the 96-well plate was incubated at 50 rpm, 37 °C overnight. CFU at T0 was determined from the culture prior to mixing with antibiotics, and at T24 after incubation with antibiotics. Bacteria in 100 μl samples were washed twice in mM9 by centrifugation (as described above), and resuspending mM9 before 10-fold dilution and plating on TSA for CFU enumeration after 24 h incubation at 37 °C. In this assay, the inoculum concentration was 100 fold higher than the EUCAST standard for antimicrobial testing in order to detect a broader range of biocidal activities, i.e. up to 5 log reduction in CFU.

2.5. Quantification of biocidal activity against active and inactive cells of MRSA biofilm

Three overnight cultures of MRSA were calibrated to OD600 = 1 in TSB and inoculated in a 96-well plate (working volume 160 μL). A Nunc Immuno TSP lid (Thermo Scientific™) was carefully placed in the matching wells and the plate was incubated for 1h at 37 °C, 50 rpm. The lid was then aseptically transferred to a new plate containing 160 μL fresh TSB and incubated for 24h after which it was transferred to a new plate containing fresh TSB. Following a total incubation period of 48h, the lid was washed for 2 min in 180 μL mM9 and incubated w/o shaking in a plate containing 180 μL mM9 or TSB with 50 × MIC daptomycin, fosfomycin or vancomycin, w or w/o 10 mg/l rifampicin for 24h at 37 °C. The peg-lid was then washed for 2 min in 180 μL mM9 and transferred to a new plate containing the same buffer. Sonication was carried out for 10 min to dislodge the cells. CFU was determined as described above.

2.6. Inoculation of vascular grafts

PTFE tubing (ElringKlinger Kunststofftechnik GmbH, Polytetraflouraneethylene tube 0.6 × 1.1 (0.25) mm virgin) was used as vascular grafts, a commonly used material for prosthetic vascular grafts in humans [3]. The tubing was preconditioned with rat plasma for 2 h at 37 °C. An overnight culture was prepared from a single colony of MRSA in Brain Heart Infusion Broth (BHI), incubated at 180 rpm and 37 °C for 16–18 h. The culture was then diluted in BHI to OD600 = 0.1 (5 × 107 CFU/ml) and supplied with 10 % heparinized rat plasma before filled on syringes. The syringes were connected to the PTFE tubing and the culture was run through the tubing at 200 μl/min for 2 h at 37 °C (Harvard Apparatus, PHD ULTRA™ Syringe Pump). The tubing was cut into 0.6 mm tubes, and stored overnight in PBS-soaked gauze at 4 °C.

2.7. Rat prosthetic vascular graft infection model

A total of 95 adult male Sprague Dawley rats (Janvier Labs, Le Genest-Saint-Isle, France) were used. At arrival, rats weighed between 250 and 300 g each. Animals had an acclimatisation period of one week after arrival. They were housed at the animal facilities at the Department of Biomedicine, Aarhus University, in double decker cages at standard room temperature, humidity and 12 h day/night cycle with food and water ad lib.

The rat VGEI model used in this study has previously been described [17]. Briefly, pre-operatively the rats were given cefuroxime (50 mg/kg, B. Braun, Melsungen, Germany) and buprenorphine (0.05 mg/kg, “Temgesic”, Indivior, Slough, UK) subcutaneously and then anesthetized with isoflourane (Zoetis, Helsinki, Finland). The carotid artery was exposed by an incision through the neck. The artery was clamped and a small cut was made to insert the pre-inoculated graft in the carotid artery. Blood circulation was then re-established through the artery and graft. The wound was closed with sutures and disinfected. Buprenorphine was administered in the water (0.3 mg/ml) the first 4 days post-surgery.

After 10 days of infection, antibiotic treatment was commenced. Animals were randomised by letter randomisation to one of each treatment groups: 1) NaCl 0.9% once daily (n = 15), 2) fosfomycin 75 mg/kg/24 h (“Infectopharm”, InfectoPharm GmbH, Heppenheim, Germany) (n = 13), 3) fosfomycin 75 mg/kg/24 h + rifampicin 25 mg/kg/12 h (“Rifadin”, Sanofi,” Sanofi, Milano, Italy) (n = 14), 4) daptomycin 100 mg/kg/24 h (“Cubicin”, Merck Sharp & Dohme, BN Haarlem, the Netherlands (n = 13), 5) daptomycin 100 mg/kg/24 h + rifampicin 25 mg/kg/12 h (n = 13), 6) vancomycin 50 mg/kg/12 h (“Bactocin”, MIP Pharma GmbH, Blieskastel, Germany) (n = 13), 7) vancomycin 50 mg/kg/12 h + rifampicin 25 mg/kg/12 h (n = 13). All administrations were given intraperitoneally, treatment duration was seven days. Dosing frequency and actual dosage was based on previous studies on all drugs and reflect common practice when using the selected antibiotics in rat models of S. aureus infection [[22], [23], [24], [25]]. Rats were sedated followed by removal of the graft and euthanized by cervical dislocation 36 h after the final administration of treatment to ensure antibiotics washout before CFU enumeration. Spleen, liver and kidneys were then removed for CFU enumeration.

2.8. Quantification of bacterial load

Vascular grafts were placed in 1 ml PBS, vortexed for 30 s, sonicated at 45 kHz and 110 W for 5 min and then vortexed for 30 s. Organ samples were homogenized in a Precellys 24 tissue homogenizer (Bertin Technologies, Saint Quentin, France) at 2 × 20 s 5000 rpm, stored in wet ice for 5 min and then run again for 2 × 20 s 5000 rpm. Sonicate from each graft and homogenate from each organ were then serially diluted in triplicates, plated on 5% sheep blood agar plates and incubated for 24 h at 37 °C.

3. Statistics and power calculation

Differences in log CFU/ml were assessed via unpaired Student’s t-test for normally distributed data, and Mann-Whitney test for other data followed by a post hoc analysis using the Holm-Bonferroni test. For multiple comparisons of normally distributed data, a one-way ANOVA with post hoc Fisher’s LSD was performed. Differences in cure rate were assessed via Fisher’s exact test. Based on previous experiments in the same model, we assumed a 0% cure rate in animals treated with monotherapy of antibiotics and a >40% cure rate in animals treated with combination treatment of antibiotics + rifampicin [17]. Based on power calculations this resulted in a sample size of 13 rats pr. treatment group. All statistical calculations and figures were made with GraphPad Prism (v. 9.5.1 (733) for Windows, GraphPad Software, San Diego, California USA, www.graphpad.com).

4. Results

4.1. Rifampicin combinations are additive or weakly synergistic against actively growing MRSA

We first determined the MIC for the antibiotics alone against MRSA (Table 1), which was susceptible to all relevant antibiotics.

Table 1.

Minimum Inhibitory Concentrations (MICs) of used antibiotics against MRSA. The MIC values were determined in TSB (daptomycin, vancomycin and rifampicin) or on TSA (fosfomycin according to EUCAST recommendations, 2023). n ≥ 3. *As determined from EUCAST breakpoint Tables 2023 and v 13.1. **Rifampicin MICs varied due to emergence of resistance. For n = 15 (biological replicates) MIC assays, the value was determined to be between 0.0078125 and 0.03125 mg/l.

| Antibiotic | MIC (mg/l) | EUCAST breakpoints |

|---|---|---|

| Daptomycin | 2 | 1 |

| Fosfomycin | 16 | 32* |

| Vancomycin | 2 | 2 |

| Rifampicin | 0.03125** | 0.06 |

Combining rifampicin with either daptomycin or vancomycin did not result in synergistic or antagonistic effects on growth inhibition (Table 2, Figs. S1A and S1B). Combination with fosfomycin, however, resulted in a weak synergistic effect at 1/8 × MIC rifampicin combined with 1/16 or 1/32 × MIC fosfomycin (Table 2 and Fig. S1C). Unsurprisingly, rifampicin resistance developed, when used as monotherapy (data not shown), but we observed no resistance in combination therapy with daptomycin (Fig. S1A) or fosfomycin (Fig. S1B). Interestingly, vancomycin did not prevent rifampicin resistance development during combination treatment, as seen by growth at multiple concentrations above the rifampicin MIC (Fig. S1C).

Table 2.

FICI values for antibiotic combinations. Synergy or antagonism or antibiotic combinations was determined through the Fractional Inhibitory Concentration Index (FICI) and is defined as: FICI ≤0.5 corresponds to synergy and FICI>4 corresponds to antagonism. Any value between synergy and antagonism corresponds to additive interaction. *At combinations of 1/8 × MIC rifampicin with 1/16 or 1/32 × MIC fosfomycin, there was a weak synergistic effect. At all other tested concentrations there was additive.

| Antibiotic combination | FICI range | Effect |

|---|---|---|

| Daptomycin + rifampicin | 1.00–1.50 | Additive |

| Fosfomycin + rifampicin | 0.37–0.62 | Synergistic or additive * |

| Vancomycin + rifampicin | 0.62–2.50 | Additive |

4.2. Rifampicin is antagonistic against bactericidal antibiotics

As monotherapy, all antibiotics were effective against actively growing bacteria, leading to >3 log reduction in CFU by daptomycin and vancomycin at all tested concentrations, while fosfomycin was less effective (Fig. 1A, 1C, 1E). Against inactive cells, daptomycin was the only antibiotic with substantial biocidal activity (Fig. 1B). However, the antimicrobial effect was only significant at 50 and 100 × MIC (50 × MIC: 1.72 ± 0.46 log reduction in CFU, p = 0.003, one-way ANOVA, 100 × MIC: 3.70 ± 3.28–3.76 log reduction in CFU, p = 0.0286, Mann Whitney test). Fosfomycin also had an antimicrobial effect on inactive cells at 100 × MIC (p = 0.0217, one-way ANOVA), but only resulted in a modest reduction in CFU by 0.38 ± 0.14 log CFU (Fig. 1D).

Fig. 1.

Active and inactive populations of MRSA (planktonic and biofilms) treated with antibiotic monotherapy or in combination with rifampicin. 24 h treatment of planktonic cells (A, B, C, D, E, F) or biofilms (G, H), treated with daptomycin, fosfomycin, or vancomycin as mono-therapy or in combination with rifampicin (10 mg/l). For planktonic cultures, the change in CFU during the incubation is displayed. For biofilms, the absolute values of surviving bacteria is shown. Symbols with an “ × ” denote that this sample had no visible survival and the value is under the limit of detection (LOD). Statistical tests compare treated samples with untreated controls, and mono-vs. combination therapy. n = 3–4 (one-way ANOVA, ns: p > 0.05, *p = 0.0217–0.0435, **p = 0.003–0.0079, ***p = 0.0005, ****p < 0.0001) (Mann-Whitney test, $p = 0.0286).

The combination of daptomycin, fosfomycin or vancomycin with rifampicin had little or no impact on the antibiotics’ effect on inactive cells (Fig. 1B, 1D, 1F). Thus, we could not corroborate previous studies’ indication that rifampicin combination therapy is more effective against biofilm infections due to the superior antimicrobial activity against inactive cells [13,14]. In contrast, rifampicin had a very strong antagonistic effect on the antibiotics’ biocidal activity against active bacteria (Fig. 1A, 1B, 1C).

The concentration of rifampicin used in this experiment was above the MIC. Bacterial growth in control samples that received rifampicin alone is thus indicative of development of resistance. In one group of samples (the control for those receiving fosfomycin and rifampicin), resistance only developed in 1 of 4 replicates (Fig. 1C). However, this discrepancy does not impact the further analysis.

Treatment of MRSA biofilms showed a similar trend (Fig. 1G and H). Of the three antibiotics, neither could significantly reduce survival of biofilms treated in buffer although samples treated with daptomycin monotherapy and combination therapy had the lowest survival following treatment (Fig. 1H). When treating biofilms with active bacteria in laboratory media, the antibiotics were highly effective as monotherapies, and rifampicin had an antagonistic effect although the antagonistic effect was not as stark in treatment of biofilms as it was in the treatment of planktonic bacteria (Fig. 1G). The effectiveness of antibiotic monotherapy when treating biofilms in laboratory media reveal that most of the cells in these biofilms are in a metabolically active state where they are susceptible to antibiotics.

4.3. Animals tolerated both surgery and antibiotic treatment well and regained initial weight by day eight post-surgery

For the in vivo experiment using the rat VGEI model, we included 94 animals based on our sample size calculation. Out of these, 91 animals were included in the final dataset. Two rats in the NaCl group were excluded, one died on day two post infection due to respiratory failure, which autopsy revealed was caused by a pulmonary atelectasis and one was excluded due to contamination of agar plates at the analysis step. One rat in the fosfomycin and rifampicin group was excluded due to an internal haemorrhage, probably related to an injection. All included animals tolerated surgery and subsequent treatment well, having regained their baseline weight at day 8 post-surgery and with a mean weight increase in all groups of 1.16 ± 0.04% (mean ± SD) (Fig. S3).

4.4. Daptomycin and rifampicin combination therapy is superior at sterilising grafts from VGEI

All treatment groups, except vancomycin, were superior to NaCl in reducing the bacterial burden on grafts (Fig. 2, p < 0.05, Mann-Whitney test). Adding rifampicin to either vancomycin or daptomycin significantly improved efficacy (6.56 log 10 CFU/ml, 95% CI 4.90–7.26 for vancomycin vs. 3.06 log [10] CFU/ml, 95% CI 1.00–6.29 for vancomycin and rifampicin, p = 0.0003) and (2.92 log 10 CFU/ml, 95% CI 1.00–6.44 for daptomycin vs. 0.00 log 10 CFU/ml, 95% CI 0.00–2.30 for daptomycin and rifampicin, p = 0.0058) (Fig. 2). However, the combination of fosfomycin with rifampicin did not increase efficacy of treatment compared to fosfomycin monotherapy (4.40 log 10 CFU/ml, 95% CI 1.00–6.50 for fosfomycin vs. 4.32 log 10 CFU/ml, 95% CI 2.00–5.03 for fosfomycin and rifampicin, p > 0.99).

Fig. 2.

Bacterial load on vascular grafts following 7 days of antibiotic treatment. Each data point represents the median log 10 CFU/ml of triplicates from one graft. The asterisks represent pairwise comparison of each monotherapy with combination therapy with rifampicin (Fisher’s exact test ns: p > 0.05, **p ≤ 0.005). NaCl = Control, DAP = Daptomycin, RIF = Rifampicin, FOS = Fosfomycin, VAN = Vancomycin.

Rifampicin and daptomycin treatment sterilized 62% of infected grafts, which was a significant improvement compared to the 8 % achieved by daptomycin monotherapy (p = 0.016, Fishers exact test) (Fig. 2). No such improvement was observed when combining rifampicin with vancomycin (15% vs. 0%, p = 0.48) or fosfomycin (15% vs. 8%, p > 0.99). Daptomycin and rifampicin even yielded higher cure rates when compared to all other treatments (Table 3)

Table 3.

Comparison of cure rates for each treatment compared to daptomycin and rifampicin treatment.

| Treatment Groups | Fisher’s exact test (p < 0.05) |

|---|---|

| Daptomycin and Rifampicin vs. Daptomycin | 0.012 |

| Daptomycin and Rifampicin vs. Fosfomycin | 0.041 |

| Daptomycin and Rifampicin vs. Fosfomycin and Rifampicin | 0.012 |

| Daptomycin and Rifampicin vs. Vancomycin | 0.001 |

| Daptomycin and Rifampicin vs Vancomycin and Rifampicin | 0.012 |

All bacterial isolates from explanted vascular grafts were susceptible to rifampicin following the EUCAST breakpoint for rifampicin (MIC ≤0.06 mg/l) (Table S1).

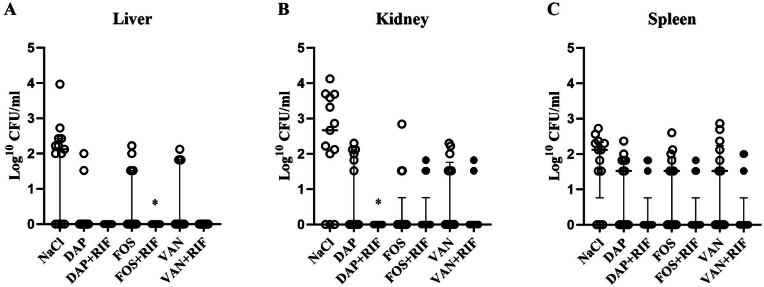

4.5. Combination therapy with rifampicin is superior in reducing bacterial load in organs

The bacterial load in homogenate from liver and kidney samples were significantly lower in all treatment groups compared to the control group (p ≥ 0.05) (Fig. 3A and B), but only combination therapy with rifampicin significantly reduced the bacterial load in all organs (liver, kidney and spleen) (Fig. 3). However, when comparing each monotherapy with rifampicin combination therapy, the addition of rifampicin only increased treatment efficacy for fosfomycin in the liver (p = 0.039, Mann-Whitney test, n = 13 for each treatment group) and for daptomycin in the kidneys (p = 0.015, Mann-Whitney test, n = 13 for each treatment group). These combinations also led to higher cure rates: fosfomycin and rifampicin vs. fosfomycin in the liver (100% vs. 27.78%, p = 0.0016, Fisher’s exact test) and daptomycin and rifampicin vs. daptomycin in the kidneys (100% vs. 53.85%, p = 0.015).

Fig. 3.

Bacterial load in organs following 7 days of treatment. Each data point represents median log 10 CFU/ml with interquartile range from triplicates of homogenate of (A) liver (B) left and right kidney (C) spleen. The asterisks represent pairwise comparison of each monotherapy with combination therapy with rifampicin (Mann-Whitney test *p ≤ 0.05). NaCl=Control, DAP = Daptomycin, RIF = Rifampicin, FOS = Fosfomycin, VAN = Vancomycin.

Finally, we tested whether the cumulated cure rate (i.e., sterilization of all investigated foci) could be improved by adding rifampicin. Of the tested combinations, only the addition of rifampicin to daptomycin treatment was able to achieve a significant increase in cumulated cure rate when comparing combination therapy to monotherapy (38.46% vs. 0%, p = 0.039) (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Cumulated cure rate of graft and organs. Each column represents percent of animals with no growth of bacteria from graft and organs (liver, kidney and spleen). NaCl = Control, DAP = Daptomycin, RIF = Rifampicin, FOS = Fosfomycin, VAN = Vancomycin. Asterisks represent pairwise comparison of monotherapy with combination therapy with rifampicin (Fisher’s exact test *p ≤ 0.05).

5. Discussion

In this study we assessed several antibiotics alone and in combination with rifampicin against MRSA in various experimental setups relevant for the treatment of VGEI. The best in vivo treatment response was observed in animals receiving daptomycin + rifampicin combination therapy, though the potency of this combination was not apparent from our preceding in vitro studies.

Previous in vivo studies on rifampicin based combination therapy against implant-associated infections in rodents have focused on bone and joint infection models, intravenous catheter and extravascular graft models [23,26]. To our knowledge, this is the first study to test these antibiotic combinations in a clinically relevant MRSA VGEI model. Our model mimics the clinical situation, in which the graft is situated inside an artery taking into consideration both flow, shear stress, and a clinically relevant graft material. As this is an animal study, it is unavoidable that there are differences in the pharmacokinetic profiles of the chosen antibiotics compared to humans, but dosages were chosen based on previous studies.

In contrast to previous studies of implant-associated MRSA infections [22,23,27], fosfomycin performed poorly, both in vitro and in vivo. It is possible that this is due to development of fosfomycin resistance. We did not test for fosfomycin resistance in all extracted samples, and therefore could not investigate if this is the case, which is a limitation of this study. Our MRSA strain did not develop fosfomycin resistance during 24 h in vitro experiments, but that does not exclude the possibility of resistance developing during the 7-d treatment in vivo. However a previous study on MRSA implant-associated osteomyelitis in Sprague Dawley rats (350–400g) did not observe any fosfomycin resistance development after four weeks of treatment using the same dose as in our study [22]. There are although major differences in both biofilm structure, the microbial environment and possibly also virulence factor between biofilms formed in bones and an intravascular environment such as in our VGEI model [28,29]. Therefore, the comparability between this study and our study is uncertain.

In concordance with our work, previous studies have also demonstrated that daptomycin and rifampicin is a potent combination against various other types of MRSA implant-associated infections [[30], [31], [32]]. However, a study by Revest et al. on biofilms formed on another material used for prosthetic vascular grafts (dacron) found, that addition of rifampicin to daptomycin therapy did not further reduce the bacterial load on dacron patches inserted subcutaneously in mice [33]. Compared to our study, this study had several limitations, mainly the short duration of treatment (48 h) and anatomical location of the implant (subcutaneous), which does not include the impact of e.g. flow and shear stress on the biofilm. In our study, the addition of rifampicin to daptomycin treatment was beneficial as it increased the cure in both graft and organs. However, it is noteworthy that some animals, in particular in the daptomycin and rifampicin group, had cured the infection on the grafts but not in the organs (Table S3). This could lead to re-infection of the implant, which a longer period from cessation of treatment to euthanasia could have shown.

In vitro daptomycin was also by far the most effective treatment against both active and inactive cells. For the inactive cells the antimicrobial effect was significant at 50 and 100 × MIC (100 and 200 mg/l) (p = 0.003) (Fig. 1B). This result is highly encouraging, as plasma concentrations >100 mg/l have been achieved in vivo [34]. However our in vitro data far from predicted the efficacy of the therapies in vivo. It is well known that the antibiotic susceptibility of bacteria in vitro does not extrapolate to the in vivo infectious environment. However, the contradiction is usually that antibiotics appear more effective in vitro only to exhibit reduced effect in vivo. In our study, the situation was reversed as in vitro analyses showed an antagonistic effect from rifampicin while rifampicin combinations improved the effect of monotherapies in vivo. Antagonism was previously described for rifampicin, as it arrests cell division and thereby protects bacteria from other biocidal antibiotics that specifically target actively growing cells [35,36]. Several studies even use a short rifampicin treatment to induce the persister phenotype in bacteria [21]. In contrast to other bactericidal antibiotics, daptomycin targets the cell membrane and it does not require e.g. active DNA replication or cell wall synthesis to take effect. One would therefore expect that arresting transcription with rifampicin has little impact on daptomycin’s antimicrobial activity, and this is indeed what Lobritz et al. showed [35]. Our contrasting results indicate that rifampicin’s effect on daptomycin’s biocidal activity is either strain-dependent and/or affected by the incubation conditions as Lobritz et al. monitored survival as post- or pre-treatment with rifampicin and only within 4 h incubation in contrast to our experiments. In order to more closely resemble a biofilm infection, we grew an MRSA biofilm using the Calgary Biofilm Device and treated the biofilm with antibiotic monotherapy and combination therapy [37]. Although this setup is fast and easily reproducible, it still does not mimic the in vivo vascular conditions. Instead, a microfluidic flow cell coated with serum and inoculated with MRSA could instead be used [38]. This method would more closely resemble PVGI’s, although it would be more time consuming and less reproducible.

Antagonism was only observed when quantifying bactericidal activity against active bacteria, while rifampicin had no effect on inactive cells. The antagonistic effect of rifampicin during treatment of biofilms therefore reveals that despite growing as biofilms, the cells are active and susceptible to antibiotic when treated in laboratory media. In vivo, the infectious microenvironment is heterogenous, and we do not know the proportion of active vs inactive bacteria at different sites in the animal. If the infecting populations mainly consist of persister cells, rifampicin will have no antagonistic effect. We did not observe any antagonistic effect of rifampicin antibiotic combinations in vivo or against inactive cells in vitro. It should also be noted that the antimicrobial treatment was longer in vivo. It is thus possible that the bacterial population in vivo mainly consists of persister cells similar to the inactive cell population in our in vitro experiments, and that the prolonged antimicrobial therapy is the key to overcoming the antimicrobial tolerance of this population. Detection of the causing pathogen in infections such as VGEI is most commonly done by culture method in the clinic and therefore inactive bacteria and persister cells might not be detected, which might lead to culture negative samples falsely ruling out infection. Therefore it is important to assess if the therapeutic outcome in vivo is better predicted from the antimicrobial activity against inactive cells, which is not standard practice today.

Moreover, we do not know to which extent the therapy must be bactericidal, or whether growth inhibition is sufficient to enable the immune system to clear the infection. It should be stressed that biofilm infections notoriously cannot be cleared by the immune system, and we therefore expect that the infected implants will only be sterilized by the action of biocidal antibiotics. If the infected implants primarily consist of inactive cells, our results corroborate that daptomycin is the most effective monotherapy.

6. Conclusion

Our findings demonstrate the need to test antibiotics under various experimental conditions, when addressing their potential for complicated infections – such as vascular graft or endograft infections. Our data further encourage future clinical studies on daptomycin and rifampicin combination for early VGEI caused by MRSA.

Funding

This work was supported by the Novo Nordisk Foundation (Grant no. Project No. NNF19OC0058357) and The Hede Nielsen Family Foundation.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Mikkel Illemann Johansen: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Visualization, Validation, Software, Project administration, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. Maiken Engelbrecht Petersen: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Visualization, Validation, Software, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation. Emma Faddy: Writing – review & editing, Investigation, Data curation. Anders Marthinsen Seefeldt: Writing – review & editing, Investigation. Alexander Alexandrovich Mitkin: Writing – review & editing, Investigation, Formal analysis. Lars Østergaard: Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Project administration, Funding acquisition. Rikke Louise Meyer: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Supervision, Resources, Project administration, Methodology, Funding acquisition, Formal analysis, Conceptualization. Nis Pedersen Jørgensen: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Validation, Supervision, Project administration, Methodology, Formal analysis, Conceptualization.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare the following financial interests/personal relationships which may be considered as potential competing interests: Rikke Louise Meyer reports financial support was provided by Novo Nordisk Foundation. Lars Østergaard reports financial support was provided by Novo Nordisk Foundation. Nis Pedersen Jørgensen reports financial support was provided by The Hede Nielsen Family Foundation. The corresponding author Rikke Louise Meyer is an editor for Biofilms. If there are other authors, they declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgement

Parts of the study were presented at the ECCMID 2022 conference in Lisbon, Portugal.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bioflm.2024.100189.

Contributor Information

Rikke Louise Meyer, Email: rikke.meyer@inano.au.dk.

Nis Pedersen Jørgensen, Email: Nisjoerg@rm.dk.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

Data availability

Data will be made available on request.

References

- 1.Sixt T., et al. Long-term prognosis following vascular graft infection: a 10-year cohort study. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2022;9:ofac054. doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofac054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Legout L., et al. Characteristics and prognosis in patients with prosthetic vascular graft infection: a prospective observational cohort study. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2012;18:352–358. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2011.03618.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.'s choice - European society for vascular surgery (ESVS) 2020 clinical practice guidelines on the management of vascular graft and endograft infections. Chakfé N., et al., editors. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2020;59:339–384. doi: 10.1016/j.ejvs.2019.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Anagnostopoulos A., et al. Inadequate perioperative prophylaxis and postsurgical complications after graft implantation are important risk factors for subsequent vascular graft infections: prospective results from the vascular graft infection cohort study. Clin Infect Dis. 2019;69:621–630. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciy956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.FitzGerald S.F., Kelly C., Humphreys H. Diagnosis and treatment of prosthetic aortic graft infections: confusion and inconsistency in the absence of evidence or consensus. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2005;56:996–999. doi: 10.1093/jac/dki382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Otto M. Staphylococcal biofilms. Microbiol Spectr. 2018;6 doi: 10.1128/microbiolspec.GPP3-0023-2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lewis K. Persister cells, dormancy and infectious disease. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2007;5:48–56. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brauner A., Fridman O., Gefen O., Balaban N.Q. Distinguishing between resistance, tolerance and persistence to antibiotic treatment. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2016;14:320–330. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro.2016.34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Darouiche R.O. Treatment of infections associated with surgical implants. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:1422–1429. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra035415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zimmerli W., Widmer A.F., Blatter M., Frei R., Ochsner P.E. Role of rifampin for treatment of orthopedic implant-related staphylococcal infections: a randomized controlled trial. Foreign-Body Infection (FBI) Study Group. JAMA. 1998;279:1537–1541. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.19.1537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Osmon D.R., et al. Diagnosis and management of prosthetic joint infection: clinical practice guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2013;56:e1–e25. doi: 10.1093/cid/cis803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zimmerli W., Sendi P. Role of rifampin against staphylococcal biofilm infections in vitro, in animal models, and in orthopedic-device-related infections. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2019;63 doi: 10.1128/aac.01746-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu Y., et al. Optimal doses of rifampicin in the standard drug regimen to shorten tuberculosis treatment duration and reduce relapse by eradicating persistent bacteria. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2018;73:724–731. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkx467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Alexander C., et al. MazEF-rifampicin interaction suggests a mechanism for rifampicin induced inhibition of persisters. BMC Mol Cell Biol. 2020;21:73. doi: 10.1186/s12860-020-00316-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Coste A., et al. Use of rifampicin and graft removal are associated with better outcomes in prosthetic vascular graft infection. Infection. 2021;49:127–133. doi: 10.1007/s15010-020-01551-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Legout L., et al. Factors predictive of treatment failure in staphylococcal prosthetic vascular graft infections: a prospective observational cohort study: impact of rifampin. BMC Infect Dis. 2014;14:228. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-14-228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Johansen M.I., et al. Fibrinolytic and antibiotic treatment of prosthetic vascular graft infections in a novel rat model. PLoS One. 2023;18 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0287671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Diep B.A., et al. Complete genome sequence of USA300, an epidemic clone of community-acquired meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Lancet. 2006;367:731–739. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(06)68231-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Widdel F., Bak F. In: The prokaryotes: a handbook on the biology of bacteria: ecophysiology, isolation, identification, applications. Albert Balows, et al., editors. Springer; New York: 1992. pp. 3352–3378. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Odds F.C. Synergy, antagonism, and what the chequerboard puts between them. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2003;52:1. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkg301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Petersen M.E., et al. A novel high-throughput assay identifies small molecules with activity against persister cells. bioRxiv. 2023 doi: 10.1101/2023.04.13.536681. 2023.2004.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Poeppl W., et al. Efficacy of fosfomycin compared to vancomycin in treatment of implant-associated chronic methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus osteomyelitis in rats. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2014;58:5111–5116. doi: 10.1128/aac.02720-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Garrigós C., et al. Fosfomycin-daptomycin and other fosfomycin combinations as alternative therapies in experimental foreign-body infection by methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2013;57:606–610. doi: 10.1128/aac.01570-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Albac S., et al. Activity of different antistaphylococcal therapies, alone or combined, in a rat model of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus epidermidis osteitis without implant. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2020;64 doi: 10.1128/aac.01865-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Park K.H., Greenwood-Quaintance K.E., Mandrekar J., Patel R. Activity of tedizolid in methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus experimental foreign body-associated osteomyelitis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2016;60:6568–6572. doi: 10.1128/aac.01248-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Silva V., et al. Efficacy of dalbavancin against MRSA biofilms in a rat model of orthopaedic implant-associated infection. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2020;75:2182–2187. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkaa163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mihailescu R., et al. High activity of Fosfomycin and Rifampin against methicillin-resistant staphylococcus aureus biofilm in vitro and in an experimental foreign-body infection model. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2014;58:2547–2553. doi: 10.1128/aac.02420-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pavithra D., Doble M. Biofilm formation, bacterial adhesion and host response on polymeric implants--issues and prevention. Biomed Mater. 2008;3 doi: 10.1088/1748-6041/3/3/034003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Van de Vyver H., et al. A novel mouse model of Staphylococcus aureus vascular graft infection: noninvasive imaging of biofilm development in vivo. Am J Pathol. 2017;187:268–279. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2016.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.John A.K., et al. Efficacy of daptomycin in implant-associated infection due to methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus: importance of combination with rifampin. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2009;53:2719–2724. doi: 10.1128/aac.00047-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Saleh-Mghir A., Muller-Serieys C., Dinh A., Massias L., Crémieux A.C. Adjunctive rifampin is crucial to optimizing daptomycin efficacy against rabbit prosthetic joint infection due to methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2011;55:4589–4593. doi: 10.1128/aac.00675-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jørgensen N.P., et al. Hyperbaric oxygen therapy is ineffective as an adjuvant to daptomycin with rifampicin treatment in a murine model of Staphylococcus aureus in implant-associated osteomyelitis. Microorganisms. 2017;5 doi: 10.3390/microorganisms5020021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Revest M., et al. New in vitro and in vivo models to evaluate antibiotic efficacy in Staphylococcus aureus prosthetic vascular graft infection. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2016;71:1291–1299. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkv496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dvorchik B.H., Brazier D., DeBruin M.F., Arbeit R.D. Daptomycin pharmacokinetics and safety following administration of escalating doses once daily to healthy subjects. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2003;47:1318–1323. doi: 10.1128/aac.47.4.1318-1323.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lobritz M.A., et al. Antibiotic efficacy is linked to bacterial cellular respiration. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112:8173–8180. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1509743112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kwan B.W., Valenta J.A., Benedik M.J., Wood T.K. Arrested protein synthesis increases persister-like cell formation. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2013;57:1468–1473. doi: 10.1128/aac.02135-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ceri H., et al. The Calgary Biofilm Device: new technology for rapid determination of antibiotic susceptibilities of bacterial biofilms. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:1771–1776. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.6.1771-1776.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sternberg C., Tolker-Nielsen T. Growing and analyzing biofilms in flow cells. Curr Protoc Microbiol. 2006;1 doi: 10.1002/9780471729259.mc01b02s00. Unit 1B.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.