Abstract

The efficacy of DNA vaccines encoding the duck hepatitis B virus (DHBV) pre-S/S and S proteins were tested in Pekin ducks. Plasmid pcDNA I/Amp DNA containing the DHBV pre-S/S or S genes was injected intramuscularly three times, at 3-week intervals. All pre-S/S and S-vaccinated ducks developed total anti-DHBs and specific anti-S antibodies with similar titers reaching 1/10,000 to 1/50,000 and 1/2,500 to 1/4,000, respectively, after the third vaccination. However, following virus challenge, significant differences in the rate of virus removal from the bloodstream and the presence of virus replication in the liver were found between the groups. In three of four S-vaccinated ducks, 90% of the inoculum was removed between <5 and 15 min postchallenge (p.c.) and no virus replication was detected in the liver at 4 days p.c. In contrast, in all four pre-S/S-vaccinated ducks, 90% of the inoculum was removed between 60 and 90 min p.c. and DHBsAg was detected in 10 to 40% of hepatocytes. Anti-S serum abolished virus infectivity when preincubated with DHBV before inoculation into 1-day-old ducklings and primary duck hepatocyte cultures, while anti-pre-S/S serum showed very limited capacity to neutralize virus infectivity in these two systems. Thus, although both DNA vaccines induced high titers of anti-DHBs antibodies, anti-S antibodies induced by the S-DNA construct were highly effective in neutralizing virus infectivity while similar levels of anti-S induced by the pre-S/S-DNA construct conferred only very limited protection. This phenomenon requires further clarification, particularly in light of the development of newer HBV vaccines containing pre-S proteins and a possible discrepancy between anti-HBs titers and protective efficacy.

Hepatitis B virus (HBV) vaccines which contain the small envelope protein (S-HBs) of the virus provide significant protection against HBV infection. Global HBV vaccination programs as recommended by the World Health Organization may eventually reduce the number of HBV carriers, at present estimated to be 350 million people worldwide (21). In natural HBV infection and in HBV vaccine recipients, the presence of antibodies directed to the surface antigen of the viral envelope protein (anti-HBs antibodies) is a marker of immunity. The surface gene of HBV contains a single open reading frame with three in-frame translation start codons that identify the pre-S1, pre-S2, and S genes, which code for the large (L-HBs), middle (M-HBs), and small (S-HBs) proteins, respectively. All three envelope proteins have the same carboxyl terminus but differ in length at their amino terminus. The S-HBs protein, also termed the major surface antigen (HBsAg), carries a group-specific determinant, a, which is common to all subtypes. The a determinant of HBsAg is an immunodominant epitope to which anti-HBs responses following natural infection and vaccination are predominantly directed (37). The antigenicity of the a determinant depends on its conformational structure maintained by disulfide bridges between amino acids 124 and 137 and 139 and 147 (1, 3). Injection of a monoclonal antibody raised against the a determinant of HBsAg (anti-a) into chimpanzees conferred protection against HBV infection (16). Likewise, HBV subunit vaccines (yeast derived) that contain only S-HBs protein confer protection against HBV infection in vaccinees who develop an anti-HBs titer of >10 mIU/ml (15).

Despite the effectiveness of the current HBV vaccine, several problems concerning this vaccine still exist, e.g., nonresponsiveness in 5 to 10% of vaccinees and the emergence of vaccine-escape mutants (3). Therefore, further development of the current HBV vaccines to improve the efficacy of vaccination would be desirable. The benefit of inclusion of the pre-S protein into the current HBV vaccine has not been established, although a preliminary study has demonstrated that incorporation of pre-S protein into the HBV vaccine resulted in seroconversion in a small number of nonresponders to the conventional vaccine (40). Another possible approach is DNA-based vaccination (10, 12), which allows synthesis of a foreign protein(s) in vivo from the injected plasmid DNA. An important feature of this method is that the viral protein(s) enters the major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I pathway of the cell, leading to the induction of cytotoxic T-lymphocyte responses. Theoretically, the presence of plasmid DNA within the transfected cells will allow sustained viral antigen expression in vivo, with prolonged induction of both humoral and cell-mediated immune responses. This type of immune response induced by DNA vaccines mimics that of live attenuated viral vaccines yet avoids some of the possible problems associated with live vaccines. It has been shown that intramuscular (i.m.) injection of plasmid DNA encoding HBsAg in mice (10) and chimpanzees (12) led to the production of anti-HBs antibodies in vivo. However, the protective efficacy of DNA vaccines against HBV infection could be tested only in primates, and hence other animal models such as ducks experimentally infected with duck HBV (DHBV) have been explored.

DHBV is closely related to HBV with regard to genomic organization, hepatotropism, and mode of replication (26). In addition, DHBV in its natural host, the domestic Pekin duck, permits the study of virus neutralization mechanisms both in vitro and in vivo. The envelope proteins of DHBV, the large (pre-S/S) and small (S) surface proteins, have been shown to be involved in viral infectivity and to carry neutralization epitopes. Previous studies have demonstrated several neutralizing epitopes in DHBV envelope proteins, four within the pre-S domain, and one in the S domain (6). Others have also reported that monoclonal antibodies against specific antigenic sites within the pre-S domain (amino acids 77 to 100) were able to reduce DHBV infectivity in vivo (4, 5). The role of DHBV S protein alone in inducing neutralizing antibodies remains uncertain in vivo, although it has been shown that monoclonal antibodies specific for S protein were able to neutralize DHBV infectivity in vitro (6, 28).

Using DHBV as a model for HBV, we report the protective efficacy of DNA vaccines against DHBV infection in ducks. We have used DNA vaccines coding for the DHBV pre-S/S and S proteins to test the hypothesis that current HBV vaccines might be improved by the inclusion of pre-S protein.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Source of the virus and plasmid.

The Australian strain of DHBV (AusDHBV) used throughout this study was isolated from a pool of congenitally DHBV-infected Pekin duck (Anas domesticus platyrhyncos) serum (34). A full-length clone of the AusDHBV genome, pBL 4.8 (34), was obtained by insertion of DHBV genome at the EcoRI site of pBluescript 11KS+ (Stratagene). pBL 4.8 was used as the DNA template for subcloning by PCR (see below) and as a DNA probe for Southern blot hybridization.

Subcloning of DHBV pre-S/S and S genes into the eukaryotic expression vector.

pcDNA I/Amp (Invitrogen, San Diego, Calif.) containing the cytomegalovirus early promoter/enhancer sequence and the polyadenylation signal from simian virus 40 was chosen as the vector to express DHBV pre-S/S and S proteins in vivo following DNA vaccination. Cloning of the pre-S/S and S genes into the BamHI site of the plasmid was facilitated by introducing BglII sites (AGATCT) into both ends of the DHBV DNA fragments by PCR (Fig. 1). Two pairs of primers (31CG.792/31CG.1854c and 31CG.1131/31CG.1854c, numbered according to the HBDS31.CG sequence, a full-length genomic sequence of a Chinese DHBV isolate [36]) were used to amplify the pre-S/S and S genes, respectively. The sequences of the primers are as follows: 31CG.792, 5′-GGC-AGATCTAAGTTCCTGATGGG-3′; 31CG.1131, 5′-GGC-AGATCT-ACCACCACCATTCC-3′; and 31CG.1854c, 5′-GGC-AGATCT-CCGAGGAATCGTAT-3′. A 10-ng portion of pBL 4.8 DNA was amplified in a 50 μl of PCR buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.3], 50 mM KCl, 3 mM MgCl2, 200 μM [each] deoxynucleoside triphosphates, 100 mM each primer, 1.25 U of AmpliTaq polymerase [Pharmacia]). The first cycle was performed at 94°C for 2 min 30 s, 55°C for 1 min, and 72°C for 1 min. DNA was then amplified for 33 cycles (94°C for 50 s, 55°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 40 s) followed by a final extension step at 72°C for 5 min. The PCR products were purified with a QIAquick Spin PCR purification kit (Qiagen) as specified by the manufacturer and redissolved in distilled water. The amplified pre-S/S or S genes were digested with BglII and cloned into the BamHI site of pcDNA I/Amp before transformation into Escherichia coli TOP10F′ (Invitrogen). The pcDNA I–pre-S/S and pcDNA I-S plasmids were confirmed by restriction enzyme analysis and Southern blot hybridization with an α-32P-labeled full-length DHBV probe. The nucleotide sequences of the amplified pre-S/S and S genes in both constructs were verified by sequencing and compared with the sequence of the parental AusDHBV clone. Plasmid DNA was purified by anion-exchange chromatography, with a QIAfilter Plasmid Maxi Prep kit (Qiagen) as specified by the manufacturer, and DNA was dissolved in sterile phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) at 1 mg/ml.

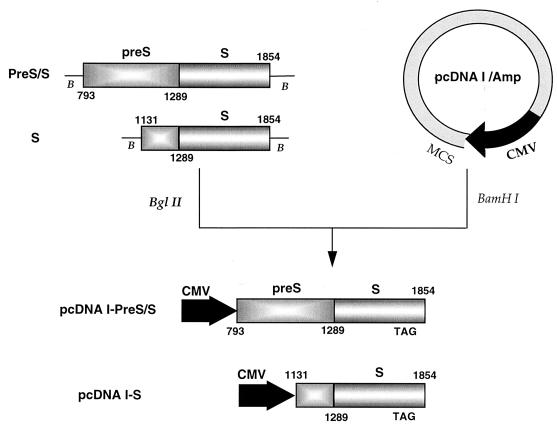

FIG. 1.

Schematic diagram of the cloning of the pre-S/S and S genes of AusDHBV into pcDNA I/Amp. The pre-S/S and S genes of AusDHBV were amplified, BglII sites were introduced at both 5′ ends by PCR, and the products were subcloned into the BamHI site of pcDNA I/Amp downstream of a CMV promoter. The numbers shown are the nucleotide positions in the pre-S/S and S genes, according to HBDS31.CG (36). The start codon for the pre-S/S gene in the pcDNA I–pre-S/S DNA construct is positioned at nucleotide 801. The pcDNA I-S construct contains an extra 158 nucleotides of pre-S sequence (nucleotides 1131 to 1288) upstream of the S start codon (nucleotide 1289) due to the primer site chosen for PCR. TAG is the stop codon for the pre-S/S and S genes, positioned at nucleotide 1793. B, BglII restriction site; MCS, multiple-cloning site; CMV, cytomegalovirus.

Transient transfection of the COS7 cell line.

COS7 cells were grown at 37°C in 5% CO2 in 24-well plates (Falcon, Becton Dickinson Labware) containing Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium supplemented with 5% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 2 mM l-glutamine, 12 ng of penicillin per ml, and 160 ng of gentamicin per ml until the cells reached 50 to 60% confluency. The cells were washed once with PBS, and 300 μl of DMEM (supplemented as above, except with 1% FBS) was added. Then 20 μl of transfection mixture [1 μg of plasmid DNA, 5 μg of N-[1-(2,3,-dioleoyloxy)propyl]-N,N,N-trimethylammoniummethylsulfate (DOTAP; Boehringer), 14 μl of HEPES-buffered saline (150 mM NaCl, 20 mM Hepes)] was held at room temperature (RT) for 15 min and added to the cells, which were then incubated at 37°C in 5% CO2 overnight. The medium was replaced on the following day with 1 ml of DMEM supplemented with 5% FBS, and the cells were grown for 2 days. Expression of the DHBV pre-S/S and S proteins was detected by indirect immunofluorescence (IMF) as described previously (24) with minor modifications. Briefly, the cells were washed twice with cold PBS, air dried, and fixed with chilled (−20°C) methanol for 10 min at RT. After removal of the methanol and air drying, 200 μl of the corresponding primary antibody was added: a 1/1,000-dilution of anti-pre-S monoclonal antibody 1H.1 (ascites fluid) (28), or a 1/50 dilution of rabbit anti-DHBs (29). The reaction mixture was incubated for 30 min at 37°C, the cells were washed three times with PBS, and 200 μl of the corresponding secondary antibody [fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated sheep anti-mouse (Silenius) or fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated anti-rabbit F(ab′)2 fragment (Silenius)] at a 1/50 dilution in PBS was added. After a further incubation at 37°C for 1 h, the cells were washed as above, mounted in 90% glycerol–50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.6) in PBS, and examined under an inverted fluorescence microscope.

Vaccination protocols.

Ducks (6 months old and 3 weeks old) were vaccinated i.m. in the quadriceps anterior muscle with 750 or 250 μg, respectively, of pcDNA I/Amp containing either the pre-S/S or the S gene. At 5 days before DNA vaccination, the injection sites were treated with 750 μl (6-month-old ducks) or 250 μl (3-week-old ducks) of bupivacaine HCl 0.5% (Marcain; Astra) to induce muscle necrosis and subsequent muscle regeneration (11, 39). At 15 min before vaccination, the muscle sites were injected with 750 μl (6-month-old ducks) or 250 μl (3-week-old ducks) of 25% (wt/vol) sucrose in PBS. All injections were carried out with 1-ml syringes fitted with 26-gauge needles. The DNA vaccination was repeated 3 and 6 weeks later by the same procedure.

Serological assays. (i) Detection of total anti-DHBs antibodies by antibody capture ELISA.

Serum samples were collected weekly after vaccination and analyzed for the presence of anti-DHBs antibodies by antibody capture enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) (20). A 100-μl sample of anti-pre-S monoclonal antibody 1H.1 (1/10,000 dilution of ascites fluid in 0.1 M NaHCO3 [pH 9.6]) (28) was used to coat 96-well microdilution plates (Disposable Products Pty. Ltd.) at 37°C for 1 h and then at 4°C overnight. Nonspecific sites were blocked with 150 μl of 5% skim milk (Carnation) in PBS–0.05% Tween 20 (PBS-T), and then 100 μl of DHBsAg (1 ng/μl; purified on sucrose gradients from the serum of congenitally DHBV-infected ducks [30]) was added to each well. The plates were incubated with fivefold dilutions of serum samples (starting at a dilution of 1/25) and then with 100 μl of rabbit anti-duck immunoglobulin Y (purified from duck egg yolks) (2) at a 1/5,000 dilution. Finally, the plates were incubated with 100 μl of horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated goat-anti-rabbit (Kirkegaard & Perry Laboratories, Inc., Gaithersburg, Md.) at a dilution of 1/5,000. Bound antibodies were visualized by the addition of 100 μl of HRP substrate (40 mg of o-phenylendiamine [Sigma] plus 0.012% H2O2 in 100 ml of 0.1 M citrate-phosphate buffer [pH 5.0]) and incubation in the dark for 15 min; the reaction was stopped by adding 50 μl of 2.5 M H2SO4. The optical density at 490 nm (OD490) was read on an automatic ELISA reader (Dynatech MR5000). The antibody titer in each serum sample was defined as the highest serum dilution that resulted in an OD490 of 0.5. Each incubation step was carried out for 1 h at 37°C, and the plates were washed three times with PBS-T between each step, except prior to addition of the HRP substrate, when they were washed three times with PBS. All dilutions were made in PBS-T containing 5% skim milk.

(ii) Detection of anti-S antibodies by ELISA.

Yeast-derived (recombinant) DHBV S protein was used to coat plates in a specific assay for anti-S antibodies. For this purpose, the S gene of AusDHBV was cloned downstream of a GAL promoter in a yeast plasmid, pYCpG2 (31). The S protein was expressed in Saccharomyces cerevisiae after induction with 2% galactose for 8 to 12 h. Yeast-derived DHBV S protein was recovered after lysis of the yeast cells with glass beads (diameter, 425 to 600 μm [Sigma]) and purification by sequential ultracentrifugation in an SW 41 rotor, first onto a 1-ml 70% sucrose cushion (12,500 rpm for 14 h at 4°C) and then onto 20 to 50% continuous sucrose gradients (39,000 rpm for 14 h at 4°C) (22). To detect anti-S antibodies, the plates were coated with 100 μl (1 ng/μl) of purified yeast-derived DHBV S protein in 0.1 M NaHCO3 (pH 9.6) at 37°C overnight. Nonspecific sites were blocked with 150 μl of 5% skim milk in PBS-T, and the plates were incubated with fivefold dilutions of serum samples (starting at a dilution of 1/25). Subsequent steps were performed exactly as for the total anti-DHBs assay.

Virus challenge.

All vaccinated young ducks and one nonvaccinated duck were challenged with a high-titer dose of DHBV (1.9 × 1011 DHBV DNA genomes). The ducks were cannulated via the jugular vein, and 20 ml of pooled serum containing ∼9.5 × 109 DHBV genomes/ml (18) was injected through the cannula. Blood samples were collected before virus challenge (prebleed) and at 1, 5, 15, 30, 45, 60, and 90 min and 2 h postchallenge (p.c.). For viral DNA extraction from serum after the virus challenge, 100 μl of duck serum collected at each time point p.c. was centrifuged through 1 ml each of 10 and 20% sucrose in TN buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.4], 100 mM NaCl) at 55,000 rpm in a Beckman TLS-55 rotor for 3 h at 4°C (19). The pellet containing viral DNA was digested for 1 h at 37°C in 50 μl of TN buffer containing 2 mg of pronase per ml, 20 ng of salmon sperm DNA per ml, 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), and 10 mM EDTA. The reaction was terminated by adding 20 mM EDTA, and samples were stored at −20°C. To assess the extent of DNA loss during sample processing, 100 μl of pooled serum inoculum containing a known amount of DNA (26 ng of DHBV DNA/ml) (18) was pelleted separately and digested with pronase and SDS in the same manner. Extracted samples equivalent to 50 μl of original serum or 10 μl of pooled serum inoculum (containing 260 pg of DNA) were analyzed by agarose gel electrophoresis and Southern blot hybridization. The relative amounts of viral DNA remaining in the bloodstream at each time point p.c. were quantitated by a Molecular Dynamics PhosphorImager system with 260 pg of extracted inoculum and 50 pg of DHBV DNA (gel purified from pBL 4.8 DNA after digestion with EcoRI and PvuI to release a full-length DHBV genome) as standards. The percent virus removal was calculated based on the DHBV DNA concentration at each time point p.c. compared to the 100% value defined as the DHBV DNA concentration of the inoculum corrected for a 10× dilution effect (20 ml of inoculum/200 ml of total blood volume, calculated as 7% of body weight) occurring immediately after inoculation.

Liver biopsy.

Liver biopsies were performed at 4 days p.c. and in some cases 2 weeks before challenge. Liver tissue samples (∼200 mg) were dissected from the right lobe and divided into three pieces: (i) snap-frozen in liquid N2 for total DNA and covalently closed circular DHBV DNA (cccDNA) extraction, (ii) fixed in formalin for histological analysis, and (iii) fixed in ethanol-acetic acid (EAA) (3:1) for viral antigen detection. EAA fixation was performed at room temperature for 30 min and was followed by treatment in chilled (−20°C) 70% ethanol overnight; then the blocks were processed into paraffin wax and sectioned onto gelatin-coated slides.

(i) Total and cccDNA extraction from liver tissue.

Viral DNA (total and cccDNA) was extracted from liver tissues as described previously (17). A 100-mg sample of frozen liver tissue was homogenized in 3 ml of 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4)–10 mM EDTA buffer on ice. Total DNA was extracted from 1.5 ml of liver homogenate, initially diluted to 4 ml with 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4)–10 mM EDTA, and digested with an equal volume of pronase-SDS (final concentrations, 4 mg of pronase per ml, 0.1% SDS, 0.15 M NaCl, 10 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.4], and 10 mM EDTA) at 37°C for 2 h. The total DNA was phenol-chloroform extracted, ethanol precipitated at −20°C overnight, washed three times with 70% ethanol, and redissolved in 400 μl of TE (10 mM Tris HCl [pH 7.4], 1 mM EDTA) buffer containing 100 μg of RNase A per ml. The cccDNA was extracted from the remaining 1.5 ml of liver homogenate by incubation with 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4)–10 mM EDTA–0.5% SDS–0.5 M KCl buffer at RT for 30 min followed by centrifugation at 10,000 rpm (Beckman JA-20.1 rotor) for 20 min at 4°C. The cccDNA in the supernatant was then phenol-chloroform extracted, ethanol precipitated at RT for >30 min, washed three times with 70% ethanol, and redissolved in 200 μl of TE buffer. Samples (25 μl each) of total and cccDNA were subjected to agarose gel electrophoresis followed by Southern blot hybridization.

(ii) Viral antigen detection in tissue sections.

Viral pre-S antigen was detected in EAA-fixed liver tissues by standard immunoperoxidase techniques (18) with anti-pre-S monoclonal antibody 1H.1 (28), followed by HRP-conjugated sheep anti-mouse antibody (Amersham). Bound conjugate was visualized with diaminobenzidine (Sigma), counterstained with hematoxylin, mounted with DPX (Koch-light Laboratories) under glass coverslips, and examined by light microscopy.

In vivo neutralization assay.

A sample of virus inoculum diluted to 10 μl in normal duck serum (NDS) containing 106 DHBV DNA genomes (equivalent to 106 50% infective doses [ID50] [18]), was preincubated at 37°C for 1 h alone or with serum collected from the pre-S/S (R76) and S (R81) DNA-vaccinated ducks (anti-pre-S/S and anti-S serum, respectively). Based on the results of virus removal from the bloodstream of vaccinated ducks (see Results), different volumes of neat anti-pre-S/S serum (20, 40, and 80 μl) or anti-S serum (5, 10, and 20 μl) were used. The total anti-DHBs antibody titers of both antisera were similar as determined by ELISA. After 1 h of incubation, the volume of the mixture was adjusted to 100 μl with NDS, and the mixture (100 μl) was inoculated intravenously (i.v.) into groups of 1-day-old ducklings (three animals/volume of serum tested). The ducks were bled weekly, and viremia was detected by ELISA for DHBsAg (18) and by spot blot hybridization for viral DNA (30). The detection limit of spot blot hybridization was 0.5 pg of DNA.

In vitro neutralization assay.

Primary duck hepatocytes (PDH) were obtained from 2- to 3-week-old ducklings by collagenase perfusion of the liver as described previously (30, 35). The cells were seeded at 1.5 × 106 cells per well in six-well plates (Falcon, Beckton Dickinson) in Leibovitz’s L-15 medium (Gibco-BRL) supplemented with 5% FBS, 2 mM l-glutamine, 12 ng of penicillin per ml, 160 ng of gentamicin per ml, 1 μg of insulin per ml, 10 U of nystatin per ml, and 10−5 M hydrocortisone hemisuccinate and were incubated at 37°C without CO2. The maintenance medium (L-15 medium without FBS) was changed every day, and the in vitro neutralization assay was performed 1 day postplating. A sample of 30 μl of virus inoculum (sucrose gradient-purified DHBV from serum containing 7 × 107 DHBV DNA genomes, equivalent to 5.4 × 104 50% tissue culture infective doses [TCID50] [30]) was preincubated with 35 or 70 μl of either anti-S, anti-pre-S/S, or a mixture of equal volumes (35 or 70 μl) of each antiserum for 1 h at 37°C, and the volume was adjusted to 1 ml with L-15 medium prior to inoculation into each well of PDH. The cells were incubated with 1 ml of virus-antibody mixture for 12 h at 37°C, and then a further 2 ml of fresh L-15 medium was added without removing the inoculum. As a positive control of infection, the same concentration of virus preincubated with NDS was used. The cells were incubated at 37°C and harvested at 7 days postinoculation (p.i.) for detection of DHBV replication. The total intracellular DNA was extracted as described previously (30), and the DHBV DNA content in each sample was analyzed by Southern blot hybridization.

RESULTS

Expression of DHBV pre-S/S and S proteins in vitro by pcDNA I–pre-S/S and pcDNA I-S plasmids.

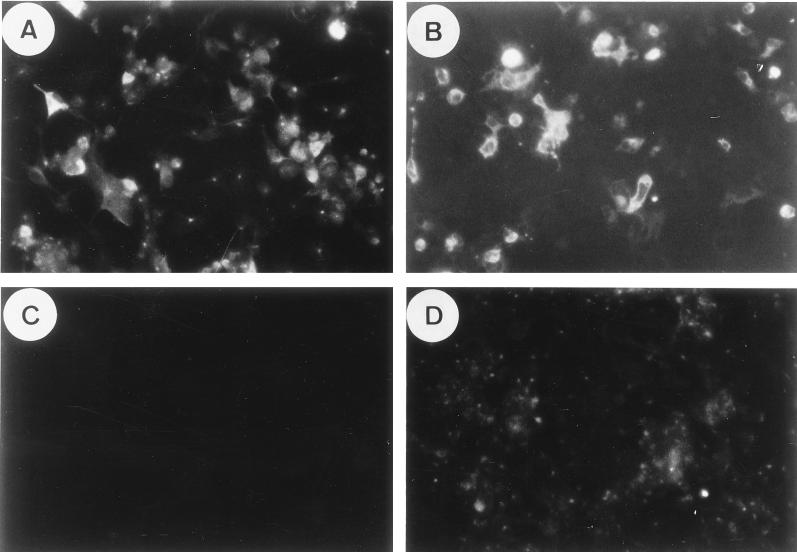

The ability of recombinant pcDNA I/Amp plasmids to express DHBV pre-S/S and S proteins was confirmed by transient transfection of COS7 cells, with the parental plasmid, pcDNA I/Amp, serving as a negative control. As shown in Fig. 2A and B, the expression of DHBsAg proteins was detected at 2 days posttransfection by indirect IMF at approximately equivalent intensity with both pcDNA I–pre-S/S and pcDNA I-S constructs, while cells transfected with the parental plasmid, pcDNA I/Amp, did not react with either antiserum (Fig. 2C and D). Western blot analysis was also performed to determine the protein species expressed by pcDNA I/Amp constructs in COS7 cells with anti-pre-S 1H.1 (28) and anti-S 1B.10 (7) monoclonal antibodies (kindly donated by J. Pugh and P. Marion, respectively). The pre-S/S protein (37 kDa) and a very small amount of S protein (17 kDa) were detected in cell lysates, but not in the culture medium, of the cells transfected with the pcDNA I–pre-S/S plasmid. In contrast, the pcDNA I-S construct expressed the S protein (17 kDa), which could be detected in both cell lysates and the culture medium, suggesting that the S protein was secreted by the cells transfected with pcDNA I-S (data not shown).

FIG. 2.

Transient transfection of COS7 cells with pcDNA I–pre-S/S and pcDNA I-S plasmids. DHBV protein expression in COS7 cells was detected by indirect IMF 2 days after transfection with the respective plasmids (see Materials and Methods). Anti-pre-S 1H.1 monoclonal antibodies were used to detect pre-S protein (A) expressed by pcDNA I–pre-S/S; and rabbit-anti-DHBs antibodies were used to detect S protein (B) expressed by pcDNA I-S. Cells transfected with the parental plasmid, pcDNA I/Amp, showed negative results when reacted with anti-pre-S (C) or anti-DHBs (D) antibodies.

Anti-DHBs responses following DNA vaccination.

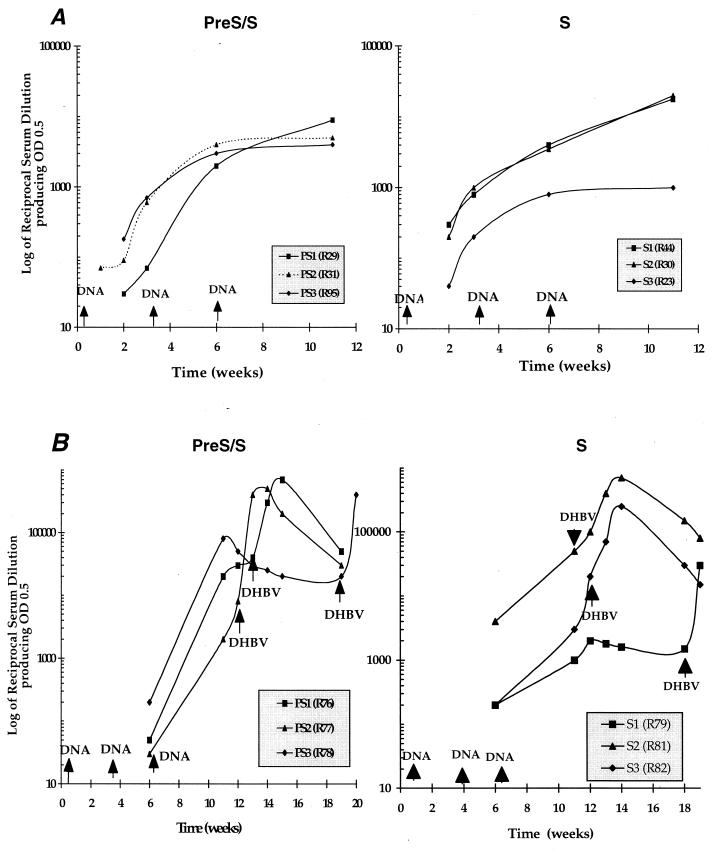

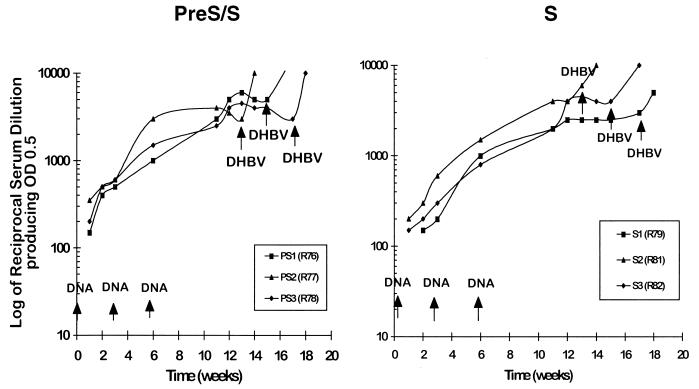

Both pre-S/S and S DNA-vaccinated ducks (6 months old) elicited high titers of anti-DHBs antibodies following vaccination (Fig. 3A). The use of purified DHBsAg from serum as the antigen source in ELISA indicated that antibodies raised by DNA vaccination recognized the native form of serum-derived DHBsAg. Anti-DHBs could be detected 2 weeks after the first DNA injection, and the titers increased with subsequent vaccinations. Total anti-DHBs titers after the third vaccination ranged between 3,500 and 8,000. One duck (R23) that gave a poor antibody response was diagnosed subsequently by Congo red staining on liver tissue as suffering from secondary amyloidosis. Young (3-week-old) ducks also developed high titers of anti-DHBs antibodies following DNA vaccination (Fig. 3B). After the third vaccination, the antibody titers in pre-S/S and S DNA-vaccinated ducks ranged between 10,000 and 40,000 and between 20,000 and 50,000, respectively.

FIG. 3.

Anti-DHBs antibody responses following DNA vaccination in ducks. Two groups each of 6-month-old (A) and 3-week-old (B) ducks were vaccinated with either pre-S/S or S DNA vaccines three times at 3-week intervals. Total anti-DHBs antibody levels were measured by an antibody capture ELISA with DHBsAg purified from the serum of congenitally DHBV-infected ducks as the source of antigen (see Materials and Methods). The antibody titer was defined as the highest serum dilution that gave an OD490 of 0.5. In 3-week-old ducks, anti-DHBs antibody responses were also measured following virus challenge (indicated by DHBV →), which was performed at various times after the third vaccination.

Since the above assay would detect antibodies to both pre-S and S antigens, we then determined the specific anti-S antibody responses in pre-S/S and S DNA-vaccinated young ducks by ELISA with yeast-derived S protein as the source of antigen. The specific anti-S titers in the two groups were equivalent, ranging between 2,500 and 4,000 after the third vaccination (Fig. 4).

FIG. 4.

Anti-S-specific responses in the pre-S/S and S DNA-vaccinated 3-week-old ducks. The same ducks as those used for the experiment in Fig. 3B were also measured for the presence of anti-S-specific antibodies in serum by ELISA with recombinant DHBV S protein (yeast derived) as the source of antigen (see Materials and Methods). The antibody titers were defined as the highest serum dilution that gave an OD490 of 0.5. Virus challenge (indicated by DHBV →) was performed at various times after the third vaccination.

Removal of DHBV from the bloodstream of DNA-vaccinated ducks following virus challenge.

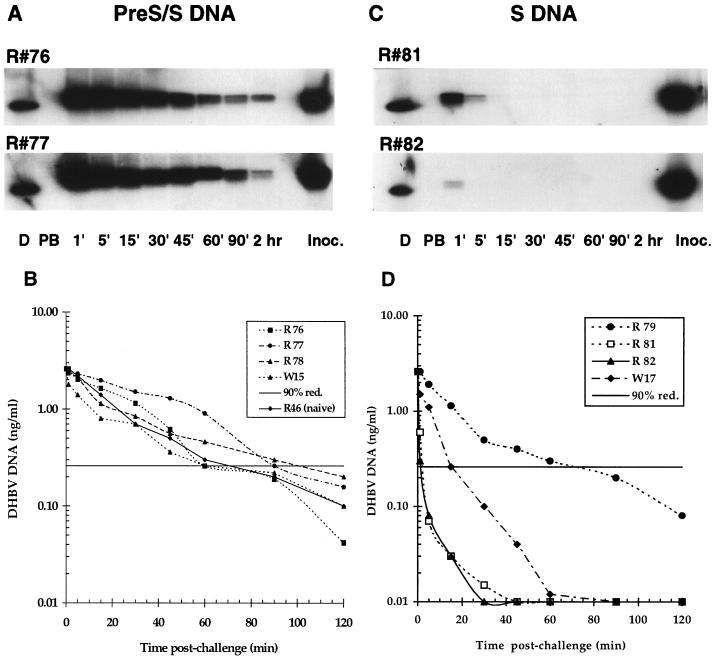

An i.v. virus challenge was performed 3 to 8 weeks after the third vaccination in all young ducks (10 to 18 weeks old at the time of challenge). The rate of virus removal from the bloodstream was analyzed by determining the DHBV DNA content of serum samples collected from 1 min to 2 h p.c. Examples of virus removal profiles following i.v. inoculation in ducks vaccinated either with pre-S/S or S DNA are shown in Fig. 5A and B and Fig. 5C and D, respectively. The pre-S/S DNA-vaccinated ducks (R76 and R77) showed 90% removal of the inoculum after 60 and 90 min (Fig. 5A). Two other pre-S/S DNA-vaccinated ducks (R78 and W15) showed similar results, with 90% removal of the virus inoculum in 90 and 60 min (Fig. 5B). This is similar to the rate of virus removal measured in nonvaccinated ducks inoculated with an identical dose of virus (e.g., 70 min for R46), as shown in Fig. 5B. In contrast, the S DNA-vaccinated ducks (R81 and R82) showed 90% removal of the inoculum in less than 5 min p.c. (Fig. 5C). Two other S DNA-vaccinated ducks (W17 and R79) showed 90% removal of the inoculum in 15 and 60 min, respectively (Fig. 5D).

FIG. 5.

Removal of DHBV from the bloodstream of DNA-vaccinated ducks following virus challenge. (A and C) Southern blot analysis of virus removal from the bloodstream of pre-S/S and S DNA-vaccinated ducks. The results for two ducks of each group (R76 and R77 for pre-S/S, and R81 and R82 for S) are shown. Serum samples were taken serially at the indicated times p.c. and were extracted for DHBV DNA as described in Materials and Methods. Lanes: D, 50 pg of DHBV DNA/pBL4.8; PB, prebleed before challenge; Inoc., 5 μl of extracted inoculum, equivalent to 260 pg of DHBV DNA. (B and D) Rate of virus removal from the bloodstream of all pre-S/S and S DNA-vaccinated ducks (four ducks per group). The rate of removal of an identical dose of virus from a nonvaccinated duck (R46) is also shown (B). A concentration of 2.6 ng of DHBV DNA/ml in the inoculum at 0 min was calculated by correction for the 10× dilution effect (20 ml/200 ml of total blood volume) occurring immediately after inoculation. The y axis shows the relative amount of viral DNA remaining in the bloodstream at each indicated time p.c. The DHBV DNA concentration remaining after removal of 90% of the inoculum is shown (90% red.).

Detection of viral replication in liver tissue after challenge.

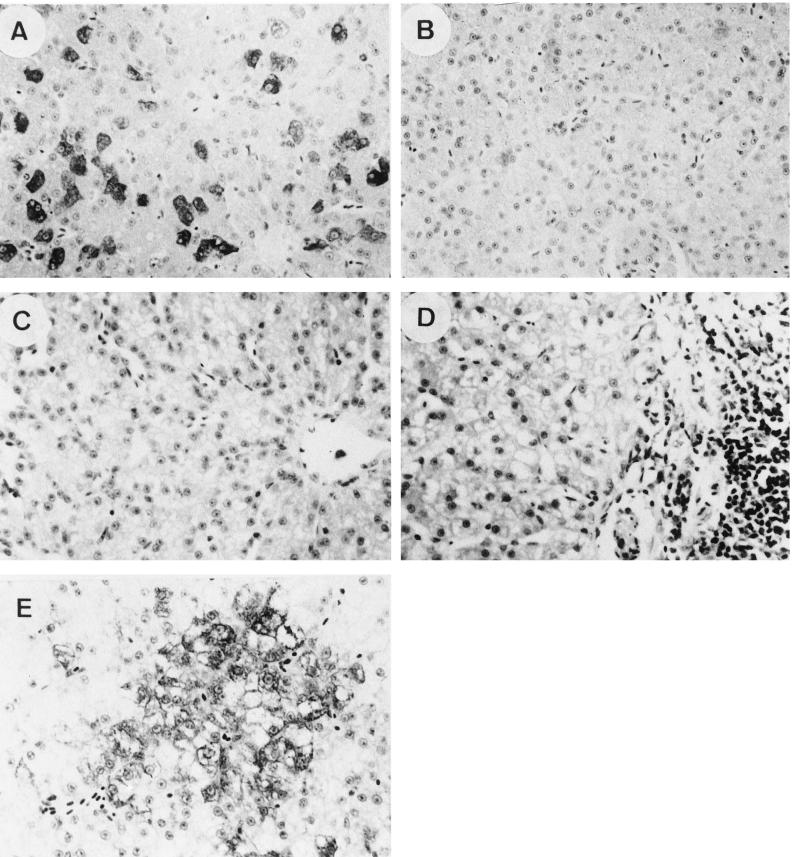

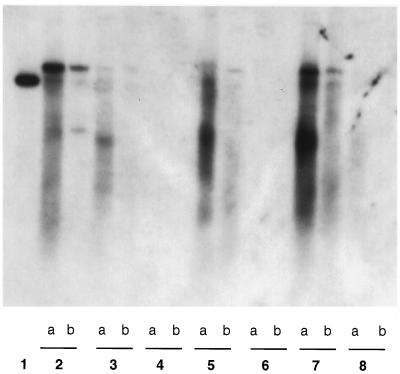

Liver biopsies were performed 4 days p.c. to assess the extent of virus replication. DHBsAg was found in 10 to 40% of hepatocytes in the liver of pre-S/S DNA-vaccinated ducks (Fig. 6A), and significant levels of viral DNA were detected in Southern blot analysis (Fig. 7, lanes 3, 5, and 7). Nonetheless, virus infection in the liver was likely to be restricted, because viremia (determined by analysis of serum for DHBsAg and DHBV DNA) was not detected during 8 weeks of monitoring. In both pre-S/S and S DNA-vaccinated ducks, a range of mild to moderate mononuclear cell inflammation was present around the portal areas of the liver at 4 days p.c. but not prior to challenge (Fig. 6C and D). It is therefore possible that both cell-mediated and humoral immune responses played a role in preventing more widespread viral replication in these vaccinated ducks. In contrast, when nonvaccinated ducks of a similar age (4 months old) were inoculated with a similar high dose of DHBV, widespread viral infection affecting more than 95% of hepatocytes (Fig. 6E) and transient viremia were normally seen (20).

FIG. 6.

(A, B, and E) Detection of DHBsAg by immunoperoxidase staining in liver tissues of pre-S/S and S DNA-vaccinated and nonvaccinated ducks 4 days p.c. DHBsAg was detected in 10 to 40% of the hepatocytes of pre-S/S (A), but not S (B) DNA-vaccinated ducks. In contrast, a nonvaccinated duck showed more widespread virus infection, with more than 95% of hepatocytes being DHBsAg positive (E). (C and D) Detection of mononuclear cell infiltrates in liver tissue of S DNA-vaccinated ducks before and after challenge. Significant mononuclear cell infiltrates were not detected in the liver tissue (represented by W17) taken 2 weeks before challenge (C) but were present in the sample taken 4 days p.c. (D). Sections were stained with hematoxylin-eosin. Magnification, ×40.

FIG. 7.

Detection of viral replication (total and cccDNA) in the liver of DNA vaccinated-ducks 4 days p.c. Viral DNA was extracted from liver tissues as described in Materials and Methods and analyzed by Southern blot hybridization. Lanes: 1, 50 pg of linear DHBV DNA (pBL4.8); 2, total DNA and cccDNA of the positive control (extracted from the liver of a congenitally DHBV-infected duck); 3, 5, and 7, total DNA and cccDNA of three pre-S/S DNA-vaccinated ducks (R76, R77, and R78); 4, 6, and 8, total DNA and cccDNA of three S DNA-vaccinated ducks (R81, R82, and R79) (lanes a contain total DNA; lanes b contain cccDNA).

On the other hand, DHBsAg-positive hepatocytes were not detected in three of four S DNA-vaccinated ducks (Fig. 6B), while very few positive hepatocytes (∼2%) were found in the fourth duck (R79) (data not shown). Duck R79 also showed a slower initial antibody response to vaccination and slower removal of challenge inoculum (45 min) than did the other ducks in this group. Southern blot analysis of viral DNA extracted from the above biopsy specimens was consistent with the above findings, with no evidence of virus replication in those S DNA-vaccinated ducks that showed rapid removal of virus from the bloodstream and low levels of virus DNA in duck R79 (Fig. 7, lanes 4, 6, and 8). The different outcome in this duck might be related to the lower antibody titer at the time of virus challenge compared to the others (Fig. 3B).

In vivo neutralization.

To determine whether the protection against virus challenge seen in the vaccinated ducks was due to humoral antibody, serum from both pre-S/S and S DNA-vaccinated ducks (R76 and R81, respectively), obtained 1 week after the third DNA vaccination, was preincubated with 106 DHBV DNA genomes (equivalent to 106 ID50). Based on the results of DHBV challenge of S DNA-vaccinated ducks (see above), we estimated that a total inoculum of 1.9 × 1011 DHBV DNA genomes had been neutralized in vivo in the presence of circulating antibody equivalent to 200 ml of total blood volume, i.e., 7% of body weight. Therefore, theoretically 106 DHBV DNA genomes might be neutralized by approximately 1 μl of serum. Preincubation of the virus inoculum with 5, 10, or, 20 μl of anti-S serum at 37°C for 1 h prior to i.v. inoculation into 1-day-old ducklings (three animals/group) completely prevented the development of viremia during a 4-week observation period in all the ducks in all the groups. In contrast, viremia developed in all the ducks receiving virus that had been preincubated with 20 or 40 μl of anti-pre-S/S serum, and in two of three ducks that received inoculum which had been preincubated with 80 μl of anti-pre-S/S serum. In the control group, all three ducklings inoculated with virus developed persistent viremia, which was monitored until 4 weeks p.i. Thus, 5 μl of anti-S antiserum neutralized virus infectivity completely under the in vivo conditions used, while with anti-pre-S/S antiserum, only partial neutralization was seen with the largest volume (80 μl) used (data not shown).

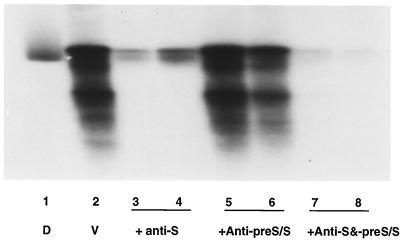

In vitro neutralization assay.

PDH cultures were inoculated 1 day postplating with 30 μl of virus inoculum containing 7 × 107 DHBV DNA genomes (equivalent to 5.4 × 104 TCID50), and the cells were examined for replicative DHBV DNA at 7 days p.i. by Southern blot hybridization. Preincubation of virus at 37°C for 1 h with either 35 or 70 μl of anti-S serum reduced the final level of intracellular DHBV DNA by 90 to 95% compared to that in the positive control (Fig. 8, lanes 2 to 4), consistent with the above calculations that 106 DHBV DNA genomes might have been neutralized by approximately 0.5 to 1 μl of anti-S serum in vivo. In contrast, virus infectivity was not affected by preincubation with 35 μl of anti-pre-S/S serum and was reduced only 50% after preincubation with 70 μl of anti-pre-S/S serum (lanes 5 and 6). We next wished to test whether the reduced neutralizing ability of the pre-S/S antiserum was due to a reduced neutralizing ability of the S antibody component, or inhibition of neutralization by pre-S antibody. When equal volumes of anti-S and anti-pre-S/S sera were combined (35 or 70 μl of each serum), the extent of neutralization was enhanced slightly, since the amount of DHBV DNA was reduced by 96% (lanes 7 and 8). This result demonstrated that the reduced neutralizing capacity of the anti-pre-S/S antiserum, seen consistently above, was likely to be due to an impaired neutralizing capacity of the S antibody component of this antiserum (despite equivalent ELISA titers), not to an inhibitory effect of anti-pre-S antibody in the presence of potent anti-S antibody. A summary of the findings in this study is presented in Table 1.

FIG. 8.

In vitro neutralization assay. PDH cultures were inoculated with a virus inoculum containing 7 × 107 DHBV DNA genomes (equivalent to 5.4 × 104 TCID50), which had been preincubated for 1 h at 37°C with 35 or 70 μl of either anti-S (lanes 3 and 4), anti-pre-S/S (lane 5 and 6), or a mixture of equal volumes of the two antisera (35 or 70 μl of each antiserum) (lanes 7 and 8). The cells were harvested 7 days p.i. and analyzed for viral replication by Southern blot hybridization. Each lane represents the total DHBV DNA extracted from individual wells of a six-well plate. Lane 1 (D) contains 50 pg of DHBV DNA; lane 2 (V) contains virus alone (5.4 × 104 TCID50).

TABLE 1.

Summary of pre-S/S- and S-DNA vaccination in 3-week-old ducks

| DNA vaccine | Prechallenge

|

Postchallenge

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total anti-DHBs titera | Neutralization

|

Virus removal rate (min)d | Viral replicatione | Histological changesf | ||

| In vivob | In vitroc | |||||

| S-DNA | (2–5) × 104 (4/4) | 3/3 neutralized by >5 μl of anti-S | 90–95% reduction in viral DNA by 35 and 70 μl of anti-S | <5–15 (3/4) | Not detected (3/4) | Mild (3/4) |

| 45 (1/4) | ∼2% hepatocytes (1/4) | Marked (1/4) | ||||

| Pre-S/S-DNA | (1–4) × 104 (4/4) | 1/3 neutralized by 80 μl of anti-preS/S, no neutralization by 20 and 40 μl of serum | 50% reduction in viral DNA by 70 μl of anti-pre-S/S; no reduction by 35 μl | 45–90 (4/4) | 10–40% hepatocytes (4/4) | Mild to moderate (4/4) |

The range of total anti-DHBs antibody titers as measured by ELISA after the third vaccination from four ducks/group. Numbers in parentheses show the number of ducks.

Neutralizing ability of serum from vaccinated ducks when preincubated with 106 DHBV DNA genomes (106 ID50) prior to inoculation into 1-day-old ducklings (three animals/group). Different volumes of neat anti-S (5, 10, and 20 μl) or anti-pre-S/S (20, 40, and 80 μl) sera from ducks R81 & R76, respectively, were used.

Neutralizing ability of serum when preincubated with 7 × 107 DHBV DNA genomes prior to inoculation of PDH cultures.

The time taken for removal of 90% of virus inoculum from the bloodstream PC as determined by Southern blot hybridization. Numbers in parentheses show the number of ducks.

Viral replication in the liver 4 days p.c., determined by the presence of total DNA and cccDNA, as well as by the presence of viral antigen (DHBsAg)-positive hepatocytes. Numbers in parentheses show the number of ducks.

Histological changes seen in the liver tissue samples taken 4 days p.c., in relation to the presence of periportal necrosis, intralobular degeneration and focal necrosis, portal inflammation, and fibrosis (23). Numbers in parentheses show the number of ducks.

DISCUSSION

This study demonstrated the ability of DNA vaccines to elicit humoral immune responses against DHBV surface proteins in ducks, as has been reported previously for HBV surface proteins in mice and chimpanzees (9, 10, 12). Ducks vaccinated i.m. with pcDNA I/Amp containing either the DHBV pre-S/S or S genes produced very high titers of anti-DHBs antibodies. The strong antibody responses may have been facilitated by the use of a local anesthetic (bupivacaine HCl) to induce muscle regeneration (11, 39) and injection of 25% (wt/vol) sucrose to aid the even distribution of DNA uptake by muscle cells (11). In addition, the use of pcDNA I/Amp, which contains two repeats of unmethylated CpG motifs in its ampR gene sequence, could contribute to the strong humoral (and cellular) immune responses seen in this study. A previous study in mice has demonstrated that DNA vaccination with a vector containing CpG motifs induced significantly higher antibody and cellular immune responses against the expressed protein β-galactosidase than was seen with a vector lacking this motif (32). The CpG motif (5′-Pur Pur CG Pyr Pyr-3′) present in bacterial DNA has been shown to preferentially activate B cells that simultaneously encounter their specific antigen, and this adjuvant property has been attributed to its unmethylated status (25).

Although ducks from both groups (6 month old and 3 weeks old) elicited anti-DHBs responses, the titers found in young ducks were much higher (10,000 to 50,000) than those found in older ducks (3,500 to 8,000). The influence of age on the expression of plasmid DNA injected i.m. has been reported previously (38): young mice (4 to 6 weeks old) expressed significantly higher levels of the reporter gene product chloramphenicol acetyltransferase than did mice older than 10 weeks. It was proposed that this could be due to a difference in DNA uptake related to the growth rate of the animal, since mice show rapid growth from 3 to 10 weeks of age. A similar mechanism might operate with ducklings, which show rapid growth until ∼4 months of age and responded better than older ducks to DNA vaccines. Alternatively, it is known that MHC class I molecules are expressed at higher levels on the surface of immature muscle fibers (14). This phenomenon might increase the presentation of DHBV envelope proteins on the surface of transfected muscle cells in the context of MHC class I. It was notable that the anti-DHBs titers found in vaccinated 6-month-old ducks were still at least three times higher than those obtained following primary DHBV infection (20).

Vaccination of ducks with either pre-S/S or S DNA vaccines prevented the development of viremia following virus challenge. However, despite the presence of approximately equal titers of anti-DHBs antibody in the two groups of vaccinated ducks at the time of challenge, significant differences were found in the rate of virus removal from the bloodstream p.c. and in the presence or absence of early virus replication in the liver. With the exception of one duck, S DNA-vaccinated ducks showed rapid removal of the inoculum from the bloodstream and showed no detectable DHBsAg or viral replication in their hepatocytes at 4 days p.c. These findings were similar to those seen after challenge of ducks that had resolved their primary infection and developed anti-DHBs (19). We also observed marked mononuclear cell infiltrates around the portal areas of the liver on day 4 p.c., which could represent virus antigen-specific T lymphocytes induced by DNA vaccination that subsequently accumulated at sites of passive uptake of challenge antigen within the liver. Potent priming of CTL responses by DNA vaccination has been demonstrated previously in mice injected i.m. with an HBsAg-expressing DNA vaccine (33).

The protection conferred by the S DNA vaccine in this study may have been due to a combined effect of humoral and cell-mediated immunity induced by the vaccine. However, humoral antibodies alone abolished virus infectivity in in vitro and in vivo neutralization assays. The precise mechanism(s) of virus neutralization in the S DNA-vaccinated ducks has yet to be determined, although several possibilities exist. First, anti-S antibodies might inhibit the attachment of virus to its specific receptor, either by direct binding to the ligand or sterically, although this mechanism alone is generally considered an inefficient process for virus neutralization (13). Alternatively, the formation of virus-antibody complexes might lead to (i) enhanced phagocytosis by macrophages and other phagocytic cells in vivo via Fc receptors or (ii) formation of aggregates by cross-linking virus particles, thus reducing their infectivity (13). The above mechanisms of virus neutralization might also require cooperative specific cellular immune responses in the in vivo system. For example, a possible role for T lymphocytes in clearing virus infection from hepatocytes and preventing cell-to-cell spread of DHBV could be inferred from the marked mononuclear cell infiltrates seen in the liver 4 days p.c.

The surprising finding from this study was that in contrast to S DNA-vaccinated ducks, all pre-S/S DNA-vaccinated ducks showed removal of the virus inoculum from the bloodstream at similar rates to nonvaccinated ducks and that virus replication was detected in 10 to 40% of hepatocytes in the liver at 4 days p.c. and was accompanied by mild to moderate inflammatory changes in the liver. However, in contrast to the nonvaccinated ducks, the vaccinated ducks did not develop transient viremia (the limit of our assay sensitivity is ∼0.5 pg of DNA by spot blot hybridization). Virus replication in the vaccinated ducks was presumably restricted due to the action of cellular and/or humoral immune responses and therefore has little clinical significance. The in vivo and in vitro neutralization assays with serum from vaccinated ducks also revealed that the marked difference between the protective efficacy of the two vaccines could be ascribed in part at least to the difference in the humoral component. The reason for the reduced ability of anti-pre-S/S antibodies to neutralize virus infectivity is unknown. Anti-S and anti-pre-S/S sera contained equivalent levels of anti-S antibody in an S-antigen-specific ELISA, but the antiserum mixing experiment demonstrated that reduced efficiency of the pre-S/S antiserum was likely to be due to an impaired function of its anti-S component rather than to inhibition by the anti-pre-S component. One possibility could be related to the nature of the intracellular DHBV pre-S/S protein expressed in the transfected muscle cells. We found that unlike the S protein, pre-S/S protein was detected only intracellularly when expressed in COS7 cells transfected with pcDNA I–pre-S/S plasmid (data not shown). This was similar to earlier reports with HBV that, unlike the major (S) envelope protein, the middle (pre-S2/S) protein was not secreted in a number of expression systems and, in fact, inhibited the expression and/or secretion of S protein (8, 9, 27). If impaired secretion is also a feature of pre-S/S protein expression in muscle in vivo, this may have affected the correct conformation of the antigens produced and subsequently the biological function of the anti-S antibodies induced. The immunogenicity of DHBV S protein has been reported previously to be conformation dependent (41). Hence, the specific anti-S antibodies raised in the pre-S/S DNA-vaccinated ducks might be conformationally different from those produced following primary DHBV infection or in S DNA-vaccinated ducks. Thus, although both pre-S/S and S antisera reacted equally with yeast-derived S protein in ELISA, some differences in biological function between the anti-S-specific antibodies produced in the pre-S/S and S DNA-vaccinated ducks might have occurred.

In summary, the results described here demonstrate the importance of anti-S antibodies alone in preventing DHBV infection in both in vitro and in vivo systems, consistent with the well-established role for anti-HBs in HBV infection in humans (15, 16, 37). The markedly poorer protection conferred by pre-S/S vaccination, despite the presence of apparently comparable levels of anti-S antibodies by ELISA, needs further clarification, particularly in the context of the development of human HBV vaccines containing pre-S proteins where serological responses can be readily monitored but protective efficacy data are difficult to obtain. Finally, this study demonstrated the advantage of DNA vaccines as a tool to explore the role of immune responses against hepadnavirus infection, thus permitting further studies on the detailed mechanism(s) of hepadnavirus neutralization in vivo and characterization of alternative vaccine strategies.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank E. Bertram for providing rabbit anti-duck IgY and for assisting in the challenge experiments, C. Scougall for preparing PDH cultures, G. Mayrhofer for helpful discussions, and P. Marion for the gift of 1B.10 monoclonal antibodies. We also thank the staff of the Veterinary Services Branch, IMVS, for animal care; the Division of Tissue Pathology, IMVS, for section preparation; and Photography Services, IMVS, for assistance in preparation of the figures. We are particularly indebted to J. Pugh for the gift of the 1H.1 monoclonal antibodies.

This research was supported by a project grant from the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia and a postgraduate fellowship (to M.T.) from the Australian Government (AusAID).

REFERENCES

- 1.Ashton-Rickardt P G, Murray K. Mutants of the hepatitis B virus surface antigen that define some antigenically essential residues in the immunodominant a region. J Med Virol. 1989;29:196–203. doi: 10.1002/jmv.1890290310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bertram E M. Characterisation of duck lymphoid cell populations and their role in immunity to duck hepatitis B virus. Ph.D. thesis. Adelaide, Australia: University of Adelaide; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carman W F, Zanetti A R, Karayiannis P, Waters J, Manzillo G, Tanzi E, Zuckerman A J, Thomas H C. Vaccine-induced escape mutant of hepatitis B virus. Lancet. 1990;336:325–329. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(90)91874-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chassot S, Lambert V, Kay A, Godinot C, Roux B, Trepo C, Cova L. Fine mapping of neutralization epitopes on duck hepatitis B virus (DHBV) Pre-S protein using monoclonal antibodies and overlapping peptides. Virology. 1993;192:217–223. doi: 10.1006/viro.1993.1024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chassot S, Lambert V, Kay A, Godinot C, Trepo C, Cova L. Identification of major antigenic domains of duck hepatitis B virus Pre-S protein by peptide scanning. Virology. 1994;200:72–78. doi: 10.1006/viro.1994.1164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cheung R C, Robinson W S, Marion P L, Greenberg H B. Epitope mapping of neutralizing monoclonal antibodies against duck hepatitis B virus. J Virol. 1989;63:2445–2451. doi: 10.1128/jvi.63.6.2445-2451.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cheung R C, Trujillo D E, Robinson W S, Greenberg H B, Marion P L. Epitope-specific antibody response to the surface antigen of duck hepatitis B virus in infected ducks. Virology. 1990;176:546–552. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(90)90025-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chisari F V, Filippi P, McLachlan A, Milich D R, Riggs M, Lee S, Palmiter R D, Pinkert C A, Brinster R L. Expression of hepatitis B virus large envelope polypeptide inhibits hepatitis B surface antigen secretion in transgenic mice. J Virol. 1986;60:880–887. doi: 10.1128/jvi.60.3.880-887.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chow Y-H, Huang W-L, Chi W-K, Chu Y-D, Tao M-H. Improvement of hepatitis B virus DNA vaccines by plasmids coexpressing hepatitis B surface antigen and interleukin-2. J Virol. 1997;71:169–178. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.1.169-178.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Davis H L, Michel M L, Whalen R G. DNA-based immunization for hepatitis B induces continuous secretion of antigen and high levels of circulating antibody. Hum Mol Genet. 1993;2:1847–1851. doi: 10.1093/hmg/2.11.1847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Davis H L, Whalen R G, Demeneix B A. Direct gene transfer into skeletal muscle in vivo: factors affecting efficiency of transfer and stability of expression. Hum Gene Ther. 1993;4:151–159. doi: 10.1089/hum.1993.4.2-151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Davis H L, McCluskie M J, Gerin J L, Purcell R H. DNA vaccine for hepatitis B: evidence for immunogenicity in chimpanzees and comparison with other vaccines. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:7213–7218. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.14.7213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dimmock N J. Neutralization of animal viruses. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 1993;183:3–31. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-77849-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Engel A G, Hohlfeld R. Immunobiology of muscle tissue. Immunol Today. 1994;15:269–274. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(94)90006-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hadler S C, Francis D P, Maynard J E, Thompson S E, Judson F N, et al. Long-term immunogenicity and efficacy of hepatitis B vaccine in homosexual men. N Engl J Med. 1986;315:209–214. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198607243150401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Iwarson S, Tabor E, Thomas H C, Goodall A, Waters J, Snoy P, Shih J W, Gerety R J. Neutralization of hepatitis B virus infectivity by a murine monoclonal antibody: an experimental study in the chimpanzee. J Med Virol. 1985;16:89–95. doi: 10.1002/jmv.1890160112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jilbert A R, Wu T-T, England J M, Hall P, Carp N D, O’Connell A P, Mason W S. Rapid resolution of duck hepatitis B virus infections occurs after massive hepatocellular involvement. J Virol. 1992;66:1377–1388. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.3.1377-1388.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jilbert A R, Miller D S, Scougall C A, Turnbull H, Burrell C J. Kinetics of duck hepatitis B virus infection following low dose virus inoculation: one virus DNA genome is infectious in neonatal ducks. Virology. 1996;226:338–345. doi: 10.1006/viro.1996.0661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jilbert, A. R., D. S. Miller, E. M. Bertram, L. Mickan, I. Kotlarski, P. Hall, and C. J. Burrell. Unpublished data.

- 20.Jilbert, A. R., D. S. Miller, J. D. Botten, E. M. Bertram, P. Hall, I. Kotlarski, and C. J. Burrell. Characterisation of age and dose-related outcomes of duck hepatitis B virus infection. Submitted for publication. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.Kane M A. Global status of hepatitis B immunisation. Lancet. 1996;348:696. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)65598-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Klingmüller U, Schaller H. Hepadnavirus infection requires interaction between the viral pre-S domain and a specific hepatocellular receptor. J Virol. 1993;67:7414–7422. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.12.7414-7422.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Knodell R G, Ishak K G, Black W C, Chen T S, Craig R, Kaplowitz N, Kiernan T W, Wollman J. Formulation and application of a numerical scoring system for assessing histological activity in asymptomatic chronic active hepatitis. Hepatology. 1981;1:431–435. doi: 10.1002/hep.1840010511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kok T W, Payne L E, Bailey S E, Waddell R G. Urine and the laboratory diagnosis of Chlamydia trachomatis in males. Genitourin Med. 1993;69:51–53. doi: 10.1136/sti.69.1.51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Krieg A M, Yi A-K, Matson S, Waldschmidt T J, Bishop G A, Teasdale R, Koretzky G A, Klinman D M. CpG motifs in bacterial DNA trigger direct B-cell activation. Nature. 1995;374:546–549. doi: 10.1038/374546a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mason W S, Seal G, Summers J. Virus of Pekin ducks with structural and biological relatedness to human hepatitis B virus. J Virol. 1980;36:829–836. doi: 10.1128/jvi.36.3.829-836.1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Persing D H, Varmus H E, Ganem D. Inhibition of secretion of hepatitis B surface antigen by a related presurface polypeptide. Science. 1986;234:1388–1391. doi: 10.1126/science.3787251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pugh J C, Di Q, Mason W S, Simmons H. Susceptibility to duck hepatitis B virus infection is associated with the presence of cell surface receptor sites that efficiently bind viral particles. J Virol. 1995;69:4814–4822. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.8.4814-4822.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Qiao M, Gowans E J, Bailey S E, Jilbert A R, Burrell C J. Serological analysis of duck hepatitis B virus infection. Virus Res. 1990;17:3–14. doi: 10.1016/0168-1702(90)90076-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Qiao, M., C. A. Scougall, A. Duszynski, and C. J. Burrell. Unpublished data.

- 31.Richardson H E, Wittenberg C, Cross F, Reed S I. An essential G1 function for cyclin-like proteins in yeast. Cell. 1989;59:1127–1133. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90768-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sato Y, Roman M, Tighe H, Lee D, Corr M, Nguyen M-D, Silverman G J, Lotz M, Carson D A, Raz E. Immunostimulatory DNA sequences necessary for effective intradermal gene immunization. Science. 1996;273:352–354. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5273.352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schirmbeck R, Böhm W, Ando K, Chisari F V, Reimann J. Nucleic acid vaccination primes hepatitis B surface antigen-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes in nonresponder mice. J Virol. 1995;69:5929–5934. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.10.5929-5934.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Triyatni, M., A. R. Jilbert, M. Qiao, and C. J. Burrell. Unpublished data.

- 35.Tuttleman J S, Pugh J C, Summers J W. In vitro experimental infection of primary duck hepatocyte cultures with duck hepatitis B virus. J Virol. 1986;58:17–25. doi: 10.1128/jvi.58.1.17-25.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Uchida M, Esumi M, Shikata T. Molecular cloning and sequence analysis of duck hepatitis B virus genomes of a new variant isolated from Shanghai ducks. Virology. 1989;173:600–606. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(89)90571-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Waters J A, O’Rourke S M, Richardson S C, Papaevangelou G, Thomas H C. Qualitative analysis of the humoral immune response to the ’a’ determinant of HBs antigen after inoculation with plasma-derived or recombinant vaccine. J Med Virol. 1987;21:155–160. doi: 10.1002/jmv.1890210207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wells D J, Goldspink G. Age and sex influence expression of plasmid DNA directly injected into mouse skeletal muscle. FEBS Lett. 1992;306:203–205. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(92)81000-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wells D J. Improved gene transfer by direct plasmid injection associated with regeneration in mouse skeletal muscle. FEBS Lett. 1993;332:179–182. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(93)80508-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yap I, Chan S H. A new pre-S containing recombinant hepatitis B vaccine and its effect on non-responders: a preliminary observation. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 1996;25:120–122. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yokosuka O, Omata M, Ito Y. Expression of pre-S1, pre-S2, and C proteins in duck hepatitis B virus infection. Virology. 1988;167:82–86. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(88)90056-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]