Abstract

Background:

As of September 2022, there was no globally recommended set of core data elements for use in multiple sclerosis (MS) healthcare and research. As a result, data harmonisation across observational data sources and scientific collaboration is limited.

Objectives:

To define and agree upon a core dataset for real-world data (RWD) in MS from observational registries and cohorts.

Methods:

A three-phase process approach was conducted combining a landscaping exercise with dedicated discussions within a global multi-stakeholder task force consisting of 20 experts in the field of MS and its RWD to define the Core Dataset.

Results:

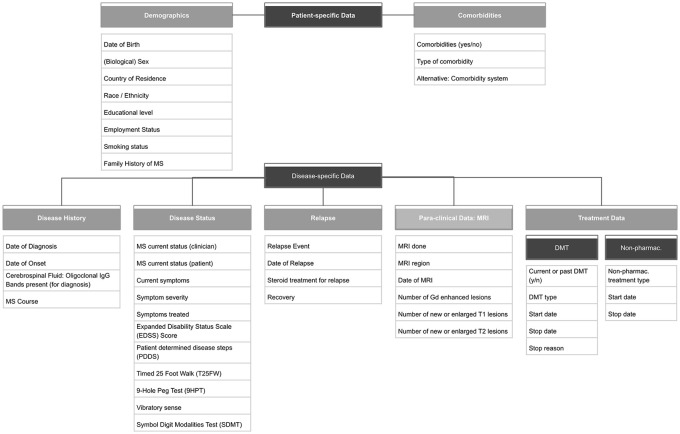

A core dataset for MS consisting of 44 variables in eight categories was translated into a data dictionary that has been published and disseminated for emerging and existing registries and cohorts to use. Categories include variables on demographics and comorbidities (patient-specific data), disease history, disease status, relapses, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and treatment data (disease-specific data).

Conclusion:

The MS Data Alliance Core Dataset guides emerging registries in their dataset definitions and speeds up and supports harmonisation across registries and initiatives. The straight-forward, time-efficient process using a dedicated global multi-stakeholder task force has proven to be effective to define a concise core dataset.

Keywords: Core dataset, harmonisation, real-world data, multiple sclerosis, registry, database

Introduction

There is an increased awareness of the importance of utilising real-world data (RWD) in multiple sclerosis (MS) with the number of RWD collection efforts growing around the world.1–3 However, RWD collection efforts lack standardisation across sources especially due to heterogeneous content and the semantic and syntactic representation (the ‘what’ and ‘how’ of data collection). 4 Different stakeholders, such as clinicians, researchers, or regulators, have a particular interest in and need for alignment (‘harmonisation’) in RWD collection in MS. This would help facilitate collaboration between MS registries, especially when striving towards large-scale global collaborative efforts.1,3

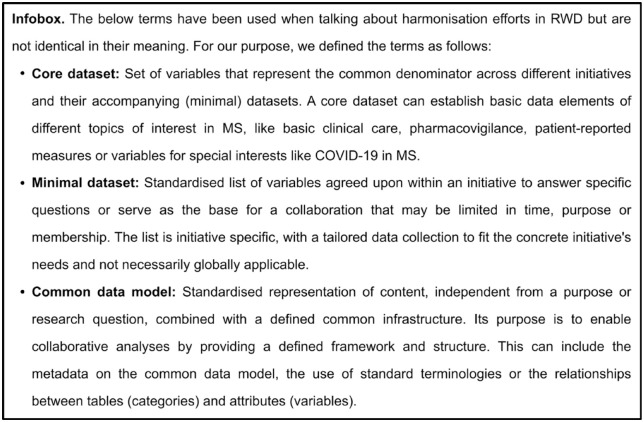

Several initiatives in the field of MS have already faced the challenge of harmonising datasets for their research purposes, which successfully enabled collaborative RWD-driven insights.5–9 For example, the Big MS Data (BMSD) network agreed upon a minimal dataset for their network and research questions dealing with post-authorisation safety studies in MS. 10 In July 2017, the European Medicines Agency (EMA) held an MS workshop in the framework of their patient registries initiative for promoting the use of RWD for regulatory purposes. Different stakeholders discussed three aspects of real-world MS data, one being the establishment of core data elements in the data collection of MS registries. Although these initiatives working towards harmonisation in RWD in MS were a big step in the right direction, they failed to communicate the developed and used minimal or core datasets (see Figure 1 for differentiation) effectively. Also it remained unclear whether there was any alignment with more generic initiatives (not MS-specific) or inter-stakeholder validation for the development of used datasets. The published core data elements from EMA 11 could serve as a ‘core dataset’ for MS. However, as it was not inside the scope of the workshop, the proposal lacked detailed information (e.g. the operational definition of the format of the specific data elements).

Figure 1.

For a better understanding, we defined ‘core dataset’, ‘minimal dataset’, and ‘common data model’ for the use in our paper and process of defining the MSDA core dataset.

The MS Data Alliance (MSDA) is a global multi-stakeholder collaboration aiming to develop tools to reduce the level of heterogeneity among real-world MS data sources and promote timely alignment for data harmonisation across data sources. 12 The MSDA has successfully led global data harmonisation activities throughout the COVID-19 pandemic with the MS Global Data Sharing Initiative (GDSI) and its corresponding global recommendations for data collection on COVID-19 in people with MS. 13 Within the GDSI, the MSDA, MS International Federation and a global data task force established recommendations for a ‘COVID-19 in MS core dataset’ to enable a harmonised approach to the challenge of building a global data network. These recommendations were published 13 and provided on the MSDA website 14 for prospective and retrospective alignment of participating registries and databases to promote joint analyses. This inspired the MSDA to stimulate the definition and agreement on a standardised core dataset in MS (called ‘MSDA Core Dataset’, ‘Core Dataset’) to further strengthen and speed up collaboration to generate evidence from RWD.

The aim of this paper is to present the process and outcome of defining a core dataset for RWD in MS using a global multi-stakeholder task force.

Materials and methods

Workflow of the Core Dataset definition and agreement

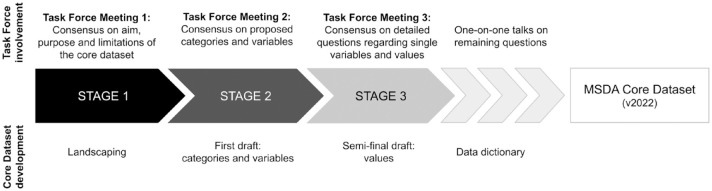

The definition and approval of this core dataset in MS was guided by a multi-stakeholder global task force. The task force consisted of 20 experts and key opinion leaders in the field of RWD in MS, including clinicians, data custodians, and leads of MS registries and cohorts, a patient organisation, pharmaceutical industry representatives, and regulatory agencies. The range of different stakeholders enabled a rich diversity of opinions and experiences contributing to in-depth discussions on the core variables in MS. The experts, with representatives from North and South America, North-Eastern Africa, Europe, and Oceania, were involved in MSDA activities and were chosen to participate in the task force. The process of landscaping, discussing, reviewing, and agreeing upon a core dataset was orchestrated and coordinated by the MSDA. A workflow was defined prior to initiating the task force to ensure the process was as efficient as possible, while keeping the time and resources requested from the task force members feasible (see Figure 2). With regards to communication, we informed the members of the task force about steps or results. The key messages from the meetings were circulated after each meeting via mail. The Core Dataset was transparently shared with the task force together with the manuscript. The final agreement was based on the absence of contrary views of the circulated versions of the Core Dataset.

Figure 2.

The task force meetings represented three stages of the definition and agreement workflow: The process, estimated workload, and expected engagement were shared with the task force in advance, to ensure transparency and effectiveness. The workflow of the definition and consensus process of the task force was divided into three consecutive meetings held within 3 months (June to September 2022). (1) Pre-stage of the landscaping (consensus on aim, purpose and limitations of the core dataset), (2) Consensus building on the landscaping-based proposed categories and variables, and (3) Addressing and decision-making focussed on open questions regarding single variables and values. After each stage, the experiences and input shared from the task force members were incorporated into the design of the Core Dataset. In the end, the Core Dataset data dictionary was finished and shared with the task force for final approval.

Landscaping

The landscaping process for Core Dataset development aimed at identifying relevant initiatives and material around the topic of minimal and core data elements in MS. Three pillars were identified: (1) an exploratory literature scan, (2) recommended material from the task force, and (3) metadata from the MSDA Catalogue, 4 a web-based platform which was launched in 2019 and allows end-users to browse metadata profiles of MS RWD cohorts.

The literature scan and recommended material focussed on two categories: (a) MS-specific recommendations and publications on common data elements and (b) examples of MS registries with available information on their datasets. Literature was identified using PubMed and Google Scholar with specific search terms ([‘core dataset’ OR ‘minimum dataset’ OR ‘minimal dataset’] + ‘multiple sclerosis’).

The recommended material from the task force members was provided electronically and included additional publications on common data elements as well as the MS registry dataset examples.

Metadata from the MSDA Catalogue was accessed internally. It was exported and further processed to serve as a look-up and validation source.

Comparison of available sources and the drafting process

The suggested core data elements and wish list items of the referred EMA workshop were used for comparison for the mapping of available datasets. Although this list has not been validated or approved by experts beyond the workshop itself to be able to act as a ‘gold standard’, it was chosen to enable a pragmatic and feasible approach for an initial Core Dataset definition. The available reference recommendations, publications, or dataset descriptions were checked for EMA variables. Variables that were collected by references but were not part of the EMA core data elements were not included for comparison. The resulting comparison table led to the selection of category and variable suggestions for the first draft of the Core Dataset. Some variables were added based on proposals during the task force meetings and thereon-based discussions. This added to the eventual final Core Dataset v2022 over the course of the three task force meetings and the subsequent finishing (see Figure 2). Determination of the variables’ values followed the definition of the categories and variables. As it is the aim of the Core Dataset to be as standardised and harmonised as possible, the values of the identified and defined variables had to fulfil certain requirements. If available and applicable, standards were used, for example, for date (ISO-8601) or educational level (International Standard Classification of Education (ISCED)). If no standard existed, values were chosen for discussion that were already established or used by one or more registries, with the data dictionary of MSBase 15 as a leading coding model due to its wide global application.

Results

Scope of the Core Dataset: consensus on aim, purpose, and limitations

The consensus of the task force was that the Core Dataset should serve as a guideline for existing and emerging registries and databases to reduce heterogeneity, provide coverage of the key data elements for care in MS and ensure feasibility of data collection. Twelve of the 20 experts of the task force were clinicians and data custodians with year- and even decade-long expertise in collection of such data and a proven scientific track record which enabled a solid feasibility assessment. The Core Dataset represents the common denominator across initiatives and experts’ input as a list of recurring variables and aims to be research question agnostic. Indeed, the Core Dataset does not aspire to enable every possible research question since a have-it-all core dataset for MS would be impossible to achieve (as for e.g. sustainability and feasibility). The decision was made to focus on a core dataset that can be augmented in future revisions and (local) adaptations regarding what (variables) and how (values, formats) to collect. Application guidelines, for example, focussing on frequency of data collection, are out of scope for the current version of the Core Dataset, but conceivable for future work.

Landscaping: identify existing (and available) sources on minimal/core datasets

Our literature scan performed in July 2022 found little published information in the field of MS-specific recommendations and publications on data elements. The literature scan on PubMed did not deliver any relevant results. Google Scholar delivered a broader picture for the chosen search terms but no publication that dealt exactly with the topic of any minimal or core dataset in MS could be found. Broadening the search term to ‘real-world data’ and ‘multiple sclerosis’ delivered a larger amount but mostly single study publications with a specific use case (mostly a certain treatment) where RWD was used. Neither dataset definition processes nor the datasets themselves were included in these publications. The scan for relevant material based on prior knowledge of MS initiatives that have published their datasets resulted only in the publication about the EMA MS patient registry workshop. 11 The additional material from task force members helped identifying initiatives and datasets that were not publicly available.

The National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS), 16 as part of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), has defined ‘Common Data Elements’ (CDE) for neuroscientific clinical research, with MS being one of the neurological disorders. This very extensive list of variables aims to define data collection standards for neuroscientific clinical research across NINDS-funded studies in the United States. This list was included in the comparison with the EMA core data elements to identify common data elements for MS RWD.

A few publications were identified that discuss the importance of using standardised/harmonised datasets for RWD use in MS1,3 or attempt to find a ‘common language of MS data elements’. 17 The latter study compared two registry data collections with regards to the used data elements in both data collection software and gave a list of recommendations based on these two comparators. This list of recommendations was also compared to the EMA list.

Similar to the effort to find recommendations on CDE in MS, the search for publicly accessible data dictionaries from MS registries was challenging. Some registries have published their dataset description or sent them to the MSDA for the purpose of the landscaping for the Core Dataset. For example, MSBase, 15 NARCOMS,18,19 and the German MS registry 20 have published their dataset descriptions online. The dataset descriptions of the Egyptian Registry, iConquerMS,21,22 and the Canadian Multiple Sclerosis Monitoring System (not active anymore) were provided to the MSDA.

Given that a lot of analyses in MS require derived variables, there’s also a need to have data specification documents (‘data dictionaries’) of observational MS data sources available. The publication of established datasets would be, beyond the definition of a minimal or core dataset, an important step to promote a common understanding across MS RWD sources and facilitate harmonisation.

The Core Dataset: categories, variables, values, and data dictionary

The task force discussions led to the agreement on 8 categories and 44 (plus date of visit) variables for the Core Dataset v2022 (see Figure 3). The discussions consisted of a presentation of a certain preparatory work (landscaping results, draft of Core Dataset variables, draft of data dictionary) and an inter-group debate from which the key reflections and decisions were recorded and shared with the task force afterwards. The inclusion and exclusion of variables, as well as the approach to appoint their values, were the main topics of the discussions. Excluded variables and value decisions are provided in the ‘Discussion’ section. After agreeing upon the categories, variables, and values, the data dictionary of the Core Dataset was finalised. A detailed data dictionary (see Table 1) was developed to facilitate the implementation of the dataset and to promote the harmonisation across data sources not only through content but also through the specification of the structure and syntax. To ensure alignment between the MSDA Core Dataset and important non-MS-specific initiatives, it was decided to add a disease or data source independent standard into the data dictionary of the Core Dataset: SNOMED CT (Systematised Nomenclature of Medicine Clinical Terms). SNOMED CT is, as an international validated multilingual healthcare terminology, broadly used across the globe. With its more than 358 000 standardised concepts (as of 16 May 2023), 23 it enables a harmonised and consistent representation of clinical content. SNOMED CT is mapped to other healthcare standards as well as used as a leading standard in common data models (CDM, see Figure 1). It can be an additional benefit for registries, for example, by being used for health practitioner databases or patient-reported registries, where variables can be adapted to questions to suit the needs of the circumstances.

Figure 3.

Core Dataset categories and variables: The 8 categories of the core dataset (demographic data, disease history, disease status, relapses, MRI, comorbidities, disease-modifying treatments, non-pharmaceutical treatments) with their respective 44 variables as they were agreed-upon during the task force meetings.

Table 1.

Core Dataset data dictionary to specify the content, structure, and syntax of the collected variables.

| Documented by | Name | Variable_name | Collection time | Data format | SNOMED term | SNOMED code | Value(s) | Value_name | SNOMED term | SNOMED code |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | Date of visit/reporting date (for PRO) | date_visit | FV, FU | YYYY-MM-DD | Date of visit (observable entity) | 406543005 | – | – | – | – |

| Demographic data | ||||||||||

| B | Date of birth | date_birth | FV | YYYY-MM-DD | Date of birth (observable entity) | 184099003 | (if DD or MM is not allowed, 15 is used for DD or MM, respectively) | – | – | – |

| B | (Biological) sex | sex | FV | Radio/select | Biological sex (property) (qualifier value) | 734000001 | Female | female | Female (finding) | 248152002 |

| Male | male | Male (finding) | 248153007 | |||||||

| B | Country of residence | residence | FV, FU | List | Country of residence (observable entity) | 416647007 | ISO 3166-1 (alpha-2) | residence_xx (xx = country per ISO standard) | – | – |

| B | Race/Ethnicity | race_ethnicity | FV | List | Race (observable entity) Ethnic group finding (finding) |

103579009 397731000 |

(there are no value recommendations given because of the global differences in race/ethnicity as well as the corresponding legislation on data collection; a collection of local ethnic/racial data where possible is strongly encouraged though) | – | – | – |

| B | Educational level | education | FV | List | Educational achievement (observable entity) | 105421008 |

ISCED 0

=

Early childhood education

ISCED 1 = Primary Education ISCED 2 = Lower Secondary Education ISCED 3 = Upper Secondary Education ISCED 4 = Post-secondary non-Tertiary Education ISCED 5 = Short-cycle tertiary education ISCED 6 = Bachelors degree or equivalent tertiary education level ISCED 7 = Masters degree or equivalent tertiary education level ISCED 8 = Doctoral degree or equivalent tertiary education level |

isced_0 isced_1 isced_2 isced_3 isced_4 isced_5 isced_6 isced_7 isced_8 |

– | – |

| B | Employment status | employment | FV, FU | List | Employment status (observable entity) | 224362002 | Employed with unknown status (full-/part-time) | employed | Employed (finding) | 224363007 |

| Full-time employed | ft_employed | Full-time employment (finding) | 160903007 | |||||||

| Part-time employed | pt_employed | Part-time employment (finding) | 160904001 | |||||||

| Student | student | Student in full time education (occupation) | 413327003 | |||||||

| Retired | retired | Retired, life event (finding) | 105493001 | |||||||

| Medically retired (due to MS) | med_retired_ms | Medically retired, life event (finding) | 160898008 | |||||||

| Medically retired (due to other diseases) | med_retired_other | Medically retired, life event (finding) | 160898008 | |||||||

| Unemployed | unemployed | Unemployed (finding) | 73438004 | |||||||

| Maternal/ parental leave | parental_leave | On maternity leave (finding)/On parental leave (finding) | 224457004/700149001 | |||||||

| Homemaker (housewife/houseman) | homemaker | Homemaker (person) | 444168002 | |||||||

| B | Smoking status | smoking | FV, FU | Radio/select | – | – | Never smoked | never_smoked | Never smoked tobacco (finding) | 266919005 |

| Current smoker | current_smoker | Smoker (finding) | 77176002 | |||||||

| Former smoker | former_smoker | Ex-smoker (finding) | 8517006 | |||||||

| Unknown | smoking_unknown | Tobacco smoking consumption unknown (finding) | 266927001 | |||||||

| If current_smoker: number of cigarettes (daily) | smoking_count | Cigarette consumption (observable entity) | 230056004 | |||||||

| B | Family history of MS | ms_family | FV | Boolean | Family history: Multiple sclerosis (situation) | 160337009 | Yes No Unknown/not sure |

yes no unknown/not_sure |

Yes (qualifier value) No (qualifier value) Unknown (qualifier value) |

373066001 373067005 261665006 |

| Disease-specific information: disease history | ||||||||||

| B | Date of diagnosis | date_diagnosis | FV | YYYY-MM-DD | Date of diagnosis (observable entity) | 432213005 | (if DD or MM is not available, 15 is used for DD or MM, respectively) | – | – | – |

| B | Date of onset | date_onset | FV | YYYY-MM-DD | Date of onset (observable entity) | 298059007 | (if DD or MM is not available, 15 is used for DD or MM, respectively) or unknown/unsure | – | - Unknown (qualifier value) |

261665006 |

| C | Cerebrospinal Fluid: Oligoclonal IgG Bands present (for diagnosis) | csf_olib | FV | Boolean | Cerebrospinal fluid oligoclonal bands (procedure) | 113073005 | Yes No Unknown |

yes no unknown |

Positive (qualifier value) Negative (qualifier value) Unknown (qualifier value) |

10828004 260385009 261665006 |

| B | MS course | ms_course | FV, FU | List | Multiple sclerosis (disorder) | 24700007 | Radiologically isolated syndrome | ris | Radiologically isolated syndrome (disorder) | 16415361000119105 |

| Clinically isolated syndrome | cis | Clinically isolated syndrome (disorder) | 445967004 | |||||||

| Relapsing remitting | rrms | Relapsing remitting multiple sclerosis (disorder) | 426373005 | |||||||

| Secondary progressive | spms | Secondary progressive multiple sclerosis (disorder) | 425500002 | |||||||

| Primary progressive | ppms | Primary progressive multiple sclerosis (disorder) | 428700003 | |||||||

| Disease-specific information: disease status | ||||||||||

| C | MS current status (clinician) | ms_status_clin | FV, FU | List | Chronic disease–follow-up assessment (finding) | 170558000 | Not active and without progression (stable disease) | statusC_stable | Patient’s condition stable (finding) | 359746009 |

| Active (MRI activity or relapses) and with progression | statusC_act_progr | Active (qualifier value)/Progressive (qualifier value) | 55561003/255314001 | |||||||

| Active but without progression | statusC_act_noprogr | Active (qualifier value)/non-progressive (qualifier value) | 55561003/702322003 | |||||||

| Not active but with progression | statusC_inact_progr | Inactive (qualifier value)/Progressive (qualifier value) | 73425007/255314001 | |||||||

| P | MS current status (patient), e.g. “Compare your overall MS status now with what you experienced since last visit: Is your MS. . .” | ms_status_pat | FV, FU | List | Chronic disease–follow-up assessment (finding) | 170558000 | Much worse | statusP_worse2 | Patient status determination, much worse (finding) | 45112000 |

| Worse | statusP_worse1 | Patient’s condition deteriorating (finding) | 275723000 | |||||||

| A little worse | statusP_worse | Patient status determination, slightly worse (finding) | 6718007 | |||||||

| No change | statusP_stable | Patient’s condition stable (finding) | 359746009 | |||||||

| A little better | statusP_better | Patient status determination, slightly improved (finding) | 67405006 | |||||||

| Better | statusP_better1 | Patient’s condition improved (finding) | 268910001 | |||||||

| Much better | statusP_better2 | Patient status determination, greatly improved (finding) | 3286006 | |||||||

| B | Current symptoms | current_symp | FV, FU, RI | Checkboxes/list | Symptom checklist (assessment scale) | 273859002 | Walking/Mobility | symp_walking | Ability to walk (observable entity) | 282097004 |

| Fatigue | symp_fatigue | Fatigue (finding) | 84229001 | |||||||

| Pain | symp_pain | Pain (finding) | 22253000 | |||||||

| Anxiety | symp_anxiety | Anxiety (finding) | 48694002 | |||||||

| Depression | symp_depression | Depressive disorder (disorder) | 35489007 | |||||||

| Vision | symp_vision | Disorder of vision (disorder) | 95677002 | |||||||

| Dizziness | symp_dizziness | Dizziness (finding) | 404640003 | |||||||

| Bladder control | symp_bladder | Impaired urinary system function (finding) | 1156448003 | |||||||

| Bowel control | symp_bowel | Bowel control, function (observable entity) | 129008009 | |||||||

| Spasticity | symp_spasticity | Spasticity (finding) | 221360009 | |||||||

| Sensory symptoms | symp_sensory | Sensory disorder (disorder) | 85972008 | |||||||

| Cognition | symp_cognition | Impaired cognition (finding) | 386806002 | |||||||

| Dexterity | symp_dexterity | Poor manual dexterity (finding) | 306741005 | |||||||

| P | Symptom severity (for each symptom that was collected) | sever_symp | FV, FU, RI | Scale | Symptom severity level (observable entity) | 405162009 | 0–10 (0 being the lowest severity/impact on life and 10 the highest severity/impact on life) | – | – | – |

| B | Symptoms treated | treat_symp | FV, FU | Boolean | Yes No |

yes no |

Yes (qualifier value) No (qualifier value) |

373066001 373067005 |

||

| C | Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS) Score | edss_score | FV, FU, RI | Float | Kurtzke multiple sclerosis rating scale (assessment scale) | 273554001 | 0, 1.0, 1.5, . . ., 10 | – | – | – |

| P | Patient determined disease steps (PDDS) | pdds_score | FV, FU | Integer | 0 (“Normal”), 1 (“Mild disability”), 2 (“Moderate disability”), 3 (“Gait disability”), 4 (“early cane”), 5 (“late cane”), 6 (“bilateral support”), 7 (“wheelchair/scooter”), 8 (“bedridden”) | – | – | – | ||

| C | Timed 25 Foot Walk (T25FW) | t25fw | FV, FU | Float | – | – | (time in seconds) | – | – | – |

| C | 9-Hole Peg Test (9HPT) | 9hpt | FV, FU, RI | Float | Nine hole peg test score (observable entity) | 446602000 | (time in seconds, dominant hand) | – | Dominant hand (attribute) | 263557007 |

| (time in seconds, non-dominant hand) | – | Non-dominant side (qualifier value) | 262458006 | |||||||

| C | Vibratory sense | vib_sense | FV, FU, RI | Vibratory sense, function (observable entity) | 397656001 | Normal (right foot) | vib_normal_right | Normal vibration sensation of right foot (finding) | 830005003 | |

| Decreased (right foot) | vib_decreased_right | Impaired vibration sense of right foot (finding) | 418711005 | |||||||

| Absent (right foot) | vib_absent_right | Absence of vibration sense of right foot (finding) | 830006002 | |||||||

| Normal (left foot) | vib_normal_left | Normal vibration sensation of left foot (finding) | 830004004 | |||||||

| Decreased (left foot) | vib_decreased_left | Impaired vibration sense of left foot (finding) | 130980003 | |||||||

| Absent (left foot) | vib_absent_left |

Absence of vibration sense of left foot (finding) |

417892007 | |||||||

| C | Symbol Digit Modalities Test (SDMT) | sdmt | FV, FU | Int | Symbol Digit Modalities Test score (observable entity) | 718387005 | (number of correct answers/substitutions) | – | – | – |

| Disease-specific information: relapses | ||||||||||

| B | Relapse event | relapse | RI | Boolean | Exacerbation of multiple sclerosis (disorder) | 192929006 | Yes No Unknown/not sure |

yes no unknown/not_sure |

Yes (qualifier value) No evidence of (qualifier value) Unknown (qualifier value) |

373066001 41647002 261665006 |

| B | Date of relapse | date_relapse | RI | YYYY-MM-DD | – | – | (if DD or MM is not available, 15 is used for DD or MM, respectively) | – | – | – |

| B | Steroid treatment for relapse | relapse_treat | RI | Boolean | Corticosteroid and/or corticosteroid derivative therapy (procedure) | 788751009 | Yes No |

yes no |

Yes (qualifier value) No (qualifier value) |

373066001 373067005 |

| B | Recovery | relapse_recovery | RI, FU | Select/radio | Convalescence (finding) | 105499002 | Complete | compl_recovery | – | – |

| Partial | partial_recovery | – | – | |||||||

| No | no_recovery | – | – | |||||||

| Unknown/not sure | unknown/not_sure | Unknown (qualifier value) | 261665006 | |||||||

| Para-clinical investigations: MRI | ||||||||||

| B | MRI done | mri | FU | Boolean | Magnetic resonance imaging (procedure) | 113091000 | Yes No |

yes no |

Yes (qualifier value) No (qualifier value) |

373066001 373067005 |

| B | MRI region | mri_region | FU | Radio/select | – | – | Brain | mri_brain | Magnetic resonance imaging of brain (procedure) | 816077007 |

| Cervical cord | mri_cervical | Magnetic resonance imaging of cervical spine (procedure) | 241646009 | |||||||

| Thoracic cord | mri_thoracic | Magnetic resonance imaging of thoracic spine (procedure) | 241647000 | |||||||

| Whole spinal cord | mri_myelon | Magnetic resonance imaging of spine (procedure) | 241645008 | |||||||

| B | Date of MRI | mri_date | FU | YYYY-MM-DD | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| C | Number of Gd enhanced lesions | mri_gd_les | FU | Integer | – | – | number or “Unknown” | – | -Unknown (qualifier value) | 261665006 |

| C | Number of new or enlarged T1 lesions | mri_new_les_T1 | FU | Integer | – | – | number or “Unknown” | – | -Unknown (qualifier value) | 261665006 |

| C | Number of new or enlarged T2 lesions | mri_new_les_T2 | FU | Integer | – | – | number or “Unknown” | – | -Unknown (qualifier value) | 261665006 |

| Comorbidities | ||||||||||

| B | Comorbidities | comorbidity | FV, FU | Boolean | Co-morbid conditions (finding) | 398192003 | Yes No Unknown/not sure |

yes no unknown/not_sure |

Yes (qualifier value) No (qualifier value) Unknown (qualifier value) |

373066001 373067005 261665006 |

| B | Type of comorbidity | com_type | FV, FU | List | – | – | Alcohol abuse | com_alc_abuse | Alcohol abuse (disorder) | 15167005 |

| Anxiety | com_anxiety | Anxiety disorder (disorder) | 197480006 | |||||||

| Autoimmune Disorder | com_autoimmune | Autoimmune disease (disorder) | 85828009 | |||||||

| Bipolar disorder | com_bipolar | Bipolar disorder (disorder) | 13746004 | |||||||

| Cancer | com_cancer | Malignant neoplastic disease (disorder) | 363346000 | |||||||

| Cardiac arrhythmia | com_arrhythmia | Cardiac arrhythmia (disorder) | 698247007 | |||||||

| Chronic lung disease | com_chronic_lung | Chronic lung disease (disorder) | 413839001 | |||||||

| Congestive heart disease | com_congestive_heart | Congestive heart failure (disorder) | 42343007 | |||||||

| Depression | com_depression | Depressive disorder (disorder) | 35489007 | |||||||

| Diabetes mellitus | com_diabetes | Diabetes mellitus (disorder) | 73211009 | |||||||

| Drug abuse | com_drug_abuse | Drug abuse (disorder) | 26416006 | |||||||

| Epilepsy | com_epilepsy | Epilepsy (disorder) | 84757009 | |||||||

| Eye disease | com_eye | Disorder of eye proper (disorder) | 371405004 | |||||||

| Fibromyalgia | com_fibromyalgia | Fibromyalgia (disorder) | 203082005 | |||||||

| Irritable bowel syndrome | com_ibs | Irritable bowel syndrome (disorder) | 10743008 | |||||||

| Viral hepatitis | com_hepatitis | Viral hepatitis (disorder) | 3738000 | |||||||

| Hyperlipidaemia | com_hyperlipidemia | Hyperlipidaemia (disorder) | 55822004 | |||||||

| Hypertension | com_hypertension | Hypertensive disorder, systemic arterial (disorder) | 38341003 | |||||||

| Ischemic heart disease | com_ischemic_heart | Ischemic heart disease (disorder) | 414545008 | |||||||

| Peripheral vascular disease | com_peripheral_vasc | Peripheral vascular disease (disorder) | 400047006 | |||||||

| Psychosis | com_psychosis | Psychotic disorder (disorder) | 69322001 | |||||||

| Stroke (any) | com_stroke | Cerebrovascular accident (disorder) | 230690007 | |||||||

| C | Comorbidity system (alternative to comorbidity type) | com_system | FV, FU | List | – | – | skeletal | sys_skel | Disorder of skeletal system (disorder) | 88230002 |

| muscular | sys_musc | Disorder of musculoskeletal system (disorder) | 928000 | |||||||

| nervous | sys_nerv | Disorder of nervous system (disorder) | 118940003 | |||||||

| endocrine | sys_endo | Disorder of endocrine system (disorder) | 362969004 | |||||||

| cardiovascular | sys_cardio | Disorder of cardiovascular system (disorder) | 49601007 | |||||||

| lymphatic | sys_lymph | Disorder of lymphatic system (disorder) | 362971004 | |||||||

| respiratory | sys_resp | Disorder of respiratory system (disorder) | 50043002 | |||||||

| digestive | sys_digest | Disorder of digestive system (disorder) | 53619000 | |||||||

| urinary | sys_urin | Disorder of the urinary system (disorder) | 128606002 | |||||||

| reproductive | sys_reprod | Disorder of reproductive system (disorder) | 362968007 | |||||||

| DMT: for current and past treatments | ||||||||||

| B | Current or past DMT | dmt_status | FV, FU | Select/radio | – | – | Yes No (but in the past) DMT naive (Never) |

yes no dmt_naive |

Yes (qualifier value) No (qualifier value) Treatment naive (finding) |

373066001 373067005 844585000 |

| B | DMT type | dmt_type | FV, FU | List | – | – | Alemtuzumab | alemtuzumab | Alemtuzumab (substance) | 129472003 |

| Cladribine | cladribine | Cladribine (substance) | 386916009 | |||||||

| Dimethyl Fumarate | dimethyl_fumarate | Dimethyl fumarate (substance) | 724035008 | |||||||

| Diroximel fumarate | diroximel_fumarate | Diroximel fumarate (substance) | 1268407006 | |||||||

| Fingolimod | fingolimod | Fingolimod (substance) | 449000008 | |||||||

| Glatiramer acetate | glatiramer_acetate | Glatiramer acetate (substance) | 108755008 | |||||||

| Interferon-beta | interferon | Interferon beta (substance) | 420710006 | |||||||

| Peg-Interferon-beta 1a | peg_interferone | Interferon beta (substance) | 420710006 | |||||||

| Monomethyl fumarate | monomethyl_fumarate | Monomethyl fumarate (substance) | 1010557002 | |||||||

| Natalizumab | natalizumab | Natalizumab (substance) | 414805007 | |||||||

| Ocrelizumab | ocrelizumab | Ocrelizumab (substance) | 733464008 | |||||||

| Ofatumumab | ofatumumab | Ofatumumab (substance) | 444607009 | |||||||

| Ozanimod | ozanimod | Ozanimod (substance) | 870525003 | |||||||

| Ponesimod | ponesimod | Ponesimod (substance) | 1179253008 | |||||||

| Siponimod | siponimod | Siponimod (substance) | 786997005 | |||||||

| Teriflunomide | teriflunomide | Teriflunomide (substance) | 703785006 | |||||||

| Ublituximab | ublituximab | |||||||||

| Azathioprine | azathioprine | Azathioprine (substance) | 372574004 | |||||||

| Cyclophosphamide | cyclophosphamide | Cyclophosphamide (substance) | 387420009 | |||||||

| Fludarabine | fludarabine | Fludarabine (substance) | 386907005 | |||||||

| IV Immunoglobulin | immunoglobulin | Immunoglobulin (substance) | 112133008 | |||||||

| Methotrexate | methotrexate | Methotrexate (substance) | 387381009 | |||||||

| Minocycline | minocycline | Minocycline (substance) | 372653009 | |||||||

| Mitoxantrone | mitoxantrone | Mitoxantrone (substance) | 386913001 | |||||||

| Mycophenolate mofetil | mycophenolate_mofetil | Mycophenolate mofetil (substance) | 386976000 | |||||||

| Rituximab | rituximab | Rituximab (substance) | 386919002 | |||||||

| Corticosteroids | corticosteroids | Corticosteroid series (substance) | 255877006 | |||||||

| aHSCT | ahsct | Transplantation of autologous hematopoietic stem cell (procedure) | 709115004 | |||||||

| B | Start date | dmt_start | FV, FU | YYYY-MM-DD | Date treatment started (observable entity) | 413946009 | – | – | – | – |

| B | Stop date | dmt_stop | FV, FU | YYYY-MM-DD | Date treatment stopped (observable entity) | 413947000 | – | – | – | – |

| B | Stop reason | dmt_stop_reas | FV, FU | List | Reason for (attribute)/drug therapy discontinued (situation) | 410666004/274512008 | Developed contraindications | stop_contraindication | Medication stopped–contra-indication (situation) | 395008009 |

| Inefficacy | stop_inefficacy | Medication stopped–ineffective (situation) | 395007004 | |||||||

| Intolerance/treatment-related adverse event | stop_intolerance | Medication stopped–side effect (situation) | 395009001 | |||||||

| Non-adherence | stop_non_adherence | Non-compliance of drug therapy (finding) | 702565001 | |||||||

| Patient Choice/Convenience | stop_patient_choice | Requested by patient (contextual qualifier) (qualifier value) | 15635006 | |||||||

| Persistent disease activity (MRI lesions/relapses) | stop_disease_activity | Active disease following therapy (finding) | 110278006 | |||||||

| Progression of disease/disability | stop_progression | – | – | |||||||

| Financial/insurance coverage issues | stop_financial | Finding related to health insurance issues (finding) | 419808006 | |||||||

| Other | stop_other | Other category (qualifier value) | 394841004 | |||||||

| Unknown | stop_unknown | Unknown (qualifier value) | 261665006 | |||||||

| Non-pharmaceutical treatments | ||||||||||

| B | Non-pharmaceutical treatment type | np_treat_type | FV, FU | List | Professional/ancillary services care (regime/therapy) | 409023009 | Occupational therapy | occupational_therapy | Occupational therapy (regime/therapy) | 84478008 |

| Physiotherapy | physiotherapy | Physical therapy procedure (regime/therapy) | 91251008 | |||||||

| Psychotherapy | psychotherapy | Psychotherapy (regime/therapy) | 75516001 | |||||||

| Rehabilitation | rehabilitation | Rehabilitation therapy (regime/therapy) | 52052004 | |||||||

| Speech therapy | speech_therapy | Speech therapy (regime/therapy) | 5154007 | |||||||

| Other | np_other | Other category (qualifier value) | 394841004 | |||||||

| B | Start date | np_treat_start | FV, FU | YYYY-MM-DD | Date treatment started (observable entity) | 413946009 | date, if available/applicable | – | – | – |

| B | Stop date | np_treat_stop | FV, FU | YYYY-MM-DD | Date treatment stopped (observable entity) | 413947000 | date, if available/applicable | – | – | – |

SNOMED: Systematised Nomenclature of Medicine Clinical Terms; Documented by: B: both; C: clinician-reported specific; P: patient-reported specific; Collection time: FV: first visit, FU: follow-up visit; RI: relapse incidence; ISO: International Organisation for Standardisation; ISCED: International Standard Classification of Education; MS: multiple sclerosis; MRI: magnetic resonance imaging; DMT: disease-modifying treatment; aHSCT: autologous haematopoietic stem cell transplantation.

Discussion

We propose a Core Dataset for MS, consisting of 44 variables (plus date of visit) in eight categories, which can greatly benefit the use of RWD and the generation of real-world evidence (RWE) in MS.

It is important to note that when designing a new collection of clinical data in the form of a disease registry, a common experience is that initial ambitions are higher than what is eventually possible to collect longitudinally with a high degree of data completeness. Even if the proposed Core Dataset has been limited to contain what was considered a reasonable minimum of variables, it indeed exceeds the current data collections and the completeness of the collected variables of most, if not all, existing registries.4,24 Thus, the value of the Core Dataset in this context is to provide a structured and formatted list of variables to be considered for a new registry, rather than as a mandatory template.

The use and implementation of the Core Dataset is recommended for prospective (i.e. improving data collection efforts moving forward) and retrospective (i.e. coping with heterogeneity of existing data sources) harmonisation efforts. The Core Dataset may benefit prospective harmonisation in:

(1) Adapting RWD collection efforts by using the Core Dataset as a blueprint for the data acquisition tool to shape or alter the source dataset of the registry/cohort. MS registries, especially those with patient-reported data, may tailor the formulation of a question for a certain variable to incorporate local differences, for example, regarding language or the level of detail needed to ask for a certain variable.

(2) Guiding new RWD initiatives. In order to reach emerging registries and initiatives, the Core Dataset will be part of the educational programme of the MSDA called ‘How to set up a registry?’ 25 as a leading example in the topic dealing with the harmonisation and alignment for data collection. The educational activities will be updated along with the revisions and (local) adoptions of the Core Dataset. In addition, the Core Dataset is made available on the website and the social media account of the MSDA and partner organisations for easy access and to promote dissemination.

When it comes to retrospective harmonisation efforts, the Core Dataset aims to serve as the target schema definition for harmonisation activities. A target schema definition is the desired output to which (an extract of) the registry’s source data is transformed. The source dataset is not altered, and the routine prospective data collection within the registry/cohort is not changed. An example of this is the transformation of a birth date in the original format (e.g. MM/DD/YYYY) to the target format (e.g. YYYY-MM-DD). Retrospective harmonisation of existing RWD has proven successful within the GDSI, where RWD from different data sources was transformed into and verified against the COVID-19 core dataset before uploading the patient-level data into the central platform.

A challenge for this version of the Core Dataset data dictionary was the value definition of some variables that had a variety of options and no straight-forward value set was identifiable. For example: (1) For the topic of ‘Comorbidities’ it was decided to use Marrie et al. 26 as the leading published list of comorbidities in MS although it may not include all the relevant comorbidities (as they are either dependent on the specific use case/research question or part of the detailed PASS data collections). As an optional variable, body systems were added for a broader collection of comorbidities. This may serve RWD collections where the granular collection of comorbidities is not possible; (2) The variable ‘race/ethnicity’ was added because of the influence of ancestry on disease prevalence, course or treatment effectiveness.27–29 Due to the large variety of local racial and ethnic categories across the globe, it was decided not to include recommendations for values but to include the variable into the Core Dataset with the note to adhere to local ethnicity/race data values;

(3) For ‘current symptoms’, SymptoMScreen, 30 a validated and published list of symptoms, was chosen for the first version of the Core Dataset to be the guide for the symptom list to address both patient-driven and clinician-driven data collection needs. It is conceivable that it will be extended in the future or adapted to further validations like Zhang et al. 31 or other (arising) symptom questionnaires. A recommendation for a severity score for those symptoms was also added to enhance granularity in symptom follow-up/management, especially in patient-driven data collections.

A regular revision of the current Core Dataset (v2022) is anticipated, especially in regards to the currently excluded variables or pragmatic choices of values. Variables excluded for the 2022 version were those considered future-oriented but not yet widely collected (e.g. biomarkers, including neurofilament, optical coherence tomography, or new progression assessments). Variables on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) measurements and outcomes focussing not only on relapsing-remitting MS (RRMS) but progressive forms of MS as well are also excluded for now due to feasibility and data coverage limitations. They are also potentially exposed to noise in the data, for example, through the use of different scanners, MRI protocols or interobserver variety for brain volume measurements. Dataset variables needing a dedicated set of data elements (e.g. in the area of patient-reported outcomes (cf. PROMS initiative)32,33 or pharmacovigilance) are also not included. The latter is anticipated to be driven by leading networks like BMSD or PROMS initiative focusing on these specific topics. For example, the BMSD has already established a ‘core BMSD post-authorisation safety studies (PASS) protocol’ for disease-modifying treatments within their network that provides a high-level concept for future PASS although further customization is required for a specific PASS depending on its research questions. The BMSD is working on an updated core PASS protocol and the registries involved in the BMSD aim to become qualified registries for PASS by the EMA. 34 For that reason, data elements on serious adverse events related to disease-modifying treatments were not included in the MSDA Core Dataset.

The Core Dataset was developed within a predefined time frame using a pragmatic approach by including clinical MS variables commonly observed in real-world datasets and feasible to collect. This pragmatic approach naturally has limitations. The task force consisted of a limited number of experts in the field of MS and RWD and only indirectly involved patients (represented by the patient registries and organisation). An extension of the task force, including patients or more experts from other countries, could be considered for future work. This is also helpful in minimising bias in the selection of the core variables. The personal and professional background and interests of the participating experts of the task force may also have influenced the selection of the core variables.

When considering future revisions of the Core Dataset, the cost/effort is another aspect to consider. Getting a task force together requires time and resources spent by involved parties. Compared to consistently new definitions of minimal or core datasets for each new collaboration, this seems to be a benevolent calculation of cost–value ratio though.

Conclusion

The Core Dataset aims to reduce heterogeneity and to promote harmonisation across MS data sources, by incorporating elements that promote faster collaboration within and outside of the MS community. This will help answer questions and solve challenges related to clinical care more quickly–benefitting people with MS. The MSDA Core Dataset v2022 can act as a consolidated step towards a more effective and efficient use of RWD in MS. It is foreseen that the future development of the current Core Dataset and the establishment of core datasets for special interest topics will further support the prospective and retrospective harmonisation in and across MS registries and cohorts. The detailed Core Dataset is presented in Table 1 and freely downloadable on the MSDA website (https://www.msdataalliance.org/).

Footnotes

Author Contributions: T.P. took the lead in writing this manuscript based on the minutes of the task force meetings and the work done in preparation and postprocessing of those. L.M.P., the chair of the MSDA, acted as the overall project leader and was responsible for the study design and the coordination. Working on behalf of the MSDA, L.G. provided minutes of the task force meetings and contributed to the manuscript by providing content, comments, and suggestions. As members of the task force, all other co-authors actively participated in the task force and contributed to the manuscript by providing content, comments, and suggestions.

The author(s) declared the following potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: T.P. has no other conflicts of interests to disclose than that she is funded by the Flemish Government under the ‘Special Research Fund (Bijzonder Onderzoeksfonds, BOF)’: BOF22OWB01. L.G. has no other conflicts of interests to disclose than that she is funded by the Flemish Government under the ‘Onderzoeksprogramma Artificiële Intelligentie Vlaanderen’. A.H. has no personal pecuniary interests to disclose, other than being an employee of the MS International Federation, which receives income from a range of corporate sponsors, recently including: Biogen, BristolMyersSquibb, Coloplast, Janssen, Merck, Viatris (formerly Mylan), Novartis, Roche and Sanofi – all of which is publicly disclosed. J.H. has received honoraria for serving on advisory boards for Biogen, Bristol-Myers-Squibb, Sanofi-Genzyme, Merck KGaA, Novartis, and Sandoz and speaker’s fees from Biogen, Novartis, Merck KGaA, Teva and Sanofi-Genzyme. He has served as P.I. for projects, or received unrestricted research support from, Biogen, Bristol-Myers-Squibb, Merck KGaA, Novartis, Roche and Sanofi-Genzyme. His MS research was funded by the Swedish Research Council and the Swedish Brain foundation. H.S. works for the Accelerated Cure Project for MS (ACP), which has received grants, collaboration funding, payments for use of assets, or in-kind contributions from the following companies: EMD Serono, Sanofi/Genzyme, Biogen, Genentech, AbbVie, Octave, GlycoMinds, Pfizer, MedDay, AstraZeneca, Teva, Mallinckrodt, MSDx, Regeneron Genetics Centre, BC Platforms, and Celgene. A.C.P. has also received funding from the Patient-Centred Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) and the National MS Society (NMSS). A.S. is on the editorial board for Neurology and serves as a consultant for Gryphon Bio, LLC. She has received research funding from the Department of Defence, MS Society of Canada, National MS Society and the Consortium of MS Centres. A.S. works for the NARCOMS Registry which is supported by the Consortium of MS Centres (CMSC) and the Foundation of the CMSC. R.M. has received no personal funding from any sources, the UK MS Register is funded by the MS Society, and has received funding for specific projects from Novartis, Sanofi-Genzyme, and Merck KGaA. A.S. has no personal pecuniary interests to disclose, other than being the lead of the German MS-Registry, which receives funding from a range of public and corporate sponsors, recently including: The German Innovation Fund (G-BA), The German MS Trust, The German Retirement Insurance, German MS Society, Biogen, Celgene (BMS), Merck, Novartis, Roche and Sanofi. P.D. is a full-time employee and a shareholder of Biogen. E.H.M.-L. and K.P. have no conflicts of interest to disclose. The views expressed in this article are the personal views of the author(s) and may not be understood or quoted as being made on behalf of or reflecting the position of the EMA or one of its committees or working parties. P.I. has served on scientific advisory boards for Biogen Idec, Bayer, Teva, Roche, Merck Serono, Novartis and Genzyme and has received funding for travel and/or Speaker honoraria from Sanofi Aventis, Genzyme, Biogen Idec, Teva, Merck Serono, Alexion and Novartis. J.I.R. has received honoraria from Novartis as a scientific advisor. He has received travel grants and attended courses and conferences on behalf of Merck-Serono Argentina, Novartis, Roche, Sanofi-Genzyme, Biogen, Bayer and Teva. He receives unrestricted research funding from Novartis, Biogen, Roche, Merck and Sanofi. M.M. has served in scientific advisory board for Sanofi, Novartis, Merck, and has received honoraria for lecturing from Biogen, Merck, Novartis, Roche, Genzyme, Bristol-Myers Squibb. She received research support and support for congress participation from Biogen, Genzyme, Roche, Merck, Novartis. A.v.d.W. has received honoraria and unrestricted research funding from Novartis, Biogen, Roche, Merck and Sanofi. G.C. reports that he has received consulting and speaking fees from Novartis, Teva Pharmaceutical Industries Ltd, Teva Italia Srl, Sanofi-Genzyme Corporation, Genzyme Europe, Merck KGgA, Merck Serono SpA, Celgene Group, Biogen Idec, Biogen Italia Srl, F. Hoffman-La Roche, Roche SpA, Almirall SpA, Forward Pharma, Medday, and Excemed. L.M.P. has no conflict to report related to this work other than being the chair and the coordinator of the MSDA initiative, receiving funding from a range of corporate sponsors, including Biogen, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Merck, Novartis, and Roche. All other co-authors have no relevant competing interests to report. The authors declare that the funding sources did not influence the content of this work.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: The work was funded by the MS Data Alliance Initiative. The MS Data Alliance is a global multi-stakeholder non-for-profit organisation working under the umbrella of the European Charcot Foundation, financially supported by a combination of industry partners including Novartis, Merck, Biogen, Janssen, Bristol-Myers Squibb and Roche. None of the co-authors received any personal financial reimbursement for their work and time contributed to this manuscript and/or their involvement within the task force.

ORCID iDs: Jan Hillert  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7386-6732

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7386-6732

Amber Salter  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1088-110X

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1088-110X

Rodden Middleton  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2130-4420

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2130-4420

Alexander Stahmann  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5308-105X

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5308-105X

Pietro Iaffaldano  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2308-1731

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2308-1731

Anneke van der Walt  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4278-7003

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4278-7003

Giancarlo Comi  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6989-1054

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6989-1054

Liesbet M Peeters  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6066-3899

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6066-3899

Contributor Information

Tina Parciak, University MS Center (UMSC), Hasselt-Pelt, Belgium; UHasselt, Biomedical Research Institute (BIOMED), Diepenbeek, Belgium; UHasselt, Data Science Institute (DSI), Diepenbeek, Belgium.

Lotte Geys, University MS Center (UMSC), Hasselt-Pelt, Belgium; UHasselt, Biomedical Research Institute (BIOMED), Diepenbeek, Belgium; UHasselt, Data Science Institute (DSI), Diepenbeek, Belgium.

Anne Helme, Multiple Sclerosis International Federation, London, UK.

Ingrid van der Mei, Menzies Institute for Medical Research, University of Tasmania, The Australian MS longitudinal study (AMSLS), Hobart, TAS, Australia.

Jan Hillert, Department of Clinical Neuroscience, Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, Sweden.

Hollie Schmidt, Accelerated Cure Project, iConquerMS People-Powered Research Network, Waltham, MA, USA.

Amber Salter, Section on Statistical Planning and Analysis, UT Southwestern Medical Center, NARCOMS Registry, COViMS Registry, Dallas, TX, USA.

Magd Zakaria, Department of Neurology, Ain Shams University, Cairo, Egypt.

Rodden Middleton, Population Data Science, Swansea University Medical School, Swansea, UK.

Alexander Stahmann, German MS Register by the German MS Society, MS Research and Project Development gGmbH (MSFP), Hanover, Germany.

Pamela Dobay, Biogen, Baar, Switzerland.

Elena Hernandez Martinez-Lapiscina, Office of Therapies for Neurological and Psychiatric Disorders (H-NEU), Human Medicines (H-Division), European Medicines Agency, Amsterdam, The Netherlands.

Pietro Iaffaldano, Department of Translational Biomedicine and Neurosciences (DiBraiN), Università degli Studi di Bari Aldo Moro, Italian MS registry, Bari, Italy.

Kelly Plueschke, Data Analytics and Methods Task Force, European Medicines Agency, Amsterdam, The Netherlands.

Juan I Rojas, Neurology Department, Hospital Universitario de CEMIC, RelevarEM, Buenos Aires, Argentina.

Meritxell Sabidó, Department of Epidemiology, Merck Healthcare KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany.

Melinda Magyari, Danish Multiple Sclerosis Registry and Danish Multiple Sclerosis Center, Department of Neurology, Copenhagen University Hospital – Rigshospitalet, Glostrup, Denmark.

Anneke van der Walt, Department of Neuroscience, Central Clinical School, Monash University, Melbourne, VIC, Australia.

Francis Arickx, National Institute for Health and Disability Insurance, Brussels, Belgium.

Giancarlo Comi, Department of Rehabilitation Neurosciences, Casa di Cura Igea, Milan, Italy.

Liesbet M Peeters, University MS Center (UMSC), Hasselt-Pelt, Belgium; UHasselt, Biomedical Research Institute (BIOMED), Diepenbeek, Belgium; UHasselt, Data Science Institute (DSI), Diepenbeek, Belgium.

References

- 1. Cohen JA, Trojano M, Mowry EM, et al. Leveraging real-world data to investigate multiple sclerosis disease behavior, prognosis, and treatment. Mult Scler 2020; 26(1): 23–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. European Medicines Agency. Patient registries workshop, 28 October 2016–Observations and recommendations arising from the workshop. EMA/69716/2017, https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/report/report-patient-registries-workshop_en.pdf (2017, accessed 16 May 2023).

- 3. Bebo BF, Jr, Fox RJ, Lee K, et al. Landscape of MS patient cohorts and registries: Recommendations for maximizing impact. Mult Scler 2018; 24(5): 579–586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Geys L, Parciak T, Pirmani A, et al. The multiple sclerosis data alliance catalogue: Enabling web-based discovery of metadata from real-world multiple sclerosis data sources. Int J MS Care 2021; 23: 261–268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Pugliatti M, Eskic D, Mikolcić T, et al. Assess, compare and enhance the status of persons with multiple sclerosis (MS) in Europe: A European Register for MS. Acta Neurol Scand Suppl 2012(195): 24–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hillert J, Magyari M, Soelberg Sørensen P, et al. Treatment switching and discontinuation over 20 years in the big multiple sclerosis data network. Front Neurol 2021; 12: 647811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Salter A, Stahmann A, Ellenberger D, et al. Data harmonization for collaborative research among MS registries: A case study in employment. Mult Scler 2021; 27(2): 281–289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Iaffaldano P, Lucisano G, Patti F, et al. Transition to secondary progression in relapsing-onset multiple sclerosis: Definitions and risk factors. Mult Scler 2021; 27(3): 430–438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Signori A, Lorscheider J, Vukusic S, et al. Heterogeneity on long-term disability trajectories in patients with secondary progressive MS: A latent class analysis from Big MS Data network. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2023; 94(1): 23–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hillert J, Trojano M, Vukusic S, et al. Big multiple sclerosis data–A registry basis for post authorization safety studies (PASS) for multiple sclerosis. ECTRIMS 2019 – poster session 2. Mult Scler 2019; 25: 761–762. [Google Scholar]

- 11. European Medicines Agency. Multiple sclerosis workshop–Registries initiative. EMA/548474/2017, https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/report/report-multiple-sclerosis-registries_en.pdf (2018, accessed 20 December 2022).

- 12. Peeters LM, Parciak T, Kalra D, et al. Multiple sclerosis data alliance–A global multi-stakeholder collaboration to scale-up real world data research. Mult Scler Relat Disord 2021; 47: 102634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Peeters LM, Parciak T, Walton C, et al. COVID-19 in people with multiple sclerosis: A Global Data Sharing Initiative. Mult Scler 2020; 26(10): 1157–1162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. MS data alliance–Global recommendations, https://www.msdataalliance.org/cat/12/Global%20Recommendations (accessed 30 May 2023).

- 15. Butzkueven H, Chapman J, Cristiano E, et al. MSBase: An international, online registry and platform for collaborative outcomes research in multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler 2006; 12(6): 769–774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Multiple sclerosis NINDS common data elements, https://www.commondataelements.ninds.nih.gov/Multiple%20Sclerosis (accessed 22 December 2022).

- 17. Ajami S, Ahmadi G, Saghaeiannejad-Isfahani S, et al. A comparative study on iMed(©) and European database for multiple sclerosis to propose a common language of multiple sclerosis data elements. J Educ Health Promot 2014; 3: 107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Maelstrom research–NARCOMS, https://www.maelstrom-research.org/study/narcoms (accessed 22 December 2022).

- 19. Fox RJ, Bacon TE, Chamot E, et al. Prevalence of multiple sclerosis symptoms across lifespan: Data from the NARCOMS Registry. Neurodegener Dis Manag 2015; 5(6): 3–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ohle L-M, Ellenberger D, Flachenecker P, et al. Chances and challenges of a long-term data repository in multiple sclerosis: 20th birthday of the German MS registry. Sci Rep 2021; 11: 13340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. iConquerMS. Home, https://www.iconquerms.org/ (accessed 22 December 2022).

- 22. McBurney R, Zhao Y, Loud S, et al. Initial characterization of participants in the iConquerMSTM network. ACTRIMS Forum 2017. Mult Scler J 2017; 23(1_suppl): 2–90. doi:10.1177/1352458517693959. [Google Scholar]

- 23. SNOMED. 5-Step briefing, https://www.snomed.org/five-step-briefing (accessed 16 May 2023).

- 24. Glaser A, Stahmann A, Meissner T, et al. Multiple sclerosis registries in Europe–An updated mapping survey. Mult Scler Relat Disord 2019; 27: 171–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. MS Data Alliance. Educational program, https://www.msdataalliance.org/cat/4/Educational%20Program (accessed 30 May 2023).

- 26. Marrie RA, Cohen J, Stuve O, et al. A systematic review of the incidence and prevalence of comorbidity in multiple sclerosis: Overview. Mult Scler 2015; 21(3): 263–281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Amezcua L, McCauley JL. Race and ethnicity on MS presentation and disease course. Mult Scler 2020; 26(5): 561–567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Langer-Gould AM, Gonzales EG, Smith JB, et al. Racial and ethnic disparities in multiple sclerosis prevalence. Neurology 2022; 98: e1818–e1827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Onuorah H-M, Charron O, Meltzer E, et al. Enrollment of non-white participants and reporting of race and ethnicity in phase III trials of multiple sclerosis DMTs: A systematic review. Neurology 2022; 98: e880–e892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Green R, Kalina J, Ford R, et al. SymptoMScreen: A tool for rapid assessment of symptom severity in MS across multiple domains. Appl Neuropsychol Adult 2017; 24(2): 183–189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Zhang Y, Taylor BV, Simpson S, et al. Validation of 0–10 MS symptom scores in the Australian multiple sclerosis longitudinal study. Mult Scler Relat Disord 2020; 39: 101895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Zaratin P, Vermersch P, Amato MP, et al. The agenda of the global patient reported outcomes for multiple sclerosis (PROMS) initiative: Progresses and open questions. Mult Scler Relat Disord 2022; 61: 103757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. The Lancet Neurology. Patient-reported outcomes in the spotlight. Lancet Neurol 2019; 18(11): 981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. European Medicines Agency. Letter of support for performing registry-based post authorisation safety studies (PASS) in Multiple Sclerosis (MS) using data of the Big MS Data Network (BMSD), https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/other/letter-support-performing-registry-based-post-authorisation-safety-studies-pass-multiple-sclerosis_en.pdf (2022, accessed 16 May 2023).