Abstract

Envelope glycoprotein Erns of classical swine fever virus (CSFV) has been shown to contain RNase activity and is involved in virus infection. Two short regions of amino acids in the sequence of Erns are responsible for RNase activity. In both regions, histidine residues appear to be essential for catalysis. They were replaced by lysine residues to inactivate the RNase activity. The mutated sequence of Erns was inserted into the p10 locus of a baculovirus vector and expressed in insect cells. Compared to intact Erns, the mutated proteins had lost their RNase activity. The mutated proteins reacted with Erns-specific neutralizing monoclonal and polyclonal antibodies and were still able to inhibit infection of swine kidney cells (SK6) with CSFV, but at a concentration higher than that measured for intact Erns. This result indicated that the conformation of the mutated proteins was not severely affected by the inactivation. To study the effect of these mutations on virus infection and replication, a CSFV mutant with an inactivated Erns (FLc13) was generated with an infectious DNA copy of CSFV strain C. The mutant virus showed the same growth kinetics as the parent virus in cell culture. However, in contrast to the parent virus, the RNase-negative virus induced a cytopathic effect in swine kidney cells. This effect could be neutralized by rescue of the inactivated Erns gene and by neutralizing polyclonal antibodies directed against Erns, indicating that this effect was an inherent property of the RNase-negative virus. Analyses of cellular DNA of swine kidney cells showed that the RNase-negative CSFV induced apoptosis. We conclude that the RNase activity of envelope protein Erns plays an important role in the replication of pestiviruses and speculate that this RNase activity might be responsible for the persistence of these viruses in their natural host.

Classical swine fever virus (CSFV), bovine viral diarrhea virus (BVDV), and border disease virus belong to the genus Pestivirus within the family Flaviviridae (10). The viruses are structurally, antigenically, and genetically closely related. BVDV and border disease virus can infect ruminants and pigs. CSFV infections are restricted to pigs (6). Pestiviruses are small, enveloped, positive-stranded RNA viruses (23). The genome of pestiviruses varies in length from 12.5 to 16.5 kb (1, 2, 7, 17, 19, 25, 26, 28, 32) and contains a single large open reading frame (ORF) (1, 7, 8, 17, 26). The ORF is translated into a polyprotein which is processed into mature proteins by viral and host cell proteases (30). The envelope of the pestivirus virion contains three glycoproteins, Erns, E1, and E2 (35). Animals infected with pestiviruses raise antibodies against at least two viral glycoproteins, namely, Erns and E2 (16, 34, 42). Inhibition studies with E2 and Erns produced in insect cells showed that both envelope proteins are indispensable for viral attachment and entry of pestiviruses into susceptible cells (13). In the virion, Erns is present as a homodimer with a molecular mass of about 100 kDa (35). Erns lacks a membrane anchor, and association with the envelope is accomplished by an as-yet-unknown mechanism. Significant amounts of Erns are secreted from infected cells (30). A unique feature is that Erns, besides being an envelope protein, possesses RNase activity (12, 31). Erns belongs to the family of extracellular RNases consisting of several fungal (e.g., RNase T2 and Rh) and plant (e.g., S glycoproteins of Nicotiana alata) RNases (12, 31). These RNases contain two homologous regions of 8 amino acids each which are spaced by 38 (Erns) nonhomologous amino acids and which form the RNase active site. Histidine residues in both regions appear to be essential for RNase catalysis (15).

The role of this RNase activity in the replication of pestiviruses or in the pathogenesis of a pestivirus infection is an interesting issue that, as yet, has not been studied. The availability of a recently generated infectious DNA copy of CSFV strain C (24) has given us the opportunity to study the effect of defined mutations in a pestivirus genome. In this paper, we report the inactivation of the RNase activity of Erns by mutagenesis. To characterize the mutated proteins, we produced large amounts of them in insect cells (12). By reverse genetics, we generated an RNase-negative CSFV recombinant. The effect of the inactivation of the RNase activity of Erns on the replication of CSFV in vitro was studied.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells and viruses.

Swine kidney cells (SK6) (14) were maintained as described previously (24). The preparation of an SK6 cell line which constitutively expresses the bacteriophage T7 RNA polymerase in the cytoplasm of the cell (SK6.T7a5) was approximately the same as described for other stably transformed cell lines (27) and is described in detail elsewhere (36). SK6.T7a5 cells were grown in Dulbecco’s minimal essential medium supplemented with 5% fetal bovine serum (FBS), antibiotics, and 10 mM histidinol. The parent (not mutated) recombinant virus derived from an infectious DNA copy of CSFV strain C was propagated as described previously (FLc133 [24], renamed FLc2). FBS and cells were free of BVDV, and FBS was free of anti-BVDV antibodies.

Autographa californica nuclear polyhedrosis virus and recombinant A. californica nuclear polyhedrosis viruses were propagated in the Spodoptera frugiperda cell line Sf21 as described previously (10). Sf21 cells were grown as monolayers in either TC100 medium (Gibco-BRL) supplemented with 10% FBS and antibiotics or SF900 serum-free medium (Gibco BRL) plus antibiotics.

Mutagenesis of the Erns gene by PCR.

In a first PCR, a part of the Erns gene was amplified in a 35-cycle reaction with Vent DNA polymerase (New England BioLabs) and a baculovirus transfer vector containing the wild-type Erns gene (12) as a template. In this reaction, primers in which the histidine codon (CAT) was substituted with a lysine codon (AAA) were used as forward primers: primer H>K(1), a 35-mer, 5′-GG-GTT-AAC-AGA-AGC-TTG-AAA-GGG-ATC-TGG-CCG-GGG-3′ (nucleotides [nt] 1245 to 1279 in the sequence of CSFV strain C [24]), and primer H>K(2), a 24-mer, 5′-GAA-TGG-AAC-AAA-AAA-GGA-TGG-TGT-3′ (nt 1397 to 1421 [24]). A primer with a flanking BamHI site (underlined) (39 mer, 5′-ATAGTCGACGGATCCTTAGTACCCTATTTTCGTTGTCAC-3′ [12]) was used as a reverse primer. PCR fragments of the correct size were isolated from an agarose gel and used in a second PCR to recover the complete Erns gene. In this reaction, the noncoding DNA strand functions as a reverse primer and the wild-type Erns gene with flanking BamHI sites, isolated from the above-mentioned transfer vector and recloned downstream of the bacteriophage T7 promoter in the BamHI site of pGem4z-bleu, is used as a template. In this reaction, a T7 primer is used as a forward primer. The crude PCR products were BamHI digested, and the 720-bp mutated Erns genes were isolated from an agarose gel and fused to the signal sequence of glycoprotein gG of pseudorabies virus in the baculovirus transfer vector pAcAS3gX as described previously (11). A transfer vector with an Erns gene in which the histidines in both domains were substituted with lysines [H>K(1,2)] was constructed as described above, except that, in the first PCR, the transfer vector with the mutation in the second domain [H>K(2)] was used as a template and the H>K(1) primer was used as a forward primer.

Cloning procedures and DNA manipulations were carried out essentially as described previously (24). DNA-modifying enzymes were used as specified by the manufacturers. Escherichia coli DH5α was used for the propagation of plasmids and cDNA clones.

Construction and selection of baculovirus recombinants.

The transfer vectors containing the mutated Erns genes were used for insertion of Erns into the p10 locus of a baculovirus vector (11). Recombinant viruses expressing the mutated genes, named Bac[H>K(1)], Bac[H>K(2)], and Bac[H>K(1,2)], were selected, and virus stocks were prepared as described previously (11). Restriction enzyme analyses of chromosomal DNA isolated from Sf21 cells infected with wild-type and recombinant baculoviruses showed that the Erns genes were correctly inserted into the p10 locus of the baculovirus vector.

Characterization of Erns expressed in insect cells.

The mutated proteins were purified from the lysate of Sf21 cells infected with the recombinant viruses H>K(1), H>K(2), and H>K(1,2) by immunoaffinity chromatography as described previously (12). The purified proteins were analyzed under reducing and nonreducing conditions by sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE). The RNase activity of the purified proteins was measured as described previously (4). The RNase activity was expressed as A260 units per minute per milligram. Reactivity of the proteins with Erns-specific monoclonal antibodies (MAb) C5, specifically directed against Erns of CSFV strain C (41), and 140.1, directed against Erns of CSFV strain C and Brescia (9), and an Erns-specific polyclonal rabbit serum, 716, was tested in a direct enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) as described recently (12). Serum 716 was prepared by repeated inoculation of a purified preparation of insect cell-produced Erns from CSFV strain Brescia. The neutralizing antibody titer (the reciprocal of the serum dilution neutralizing 100 50% tissue culture infective doses (TCID50) of CSFV strain Brescia [34]) of this serum was 75.

Interaction of proteins expressed in insect cells with the surface of SK6 cells.

To determine whether the mutated Erns proteins are able to inhibit infection of SK6 cells with CSFV, inhibition assays were performed as described previously (13). Inhibition was measured in a dose-dependent manner. Briefly, confluent monolayers of SK6 cells grown in 2-cm2 tissue culture wells were preincubated with 100 μl of Earle’s minimum essential medium (EMEM) containing different concentrations of immunoaffinity-purified Erns. One hundred microliters of a dilution of a stock of CSFV strain Brescia in EMEM (±500 PFU per well) was added, and after 30 min of infection, the virus-Erns mixture was removed and the cells were washed twice with 0.5 ml of EMEM. The cells were supplied with complete medium containing 1% methylcellulose, and after 24 h of growth, groups of infected cells (plaques) were detected by immunostaining (39) and counted. The concentration at which 50% inhibition of infection was achieved was extrapolated from an inhibition graph (number of plaques [y axis] as function of the Erns concentration [x axis]).

Construction of recombinant viruses FLc13, FLc20, and FLc13R.

The mutated H>K(2) and H>K(1) genes were amplified in PCRs as described above. In these reactions, the baculovirus transfer vectors containing the mutated Erns genes were used as templates with primer 935 (5′-CCGAAAATATAACTCAATGG-3′ [24]) as a forward primer and primer 925 (5′-CATAAGCGCCAAACCAGGTT-3′ [24]) as a reverse primer. Erns fragments were isolated from agarose gels and phosphorylated with T4 DNA kinase (New England BioLabs). Fragments were cloned in a calf intestinal phosphatase (New England BioLabs)-treated StuI site of the transient expression vector pPRKc5 (27, 37). This vector, a peVhisd12 derivative (27), contains the nucleotide sequence of the autoprotease and structural genes of CSFV strain C, without Erns (Npro-C and E1-E2, amino acids 5 to 267 and amino acids 495 to 1063, respectively, of the nucleotide sequence of CSFV strain C [24]). In pPRKc5, a unique StuI site was introduced at the position where Erns was deleted. Clones in which the mutated Erns genes were inserted in the correct orientation were transfected to SK6 cells and tested for expression of Erns and E2 by immunostaining as described previously (37). Erns expression was detected with MAb C5, and E2 expression was detected with MAb V3 (specifically directed against E2 of CSFV [40]). From clones which expressed both the Erns and the E2 genes, pPRKc5.H>K(2) and pPRKc5.H>K(1), a ClaI-NgoMI fragment was isolated and inserted in the ClaI-NgoMI-digested pPRKflc133 vector (24). The resulting vectors, pPRKflc13 and pPRKflc20, contain a full-length DNA copy of CSFV strain C with the genes H>K(2) and H>K(1), respectively.

To rescue the RNase-negative virus FLc13, a wild-type Erns gene was amplified in a PCR with primers 935 and 925 (see above) and pPRKflc133 (containing the wild-type Erns gene [24]) as a template. This Erns gene was cloned in pPRKc5 as described above, and the resulting vector, pPRKc10, was tested for Erns and E2 expression as described above. The ClaI-NgoMI fragment of pPRKflc13 was replaced by a ClaI-NgoMI fragment isolated from the Erns- and E2-expressing clone pPRKc10 to give pPRKflc13R.

Transfection and production of recombinant viruses FLc13, FLc20, and FLc13R.

Plasmid DNA from pPRKflc13, pPRKflc20, and pPRKflc13R was purified on columns (Qiagen) and linearized with XbaI. The DNA was extracted with phenol-chloroform, precipitated with ethanol, and dissolved in water. Linearized DNA (250 ng) was diluted in 20 μl of Optimem (Gibco-BRL) and mixed with 20 μl of Optimem containing 2 μg of Lipofectin (Gibco-BRL). The DNA transfection mixture was incubated at room temperature for 15 min. SK6.T7a5 cells, grown in 2-cm2 tissue culture plates, were washed twice with Optimem. Fresh Optimem (160 μl) was added, followed by the DNA transfection mixture. After 16 h of incubation at 37°C, the transfection mixture was removed and the wells were supplied with complete medium. The cells were incubated for 4 days at 37°C, after which the medium was stored at −70°C. Cells were immunostained with MAb C5. The medium collected from wells in which Erns expression was observed was used to infect SK6 cells. After three additional passages in SK6 cells, virus stocks were prepared as described previously (24). The titers (TCID50 per milliliter) of the virus stocks were determined by end-point dilution.

Characterization of recombinant viruses.

Single-step growth kinetics of the wild-type (not mutated) recombinant virus FLc2 and the RNase-negative virus FLc13 were determined with SK6 cells. Confluent monolayers of SK6 cells grown in 25-cm2 tissue culture flasks were infected with a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 2 to 5 TCID50 per cell for 1.5 h at 37°C. The virus was removed from the cells, and the cells were washed and supplied with fresh medium. After 0, 24, 48, 72, and 96 h of growth, the cells were frozen-thawed twice and clarified by centrifugation at 5,000 × g for 10 min. The virus titer (TCID50 per milliliter) was determined by end-point dilution.

The virus neutralization index (log10 reduction of the virus titer [TCID50 per milliliter] in the presence of a neutralizing serum [39]) of the recombinant viruses FLc2, FLc13, and FLc13R was determined at a 1:25 dilution of serum 716 and a 1:100 dilution of a polyclonal pig serum specifically directed against E2 of CSFV strain Brescia (serum 539; neutralizing antibody titer, 1:4,800 [11]) in an end-point dilution titration.

The Erns genes of the recombinant viruses FLc13 and FLc13R were sequenced. For this test, confluent monolayers of SK6 cells grown in 75-cm2 tissue culture flasks were infected with FLc13 and FLc13R as described above. After 72 h of growth, cytoplasmic RNA was isolated as described previously (25) and used as a template in standard reverse transcription-PCR. The amplified DNA fragments covering the complete Erns genes of FLc13 and FLc13R were isolated from agarose gels and directly sequenced with Erns flanking and internal primers by use of an ABI Ready Reaction Dye Terminator cycle sequencing kit (PE Applied Biosystems) and an ABI Prism 310 genetic analyzer (PE Applied Biosystems).

Total cellular DNA of SK6 cells infected with FLc2, FLc13, and FLc13R was isolated after 24, 48, and 72 h of infection. SK6 cells were infected as described above. The medium was removed from the cells, and the monolayers were lysed in 1 ml of ice-cold lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-Cl [pH 8.2], 140 mM NaCl, 2 mM MgCl2, 0.5% [vol/vol] Nonidet P-40, 0.5% [wt/vol] Na deoxycholate). Cells in the medium were recovered by centrifugation at 600 × g for 10 min and lysed in the 1-ml lysate recovered from the wells. An equal volume of 100 mM Tris-Cl [pH 7.2]–25 mM EDTA–300 mM NaCl–2% (wt/vol) SDS containing 200 μg of DNase-free proteinase K (Boehringer) per ml was added, and the extract was incubated for 2 h at 37°C. DNA was extracted with phenol-chloroform and recovered by ethanol precipitation. RNase A-treated DNA (2 to 3 μg) was analyzed on a 1.5% agarose gel to detect DNA fragmentation.

Antigen capture RNase assay.

The RNase activity of Erns expressed in SK6 cells infected with the recombinant viruses FLc2 and FLc13 was measured by a modification of the method of Brown and Ho (4). SK6 cells grown in 150-cm2 tissue culture flasks were infected with FLc2 and FLc13 as described above. After 72 h of growth, the cells were treated with trypsin, centrifuged for 10 min at 600 × g, and lysed in 1 ml of ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing 1% Nonidet P-40. Each well of ELISA plates was coated with 100 μl of 50 mM NaHCO3 (pH 9.65) containing 8 μg of MAb C5 per ml for 16 h at 37°C. The plates were washed with PBS containing 0.05% Tween 80 and 0.2% bovine serum albumin. Dilutions of 100 μl of the lysates in PBS containing 0.05% Tween 80 and 0.2% bovine serum albumin were incubated in two separate plates for 2 h at 37°C. After the plates were washed as described above, bound Erns was detected in one of the two plates with an appropriate dilution of horseradish peroxidase-conjugated MAb 140.1 in PBS containing 0.05% Tween 80 and 4% horse serum. After the plate was washed, the bound conjugate was detected with tetramethylbenzidine (Sigma) as a substrate. The optical density was measured at 450 nm. The amount of Erns bound in the wells was extrapolated with a standard curve prepared from a purified preparation of Erns produced in insect cells. To the wells of the second plate, 100 μl of reaction buffer (50 mM succinate, 10 mM KCl [pH 4.5]) containing 2 mg of Torula yeast RNA (Sigma) per ml was added. After incubation for 16 h at 37°C, the reaction mixture was transferred to a reaction vessel with 20 μl of 25% (vol/vol) HClO4 containing 0.75% (wt/vol) uranyl acetate. After incubation on ice for 5 min, the contents of the reaction vessel were centrifuged for 5 min at 10,000 × g, and 10 μl of the supernatant was collected and diluted 10-fold with water. The A260 was determined in a 100-μl, 10-mm microcell with a Beckman DU spectrophotometer. The RNase activity was expressed as A260 units per minute per milligram. To account for background RNase activity, wells incubated with a lysate prepared from mock-infected SK6 cells tested at the same dilutions were assayed for RNase activity as described for FLc2 and FLc13.

RESULTS

Characterization of mutated Erns proteins expressed in insect cells.

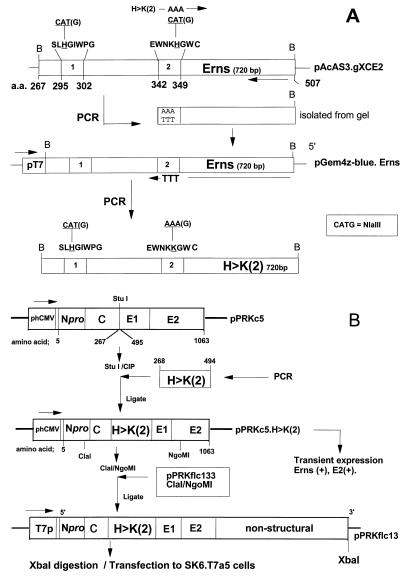

Through chemical inactivation, Kawata et al. (15) showed that the histidine residues in both domains of RNase T2, which are homologous to Erns, were essential for enzyme activity. To inactivate the RNase activity of Erns, the histidine residue in the first and/or second RNase domain was replaced by a lysine residue. In a two-step PCR, the CAT codon at position 297 [H>K(1)] or the CAT codon at position 346 [H>K(2)] in the amino acid sequence of CSFV strain C (24) was replaced by an AAA codon; alternatively, both codons were replaced [H>K(1,2)]. In Fig. 1A, the mutagenesis of the H>K(2) gene is depicted. Mutagenesis of the H>K(1) and H>K(1,2) genes was essentially the same, except that different primers or templates were used (see Materials and Methods). After mutagenesis, the 720-bp mutated Erns genes were analyzed by restriction enzyme digestion. Gel analyses showed that the mutated genes lacked the NlaIII (CATG) site in the RNase domain that corresponded to the primer used for mutagenesis (data not shown). The mutated Erns genes were inserted into the p10 locus of baculovirus as described previously (11). For all three mutated genes, Erns-expressing recombinant viruses, Bac[H>K(1)], Bac[H>K(2)], and Bac[H>K(1,2)], were selected and plaque purified. The mutated Erns proteins and the wild-type Erns protein expressed in insect cells (12) were purified by immunoaffinity chromatography from the lysate of Sf21 insect cells infected with these recombinant baculoviruses. The purified proteins were immunologically and biochemically characterized (Table 1). Compared to wild-type Erns, the mutated proteins H>K(1), H>K(2), and H>K(1,2) had no detectable RNase activity measured between pHs 3.0 and 8.0 at 37°C or between 20 and 65°C at pH 4.5. Analyses of the purified proteins by SDS-PAGE under reducing and nonreducing conditions showed that the mutated proteins had a mobility similar to that of wild-type Erns and also were efficiently dimerized. They also reacted identically with MAb and polyclonal antibodies in a direct ELISA. Moreover, the mutated proteins were able to inhibit infection of SK6 cells with CSFV strain Brescia but at a concentration higher than that measured for wild-type Erns. These results indicated that the conformation of the Erns protein was not severely affected by the substitution of the histidine residues with lysines and that the mutant proteins could still interact with the surface of SK6 cells.

FIG. 1.

(A) Mutagenesis of Erns H>K(2) by PCR. The amino acid sequence of the first (1) and the second (2) RNase domains are given in the one-letter code. a.a., amino acids in the ORF of CSFV strain C (24). The histidine residues at positions 297 and 346 and the introduced lysine residue in the second domain (K) are underlined. PCR primers are indicated by arrows. B, BamHI. pAcAS3.gXCE2 was the template for the first PCR (baculovirus transfer vector containing the nonmutated Erns gene [12]). pGem4z-blue. Erns was the template for the second PCR (containing the nonmutated Erns gene recloned from pAcAS3.gXCE2 into the BamHI site downstream of the bacteriophage T7 promoter of pGem4z-blue). (B) Scheme for the construction of pPRKflc13, the full-length cDNA clone of CSFV strain C containing the mutated Erns gene H>K(2). Npro, autoprotease; C, core protein; E1 and E2, envelope proteins. The pPRKc5.H>K(2) vector, containing the structural genes of CSFV strain C (amino acids 5 to 1063 [24]), including the H>K(2) substitution at position 346 (see panel A), transiently expressed Erns and E2 in SK6 cells. pPRKflc133 is the nonmutated full-length DNA copy of CSFV strain C in plasmid pOK12 (24). phCMV is the promoter-enhancer sequence of the immediate-early gene of human cytomegalovirus. T7p, bacteriophage T7 promoter. CIP, calf intestinal phosphatase.

TABLE 1.

Characterization of mutated Erns proteins

| Protein (42–46 kDa)a | Dimeri- zationb | Inhibitory dose (μg/ml)c | RNase sp act (A260 min−1 mg−1)d | Reactivity with MAb or polyclonal antibody C5/140.1/716e |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Erns | + | 50 | 525 | +/+/+ |

| H>K (1) | + | 180 | <1 | +/+/+ |

| H>K (2) | + | 150 | <1 | +/+/+ |

| H>K (1, 2) | + | 160 | <1 | +/+/+ |

The mass of Erns was determined by SDS-PAGE under reducing conditions.

Detection of dimers of Erns by nonreducing SDS-PAGE.

Concentration of purified Erns that inhibited the infection of SK6 cells with CSFV strain Brescia by 50% (measured in an inhibitor assay; see Materials and Methods).

RNase specific activity of purified Erns proteins was measured at pH 4.5 and 37°C according to the method of Brown and Ho (4).

Reactivity of purified proteins with Erns-specific MAbs C5 and 140.1 and with Erns-specific polyclonal rabbit serum 716 in a direct ELISA.

Construction and rescue of RNase-negative CSFV.

The Erns gene of an infectious DNA copy of CSFV strain C was replaced with the H>K(2) and H>K(1) genes as depicted in Fig. 1B for H>K(2). The resulting full-length cDNAs, pPRKflc13 and pPRKflc20, respectively, were linearized by XbaI digestion and transfected into an SK6 cell line which constitutively expresses the bacteriophage T7 RNA polymerase in the cytoplasm of the cell (SK6.T7a5) (36). Compared to viral positive-stranded sense RNA, transcripts generated from the XbaI-linearized DNA copy have an extension of 5 nt at the 3′ terminus. However, these extended transcripts are as infectious as transcripts with a correct 3′ terminus (24). Four days after transfection, infected SK6.T7a5 cells were detected by immunostaining with Erns-specific MAb C5 for both full-length DNA copies. Moreover, SK6 cells were efficiently infected with the medium collected from wells in which virus-infected cells were detected. These results indicated that an infectious virus with an inactivated H>K(2) or H>K(1) gene, designated FLc13 or FLc20, respectively, was generated from pPRKflc13 and pPRKflc20.

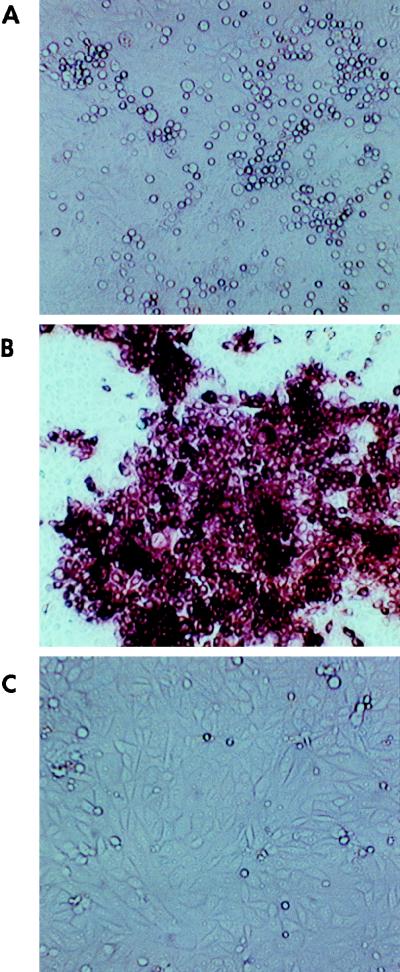

In order to prepare a virus stock, FLc20 and FLc13 were passaged totally five times in SK6 cells. In these successive passages, SK6 monolayers infected with FLc13 and FLc20 appeared considerably less viable than monolayers infected with noncytopathogenic strain C or with wild-type strain C virus FLc2 derived from pPRKflc133. SK6 cells infected with these viruses cannot be distinguished from mock-infected cells. In end-point dilution titrations of the prepared FLc13 and FLc20 virus stocks, clearly isolated groups of spherical cells released from the monolayers were observed (shown for FLc13 after five passages in SK6 cells) (Fig. 2A). Immunostaining of these infected monolayers with an E2-specific MAb showed that at the exact position on the monolayers where these groups of cells were observed, virus-infected cells could be detected (Fig. 2B). These results indicated that FLc13 and FLc20 induced a cytopathogenic effect in SK6 cells.

FIG. 2.

Cytopathogenic effect induced by FLc13. Groups of SK6 cells infected with FLc13 were observed in end-point dilution titrations 96 h after infection before (A) and after (B) immunostaining with a MAb directed against E2 of CSFV. (C) Monolayer of SK6 cells infected with FLc13R before immunostaining. Immunostaining of this monolayer demonstrated that 100% of the cells were infected (data not shown).

To exclude the possibility that induction of this cytopathogenic effect was caused by the introduction of unintended mutations in the full-length DNA sequence during the cloning procedures, mutated Erns was rescued. The ClaI-NgoMI-digested pPRKflc13 vector was used to construct a full-length DNA copy with a wild-type Erns gene (cf. Fig. 1B). Transfection of the resulting vector, pPRKflc13R, yielded a virus, FLc13R, that induced no cytopathogenic effect in SK6 cells (after five passage in SK6 cells) (Fig. 2C).

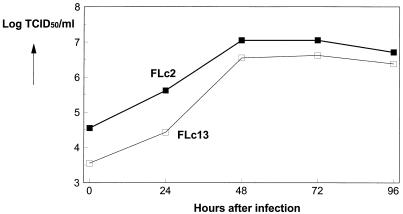

Characterization of CSFV recombinant viruses.

Single-step growth kinetics were determined for FLc2 and FLc13 (Fig. 3). FLc13 grows as fast and almost to the same titer as FLc2. After 48 h, maximum titers of 106.5 TCID50/ml for FLc13 and 107 TCID50/ml for FLc2 were achieved. Since FLc20 grows to the same titer in SK6 cells as FLc13 (results not shown), FLc20 was not further characterized.

FIG. 3.

Single-step growth kinetics of FLc2 and FLc13. Confluent monolayers of SK6 cells were infected with an MOI of 2 to 5 TCID50 of FLc2 and FLc13 per cell for 1.5 h at 37°C. The virus was removed, and fresh medium was added. After 0, 24, 48, 72, and 96 h of growth, the virus titer of the medium plus cells was determined by end-point dilution.

To determine whether the mutated Erns was incorporated in the viral envelope, virus stocks of FLc2, FLc13, and FLc13R were titrated by end-point dilution in the presence or absence of CSFV-neutralizing antibodies. In Table 2, the log10 reduction of the virus titers in the presence of neutralizing antibodies (virus neutralization index) for these viruses are presented. Neutralization of FLc13 by Erns-specific polyclonal rabbit serum 716 indicated that the H>K(2) protein was incorporated in the viral envelope. However, FLc13 was neutralized less by serum 716 than were FLc2 and the rescued recombinant virus FLc13R. All three recombinant viruses were neutralized to the same extent by E2-specific polyclonal serum 539. No cytopathogenic effect was observed in wells in which FLc13 was completely neutralized by serum 716 or 539. These results indicated that the cytopathogenic effect was an inherent property of FLc13.

TABLE 2.

Neutralization of viruses by antibodies

| Virus | Virus neutralization index (log10 TCID50/ml) with serum

|

|

|---|---|---|

| 716 (directed against Erns) | 539 (directed against E2) | |

| FLc2 | 2.7 | 4.7 |

| FLc13 | 1.8 | 4.4 |

| FLc13R | 2.5 | 4.4 |

Sequence analysis of reverse transcription-PCR fragments covering the complete Erns genes of FLc13 and FLc13R showed that no unintended mutations were introduced in these genes. Moreover, the introduced lysine codon in the second RNase domain of FLc13 Erns was still present (i.e., the histidine codon was absent) after five passages in SK6 cells.

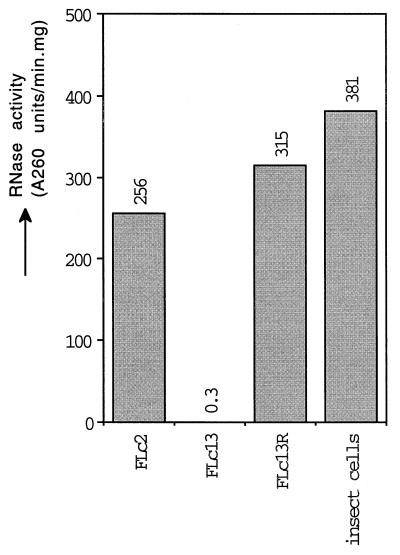

The RNase activity of Erns expressed by FLc2, FLc13, and FLc13R was determined in an antigen capture RNase assay. On an ELISA plate coated with Erns-specific MAb C5, Erns was captured from the lysates of SK6 cells infected with FLc2 and FLc13. Unbound proteins were washed away, and the RNase activity of bound Erns proteins was measured as described by Brown and Ho (4). On a duplicate plate, the amount of Erns captured by MAb C5 was estimated after detection with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated MAb 140.1. In this assay, no significant RNase activity of the MAb C5-bound H>K(2) protein of FLc13 could be measured (Fig. 4). In contrast, the RNase activities of bound wild-type Erns expressed by FLc2 and FLc13R and expressed in insect cells were comparable to the RNase activities of unbound wild-type Erns expressed in insect cells (cf. Table 1).

FIG. 4.

RNase specific activity (A260 min−1 mg−1) of Erns expressed by FLc2, FLc13, and FLc13R but not of mutated Erns purified from insect cells. Activity was measured at 37°C and pH 4.5 in an antigen capture RNase assay.

Analyses of total cellular DNA of SK6 cells infected with recombinant CSFV.

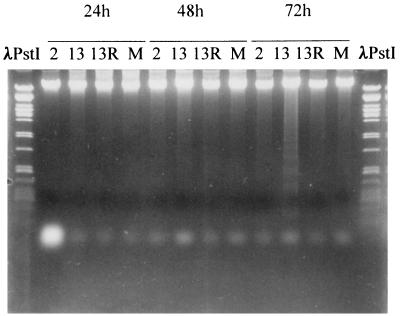

To obtain information about the mechanism underlying the cytopathogenic effect observed in SK6 cells infected with FLc13, total cellular DNA was extracted from SK6 cells infected with FLc2, FLc13, and FLc13R. Spherical cells released from the monolayers were recovered by centrifugation and extracted together with monolayer-associated cells. Agarose gel analysis of the extracted DNA showed that DNA isolated from SK6 cells infected with FLc13 was fragmented to a characteristic DNA ladder faintly observed after 48 h and clearly observed after 72 h of infection (Fig. 5). No fragmentation was observed in DNA extracted from SK6 cells infected with FLc2 and FLc13R. When DNA was extracted from monolayer-associated SK6 cells infected with FLc13 (without spherical cells), no DNA fragmentation was observed (results not shown). These results clearly indicated that the cytopathogenic effect induced by the RNase-negative virus FLc13 was a result of programmed cell death or apoptosis rather than necrosis.

FIG. 5.

DNA gel analysis. Confluent monolayers of SK6 cells were infected with an MOI of 2 to 5 TCID50 of FLc2 (2), FLc13 (13), and FLc13R (13R) per cell for 1.5 h at 37°C. The virus was removed, and fresh medium was added. After 0, 24, 48, and 72 h of growth, cells released from the monolayer were recovered by centrifugation and extracted together with monolayer-associated cells. Extracted DNA (3 μg) was analyzed on a 1.5% agarose gel. PstI-digested lambda DNA was run in parallel as a molecular weight calibration (λ PstI). M, mock-infected SK6 cells.

DISCUSSION

In this paper, we report the inactivation of the RNase activity of envelope protein Erns of CSFV. As reported for fungal RNase T2 (15), the histidines in both domains of Erns are essential for RNase activity. Substitution of the histidine residues in either of the two catalytic domains with lysine residues completely inactivated the enzyme activity of the Erns proteins expressed in insect cells.

Because there is a space of 38 amino acids between the domains (12), strong interactions between amino acid residues of both domains are probably involved in the formation of the active site of Erns (43). Moreover, the conformation of Erns is probably dependent on the formation of this active site. The RNase activity of Erns reaches a maximum between pHs 4.5 and 6.5 (12, 43). To inactivate the enzyme activity of Erns without destroying its conformation, the in an acidic milieu positively charged histidine residues were replaced with positively charged lysine residues. The reactivity of Erns-specific antibodies with the inactivated Erns proteins and the fact that these proteins were efficiently dimerized and glycosylated demonstrated that this approach was successful. It is likely that the interactions between amino acids which are important for the conformation of Erns were not affected by these substitutions.

The interaction of envelope protein Erns with the plasma membrane is essential for pestivirus infection (13). To ensure that the inactivated Erns proteins were still able to interact properly with the cell surface to mediate infection, we performed inhibition assays. All three inactivated Erns proteins were able to inhibit infection of swine kidney cells with CSFV. Furthermore, recombinant viruses FLc13 and FLc20, with the inactivated H>K(2) and H>K(1) genes, respectively, were able to infect swine kidney cells efficiently. FLc13 grows as fast and almost to the same titer as wild-type virus FLc2 in swine kidney cells. Together with the finding that FLc13 was neutralized by an Erns-specific serum, these results indicated that the H>K(2) protein was incorporated into the viral envelope and was able to mediate infection as efficiently as wild-type Erns. The threefold-higher concentration needed to achieve 50% inhibition and the fact that FLc13 was neutralized less by an Erns-specific serum than was FLc2, however, indicated that there are at least some structural differences between H>K(2) and wild-type Erns.

CSFV strain C (a vaccine strain [34]) is noncytopathogenic in cell cultures. Therefore, we were surprised that inactivation of the RNase activity of Erns resulted in the production of cytopathogenic CSFV. To exclude the possibility that this cytopathogenic effect was caused by the introduction of unwanted mutations in the DNA copy of strain C, we replaced the H>K(2) gene with the original Erns gene. The virus produced, FLc13R, induced no cytopathogenic effect in swine kidney cells and could not be distinguished from FLc2 by neutralization with Erns-specific antibodies. The substitution of the histidine with a lysine was a stable mutation. After five rounds of replication, the histidine codon was still absent in the viral RNA of FLc13, and FLc13 still expressed an Erns protein [H>K(2)] that had no detectable RNase activity. Therefore, we conclude that inactivation of the RNase activity is responsible for the cytopathogenic character of FLc13.

In tissue cultures, noncytopathogenic and cytopathogenic biotypes of pestiviruses can be distinguished. The RNA genomes of the noncytopathogenic biotypes are about 12.5 kb long (1, 17, 25, 26). Immunotolerant calves persistently infected with BVDV sporadically develop mucosal disease (3, 5). In addition to a noncytopathogenic BVDV strain, a cytopathogenic BVDV strain with a considerably larger (2, 18, 19, 28, 32) or smaller (29, 33) RNA genome is always isolated from such calves. Molecular analyses of these isolates (virus pair) revealed that the cytopathogenic biotype is formed by recombination of the noncytopathogenic genome with cellular or viral RNA sequences (2, 19, 20, 32, 33). These recombination events provoke altered protein processing of the nonstructural NS2-3 protein, resulting in the expression or enhanced expression of NS3, generally accepted as the cause for the induction of cytopathogenicity in vitro (2, 20, 32, 33). The majority of CSFV strains isolated from pigs are noncytopathogenic in cell cultures. However, in a few cases, a cytopathogenic pestivirus was isolated from pigs (22, 23). Furthermore, after 230 passages of a noncytopathogenic CSFV isolate in cell cultures, cytopathogenic defective interfering particles were detected (22). The generation of defective interfering particles with an infectious DNA copy of CSFV suggested that the cytopathogenicity of these isolates can also be attributed to altered expression of NS3 (21). Information about the mechanism by which and the concentration in infected cells at which NS3 induces cell lysis is as yet not available. NS3 is a multifunctional enzyme and possesses serine protease, nucleoside triphosphatase, and RNA helicase activities (38, 44). The enzyme activity of NS3 could play a role in the induction of cell lysis. Recently, Zhang et al. reported that the death of cells infected with a cytopathogenic BVDV strain was mediated by apoptosis (45). They suggested that the precursor of NS3, NS2-3, could block apoptosis in cells infected with noncytopathogenic virus and that NS3 could inhibit this function of NS2-3 in cells infected with cytopathogenic virus. DNA analyses showed that the cytopathogenic effect induced by FLc13 is also a result of apoptosis. As observed for FLc2, only NS2-3 and not NS3 could be detected by radioimmunoprecipitation in the lysate of SK6 cells infected with FLc13 (results not shown). Moreover, there was also no decrease in the level of expression of NS2-3 for FLc13 compared to FLc2. In general, cells infected with cytopathogenic pestiviruses express detectable levels of NS3 and significantly more NS3 than do cells infected with their noncytopathogenic counterparts (2, 20, 22, 32, 33). Therefore, we conclude that the induction of apoptosis by FLc13 most likely is not caused by altered expression of NS3 and is the exclusive result of inactivation of the RNase activity of Erns. It is likely that the RNase activity of Erns prevents apoptosis and consequently cell lysis. If so, the RNase activity of Erns probably plays a role in the regulation of RNA synthesis in virus-infected cells. Because Erns readily hydrolyzes CSFV-specific RNA of positive and negative polarities (12, 43), it is unlikely that viral RNA synthesis is affected by Erns. Most likely, cellular RNA synthesis is down-regulated by Erns. In cells infected with RNase-negative CSFV FLc13, the lack of down-regulation of cellular RNA synthesis could result in an exceptionally high level of cell metabolism. If sufficient nutrients or growth factors are not available to support this higher level of metabolism, programmed cell death may be induced. This hypothesis is in line with our observation that mock-infected swine kidney cells spontaneously become apoptotic when they were grown in EMEM with a low percentage of FBS (1%). More studies have to be performed to elucidate the mechanism by which, at which stage in the life cycle of pestiviruses, and in what cellular compartment the RNase activity of Erns prevents apoptosis in swine kidney cells.

Animal experiments have to be performed to find out whether FLc13 also induces apoptosis in specific target cells of the natural host. If so, Erns, as suggested for NS2-3, might be a prerequisite for the persistence of pestivirus strains in their natural hosts. Because the RNase domains in Erns are homologous with those in plant and fungal RNases (12), it seems likely that the Erns gene or at least the two RNase domains were acquired by pestiviruses through RNA recombination with cellular sequences. Therefore, acquisition of this RNase activity might have been important for the adaption of pestiviruses to their hosts and for their survival in evolution.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We thank M. Widjojoatmodjo for critical reading of the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Becher P, Shannon A D, Tautz N, Thiel H-J. Molecular characterization of border disease virus, a pestivirus from sheep. Virology. 1994;198:542–551. doi: 10.1006/viro.1994.1065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Becher P, Meyers G, Shannon A D, Thiel H-J. Cytopathogenicity of border disease virus is correlated with integration of cellular sequences into the viral genome. J Virol. 1996;70:2992–2998. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.5.2992-2998.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bolin S R, McClurkin A W, Cutlip R C, Coria M F. Severe clinical disease induced in cattle persistently infected with noncytopathic bovine viral diarrhea virus by super-infection with cytopathic bovine viral diarrhea virus. Am J Vet Res. 1985;46:573–576. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brown P H, Ho T D. Barley aleurone layers secrete a nuclease in response to gibberellic acid. Plant Physiol. 1986;82:801–806. doi: 10.1104/pp.82.3.801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brownlie J, Clarke M C, Howard C J. Experimental production of fatal mucosal disease in cattle. Vet Rec. 1984;114:535–536. doi: 10.1136/vr.114.22.535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carbrey E A, Stewart W C, Kresse J L, Snijder M L. Natural infection of pigs with bovine diarrhoea virus and its differential diagnosis from hog cholera. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1976;169:1217–1219. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Collett M S, Larson R, Gold C, Strick D, Anderson D K, Purchio A F. Molecular cloning and nucleotide sequence of the pestivirus bovine viral diarrhea virus. Virology. 1988;165:191–199. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(88)90672-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Collett M S, Larson R, Belzer S K, Petzel E. Proteins encoded by bovine viral diarrhea virus: the genomic organization of a pestivirus. Virology. 1988;165:200–208. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(88)90673-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.de Smit, H. Unpublished data.

- 10.Francki R I B, Fauquet C M, Knudson D L, Brown F. Flaviviridae. Arch Virol Suppl. 1991;2:223–233. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hulst M M, Westra D F, Wensvoort G, Moormann R J M. Glycoprotein E1 of hog cholera virus expressed in insect cells protects swine from hog cholera. J Virol. 1993;67:5435–5442. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.9.5435-5442.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hulst M M, Himes G, Newbigin E, Moormann R J M. Glycoprotein E2 of classical swine fever virus: expression in insect cells and identification as a ribonuclease. Virology. 1994;200:558–565. doi: 10.1006/viro.1994.1218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hulst, M. M., and R. J. M. Moormann. Inhibition of pestivirus infection in cell culture by envelope proteins Erns and E2 of classical swine fever virus: Erns and E2 interact with different receptors. J. Gen. Virol., in press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Kasza L, Shadduck J, Christofinis G. Establishment, viral susceptibility, and biological characteristics of a swine kidney cell line, SK-6. Res Vet Sci. 1972;13:46–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kawata Y, Sakiyama F, Tamaoki H. Amino-acid sequence of ribonuclease T2 from Aspergillus oryzae. Eur J Biochem. 1988;176:683–697. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1988.tb14331.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kwang J, Littledike E, Donis R, Dubovi E. Recombinant polypeptide from the gp48 region of the bovine viral diarrhoea virus (BVDV) detects serum antibodies in vaccinated and infected cattle. Vet Microbiol. 1992;32:281–292. doi: 10.1016/0378-1135(92)90151-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Meyers G, Rümenapf T, Thiel H-J. Molecular cloning and the nucleotide sequence of the genome of hog cholera virus. Virology. 1989;171:555–567. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(89)90625-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Meyers G, Rümenapf T, Thiel H-J. Ubiquitin in a togavirus. Nature (London) 1989;341:491. doi: 10.1038/341491a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Meyers G, Tautz N, Dubovi E J, Thiel H-J. Viral cytopathogenicity correlated with integration of ubiquitin-coding sequences. Virology. 1991;180:602–616. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(91)90074-L. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Meyers G, Tautz N, Stark R, Brownlie J, Dubovi E J, Collett M S, Thiel H-J. Rearrangement of viral sequences in cytopathogenic pestiviruses. Virology. 1992;191:368–386. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(92)90199-Y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Meyers G, Thiel H-J, Rümenapf T. Classical swine fever virus: recovery of infectious viruses from cDNA constructs and generation of recombinant cytopathogenic defective interfering particles. J Virol. 1996;70:763–770. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.3.1588-1595.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Meyers G, Thiel H-J. Cytopathogenicity of classical swine fever virus caused by defective interfering particles. J Virol. 1995;69:3683–3689. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.6.3683-3689.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Moennig V. Characteristics of the virus. In: Liess B, editor. Classical swine fever and related viral infections. Boston, Mass: Martinus Nijhoff Publishing; 1988. pp. 55–88. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Moormann R J M, van Gennip H G P, Miedema G K W, Hulst M M, van Rijn P A. Infectious RNA transcribed from an engineered full-length cDNA template of the genome of a pestivirus. J Virol. 1996;70:763–770. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.2.763-770.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Moormann R J M, Hulst M M. Hog cholera virus: identification and characterization of the viral RNA and the virus-specific RNA synthesized in infected swine kidney cells. Virus Res. 1988;11:281–291. doi: 10.1016/0168-1702(88)90002-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Moormann R J M, Warmerdam P A M, van der Meer B, Schaaper W, Wensvoort G, Hulst M M. Molecular cloning and nucleotide sequence of hog cholera virus strain Brescia and mapping of the genomic region encoding envelope protein E1. Virology. 1990;177:184–198. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(90)90472-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Peeters B, De Wind N, Hooisma M, Wagenaar F, Gielkens A, Moormann R. Pseudorabies virus envelope glycoproteins gp50 and gII are essential for virus penetration, but only gII is involved in membrane fusion. J Virol. 1992;66:894–905. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.2.894-905.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Qi F, Ridpath J F, Lewis T, Bolin S R, Berry E. Analysis of the bovine viral diarrhea virus genome for possible cellular insertions. Virology. 1992;189:285–292. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(92)90704-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Renard A, Guiot C, Schmetz D, Dagenias L, Pastoret P P, Dina D, Martial J A. Molecular cloning of bovine viral diarrhea viral sequences. DNA. 1985;4:429–438. doi: 10.1089/dna.1985.4.429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rümenapf T, Unger G, Strauss J H, Thiel H-J. Processing of the envelope glycoproteins of pestiviruses. J Virol. 1993;67:3288–3294. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.6.3288-3294.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schneider R, Unger G, Stark R, Schneider-Scherzer E, Thiel H-J. Identification of a structural glycoprotein of an RNA virus as a ribonuclease. Science. 1993;261:1169–1171. doi: 10.1126/science.8356450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tautz N, Meyers G, Stark R, Dubovi E D, Thiel H-J. Cytopathogenicity of a pestivirus correlated with a 27-nucleotide insertion. J Virol. 1996;70:7851–7858. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.11.7851-7858.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tautz N, Meyers G, Dubovi E D, Thiel H-J. Pathogenesis of mucosal disease: a cytopathogenic pestivirus generated by an internal deletion. J Virol. 1994;68:3289–3297. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.5.3289-3297.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Terpstra C, Wensvoort G. The protective value of vaccine-induced neutralizing antibody titres in swine fever. Vet Microbiol. 1988;16:123–128. doi: 10.1016/0378-1135(88)90036-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Thiel H-J, Stark R, Weiland E, Rümenapf T, Meyers G. Hog cholera virus: molecular composition of virions from a pestivirus. J Virol. 1991;65:4705–4712. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.9.4705-4712.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Van Gennip, H. G. P., P. A. van Rijn, and R. J. M. Moormann. Unpublished data.

- 37.Van Rijn P A, Van Gennip H G P, de Meijer E J, Moormann R J M. Epitope mapping of envelope glycoprotein E1 of hog cholera virus strain Brescia. J Gen Virol. 1993;74:2053–2060. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-74-10-2053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Warrener P, Collett M S. Pestivirus NS3 (p80) protein possesses RNA helicase activity. J Virol. 1995;69:1720–1726. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.3.1720-1726.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wensvoort G, Terpstra C, Boonstra J, Bloemraad M, van Zaane D. Production of monoclonal antibodies against swine fever virus and their use in laboratory diagnosis. Vet Microbiol. 1986;12:101–108. doi: 10.1016/0378-1135(86)90072-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wensvoort G. Topographical and functional mapping of epitopes on hog cholera virus with monoclonal antibodies. J Gen Virol. 1989;70:2865–2876. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-70-11-2865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wensvoort G. Epitopes on structural proteins of hog cholera (swine fever) virus. Ph.D. thesis. Utrecht, The Netherlands: State University of Utrecht; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wensvoort G, Boonstra J, Bodzinga B. Immuno-affinity purification of envelope protein E1 of hog cholera virus. J Gen Virol. 1990;71:531–540. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-71-3-531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Windisch J M, Schneider R, Stark R, Weiland E, Meyers G, Thiel H-J. RNase of classical swine fever virus: biochemical characterization and inhibition by virus-neutralizing monoclonal antibodies. J Virol. 1996;70:352–358. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.1.352-358.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wiskerchen M, Collett M S. Pestivirus gene expression: protein p80 of bovine viral diarrhea virus is a proteinase involved in polyprotein processing. Virology. 1991;184:341–350. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(91)90850-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhang G, Aldridge S, Clarke M C, McCauley J W. Cell death induced by cytopathic bovine diarrhoea virus is mediated by apoptosis. J Gen Virol. 1996;77:1677–1681. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-77-8-1677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]