Abstract

Cardiovascular (CV) disease is the leading cause of death in women, and it may manifest differently than in men, in part related to sex-specific CV risk factors. In females, assisted reproductive technologies (ARTs) are commonly used to treat infertility, and they utilize controlled ovarian stimulation involving the administration of exogenous sex hormones. ARTs, and especially controlled ovarian stimulation, have been associated with an increased pregnancy and short-term CV risk, although the long-term CV implications of these treatments in individuals treated with ARTs and their offspring remain unclear. This review endeavors to provide a comprehensive examination of what is known about the relationship between ART and CV outcomes for females treated with ARTs, as well as their offspring, and recommendations for future research. Novel insights into female-specific CV risk factors are critical to reduce the disproportionate burden of CV disease in Canadian women. ART has revolutionized reproductive medicine, offering hope to millions of individuals with infertility worldwide, and a further understanding of the CV implications of this important sex-specific CV risk factor is warranted urgently.

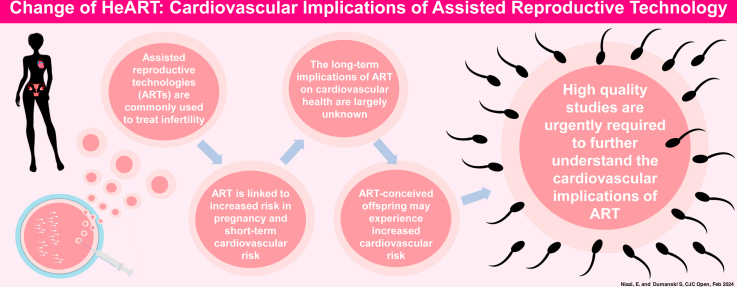

Graphical abstract

Résumé

Les maladies cardiovasculaires représentent la principale cause de décès chez les femmes, chez qui elles peuvent se manifester différemment, en partie en raison des facteurs de risque cardiovasculaire spécifiques au sexe. Chez les femmes, des technologies de procréation assistée (TPA) sont couramment utilisées pour traiter l’infertilité et font appel à la stimulation ovarienne contrôlée qui comporte l’administration d’hormones sexuelles exogènes. Les TPA, et particulièrement la stimulation ovarienne contrôlée, ont été associées à une hausse du risque cardiovasculaire pendant la grossesse et à court terme, alors que les implications cardiovasculaires à long terme de ces traitements chez les patientes traitées et leurs enfants demeurent nébuleuses. Cette analyse vise à brosser un portrait complet des connaissances acquises sur le lien entre les TPA et les issues cardiovasculaires chez les femmes qui y ont recours, ainsi que chez leurs enfants, et de formuler des recommandations pour de futures recherches. Il est essentiel d’avoir de nouveaux éclairages sur les facteurs de risque cardiovasculaire spécifiques aux femmes pour réduire le fardeau disproportionné des maladies cardiovasculaires chez les Canadiennes. Les TPA ont révolutionné la médecine de la reproduction, offrant de l’espoir à des millions de personnes touchées par l’infertilité dans le monde; il est toutefois urgent de mieux connaître les implications cardiovasculaires de ces importants facteurs de risque cardiovasculaire spécifiques au sexe.

Lay Summary

Cardiovascular disease is the leading cause of death in women, which may be in part related to female-specific cardiovascular risk factors. Assisted reproductive technologies (ARTs), including in vitro fertilization, are commonly used to treat infertility in female s. ARTs have been linked to increased short-term cardiovascular risk to female s and their children, but the long-term cardiovascular effects of ARTs remain unclear. High-quality studies are urgently required to increase our understanding of the cardiovascular implications of ARTs.

Cardiovascular (CV) disease (CVD) is the leading cause of death in women worldwide,1 and emerging evidence demonstrates the presence of extensive sex- and gender-related differences in CV risk factors, presentation, pathophysiology, progression, and prognosis.2 Although historically CVD was considered a disease of older women in Canada,3 young women exhibit an increasingly disadvantageous CV risk profile.3 Further, despite declining trends in CV-related hospitalization and CV mortality overall, young women represent the only demographic with stable-to-increasing rates of both measures.4, 5, 6, 7, 8 This significant burden of CVD in young women may be related, in part, to female sex-related CV risk factors specific to the premenopausal lifespan.9

A variety of female-specific reproductive factors, including age of menarche, menstruation, hormonal contraception, fertility, pregnancy, parity, early menopause, and menopausal hormone therapy have been identified as important areas for CV risk assessment in young females.9 Abnormalities in these important domains have been associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular disease (CVD).9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20 Additionally, many of these abnormalities are associated with changes in sex hormones, which are increasingly recognized as being direct mediators of CV function,21 and as such, are being examined more closely in the context of CV health.22, 23, 24, 25

Infertility is an important reproductive factor in young women and is currently estimated to affect nearly 1 in 6 Canadians.26 In concordance with the accelerating prevalence of infertility, Canada also has experienced rapid expansion of the use of fertility treatment, including assisted reproductive technology (ART).27 The most commonly utilized type of ART is in vitro fertilization (IVF),28 and at present, approximately 2% of all live births in Canada are a result of IVF treatment.27,29 ART, including IVF, utilizes controlled ovarian stimulation (COS) to produce multiple oocytes that are retrieved from the ovary and may also be fertilized in vitro and transferred to the uterine cavity as embryos.28,30 To achieve this, COS employs administration of exogenous sex hormones, resulting in manipulation of the ovarian response and the endogenous sex hormone milieu.31

Postulated to be related in part to the effect of sex hormones, both ART and COS have been associated with short-term pregnancy and CV complications, although their long-term implications for CV health remain unclear.32 Additionally, data are conflicting on whether ART-conceived offspring experience increased long-term CV risk.33, 34, 35, 36

Overall, ART has revolutionized reproductive medicine, offering hope to millions of individuals with infertility worldwide.37 However, despite the rapidly increasing use of ART, the CV implications of these treatments are not well understood. This review aims to provide a comprehensive examination of what is known regarding the CV implications of ART for female patients, as well as their offspring, and provides recommendations for future research.

CV Implications of Infertility

Infertility is defined as the inability to establish pregnancy after engaging in 1 year of regular sexual intercourse without contraception,38 and the prevalence of infertility in Canada stands at 16% and is increasing.26,39 However, the burden of infertility likely is underestimated, given that infertility prevalence is examined routinely in only registered married or common-law partners who have an intent to conceive, without consideration of alternative family arrangements or individuals without a pregnancy intent. A more inclusive assessment of infertility would include both biological infertility, defined as the inability to reproduce related to reproductive factors, and social infertility, defined as the inability to reproduce due to one’s relationship status or sexual orientation.40

Growing evidence suggests that infertility, and specifically female-factor infertility, may be independently associated with an increased risk of CVD.41,42 The literature to date, however, remains inconclusive, with some prospective cohort data suggesting that no relationship is present between self-reported infertility and CVD,43 with other prospective data demonstrating a moderate relationship between them,41,44 and additional studies reporting a relationship only between infertility and CV risk factors.45,46 The inconsistencies in this current research landscape may be related, in part, to incongruous definitions and measurements of infertility, variation in study follow-up periods, and insufficient data on specific causes of fertility. Further, although a relationship between infertility and CVD or CV risk factors may exist, the directionality of this association remains unclear. Specifically, whether infertility results in an increased CV risk or whether individuals with CVD or CV risk factors are at increased risk for infertility is not well understood.

With recognition that myriad factors have the potential to contribute to increased CV risk in young females, infertility likely has a considerable effect. Specifically, a number of distinct causes of female-factor infertility have been identified as exhibiting especially high CV risk profiles, including polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS), endometriosis, and reduced ovarian reserve. PCOS is characterized by irregular uterine bleeding, hyperandrogenism, and ultrasonographic evidence of enlarged or cystic ovaries,47 and it is often accompanied by a variety of cardiometabolic risk factors, such as obesity, insulin resistance, and metabolic syndrome.48 Long-term studies suggest that, in addition to posing an increased risk for multiple traditional CV risk factors, such as hypertension and diabetes, PCOS in female patients carries a nearly 1.5 times greater risk for cerebrovascular disease.49 Similarly, individuals living with endometriosis, a disease characterized by presence of endometrial glands and stroma outside of the uterus,50 experience elevated CV risk. Data suggest that a link is present between endometriosis and impaired vascular function51—one that improves following surgical management of endometriosis,52 implying potential causality. Further, a systematic review and meta-analysis that included 6 studies and 254,929 females demonstrated that individuals living with endometriosis had a significantly increased risk of ischemic heart disease and cerebrovascular disease.53 Finally, reduced ovarian reserve, as measured by anti-Müllerian hormone levels, also has been associated with both an increased risk for traditional CV risk factors54, 55, 56, 57 and CVD.22

Overall, amidst the evidence suggesting increased CV risk for females with infertility, careful consideration of the CV implications of fertility treatments is of critical importance to mitigate potential CV risk.

Cardiovascular Implications of ART and COS

ART

ART refers specifically to fertility treatments that employ manipulation of oocytes or embryos, and this includes procedures such as in vitro fertilization and female fertility preservation.28

ART procedures generally utilize COS, which most commonly involves administration of exogenous gonadotropins, including follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH), sometimes with the addition of luteinizing hormone, to stimulate supraphysiologic ovarian follicle growth.58 Simultaneously, gonadotropin-releasing hormone analogs also are typically administered exogenously, to suppress the release of luteinizing hormone and subsequent ovulation, to allow for ongoing growth of follicles.59,60 Gonadotropin and gonadotropin-releasing hormone analog administration continues until the follicles have reached a desired number and size, and then oocyte maturation is induced (usually through administration of human chorionic gonadotropin) prior to surgical retrieval of oocytes.61 Estradiol is produced and secreted by ovarian follicles, and thus, COS also is marked by a substantial increase in endogenous estradiol levels, of up to 20 times baseline levels.62

In ART, COS is followed by oocyte retrieval, in which transvaginal ultrasound-guided aspiration is employed to retrieve mature oocytes from the ovarian follicles.63 Following retrieval, the oocytes may be either cryopreserved (fertility preservation) or fertilized with sperm in vitro (in vitro fertilization [IVF]). If the oocytes are fertilized, the resulting embryos may be transferred immediately to an individual’s uterus to initiate a pregnancy (usually at the cleavage stage [3 days following fertilization] or the blastocyst stage [5 days following fertilization]) or alternatively, cryopreserved for future transfer.60

Multiple sex hormones that are critical to the COS process have been implicated directly in CV health and function. Endogenous estrogen has multiple complex effects on vascular physiology, including vasodilation and a reduction in blood pressure, mainly through activation of nitric oxide synthesis in endothelial cells and interaction with the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS).64, 65, 66 Estrogen signaling also plays an important role in favourable lipid metabolism and dampening of inflammation, thereby providing protection from atherosclerotic CVD.65,66 In fact, the rapid decline of endogenous estrogen is postulated to be a major factor in the increased CV risk exhibited by the population of postmenopausal females.67 In contrast, the role of exogenous estrogen in CV health is not well understood. Oral formulations of exogenous estrogen, including hormonal contraception and hormone replacement therapy, have been associated with increased CV risk, although the effects of non-oral formulations are less clear.15,68 The gonadotropin FSH also is independently associated with CVD in females. Although menopause is well understood to be strongly correlated with increased CV risk, which is most likely due in part to reduced estrogen levels, emerging evidence suggests that increased levels of FSH also may contribute independently to menopause-related CV risk. Higher FSH levels are associated with disadvantageous lipid profiles,69 and independent of estrogen, higher FSH levels have been associated with an increased 10-year risk of atherosclerotic CVD.25 FSH receptors have been found in vascular endothelium, suggesting that they play a direct role in vascular health,70,71 and animal models demonstrate that FSH blockade is effective at reducing atherosclerotic CVD.72

Short-term CV complications of ART

Ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome (OHSS) is a serious complication of COS and is characterized by ovarian enlargement, increased vascular permeability, and fluid shifts from the intravascular space to the third space, resulting in marked hemoconcentration.73, 74, 75 The incidence of moderate-to-severe OHSS is approximately 1%-5% in all ART cycles, although it can be as high as 20% in higher-risk populations, such as those with PCOS.76 With respect to its impact on the vascular system, OHSS results in severe endothelial dysfunction and increased vascular permeability.74 Although the exact physiologic mechanisms have yet to be elucidated, OHSS appears to be mediated in part by vascular endothelial growth factor, expressed by granulosa and theca cells during COS.77, 78, 79, 80 Vascular endothelial growth factor appears to drive severe vascular permeability77,78 and also may contribute to endothelial dysfunction.81 The RAAS also plays an important role in OHSS pathophysiology.75,82 Follicular fluid retrieved from female patients treated with ART complicated by OHSS reveals unusual levels of RAAS components,83 and heightened systemic RAAS activity also has been demonstrated in OHSS,84,85 although whether this effect is an independent mechanism or is simply related to third spacing and intravascular volume depletion is unclear. Interesting to note is that OHSS appears to be an exaggerated pathologic response to COS, and even COS cycles that are uncomplicated by OHSS are affected by a similar, albeit lesser, level of vascular dysfunction.82 COS without OHSS has been associated with some level of vascular permeability, as well as heightened RAAS activity, and this degree of RAAS activation appears to correlate with the number of stimulated follicles.86, 87, 88 This subclinical COS-associated vascular dysfunction may help to provide a mechanistic link to the heightened CV risk of COS and ART.

Likely related to hemoconcentration, inflammation, hypercoagulability, as well as high levels of estrogen inherent to OHSS, arterial and venous thrombosis are common complications of OHSS.89 In fact, females treated with ART complicated by OHSS have an up to 100 times increased risk of thrombosis, compared to pregnant individuals who conceived spontaneously.90 Such thromboembolic events are often severe and may involve the cardiac and cerebrovascular arterial systems, resulting in myocardial infarction and stroke.89,91 Although formal guidelines are lacking, consideration for prophylactic anticoagulation may be prudent in OHSS.32,89

Even in the absence of OHSS, registry data suggest that individuals treated with ART have a heightened risk of venous thromboembolism, which often becomes apparent in the first trimester of pregnancy.92, 93, 94 Specifically, a recent systematic review and meta-analysis of 14 studies reported that individuals treated with ART experienced a 2-3-fold increased risk of venous thromboembolism, compared to individuals who conceived spontaneously (relative risk [RR]: 2.66; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.60-4.43).95 The elevated thromboembolic risk associated with ART is postulated to be related to the high-estrogen state of COS that directly precedes pregnancy in IVF with fresh embryo transfer.96 This possibility is supported further by a recent study that demonstrated an 8-fold increased risk of venous thromboembolism in individuals treated with IVF who underwent a fresh embryo transfer (in which the embryo is transferred to the uterus immediately following COS), compared to the risk in individuals who conceived spontaneously.97 This same risk differential, however, was not demonstrated in individuals treated with IVF who underwent a frozen embryo transfer (in which the embryo is transferred to the uterus following a period of time in which it is cryopreserved).

The thromboembolic risk for individuals treated with unsuccessful ART cycles (cycles that did not result in pregnancy) remains unclear. Two studies have examined the relative thromboembolic risk of successful vs unsuccessful IVF cycles, with conflicting results.98,99 A prospective cohort study of nearly 1000 women referred to a regional thrombosis unit reported a significantly lower risk of venous thromboembolism in individuals with unsuccessful IVF cycles.98 Conversely, registry data from the Registry of Patients with Venous Thromboembolism (RIETE) suggest that although successful and unsuccessful IVF cycles were equivalent with respect to the incidence of venous thrombosis, individuals with unsuccessful cycles were at significantly increased risk for pulmonary embolism.99

Pregnancy-related complications of ART

Although ART remains a generally safe procedure for pregnancy induction, many studies demonstrate that individuals treated with ART experience an increased risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes compared to individuals who conceived spontaneously.

Hypertensive disorders of pregnancy (HDP) complicate up to 10% of all pregnancies on a global scale,100,101, and the risk of developing HDP, including preeclampsia, is increased in individuals who conceived through ART.102 Multiple systematic reviews and meta-analyses have reported this finding,103, 104, 105, 106 and most recently, a 2021 meta-analysis of 85 studies demonstrated a higher odds of HDP for pregnancies conceived through ART, compared to those spontaneously conceived, including in singleton pregnancies (odds ratio [OR] 1.70; 95% CI 1.60-1.80) and in multiple pregnancies (OR 1.34; 95% CI 1.20-1.50).107 The odds of HDP are reported to be even higher in ART treatments that utilize donor oocytes.106, 107, 108 This HDP risk also may be escalated in individuals treated with multiple IVF cycles, those who have a higher number of embryos transferred, and those who have a longer duration of ovarian stimulation.90,94,106

An interesting finding is that the risk of HDP also appears to differ between ART-conceived pregnancies with fresh-embryo transfer and those with frozen-embryo transfer.109 Multiple meta-analyses that examined the odds of HDP occurring in ART also have assessed the relative odds in fresh- vs frozen-embryo transfer.106,107,110 Consistently, ART-conceived pregnancies with frozen-embryo transfer have been reported to have increased odds of HDP compared to ART-conceived pregnancies with fresh-embryo transfer. The difference in pregnancy-associated outcomes between fresh- and frozen-embryo transfer has grown to be the subject of ongoing research, wherein the corpus luteum has been the focus.

The corpus luteum is a temporary endocrine structure that forms after ovulation and produces progesterone and other factors to prepare the endometrial lining for embryo implantation and support early pregnancy.83 One corpus luteum is present in pregnancies with spontaneous conception, and often more than one corpus lutea are present in ART-conceived pregnancies with fresh-embryo transfer. The corpus luteum is absent, however, in ART-conceived pregnancies with frozen-embryo transfer or donor oocytes, both of which demonstrate increased odds for HDP, and require exogenous progesterone administration for luteal endometrial support.111 Data suggest that abnormal numbers of corpora lutea, such as in ART-conceived pregnancies, are associated with adverse vascular changes that may lead to adverse pregnancy outcomes, including HDP. Specifically, in ART-conceived pregnancies without a corpus luteum (ie, IVF with frozen-embryo transfer or donor-oocyte ART), the expected decline in arterial stiffness and pulse wave velocity is attenuated in the first trimester, and a reduction in endothelial function also is demonstrated.112,113 Further, increased aortic augmentation also is demonstrated in the third trimester in ART-conceived pregnancies without a corpus luteum.114 Notably, a relative increase in arterial stiffness throughout pregnancy also has been demonstrated in ART-conceived pregnancies with > 3 corpora lutea (ie, IVF with fresh-embryo transfer), compared to spontaneously conceived pregnancies.112,114 These findings suggest that the corpus luteum and the factors it secretes, including relaxin, which is not detectible in pregnancies without a corpus luteum, may be critical contributors to the healthy vascular response to pregnancy.83,115 The absence of relaxin, known to be important for endothelial function and vascular relaxation, may predispose individuals to increased arterial stiffness and HDP.83 Further, in pregnancies with > 3 corpora lutea, increased RAAS activation has been demonstrated, indicating a potential role for the corpus luteum in healthy RAAS function.83,116

In addition to HDP, other maternal pregnancy complications are present at an increased frequency in ART-conceived pregnancies compared to spontaneously conceived pregnancies. Specifically, ART-conceived pregnancies have a higher incidence of spontaneous abortion,35,117,118 and maternal complications including gestational diabetes and abnormal placentation, known risk factors for future CVD,100,119,120 occur at an increased frequency.103

Long-term CV complications of ART

The long-term CV effects of ART remain unclear, and the available literature on this topic is limited. A large population-based cohort study of more than 240,000 Swedish women with a mean follow-up of 8.6 years reported a higher incidence of hypertension among individuals with pregnancies resultant from IVF, compared to those spontaneously conceived (HR: 1.27, 95% CI: 1.13-1.41), as well as a trend toward an increased incidence of stroke (HR: 1.27, 95% CI: 0.96-1.68).121 Conversely, a large cohort of > 115,000 individuals in the Nurses Health Study reported no relationship between ART and hypertension later in life.88 Further, a Canadian cohort study of over 1 million women demonstrated that in an adjusted analysis, women with pregnancies resultant from fertility therapy (ART and other types) had a lower HR of CV events compared to women with pregnancies related to spontaneous conception, and concluded that fertility therapy was not associated with an increased risk of CVD later in life.122

Another interesting finding is that unsuccessful ART (ie, ART that did not result in a live birth) may predispose individuals to an increased CV risk, compared to successful ART. A population-based cohort analysis of more than 25,000 Canadian women treated with ART and followed for a median of 8.4 years, described a 21% relative increase in the annual CV event rate in women with unsuccessful ART, compared to the rate in women with successful ART.123 This increased risk was driven primarily by heart failure (adjusted relative rate ratio 2.25; 95% CI 2.06-2.46) and stroke (adjusted relative rate ratio 1.25; 95% CI 1.15-1.37).

Overall, the data remain inconclusive, and one meta-analysis has been completed to examine the risk of CVD in female patients treated with fertility therapy (ART and other types).124 This meta-analysis reported no increased risk of a cardiac event (pooled HR: 0.91; 95% CI: 0.67-1.25) in women treated with fertility therapy; however, a trend toward a higher risk of stroke occurred (pooled HR: 1.25; 95% CI: 0.96-1.63).124 All of the studies to date are limited by varying definitions of fertility therapy and ART, heterogeneity of comparator groups, variation in outcomes, and shorter follow-up periods.

To complicate the picture further, females with infertility who seek treatment with ART may possess an inherently higher CV risk profile, which may contribute to the potential for increased CV risk observed following ART. Specifically, females with infertility, who are more likely treated with ART, may be older, may carry increased weight, and may have preexisting medical conditions,42,125 all of which could contribute to an increased CV risk following ART.

COS treatment and the associated hormone changes plausibly could result in long-term vascular effects in individuals treated with ART. During COS, female vascular function is modified, likely in direct response to changes in the hormonal milieu, though the long-term implications for these changes are not well understood. A meta-analysis of studies examining vascular function in response to COS reported a significantly increased heart rate and decreased blood pressure following COS.126 Further, another study demonstrated significantly increased arterial stiffness during COS, as compared to baseline, independent of carotid artery diameter or blood pressure.127 The effects of COS on endothelial function and integrity remain unclear.128,129 Although changes to vascular function, including arterial stiffness and endothelial function, are predictive of long-term CV risk,130,131 a point that remains unclear is whether the vascular health changes associated with COS are transitory or rather persist long-term. Further studies to address this question are urgently warranted.

CV Implications of ART for Offspring

Although ART clearly is a safe and effective treatment, ART-conceived offspring may have a higher CV risk, compared to that of offspring conceived spontaneously. An important point to note, however, is that the existing literature on the association between ART and CV risk in offspring remains very limited and conflicting, making it difficult to formulate strong conclusions.

CV risk factors and disease

A large European cohort study of over 7 million children followed for nearly a decade after birth reported no significant difference in CVD or type 2 diabetes mellitus between ART-conceived offspring and those conceived spontaneously.132 However, ART-conceived offspring did have a significantly elevated risk for obesity. This finding was replicated in a prospective cohort study of 764 children aged 6-10 years, in which the ART-conceived group displayed an increased body mass index compared to that in the spontaneously conceived group.133 Additionally, participants in the ART-conceived group demonstrated disadvantageous differences in left ventricular structure and function, including left ventricular hypertrophy. Similarly, other studies also have reported unfavourable changes to cardiac function in ART-conceived offspring.134,135 Increased blood pressure and hypertension have been inconsistently described in the literature comparing ART-conceived offspring to spontaneously conceived offspring,133,136 and a systematic review and meta-analysis of 19 studies concluded that ART-conceived offspring had a very small but statistically significant elevation in blood pressure, compared to that in offspring conceived spontaneously.34 Finally, a systematic review and meta-analysis of 41 studies reported significantly elevated odds of congenital heart defects among ART-conceived offspring, as compared to the odds among those conceived spontaneously.137

Adverse changes to vascular function also have been observed among ART-conceived offspring. In a cross-sectional study of 122 offspring in childhood, increased arterial stiffness and impaired endothelial function were observed in ART-conceived offspring compared to offspring spontaneously conceived.138 In a follow-up study 5 years later, the vascular dysfunction observed at the initial assessment persisted, with the ART-conceived offspring exhibiting a persistent 25% lower flow-mediated dilation of the brachial artery, increased pulse-wave velocity, and increased carotid intima-media thickness.136

Perinatal CV risk factors

Low birth weight is an independent risk factor for future CVD.139 A number of systematic reviews and large cohort studies have addressed whether birth weight differs among offspring who were conceived spontaneously vs ART-conceived offspring.140, 141, 142, 143, 144, 145, 146 Offspring conceived through ART tend to have lower birth weights than offspring conceived spontaneously, which may contribute to an increased future CV risk. This trend is persistent in both singleton and multiple pregnancies.35 An intriguing finding is that this relationship between IVF-conceived pregnancies and low birth weight appears to be exclusive to fresh-embryo transfers, and no increased odds for low birth weight is demonstrated in IVF-conceived pregnancies with frozen-embryo transfer, according to a recent meta-analysis.147

Conclusions and Future Directions

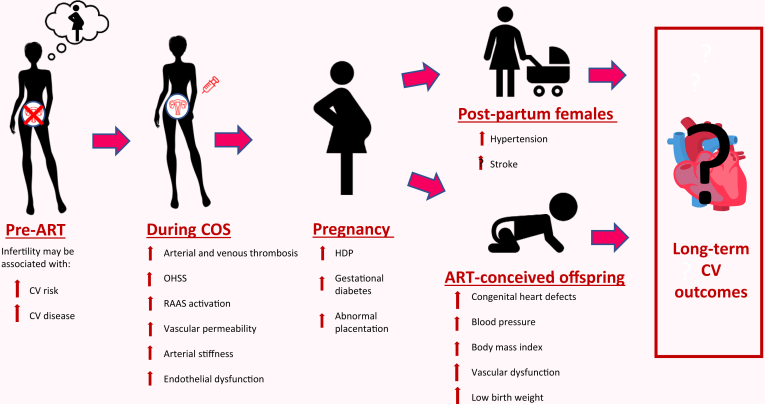

Infertility affects 16% of Canadians, and the use of ART is rising rapidly.26,27,39 Nearly 30,000 ART treatments are completed in Canada each year, and approximately 2% of all live births in Canada are resultant from ART.27,29,148 Despite the rapidly increasing prevalence of ART use, the CV implications of ART remain poorly understood. ART is associated with adverse CV outcomes along several points of the ART timeline (Fig. 1), and this relationship is likely mediated by sex hormone changes, inflammatory changes, and changes to vascular health. Further, although it is clear that ART impacts short-term CV and pregnancy risk, whether ART is associated with adverse CV effects over the long-term remains unclear. Additionally, a full understanding of the CV health implications for ART-conceived offspring is lacking.

Figure 1.

Cardiovascular (CV) outcomes throughout the assisted reproductive technology (ART) timeline. COS, controlled ovarian stimulation; HDP, hypertensive disorders of pregnancy; OHSS, ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome; RAAS, renin-aldosterone angiotensin system.

Large-scale, well-designed prospective cohort studies are urgently needed to further evaluate the long-term CV implications of ART on both the individuals treated with ART and their offspring, as well as the contribution of differing ART protocols and ART success. Further, studies to identify the mechanistic pathways that link ART to CV and vascular outcomes are critically important to identify biomarkers that may predict ART-associated CV complications, and to test appropriate and personalized preventive strategies, including antthrombotic strategies, to limit each individual’s risk. Overall, although much important work has been completed to elucidate the relationship between ART and CV health, prioritization of further work is necessary in order to optimize CV risk reduction in females seeking ART care, as well as their offspring.

Overall, ART has provided hope to millions of individuals with infertility worldwide. However, the relationship between ART, COS, and CV health is complex and multifaceted, necessitating further investigation to optimize the CV well-being of both females undergoing ART and their offspring. This future research holds the key to formulating evidence-based guidelines to mitigate potential CV risks for individuals treated with ART, and to providing critical knowledge and empowerment for the Canadian public.

Acknowledgments

Ethics Statement

The research reported has adhered to ethical guidelines.

Patient Consent

The authors confirm that patient consent is not applicable to this article. This is a narrative review; therefore, patient information was not utilized.

Funding Sources

The authors have no funding sources to declare.

Disclosures

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Footnotes

See page 148 for disclosure information.

References

- 1.Naghavi M., Abajobir A.A., Abbafati C., et al. Global, regional, and national age-sex specific mortality for 264 causes of death, 1980–2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet. 2017;390:1151–1210. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32152-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Norris C.M., Yip C.Y.Y., Nerenberg K.A., et al. State of the science in women’s cardiovascular disease: a Canadian perspective on the influence of sex and gender. J Am Heart Assoc. 2020;9 doi: 10.1161/JAHA.119.015634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Andersson C., Vasan R.S. Epidemiology of cardiovascular disease in young individuals. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2018;15:230–240. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2017.154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arora S., Stouffer G.A., Kucharska-Newton A.M., et al. Twenty-year trends and sex differences in young adults hospitalized with acute myocardial infarction: the ARIC Community Surveillance Study. Circulation. 2019;139:1047–1056. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.118.037137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Champney K.P., Frederick P.D., Bueno H., et al. The joint contribution of sex, age and type of myocardial infarction on hospital mortality following acute myocardial infarction. Heart. 2009;95:895–899. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2008.155804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Izadnegahdar M., Singer J., Lee M.K., et al. Do younger women fare worse? Sex differences in acute myocardial infarction hospitalization and early mortality rates over ten years. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2014;23:10–17. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2013.4507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tu J.V., Khan A.M., Ng K., Chu A. Recent temporal changes in atherosclerotic cardiovascular diseases in Ontario: clinical and health systems impact. Can J Cardiol. 2017;33:378–384. doi: 10.1016/j.cjca.2016.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wilmot K.A., O’Flaherty M., Capewell S., Ford E.S., Vaccarino V. Coronary heart disease mortality declines in the United States from 1979 through 2011: evidence for stagnation in young adults, especially women. Circulation. 2015;132:997–1002. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.015293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mulvagh S.L., Mullen K.A., Nerenberg K.A., et al. The Canadian Women’s Heart Health Alliance atlas on the epidemiology, diagnosis, and management of cardiovascular disease in women—Chapter 4: sex- and gender-unique disparities: CVD across the lifespan of a woman. CJC Open. 2022;4:115–132. doi: 10.1016/j.cjco.2021.09.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Huang C., Lin B., Yuan Y., et al. Associations of menstrual cycle regularity and length with cardiovascular diseases: a prospective study from UK Biobank. J Am Heart Assoc. 2023;12 doi: 10.1161/JAHA.122.029020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Luijken J., Van Der Schouw Y.T., Mensink D., Onland-Moret N.C. Association between age at menarche and cardiovascular disease: a systematic review on risk and potential mechanisms. Maturitas. 2017;104:96–116. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2017.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grandi S.M., Filion K.B., Yoon S., et al. Cardiovascular disease-related morbidity and mortality in women with a history of pregnancy complications: systematic review and meta-analysis. Circulation. 2019;139:1069–1079. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.118.036748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Barrett-Connor E. Menopause, atherosclerosis, and coronary artery disease. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2013;13:186–191. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2013.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kaminski P., Szpotanska-Sikorska M., Wielgos M. Cardiovascular risk and the use of oral contraceptives. Neuro Endocrinol Lett. 2013;34:587–589. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kalenga C.Z., Dumanski S.M., Metcalfe A., et al. The effect of non-oral hormonal contraceptives on hypertension and blood pressure: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Physiol Rep. 2022;10 doi: 10.14814/phy2.15267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gulamhusein N., Dumanski S.M., Ahmed S.B. Paring it down: parity, sex hormones, and cardiovascular risk. Can J Cardiol. 2022;38:1901–1903. doi: 10.1016/j.cjca.2022.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shufelt C.L., Manson J.E. Menopausal hormone therapy and cardiovascular disease: the role of formulation, dose, and route of delivery. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2021;106:1245–1254. doi: 10.1210/clinem/dgab042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Canoy D., Beral V., Balkwill A., et al. Age at menarche and risks of coronary heart and other vascular diseases in a large UK cohort. Circulation. 2015;131:237–244. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.010070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wellons M., Ouyang P., Schreiner P.J., Herrington D.M., Vaidya D. Early menopause predicts future coronary heart disease and stroke: the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. Menopause. 2012;19:1081–1087. doi: 10.1097/gme.0b013e3182517bd0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lawlor D.A., Emberson J.R., Ebrahim S., et al. Is the association between parity and coronary heart disease due to biological effects of pregnancy or adverse lifestyle risk factors associated with child-rearing? Findings from the British Women’s Heart and Health Study and the British Regional Heart Study. Circulation. 2003;107:1260–1264. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000053441.43495.1a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Willemars M.M.A., Nabben M., Verdonschot J.A.J., Hoes M.F. Evaluation of the interaction of sex hormones and cardiovascular function and health. Curr Heart Fail Rep. 2022;19:200–212. doi: 10.1007/s11897-022-00555-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.de Kat A.C., Verschuren W.M., Eijkemans M.J.C., Broekmans F.J.M., van der Schouw Y.T. Anti-Müllerian hormone trajectories are associated with cardiovascular disease in women: results from the Doetinchem Cohort Study. Circulation. 2017;135:556–565. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.116.025968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ueda K., Fukuma N., Adachi Y., et al. Sex differences and regulatory actions of estrogen in cardiovascular system. Front Physiol. 2021;12 doi: 10.3389/fphys.2021.738218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hermsmeyer R.K., Thompson T.L., Pohost G.M., Kaski J.C. Cardiovascular effects of medroxyprogesterone acetate and progesterone: a case of mistaken identity? Nat Rev Cardiol. 2008;5:387–395. doi: 10.1038/ncpcardio1234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang N., Shao H., Chen Y., et al. Follicle-stimulating hormone, its association with cardiometabolic risk factors, and 10-year risk of cardiovascular disease in postmenopausal women. J Am Heart Assoc. 2017;6 doi: 10.1161/JAHA.117.005918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bushnik T., Cook J.L., Yuzpe A.A., Tough S., Collins J. Estimating the prevalence of infertility in Canada. Hum Reprod. 2012;27:738–746. doi: 10.1093/humrep/der465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ontario Better Outcomes Registry & Network (BORN) Canadian Assisted Reproductive Technologies Register (CARTR) Plus. https://cfas.ca/_Library/CARTR/CFAS_CARTR_Plus_Report.pdf Available at:

- 28.Jain M., Singh M. Assisted reproductive technology (ART) techniques. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK576409/ [PubMed]

- 29.Statistics Canada. Births. 2017. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/daily-quotidien/180928/dq180928c-eng.htm Available at:

- 30.DeCherney A.H. In vitro fertilization and embryo transfer: a brief overview. Yale J Biol Med. 1986;59:409–414. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gallos I.D., Eapen A., Price M.J., et al. Controlled ovarian stimulation protocols for assisted reproduction: a network meta-analysis. https://www.cochranelibrary.com/cdsr/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD012586/full Available at:

- 32.Smith J., Velez M.P., Dayan N. Infertility, infertility treatment, and cardiovascular disease: an overview. Can J Cardiol. 2021;37:1959–1968. doi: 10.1016/j.cjca.2021.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Beilby K.H., Kneebone E., Roseboom T.J., et al. Offspring physiology following the use of IVM, IVF and ICSI: a systematic review and meta-analysis of animal studies. Hum Reprod Update. 2023;29:272–290. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmac043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Guo X.-Y., Liu X.-M., Jin L., et al. Cardiovascular and metabolic profiles of offspring conceived by assisted reproductive technologies: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Fertil Steril. 2017;107:622–631.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2016.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Talaulikar V.S., Arulkumaran S. Maternal, perinatal and long-term outcomes after assisted reproductive techniques (ART): implications for clinical practice. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2013;170:13–19. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2013.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.von Wolff M., Haaf T. In vitro fertilization technology and child health. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2020;117:23–30. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2020.0023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Crockin S.L., Altman A.B., Edmonds M.A. The history and future trends of ART medicine and law. Family Court Rev. 2021;59:22–45. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vander Borght M., Wyns C. Fertility and infertility: definition and epidemiology. Clin Biochem. 2018;62:2–10. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2018.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Statistics Canada Births 2019. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/daily-quotidien/200929/dq200929e-eng.htm#:∼:text = Canada%27s%20total%20fertility%20rate%20hits,woman%20from%203.94%20in%201959 Available at:

- 40.Lo W., Campo-Engelstein L. In: Reproductive Ethics II. Campo-Engelstein L., Burcher P., editors. Springer International; 2018. Expanding the clinical definition of infertility to include socially infertile individuals and couples; pp. 71–83.https://link.springer.com/book/10.1007/978-3-319-89429-4 Available at: [Google Scholar]

- 41.Skåra K.H., Åsvold B.O., Hernáez Á., et al. Risk of cardiovascular disease in women and men with subfertility: the Trøndelag Health Study. Fertil Steril. 2022;118:537–547. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2022.05.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Senapati S. Infertility: a marker of future health risk in women? Fertil Steril. 2018;110:783–789. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2018.08.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cairncross Z.F., Ahmed S.B., Dumanski S.M., Nerenberg K.A., Metcalfe A. Infertility and the risk of cardiovascular disease: findings from the Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation (SWAN) CJC Open. 2021;3:400–408. doi: 10.1016/j.cjco.2020.11.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Farland L.V., Wang Y., Gaskins A.J., et al. Infertility and risk of cardiovascular disease: a prospective cohort study. J Am Heart Assoc. 2023;12 doi: 10.1161/JAHA.122.027755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mahalingaiah S., Sun F., Cheng J.J., Chow E.T., Lunetta K.L. Cardiovascular risk factors among women with self-reported infertility. Fertil Res Pract. 2017;3:7. doi: 10.1186/s40738-017-0034-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Verit F.F., Yildiz Zeyrek F., Zebitay A.G., Akyol H. Cardiovascular risk may be increased in women with unexplained infertility. Clin Exp Reprod Med. 2017;44:28. doi: 10.5653/cerm.2017.44.1.28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sirmans S.M., Pate K.A. Epidemiology, diagnosis, and management of polycystic ovary syndrome. Clin Epiemiol. 2013;6:1–13. doi: 10.2147/CLEP.S37559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Osibogun O., Ogunmoroti O., Michos E.D. Polycystic ovary syndrome and cardiometabolic risk: opportunities for cardiovascular disease prevention. Trends Cardiovasc Med. 2020;30:399–404. doi: 10.1016/j.tcm.2019.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wekker V., van Dammen L., Koning A., et al. Long-term cardiometabolic disease risk in women with PCOS: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Hum Reprod Update. 2020;26:942–960. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmaa029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tsamantioti E.S., Mahdy H. Endometriosis. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK567777/ Available at: [PubMed]

- 51.Santoro L., D’Onofrio F., Campo S., et al. Endothelial dysfunction but not increased carotid intima-media thickness in young European women with endometriosis. Hum Reprod. 2012;27:1320–1326. doi: 10.1093/humrep/des062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Santoro L., D’Onofrio F., Campo S., et al. Regression of endothelial dysfunction in patients with endometriosis after surgical treatment: a 2-year follow-up study. Hum Reprod. 2014;29:1205–1210. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deu074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Do Couto C.P., Policiano C., Pinto F.J., Brito D., Caldeira D. Endometriosis and cardiovascular disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Maturitas. 2023;171:45–52. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2023.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bleil M.E., Gregorich S.E., McConnell D., Rosen M.P., Cedars M.I. Does accelerated reproductive aging underlie premenopausal risk for cardiovascular disease? Menopause. 2013;20:1139–1146. doi: 10.1097/GME.0b013e31828950fa. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lambrinoudaki I., Stergiotis S., Chatzivasileiou P., et al. Anti-Müllerian hormone concentrations are inversely associated with subclinical atherosclerosis in premenopausal women. Angiology. 2020;71:552–558. doi: 10.1177/0003319720914493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Looby S.E., Fitch K.V., Srinivasa S., et al. Reduced ovarian reserve relates to monocyte activation and subclinical coronary atherosclerotic plaque in women with HIV. AIDS. 2016;30:383–393. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000000902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Dumanski S.M., Anderson T.J., Nerenberg K.A., et al. Anti-Müllerian hormone and vascular dysfunction in women with chronic kidney disease. Physiol Rep. 2022;10 doi: 10.14814/phy2.15154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Howie R., Kay V. Controlled ovarian stimulation for in-vitro fertilization. Br J Hosp Med (Lond) 2018;79:194–199. doi: 10.12968/hmed.2018.79.4.194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Padula A.M. GnRH analogues—agonists and antagonists. Anim Reprod Sci. 2005;88:115–126. doi: 10.1016/j.anireprosci.2005.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Choe J., Shanks A.L. In vitro fertilization. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK562266/ Available at:

- 61.Alyasin A., Mehdinejadiani S. GnRH agonist trigger versus hCG trigger in GnRH antagonist in IVF/ICSI cycles: a review article. Int J Reprod Biomed. 2016;14:557–566. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Prasad S., Kumar Y., Singhal M., Sharma S. Estradiol level on day 2 and day of trigger: a potential predictor of the IVF-ET success. J Obstet Gynaecol India. 2014;64:202–207. doi: 10.1007/s13224-014-0515-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Jančar N., Ban Frangež H. In: Management of Infertility: A Practical Approach. Guglielmino A., Lagana A.S., editors. Elsevier; Philadelphia: 2023. Oocyte retrieval; pp. 205–209. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Iorga A., Cunningham C.M., Moazeni S., et al. The protective role of estrogen and estrogen receptors in cardiovascular disease and the controversial use of estrogen therapy. Biol Sex Differ. 2017;8:33. doi: 10.1186/s13293-017-0152-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Boese A.C., Kim S.C., Yin K.J., Lee J.P., Hamblin M.H. Sex differences in vascular physiology and pathophysiology: estrogen and androgen signaling in health and disease. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2017;313:H524–H545. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00217.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Knowlton A.A., Lee A.R. Estrogen and the cardiovascular system. Pharmacol Ther. 2012;135:54–70. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2012.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Santoro N., Randolph J.F. Reproductive hormones and the menopause transition. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2011;38:455–466. doi: 10.1016/j.ogc.2011.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kalenga C.Z., Metcalfe A., Robert M., et al. Association between the route of administration and formulation of estrogen therapy and hypertension risk in postmenopausal women: a prospective population-based study. Hypertension. 2023;80:1463–1473. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.122.19938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Chu M.C. Elevated basal FSH in normal cycling women is associated with unfavourable lipid levels and increased cardiovascular risk. Hum Reprod. 2003;18:1570–1573. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deg330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Maclellan R.A., Vivero M.P., Purcell P., et al. Expression of follicle-stimulating hormone receptor in vascular anomalies. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2014;133:344e–351e. doi: 10.1097/01.prs.0000438458.60474.fc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Siraj A., Desestret V., Antoine M., et al. Expression of follicle-stimulating hormone receptor by the vascular endothelium in tumor metastases. BMC Cancer. 2013;13:246. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-13-246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Zhu D., Li X., Macrae V.E., Simoncini T., Fu X. Extragonadal effects of follicle-stimulating hormone on osteoporosis and cardiovascular disease in women during menopausal transition. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2018;29:571–580. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2018.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Binder H., Dittrich R., Einhaus F., et al. Update on ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome: part 1—incidence and pathogenesis. Int J Fertil Womens Med. 2007;52:11–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Soares S.R., Gómez R., Simón C., García-Velasco J.A., Pellicer A. Targeting the vascular endothelial growth factor system to prevent ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome. Hum Reprod Update. 2008;14:321–333. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmn008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Ata B., Yakin K., Alatas C., Urman B. Dual renin-angiotensin blockage and total embryo cryopreservation is not a risk-free strategy in patients at high risk for ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome. Fertil Steril. 2008;90:531–536. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2007.07.1309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Palomba S., Caserta D. In: Management of Infertility. Guglielmino A., Lagana A.S., editors. Elsevier; Philadelphia: 2023. Ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome; pp. 223–239. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Levin E.R., Rosen G.F., Cassidenti D.L., et al. Role of vascular endothelial cell growth factor in ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome. J Clin Invest. 1998;102:1978–1985. doi: 10.1172/JCI4814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.McClure N., Healy D.L., Rogers P.A.W., et al. Vascular endothelial growth factor as capillary permeability agent in ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome. Lancet. 1994;344:235–236. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(94)93001-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Abramov Y., Barak V., Nisman B., Schenker J.G. Vascular endothelial growth factor plasma levels correlate to the clinical picture in severe ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome. Fertil Steril. 1997;67:261–265. doi: 10.1016/S0015-0282(97)81908-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Nastri C.O., Ferriani R.A., Rocha I.A., Martins W.P. Ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome: pathophysiology and prevention. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2010;27:121–128. doi: 10.1007/s10815-010-9387-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Tsai W.C., Li Y.H., Huang Y.Y., et al. Plasma vascular endothelial growth factor as a marker for early vascular damage in hypertension. Clin Sci (Lond) 2005;109:39–43. doi: 10.1042/CS20040307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Manau D., Balasch J., Arroyo V., et al. Circulatory dysfunction in asymptomatic in vitro fertilization patients. Relationship with hyperestrogenemia and activity of endogenous vasodilators. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1998;83:1489–1493. doi: 10.1210/jcem.83.5.4796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Conrad K.P., Graham G.M., Chi Y.Y., et al. Potential influence of the corpus luteum on circulating reproductive and volume regulatory hormones, angiogenic and immunoregulatory factors in pregnant women. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2019;317:E677–E685. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00225.2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Palumbo A., Ávila J., Naftolin F. The ovarian renin-angiotensin system (OVRAS): a major factor in ovarian function and disease. Reprod Sci. 2016;23:1644–1655. doi: 10.1177/1933719116672588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Delbaere A., Bergmann P.J.M., Gervy-Decoster C., et al. Increased angiotensin II in ascites during severe ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome: role of early pregnancy and ovarian gonadotropin stimulation. Fertil Steril. 1997;67:1038–1045. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(97)81436-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Itskovitz J., Sealey J.E., Glorioso N., Rosenwaks Z. Plasma prorenin response to human chorionic gonadotropin in ovarian-hyperstimulated women: correlation with the number of ovarian follicles and steroid hormone concentrations. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1987;84:7285–7289. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.20.7285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Sealey J.E., Itskovitz-Eldor J., Rubattu S., et al. Estradiol- and progesterone-related increases in the renin-aldosterone system: studies during ovarian stimulation and early pregnancy. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1994;79:258–264. doi: 10.1210/jcem.79.1.8027239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Farland L.V., Grodstein F., Srouji S.S., et al. Infertility, fertility treatment, and risk of hypertension. Fertil Steril. 2015;104:391–397. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2015.04.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Chan W.S., Dixon M.E. The “ART” of thromboembolism: a review of assisted reproductive technology and thromboembolic complications. Thromb Res. 2008;121:713–726. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2007.05.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Sennström M., Rova K., Hellgren M., et al. Thromboembolism and in vitro fertilization—a systematic review. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2017;96:1045–1052. doi: 10.1111/aogs.13147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Samy M.A., Chowdhury R., Asun S. Ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome and myocardial infarction: a systematic review. Int J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2019;5:009–012. [Google Scholar]

- 92.Henriksson P., Westerlund E., Wallen H., et al. Incidence of pulmonary and venous thromboembolism in pregnancies after in vitro fertilisation: cross sectional study. BMJ. 2013;346 doi: 10.1136/bmj.e8632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Rova K., Passmark H., Lindqvist P.G. Venous thromboembolism in relation to in vitro fertilization: an approach to determining the incidence and increase in risk in successful cycles. Fertil Steril. 2012;97:95–100. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2011.10.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Hansen A.T., Kesmodel U.S., Juul S., Hvas A.M. Increased venous thrombosis incidence in pregnancies after in vitro fertilization. Hum Reprod. 2014;29:611–617. doi: 10.1093/humrep/det458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Goualou M., Noumegni S., de Moreuil C., et al. Venous thromboembolism associated with assisted reproductive technology: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Thromb Haemost. 2023;123:283–294. doi: 10.1055/s-0042-1760255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Henriksson P. Cardiovascular problems associated with IVF therapy. J Intern Med. 2021;289:2–11. doi: 10.1111/joim.13136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Olausson N., Discacciati A., Nyman A.I., et al. Incidence of pulmonary and venous thromboembolism in pregnancies after in vitro fertilization with fresh respectively frozen-thawed embryo transfer: nationwide cohort study. J Thromb Haemost. 2020;18:1965–1973. doi: 10.1111/jth.14840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Villani M., Favuzzi G., Totaro P., et al. Venous thromboembolism in assisted reproductive technologies: comparison between unsuccessful versus successful cycles in an Italian cohort. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2018;45:234–239. doi: 10.1007/s11239-017-1584-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Grandone E., Di Micco P., Villani M., et al. Venous thromboembolism in women undergoing assisted reproductive technologies: data from the RIETE Registry. Thromb Haemost. 2018;118:1962–1968. doi: 10.1055/s-0038-1673402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Bajpai D., Popa C., Verma P., Dumanski S., Shah S. Evaluation and management of hypertensive disorders of pregnancy. Kidney360. 2023;4:1512–1525. doi: 10.34067/KID.0000000000000228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Umesawa M., Kobashi G. Epidemiology of hypertensive disorders in pregnancy: prevalence, risk factors, predictors and prognosis. Hypertens Res. 2017;40:213–220. doi: 10.1038/hr.2016.126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Rossberg N., Stangl K., Stangl V. Pregnancy and cardiovascular risk: a review focused on women with heart disease undergoing fertility treatment. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2016;23:1953–1961. doi: 10.1177/2047487316673143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Qin J., Liu X., Sheng X., Wang H., Gao S. Assisted reproductive technology and the risk of pregnancy-related complications and adverse pregnancy outcomes in singleton pregnancies: a meta-analysis of cohort studies. Fertil Steril. 2016;105:73–85.e1-6. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2015.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Thomopoulos C., Tsioufis C., Michalopoulou H., et al. Assisted reproductive technology and pregnancy-related hypertensive complications: a systematic review. J Hum Hypertens. 2013;27:148–157. doi: 10.1038/jhh.2012.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Almasi-Hashiani A., Omani-Samani R., Mohammadi M., et al. Assisted reproductive technology and the risk of preeclampsia: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2019;19:149. doi: 10.1186/s12884-019-2291-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Luke B., Brown M.B., Eisenberg M.L., et al. In vitro fertilization and risk for hypertensive disorders of pregnancy: associations with treatment parameters. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2020;222 doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2019.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Chih H.J., Elias F.T.S., Gaudet L., Velez M.P. Assisted reproductive technology and hypertensive disorders of pregnancy: systematic review and meta-analyses. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2021;21:449. doi: 10.1186/s12884-021-03938-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Masoudian P., Nasr A., De Nanassy J., et al. Oocyte donation pregnancies and the risk of preeclampsia or gestational hypertension: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;214:328–339. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2015.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Park K., Allard-Phillips E., Christman G., Dimza M., Rhoton-Vlasak A. Assisted reproductive technologies and their association with adverse pregnancy outcomes and long-term cardiovascular disease: implications for counseling patients. Curr Treat Options Cardio Med. 2021;23:54. [Google Scholar]

- 110.Jin X., Liu G., Jiao Z., et al. Pregnancy outcome difference between fresh and frozen embryos in women without polycystic ovary syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Reprod Sci. 2021;28:1267–1276. doi: 10.1007/s43032-020-00323-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Pabuçcu E., Pabuçcu R., Gürgan T., Tavmergen E. Luteal phase support in fresh and frozen embryo transfer cycles. J Gynecol Obstet Hum Reprod. 2020;49 doi: 10.1016/j.jogoh.2020.101838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.von Versen-Höynck F., Schaub A.M., Chi Y.Y., et al. Increased preeclampsia risk and reduced aortic compliance with in vitro fertilization cycles in the absence of a corpus luteum. Hypertension. 2019;73:640–649. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.118.12043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.von Versen-Höynck F., Narasimhan P., Selamet Tierney E.S., et al. Absent or excessive corpus luteum number is associated with altered maternal vascular health in early pregnancy. Hypertension. 2019;73:680–690. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.118.12046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.von Versen-Höynck F., Häckl S., Selamet Tierney E.S., et al. Maternal vascular health in pregnancy and postpartum after assisted reproduction. Hypertension. 2020;75:549–560. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.119.13779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Johnson M.R., Abdalla H., Allman A.C., et al. Relaxin levels in ovum donation pregnancies. Fertil Steril. 1991;56:59–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Wiegel R.E., Jan Danser A.H., Steegers-Theunissen R.P.M., et al. Determinants of maternal renin-angiotensin-aldosterone-system activation in early pregnancy: insights from 2 cohorts. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2020;105:3505–3517. doi: 10.1210/clinem/dgaa582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Grady R., Alavi N., Vale R., Khandwala M., McDonald S.D. Elective single embryo transfer and perinatal outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Fertil Steril. 2012;97:324–331. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2011.11.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Mukhopadhaya N., Arulkumaran S. Reproductive outcomes after in-vitro fertilization. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2007;19:113–119. doi: 10.1097/GCO.0b013e32807fb199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Yu Y., Soohoo M., Sørensen H.T., Li J., Arah O.A. Gestational diabetes mellitus and the risks of overall and type-specific cardiovascular diseases: a population- and sibling-matched cohort study. Diabetes Care. 2022;45:151–159. doi: 10.2337/dc21-1018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Hasija A., Balyan K., Debnath E., Ravi V., Kumar M. Prediction of hypertension in pregnancy in high risk women using maternal factors and serial placental profile in second and third trimester. Placenta. 2021;104:236–242. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2021.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Westerlund E., Brandt L., Hovatta O., et al. Incidence of hypertension, stroke, coronary heart disease, and diabetes in women who have delivered after in vitro fertilization: a population-based cohort study from Sweden. Fertil Steril. 2014;102:1096–1102. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2014.06.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Udell J.A., Lu H., Redelmeier D.A. Long-term cardiovascular risk in women prescribed fertility therapy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;62:1704–1712. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.05.085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Udell J.A., Lu H., Redelmeier D.A. Failure of fertility therapy and subsequent adverse cardiovascular events. CMAJ. 2017;189:E391–E397. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.160744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Dayan N., Filion K.B., Okano M., et al. Cardiovascular risk following fertility therapy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;70:1203–1213. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.07.753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Rich-Edwards J.W., Fraser A., Lawlor D.A., Catov J.M. Pregnancy characteristics and women’s future cardiovascular health: an underused opportunity to improve women’s health? Epidemiol Rev. 2014;36:57–70. doi: 10.1093/epirev/mxt006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Fujitake E., Jaspal R., Monasta L., Stampalija T., Lees C. Acute cardiovascular changes in women undergoing in vitro fertilisation (IVF), a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2020;248:245–251. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2020.01.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Leppänen J., Randell K., Schwab U., et al. The effect of different estradiol levels on carotid artery distensibility during a long agonist IVF protocol. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2020;18:44. doi: 10.1186/s12958-020-00608-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Hulde N., Rogenhofer N., Brettner F., et al. Effects of controlled ovarian stimulation on vascular barrier and endothelial glycocalyx: a pilot study. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2021;38:2273–2282. doi: 10.1007/s10815-021-02233-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Leppänen J., Randell K., Schwab U., et al. Endothelial function and concentrations of high-sensitivity C-reactive protein, interleukin-6, and tumor necrosis factor-alpha during a long agonist IVF protocol. J Reprod Immunol. 2021;148 doi: 10.1016/j.jri.2021.103434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Martin B.J., Anderson T.J. Risk prediction in cardiovascular disease: the prognostic significance of endothelial dysfunction. Can J Cardiol. 2009;25(Suppl A Suppl A):15A–20A. doi: 10.1016/s0828-282x(09)71049-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Vasan R.S., Pan S., Xanthakis V., et al. Arterial stiffness and long-term risk of health outcomes: The Framingham Heart Study. Hypertension. 2022;79:1045–1056. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.121.18776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Norrman E., Petzold M., Gissler M., et al. Cardiovascular disease, obesity, and type 2 diabetes in children born after assisted reproductive technology: a population-based cohort study. PLoS Med. 2021;18 doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1003723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Cui L., Zhao M., Zhang Z., et al. Assessment of cardiovascular health of children ages 6 to 10 years conceived by assisted reproductive technology. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4 doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.32602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Zhou J., Liu H., Gu H.-T., et al. Association of cardiac development with assisted reproductive technology in childhood: a prospective single-blind pilot study. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2014;34:988–1000. doi: 10.1159/000366315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Liu H., Zhang Y., Gu H.-T., et al. Association between assisted reproductive technology and cardiac alteration at age 5 years. JAMA Pediatr. 2015;169:603. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2015.0214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Meister T.A., Rimoldi S.F., Soria R., et al. Association of assisted reproductive technologies with arterial hypertension during adolescence. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;72:1267–1274. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2018.06.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Giorgione V., Parazzini F., Fesslova V., et al. Congenital heart defects in IVF/ICSI pregnancy: systematic review and meta-analysis. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2018;51:33–42. doi: 10.1002/uog.18932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Scherrer U., Rimoldi S.F., Rexhaj E., et al. Systemic and pulmonary vascular dysfunction in children conceived by assisted reproductive technologies. Circulation. 2012;125:1890–1896. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.071183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Smith C.J., Ryckman K.K., Barnabei V.M., et al. The impact of birth weight on cardiovascular disease risk in the Women’s Health Initiative. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2016;26:239–245. doi: 10.1016/j.numecd.2015.10.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Jackson R.A., Gibson K.A., Wu Y.W., Croughan M.S. Perinatal outcomes in singletons following in vitro fertilization: a meta-analysis. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;103:551–563. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000114989.84822.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Helmerhorst F.M., Perquin D.A.M., Donker D., Keirse M.J.N.C. Perinatal outcome of singletons and twins after assisted conception: a systematic review of controlled studies. BMJ. 2004;328:261. doi: 10.1136/bmj.37957.560278.EE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Schieve L.A., Ferre C., Peterson H.B., et al. Perinatal outcome among singleton infants conceived through assisted reproductive technology in the United States. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;103:1144–1153. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000127037.12652.76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.McDonald S.D., Murphy K., Beyene J., Ohlsson A. Perinatel outcomes of singleton pregnancies achieved by in vitro fertilization: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2005;27:449–459. doi: 10.1016/s1701-2163(16)30527-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Boulet S.L., Schieve L.A., Nannini A., et al. Perinatal outcomes of twin births conceived using assisted reproduction technology: a population-based study. Hum Reprod. 2008;23:1941–1948. doi: 10.1093/humrep/den169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.McDonald S.D., Han Z., Mulla S., et al. Preterm birth and low birth weight among in vitro fertilization singletons: a systematic review and meta-analyses. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2009;146:138–148. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2009.05.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.McDonald S.D., Han Z., Mulla S., et al. Preterm birth and low birth weight among in vitro fertilization twins: a systematic review and meta-analyses. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2010;148:105–113. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2009.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Elias F.T.S., Weber-Adrian D., Pudwell J., et al. Neonatal outcomes in singleton pregnancies conceived by fresh or frozen embryo transfer compared to spontaneous conceptions: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2020;302:31–45. doi: 10.1007/s00404-020-05593-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Canadian Fertility and Andrology Society . 2016. Results from the Canadian ART Register Press Release.https://cfas.ca/canadian-art-register.html Available at: [Google Scholar]