Beige/brown adipocytes play a crucial role in regulating the body's overall energy balance. The thermogenic function is under the influence of various tissues, including the brain, muscles, and liver. However, the breast tissue is not in the list. This issue has been addressed in a study recently published in Nature, which identified the paracrine function of breast epithelial cells for secreting “lipocalin 2” in the inhibition of thermogenesis of beige adipocytes to reserve mammary gland white adipose tissue (mgWAT)1. Within the female mammary gland, milk is produced by epithelial cells that form the glandular ducts and lobules in the adipose tissue and connective tissue within the breast2. The gland's structure is anatomically divided into four compartments: terminal ductal lobular units and branching epithelial cells in the lobules, primarily bilayered epithelium in the ducts, connective tissue rich in extracellular matrix, and adipose-rich areas3. While the exocrine function of epithelial cells is well-known in milk secretion, their paracrine/endocrine function was largely unexplored. The new study revealed that these epithelial cells have a paracrine function in secreting lipocalin 2, referred to as “mammokine”.

There are three types of adipocytes: white, brown, and beige adipocytes4. White adipocytes are the major cell type in white adipose tissue (WAT) with functions in energy storage and adipokine secretion. WAT is predominantly found in various regions of the body, including the breast and subcutaneous5. In the breast, white adipocytes provide lipids supply to epithelial cells in production of the fatty acid portion of milk at about 3.5% by weight. In contrast, brown adipocytes are the major cell types in brown adipose tissue (BAT) with a primary function in thermogenesis, providing heat in the maintenance of body temperature6. This type of cells is characterized by abundant mitochondria and a high expression of uncoupling protein-1 (UCP-1). UCP-1 uncouples oxidative phosphorylation from ATP synthesis leading to the heat production for non-shivering thermogenesis7. Beige adipocytes distribute in subcutaneous WAT (scWAT) in mice, share similarities with brown adipocytes in thermogenesis. Beige function is induced by factors such as exercise, cold exposure, PPARγ activation, and β-adrenergic receptor agonists, which promote generation of beige cells from preadipocytes or mature adipocytes, known as WAT browning. Under conditions of warmth and high-fat diet feeding, beige cells are degenerated into white adipocytes, known as beige adipocyte whitening, decreasing the thermogenic activity of scWAT8,9. The WAT browning is considered a potential therapeutic approach for obesity and diabetes10. The impact of epithelial cells in beige adipocytes had not been previously explored in female breast.

The breasts contain a large portion of white adipose tissue to support milk production in the epithelial cells11,12. The adipocytes interact with the ductal epithelial cells, particularly during pregnancy, lactation, and involution13,14. The adipocytes also play a role in controlling ductal morphogenesis, cell differentiation, and function maturation of ductal epithelial cells through the interaction13,15. In breast cancer, the adipose tissue is reprogrammed by epithelial tumor cells to express more inflammatory cytokines supporting tumor growth as shown in a recent study using single-nuclear RNA sequencing (snRNA-seq) technology by our group16. The study indicates a crosstalk between adipocytes and epithelial cells in breast cancer, but the paracrine function of epithelial cells remains to be explored in breast.

In another recent study, Kumar et al. reported a comprehensive Human Breast Cell Atlas (HBCA) using multiple advanced technologies including single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq), snRNA-seq and spatial RNA sequencing technologies17. They identified 12 primary cell types and 58 cell states, revealing a high degree of diversity among luminal epithelial cells. There are three subtypes of epithelial cells, basal, luminal secretory (LumSec), and luminal hormone-responsive (LumHR), constitute the majority of breast ductal tissue. Additionally, they observed diversity in cellular states within these subsets. The basal epithelial cells were notably homogeneous, whereas the LumHR epithelial cells contained three different states, and LumSec epithelial cells displayed seven different states. They employed four different technologies to obtain spatial information of the subsets, providing valuable insights into breast biology and breast cancer. Notably, the subsets, including LumSec-basal, LumSec-HLA ductal basal colonization, LumSec-KIT, and LumSec-major basal lobular colonization, exhibited location-specific patterns. Unlike previous findings, LumHR and LumSec cells were not limited to alveoli and ducts as they presented in both ducts and lobular alveoli with varying abundance. The study identified a significant decrease in epithelial cell types in the breasts of postmenopausal women, with an increase in fibroblasts and myeloid cells in obese individuals17. They examined brown/beige adipocytes in the adipose tissue of breast. The conclusion is that the breast adipocytes were exclusively white adipocytes17. Despite the excellent work in construction of comprehensive and unbiased cellular map of breast tissue, the functional interactions between epithelial cells and adipocytes were not investigated in the study.

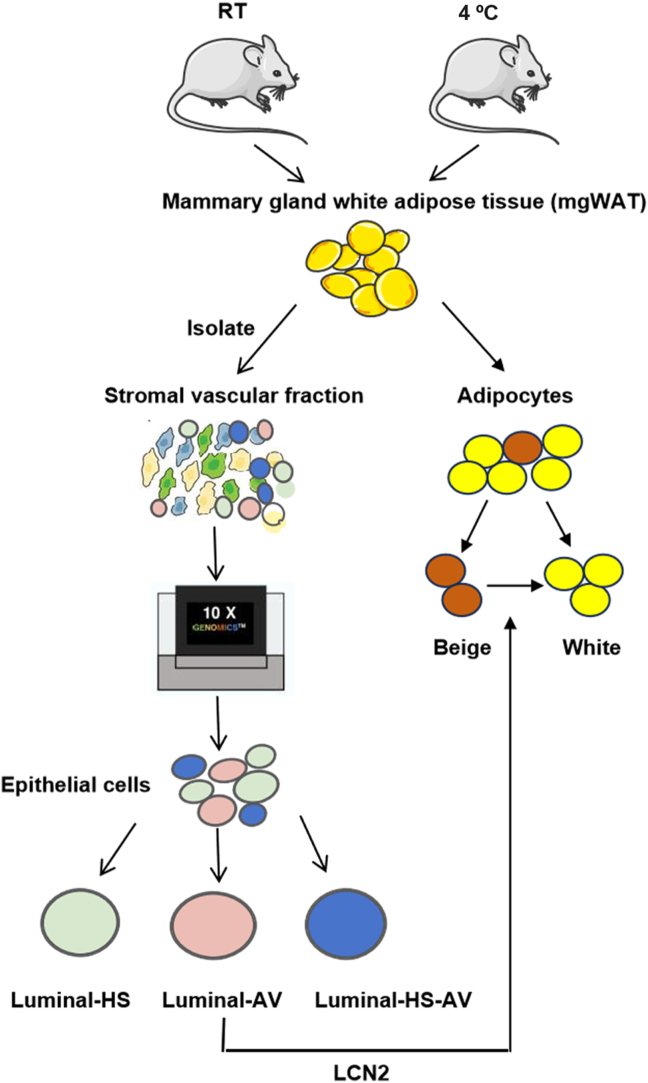

To this point, Patel et al.1 investigated the interaction of epithelial cells and adipocytes in mice, and obtained similar patterns of cell subsets to those by Kumar et al.17 They divided luminal cells into three subclusters, including luminal-hormone sensing (Luminal-HS), luminal-alveolar (Luminal-AV), luminal-hormone sensing alveolar (Luminal-HS-AV). Luminal-HS from Patel et al.‘s studies and LumHR from Kumar et al.‘s studies are hormone-sensing cells with high expression of hormone receptors, such as Pgr, Esr1 and Prlr18. The Luminal-AV subsets specifically express luminal progenitor markers (Cd14) and milk biosynthesis-related genes (Mfge8). The Luminal–HS–AV subsets co-express hormone-sensing markers and alveolar progenitor markers, which is consistent with observations in other studies18,19. While the LumSec subsets express genes associated with milk production and secretory molecules with distinct expression of epithelial keratin20, 21, 22.

More importantly, they identified a subtype of glandular luminal epithelium in female mice that secretes “mammokine” to regulate beige function of breast adipose tissue1. Using scRNA-seq technology, they analyzed cell types and cell subsets in the breast tissue. They demonstrated that mammary ducts could reduce UCP1 expression in breast adipocytes through secretion of mammokine, lipocalin 2 (LCN2). To confirm the activity, they employed Lcn2 gene knockout mice and found that LCN2 inhibited the beige cell function in female-specific manner. In the female Lcn2-KO mice, the inhibition was removed by Lcn gene inactivation leading to elevation of energy expenditure, which was responsible for a significant decrease in body weight and subcutaneous fat under a cold environment. The effect was not observed in the wild-type controls and male Lcn2-KO mice. Expression of LCN2 was induced by cold stimulation and restricted to the luminal epithelium. The impact of the mammokine may extends beyond breast adipocytes to subcutaneous fat in other fat pads. Importantly, this effect was observed only in the female mice, suggesting that mammokine activity is sex-specific in regulation of adipose thermogenesis. The mammary-derived factor, secreted by ductal epithelial cells, preserves energy in the female body for breast development and milk production. In breast cancer, the interaction forces adipocytes to supply essential nutrients, energy, and growth factors to epithelial tumor cells to meet the metabolic demands of tumor23.

The LCN2 activity remains controversial in adipocyte thermogenesis. There are several studies on LCN2 regulation of adipose thermogenesis24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30. One group of studies suggested that Lcn2 was required for BAT thermogenesis and beiging activity of inguinal white adipose tissue (iWAT). They found that LCN2 deficiency significantly suppressed thermogenesis of adipose tissue in mice. In the mechanism of LCN2 activity, LCN2 was found to act via the COX2-PGs-mTOR pathway in adipocytes as LCN2 deficiency suppressed the mTOR signaling in control of thermogenic gene expression, lipogenesis, and lipolysis24, 25, 26. Furthermore, LCN2 was reported to regulate metabolic homeostasis of retinoids and retinoid-mediated thermogenesis in adipose tissue27, 28, 29, 30. These studies demonstrated that LCN2 promotes thermogenesis of brown/beige adipocytes. However, another group of studies suggest that LCN2 represses the function of brown/beige adipocytes. Ishii et al. showed that the Lcn2-KO mice had enhanced non-shivering thermogenesis when exposed to 4 °C as indicated by higher body temperature and larger size of BATs, indicating that LCN2 inhibits function of BATs31. Lemecha et al.32 observed that Lcn2 gene deficiency significantly improved BAT function as indicated by body temperature in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC)-bearing mice and increased expression of Ucp1 and β3-adrenergic receptor in BAT. Park et al. found that LCN2 inhibited BAT function in dietary obese mice, and calorie restriction enhanced BAT function in the obese mice by suppression of LCN2 expression, which led to a reduction in inflammation, oxidative stress, and mitochondrial fission in BAT33. The two groups of reports suggest that LCN2 activity in adipocytes deserves more studies on thermogenesis.

The controversial may be explained by the sex-specific activity of LCN2. Previous studies of LCN2 in vivo were mainly conducted in male mice. In a study by Krishman et al.34, LCN2 expression pattern and phenotypes were examined in both males and females in a panel of 100 inbred strains of mice (HMDP). They found that LCN2 overexpression in the adipose tissue induced metabolic disorders via an autocrine/paracrine manner through induction of inflammation and fibrosis in females, but not in males. While, LCN2 overexpression in the liver failed to generate the metabolic effect, suggesting a tissue-specific effect of LCN2. Lcn2 gene transcription is regulated by estrogen through estrogen receptor Erα, which represses Lcn2 gene expression by binding to the promoter DNA35,36, suggesting a mechanism of sex-specific regulation of Lcn2 gene. The study suggests that LCN2 level is lower in the female body as a result of suppressed transcription by the estrogen receptor. The conclusion by Krishman et al. is consistent with that of Patel et al. on the sex-specific activity of LCN-2 in the inhibition of thermogenic function of adipose tissue.

There is a sex difference in beige function in fat pad-specific manner as reported in several studies37, 38, 39, 40, 41. It is generally believed that WAT browning occurs frequently in subcutaneous fat, instead of gonadal WAT (gWAT) depots as shown in most studies42. However, this feature may apply only to male mice, but not to female mice. In the female mice, WAT browning was more active in gWAT of female mice than that of male mice as reported in a study by Kim et al. in the model of β3-adrenergic stimulation41. Additionally, WAT browning was more active in gWAT than iWAT in the female mice41. These results are consistent with in vitro experiments conducted by Beukel et al.43 using human perirenal tissues, suggesting that WAT browning has a gender difference and fat pad-specificity.

In addition to LCN2, other “mammokine” were identified in the luminal epithelial cells in the study1. Expression of those secreted factors was up-regulated in the epithelial cells by the cold treatments. Activities of those mammokine were not examined in the study, but their activities are indicated in other studies. For example, Angiopoietin-like 4 (ANGPTL4) increases circulating triglyceride levels and regulated lipid distribution across different tissues by inhibiting lipoprotein lipase activity. As such, ANGPTL4 has been considered as a potential therapeutic target44,45. Leucine-rich α-2 glycoprotein 1 (LRG1) is an adipokine secreted by mature adipocytes and LRG1 overexpression enhanced insulin sensitivity and suppressed inflammation46. Diacylglycerol acyltransferase 2 (DGAT2) regulates triacylglycerol (TG) synthesis of de novo-synthesized fatty acids and is the predominant enzyme for TG storage47. Adropin (Enho) modulates glucose and lipid metabolism48. Patel et al.1 reported that the adropin and LRG1 secreted by luminal cells may not make an impact in adipose thermogenesis directly as they may change other metabolic functions of mgWAT. These data indicate that liminal epithelial cells regulate the function of breast adipose tissue by secreting multiple mammokines.

While this new study sheds light on the paracrine function of mammary epithelial cells for identification of mammokine LCN2 in the regulation of breast energy expenditure, which involves in beige adipocyte whitening1 (Fig. 1). However, the precise molecular mechanism of LCN2 action remains to be investigated for the whitening1.

Figure 1.

Cold-induced secretion of LCN2 from the luminal epithelial cells leads to beige cell whitening in the female breast. In the new study by Patel et al., the breast adipose tissues were collected from female mice treated with the room temperature (RT) or cold (4 °C) environment, respectively. The cell types and subsets of epithelial cells were investigated using single cell sequencing technology, which led to the finding that LCN2 expression was induced in the epithelial cells by the cold stimulation. The expression was restricted to the subset of luminal-alveolar (Lunimal-AV) of epithelial cells, but not the subset of luminal-hormone sensing (Luminal-HS) or luminal-hormone sensing alveolar (Luminal–HS–AV) epithelial cells. LCN2 was found to act on the beige adipocytes to reduce the thermogenesis activities leading to beige adipocyte whitening in the breast, which likely leads to reservation of energy for milk production in the breast.

Author contributions

Lina Tang made the draft and revised the manuscript. Jianping Ye provided the idea and revised the manuscript in the original and revised submission.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgment

This study is supported by a project (32271220) from the National Natural Science Foundation of China to Jianping Ye.

Footnotes

Peer review under the responsibility of Chinese Pharmaceutical Association and Institute of Materia Medica, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences.

References

- 1.Patel S., Sparman N.Z.R., Arneson D., Alvarsson A., Santos L.C., Duesman S.J., et al. Mammary duct luminal epithelium controls adipocyte thermogenic programme. Nature. 2023;620:192–199. doi: 10.1038/s41586-023-06361-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alex A., Bhandary E., McGuire K.P. Anatomy and physiology of the breast during pregnancy and lactation. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2020;1252:3–7. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-41596-9_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Virtanen S., Schulte R., Stingl J., Caldas C., Shehata M. High-throughput surface marker screen on primary human breast tissues reveals further cellular heterogeneity. Breast Cancer Res. 2021;23:66. doi: 10.1186/s13058-021-01444-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yang Loureiro Z., Solivan-Rivera J., Corvera S. Adipocyte heterogeneity underlying adipose tissue functions. Endocrinology. 2022;163:bqab138. doi: 10.1210/endocr/bqab138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ghaben A.L., Scherer P.E. Adipogenesis and metabolic health. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2019;20:242–258. doi: 10.1038/s41580-018-0093-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chondronikola M., Volpi E., Borsheim E., Porter C., Saraf M.K., Annamalai P., et al. Brown adipose tissue activation is linked to distinct systemic effects on lipid metabolism in humans. Cell Metabol. 2016;23:1200–1206. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2016.04.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rodriguez A., Ezquerro S., Mendez-Gimenez L., Becerril S., Fruhbeck G. Revisiting the adipocyte: a model for integration of cytokine signaling in the regulation of energy metabolism. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2015;309:E691–E714. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00297.2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kajimura S., Spiegelman B.M., Seale P. Brown and beige fat: physiological roles beyond heat generation. Cell Metabol. 2015;22:546–559. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2015.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Roh H.C., Tsai L.T.Y., Shao M., Tenen D., Shen Y., Kumari M., et al. Warming induces significant reprogramming of beige, but not brown, adipocyte cellular identity. Cell Metabol. 2018;27 doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2018.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang W., Seale P. Control of brown and beige fat development. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2016;17:691–702. doi: 10.1038/nrm.2016.96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wu Y., Li X., Li Q., Cheng C., Zheng L. Adipose tissue-to-breast cancer crosstalk: comprehensive insights. Biochim Biophys Acta Rev Cancer. 2022;1877 doi: 10.1016/j.bbcan.2022.188800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kothari C., Diorio C., Durocher F. The importance of breast adipose tissue in breast cancer. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21:5760. doi: 10.3390/ijms21165760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang Q.A., Scherer P.E. Remodeling of murine mammary adipose tissue during pregnancy, lactation, and involution. J Mammary Gland Biol Neoplasia. 2019;24:207–212. doi: 10.1007/s10911-019-09434-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Inman J.L., Robertson C., Mott J.D., Bissell M.J. Mammary gland development: cell fate specification, stem cells and the microenvironment. Development. 2015;142:1028–1042. doi: 10.1242/dev.087643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang Q.A., Song A., Chen W., Schwalie P.C., Zhang F., Vishvanath L., et al. Reversible de-differentiation of mature white adipocytes into preadipocyte-like precursors during lactation. Cell Metabol. 2018;28 doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2018.05.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tang L., Li T., Xie J., Huo Y., Ye J. Diversity and heterogeneity in human breast cancer adipose tissue revealed at single-nucleus resolution. Front Immunol. 2023;14 doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2023.1158027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kumar T., Nee K., Wei R., He S., Nguyen Q.H., Bai S., et al. A spatially resolved single-cell genomic atlas of the adult human breast. Nature. 2023;620:181–191. doi: 10.1038/s41586-023-06252-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bach K., Pensa S., Grzelak M., Hadfield J., Adams D.J., Marioni J.C., et al. Differentiation dynamics of mammary epithelial cells revealed by single-cell RNA sequencing. Nat Commun. 2017;8:2128. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-02001-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li C.M., Shapiro H., Tsiobikas C., Selfors L.M., Chen H., Rosenbluth J., et al. Aging-associated alterations in mammary epithelia and stroma revealed by single-cell RNA sequencing. Cell Rep. 2020;33 doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2020.108566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gray G.K., Li C.M., Rosenbluth J.M., Selfors L.M., Girnius N., Lin J.R., et al. A human breast atlas integrating single-cell proteomics and transcriptomics. Dev Cell. 2022;57 doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2022.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bhat-Nakshatri P., Gao H., Sheng L., McGuire P.C., Xuei X., Wan J., et al. A single-cell atlas of the healthy breast tissues reveals clinically relevant clusters of breast epithelial cells. Cell Rep Med. 2021;2 doi: 10.1016/j.xcrm.2021.100219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nguyen Q.H., Pervolarakis N., Blake K., Ma D., Davis R.T., James N., et al. Profiling human breast epithelial cells using single cell RNA sequencing identifies cell diversity. Nat Commun. 2018;9:2028. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-04334-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pare M., Darini C.Y., Yao X., Chignon-Sicard B., Rekima S., Lachambre S., et al. Breast cancer mammospheres secrete adrenomedullin to induce lipolysis and browning of adjacent adipocytes. BMC Cancer. 2020;20:784. doi: 10.1186/s12885-020-07273-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Deis J.A., Guo H., Wu Y., Liu C., Bernlohr D.A., Chen X. Lipocalin 2 regulates retinoic acid-induced activation of beige adipocytes. J Mol Endocrinol. 2018;61:115–126. doi: 10.1530/JME-18-0017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Deis J.A., Guo H., Wu Y., Liu C., Bernlohr D.A., Chen X. Adipose Lipocalin 2 overexpression protects against age-related decline in thermogenic function of adipose tissue and metabolic deterioration. Mol Metabol. 2019;24:18–29. doi: 10.1016/j.molmet.2019.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Deis J., Lin T.Y., Bushman T., Chen X. Lipocalin 2 deficiency alters prostaglandin biosynthesis and mTOR signaling regulation of thermogenesis and lipid metabolism in adipocytes. Cells. 2022;11:1535. doi: 10.3390/cells11091535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Guo H., Foncea R., O'Byrne S.M., Jiang H., Zhang Y., Deis J.A., et al. Lipocalin 2, a regulator of retinoid homeostasis and retinoid-mediated thermogenic activation in adipose tissue. J Biol Chem. 2016;291:11216–11229. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.711556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang Y., Guo H., Deis J.A., Mashek M.G., Zhao M., Ariyakumar D., et al. Lipocalin 2 regulates brown fat activation via a nonadrenergic activation mechanism. J Biol Chem. 2014;289:22063–22077. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.559104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Guo H., Bazuine M., Jin D., Huang M.M., Cushman S.W., Chen X. Evidence for the regulatory role of lipocalin 2 in high-fat diet-induced adipose tissue remodeling in male mice. Endocrinology. 2013;154:3525–3538. doi: 10.1210/en.2013-1289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Guo H., Jin D., Zhang Y., Wright W., Bazuine M., Brockman D.A., et al. Lipocalin-2 deficiency impairs thermogenesis and potentiates diet-induced insulin resistance in mice. Diabetes. 2010;59:1376–1385. doi: 10.2337/db09-1735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ishii A., Katsuura G., Imamaki H., Kimura H., Mori K.P., Kuwabara T., et al. Obesity-promoting and anti-thermogenic effects of neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin in mice. Sci Rep. 2017;7 doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-15825-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lemecha M., Chalise J.P., Takamuku Y., Zhang G., Yamakawa T., Larson G., et al. Lcn2 mediates adipocyte-muscle-tumor communication and hypothermia in pancreatic cancer cachexia. Mol Metabol. 2022;66 doi: 10.1016/j.molmet.2022.101612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Park K.A., Jin Z., An H.S., Lee J.Y., Jeong E.A., Choi E.B., et al. Effects of caloric restriction on the expression of lipocalin-2 and its receptor in the brown adipose tissue of high-fat diet-fed mice. Korean J Physiol Pharmacol. 2019;23:335–344. doi: 10.4196/kjpp.2019.23.5.335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chella Krishnan K., Sabir S., Shum M., Meng Y., Acin-Perez R., Lang J.M., et al. Sex-specific metabolic functions of adipose Lipocalin-2. Mol Metabol. 2019;30:30–47. doi: 10.1016/j.molmet.2019.09.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Drew B.G., Hamidi H., Zhou Z., Villanueva C.J., Krum S.A., Calkin A.C., et al. Estrogen receptor (ER)alpha-regulated lipocalin 2 expression in adipose tissue links obesity with breast cancer progression. J Biol Chem. 2015;290:5566–5581. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.606459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Guo H., Zhang Y., Brockman D.A., Hahn W., Bernlohr D.A., Chen X. Lipocalin 2 deficiency alters estradiol production and estrogen receptor signaling in female mice. Endocrinology. 2012;153:1183–1193. doi: 10.1210/en.2011-1642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Norheim F., Hasin-Brumshtein Y., Vergnes L., Chella Krishnan K., Pan C., Seldin M.M., et al. Gene-by-sex interactions in mitochondrial functions and cardio-metabolic traits. Cell Metabol. 2019;29 doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2018.12.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhao L., Wang B., Gomez N.A., de Avila J.M., Zhu M.J., Du M. Even a low dose of tamoxifen profoundly induces adipose tissue browning in female mice. Int J Obes. 2020;44:226–234. doi: 10.1038/s41366-019-0330-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Miao Y.F., Su W., Dai Y.B., Wu W.F., Huang B., Barros R.P., et al. An ERbeta agonist induces browning of subcutaneous abdominal fat pad in obese female mice. Sci Rep. 2016;6 doi: 10.1038/srep38579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Park S., Nayantai E., Komatsu T., Hayashi H., Mori R., Shimokawa I. NPY deficiency prevents postmenopausal adiposity by augmenting estradiol-mediated browning. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2020;75:1042–1049. doi: 10.1093/gerona/gly282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kim S.N., Jung Y.S., Kwon H.J., Seong J.K., Granneman J.G., Lee Y.H. Sex differences in sympathetic innervation and browning of white adipose tissue of mice. Biol Sex Differ. 2016;7:67. doi: 10.1186/s13293-016-0121-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gomez-Garcia I., Trepiana J., Fernandez-Quintela A., Giralt M., Portillo M.P. Sexual dimorphism in brown adipose tissue activation and white adipose tissue browning. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23:8250. doi: 10.3390/ijms23158250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.van den Beukel J.C., Grefhorst A., Hoogduijn M.J., Steenbergen J., Mastroberardino P.G., Dor F.J., et al. Women have more potential to induce browning of perirenal adipose tissue than men. Obesity. 2015;23:1671–1679. doi: 10.1002/oby.21166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fernandez-Hernando C., Suarez Y. ANGPTL4: a multifunctional protein involved in metabolism and vascular homeostasis. Curr Opin Hematol. 2020;27:206–213. doi: 10.1097/MOH.0000000000000580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bini S., D'Erasmo L., Di Costanzo A., Minicocci I., Pecce V., Arca M. The interplay between angiopoietin-like proteins and adipose tissue: another piece of the relationship between adiposopathy and cardiometabolic diseases?. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22:742. doi: 10.3390/ijms22020742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Choi C.H.J., Barr W., Zaman S., Model C., Park A., Koenen M., et al. LRG1 is an adipokine that promotes insulin sensitivity and suppresses inflammation. Elife. 2022;11 doi: 10.7554/eLife.81559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chitraju C., Walther T.C., Farese R.V., Jr. The triglyceride synthesis enzymes DGAT1 and DGAT2 have distinct and overlapping functions in adipocytes. J Lipid Res. 2019;60:1112–1120. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M093112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jasaszwili M., Billert M., Strowski M.Z., Nowak K.W., Skrzypski M. Adropin as a fat-burning hormone with multiple functions-review of a decade of research. Molecules. 2020;25:549. doi: 10.3390/molecules25030549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]