Abstract

Background:

The exact incidence of shoulder dislocation in the general population of the United States (US) has yet to be well studied.

Purpose:

To establish the current incidence and patterns of shoulder dislocations in the US, especially regarding sports-related activity.

Study Design:

Descriptive epidemiology study.

Methods:

This was a retrospective analysis of shoulder dislocations encountered in emergency departments in the US between 1997 and 2021 as recorded in the National Electronic Injury Surveillance System (NEISS). Data were further analyzed according to patient age, sex, and sports participation. Information from the United States Census Bureau was used to determine the overall incidence of dislocations.

Results:

A total of 46,855 shoulder dislocations were identified in the NEISS database, representing a national estimate of 1,915,975 dislocations (mean 25.2 per 100,000 person-years). The mean patient age was 35.3 years. More than half of the dislocations (52.5%) were sports-related, and basketball (16.4%), American football (15.6%), and cycling (9%) were the sports most commonly associated with dislocation. Most dislocations (72.1%) occurred in men. This disparity by sex was more significant for sports-related dislocations (86.1% in men) than nonsports-related dislocations (56.7% in men; P < .001). With sports-related dislocations, people <21 years experienced a significantly higher proportion versus those >39 years (44.6% vs 14.9%; P < .001), while the opposite distribution was seen with nonsports-related dislocations (<21 years: 12% vs >39 years: 51.7%; P < .001). Women outnumbered men with shoulder dislocation among people >61 years.

Conclusion:

Sports-related shoulder dislocations were more common among younger and male individuals than older and female individuals. Contact sports such as basketball and American football were associated with more shoulder dislocations compared with noncontact sports.

Keywords: glenohumeral, sports, trauma, dislocation

The shoulder (glenohumeral) joint comprises the humeral head rotating within the glenoid socket. While this mobile anatomy increases the range of motion, it also predisposes the shoulder to instability and dislocation.5,15,23 The shoulder is the most commonly dislocated large joint in the body.3,4,5,15,22,23 Previous studies have estimated that the incidence of shoulder dislocations is 11.2 to 49.5 per 100,000 person-years in the United States (US) and 15.3 to 56.3 per 100,000 person-years in other countries.2,6,9,10,16,19,22,23 The data suggest that men are more likely than women to dislocate the shoulder, and dislocations occur in a bimodal age distribution with younger and older groups at most risk.9,10,16,22,23 The frequency and characteristics of sports-related dislocations in the general population have been studied; nonetheless, its trend over time has yet to be reported.

This study aimed to establish the current incidence and patterns of shoulder dislocations in the US, especially regarding sports-related activities. We hypothesized that most shoulder dislocations presenting to US emergency departments occurred during sports participation.

Methods

This study was determined to be exempt from ethics committee approval, as it did not involve human subject research. This was a retrospective descriptive epidemiologic study using the National Electronic Injury Surveillance System (NEISS), a publicly available database compiled by the US Consumer Product Safety Commission (CPSC). 20 The NEISS consists of a probability sample of 100 hospitals nationwide that have at least 6 beds and provide 24-hour emergency department (ED) services. The CPSC uses statistical weights (inverse probability of strata-specific selection) to the NEISS sample data to allow calculations of national estimates of the number of injuries treated in EDs. 20 These hospitals are selected based on location (eg, urban, suburban, and rural) to represent the US population. Patient information is collected from each NEISS hospital for every ED visit, and the total number of shoulder (glenohumeral joint) dislocations treated in hospital EDs nationwide can be estimated from this sample using statistical weighting factors provided by the CPSC. 20 The CPSC considers a national estimate to be unstable and potentially unreliable when the estimate is <1200, the number of cases is <20, or the coefficient of variation 20 is >33%.

We queried the NEISS database for visits recorded with the diagnosis of “dislocation (code 55)” and the body part affected of “shoulder, including clavicle, collarbone (code 30)” between 1997 and 2021. The NEISS does not report injuries associated with automobiles, motorcycles, trains, boats, and planes. We searched and reviewed narratives for terms such as “shoulder separation, acromioclavicular joint separation, sternoclavicular joint, subluxation, and nursemaid elbow,” as they are not actual glenohumeral joint dislocations. A total of 1660 cases were excluded from analysis. Age was categorized based on decades of life and similar frequency into 3 groups: <21, 21 to 39, and >39 years. Injury mechanism was categorized as “sports-related” (sports-related dislocations have codes related to sports [eg, soccer, golf, water skiing]) and “nonsports-related.”

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS software (Version 27.0; IBM). Unless otherwise noted, all analyses are based on weighted estimates using complex sampling analysis to account for weighting factors. Using data from the US Census Bureau, we calculated the injury incidence (national estimate devided by US annual population estimate) from 1997 through 2021. Descriptive statistics were used to examine the frequency, mean, median, and range for all variables. Injury proportion ratios with 95% CIs were calculated to compare the proportions of injuries sustained by sex. P < .05 and confidence intervals not containing 1 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Overall, 46,855 shoulder dislocations were recorded in the NEISS database, representing a national estimate of 1,915,957 dislocations from 1997 to 2021. The mean patient age was 35.3 years. Patient and injury characteristics are summarized in Table 1. Men experienced the majority of overall shoulder dislocations (72.1%). This disparity by sex was more significant for sports-related injuries (86.1% in men) than nonsports-related injuries (56.7% in men; P < .001). Slightly more than half (52.5%) of shoulder dislocations were sports related. Most patients with race profiles recorded were white. The most common reported injury locations were at home (33.7%) and during recreation/sport (25.9%). Most patients (96%) were discharged from the ED after treatment (Table 1).

Table 1.

Patient and Injury Characteristics of Shoulder Dislocations Seen in the US Emergency Departments From 1997 to 2021 a

| Characteristic | NEISS Database | National Estimate | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Cases, n | Mean Cases per Year, n (%) | Weighted Cases, n (95% CI) | Weighted Mean Cases per Year, n | |

| Total | 46,855 | 1874 (100) | 1,915,957 (1,517,047-2,314,867) | 76,638 |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 33,793 | 1352 (72.1) | 1,372,077 (1,077,585-1,666,569) | 54,883 |

| Female | 13,055 | 522 (27.9) | 543,864 (435,808-651,920) | 21,755 |

| Age, y | ||||

| <21 | 13,645 | 546 (29.1) | 502,668 (398,441- 606,895) | 20,107 |

| 21-39 | 18,029 | 721 (38.5) | 743,408 (574,196-912,620) | 29,736 |

| >39 | 15,130 | 605 (32.3) | 668,478 (592,773-807,183) | 26,739 |

| Race | ||||

| White | 20,957 | 838 (44.7) | 944,748 (711,531-1,177,965) | 37,790 |

| Black | 6,335 | 253 (13.5) | 196,652 (126,097-267,206) | 7866 |

| Asian | 462 | 18 (1) | 15,674 (5,026-26,323) | 627 |

| American Indian/Alaska Native | 59 | 2 (0.1) | 2997 (200-5795) | 120 |

| Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander | 26 | 1 (0.1) | 1463 (456-2470) | 59 |

| Other | 2679 | 107 (5.7) | 102,921 (53,624-152,218) | 4117 |

| Not recorded | 13,040 | 522 (27.8) | 500,263 (336,857-663,670) | 20,011 |

| Mechanism of injury | ||||

| Sports related | 24,606 | 984 (52.5) | 997,529 (763,684-1,231,373) | 39,901 |

| Nonsports related | 22,237 | 889 (47.5) | 918,185 (734,587-1,101,783) | 36,727 |

| Incident locale | ||||

| Home | 15,813 | 633 (33.7) | 670,823 (534,311-807,335) | 26,833 |

| Place of recreation/sport | 12,145 | 486 (25.9) | 497,992 (362,997-632,986) | 19,920 |

| Other public property | 2611 | 104 (5.6) | 108,133 (86,178-130,089) | 4325 |

| School | 2072 | 83 (6.2) | 85,969 (64,159-107,780) | 3439 |

| Street/highway | 1249 | 50 (4.4) | 66,537 (37,568-95,505) | 2661 |

| Farm/ranch | 58 | 2 (0.1) | 2,795 (1566-4025) | 112 |

| Not recorded | 12,630 | 505 (27) | 483,697 (354,828-612,566) | 17,548 |

| Disposition | ||||

| Treated and released | 44,964 | 1799 (96) | 1,833,671 (1449,410-2,217,932) | 73,347 |

| Treated and admitted for hospitalization | 1322 | 53 (2.8) | 54,924 (40,852-68,997) | 2197 |

| Treated and transferred to another hospital | 202 | 8 (0.4) | 12,304 (8470-16,137) | 492 |

| Left without being seen/left against medical advice | 181 | 7 (0.4) | 7588 (3209-11,966) | 304 |

| Held for observation | 169 | 7 (0.4) | 6888 (4,345-9531) | 276 |

NEISS, National Electronic Injury Surveillance System US, United States.

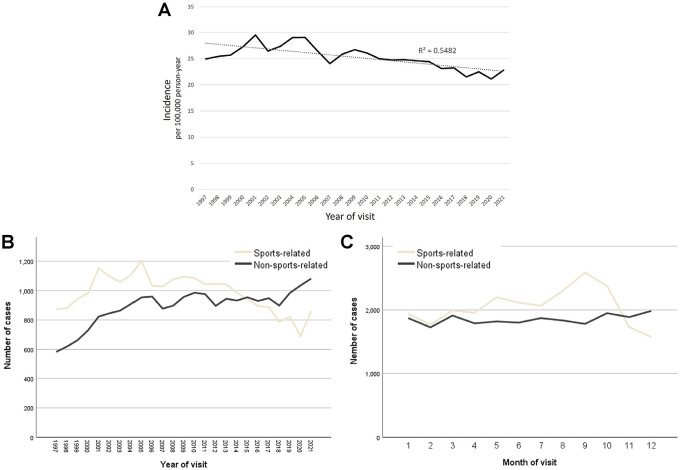

The overall incidence of shoulder dislocations was 25.2 per 100,000 person-years, with a decreasing trend in dislocations from the peak recorded in 2001 (Figure 1A). Over the 25 years of the study period, there was some variability in the number of sports-related and nonsports-related shoulder dislocations (Figure 1B). Sports-related dislocations were more common between September and November (Figure 1C).

Figure 1.

(A) Estimated incidence of shoulder dislocation by year of emergency department visit. (B and C) Number of shoulder dislocation stratified according to injury mechanism by (B) the year and (C) the month of visit.

Sports-related dislocations occurred significantly more in people aged <21 years (44.6%) versus >39 years (14.9%; P < .001). The opposite was true for nonsports-related dislocations, which occurred significantly more in people >39 years (51.7% of total nonsports-related dislocations) than in people <21 years (12%; P < .001). People aged 21 to 39 years experienced the most shoulder dislocations overall (38.5%) and were still more likely to dislocate their shoulder playing sports (55.3%) than not (44.7%; P < .001). Figure 2 demonstrates the distribution of dislocations by age when stratified according to sex and injury mechanism. The peak age overall was 17 years (17 years for men and 16 years for women) (Figure 2A). Among people >61 years, women outnumbered men in dislocations. The peak age for sports-related dislocations was 17 years, and for nonsports-related dislocations was 21 years (Figure 2B).

Figure 2.

Shoulder dislocation by age, stratified according to (A) sex and (B) injury mechanism.

Of the sports-related incidents, basketball (16.4%), American football (15.6%), and cycling (9.0%) accounted for the most dislocations. Figure 3 shows the 20 sports where shoulder dislocations occurred most often, stratified by sex. Common causes of nonsports-related dislocations included falls (eg, from bed, in the shower, or on stairs), tripping over an object (eg, carpet, pet leashes), and contact with an object (eg, desk). Men experienced more dislocations playing sports (62.7%) (P < .001). In contrast, women experienced more dislocations outside of sports (73.8%) (P < .001)—Figure 4 reports shoulder dislocations by injury mechanism, stratified according to sex and age group.

Figure 3.

Percentage of shoulder dislocations by sport, stratified according to sex.

Figure 4.

Shoulder dislocation by injury mechanism, stratified according to (A) sex and (B) age category. Percentages represent a portion of the total dislocations.

Discussion

This was a nationwide retrospective epidemiologic study of shoulder dislocations over a period of 25 years; it is the longest study in the US population, with the largest number of dislocations. This study bolsters the previous epidemiologic studies already present in the literature by including more data points over a longer period of time. The incidence rate of shoulder dislocations calculated in this study is similar to those found by Zacchilli and Owens 23 and Owens et al.13,14

The incidence of shoulder dislocation slightly declined from 1997 to 2021 in a mostly linear fashion (Figure 1A), although the trend did not have a very strong statistical significance. The reason for this is unclear but could be due to increased injury prevention measures and awareness. Another hypothesis is that better prehospital management of these injuries developed over time, leading to more successful on-field reductions of acute dislocations and fewer ED presentations for this problem. Other possible reasons are the proliferation of urgent care centers, which may have treated many of these patients, or perhaps advances in surgical stabilization techniques for patients with glenohumeral joint instability resulting in minimizing recurrence. These hypotheses are further supported by the graph in Figure 1B, which shows that sports-related dislocations have declined since about 2014, while nonsports-related dislocations have stayed the same or slightly increased during that period. Given that from 2012 to 2021 sports participation increased, 18 there must be another explanation for declining sports-related dislocations. As there has likely been more education regarding management of shoulder dislocations to physicians, athletic trainers, and other sports-related medical personnel during that period, perhaps many of these sports-related dislocations could be managed successfully outside of the ED. There was a sharp decline in sports-related dislocations during 2020 and 2021 and a sharp rise in nonsports-related dislocations during 2020 and 2021, almost certainly because of the COVID-19 pandemic that decreased or stopped sports participation during that period. A similar trend was noted in an Italian study published in 2020, showing a similar number of shoulder injuries in elderly patients during COVID-19 but a decreased number of sports-related injuries. 7

Sports-related dislocations occurred more often during September and October of each year (Figure 1C). As American football is the sport with the second most shoulder dislocations and September and October are peak American football months, this likely explains the higher incidence during these months of the year. A slight majority of shoulder dislocations occurred while patients were participating in sports. Previous studies have shown similar but slightly lower rates of sports-related shoulder dislocations.10,13,19,21,23 Men are more likely to dislocate their shoulders playing sports than women, who are more likely to dislocate their shoulders during nonsports-related activities.

Previous studies have demonstrated a bimodal distribution pattern,4,17,23 with the mean age of patients with dislocation presenting to US EDs in their 40s,17,23 and men presenting more frequently than women.1,6,23 Consistent with our findings, the patients with higher dislocation rates were younger men or older women.1,13,14,17,23 This bimodal nature may be because glenohumeral joint dislocation is more common among younger people participating in sporting activities and older people who may be vulnerable to accidents such as falls.

In the 2010 US ED study by Zacchilli and Owens, 23 the incidence rate of men to women with shoulder dislocation was almost 3 to1 (71.8% vs 28.2%). The mean age of incidence of both sexes was 34.5 years, and men aged 20 to 29 years were at the greatest risk of dislocation. Men were more likely to present for dislocation before 60 years; nonetheless, this trend shifted to favor women with ages >60 years. 23 The greatest number of women with shoulder dislocations occurred 23 in ages 80 to 89 years. Our study does not stratify the patients into the same age ranges as the Zacchilli et al study, 23 but the mean age (34.6 years) and pattern of men and younger patients presenting with higher frequency were similar (Figures 2 and 4). In our study, a higher overall incidence of men presented to the ED; nevertheless, this shifts to favor women in the seventh decade of life.

Other studies in the US population have shown varying distributions of shoulder dislocation. In another small general population study by Simonet et al, 17 men were twice as likely as women to present with a shoulder dislocation. In patients >60 years, women were 3 times more likely to have a shoulder dislocation than men. The study evaluated rural and urban populations, and the mean ages of patients were 36.4 and 38.1 years in the two populations, respectively. A 2022 study by Albright et al, 1 which evaluated shoulder instability, showed a bimodal distribution with younger men and older women sustaining shoulder dislocations. Although our study does not include shoulder subluxations, the pattern is similar. In the 2009 study by Owens et al, 14 for 16 US military service members, the gross number of shoulder dislocations was much higher in men. This finding is likely confounded by the age and sex of the military population; however, men were twice as likely as women to sustain a dislocation when adjusted for sex. Men were found to have higher rates of injury, with a male incidence ratio of 1.95 in the military 14 versus 2.67 in collegiate athletes when compared with women. 13 Furthermore, the military population has different demands, including requirements to participate in sports and fitness drills, contributing to their instability episodes and recurrence.

These patterns continue in epidemiologic studies of individual countries worldwide. In the 2011 study of the incidence of shoulder dislocation in Oslo, men are just over twice as likely to present for a dislocation as women. 10 Men were most likely to dislocate their shoulders between the ages of 20 and 29 years. 10 A 1995 Swedish study by Nordquist and Petersson 14 and a 1989 study 10 of an urban population in Denmark showed an increased occurrence in younger men, which switches to female predominance after the sixth and seventh decades of life. Men in the United Kingdom were also found, in two separate studies,4,15 to be more likely to have shoulder dislocations as young adults compared with women. The highest incidence occurred in men aged 16 to 20 years in a more recent study. 15 A study by Nabian et al 11 from Iran shows a predominance of injuries in men (86.8%) and highest in those aged 21 to 30 years. Women aged 51 to 70 years were more likely to dislocate their shoulder compared with younger women. 11 This could be partially because concomitant rotator cuff tears and proximal humerus fractures are more common in elderly individuals. Despite possible differences in sports commonly played in the US and other parts of the world, patterns of age and sex found in studies outside the US reflect findings similar to those of the US population and those identified in the present study.4,8,10-12

Previous authors have hypothesized explanations for the increase in shoulder dislocations in men compared with their female counterparts. We suspect that this is likely caused by the higher numbers of shoulder dislocations sustained by younger men and their typical sporting activities. Theories for this trend have included more younger men participating in contact or higher-risk sports. Few previous studies have looked at sex-comparable sports; nonetheless, there is no statistical difference between incidences of shoulder dislocations in men versus women when controlled for sex. However, in other sex-comparable sports, women play a noncontact version of the sports. Examples include lacrosse and field hockey. 6 Our hypotheses align with those of the previous studies. 6 We suspect that younger men participate in more contact sports than age-matched women such as American football, one of the most common sports to sustain a shoulder dislocation. American football is played primarily by younger men and there are larger team sizes. This would also correspond with our findings of increased shoulder dislocations during high school and college-level American football seasons. In addition, this demographic group may have higher risk-taking behaviors. Other propositions have included hormonal differences between sexes. 6 However, further research is needed to confirm any of these theories.

Limitations

The limitations of this study include sampling bias, as the patients included in the study were those who presented to the EDs. However, the NEISS is a sampling of the US population that can be used to determine an overall estimate of the general population. It may be underestimating the total number of shoulder dislocations that occur annually nationwide, and the number of traumatic or sports-related injuries may be underestimated for the same reason. Not all patients with shoulder dislocations, regardless of reduction in or outside medical facilities (eg, on-field, training room, urgent care), presented to an ED. In addition, this study does not specify primary versus recurrent dislocation. As the study uses a national database, it requires correct diagnosis of shoulder dislocation; however, this is likely contributing little to the results as the diagnosis is usually straightforward. Furthermore, we used the general population as the denominator and not the actual population at risk or actual exposure (eg, time spent playing sports). Despite these potential limitations, this is a large epidemiologic study that can be used for future studies.

Conclusion

In this epidemiologic study, we evaluated more than 46,000 shoulder dislocations over a period of 25 years, assessing incidences and trends based on sports participation, age, sex, and race. The overall incidence of shoulder dislocations was consistent with previous studies. Younger people and men were more likely to dislocate their shoulders. Women and people >40 years were less likely to dislocate their shoulders playing sports. The sports that saw the most dislocations included basketball, American football, and cycling. The study findings can help sports organizations plan for medical coverage and investigators to study the effects of any potential injury prevention programs.

Footnotes

Final revision submitted August 22, 2023; accepted September 7, 2023.

The authors have declared that there are no conflicts of interest in the authorship and publication of this contribution. AOSSM checks author disclosures against the Open Payments Database (OPD). AOSSM has not conducted an independent investigation on the OPD and disclaims any liability or responsibility relating thereto.

Ethical approval for this study was waived by the Colorado Multiple Institutional Review Board.

References

- 1. Albright JA, Meghani O, Lemme NJ, Owens BD. Characterization of shoulder instability in Rhode Island: incidence, surgical stabilization, and recurrence. R I Med J (2013). 2022;105(5):56-62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Anderson MJJ, Mack CD, Herzog MM, Levine WN. Epidemiology of shoulder instability in the National Football League. Orthop J Sports Med. 2021;9(5):23259671211007743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bonz J, Tinloy B. Emergency department evaluation and treatment of the shoulder and humerus. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2015;33(2):297-310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Cutts S, Prempeh M, Drew S. Anterior shoulder dislocation. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2009;91(1):2-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Dala-Ali B, Penna M, McConnell J, Vanhegan I, Cobiella C. Management of acute anterior shoulder dislocation. Br J Sports Med. 2014;48(16):1209-1215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. DeFroda SF, Donnelly JC, Mulcahey MK, Perez L, Owens BD. Shoulder instability in women compared with men: epidemiology, pathophysiology, and special considerations. JBJS Rev. 2019;7(9):e10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Gumina S, Proietti R, Polizzotti G, Carbone S, Candela V. The impact of COVID-19 on shoulder and elbow trauma: an Italian survey. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2020;29(9):1737-1742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kroner K, Lind T, Jensen J. The epidemiology of shoulder dislocations. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 1989;108(5):288-290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Leroux T, Wasserstein D, Veillette C, et al. Epidemiology of primary anterior shoulder dislocation requiring closed reduction in Ontario, Canada. Am J Sports Med. 2014;42(2):442-450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Liavaag S, Svenningsen S, Reikeras O, et al. The epidemiology of shoulder dislocations in Oslo. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2011;21(6):e334-e340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Nabian MH, Zadegan SA, Zanjani LO, Mehrpour SR. Epidemiology of joint dislocations and ligamentous/tendinous injuries among 2,700 patients: five-year trend of a tertiary center in Iran. Arch Bone Jt Surg. 2017;5(6):426-434. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Nordqvist A, Petersson CJ. Incidence and causes of shoulder girdle injuries in an urban population. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 1995;4(2):107-112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Owens BD, Agel J, Mountcastle SB, Cameron KL, Nelson BJ. Incidence of glenohumeral instability in collegiate athletics. Am J Sports Med. 2009;37(9):1750-1754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Owens BD, Dawson L, Burks R, Cameron KL. Incidence of shoulder dislocation in the United States military: demographic considerations from a high-risk population. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2009;91(4):791-796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Shah R, Chhaniyara P, Wallace WA, Hodgson L. Pitch-side management of acute shoulder dislocations: a conceptual review. BMJ Open Sport Exerc Med. 2016;2(1):e000116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Shields DW, Jefferies JG, Brooksbank AJ, Millar N, Jenkins PJ. Epidemiology of glenohumeral dislocation and subsequent instability in an urban population. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2018;27(2):189-195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Simonet WT, Melton LJ, III, Cofield RH, Ilstrup DM. Incidence of anterior shoulder dislocation in Olmsted County, Minnesota. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1984(186):186-191. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Sport & Fitness Industry Association. Sports, fitness, and leisure activities topline participation report. Accessed March 14, 2023. https://www.sfia.org

- 19. Szyluk K, Niemiec P, Sieron D, et al. Shoulder dislocation incidence and risk factors-rural vs. urban populations of poland. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(19). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. United States Consumer Product Safety Commission. National electronic injury surveillance system (NEISS). Updated March 14, 2023. Accessed March 14, 2023. https://www.cpsc.gov/ko/Research–Statistics/NEISS-Injury-Data

- 21. Yaari L, Ribenzaft SZ, Kittani M, Yassin M, Haviv B. Epidemiology of primary shoulder dislocations. A cohort study from a large health maintenance organization: 2004 to 2019. Isr Med Assoc J. 2023;25(2):106-109. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Yang NP, Chen HC, Phan DV, et al. Epidemiological survey of orthopedic joint dislocations based on nationwide insurance data in Taiwan, 2000-2005. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2011;12:253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Zacchilli MA, Owens BD. Epidemiology of shoulder dislocations presenting to emergency departments in the United States. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2010;92(3):542-549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]