Abstract

Structures are of fundamental importance for diverse studies of lithium polysulfide clusters, which govern the performance of lithium–sulfur batteries. The ring-like geometries were regarded as the most stable structures, but their physical origin remains elusive. In this work, we systematically explored the minimal structures of Li2Sx (x = 4–8) clusters to uncover the driving force for their conformational preferences. All low-lying isomers were generated by performing global searches using the ABCluster program, and the ionic nature of the Li···S interactions was evidenced with the energy decomposition analysis based on the block-localized wave function (BLW-ED) approach and further confirmed with the quantum theory of atoms in molecule (QTAIM). By analysis of the contributions of various energy components to the relative stability with the references of the lowest-lying isomers, the controlling factor for isomer preferences was found to be the polarization interaction. Notably, although the electrostatic interaction dominates the binding energies, it contributes favorably to the relative stabilities of most isomers. The Li+···Li+ distance is identified as the key geometrical parameter that correlates with the strength of the polarization of the Sx2– fragment imposed by the Li+ cations. Further BLW-ED analyses reveal that the cooperativity of the Li+ cations primarily determines the relative strength of the polarization.

Short abstract

Li2Sx (x = 4−8) clusters, which govern the performance of lithium−sulfur batteries, were computationally studied with an energy decomposition approach to uncover the driving force for their conformational preferences. It was found that the controlling factor for isomer preferences is the polarization of the Sx2− fragment imposed by the Li+ cations, whose strength is correlated with the Li+···Li+ distance.

1. Introduction

Lithium–sulfur batteries1−6 have attracted a great deal of attention because of their remarkable theoretical capacity, energy density, and low cost.7−12 Still, the development of lithium–sulfur batteries faces a series of challenges on the path toward realization, and it is thus imperative to understand the reaction mechanisms therein.2,13−16 In particular, the lithium polysulfide clusters,1,17−19 which are produced in the charge/discharge processes, dramatically influence the performance of batteries.14,20 Significant efforts have been dedicated to comprehending their structures,21,22 spectra,23−27 properties, related interactions,21,28−30 and redox mechanisms.31,32 In all of these studies, the geometries of lithium polysulfide clusters, especially the lowest-lying structures, are of fundamental importance.

Studies have shown that the most stable isomers of Li2Sx (x = 4–8) possess ring-like geometries (Scheme 1a), in which each Li+ is bound to both terminal sulfur atoms of the Sx2– chain and keeps a limited distance from the other Li+.25,28,31,33 Seemingly, this ring-like configuration aligns with the concept of electrostatic compression,34 which states that the overall electrostatic attraction can be enhanced when ions are crosswise-arranged, since the intercation and interanion repulsions can be overcome by the cation–anion attractions. Therefore, the importance of electrostatic interaction in stabilizing the lowest-lying isomers can be deduced because of the quadrilateral binding pattern (Scheme 1b), which possesses crosswise-stacked ions and subsequently maximizes the electrostatic stability. However, a thorough explanation for the isomer preference requests a comprehensive comparison among all possible low-lying isomers, with all physical factors affecting the stability inspected. Moreover, as a ring structure is composed of three components including two Li+ and one dianion Sx2–, the cooperative effect in three-body interactions35 must be examined.

Scheme 1. (a) Ring-like Structure of Li2Sx (x = 4–8) and (b) Electrostatic Compression Model.

However, the conformational space of Li2Sx (x = 4–8) clusters becomes intricate with x increasing due to the wide range of likely geometries exhibited by the Sx2– dianions36−39 along with their multiple bonding sites for lithium cations. Thus, identifying low-lying isomers is a vital prerequisite for the study of conformational preferences. It is conventional to build up stable isomers based on chemical knowledge23,24 or generate various random structures for further optimizations and screening.27,32 Nevertheless, arbitrariness and incompleteness are inevitable for the structures constructed manually, and it is nearly impossible to achieve ergodic sampling on any potential energy surface due to the vast number of local minima for large clusters. In this regard, global search algorithms are invaluable, as they can efficiently navigate energy landscapes, offering us the most stable geometries and other low-lying isomers. For instance, the most stable structures of the (Li2S)n (n = 1–10) complexes were successfully determined by employing CALYPSO software,40 which is usually used for the predictions of crystal structures but valid for clusters as well.41−45 In addition, global optimizations have been utilized for searching crystalline structures of lithium polysulfides.26,46,47 The importance of global optimization has stimulated the development of dedicated software,48−52 among which the ABCluster is an ideal choice for chemical clusters.53,54 ABCluster employs a novel swarm intelligence algorithm55 and supports molecular mechanics and semiempirical and quantum mechanics calculations, allowing it to handle arbitrarily complicated components and topologies. Furthermore, the software is designed in a black-box manner to ensure user-friendliness.

We note that previous studies have analyzed some specific isomers of Li2Sx by examining the geometrical parameters, energies, and electron populations.21,22,29,31,32 Clearly, a more insightful understanding of the conformational preferences can be obtained by incorporating bonding analysis methods56−68 into a comprehensive study of all low-lying isomers. In this regard, the ab initio valence bond (VB) theory stands out as an ideal option. It offers a chemically intuitive solution for a molecular wave function, which is a linear combination of Lewis structures constructed from strictly localized and fully optimized orbitals.69,70 As the simplest ab initio VB method, the block-localized wave function (BLW) retains the localized orbitals but simplifies the multireference wave function to a single determinant, making it computationally efficient.71−74 Its associated energy decomposition (BLW-ED in short) approach can decompose the binding energy into physically meaningful energy components75−77 and has provided a multitude of new insights into the conventional and unconventional interactions.78−82 Moreover, the BLW method has the capabilities of geometrical optimization and spectral calculation for the strictly electron-localized state.

In this work, we explored the conformational preferences of Li2Sx (x = 4–8) clusters by comparing each of the low-lying isomers with the most stable structure in the same cluster. To achieve this, global optimizations were performed to identify all low-lying structures, and the BLW-ED approach was subsequently employed to elucidate the underlying physical factors that dominate the Li···S interactions and, critically, the relative stability. Furthermore, the cooperative effect in the accumulated Li···S interactions and its contribution to the conformational preferences were elucidated with the BLW-ED approach. Structures of low-lying isomers were thoroughly examined to reveal the key geometrical parameter(s) that can rationalize the primary factor for the conformational preferences.

2. Methods and Computational Details

2.1. BLW-ED Approach

The binding energy (ΔEb) represents the overall energy variation upon the formation of a complex from fully relaxed monomers and can be decomposed into five terms as expressed in eq 1. The deformation energy (ΔEdef) in eq 1 is usually defined as the energy cost to deform the optimal monomers to the geometries in the complex. For each x, the most stable isomer of the Sx2– dianion was selected as the universal reference to evaluate the deformation energy, ensuring that the binding energy can serve as an exact measure of the relative stability among isomers. Except for the deformation energy, the rest of the binding energy is defined as the interaction energy (ΔEint), which can be further decomposed. In detail, the frozen energy (ΔEF) is the energy change resulting from putting distorted monomers together without disturbing all orbitals. This frozen component comprises electrostatic interaction (ΔEele), Pauli exchange repulsion (ΔEPauli), and most electron correlation (ΔEcorr) at the DFT level (eq 2) and can be further decomposed utilizing the XEDA program.67 Polarization energy (ΔEpol) refers to the stabilization arising from the relaxation of electron densities within individual monomers, induced by the electric field exerted by the others. The complex can be further stabilized when electron delocalization among monomers is allowed. This part of energy lowering is defined as the charge transfer energy (ΔECT), to which the basis set superposition error (BSSE) correction is fully assigned. Finally, the difference in Grimme’s dispersion corrections between the complex and distorted monomers is denoted as the dispersion correction component (ΔED3). The combination of electron correlation (ΔEcorr) and dispersion correction component (ΔED3) corresponds to the total electron correlation energy (ΔEec) in accordance with their physical interpretations. In summary, the detailed BLW-ED scheme is expressed in eq 3.

| 1 |

| 2 |

| 3 |

Since each Li2Sx cluster consists of three monomers, there is a three-body cooperativity to be analyzed. The cooperative component in each energy term, denoted with the superscript “C”, can be evaluated by excluding all pairwise contributions (ΔEijy) from the total value (ΔEy) defined in eq 3 (y = int, ele, Pauli, pol, CT, and ec) as

| 4 |

The cooperative component in the interaction energy can be taken as the energy measure of the overall cooperative effect. A negative value of the cooperative component in the interaction energy indicates the positive cooperativity that reinforces the stability of system, while a positive value suggests the presence of anticooperativity.

2.2. Computational Details

Global searches for the isomers of Sx2– and Li2Sx (x = 4–8) clusters were performed using ABCluster combined with Gaussian16 at the M06-2X/def2-SVP theoretical level83,84 with Grimme’s D3 dispersion correction incorporated.85 One hundred generations were accomplished in the global searches. For each cluster, the lowest-lying structure and its isomers, which lie within 50.00 kcal/mol higher than the most stable one, were retained for further optimizations at the M06-2X-D3/def2-TZVP level using GAMESS(US).86 Vibrational frequencies were computed to ensure that optimal isomers were true minima on potential energy surfaces. Localized bond force constants were derived from the local vibrational mode theory.59,68 In addition, we reoptimized the low-lying isomers of Li2S4 at the M06-2X-D3/def2-TZVPD level of theory and found that their relative stabilities were barely changed by the additional diffuse functions (Figure S1). Relative Gibbs free energies and binding energies were calculated by taking the values of the lowest-lying isomer as references. There are excellent linear correlations between relative Gibbs free energies and binding energies, with the slopes close to one (Figure S2). Thus, we focused on analyzing the binding energies to explain the isomer preference.

BLW calculations were carried out using the in-house version of GAMESS(US), with three blocks defined for monomers (one Sx2– and two Li+). For the lowest-lying isomers, the geometries of the strictly electron-localized states (i.e., no electron movement between Sx2– and Li+ cations) with the BLW method were optimized and compared with the regular DFT results, with the electron movement from Sx2– to Li+ cations allowed through the minimized root-mean-square value of deviations (RMSD) of atom coordinates. This was accomplished with the visual molecular dynamics (VMD) program.87 QTAIM theory was employed to inspect the nature of the Li···S interactions using Multiwfn software.88,89

3. Results and Discussion

Selected geometries are listed in Figure 1. For clarity, yellow tubes are used for the Sx2– framework, while Li···S interactions are denoted with dotted lines when any Li···S distance is shorter than the sum of their ionic radii (2.60 Å). The low-lying isomers of a Li2Sx (x = 4–8) cluster are denoted as “x – n”, where x represents the number of sulfur atoms and n is the sequential number arranged in an ascending order of relative energies. Geometries of all low-lying isomers are shown in Figure S3.

Figure 1.

Optimized geometries of (a–e) global minima of Sx2– dianions (x = 4–8) with charges derived from the natural population analysis, (f–j) global minima of Li2Sx (x = 4–8) clusters, (k–m) additional low-lying isomers of Li2S4, and (n, o) chain-like structures of Li2S7 and Li2S8.

As shown in Figure 1a–e, chain structures of Sx2– were proved to be the lowest-lying conformers through global optimizations. This is reasonable because the net negative charges are mainly localized on the terminal sulfur atoms in chain structures, implying minimized Coulombic repulsion. The most stable structures of Li2Sx (x = 4–8) clusters are shown in Figure 1f–j, which exhibit the ring-like characteristics (Scheme 1a). The geometries of low-lying isomers become increasingly diverse with the cluster size increasing (Figure S3), as the Sx2– framework can adopt either various nonbranching structures or branching structures. Notably, the quadrilateral binding pattern (Scheme 1b) was found in most isomers, while geometries with far-separated Li+ cations were also observed. Here, the simplest cluster Li2S4 can serve as an illuminating example. Isomers 4-01 and 4-04 are built up with the nonbranching conformers of S42– and closely located Li+ cations, while a trigonal pyramidal (branching) dianion is observed in isomers 4-02 and 4-03, where Li+ cations are sufficiently separated. In the chain-like structures of Li2S7 and Li2S8 (Figure 1n,o), two Li+ cations are separated further away. Although these two isomers take the most favorable chain conformations for the Sx2– fragment, they exhibit much lower stabilities (34.9 and 38.1 kcal/mol) compared with their corresponding lowest-lying structures.

Bonding analyses were conducted on the lowest-lying isomers to explore the nature of the Li···S interactions therein. Individual Li···S bonds (Figure 1f–j) in the quadrilateral bonding regions were confirmed through the bond force constants and the bond critical points (BCPs), which exhibit positive Laplace values (Table 1), implying closed-shell interactions. Remarkable strengths of the accumulated Li···S interactions were evidenced by the extremely high binding energies ranging from −370.9 to −414.2 kcal/mol. Obviously, the binding energies are predominantly governed by electrostatic interactions, suggesting the ionic nature of Li···S bonds. Polarization and charge transfer interactions emerge as the second- and third-most important attractive forces, with electron correlation contributing the least to the overall stability. The governing role of electrostatic interaction in the binding energy was observed across all low-lying isomers (Table S1). For each of the lowest-lying isomers, the optimal structures of both electron-delocalized and electron-localized states were compared, resulting in minimized RMSD of atomic coordinates (less than 0.059 Å; Figure 2). Hence, covalency contributes negligibly to the Li···S bonds in the most stable isomers, where the Li···S bonds are ionic.

Table 1. BLW-ED Results (in kcal/mol), Average Bond Force Constants (k, in mDyn/ Å), Average Values of Electron Density (ρ, in a.u.), and Laplace Values (∇2ρ, in a.u.) at the BCPs of All Li···S Interactions in the Lowest-Lying Isomers.

| x | ΔEdef | ΔEele | ΔEPauli | ΔEpol | ΔECT | ΔEec | ΔEb | k | ρ | ∇2ρ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4 | 8.7 | –377.1 | 55.9 | –80.8 | –15.1 | –5.8 | –414.2 | 0.498 | 0.025 | 0.123 |

| 5 | 15.3 | –360.6 | 55.3 | –88.9 | –14.3 | –5.6 | –398.8 | 0.502 | 0.025 | 0.118 |

| 6 | 18.4 | –341.5 | 52.3 | –96.7 | –15.6 | –5.6 | –388.7 | 0.485 | 0.025 | 0.120 |

| 7 | 25.6 | –331.0 | 53.1 | –104.9 | –15.0 | –5.7 | –377.9 | 0.415 | 0.025 | 0.112 |

| 8 | 27.9 | –328.3 | 55.5 | –105.8 | –14.6 | –5.6 | –370.9 | 0.483 | 0.025 | 0.114 |

Figure 2.

Comparison of optimal structures of electron-delocalized (in yellow) and electron-localized states (in gray) for the lowest-lying (a) Li2S4, (b) Li2S5, (c) Li2S6, (d) Li2S7, and (e) Li2S8, with the corresponding RMSD values denoted.

Electrostatic interaction is also primarily responsible for the reduction of the binding energy in the lowest-lying isomer with the size of the cluster growing (Table 1). In fact, there is a good linear correlation between ΔEele and ΔEb. This trend is understandable because the net negative charges on the terminal sulfur atoms decrease with increasing size of the Sx2– dianion (Figure S4a). In sharp contrast, as the size of the cluster grows, polarization is significantly enhanced due to the increased average polarizability of Sx2– (Figure S4b). In fact, an excellent linear correlation with a negative slope between ΔEpol and ΔEb can be observed. Another energy term that varies with x is the deformation energy. It increases as the dianion Sx2– gets longer, implying enhanced strain from Li2S4 to Li2S8. This is reasonable because a longer Sx2– dianion requires more deformation cost to transform from the most favorable chain-like structure to the semicircular geometry in the complex Li2Sx. The rest of the three energy components, including the charge transfer, Pauli exchange repulsion, and electron correlation, are contingent on orbital overlaps between blocks and barely vary by the size of the Sx2– dianion.

Figure 3 displays the relative values of individual energy components with the most stable isomers of Li2Sx clusters as the respective references. Therefore, positive values mean unfavorable impact on the conformational preference. A total of 95 low-lying isomers were retained in this work of five Li2Sx clusters (x = 4–8), and 90 relative binding energies were analyzed as five lowest-lying isomers serve as zero points. Polarization emerges as the primary determinant for conformational preferences in most cases (58/90), followed by the deformation energy, which dominates the relative binding energies of 23 isomers. Usually, relative stabilities of isomers with branched Sx2– frameworks are dominated by the deformation energy, because the semicircular geometries (unbranching) of the Sx2– fragment in the lowest-lying structures undergo less deformation and thus are much more stable than the branching structures. Interestingly, the electrostatic interaction, which rules the Li···S interactions, governs the relative stabilities of only 9 isomers and contributes favorably to the relative stabilities of 63 isomers. In other words, most geometries exhibit stronger electrostatic interactions than the quadrilateral pattern of the Li···S bonds (Scheme 1b) in all lowest-lying isomers. For instance, isomer 4-03 (Figure 1l) features much stretched distance between Li+ cations compared to the lowest-lying structure (3.824 Å vs 2.841 Å) but with more attractive electrostatic interaction (−391.2 vs −377.1 kcal/mol). Notably, the global minima exhibit the strongest polarization among all low-lying isomers when x equals 4, 6, and 7. For Li2S5 and Li2S8, polarization interaction in the most stable isomers consistently ranks among the top three in all low-lying structures. None of the relative binding energies are governed by the Pauli exchange repulsion, charge transfer interaction, or electron correlation.

Figure 3.

Relative values of all energy components in the BLW-ED analyses for (a) Li2X4 and Li2X5, (b) Li2X6, (c) Li2X7, and (d) Li2X8.

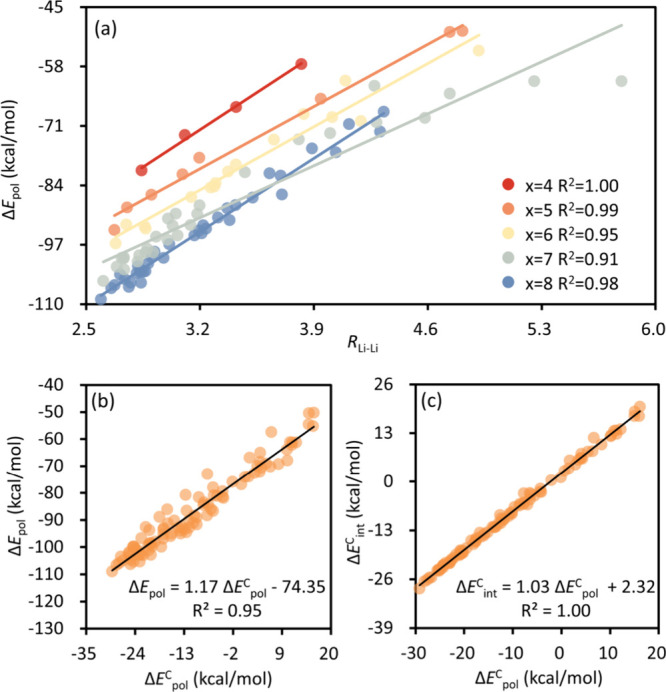

To understand the geometric correlations with the polarization energy term, we explored various structural parameters and eventually identified the Li+···Li+ distance as the principal index for polarization. Figure 4a shows that for each cluster, the strengths of polarization correlate with the Li+···Li+ distances approximately in linear manners. The interpretation for this correlation is that a close arrangement of the two cations leads to an enhanced resultant electric field, which ultimately exerts an enhanced force for the polarization within the Sx2– dianion. This also explains the remarkable polarization energies observed in the lowest-lying isomers aligned with the characteristic quadrilateral binding pattern (Scheme 1b), where Li+ cations are closely positioned. The strength of polarization can be quantitatively elucidated by examining the cooperative effect. Figure 4b shows that the polarization energy beautifully correlates with its cooperative component linearly. This suggests that the relative strength of polarization is primarily governed by the cooperative effect. Furthermore, the cooperative components of both total interaction and polarization energies also exhibit a linear correlation (Figure 4c), indicating that the overall cooperative effect is predominantly dominated by polarization interactions. We further assessed the cooperative components of all of the physical factors in the BLW-ED analyses (Table S2). The frozen energy exhibits a trivial many-body effect (−1.22 to 0.33 kcal/mol) due to the use of unadjusted orbitals in its evaluation. Consequently, we did not further decompose the frozen term in the analysis of the cooperative effect. The dispersion correction, which has minimal impact on the interaction energy, also contributes little to the cooperative effect (0.00–0.07 kcal/mol). Differently, charge transfer exhibits an anticooperative effect (0.51–5.97 kcal/mol) in all isomers due to the competition between the Li+ cations in taking electrons from the Sx2– dianion.

Figure 4.

(a) Correlation between the polarization energy and the Li···Li distance for all low-lying isomers of each Li2Sx (x = 4–8) cluster. (b) Correlation between the polarization energy and its cooperative component and (c) correlation between cooperative components of total interaction and polarization energies of all isomers.

The anticooperative effect was observed in the interaction energies of 23 isomers, marked with “ACE” in Figure S3. In these cases, Li+ cations are usually distanced from each other, with the Sx2– dianion (or portion of it) sandwiched in between. Chain-like isomers and isomer 6-13 serve as illustrative examples, as depicted in Figure 5, where the electron density variation or polarization within the Sx2– dianion caused by individual Li+ cations is represented. Clearly, the Li+ cations pull the electron density of the Sx2– dianion in nearly opposite directions, indicating the presence of anticooperative effect. It is necessary to emphasize that all lowest-lying isomers exhibit a considerable cooperative effect due to the characteristic quadrilateral binding pattern where two Li+ cations are closely arranged and polarize the Sx2– dianion in the same direction, while the anticooperative cases are comparatively much less stable as two Li+ polarize the Sx2– dianion in different directions.

Figure 5.

Electron density difference (EDD) maps representing electron density variations (polarizations) within the Sx2– fragment induced by an individual Li+ cation for isomers (a) 7-29, (b) 8-37, and (c) 6-13 (the red color means a gain of electron density, while the blue color represents a loss of electron density with the isovalue of 0.001 e Å–3 selected).

4. Conclusions

Low-lying isomers of lithium polysulfide clusters Li2Sx (x = 4–8) were thoroughly searched, and the characteristic ring-like geometries with a quadrilateral binding pattern were observed in all lowest-lying isomers. The Li···S interactions in the most stable isomers were studied and found to be ionic. Electrostatic interaction also rules the weakening of Li···S interactions as the size of cluster grows, as the negative charges on the terminal sulfur atoms of the Sx2– fragment decrease with x increasing.

Key factors for the conformational preferences were explored by examining the contributions of individual energy components to the relative stabilities with references to the most stable isomers. Polarization stabilization governs the relative stabilities of most low-lying isomers (58/90), with the deformation energy playing the second-most important role. Pauli exchange repulsion, charge transfer, and total electron correlation barely contribute to the relative stabilities. Notably, the electrostatic interaction, which dominates the binding energies of all low-lying isomers, contributes favorably to the relative stability in most cases (65/90). The Li···Li distance is a crucial geometrical parameter determining the strength of the polarization interaction, which rules the conformational preferences. A close arrangement of two Li+ results in an enhanced resultant electric field, which polarizes the dianion Sx2–. This cooperativity effect between two cations was quantitatively verified, and the strength of the polarization was primarily determined by its cooperative component, which exhibited a linear correlation with the polarization energy. We also investigated the cases with the anticooperative effect, which results from the long separation of two Li+ cations, which polarize the dianion Sx2– in nearly opposite directions. In summary, the conformational preference of Li2Sx (x = 4–8) clusters mainly originates from the cooperative effect of the polarization interaction, which is strengthened by the closely located Li+ cations within the quadrilateral binding region of the ring-like geometries.

Acknowledgments

C.W. acknowledges the support from the Natural Science Foundation of China (no. 22073060). S.Y. acknowledges the support from the Natural Science Foundation of China (no. 22273054). This work was performed in part at the Joint School of Nanoscience and Nanoengineering, a member of the National Nanotechnology Coordinated Infrastructure (NNCI), which is supported by the National Science Foundation (grant ECCS-2025462).

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acs.inorgchem.3c04537.

Relative binding energies of Li2S4 with various basis sets and the M06-2X-D3 functional, correlations between the relative values of Gibbs free energies and binding energies for all low-lying isomers of Li2Sx and their geometries (x = 4–8), natural charges of S and polarizabilities of the Sx2– fragment in the lowest-lying isomers of Li2Sx, BLW-ED results of all low-lying isomers, and Cartesian coordinates of optimal structures studied in this work (PDF)

Author Contributions

X.P.: visualization, investigation, and review and editing. J.L.: visualization and investigation. J.D.: resources. S.Y.: resources. H.Z.: resources. C.W.: supervision, conceptualization, writing of the original draft, and review and editing. Y.M.: supervision, methodology, and review and editing.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Diao Y.; Xie K.; Xiong S.; Hong X. Shuttle phenomenon — The irreversible oxidation mechanism of sulfur active material in Li-S battery. J. Power Sources 2013, 235, 181–186. 10.1016/j.jpowsour.2013.01.132. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Manthiram A.; Fu Y.; Chung S.-H.; Zu C.; Su Y.-S. Rechargeable Lithium-Sulfur Batteries. Chem. Rev. 2014, 114 (23), 11751–11787. 10.1021/cr500062v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao E.; Nie K.; Yu X.; Hu Y.; Wang F.; Xiao J.; Li H.; Huang X. Advanced Characterization Techniques in Promoting Mechanism Understanding for Lithium-Sulfur Batteries. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2018, 28 (38), 1707543. 10.1002/adfm.201707543. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Steudel R.; Chivers T. The role of polysulfide dianions and radical anions in the chemical, physical and biological sciences, including sulfur-based batteries. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2019, 48 (12), 3279–3319. 10.1039/C8CS00826D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raza H.; Bai S.; Cheng J.; Majumder S.; Zhu H.; Liu Q.; Zheng G.; Li X.; Chen G. Li-S Batteries: Challenges, Achievements and Opportunities. Electrochem. Energy Rev. 2023, 6 (1), 29. 10.1007/s41918-023-00188-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cao G.; Duan R.; Li X. Controllable catalysis behavior for high performance lithium sulfur batteries: From kinetics to strategies. EnergyChem. 2023, 5 (1), 100096 10.1016/j.enchem.2022.100096. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ji L.; Rao M.; Zheng H.; Zhang L.; Li Y.; Duan W.; Guo J.; Cairns E. J.; Zhang Y. Graphene Oxide as a Sulfur Immobilizer in High Performance Lithium/Sulfur Cells. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133 (46), 18522–18525. 10.1021/ja206955k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y.; Zheng G.; Cui Y. Nanostructured sulfur cathodes. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2013, 42 (7), 3018–3032. 10.1039/c2cs35256g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin Y.-X.; Xin S.; Guo Y.-G.; Wan L.-J. Lithium-Sulfur Batteries: Electrochemistry, Materials, and Prospects. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2013, 52 (50), 13186–13200. 10.1002/anie.201304762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seh Z. W.; Sun Y.; Zhang Q.; Cui Y. Designing high-energy lithium-sulfur batteries. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2016, 45 (20), 5605–5634. 10.1039/C5CS00410A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng H.; Huang J.; Cheng X.; Zhang Q. Review on High-Loading and High-Energy Lithium-Sulfur Batteries. Adv. Energy Mater. 2017, 7 (24), 1700260. 10.1002/aenm.201700260. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X.; Hou T.; Persson K. A.; Zhang Q. Combining theory and experiment in lithium-sulfur batteries: Current progress and future perspectives. Mater. Today 2019, 22, 142–158. 10.1016/j.mattod.2018.04.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J.; Lee D.-J.; Jung H.-G.; Sun Y.-K.; Hassoun J.; Scrosati B. An Advanced Lithium-Sulfur Battery. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2013, 23 (8), 1076–1080. 10.1002/adfm.201200689. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Manthiram A.; Fu Y.; Su Y.-S. Challenges and Prospects of Lithium-Sulfur Batteries. Acc. Chem. Res. 2013, 46 (5), 1125–1134. 10.1021/ar300179v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song M.-K.; Cairns E. J.; Zhang Y. Lithium/sulfur batteries with high specific energy: old challenges and new opportunities. Nanoscale 2013, 5 (6), 2186–2204. 10.1039/c2nr33044j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y.; Zheng G.; Cui Y. A membrane-free lithium/polysulfide semi-liquid battery for large-scale energy storage. Energy Environ. Sci. 2013, 6 (5), 1552–1558. 10.1039/c3ee00072a. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ryu H. S.; Guo Z.; Ahn H. J.; Cho G. B.; Liu H. Investigation of discharge reaction mechanism of lithium|liquid electrolyte|sulfur battery. J. Power Sources 2009, 189 (2), 1179–1183. 10.1016/j.jpowsour.2008.12.073. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ji X.; Nazar L. F. Advances in Li-S batteries. J. Mater. Chem. 2010, 20 (44), 9821–9826. 10.1039/b925751a. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bruce P. G.; Freunberger S. A.; Hardwick L. J.; Tarascon J.-M. Li-O2 and Li-S batteries with high energy storage. Nat. Mater. 2012, 11 (1), 19–29. 10.1038/nmat3191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miao L.; Wang W.; Wang M.; Duan B.; Wang A. Sulfur Composite Cathode for Lithium-Sulfur Batteries. Prog. Chem. 2013, 25 (11), 1867–1875. 10.7536/PC130310. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ji Z.; Han B.; Li Q.; Zhou C.; Gao Q.; Xia K.; Wu J. Anchoring Lithium Polysulfides via Affinitive Interactions: Electrostatic Attraction, Hydrogen Bonding, or in Parallel?. J. Phys. Chem. C 2015, 119 (35), 20495–20502. 10.1021/acs.jpcc.5b06373. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cheviri M.; Lakshmipathi S. DFT study of chemical reactivity parameters of lithium polysulfide molecules Li2Sn (1 ≤ n ≤ 8) in gas and solvent phase. Computational and Theoretical Chemistry 2021, 1202, 113323 10.1016/j.comptc.2021.113323. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hagen M.; Schiffels P.; Hammer M.; Dörfler S.; Tübke J.; Hoffmann M. J.; Althues H.; Kaskel S. In-Situ Raman Investigation of Polysulfide Formation in Li-S Cells. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2013, 160 (8), A1205. 10.1149/2.045308jes. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pascal T. A.; Wujcik K. H.; Velasco-Velez J.; Wu C.; Teran A. A.; Kapilashrami M.; Cabana J.; Guo J.; Salmeron M.; Balsara N.; Prendergast D. X-ray Absorption Spectra of Dissolved Polysulfides in Lithium-Sulfur Batteries from First-Principles. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2014, 5 (9), 1547–1551. 10.1021/jz500260s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vijayakumar M.; Govind N.; Walter E.; Burton S. D.; Shukla A.; Devaraj A.; Xiao J.; Liu J.; Wang C.; Karim A.; Thevuthasan S. Molecular structure and stability of dissolved lithium polysulfide species. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2014, 16 (22), 10923–10932. 10.1039/C4CP00889H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo Q.; Lau K. C.; Pandey R. A XANES study of lithium polysulfide solids: a first-principles study. Materials Advances 2021, 2 (19), 6403–6410. 10.1039/D1MA00450F. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Long Z.-C.; Wei Z.-Y.; Liu K.-W.; Li X.-L.; Xu X.-L.; Xu H.-G.; Zheng W.-J. Structures and bonding properties of lithium polysulfide clusters LiSn–/0 (n = 3–5) and Li2S4–/0: size-selected anion photoelectron spectroscopy and theoretical calculations. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2023, 25 (15), 10495–10503. 10.1039/D2CP06061B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Q.; Wang Y.; Seh Z. W.; Fu Z.; Zhang R.; Cui Y. Understanding the Anchoring Effect of Two-Dimensional Layered Materials for Lithium-Sulfur Batteries. Nano Lett. 2015, 15 (6), 3780–3786. 10.1021/acs.nanolett.5b00367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao D.; Wang Y.; Zhang L.; Yao S.; Qian X.; Xi X.; Xiao K.; Deng K.; Shen X.; Lu R. Mechanism of polysulfide immobilization on defective graphene sheets with N-substitution. Carbon 2016, 110, 207–214. 10.1016/j.carbon.2016.09.021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Q.; Mu D.; Wu B.; Wang L.; Gai L.; Wu F. Insight on lithium polysulfide intermediates in a Li/S battery by density functional theory. RSC Adv. 2017, 7 (53), 33373–33377. 10.1039/C7RA04673A. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L.; Zhang T.; Yang S.; Cheng F.; Liang J.; Chen J. A quantum-chemical study on the discharge reaction mechanism of lithium-sulfur batteries. Journal of Energy Chemistry 2013, 22 (1), 72–77. 10.1016/S2095-4956(13)60009-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tsuzuki S.; Kaneko T.; Sodeyama K.; Umebayashi Y.; Shinoda W.; Seki S.; Ueno K.; Dokko K.; Watanabe M. Thermodynamic aspect of sulfur, polysulfide anion and lithium polysulfide: plausible reaction path during discharge of lithium-sulfur battery. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2021, 23 (11), 6832–6840. 10.1039/D0CP04898D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao H.; Peng Z.; Wang W.; Chen X.; Fang J.; Xu J. Reduced graphene oxide with ultrahigh conductivity as carbon coating layer for high performance sulfur@reduced graphene oxide cathode. J. Power Sources 2014, 245, 529–536. 10.1016/j.jpowsour.2013.07.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Braga D.; Bazzi C.; Grepioni F.; Novoa J. J. Electrostatic compression on non-covalent interactions: the case of π stacks involving ions. New J. Chem. 1999, 23 (6), 577–579. 10.1039/a901691k. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mahadevi A. S.; Sastry G. N. Cooperativity in Noncovalent Interactions. Chem. Rev. 2016, 116 (5), 2775–2825. 10.1021/cr500344e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berghof V.; Sommerfeld T.; Cederbaum L. S. Sulfur Cluster Dianions. J. Phys. Chem. A 1998, 102 (26), 5100–5105. 10.1021/jp9808375. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- El Jaroudi O.; Picquenard E.; Demortier A.; Lelieur J. P.; Corset J. 1. Structure and Vibrational Spectra of the S22- and S32- Anions. Influence of the Cations on Bond Length and Angle. Inorg. Chem. 1999, 38 (10), 2394–2401. 10.1021/ic9811143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El Jaroudi O.; Picquenard E.; Demortier A.; Lelieur J.-P.; Corset J. Polysulfide Anions II: Structure and Vibrational Spectra of the S42- and S52- Anions. Influence of the Cations on Bond Length, Valence, and Torsion Angle. Inorg. Chem. 2000, 39 (12), 2593–2603. 10.1021/ic991419x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steudel R.; Steudel Y. Polysulfide Chemistry in Sodium-Sulfur Batteries and Related Systems — A Computational Study by G3X(MP2) and PCM Calculations. Chem. - Eur. J. 2013, 19 (9), 3162–3176. 10.1002/chem.201203397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu T.; Li F.; Liu C.; Zhang S.; Xu H.; Yang G. Understanding the role of lithium sulfide clusters in lithium-sulfur batteries. Journal of Materials Chemistry A 2017, 5 (19), 9293–9298. 10.1039/C7TA01006K. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y.; Lv J.; Zhu L.; Ma Y. Crystal structure prediction via particle-swarm optimization. Phys. Rev. B 2010, 82 (9), 094116 10.1103/PhysRevB.82.094116. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lv J.; Wang Y.; Zhu L.; Ma Y. Particle-swarm structure prediction on clusters. J. Chem. Phys. 2012, 137 (8), 084104 10.1063/1.4746757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y.; Lv J.; Zhu L.; Ma Y. CALYPSO: A method for crystal structure prediction. Comput. Phys. Commun. 2012, 183 (10), 2063–2070. 10.1016/j.cpc.2012.05.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lv J.; Wang Y.; Zhu L.; Ma Y. B38: an all-boron fullerene analogue. Nanoscale 2014, 6 (20), 11692–11696. 10.1039/C4NR01846J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lv J.; Wang Y.; Zhang L.; Lin H.; Zhao J.; Ma Y. Stabilization of fullerene-like boron cages by transition metal encapsulation. Nanoscale 2015, 7 (23), 10482–10489. 10.1039/C5NR01659B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng Z.; Kim C.; Vijh A.; Armand M.; Bevan K. H.; Zaghib K. Unravelling the role of Li2S2 in lithium–sulfur batteries: A first principles study of its energetic and electronic properties. J. Power Sources 2014, 272, 518–521. 10.1016/j.jpowsour.2014.07.078. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yang G.; Shi S.; Yang J.; Ma Y. Insight into the role of Li2S2 in Li-S batteries: a first-principles study. Journal of Materials Chemistry A 2015, 3 (16), 8865–8869. 10.1039/C5TA00499C. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bogdan T. V.; Wales D. J.; Calvo F. Equilibrium thermodynamics from basin-sampling. J. Chem. Phys. 2006, 124 (4), 044102 10.1063/1.2148958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glass C. W.; Oganov A. R.; Hansen N. USPEX—Evolutionary crystal structure prediction. Comput. Phys. Commun. 2006, 175 (11), 713–720. 10.1016/j.cpc.2006.07.020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schön J. C. Nanomaterials - what energy landscapes can tell us. Processing and Application of Ceramics 2015, 9 (3), 157–168. 10.2298/PAC1503157S. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dieterich J. M.; Hartke B. Error-Safe, Portable, and Efficient Evolutionary Algorithms Implementation with High Scalability. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2016, 12 (10), 5226–5233. 10.1021/acs.jctc.6b00716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hjorth Larsen A.; Jørgen Mortensen J.; Blomqvist J.; Castelli I. E.; Christensen R.; Dułak M.; Friis J.; Groves M. N.; Hammer B.; Hargus C.; Hermes E. D.; Jennings P. C.; Bjerre Jensen P.; Kermode J.; Kitchin J. R.; Leonhard Kolsbjerg E.; Kubal J.; Kaasbjerg K.; Lysgaard S.; Bergmann Maronsson J.; Maxson T.; Olsen T.; Pastewka L.; Peterson A.; Rostgaard C.; Schiøtz J.; Schütt O.; Strange M.; Thygesen K. S.; Vegge T.; Vilhelmsen L.; Walter M.; Zeng Z.; Jacobsen K. W. The atomic simulation environment—a Python library for working with atoms. J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 2017, 29 (27), 273002. 10.1088/1361-648X/aa680e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J.; Dolg M. ABCluster: the artificial bee colony algorithm for cluster global optimization. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2015, 17 (37), 24173–24181. 10.1039/C5CP04060D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J.; Dolg M. Global optimization of clusters of rigid molecules using the artificial bee colony algorithm. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2016, 18 (4), 3003–3010. 10.1039/C5CP06313B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karaboga D.An Idea Based on Honey Bee Swarm for Numerical Optimization; Department of Computer Engineering, Engineering Faculty, Erciyes University., 01/01, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Bader R. F. W. Atoms in molecules. Acc. Chem. Res. 1985, 18 (1), 9–15. 10.1021/ar00109a003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Reed A. E.; Curtiss L. A.; Weinhold F. Intermolecular interactions from a natural bond orbital, donor-acceptor viewpoint. Chem. Rev. 1988, 88 (6), 899–926. 10.1021/cr00088a005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bader R. F. W.Atoms in Molecules: A Quantum Theory. Oxford University Press: 1995; Vol. 22. [Google Scholar]

- Cremer D.; Wu A.; Larsson A.; Kraka E. Some Thoughts about Bond Energies, Bond Lengths, and Force Constants. J. Mol. Model. 2000, 6 (4), 396–412. 10.1007/PL00010739. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sinnokrot M. O.; Sherrill C. D. Substituent Effects in π–π Interactions: Sandwich and T-Shaped Configurations. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004, 126 (24), 7690–7697. 10.1021/ja049434a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson E. R.; Keinan S.; Mori-Sánchez P.; Contreras-García J.; Cohen A. J.; Yang W. Revealing Noncovalent Interactions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132 (18), 6498–6506. 10.1021/ja100936w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherrill C. D. Energy Component Analysis of π Interactions. Acc. Chem. Res. 2013, 46 (4), 1020–1028. 10.1021/ar3001124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu P.; Chaudret R.; Hu X.; Yang W. Noncovalent Interaction Analysis in Fluctuating Environments. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2013, 9 (5), 2226–2234. 10.1021/ct4001087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mao Y.; Horn P. R.; Head-Gordon M. Energy decomposition analysis in an adiabatic picture. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2017, 19 (8), 5944–5958. 10.1039/C6CP08039A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glendening E. D.; Wright S. J.; Weinhold F. Efficient optimization of natural resonance theory weightings and bond orders by gram-based convex programming. J. Comput. Chem. 2019, 40 (23), 2028–2035. 10.1002/jcc.25855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su P.; Tang Z.; Wu W. Generalized Kohn-Sham energy decomposition analysis and its applications. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev.: Comput. Mol. Sci. 2020, 10 (5), e1460 10.1002/wcms.1460. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tang Z.; Song Y.; Zhang S.; Wang W.; Xu Y.; Wu D.; Wu W.; Su P. XEDA, a fast and multipurpose energy decomposition analysis program. J. Comput. Chem. 2021, 42 (32), 2341–2351. 10.1002/jcc.26765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraka E.; Quintano M.; La Force H. W.; Antonio J. J.; Freindorf M. The Local Vibrational Mode Theory and Its Place in the Vibrational Spectroscopy Arena. J. Phys. Chem. A 2022, 126 (47), 8781–8798. 10.1021/acs.jpca.2c05962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu W.; Su P.; Shaik S.; Hiberty P. C. Classical Valence Bond Approach by Modern Methods. Chem. Rev. 2011, 111 (11), 7557–7593. 10.1021/cr100228r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Z.; Wu W. Ab initio valence bond theory: A brief history, recent developments, and near future. J. Chem. Phys. 2020, 153 (9), 090902 10.1063/5.0019480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mo Y.; Peyerimhoff S. D. Theoretical analysis of electronic delocalization. J. Chem. Phys. 1998, 109 (5), 1687–1697. 10.1063/1.476742. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mo Y.; Song L.; Wu W.; Cao Z.; Zhang Q. Electronic delocalization: A quantitative study from modern ab initio valence bond theory. J. Theor. Comput. Chem. 2002, 1 (1), 137–151. 10.1142/S0219633602000099. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mo Y. Geometrical optimization for strictly localized structures. J. Chem. Phys. 2003, 119 (3), 1300–1306. 10.1063/1.1580094. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mo Y.; Song L.; Lin Y. Block-localized wavefunction (BLW) method at the density functional theory (DFT) level. J. Phys. Chem. A 2007, 111 (34), 8291–8301. 10.1021/jp0724065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mo Y.; Gao J.; Peyerimhoff S. D. Energy decomposition analysis of intermolecular interactions using a block-localized wave function approach. J. Chem. Phys. 2000, 112 (13), 5530–5538. 10.1063/1.481185. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mo Y.; Bao P.; Gao J. Energy decomposition analysis based on a block-localized wavefunction and multistate density functional theory. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2011, 13 (15), 6760–6775. 10.1039/c0cp02206c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mo Y., The Block-Localized Wavefunction (BLW) Perspective of Chemical Bonding. In The Chemical Bond; Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA; 2014; pp 199–232.

- Wang C.; Danovich D.; Shaik S.; Mo Y. Halogen Bonds in Novel Polyhalogen Monoanions. Chem. - Eur. J. 2017, 23 (36), 8719–8728. 10.1002/chem.201701116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang C.; Aman Y.; Ji X.; Mo Y. Tetrel bonding interaction: an analysis with the block-localized wavefunction (BLW) approach. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2019, 21 (22), 11776–11784. 10.1039/C9CP01710K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L.; Dang J.; Du J.; Wang C.; Mo Y. Hydrogen and Halogen Bonding in Homogeneous External Electric Fields: Modulating the Bond Strengths. Chem. - Eur. J. 2021, 27 (56), 14042–14050. 10.1002/chem.202102284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan D.; Chen L.; Wang C.; Yin S.; Mo Y. Inter-anion chalcogen bonds: Are they anti-electrostatic in nature?. J. Comput. Chem. 2021, 155 (23), 234302. 10.1063/5.0076872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J.; Feng Q.; Wang C.; Mo Y. On the nature of inter-anion coinage bonds. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2023, 25 (22), 15371–15381. 10.1039/D3CP00978E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weigend F.; Ahlrichs R. Balanced basis sets of split valence, triple zeta valence and quadruple zeta valence quality for H to Rn: Design and assessment of accuracy. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2005, 7 (18), 3297–3305. 10.1039/b508541a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Y.; Truhlar D. G. The M06 suite of density functionals for main group thermochemistry, thermochemical kinetics, noncovalent interactions, excited states, and transition elements: two new functionals and systematic testing of four M06-class functionals and 12 other functionals. Theor. Chem. Acc. 2008, 120 (1), 215–241. 10.1007/s00214-007-0310-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Grimme S.; Antony J.; Ehrlich S.; Krieg H. A consistent and accurate ab initio parametrization of density functional dispersion correction (DFT-D) for the 94 elements H-Pu. J. Chem. Phys. 2010, 132 (15), 154104. 10.1063/1.3382344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt M. W.; Baldridge K. K.; Boatz J. A.; Elbert S. T.; Gordon M. S.; Jensen J. H.; Koseki S.; Matsunaga N.; Nguyen K. A.; Su S.; Windus T. L.; Dupuis M.; Montgomery J. A. Jr General atomic and molecular electronic structure system. J. Comput. Chem. 1993, 14 (11), 1347–1363. 10.1002/jcc.540141112. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Humphrey W.; Dalke A.; Schulten K. VMD: Visual molecular dynamics. J. Mol. Graphics 1996, 14 (1), 33–38. 10.1016/0263-7855(96)00018-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu T.; Chen F. Multiwfn: A multifunctional wavefunction analyzer. J. Comput. Chem. 2012, 33 (5), 580–592. 10.1002/jcc.22885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu T.; Chen Q. Independent gradient model based on Hirshfeld partition: A new method for visual study of interactions in chemical systems. J. Comput. Chem. 2022, 43 (8), 539–555. 10.1002/jcc.26812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.