Abstract

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is a multi-organ and systemic autoimmune disease characterized by an imbalance of humoral and cellular immunity. The efficacy and side effects of traditional glucocorticoid and immunosuppressant therapy remain controversial. Recent studies have revealed abnormalities in mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) in SLE, leading to the application of bone marrow-derived MSCs (BM-MSCs) transplantation technique for SLE treatment. However, autologous transplantation using BM-MSCs from SLE patients has shown suboptimal efficacy due to their dysfunction, while allogeneic mesenchymal stem cell transplantation (MSCT) still faces challenges, such as donor degeneration, genetic instability, and immune rejection. Therefore, exploring new sources of stem cells is crucial for overcoming these limitations in clinical applications. Human amniotic epithelial stem cells (hAESCs), derived from the eighth-day blastocyst, possess strong characteristics including good differentiation potential, immune tolerance with low antigen-presenting ability, and unique immune properties. Hence, hAESCs hold great promise for the treatment of not only SLE but also other autoimmune diseases.

Keywords: human amniotic epithelial stem cells, transplantation, systemic lupus erythematosus

Introduction

The pathogenesis of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), an autoimmune disease affecting multiple organs and systems, is closely associated with defects in the bone marrow hematopoietic microenvironment. Studies have confirmed that the primary mechanism involves an imbalance between humoral immunity and cellular immunity, wherein hyperactive B lymphocytes generate a plethora of auto-antibodies, immune complexes, and cytokines. Consequently, functional regulatory T lymphocytes fail to sustain self-tolerance, leading to immune-mediated inflammation and tissue damage.

The conventional clinical management of SLE involves the administration of glucocorticoids and immunosuppressants. Despite achieving control over the condition and improving prognosis for most patients, there remains ongoing debate regarding their efficacy and safety profile. Inevitably, adverse reactions, such as infection, osteoporosis, tumor development, and ovarian failure cannot be entirely avoided. Moreover, some patients experience drug intolerance leading to a significant decline in treatment effectiveness, thereby impacting both quality of life and overall survival.

Recent studies have shown that there are unusual characteristics of mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) in people with SLE1–5. MSCs that are derived from the bone marrow of SLE patients display impaired growth, are more vulnerable to cell death and aging, and secrete fewer cytokines. They also suppress the proliferation and differentiation of T and B cells. It has been suggested that the malfunctioning of MSCs may be responsible for SLE 6 . Animal models have confirmed this theory, as lupus mice treated with MSCs have shown a dose-dependent improvement in clinical symptoms and survival rates, especially when the treatment is administered in the early stages of the disease.

Advances in Stem Cell Therapy

Stem cells possess self-renewal ability, multi-directional differentiation potential, and multiple immune regulatory functions. They exhibit strong repair and regeneration capabilities, enabling partial or complete modification, and reconstruction of the immune system during their differentiation into immune cells. The pathogenesis of SLE is associated with defects in the bone marrow microenvironment primarily involving hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) and MSCs. Through extensive research, stem cell-based therapies have demonstrated successful applications in treating SLE.

Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation

Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) has been widely utilized in the treatment of SLE since Marmont et al. first reported successful autologous bone marrow stem cell transplantation (auto-BM-SCT) for severe SLE in 1997, demonstrating favorable therapeutic outcomes. HSCT commonly employs stem cells derived from bone marrow, peripheral blood, or umbilical cord blood and can be categorized as either autologous or allogeneic based on donor type. The primary mechanism underlying HSCs treatment involves immune reconstitution following pretreatment chemotherapy and HSCT. By eliminating abnormal immunity, HSCs facilitate the regeneration of normal cells and establish a new immune tolerance mechanism through thymus modification.

However, studies have identified several limitations associated with both auto-HSCT and allo-HSCT for SLE treatment. Auto-HSCT offers ease of sourcing, high safety profile, and effectiveness; however, due to its inability to alter the genetic progression of the disease, it is associated with a high recurrence rate. Furthermore, research has indicated that HSCT therapy struggles to reverse kidney damage caused by lupus nephritis—particularly structural pathological changes. On the other hand, allo-HSCT presents challenges, such as limited availability of suitable donors, increased risk of graft-versus-host disease (GVHD), transplant-related mortality (TRM), elevated costs, comparable recurrence rates to auto-HSCT treatments, and potential development of secondary autoimmune diseases—contrary to therapeutic objectives—which limits its acceptance among most patients and restricts its clinical applications.

Mesenchymal Stem Cell Transplantation

In recent years, MSCs have been tried out for the treatment of refractory and severe SLE, mainly from bone marrow, umbilical cord, fat, gingiva, and so on. Bone marrow-derived MSCs (BM-MSCs) transplantation is the most common. The main mechanism by which MSCs play a therapeutic role is that MSC can play an immune regulatory role through intercellular contact or secretion of cytokines, and can return to the kidney, lung, and other tissues to play a role, inhibit the proliferation of T cells, including Th17 and Tfh cells, participate in the regulation of Th1/Th2 balance, and promote the generation of Treg cells. It can also inhibit the function of B cells and macrophages, thus playing a role in immune regulation and tissue repair.

Subsequently, numerous studies7,8 have reported that allotransplantation of human BM-MSCs could effectively manage the disease and enhance the prognosis of refractory SLE patients. However, as research progresses, some scholars have discovered that although BM-MSCs are widely present in the hematopoietic microenvironment and play a crucial role in hemocytogenesis and immune regulation 9 , they exhibit dysfunction in SLE patients with reduced cytokine secretion and immune regulatory abilities, decreased proliferation and differentiation capacities, abnormal cell structure, and significantly increased intracellular oxidative stress 10 . Animal experimental studies 11 also revealed that autologous BM-MSCs from SLE mice failed to migrate to target organs after transplantation in vivo, while MSCs transplanted between allogeneic groups still exhibited donor degeneration, genetic instability, and immune rejection. Therefore, exploring novel sources of stem cells is imperative for overcoming clinical application limitations.

Human Amniotic Epithelial Stem Cell Transplantation

The amnion also referred to as the fetal membrane, is situated in the innermost layer of the placenta and constitutes the inner wall of the embryonic amniotic fluid cavity. It is a translucent and resilient membrane devoid of nerves, blood vessels, or lymphatic vessels. The amnion provides an optimal environment for embryo growth and development. With a thickness ranging from 0.02 to 0.5 mm, it can be anatomically divided into five distinct layers: epithelium, basal layer, dense layer, fibroblast layer, and sponge layer. The epithelial layer consists of a single sheet of amniotic epithelial cells (AECs), characterized by highly wrinkled surfaces on AECs. In total, there are approximately 200 million AECs that collectively cover an expansive surface area of up to 2 m2.

As early as 1981, Akle et al. 12 reported that human amniotic epithelial stem cells (hAESCs) did not express the A, B, C, DR antigens, and β2-microglobulin of human white blood cells. Therefore, the immunogenicity of the amniotic membrane is remarkably low with minimal risk of immune rejection. This exceptional immunological compatibility, combined with its abundant availability (obtained during childbirth), positions the amniotic membrane as a readily accessible natural polymer biomaterial. Since the beginning of the last century, it has been recognized that the amniotic membrane serves as an excellent surgical aid in treating skin injuries, such as burns, ulcers, scars, and surgical wound healing13–16.

Before the eighth day after fertilization, the epithelial stem cells in development share many characteristics with embryonic stem cells. According to a study by Miki et al. 17 . In 2005, amniotic epithelial stem cells have similar molecular markers to embryonic stem cells, except for telomerase expression. This suggests that they have the potential to differentiate into the three germ layers unique to embryonic stem cells. Further research has confirmed their ability to differentiate into nerve cells, cardiomyocytes, and hepatocytes, and to successfully treat animal models of diseases, such as Parkinson’s disease, myocardial infarction, and liver injury through transplantation18–20.

The findings suggest that hAESCs possess embryonic stem cell-like properties and exhibit robust differentiation potential into three dermal tissues. They demonstrate excellent immune tolerance without the need for human leukocyte antigen (HLA) matching or genotype compatibility, while also secreting a diverse range of anti-inflammatory factors with potent anti-inflammatory capabilities. Furthermore, due to their lack of telomerase activity, hAESCs do not undergo uncontrolled proliferation or pose a risk of carcinogenesis, ensuring the safety of transplantation. Clinical investigations conducted in the United States have demonstrated minimal instances of immune rejection following local or intravenous administration of hAESC in both healthy volunteers and patients. These results highlight the limited antigen-presenting ability and distinctive immunological characteristics exhibited by hAESCs. Notably, pioneering research conducted at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center in 2006 showcased the therapeutic potential of hAESCs in corneal injury treatment, revealing their capacity to repair damaged corneas and facilitate vision recovery 21 . Subsequently, researchers have successfully applied hAESC transplantation techniques to various autoimmune diseases, including multiple sclerosis, autoimmune ovarian disease, experimental autoimmune thyroiditis, SLE, Parkinson’s disease, chronic liver fibrosis, non-alcoholic steatohepatitis, idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, Alzheimer’s disease, and premature ovarian failure22–30. And the immunomodulatory function of human amniotic epithelial cells (hAECs) in different Autoimmune diseases (ADs) is shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Immunomodulatory Function of hAECs in Different ADs.

| Diseases | Transplantation method | Species | Outcome | Repair mechanism | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Multiple sclerosis | Intravenously (2 × 106 hAECs) | Mice | Reducing monocyte/macrophage infiltration and demyelination | Mediating immunosuppression via secreting TGF-β and PGE2; promoting Th2 cytokine shift | 22 |

| Autoimmune ovarian disease | Intravenously (2 × 106 hAECs) | Mice | Restoring ovarian function; upregulating Treg cells; reducing the inflammatory reaction | Modulating macrophage function by paracrine factors (TGF-β and MIF) | 23 |

| Experimental autoimmune thyroiditis; systemic lupus erythematosus | Intravenously (1.5 × 106 hAECs); intravenously (1.5 × 106 hAECs) | Mice | Preventing lymphocyte infiltration into the thyroid; improving the damage of thyroid follicular; reducing immunoglobulin profiles | Modulating the immune cell balance by downregulating the ratios of Th17/Treg cells; upregulating the proportion of B10 cells | 24 |

| Parkinson’s disease | Injection of tegmentum of the midbrain | Rats | Enhancing the survival of DA; protecting the morphological integrity of TH-positive neurons against toxic insult | hAEC-CM (neurotrophins, such as BDNF and NT-3) | 25 |

| Chronic liver fibrosis | Intravenous injection | Mice | Reducing collagen synthesis and macrophage infiltration; inducing macrophage toward M2 phenotype | hAEC-CM (anti-fibrosis, anti-inflammation) | 26 |

| Non-alcoholic steatohepatitis | Intraperitoneal injection | Mice | Reducing hepatic inflammation; inhibiting liver fibrosis | hAEC-CM (anti-inflammation; anti-fibrosis) | 27 |

| Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis | Intravenous injection; intranasal instillation | Mice | Reducing lung inflammation and fibrosis; improving tissue to airspace ratio | hAEC-exosomes (anti-inflammation; anti-fibrosis) | 28 |

| Alzheimer’s disease | Intracerebroventricular injection (1.2 × 105 cells) | Mice | Improving the spatial memory; increasing acetylcholine concentration and the number of hippocampal cholinergic neurites | Expressing stem cell-specific markers OCT-4 and Nanog | 29 |

| Premature ovarian failure | Intravenous injection (2 × 106 cells) | Mice | Promoting folliculogenesis; repairing ovarian function | Differentiating into granulosa cells expressing follicle-stimulating hormone receptor (FSHR) | 30 |

Comparison Between HSCT, MSCT, and hAESCT

The experience of patients with SLE treated by HSCs transplantation is reviewed and summarized: the curative effect is positive, but the incidence of adverse reactions is high, as well as the expense and the recurrence rate. Therefore, its clinical application is greatly limited. However, since 2007, Sun’s team for the first time successfully carried out allogeneic bone marrow-derived MSC transplantation (BM-MSCT) in the treatment of refractory SLE 31 . In the clinical study of patients with SLE, the long-term follow-up effective rate is 60%, and there is no obvious adverse reaction. There have been no clinical studies and only a few trials in SLE mice. These results demonstrated the immunoregulatory effect of hAECs for inflammation inhibition and injury recovery in SLE murine models 24 . The comparison between HSCT, mesenchymal stem cell transplantation (MSCT), and hAESCT is shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Comparison Between HSCT, MSCT, and hAESCT for SLE.

| HSCT | MSCT | hAESCT | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Therapeutic effect | Some SLE patients achieve remission, however, relapse rate is nearly 35% 31 | More than 50% SLE patients exhibited complete and partial clinical remission after MSCT. And MSCT induces remission in multi-organ dysfunctions including lupus nephritis 32 | No clinical studies and only a few trials in SLE mice. These results demonstrated the immunoregulatory effect of hAECs for inflammation inhibition and injury recovery in SLE murine models |

| Therapeutic mechanism | HSC itself seems to have no direct therapeutic effect; it depends on several other mechanisms: (1) High-dose immunosuppression during HSCT would eliminate autoreactive lymphocytes, and the development and re-organization of a self-tolerant immune system after HSCT would be effective 33 . (2) The level of regulatory T cell numbers changes, and the pathogenic T cell responses against auto-antigens are inhibited | The therapeutic effect of allogeneic MSCT is primarily dependent on the systemic immunoregulatory effects on various immune regulatory cells, including T cells, B cells, plasma cells, dendritic cells 34 , macrophages, and so on. MSCs also secrete a variety of anti-inflammatory cytokines that mediate immune response. Also, MSCs could be home to kidney, lung, liver, and spleen tissues and may contribute to regulate local inflammation 35 | In SLE mice, hAECs strikingly decreased the proportion of Th17 cells, and enhanced the proportion of Treg cells; repressed the auto-antibodies; reversed the development of hypergammaglobulinemia; downregulated production of the proinflammatory Th17 cytokine IL-17A and the Th1 cytokine IFN-γ 24 |

| Adverse events | Infection (CMV or bacterial/fungal) secondary AD, allergy, elevation of liver enzymes, bone pain, and heart failure, and so on 35 | Only a small number of patients have mild side effects, such as dizzy and warm sensation 32 | There have been no clinical studies and only a few trials in SLE mice |

| Cost | Relatively high expense for complicated cell conditioning and high-dose immunosuppressive drugs | MSCs have strong tissue repair function and multi-directional differentiation potential, such as HSCs, and exhibit low immunogenicity and immunosuppressive ability. It has advantages in terms of patient acceptance and the cost is much lower than that of HSCs | hAESCs have abundant availability from discarded fetal tissues with convenient and safe collection procedures, large cell numbers, low immunogenicity, and negligible risk of immune response upon transplantation into humans. Thus, the cost is much lower than that of HSCs and MSCs |

AD, autoimmune diseases; HSC, Hematopoietic stem cell; HSCT, HSCs transplant; MSCs, mesenchymal stem cells; MSCT, MSC transplant; hAESC, human amniotic epithelial stem cells; hAESCT, hAESCs transplant; SLE, systemic lupus erythematosus.

Conclusion

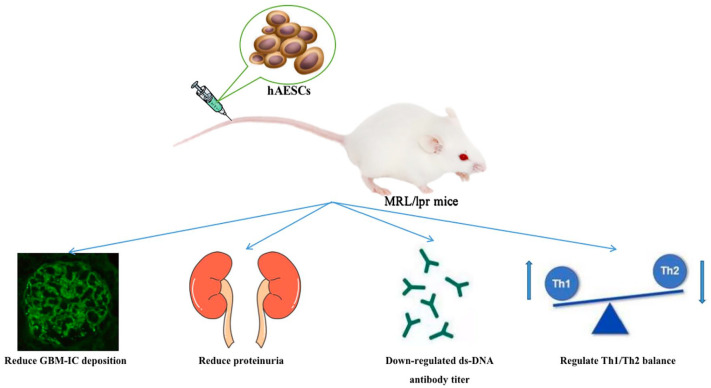

Based on the aforementioned research background, the author proposes that transplantation of hAESCs is a feasible and promising approach for treating SLE. To support this claim, the author refers to previous experimental studies conducted by other researchers using stem cell transplantation in SLE model mice 36 . To validate these findings, the author designs essential confirmatory experiments as follows:

The MRL/LPR mouse37–47, which is widely recognized as an animal model for studying SLE due to its consistent pathological changes with kidney pathology observed in human SLE patients (such as the presence of immune complexes in the mesangial region of glomerulus), was selected. This model has been extensively utilized in various fundamental experimental investigations related to SLE.

Green fluorescent protein (GFP)-labeled hAESCs were intravenously injected into the tail vein of MRL/LPR mice to investigate the reparative function of these cells on the kidneys. Initially, both control and experimental groups of MRL/LPR mice exhibited immune complexes in the mesangial region. It was anticipated that in the control group, tissue immune complexes would be distributed lamellarly and concentrated, whereas in the experimental group transplanted with human AECs, immune complexes would be distributed punctately, significantly lower than those in the control group treated with normal saline48–50. Furthermore, it was hypothesized by the author that within 10 weeks post-transplantation of hAESCs, there would be statistically significant differences observed in urinary protein levels between the two groups of MRL/LPR mice. Theoretically, the rate of increase in urinary protein concentration would be significantly higher in the control group compared with that in the experimental group. In addition, it could be inferred that serum ds-DNA antibody concentration an indicator for lupus nephritis activity would be notably lower in the experimental group as compared with controls.

In addition, it would be valuable to investigate the proportion of helper T cell subsets in the spleen of mice, specifically focusing on the Th1/Th2 ratio. Dendritic cells typically exert an immunomodulatory role by promoting Th1 cell proliferation and maintaining Th1/Th2 balance. Previous research has demonstrated a decrease in the proportion of Th1 cells and an increase in Th2 cells, resulting in a decreased Th1/Th2 ratio within the spleen of MRL/lpr mice 51 . Theoretically, treatment with hAESCs could lead to an increased proportion of both Th1 and Th2 cells, particularly enhancing the abundance of Th1 cells. Consequently, this may contribute to an elevated Th1/Th2 value, indicating that hAESCs possess the potential for promoting the proliferation of Th1 cells and facilitating transformation from Th2 to Th1 cells as a means to restore immune homeostasis.

By evaluating these core indicators through statistical analysis, it can be theoretically concluded that hAESCs have inhibitory effects on pathological injury associated with SLE mice while regulating the lymphocyte ratio between Th1 and TH2 subsets. This multifaceted approach suggests that hAESC therapy holds promise for treating SLE (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

The hypothesis that transplantation of hAESCs exerts a therapeutic effect in MRL/LPR mice.

A lot of progress has been made in researching and developing hAESCs52–54, and Shanghai Siao Biotechnology Co., Ltd has been dedicated to this field for a long time. They focus on creating stem cell products that meet high clinical-grade standards, which is important for clinical investigations of hAESCs. The company has also formed strong collaborations with hospitals to conduct research on stem cell technology for treating related diseases, as well as studies on clinical applications and establishing an amniotic stem cell bank. Together with their partners, they have published research reports and obtained patent authorizations in China and the United States.

In conclusion, the author posits that prioritizing improvements in preliminary experimental studies is crucial. If the results confirm the immunomodulatory effects of hAESCs on immune complex deposition in the mesangial region of MRL/LPR mice, reduction in proteinuria, decrease in serum ds-DNA antibody titer and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) level, as well as regulation of Th1/Th2 balance can be achieved. Consequently, due to their abundant availability from discarded fetal tissues with convenient and safe collection procedures, large cell numbers, low immunogenicity, and negligible risk of immune response upon transplantation into humans; hAESCs emerge as a promising and superior source for stem cell transplantation therapy to treat SLE.

Footnotes

Authors’ Contributions: The literature review was conducted by XLP, while DQD conceived and planned the research. Article collection was performed by XLP, whereas data collection and analysis were carried out by ZY and LN. The initial manuscript was written collaboratively by XLP, JLN, and SXW with assistance from others. Finally, all authors read, corrected, and approved the final version.

Data Availability Statement: The data are available upon request from the corresponding author.

Ethical Approval: This study was approved by our institutional review board.

Statement of Human and Animal Rights: This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects.

Statement of Informed Consent: There are no human subjects in this article and informed consent is not applicable.

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This research was supported by the seventh installment of the National Traditional Chinese Medicine Experts Academic Experience Inheritance Project (National Traditional Chinese Medicine Teaching Letter [2021] No. 272) and the Traditional Chinese Medical Science and Technology Project of Zhejiang Province (Grant No. 2022ZB130), and the Health Science and Technology Project of Zhejiang Province (Grant No. 2023KY870).

ORCID iD: Liping Xu  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3683-6056

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3683-6056

References

- 1. Nie Y, Lau C, Lie A, Chan GC, Mok MY. Defective phenotype of mesenchymal stem cells in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Lupus. 2010;19(7):850–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Li X, Liu L, Meng D, Wang D, Zhang J, Shi D, Liu H, Xu H, Lu L, Sun L. Enhanced apoptosis and senescence of bone-marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Stem Cells. 2012;21(13):2387–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Gu Z, Tan W, Feng G, Meng Y, Shen B, Liu H, Cheng C. Wnt / beta-catenin signaling mediates the senescence of bone marrow-mesenchymal stem cells from systemic lupus erythematosus patients through the p53 / p21 path- way. Mol Cell Biochem. 2014;387(1–2):27–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Wang D, Feng X, Lu L, Konkel JE, Zhang H, Chen Z, Li X, Gao X, Lu L, Shi S, Chen W, et al. A CD8 T cell/indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase axis is required for mesenchymal stem cell suppression of human systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 2014;66(8):2234–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Feng X, Che N, Liu Y, Chen H, Wang D, Li X, Chen W, Ma X, Hua B, Gao X, Tsao BP, et al. Restored immunosuppressive effect of mesenchymal stem cells on B cells after olfactory 1 / early B cell factor-associated zinc-finger protein down-regulation in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2014;66(12):3413–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Fathollahi A, Gabalou NB, Aslani S. Mesenchymal stem cell transplantation in systemic lupus erythematous, a mesenchymal stem cell disorder. Lupus. 2018;27(7):1053–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Wang D, Sun L. Mesenchymal stem cell transplantation for treatment of severe autoimmune diseases. Chin J Pract Intern Med. 2015;35(10):831–34. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Liang J, Sun L. Basic and clinical study of mesenchymal stem cells in the treatment of systemic lupus erythematosus. Zhejiang Med. 2017;39(21):1836–41. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Petinati N, Shipounova I, Sats N, Dorofeeva A, Sadovskaya A, Kapranov N, Tkachuk Y, Bondarenko A, Muravskaya M, Kotsky M, Kaplanskaya I, et al. Multipotent Mesenchymal Stromal Cells from Porcine Bone Marrow, Implanted under the Kidney Capsule, form an Ectopic Focus Containing Bone, Hematopoietic Stromal Microenvironment, and Muscles. Cells. 2023;12(2):268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ruan G, Wang J, Yang J, et al. Osteogenic and lipogenic differentiation of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells in mice with systemic lupus erythematosus. J Tissue Eng. 2014;18(1):1–6. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Liao J, Chang C, Wu H, Lu Q. Cell-based therapies for systemic lupus erythematosus. Autoimmun Rev. 2015;14(1):43–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Akle CA, Adinolfi M, Welsh KI, Leibowitz S, McColl I. Immunogenicity of human amniotic epithelial cells after transplantation into volunteers. Lancet. 1981;2(8254):1003–1005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Farhadihosseinabadi B, Farahani M, Tayebi T, Jafari A, Biniazan F, Modaresifar K, Moravvej H, Bahrami S, Redl H, Tayebi L, Niknejad H. Amniotic membrane and its epithelial and mesenchymal stem cells as an appropriate source for skin tissue engineering and regenerative medicine. Artif Cells Nanomed Biotechnol. 2018;46(suppl 2):431–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Pan C, Lang H, Zhang T, Wang R, Lin X, Shi P, Zhao F, Pang X. Conditioned medium derived from human amniotic stem cells delays H2O2–induced premature senescence in human dermal fibroblasts. Int J Mol Med. 2019;44(5):1629–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Zhao B, Liu JQ, Yang C, Zheng Z, Zhou Q, Guan H, Su LL, Hu DH. Human amniotic epithelial cells attenuate TGF-β1-induced human dermal fibroblast transformation to myofibroblasts via TGF-β1/Smad3 pathway. Cytotherapy. 2016;18(8):1012–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Li JY, Ren KK, Zhang WJ, Xiao L, Wu HY, Liu QY, Ding T, Zhang XC, Nie WJ, Ke Y, Deng KY, et al. Human amniotic mesenchymal stem cells and their paracrine factors promote wound healing by inhibiting heat stress-induced skin cell apoptosis and enhancing their proliferation through activating PI3K/AKT signaling pathway. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2019;10(1):247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Miki T, Lehmann T, Cai H, Stolz DB, Strom SC. Stem cell characteristics of amniotic epithelial cells. Stem Cells. 2005;23(10):1549–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Sonntag KC, Song B, Lee N, Jung JH, Cha Y, Leblanc P, Neff C, Kong SW, Carter BS, Schweitzer J, Kim KS. Pluripotent stem cell-based therapy for Parkinson’s disease:Current status and future prospects. Prog Neurobiol. 2018;168:1–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Henry JJD, Delrosario L, Fang J, Wong SY, Fang Q, Sievers R, Kotha S, Wang A, Farmer D, Janaswamy P, Lee RJ, et al. Development of injectable amniotic membrane matrix for postmyocardial infarction tissue repair. Adv Healthc Mater. 2020;9(2):e1900544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Bai C, Zhang H, Zhang X, Yang W, Li X, Gao Y. MiR-15/16 mediate crosstalk between the MAPK and Wnt/β-catenin pathways during hepatocyte differentiation from amniotic epithelial cells. Biochim Biophys Acta Gene Regul Mech. 2019;1862(5):567–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Nakamura T, Inatomi T, Sotozono C, Ang LP, Koizumi N, Yokoi N, Kinoshita S. Transplantation of autologous serum-derived cultivated corneal epithelial equivalents for the treatment of severe ocular surface disease. Ophthalmology. 2006;113(10):1765–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Abbasi-Kangevari M, Ghamari SH, Safaeinejad F, Bahrami S, Niknejad H. Potential therapeutic features of human amniotic mesenchymal stem cells in multiple sclerosis: immunomodulation, inflammation suppression, angiogenesis promotion, oxidative stress inhibition, neurogenesis induction, MMPs regulation, and remyelination stimulation. Front Immunol. 2019;10:238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Zhang Q, Huang Y, Sun J, Gu T, Shao X, Lai D. Immunomodulatory effect of human amniotic epithelial cells on restoration of ovarian function in mice with autoimmune ovarian disease. Acta Biochim Biophys Sin Shanghai. 2019;51(8):845–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Tan B, Yuan W, Li J, Yang P, Ge Z, Liu J, Qiu C, Zhu X, Qiu C, Lai D, Guo L, et al. Therapeutic effect of human amniotic epithelial cells in murine models of Hashimoto’s thyroiditis and Systemic lupus erythematosus. Cytotherapy. 2018;20(10):1247–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kakishita K, Nakao N, Sakuragawa N, Itakura T. Implantation of human amniotic epithelial cells prevents the degeneration of nigral dopamine neurons in rats with 6-hydroxydopamine lesions. Brain Res. 2003;980(1):48–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Alhomrani M, Correia J, Zavou M, Leaw B, Kuk N, Xu R, Saad MI, Hodge A, Greening DW, Lim R, Sievert W. The human amnion epithelial cell secretome decreases hepatic fibrosis in mice with chronic liver fibrosis. Front Pharmacol. 2017;8:748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kuk N, Hodge A, Sun Y, Correia J, Alhomrani M, Samuel C, Moore G, Lim R, Sievert W. Human amnion epithelial cells and their soluble factors reduce liver fibrosis in murine non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;34(8):1441–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Tan JL, Lau SN, Leaw B, Nguyen HPT, Salamonsen LA, Saad MI, Chan ST, Zhu D, Krause M, Kim C, Sievert W, et al. Amnion epithelial cell-derived exosomes restrict lung injury and enhance endogenous lung repair. Stem Cells Transl Med. 2018;7(2):180–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Xue SR, Chen CF, Dong WL, Hui GZ, Liu TJ, Guo LH. Intracerebroventricular transplantation of human amniotic epithelial cells ameliorates spatial memory deficit in the doubly transgenic mice coexpressing APPswe and PS1DeltaE9-deleted genes. Chin Med J. 2011;124(17):2642–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Wang F, Wang L, Yao X, Lai D, Guo L. Human amniotic epithelial cells can differentiate into granulosa cells and restore folliculogenesis in a mouse model of chemotherapy-induced premature ovarian failure. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2013;4(5):124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Yuan X, Sun L. Stem Cell Therapy in Lupus. Rheumatol Immunol Res. 2022;3(2):61–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Shi D, Wang D, Li X, Zhang H, Che N, Lu Z, Sun L. Allogeneic transplantation of umbilical cord-derived mesenchymal stem cells for diffuse alveolar hemorrhage in systemic lupus erythematosus. Clin Rheumatol. 2012;31(5):841–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Pal R, Hanwate M, Jan M, Totey S. Phenotypic and functional comparison of optimum culture conditions for upscaling of bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells. J Tissue Eng Regen Med. 2019;3:163–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Yuan X, Qin X, Wang D, Zhang Z, Tang X, Gao X, Chen W, Sun L. Mesenchymal stem cell therapy induces FLT3L and CD1c + dendritic cells in systemic lupus erythematosus patients. Nat Commun. 2019;10:2498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Zhang Q, Lai D. Application of human amniotic epithelial cells in regenerative medicine: a systematic review. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2020;11(1):439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Ma L, Xue W, Tan J. Induced pluripotent stem cell transplantation for the treatment of systemic lupus erythematosus in mice. J Tissue Eng. 2019;23(33):5286–92. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Qiu F, Li T, Zhang K, Wan J, Qi X. CD4(+) B220(+) TCRγδ (+) T cells produce IL-17 in lupus-prone MRL/lpr mice. Int Immunopharmacol. 2016;38:31–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Wang H, Lu M, Zhai S, Wu K, Peng L, Yang J, Xia Y. ALW peptide ameliorates lupus nephritis in MRL/lpr mice. Arthritis Res Ther. 2019;21(1):261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Dang WZ, Li H, Jiang B, Nandakumar KS, Liu KF, Liu LX, Yu XC, Tan HJ, Zhou C. Therapeutic effects of artesunate on lupus-prone MRL/lpr mice are dependent on T follicular helper cell differentiation and activation of JAK2-STAT3 signaling pathway. Phytomedicine. 2019;62:152965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Rohraff DM, He Y, Farkash EA, Schonfeld M, Tsou PS, Sawalha AH. Inhibition of EZH2 ameliorates Lupus-like disease in MRL/lpr mice. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2019;71(10):1681–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Imaruoka K, Oe Y, Fushima T, Sato E, Sekimoto A, Sato H, Sugawara J, Ito S, Takahashi N. Nicotinamide alleviates kidney injury and pregnancy outcomes in lupus-prone MRL/lpr mice treated with lipopolysaccharide. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2019;510(4):587–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Machida T, Sakamoto N, Ishida Y, Takahashi M, Fujita T, Sekine H. Essential roles for mannose-binding lectin-associated serine protease-1/3 in the development of lupus-like glomerulonephritis in MRL/lpr mice. Front Immunol. 2018;9:1191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Shi Y, Yao W, Sun L, Li G, Liu H, Ding P, Hu W, Xu H. The new complement inhibitor CRIg/FH ameliorates lupus nephritis in lupus-prone MRL/lpr mice. BMC Nephrol. 2019;20(1):424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Caza TN, Fernandez DR, Talaber G, Oaks Z, Haas M, Madaio MP, Lai ZW, Miklossy G, Singh RR, Chudakov DM, Malorni W, et al. HRES-1/Rab4-mediated depletion of Drp1 impairs mitochondrial homeostasis and represents a target for treatment in SLE. Ann Rheum Dis. 2014;73(10):1888–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Sugiyama N, Nakashima H, Yoshimura T, Sadanaga A, Shimizu S, Masutani K, Igawa T, Akahoshi M, Miyake K, Takeda A, Yoshimura A, et al. Amelioration of human lupus-like phenotypes in MRL/lpr mice by overexpression of interleukin 27 receptor alpha (WSX-1). Ann Rheum Dis. 2008;67(10):1461–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Liu D, Kou X, Chen C, Liu S, Liu Y, Yu W, Yu T, Yang R, Wang R, Zhou Y, Shi S. Circulating apoptotic bodies maintain mesenchymal stem cell homeostasis and ameliorate osteopenia via transferring multiple cellular factors. Cell Res. 2018;28(9):918–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Knight JS, Subramanian V, O’Dell AA, Yalavarthi S, Zhao W, Smith CK, Hodgin JB, Thompson PR, Kaplan MJ. Peptidylarginine deiminase inhibition disrupts NET formation and protects against kidney, skin and vascular disease in lupus-prone MRL/lpr mice. Ann Rheum Dis. 2015;74(12):2199–2206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Celhar T, Fairhurst AM. Modelling clinical systemic lupus erythematosus: similarities, differences and success stories. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2017;56(suppl_1):188–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Floris A, Piga M, Cauli A, Mathieu A. Predictors of flares in systemic lupus erythematosus: preventive therapeutic intervention based on serial anti-dsDNA antibodies assessment. Analysis of a monocentric cohort and literature review. Autoimmun Rev. 2016;15(7):656–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Li A, Guo F, Pan Q, Chen S, Chen J, Liu HF, Pan Q. Mesenchymal Stem Cell Therapy: Hope for Patients With Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. Front Immunol. 2021;12:728190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Wang D, Huang S, Yuan X, Liang J, Xu R, Yao G, Feng X, Sun L. The regulation of the Treg/Th17 balance by mesenchymal stem cells in human systemic lupus erythematosus. Cell Mol Immunol. 2017;14(5):423–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Xu Y, Cai S, Wang Q, Cheng M, Hui X, Dzakah EE, Zhao B, Chen X. Multi-lineage human endometrial organoids on acellular amniotic membrane for endometrium regeneration. Cell Transplant. 2023;32:9636897231218408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Basile M, Centurione L, Passaretta F, Stati G, Soritau O, Susman S, Gindraux F, Silini A, Parolini O, Di Pietro R. Mapping of the human amniotic membrane: In situ detection of microvesicles secreted by amniotic epithelial cells. Cell Transplant. 2023;32:9636897231166209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Ling L, Hou J, Wang Y, Shu H, Huang Y. Effects of low-intensity pulsed ultrasound on the migration and homing of human amnion-derived mesenchymal stem cells to ovaries in rats with premature ovarian insufficiency. Cell Transplant. 2022;31:9636897221129171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]