Abstract

BACKGROUND:

When children and youth feel connected to their school, family, and others in their community, they are less likely to engage in risky behaviors and experience negative health. Disruptions to school operations during the COVID-19 pandemic have led many teachers and school administrators to prioritize finding ways to strengthen and re-establish a sense of connectedness among students and between students and adults in school.

METHODS:

We conducted a systematic search of peer-reviewed literature that reported on US-based research and were published in English from January 2010 through December 2019 to identify classroom management approaches that have been empirically tied to school connectedness-related outcomes in K-12 school settings.

FINDINGS:

Six categories of classroom management approaches were associated with improved school connectedness among students: (1) teacher caring and support, (2) peer connection and support, (3) student autonomy and empowerment, (4) management of classroom social dynamics, (5) teacher expectations, and (6) behavior management.

IMPLICATIONS FOR SCHOOL HEALTH POLICY, PRACTICE, AND EQUITY:

Prioritizing classroom management approaches that emphasize positive reinforcement of behavior, restorative discipline and communication, development of strong, trusting relationships, and explicitly emphasize fairness has potential to promote equitable disciplinary practices in schools.

CONCLUSIONS:

Classroom management approaches most linked to school connectedness are those that foster student autonomy and empowerment, mitigate social hierarchies and power differentials among students, prioritize positive reinforcement of behavior and restorative disciplinary practices, and emphasize equity and fairness.

Keywords: classroom management, classroom facilitation, school connectedness, COVID-19

Schools play a critical role in promoting students’ health and development by creating environments where all students feel that they are cared for, supported, and belong. When youth feel connected to their school, family, and others in their community, they are less likely to engage in risky behaviors and in turn, less likely to experience negative health outcomes in adolescence and adulthood.1–3 Specifically, students who feel connected and engaged at school are less likely to exhibit emotional distress and report fewer risky behaviors such as early sexual initiation, substance use, violence (fighting, bullying) and suicide, and have more positive academic outcomes.1,4–10 However, disruptions to school operations during the COVID-19 pandemic have posed many challenges to schools, including transitions between face-to-face and virtual learning platforms, and fewer opportunities for students and teachers to interact and build relationships with one another and their peers. Yet, many teachers and school administrators continue to seek ways to strengthen and re-establish a sense of connectedness among students and between students and adults in school in the context of both virtual and face-to-face classroom learning environments.11

School connectedness is the belief held by students that adults and peers in the school care about their learning as well as about them as individuals.12 Students’ connection to school is fostered by the policies, routines, and practices within the school environment.12,13 School environments that have been associated with school connectedness have high academic expectations coupled with strong teacher support, foster positive and respectful relationships among adults and students, and are described as places that are both physically and emotionally safe.14,15

Well-managed classrooms that incorporate positive behavior management strategies are one way that teachers and other school staff can build school connectedness.16,17 Classroom management is a process that teachers and schools use to create positive classroom environments in face-to-face or virtual learning modes. Classroom management includes teacher- and student-led actions to support academic and social-emotional learning among all students18 and is a central aspect of quality teaching.19 A considerable body of research spanning decades has investigated the importance of effectively managed classrooms as well as the strategies that are more likely to support effectiveness.20–22 Classrooms that are effectively managed facilitate learning by maximizing student participation, promoting positive behavior, preventing disruptions, and establishing a safe and supportive environment.23,24

While previous research suggests that classroom management can play an important role in supporting school connectedness, to date guidance for teachers and other school staff on specific classroom management approaches, skills, and strategies that can foster school connectedness among K-12 students has yet to be collected in an empirically informed resource. This narrative review aims to address this gap and support the efforts of schools to prioritize implementation of evidence-based programming and professional development to promote school connectedness.

METHODS

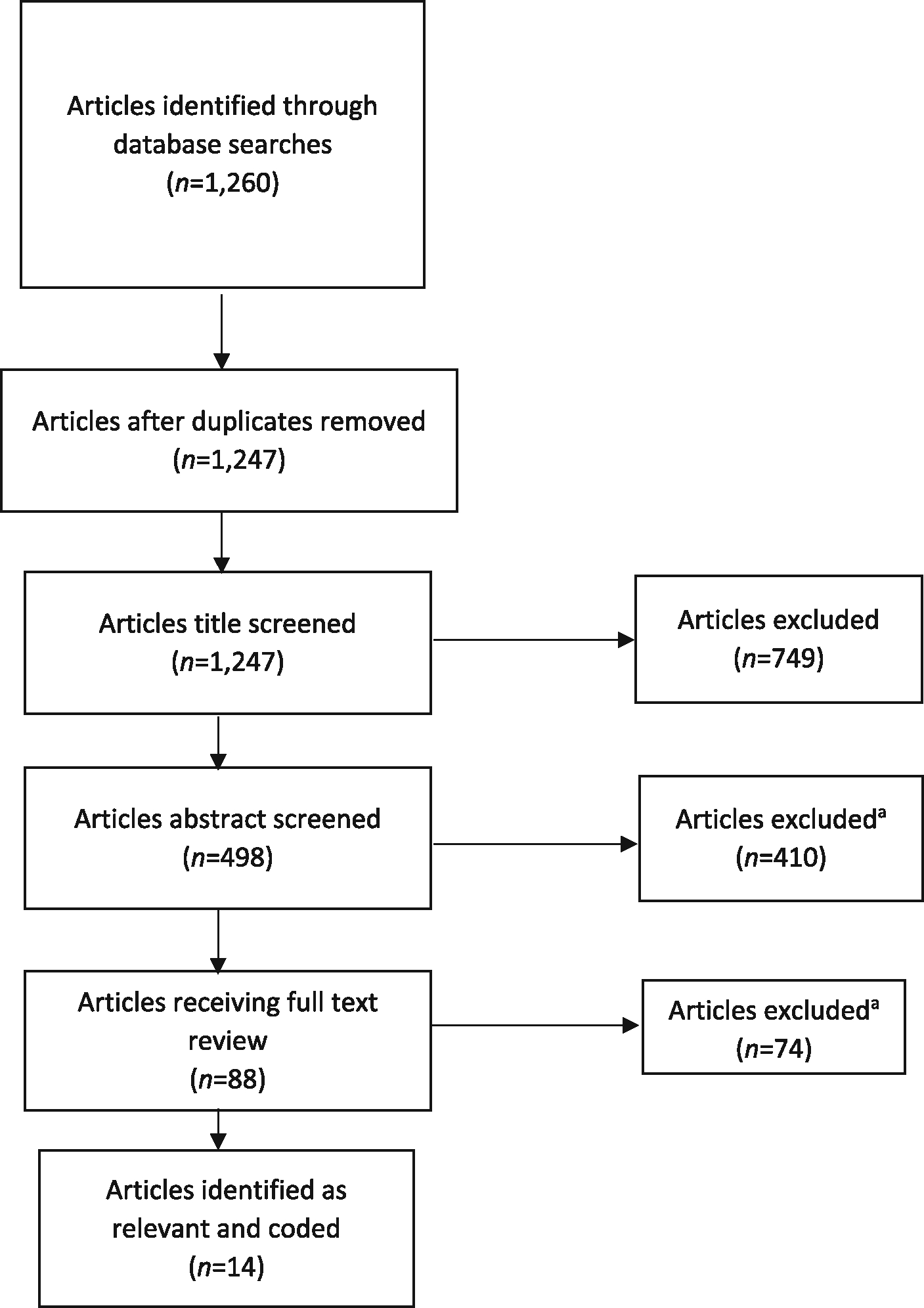

We conducted a systematic search of peer-reviewed literature to identify classroom management approaches that have been empirically tied to school connectedness-related outcomes in K-12 school settings. We limited articles to those that reported on US-based research and were published in English from January 2010 through December 2019. After screening and review of 1260 articles, we identified 14 that met inclusion criteria and specifically used quantitative methods to investigate associations between specific classroom management skills and school connectedness. Two of the authors (N.J.W. and J.M.V.V.) reviewed these articles and systematically abstracted information on classroom management skills and the empirical associations with school connectedness outcomes. Both authors reviewed and coded articles independently, and then met to address discrepancies and reach consensus. Classroom management skills and strategies that were positively and significantly (p < .05) associated with a school connectedness outcome were identified. Using an inductive process,25 skills and strategies that were significantly associated with school connectedness were grouped into broader categories of classroom management approaches based on common underlying themes (see Table 1 for more details on literature review search strategy and terms, and Figure 1 for inclusion criteria and flowchart of articles identified, screened, and included in the literature review).

Table 1.

Classroom Management and School Connectedness Literature Review Search Strategy and Terms

| Sources | ERIC; PubMed |

|---|---|

| Dates | 2010–2019 |

| Languages | English |

| Countries | United States |

| Search Terms | active supervision OR behavior contracting OR behavior management OR behavioral management OR behavior support OR class design OR class discipline OR class expectation OR class layout OR class management OR class organization OR class environment OR class routine OR class rule OR class structure OR classroom arrangement OR classroom design OR classroom discipline OR classroom climate OR classroom expectation OR classroom layout OR classroom management OR class organization OR classroom organization OR classroom environment OR classroom routine OR classroom rule OR classroom structure OR classroom technique OR discipline OR discipline gap OR disciplinary intervention OR positive classroom OR positive reinforcement OR negative reinforcement OR specific praise OR student behavior OR student engagement OR student socialization OR task engagement OR teacher behavior OR teacher beliefs OR teacher expectation OR teacher feedback OR teacher performance OR teacher praise OR teaching practices OR teacher routine OR teacher rule OR teacher strategy OR teacher strategies OR tools for teaching OR problem kid problem solver OR conscious discipline OR Jensen learning OR kidskan OR intervention central OR teach like a champion OR good behavior game OR positive behavioral interventions and supports OR responsive classroom OR champs OR tribes learning community OR tough kid toolbox OR second step OR restorative approach OR restorative justice OR restorative practices |

| AND | |

| caring teacher OR engaged teacher OR supportive teacher OR trusted teacher OR school belonging OR school connectedness OR belonging to school OR school attachment OR school affiliation OR student likes school OR school bonding OR school identification OR school membership OR school bond OR school connection OR school involvement OR school engagement OR school acceptance OR [community AND school] OR [social capital AND school] OR [belongingness AND school] OR [relatedness AND school] OR student-teacher relationship OR teacher acceptance OR teacher attachment OR teacher bond OR teacher connectedness OR teacher connection OR teacher fairness OR teacher relationship OR teacher support |

Figure 1. Flowchart Showing the Article Selection Process, Including Number of Articles Screened, Assessed for Eligibility, and Included in the Review and Reasons for Exclusion.

aInclusion criteria: peer-reviewed journal article; publication date of 2010–2019; published in English; study conducted in the United States; quantitative analysis; study investigated an association between classroom management and school connectedness.

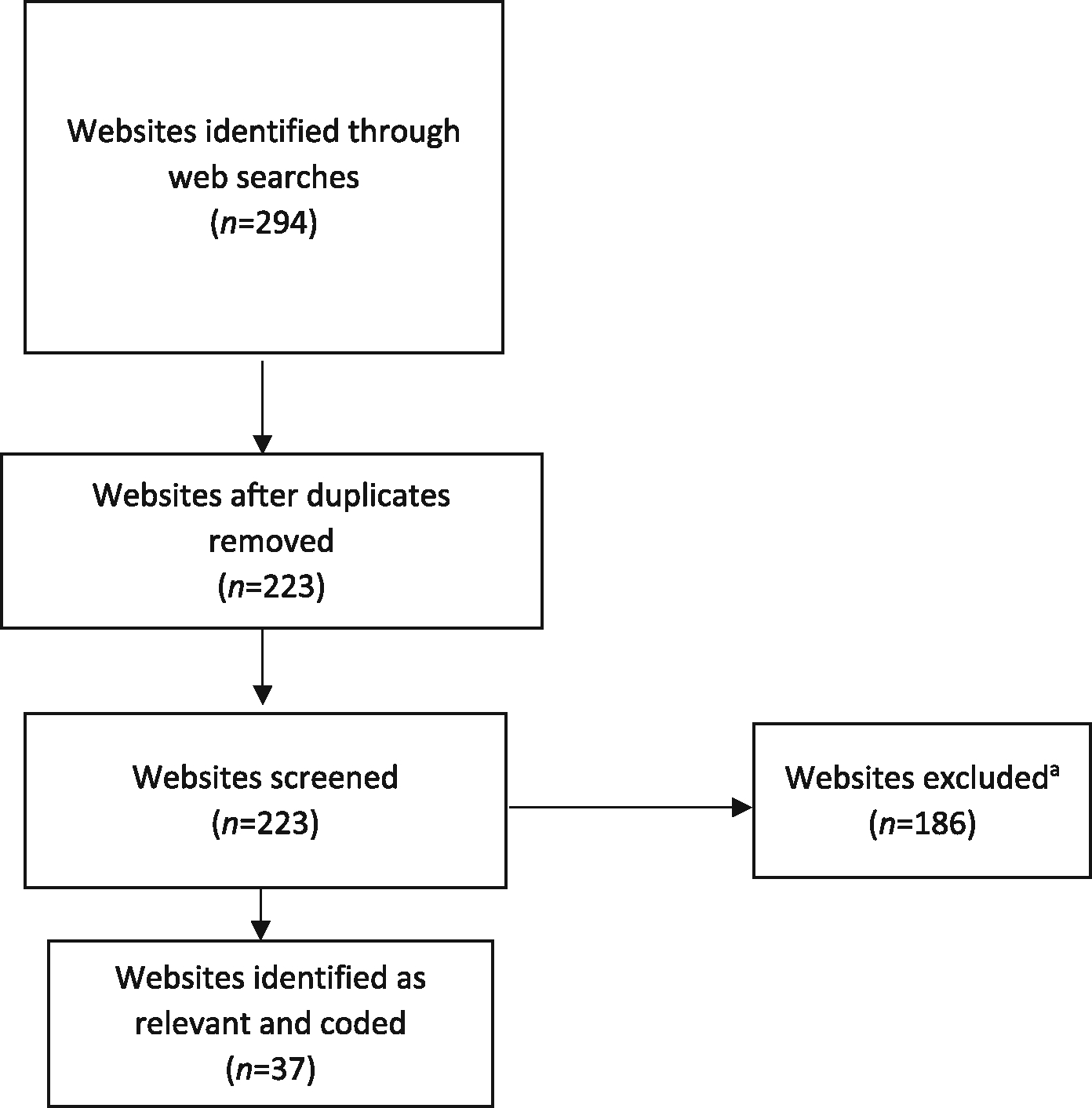

We also conducted a systematically guided web content review to identify additional classroom management strategies for applying the skills identified in the literature review (see Table 3). The web content review supplements the findings from the literature review to provide ways to make the empirically identified classroom management approaches and skills actionable for teachers and school staff. Given the increase in virtual learning resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic, we searched for and included classroom management strategies that could be applied in face-to-face or virtual learning settings. The web search was conducted in January 2021. Only strategies described on websites developed by organizations in the United States that had (1) a mission to promote education or health, (2) an explicit focus on K-12 schools, and (3) provided free, open-access resources to educators were included in the review to ensure strategies are accessible and have been reviewed by education professionals. Two hundred and twenty-three websites were screened, and 37 were reviewed and coded following a systematic information abstraction process (Table 2 describes search strategy and terms. Figure 2 represents flow of inclusion).

Table 3.

Classroom Management Approaches and Skills Linked to School Connectedness and Strategies for Application in the Classroom

| Approaches and Skills* | Strategies for Application in Classrooms† |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Teacher caring and support | |

| Showing that teachers and school staff care26–30 | • Establish regular check-ins with students, either virtually or in person.30,31 |

| • Use worksheets and written prompts that enable students to share information about their interests, goals and other student-specific information, such as preferred name and pronouns.32 | |

| Demonstrating willingness to provide extra help26,27,29 | • Establish a tracking system for students to record progress on missed or remediated work, re-assess deadlines, or break tasks into small chunks that can be done over time.26 • Use the “number three rule” to monitor student engagement. Ifa student has been disengaged from 3 activities in a row, reach out to them with an individual conversation, message, or phone call to check in.33 |

| Ensuring students are being treated fairly29 | • Establish systems, such as index cards or popsicle sticks to keep track of who has been called on during class discussions,34 to ensure students have opportunities to regularly engage in class in positive ways. • Build awareness of unintentional biases through trainings and professional development activities and invite an observer to provide feedback on class practices.34 |

| Finding ways to include topics that students want to talk about26 | • Solicit requests from students on what they would like to learn in class. Use “exit tickets” for students to write down questions and topics to discuss in future classes.35 |

| Listening and being responsive to students’ ideas and input27–29,36,37 | • Provide opportunities for students to choose reading or course materials from a number of options.38 |

| • Ask for student feedback about course materials, and make adjustments based on students’ input when possible.38 | |

| Creating opportunities for positive interactions28,36,39 | • Maintain a “5-to-1 ratio” of positive to negative interactions with students, providing students with frequent encouragement and positive attention, reinforcement, or rewards for behaviors.39 |

| Practicing restorative communication39 | • Guide students in restorative practices when challenges arise—letting go of previous negative events; taking ownership for problems (when applicable); validating feelings of others; problem solving collaboratively; expressing care by separating the deed from the doer.39 |

| Peer connection and support | |

| Encouraging students to learn more about one another26,27,40 | • Set up time in class for informal discussions between students41 and incorporate activities that enable students to ask and learn about one another.41,42 |

| Providing opportunities for students to interact with one another in fun ways26,27,40 | • Keep whole-group lessons or teacher-led instruction short (e.g., 10–20 minutes) and focus most class time on activities that enable students to work together.43 |

| • Create an online space where students can connect informally or create an online “student lounge” discussion board.44 | |

| Prioritizing assignments that enable students to work together26,27 | • Incorporate collaborative projects (eg, project-based learning) into the curriculum to enable the entire class and groups of students to work together.45 • Use technology platforms to support student collaboration on assignments and activities with students outside of their immediate community to expand their social networks and expose them to perspectives they may not otherwise encounter.46 |

| Promoting expectations that students help one another ifa peer does not understand something27 | • Use student responses to formative assessments to group students into teams. Teams discuss key topics or questions about content. Each team needs at least one student with afirm understanding of the topic.47 |

| Promoting expectations that students respect and listen to one another27,48 | • Model respect for students’ backgrounds and identities and set clear and explicit expectations around inclusion to ensure that all backgrounds, identities, abilities, and interests are respected and honored in the classroom.49 • Include classroom activities that provide students with opportunities to practice and improve listening and communication skills, which can foster an environment where students respect and listen to one another.50 • Seek out resources and professional development opportunities that focus on strengthening skills for promoting diversity and inclusion in the classroom.49 |

| Student autonomy and empowerment | |

| Providing students with opportunities to help make decisions about class rules26,48 | • Include students in the process of creating class rules, expectations, and agreements. Revisit these regularly to discuss what is working and what may need modification.38 |

| Asking students what they want to learn about26,37 | • Use brief surveys or polls (in person or virtually) or group brainstorming sessions to ask students for their input on how class time is spent, including content covered, mode of instruction, and classroom structure.51 • Adapt lessons, activities, and assignments, as possible, to reflect topics that students have indicated interests them.48 |

| Providing students with opportunities to lead in class48,52 | • Invite students to lead classroom discussions or group-based activities.38 |

| • Incorporate peer-to-peer teaching and reteaching into lessons. Ask students to choose a topic or concept that has been covered in class to re-teach to peers in smaller groups.38 | |

| Allowing students to choose how to complete projects and assignments37,48,52 | • Allow students to select assignments or assessment formats from a menu of different options.38 |

| • Ask students to keep a class journal and reflect each week on what has been going well, what has not, and what they might try differently the following week.35 | |

| Management of classroom social dynamics | |

| Observing and noting student social dynamics | • Identify which students appear to be friends and which do not, noticing students who may appear socially isolated from peers.53 • Use regular check-ins with students to learn more about student social dynamics and students’ sense of connectedness to their peers.30,31 |

| Structuring the classroom environment so that social status is less relevant53 | • Divide the class into smaller groups or “breakout rooms” to encourage interaction and collaboration.41,50 |

| Promoting some degree of balance in social status across students53 | • Identify strengths and interests of students and create opportunities for students to apply, share, and be recognized for these in class.53,54 |

| Creating opportunities for students who appear isolated to develop new friendships53 | • Pair students who may share similar interests to work together on class activities and assignments, considering social dynamics and the needs of students who may appear to be socially isolated from peers.55 |

| • Work with the school counselor and other support staff to establish a social skills group for students who struggle with social interactions, which can provide students with an opportunity to connect with others, talk about social challenges, and practice social skills.53 | |

| Taking clear steps to counter-act bullying, including discriminatory, prejudicial or harmful speech and behaviors56 | • Address harmful speech and behaviors immediately (a) quickly name the issue, (b) re-state expectations, (c) provide an opportunity for the students to engage in a positive interaction, and (d) give positive feedback. Provide information to counteract misunderstanding and reinforce a sense of community and respect, especially if a situation reflects a lack of understanding or bias.57 |

| Teacher expectations | |

| Communicating to students that teachers believe they can do well in class37 | • Demonstrate confidence in each students’ ability to succeed, hold students accountable if they do not put in the effort required to do well in class, but also let them know that teachers are there for support.58 |

| Communicating to students that teachers believe they have the abilities to perform to their potential37 | • Encourage students to set personal goals for things they want to achieve (socially, civically, academically) during the semester or school year, and periodically check in with them on their progress.38 |

| Behavior management | |

| Giving students clear instructions about how to do their work26 | • Keep consistent routines and provide clear procedures for completing class assignments, turning in homework, and working in groups.57,58 |

| Addressing problematic behavior when it occurs26,53 | • Create positive classroom roles for students, such as leading an activity, that align with their strengths and interests.53 |

| • Be mindful of how implicit biases may lead to stereotyping and unfair disciplinary practices, particularly for racial and ethnic minority students who experience disproportionately negative disciplinary actions.59 | |

| • Incorporate use of digital tools or applications that provide students with immediate behavioral feedback and reinforcement.60 | |

| Enforcing class rules consistently26 | • Reinforce prosocial behaviors with positive feedback and enforce class rules consistently and predictably to eliminate the perception of favoritism and emphasize fairness.58 |

| Ensuring that students understand the consequences of breaking class rules26 | • Set clear, logical consequences for breaking class rules and agreements early on; making sure students always have access to the rules and consequences; and reviewing these rules and consequences periodically, as needed.58 |

| • Be mindful of the difference between logical consequences linked to students’ behavior and punishment focused on short-term compliance only.61 | |

Classroom management approaches and skills were identified from a systematic search of peer-reviewed, quantitative studies and have been positively associated with school connectedness-related outcomes in K-12 school settings.

Strategies to support classroom management approaches and skills were identified from the literature review mentioned above as well as a systematically guided web content review using Google with the following search terms: Classroom management, Classroom discipline, Classroom structure, PBIS, and COVID, Pandemic, Virtual, 2020. Web searches were conducted using “incognito” browser functions to limit personalized results. English language websites from the first 2 pages of each search term combination were reviewed.

Table 2.

Classroom Management and School Connectedness Web Content Review Search Strategy and Terms

| Sources | Google*† |

| Languages | English |

| Countries | United States |

| Search Terms | Classroom management |

| Classroom discipline | |

| Classroom structure | |

| PBIS | |

| and | |

| COVID | |

| Pandemic | |

| Virtual | |

| 2020 |

Web searches were conducted using “incognito” browser functions to limit personalized results.

Websites from the first 2 pages of each search term combination were reviewed.

Figure 2. Flowchart Showing the Web Content Selection Process, Including Number of Websites Screened, Assessed for Eligibility, and Included in the Review and Reasons for Exclusion.

aInclusion criteria: website operated by an organization in the United States; organization focused on promoting health and/or education; organization focused on K-12 schools; website provides free, open-access resources to educators; website includes content about classroom management; website includes a focus on the context of the COVID-19 pandemic (eg, virtual learning approaches); website includes concrete and actionable recommendations for practice.

FINDINGS

From the literature review, we identified 6 inductively derived categories of classroom management approaches associated with improved school connectedness among students:(1) teacher caring and support, (2) peer connection and support, (3) student autonomy and empowerment,(4) management of classroom social dynamics, (5) teacher expectations, and (6) behavior management.

In the sections that follow, we summarize literature review findings on each approach and list the classroom management skills that were associated with school connectedness. We also summarize specific strategies for applying these classroom management approaches and skills that were identified through the literature and web content reviews (a comprehensive list of literature review and web content review findings can also be found in Tables S1 and S2, respectively and a summary of the findings listed in the sections below can be found in Table 3).

Teacher Caring and Support

Literature review findings indicate that students who believe their teachers build strong, positive relationships with them and show that they care about them report feeling higher levels of connectedness to school and their peers.26 For example, Acosta et al. found that in a sample of sixth and seventh graders, students reported feeling more connected to both their school and their peers when they felt that their teachers went out of their way to help students; made time to talk about the things students wanted to talk about; helped students organize their work and catch up when they return from an absence; and took a personal interest in students.26 Supportive teacher behaviors such as going out of the way to help students was also found to be associated with students reporting higher levels of school satisfaction and engagement.27,28

Based on these literature review findings, we identified 7 skills related to teacher caring and support that were linked to school connectedness: showing students that teachers and school staff care about them as people and are interested in their well-being26–29; demonstrating willingness to provide extra help to students when they need it26,27,29; ensuring that students feel they are being treated fairly29; finding ways to include topics that students want to talk about26; listening and being responsive to students’ ideas and input27–29; creating opportunities for positive interactions with students30,39; and practicing restorative communication (restorative communication practices include teachers letting go of the previous event, taking ownership for the problem, validating the student’s feelings, collaboratively problem solving to identify a mutually agreed-upon solution, and expressing caring by separating the deed from the doer).39

From the literature review and review of web content, numerous classroom-based strategies were identified that may support teachers in applying these skills. These include establishing a system for regular student check-ins either in person or virtually,30,31 providing students with frequent encouragement,39 asking students for their feedback on course materials and lessons,38 and making adjustments to the class based on students’ feedback38 (see Table 3 for additional strategies linked to each skill).

Peer Connection and Support

Students who report feeling connected to, supported by, and respected by their peers demonstrate higher levels of engagement in school27,40,48 and report feeling more connected to their school.26 In the same study mentioned previously, Acosta et al. found that students reported higher levels of school connectedness when they and their peers got to know each other well in classes; were very interested in getting to know other students; reported that they enjoyed doing things with each other in school activities; and reported that they enjoyed working together on projects in classes.26

We identified 5 skills that teachers displayed related to peer connection and support that were linked to school connectedness: encouraging students to learn more about one another26,27; providing opportunities for students to interact with one another in fun ways26,27,40; prioritizing assignments that enable students to work together26,27; promoting expectations that students help one another if a peer does not understand something26; and promoting expectations that students respect and listen to one another.48

Table 3 provides details on strategies identified through the literature and web content reviews that teachers can use to apply these skills for peer connection and support including providing activities that enable students to learn about one another,41,42 setting up opportunities for informal discussions between students either in person or virtually through chat features or discussion boards,41 and promoting activities that provide students with opportunities to practice listening and communication skills.50

Student Autonomy and Empowerment

When students feel their teachers are open to their ideas and allow them to make choices regarding their learning and schoolwork, they are more engaged in school,48,52 less disruptive in class,37 and report feeling a stronger sense of belonging and connectedness to their school.26,37 Students reported feeling more connected to their school and peers when they felt that students in their school were given the chance to help make decisions; had a say in how things work; got to help decide some of the rules; were asked by their teachers what they want to learn about; and got to help decide how class time was spent.26

Four skills related to student autonomy and empowerment were associated with school connectedness: providing students with opportunities to help make decisions about class rules26,30; asking students what they want to learn about26,37,52; providing students with opportunities to lead in class48; and allowing students to choose how to complete projects and assignments.26,30,37,48,52

Strategies identified through the literature and web content review for applying these skills to promote student autonomy and empowerment in the classroom include ensuring students participate meaningfully in the process of creating class rules, expectations, and agreements for both face-to-face and virtual learning environments38; adapting lessons, activities, and assignments to reflect what students have indicated interests them48; and allowing students to select assignments or assessment formats from a menu of different options38 (see Table 3).

Management of Classroom Social Dynamics

Students report feeling more connected to their peers,53 and higher levels of school bonding53 and belongingness56 when teachers actively take steps to manage social dynamics and promote positive interactions and friendships in class. In a study of teachers and students in first, third, and fifth grades, Gest et al. found that students reported feeling more connected to their peers and school when teachers were aware of friendship dynamics in the class (ie, who was friends with who); could identify which students were being victimized by peers in the class; took steps to mitigate status extremes between students in class; and supported isolated students.53

Literature review findings revealed 5 skills related to management of classroom social dynamics that were linked to school connectedness: observing and noting student social dynamics53; structuring the classroom environment so that social status is less relevant53; promoting some degree of balance in social status across students53; creating opportunities for students who appear isolated to develop new friendships53; and taking clear steps to counter-act bullying, including discriminatory, prejudicial or harmful speech, and behaviors.56

Findings from the literature and web content review suggest that teachers might apply these skills in managing classroom social dynamics by using regular in-person or virtual check-ins with students to learn more about student social dynamics,30,31 strategically pairing students who appear isolated with other students who may share similar interests to work together on class activities and assignments,55 and working with the school counselor to establish a social skills group for students who struggle with social interactions55 (see Table 3).

Teacher Expectations

When students believe that their teachers have high expectations for them, they are also likely to be more engaged in school and report feeling like they belong at school.37 Findings from a longitudinal study of middle school students and teachers suggest that students have a stronger sense of school belonging and higher levels of engagement in school when they believe that their teachers think they can do well in school and have the ability to perform to their potential (eg, “My teacher believes I can do well in class”).37

Two skills related to teacher expectations were associated with school connectedness: communicating to students that teachers believe they can do well in class,37 and communicating to students that teachers believe they have the abilities to perform to their potential.37

Strategies identified through the literature and web content review for applying these teacher expectation skills in the classroom include encouraging students to set personal goals for things they want to achieve (socially, civically, academically) during the semester or school year, and periodically checking in with them, in person or virtually, on their progress38 (see Table 3).

Behavior Management

Students report a stronger sense of connectedness to both their school and peers when teachers provide clear and consistent expectations for behavior in the classroom, and take actions to promote positive, prosocial behaviors.26,53 For example, Acosta et al. found that students felt more connected to their peers and school when they reported that students were given clear instructions about how to do their work in classes; teachers made a point of sticking to the rules in classes; when students are acting up in class, the teacher does something about it; and students understood consequences for breaking a rule.26

We identified 4 skills related to behavior management that were associated with school connectedness: giving students clear instructions about how to do their work26; addressing problematic behavior when it occurs26; enforcing class rules consistently26; and ensuring that students understand the consequences of breaking class rules.26

Findings from the literature and web content review suggest that teachers might apply these behavioral management skills in both face-to-face and virtual classroom settings by reinforcing prosocial behaviors with positive feedback and enforcing class rules consistently and predictably to eliminate the perception of favoritism and emphasize fairness58 (see Table 3).

DISCUSSION

Findings from this review revealed 6 empirically identified classroom management approaches associated with school connectedness: teacher caring and support, peer connection and support, student autonomy and empowerment, management of classroom social dynamics, teacher expectations, and behavior management. Students who believe their teachers build strong, positive relationships with them and show that they care about them report feeling higher levels of connectedness to school and their peers.26 Students also report feeling more connected to their school and demonstrate higher levels of school engagement when they report feeling connected to, supported by, and respected by their peers.26,27,40,48 When students report that their teachers are open to their ideas and allow them to make choices regarding their learning and schoolwork, they are more engaged in school,48,52 less disruptive in class,37 and report feeling a stronger sense of belonging and connectedness to their school.26,37 Students also report feeling more connected to their peers,53 and report higher levels of school bonding,53 and sense of belonging at school56 when teachers actively take steps to manage social dynamics and promote positive interactions and friendships in class. When students believe that their teachers have high expectations for them, they are also likely to be more engaged and report feeling like they belong at school.37 Finally, students report a stronger sense of connectedness to school and their peers when teachers provide clear and consistent expectations for behavior in the classroom, and take actions to promote positive, prosocial behaviors.26,53

Consistent with previous research, findings from this review show that classroom management is multifaceted, involving classroom structure, relationships, instructional management, and responses to appropriate and inappropriate behavior.20,62 Findings also indicate that classroom management approaches most linked to school connectedness are those that foster student autonomy and empowerment, mitigate social hierarchies and power differentials among students, prioritize positive reinforcement and restorative disciplinary practices, and emphasize equity and fairness. These approaches are consistent with emerging perspectives on building teacher capacity to facilitate effective learning environments rather than only focus on behavioral management.63

Limitations

This review is subject to several limitations. First, to ensure alignment of approaches and strategies with US school settings, only peer-reviewed English language articles published in US journals were included. Further investigation into educational research conducted internationally and in collaboration with international researchers may advance our knowledge of effective classroom practices suitable to diverse classroom settings. Second, only articles presenting quantitative findings were included to enable assessment of the empirical associations between classroom management practices and school connectedness. Qualitative research and case studies depicting innovations may highlight promising practices that merit further research. Third, empirical articles that focused on broad approaches to classroom management or measured classroom management through aggregate scales were excluded as these studies did not enable our review team to identify associations between specific classroom management practices and school connectedness outcomes. Future research may examine some of the classroom management practices included in these aggregate measures to identify additional classroom management skills and approaches that are likely to strengthen school connectedness. For example, studies using aggregate measures of classroom management indicate that instructional monitoring and support and promoting content relevance may be linked to increased school connectedness and engagement when combined with other classroom management approaches, although their direct association with school connectedness is still unknown.37,40,53,64 More research is needed on the extent to which these classroom management approaches have a direct or additive effect on connectedness when combined with other classroom management approaches.

Classroom environments that foster school connectedness have been associated with students’ positive adjustment to school and student success, especially for students at risk for negative academic outcomes.5 Future research should also explore in greater detail the ways in which classroom management can contribute to greater academic and health equity in schools. This includes studies investigating the impact of specific classroom management approaches, skills, and strategies on school connectedness outcomes among students who experience marginalization or are at disproportionate risk for negative social, emotional, and academic outcomes. It also includes research on the impact of teacher-related factors (eg, race and ethnicity, experience) and school-related factors (eg, opportunities for professional development and assessment) on classroom management practices and equitable student outcomes.

IMPLICATIONS FOR SCHOOL HEALTH POLICY, PRACTICE, AND EQUITY

Prioritizing classroom management approaches that emphasize positive reinforcement of behavior, restorative discipline and communication, development of strong, trusting relationships, and explicitly emphasize fairness has potential to promote equitable disciplinary practices in schools. It is well documented that African American and Latinx children experience a disproportionate number of discipline referrals and harsher punishments in schools for the same or similar problem behaviors as their white peers,65 and emerging evidence suggests sexual and gender minority youth also experience disproportionately harsh discipline.66 Youth who report unequal treatment in school are also more likely to perceive their school climate as negative.67 Shifting from zero tolerance practices to the implementation of classroom practices that focus on building strong, supportive, and trusting relationships has been identified as one means to help address patterns of disproportionality in exclusionary discipline as well as in overrepresentation of racial and ethnic minority youth in special education.68 Providing teachers with opportunities to build awareness and manage their own biases also has the potential to improve fairness and equity in the classroom and reduce disparities in disciplinary actions.69 Building strong, supportive, trusting relationships within the school environment may be particularly critical for students experiencing social isolation, chronic stress, or acute trauma. Classrooms that foster positive relationships, such as those implementing trauma-informed approaches, have been identified as potentially serving an important protective role against the negative effects of stress, trauma, social adversity, racial injustice, or marginalization and have been associated with more positive overall school environments, improved student attendance, higher school achievement, and more positive psychological well-being.70–73

Conclusions

This review builds upon previous research on the important role of classroom management in supporting school connectedness. Classroom management approaches that foster student autonomy and empowerment, mitigate social hierarchies and power differentials among students, prioritize positive reinforcement of behavior and restorative disciplinary practices, and emphasize equity and fairness are most critical for promoting students’ sense of connectedness and belonging at school. The findings presented here provide a more nuanced synthesis of specific classroom management skills, along with example strategies for applying these skills in classroom settings, to strengthen students’ sense of connectedness and engagement. It is our hope that these findings support teachers and other school staff by providing actionable guidance on specific classroom management approaches, skills, and strategies that can foster school connectedness among K-12 students.

Supplementary Material

Table S2: Web Content for Applying Classroom Management Skills Linked to School Connectednessa

Table S1: Literature Review Findings on Classroom Management Skills Empirically Associated With School Connectedness Outcomes in K-12 School Settings

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge Tara Cheston, Christian Citlali, Adina Cooper, Summer Hellewell, Marci Hertz, Christina Holmes, Mia Humphreys, Rachel Miller, Heather Oglesby, Valerie Sims, and Rena Subotnik for their review of and feedback on the findings presented in this paper. The findings and conclusions in this paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

All authors declare that they have no financial nor nonfinancial conflicts of interest.

Human Subjects Approval Statement

Preparation of this paper did not involve primary research or data collection involving human subjects, and therefore, no institutional review board examination or approval was required.

SUPPORTING INFORMATION

Additional supporting information may be found online in the Supporting Information section at the end of the article.

REFERENCES

- 1.Steiner RJ, Sheremenko G, Lesesne C, Dittus PJ, Sieving RE, Ethier KA. Adolescent connectedness and adult health outcomes. Pediatrics. 2019;144(1):1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kim J The quality of social relationships in schools and adult health: differential effects of student-student versus student-teacher relationships. School Psychol. 2020;36:6–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Eugene DR, Du X, Kim YK. School climate and peer victimization among adolescents: a moderated mediation model of school connectedness and parental involvement. Child Youth Serv Rev. 2021;121:105854. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Marraccini ME, Brier ZM. School connectedness and suicideal thoughts and behaviors: a systematic meta-analysis. Sch Psychol Q. 2017;32(1):5–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Niehaus K, Rudasill KM, Rakes CR. A longitudinal study of school connectedness and academic outcomes across sixth grade. J Sch Psychol. 2012;50(4):443–460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carter M, McGee R, Taylor B, Williams S. Health outcomes in adolescence: associations with family, friends and school engagement. J Adolesc. 2007;30(1):51–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Griffiths A-J, Lilles E, Furlong MJ, Sidhwa J. The relations of adolescent student engagement with troubling and high-risk behaviors. In: Handbook of Research on Student Engagement. Boston, MA: Springer; 2012:563–584. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lei H, Cui Y, Zhou W. Relationships between student engagement and academic achievement: a meta-analysis. Soc Behav Personal Int J. 2018;46(3):517–528. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lonczak HS, Abbott RD, Hawkins JD, Kosterman R, Catalano RF. Effects of the Seattle social development project on sexual behavior, pregnancy, birth, and sexually transmitted disease outcomes by age 21years. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2002;156(5):438–447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schaps E, Solomon D. The role of the school’s social environment in preventing student drug use. J Prim Prev. 2003;23(3):299–328. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kurtz H, Lloyd S, Harwin A, Chen V, Gubbay N. Student Engagement During the Pandemic: Results of a National Survey. Bethesda, MD: EdWeek Research Center; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. School connectedness: Strategies for increasing protective factors among youth; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Osher D, Bear GG, Sprague JR, Doyle W. How can we improve school discipline? Educ Res. 2010;39(1):48–58. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Blum RW. A case for school connectedness. Educ Leadersh. 2005;62(7):16–20. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Doll B, Brehm K, Zucker S. Resilient Classrooms: Creating Healthy Environments for Learning. New York, NY: Guilford Publications; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hawkins JD, Guo J, Hill KG, Battin-Pearson S, Abbott RD. Long-term effects of the Seattle social development intervention on school bonding trajectories. Appl Dev Sci. 2001;5(4):225–236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McNeely CA, Nonnemaker JM, Blum RW. Promoting school connectedness: evidence from the national longitudinal study of adolescent health. J Sch Health. 2002;72(4):138–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Evertson CM, Weinstein CS. Classroom management as a field of inquiry. In: Handbook of classroom management: Research, practice, and contemporary issues, New York, NY: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers; Vol. 3(1). 2006:16. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Greenberg J, Putman H, Walsh K. Training Our Future Teachers: Classroom Management. Revised. National Council on Teacher Quality; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Simonsen B, Fairbanks S, Briesch A, Myers D, Sugai G. Evidence-based practices in classroom management: considerations for research to practice. Educ Treat Child. 2008;31:351–380. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Oliver RM, Wehby JH, Reschly DJ. Teacher classroom management practices: effects on disruptive or aggressive student behavior. Campbell Syst Rev. 2011;7(1):1–55. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Epstein M, Atkins M, Cullinan D, Kutash K, Weaver R. Reducing behavior problems in the elementary school classroom. IES practice guide. NCEE 2008–012. What works clearinghouse. 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Korpershoek H, Harms T, de Boer H, van Kuijk M, Doolaard S. A meta-analysis of the effects of classroom management strategies and classroom management programs on students’ academic, behavioral, emotional, and motivational outcomes. Rev Educ Res. 2016;86(3):643–680. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Reinke WM, Herman KC, Sprick R. Motivational Interviewing for Effective Classroom Management: The Classroom Check-Up. New York, NY: Guilford press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 25.DeCarlo M Scientific Inquiry in Social Work. Open Social Work Education; 2018. https://open.umn.edu/opentextbooks/textbooks/591 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Acosta J, Chinman M, Ebener P, Malone PS, Phillips A, Wilks A. Understanding the relationship between perceived school climate and bullying: a mediator analysis. J Sch Violence. 2019;18(2):200–215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kearney WS, Smith PA, Maika S. Examining the impact of classroom relationships on student engagement: a multilevel analysis. J Sch Public Relat. 2014;35(1):80–102. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Buehler C, Fletcher AC, Johnston C, Weymouth BB. Perceptions of school experiences during the first semester of middle school. Sch Community J. 2015;25(2):55–83. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lee J-S. The effects of the teacher-student relationship and academic press on student engagement and academic performance. Int J Educ Res. 2012;53:330–340. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Baroody AE, Rimm-Kaufman SE, Larsen RA, Curby TW. The link between responsive classroom training and student-teacher relationship quality in the fifth grade: a study of fidelity of implementation. Sch Psychol Rev. 2014;43(1):69–85. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Prothero A How to Build Relationships with Students duringCOVID-19. Education Week. Available at: https://www.edweek.org/leadership/how-to-build-relationships-with-students-during-covid-19/2020/09. Accessed September, 2020 [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gay Lesbian Straight Education Network. Pronoun guide. Available at: https://www.glsen.org/activity/pronouns-guide-glsen. Accessed September, 2020.

- 33.Barnett A 14 tips for fine-tuning your virtual reading instruction; 2020. Available at: https://www.readinghorizons.com/blog/virtual-reading-instruction-14-tips. Accessed September, 2020.

- 34.Resilient Educator. 5 innovative elementary classroom management ideas. Available at: https://resilienteducator.com/classroom-resources/5-innovative-elementary-classroom-management-ideas/. Accessed September, 2020.

- 35.Nordegren C 3 reasons to use formative assessment in your virtual instruction- And tips on how to go about it; 2020. Available at: https://www.nwea.org/blog/2020/formative-assessment-in-virtual-instruction/. Accessed September, 2020.

- 36.Giles SM, Pankratz MM, Ringwalt C, et al. The role of teacher communicator style in the delivery of a middle school substance use prevention program. J Drug Educ. 2012;42(4):393–411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kiefer SM, Pennington S. Associations of teacher autonomy support and structure with young adolescents’ motivation, engagement, belonging, and achievement. Middle Grades Res J. 2017;11(1):29–46. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Search Institute. Building developmental relationships during the COVID-19 crisis. Available at: https://www.search-institute.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/Coronavirus-checklist-Search-Institute.pdf. Accessed September, 2020

- 39.Duong MT, Pullmann MD, Buntain-Ricklefs J, et al. Brief teacher training improves student behavior and student-teacher relationships in middle school. School Psychol. 2019;34(2):212–221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kim HY, Cappella E. Mapping the social world of classrooms: a multi-level, multi-reporter approach to social processes and behavioral engagement. Am J Community Psychol. 2016;57(1–2):20–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schwartz S Classroom routines must change. Here’s what teaching looks like under COVID-19. Education Week. Available at: https://www.edweek.org/teaching-learning/classroom-routines-must-change-heres-what-teaching-looks-like-under-covid-19/2020/08. Accessed September, 2020 [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lightner J, Tomaswick L. Active learning - think, pair, share. Kent State University Center for Teaching and Learning. Available at: http://www.kent.edu/ctl/educational-resources/active-learning-think-pair-share/ [Google Scholar]

- 43.Room to Discover. Online classroom management: Five tips for making the shift Available at: https://www.roomtodiscover.com/online-classroom-management/

- 44.Young S Classroom structure and management in your (new) online classroom. Available at: https://vhslearning.org/classroom-structure-and-management-your-new-onlineclassroom. Accessed September, 2020.

- 45.Ohio Department of Education. Student and staff well-being toolkit. Available at: http://education.ohio.gov/Topics/Reset-and-Restart/Student-and-Staff-Well-Being-Toolkit. Accessed September, 2020.

- 46.Seagle Z, Taylor J. Goodbye, long nights of lesson planning: The secrets to successful virtual co-teaching; 2016. Available at: https://www.edsurge.com/news/2016-10-13-goodbye-long-nights-of-lesson-planning-the-secrets-to-successful-virtualco-teaching. Accessed September, 2020.

- 47.Goodrich K Classroom techniques: Formative assessment idea number 2; 2012. Available at: https://www.nwea.org/blog/2012/classroom-techniques-formative-assessment-idea-number-two/. Accessed September, 2020.

- 48.Ruzek EA, Hafen CA, Allen JP, Gregory A, Mikami AY, Pianta RC. How teacher emotional support motivates students: the mediating roles of perceived peer relatedness, autonomy support, and competence. Learn Instr. 2016;42:95–103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Edutopia. Culturally responsive teaching; 2020. Available at: https://www.edutopia.org/topic/culturally-responsive-teaching. Accessed September, 2020.

- 50.Minero E 8 Strategies to Improve Participation in your Virtual Classroom. Edutopia. Available at: https://www.edutopia.org/article/8-strategies-improve-participation-your-virtualclassroom. Accessed September, 2020 [Google Scholar]

- 51.Michigan MTSS Technical Assistance Center. Classroom PBIS for online learning; 2020. Available at: https://www.scribbr.com/apa-examples/report/.Accessed September, 2020.

- 52.Hafen CA, Allen JP, Mikami AY, Gregory A, Hamre B, Pianta RC. The pivotal role of adolescent autonomy in secondary school classrooms. J Youth Adolesc. 2012;41(3):245–255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gest SD, Madill RA, Zadzora KM, Miller AM, Rodkin PC. Teacher management of elementary classroom social dynamics: associations with changes in student adjustment. J Emot Behav Disord. 2014;22(2):107–118. [Google Scholar]

- 54.World Education. The socially isolated student. Availableat: https://www.educationworld.com/a_curr/shore/shore054.shtml Accessed September, 2020.

- 55.Tucker GC. 7 Ways the Teacher Can Help your Child Make Friends. Understood. Available at: https://www.understood.org/en/school-learning/partnering-with-childs-school/working-with-childs-teacher/7-ways-the-teacher-can-help-your-child-make-friends. Accessed September, 2020 [Google Scholar]

- 56.Doumas DM, Midgett A. The effects of students’ perceptions of teachers’ antibullying behavior on bullying victimization: is sense of school belonging a mediator? J Appl Sch Psychol. 2019;35(1):37–51. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Center on Positive Behavioral Interventions and Supports. Responding to the novel coronavirus (COVID-19) outbreak through PBIS; 2020. Available at: https://www.pbis.org/resource/responding-to-the-novel-coronavirus-covid-19-outbreak-through-pbis. Accessed September, 2020.

- 58.Taylor JC. Seven classroom structures that support student relationships. Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development. Available at: http://www.ascd.org/ascd-express/vol11/1111-taylor.aspx [Google Scholar]

- 59.Skiba RJ, Arredondo MI, Williams NT. More than a metaphor: The contribution of exclusionary discipline to a school-to-prison pipeline. Equity Excellence Educ. 2014;47(4):546–564. [Google Scholar]

- 60.SchoolMint. PBIS in a virtual environment; 2020. Available at: https://schoolmint.com/pbis-in-a-virtual-environment/. Accessed September, 2020.

- 61.Responsive Classroom. Punishment vs. logical consequences; 2011. https://www.responsiveclassroom.org/punishment-vs-logical-consequences/. Accessed September, 2020.

- 62.Gable RA, Hester PH, Rock ML, Hughes KG. Back to basics: rules, praise, ignoring, and reprimands revisited. Interv Sch Clin. 2009;44(4):195–205. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Milner HR IV, Cunningham HB, Delale-O’Connor L, Kestenberg EG. “These Kids Are out of Control”: Why we Must Reimagine “Classroom Management” for Equity. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Cappella E, Hamre BK, Kim HY, et al. Teacher consultation and coaching within mental health practice: classroom and child effects in urban elementary schools. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2012;80(4):597–610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Skiba RJ, Horner RH, Chung C-G, Rausch MK, May SL, Tobin T. Race is not neutral: a national investigation of African American and Latino disproportionality in school discipline. Sch Psychol Rev. 2011;40(1):85–107. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Snapp SD, Hoenig JM, Fields A, Russell ST. Messy, butch, and queer: LGBTQ youth and the school-to-prison pipeline. J Adolesc Res. 2015;30(1):57–82. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Pena-Shaff JB, Bessette-Symons B, Tate M, Fingerhut J. Racial and ethnic differences in high school students’ perceptions of school climate and disciplinary practices. Race Ethn Educ. 2019;22(2):269–284. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Skiba RJ, Simmons AB, Ritter S, et al. Achieving equity in special education: history, status, and current challenges. Except Child. 2008;74(3):264–288. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Starck JG, Riddle T, Sinclair S, Warikoo N. Teachers are people too: examining the racial bias of teachers compared to other American adults. Educ Res. 2020;49(4):273–284. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Chafouleas SM, Johnson AH, Overstreet S, Santos NM. Towarda blueprint for trauma-informed service delivery in schools. Sch Ment Heal. 2016;8(1):144–162. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Thomas MS, Crosby S, Vanderhaar J. Trauma-informed practices in schools across two decades: an interdisciplinary review of research. Rev Res Educ. 2019;43(1):422–452. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Thapa A, Cohen J, Guffey S, Higgins-D’Alessandro A. A review of school climate research. Rev Educ Res. 2013;83(3):357–385. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kataoka SH, Vona P, Acuna A, et al. Applying a trauma informed school systems approach: examples from school community-academic partnerships. Ethn Dis. 2018;28(Suppl 2): 417–426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S2: Web Content for Applying Classroom Management Skills Linked to School Connectednessa

Table S1: Literature Review Findings on Classroom Management Skills Empirically Associated With School Connectedness Outcomes in K-12 School Settings