Abstract

Human mesenchymal stromal cells (hMSCs) are of significant interest as a renewable source of therapeutically useful cells. In tissue engineering, hMSCs are implanted within a scaffold to provide enhanced capacity for tissue repair. The present study evaluates how mechanical properties of that scaffold can alter the phenotype and genotype of the cells, with the aim of augmenting hMSC differentiation along the myogenic, neurogenic or chondrogenic linages. The hMSCs were grown three-dimensionally (3D) in a hydrogel comprised of poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG)-conjugated to fibrinogen. The hydrogel’s shear storage modulus (G’), which was controlled by increasing the amount of PEG-diacrylate cross-linker in the matrix, was varied in the range of 100–2000 Pascal (Pa). The differentiation into each lineage was initiated by a defined culture medium, and the hMSCs grown in the different modulus hydrogels were characterized using gene and protein expression. Materials having lower storage moduli (G’=100 Pa) exhibited more hMSCs differentiating to neurogenic lineages. Myogenesis was favored in materials having intermediate modulus values (G’=500 Pa), whereas chondrogenesis was favored in materials with a higher modulus (G’=1000 Pa). Enhancing the differentiation pathway of hMSCs in 3D hydrogel scaffolds using simple modifications to mechanical properties represents an important achievement towards the effective application of these cells in tissue engineering.

Keywords: Hydrogel, Stem cells, Tissue Engineering, Biomaterials, Shear Modulus

Introduction

The field of tissue engineering employs various forms of hydrogel scaffolds for making tissue analogues or enhancing the repair of damaged organs1–3. For example, injectable biomaterial cell carriers – used to localize grafted stem cell in vivo - are often comprised of hydrogel precursors that undergo in situ cross-linking in the body4,5. For the 3D printing of cell-laden tissues and organs (i.e., bioprinting), the use of hydrogels as bioinks is essential to ensure proper cell entrapment and hierarchical distribution within the printed structures6,7. Microparticles made from cell-laden hydrogels are often used to transplant cells that require immune protection in the host tissue8. Recently, hydrogels have also been used to cultivate pluripotent stem cells for their efficient and scalable bioprocessing and biomanufacturing9–12.

Human mesenchymal stem cells (hMSCs) represent a promising cell source for tissue engineering and cell therapy13. A hydrogel scaffold that guides the growth and differentiation of hMSCs would help to overcome some of the most enduring challenges that have hampered clinical progress in tissue engineering with these cells14–16. For example, hydrogels that control hMSC differentiation towards a chondrogenic lineage have been used successfully for cartilage tissue engineering applications17,18, but there has been very limited clinical translation with this approach. For certain tissue types such a nerve or muscle, the use of hydrogels as 3D scaffolds for hMSCs remains even more elusive. This is because most hydrogels, particularly synthetic or natural polysaccharide-based materials, require extensive biological modifications to support differentiation of hMSCs along neurogenic or myogenic lineages19. There are exceptions to this, namely with biological protein hydrogels such as type I collagen, fibrin or Matrigel20; yet these biological materials provide limited control over their mechanical properties21. In view of the growing scientific consensus that matrix mechanics is an important feature that guides hMSC differentiation along a particular pathway22,23, there is a need to include mechanical properties as one of the design parameters for cellular scaffolds24,25.

Scientific evidence from 2D culture studies indicate that when hMSCs are cultivated on soft biomaterial substrates, they respond by enhancing their differentiation along a neurogenic pathway26–28. Similar results were also demonstrated using substrates of an intermediate stiffness for myogenesis of hMSCs29,30, and high stiffness for osteogenesis31,32. The continuation of these experimental studies in 3D culture, using hMSCs cultured inside hydrogels of varying modulus, has been hampered by the complexity of growing cells inside a material that can provide uniform and homogenous mechanical cues33,34. Studies of mechanobiology in 3D culture are inherently confounded by dimensionality constraints35,36; that is the encapsulating effects when cells are entrapped in a dense hydrogel matrix37,38. In this scenario, certain material parameters other than modulus can inadvertently affect cell phenotype, including features such as proteolytic biodegradation, limited cell adhesivity, viscoelasticity of the matrix and the porosity of the matrix39,40. Despite these challenges, several recent investigations using 3D culture with different cell types and alterations in material properties reveal just how confounding the response of stem cell to material properties in 3D culture can be41–44.

Here we systematically investigated the differentiation of hMSCs in 3D culture with hydrogels made from a semi-synthetic material that is proteolytically degradable, cell adhesive, and biologically active. Our strategy involves prompting hMSC differentiation along the neurogenic, myogenic and chondrogenic lineages using defined culture media and evaluating modulus-dependent cell fate determinations by identifying material moduli that preferentially promote specific lineages. The material used for 3D cell encapsulation and culture is comprised of a poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG)-conjugated to fibrinogen45. Control over mechanical properties of the hydrogel was accomplished by increasing the cross-linking density using additional PEG-diacrylate cross-linker46. Pluripotency markers and differentiation markers were used to characterize the hMSCs in the hydrogels with a matrix shear storage modulus ranging from 100 Pascals to 2000 Pascals. In this range of hydrogels properties, the dimensionality effects on the hMSCs did not restrict the formation of cellular extension in the 3D matrix during a weeks-long culture period. Enhancement of differentiation was accomplished with a combination of lineage-specific medium and optimal matrix modulus. Morphogenesis was also characterized and correlated to typical patterns associated with each lineage. The results underscore the important contribution of a specific set of mechanical properties to the scaffold design when using encapsulating hydrogels and hMSCs in certain tissue engineering applications.

Methods

Hydrogel Preparation

Poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG)-diacrylate (PEG-DA) was prepared using 10-kDa PEG-OH as described elsewhere47. Bovine PEG-fibrinogen (bPF) was prepared by conjugating linear PEG-DA to unreacted cysteines on denatured bovine fibrinogen (Bovogen Biologicals, Melbourne Australia). This was done according to a PEGylation protocol described by Dikovsky et al.48 The PEG-fibrinogen was brought to final protein concentration of 10–12 mg/ml. The final PF was aseptically filtered and characterized for protein concentration and PEG concentration according to previously published protocols49. The hydrogel precursor solution was diluted to a desired protein concentration of 8 mg/ml and augmented with 10-kDa PEG-DA to achieve control over cross-linking and mechanical properties. The precursor was also supplemented with Irgacure®2959 photo-initiator (Ciba Specialty Chemicals, Basel, Switzerland/Tarrytwon, New York) at a concentration of 0.1% (w/v) for the photo-polymerization reaction. The latter was performed with a long-wave UV light (365 nm, 4–5mW/cm2) after 5 min exposure.

Mechanical Properties

A strain-rate controlled rheometer (TA Instruments AR-G2, New Castle, DE, USA) was used to measure the shear storage and loss modulus of the hydrogels during the photo-polymerization reaction. The rheometer was outfitted with a parallel-plate geometry and UV curing cell to facilitate the photo-polymerization reaction under oscillatory shear stress. Previous experiments were used to determine the exact frequency (3 rad/s) and strain (2% sinusoidal strain) for performing the time sweep tests. Each material was characterized in triplicate for 5 min at 37°C, to monitor the photo-polymerization reaction of the hydrogel precursor solution (200 μl). The time sweep test was initiated with a 30 second preconditioning phase, followed by exposure to long-wave UV light (365 nm, ~5 mW/cm2) while the storage (G′) and loss (G″) modulus values were continuously recorded with RSIS Orchestrator 6.5.8 software. The reported shear storage and loss modulus were taken from the complex shear modulus G* = G′+ iG″ at the conclusion of the test. A set of materials with a range of storage shear moduli from G’=100 Pa up to 2000 Pa was used in this study. Specifically, up to five treatments representing targeted modulus values of G’=100 Pa, 250 Pa, 500 Pa 1000 Pa, and 2000 Pa were prepared by adding the relative amount of PEG-DA to the 8 mg/ml bPF solution. The precise rheological properties of the hydrogels representing the different treatments used in this study are detailed in Table 1.

Table 1.

The rheological properties of the hydrogels representing the different treatments used in the study (data is presented as the average plus/minus standard deviation).

| Treatment | PEG-DA concentration | Tan (delta) | Shear Storage Modulus G’ (Pascal) | Shear Loss Modulus G” (Pascal) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| bPF100 | 0.2 | 0.0123±0.002 | 126±3 | 1.55±0.29 |

| bPF250 | 0.45 | 0.0074±0.0013 | 250±6 | 1.83±0.28 |

| bPF500 | 0.8 | 0.0043±0.002 | 499±22 | 2.15±0.17 |

| bPF1000 | 1.4 | 0.0025±0.0003 | 1004±50 | 2.5±0.15 |

| bPF2000 | 2.2 | 0.0031±0.0004 | 1794±103 | 5.63±0.81 |

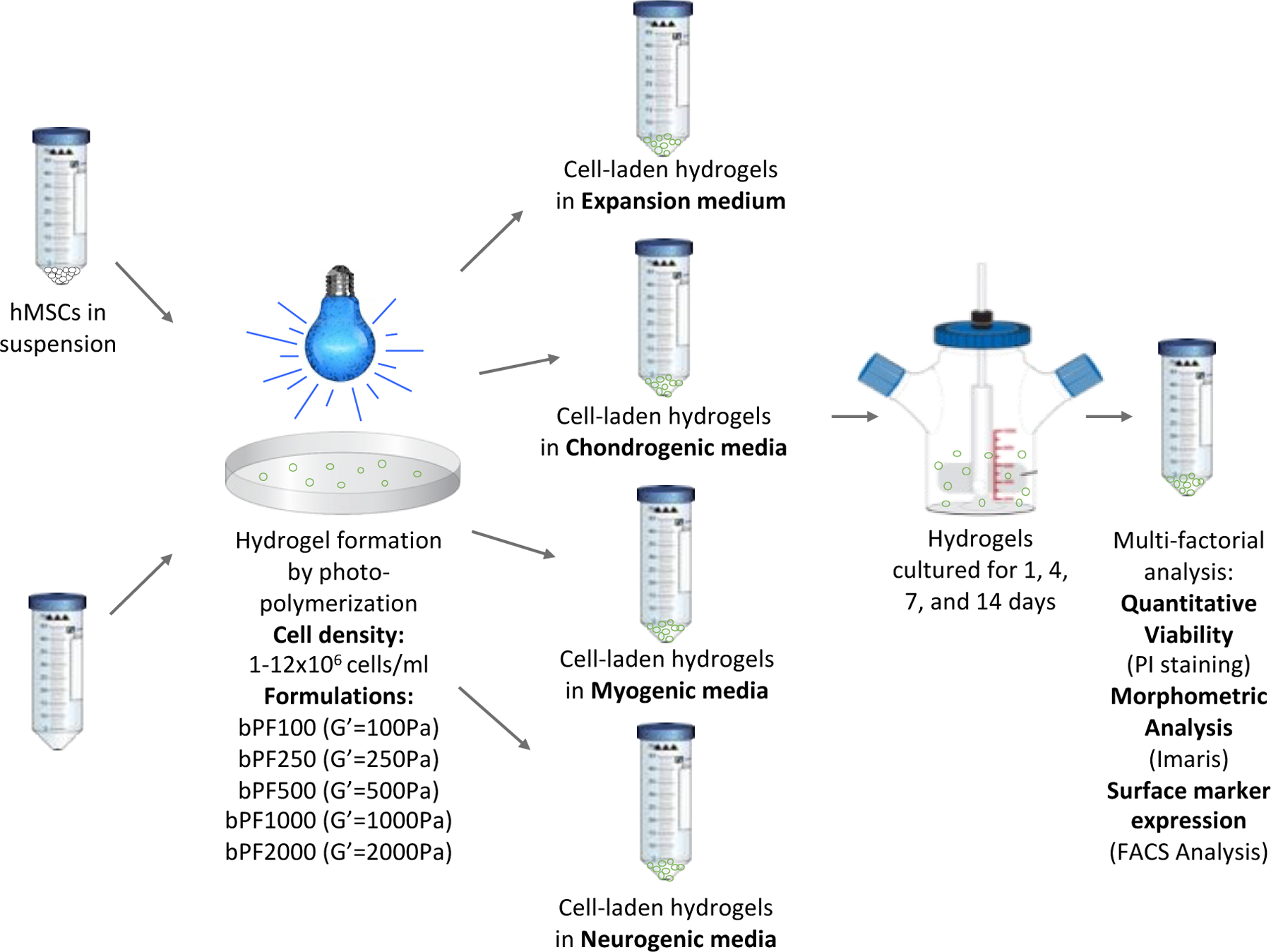

Cell Culture Experiments

Human mesenchymal stem cells (hMSCs, Lonza) were purchased and expanded in MSCGM medium (Lonza PT-3001) containing 1% Pen-Strep (Biological Industries, Beit Haemek, Israel), according to manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, the hMSCs were sub-cultured for no more than 4 passages, with each passage representing 12–14 days of sub-culture. This corresponds to 4 doublings from P4 to P8. Harvesting the hMSCs was done using trypsin EDTA solution B (Biological Industries) for 2 min, followed neutralization in growth medium and centrifugation at 200 RCF for 5 min. The hMSCs were then encapsulated within bPF hydrogels at a specified cell seeding density of between one million and 12 million cells per milliliter of hydrogel precursor solution. Spherical hydrogel constructs containing cells were formed by dripping the cell-containing PF hydrogel precursor solution from a 27-gauge syringe onto a super-hydrophobic plate and cross-linking with UV photopolymerization for 1.5 min (365 nm, 5 mW/cm2) as described elsewhere50. Expansion MSCGM medium (Lonza PT-3001) was used to culture the hMSCs in hydrogels, whereby the essential nutrients and growth factors were specific for self-renewal. For the differentiation experiments, cells in hydrogels were cultured in appropriate differentiation medium: MSCs chondrocyte differentiation (BulletKit, Lonza PT-3003), MSCs skeletal muscle cell differentiation medium (PromoCell C-23061), and MSC neurogenic differentiation medium (PromoCell C-28015). At the conclusion of the experiment (on days 1, 4, 7, and 14), the cells were either fixed using 10% formalin (Sigma) for image analysis or harvested for FACS analysis, using trypsin EDTA solution B (Biological Industries) and collagenase (Sigma), as described elsewhere50. We previously optimized the enzymatic method and showed that the released cells from the hydrogel are not altered in terms of their surface marker expression50,51. A schematic illustration of the cellular bioprocessing and experimental design is provided in Figure 1.

Figure 1:

Experimental setup used to identify modulus-dependent differentiation patterns of hMSCs in 3D PEG-fibrinogen (PF) hydrogel cultures. PF hydrogels are formed with hMSCs and 8 mg/mL PF hydrogel liquid precursor, cross-linked by photopolymerization, and cultivated for up to 14 days in bioreactors using culture medium for expansion or differentiation. Cell-laden hydrogels were recovered from the bioreactors at set time-points and analyzed for viability, morphometrics and differentiation.

Cell Viability

A live/dead fluorescence staining assay was used to visualize the viability within the cell-laden hydrogels. The encapsulated cells were stained with 4 mM calcein-AM solution and 2 mM ethidium homodimer I solution (in DMSO, Sigma). Multiple areas within each construct were imaged using Zeiss LSM700 confocal microscope (at least three samples per treatment). Quantitative viability was assessed using a Propidium Iodide (PI) staining and cell counting. The number of cells stained positive for PI was determined by first proteolytically degrading the gels and releasing them from within the hydrogels into a suspension of phosphate buffered saline (PBS). A detailed protocol for hydrogel dissolution is described elsewhere50. The hMSCs were then incubated with 100μL of PBS containing PI staining solution (Sigma) for 10 minutes at 37°C according to manufacturer’s instructions, as described previously50. The cells were kept on ice, then injected into a flow cytometry (BD™ LSR II) with the parameters set for PI staining. The samples were measured, and the data analyzed using FCS-express software (4.7). Unstained cells were used as a baseline control. The percent of viable cells was calculated from the number of PI-positive cells in the entire population.

Cell morphology using InCell analysis

Advanced microscopic imaging techniques were used to visualize and quantify hMSC morphology. hMSCs cultured within PF hydrogels were imaged in situ using a Zeiss LSM 700 confocal microscope (Carl Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany). The hMSCs within the PF constructs were fixed in 10% formalin in PBS (Sigma) and stained for filamentous actin (f-actin) using a Phalloidin-Tritc stain (sigma) and a nuclear stain, DAPI (sigma), both done according to manufacturer’s recommendations. Briefly, the cells were permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100 in PBS (Sigma) for 10 min. The cells were then stained with TRITC-labeled phalloidin (Tritc-phalloidin, 1ug/ml, Sigma) for 1h at room temperature, and counterstained by adding the DAPI for 30 minutes. The cells were then washed three times with PBS at room temperature and then overnight at 4°C. The stained cells were scanned and analyzed using an InCell Analyzer 2000 (GE, USA) by evaluating scanning areas that were randomly selected. For each sample, 16 randomly assigned square fields of view were imaged using the software autofocus adopted method, with a x10 and a x20 magnification selection. Cell nuclei were filtered using DAPI, with exposer time of 25 milliseconds; excitation level of 350/50 and emission of 455/50. The DAPI segmentation was done using global threshold modulus set to 500 gray level with minimum area of 100 μm. Cellular actin was filtered using Cy3 filter set, with exposer time of 20 milliseconds; an excitation level of 543/22 and emission of 605/64 were used. The Cy3 segmentation was done using multi scale top hat modulus; cell diameter was set to 10–150 μm. The DAPI and Cy3 imaging were acquired sequentially. Images were sampled at a resolution of 1024 by 1024 pixels, using a 20x objective (numerical aperture = 0.45) and a z-step size of 2.3 μm per layer up to 200 μm deep. The maximum optical resolution determined based on the fluorescence of isotype controls was used.

Following InCell data collection, the data files were analyzed using InCell analyzer (4.5–11440 version). DAPI data was combined with Actin-Cy3 volumes for cell identification analysis. Cell morphology stain was used to determine the cell shape parameter as detailed below. Imaris 7.7 software (Bitplane, Switzerland) was used to quantify the cell shape based on the fluorescence staining. Confocal Z-stacks images (LSM file) were loaded into the Imaris program and the fluorescence was used to segment the desired objects. A volume of interest was defined manually around the object. The total object volume (μm3), shape index, mean intensity and number of stained cells were measured by summarizing all values of each voxel within the defined volume. The cell shape index (sphericity, round=1) was measured using InCell’s algorithm. The average data in 10 distinct regions for each formulation was calculated from 3 independent constructs per formulation.

hMSC Differentiation Assessment Using FACS

hMSCs were labeled with a specific set of surface antigens that are known differentiation and multipotency markers. These include the following: a positive multipotency marker CD90-APC (BioLegend), and a negative multipotency marker: CD105-FITC (BioLegend). Differentiated hMSCs were labeled with a set of antigens that are known to indicate differentiation along either a chondrogenic, neurogenic or myogenic lineage. For chondrogenesis, the specific markers include: CD151 (APC), CD49c (APC), CD44 (FITC), and Sox9 (NL557). For myogenesis, the specific markers were MyoD (ex-647), Desmin (647), Myogenin (488), S.M.Actin (488), and Myosin H.C (488). For neural and Glial cells, we used the pre-neural marker Vimentin (488), the neural marker β-Tubulin-III (650-APC), and the glial marker GFAP (585). All differentiation experiments were performed together with the control pluripotency markers: CD90-APC (positive) and CD105-FITC (negative). Surface marker staining was performed for 20 min on ice according to the manufacturer’s recommendations (Flow kit protocol, BD pharmingen). Briefly, the hMSCs were washed in PBS and incubated on ice with the markers for 20 min and washed again in PBS. After the cells were mildly centrifuged for 5 minutes, they were fixed in 10% formalin in PBS (Sigma) for 30 minutes at room temperature. Cells were measured using a flow cytometer (LSR-II) having the appropriate settings for the respective fluorescent stains, and the data was analyzed using FCS express software.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was summarized using Microsoft® Excel software; FACS data analysis was performed using FCS express 4 software. Image analysis was quantified using Imaris and InCell software. Data from independent experiments were quantified and analyzed for each variable. Each treatment was represented by at least three independent experiments (performed in triplicates), unless stated otherwise. Comparisons between two treatments were made using Student’s t-test (two-tailed, unequal variance) and comparisons between multiple treatments were made by analysis of variance (ANOVA). A p-value of <0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Results

hMSC Viability in 3D Culture

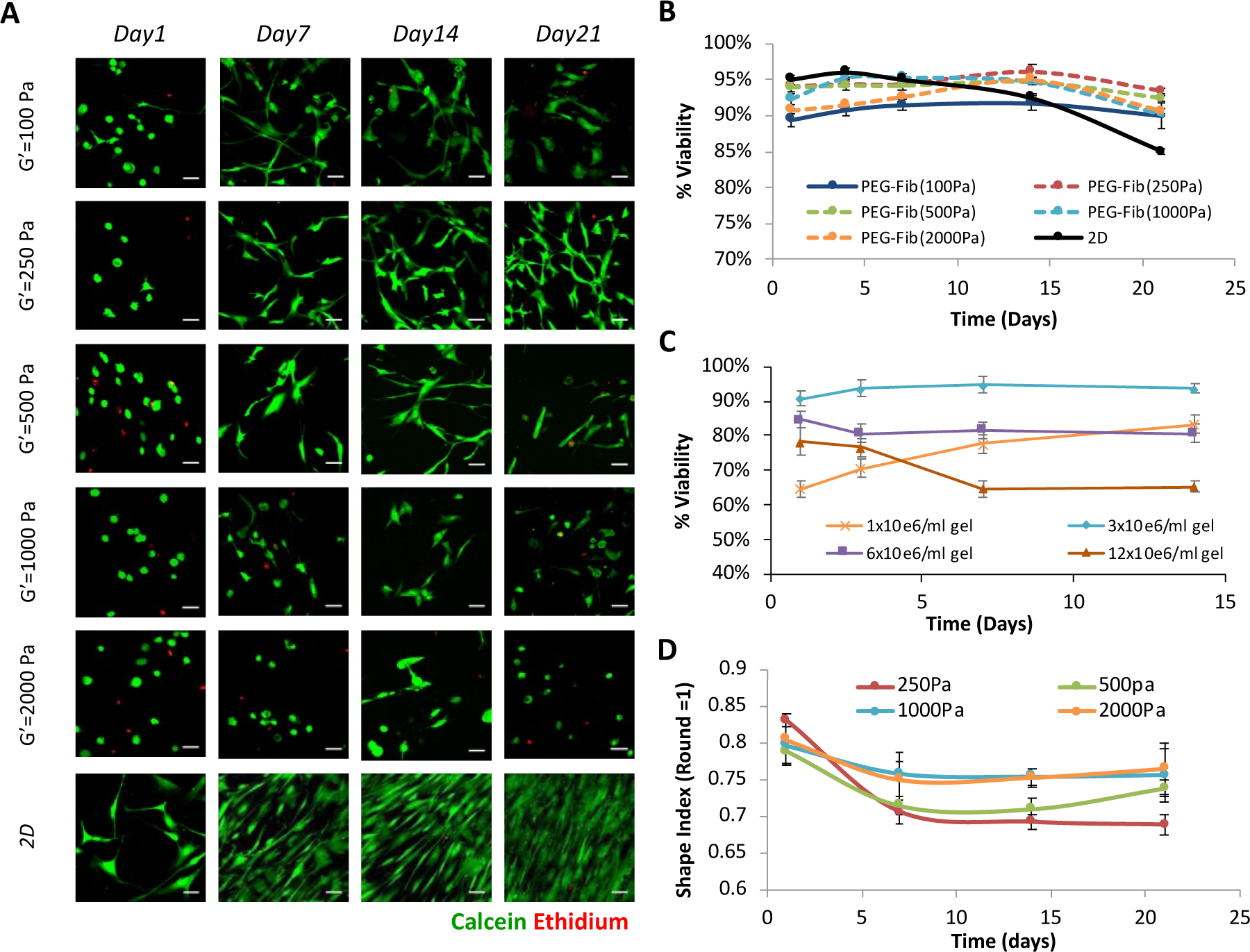

The hMSC viability in the PF hydrogels was verified for up to 21 days in 3D culture using expansion medium (i.e., MSCGM) and PF formulations resulting in different shear storage moduli (i.e., bPF 100, bPF250, bPF500, bPF1000, and bPF2000). A initial cell seeding concentration of 3×106 cells/ml was used for these experiments. Live/dead staining of the cells within the constructs confirmed that a high population of the encapsulated cells in the hydrogel are viable (Figure 2a). The live/dead staining also confirmed that there was no apparent disruption to cell viability associated with the increased stiffness of the gels (Figure 2a). Quantitative cell viability measurements performed with PI staining of the samples verified the qualitative results (Figure 2b). A two-way ANOVA did not reveal statistically significant differences in viability among treatments. Cells grown on tissue culture plastic dishes (2D) were used as controls.

Figure 2.

Modulus-dependent viability of hMSCs in 3D-PF hydrogels. (A) Live-dead staining of hMSCs in PEG-fibrinogen hydrogels (3×106 cells/ml) grown in expansion medium for up to 21 days; the modulus of the hydrogels did not affect the viability of the cells (scale bar=25μm). (B) Quantitative viability with DNA staining using propidium iodide (PI) confirms the qualitative results of hMSCs seeded in the different modulus PEG-Fib hydrogels. Cells grown on tissue culture plastic dishes (2D) were used as controls. (C) The effect of cell seeding density on hMSC viability was assessed in PF hydrogels with a G’=250Pa modulus, grown in expansion medium for up to 14 days. The highest percent of viable cells was evident in hydrogels made with a hMSC concentration of 3×106cells/ml. The viability data is presented as the average plus/minus standard deviation; a significant difference between the treatments was observed by 2-way ANOVA (p < 0.05) (D) The morphology of hMSCs in the 3D-PF hydrogels was quantitatively evaluated for hMSCs in PEG-fibrinogen hydrogels (3×106 cells/ml) grown in expansion medium for up to 21 days. The shape index (round=1) was calculated using the Imaris software; the initially rounded cells become more elongated over time as the cells spread three-dimensionally in the PF matrix. The shape index of the hMSCs was quantified as a function of hydrogel modulus to reveal a significant difference between the treatments (2-way ANOVA, p < 0.05).

The effects of cell seeding density on the viability was also quantitatively assessed. For these experiments, the viability in the PF hydrogels was quantified for up to 14 days in 3D culture using expansion medium (i.e., MSCGM) and a PF formulation resulting in a shear storage modulus of approximately G’= 250 Pa (i.e., bPF250). Four different cell-seeding densities were used to prepare the hydrogels, including 1, 3, 6 and 12 million cells per ml of PF solution; the viability in the hydrogels was determined for each cell seeding density. The viability 24 hours after cell seeding was 65%, 90%, 85% and 78% for the 1, 3, 6 and 12×106 cell/ml hydrogels, respectively (Figure 2c). After 14 days in culture, the highest levels of cell viability were observed in the hydrogels seeded with 3×106 cell/ml (94%); whereas the lowest levels of viability were observed in the 12×106 cell/ml hydrogels (65%). The other two treatments exhibited 80% viability after 14 days in culture. A statistically significant difference in cell viability was attributed to the cell seeding density (two-way ANOVA, p<0.05). The optimal hMSCs seeding density of 3×106 cell/ml was used in all subsequent differentiation experiments.

Laser scanning confocal microscopy (LSCM) was used to quantify hMSC morphogenesis as a function of hydrogel modulus for up to 21 days in 3D culture using expansion medium (i.e., MSCGM). The PF formulations used for this experiment provided different shear storage moduli of between 250–2000Pa (i.e., bPF250, bPF500, bPF1000, and bPF2000). The shape index of the cells was determined for day 1, 7, 14, and 21 after seeding. The initially rounded cells become more elongated over time and the modulus of the hydrogel has a significant impact on the final morphology (two-way ANOVA, p<0.05) (Figure 2D).

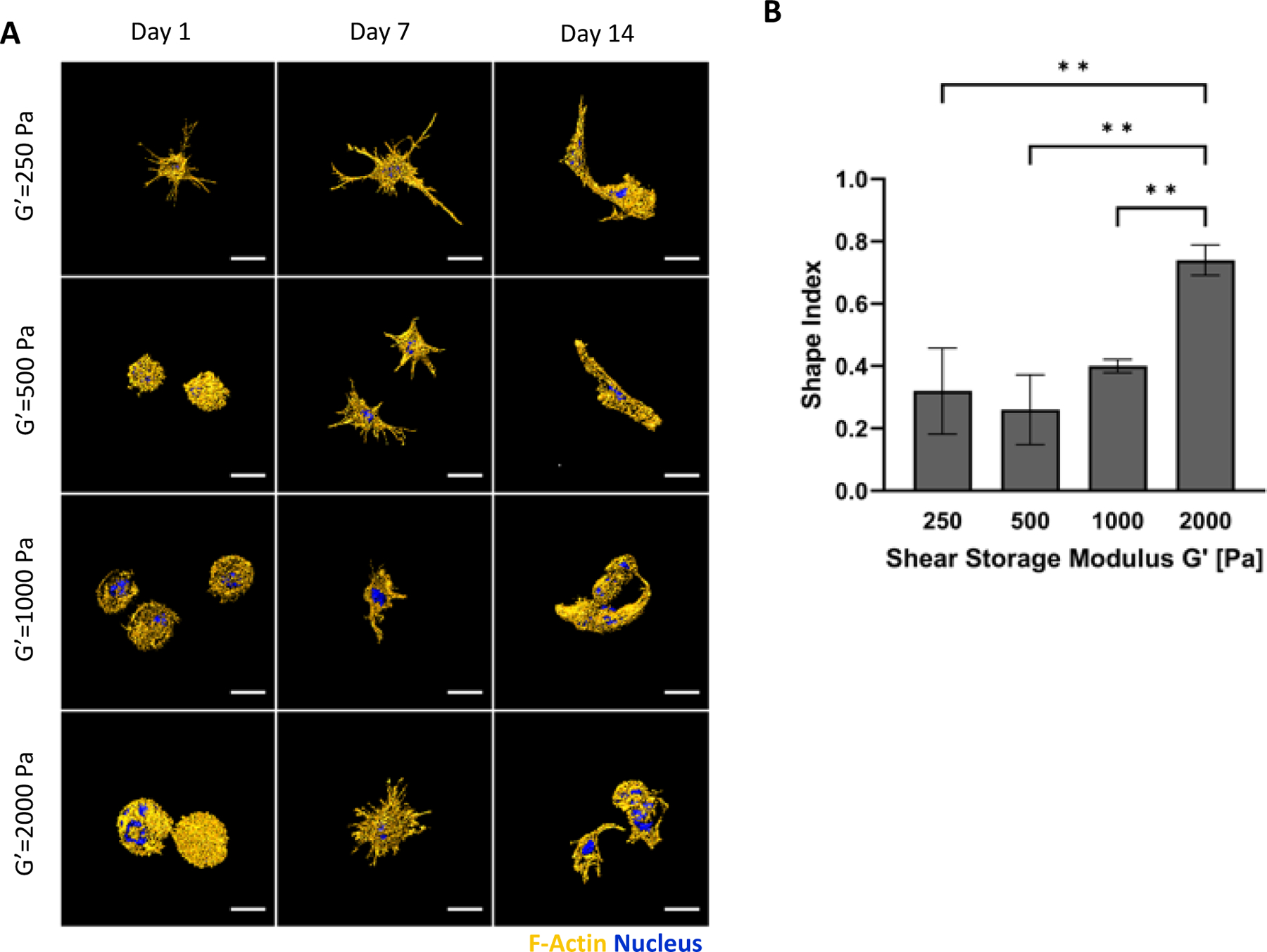

Chondrogenesis

The hMSCs seeded in the 3D PF hydrogels were cultured for 14 days using chondrogenic differentiation medium. Four PF formulations were tested to make hydrogels with shear storage modulus values of approximately G’= 250 Pa, 500 Pa, 1000 Pa, and 2000 Pa (i.e., bPF250, bPF500, bPF1000, and bPF2000). The hMSC morphogenesis within the PF hydrogels was influenced by the initial modulus of the hydrogel. One the first day of culture, cell morphology in the lower modulus gels was spindled (Figure 3a) whereas higher modulus treatments (e.g., bPF1000 and bPF2000) did not exhibit lamellipodia and cell extensions. LSCM, used to quantify the hMSC morphogenesis as a function of hydrogel modulus, provided shape index data in chondrogenic medium at day 14 after seeding. The shape index after 14 days in the bPF2000 treatment was significantly higher than all other treatments (i.e., the cells were more rounded and less spindled) (p<0.01, n=6) (Figure 3b). Cells in the bPF250, bPF500 and bPF1000 treatments exhibited more spindled morphologies after 14 days, as indicated by a shape index of below 0.5. However, there was no significant difference observed in the shape index among these treatments (p>0.05, n=6). Consequently, shape index during chondrogenesis increases as MSCs differentiate to chondroblasts and finally become chondrocytes.

Figure 3.

Modulus-dependent morphometric analysis of hMSCs after 14 days in 3D PF hydrogels cultured in chondrogenic medium. (A) Representative confocal microscopy Imaris image segmentations of 3D hMSCs cultured in the 3D hydrogels. The cells are stained with an actin stain (orange) and a nucleus counterstain (Blue); Scale bar=25μm. (B) The shape index of the hMSCs was quantified as a function of modulus, indicating a correlation between cellular extensions and storage shear modulus (G′) after 14 days. The shape index (round=1) was calculated using the Imaris software. Data is presented as the average plus/minus standard deviation. **Indicates statistically significant differences between the modulus treatments (p < 0.01).

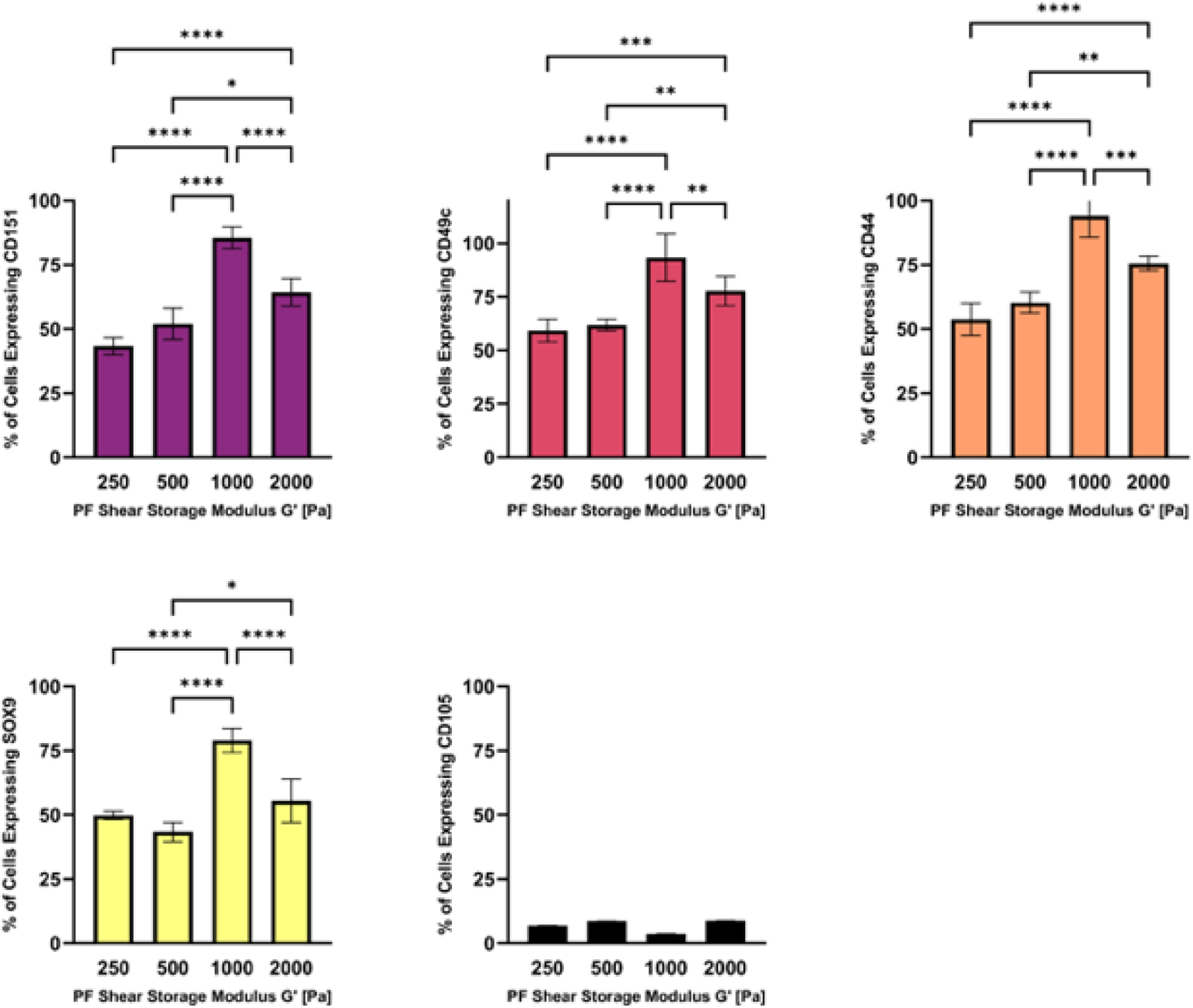

The hMSCs within the PF hydrogels were characterized for differentiation markers after 14 days in 3D culture using FACS analysis. Following the hydrogel dissolution and cell recovery, the number of cells expressing chondrogenic and multipotent markers within the hMSC population was quantified using threshold levels for each respective marker (Figure 4). The bPF1000 treatment showed a significantly higher number of cells expressing chondrogenic differentiation markers CD151, CD49c, CD44, and sox9, when compared to all the other treatments (p<0.01, n=6). The bPF1000 treatment also showed a significantly lower number of cells expressing the multipotency marker CD105 (p<0.01, n=6) compared to all other treatments (p<0.01, n=6). Taken together, these data suggest that hMSC chondrogenesis is optimal in PF hydrogels with a modulus of 1000 Pa. The PF hydrogels with a modulus 2000 Pa (bPF2000) showed similar trends in hMSC chondrogenesis, although differences in expression patterns were not statistically significant when compared to the expression patterns in lower modulus hydrogel treatments (bPF250 and bPF500) (p<0.01, n=6). The FACS analysis was verified by immunofluorescence staining of key chondrogenic markers in the treated samples (Supplementary data).

Figure 4.

The modulus-dependent chondrogenic differentiation of hMSCs in 3D PF hydrogels was evaluated after 14 days in chondrogenic medium. Specific markers measured by flow cytometry include CD151, CD49c, CD44, Sox9 and CD105 (negative marker). Data is presented as the average plus/minus standard deviation. Statistically significant differences between the modulus treatments are indicated on the graphs: *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001; ****p < 0.0001.

Myogenesis

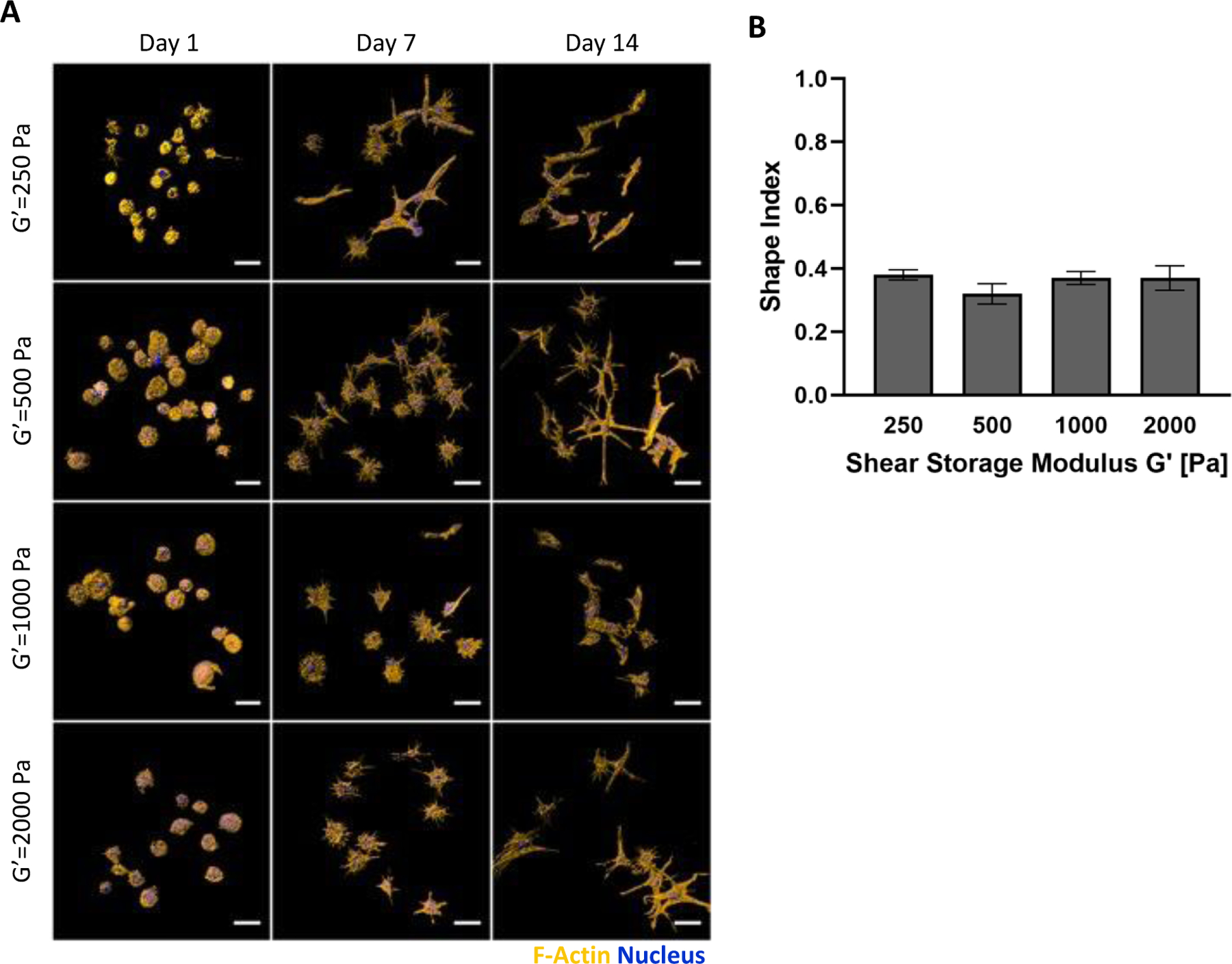

The hMSCs in PF hydrogels grown in myogenic medium were characterized for morphogenesis and myogenic differentiation markers. The hMSC morphogenesis within the PF hydrogels was not affected by the initial modulus of the hydrogels. All the treatments exhibited cells with rounded morphologies one the first day of culture (Figure 5a). By day 7 in culture, the cells exhibited a more spindled morphology in all treatments, leading to a highly spindled morphology by day 14 in culture. LSCM quantification of hMSC morphogenesis as a function of hydrogel modulus revealed that all treatments promoted high levels of spindled morphologies in the cellular population as indicated by the relatively low shape index (i.e., <0.5). The shape index of the different treatments ranged from 0.32 to 0.38 (Figure 5b). Cells in the bPF500 treatment exhibited a trend towards slightly more spindled morphologies after 14 days; however, these differences did not prove to be statistically significant (p>0.05, n=6). Myogenesis is generally associated with spindled morphologies as rounded quiescent cells undergo shape change to spindled muscle progenitors that eventually fuse to form myotubes.

Figure 5.

Modulus-dependent morphometric analysis of hMSCs after 14 days in 3D PF hydrogels cultured in myogenic medium. (A) Representative confocal microscopy Imaris image segmentations of 3D hMSCs cultured in the 3D hydrogels. The cells are stained with an actin stain (orange) and a nucleus counterstain (Blue); Scale bar=25μm. (B) The shape index of the hMSCs was quantified as a function of modulus, indicating a correlation between cellular extensions and storage shear modulus (G′) after 14 days. The shape index (round=1) was calculated using the Imaris software. Data is presented as the average plus/minus standard deviation. Statistically significant differences between the modulus treatments were not observed (p>0.05).

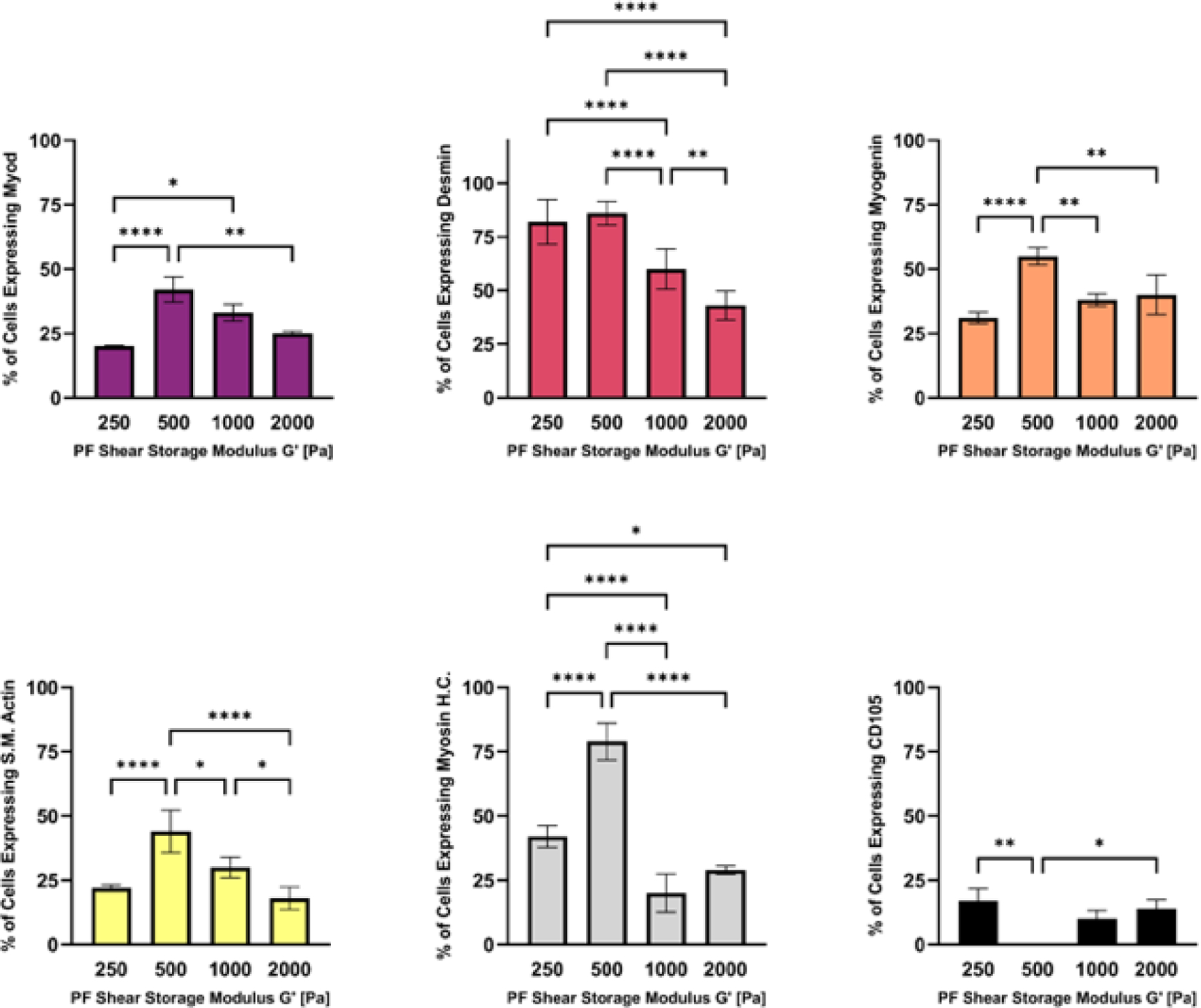

In terms of the myogenic differentiation markers of the hMSCs within the PF hydrogels, characterization was assessed by FACS analysis after 14 days in 3D culture. The hydrogels were dissolved and the recovered population of hMSCs were counted for the number of cells expressing myogenic and multipotent markers using threshold levels for each respective marker (Figure 6). The bPF500 treatment showed a significantly higher number of cells expressing myogenic differentiation markers MyoD, Desmin, Myogenin, S.M. Actin, and Myosin H.C., when compared to all the other treatments (p<0.01, n=6). There were no cells expressing the multipotency marker CD105 in the bPF500 treatment; whereas all other treatments had some cells that expressed threshold levels of CD105. Taken together, these data suggest that hMSC myogenesis is optimal in PF hydrogels with a modulus of 500 Pa. The FACS analysis was verified by immunofluorescence staining of key myogenic markers in the treated samples (Supplementary data).

Figure 6:

The modulus-dependent myogenic differentiation of hMSCs was evaluated after 14 days in 3D PF hydrogels cultured in myogenic medium. Specific markers measured by flow cytometry include MyoD, Desmin, Myogenin, S.M.Actin, Myosin H.C. and CD105 (negative marker). Data is presented as the average plus/minus standard deviation. Statistically significant differences between the modulus treatments are indicated on the graphs: *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001; ****p < 0.0001.

Neurogenesis

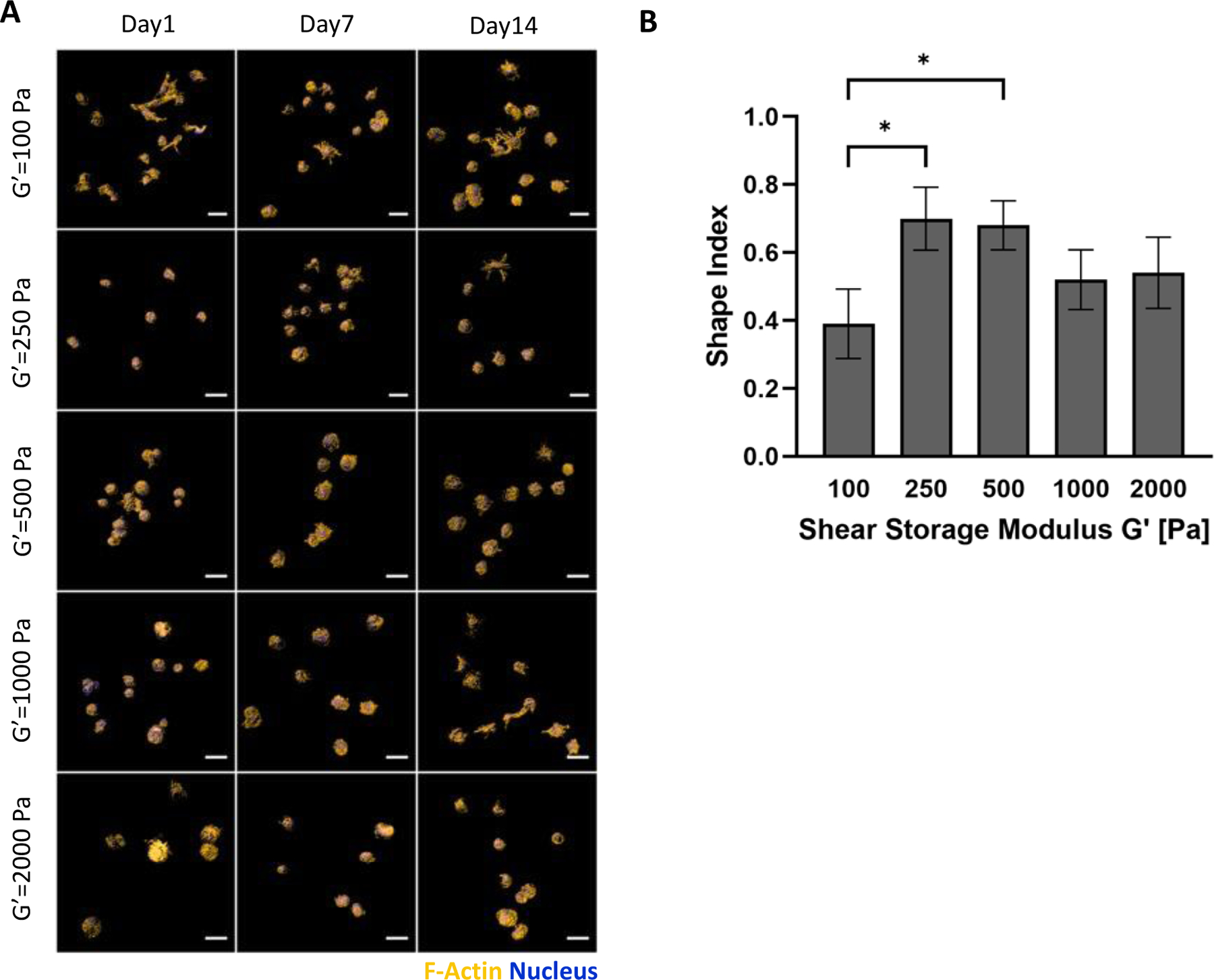

Neurogenesis medium was used with hMSCs in PF hydrogels to evaluate the cells in terms of their morphology and differentiation. The morphogenesis of the hMSC within the PF hydrogels was not affected by the initial modulus of the hydrogels when comparing bPF250, bPF500, bPF1000, and bPF2000 (p>0.05, n=6). The hMSCs remained mostly rounded started from the first day of culture throughout the 14-day cultivation, with a shape index >0.5 after 14 days in all treatments with a modulus higher than G’=250 Pa. Only a few cells exhibited lamellipodia and cell extensions, mostly notably in the bPF250 treatment (Figure 7a). Quantification by LSCM confirmed these observations; shape index was not statistically different in any of the four treatments with modulus ranging from 250–2000 Pa (i.e., bPF250, bPF500, bPF1000, and bPF2000) (Figure 7b). A lower modulus PF hydrogel was also tested using the neurogenesis medium; this PF formulation resulted in a shear storage modulus of approximately G’= 100 Pa (i.e., bPF100). The shape index of the hMSCs in the bPF100 treatment proved to be statically lower than the bPF250 and bPF500 treatments (p<0.05, n=6). Neurogenic differentiation is associated with elongated morphologies as the rounded progenitor cells undergo shape change to the more spindled astrocytes, neurons and oligodendrocytes.

Figure 7.

Modulus-dependent morphometric analysis of hMSCs after 14 days in 3D PF hydrogels cultured in neurogenic medium. (A) Representative confocal microscopy Imaris image segmentations of 3D hMSCs cultured in the 3D hydrogels. The cells are stained with an actin stain (orange) and a nucleus counterstain (Blue); Scale bar=25μm. (B) The shape index of the hMSCs was quantified as a function of modulus, indicating a correlation between cellular extensions and storage shear modulus (G′) after 14 days. The shape index (round=1) was calculated using the Imaris software. Data is presented as the average plus/minus standard deviation. *Indicates statistically significant differences between the modulus treatments (p < 0.05).

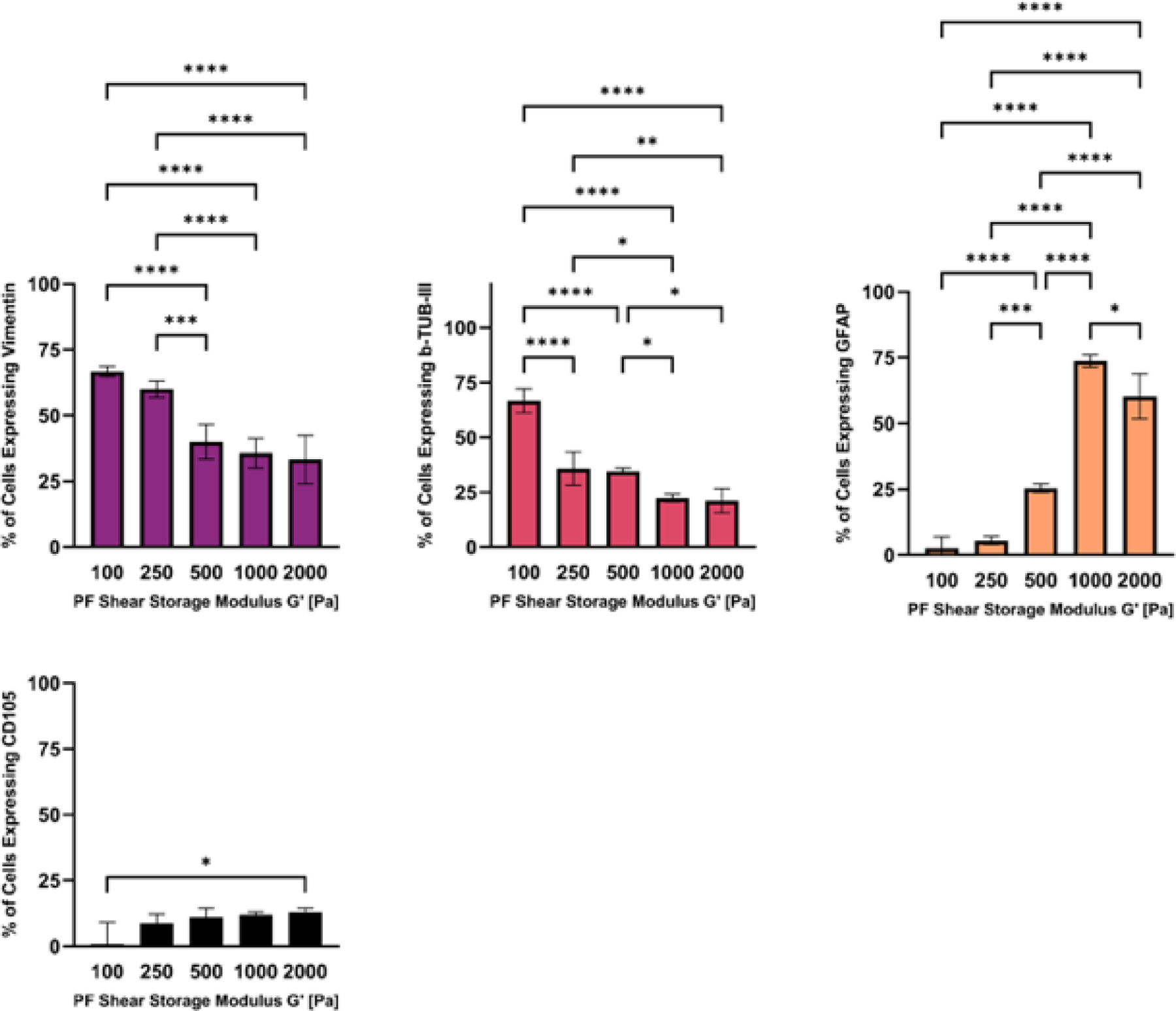

The differentiation markers that indicate neurogenesis of hMSCs were assessed by FACS analysis after 14 days in 3D culture. The recovered population of hMSCs were counted for the number of cells expressing neurogenic and multipotent markers using threshold levels for each respective marker (Figure 8). The bPF100 and bPF250 treatments showed a significantly higher number of cells expressing neurogenic differentiation markers Vimentin when compared to all the other treatments (p<0.01, n=6). The bPF100 treatment showed a significantly higher number of cells expressing neurogenic differentiation markers beta-tubulin-III, when compared to all the other treatments (p<0.01, n=6). The bPF1000 and bPF2000 treatments showed a significantly higher number of cells expressing glial cell differentiation markers GFAP when compared to all the other treatments (p<0.01, n=6). There were significantly fewer cells that expressed threshold levels of CD105 multipotency marker in the bPF100 treatment compared to the bPF2000 treatment (p<0.05, n=6). Taken together, these data suggest that hMSC neurogenesis towards neurons is optimal in PF hydrogels with a lower modulus (i.e., bPF100 and bPF250), whereas hMSC glial differentiation may be preferred in the higher modulus formulations (i.e., bPF500, bPF1000 and bPF2000).

Figure 8.

The modulus-dependent neurogenic differentiation of hMSCs after 14 days in 3D PF hydrogels cultured in neurogenic medium. Specific markers measured by flow cytometry include the pre-neural marker Vimentin, neural marker β-Tubulin-III, glial marker GFAP, and CD105 (negative marker). Data is presented as the average plus/minus standard deviation. Statistically significant differences between the modulus treatments are indicated on the graphs: *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001; ****p < 0.0001.

Discussion

The application of hMSCs for clinical therapy will require large populations of these cells to become fully differentiated under defined in vitro culture conditions. The standard practice for isolating and expanding hMSCs often uses highly rigid two-dimensional (2-D) tissue culture plates or flasks, despite overwhelming evidence that substrate modulus can alter the self-renewal or differentiation pathways of these cells[REF]. Additionally, studies have identified distinct regions in tissues that provide a three-dimensional (3-D) microenvironment for stem cells to sustain their undifferentiated, self-renewable state. These tissue regions are otherwise known as the stem-cell niche, and they possess unique biochemical and biomechanical properties52. Recently, it is becoming evident that stem cells interact with biophysical cues of the 3D niche microenvironment to regulate cell fate and differentiation. Many studies have demonstrated this biophysical phenomenon using mimics of the niche microenvironment. Certain biological cues provided to hMSCs have been shown to enhance their differentiation towards osteogenesis, chondrogenesis, myogenesis, neurogenesis and adipogenesis. However, many of these studies employ soft substrates onto which 2D cultures of stem cells are examined in response to changes in physical properties of the substrate53. Far fewer studies explore this topic using 3D cultures of hMSCs within encapsulating hydrogels. Hence, there is a growing consensus for the need to recreate the 3-D niche microenvironment when cultivating, expanding, or differentiating hMSCs as part of a bioprocessing paradigm leading to their clinical use. In this context, hydrogel biomaterials have evolved to function as sophisticated substrates and scaffolds for 3-D stem cell cultivation54, with the aim of recreating parts of the stem-cell niche by controlling their biophysical and/or biochemical properties55–57.

Previously, we used a PEG-fibrinogen (PF) hydrogels to grow stem cells in 3D and study their response to the encapsulating matrix58,59. We used PF to expand hMSCs in 3-D culture, using matrix modulus and biochemical formulations to control pluripotency and self-renewal11,51. A set of PF properties were identified specifically to maximize hMSC proliferation within the 3-D hydrogel during a 14-day culture period inside a stirred-flask bioreactor, including a shear storage modulus of G’=250 Pa and a PF formulation containing 5% fibronectin and 2% von Willebrand factor (vWF). However, the optimal hydrogel formulation for proliferation may not be ideal for hMSC differentiation because many of the hMSCs extracted from the hydrogels expressed multipotency positive marker including CD90, and few of these cells expressed the differentiation marker CD31. We now continue our earlier studies to explore how PF hydrogel modulus can enhance hMSC differentiation along a chondrogenic, myogenic or neurogenic pathway. To achieve this goal, we controlled the shear storage modulus of hydrogels made from bovine PF (i.e., bPF) by increasing the relative concentration of additional PEG-DA in the formulation as detailed in Table 1. Whereas previously we used fibronectin and vWF in the bPF formulation51, the current study did not incorporate these factors because we sought to limit the proliferation of the hMSCs in favor of their differentiation towards a specific pathway. Goldshmid et al. showed that hMSC proliferation in the PF hydrogels was affected by fibronectin and vWF in the formulation, and eliminating one of these from the hydrogel can significantly reduce proliferation51. We cultivated the hMSCs in a defined lineage-specific differentiation medium as specified by the cell supplier, seeking to identify hMSC differentiation maxima for PF hydrogels having a modulus of between G′ = 100 Pa and G′ = 2000 Pa.

The viability of the hMSCs in their multipotent state within the hydrogels was first optimized by seeding the cells within the PF hydrogel at different densities and quantifying viability in cell expansion medium. The importance of cell seeding density on the cell growth in the constructs was evidenced by the significant differences that seeding density had on the overall viability of cells within the constructs. Consequently, an optimal seeding density of 3×106 cells/ml was chosen based on >90% viability during each time-point over the 14 days in culture. We have previously shown that hMSC cell seeding density in PF hydrogels can affect the viability of the cells and these results are consistent with those findings51. Beyond cell viability, the seeding density may also have more consequences in the context of 3D MSCs cultures in hydrogels including altered proliferation and differentiation. For example, Ferreira et al. cultured hMSCs in hyaluronic acid (HA) PEG hydrogels, using either a low density or high-density formulation (5×105 and 5×106 cells/ml) to observe the role of initial cell seeding on proliferation and differentiation in 3D culture60. They observed that hMSC in high density cultures released factors that suppressed differentiation that were typically observed in low density cultures. Others have made opposite observations related to paracrine signaling of high density hydrogel cultures of MSCs in relation to differentiation and quiescence of these cells in 3-D culture61,62. Qazi et al demonstrate that MSC paracrine signaling from high density cultures can promote differentiation in hydrogels scaffolds62.

Using the viability-optimized hMSC seeding density of 3×106 cells/ml, we explored the differentiation of the hMSCs within the bPF hydrogels along three lineages that have been previously documented for these cells, including chondrogenesis, myogenesis and neurogenesis. We found modulus-enhanced differentiation patterns along all three lineages, with G’=1000Pa favoring chondrogenesis, G’=500Pa favoring myogenesis and G’=100Pa favoring neurogenesis (i.e., neuronal differentiation). The lineage-specific differentiation patterns were assessed quantitatively using protein expression profiles known for each respective lineage. For example, for chondrogenic differentiation, Derfoul et al. showed that chondrogenesis in adult human mesenchymal stem cells can be measured by the gene expression of differentiation markers that included CD151, CD49c, CD44, and sox963. Campbell and Pei showed that these chondrogenic markers can also be used for identifying differentiation of synovium-derived stem cells into chondrocytes64. For myogenesis, we chose a subset of differentiation markers that are expressed when adult muscle skeletal satellite cells undergo myofiber formation, including MyoD, Desmin, Myogenin, S.M. Actin, and Myosin heavy chain65. Neurogenesis was evaluated based on expression of vimentin, which is typically used as a marker for early neurogenesis66. The later-stage neural marker β-Tubulin-III was also used for neuronal differentiation, whereas the glial marker GFAP was used to differentiate between neuronal and glial development66. Table 2 summarized the percent of cells expressing the key differentiation markers within each hydrogel formulation for each lineage respective culture condition. Table 2 also shows the percent cells undergoing proliferation and self-renewal in expansion medium, as previously reported in our earlier investigation51.

Table 2.

The percent of cells expressing the key differentiation markers within each hydrogel formulation for each lineage respective culture condition (data is presented as the average plus/minus standard deviation). The data on proliferation and self-renewal in expansion medium, as previously reported, was reproduced by permission from51.

| Formulation | Proliferation (%BRDU) | Self-renewal (%CD90) | Differentiation (% cells expressing differentiation markers) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chondrogenic Marker CD151 | Myogenic Marker S.M. Actin | |||||

| GFAP | ||||||

| G’=100 Pa | 81.8% | 76.3% | NA | NA | 66.7% | 2.5% |

| G’=250 Pa | 86.9% | 92.44% | 43.32% | 42% | 35.8% | 5.4% |

| G’=500 Pa | 74.8% | 68.02% | 52.05% | 79% | 34.6% | 25.4% |

| G’=1000 Pa | 59.7% | 64.33% | 85.55% | 20% | 22.4% | 73.7% |

| G’=2000 Pa | 37.7% | 64.96% | 64.26% | 20% | 21.2% | 60.1% |

There have been many publications in the past fifteen years on stem cells and 3D culture in hydrogels; however, few studies have concurrently evaluated hMSCs differentiation into these three lineages to study how this process is affected by material modulus of the 3D culture matrix. Among the studies that did evaluate modulus-dependent differentiation of hMSCs in 3-D hydrogel cultures, Jooybar et al. explored only chondrogenic differentiation of cultured bone marrow derived hMSCs in hydrogels made from hyaluronic acid enriched with platelet lysate (HA-PL). They evaluated several hydrogel formulations with shear storage moduli ranging from ~500Pa to ~2000Pa and documented highest chondrogenesis in the hydrogel formulations having a modulus of ~1000Pa67. Feng et al. observed similar patterns in chondrogenic differentiation of murine hMSCs derived from bone marrow when these cells were cultured three-dimensionally in hydrogels of hyaluronic acid and methacrylated gelatin18. They document optimal chondrogenesis in hydrogels having a shear storage modulus of ~1000Pa. Hong et al. cultured murine hMSCs in thermosensitive hydrogels made from poly(organophosphazene) bearing β-cyclodextrin (β-CD PPZ) and two types of adamantane-peptides (Ad-peptides) that are associated with mesenchymal stem cell (MSC) differentiation. They documented enhanced chondrogenesis in formulations having a shear storage modulus in the range of 500–1000Pa68. We found a local maximum in expression of chondrogenic markers by the hMSCs in the bPF hydrogels with a shear modulus of G’=1000Pa. Our results are generally consistent with these previous findings, even though differences between scaffold composition, cell seeding densities and hydrogel formulations can confound comparisons across the different 3D culture platforms.

The hMSCs grown in the PF hydrogels under myogenic conditions were distinctly responsive to a matrix modulus of G’=500 Pa in terms of maximal expression of myogenic differentiation markers. In the case of myogenesis, far fewer reports were found evaluating MSCs in 3-D culture and using hydrogel modulus to alter differentiation. Of those studies that did report on this topic, Xu et al. showed that rat MSCs cultured in 3-D hydrogels made from thermosensitive polymers comprised of N-isopropylacrylamide (NIPAAm), acrylic acid (AAc), and degradable macromer 2-hydroxyethyl methacrylate-oligomer were myogenically responsive to hydrogel modulus. They found that modulating the hydrogels elastic modulus between 11, 20, and 40 kPa, produced a local maximum of myogenic differentiation in the rat MSCs at a modulus of 20 kPa after 14 days in 3D culture69. The hydrogel modulus they found to promote myogenesis was nearly an order of magnitude higher when compared to our own findings. This difference may be due to the type of cells used by Xu et al., namely rat MSCs versus hMSCs in our study. Moreover, significantly different hydrogel formulations were used in the two studies, which further confounds comparisons of the two results.

Consequently, several studies evaluated MSC myogenesis in 2-D culture on hydrogel with altered modulus. Wang et al. cultured hMSCs on gelatin-hydroxyphenylpropionic acid (Gtn-HPA) hydrogels made with different modulus to show how myogenesis and neurogenesis was affected by the mechanical properties of the gel. They found myogenesis was favored on hydrogels with a modulus of 12,000 Pa whereas neurogenesis was favored on materials with a modulus of 600 Pa. Others have evaluated different cell types cultured on hydrogels with the aim of identifying modulus-dependent myogenic differentiation patterns. Madle et al. reported on skeletal muscle stem cells (MuSCs) cultured on synthetic poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG) hydrogels crosslinked by the bio-orthogonal strain-promoted azide-alkyne cycloaddition (SPAAC) reaction. They showed that MuSC cultured on soft hydrogels (10 kPa) promotes expansion and activation of the cells whereas proliferation and myogenesis were both impaired when the cells were cultured on stiffer hydrogels (40 kPa). Although comparing data obtained from the culture of different cell types, different hydrogel formulations and different culture conditions (i.e., 2-D and 3-D culture) is not straightforward, it is noteworthy that all these studies did observe modulus-dependent myogenesis irrespective of their differences.

The modulus-dependent neurogenic differentiation of the hMSCs in 3-D bPF hydrogels was assessed using both early and late-stage neurogenic markers. For the early neurogenic marker GFAP, maximum expression was observed in the modulus range of G’=1000–2000 Pa. GFAP is a type III intermediate filament (IF) protein that is expressed by numerous cell types of the central nervous system (CNS), including astrocytes70. For the later-stage neurogenic markers vimentin and β-Tubulin-III, maximum expression of both was observed in the modulus range of G’=100Pa. Taken together, these data suggest that hMSC differentiation towards axonal development is enhanced in the softest hydrogel cultures with the neurogenic culture medium; whereas in the absence of sufficiently soft 3-D culture conditions, the hMSCs will differentiate towards neuronal astrocytes. Others have shown that matrix remodeling is critically important for neural progenitor cell (NPCs) differentiation into neurons and astrocytes in 3D hydrogels. Madl et al. cultured NPCs in three types of hydrogels exhibiting proteolytic responsiveness and documented stemness, self-renewal, and induced differentiation in culture medium containing Neurobasal-A, 2% B27 Supplement, GlutaMAX, 1% fetal bovine serum (FBS), and 1 μM retinoic acid. They found that maintenance of neuronal stemness is better correlated to biodegradability of the hydrogels as compared to hydrogel modulus, ligand clustering or cytoskeletal force generation. NPC self-renewal required remodeling of the hydrogel and was accompanied by downstream β-catenin signaling that maintains NPC stemness71. Biochemical induction of NPC differentiation after matrix remodeling resulted in progression towards astrocytes and neurotransmitter-responsive neurons72.

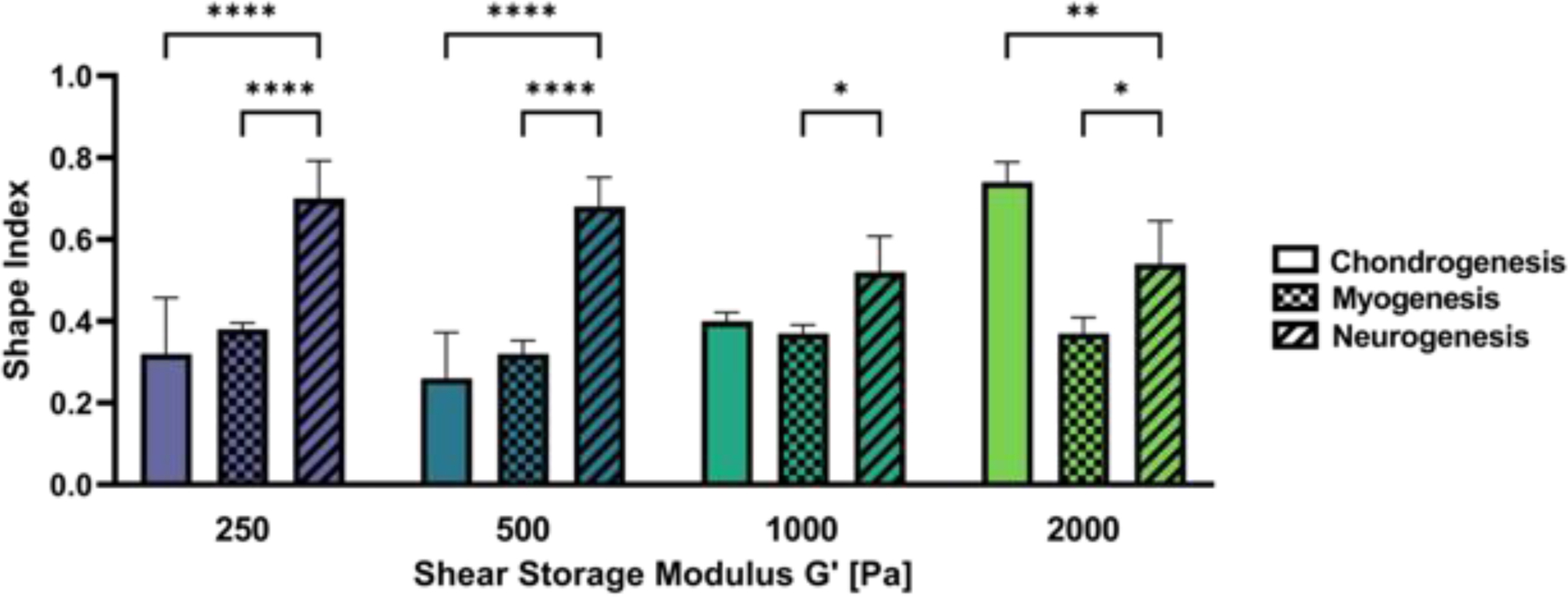

One advantage of our approach in this study is the ability to compare modulus-dependent and modulus-independent stem cell response across three differentiation pathways that are guided only by the alteration of differentiation media. These comparisons allow quantitative observations on how biochemical agonists and biomechanics can interact to alter cell response. For example, myogenic media prompted spindled cell morphology in all modulus treatments, as indicated by a shape index of <0.4, whereas neurogenic media enabled spindled morphologies (i.e., shape index <0.4) only is those hydrogels with a modulus of 100 Pa. Despite large differences in hydrogel modulus, all the hMSCs eventually become highly oriented when cultured in hydrogels with the myogenic medium. In contrast, neurogenic medium appears to heighten the modulus-dependency of the morphogenic response of the hMSCs, even after 14 days in 3D culture. Figure 9 summarized the quantitative analysis of the modulus-dependent morphometric response of the hMSCs in the hydrogels at day 14 in culture. These data underscore the important role of biochemical stimulation on hMSC morphology in 3D culture. Similar comparisons indicate the important role of biochemical stimulation in self-renewal. Specifically, the percent of stem cells expressing CD105, a self-renewal marker, are generally very low in most treatments (i.e., <10%) but tend to be higher for cells grown in myogenic medium. These types of comparisons are particularly helpful for evaluating the relative importance of biochemical and biomechanical agonists when considering the multitude of microenvironmental factors of a 3D culture milieu.

Figure 9:

Modulus-dependent morphometric analysis of hMSCs after 14 days in 3D PF hydrogels cultured in chondrogenic, myogenic and neurogenic medium. The differentiation conditions at any given modulus treatment have a significant impact on the cell morphology. Statistically significant differences between the treatments are indicated on the graph: *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001; ****p < 0.0001.

Several other important studies have evaluated modulus-dependent differentiation of various types of stem cells in 3D hydrogel cultures. Khetan et al. investigated the hMSCs in 3D HA hydrogels to show that degradation-mediated cellular traction, independently of cell morphology or matrix mechanics, affected the osteogenic and adipogenic differentiation. HA hydrogels designed for cell-mediated degradation, with cell spreading and cell traction enhanced, favored osteogenesis whereas lack of these enhanced features favored adipogenesis73. Chaudhuri et al. cultured mouse bone marrow stromal MSCs in alginate hydrogels to demonstrate how differentiation is dependent on the rate of stress relaxation in 3D culture. When cultured in hydrogels that undergo rapid relaxation rates, the MSCs undergo osteogenic differentiation and form an interconnected mineralized collagen-1 rich matrix. They showed that in the stiffer hydrogels, osteogenic differentiation was mediated primarily by ECM ligand density, enhanced RGD ligand clustering, and myosin contractility. Huebsch et al. cultured mouse and human MSCs in 3D alginate hydrogel modified with RGD peptide to investigate modulus-dependent and cell-adhesion dependent osteogenic and adipogenic differentiation. They found that osteogenic commitment of both mesenchymal stem-cell populations in these hydrogels was correlated predominantly to matrix stiffness and integrin binding. They concluded that cell fate was not correlated to cell morphology, but rather to matrix stiffness; the hydrogel stiffness regulated integrin binding and adhesion ligand reorganization affecting cell-fate determination74. However, the alginate gels in this study were prepared without the ability to undergo cell-mediated reorganization by proteolysis, thus potentially limiting cell fate determination to neurogenesis and other differentiation pathways that may require matrix remodeling. Yang et al. showed that viscoelasticity is important for mechanosensing of cells in supramolecular hydrogels75. They used HA hydrogels stabilized by reversible host–guest crosslinks with different binding kinetics to control the viscoelastic response of the gels. Human bone marrow derived MSCs cultured in the gels with a shorter crosslink lifetime and higher shear loss modulus (G”) displayed more cell spreading and greater osteogenic differentiation.

Based on these reports that fate determination of stem cells in 3D hydrogel cultures are affected by matrix remodeling, cell adhesion, cell traction, and material properties (i.e., stress relaxation and material modulus), one needs to recognize the limitations of any single study that does not take all these factors, and possibly others, into account. For example, it is worth noting that the PF materials used in this study can undergo matrix remodeling by cell-mediated proteolysis. Furthermore, these materials support cell adhesion and cell-mediated traction in 3D culture. The PF hydrogel also exhibit viscoelastic properties such as stress relaxation. Importantly, these material properties are not independent of one another in the PF hydrogels. As such, alterations in modulus afforded by the additional PEG-DA in the PF system likely alter proteolytic degradation, viscoelasticity, and cell adhesion-mediated tractional forces in the matrix. Therefore, our efforts to systematically increase modulus to study stem cell fate in 3D culture is limited by our inability to keep all other contributing factors constant in this material system. Indeed, this multifactorial interdependence of any material system underscores the complexities of this type of investigation. In our hydrogel system, alterations in modulus by addition of PEG-DA crosslinker represents changing stiffness, porosity, and resistance to cell-mediated proteolytic degradation. Therefore, we cannot exclude any of these factors as contributing to observed modulus-dependent stem cell fate determination outcomes that are reported.

Further confounding the comparison of our results with other published findings is the fact that many of these studies employ different types of stem cell, species, materials, differentiation pathways, and physical hydrogel properties. These differences can have a profound effect on the study outcomes and conclusions, making cross-platform comparisons particularly difficult. For example, Madl et al. identified matrix remodeling and not modulus as the critical parameter for stem cell differentiation (NPCs and neurogenesis), whereas Huebsch et al. employs a hydrogel system that is not amenable to cell-mediated remolding but did find that stem cell differentiation was altered by the material modulus. Without any remodeling of the hydrogel, MSCs were guided towards osteogenic and adipogenic pathways in 3D culture using a modulus-dependent mechanism in the Huebsch et al. study. Theses seemingly contradictory results underscore the possibility of redundancy in stem cell response to physical constraints of an encapsulating hydrogel, or alternatively, it is possible that NPC simply respond very differently than mouse or human MSCs to biophysical agonists. Both explanations are plausible, and further investigations would be required to fully understand the multifactorial nature of stem cell differentiation in response to mechanical stimulation in an encapsulating 3D hydrogel milieu. Despite these limitations, it is clear from this study and the results of others that mesenchymal stem cells are partially responsive to the physical properties of their encapsulating milieu, irrespective of species and cell source.

Conclusions

This study explores the importance of tailoring mechanical properties of an encapsulating hydrogel for 3D culture of hMSC in terms of cell morphogenesis and differentiation. The differentiation medium used for 3D culture was essential to guide hMSCs towards chondrogenesis, myogenesis and neurogenesis, or to maintain the pluripotency of the cells in the hydrogels. In each of the treatments, the percentage of differentiating cells was influenced by the hydrogel modulus, leading to the conclusion that 3D culture conditions and differentiation patterns are related through matrix modulus. The morphogenesis patterns of hMSCs for the three lineages were related to the differentiation of the cells in the hydrogels; this relationship was also found to be modulus dependent. The extent of the modulus dependent morphogenesis or pluripotency of the cells was less pronounced for certain biochemical agonist, particularly for myogenesis conditions, where for example cell spreading was not influenced by the modulus after 14 days in culture. Hence, we conclude that the biochemical and mechanical stimulation of hMSCs work together to alter cell fate determination. This insight can be particularly beneficial for designing hydrogel carriers for stem cell expansion and hydrogel scaffolds for tissue engineering using stem cells.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was financially supported by the National Science Foundation (JAB: DMR Award 1610525), the USA-Israel Binational Science Foundation (DS, HSY: Award 2015697), the Israel Science Foundation (DS: Award 2130/19) and the Swiss National Science Foundation (CL).

References

- 1.Caddeo S, Boffito M, Sartori S. Tissue engineering Approaches in the Design of Healthy and Pathological In Vitro Tissue Models. Frontiers in Bioengineering and Biotechnology 2017;5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lev R, Seliktar D. Hydrogel biomaterials and their therapeutic potential for muscle injuries and muscular dystrophies. Journal of the Royal Society Interface 2018;15(138). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Berdichevski A, Yameen HS, Dafni H, Neeman M, Seliktar D. Using bimodal MRI/fluorescence imaging to identify host angiogenic response to implants. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 2015;112(16):5147–5152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ciocci M, Cacciotti I, Seliktar D, Melino S. Injectable silk fibroin hydrogels functionalized with microspheres as adult stem cells-carrier systems. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2018;108:960–971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Birman T, Seliktar D. Injectability of Biosynthetic Hydrogels: Consideration for Minimally Invasive Surgical Procedures and 3D Bioprinting. Advanced Functional Materials 2021;31(29). [Google Scholar]

- 6.Loebel C, Rodell CB, Chen MH, Burdick JA. Shear-thinning and self-healing hydrogels as injectable therapeutics and for 3D-printing. Nature Protocols 2017;12(8):1521–1541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Seliktar D, Dikovsky D, Napadensky E. Bioprinting and Tissue Engineering: Recent Advances and Future Perspectives. Israel Journal of Chemistry 2013;53(9–10):795–804. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Coronel MM, Martin KE, Hunckler MD, Kalelkar P, Shah RM, Garcia AJ. Hydrolytically Degradable Microgels with Tunable Mechanical Properties Modulate the Host Immune Response. Small 2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Headen DM, Aubry G, Lu H, Garcia AJ. Microfluidic-Based Generation of Size-Controlled, Biofunctionalized Synthetic Polymer Microgels for Cell Encapsulation. Advanced Materials 2014;26(19):3003–3008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mora-Boza A, Castro LMM, Schneider RS, Han WM, Garcia AJ, Vazquez-Lasa B, San Roman J. Microfluidics generation of chitosan microgels containing glycerylphytate crosslinker for in situ human mesenchymal stem cells encapsulation. Materials Science & Engineering C-Materials for Biological Applications 2021;120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goldshmid R, Seliktar D. Matrix modulus controls hMSC differentiation in a microgel suspension culture system. Journal of Tissue Engineering and Regenerative Medicine 2014;8:291–291.22730225 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Loebel C, Ayoub A, Galarraga JH, Kossover O, Simaan-Yameen H, Seliktar D, Burdick JA. Tailoring supramolecular guest-host hydrogel viscoelasticity with covalent fibrinogen double networks. Journal of Materials Chemistry B 2019;7(10):1753–1760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Parekkadan B, Milwid JM. Mesenchymal Stem Cells as Therapeutics. Annual Review of Biomedical Engineering, Vol 12 2010;12:87–117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lavrentieva A, Pepelanova I, Seliktar D. Tunable Hydrogels Smart Materials for Biomedical Applications Preface. Tunable Hydrogels: Smart Materials for Biomedical Applications 2021;178:V–Vi. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Seliktar D Designing Cell-Compatible Hydrogels for Biomedical Applications. Science 2012;336(6085):1124–1128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schultz KM, Kyburz KA, Anseth KS. Measuring dynamic cell-material interactions and remodeling during 3D human mesenchymal stem cell migration in hydrogels. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 2015;112(29):E3757–E3764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ledo AM, Vining KH, Alonso MJ, Garcia-Fuentes M, Mooney DJ. Extracellular matrix mechanics regulate transfection and SOX9-directed differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells. Acta Biomaterialia 2020;110:153–163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Feng Q, Gao HC, Wen HJ, Huang HH, Li QT, Liang MH, Liu Y, Dong H, Cao XD. Engineering the cellular mechanical microenvironment to regulate stem cell chondrogenesis: Insights from a microgel model. Acta Biomaterialia 2020;113:393–406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tsou YH, Khoneisser J, Huang PC, Xu XY. Hydrogel as a bioactive material to regulate stem cell fate. Bioactive Materials 2016;1(1):39–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Allen P, Melero-Martin J, Bischoff J. Type I collagen, fibrin and PuraMatrix matrices provide permissive environments for human endothelial and mesenchymal progenitor cells to form neovascular networks. Journal of Tissue Engineering and Regenerative Medicine 2011;5(4):E74–E86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hinds S, Bian WN, Dennis RG, Bursac N. The role of extracellular matrix composition in structure and function of bioengineered skeletal muscle. Biomaterials 2011;32(14):3575–3583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Discher DE, Engler AJ. Differentiation fate of human mesenchymal stem cell is influenced by substrate elasticity. Abstracts of Papers of the American Chemical Society 2005;229:U199–U199. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Engler AJ, Sweeney HL, Discher DE. Substrate elasticity alters human mesenchymal stem cell differentiation. Biophysical Journal 2005;88(1):500a–500a. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Naqvi SM, McNamara LM. Stem Cell Mechanobiology and the Role of Biomaterials in Governing Mechanotransduction and Matrix Production for Tissue Regeneration. Frontiers in Bioengineering and Biotechnology 2020;8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Discher DE, Mooney DJ, Zandstra PW. Growth Factors, Matrices, and Forces Combine and Control Stem Cells. Science 2009;324(5935):1673–1677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Saha K, Keung AJ, Irwin EF, Li Y, Little L, Schaffer DV, Healy KE. Substrate Modulus Directs Neural Stem Cell Behavior. Biophysical Journal 2008;95(9):4426–4438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.An DB, Kim TH, Lee JH, Oh SH. Evaluation of stem cell differentiation on polyvinyl alcohol/hyaluronic acid hydrogel with stiffness gradient. Journal of Tissue Engineering and Regenerative Medicine 2014;8:346–347. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Davaa G, Hong JY, Buitrago JO, Kim HW, Hyun JK. Effect of stiffness change of transplanted induced neural stem cells after spinal cord injury using silk hydrogel. Journal of the Neurological Sciences 2017;381:286–286. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Holle A, Engler A. Focal Adhesion Mechanotransduction Regulates Stiffness-Directed Myogenesis in Mesenchymal Stem Cells. Molecular Biology of the Cell 2013;24. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gilbert PM, Havenstrite KL, Magnusson KEG, Sacco A, Leonardi NA, Kraft P, Nguyen NK, Thrun S, Lutolf MP, Blau HM. Substrate Elasticity Regulates Skeletal Muscle Stem Cell Self-Renewal in Culture. Science 2010;329(5995):1078–1081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cool SM, Nurcombe V. Substrate induction of osteogenesis from marrow-derived mesenchymal precursors. Stem Cells and Development 2005;14(6):632–642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lee J, Abdeen AA, Huang TH, Kilian KA. Controlling cell geometry on substrates of variable stiffness can tune the degree of osteogenesis in human mesenchymal stem cells. Journal of the Mechanical Behavior of Biomedical Materials 2014;38:209–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Crowder SW, Leonardo V, Whittaker T, Papathanasiou P, Stevens MM. Material Cues as Potent Regulators of Epigenetics and Stem Cell Function. Cell Stem Cell 2016;18(1):39–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Murphy WL, McDevitt TC, Engler AJ. Materials as stem cell regulators. Nature Materials 2014;13(6):547–557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hogrebe NJ, Gooch KJ. Direct influence of culture dimensionality on human mesenchymal stem cell differentiation at various matrix stiffnesses using a fibrous self-assembling peptide hydrogel. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research Part A 2016;104(9):2356–2368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Caliari SR, Vega SL, Kwon M, Soulas EM, Burdick JA. Dimensionality and spreading influence MSC YAP/TAZ signaling in hydrogel environments. Biomaterials 2016;103:314–323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yosef A, Kossover O, Mironi-Harpaz I, Mauretti A, Melino S, Mizrahi J, Seliktar D. Fibrinogen-Based Hydrogel Modulus and Ligand Density Effects on Cell Morphogenesis in Two-Dimensional and Three-Dimensional Cell Cultures. Advanced Healthcare Materials 2019;8(13). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Haugh MG, Heilshorn SC. Integrating concepts of material mechanics, ligand chemistry, dimensionality and degradation to control differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells. Current Opinion in Solid State & Materials Science 2016;20(4):171–179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Burdick JA, Vunjak-Novakovic G. Engineered Microenvironments for Controlled Stem Cell Differentiation. Tissue Engineering Part A 2009;15(2):205–219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ehrbar M, Sala A, Lienemann P, Ranga A, Mosiewicz K, Bittermann A, Rizzi SC, Weber FE, Lutolf MP. Elucidating the Role of Matrix Stiffness in 3D Cell Migration and Remodeling. Biophysical Journal 2011;100(2):284–293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ren Y, Zhang H, Wang YP, Du B, Yang J, Liu LR, Zhang QQ. Hyaluronic Acid Hydrogel with Adjustable Stiffness for Mesenchymal Stem Cell 3D Culture via Related Molecular Mechanisms to Maintain Stemness and Induce Cartilage Differentiation. Acs Applied Bio Materials 2021;4(3):2601–2613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sun AX, Lin H, Fritch MR, Shen H, Alexander PG, DeHart M, Tuan RS. Chondrogenesis of human bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells in 3-dimensional, photocrosslinked hydrogel constructs: Effect of cell seeding density and material stiffness. Acta Biomaterialia 2017;58:302–311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wang T, Lai JH, Yang F. Effects of Hydrogel Stiffness and Biochemical Compositions on Stem Cell-Chondrocyte Interactions in vivo. Tissue Engineering Part A 2015;21:S75–S75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zigon-Branc S, Markovic M, Van Hoorick J, Van Vlierberghe S, Dubruel P, Zerobin E, Baudis S, Ovsianikov A. Impact of Hydrogel Stiffness on Differentiation of Human Adipose-Derived Stem Cell Microspheroids. Tissue Engineering Part A 2019;25(19–20):1369–1380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gonen-Wadmany M, Goldshmid R, Seliktar D. Biological and mechanical implications of PEGylating proteins into hydrogel biomaterials. Biomaterials 2011;32(26):6025–6033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schmidt O, Mizrahi J, Elisseeff J, Seliktar D. Immobilized fibrinogen in PEG hydrogels does not improve chondrocyte-mediated matrix deposition in response to mechanical stimulation. Biotechnology and Bioengineering 2006;95(6):1061–1069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Almany L, Seliktar D. Biosynthetic hydrogel scaffolds made from fibrinogen and polyethylene glycol for 3D cell cultures. Biomaterials 2005;26(15):2467–2477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dikovsky D, Bianco-Peled H, Seliktar D. Proteolytically Degradable Photo-Polymerized Hydrogels Made From PEG-Fibrinogen Adducts. Advanced Engineering Materials 2010;12(6):B200–B209. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rufaihah AJ, Johari NA, Vaibavi SR, Plotkin M, Thien DTD, Kofidis T, Seliktar D. Dual delivery of VEGF and ANG-1 in ischemic hearts using an injectable hydrogel. Acta Biomaterialia 2017;48:58–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Goldshmid R, Mironi-Harpaz I, Shachaf Y, Seliktar D. A method for preparation of hydrogel microcapsules for stem cell bioproces sing and stem cell therapy. Methods 2015;84:35–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Goldshmid R, Seliktar D. Hydrogel Modulus Affects Proliferation Rate and Pluripotency of Human Mesenchymal Stem Cells Grown in Three-Dimensional Culture. Acs Biomaterials Science & Engineering 2017;3(12):3433–3446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Morrison SJ, Scadden DT. The bone marrow niche for haematopoietic stem cells. Nature 2014;505(7483):327–334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Madl CM, Flaig IA, Holbrook CA, Wang YX, Blau HM. Biophysical matrix cues from the regenerating niche direct muscle stem cell fate in engineered microenvironments. Biomaterials 2021;275:120973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rufaihah AJ, Seliktar D. Hydrogels for therapeutic cardiovascular angiogenesis. Advanced Drug Delivery Reviews 2016;96:31–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Madl CM, Heilshorn SC. Engineering Hydrogel Microenvironments to Recapitulate the Stem Cell Niche. Annual Review of Biomedical Engineering, Vol 20 2018;20:21–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Egorikhina MN, Rubtsova YP, Charykova IN, Bugrova ML, Bronnikova II, Mukhina PA, Sosnina LN, Aleynik DY. Biopolymer Hydrogel Scaffold as an Artificial Cell Niche for Mesenchymal Stem Cells. Polymers 2020;12(11). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Rufaihah AJ, Cheyyatraivendran S, Mazlan MDM, Lim K, Chong MSK, Mattar CNZ, Chan JKY, Kofidis T, Seliktar D. The Effect of Scaffold Modulus on the Morphology and Remodeling of Fetal Mesenchymal Stem Cells. Front Physiol 2018;9:1555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lu QQ, Pandya M, Rufaihah AJ, Rosa V, Tong HJ, Seliktar D, Toh WS. Modulation of Dental Pulp Stem Cell Odontogenesis in a Tunable PEG-Fibrinogen Hydrogel System. Stem Cells International 2015;2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Rufaihah AJ, Cheyyatraivendran S, Mazlan MDM, Lim K, Chong MSK, Mattar CNZ, Chan JKY, Kofidis T, Seliktar D. The Effect of Scaffold Modulus on the Morphology and Remodeling of Fetal Mesenchymal Stem Cells. Frontiers in Physiology 2018;9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ferreira SA, Faull PA, Seymour AJ, Yu TTL, Loaiza S, Auner HW, Snijders AP, Gentleman E. Neighboring cells override 3D hydrogel matrix cues to drive human MSC quiescence. Biomaterials 2018;176:13–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ho SS, Murphy KC, Binder BYK, Vissers CB, Leach JK. Increased Survival and Function of Mesenchymal Stem Cell Spheroids Entrapped in Instructive Alginate Hydrogels. Stem Cells Translational Medicine 2016;5(6):773–781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Qazi TH, Mooney DJ, Duda GN, Geissler S. Biomaterials that promote cell-cell interactions enhance the paracrine function of MSCs. Biomaterials 2017;140:103–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Derfoul A, Perkins GL, Hall DJ, Tuan RS. Glucocorticoids promote chondrogenic differentiation of adult human mesenchymal stem cells by enhancing expression of cartilage extracellular matrix genes. Stem Cells 2006;24(6):1487–1495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Campbell DD, Pei M. Surface markers for chondrogenic determination: a highlight of synovium-derived stem cells. Cells 2012;1(4):1107–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Yin H, Price F, Rudnicki MA. Satellite Cells and the Muscle Stem Cell Niche. Physiological Reviews 2013;93(1):23–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Mezey E, Key S, Vogelsang G, Szalayova I, Lange GD, Crain B. Transplanted bone marrow generates new neurons in human brains. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 2003;100(3):1364–1369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Jooybar E, Abdekhodaie MJ, Alvi M, Mousavi A, Karperien M, Dijkstra PJ. An injectable platelet lysate-hyaluronic acid hydrogel supports cellular activities and induces chondrogenesis of encapsulated mesenchymal stem cells. Acta Biomater 2019;83:233–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Hong KH, Kim YM, Song SC. Fine-Tunable and Injectable 3D Hydrogel for On-Demand Stem Cell Niche. Advanced Science 2019;6(17). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Xu YY, Li ZQ, Li XF, Fan ZB, Liu ZG, Xie XY, Guan JJ. Regulating myogenic differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells using thermosensitive hydrogels. Acta Biomaterialia 2015;26:23–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Zhang SQ, Wu MF, Peng CG, Zhao GJ, Gu R. GFAP expression in injured astrocytes in rats. Experimental and Therapeutic Medicine 2017;14(3):1905–1908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Madl CM, LeSavage BL, Dewi RE, Dinh CB, Stowers RS, Khariton M, Lampe KJ, Nguyen D, Chaudhuri O, Enejder A and others. Maintenance of neural progenitor cell stemness in 3D hydrogels requires matrix remodelling. Nature Materials 2017;16(12):1233–+. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Madl CM, LeSavage BL, Dewi RE, Lampe KJ, Heilshorn SC. Matrix Remodeling Enhances the Differentiation Capacity of Neural Progenitor Cells in 3D Hydrogels. Advanced Science 2019;6(4). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Khetan S, Guvendiren M, Legant WR, Cohen DM, Chen CS, Burdick JA. Degradation-mediated cellular traction directs stem cell fate in covalently crosslinked three-dimensional hydrogels. Nature Materials 2013;12(5):458–465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Huebsch N, Arany PR, Mao AS, Shvartsman D, Ali OA, Bencherif SA, Rivera-Feliciano J, Mooney DJ. Harnessing traction-mediated manipulation of the cell/matrix interface to control stem-cell fate. Nature Materials 2010;9(6):518–526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Yang B, Wei K, Loebel C, Zhang K, Feng Q, Li R, Wong SHD, Xu X, Lau C, Chen X and others. Enhanced mechanosensing of cells in synthetic 3D matrix with controlled biophysical dynamics. Nat Commun 2021;12(1):3514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.